#what is WRONG with sociologists

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

oh. there’s the problem

#what is WRONG with sociologists#the other part i get. but something is rotten in denmark.#and by denmark i mean the field of sociology

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

everyone doing the olympics to understand henry or richard's sexualities, meanwhile charles is like a fucking game of monopoly.

#charles macaulay should be castrated but his sexuality riddles any sociologist and sexologist on earth#like what the fuck is he what is wrong with him#gender: blond twin man#sexuality: my sister

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

sidenote. My Brianna Wayne is an Into the Multi-verse rendition of Batman Begins!Batman. Was born to Thomas and Martha Wayne, same story but from an empowering woman's perspective.

#muse: Brianna Wayne#a sociologists experiment on if people can accept incredible male storylines for women.#and as someone who is not trans- it is inappropriate for me to try and undertake/pretend to know what it is like for trans. I feel#it is clearly wrongful appropriation. However I am a woman and can write these stories from a woman's perspective

0 notes

Text

not to be dramatic but

#I might end up physically brawling with my history lecturer#we're not even 4 weeks in and we have major beef#because she's setting these readings right? I'm doing the readings. I'm taking it all in.#and she always puts in a really controversial piece#one week it was a statistician that was wrong about smth in the 70s#last week it was a flame piece on mary seacole from the sociologist who founded the florence nightingale society#anyway she keeps being really weird and defensive about these articles that have SO many issues#and in class I discuss it with the other students and with her and I bring receipts and notes and I have a handle on my argument#and SHE the TEACHER a lot of the time will just not be familiar with the section I'm making a point about#and will be like 'lol I guess I should read it again' LIKE????#lady you don't even know what's in the assigned readings?#and even when she does know what myself and others are talking about she's still super defensive!!!#that should not be the point of a class discussion!! you're meant to facilitate debate!#also it's just so wild that she was on mckeown's dick so much because he was just flat out wrong#and we've known he was wrong two of my lifetimes ago#and yet she's still teaching his work and the less critical of my classmates are just going to take that with them..........#like okay cool what else should I be wary of in these classes and should I bring boxing gloves to the next tutorial

0 notes

Note

I really like dropouts content overall, but there was a bit in a season of Dimension 20 (Starstruck) where an exploitative, deceptive man (Dan Scrap) dressed up as a woman (Danielle Scrap) to invade a space designed to exclude men in order to reap the benefits of that space. Like that's THE narrative transphobes use, and there Brennan doing it as a bit and the rest of the main cast laughing uproarsly about it. It made me feel nauseous. There definitely is a transmisogyny issue at dropout

this is the kind of stuff im talking about — i like Brennan, he’s funny, he’s a good comic, but a mistake like this isn’t just a “he said the wrong pronoun by accident” type thing — it betrays a foundational misunderstanding to what transphobia is and how/why it functions the way it does. now that makes sense, Brennan is a cis man without these experiences, he isn’t an activist or a sociologist, but you know maybe that is the perfect demonstration of how he isn’t the best pick for a “deconstructive pastiche of Harry Potter” tabletop campaign — maybe a real life trans woman would be a better pick? somebody who has actually had to contend with bigotry a day in their life, even, maybe!

given how often Dimension 20 players (including the MisMag party!!) make jokes about feminine men stuff like this seems really glaring to trans girls who would’ve been prospective fans. i don’t feel comfortable watching that shit! it feels like a bunch of TME people patting themselves on the back for being good allies without paying attention to how to correct the wrongs in question, like a totally superficial distinction.

i’ve heard that Dropout specifically apologised for this instance, but i really don’t think that fixes the problem. the fact that “a man calling himself a woman’s name and pretending he’s a woman to sneak into a women’s space” is a story that made it far enough into play that there was actual discourse over it is a big fucking deal, not just a small mistake, but the literal exact same type of transmisogyny that Dimension 20’s players are supposed to be deconstructing… so why do we have players who don’t even know how to not REINFORCE those biases? Surely a cis man who literally cannot functionally or materially identify transmisogyny should not be your top pick for a “harry potter without the bigotry” campaign?

it’s cool that other marginalised demographics are represented in MisMag (and Dimension 20 in general) but let’s be totally honest with ourselves: JK Rowling didn’t join the KKK, she isn’t rallying against abortion rights — she is pouring millions and millions of dollars into criminalising specifically transfeminine existence. it is unequivocally a bad look to seemingly intentionally exclude transfems from a commentary on her works, and an even worse & transmisogynistic move to double down on a second season without a transfeminine player, especially after the (totally unaddressed!) backlash from transfem fans the first time.

446 notes

·

View notes

Note

This is in no way of hating but i want to know why do you enjoy writing noncon/rape? When I first downloaded tumblr which was couple of months ago i was surprised by the amount of noncon fics here. I eventually came to enjoy them which makes me question myself. Whenever i read a noncon fic and enjoy it i feel like im betraying women who actually went through those traumatic events. Plus I actually don't really like dark romance books? I love cod dead dove and that is mainly because i really love the characters and the authors are so talented. I rambled so much and i hope you don't get this in the wrong way i don't mean to hate AT ALL i love the stuff you write. Maybe i shouldn't think too much and let myself enjoy what im reading lol

first of all, no worries! i wasn't sure about your tone/intentions at first, but by the end i was totally fine with the question.

i actually don't mind talking about this stuff - i just sometimes avoid it on main because i prefer chatting about it privately.

second, i'm no psychologist or sociologist, so i probably won't be able to give you the most satisfactory answer, but i think there are a lot of different reasons. i can only name a few. one thing i should mention right off the bat is that rape fantasies are very normal (and this is true whether you're a survivor of SA or not) and writing/reading fiction can be a safe way to process those thoughts/feelings.

one of prevailing reasons is, of course, that many survivors of SA use noncon/dubcon literature/art as a way of processing their experiences and taking ownership of their trauma.

and look, people are going to go back and forth on this point (i've seen it all before - many people refuse to believe that engaging with noncon lit/art is helpful, and in fairness, it's NOT helpful for everyone because every person is different), but at the end of the day, if a survivor tells you "writing/reading this was helpful in my recovery" then that's that!

additionally, for many women and non-binary folk (i can only speak as a cis woman, but i'm sure this is a shared lived experience across many different people), we're also taught from a very young age to suppress our sexual desires / that being open about our sexuality is morally reprehensible and shameful. and a lot of people carry that shame for years, impacting them well into adulthood. so dubcon/noncon fantasies can be a way of being able to enjoy sexual scenarios where you don't have to be the initiator, thus taking away some of the emotional weight and shame.

plus, at the end of the day (and im sure many people will disagree with this take, it's something that i'm still figuring out myself), there is a kind of weird underlying consent implicit in dark fics. like, you might be reading a fic or novel that's ostensibly noncon, but you're also actively seeking out that literature (hopefully it's not just sprung on you - i do very much agree with tagging to the fullest extent and my lukewarm take is that I think all books, even traditionally published ones, should come with content/trigger warnings too).

there are a medley of reasons why someone might write or read dark fiction/dark romance. again, i'm just one person and i can only speak from my own experience!

i think at the end of the day, the important thing to realize is that fiction is fake, and as long as the writer appropriately tags their work and ensures that the audience is aware of what they're getting into when they start reading, they're not coercing the reader into something they aren't prepared for.

and it's totally fine if you have limits (like, you can read and enjoy dubcon, but not noncon) or can't engage with the material at all, but it's also unfair to say that it reflects someone's real life values - the same way that we don't say that the people who enjoy crime fiction must love murder.

and the last thing i want to say because this got a bit out of hand lol, is that, yes, for some people dark fiction is genuinely harmful, whether or not they're a survivor. it's not for everyone and that's completely fine and i'm aware of that, which is why i agree that you should tag as much as possible (even if you feel like you're overdoing it sometimes), but someone else's discomfort doesn't give them the right to tell you how to process your own emotions/experiences/desires/etc.

as long as no one's getting hurt, there's no issue as far as i'm concerned. and sorry but, no one's getting hurt by reading a fic or a novel unless the author didn't give proper content warnings - if you "forgot" to read the tags or read anyway DESPITE being warned, im sorry but that's life.

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

With regards to "lonely young men" discourse, people often talk as though this is a new problem which confronts young men and often as if it's a problem that's unique to the digitalized world, that the internet plays a casual role.

That kind of attribution is wrong-headed even if digital technology has exacerbated it, but the decline in socialization among young men predates the internet reaching into everyday life. The decline starts by the 1950s. If there's a technology that's responsible, it's the suburb, which isolated individuals into nuclear families, couples, or themselves alone. The increased distance between individuals, represented easily by population density statistics, obviously created the material basis for social estrangement and isolation. That, combined with the technology of the car, which isolates the individual even further into a cell with antagonistic relations to other cells on the highways, did a number on the very possibility of socialization in our everyday lives. Even at work, the tendency of capitalists to reduce the number of people on the job to a minimum has done damage to the potential of workers to socialize on the job.

Plenty of young men have false consciousness about the causes of their isolation or estrangement from society, but they are a real problem (and it doesn't just afflict young men). When the average young person is not contributing to society in a way that makes them feel like a part of it, when the society their labor reproduces also reproduces their isolation and estrangement, what else can you expect but the rise of anti-social ideology corresponding to the anti-social material conditions?

Left-wing theorists have had all kinds of analyses of these issues, with Erich Fromm, Paul Goodman, and Raoul Vaneigem coming to my mind as theorists from the mid-20th century who tackled the subject. But even liberal sociologists have been able to see it, the book that's usually cited on this front is "Bowling Alone". Reducing the issue to resentments from men who aren't trying hard enough to get laid just recycles that resentment and fails to account for the non-sexual aspects of this isolation which are just as damaging to the individual psyche: the lack of friends, colleagues, and confidants to share their thoughts with, and the stunted social skills that many young people (and the rest of us) are dealing with as a result of a lack of socialization.

#bong rip#honestly you can go back further and see durkeheim talk about it#but we don't talk about durkeheim here

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have been getting a tad bit too obsessed with reverse 1999 lately and compiled some stuff around might edit it if i find more

this yapping session will be abt sonetto

her name is deprived from a fourteen line poetry called the Sonnet while also having the meaning of “little song or sound’

her udimo is a dog called Cirneco Dell’Etna a breed that originated from italy as stated in her storyboard

she doesn't know her date of birth and uses the date of when she was adopted by the foundation as her birthday (January 10th)

she's 16 yrs old

she's speculated to be 5'3 ft or 160 cm

her compliments are so sincere that people are often too shy to face her (the rizzler)

back in SPDM she was worried about vertin's arcane skill exams and tutored her privately

a helper in the SPDM once found a challenge letter with pink heart patterns in the trash bin (might imply that the letter was from matilda to sonetto)

sonetto is an artist as stated in her 80% bond story and glassfeder's description

sonetto likes collecting newspapers and treasures them

every year she gets a present from vertin on her birthday which is mostly a collection of poems

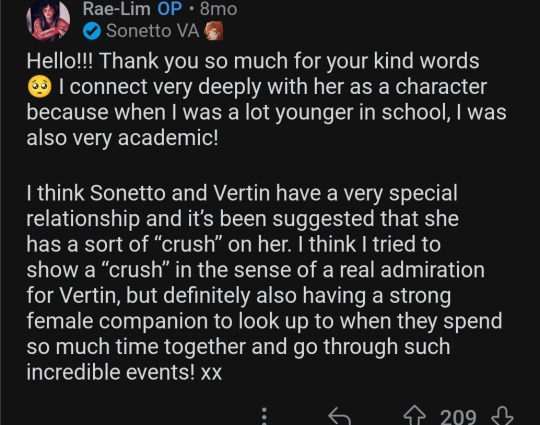

it’s implied (this is really obvious) that she has a crush on the timekeeper/Vertin and has also been implied sonetto's va during the reddit Q&A

on her medal she has an embroidered dog on it (i just thought this was cute)

since she doesn't know much about the outside world or her culture she doesn't see anything wrong with pineapple pizza or gelato pizza for that matter (april fools and pizza hut collab comic)

she keeps a frog in a jar in her room

time for voiceline analysis

"Sempre caro mi fu quest'ermo colle.”

this quote is derived from the poem L’Infinito by Giacomo Leopardi in the autumn of 1819 the poem is meant to show how he yearns to travel beyond his restrictive hometown of Recanati and experience more of the world that he studied.

this can also show the way sonetto might have wished to see the outside world just as she studied on the textbooks

"Regna sereno intenso ed infinito.”

a line from the poem Mezzogiorno Alpino written after a short stay in Courmayeur, Giosuè Carducci reflects on the clear Alpine landscape, with the aim of highlighting the power of nature.

the trees stood as if to enjoy the pleasure of the sunlight penetrating their branches, absolute silence dominates, broken only by the rustling of the river water.

this might show how much interest and adoration sonetto shows towards things outside of the foundation

“So long lives this and this gives power to thee.”

a line from the famous poem Sonnet 18 by William Shakespeare, where he used this poem to praise the beauty of his beloved where their beauty is more preferable than a hot summer day. theres a bit of a change in the lines "So long lives this and this gives life to thee." the original line used life instead of power, it wouldn't really make sense if they used life for a buffer it would've been more of a healing skill so i get it

(i actually don't know what link this has towards sonetto soo fun fact sonnet 18 was about a man)

"I know the moon and this is an alien city”

the line is derived from the poem A London Thoroughfare 2 A.M by Amy Lowell the meaning of this poem is the feeling of being lost in a busy city, expressing emotions such as loneliness and being overwhelmed and how the only thing familiar to the writer was the moon. (aight im sorry idk how to word this one again another fun fact Amy Lowell is a sapphic and likes to call her muse or lover Lady of the moon)

“Each moment, now night.”

One of the lines from the poem Night by Max Weber (not the sociologist, also not sure on what to write since i dont actually know what the poem actually means i like to think that its about the silence and darkness of the night to show loneliness)

so basically most of these references loneliness and adoration towards the things the writer wrote about which might link to how sonetto might feel adoration and curiosity for the outside world and how she might've felt lonely in the foundation after being closed off from the outside world

(sorry if some words might not make sense and for how many things i've kept blank i failed literature so feel free to correct me im always up for discussion, its funny the way i found out most poets are queer are because of this)

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

essential reading.

Opinion - There is a Jewish Hope for Palestinian Liberation. It Must Survive. - by Peter Beinart

And perhaps one day, when it finally becomes hideously clear that Hamas cannot free Palestinians by murdering children and Israel cannot subdue Gaza, even by razing it to the ground, those communities may become the germ of a mass movement for freedom that astonishes the world, as Black and white South Africans did decades ago. I’m confident I won’t live to see it. No gambler would stake a bet on it happening at all. But what’s the alternative, for those of us whose lives and histories are bound up with that small, ghastly, sacred place?

"In 1988, bombs exploded at restaurants, sporting events and arcades in South Africa. In response, the African National Congress, then in its 77th year of a struggle to overthrow white domination, did something remarkable: It accepted responsibility and pledged to prevent its fighters from conducting such operations in the future. Its logic was straightforward: Targeting civilians is wrong. “Our morality as revolutionaries,” the A.N.C. declared, “dictates that we respect the values underpinning the humane conduct of war.”

Historically, geographically and morally, the A.N.C. of 1988 is a universe away from the Hamas of 2023, so remote that its behavior may seem irrelevant to the horror that Hamas unleashed last weekend in southern Israel. But South Africa offers a counter-history, a glimpse into how ethical resistance works and how it can succeed. It offers not an instruction manual, but a place — in this season of agony and rage — to look for hope.

There was nothing inevitable about the A.N.C.’s policy, which, as Jeff Goodwin, a New York University sociologist, has documented, helped ensure that there was “so little terrorism in the anti-apartheid struggle.” So why didn’t the A.N.C. carry out the kind of gruesome massacres for which Hamas has become notorious? There’s no simple answer. But two factors are clear. First, the A.N.C.’s strategy for fighting apartheid was intimately linked to its vision of what should follow apartheid. It refused to terrify and traumatize white South Africans because it wasn’t trying to force them out. It was trying to win them over to a vision of a multiracial democracy.

ADVERTISEMENT

Second, the A.N.C. found it easier to maintain moral discipline — which required it to focus on popular, nonviolent resistance and use force only against military installations and industrial sites — because its strategy was showing signs of success. By 1988, when the A.N.C. expressed regret for killing civilians, more than 150 American universities had at least partially divested from companies doing business in South Africa, and the United States Congress had imposed sanctions on the apartheid regime. The result was a virtuous cycle: Ethical resistance elicited international support, and international support made ethical resistance easier to sustain.

In Israel today, the dynamic is almost exactly the opposite. Hamas, whose authoritarian, theocratic ideology could not be farther from the A.N.C.’s, has committed an unspeakable horror that may damage the Palestinian cause for decades to come. Yet when Palestinians resist their oppression in ethical ways — by calling for boycotts, sanctions and the application of international law — the United States and its allies work to ensure that those efforts fail, which convinces many Palestinians that ethical resistance doesn’t work, which empowers Hamas.

The savagery Hamas committed on Oct. 7 has made reversing this monstrous cycle much harder. It could take a generation. It will require a shared commitment to ending Palestinian oppression in ways that respect the infinite value of every human life. It will require Palestinians to forcefully oppose attacks on Jewish civilians, and Jews to support Palestinians when they resist oppression in humane ways — even though Palestinians and Jews who take such steps will risk making themselves pariahs among their own people. It will require new forms of political community, in Israel-Palestine and around the world, built around a democratic vision powerful enough to transcend tribal divides. The effort may fail. It has failed before. The alternative is to descend, flags waving, into hell.

As Jewish Israelis bury their dead and recite psalms for their captured, few want to hear at this moment that millions of Palestinians lack basic human rights. Neither do many Jews abroad. I understand; this attack has awakened the deepest traumas of our badly scarred people. But the truth remains: The denial of Palestinian freedom sits at the heart of this conflict, which began long before Hamas’s creation in the late 1980s.

Most of Gaza’s residents aren’t from Gaza. They’re the descendants of refugees who were expelled, or fled in fear, during Israel’s war of independence in 1948. They live in what Human Rights Watch has called an “open-air prison,” penned in by an Israeli state that — with help from Egypt — rations everything that goes in and out, from tomatoes to the travel documents children need to get lifesaving medical care. From this overcrowded cage, which the United Nations in 2017 declared “unlivable” for many residents in part because it lacks electricity and clean water, many Palestinians in Gaza can see the land that their parents and grandparents called home, though most may never step foot in it.

Palestinians in the West Bank are only slightly better off. For more than half a century, they have lived without due process, free movement, citizenship or the ability to vote for the government that controls their lives. Defenseless against an Israeli government that includes ministers openly committed to ethnic cleansing, many are being driven from their homes in what Palestinians compare to the mass expulsions of 1948. Americans and Israeli Jews have the luxury of ignoring these harsh realities. Palestinians do not. Indeed, the commander of Hamas’s military wing cited attacks on Palestinians in the West Bank in justifying its barbarism last weekend.

Just as Black South Africans resisted apartheid, Palestinians resist a system that has earned the same designation from the world’s leading human rights organizations and Israel’s own. After last weekend, some critics may claim Palestinians are incapable of resisting in ethical ways. But that’s not true. In 1936, during the British mandate, Palestinians began what some consider the longest anticolonial general strike in history. In 1976, on what became known as Land Day, thousands of Palestinian citizens demonstrated against the Israeli government’s seizure of Palestinian property in Israel’s north. The first intifada against Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, which lasted from roughly 1987 to 1993, consisted primarily of nonviolent boycotts of Israeli goods and a refusal to pay Israeli taxes. While some Palestinians threw stones and Molotov cocktails, armed attacks were rare, even in the face of an Israeli crackdown that took more than 1,000 Palestinian lives. In 2005, 173 Palestinian civil society organizations asked “people of conscience all over the world to impose broad boycotts and implement divestment initiatives against Israel similar to those applied to South Africa in the apartheid era.”

But in the United States, Palestinians received little credit for trying to follow Black South Africans’ largely nonviolent path. Instead, the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement’s call for full equality, including the right of Palestinian refugees to return home, was widely deemed antisemitic because it conflicts with the idea of a state that favors Jews.

It is true that these nonviolent efforts sit uncomfortably alongside an ugly history of civilian massacres: the murder of 67 Jews in Hebron in 1929 by local Palestinians after Haj Amin al-Husseini, the grand mufti of Jerusalem, claimed Jews were about to seize Al Aqsa Mosque; the airplane hijackings of the late 1960s and 1970s carried out primarily by the leftist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and Yasir Arafat’s nationalist Fatah faction; the 1972 assassination of Israeli athletes in Munich carried out by the Palestinian organization Black September; and the suicide bombings of the 1990s and 2000s conducted by Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad and Fatah’s Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, whose victims included a friend of mine in rabbinical school who I dreamed might one day officiate my wedding.

And yet it is essential to remember that some Palestinians courageously condemned this inhuman violence. In 1979, Edward Said, the famed literary critic, declared himself “horrified at the hijacking of planes, the suicidal missions, the assassinations, the bombing of schools and hotels.” Rashid Khalidi, a Palestinian American historian, called the suicide bombings of the second intifada “a war crime.” After Hamas’s attack last weekend, a member of the Israeli parliament, Ayman Odeh, among the most prominent leaders of Israel’s Palestinian citizens, declared, “It is absolutely forbidden to accept any attacks on the innocent.”Tragically, this vision of ethical resistance is being repudiated by some pro-Palestinian activists in the United States. In a statement last week, National Students for Justice in Palestine, which represents more than 250 Palestinian solidarity groups in North America, called Hamas’s attack “a historic win for the Palestinian resistance” that proves that “total return and liberation to Palestine is near” and added, “from Rhodesia to South Africa to Algeria, no settler colony can hold out forever.” One of its posters featured a paraglider that some Hamas fighters used to enter Israel.

The reference to Algeria reveals the delusion underlying this celebration of abduction and murder. After eight years of hideous war, Algeria’s settlers returned to France. But there will be no Algerian solution in Israel-Palestine. Israel is too militarily powerful to be conquered. More fundamentally, Israeli Jews have no home country to which to return. They are already home.

Mr. Said understood this. “The Israeli Jew is there in the Middle East,” he advised Palestinians in 1974, “and we cannot, I might even say that we must not, pretend that he will not be there tomorrow, after the struggle is over.” The Jewish “attachment to the land,” he added, “is something we must face.” Because Mr. Said saw Israeli Jews as something other than mere colonizers, he understood the futility — as well as the immorality — of trying to terrorize them into flight.

The failure of Hamas and its American defenders to recognize that will make it much harder for Jews and Palestinians to resist together in ethical ways. Before last Saturday, it was possible, with some imagination, to envision a joint Palestinian-Jewish struggle for the mutual liberation of both peoples. There were glimmers in the protest movement against Benjamin Netanyahu’s judicial overhaul, through which more and more Israeli Jews grasped a connection between the denial of rights to Palestinians and the assault on their own. And there were signs in the United States, where almost 40 percent of American Jews under the age of 40 told the Jewish Electoral Institute in 2021 that they considered Israel an apartheid state. More Jews in the United States, and even Israel, were beginning to see Palestinian liberation as a form of Jewish liberation as well.

That potential alliance has now been gravely damaged. There are many Jews willing to join Palestinians in a movement to end apartheid, even if doing so alienates us from our communities, and in some cases, our families. But we will not lock arms with people who cheer the kidnapping or murder of a Jewish child.

The struggle to persuade Palestinian activists to repudiate Hamas’s crimes, affirm a vision of mutual coexistence and continue the spirit of Mr. Said and the A.N.C. will be waged inside the Palestinian camp. The role of non-Palestinians is different: to help create the conditions that allow ethical resistance to succeed.

Palestinians are not fundamentally different from other people facing oppression: When moral resistance doesn’t work, they try something else. In 1972, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, which was modeled on the civil rights movement in the United States, organized a march to oppose imprisonment without trial. Although some organizations, most notably the Provisional Irish Republican Army, had already embraced armed resistance, they grew stronger after British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians in what became known as Bloody Sunday. By the early 1980s, the Irish Republican Army had even detonated a bomb outside Harrods, the department store in London. As Kirssa Cline Ryckman, a political scientist, observed in a 2019 paper on why certain movements turn violent, a lack of progress in peaceful protest “can encourage the use of violence by convincing demonstrators that nonviolence will fail to achieve meaningful concessions.”

Israel, with America’s help, has done exactly that. It has repeatedly undermined Palestinians who sought to end Israel’s occupation through negotiations or nonviolent pressure. As part of the 1993 Oslo Accords, the Palestine Liberation Organization renounced violence and began working with Israel — albeit imperfectly — to prevent attacks on Israelis, something that revolutionary groups like the A.N.C. and the Irish Republican Army never did while their people remained under oppression. At first, as Khalil Shikaki, a Palestinian political scientist, has detailed, Palestinians supported cooperation with Israel because they thought it would deliver them a state. In early 1996, Palestinian support for the Oslo process reached 80 percent while support for violence against Israelis dropped to 20 percent.

The 1996 election of Benjamin Netanyahu, and the failure of Israel and its American patron to stop settlement growth, however, curdled Palestinian sentiment. Many Jewish Israelis believe that Ehud Barak, who succeeded Mr. Netanyahu, offered Palestinians a generous deal in 2000. Most Palestinians, however, saw Mr. Barak’s offer as falling far short of a fully sovereign state along the 1967 lines. And their disillusionment with a peace process that allowed Israel to entrench its hold over the territory on which they hoped to build their new country ushered in the violence of the second intifada. In Mr. Shikaki’s words, “The loss of confidence in the ability of the peace process to deliver a permanent agreement on acceptable terms had a dramatic impact on the level of Palestinian support for violence against Israelis.” As Palestinians abandoned hope, Hamas gained power.

After the brutal years of the second intifada, in which Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups repeatedly targeted Israeli civilians, President Mahmoud Abbas of the Palestinian Authority and Salam Fayyad, his prime minister from 2007 to 2013, worked to restore security cooperation and prevent anti-Israeli violence once again. Yet again, the strategy failed. The same Israeli leaders who applauded Mr. Fayyad undermined him in back rooms by funding the settlement growth that convinced Palestinians that security cooperation was bringing them only deepening occupation. Mr. Fayyad, in an interview with The Times’s Roger Cohen before he left office in 2013, admitted that because the “occupation regime is more entrenched,” Palestinians “question whether the P.A. can deliver. Meanwhile, Hamas gains recognition and is strengthened.”

As Palestinians lost faith that cooperation with Israel could end the occupation, many appealed to the world to hold Israel accountable for its violation of their rights. In response, both Democratic and Republican presidents have worked diligently to ensure that these nonviolent efforts fail. Since 1997, the United States has vetoed more than a dozen United Nations Security Council resolutions criticizing Israel for its actions in the West Bank and Gaza. This February, even as Israel’s far-right government was beginning a huge settlement expansion, the Biden administration reportedly wielded a veto threat to drastically dilute a Security Council resolution that would have condemned settlement growth.

Washington’s response to the International Criminal Court’s efforts to investigate potential Israeli war crimes is equally hostile. Despite lifting sanctions that the Trump administration imposed on I.C.C. officials investigating the United States’s conduct in Afghanistan, the Biden team remains adamantly opposed to any I.C.C. investigation into Israel’s actions.

The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, or B.D.S., which was founded in 2005 as a nonviolent alternative to the murderous second intifada and which speaks in the language of human rights and international law, has been similarly stymied, including by many of the same American politicians who celebrated the movement to boycott, divest from and sanction South Africa. Joe Biden, who is proud of his role in passing sanctions against South Africa, has condemned the B.D.S. movement, saying it “too often veers into antisemitism.” About 35 states — some of which once divested state funds from companies doing business in apartheid South Africa — have passed laws or issued executive orders punishing companies that boycott Israel. In many cases, those punishments apply even to businesses that boycott only Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

Palestinians have noticed. In the words of Dana El Kurd, a Palestinian American political scientist, “Palestinians have lost faith in the efficacy of nonviolent protest as well as the possible role of the international community.” Mohammed Deif, the commander of Hamas’s military wing, cited this disillusionment during last Saturday’s attack. “In light of the orgy of occupation and its denial of international laws and resolutions, and in light of American and Western support and international silence,” he declared, “we’ve decided to put an end to all this.”

Hamas — and no one else — bears the blame for its sadistic violence. But it can carry out such violence more easily, and with less backlash from ordinary Palestinians, because even many Palestinians who loathe the organization have lost hope that moral strategies can succeed. By treating Israel radically differently from how the United States treated South Africa in the 1980s, American politicians have made it harder for Palestinians to follow the A.N.C.’s ethical path. The Americans who claim to hate Hamas the most have empowered it again and again.

Israelis have just witnessed the greatest one-day loss of Jewish life since the Holocaust. For Palestinians, especially in Gaza, where Israel has now ordered more than one million people in the north to leave their homes, the days to come are likely to bring dislocation and death on a scale that should haunt the conscience of the world. Never in my lifetime have the prospects for justice and peace looked more remote. Yet the work of moral rebuilding must begin. In Israel-Palestine and around the world, pockets of Palestinians and Jews, aided by people of conscience of all backgrounds, must slowly construct networks of trust based on the simple principle that the lives of both Palestinians and Jews are precious and inextricably intertwined.

Israel desperately needs a genuinely Jewish and Palestinian political party, not because it can win power but because it can model a politics based on common liberal democratic values, not tribe. American Jews who rightly hate Hamas but know, in their bones, that Israel’s treatment of Palestinians is profoundly wrong must ask themselves a painful question: What nonviolent forms of Palestinian resistance to oppression will I support? More Palestinians and their supporters must express revulsion at the murder of innocent Israeli Jews and affirm that Palestinian liberation means living equally alongside them in safety and freedom.

From those reckonings, small, beloved communities can be born, and grow. And perhaps one day, when it finally becomes hideously clear that Hamas cannot free Palestinians by murdering children and Israel cannot subdue Gaza, even by razing it to the ground, those communities may become the germ of a mass movement for freedom that astonishes the world, as Black and white South Africans did decades ago. I’m confident I won’t live to see it. No gambler would stake a bet on it happening at all. But what’s the alternative, for those of us whose lives and histories are bound up with that small, ghastly, sacred place?

Like many others who care about the lives of both Palestinians and Jews, I have felt in recent days the greatest despair I have ever known. On Wednesday, a Palestinian friend sent me a note of consolation. She ended it with the words “only together.” Maybe that can be our motto.

#articles#definitely one of the best most extensive most personal most meaningful articles i've read this week#also addresses a LOT of uh. talking points recently

289 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello do you happen to have an explanation/definition of what pinkwashing is? don't trust googlie with a term so new and it does not line up with my understanding of the terms it's made up of (-washing = covering or changing the original or true depiction, pink- = I only know this term in politics from pink-collar and I am 99% certain it does not mean the same thing here)

Oh, yeah, you're absolutely correct about it not being a pink-collar thing.

For my followers, pink-collar refers to paid work outside the home that is traditionally held by women. The "pink" refers to women, femininity, etc. Just girly things, if you will.

In pink-washing, however, the pink refers to pink triangles, a prominent symbol of queer survival after pink triangles were used to mark sexual deviants (that is, gay men and trans women).

Pink-washing is the use of "we have queer rights, unlike those barbaric savages" to justify state violence.

Right now, the term is mostly coming up in discussions of Israel. In that specific context, it refers to the fact that Israel is far and away the most progressive and well-protected place for queer people of all sorts in the middle east. Which the Israeli government often likes to point to as proof that their brutal ethnic cleansing is a "necessary force" to protect queer lives from Islamist extremism.

It's a sort of, "look, I know what I'm doing is bad, but what they're doing is way worse: look at how badly they treat their queers. Obviously I must be violent to help civilize the animals, for the sake of their queers," often while actively killing queer civilians for being for the wrong race.

Unfortunately, pink-washing is itself strong evidence that a state devalues her queer citizens, thinking of them not as vulnerable people to be protected (as the state will insist is the case), but rather as tokens to be trotted out as proof of the state's "goodness." And should any queer person defy the role of "good little token," they are inevitably and severely punished. As they say (they being in this case an Israeli sociologist whose name escapes me entirely), "A trans woman in uniform will be given medical care, but a trans woman who refuses military service will go to a men's prison."

Pink-washing is also extremely, EXTREMELY common in the U.S. though this doesn't get as much air time lately as Israeli pink-washing. But, the U.S. very regularly uses pink-washing around gay (not so much trans) rights to justify both imperial and domestic violence. Even at the per-state level, it is extremely common for people in "progressive" states to say absurd shit like, "well we treat our gays with respect, unlike Alabama!" to thought-stop themselves from noticing how miserable their lives are as a direct consequence of state action (or even state inaction to stop violence, as is often the case with capitalism and policing problems).

There's also a significant problem in Canada with their pretty solid record on queer rights being used as a counter-argument to their mistreatment of indigenous peoples. This too is pink-washing.

Pink-washing also devalues to lives and specifically the queerness of the people being targeted for violence. You know. By killing them and stuff. But also by denying that they deserve the very right to life and safety that is supposedly the mission statement.

If the entire point of pink-washed violence really was queer liberation, they would suck at that because they keep killing all the queer people they don't fucking like.

51 notes

·

View notes

Note

i NEED to hear your thoughts on this:

Yeah, it seems like sending links isn't allowed in asks, which sucks.:/

I'm flattered you're asking for my opinion.🙃 I chose not to check out the post you described (turns out I already have that blog blocked, for good reasons I think.😂), because I really don't want to waste my energy on B/ler bs. I see red every now and then, but it's best for my mental health to ignore them as much as possible. Thankfully blocking tags/content/blogs works quite well here (though sadly there are loop holes of course). Not allowing anonymous questions helps too.

BUT I can offer a *little psychological analysis of the dominant B/ler culture on here. *Sits down by the fire place and plucks lyre*

*This got waaaay longer than planned, so get comfy, lol.😆 Turned into my manifesto or something. So might as well give it a fancy title.✨

B/ler Shippers And Narcissism

As we know, every Tumblr fandom has its fanon ships, and sometimes those ships become a mass phenomenon (usually it's m/m ships, though sometimes it's also other ships that become huge, like Zutara from ATLA for example). Sociologists, where are you? It's such an interesting phenomenon, especially the demographics of it.

ANY way, I never was as directly involved in and impacted by a ship war as much as in the ST fandom, so I can't compare. But one very disturbing thing I noticed within the B/ler fandom, is the amount of narcissism I see.

Now this is the moment for my disclaimer, because I don't want to generalise. I'm sure there are normal, nice B/ler shippers, but those stay out of the Mileven tag. I don't know how the algorithm of the "For you" suggestions works, but in my experience (and from what I heard also of others), engaging with ANY ST-content will fill it with B/ler posts. Which is why I stay out of there, and the same counts for any ST tag, tbh. And the vast majority of all those B/ler posts were full of Mileven hate, Mike hate, and even Eleven hate.

That's why I want to be clear that I'm talking about the B/ler fandom as I've experienced it. Take that with a grain of salt and don't come "Not ALL B/lers!"-ing at me.😂

Okay, with that out of the way, let's start. The way I see it, there are two ways of shipping B/ler:

1) You start watching the show. You like Will and Mike. You see that they are close friends. You romanticise their relationship (encouraged by Will's hinted at homosexuality in early seasons, or not). You create your fanon version of Mike, who loves Will back. You enjoy your fanon and prefer it over canon. The end.

There's obviously nothing wrong with that and that's the blueprint for most of fanon. I have my fanon ships too, or characters that I like, while I dislike canon or the whole franchise. But the thing with B/ler is that the majority of fans seem to have caught rabies. For them, it's more like this:

2) You start watching the show. You like Will. You see that Will is close friends with Mike. You romanticise their relationship (encouraged by Will's hinted at homosexuality in early seasons, or not). You create your fanon version of Mike, who loves Will back. You think your fanon is canon. You preach it and call yourself a "truther". You try to convert other people. You bully Mileven shippers. You hate Mike, but want him to be together with Will. You drag the actors into your fanon.

This type of B/ler shipper is remarkably like a narcissist (in an abusive relationship, or a cult leader, or megalomaniac politician. The world is full of them.)

We got:

Delusion

"Mike is gay and in love with Will 100%." Fact remains that there is not even a hint for this in the show, nor writer/actor/director hints. To claim that the exact opposite is true, is a complete rejection of canon and replacing it with fanon.

Inability to doubt and self-reflect

When someone refuses to admit an external reality, it's because they can't deal with their internal reality. Like for many of us, their ship has a deep personal meaning to them and they are attached to it. But they are incapable of even entertaining the thought that Will and Mike might not end up together in s5. Let alone that Mike is actually not in love with Will, nor ever was. Letting in that doubt would be too painful. It would mean that they were wrong. They would feel ashamed. They would feel betrayed.

Now I would say that I'm 99% sure that Mileven will be endgame, but I leave room for that 1% of doubt, because I simply don't know. I haven't read the script of s5. I haven't written it. I don't control the writers and runners of the show. I am human and I can err in my expectations and assumptions about others and their actions. We all do, but some people just can't deal with this truth, so they completely disconnect from it, and just act like they can't be wrong.

Hostility/Polarisation

Since upholding the delusion of a B/ler reality is EVERYTHING, people who doubt or negate it, are a menace. They need to be controlled. How do we do this? By shaming them, of course. B/lers mostly draw from the scapegoating palette of the universal abuser's tool box:

-Name calling (M/lkvan, and I've seen others) -Accusations/Gaslighting -Provocation -Criticism -Slander/gossip -Mockery/humiliation -Personal attacks -Invasion/hijacking of personal space (coughthemileventagcough)

By doing that, they have achieved to drive a great amount of Mileven shippers from Tumblr (I don't blame those who left at all). That way, the voices who are opposing their delusion become less and less, which is how they think things should be.

Contradictions/Making No Sense

Another thing that is true for all narcissists, is that they create an Upside Down version of reality (pun not intended, but it's fitting).

Since they believe in a delusion, they obviously don't have logic on their side. They have to change the goal posts all the time (classic narcissist behaviour) and will argue that blue is red. We got a ton of examples for this:

-Some say they love Eleven. They say they are feminist. Contradiction: They use Eleven to "prove" their point. They say she's ugly and looks like a boy. They say she needs to be independent, which means to break up with Mike (???). They say she's stupid/other ableist insults. They patronise/infantilise her.

-The above-mentioned user said Mileven shippers don't appreciate Mike. Contradiction: B/lers make up the vast majority of Mike haters. They say he abuses Eleven. They say he abuses Will. They say he abuses Lucas and Dustin. They say he abuses Max. They make everything he ever said and did about how he secretly loves Will or how he secretly doesn't love Eleven. They aren't even able to see the character Mike as he exists in the show.

-Some say Mike babies Eleven. Contradiction: They also say Mike puts her on a pedestal.

-Some say to ship Mileven is homophobic. Contradiction: They fetishise Will and Mike. They objectify Mike and turn him into a trophy for Will.

-And of course: They say Mike loves Will. Contradiction: There's no evidence for this.

And then there is just plain insanity, like:

-The "When blue and yellow meet in the west"-part of the Russian code is actually about B/ler

-The colours of Mike's s5 sweater represent the bisexuality flag

-The light!!!!

-Once I saw a B/ler claim that a riddle from ST promo contained a hint about B/ler. I asked them for more info and checked it out. But when I told them that I thought there were other possible solutions to that riddle, they shut down and simply insisted that their interpretation was the only truth and they were being queerbaited.🫡

💩

What I also find noteworthy is how above-mentioned user said that it's not just Mileven shippers who don't appreciate Mike, but also the GA - which I think stands for general audience? Because that's another classic narcissistic move to puff up their ego - claiming that they are the only one who has some sort of deeper insight into something or someone. It's not just arrogant, it's another wonderful upside down example, because the truth is that they don't even have a basic, superficial understanding of reality (like I said, that can't see Mike).

Projection/Gaslighting

Everyone does a bit of this, especially insecure people. But since this type of B/ler shipper we're talking about, is extremely insecure AND isn't capable of self-awareness, it runs rampant.

To project onto someone means to place feelings, behaviours, or attitudes onto them which you hold yourself (good, bad, neutral). Gaslighting is a form of projecting, which means to accuse someone of your own flaws and wrongdoings, in order to undermine their status/credibility and make them question their own perception/reality.

I already listed this among the shaming tactics, but wanted to point it out in particular, because it's so fitting to what you described. Saying that Mileven shippers and the GA don't appreciate Mike (probably because they don't understand him?) is such a perfect example of projecting AND gaslighting. Because, like I said, no one hates Mike Wheeler like the majority of B/ler shippers, lol.

So saying this serves so many purposes:

-Distracting from B/ler hate of Mike -Discrediting Mileven shippers to other B/ler shippers and possibly non-shippers -Shaming Mileven shippers who read the post -Possibly converting non-shippers and Mileven shippers (haven't read the post, but this definitely happens too) -Setting up B/ler shippers as some sort of "chosen group" that has exclusive insight into Mike's character (the irony!).🤣😂🤣

I mean, again, I didn't read the post, but to me it sounds quite like a little dictator right there.😆 Yes, it's "only" shipping, but it's definitely toxic and purposefully hateful as hell. And after all a fandom is like a mini-society. A group of people who inhabit the same social space.

So, in conclusion - the more I see and hear of B/ler shippers, the more I become convinced that this ship attracts mainly narcissistic and otherwise toxic people, who need a delusion to cling to and an excuse to abuse others. I didn't want to say it before, because it seems incredible for something as harmless as a fictional ship, and like I said, I don't want to generalise or demonise people. But the glass is full and this was the last drop.😬 My experience of 95% of B/ler shippers is as described above, and it is what it is. Someone needed to say it.

#Mileven#Pro Mileven#Mileven is endgame#Thank you for the ask I guess I needed to get this out xD#But in general besties please don't shove first-hand B/ler bs under my nose it's triggering ty#Mike#Eleven#Stranger Things#Meta#My meta#Anti-B/ler#Narcissism#Bullying#Fandom#Tumblr#And now back to fashion lol ❤️😋

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sept. 1 elections in the two eastern German states of Saxony and Thuringia have hit Germany like a cyclone, delivering the strongest-ever turnout for an extreme right-wing party in the postwar era. In Saxony, the hard-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) captured 31 percent, landing it narrowly behind the Christian Democrats (CDU), and in Thuringia, where the AfD is led by a twice-court-fined ideologue and outspoken neo-fascist named Björn Höcke, the party took 33 percent of the vote, the highest of any party, and thus also the mandate to form a government. The new populist party Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW)—a rightist offshoot of the Left Party that boasts anti-immigration planks and pro-Russian sympathies—landed in third place in both states.

Although it is unlikely that another party will partner up with the AfD in governance—they all say they refuse to do so—the results raise resounding questions for modern Germany. How can such an extreme hard-right party perform so well in postwar Germany, a country that, in both its eastern and western postwar incarnations, made preventing the return of a racist, authoritarian leadership its very raison d’être? Why is this phenomenon so pronounced and radical in the country’s east, the territory of former communist East Germany, almost 35 years after the Berlin Wall fell?

Germans are now asking: How could everything go so wrong? Several recently published books by German authors offer a reckoning—and some answers.

Proponents of eastern Germany, including literature scholar Dirk Oschmann and historian Katja Hoyer, authors of recent bestsellers blasting the overbearing West and those taking the West’s side—most of the mainstream media, including the leading weekly news magazine Der Spiegel—are practiced at lobbing rhetorical grenades at one another. On their own, these one-sided arguments miss the mark. But taken together, and combined with new material, they explain how the Germanies’ journey wound up such a wreck.

The cleft between eastern and western Germany—defined by the East’s extreme-right vote and preponderance of street violence, as well as the inability of the republic’s mainstream parties (with the exception of the CDU) to attract eastern members and votes—can be traced to the events following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Today’s hard-right sympathies in the East are largely, though not exclusively, spiteful backlash against the one-sided terms of West Germany’s annexation of the East, the West’s demeaning treatment of the easterners, the indignity that the economic transition inflicted on many eastern Germans, and the legacy of a suffocating, repressive dictatorship on its former subjects and their successor generations.

Detlev Claussen, an emeritus sociologist from Frankfurt, hit the nail on the head: “The AfD is the East’s revenge on the West, which is blamed for all the upheavals after 1990,” he wrote in an email to Foreign Policy. “The party’s personnel are right-wing extremists, the electorate only partly so, although it too appears indifferent to the accusation of Nazism.” Claussen pointed out that populists’ top issues were migration and the Ukraine war, two topics that are not relevant to regional governance. Rather, another topic is almost always predominant behind them, one regularly laced into the rhetoric of both the AfD and BSW: the unfair, demeaning terms of unification and the terms of the transformation since then. “The essence of the far-right vote is resentment against the West,” Claussen wrote.

The AfD vote in the East is complex: The five eastern states aren’t a seething bastion of foaming-at-the-mouth neo-Nazis—although neo-Nazis are among them. German studies show that about 8 percent of Germans—on both sides of the country—firmly subscribe to hard-right, racist ideological worldviews with a large additional segment in a gray zone that might well sometimes—but not always—support the likes of a right-wing dictatorship, street violence against politicos, racist laws, and antisemitism, too.

The numbers aren’t that much different than in other European countries, though they are in Germany currently higher than at any time since the Nazi era, particularly among young people, and also higher in eastern Germany than western Germany. About half of AfD supporters in the East—roughly 15 percent of the voting population—are rightists hardcore enough to actually lionize—rather than just accept—Höcke, who employs thinly veiled neo-Nazi language, soft-pedals Germany’s World War II crimes, and wants to “remigrate” non-native Germans living in Germany to their origin countries.

This radical segment is extremely alarming and constitutes a menace for people of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, Muslims, and leftist groupings, among others. They are the types who either perpetrate or condone far-right hate crimes, which have been on the rise for several years. Germany’s security services counted 25,660 such incidents in 2023. That’s an average of 70 a day Germany-wide and 22 percent more than in 2022. In May, a candidate for the Social Democrats was attacked and badly injured in Dresden, capital of Saxony, when pasting up EU election campaign posters. Experts say that this kind of violence hasn’t been so vicious since the 1990s, tagged today as “the baseball-bat years,” when pogrom-like attacks were carried out in the eastern states against migrants and others.

The 1990s is a good place to start to understand right-wing extremism in the East. The easterners had emerged from beneath the heavy hand of Soviet communism and were pleased to be rid of it, as well as welcoming to political and economic systems—liberal democracy and market capitalism—that they knew very little about. They were also unaware of how thoroughly the decades of authoritarian, militaristic education and indoctrination had penetrated their psyches and habits. East German communism was ethnically homogeneous and nothing if not narrow-minded; the very few non-Germans living in East Germany, such as African or Asian guest workers, reported regular abuse. When the wall fell, West German rightists—a generation before Höcke, who himself was born and raised in northwestern Germany—poured into the East to tap this raw energy and organize. When the easterners were confronted with refugee hostels in their communities in the 1990s, they often reacted with anger—and baseball bats.

One explanation of the racist violence and voting patterns today in the East lies in the 1949 to 1990 German Democratic Republic, and the values passed on from generation to generation. The young people today voting AfD and belonging to neo-Nazi street gangs are the children and grandchildren—or come from the same communities—of the bat swingers of the 1990s.

Today’s AfD hotspots are much the same as the sites of the 1990s’ violence. Over the years, one study after another has shown higher levels of racism and intolerance in the East, which the years of transformation have not diluted as the West’s implanted democracy teachers—university deans, politicos, foundation heads, CEOs, school principals, police chiefs—had intended and expected.

But the AfD phenomenon is more layered, since this explanation alone, broadly speaking, pertains to only about half of the constituency and very little of the BSW. It doesn’t explain how over three decades this ugly radicalism could fester and then suddenly explode again into the open. The East’s takeover by the West may have been sanctioned by the easterners in the democratic elections held in 1990—they voted for the CDU and Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who turbocharged the unification process, completing it in just 11 months after the fall of the Berlin Wall—but the pain and sacrifice of the economic transition ran deep and left scars that still smart today, even though eastern per-capita GDP has climbed over the years, today being about 80 percent of its western counterpart, with unemployment at just under 7 percent.

The disappointment and hurt of the easterners should not be underestimated. Kohl had promised them “flourishing landscapes,” but what they received was rampant unemployment: Three million people who had jobs lost them—and were thrown onto welfare rolls, which into the early 2000s equaled half of the East’s GDP. In the low-income labor market, the news was worse: Over 50 percent found themselves jobless. Those who could, including many young people, fled to the West, like the engineer who held the lease on my apartment in Berlin on Friedrichstrasse: He landed a job with BASF in Ludwigshafen in western Germany and never returned. The easterners were incensed at the deals that the Treuhandanstalt—the government agency that sold off East Germany’s enterprises—made for a song. The overnight introduction of the Deutsche mark in 1990 and the Treuhand’s fire sale ensured that western German firms and western German owners would sop up all of the eastern German business—and use the region for a supply of cheap, dispensable labor (which explains the lower per-capita GDP today).

The ostensibly burning topics of migration and the Ukraine war are largely red herrings, concluded sociologist Steffen Mau, author of a widely read new book on the East-West divide, entitled Ungleich Vereint: Warum der Osten Anders Bleibt (Unequally United: Why the East Remains Different). The eastern states have by far the smallest fraction of foreign nationals among the federal states, and those communities with the lowest numbers in the East tended to vote disproportionately higher for the AfD (which also scored well in depopulated rural areas, places with fewer women, fewer medical services, and higher unemployment). They are not threatened by the Ukraine war and have nothing to gain from admiring Russian President Vladimir Putin. The EU, which the AfD lambasts for milking Germany dry, has contributed immensely to the eastern states’ development since unification, to the tune of $53 billion (€48 billion). The German state shelled out nearly $2 trillion (€1.75 trillion).

Mau, in his nicely balanced study, concluded: “The economic transformation of the 1990s, which was associated with major restructurings and brought with it not only freedom but also economic declassification and insecurity, has made people [in the East] less willing to undergo further changes. Having already had to fundamentally change their lives and abandon biographical fixtures, larger sections of the population now strongly resist further impositions, be it growing diversity or socio-ecological transformation.”

None of this, of course, explains why such broad swaths of the population cast their ballot either for a party that tracks closely with neo-Nazis or another that looks to Russia for inspiration and not Brussels. This, though, is the hardest, most in-your-face way to strike back at the system that delivered them such disrespect and injury—and then blamed their backwardness for the mess.

“German democracy possesses its legitimation through its radical break with National Socialism,” Claussen wrote. “The election results in Saxony and Thuringia throw this foundation into question.” It’s a swipe that Germany’s mainstream elites aren’t going to shake off quickly.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ive discovered that doodling my blorbo from my games talking about what im studying as i study helps quite a bit actually.

So heres some of my doodles of Mirage Ultrakill having sociology opinions with explanations of the sociology stuff under the cut.

Doodle 1

Doodle 2

Doodle 3

doodle 4

Doodle 1

Secularization theory is a sociological theory which was originally thought up by Emile Durkheim. It basically says that as a society gets more modern, the religiosity of the people in that society declines, eventually leading to the complete disappearance of religion.

This theory was based on several inaccurate assumptions. Namely: people are less religious now than they were in the past, and scientific thought will inevitably lead to a decline in religious belief. As it turns out, neither of these assumptions are accurate...

But because this theory was introduced in the early days of sociology, it was just kind of accepted as fact even though there was no data to really support it.

Over time sociologists began doing studies on religiosity and found some major flaws in secularization theory. There wasn't evidence to support its conclusions despite decades of study, new religious movements continued to emerge in societies which were supposedly secularized, and religion remained an important influence in politics globally.

Anyways, Mirage Ultrakill strikes me as the kind of person who would hear about secularization theory and get excited because she's a bit of an asshole who thinks that religious belief is a comfort blanket shielding people from reality. Basically: Mirage Ultrakill strikes me as a reddit atheist.

Doodle 2

This doodle is right next to my notes on a concept coined by Thomas Luckmann called "invisible religion".

Don't get me wrong, Luckmann has made great contributions to sociology. He wrote The Social Construction of Reality which was hugely influential and also good shit. But... invisible religion does not make sense to me.

Rather than using a more accepted definition of religion, Luckmann made his own which asserted that religion is thought or action above an animal level. So, dear reader, if you are transcending your biological nature, then you are doing a religion. Eating with a fork? That's religion. Reading words? Religion.

To be fair to Luckmann, he was writing Invisible Religion at a time when Secularization theory was still widely accepted. At the time it was also believed that religion acted as the social glue that held society together, so Luckmann was trying to explain why society wouldn't fall apart as religion disappeared. And his explanation was that actually being human is religion.

But yeah, I reckon Mirage Ultrakill would be mean to him.

Doodle 3

This doodle is next to my notes on pluralism (pretty much just multiple religions existing in the same time/place). Specifically next to a section referring to pluralism as a "marketplace of ideas" which is a phrase I've heard far far too many libertarians throw around.

So basically, this doodle was a visceral reaction to seeing the phrase "marketplace of ideas". Honestly, it makes sense as a metaphor in this context as long as it isn't extended to far.

Doodle 4

This doodle was next to my notes on a section of my textbook that was talking about medieval monks (honestly why it was talking about that isn't too important, it was just some stuff about discrediting secularization theory). Anyway, did you know that a lot of Monasteries also brew a lot of beer and have done so since the Middle Ages? I think that's cool.

Anyway, this doodle happened because I was bored and Mirage Ultrakill strikes me as an underage drinker (which you minors out there should not be doing btw, it doesn't end well).

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hot take, Bones doesn't deserve the amount of hate they are getting. Some, I understand but the amount I'm seeing is ridiculous. They have multiple projects they're working on and I get it, rushing through BSD isn't great but they can't animate everything. Also... the way they animated Aku makes more sense. Hard to give a soft smile losing such a large amount of blood from your neck.

Mmh, I understand that it can be disheartening to see something you like so heavily criticized, but I do believe the studio is doing some major mess up this season and that people are legitimately enraged.

I'm the first one to say that we're all here to have fun and there's not really any point on focusing on things we dislike, but I think it's also valid to be upset when something you care about a lot is treated unlovingly, and people are in their own right to express such disappointment. Moreover, I feel like in this case there is a point in expressing one's disdain. It's important to be critic of the media we consume: we could all pretend to be satisfied and settle on complacency, but wouldn't that be deeply detrimental? Otherwise, sometimes it's important to acknowledge and even state loud that you don't like something, because it's only by recognizing something is wrong that people can get to work to change it and improve. If we all tamely pretended we liked the new season, if there was no one to ever evaluate its direction, animation quality, pace, there's little hope for any of them to improve, simply because there's no need to change something people are happy with.

Theodor W. Adorno is my favorite sociologist. He once said, “the splinter in your eye is the best magnifying-glass available”. With that he meant that pain is the greatest source of knowledge. Pain allows to see things that otherwise would go unnoticed: only by acknowledging pain one can understand that something is wrong, that something needs to be changed and improved. I think it's always important to state: “this is wrong”, because nothing can ever be fixed if you don't first recognize it's broken.

Personally, I do believe what Bones studio is doing is wrong. I don't think it's fair to have such a drastic quality drop with the last season just like it wasn't in the third. I don't think it's right to not have an original opening sequence nor an ending sequence (that we know of). I don't think it's right to have such a fast pace that you can't keep up with the events. I don't think it's right to have a season filled with reused animations. I don't think it's right to have very little animation to the point there's up to 36 seconds of the same static frame in a single scene. I don't think it's right to have a quality drop in the drawings and quality inconsistency between one episode and the next. I think it's outrageous that the Fukuchi vs. sskk fight was so poorly animated and completely striped of any emotion. I don't think it's right of them to assassinate Akutagawa's chapter 88 panel. But most of all, I don't think it's right to have a season come out three months after the other. I don't think that's in any way ethically sustainable, and I don't think anyone needed that. I don't think it's right that studios don't get that people don't want an uninterrupted flow of content, people want quality content, and it's important to say that, or they'll never get it. I think they messed up greatly with this season, and I don't think being working on multiple projects can use as an excuse in any way, because as a studio you should be able to tell when you've got your hands too full to handle another project without meeting the quality standard. If Bones studio was working on too many projects, they simply shouldn't have set this season up for release so early, because again, NO ONE needs a new season after just three months.

I can see why you would say that the way they animated Akutagawa's last words makes more sense. It definitely is more rushed, and ugly. I guess one could argue that it conveys how death is precipitous and unpleasant, and doesn't leave space for last words. ... But I highly doubt that much was intentional. The sskk scene in its entirety was so poorly curated that I can hardly see the direction make thematically relevant choices. Even in the rare hypothesis it was a conscious and intentional directing choice, the outcome was still extremely underwhelming, because the moment itself doesn't feel rushed in particular since it's coming right after an episode that was rushed in its entirety.

I agree Akutagawa's death scene in the manga isn't realistic the slightest. But realism in that moment was never what the reader was asking for in the first place! It's a moment of conclusion for Akutagawa. It's the end of his cruel and hated life, and the author chooses to end it in kindness. By giving him a moment to smile and redeem himself, the author is showing Akutagawa the compassion he never received in his violence ridden life. Death scenes in media are almost never meant to be realistic! Their main aim is to move the audience, not to portray a realistic death. It's part of the deal the audience makes with the media the second they start interacting with it, to suspend their belief in order to enjoy the media at its fullest. It's, fundamentally, the same reason why you wouldn't question the characters having superpowers.

All the same, if you find yourself to be on average satisfied with the anime, that's perfectly valid too!!! I'm sorry people's disappointment may have resulted disheartening, and I understand it's hard to avoid, but my best advice is to try and curate your own internet experience to be so that you see the least negativity as possible. You might want to consider blocking and unfollowing people whose comments you find unpleasant, even if it's just temporary for the time the season airs. If it gets too much, refrain from visiting the main tag on Wednesdays when new episodes drop if that can work for you. I recognize we as a fandom could work better to build a space that is enjoyable for people who are liking the new season and wouldn't want to meet so much negativity, and I'm the first to admit I've been quite inconsistent in tagging my posts recently, so in the future I'll try to tag negativity accordingly. I do appreciate you for reaching out and sharing your opinion Anon! Let's all work together to build a better fandom space for everyone (ノ◕ヮ◕)ノ*.✧

#bsd#bungou stray dogs#bsd s5#bsd season 5#bsd negativity#mine#people asks me stuff#Look‚ an opening sequence is the bare MINIMUM. I knew the season would have been a bad one the second I saw the opening.#If you don't have an opening ready‚ just postpone the release. Seriously. It's infinitely better than releasing an half assed season.#Nobody wants that. We're not getting a second chance to see chapter 88 panel animated‚ it's just gone.

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Invention of Hispanics: What It Says About the Politics of Race

America’s surging politics of victimhood and identitarian division did not emerge organically or inevitably, as many believe. Nor are these practices the result of irrepressible demands by minorities for recognition, or for redress of past wrongs, as we are constantly told. Those explanations are myths, spread by the activists, intellectuals, and philanthropists who set out deliberately, beginning at mid-century, to redefine our country. Their goal was mass mobilization for political ends, and one of their earliest targets was the Mexican-American community.

These activists strived purposefully to turn Americans of this community (who mostly resided in the Southwestern states) against their countrymen, teaching them first to see themselves as a racial minority and then to think of themselves as the core of a pan-ethnic victim group of “Hispanics”—a fabricated term with no basis in ethnicity, culture, or race.

This transformation took effort—because many Mexican Americans had traditionally seen themselves as white. When the 1930 Census classified “Mexican American” as a race, leaders of the community protested vehemently and had the classification changed back to white in the very next census. The most prominent Mexican-American organization at the time—the patriotic, pro-assimilationist League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC)—complained that declassifying Mexicans as white had been an attempt to “discriminate between the Mexicans themselves and other members of the white race, when in truth and fact we are not only a part and parcel but as well the sum and substance of the white race.”

Tracing their ancestry in part to the Spanish who conquered South and Central America, they regarded themselves as offshoots of white Europeans.

Such views may surprise readers today, but this was the way many Mexican Americans saw their race until mid-century. They had the law on their side: a federal district court ruled in In Re Ricardo Rodríguez (1896) that Mexican Americans were to be considered white for the purposes of citizenship concerns. And so as late as 1947, the judge in another federal case (Mendez v. Westminster) ruled that segregating Mexican-American students in remedial schools in Orange County was unconstitutional because it represented social disadvantage, not racial discrimination.

At that time Mexican Americans were as white before the law as they were in their own estimation.

The process would only work if Mexican Americans “accepted a disadvantaged minority status,” as sociologist G. Cristina Mora of U.C. Berkeley put it in her study, Making Hispanics (2014). But Mexican Americans themselves left no doubt that they did not feel like members of a collectively oppressed minority at all. As Skerry noted, “[the] race idea is somewhat at odds with the experience of Mexican Americans, over half of whom designate themselves racially as white.” Even in the early 1970s, according to Mora, many Mexican-American leaders retained the view that “persons of Latin American descent were quite diverse and would eventually assimilate and identify as white.” And yet “Spanish/Hispanic/Latino” is now a well-established ethnic category in the U.S. Census, and many who select it have been taught to see themselves as a victmized underclass. How did this happen?

In other words, a distinctive set of beliefs, customs, and habits supported the American political system. If the Cajun, the Dutch, the Spanish—and the Mexicans—were to be allowed into the councils of government, they would have to adopt these mores and abandon some of their own. It is hard to argue that this formula has failed. Writing in 2004, political scientist Samuel Huntington reminded us that

“Millions of immigrants and their children achieved wealth, power, and status in American society precisely because they assimilated themselves into the prevailing culture.”