#to be clear this is specifically about about *early* Anglo-Saxon England

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“The condition of the dowager queen in early Anglo-Saxon England seems less secure than among the Franks, but this appears to result from political implications rather than loss of the dignity of queenship. There were few active queen-regents, but the mature succession and semi-elective nature of Anglo-Saxon monarchy virtually eliminated this avenue of occupation for a king's widow.”

Julie Anne Smith, Queen-Making and Queenship in Early Medieval England and Francia / Stefany Wragg, Early English Queens, 650-850: Speculum Reginae

"Several mothers of kings were influential [in early Anglo-Saxon England] but examples of queens serving as regents seem rare […]. This is a major difference from, for example, Frankish queens, because of the nature of early English kingship. Frankish kings were more strictly patrilineal, descending in the first instance from father to son and, only in their absence, then to other male relatives. Kingship in early England, on the other hand, derived from two major principles. Firstly, a candidate for the throne had to be a male descended from the royal stock, usually with a mythic progenitor. Secondly, he had to be a proven and effective military leader. There are almost no examples of kings younger than their late teens. Ecgfrith of Mercia [son of Offa and Cynethryth] is a notable counterexample, but the circumstances of his accession were remarkable […]. Queens in early England, then, were sometimes mothers, though rarely continued as dowager queens, but were always defined by their close proximity to kings."

#anglo-saxons#english history#queenship tag#my post#to be clear this is specifically about about *early* Anglo-Saxon England#and there were exceptions (Cynethryth and Seaxburh of Ely; Seaxburh of Wessex who seems to have ruled in her own right; etc)#But regents for minors become a far more notable and prominent feature from the late 10th century#mainly beginning with Aelfthryth who functioned as regent for her son Ethelred#and whose role paved the way for Emma of Normandy#(Eadgifu is often viewed as a regent but this is misleading: her sons were adults. She was powerful but she wasn't ruling for them)#queue

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

you’re attacking that neopagan kind of birthstone post about druid plants, but could you please elaborate or at least clarify the explicit trope that is being used that has been historically weaponized?

I used to spend about a good third of my time on this godforsaken website attacking that idea, but sure, I'll do it again. This will be a bit of an effortpost, so I'll stick it under the readmore

There is a notion of 'celts' or Gaels as being magicial and somehow deeply in touch with nature and connected to pre-Christian worldviews that the people who decided to make up the "Celtic tree astrology" used. This is also why Buffy used Irish Gaelic as the language of the demons, why Warhammer uses Gaelic as Elvish, why garbled Scottish Gaelic is used by Wiccans as the basis for their new religious construct, why people call themselves Druids to go an say chants in bad Welsh in Stonehenge, or Tursachan Chalanais, or wherever, etc etc. This stuff is everywhere in popular culture today, by far the dominant view of Celtic language speaking peoples. Made up neopagan nonsense is the only thing you find if you go looking for Gaelic folklore, unless you know where to look, and so on and so on. I could multiply examples Endless, and in fact have throughout the lifespan of this blog, and probably will continue to.

To make a long history extremely brief (you can ask me for sources on specifics, or ask me to expand if you're interested), this is directly rooted in a mediaeval legalistic discussion in Catholic justifications for the expansionist policies of the Normans, especially in Ireland, who against the vigourous protestation of the Church in Ireland claimed that the Gaelic Irish were practically Pagan in practice and that conquest against fellow Christians was justified to bring them in like with the Church. That this was nonsense I hope I don't need to state. Similar discourses about the Gaels in Scotland exist at the same time, as is clear from the earliest sources we have postdating the Gaelic kingdom of Alba becoming Scotland discussing the 'coastal Scots' - who speak Ynglis (early Scots) and are civilised - and the 'forest Scots' (who speak 'Scottis' (Middle Gaelic) and have all the hallmarks of barbarity. This discourse of Gaelic savagery remains in place fairly unchanged as the Scottish and then British crowns try various methods for integrating Gaeldom under the developing early state, provoking constant conflict and unrest, support certain clans and chiefs against others and generally massively upset and destabilise life among the Gaels both in Scotland and Ireland. This campaign, which is material in root but has a superstructure of Gaelic savagery and threat justifying it develops through attempts at assimilation, more or less failed colonial schemes in Leòdhas and Ìle, the splitting of the Gaelic Irish from the Gaelic Scots through legal means and the genocide of the Irish Gaels in Ulster, eventually culminates in the total ban on Gaelic culture, ethnic cleansing and permanent military occupation of large swathes of Northern Scotland, and the destruction of the clan system and therefore of Gaelic independence from the Scottish and British state, following the last rising in 1745-6.

What's relevant here is that the attitude of Gaelic barbarity, standing lower on the civilisational ladder than the Anglo Saxons of the Lowlands and of England, was continuously present as a justification for all these things. This package included associations with the natural world, with paganisms, with emotion, and etc. This set of things then become picked up on by the developing antiquarian movement and early national romantics of the 18th century, when the Gaels stop being a serious military threat to the comfortable lives of the Anglo nobility and developing bourgeoise who ran the state following the ethnic cleansing after Culloden and permanent occupation of the Highlands (again, ongoing to this day). They could then, as happened with other colonised peoples, be picked up on and romanticised instead, made into a noble savage, these perceived traits which before had made them undesirable now making them a sad but romantic relic of an inexorably disappearing past. It is no surprise that Sir Walter Scott (a curse upon him and all his kin) could make Gaels the romantic leads of his pseudohistorical epics at the exact same time that Gaels were being driven from their traditional lands in their millions and lost all traditional land rights. These moves are related. This tradition is what's picked up on by Gardner when he decides to use mangled versions of Gaelic Catholic practice (primarily) as collected by the Gaelic folklorist Alasdair MacIlleMhìcheil as the coating for Wicca, the most influential neo-pagan "religion" to claim a 'Celtic' root and the base of a lot of oncoming nonsense like that Celtic Tree Astrology horseshit that started this whole thing, and give it a pagan coat of paint while also adding some half-understood Dharmic concepts (three-fold law anyone?) and a spice of deeply racist Western Esotericism to the mix. That's why shit like that is directly harmful, not just historically but in the present total blotting out of actually existing culture of Celtic language speakers and their extremely precarious communities today.

If you want to read more, I especially recommend Dr. Silke Stroh's work Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imaginary, Dr. Aonghas MacCoinnich's book Plantation and Civility in the North-Atlantic World, the edited collection Mio-rún Mór nan Gall on Lowland-Highland divide, the Gaelic writer known in English as Ian Crichton Smith's essay A real people in a real place on these impacts on Gaelic speaking communities in the 20th century, Dr. Donnchadh Sneddons essay on Gaelic racial ideas present in Howard and Lovecrafts writings, and Dr. James Hunter's The Making of the Crofting Community for a focus on the clearings of Gaels after the land thefts of the late 18th and early 19th century.

@grimdr an do chaill mi dad cudromach, an canadh tu?

283 notes

·

View notes

Text

So something has been bugging me for a while now about A and N’s backstories, and while I know not everyone will be as pedantic as me, as someone who loves history and has done a lot of writing, I feel that if you’re going to write a story about vampires and give them a specific time and date of origin, then there should be a certain level of research that goes into making that background authentic. I'm not saying that Mishka didn’t do any research. It just seems that in order to keep the vibe of a happy, mellow fantasy some of the less savoury aspects of A and N’s upbringings have been left out, and it's a shame. To be honest, it feels a bit disingenuous, and it feels like an opportunity got wasted.

Let me explain (long post got long, it's 2am)

Let's take A first, since the problem is simpler here.

A is the child of a Norman lord and an Anglo-Saxon noblewoman, born in the first generation after the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. A says that these were turbulent times but that their parents had a happy marriage. Which. While I’m sure a lot of unions in that time period made the best of it, I can’t help but feel this description strips away a lot of the context of what was going on at that point in history - and removes some of the complexity about A’s thoughts on love and relationships.

Basically, after he took control of the throne, William the Conqueror stripped many Anglo-Saxon lords of their lands and titles so he could give them to his Norman buddies instead - with the added bonus that it left the Anglo-Saxons without the means to raise armies against him. The sisters, daughters, and widows of the dispossessed Anglo-Saxons were then forced to marry these new Norman lords to legitimise their power, not infrequently after all of their male relatives had been slaughtered. It’s not as if Anglo-Saxon women weren’t used to being used as political chess pieces, but the years after the conquest were brutal. It’s why William had to build so many castles. The point that I’m trying to make is that even if A’s mother was content enough in her daily life, due to the power imbalance between her and her husband, it's very likely she had little choice in the matter. She may have seen a lot of her family killed for political reasons, with the knowledge that – in an age where women had very little protection outside of their paternal household – she might be next if she made too much of a fuss.

It would be fascinating to see what effect that tension has had on A 900 years later, or even to get an acknowledgement of how much times have changed, but we don’t. We don't see how their early years affected them, how they view relationships formed naturally instead of via political contracts. And I really, really wish we did. There is so much potential there.

But A is not the one keeping me up past 2 in the morning. It’s N, and the utter detachment their backstory seems to have from the period in history they lived in as a human. And it all stems from the fact that they came from the English nobility in the late 1600s.

See, the bulk of the problem is that English inheritance law at the time heavily favoured primogeniture, where a man’s wealth would go to his first-born son. Some dispensation was made for widows and other children, but the estates, assets, and most of the money had a very clear destination.

For one thing, this makes it kinda weird that N’s stepfather would have needed an heir before he could inherit, because except in extreme circumstances everything would have gone to him anyway. Don't get me wrong, this isn't the worst part of the problem, it’s just annoying when there are more plausible reasons for him marrying a woman already pregnant with another man’s child (old family friend wanting to save her from disgrace, needed the dowry to pay off gambling debts, there was a longstanding betrothal between them that would have been tricky to get out of, etc.).

No, the bigger problem with N’s backstory vs primogeniture is firstly that at the time the English aristocracy was racist af (still is tbh) and given his pretty obvious mixed-race heritage, no court would have agreed that Nate was a legitimate son (this is for a very special reason that we will be coming back to). I say Nate specifically here because primogeniture requires the eldest legitimate son. Nat wouldn’t have inherited at all, as women in that period passed from the guardianship of their father (or other male blood relative) into that of their husband after marriage, and only gained any kind of independence with widowhood. If N had been an only child, maybe they would have been treated as a special case, but unfortunately Milton exists: the eldest legitimate son who by law will inherit everything.

Now here’s the thing. Your average aristocrat in the 17th century is very obsessed with lineage and keeping the family line unbroken. He would not, therefore, send his legitimate heir to sea to be shot at or drowned before he can carry on the family name – that joy instead goes to any other sons who need their own profession, because again, they will get very little. Nat would have had a dowry, but would never have been expected to make her own living, so I'm going to focuson Nate for this next bit.

In Book 3, if you unlock his tragic backstory Nate tells you he joined the Royal Navy after Milton went missing so that he could go look for him. And, well. This is where his backstory as Mishka tells it completely falls apart. For two reasons:

1. Even in the modern day, you can’t ‘just’ join the Navy, and you certainly can’t just jump straight to being a lieutenant – it takes years of training and after a certain age they won’t take you because they won’t be able to mould you easily enough into a useful tool. For most of the Navy's history, the process was even more involved. It wasn’t an office job you could just rock up to and then quit if you felt like it, it was a lifetime commitment. Boys destined to be officers would be sent to sea as early as 12 to learn shipboard life, starting at the bottom and moving up the ranks. These were gained by passing exams and by purchasing a commission – which is why you generally had to come from wealth to be an officer at all. Once you get to lieutenant you're responsible for a lot of people, and might be tasked with commanding any captured ships alongside the daily running of yours - it was not an easy job.

2. Even as a lieutenant (one rank below Captain, with varying levels of seniority) it’s not like you can just go where you want. In the 1720s British colonies already existed in India, the Caribbean, and up the entire eastern seaboard of North America and into Canada, and the Navy was tasked with protecting merchant shipping along these seaways (and one trade in particular that we’ll be getting to, don’t worry). Nate could have ended up practically anywhere in the burgeoning empire. He would not have been able to choose whom he served under, and would not have been able to demand his superior officer go against orders from the admirality to chase down one lone vessel because he thinks another one of the admirals might be a bit dodgy. It could not have happened.

Besides these impracticalities, there’s a far easier way for the child of a wealthy man to get to a specific point on the far side of the globe to look for their lost sibling, which is the route I assume Nat took sine she couldn’t have joined the Navy (yes she could have snuck in but she’s specifically in a dress in the B2 mirror scene so). All they'd have to do would be to charter a ship and tell the captain where to go, which is the plot of Treasure Island. It's quicker, less fuss, with less chance of things going wrong. It's even possible in the age of mercantilism that the Sewells had some merchant vessels among their holdings that could be diverted for the task. Why go through the hassle of joining the Navy and potentially ending up on the wrong side of the world when you can just hire a ship directly?

If Nate does have to be in the Navy (and let’s face it, it’s worth it just for the uniform) then it's far more plausible is that, as the illegitimate son who would not inherit because of racism etc, he got sent to the Navy as a boy and rose through the ranks to become a lieutenant. When he got news of Milton’s disappearance not far from where he was stationed, he begged his captain to go investigate in case whatever happened turned out to be the symptom of a bigger problem. Like pirates.

I like this version better not just because it makes more sense, or because it keeps Nate’s situation re: inheritance closer to Nat’s and therefore makes their stories more equal, but also because it adds a delicious amount of guilt to Nate’s need to find his brother. We know his entire crew died looking for answers, because he was selfish – that’s roughly 100-400 lives lost because of him, and we know that sort of thing eats at him.

So that's one side of the story, but if Milton wasn’t in the Navy, what was he doing on the other side of the Atlantic in the first place? Well, this is where we come to the biggest elephant in the room regarding N’s backstory as a member of the 17th century English aristocracy and potentially as a naval officer: the Atlantic Slave Trade. If you are wealthy in 17th century Britain it's more than likely that your wealth comes either from the trade itself, or from the products made with the labour of enslaved people. If you are wealthy, you want to protect your assets from attack by pirates or foreign powers so you don't become less wealthy, and that is what the Navy is for.

Regardless of N’s own views on slavery at the time – and any subsequent changes in opinion – it’s likely their family owned or had shares in slave plantations in the Americas. As distasteful as it is, it makes far more sense that Milton was on a trip to check the family’s holdings when his ship - specifically a merchant vessel - went missing. From a pirate perspective, a merchant ship would make a much better target than a Navy vessel, being slower, more likely to have valuable cargo, and less likely to have marines or a well-trained broadside.

It's not surprising that Mishka left out the subject of the slave trade given her tendency to skirt around darker subjects and general blindspot for racial politics, but it is nuance that, if it was there, would create a more grounded and coherent backstory for N that doesn’t have quite so many holes. Like with A being the child of an invader and his war bride, we could get some deeper thoughts from N about their place in the world - How do they feel to have grown up so privileged when others who looked like them were regarded as literal property? How did they feel being part of the system that made it happen? Did it inform their compassionate nature? Is it still a source of guilt or someithng they've tried to make up for?

I'm not sure where I was going with all of this. It's late, my sleep pattern is fucked. The tl;dr is that giving the vampires' backstories historical context would make them feel more multifaceted and would give opportunities for character growth that are instead missed because of a desire for a more sanitized version of the past.

#thank you for coming to my ted talk#the wayhaven chronicles#twc#a du mortain#adam du mortain#ava du mortain#n sewell#nate sewell#nat sewell#it's annoying because it’s such a small tweak in the grand scheme of things#If she didn’t want unfortunate implications she could have made N from a century later when the navy was actively trying to stop slavery#A could have been from a 50 years earlier to tie his whole family’s demise into the subjugation of the english after the battle of hastings#or a century later when the two courts had mostly integrated#mishka made choices#they deserve to be given more substance than mere aesthetics#you can tell it’s late I’m using long words

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

TOLKIEN, MYTH AND THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY

A week ago I wrote a post about my excitement in discovering just how much Tolkien took inspiration from Anglo-Saxon poetry.

I was so lost in my little over-emotional bubble that I was genuinely a little surprised when a few people expressed their disappointment in discovering that "The Lord of The Rings" wasn't wholly original. It makes sense, though, so I thought I'd address it.

These are @fortunes-haven ' s tags:

@sataidelenn already wrote an interesting reply, but I'd like to approach the question from a different point of view. Why? Because the first thing I thought about when reading this comment was how I myself have grumbled under my breath about having to wade through someone's "personal mythology smoothie", only I wasn't reading Tolkien. I was reading T. S. Eliot.

Now, I want to preface this by making it clear that I am well aware Tolkien is by no means a modernist. He did, however, write LOTR in England in the late 30s. He was part of the same culture, the same society, and above all the same historical context that produced "The Waste Land" and "Ulysses", and I think we should take that into account when we discuss his work.

Because by the time Tolkien published LOTR, Joyce and Eliot and Yeats had already discussed and applied the mythic method. Was Tolkien aware of their debates? Did he read and appreciate their books? I have no clue. It would take some research to find out, research I currently (unfortunately) don’t have time for. But I do not think it a stretch to suggest that Tolkien might have been moved by the same need that drove other writers to look back at myth, although in very different ways.

Why did Joyce and Eliot feel compelled to return to the narrative roots of mankind? Why did Yeats devote so much time to Celtic lore? Why did Tolkien write a new epic and base it on the Saxon world?

The answer is the same: because they lived at the start of a century that posed more questions than ever, but provided no answers; a century when time and the human mind and the very structure of matter had ceased to be solid, defined, a foundation to rely on; a century torn apart by brutal, inhumane, sensless war.

When you can't find answers in the present and the future is so uncertain it's laughable, you look to the past. Because the thing is, we can talk about "personal mythology" all we want, but myths are never personal. They are universal. They are tied to a specific cultural context, certainly, but they exemplify emotions, truths and tragedies that are common (or supposed to be common) to all humankind, beyond space and time. Myths are supposed to be eternal.

They are also a very effective shorthand to communicate rather complex concepts.

I can write five pages telling my girlfriend that she makes me feel safe, that she is something I've longed for and fought to gain, something I've dreamed about but that I'm scared I'll lose. I could, and I probably wouldn’t be able to convey exactly what I mean.

Or I could say "She is my Ithaca" and you would get it, wouldn’t you?

There are whole books that try to explain the symbolism behind "The Green Knight", but Eliot can offhandedly mention a chapel and he has basically evoked the whole original poem plus the centuries of scolarship that followed.

Tolkien could have had his characters recite long monologues about how they feel like their world has been lost. Instead, he has one of them sing a song by the campfire. An 8th century song, about a warrior in exile. He achieves in a couple of lines what could have taken him a whole book to convey, and he does it in a way that goes straight to the heart, even if we don't know exactly why.

And that's the thing: not all of us spend years researching myths and old poetry. Certainly we don't do it when reading LOTR for the first time, especially if that's when we are 13 or 10 or 8 years old. But we get it anyway. We know myths, especially Western myths, one way or another, as if through cultural osmosis. We understand myths from other cultures too- we may need a bit of context, but we do- and often we find that the bones of the stories are similar, across oceans and centuries.

That means that using myths as the building blocks of your story is an amazingly effective way to cut to the quick, to get to the core of what the narrative is aiming at.

I have seen so many people talk about the feeling they get when reading LOTR, or even just thinking about it: that nostalgia? That bittersweet hurt? That longing for something bright and lost, for a star or a jewel or a land beyond the sea? That, right there. That is what Tolkien achieves by telling stories inside stories, by having his words have a meaning and weight that we would associate with a bard or a preacher, not a fantasy writer. And, as I have discovered recently, it's almost exactly the same feeling you get when reading Saxon poetry.

It's almost as if he chose it on purpose, isn’t it?

That's not all, though.

As both people tagged above(and many others, myself included) have already written, Tolkien doesn’t just use myths as building blocks. He alters them.

Yes, Frodo's hero's journey is not typical. Yes, there are a lot of similarities between the last part of LOTR and the Odissey, but they are not quite the same.

That's because Frodo is not, and can't be, Ulysses. He isn’t a warrior crowned with glory and cunning who reconquers his home and that leaves it because a god has promised him peace if he does. He is a mutilated soldier coming home from the trenches, only to find that he no longer belongs in the home he has bled for.

Frodo is a new hero, for a new age (just like Ulysses was a new hero for a new age, which I rather think is one of the reasons Joyce chose him as the model for his novel. The Odissey was already subversive in and of itself. "An odd duck", as @sataidelenn put it.)

We have to understand just how traumatic WWI was. It's a shift, a break so immense that it changed society, politics, culture, family structures, the idea of hero and even of manhood. The Western World was not the same after 1918. Of course art changed too.

Would Tolkien have written LOTR had he not fought in that war? Probably. But it would have been a very, very different book. The way it deals with war, technology, trauma, peace and friendship-all the things we love about it- are direct fruits of that conflict. I think the way myth fits into it is, too.

I can understand being disappointed that not everything in Lotr is wholly new, wholly Tolkien's invention. It didn’t even occur to be to be, though, because I am used of thinking of it in these terms.

All the myths he uses- from Kullervo to Ulysses to Beowolf to medieval fairy tales- are means to tell a new story. They come back to life, and while we perceive how timeless they are, they end up telling us something that is rooted in time. A new English epic, yes, but very clearly an epic of England between two world wars. A 20th century heroic tale which offers a desperate, brave hope for the future. How can we not love it?

And look, I might joke about personal mythology smoothies to myself all the time, but the reason I keep reading and studying Eliot and Joyce and Yeats is that they do have something new to say, something amazing. You can take them or leave them, love them or hate them, but "unoriginal" is not an adjective you can, in good conscience, apply to their work.

I think, in a weird way, Tolkien is the same.

"In manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity, Mr. Joyce is pursuing a method which others must pursue after him. They will not be imitators, any more than the scientist who uses the discoveries of an Einstein in pursuing his own, independent, further investigations. It is simply a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving shape and significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history. It is a method already adumbrated by Mr. Yeats, and of the need for which I believe that Mr. Yeats to have been first contemporary to be conscious. Psychology (such as it is, and whether our reaction to it be comic or serious), ethnology, and The Golden Bough have concurred to make possible what was impossible even a few years ago. Instead of narrative method, we may now use the mythic method. It is, I seriously believe, a step toward making the modern world possible for art." –T.S. Eliot, from Ulysses, Order, and Myth (1923)

#tolkien#lotr#tolkien meta#literature#myth#does this make sense? I hope it does#I really wanted to reply earlier but alas life#you can tell I have put a tiny bit of thought in this over the years uh

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Backwoods Dungeon

Backwoods Dungeon, by Dustin Graham. After no little deliberation I’m giving this one a solid four out of five stars. It’s a good read and an entertaining story, but it doesn’t give me the mental sparkle of Grand Theft Sorcery or Janet Kagan’s Mirabile.

First, the good points. Preexisting and fairly healthy relationship between Theo and Rio. Husband and wife as battle buddies! (Eventually.) And both of them try to do the right thing, even if it’s not easy. Including risking their own lives to rescue other people captured by the imps. Mind they do it heavily armed, which I also approve of. The existence of a broken System bringing magic and classes to people under specific conditions is an intriguing departure from the usual System Apocalypse setup. There’s plenty of action, creative use of magic and abilities along with modern items, and when the characters make mistakes (some near-lethal) it’s not hard to consider the situation and what they knew at the time and say, “Yeah, I’d probably have made that mistake too. Or something worse.” The good guys pull off a win, or at least save as much as they can. It has a decent ending.

Now for the points that made me go “um.”

The first one’s not one relevant to the plot... except it kind of is if you’re trying to retcon “there was a demon invasion and System with magical classes in the historical past”. Which is stated to be about a thousand years ago. Our modern people find a journal written by someone who fought in the last part of that invasion... written in English. Which one of the characters refers to as “kind of Shakespearean,” and mentions the writer spent a lot of time writing sonnets about his girlfriend.

My amateur historian brain: (Trip, fall down entire flight of stairs to the hard concrete basement.) Ow ow ow ow ow.

Ooookay. A thousand years. 1024 AD is decades before William the Conqueror invaded England and the Saxon and Norman languages collided to eventually create English. Sonnets? Crafted in Italy in the 13th century; didn’t get into use in England until the 1600s. 1024 AD is too early for Chaucerian English (1300s); Shakespearean is late 1500s. On top of all that, even after it was mongrelized into being English was little-known outside, y’know, England, until the 1600s on. Meaning if the journal writer knew any variety of English (or Anglo-Saxon) then the demon invasion happened in England and we would know about it because the monks kept historical records. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It’s a thing.

Me: I say again, OW.

Second grump point comes from my having poked my nose into a lot of biology and cultural history. Theo runs into imps out to kill him or torture him to death, yet doesn’t give much thought to, “Okay, this is a raiding party out to create mayhem, where are the rest of them?” Because when you’re dealing with enemies intelligent enough to use weapons, there usually is a “rest of them” - a lot more, including more experienced if a bit creaky warriors who will come out once you’ve shown you can deal with the young hotheads, and then curb-stomp you.

The imps don’t actually have a society, but that would be my baseline first assumption. Meaning if I dealt with six murdering aliens in the woods, I’d expect the actual problem to be at least a hundred times bigger, not one you could wall up a tunnel entrance and forget about. You have to tell your neighbors about this!

Third... eh. Typo daemons haunt us all, I’d be first to admit that. But when you title a chapter with Theo’s POV and reading it makes clear it’s actually Rio’s, that jars. There were other annoying typos and words split by dashes in awkward spots.

Fourth, the ending felt a bit of a letdown, especially with the multiple (five?) short epilogues making it clear the demons are still out there.

All told? A long, straightforward story that will entertain you for hours. But I hope the writer has a sequel in mind to tie up some loose ends!

1 note

·

View note

Text

I think one of the things that people often forget (or don't even know) when discussing the quirks of the English language is its really strange history.

Great Britain, Ireland, and everything in that general area used to be a bunch of random islands that no one except the people living there cared about. They didn't speak English back then. Instead, they spoke something called Brythonnic or Brittonic, which was named in reference to the ancient Britons. Then, the Romans decided that they wanted to conquer a sizeable chunk of the known world for a lark and set up fortifications on those "random islands that no one except the people living there cared about." Notably, that also wasn't the advent of the English language because English is a Germanic language, not a Romance language or a Brittonic language.

For that, we need to look to the 5th century CE, when a bunch of guys called the Anglo-Saxons (named Anglo because they were ancient English people, and Saxon because of their swords) showed up. They spoke Old English. The real Old English, not the Middle English of Shakespeare that everyone mistakenly calls Old English. The Roman Empire was on its last legs at that point, but it still had a pretty outsized impact on the development of the English Language.

See, the Anglo-Saxons wrote their language with a system called the runic Futhorc, named so for its first six runes; ᚠ - Feoh, ᚢ - Ur, ᚦ - Thorn, ᚩ - Os, ᚱ - Rad, and ᚳ - Cen. This was a perfectly serviceable way to write Old English, and people did so for centuries. However, the cultural power of Latin and its alphabet was far more than that of the Futhorc or its sister system, Younger Futhark (the Younger Futhark having been used in Scandinavian areas). This means that many of the Old English manuscripts were written with a system completely unsuited to English as a language. Latin G had to pull double duty for ᚷ - Geofu (modern G) and ᛄ - Gear (modern Y) as Y was only considered a vowel at that point, and J (used in many non-English languages for the sound of the modern English Y) didn't exist yet. W, not a sound found in Latin, had to either be transcribed with uu/vv (as U and V were once interchangeable; hence the name Double-U) or with ƿ - Wynn, the latter of which was based on the rune ᚹ - Wyn. The two sounds that are today represented by th also had to have new letters made for them; spawning þ - Thorn from the rune of the same name and ð - Eth (pronounced with the th in that).

Now, about two paragraphs ago, I mentioned Middle English, and how it's a different thing from Old English. How exactly did Old English become Middle English? Was it a long slow process, where slow linguistic shift resulted in a--okay, yeah, you got me. It's not that. It was the French. The Duke of Normandy/William the Conqueror, to be specific, who decided that he wanted to conquer Britain and succeeded. To be clear, there was already some influence from continental Europe and Scandinavia--like with Alcuin of York living it up in the court of Charlemagne in the 8th century and the Danes kinda invading England slightly before the Norman Conquest--but never anything as substantial as The Conquest.

And this isn't even mentioning the fact that there's about seven or eight centuries between the Norman Conquest and the rise of very early examples of what could be recognized as "Modern English"; or the advent of the printing press and how continental European printers didn't have þ in their typesets, leading to its eventual falling out of use in English; or some of the other impacts of Latin on English; or numerous other things that contributed to why English is Like That. I've mostly talked about all this because there's one thing in particular that I want to clear up. People often like to joke that English goes around mugging other languages for spare grammar, but it's a whole lot closer to "other languages used to go around beating up English and then shoving spare grammar into its pockets for shits and giggles."

0 notes

Text

It is my observation, especially following October 7th, that Leftists do NOT actually support indigenous land back movements.

At all. Period.

Leftists just love to USE indigenous people that they can define as "oppressed victims" within their extremely narrow definition of that term. That is, Leftists love to FETISHIZE non-white indigenous people who have not yet achieved sufficient success in their land-back goals.

But once these indigenous non-white people who have been classed as "oppressed victims" start to succeed in their land back movements, as Jews have done, Leftists stop fetishizing them and start attacking them.

This pattern is also true with white indigenous people, such as Scottish, Irish, and Welsh people of Celtic origin.

Like, remember when Humza Yousaf went on a mask-off rant about how there are too many "White" people in positions of power in Scotland? This is a great example of how Leftists will abandon indigenous people once they feel they have achieved a sufficient level of success.

The people of Celtic origin who are indigenous to Scotland, and who have been persecuted ever since Emperor Fucking Claudius of Rome launched his invasion of Britain in 43 CE -- yes, those indigenous Celtic people of Scotland are considered White.

80 years later in 122 CE, Emperor Hadrian began construction on Hadrian's Wall to keep the indigenous tribes of Scotland north of the Roman province of Britannia.

About 250 years later in the late 300s CE, the Western Roman Empire started to contract (ultimately falling to Germanic "Barbarian" tribes in 476 CE), and this led to the fall of Roman Britain in the early 400s CE. As Roman forces left Britain, this led to a power vacuum, which allowed for the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain in the mid-400s CE. This set up a conflict between Scotland and what would become England (aka Angle-Land, or Land of the Angles) that lasts to this day.

Sorry to break it to Humza Yousaf, but indigeneity doesn't presuppose a specific skin color. But Yousaf is too corrupted by Noble Savage bigotry to acknowledge this.

This case is worth noting because the reason Yousaf was able to get away with complaining that there are too many Celtic people in Scotland is precisely because Scottish people have achieved enough of their goals fighting against England for Leftists to abandon them. And Leftists are not only abandoning them -- Leftists like Yousaf are outright attacking them.

Again, Leftists ONLY give a shit about indigenous rights and land back movements if they can class these indigenous people as "oppressed victims". Indigenous people are "supposed" to exist solely as inspiration porn for depraved Leftists to idealize.

Once these "oppressed victims" start to reclaim their indigenous land, and (most importantly) start to advance in society, Leftists turn on them.

Leftists are trapped in a kind of Drama Triangle. They jerk off to fantasies of "Rescuing" these "Victims" from evil "Persecutors", and once they can't live out this self-insert savior fantasy, they have no more use for these indigenous people they once claimed to support.

We must remember -- Antisemitism and Philosemitism are just two sides of the same bloody sword.

That is why Dara Horn's title, People Love Dead Jews, is so accurate. The only time that Leftists have ever "loved" Jews is after we were genocided by the Nazis, because Leftists could then define a clear "Victim" and "Persecutor" dynamic between Jews and Nazis, and Leftists could imagine themselves as "Rescuers" in that dynamic.

Leftists love Jews ONLY when Jews are dying or dead, and ONLY when we are slaughtered by a group of people that Leftists can definitively class as a "Persecutor."

For instance, according to this Leftist paradigm, White Supremacists should NOT be "allowed" to murder Jews, because White Supremacists are classed as "Persecutors".

Although even that dynamic is changing, judging by how many Leftists celebrated when Robert Bowers, a white supremacist Christian, (mis)quoted the Gospels (he stated, "Jews are the children of Satan, John 8:44"), and then went on a murderous rampage while screaming "all Jews must die." He slaughtered eleven Jews at Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh on October 27, 2018, and wounded many more.

And immediately following the White Supremacist terrorist attack, many Leftists CELEBRATED that atrocity. I have the screenshots.

Now, according to the Leftist paradigm, Islamists like Hamas ARE "allowed" to rape, torture, and murder as many Jews as they want, because Leftists consider Islamists to be "Victims" in their Drama Triangle. Leftists also consider Islamists to be more "Victimy" than Jews, and so in that dynamic where Leftists maintain their place as "Rescuers", Jews become "Persecutors" and Islamists are "Victims."

This is why Leftists around the world celebrated the October 7th pogrom, where Hamas terrorists raped, tortured, murdered, and enslaved 1400 Jews.

Leftists applied this depraved "Drama Triangle" paradigm to Hamas' massacre. Leftists stood in the middle in their self-appointed position as "Rescuers", and declared that the people they class as "Victims" should be allowed to brutally slaughter the people that they class as "Persecutors."

It is a SICK and MONSTROUS "game" in which Leftists maintain control, and pit Jews and Muslims against each other in a battle for who is more "oppressed".

This is also why Leftists refuse to study the 1400 year history of Arab Colonialism. They don't want to learn history because it will challenge their false "oppressor/oppressed" paradigm for how they believe the world works. They refuse to learn about the Rashidun, Umayyad, and Abbasid Caliphates. They refuse to learn about the Ottoman Empire. They refuse to think about what languages the indigenous peoples in MENA countries spoke before they were forced to speak Arabic and convert to Islam at swordpoint. The Lebanese people, for instance, are NOT Arabs. They are descendants of the Ancient Phoenician people who remained in the region, and didn't escape to found Carthage (in modern day Tunisia) due to trade disputes with Egypt. Lebanese people speak Arabic due to Arab Colonialism; it is not their indigenous language.

What I've learned, especially since October 7th, is that Leftists HATE Jews when we win. Leftists "love" Dead Jews, but Leftists hate Thriving Jews. Leftists hate Successful Jews. The only time they "love" us is when we lose to such a massive degree that we lose EVERYTHING like we did in the Shoah. And even then, their "love" is not actually love -- it is PITY.

Leftists' only currency is being the "Rescuer" in a Drama Triangle, and they can't "Rescue" someone who doesn't fit their narrow, toxic, destructive definition of "Victim."

So, here is what this means for all other land back movements. And y'all better take note:

LEFTISTS WILL ABANDON EVERY OTHER INDIGENOUS GROUP WHO BEGINS TO SUCCEED IN THEIR LAND BACK GOALS.

If the Māori people in Aotearoa, or the Indigenous Australians, or First Nations tribes in the Americas, or any other indigenous group start to achieve success in their land back movements, the Left will similarly turn on them and try to destroy them.

Why? Well, again, because indigenous people are only useful to Leftists as inspiration porn.

I really hope that other indigenous people are paying attention to what Leftists are doing to the Jewish people. Because as we know from thousands of years of history, what starts with the Jews never ends with the Jews. We're always the first to be slaughtered, but we're never the last.

Am I the only one who thinks that if Israel wasn't a Jewish state, the left would praise it as a very beautiful thing? There's the obvious reason that it's a decolonization project, which leftist typically love, but it's deeper than that.

Israel has one big culture, the Jewish culture, but it's also influenced by many different cultures because of thousands of years of diaspora. It's a beautiful collection of many cultures coming together binded by another. People are finally returning to their homeland, but influenced by different cultures across the world. It's multicultural while being one, together. That's what the left likes. But no. Instead, they say, "stolen culture".

#jews are indigenous to israel#land back movements#leftist antisemitism#islamist antisemitism#christian antisemitism#noble savage bigotry#leftists (derogatory)

592 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Medieval skull ring and gold coin hoards discovered in Wales

The macabre jewelry is a unique example of “memento mori” art, which aimed to remind viewers of their mortality.

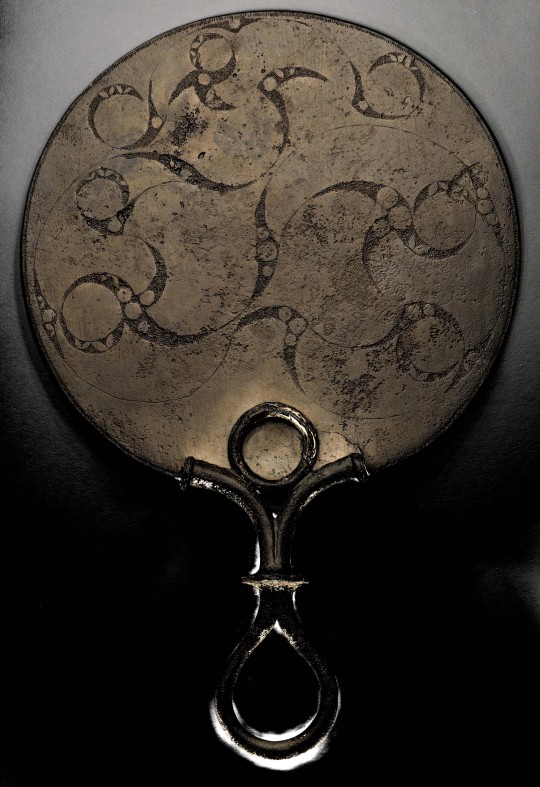

Officials in Wales have designated nine recent archaeological finds—including a hoard of Tudor coins featuring Henry VIII’s portrait and a gold ring inlaid with an enamel skull—as treasure, reports Cathy Owen for Wales Online.

Per a statement, metal detectorists unearthed the artifacts, all of which belonged to elite members of 9th- through 17th-century Welsh society, in Powys and the Vale of Glamorgan. Highlights of the cache range from a ring-shaped medieval silver brooch to a trio of gold coins dated to the reigns of Edward III (1327–1377) and Richard II (1377–1399).

Graeme David Hughes, senior coroner for South Wales Central, declared the discoveries “treasures,” a term that “refers to bonafide, often metal artifacts that meet … specific archaeological criteria” outlined by the United Kingdom’s Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS), notes Laura Geggel for Live Science.

In the U.K., amateur treasure hunters are required to hand their finds over to local authorities. Current guidelines define treasure relatively strictly, but as Caroline Davies reported for the Guardian last December, the U.K. government is working to expand these parameters to better protect the country’s national heritage items. Objects designated as treasure become the property of the state and may be displayed at national or local museums.

A key highlight of the Welsh trove is the golden skull ring, which dates back to the Tudor or early Stuart period. The ring is embossed with the Latin phrase memento mori, which roughly translates to “remember you must die,” according to Tate Britain.

As Menachem Wecker pointed out for Artnet News in 2017, artists throughout history created memento mori–themed paintings, sculptures, drawings and tokens to remind viewers of their own mortality. Though these objects may appear morbid to modern viewers, Artnet notes that they often carried “optimistic, carpe-diem messages” about making the most of one’s time on Earth.

“This is a rare example of a … memento mori ring with a clear Welsh provenance,” says Mark Redknap, deputy head of collections and research at Amgueddfa Cymru—National Museum Wales, in the statement. “Its sentiment reflects the high mortality of the period, the motif and inscription acknowledging the brevity and vanities of life.”

Another notable artifact recently deemed treasure is a posy ring dated to the 17th or 18th century. Per National Jeweler’s Michelle Graff, these items were often engraved with brief poems or sayings alternatively “religious, friendly or amorous in nature.”

The message on the Welsh ring, which is embellished with interlocking symbols and silver gilding, reads, “Be constant to the end,” reports Sarah Pirano for Ancient Origins.

Also of note is a silver, double-hooked fastener dated to the ninth century. The object may have helped its Anglo-Saxon owner hold their garments together or was perhaps worn as a chic piece of jewelry adorned with animal patterns.

“This unusual object is the first ‘Anglo-Saxon style’ double-hooked fastener to be identified in Wales,” says Redknap in the statement. “Reflecting the status of the original owner, it provides new evidence for the exposure of Anglo-Saxon styles within the early Welsh kingdoms, and of the melting-pot of styles and influences from which Welsh identity was to emerge.”

The Y Gaer Museum and the National Museum Wales hope to obtain the cache of objects for their galleries. Officials have yet to announce which institutions will ultimately house the artifacts.

The recently discovered items are just some of the 20 to 45 treasures reported in Wales each year, according to Live Science. Experts have identified more than 550 treasures in the country since 1997, when PAS was established in England and Wales.

By Isis Davis-Marks.

#Medieval skull ring and gold coin hoards discovered in Wales#history#history news#archeology#artifacts#treasure#gold coins#collectables#collectable coins#tudor coins#ancient jewelry#silver

478 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Clashing Storm of Shields - Fighting in the Shield Wall (Part 1: Background)

I think I promised @warsofasoiaf a write up on shield wall combat nearly two years ago now but, after several different versions that each took a slightly different approach, I’ve finally nailed down something that works for me.

As my small introduction has become a rather large post, I’ve decided to split the subject into two sections: a section on the background (introduction, recruitment and organisation, equipment) and a section on how the battle actually took place. I’m posting the first section now, and will post the second in a couple of weeks.

Introduction

I.P. Stephenson once wrote that “the single most defining ideological event in Anglo-Saxon warfare came at Marathon in 490 B.C.”. This comment, and all the assumptions that go with it, highlights the single biggest problem people have in understanding combat in the Early Middle Ages. The uncritical application of Classical scholarship to the medieval world, and a failure to up with the current academic consensus, has significantly distorted how many historians think about shield wall combat.

For example, Gareth William suggests in Weapons of the Viking Warrior that the sax was especially useful in a close order, rim-to-boss formation and compares it to the gladius:

Roman legionaries fighting at close quarters were armed not with a long sword, but with a gladius, or short-sword, which was primarily a thrusting weapon, requiring a minimum of space between the individual soldiers in a line.

The problem with this assumption, leaving aside the fact that weapon sized saxes were rare to the point of non-existence in 9th-11th century Scandinavia and that gladius length saxes weren’t particularly common in Anglo-Saxon England either1, is that the famous Roman short sword wasn’t used for thrusting in a close order formation. Instead, it was used for both cutting and thrusting in open order, with each man taking up 4.5-6 feet of space2. It’s not until open order fighting was abandoned completely and the long spatha was universally adopted by the infantry that we hear of the thrust being the preferred method of combat by the Romans3. An assumption, almost certainly based on scholarship from before 2000, has been made about how the Romans fought and how it might be applied to Anglo-Saxon warfare, but no examination of the different context or more recent scholarship has been performed, leading to the wrong conclusion.

(The Bayeux Tapestry)

Similarly, it’s common in historical fiction set in the Early Middle Ages to feature battles that rely very heavily on Victor Davis Hanson’s The Western Way of War4. For example:

We in the front rank had time to thrust once, then we crouched behind our shields and simply shoved at the enemy line while the men in our second rank fought across our heads. The ring of sword blades and clatter of shield-bosses and clashing of spear-shafts was deafening, but remarkably few men died for it is hard to kill in the crush as two locked shield-walls grind against each other. Instead it you cannot pull it back, there is hardly room to draw a sword, and all the time the enemy’s second rank are raining sword, axe and spear blows on helmets and shield-edges. The worst injuries are caused by men thrusting blades beneath the shields and gradually a barrier of crippled men builds at the front to make the slaughter even more difficult. Only when one side pulls back can the other then kill the crippled enemies stranded at the battle’s tide line.

Bernard Cornwell, The Winter King

Other works, such as Giles Kristian’s Blood Eye and Edward Rutherfurd’s The Princes of Ireland, follow the same pattern of a physical collision between the two formations and a shoving match where weapons are almost secondary. This is a core concept of the traditional model of hoplite combat - the literal othismos (”push”) - that has been likened to a rugby scrum since the early 20th century. Ironically enough, VDH is a great pains to emphasize the unique nature of the Greek phalanx due to the hoplite shield, so even without the doubts of A.D. Fraser, Peter Krentz and all the other “Heretics” it would be questionable to apply this method of warfare to the Early Middle Ages5.

When you examine the differences between the two periods, for example the early Anglo-Saxon shields are often no more than 40cm in diameter and featuring spiked or “sugar loaf” bosses6, it becomes clear that the use of Greek warfare to represent 5th and 6th century warfare is incorrect. Similarly, the difference in construction between the aspis and Scandinavian shields of the 9th and 10th centuries, the aspis having thickly reinforced rims while the Scandinavian shields either taper towards the edges or remain very thin (<10mm), should offer a similar caution7.

In spite of the litany of criticisms I’ve just provided, it’s still necessary to refer back to our understanding of Greek and Roman warfare when examining combat in the Early Middle Ages, for two main reasons. Firstly, and most importantly, the sources are much more detailed about how fighting was carried out and were very often written by men who had themselves fought. While authors of the Early Middle Ages were not necessarily unfamiliar with warfare, they were remarkably uninterested in recording much in the way of details and there’s frequently little useful information to be extracted from accounts of battles.

Secondly, a far larger body of work exists on the how of Ancient hand-to-hand combat. While re-enactors of the medieval period are certainly numerous, perhaps even the most numerous of the pre-modern re-enactor, the sheer output of Greek and Roman re-enactors and the scholars who mine them for insights dwarfs that of medieval re-enactors and, on the whole, is more likely to be up to date with the scholarship of the field in general.

My goal here is to make the best possible use of sources on both Ancient and Medieval warfare in order to present a picture that is as close to a plausible reconstruction as I can manage. I don’t mean for this to be authoritative, and my views do in some cases differ from those of some re-enactors or academics, but I do hope you find this post a useful resource in your writing.

(This? This is what not to do.)

Trees of the Spear-Assembly: Who Were the Warriors?

One of the most important things in understanding combat in the Early Middle Ages is knowing who was doing the fighting and why, since this has a big impact on the way in which they fight, and with how much enthusiasm. In particular, the question of whether they were just poor farmers levied en masse or wealthier members of society who had both military obligations and the culture of carrying them out is an important one, as quite often this is used to demonstrate the difference between two sides.

The answer to the question is that, by and large, men who fought were freemen of some standing, if not always considerable landowners, and wealthy by the standards of their people. I emphasize the concept of relative wealth for good reason, and I’ll get into that as we have a look at the basic structure of the “armies” of the period.

Generally speaking, armies of the Early Middle Ages, across almost all of Europe, consisted of two elements: the Household (hirð, hird, comitatus, etc) and the Levy (fyrd, lið, exercitus, etc). I use “levy” here as a shorthand for any force composed of freemen who are not regularly attached to the household of a major landholder, as they were not usually assembled into a single coherent force with 100% unified command, but I do want to note that there would be a significant difference in the unity of an army made up of regional levies and one made up of lið (individual warbands)8.

The status of those serving in the household of a powerful landholder could vary significantly, from slaves to the sons of major landholders (although militarised slaves, it must be admitted, were rare outside of the Visigothic realm), and the more powerful the landowner the more likely the men of his household would be themselves descended from someone of considerable status. A significant portion could still be made up of poorer freemen who were sons of older warriors or whose family had some close connection to the major landowner.

For someone who maintained a large household, it was important that they present an image of being a wealthy as possible, and the best way to do this was to outfit the men of their household with every piece of military equipment that displayed status. So, whether he was descended from slaves or was the son of a family who owned a thousand acres, once a man had sworn their oath of loyalty to their new patron, they could be expect to be equipped with all the trappings of a warrior. This might only be symbolic in poorer regions (a fancier sword, a specific type of ornament, etc), especially if the landowner already had a number of armoured retainers, but it bound the different levels of freemen together into a single group.

Generally this oath swearing would occur after a youth had spent several years in the household of their future patron, where they would learn all the necessary skills of a warrior, such as riding, hunting, shooting a bow, using a sword and fighting with spear and shield. These youths probably participated in battles as auxiliaries with bows and javelins and only joined the ranks of the shield wall when they were considered full warriors, but we have only have very limited information on this point.

The status of men of the levy or warband varied to a much smaller degree. They were, in almost all cases, free and relatively wealthy by the standards of their region, although you do see a bit more of a variation in warbands, which might have members from a half dozen regions and many more backgrounds. In comparison, any army raised in defence of a region or raised from a region is going to consist entirely of free men and the majority of these will be fairly wealthy.

Simply put, even basic military equipment was sufficiently expensive that farmers who merely had enough land to sustain their family9 weren’t going to be able to afford much more than an axe, shield and spear or, depending on their region, a bow and 12-24 arrows. This is consistent across the Carolingian, Lombard and Scandinavian world during the 8th-11th centuries and, given the mostly aristocratic nature of warfare in Anglo-Saxon England, was likely true there as well10.

Basic military equipment, however, was not what rulers looked for when summoning forces for external wars or internal defence. We know from the capitularies of Charlemagne that only a man with four estates was required to arm and equip himself for service and that, with one exception, only men with one estate or more were required to pitch in to help equip one of their number for service11. Moreover, these estates weren’t even all the land the freeman held, just the lands he held which had unfree tenants, so that a “poor” freeman who merely had his own personal land was excluded from military service12.

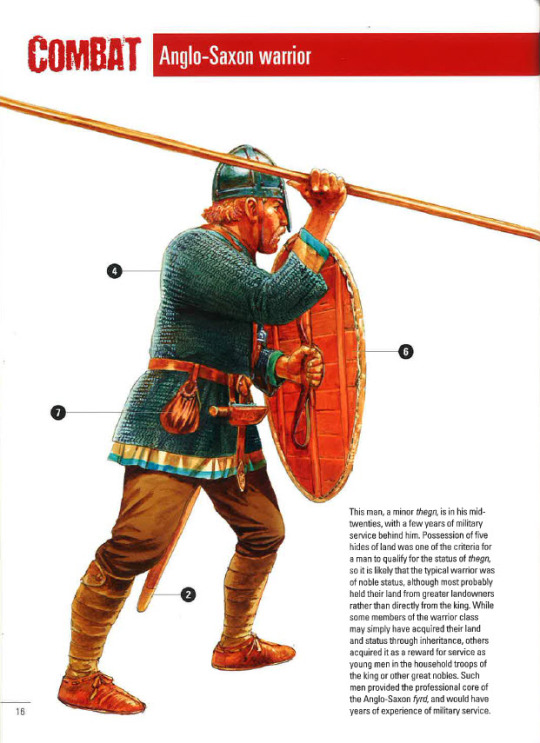

(The average Anglo-Saxon fighting man)

Much the same situation appears in mid-8th century Lombardy, where king Aistulf demanded that those who had 7 or more properties worked by unfree tenants should perform service with a horse and full equipment, while those with less than this, but who own more than 25 acres (40 iugera) of their own, were required to perform an unarmoured cavalry service. 25 acres is about half the land later Anglo-Norman evidence suggests is the minimum for unarmoured cavalry service, so possibly this was an attempt on Aistulf’s part to enfranchise the lesser freemen and get them to support his usurpation of the crown at the political assembly13. Note, however, that the minimum level for cavalry service is nearly double what a peasant family would need to subsist off and implies a man of moderate wealth in and of itself14.

England is somewhat different, as we lack any specific requirements for those being summoned to military service, but from at least 806 we can surmise that 1 man from every 5 hides of land was required for the army. By this point a “hide” wasn’t a measure of area but of value, approximately £1, in a time when 1d. was the wage of a skilled labourer15.

The implications of this aren’t immediately obvious, but when you consider that Wessex had a population of perhaps 450 000 people, across an area of 27 000 taxable hides, only 5400 men (1 man from every 20 families) were actually required for military service16. Many of these, perhaps even most, would have belonged in the retinues of major landholders as either part of their household or as landed warriors owing service to the landholder in exchange for their land. In the same vein, the one man from every hide who was required to maintain bridges and fortifications, as well as defend the burhs (not serve in the field!), was drawn on the basis of something like 1 man for every 4 families. These are heavy responsibilities, but still far from men with sickles and pitchforks making up the fyrd.

There are some exceptions, or else cases where the evidence is thin enough that it’s difficult to say one way or the other, and these typically occur in areas that a less densely populated and less wealthy. The kingdom of Dal Riada in the seventh century, for instance, raised about 3 men from every 2 households for naval duties, although it might also have called out fewer warriors from the general population of the most powerful clan for land warfare17.

(A replica of the Gokstad ship)

Scandinavia is somewhat trickier, since a lot of the sources are late and from a period where central authority existed. We know from archaeological evidence that, in Norway, large scale inland recruitment of men for naval expeditions had been occurring since the Migration Era, as the number of boathouses exceeds the best estimates of local populations18. These were initially clustered around important political and economic centers, but spread out more evenly across Norway during the middle ages as a central political authority arose. This system is likely at least one part of the origin for the leidang system of levying ships, which seems to have properly formed in Norway and Denmark during the late 10th or early 11th century as a result of royal power becoming strong enough to call out local levies across the whole kingdom19.

It seems likely, based on later law codes and other contemporary societies, that Scandinavian raiders during the 8th and 9th centuries were mostly the hird of a wealthy landowner (or their son), supplemented with sons of better off farmers from nearby holdings. Ships were comparatively small at this point, just 26-40 oars (approximately 30-44 men)20, and most had 24-32 oars per ship. This corresponds fairly well with what a prominent landholder might be able to raise from his own household, with additional crews coming from the sons of nearby farmers, although whether this was voluntary, coerced or some combination of the two is impossible to say21.

However, these farmers’ sons, while unlikely to wear mail in the majority of cases, should not be thought of as poor. The vast majority of farmers in 8th-10th century Scandinavia would have had one or two slaves and sufficient land to not only keep their slaves fed and employed, but also to potentially raise more children than later generations22. These farmers’ sons might have been “poor” by the standards of the men they faced in richer areas of the world, but they were rather well off by the standards of their society.

Later, after the end of the 10th century, the leidang was largely controlled by the king of the Scandinavian country and, particularly in the populous and relatively wealthy Denmark, poorer farmers were increasingly sidelined from any obligation to provide military service. Ships also rose in size from the end of the 9th/start of the 10th century, regularly reaching 60 oars for vessels belonging to kings or powerful lords, and even the “average” size seems to have gone from 24-32 oars to 40-50 oars23.

Slaughter Reeds and Flesh Bark: Arms and Armour of the Warrior

The equipment of the warrior consisted of, at its most basic level, a spear and a shield. For those who belonged to a poorer region, a single handed wood axe might serve as a sidearm, or perhaps even just a dagger, while in wealthier regions the sidearm would generally be a sword or a specialised fighting axe24. In an interesting twist, both the poorest and the wealthiest members of society were almost equally likely to use a bow, although I expect that the poorer men mostly used hunting bows, while the professional fighting men used heavier warbows25.

Spearheads, at least from the 7th-11th centuries, were relatively long (blades of >25cm) and heavy (>200g), but most were well tapered for penetrating armour. Some, especially the longest examples, weighed around a pound, but were probably still considered one handed weapons26. Others, however, weighed in excess of two pounds and must have been two handed weapons, possibly the “hewing spear” mentioned in some 13th century sagas27. Javelins, too, appear to have tended to feature long, narrow blades that would have made them a short range weapon, while also providing considerable penetration within their ~40 meter range.

Swords, for their part, were not quite the heavy hacking implement once attributed to them, but also aren’t quite as well balanced as later medieval swords would be. Early swords, before the 9th century, tended to be balanced about halfway down the blade, which might make for a more powerful cut, but didn’t do much for rapid recovery or shifting the blade between covers. However, from the mid-9th century, the balance shifted back towards the hilt, which made them much faster and more maneuverable28. This may indicate a shift towards a looser form of combat, where sword play was more common, or it might indicate nothing more than a stylistic choice. After all, the Celts of the 2nd-1st century BC preferred long, heavy, poorly balanced swords for fighting in spite of relying on the usual Mediterranean “open” style of combat29.

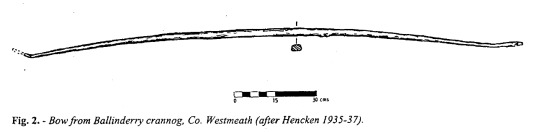

(The Ballinderry Bow)

Warbows, with a couple of exceptions, appear to have been short but powerful. Starting with the Illerup Adal bows, which most likely only had a draw length of 26-27″, we see a repeated pattern when very powerful bows are also much shorter than we expect them to be. In particular, the heavier of the two bows from Illerup Adal is very similar to the Wassenaar Bow, a 9th-10th century bow. A replica of the latter drew 106lbs @ 26″, making it quite a powerful bow, and similar bows have been found at Nydam, Leeuwarden-Heechterp and Aaslum. Only the Ballinderry and Hedeby bows break this trend, with both capable of being drawn to 28″-30″. In all cases, draw weights varied between 80lbs and 150lbs, although 80-100lbs is by far the most common30. The consequence of this is that the power of the bows is not going to be as high as later medieval bows, which were able to be drawn to 30″ and, as the arrows were also relatively light, suggests an energy of 40-60j under most circumstances. This is enough to penetrate mail at close range if using a bodkin arrowhead, but at longer ranges mail would have offered quite excellent protection.

When it comes to shields, there was evidently quite a bit of variation. Early Anglo-Saxon and Merovingian shields were quite small and light, about 40-50cm in diameter31, but later shields were generally 80-90cm in diameter. In particular, we have good evidence of viking shields generally fitting this description, although it’s less clear whether or not later Carolingian and Anglo-Saxon shields retained this diameter or reduced to 50-70cm in diameter (see f.n. 7). In all cases, however, the shield was fairly thin at the center, less than 10mm, and could be as low as 4mm thick at the edge. While thin leather or rawhide could be applied to the front and back of the shield to reinforce it, it’s equally possible that only linen was used to reinforce the shield, or even that the shields were without any reinforcement32.

Recent tests by Rolf F. Warming have shown that this style of shield is rapidly damaged by heavy attacks if used in a passive manner (as in a static shield wall) and that the shield is best used to aggressively defend yourself33. While the test was not entirely accurate to combat in a shield wall (more on this in the second part), it does highlight the relative fragility of early medieval shields compared to other, more heavily constructed shields like the Roman scutum in the Republican and early Empire or the Greek aspis. As I’ve said before, this means we have to rethink how early medieval warfare worked.

Finally, we come to the topic of armour. The dominant form of armour was the mail hauberk - usually resembling a T-shirt in form - and other forms of metal armour were far less common. Guy Halsall has suggested that poorer Merovingian and Carolingian warriors might have used lamellar armour34, and there is some evidence from cemeteries and artwork that Merovingian and Lombard warriors wore lamellar armour in the 6th and 7th centuries, but there’s little evidence to support lamellar beyond this. While it does crop up in Scandinavia twice during the 10th/11th centuries, it was almost certainly an uncommon armour that was used either by Khazar mercenaries or by prominent men who were using it as a status symbol35. Scale armour is right out, Timothy Dawson’s arguments aside, as there is no good evidence of it.

(Helmet from Valsgarde 8)

Helmets evolved throughout the Early Middle Ages, ultimately deriving from late Roman helmets that featured cheek flaps and aventails. During the 6th and 7th centuries, especially in Anglo-Saxon England and Scandinavia, masks were attached to the helmets, either for the whole face or just the eyes. The masks did not long survive the 7th century in Anglo-Saxon England, but the Gjermundbu helmet may suggest it lasted in Scandinavia through to the 10th century. Merovingian helmets of the 6th-8th century tend to be more conical and keep the cheek flaps, but do not have any mask36. Carolingian helmets of the 9th century appear to have been a unique style, more rounded but also coming down further towards the cheeks, and it’s hard to say if this eventually developed in the conical helmet of the late 10th/early 11th century or if it was just a dead end37. Regardless, by the 11th century the conical helmet was the most common form of helmet in England as well as the Continent.

And now for the controversial stuff: non-metallic armour. In short, I don’t think that textile armour was very common during the Early Middle Ages, nor do I think that hardened leather was very common either. The evidence from the High Middle Ages suggests that, unless someone who couldn’t afford to own mail was legally required to own textile armour, they generally didn’t, and we have plenty of quite reliable depictions of infantry serving without any form of body armour38. The shields in use were as much armour as most unarmoured men needed - since, as you’ll recall from the previous section, they rarely fought - and they covered a lot of the body. So far as I’m concerned, there wasn’t a need for it, and plenty of societies through history have fought in close combat without more armour than their shield.

Summing Up

This has been a very basic overview of the background to warfare in the Early Middle Ages, and I know I haven’t covered everything. Hopefully, however, I’ve provided enough background for people to follow along when I dig down into the actual experience of battle in my next post. I’ll cover the basics of scouting, choosing a site to give battle, the religious side of things and then, at long last, the grim face of battle for those standing in the shieldwall.

If you’d like to read more about society and warfare in the Early Middle Ages, then I’d recommend Guy Halsall’s Warfare and Society in the Barbarian Westand Philip Line's The Vikings and their Enemies: Warfare in Northern Europe, 750-1100, which together cover most of Western and Northern Europe from 400 AD to 1100 AD. While I have some disagreements with both authors, their works have shaped my thoughts over the years since I first acquired them. For the Vikings specifically, Kim Hjardar and Vegard Vike's Vikings at War is excellent, as much for the coverage of campaigns across the world as for the information on weapons and warfare.

Until next time!

- Hergrim

Notes

1 For the rarity of the sax in the viking world, see Vikings at War, by Kim Hjardar and Vegard Vike. For the Anglo-Saxon sax, see the list of finds here. Just 5 out of 33 (15%) had blades 44cm or more and, if you remove those longer than the Pompeii style of gladius (which is the point where some think the Romans changed to purely thrusting style), just two fit the bill.

2 Michael J. Taylor’s “Visual Evidence for Roman Infantry Tactics” is by far the best recent examination of Roman fighting styles, but Polybius has been translated in English for ages. See, however, M.C. Bishop, The Gladius, for an argument that the Romans changed to close order and preferred to rely on thrusting by the end of the 1st century AD.

3 See J. C. Coulston and M.C. Bishop, Roman Military Equipment: From the Punic Wars to the Fall of Rome, for the infantry adoption of the gladius. Any general history of the Roman military will cover the transition from open order to close order during the 3rd century AD.

4 Those of you with a copy of Victor Davis Hanson's The Western Way of War need to perform a quick exorcism. You must burn the book at midnight during the full moon and then divide the ashes into four separate containers, one of gold, one of silver, one of bronze and one of iron. You should then bury ashes from the iron container at a crossroads, scatter the ashes in the bronze container to the wind in four directions, pour the ashes from the silver container into a fast flowing river, and finally feed the ashes from the gold container to a cat, a bat and a rat.

5 A.D. Fraser “The Myth of the Phalanx-Scrimmage” is one of the earliest attacks on the idea of literal othismos. The debate reignited in the 1980s, with Peter Krentz’s “The Nature of Hoplite Battle” leading the charge of the heretics, and the conceptual othismos model is now the accepted version. Hans van Wees’ Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities is probably the best revisionist work to start with. Matthew A. Sears, as attractive as he looks, should be avoided.

6 Early Anglo-Saxon Shields by Tania Dickinson and Heinrich Harke

7 Duncan B. Campbell’s Spartan Warrior 735–331 BC has the most easily accessible information on the best preserved aspis, which is ~10mm thick at the center and 12-18mm thick at the edge, but there’s also a good cross section in Nicholas Sekunda’s Greek Hoplite 480-323 BC. For Viking shields, see this page of archaeological examples by Peter Beatson. Note the similarity to oval shields from Dura Europos in thickness and tapering (Roman Shields by Hilary and John Travis). It’s also worth considering that Carolingian and Anglo-Saxon manuscript miniatures tend to show shields that rarely cover more than should to groin, implying a typical diameter of 50-70cm.

8 See Niels Lund’s “The armies of Swein Forkbeard and Cnut: "leding or lið?”” and Ben Raffield’s “Bands of brothers: a re‐appraisal of the Viking Great Army and its implications for the Scandinavian colonization of England” for an examination of how the lið was constructed, and see Richard Abels’ ‘Alfred the Great, the Micel Hæðn Here and the Viking Threat’, in T. Reuter (ed.), Alfred the Great. Papers from the Eleventh-Centenary Conference for a discussion on the nature of viking “armies”

9 10-15 acres depending on crop rotation and how close to subsistence level you want to peg this category

10 The Scandinavian Gulathing and Frostathing laws were only composed in the late 11th/early 12th century, but it has been argued that they were essentially a codification of earlier oral laws. At least with regards to equipment and service, I see no reason to doubt this.

11 Almost all of the relevant capitularies are translated in Hans Delbruck’s History of the Art of War: The Middle Ages, with the original Latin in an appendix.