Text

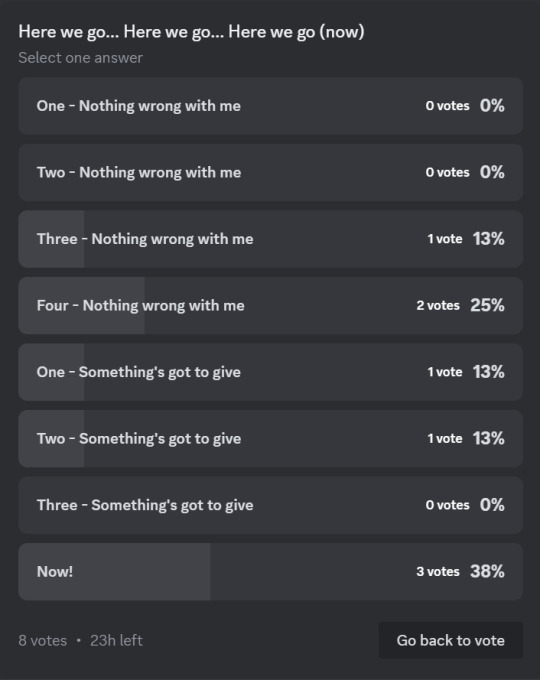

oh, you're a gamer? name 5 games. I'll wait.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think one of the things that people often forget (or don't even know) when discussing the quirks of the English language is its really strange history.

Great Britain, Ireland, and everything in that general area used to be a bunch of random islands that no one except the people living there cared about. They didn't speak English back then. Instead, they spoke something called Brythonnic or Brittonic, which was named in reference to the ancient Britons. Then, the Romans decided that they wanted to conquer a sizeable chunk of the known world for a lark and set up fortifications on those "random islands that no one except the people living there cared about." Notably, that also wasn't the advent of the English language because English is a Germanic language, not a Romance language or a Brittonic language.

For that, we need to look to the 5th century CE, when a bunch of guys called the Anglo-Saxons (named Anglo because they were ancient English people, and Saxon because of their swords) showed up. They spoke Old English. The real Old English, not the Middle English of Shakespeare that everyone mistakenly calls Old English. The Roman Empire was on its last legs at that point, but it still had a pretty outsized impact on the development of the English Language.

See, the Anglo-Saxons wrote their language with a system called the runic Futhorc, named so for its first six runes; ᚠ - Feoh, ᚢ - Ur, ᚦ - Thorn, ᚩ - Os, ᚱ - Rad, and ᚳ - Cen. This was a perfectly serviceable way to write Old English, and people did so for centuries. However, the cultural power of Latin and its alphabet was far more than that of the Futhorc or its sister system, Younger Futhark (the Younger Futhark having been used in Scandinavian areas). This means that many of the Old English manuscripts were written with a system completely unsuited to English as a language. Latin G had to pull double duty for ᚷ - Geofu (modern G) and ᛄ - Gear (modern Y) as Y was only considered a vowel at that point, and J (used in many non-English languages for the sound of the modern English Y) didn't exist yet. W, not a sound found in Latin, had to either be transcribed with uu/vv (as U and V were once interchangeable; hence the name Double-U) or with ƿ - Wynn, the latter of which was based on the rune ᚹ - Wyn. The two sounds that are today represented by th also had to have new letters made for them; spawning þ - Thorn from the rune of the same name and ð - Eth (pronounced with the th in that).

Now, about two paragraphs ago, I mentioned Middle English, and how it's a different thing from Old English. How exactly did Old English become Middle English? Was it a long slow process, where slow linguistic shift resulted in a--okay, yeah, you got me. It's not that. It was the French. The Duke of Normandy/William the Conqueror, to be specific, who decided that he wanted to conquer Britain and succeeded. To be clear, there was already some influence from continental Europe and Scandinavia--like with Alcuin of York living it up in the court of Charlemagne in the 8th century and the Danes kinda invading England slightly before the Norman Conquest--but never anything as substantial as The Conquest.

And this isn't even mentioning the fact that there's about seven or eight centuries between the Norman Conquest and the rise of very early examples of what could be recognized as "Modern English"; or the advent of the printing press and how continental European printers didn't have þ in their typesets, leading to its eventual falling out of use in English; or some of the other impacts of Latin on English; or numerous other things that contributed to why English is Like That. I've mostly talked about all this because there's one thing in particular that I want to clear up. People often like to joke that English goes around mugging other languages for spare grammar, but it's a whole lot closer to "other languages used to go around beating up English and then shoving spare grammar into its pockets for shits and giggles."

0 notes

Text

it will never not be funny to me to read about a group ancient people, see them described as barbarians or something, have an image of a ripped, shirtless man dressed in animal skins pop into your head because that's what the general depiction of them is in media, then look up what historians say they probably looked like and the picture is just like. A Guy.

anyway for completely unrelated reasons look at these illustrations of what historian Kim Hjardar and archaeologist Vegard Vike say vikings from different times and places probably looked like

0 notes

Text

Excerpt from Neil Sheridan's Demonology (4th Edition) - Part 1

(A piece of fiction by Fungustober, written in a style reminiscent of scientific books.)

7. The Life-Cycle of a Demon

As you may have discovered over the previous chapters of this book, demons are a strange type of being. They do not fit under any classification biologists currently have.¹ “Demon” seems to be the only sort of name that can be applied to them at all. One of the many reasons for this confusion is due to their life cycle. It is not quite mammalian, not quite avian, and not quite insectile; both a mixture of and completely different from all three. Indeed, there is much we do not know about this subject. Information is sparse, and many works from demonologists avoid mentioning it altogether. This chapter seeks to compile as much information on the life cycle as possible, so that others may build upon it and further advance the field of study.

The beginning of a demon’s life cycle starts, like a bird or an insect, with an egg. It is unknown how many eggs are laid as part of a demon’s brood (as any researchers that have attempted to find out have met a swift end²), but it has been found that the eggs must be incubated in the fires of a furnace to hatch. It is believed by some that this is the reason for their ash-gray skin, though any link has yet to be proven.�� Interestingly, demon eggs do not have to be incubated immediately, as they have the ability to lay dormant for decades. One popular account even tells of picking through the ruins of a burned-down mansion to find survivors, only to discover demons who hatched in the fires that raged there. However, while it may have been inspired by real instances of such an event happening, the account itself is widely considered dubious at best.⁴

0 notes

Text

"the average life expectancy of the average medieval peasant was 35" is actually statistical error. Babies georg, who was dying at 0 years old every few minutes--

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

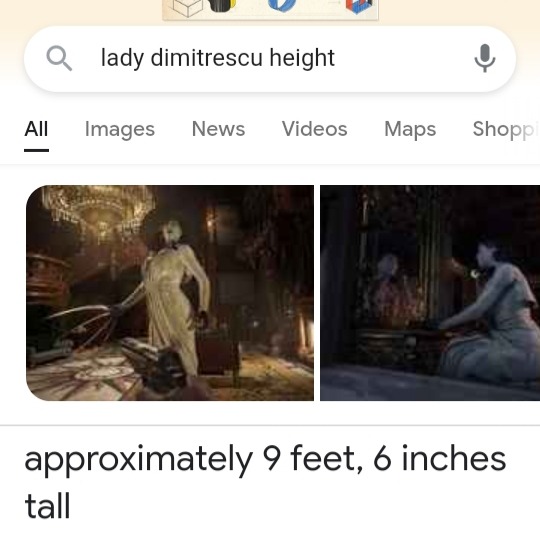

Wanted to do this^ for a character concept I've been cooking up, so at 4 in the morning I decided to actually get it done.

I think it turned out well.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

very important note I wrote for myself in my lore document

0 notes

Text

A waiter walks over to his boss and says "Hey, an ice floe just came in and left 5 dollars behind." The boss chuckles. "Oh, don't worry," he responds. "That was just the tip of the iceberg"

1 note

·

View note

Text

incredibly important update:

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

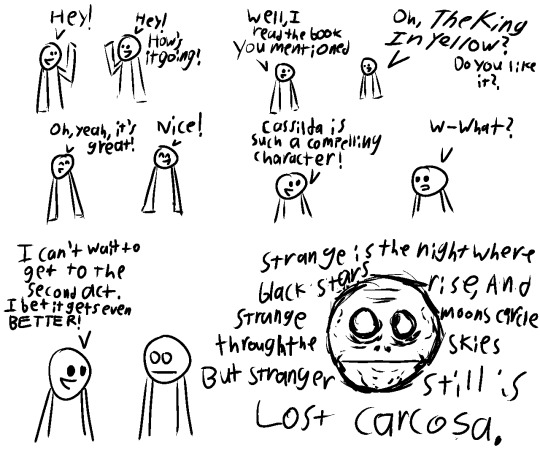

I've been reading The King In Yellow, and I felt compelled to make this. [The words, in case you can't read my handwriting:] [1: Hey!] [2: Hey! How's it going?] [1: Well, I read the book you mentioned.] [2: Oh, The King In Yellow? Do you like it?] [1: Oh, yeah, it's great!] [2: Nice!] [1: Cassilda is such a compelling character!] [2: W-what?] [1: I can't wait to get to the second act. I bet it gets even BETTER!] [Strange is the night where black stars rise,] [And strange moons circle through the skies] [But stranger still is] [Lost Carcosa.]

2 notes

·

View notes