#the Great Arab Revolt

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Бег созвездий. Мороз. Светящимся мелом Обведенные выси. Мерзлой грязи кайма. Пар над тощей верблюдицей, галоп оголтелый, Иа-Оренс. Аравия. Полночь. Зима.

Узкий шорох полыни. Холмов вереницы. Сон в седле. Почернелых сугробов разбег. И с разлета верблюдица мордой ложится, Зарывая наездника по уши в снег.

Он встает и верблюдицу тянет. Над ними Одиночество ночи. Стальная луна. Шесть мешков до отказа полны золотыми В кровь изранены ноги. Пустыня. Война.

Одиночество! Что перед ним непогоды? В неизвестной стране, в неизвестном году Как во сне видит крепость, бойницы и своды, Босиком он идет по звенящему льду."

Н.Тихонов "Лоуренс Аравийский" 1935-1936

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

World War I. Arab Revolt of 1916-1918. Dhari ibn Tawala of the Aslam Shammar and his Tribesmen on Horseback.

#wwi#arab revolt#middle est#ww1#arab#first world war#world war 1#world war one#world war i#world war#the great war#horse#war history#photography#tumbler#world#war#1#the#great#desert#arab history#history

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

17/12/23 this masterlist has been completely revamped with free access to all material. It will be updated and edited periodically so please click on my username and reblog the current version directly from me if you're able.

14/8/24 reboosting this post with How to Help Palestine updated. Please scroll to the bottom to donate or boost the links.

Palestine: The Big Damn List

(Yes, it's a lot. Just choose your preferred medium and then pick ONE.)

Podcasts

Backgrounders and Quick Facts

Interactive Maps

Teach-Out Resources

Reading Material (free)

Films and Documentaries (free)

Non-Governmental Organizations

Social Media

How You Can Help <- URGENT!!!

Podcasts

Cocktails & Capitalism: The Story of Palestine Part 1, Part 3

It Could Happen Here: The Cheapest Land is Bought with Blood, Part 2, The Balfour Declaration

Citations Needed: Media narratives and consent manufacturing around Israel-Palestine and the Gaza Siege

The Deprogram: Free Palestine, ft. decolonizatepalestine.com.

Backgrounders and Quick Facts

The Palestine Academy: Palestine 101

Institute for Middle East Understanding: Explainers and Quick Facts

Interactive Maps

Visualizing Palestine

Teach-Out Resources

1) Cambridge UCU and Pal Society

Palestine 101

Intro to Palestine Film + Art + Literature

Resources for Organising and Facilitating)

2) The Jadaliya YouTube Channel of the Arab Studies Institute

Gaza in Context Teach-in series

War on Palestine podcast

Updates and Discussions of news with co-editors Noura Erakat and Mouin Rabbani.

3) The Palestine Directory

History (virtual tours, digital archives, The Palestine Oral History Project, Documenting Palestine, Queering Palestine)

Cultural History (Palestine Open Maps, Overdue Books Zine, Palestine Poster Project)

Contemporary Voices in the Arts

Get Involved: NGOs and campaigns to help and support.

3) PalQuest Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question.

4) The Palestine Remix by Al Jazeera

Books and Articles

Free reading material

My Gdrive of Palestine/Decolonization Literature (nearly all the books recommended below + books from other recommended lists)

Five free eBooks by Verso

Three Free eBooks on Palestine by Haymarket

LGBT Activist Scott Long's Google Drive of Palestine Freedom Struggle Resources

Recommended Reading List

Academic Books

Edward Said (1979) The Question of Palestine, Random House

Ilan Pappé (2002)(ed) The Israel/Palestine Question, Routledge

Ilan Pappé (2006) The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, OneWorld Publications

Ilan Pappé (2011) The Forgotten Palestinians: A History of the Palestinians in Israel, Yale University Press

Ilan Pappé (2015) The Idea of Israel: A History of Power and Knowledge, Verso Books

Ilan Pappé (2017) The Biggest Prison On Earth: A History Of The Occupied Territories, OneWorld Publications

Ilan Pappé (2022) A History of Modern Palestine, Cambridge University Press

Rosemary Sayigh (2007) The Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries, Bloomsbury

Andrew Ross (2019) Stone Men: the Palestinians who Built Israel, Verso Books

Rashid Khalidi (2020) The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance 1917–2017

Ariella Azoulay (2011) From Palestine to Israel: A Photographic Record of Destruction and State Formation, 1947-1950, Pluto Press

Ariella Azoulay and Adi Ophir (2012) The One-State Condition: Occupation and Democracy in Israel/Palestine, Stanford University Press.

Jeff Halper (2010) An Israeli in Palestine: Resisting Dispossession, Redeeming Israel, Pluto Press

Jeff Halper (2015) War Against the People: Israel, the Palestinians and Global Pacification

Jeff Halper (2021) Decolonizing Israel, Liberating Palestine: Zionism, Settler Colonialism, and the Case for One Democratic State, Pluto Press

Anthony Loewenstein (2023) The Palestine Laboratory: How Israel exports the Technology of Occupation around the World

Noura Erakat (2019) Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine, Stanford University Press

Neve Gordon (2008) Israel’s Occupation, University of California Press

Joseph Massad (2006) The Persistence of the Palestinian Question: Essays on Zionism and the Palestinians, Routledge

Memoirs

Edward Said (1986) After the Last Sky: Palestine Lives, Columbia University PEdward Saidress

Edward Said (2000) Out of Place; A Memoir, First Vintage Books

Mourid Barghouti (2005) I saw Ramallah, Bloomsbury

Hatim Kanaaneh (2008) A Doctor in Galilee: The Life and Struggle of a Palestinian in Israel, Pluto Press

Raja Shehadeh (2008) Palestinian Walks: Into a Vanishing Landscape, Profile Books

Ghada Karmi (2009) In Search of Fatima: A Palestinian Story, Verso Books

Vittorio Arrigoni (2010) Gaza Stay Human, Kube Publishing

Ramzy Baroud (2010) My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza's Untold Story, Pluto Press

Izzeldin Abuelaish (2011) I Shall Not Hate: A Gaza Doctor’s Journey on the Road to Peace and Human Dignity, Bloomsbury

Atef Abu Saif (2015) The Drone Eats with Me: A Gaza Diary, Beacon Press

Anthologies

Voices from Gaza - Insaniyyat (The Society of Palestinian Anthropologists)

Letters From Gaza • Protean Magazine

Salma Khadra Jayyusi (1992) Anthology of Modern Palestinian Literature, Columbia University Press

ASHTAR Theatre (2010) The Gaza Monologues

Refaat Alreer (ed) (2014) Gaza Writes Back, Just World Books

Refaat Alreer, Laila El-Haddad (eds) (2015) Gaza Unsilenced, Just World Books

Cate Malek and Mateo Hoke (eds)(2015) Palestine Speaks: Narrative of Life under Occupation, Verso Books

Jehad Abusalim, Jennifer Bing (eds) (2022) Light in Gaza: Writings Born of Fire, Haymarket Books

Short Story Collections

Ghassan Kanafani, Hilary Kilpatrick (trans) (1968) Men in the Sun and Other Palestinian Stories, Lynne Rienner Publishers

Ghassan Kanafani, Barbara Harlow, Karen E. Riley (trans) (2000) Palestine’s Children: Returning to Haifa and Other Stories, Lynne Rienner Publishers

Atef Abu Saif (2014) The Book of Gaza: A City in Short Fiction, Comma Press

Samira Azzam, Ranya Abdelrahman (trans) (2022) Out Of Time: The Collected Short Stories of Samira Azzam

Sonia Sulaiman (2023) Muneera and the Moon; Stories Inspired by Palestinian Folklore

Essay Collections

Edward W. Said (2000) Reflections on Exile and Other Essays, Harvard University Press

Salim Tamari (2008) Mountain against the Sea: Essays on Palestinian Society and Culture, University of California Press

Fatma Kassem (2011) Palestinian Women: Narratives, histories and gendered memory, Bloombsbury

Ramzy Baroud (2019) These Chains Will Be Broken: Palestinian Stories of Struggle and Defiance in Israeli Prisons, Clarity Press

Novels

Sahar Khalifeh (1976) Wild Thorns, Saqi Books

Liyana Badr (1993) A Balcony over the Fakihani, Interlink Books

Hala Alyan (2017) Salt Houses, Harper Books

Susan Abulhawa (2011) Mornings in Jenin, Bloomsbury

Susan Abulhawa (2020) Against the Loveless World, Bloomsbury

Graphic novels

Joe Sacco (2001) Palestine

Joe Sacco (2010) Footnotes in Gaza

Naji al-Ali (2009) A Child in Palestine, Verso Books

Mohammad Sabaaneh (2021) Power Born of Dreams: My Story is Palestine, Street Noise Book*

Poetry

Fady Joudah (2008) The Earth in the Attic, Sheridan Books,

Ghassan Zaqtan, Fady Joudah (trans) (2012) Like a Straw Bird It Follows Me and Other Poems, Yale University Press

Hala Alyan (2013) Atrium: Poems, Three Rooms Press*

Mohammed El-Kurd (2021) Rifqa, Haymarket Books

Mosab Abu Toha (2022) Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems from Gaza, City Lights Publishers

Tawfiq Zayyad (2023) We Are Here to Stay, Smokestack Books*

The Works of Mahmoud Darwish

Poems

Rafeef Ziadah (2011) We Teach Life, Sir

Nasser Rabah (2022) In the Endless War

Refaat Alareer (2011) If I Must Die

Hiba Abu Nada (2023) I Grant You Refuge/ Not Just Passing

[All books except the ones starred are available in my gdrive. I'm adding more each day. But please try and buy whatever you're able or borrow from the library. Most should be available in the discounted Free Palestine Reading List by Pluto Press, Verso and Haymarket Books.]

Human Rights Reports & Documents

Information on current International Court of Justice case on ‘Legal Consequences arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem’

UN Commission of Inquiry Report 2022

UN Special Rapporteur Report on Apartheid 2022

Amnesty International Report on Apartheid 2022

Human Rights Watch Report on Apartheid 2021

Report of the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict’ 2009 (‘The Goldstone Report’)

Advisory Opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, International Court of Justice, 9 July 2004

Films

Documentaries

Jenin, Jenin (2003) dir. Mohammed Bakri

Massacre (2005) dir. Monica Borgmann, Lokman Slim, Hermann Theissen

Slingshot HipHop (2008) dir. Jackie Reem Salloum

Waltz with Bashir (2008) dir. Ari Folman † (also on Amazon Prime)

Tears of Gaza (2010) dir. Vibeke Løkkeberg (also on Amazon Prime)

5 Broken Cameras (2011) dir. Emad Burnat (also on Amazon Prime)

The Gatekeepers (2012) dir. Dror Moreh (also on Amazon Prime)

The Great Book Robbery (2012) | Al Jazeera English

Al Nakba (2013) | Al Jazeera (5-episode docu-series)

The Village Under the Forest (2013) dir. Mark J. Kaplan

Where Should The Birds Fly (2013) dir. Fida Qishta

Naila and the Uprising (2017) (also on Amazon Prime)

GAZA (2019) dir. Andrew McConnell and Garry Keane

Gaza Fights For Freedom (2019) dir. Abby Martin

Little Palestine: Diary Of A Siege (2021) dir. Abdallah Al Khatib

Palestine 1920: The Other Side of the Palestinian Story (2021) | Al Jazeera World Documentary

Gaza Fights Back (2021) | MintPress News Original Documentary | dir. Dan Cohen

Innocence (2022) dir. Guy Davidi

Short Films

Fatenah (2009) dir. Ahmad Habash

Gaza-London (2009) dir. Dina Hamdan

Condom Lead (2013) dir. Tarzan Nasser, Arab Nasser

OBAIDA (2019) | Defence for Children Palestine

Theatrical Films

Divine Intervention (2002) | dir. Elia Suleiman (also on Netflix)

Paradise Now (2005) dir Hany Abu-Assad (also on Amazon Prime)

Lemon Tree (2008) (choose auto translate for English subs) (also on Amazon Prime)

It Must Be Heaven (2009) | dir. Elia Suleiman †

The Promise (2010) mini-series dir. Peter Kosminsky (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4)

Habibi (2011)* dir. Susan Youssef

Omar (2013)* dir. Hany Abu-Assad †

3000 Nights (2015)* dir. Mai Masri

Foxtrot (2017) dir. Samuel Maoz (also on Amazon Prime)

The Time that Remains (2019) dir. Elia Suleiman †

Gaza Mon Amour (2020) dir. Tarzan Nasser, Arab Nasser †

The Viewing Booth (2020) dir. Ra'anan Alexandrowicz (on Amazon Prime and Apple TV)

Farha (2021)* | dir. Darin J. Sallam

Palestine Film Institute Archive

All links are for free viewing. The ones marked with a star (*) can be found on Netflix, while the ones marked † can be downloaded for free from my Mega account.

If you find Guy Davidi's Innocence anywhere please let me know, I can't find it for streaming or download even to rent or buy.

In 2018, BDS urged Netflix to dump Fauda, a series created by former members of IOF death squads that legitimizes and promotes racist violence and war crimes, to no avail. Please warn others to not give this series any views. BDS has not called for a boycott of Netflix. ]

NGOs

The Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) Movement

Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor

UNRWA

Palestine Defence for Children International

Palestinian Feminist Collective

Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network

Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association

Institute for Palestine Studies

Al Haq

Artists for Palestine

The Palestine Museum

Jewish Currents

B’Tselem

DAWN

Social Media

Palestnians on Tumblr

@el-shab-hussein

@killyfromblame

@apollos-olives

@fairuzfan

@palipunk

@sar-soor

@nabulsi

@wearenotjustnumbers2

@90-ghost

@tamarrud

@northgazaupdates

Allies and advocates (not Palestinian)

@bloglikeanegyptian beautiful posts that read like op-eds

@vyorei daily news roundups

@luthienne resistance through prose

@decolonize-the-left scoop on the US political plans and impacts

@feluka

@anneemay

(Please don't expect any of these blogs to be completely devoted to Palestine allyship; they do post regularly about it but they're still personal blogs and post whatever else they feel like. Do not harrass them.)

Gaza journalists

Motaz Azaiza IG: @motaz_azaiza | Twitter: @azaizamotaz9 | TikTok: _motaz.azaiza (left Gaza as of Jan 23)

Bisan Owda IG and TikTok: wizard_bisan1 | Twitter: @wizardbisan

Saleh Aljafarawi IG: @saleh_aljafarawi | Twitter: @S_Aljafarawi | TikTok: @saleh_aljafarawi97

Plestia Alaqad IG: @byplestia | TikTok: @plestiaaqad (left Gaza)

Wael Al-Dahdouh IG: @wael_eldahdouh | Twitter: @WaelDahdouh (left Gaza as of Jan 13)

Hind Khoudary IG: @hindkhoudary | Twitter: @Hind_Gaza

Ismail Jood IG and TikTok: @ismail.jood (announced end of coverage on Jan 25)

Yara Eid IG: @eid_yara | Twitter: @yaraeid_

Eye on Palestine IG: @eye.on.palestine | Twitter: @EyeonPalestine | TikTok: @eyes.on.palestine

Muhammad Shehada Twitter: @muhammadshehad2

(Edit: even though some journos have evacuated, the footage up to the end of their reporting is up on their social media, and they're also doing urgent fundraisers to get their families and friends to safety. Please donate or share their posts.)

News organisations

The Electronic Intifada Twitter: @intifada | IG: @electronicintifada

Quds News Network Twitter and Telegram: @QudsNen | IG: @qudsn (Arabic)

Times of Gaza IG: @timesofgaza | Twitter: @Timesofgaza | Telegram: @TIMESOFGAZA

The Palestine Chronicle Twitter: @PalestineChron | IG: @palestinechron | @palestinechronicle

Al-Jazeera Twitter: @AJEnglish | IG and TikTok: @aljazeeraenglish, @ajplus

Middle East Eye IG and TikTok: @middleeasteye | Twitter: @MiddleEastEye

Democracy Now Twitter and IG: @democracynow TikTok: @democracynow.org

Mondoweiss IG and TikTok: @mondoweiss | Twitter: @Mondoweiss

The Intercept Twitter and IG: @theintercept

MintPress Twitter: @MintPressNews | IG: mintpress

Novara Media Twitter and IG: @novaramedia

Truthout Twitter and IG: @truthout

Palestnians on Other Social Media

Noura Erakat: Legal scholar, human rights attorney, specialising in Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Twitter: @4noura | IG: @nouraerakat | (http://www.nouraerakat.com/)

Hebh Jamal: Journalist in Germany. IG and Twitter: @hebh_jamal

Taleed El Sabawi: Assistant professor of law and researcher in public health. Twitter: @el_sabawi | IG

Lexi Alexander: Filmmaker and activist. Twitter: @LexiAlex | IG: @lexialexander1

Mariam Barghouti: Writer, blogger, researcher, and journalist. Twitter: @MariamBarghouti | IG: @mariambarghouti

Rasha Abdulhadi: Queer poet, author and cultural organizer. Twitter: @rashaabdulhadi

Mohammed el-Kurd: Writer and activist from Jerusalem. IG: @mohammedelkurd | Twitter: @m7mdkurd

Ramy Abdu: Founder and Chairman of the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor. Twitter: @RamyAbdu

Subhi: Founder of The Palestine Academy website. IG: @sbeih.jpg |TikTok @iamsbeih | Twitter: @iamsbeih

‼️How You Can Help Palestine‼️

Click for Palestine (Please reblog!!)

Masterlist of donation links by @sulfurcosmos (Please reblog!!)

Water for Gaza: Donate directly to the Gaza Municipality

Gazafunds (vetted and spotlighted GFMs)

The Butterfly Effect Project (spreadsheet of vetted GFMs)

Operation Olive Branch has been removed in light of new revelations of unethical behaviour.

Spreadsheet of Gaza fundraisers vetted by @el-shab-hussein and @nabulsi

If any links are broken let me know. Or pull up the current post to check whether it's fixed.

"Knowledge is Israel's worst enemy. Awareness is Israel's most hated and feared foe. That's why Israel bombs a university: it wants to kill openness and determination to refuse living under injustice and racism."

— Dr. Refaat Alareer, (martyred Dec 6, 2023)

From River To The Sea Palestine Will Be Free 🇵🇸🇵🇸🇵🇸

-----

Edit 1: took the first video down because turns out the animator is a terf and it links to her blog. Really sorry for any distress.

Edit 2: All recommended readings + Haymarket recommendations + essential decolonization texts have been uploaded to my linked gdrive. I will adding more periodically. Please do buy or check them out from the library if possible, but this post was made for and by poor and gatekept Global South bitches like me.

Some have complained about the memes being disrespectful. You're actually legally obligated to make fun of Israeli propaganda and Zionists. I don't make the rules.

Edit 3: "The river to the sea" does not mean the expulsion of Jews from Palestine. Believing that is genocide apologia.

Edit 4: Gazans have specifically asked us to put every effort into pushing for a ceasefire instead of donations. "Raising humanitarian aid" is a grift Western governments are pushing right now to deflect from the fact that they're sending billions to Israel to keep carpet bombing Gazans. As long as the blockades are still in place there will never be enough aid for two million people. (UPDATE: PLEASE DONATE to the Gazan's GoFundMe fundraisers to help them buy food and get out of Rafah into Egypt. E-SIMs, food and medical supplies are also essential. Please donate to the orgs linked in the How You Can Help. Go on the strikes. DO NOT STOP PROTESTING.)

Edit 5: Google drive link for academic books folder has been fixed. Also have added a ton of resources to all the other folders so please check them out.

Edit 6: Added interactive maps, Jadaliya channel, and masterlists of donation links and protest support and of factsheets.

The twitter accounts I reposted as it was given to me and I just now realized it had too many Israeli voices and almost none of the Palestinians I'm following, so it's being edited. (Update: done!) also removed sources like Jewish Voices of Peace and Breaking the Silence that do good work but have come under fair criticism from Palestinians.

Edit 7: Complete reformatting

Edit 8: Complete revamping of the social media section. It now reflects my own following list.

Edit 9: removed some more problematic people from the allies list. Remember that the 2SS is a grift that's used to normalize violence and occupation, kids. Supporting the one-state solution is lowest possible bar for allyship. It's "Free Palestine" not "Free half of Palestine and hope Israel doesn't go right back to killing them".

Edit 10: added The Palestine Directory + Al Jazeera documentary + Addameer. This "100 links per post" thing sucks.

Edit 11: more documentaries and films

Edit 12: reformatted reading list

Edit 13: had to remove @palipunk's masterlist to add another podcast. It's their pinned post and has more resources Palestinian culture and crafts if you want to check it out

Edit 14 6th May '24: I've stopped updating this masterlist so some things, like journalists still left in Gaza and how to support the student protests are missing. I've had to take a step back and am no longer able to track these things down on my own, and I've hit the '100 links per post' limit, but if you can leave suggestions for updates along with links in either the replies or my asks I will try and add them.

Edit 15 10th August: added to Palestinian allies list and reworked the Help for Palestine section. There's been a racist harrassment campaign against the Palestinian Tumblrs that vetted the Gaza fundraisers based off one mistake made by a Gazan who doesn't understand English. If you're an ally, shut that shit down. Even if you donate to a scam GFM, you're only out some coffee money; if everyone stops donating to all the GFMs in fear of scams, those families die.

Edit 16: removed entire section of allied accounts since the liberation of Syria because apparently leftists in the West are unable to both be against the Israel's genocide of Palestinians and Assad's genocide of Syrians. I should have treated the use of "Axis of Resistance" as the Tankie dog whistle it was.

Edit 17: Removed the Uncommitted Movement to pressure the Harris Presidential Campaign for obvious reasons.

Edit 18: Operation Olive Branch has come under fire for their lack of transparency, unethical behaviour and reporting their own volunteers to the FBI. Always be wary of white people spearheading anything to do with liberatory movements, from conversations to organizations.

#free palestine#palestine resources#palestine reading list#decolonization#israel palestine conflict#israel palestine war#british empire#american imperialism#apartheid#social justice#middle east history#MENA#arab history#anti zionism#palestinian art#palestinian history#palestinian culture#palestinian genocide#al nakba#ethnic cleansing#war crimes#racism#imperialism#colonialism#british colonialism#knee of huss#ask to tag#Youtube

83K notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

The 1936-9 Palestinian Revolt is the forgotten war in the 102 years of Israeli-Palestinian conflict:

This war, the forgotten war of the 102 years, is forgotten not least because it marks an abrupt point where both the Palestinian nation was forged into one.....and because it was directed at the British Empire more than the Yishuv, even if plenty of Jews were killed as what was ultimately collateral damage in an anti-British revolt. The reality of a war like this is the apple in the ointment of a simpler narrative that treats the Palestinian Arabs as exceptions to broader trends when in reality this war has a great many parallels to the rebellions in Iraq, Syria, and the rise of the Saudi dynasty in the Hijaz, as well as rebellions in Egypt and Libya.

The main difference is that in addition to the British it In three years the great war that followed marked a turning point, the final steps in making a nation out of three Sanjaks of the Vilayet of Damascus, providing the basis for the idea that the peoples who were Christian and Muslim and spoke Arabic were indeed Palestinians, and not Southwestern Syrians or the Ummah with its semi-tolerated at best Christian and Jewish hangers-on.

While written by an Israeli, this is a book that repeatedly notes both the very bluntness of the views of the Yishuv, that the Jabotinsky/Irgun crowd viewed the war precisely for what it was, the birth of a new nationalism, and that the combination of the war, its success in pressuring the British to ban Jewish immigration....which by then still didn't satisfy Palestinians, the breaking of their military power denied them the chance to keep the war going did was ultimately the Pyrrhic victory that lost them the 1947-8 war with the Yishuv before it even started.

10/10.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jordan Independence Day Amman

Jordanian Flag Independence Day – Edarabia May 25 is Jordan Independence Day, and the “most important event in the history of the country, marking its independence from the British government in 1946”. The 2023 celebration signifies 75 years since Jordan “officially gained full autonomy in 1948“. King Abdullah I bin Al-Hussein “Jordan’s independence took place during the reign of King Abdullah I…

View On WordPress

#Al Shareef Hussein Bin Ali – Emir of Mecca - King of the Hijaz - King of the Arabs#Arab League#Arab Revolt Against the Ottoman Empire#Autonomous Constitutional Monarchy#Council of the League of Nations#Emirate of Transjordan#Great Arab Revolt#Hashemite Army of the Great Arab Revolt#Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan#Hashemites#His Majesty King Abdullah I Emir of Transjordan 1921-1946#His Majesty King Abdullah II – King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 1999 to Present#His Majesty King Al Hussein – King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 1952-1999#His Majesty King Talal – King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 1951-1952#House of Hashem#Jordan 1946 Independence from the British Government#Jordan Houses – Senate - House of Representatives#Jordan Independence Day May 25#Jordan WWI Allies Britain and France#Jordanian Armed Forces#Khamaseen Winds#King Abdullah I bin Al-Hussein#King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 1946-1951#Ottoman Empire#Presentation of Colours Ceremony#Sharif Hussein of Mecca#The Emir#Transjordan#Transjordan Memorandum#United Nations

1 note

·

View note

Text

Since the early days of British involvement with Zionism, Churchill sanctioned the dispossession of non-Jewish Palestinians by assuring that they have no voice in the affairs of their own land. “In the interests of the Zionist policy,” he stated in August 1921 as the government minister in charge of Britain’s colonies, “all elective institutions have so far been refused to the Arabs.”

A snapshot of Churchill’s stances on Palestine and race is found in the records of the 1937 Peel Commission hearings, convened to address a major revolt in Palestine. [...]

Horace Rumbold [...] asked whether Zionist policy is worth “the lives of our men, and so on.” And did it follow, he asked Churchill, that having “conquered Palestine we can dispose of it as we like?”

Churchill replied to that and similar questions by invoking commitments given when Britain captured Palestine toward the end of 1917. “We decided in the process of conquest of [Palestine] to make certain pledges to the Jews,” Churchill said.

Apparently skeptical, the head of the commission, William Peel, asked Churchill if it is not “a very odd self-government” when “it is only when the Jews are a majority that we can have it.”

Churchill responded with a blunt argument of might: “We have every right to strike hard in support of our authority.”

The historian Reginald Coupland nonetheless told the hearings that the “average Englishman” would wonder why the Arabs were being denied self-government, and why we had “to go on shooting the Arabs down because of keeping his promise to the Jews.”

Peel, similarly, asked Churchill if the British public “might get rather tired and rather inquisitive if every two or three years there was a sort of campaign against the Arabs and we sent out troops and shot them down? They would begin to enquire, ‘Why is it done? What is the fault of these people?… Why are you doing it? In order to get a home for the Jews?’”

“And it would mean rather brutal methods,” added Laurie Hammond, who had worked with the British colonial administration in India. “I do not say the methods of the Italians at Addis Ababa,” referring to Benito Mussolini’s Ethiopian massacre of February 1937, “but it would mean the blowing up of villages and that sort of thing?” The British, he recalled, had blown up part of the Palestinian port city of Jaffa.

Peel agreed, and added that “they blew up a lot of [Palestinian] houses all over the place in order to awe the population. I have seen photographs of these things going up in the air.”

But when Peel questioned whether “it is not only a question of being strong enough,” but of “downing” the Arabs who simply wanted to remain in their own country, Churchill lost patience.

“I do not admit that the dog in the manger has the final right to the manger,” he countered, “even though he may have lain there for a very long time.” He denied that “a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America, or the Black people of Australia,” by their replacement with “a higher grade race.”

#churchill explicitly compared what was being done to palestinians as equivalent to what was done to indigenous populations in aus and us#heard it on the podcast episode and looked it up#zionism#palestine

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Got a huge biography of this legendary figure on my bed right now, and once I finish it, I will have earned the right to watch the legendary film, Lawrence of Arabia.

Colonel T E Lawrence on the balcony of the Victoria Hotel in Damascus on 3 October 1918, half an hour after he had resigned his position in the Arab Army.

#t.e. lawrence#history#ww1#great war#british army#arab revolt#middle east#aqaba#jidda#emir feisal#ibn saud#british empire#ottoman turks#lawrence of arabia

23 notes

·

View notes

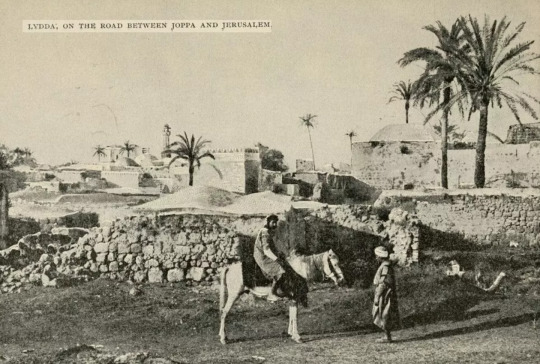

Text

"Following the 1948 massacre at Dahmash Mosque, the inhabitants of Lydda, already terrorized from the massive death toll accompanying the attack, were expelled in the now-infamous 'Lydda death march.' Men, women, and children were marched out of town and driven toward Ramallah and the Jordan River valley. With no time to collect supplies and no reprieve from the arduous trek through the desert heat, an unknown number of Palestinians perished. Of the group affected, children were a disproportionate number of casualties strewn along the path being forged out of Lydda; 'Nobody will ever know how many children died,' Israeli soldier John Bagot Glubb recounted in his memoir. The expulsion of Palestinians from their ancestral homes in Lydda successfully transformed the town into a 'death zone.' As [Spiro] Munayyer recalled: 'At sunset we could still hear the firing of automatic weapons which went on until nightfall, when silence descended on the city. We no longer could hear shooting or the crying of children nor the lamentations of women. It was as though the city itself had died.'

Settler colonialism necessitates the eradication of Indigenous life so that a new society can be forged from the ruins of expulsion. As Israeli reporter and writer Ari Shavit wrote for The New Yorker when discussing the violence in Lydda: 'The truth is that Zionism could not bear the Arab city of Lydda. From the very beginning, there was a substantial contradiction between Zionism and Lydda. If Zionism was to exist, Lydda could not exist. If Lydda was to exist, Zionism could not exist.'" Incarcerated Childhood and the Politics of Unchilding, Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian (2019) Lydda in the late 19th and early 20th century, before the British Mandate:

Lydda in 1935-1940, the period of the Great Palestinian Revolt against the British Mandate:

The Nakba in Lydda:

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

Free!

"Leave our country alone!" they say "This isn't your land - go back to where you came from!"

And as my brother's being shoot, And my sister's being paraded naked - For their great sin of: living [Re'im, Israel, 2023]

As my great-grandfather was pushed down in the streets And his beard was brutally shaved As they raped and enslaved and murdered- [Birkenau, Poland, 1943]

[just like in 1941 Farhud, Iraq ; Jedwabne pogrom; 1945 Tripoli pogrom, the 1946 Kielce pogrom, and the 1947 Aleppo pogrom]

In 1934 there were pogroms against Jews in Turkey and Algeria.

Other parts of my family were lucky enough to survive the 1929 Hebron massacre during the 1929 Palestine riots. [Mandatory Palestine under British administration]

In 1919, soldiers marched into the center of town accompanied by a military band and engaged in atrocities under the slogan: "Kill the Jews, and save the Ukraine." They were ordered to save the ammunition in the process and use only lances and bayonets during the Proskurov pogrom.

[Proskurov, Ukraine, 1919]

[100 years, and nothing changed, huh?]

You know, my grandma's arab. I still remember sitting in class in high school, hearing about the 1840 Damascus affair, and thinking: hu.

I'll skip several years and countries, but:

Their grandparents were there to witness as the outbreak of violence against Jews (Hep-Hep riots) occurred at the beginning of the 19th century.

The 1821 Odessa pogroms marked the beginning of the 19th century pogroms in Tsarist Russia

That's Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648–1657 in present-day Ukraine.

So they said, during the attacks against Jews also took place in Barcelona and other Catalan cities during the massacre of 1391.

Their ancestors were cast away and murdered in Spain, 1492.

The same way we were banished and cast away from Bern (1427) and Zürich (1436) for almost 400 years?

Let us not speak of the alaughter on Holy Saturday of 1389, a pogrom began in Prague that led to the burning of the Jewish quarter, the killing of many Jews, and the suicide of many Jews trapped in the main synagogue; the number of dead was estimated at 400–500 men, women, and children.

Brussels massacre of 1370.

Or - do you want to hear about the 510 jewish communities that were destroyed? (1348-1350) including in Toulon, Erfurt, Basel, Aragon, Flanders[16][17] and Strasbourg.[18]

Just like Rhineland massacres in 1096

Some of them made it to England, around 1060. It took less than 30 years for the first Podrom in 1189-90 in England,

Oh, and let us not forget 1066 Granada massacre [again, in Spain].

Or the Alexandria in the year 38 CE, followed by the more known riot of 66 CE.

The Jewish population of the land on the eve of the first major Jewish rebellion [66 CE] may have been as high as 2.2 million. The monumental architecture of this period indicates a high level of prosperity.

In 66 CE, the Jews of Judea rose in revolt against Rome, sparking the First Jewish–Roman War. The reverse seized control of Judea and named their new kingdom "Israel"

The revolt was crushed by the Roman emperors Vespasian and Titus. The Romans destroyed much of the Temple in Jerusalem and took as punitive tribute the Menorah and other Temple artifacts back to Rome. Josephus writes that 1,100,000 Jews perished during the revolt, while a further 97,000 were taken captive. The Fiscus Judaicus was instituted by the Empire as part of reparations.

[And here we come to a full cycle of blood, land, and pain].

And those are only those I found out about. Only those we have a record of. Only those we know to this day. They were so massive, or left enough impact so we still remember.

[I could go on, this is just a short list.]

It seems like no matter what we do, we'll always be accused for

Let me know, please - where can I be a jew, and just

Live?

#israel#jews#jewish history#history#palestine#Juda kingdom#pogrom#pogroms#terror#manslaughter#massacre

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

World War I. Middle East. The operations of the Arab army: an observation post of rifle-machine gunners; at the bottom, the Hejaz mountains. 1917

#wwi#arab revolt#ww1#the great war#arab#middle east#first world war#world war 1#photography#world war i#1910s#world war one#world war#war history#tumbler#wwi era#ww1 era#ww1 history#wwi history#history

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arrival of Rurik to Ladoga by Viktor Vasnetsov (1848-1926)

"The Povest' preserves the tradition that the Slavic tribes of Northern Russia, in common with their Finnish neighhors, were for some time tributary to the "Varangians from beyond the sea." Stirred to revolt by the exactions of the latter the Slavs eventually rebelled, but were unable, according to the Povest' to arrive at any satisfactory inter-tribal understanding. To escape from the resulting confusion, the Povest' thus reports that they sent overseas "to the Varangian Russes," saying, "Our land is great and rich, but there is no order in it; come and rule and have dominion over us." This invitation was accepted by Rurik and his brethren, each of whom assumed control over a north-Russian centre, with Rurik himself at Novgorod, Sineus at Beloozero, and Truvor at lzborsk. Such, in its simplest terms, is the narrative of the "calling of the princes".

-The Russian Primary Chronicle. Laurentian Text. Translated and edited by Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor

...

"In the year 6362 (854) (...) And the Slovenes and Krivitsi and Merya and Chud rose against the Varangians and expelled them beyond the sea; and they began to rule themselves and set up cities. And they arose to fight with themselves, and there was great strife and discord between them, and they rose up city upon city, and there was no righteousness among them. And they resolved to themselves: "Let us look for a prince who would rule over us and reward us according to our rights." They went over the sea to the Varangians and said: "Our land is great and plenty, but we have no order; so come to us to reign and rule us".

-Novgorod First Chronicle

...

The Arab historian, al-Masudi, gives a similar description: "The Saqāliba [Slavs] are divided into several different peoples who war among themselves". From Ibn Rusta: "The Rūs raid the Saqāliba [Slavs], sailing in their ships until they come upon them. They take them captive and sell them in Khazarān and Bulkār (Bulghār). They have no cultivated fields and they live by pillaging the land of the Saqāliba [Slavs]". The Finns have accurately kept the name Rus [Ruotsi] for the nation of Sweden, from whence the original Germanic Rus came.

#kievan rus#swedish history#middle ages#medieval history#paintings#european art#history#european history#slavic#finno ugric#varangian

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Israeli territory and Palestinian territories

« Atlas des frontières », Hugo Billard & Frédéric Encel, Autrement, 2021

by cartesdhistoire

At the Versailles Peace Conference (1919), the Zionist Organization presented its map of territorial claims: Palestine (or Eretz Israel) plus southern Lebanon, the east bank of the Jordan and the Golan Heights. On the Arab side, a great unified and sovereign Arab kingdom was demanded (Damascus Congress, 1919).

During the Arab Revolt in Palestine (1936), London proposed a division on a demographic basis: the northern coastal strip and the Galilee to the Jews, the West Bank, the southern coastal strip, the Negev desert and the Jordan valley to the Arabs. This Peel plan was finally abandoned in the face of refusal from the Palestinian High Committee and the Arab states. However, except for the Negev which returned to the Jewish State, it was nevertheless a fairly similar sharing plan that the UN adopted on November 29, 1947: two almost equal shares and a "corpus separatum" including Jerusalem and Bethlehem under international supervision. The Zionist Organization accepts, the Arabs reject it and start a war whose outcome, favorable to the young Hebrew State, allows it to expand and Jordan to annex most of the Arab State of Stillborn Palestine: the West Bank, or Judea-Samaria, and East Jerusalem. This new geopolitical reality will serve as a basis for negotiations in the Oslo (1993) and Camp David II (2000) peace processes.

Meanwhile, at the end of the Six Day War (1967), Israel will have conquered the strategic Golan Heights from Syria (annexed in 1981), the West Bank from Jordan (which Amman renounced in 1988), and East Jerusalem. (annexed in 1967), the Gaza Strip (returned to the Palestinian Authority in 2005 and controlled by Islamist Hamas since its 2007 putsch) and the Sinai (returned to Egypt via the 1978 Camp David peace accords ).

Finally, if the borders with Syria and Lebanon remain contested and often resemble reopened fronts (Hezbollah), those with Jordan and Egypt are recognized and pacified.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

@shlomo_fishman

One of the main foundations of the Palestinian narrative states that: "according to international law, Israel is occupying Palestinian land".

What most people don't know is that the international law states, in fact, the exact opposite. I'll explain.

In the picture below, you can see article 80 in the UN charter, signed by the UN in 1945 during the San Francisco convention. As stated, its purpose was to ensure the rights given by trusteeship agreements approved by the UN, one of them being the British Mandate which officially began in 1920 and was designated to the establishment of a "national home" for the Jewish people on the area shown in the map below, as previously declared in the Balfour Declaration in 1918.

Now you may say: "but what about the UN general assembly Resolution 181 (the partition plan)?". The answer here is pretty simple: first of all, the general committee has no official power to enforce their decisions, which are mostly symbolic. Second, the plan was never set in motion, as the Arab leadership refused to accept it and the war between the Jewish population and the Arab one, broke down. Regarding the UN security council, Article 24(2) states: "the Security Council shall act in accordance with the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations". Which means it also cannot overrule article 80 in the UN charter.

There is also an argument I heard, about the British Mandate being a class A mandate. Class A mandates, were territories formerly controlled by the Ottoman Empire that were deemed to "... have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognized subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone. The wishes of these communities must be a principal consideration in the selection of the Mandatory". There is one major problem with this argument: the Muslim Arabs NEVER had any national ambitions back then, nor wanted an independent state until after 1948.

Haj Amin Al-Husseini, probably the most prominent Muslim leader during the British Mandate and the Mufti of Jerusalem at that time, who dedicated his life to combat Zionism and purge the Jewish population in the area, even reaching Adolf Hitler at some point to help him fulfill those plans, never wanted an establishment of an independent Muslim state.

While launching massacres against the Jewish population (the great Arab revolt, 1929 Arab riots and more) and trying to convince Arabs not to sell lands to Jews, he justified it only using religious Islamic motives and blood libels against the Jews. Their only mission was to erase Zionism, so there was never an appeal by him, nor the Arab League and not any other Muslim leadership of that time to the international community, for the establishment of a Muslim state called "Palestine".

So when I define the Palestinians as: "a political movement pretending to be a nation, only to combat Zionism", I talk about this exactly.

This text sums up the main things you should know about the non-existent Israeli occupation, which many people unfortunately don't. So it was very important to me to write about it, especially in these difficult times, and I'd appreciate your support in spreading this message, a lot.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Below are 10 featured Wikipedia articles. Links and descriptions are below the cut.

The election in 1860 for the position of Boden Professor of Sanskrit at the University of Oxford was a competition between two candidates offering different approaches to Sanskrit scholarship. One was Monier Williams, an Oxford-educated Englishman who had spent 14 years teaching Sanskrit to those preparing to work in British India for the East India Company. The other, Max Müller, was a German-born lecturer at Oxford specialising in comparative philology, the science of language.

Adolfo Farsari (Italian pronunciation: [aˈdolfo farˈsaːri]; 11 February 1841 – 7 February 1898) was an Italian photographer based in Yokohama, Japan. His studio, the last notable foreign-owned studio in Japan, was one of the country's largest and most prolific commercial photographic firms. Largely due to Farsari's exacting technical standards and his entrepreneurial abilities, it had a significant influence on the development of photography in Japan.

Girl Pat was a small fishing trawler, based at the Lincolnshire port of Grimsby, that in 1936 was the subject of a media sensation when its captain took it on an unauthorised transatlantic voyage. The escapade ended in Georgetown, British Guiana, with the arrest of the captain, George "Dod" Orsborne, and his brother. The pair were later imprisoned for the theft of the vessel.

Abu Muhammad Hasan al-Kharrat (Arabic: حسن الخراط Ḥassan al-Kharrāṭ; 1861 – 25 December 1925) was one of the principal Syrian rebel commanders of the Great Syrian Revolt against the French Mandate. His main area of operations was in Damascus and its Ghouta countryside. He was killed in the struggle and is considered a hero by Syrians.

Marjorie Cameron Parsons Kimmel (April 23, 1922 – July 24, 1995), who professionally used the mononym Cameron, was an American artist, poet, actress and occultist. A follower of Thelema, the new religious movement established by the English occultist Aleister Crowley, she was married to rocket pioneer and fellow Thelemite Jack Parsons.

Maya stelae (singular stela) are monuments that were fashioned by the Maya civilization of ancient Mesoamerica. They consist of tall, sculpted stone shafts and are often associated with low circular stones referred to as altars, although their actual function is uncertain. Many stelae were sculpted in low relief, although plain monuments are found throughout the Maya region. The sculpting of these monuments spread throughout the Maya area during the Classic Period (250–900 AD), and these pairings of sculpted stelae and circular altars are considered a hallmark of Classic Maya civilization.

The North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) is an area of European importance for wildlife in Norfolk, England. It comprises 7,700 ha (19,027 acres) of the county's north coast from just west of Holme-next-the-Sea to Kelling, and is additionally protected through Natura 2000, Special Protection Area (SPA) listings; it is also part of the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). The North Norfolk Coast is also designated as a wetland of international importance on the Ramsar list and most of it is a Biosphere Reserve.

Preening is a maintenance behaviour found in birds that involves the use of the beak to position feathers, interlock feather barbules that have become separated, clean plumage, and keep ectoparasites in check. Feathers contribute significantly to a bird's insulation, waterproofing and aerodynamic flight, and so are vital to its survival. Because of this, birds spend considerable time each day maintaining their feathers, primarily through preening.

The Wells and Wellington affair was a dispute about the publication of three papers in the Australian Journal of Herpetology in 1983 and 1985. The periodical was established in 1981 as a peer-reviewed scientific journal focusing on the study of amphibians and reptiles (herpetology). Its first two issues were published under the editorship of Richard W. Wells, a first-year biology student at Australia's University of New England. Wells then ceased communicating with the journal's editorial board for two years before suddenly publishing three papers without peer review in the journal in 1983 and 1985. Coauthored by himself and high school teacher Cliff Ross Wellington, the papers reorganized the taxonomy of all of Australia's and New Zealand's amphibians and reptiles and proposed over 700 changes to the binomial nomenclature of the region's herpetofauna.

Wulfhere or Wulfar (died 675) was King of Mercia from 658 until 675 AD. He was the first Christian king of all of Mercia, though it is not known when or how he converted from Anglo-Saxon paganism. His accession marked the end of Oswiu of Northumbria's overlordship of southern England, and Wulfhere extended his influence over much of that region.

26 notes

·

View notes