#Transjordan Memorandum

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

sense Jerusalem is trending rn i thought it was a good time to address this

YES, PALESTINE DID EXIST PRIOR TO ISRAEL COLONIZATION

the oldest use of the name Palestine to refer to that region(i.e. land from egypt to phoenicia) dates to the 5th century BCE in herodotus's histories. and is later used by other greek writers like aristotle, polemon, and later pausanias

later on the name is also used by roman writers like ovid, tibullus, pliny the elder, statius and other. and before a zionist comes in and accuses me of antisemitism. the name is also used to refer to the same region by the philosopher philo of alexandria and historian josephus. two romano-JEWISH writers. have fun accusing them of antisemitism

and if "name of the region" isn't enough, it became the official name for the province under roman authorities, the first mention of the name as an official province name being in 135CE. the name continues on through the byzantine empire(a.k.a eastern roman empire), stayed through the muslim conquest by the rashidun caliphate until the end of the ottoman empire's rule over the region where Britain came in and the "League of Nations – Mandate for Palestine and Transjordan Memorandum" was signed establishing the colony of israel(a.k.a the Zionist fascist actively committing a genocide rn)

now on to the Palestinian people them selves

as for the people, a group named something along the lines of "peleset" is named as a neighboring group starting from 1150BCE in egypt as well the name palashtu(or pilistu) is mentioned in assyrian inscriptions on the nimrud slab around 800BCE

Palestinians are Canaanites by genetics, which means that they are related to other local groups of canaan and the levant like the Phoenicians

and for the zionists who like to pretend to care about Judaism, or the tanakh, the philistines is attested to in the torah and later in the books of judges and Samuel(does the name Goliath of GAZA ring any bills?).

zionists are white colonists who don't represent jews nor care about jews as anything more than a shield for criticism.

don't stop talking about palestine

#gaza#palestine#free palestine#free gaza#social justice#imperialism#colonialism#ceasefire now#palestine resources#palestine genocide#from river to sea palestine will be free#palestinian genocide#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#jerusalem

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

British Foreign Office memorandum, 1927 version of the Treaty of Sèvres, Sykes–Picot agreement, Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

The parliament of Transjordan made Abdullah I of Jordan their Emir on May 25, 1946.

Jordan’s Independence Day

Jordan’s Independence Day is celebrated on May 25 every year, and is the most important event in the history of Jordan, as it commemorates its independence from the British government. After World War I, the Hashemite Army of the Great Arab Revolt took over the area which is now Jordan. The Hashemites launched the revolt, led by Sharif Hussein, against the Ottoman Empire. The Allied forces, comprising Britain and France supported the Great Arab Revolt. Emir Abdullāh was the one who negotiated Jordan’s independence from the British. Though a treaty was signed on March 22, 1946, it was two years later when Jordan became fully independent. In March 1948, Jordan signed a new treaty in which all restrictions on sovereignty were removed to guarantee Jordan’s independence. Jordan joined and became a full member of the United Nations and the Arab League in December 1955.

History of Jordan Independence Day

The first appearance of fortified towns and urban centers in the land now known as Jordan was early in the Bronze Age (3600 to 1200 B.C.). Wadi Feynan then became a regional center for copper extraction with copper at the time, being largely exploited to facilitate the production of bronze. Trading, migration, and settlement of people in the Middle East peaked, thereby advancing and refining more and more civilizations. With time, villages in Transjordan began to expand rapidly in areas where water resources and agricultural land abound. Ancient Egyptians then later expanded towards the Levant and would eventually control both banks of the Jordan River.

There was a period of about 400 years during which Jordan was under the rule and influence of the Ottoman Empire, and the period was characterized by stagnation and retrogression to the detriment of the Jordanian people. The reign of the Ottoman Empire over Jordan would eventually cease when Sharif Hussein led the Hashemite Army in the Great Revolt against the Ottoman Empire, with the Allies of World War I supporting them. In September 1922, the Council of the League of Nations recognized Transjordan as a state under the terms of the Transjordan memorandum. Transjordan remained under British mandate until 1946, when a treaty was signed, with eventual sovereignty being granted upon signing a subsequent treaty in 1948.

The Hashemites’ assumption of power in the Jordan region came with numerous challenges. In 1921 and 1923, there were some rebellions in Kura which were suppressed by the Emir’s forces, with British support. Jordan is generally a peaceful region today, and it has become quite a tourist destination in recent times.

Jordan Independence Day timeline

3600 B.C. Earliest Known Jordanian Civilizations

Fortified towns and urban centers begin to spring up in the area now known as Jordan.

1922 Jordan is Recognized as a State

In 1922, the Council of the League of Nations recognizes Jordan as a state under the Transjordan memorandum.

1946 First Independence Treaty is Signed

In 1946, Emir Abdullāh negotiates the first independence treaty with Britain which would later lead to Jordan's ultimate independence in 1948.

1955 Jordan Joins the United Nations

Jordan becomes a member of the United Nations and the Arab League in 1955.

Jordan Independence Day FAQs

What day is Jordan’s Independence Day?

Jordan’s Independence Day is May 25, every year. It marks the anniversary of the treaty that gave Jordan her sovereignty.

When did Jordan become independent?

On May 25, 1948, Jordan officially became an independent state.

Who is Jordan’s current leader?

The current ruler Of Jordan is the monarch, Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein, King of Jordan.

How to Observe Jordan Independence Day

Light up some fireworks

Prepare some mansaf

Share on social media

One of the hallmark celebrations of any independence day is the show of fireworks. Be sure to be a part of the beauty!

As you probably already knew, Mansaf is Jordan’s national dish. As such, preparing it on such a special day as Independence Day is a brilliant idea.

Take pictures and videos of you in your dishdasha celebrating Independence Day. Share them on your social media!

5 Interesting Facts About Jordan

Home to the Dead Sea

A nexus between Africa, Europe, and Asia

Over 100,000 archeological sites

The world’s oldest dam

Jesus was baptized in Jordan

The Dead Sea, which is the lowest point on Earth, is located in Jordan.

Jordan is a pivotal point connecting Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Jordan has over 100,000 archeological and tourist sites.

Jordan is home to the world’s oldest dam, the Jawa Dam.

Jesus, who is the symbolic character of the Christian faith, was baptized in the Jordan River before beginning his ministry.

Why Jordan Independence Day is Important

Jordan is peaceful and liberal

The weather in Jordan is nice

Jordan is a tourist’s dream

Though a generally conservative country, Jordan is relatively liberal. The country is peaceful and tolerant of foreign cultures.

Jordan is a warm region. The weather is usually warm and pleasant at all times of the year.

Jordan has everything a tourist could dream of. Beautiful sights, calm weather, a welcoming culture, and amazing people make it a fantastic place for tourists.

Source

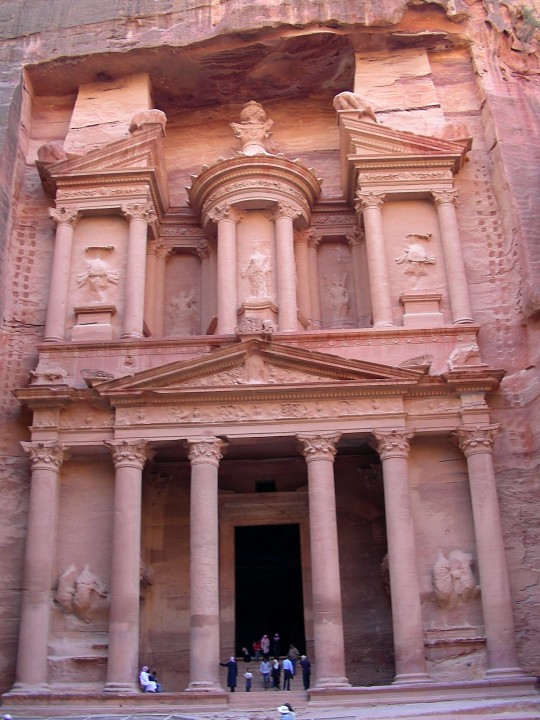

#Petra#Amman#Aqaba Fortress#Aqaba#Jerash#ruins#architecture#travel#archaeology#cityscape#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#summer 2007#Jordan#Asia#Middle East#Gadara#Dead Sea#Wadi Mujib#Wadi Rum#desert#Kerak Castle#Abdullah I of Jordan#Emir#25 May 1946#anniversary#Jordan history#vacation#Jordan’s Independence Day

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Two-State Solution

You would think that by now no amount of hypocrisy on the part of the great world out there could surprise, let alone startle, me at this point. Even I think that! And yet I find myself consistently amazed to find myself amazed at the duplicity of our so-called friends, not to mention the out-and-out phoniness of self-proclaimed allies who insist that they only want the best for the Jewish people or for the State of Israel.

If I had nothing to do for the rest of my life I could begin a list. But since my time is limited, I’ll settle for writing about our “friends” who have suddenly discovered, or rather re-discovered, the “two-state solution” as the cure for all that ails Israel and its neighbors. And they are legion: I’ve lost track of how many different newspaper articles I read this last week alone in which the author breathlessly announces that the reason the entire Arab-Israeli sikhsukh wasn’t resolved long ago has to do with the intransigence of Israelis with respect to the famous “two-state” solution, the compromise invariably touted by such authors as the obvious panacea to all that ails the Middle Eastern world. Here, for example, is a story from Taiwan explaining to readers of the Taipei Times how things would calm down instantly if only Bibi would heed President Biden’s call for a “two-state solution.”

The notion itself of a two-state solution to the Arab-Israeli problem, of course, is as old as the state itself and, in fact, there actually are two states, one Arab and one Jewish on the territory of the old British Mandate of Palestine. Or, rather, there would be had the British not unilaterally sawn the entire kingdom of Jordan, then called Transjordan, off of the mandated territory and offered it to the Hashemites as their own country. So the U.N. was dealing with the part that was left and that, indeed, they voted on November 22, 1947, voted to split down into two nations, a Jewish one and an Arab one.

The next part, everybody knows. The Jews of the yishuv accepted the plan and declared independence on May 14, 1948. (Our apartment in Jerusalem is actually just half a mile or so from November 22nd Street, a pretty place named specifically in honor of the U.N. decision.) The Arabs of British Palestine, however, did not follow suit and declare their own state. Instead, they went to war and lost, which failure laid the groundwork for the subsequent seventy-five years of hostility towards the Jewish state.

Whatever the problem really is, it certainly doesn’t have to do with not enough ink having been spilt—or time wasted—trying to work things out. The Madrid Conference of 1991, the Oslo Accords of 1991 and 1993, the Wye Plantation Memorandum of 1998, the Camp David Summit of 2000, the Annapolis Conference of 2007, the John Kerry shuttle diplomacy of 2013, the Trump administration’s “Peace to Prosperity” plan of 2020—all of these were “about” the two-state solution, each in its own way an effort to finesse the details while ignoring the fact that only one party to the dispute seemed even remotely interested in recognizing the other’s right to nationhood. Nor does the concept lack international sponsors: a quick google of “international leaders in favor of a two-state solution” yields a very impressive list, a list that includes President Biden, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, German Chancellor Olaf Scholtz, British P.M. Rishi Sunak, French President Emmanuel Macron, Canadian P.M. Justin Trudeau, Australian P.M. Anthony Albanese, New Zealand P.M. Christopher Luxon, and, saving the best for last, Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan. They are all on board!

Most impressive of all is that a full 138 nations have alreadyrecognized the State of Palestine, the fact that none of the above efforts to create a viable two-state solution has succeeded waved away as a mere detail hardly worth mentioning.

So, all that being the case, what actually is the problem? Just this week, we were exposed to the current administration’s pique with Israeli P.M. Netanyahu for not being fully enough behind the two-state solution. The L.A. Times had a particularly interesting op-ed piece on the topic (click here). CNN’s piece (click here) was also quite good. And, of course, nothing could ever deter the New York Times from trying to pry some space out between the Biden and Netanyahu administrations, of which only the latest examples appeared in the last few days: Peter Baker’s “Netanyahu Rebuffs U.S. Calls to Start Working Towards Palestinian Statehood,” Thomas Friedman’s “Netanyahu Is Turning Away from Biden,” or Aaron Boxerman’s “Biden Presses Netanyahu On Working Towards Palestinian State.”

So, okay, I get it. The only solution is the two-state one. But why is everybody so irritated with Israel? The Palestinians could solve the problem overnight by declaring their independence, agreeing quickly to exchange ambassadors with the 130+ nations that already recognize their state, and getting down to the gritty business of negotiating safe and secure border with Israel. Bibi would probably not be pleased. But what could he do? The entire world would be on the Palestinians’ side and all it would take was a single unilateral announcement on the part of the Palestinians to get the ball rolling. The presence of Jewish so-called “settler” types in Judah and Samaria would not be a problem unless the State of Palestine intended itself to be totally judenrein—otherwise, why couldn’t those people live on their own land in an independent Palestine if they wanted to? (Most, I think, would not want to. But some surely would.) Nor would the status of Jerusalem itself be an issue: while the Palestinians are in unilateral-proclamation-mode, they could simply declare East Jerusalem to be their capital, then get down to work organizing a workable plan with Israel for policing the city, controlling traffic, and figuring out who picks up whose trash on which days.

Yes, I’m making light of intense issues. But, at the end of the day, why precisely couldn’t this happen? Everybody is happy to be irritated with Bibi, but Israel has demonstrated over and over—including in the context of all the above-listed conferences—that it is ready to negotiate for peace. And declaring independence would assist in Gaza as well: terror organizations like Hamas flourish in the atmosphere of hopelessness and desperation, but that would quickly move into the past if the Palestinians were occupied with nation-building and self-determination instead of endlessly complaining that the world hasn’t given them enough aid. If the Jordanians were big-enough hearted to create a kind of economic union with New Palestine, then there really would be no stopping the peace train. Even the United Nations would be unable to stop the momentum.

But, of course, none of the above has happened or, I fear, ever will happen. It’s much easier for the Biden administration to waste its time trying to bully Bibi into making concessions in the context of theoretical negotiations in which the other side has not given the slightly indication it wishes to participate. Yes, it’s more dramatic to build terror tunnels, murder babies, rape women, and take innocent civilian hostages. But that cannot—and will not—ever lead to statehood for Palestine. What will lead in that direction is the clear indication that the Palestinian leadership is prepared to create a viable Palestinian state and then to live within its borders peacefully and productively.

If the United States wants to defang Iran and lessen the likelihood that the Iranians will lead the world into World War III, it could take no more profound and potentially meaningful step forward than convincing the Palestinians to stop complaining, to take the independence the entire world wishes to offer them seriously, and to get down to the actual business of nation-building. The mullahs will be outraged. But they’ll get over it. And the world will be a safer and better place.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I've been busy with a long memorandum about the whole of our central Arabian relations, which I've just finished. It will now go to all the High and Mighty in every part. One can't do much more than sit and record if one is of my sex, devil take it; one can get the things recorded in the right way and that means, I hope, that unconsciously people will judge events as you think they ought to be judged. But it's small change for doing things, very small change I feel at times.

- Gertrude Bell, Letters of Gertrude Bell (1929)

The First World War and its aftermath are a story of disappointment and depression for Bell. Early on, she sees the war as the “end of the order we’re accustomed to” - a Whiggish order in which she had believed that British power could be exercised for good; she witnesses and fears the general abandonment of the belief that “there’s room enough in the sun” for everyone. Scales fell from her eyes earlier for her than for others of her class charged with redrawing the map of the Middle East and especially the fate of the Arabs.

Just before the installation of Prince Feisal, the not-yet-Iraqi tribes rebel. The colonial administration wants to adopt the position vacated by the Ottomans and demands of each tribe a poll tax. These are the the tribes that had been promised sovereignty. That is why they’d fought the Ottomans and sided with the allies: to be rid of their masters, not to swap them for some new ones. When the tax goes unpaid, the aerial bombardment of villages starts.

Gertrude Bell writes home, distraught, already blaming the curse it is that oil has been discovered in this land. Churchill had seen from the start of the war that oil independence for the empire would be the great strategic prize of the war as well as a tactical military requirement. There was never anything innocent in the War Office’s late recruitment of Bell to the Cairo office to work alongside TE Lawrence (who, in what is presumably for him the highest of compliments, writes of her that she is “not very like a woman”).

As the war and the aftermath of the Paris Peace 1919 gives way to the realpolitik of the grab for oil-rich Ottoman lands in the 1920s, she tries to warn that “no people likes permanently to be governed by another”.

Dutifully, she draws the boundaries of the new Kingdom of Iraq to balance Sunni and Shia numbers – “to avoid a theocratic state”. The Cairo Conference in 1921 set out to achieve this end and resulted in Feisal being given a Kingdom in Iraq and his brother the throne of neighboring Transjordan.

However in the end, she concludes that “making kings is too great a strain” because, we feel, she knows that Britain’s promises of sovereignty will be empty.

The talent and sympathy of the likes of Gertrude Bell don’t count for much against the onward march of power and the interests of those who wield it.

**Gertrude Bell is pictured centre at the Cairo Conference in 1921 with friend and colleague TE Lawrence, second right, and then Secretary of the Colonies Winston Churchill, where the future of the Middle East was discussed in the wake of the First World War and Paris Peace Conference in 1919

#gertrude bell#bell#quote#femme#middle east#politics#arabs#te lawrence#winston churchill#cairo conference#paris peace 1919#first world war#israel#palestine#history#britain#colonialism#icon

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The parliament of Transjordan made Abdullah I of Jordan their Emir on May 25, 1946.

Jordan’s Independence Day

Jordan’s Independence Day is celebrated on May 25 every year, and is the most important event in the history of Jordan, as it commemorates its independence from the British government. After World War I, the Hashemite Army of the Great Arab Revolt took over the area which is now Jordan. The Hashemites launched the revolt, led by Sharif Hussein, against the Ottoman Empire. The Allied forces, comprising Britain and France supported the Great Arab Revolt. Emir Abdullāh was the one who negotiated Jordan’s independence from the British. Though a treaty was signed on March 22, 1946, it was two years later when Jordan became fully independent. In March 1948, Jordan signed a new treaty in which all restrictions on sovereignty were removed to guarantee Jordan’s independence. Jordan joined and became a full member of the United Nations and the Arab League in December 1955.

History of Jordan Independence Day

The first appearance of fortified towns and urban centers in the land now known as Jordan was early in the Bronze Age (3600 to 1200 B.C.). Wadi Feynan then became a regional center for copper extraction with copper at the time, being largely exploited to facilitate the production of bronze. Trading, migration, and settlement of people in the Middle East peaked, thereby advancing and refining more and more civilizations. With time, villages in Transjordan began to expand rapidly in areas where water resources and agricultural land abound. Ancient Egyptians then later expanded towards the Levant and would eventually control both banks of the Jordan River.

There was a period of about 400 years during which Jordan was under the rule and influence of the Ottoman Empire, and the period was characterized by stagnation and retrogression to the detriment of the Jordanian people. The reign of the Ottoman Empire over Jordan would eventually cease when Sharif Hussein led the Hashemite Army in the Great Revolt against the Ottoman Empire, with the Allies of World War I supporting them. In September 1922, the Council of the League of Nations recognized Transjordan as a state under the terms of the Transjordan memorandum. Transjordan remained under British mandate until 1946, when a treaty was signed, with eventual sovereignty being granted upon signing a subsequent treaty in 1948.

The Hashemites’ assumption of power in the Jordan region came with numerous challenges. In 1921 and 1923, there were some rebellions in Kura which were suppressed by the Emir’s forces, with British support. Jordan is generally a peaceful region today, and it has become quite a tourist destination in recent times.

Jordan Independence Day timeline

3600 B.C. Earliest Known Jordanian Civilizations

Fortified towns and urban centers begin to spring up in the area now known as Jordan.

1922 Jordan is Recognized as a State

In 1922, the Council of the League of Nations recognizes Jordan as a state under the Transjordan memorandum.

1946 First Independence Treaty is Signed

In 1946, Emir Abdullāh negotiates the first independence treaty with Britain which would later lead to Jordan's ultimate independence in 1948.

1955 Jordan Joins the United Nations

Jordan becomes a member of the United Nations and the Arab League in 1955.

Jordan Independence Day FAQs

What day is Jordan’s Independence Day?

Jordan’s Independence Day is May 25, every year. It marks the anniversary of the treaty that gave Jordan her sovereignty.

When did Jordan become independent?

On May 25, 1948, Jordan officially became an independent state.

Who is Jordan’s current leader?

The current ruler Of Jordan is the monarch, Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein, King of Jordan.

How to Observe Jordan Independence Day

Light up some fireworks

Prepare some mansaf

Share on social media

One of the hallmark celebrations of any independence day is the show of fireworks. Be sure to be a part of the beauty!

As you probably already knew, Mansaf is Jordan’s national dish. As such, preparing it on such a special day as Independence Day is a brilliant idea.

Take pictures and videos of you in your dishdasha celebrating Independence Day. Share them on your social media!

5 Interesting Facts About Jordan

Home to the Dead Sea

A nexus between Africa, Europe, and Asia

Over 100,000 archeological sites

The world’s oldest dam

Jesus was baptized in Jordan

The Dead Sea, which is the lowest point on Earth, is located in Jordan.

Jordan is a pivotal point connecting Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Jordan has over 100,000 archeological and tourist sites.

Jordan is home to the world’s oldest dam, the Jawa Dam.

Jesus, who is the symbolic character of the Christian faith, was baptized in the Jordan River before beginning his ministry.

Why Jordan Independence Day is Important

Jordan is peaceful and liberal

The weather in Jordan is nice

Jordan is a tourist’s dream

Though a generally conservative country, Jordan is relatively liberal. The country is peaceful and tolerant of foreign cultures.

Jordan is a warm region. The weather is usually warm and pleasant at all times of the year.

Jordan has everything a tourist could dream of. Beautiful sights, calm weather, a welcoming culture, and amazing people make it a fantastic place for tourists.

Source

#Petra#Amman#Aqaba Fortress#Aqaba#Jerash#ruins#architecture#travel#archaeology#cityscape#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#summer 2007#Jordan#Asia#Middle East#Gadara#Dead Sea#Wadi Mujib#Wadi Rum#desert#Kerak Castle#Abdullah I of Jordan#Emir#25 May 1946#anniversary#Jordan history#vacation#Jordan’s Independence Day

1 note

·

View note

Text

Irredentism and the Middle East

With this letter, I would like to return to the topic of the two-state solution I broached a few weeks ago but still have more to say about.

To begin by stating the obvious, there is surely no axiom relating to the Middle East more often repeated and more fervently believed—if not quite by all than surely by most—than the one that supposes that peace in the Middle East will only come when some version of the United Nations’ original Partition Plan of 1947 is somehow put into place, yielding the desired—if long overdue—dismemberment of Mandatory Palestine into two states, one Jewish and one Arab. This truth is so often repeated, and in so many different quarters and by so many people from such different political camps and orientations, that it has acquired the feel of a basic truth, of being the kind of foundational idea that one can damn someone, and not faintly, merely by suggesting that he or she is only paying lip service to its reasonability but doesn’t really believe in it or think of it as the sole workable solution to what would otherwise be an insoluble problem. Actually to reject it as unworkable foolishness is, in at least most non-extremist quarter, unthinkable.

I’ve spoken about the two-state solution in public many times and always positively. But now that I force myself to revisit the basic concept and to consider the parts before coming to judgment regarding the whole, I find myself surprised by how many of the ideas that constitute those parts strike me as naïve, even utopian, when considered on their own.

There is, at any rate, something surreal about the whole discussion—the endless, ongoing, passionate discussion—regarding the two-state solution, and specifically because there actually are two states, one Jewish and one Arab, on the territory of Turkish Palestine. But, of course, even that assertion is complicated and depends, at least in part, on how one views the long-forgotten Transjordan Memorandum of 1922, the British proposal ratified by the League of Nations in September of that year that allowed for the dismemberment of Ottoman Palestine into two regions, both to be administered by the British: the part west of the Jordan to be called Palestine and the part to the east of the river to be called Transjordan. This would just be so much boring administrative history, except for the detail, made explicit in the memorandum, that the point of the proposal was specifically to prevent Jews from settling in Transjordan. Nor is this a point to gloss over lightly, because it was as a direct result of that dusty memorandum that the Partition Plan of 1947—the United Nations proposal that is the bedrock upon which the two-state solution rests—only ever applied to the lands west of the Jordan, the part that was called Mandatory Palestine. And so, because the land on the east side of the river was excluded not because of historical or geographical reasons but merely because the British perceived doing so to be in their own best interests and got the League of Nations to go along with the idea, today’s proponents of the two-state solution remain mostly unaware of the undeniable fact that there actually are two states, one Arab and one Jewish, on the territory that the world took from the Turks after the First World War and gave to the British to administer. That, however, is not what I want to write about today.

Nor do I want to focus on the obtuse unwillingness of so many who speak vocally about the two-state solution as the sole path forward to peace to take a long, hard look at Gaza…and then explain why Israel should not insist on ironclad guarantees that the citizens of some future state of Palestine will not follow the Gazans’ lead and give their nation over to radical terrorists whose whole raison d’être is the annihilation of the Jewish state. (For European nations like Ireland and Sweden that face no existential threats from without and whose right to live in peace on their own soil is contested by none to look past Gaza and pretend not to see the problem borders on the grotesque. But I’ll return to that set of ideas in a future letter.)

Instead, what I would like to bring to the discussion today are two ten-dollar words that denote related but distinct concepts, and which hardly ever appear in discussions of Middle Eastern politics: irredentism and revanchism. The former, irredentism, denotes any popular movement rooted in the desire to reclaim “lost” territory that the proponents of the movement consider rightfully theirs. (The word derives from the Italian word irridento, which means “unredeemed” and was coined in the 1870s by activists who wished to “redeem” the Italian-speaking parts of Austria and France by making them part of Italy.) The latter, revanchism, denotes any political movement rooted in the desire to reverse territorial losses incurred through war or through some other political process, and to restore them to their original political status. (The word derives from the French word revanche, which means “revenge” and was coined by French nationalists who wanted to reclaim Alsace-Lorraine from Germany after losing those two eastern provinces in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871.) The Palestinian cause has elements of both, of course: the “redemption” of Arab land that somehow ended up as part of Israel and “revenge” both for the defeat in 1948-1949 that established Israel as an independent country and left the West Bank in the hands of Jordan and Gaza under Egyptian control, and also for the Arab defeat in the Six Day War that left the West Bank, the Golan, the Sinai, and Gaza under Israeli control.

Viewing the struggle for an independent Palestinian state through the lenses of irredentism and revanchism is an interesting experience, because it allows us to view the whole situation through a much wider lens than usual. The irredentist and/or revanchist claims of nations are, it turns out, countless. But the world takes little note of most of them: the principle that law most reasonably derives from facts on the ground—in the Latin of international law: ex factis jus oritur—is broadly brought to bear to dismiss most irredentist claims as nationalistic fantasies that cannot be expected to trump the actual boundaries of existent nations. No one, for example, is prepared to take South Tyrol from Italy and hand it over to Austria merely because there are Austrians who haven’t made peace with its loss following World War II. Nor is the world going to dismember the United Kingdom and hand North Ireland over to Ireland merely because a large majority of Irish citizens think of it as an integral part of their island-nation, which it surely is geographically, and because its citizens are almost exclusively ethnically Irish. Nor did the world seek to head off the first Gulf War merely by handing over Kuwait to the Iraqis who claimed it as their own territory merely because the boundary between the two nations was yet another British line arbitrary drawn, this time literally, in the sand…much less because Saddam Hussein threatened war if they didn’t. European nations alone with irredentist claims on other countries’ territory include, aside from Austria and Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Hungary, Romania, Croatia, Servia, Bosnia, Albania, Bulgaria, Germany, Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Norway, Russia. Asian nations with irredentist claims on other countries include India, Japan, China, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Cambodia, and the Philippines. The list goes on. (For a full list, click here.) Indeed, as I reviewed these claims and was amazed not only at how many they are, but at how many different nations they involve, it struck me that the assumption so many of us seem to have that the mere fact of the Israeli victory in the Six-Day War implies some sort of obligation on Israel’s part to hand over land it has administered for half a century seems weak and not at all in conformity with the way the world views other similar disputes regarding territories lost in war or as a result of political adventurism abroad.

There is a counterpart to the principle of ex factis jus oritur mentioned above: it is ex injuria jus non oritur, which means that, for all law must and should rest on a foundation of reality, “unjust acts cannot create law.” That suggests a certain unsavory underside to the argument that Israel has some sort of unilateral obligation to create a Palestinian state on the West Bank when put forward by nations who themselves couldn’t be less interested in creating “two-state solutions” in response to irredentist claims on their own territorial integrity. (Just for fun, try suggesting to an Australian that Australia solve its aboriginal problem with a two-state solution…or to a New Zealander that New Zealand solve its Maori problem by divvying up the landmass so that the descendants of the nation’s colonial invaders and those of the natives they found in place can thrive in separate political entities.) Indeed, the supposition that Israel’s existence itself is a kind of unjust act perpetrated by the world on the Palestinians, an argument that has neither historical validity nor philosophical merit, would justify the assumption that Israel must cede land it won in a war foisted upon it by its enemies. But that argument—that Israel is itself an unjustifiable aberration the existence of which cannot be used as the basis to create law at all—is not only offensive, but suggestive of a deeply anti-Semitic worldview.

I am not arguing that the Palestinians should be made to pay forever for their huge error of judgment in 1947 when the world offered them an independent state and they specifically chose not to take it because taking it would have meant living in peace with the Jewish state next door. But the assumption that the facts on the ground cannot and should not create the law that governs the parties to the dispute can only be sustained by arguing the illegitimacy of the Jewish state…and that is a position that principled people possessed of an unbiased sense of history may never embrace.

A two-state solution may in the end be a good thing for all parties to the dispute. I actually think that that probably is the case. But to argue that it must be, that it is immoral and unreasonable for the Arab side to bear the consequences of their own defeat in war both in 1948 and in 1967—that is simply a principle of law that none of the nations of the world seems to apply to itself. And that point—and also that Israel has every right never to agree to any sort of agreement that could conceivably lead to the establishment of Gaza East on the West Bank—those are the points that seems regularly lost on most, including those who speak the most fervently in favor of the two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Balfour at 100

Last week, I wrote to you about the various issues I see hiding behind the assertion I hear made constantly that the only path forward to peace in the Middle East is the so-called two-state solution. Today I would like to go back even further in time than the Transjordan Memorandum of 1922 that I mentioned in passing last week, and consider the document upon which the two-state solution itself rests, the Balfour Declaration of 1917.

Nor is this just ancient history: as its one hundredth anniversary approaches this fall, the Declaration was suddenly back in the news last summer when the foreign minister of the Palestinian Authority, Riyad al-Malki, told Muslim leaders gathered in Mauritania that the Palestinians intend to sue the United Kingdom in international court to force it to rescind the Declaration and to indemnify those who suffered financial damage because of its promulgation. At first, this sounded more amusing than sinister, something like some white supremacist group suing the federal government to force them to void the Emancipation Declaration—or, even more amusingly, the Thirteenth Amendment—and indemnify all those poor slaveholders who suffered financial distress when their “property” was summarily taken from them. Or, even more to the point, like a teary nine-year-old with a skinned knee threatening to sue Sir Isaac Newton to compel him posthumously to withdraw the laws of gravity that drew him to the ground when he fell off his bicycle and hurt himself…without realizing that the laws of gravity are no more dependent on Sir Isaac than the inalienable right of the Jewish people to thrive as a free people in its own national home were dependent on Arthur James Balfour.

Clearly, the suit won’t go anywhere. It isn’t even obvious in what court such a case could, or would ever, be tried. But the Palestinian leadership was right about one thing, though: the Balfour Declaration—and all it implies—is in many ways at the heart of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

It would be easy to wave it away as nothing more than a late expression of British colonialist imperialism: if the British Empire could seriously talk about its “ownership” of countries all over the globe like India or Kenya to which it had no moral, legal, or historical claim without feeling foolish, so why should they have felt odd announcing that they look with favor on efforts to realize the nationalist ideals of the Jewish people in its own homeland as though this were a point in need of British endorsement? But, as usual, there is more here than meets the eye…and a reasonable case can be made that the Balfour Declaration retains, even a century later, its importance as an important stepping stone towards the eventual founding of the State of Israel.

Of all the world’s wars, World War I remains the most confusing for most of us. It appears not to have been fought over any serious issue. Its alliances seem more like arbitrary couplings of nations than the thoughtful affiliation of nations with similar ideals and agendas. The casualties were almost unbelievable—about 11 million military personnel and about 7 million civilians killed, another six million (soldiers and civilians) missing and presumed dead, and about 20 million (also a combined total of civilians and soldiers) wounded in some serious way. It ended, as everyone knows, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918, and was formally wrapped up (at least as far as our country was concerned) with the Treaty of Versailles in June of 1919. And then came the divvying up of the losers’ territory, both at home and overseas. Austro-Hungary was dismembered entirely. German overseas colonies like Tanganyika, Togoland, Namibia and Cameroon went to the British and the French. And the part of the Ottoman Empire that wasn’t Turkey itself was parceled out to the victor nations as well: France received League of Nations mandates to run Syria and Lebanon and the U.K. received mandates to run Iraq, Palestine, and Transjordan. It was all much more complicated than that…but the basic principle is that the Land of Israel, dominated by the Ottoman Turks since Selim the Grim defeated the Egyptian Mamelukes in 1516 and added Israel to his empire, was placed under the governance of the British.

An interesting question to ask is why the United States, which more than happily acquired bits and pieces of the Spanish Empire after winning the Spanish-American War in 1898, did not have any of the territories taken from the loser nations placed under its authority. That too is a complicated issue, but it mostly has to do with Woodrow Wilson, who had no interest in taking on the governance of foreign lands to which the United States had no moral or legal claim. This, of course, suited the other victor nations just fine!) And so the Brits came to Israel.

What exactly they thought they were getting themselves into, I have no idea. They knew plenty of the place, because they had participated in battles against the Turks in Palestine starting with the First Battle of Gaza in 1917 and continuing up until the final fall of Jerusalem to General Edmund Allenby in December of that same year. Or perhaps that’s exactly the point—because they had fought the Turks on the soil of the Land of Israel, they came away feeling entitled to add its territory, if not precisely to the empire as a colony, then at least to their in-those-days vast sphere of global influence as land under the legal stewardship of Great Britain. The locals were not consulted, not the Arab ones and surely not the Jewish ones.

Jewish immigration was well underway as the First World War was wrapping up—the so-called First Aliyah began as early as 1882 (in the wake of the anti-Semitic agitation that followed the assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881) and had melted seamlessly into the wave of immigration known as the Second Aliyah around 1904. Indeed, about 70,000 Jews came to Ottoman Palestine between the early 1870s and the end of the First World War. (Just as an aside, that figure can be very interestingly compared with the fact that about 2 million Jews left Eastern Europe during those same years; the rest, my ancestors among them, headed west, not east.) Added to that figure were, of course, the small number of Jewish souls who simply lived in Israel, whose families hadn’t ever fled, who didn’t need to realize their Zionist longing by immigrating to Palestine because they hadn’t ever lived elsewhere. And, of course, there were also the descendants of earlier waves of Jewish immigration—those who came with Rabbi Yehudah He-hasid in 1700, for example, or the thousands who came in the 1740s along with Rabbi Moshe Ḥayyim Luzzatto and Rabbi Ḥayyim ibn Attar. So the Jews of Ottoman, now British, Palestine were well established in their ancestral homeland as the First World War came to its eventual end and had no intention of renouncing their dream of an independent Jewish state in the Land of Israel.

There were, of course, also Arabs living in the land and they were actively hostile to the notion of a Jewish state. It was already clear in the 1920s that this was going to lead either to peaceful compromise or endless friction, and it was in the context of that morass of mutual mistrust and apprehensive suspicion that U.K. Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour sent his now-famous two-sentence letter to Walter Rothschild, the 2nd Baron Rothschild, on November 2, 1917. The letter read as follows:

His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

It was already a jam-packed month for the Brits. The Battle of Beersheva, in which the British eventually beat the Turks soundly, was still underway. The Battle of Mughar Ridge, victory in which was considered indispensable if the British were to fulfill their plan of seizing Jerusalem by year’s end, was about to begin. Clearly, the British felt that they needed the support of the yishuv more than they needed to worry about irritating the Arabs…and that, rather than a sudden surge of unprecedented philo-Semitism, was surely what motivated the British to make their unexpected “declaration” when they did. And that is exactly what did happen. The Jews of Turkish, soon to be British, Palestine were energized. They clearly understood that their future lay with the land passing from Turkish to British rule, which is why General Allenby was greeted by the Jews of Jerusalem as a conquering hero when he, combining the role of military hero with pilgrim, got off his horse and walked almost humbly on foot through the Jaffa Gate into the Old City on December 11, 1917. The Arab population, needless to say, was not at all pleased and saw the British move as a craven effort to win the support of Jewish residents as they attempted to secure Palestine for themselves in the post-war period. Craven, it surely was. (They have that part right.) But what if the British, acting wholly in their own best interests, also came down on the side of reasonableness and justice? Does one necessarily preclude the other?

It was a time of new ideas. As noted in passing above, President Wilson was personally responsible for insisting that the treaties that ended the First World War grant self-determination to the peoples of the losers’ empires rather than merely award new baubles to the victors’ own colonial holdings. His nation—our nation—wanted nothing of other people’s countries. But Wilson was thwarted in the end by allies who were prepared to concede the right of self-determination to the peoples of Europe, but not the Middle East or Africa. And it was thus as a kind of a compromise that the notion took hold that the territories of the vanquished should be awarded not as colonies to the victors, but as temporary mandates, in effect as trusteeships of the League of Nations, until the people of those places could be trained to govern themselves. Leaving aside the almost surreal paternalism, racism, and chauvinism hiding behind such an idea, the foundational idea—that nations have the right to govern themselves—is not only sound, but entirely so. And so the San Remo Conference of 1920 awarded the “mandate” to rule over Palestine to Britain. Two years later, the League formally included the Balfour Declaration in its formal vision for the future of Palestine, thus charging the British with working towards the creation of a Jewish homeland in the Land of Israel.

And so things worked out that Lord Balfour, with two brief sentences, altered the course of world history by indicating that his government would shoulder the burden of governance in Palestine until the Jews were deemed capable of governing themselves. Eventually, the League of Nations endorsed the notion that the Jewish people, like any people, is entitled to govern itself on its own land and in its own place. And this just and reasonable policy was eventually transmitted to the United Nations which, before it turned away from its own ideals and became a grotesque caricature of its former self, ended up promoting its own version of the two-state solution when it ordered that Palestine be partitioned into two states, one Arab and one Jewish. And that is how the two-state solution ultimately has its origin in the Balfour Declaration.

And then, less than two decades later, came the Shoah—the ultimate demonstration of the consequences of Jewish powerlessness in the world. The blood of the martyrs called out then and still calls out…inviting all who dare to ponder their fate and determine in its light whether or not the League of Nations was right in adopting the Balfour Declaration as the basis of its own policy with respect to Jewish self-governance in the Land of Israel. The Balfour Declaration was key in giving Zionism a respectable home among the political philosophies that the world brings to bear in determining which peoples’ right to self-govern are given international credence and which not. To imagine that the British weren’t acting in their own best interests would be naïve in the extreme. But, at least for once, their own best interests led them to help actualize the Jewish dream of a free Jewish state in the Land of Israel…and we should applaud, and not cynically, a remarkable and remarkably daring statement that, in a few lines, granted to the Jewish people the natural right of all peoples to chart their own future forward in their own place and according to their own lights.

#Balfour Declaration#San Remo Conference#Woodrow Wilson#Mandatory Palestine#Israel#Two-State Solution

0 notes