#stream ditto

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Dead Boy Detectives is a show that really makes me miss the 22 episode season orders of before streaming. I would have loved a dozen more monster of the week one offs from that show! The core four characters are fun and play off each other beautifully. I just wanted to marinate in it longer.

Plus a season finale after 22 episodes automatically feels so much grander than after 8. There is no good replacement for quality time with magical teens.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

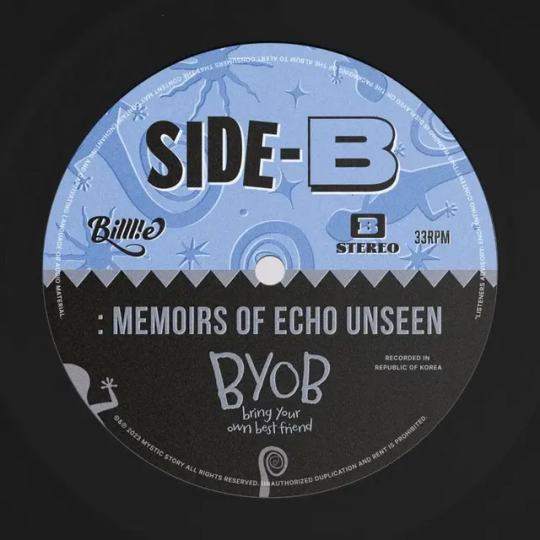

fave kpop singles (singles! Songs! not albums) of 2023 (not in order!)

newjeans - OMG, tripleS - girls capitalism, lucy - unbelievable, stray kids - super bowl, CSR - shining bright, stayc - teddy bear, newjeans - ETA, somi - fast forward, le sserafim - eve, psyche, & the bluebeard's wife, h1-key - rose blossom, zerobaseone - in bloom, stayc - bubble, fromis_9 - #menow, weeekly - good day, billlie - BYOB (bring your own best friend)

honorary mention (due to not being an actual promoted song):

youtube

#my SOTY was really ditto but it came out in december 22 so.#im late!! whateveeeerrr#music#I LOVE SWEET HAPPY VIBES want so bad fits right in... han jisung put that shit on streaming platforms RIGGHHT NNEOOOWWW#hyumlistens#Youtube#will list other faves in tags when i remember them....#odd eye circle air force one#zb1 melting point (the song)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

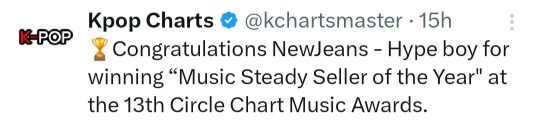

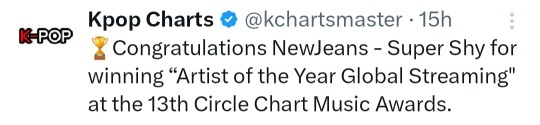

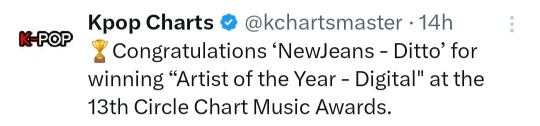

Congratulations to NewJeans for winning Music Steady Seller of the Year Award, Artist of the Year Global Streaming Award, and Artist Of The Year Award at the 13th Circle Chart Music Awards

#newjeans#circle chart music awards#hype boy#super shy#ditto#music steady seller of the year#artist of the year global streaming#artist of the year#nwjns updates#CONGRATULATIONS NEWJEANS

0 notes

Note

your blog is so pretty <333

omg thank you so much 🫶<33 your blog is cute as well

1 note

·

View note

Text

wholly to be a fool

genre/warnings/wc. fluff, gn!reader. food mention, unbeta'd. 0.6k. note. for @fxstpace, in response to mingyu + since feeling is first, by e.e. cummings (don't ask how food got in the picture). part of my 100 followers event !

Sunrise streams in from the windows, hitting the countertops of your apartment like honey, running over his knuckles and painting everything golden. The rice is hot—it stings his palms, paints them a splotchy pink, but it’s the only way to shape it well.

All that, though, is no matter. The door of his bedroom opens and there you are, unassuming in your devastation. There are spots of water on your—his—shirt, and a telltale dampness at the edges of your face that tells him you had just washed it. As you step forward, honey-gold sunlight glazes you too. Syrupy sweet, he thinks, even as his mouth is dry at the sight of bare legs and messy hair. You’re squinting as you lean over the countertop, the stool wobbling under the weight of your knee.

There is rice between his palms and Mingyu is watching you.

You meet his adoration with a grumpy, “Your side of the bed was cold.”

He has to remember to toss the rice a little, his palms cupping it, forming it into balls—jumeokbap, but with last night’s leftovers from recipe development mixed in. There’s carrots, spinach, and mushrooms, with some sesame seeds for good measure.

He also has to remember to unstick his tongue from the roof of his mouth.

“Sorry, baby.”

You pad forward, circling the kitchen island before your arms settle around his waist. The weight of your cheek burns through the thin cloth of his shirt. He can see, in his mind’s eye, the flutter of your eyelashes, the displeased downward curl of your mouth. He’s helpless to the smile that blooms on his face. He chuckles—giggles, really, as he twists around. “What’s gotten into you?”

Sure enough, there’s your eyelashes, fluttering, and the jut of your lip in an expression he never thought he’d see. His heart swells enough to rival the sunrise. “Just missed you.”

He melts, leaning against you, relishing in the way your bodies rest against each other. “You’re not getting rid of me, baby,” realizing even as he says it that perhaps it was not the best thing to begin the day with. He leans against you even more, all quiet reassurance even as you stiffen in your embrace of him. He feels the regret in your posture—past wrongs that prompt guilt to grate through this slowly blossoming new life.

Mingyu clasps your arms, still wrapped around his waist, waiting until you relax again. Unable to resist, he darts his head forward, kissing the tip of your nose, smile turning brighter at the way you scrunch your face. He does it again for good measure, hoping that you understand that his words held no malice, only silent apologies and earnest promise. You accept his kisses obediently, the little breath of laughter that dances across his skin prompting only more ardent affection.

“Ditto,” you eventually grumble, drawing away from his lips to press your face against his back.

Mingyu coos, affection bursting like a bud breaking the soil. You hush him, digging your face into more insistently, as though you could burrow into him. “The rice will get cold,” you mutter, muffled into his shirt.

“Help me?” He juts his chin to the sink. You’re off him more quickly than he would have liked, but then you’re beside him, hands freshly washed but still damp so as to prevent the rice from sticking. Mingyu hands you the paddle, and you scoop rice onto your waiting palm before beginning to mold.

He can’t help but giggle, again, and you hip-check him even as a matching quiet chuckle escapes you. It’s not quite golden hour anymore, the sunlight settling into its more neutral color, but the morning is no less sweet.

What a fool Mingyu would make himself for you. Even if he tried to write—if his tongue were employed in ways other than tasting—he’s sure that there would be no words for this, no articulation that could limn the joy of mornings with the love of his life.

note. likely an outtake from cooking with chopin (first it was reviving an old draft, now it's making me write a scene for a fic i havent even started on yet ASJAHSAHA aspen your power)

#mingyu x reader#kim mingyu x reader#mingyu fluff#kim mingyu fluff#mingyu imagines#kim mingyu imagines#seventeen fluff#seventeen imagines#seventeen fanfiction#.dive site#heartepub100

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

the water spits and chokes out of the cracked pipe, cold as hell, slapping rick square in the chest. he jerks back, teeth clicking. “shit—gotdamn—that’s cold.”

you’re doubled over laughing, one hand clutching your side, the other yanking your t-shirt off over your head. “what’d you think was gonna happen, cowboy? hot springs?”

rick grins, lazy and crooked, eyes sliding down your body like he’s starving. “could’ve warned me first, darlin’.”

you step in under the spray without flinching, water bouncing off your skin in sharp little bursts. your nipples pebble instantly, goosebumps racing across your arms, but you just throw your arms out and spin under it, giggling.

rick watches you like you’re the last miracle on earth, muttering under his breath, he strips the rest of the way, boots thudding against the rotten wood floor. you catch a flash of him, hardening already, and your belly flips.

“come on, grimes, don't be a pussy.” you tilt your head, taunting, water running down your hair in messy streams.

he steps in, swearing again when the water hits him, and you grab him by the waist, dragging him close, bare skin sliding on bare skin, hot against freezing.

he laughs into your neck, breath shuddering, body already shaking with the cold. “jesus christ, you’re evil.”

“you love it,” you giggle, mouth brushing his ear.

his hands find your ass, squeezing tight, lifting you against him like you weigh nothing. you yelp, legs wrapping around his hips instinctively. he stumbles, nearly slipping on the slick floorboards, catching himself against the moldy tile with a thud.

“fuck—” he snorts, forehead pressed to yours, hair dripping, “gonna break my gotdamn neck tryin’ to fuck you in a damn shower stall.”

you’re laughing so hard you can barely breathe, clinging to him, cold water pounding down. his cock presses thick against your belly, twitching when you grind against him, teasing. the sound that rumbles out of his chest isn’t a laugh anymore—more a low, desperate groan.

“rick,” you whisper, hips rolling slow. he kisses you like he’s starving, wet mouths slipping, biting, all teeth and need. your fingers rake through his soaked hair, tugging, and he hisses against your lips.

“God, you drive me crazy,” he breathes, nipping at your throat.

"ditto."

special tags: @wintfleur @bluemerakis @rositaslabyrinth

#soul’sscribbles𑁍#rick grimes#rick grimes x reader#rick grimes x you#rick grimes x y/n#rick grimes x oc#rick grimes fanfiction#rick grimes smut#the walking dead#twd rick#twd x reader#twd fanfiction#twdedit

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alrighty, quick question : I want to try and plan things ahead if weekend streams are gonna become an actual thing. I've been really enjoying doing them and getting to interact with you all, and I want to try and make it a weekly thing and keep up at it, but I need to know what's the best time for you peeps that are interested in watching so I can plan everything accordingly.

For my fellow European folks : I don't stream earlier due to having dinner usually quite late during the week, though there's a chance it might change soon! I can't say much yet but I'll post an update depending on how things go. I also don't stream earlier because I'll either have school or I want to have the full day to do everyday life things :00

PS : I'd rather focus on weekend days instead of week days because ✨school✨. So while Sunday is a weekend day, I'd rather avoid doing streams during that day unless there's a specific situation going on (like no classes on Monday or smth like that).

#ramble#felt like this could be a good way to plan things ahead before this weekend's stream#I've noticed Friday seemed like a good time but I'd rather be sure before I do anything :')))#especially if these are bound to become actually regular

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Audio has been a solved issue for decades. I own a 1976 Sony TA-3650 amplifier. It's a powerful class-A solid state amplifier with very low (under 0.1%) distortion while pushing 55w per channel. It's great. I have absolutely no need to upgrade, my turntable (also a vintage mid-70s Sony model) sounds great hooked in through it, and it has an aux channel so I can hook up a CD player or my old DAP for streaming my music collection. If anything, it's maybe a little too powerful. When the -20dB switch isn't engaged it gets apartment shaking loud with the volume knob barely turned up. It's also so goddamn heavy that when I needed to have it serviced it was too unwieldy to lug around on public transit so I had to hail a cab. It's power inefficient, and it's massive. A modern class-D amplifier does everything my Sony does in a package that is a fifth the size and a tenth the weight. That modern amp is also much less expensive. In 1976 the Sony TA-3650 retailed for the equivalent of $2750 in today's dollars. You can get a fantastic, audiophile grade Fosi phono preamp and amplifier pair for around $300.

Speakers are a solved issue too, with DSP it's trivial to tune the tweeters and woofers to have fantastic crossover. This used to be exceptionally difficult to achieve and had to be done via a complex series of transistors and circuits and careful part selection. Woofers are better, tweeters are better, materials science has come a long way. As soon as you leave the "shitty wireless Bluetooth speaker" tier of the market it's easy to find stuff that sounds good. Look up a few YouTube reviews for the pair of "budget" speakers I use as my desktop monitors, the Edifier r1700s. People rave about just how good these things are (and not "fantastic for the price" but "fantastic period") and they cost less than $200. Ditto for headphones, if you really want to spend the money buy a pair of Sennheiser HD 650s for $600, treat them well, and never buy another pair of headphones again in your life. I don't like open-back headphones though, so I'll stick with the excellent Shure SRH-840As (which are $400 cheaper to boot). And meanwhile in IEM land, you can get really fuckin' good IEMs for $30 from one of the Chi-fi manufacturers. The 7hz Zero2s are exceptionally good, well tuned, single driver IEMs that retail for around $30. I bought Cate a pair and she loves them. I just wish they'd stop putting waifus on their packaging.

The guys who spend thousands and thousands of dollars on audio equipment that costs less than the equipment used to record the music they're listening to are genuinely the dumbest motherfuckers on the planet.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Death and Identity in Post-postmodern Mystery

This essay contains spoilers for the entirety of Umineko When They Cry and spoilers for up to Chapter 140 of The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere.

Near the end of the first half of Umineko When They Cry, a bizarre curveball is tossed into the logic duel between Battler and Beatrice. Beatrice claims that Battler is somehow not actually Battler, but rather an imposter, a body double brought to the island as part of a plot to seize the inheritance. Thus, Battler is unqualified to be her opponent, meaning he must be expelled from the metafictional realm where the game takes place, and the game itself must be cancelled.

Battler, stumped by her logic, cannot form a rebuttal. He disappears, his very existence denied. "Without the one pillar that established his soul," the story reads, "he had fallen into the very depths of darkness, and had been drifting about all this time."

In The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere, a parallel moment occurs at the climax of the story's first half. The protagonist, Utsushikome of Fusai, confronts the person she believes to be the murderer, someone she knew when she was young. Cornered, he attempts to appeal to their childhood friendship, indicating he had even been in love with her. Utsushikome of Fusai cuts him off coldly, saying:

"I'm not Utsushikome of Fusai."

She then bludgeons him to death with a blunt instrument, committing a murder for which the reader immediately and unambiguously knows the culprit.

Identity is the fundamental question of even the most basic mystery novel. What is the identity of the culprit? Which character, seemingly a functional member of society, is actually a murderous villain?

As the genre has developed in complexity, this question has only become more prominent. Red herrings designed to throw off genre-savvy readers necessitate many non-culprits to also lead double lives or conceal key components of their identities. Inverted mysteries, where the culprit is revealed to the reader right away, emphasize the duality of the culprit's public persona and their murderous secret: Columbo's villains are exclusively elite, wealthy, and cultured, and Light Yagami is the seeming portrait of a model Japanese youth. Even House MD, a mystery story where "diseases are the suspects," predicates its drama on the fact that the diseased victim is concealing a double identity; in House's words, "Everyone lies."

Meanwhile, the mystery genre blurs the line between art and game. A proper mystery, as genre purists will tell you, must be solvable, must be fair, must follow certain "rules." If the culprit turns out to be a character who had not appeared in the story prior to their reveal, then the parameters of the game were broken, the reader had no chance. Ditto for the implementation of fanciful poisons or contraptions, secret twins, hidden passages, and so forth. These rules are in service of preserving the phenomenological experience of reading a mystery; like a game, the value of the work is expressed through the reader's attempts to interpret it, rather than its existence as a static artistic monument.

Yet, the genre has long been entangled with literary art. Mystery's foundation lies with authors like Edgar Allan Poe and Wilkie Collins, placing it as an outgrowth of the romantic and realist literary epochs. But between 1880 and 1930—the peak of literature as mass market entertainment, before film slowly usurped it—from when Sherlock Holmes popularized the genre until the so-called Golden Age of Detective Fiction, mystery became its "own thing," and in being its "own thing" suddenly resisted the artistic spirit of its time, whatever that time might be. The Golden Age coincides temporally with the height of modernist fiction, and yet none of the stream of consciousness or abstraction that defines the latter seeps into the former whatsoever. In the post-WWII postmodern era, when literature increasingly rejected the concept of objective truth altogether, detective fiction (both in literature and in new, televised forms) continued to doggedly assert the objective truth of the culprit's identity, the objective solvability of the crime.

A lot of this discrepancy has to do with the general schism between "art" and "entertainment" that arose in literature between the late 1800s and early 1900s. As the modernists ventured in more experimental directions, a newly literate and growing middle class continued to clamor for works that were more relatable to their pragmatic, dollars-and-cents sensibilities. (I often talk about "modernism" and "postmodernism" as these all-encompassing artistic zeitgeists, but the truth is that literary realism has never fallen out of vogue with mass audiences, and even in the 1920s a realist social satirist like Sinclair Lewis—not to mention twenty names you've never heard of writing at a similar bent—sold more than Hemingway and Faulkner combined.)

By entrenching itself within the "entertainment" sphere, and by continually defining itself against itself (the process by which "genre" is created), mystery fiction was able to develop independently of the overall artistic milieu and maintain a faith in objective reality even as that became an increasingly untenable position elsewhere. And it's what makes post-postmodern mystery fiction like Umineko and The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere so fascinating to me.

Umineko didn't emerge in a vacuum. It extends from Japan's dedicated mystery subculture, and I've heard that it shares many similarities with The Decagon House Murders, a 1987 novel by Yukito Ayatsuji. Japan has its own unique relationship with postmodernism as a literary movement, with it being more of a clearly-defined artistic fad that reached prominence in the 1980s specifically, compared to the West where postmodernism seems to be the nightmare of a post-WWII world from which we cannot awaken. I wish I had more familiarity with the Japanese mystery subculture to more authoritatively speak on this subject, but I do know that it, like the West, still believes strongly in the solvability of its mysteries. I described Japan as having a "postmodern" mystery scene, but that's not what Japan calls it. In Japan, the term for a solvable, "fair play" mystery is honkaku, meaning "orthodox"—or, roughly equivalent, "classical." And beginning with The Decagon House Murders, Japanese mystery entered a new era, shin-honkaku—neoclassical.

These terms are a perfect fit. In the West, the classical is associated with the Renaissance, and indicates a focus on mathematical precision in service of the objective truth associated with God. (The golden ratio, after all, is called divina proportione in Italian—divine proportion.) The precise, solvable logic of a classical murder mystery fits within this framework, and the neoclassical mystery retains its core beliefs, much as how Napoleon Bonaparte wielded neoclassicism to lend divine legitimacy to his rule. Despite the increased complexity and metatextuality of shin-honkaku mysteries, there remains that belief in objective truth.

Umineko does not believe in objective truth.

Umineko, as a mystery, is fucking bullshit. Solving it relies on so many unspoken metafictional conceits, and even if you do "solve" it, it turns out that the culprit of the first half of the story isn't even the """real""" culprit, because the first half of the story was actually just in-universe murdersona fanfic and the actual """""truth""""" of what happened on the island is completely irrelevant to most of the mysteries with which the reader is presented.

And that's under the assumption that Umineko actually tells you who the """""""real""""""" culprit is, because it doesn't, unless you read the manga, where it was thrown in as a bone to an absolutely incensed fanbase. Umineko was not popular with the Japanese mystery crowd, which makes sense, because they get pretty directly and brutally lampooned. This is a story where a detective quoting Hercule Poirot gets introduced halfway into the story and is an unequivocal villain (she calls herself an "intellectual rapist"), with the heroes fighting to conceal the truth from her.

No, Umineko does not believe in objective truth. It might believe it exists, in some abstract way, but it does not believe it matters, compared to the magic of subjective reality. About 90 percent of Umineko (honestly a lowball estimate) depicts stuff that didn't really happen. Sometimes it depicts stuff that didn't really happen within the subjective reality of a fanfic that itself didn't really happen. Even most flashbacks set before the mystery or flash forwards set after are mired in unreality.

No, what Umineko believes in is emotional truth, subjective truth. The story's key phrase is "Without love it cannot be seen," referring to how biases (love) influence one's understanding of reality. The "Red Truth," objectively correct statements, are depicted as painful and punishing, or spiderwebs that ensnare helpless victims. It is in the space between what is known objectively where magic is allowed to exist, where interpretation can supersede fact, and where true emotional catharsis can be reached.

As such, it is the antithesis to the mystery genre.

It's also the antithesis of postmodernism. Not rejecting it, in an impossible attempt to return to some pre-modern understanding of the world; no, Umineko agrees with postmodern thought on the subjectivity of our reality. Where it diverges is in the interpretation of that subjectivity, seeing in it not the cynical nihilism postmodernism quickly (perhaps from the onset) devolved into, but a new method of reaching emotional and intellectual fulfillment.

This, to me, is what the post-postmodern artistic zeitgeist has increasingly turned toward. Works that recognize the information-dense, ungraspable reality of the post-internet age, but seek and ultimately find emotional catharsis within it. Everything Everywhere All at Once, Spider-verse and unlimited lesser multiverse stories, Homestuck, even the origin point of the literary mode Infinite Jest all operate within this theme.

Where Umineko seeks its catharsis is in identity. While the central "game" of the mystery, sometimes literalized as a chess match between Battler and Beatrice, initially appears to be Battler's attempt to discern the true culprit in classical mystery fashion, from Beatrice's perspective the game is an attempt to assert and confirm the existence of her identity altogether.

In "reality," Beatrice the Golden Witch "does not exist." There is no magical being haunting the island. Beatrice is an identity invented by another character in an attempt to generate meaning for their life. And that meaning is, fundamentally, important, perhaps more important than the objective facts that deny her existence. Which is why, as the story continues, Battler switches to Beatrice's side and defends her existence from a slate of cackling ghouls dredged out of the annals of classical mystery, who sling the "rules" of classical mystery about like weapons to maim and kill. Objectivity is the enemy, the Red Truth is a prison, but it cannot cover everything and in the mercy of subjective reality, a different sort of "truth" can be allowed to live. As the story goes on, it becomes increasingly clear that this "truth" is everything. Umineko never explicitly reveals the true killer on Rokkenjima, though mostly only through technicality. That's fine. Even by technicality, subjectivity can be allowed to live. Beatrice's identity remains.

Return to that moment I described at the start of this essay, where Beatrice briefly denies Battler's identity. In the overall narrative of Umineko, it winds up being an almost entirely inconsequential scene. Shortly after Battler disappears, his sister Ange asserts that even if Battler was not born to Asumu, he is still Kinzo's grandson, meaning he is a true heir to the Ushiromiya family and thus qualified to be Beatrice's opponent. Battler returns and the status quo is swiftly reestablished.

What is the purpose of this scene, then? In character, it makes sense as a play for Beatrice to make. Her own identity has been constantly under assault from Battler, most recently—and most painfully, for her—when Battler forgot an important promise he once made to her. She is giving him his own medicine as revenge. But it's a very dramatic and extreme turn for something so petty. The scene does establish that Battler was not actually born to the woman he believed to be his mother (Asumu), but what does this mean for the story itself?

Beatrice's claim stems from a convoluted baby swapping plot that is revealed much later in Umineko. It turns out that Rudolf had a child with both Asumu and his mistress Kyrie at the same time, and Asumu's child, the "real" Battler, died immediately, so Kyrie's child was renamed Battler and substituted for the real thing. Both children were Rudolf's son, and thus Kinzo's grandson, and all of this really has nothing to do with anything else going on in Umineko's mystery, and is kind of pointless. (It does suggest Battler as a red herring identity for the mysterious baby Kinzo tries to foist onto Natsuhi in Umineko's fifth episode, but as far as red herrings go, it's a lot of legwork for not much deception.)

I've always been fascinated, though, by what it would mean if Beatrice's claim were true. Not just that Battler wasn't Asumu's son, but that he was not related to the Ushiromiya family at all. There's some fairly compelling evidence in its favor. It's stated early on that Battler, at age 12, became angry when his father married Kyrie shortly after Asumu's death, and estranged himself from the family for six years. His appearance at the family conference where most of Umineko takes place is the first time anyone in the family has seen him since, and almost everyone is surprised by the physical transformation Battler has undergone, particularly remarking on how incredibly tall he is. Near the end of Umineko, when it is suggested that Rudolf and Kyrie are the mystery's "true" culprits, the idea that they brought in some yakuza thug to pose as Battler and help them murder everyone becomes compelling.

But that's just the practical aspect of the mystery. What about the story itself? What would it mean for the ultimate moment of emotional catharsis at the end of the narrative, when Ange—dying of cancer—finally reunites with her long lost brother, only to discover he isn't actually her brother at all?

Well, that's actually what happens at the end of Umineko. Not because Battler is a yakuza thug, though. It's because of yet another oddly-inserted plot element where Battler receives brain damage escaping the island and develops a dissociative identity disorder that causes him to view himself as Tohya Hachijo, an amnesiac author.

Though somewhat farfetched, this last-second development makes sense within Umineko's thematic framework, where identity—and the capacity for people to inhabit multiple identities at once, either literally or through the subjective interpretations of the people around them—is one of the key drivers of the story's emotional core. For Ange, her brother is lost, and yet meeting Tohya is a moment of intense catharsis, because she is willing to believe in the redemptive magic of love and "see" a subjective truth more powerful than objective reality. After all, this meeting occurs in the "Treat" ending, and is placed in contrast to the "Trick" ending, where Ange instead embraces objective rationalism and deals with uncertainty by gunning down anyone who might possibly be a threat to her. (Which turns out to be every character in her immediate vicinity.)

I wonder how that Treat ending catharsis would read, though, if instead of the author Tohya Hachijo, who deals with his identity disorder by writing fictional accounts of the Rokkenjima massacre that, while not the literal truth, reach for a subjective or emotional truth, the version of her brother Ange met was Battler the yakuza thug, who was never her brother but a cheap imposter. It would probably undermine Umineko's entire message. It would at the very least make the Treat ending seem like a nasty trick in its own right. Or would Ange still be able to "see" an emotional truth even in this? Where does the line between subjective reality and pathetic delusion lie? What, exactly, would be the identity of the brain-damaged man she reunites with? What is the identity of the story's protagonist?

That's where The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere comes in. When its central mystery starts, a metafictional interlude occurs in which rules for solving the murder(s) are established. The first rule reads:

1. THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE PROTAGONIST IS ALWAYS TRUTHFUL

This rule, like many of the subsequent rules, is highly questionable. The story has already thrown into doubt who exactly the "protagonist" is. That seems like an odd thing to say, because the very first chapter, numbered 000, appears to make it explicitly clear:

"Understand this: Your role in the scenario has been elevated from that of bystander to that of the heroine, and your victory condition is thus," she continued. "You must ascertain the identity of your opponent, the cause of the bloodshed to follow, and prevent it before it comes to pass. In order to accomplish this goal, you must pay close heed to all which transpires, and use deduction, alongside your skills and past experience of the events to follow. Do you understand your role?" "Yes," I said, muted.

The issue is that whoever the perspective character is in 000, they are not the same person as the perspective character for the rest of the story. It eventually becomes clear that they share the same body, that they are both called Utsushikome of Fusai. Nonetheless, they are distinct identities. They have different memories, different motives, and different personalities. Much later, they even hold a conversation with one another in the same metafictional realm where the mystery's rules were outlined, a metafictional realm that turns out to not be metafictional at all.

Of course, neither of these Utsushikome of Fusais are actually Utsushikome of Fusai. They are gestalt personalities that combine the memories and personality of an original Utsushikome of Fusai with the memories and personality of an entirely different girl named Kuroka, and then after the two Utsushikome of Fusais diverged from one another for reasons that are, as of writing, not fully clear but potentially due to the accumulation of memory over a centuries-long time loop. This labyrinth of identity defines the story as much as its core mystery. As said mystery hurtles toward its climax, scenes in the present are intercut with flashbacks detailing how the current identity of Utsushikome of Fusai came to be. In the present mystery, there is no ultimate reveal of the culprit (one is proposed, but in fairly faulty fashion). In the past, though, the reveal of the truth of Utsushikome's identity is laid bare, brutally and explicitly, to the point that it consumes the main narrative, and culminates in the scene I described at the beginning of this essay, where the gestalt entity inhabiting Utsushikome's body discards her identity as Utsushikome and performs a brutal on-screen murder.

In doing so, the traditional climax of the mystery novel—the unmasking of the culprit—is reframed. It is the protagonist, not the culprit, who is "unmasked." Flower is, ostensibly, a time loop murder mystery (though only one loop is shown), and shortly after committing this murder, Utsushikome meets another character, who tells her that in 90 percent of loops, Utsushikome herself is the murderer. It's a claim that seems unbelievable, despite what just happened, based on the reader's knowledge of Utsushikome as a bumbling and indecisive girl who needed the most extreme circumstances to rouse herself to violence (an "anxious waif," as the author, Lurina, described her to me). It's a claim even Utsushikome meets with doubt. At the same time, how much does the reader really know about this character? How much does she know about herself? Throughout the story, her name is split into various nicknames: Utsu, Su, Shiko, each tied to a different part of her existence. The fragmentation of her name symbolizes the fragmentation of her psyche, and the version of her the reader follows—the ostensible "protagonist"—is Su, the smallest and most fragmentary scrap of her, the one most divorced from knowledge and understanding.

If Umineko exhibited faith in the magic of subjective interpretation, Flower provides a cynical counterpoint. Forget comprehending other people, or the confusion of your increasingly complex world. What if you cannot even comprehend yourself? What if, rather than the redemptive turn of Umineko's Treat ending, one looked inward and saw only greater incomprehensibility? In Beatrice, Umineko has its own character whose psyche fragmented into various constituent personalities, each with their own name and appearance. Yet Umineko posits a beauty in these personalities, and its protagonists fight for their right to exist in the face of crushing objective reality. For Utsushikome, her fragmented selves are base, ominous, potentially murderers, or indeed actually murderers—as even Su considers herself the murderer of the original Utsushikome. Her primary goal, more important to her than solving the mystery, is finding a way to undo the gestalt fusion that underlies her personality and restoring the original Utsushikome. Beatrice fights to justify her existence; Su fights to destroy it.

Postmodernism's focus on the subjectivity of individual experience quickly turned it toward cynicism, even nihilism, and the all-pervading "irony" that David Foster Wallace made his personal bugbear. One can only know their own experience of the world, not anyone else's, and the outside world is becoming increasingly complex, increasingly unfathomable, increasingly disorderly. Post-postmodernism was, from its inception, a deliberate turn away from that cynicism. A way of finding emotional catharsis even after logic dissolved. Umineko operates within this framework, while Flower goes in the opposite direction. The postmodernists were too optimistic. They at least believed in subjective truth. In the world of The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere, even that strip of reality is shredded.

Entropy features big in the postmodern landscape, brought to literary prominence by Thomas Pynchon, who studied engineering physics and often used mathematical motifs as analogies for social concepts. Flower, too, engages with the concept of entropy, or rather revolves around it. The central murder mystery is set at the sanctuary of an order of scientists dedicated to curing death, and the way they have sought to do so involves stealing a piece of an entropic god-entity and incarnating it in human form.

As such, Flower strongly ties the concept of death to the concept of entropy. I said before that identity is the fundamental question of even the most basic mystery novel, but the same could be said for death; you'd have to go back to The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins, or maybe mystery stories made for children, to find a mystery without murder. Van Dine's rules for mystery put it emphatically:

There simply must be a corpse in a detective novel, and the deader the corpse the better. No lesser crime than murder will suffice. Three hundred pages is far too much pother for a crime other than murder. After all, the reader's trouble and expenditure of energy must be rewarded.

I love this because it's such a cavalier treatment of death in narrative, as though death, rather than a tragedy, was simply a way to kickstart a plot—or a "reward" for the "expenditure of energy" (as though a reader's energy is finite, and always being entropically lost). Indeed, many of the Golden Age detectives who found themselves amid a new murder a month seemed to take a similarly detached tack toward the whole affair. Umineko lampoons this as well; its Hercule Poirot parody, when faced with a group of people playing dead, goes on a six-man mass decapitation spree just to ensure there really is a mystery to solve.

Flower philosophically confronts the question of death as early as Chapter 002, when fan favorite smarmy bitch Kamrusepa goads Su into an argument over the moral implications of curing death. Kamrusepa takes a rationalist, "anti-deathist" perspective, stating that not only is curing death a fundamentally good thing to do, but the most good thing that can be done; that curing death would not only be valuable in and of itself, but would also lead to the alleviation of every other social ill. Su is less sure. Certainly, a deathless world wouldn't be free of social strife. But there's also another argument she flirts with: Perhaps people, like Van Dine's readership, somehow need death to orient the meaning of their lives around.

Her thought process mirrors that of the mystery genre. If the genre has absolute faith in objective truth, it also has absolute faith in utter destruction. Crimes less than the complete annihilation of a thinking being will not suffice. In such a way, even the most orthodox or classical mysteries themselves have a drop of the postmodern in them, a faith in the incontrovertible necessity of entropic dissolution, though in the form of the human body rather than society or information. It's notable to me that, in contrast, Umineko posits a sort of immortality for its victims, alive in the "Golden Land" within the Treat ending despite the objective reality of their tragic deaths, or even alive within the metafictional conceit of the Rokkenjima game board, where if the players desire they can always open up the box, set the pieces aright, a play with these characters once more. Through its use of the time loop, Flower rejects this proposal; its characters are trapped in a game without end, and ultimately conspire to escape this hellish immortality they've wrought for themselves. (Remember also that Utsushikome's role as protagonist, explicated in 000, was not to solve a murder, but to prevent it, which she fails at utterly and quickly.)

The Flower That Blooms Nowhere is still ongoing, and many of its mysteries remain unresolved simply due to that fact. I've spoken extensively to the author, Lurina, and she assures me she is committed to the solvability of the mystery, which suggests that she intends to ultimately reveal the truths behind the murders and everything else. This essay isn't intended to be predictive of the story's future (which, as of the latest updates, is heading into some of the most exciting territory yet, with many meditations on death and identity that I would love to talk about in this essay but withheld because I know many readers aren't caught up), but rather an assessment of what currently stands. What I find most fascinating about Flower is how it rejects so many of the redemptive post-postmodern precepts that imbue Umineko, despite borrowing so much of its metatextual complexity, and without retreating into the classical or even postmodern, as would seem to be the only alternative. Instead, Flower's vivisection of identity and death within post-postmodern concepts strike me as a wholly new and unique artistic direction, and once more makes me excited for the growing avant garde to be found within web fiction.

#umineko#the flower that bloomed nowhere#tftbn#umineko no naku koro ni#umineko when they cry#mystery#postmodernism#post-postmodernism

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

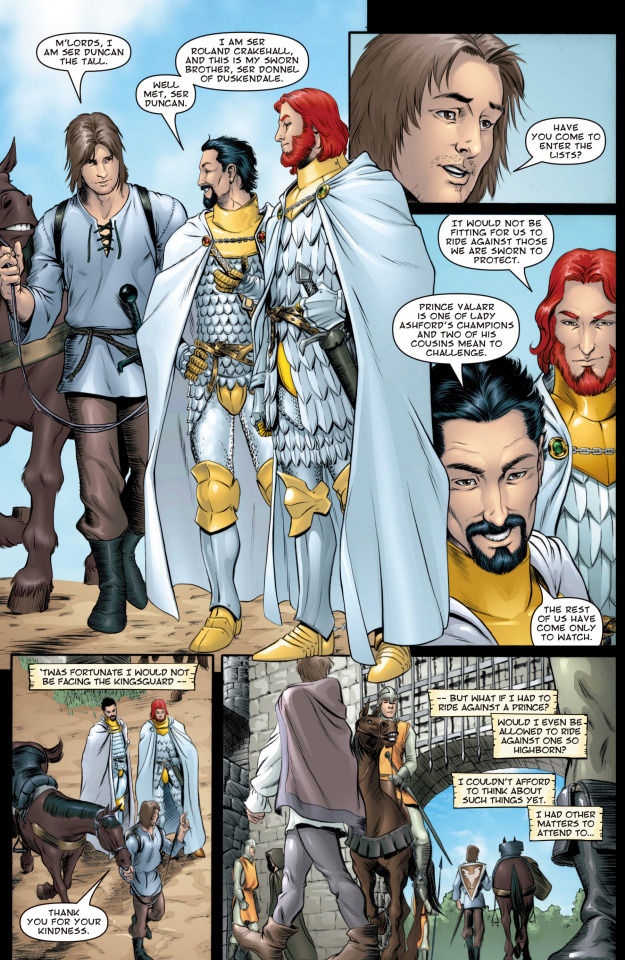

The Hedge Knight graphic novel - could it work as a roadmap for HBO's A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms?

So, per reports, HBO's Dunk & Egg show is going to be 6 episodes. I've seen several people saying that's too long, it should be 4 episodes at most, a 2 hour movie at most, there will be too much filler, blah blah blah. Well let me tell you, that's not true!

In 2003, The Hedge Knight was adapted as a 6 issue comic book (later collected as a graphic novel), and I think its script, each issue ending in a cliffhanger or dun-dun-dunnn moment, would work perfectly for the show, and is very probably how they'll do it.

Potential spoilers under the cut, but first - is this not perfect casting and costuming? It so is.

Like I said, I think each issue could be the plot of each episode. So I'm just going to summarize these issues, I hope you've read the GN or the novella. (If not, go read it, go read all of Dunk & Egg, it's so good.)

#1 - Dunk buries Ser Arlan, decides to go to Ashford for the tourney, meets Egg and a weird drunk guy at an inn on the way, gets to Ashford, sets up camp in the forest (bathes naked in a stream), goes to the tourney field and sees Tanselle performing her puppet show, gets measured for armor he can't quite afford, gets back to his camp to find the weird little bald kid making dinner.

#2 - Dunk agrees Egg can be his squire, that night he sees the falling star, next morning goes to Ashford castle and gets told he needs to prove he's a knight to enter the tourney (or that Arlan was, since he says Arlan knighted him), meets Aerion (badly) but also the Kingsguard, sells his horse for armor money, talks to Tanselle and meets the Fossoways, then meets up with the young Dondarrion lord whose dad Arlan worked for and relates the House Dondarrion origin story (imagine them telling that via puppet imagery, ooh), gets told "yeah knowing that is no proof you're a knight, sucks to be you".

#3 - Dunk goes back to the castle, stumbles into Baelor and Maekar arguing about M's missing kids, Baelor remembers his epic joust with Arlan so yay Dunk can be in the tourney, Dunk and Egg talk to Tanselle about painting him a shield, they watch the opening of the tourney (lots of jousting and pageantry including Lyonel "the Laughing Storm" Baratheon), and the first day ends after Aerion deliberately kills that horse.

#4 - Dunk argues with Egg over how much of a douche Aerion is, more flirting with Tanselle, gossip with Raymun Fossoway about the Targaryens, Egg runs in to say Aerion's hurting Tanselle, Dunk beats up Aerion and almost gets murdered by Aerion's goons, Egg reveals himself to save Dunk, Dunk in prison, talks to Egg and Baelor, Baelor tells him he can be mutilated for striking a prince or ask for trial by combat, so "how good a knight are you, truly?"

#5 - Aerion says sure, trial by combat, but only a trial of seven, Dunk has to find 6 guys, talks to Raymun and Steffon Fossoway, Daeron apologizes and tells Dunk his dragon dream, shield reveal, next morning the smallfolk are all "a knight who remembered his vows", various guys show up to help Dunk and Raymun gets knighted, but Steffon Fossoway goes to Aerion's side so they're still missing a guy, "are there no true knights among you?", wait is that Valarr??? no it's Baelor in Valarr's armor omg

#6 - The trial of seven. You know how this ends. 😭 Then talking to Maekar, and Dunk and Egg ride off into the sunset together.

I hope that's convincing enough for the doubters! I can see a few points where something might be shifted from the end of one to the beginning of the other -- but on the whole I think the comic is an excellent roadmap for the show, and I hope this is the way they lay it out. Also ftr, the Sworn Sword graphic novel was also originally 6 issues so possibly season 2 ditto (unless they add an episode for the in between THK-TSS Dorne and Oldtown adventures that didn't actually appear in the novellas, idk). But the Mystery Knight was only released as one book, so who knows, they might go for more episodes when they get to that season.

Also, re taking inspiration from the comic, I really hope they adapt the Kingsguards' gold codpieces. Just because.

#asoiaf#the hedge knight#a knight of the seven kingdoms#dunk and egg#akotsk#duncan the tall#aegon v targaryen#tanselle#daeron the drunken dreamer#aerion brightflame#baelor breakspear targaryen#maekar targaryen#raymun fossoway#steffon fossoway#lyonel baratheon#the ashford tourney#the trial of seven#asoiaf comics#akotsk spoilers#thk spoilers#serious serious spoilers - do *not* click if you don't want to know the story!#another in a series of fantasy booking adaptations lol

114 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ok: 10 years after the events of Deltarune headcanons (assuming all characters survive)?

Ditto Post-Pacifist route in Undertale?

I dunno if I can say much for Undertale post-pacifist because it seems like the post credits scene and the alarm clock dialogue all cover it pretty decently! Toriel's opened a school, Asgore seems content to just stick with his gardening, Alphys and Undyne get together, Sans and Papyrus seem happy to just be travelling around and exploring together. I do like going with the option that Frisk chose to become the ambassador and to stay with Toriel, and I like the idea that Sans got really into astronomy now that he's on the surface. It seems like they all still get together to hang out as a friend group/family for holidays and events in the alarm clock dialogue, so I like to think that that keeps up for years. I know it's easy to imagine things being really rocky for the monsters after being reintroduced to society, but I honestly just like the idea that things go smoother than expected, and while not perfect, everyone is just very content.

For Deltarune, hmm...while I feel like Kris and Noelle would be encouraged and expected to go to college, I'm not sure if Susie would be able to get in...and even if she did, if she would really enjoy an academic setting that much. Not sure if Kris and Noelle would go to the same college, or the same one Asriel is at! I think Susie and Noelle would get together, but it might be a tough few years if Noelle is in college and Susie's not there with her. But I can see Susie travelling around a lot, gaining a lot of hands-on experience doing odd jobs for people, and being seen as dependable in various circles, while stopping by the college to visit Noelle. By the time Noelle is out of college, Susie's amassed all these connections to basically do some real hands-on work with building or landscaping and such, and can support the two of them with that, so Noelle becomes a fantasy writer.

Kris isn't sure what they want to do at first, and they move back home after college for awhile helping around at the various businesses in Hometown, before eventually acting as Asriel's producer when he decides to actually finish and put out one of his video games. Turns out Kris does have a knack for coordinating people and good decision-making, and keeps doing this with various projects for Asriel and their other friends until they're pretty adept at it.

Berdly has pretty middling grades through college but gets really into streaming because he just likes to talk so much, and ends up doing decently for himself with that. Catti and Jockington get together, with Jockington becoming a minor league soccer player and Catti making some cash doing tarot readings. The whole gang see and hang out with each other and their families for holidays and especially for the Hometown festival every year.

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Show VS books - Theon's choice

So, I was hoping to post this for show VS books day and also to have time to rewatch the show to factcheck my impressions, which was not possible as my streaming service failed me, so I welcome any corrections about what I am writing. (Please no insults or like. Objections to the general concept of comparing an adaptation to its source material or of sharing critical thoughts about things you don't like. I think these are fine and fun things to do, if you disagree, just do not read this lenghty tome).

Still, I wanted to talk about the way Theon's choice between fighting with his family and remaining loyal to Robb is framed in the show, even before taking a very obvious Stark-goggles view the way it did in the following seasons. In my opinion, the show handled the ACOk storyline very movingly with great acting and some great writing, but still fell into the trap of conveying a certain amount of "shouldn't it be a no brainer to pick friend who values you over bio family that hates you?" in ways that in many cases weren't the writing's fault as it was impossible for a TV show to convey the same nuances as the book, but in some other cases might have been avoided. Here's how imho:

Theon swearing fealty to Robb explicitely, everyone's favorite bugbear. Not one I am particularly attached to, because really I think Theon's situation of being sent, while technically a hostage, to negotiate an alliance with his father and being refused remains legally ambiguous and kind of unprecedented whether or not he swears specific words of fealty. If he didn't swear it in the books, did he not effectively do it by arranging an alliance with Robb anyway, even though he couldn't know whether that alliance would really work out, meaning it was always a conditional loyalty? If he did, is it really binding/something he had a choice about? Still, it gives a very different impression to the casual viewer.

General less established worldbuilding on the taboo of kinslaying and taking arms against family which is just inherent to the medium of short-season TV show VS enciclopaedic saga and couldn't really be helped

Not seeing Theon's inner thoughts on the matter of family, another thing which can't be helped, which show his attitude as more nuanced as he's very aware and critical of the toxicity of his father and brothers but still has an expectation of being welcomed. Thus the hint that he remembers being loved and valued as a child even in a broken dysfunctional way and so reasonably expects to be again on his return

Ditto re: Theon's thoughts on the political situation of the islands which he does have an understanding of and feels a sense of duty to improve, mixed with the desire for glory and being a hero to his people

Starting with some things that can be helped: absolutely 0 sense of the Islands as being in a crisis, destroyed, in poverty, or being damaged by Robert and Ned's host or having somewhat substantiated desires of revenge, besides the deaths of Rodrik and Maron.

Actually expanding on this point bc the show chose to not get to any extent into what the relationship between Theon and his brothers was like. In the books, Theon remembers being abused by them and only expresses a desire of revenge when it helps justify himself to his family, developing a frequent theme in the books that vengeance is often very much not a simple and natural feeling but selfish and weaponized. The show understandably doesn't get into this sort of thematic/psychological analysis, so why not use the deaths of Theon's brothers as something that has a bit more weight in his choice? It was not difficult or time consuming to add some comment about their childhood or about mourning them etc, not as difficult as doing some of the other stuff I mention on this list lmao. It would have built more sympathy for him.

Theon is apparently getting no official welcome besides his sister's initiative to seduce him (Its possible Balon sent Yara and Yara independently decided to seduce him, but it meshes kind of weirdly with the way she lets Theon in on his own and then makes her cinematic entrance in the middle of the conversation) in the book, while Theon is unhappy with Aeron due to his desire to have his parents welcome him instead and Aeron's change and attitude to him, he's objectively a perfectly good person to send to fetch the heir, as a close family member and a priest with great authority and respect.

Theon has no one who loves him on the islands, no mother, no Dagmer, no childhood friends he finds he can't quite connect with again, no Wex, no men who choose to remain loyal to him at Winterfell. Wex is particularly interesting because, while some interpret the offering of a disabled bastard squire as a sign of the ironborn noble families's disdain for Theon, I think it's actually a fairly normal feudalistic exchange of favors. After all Theon is asked to take Wex on as a squire as payment for his horse, so certainly with the understanding he's doing the Botleys a solid by giving an opportunity to a boy who would otherwise not be allowed many, and Lord Botley later champions Theon's claim against Euron. So this little detail could have been a helpful shorthand for Theon succeeding in developing some kind of relationships and loyalty on the islands which he could think he might have developed if he had time and proved himself

Theon in the show is given a ship for his diversion raids while Yara gets 30 ships that appear to be the entire deployed force (??), which is a lot more extreme than "Victarion gets the whole fleet, Asha gets 30 ships, Theon gets 8". The book arrangement feels like an insult to Theon but is reasonable for someone who was never a captain before and who's unknown to his father. The show arrangement is a lot more of an open insult that doesn't really allow us to understand Theon's hope to improve his standing.

Probably couldn't have been helped, given the tight timeline of the show, but: book Theon gets a shining military success, though one of modest proportions in his victory against Benfred Tallart's sortie, before he undertakes the mission to Winterfell, which makes the plan seem somewhat less dumb. Also taking Winterfell being his own idea rather than it being pushed by show!Dagmer shouldn't have huge weight in this but it does make his choice seem more motivated (by his own rage and revenge, for his own political aims) and less pathetic

Moving the pivotal execution of ser Rodrik so early after Theon's taking of Winterfell undercuts the slow descent into despair and violence that Theon experiences in the books. We're supposed to think Theon made an irremediably wrong choice when he burned the letter to Robb, rather than having several chances to stop himself on the path to becoming a child murderer which he for various reasons doesn't take.

While Alfie and for once imho the writing as well do a great job of conveying Theon's pain and trauma for what he went through at Winterfell, it was evidently chosen not to focus or even explicitely mention outside the worldbuilding videos (iirc) how Ned would have been expected to execute him and his fear of that. Skipping the Beth parley is obviously a factor in this (which I will never understand, btw, it seems so perfectly made for TV...) , but even the very beautiful emotional moments that were scripted to replace it just focus on other things. The dialogue with Master Luwin for example has Theon associate fear with the walls of Winterfell, in a line so good I frequently forget it wasn't in the books, but still there's a writing choice to center a fear that comes from a sense of intimidation and inferiority towards the people who defeated his family rather than the material reality of being constantly up for execution. That completely recontextualises the situation and his relationship to house Stark

The matter of Theon's men loyalty to him deserves some expansion in general because like... GRRM, for all that we tease him for the "what was Aragorn's tax policy" line, does invest much time and attention in portraying in detail the choices of all his leader characters, their popularity and relationships with their followers. So even Theon whose leadership skills are not very important gets the sketch of a nuanced political situation. We know that Theon leads his men into several missions before Winterfell, that he's able to convince Dagmer to support his plan to take Winterfell and that his men follow him in this high-risk mission, that he punishes them for fighting over plunder and for committing rape, that he has some of them killed and that he executes Northmen to give them a semblance of justice and is haunted by both, that he doesn't feel like they would keep the secret of the murdered boys' identity, that they grow restless and ambivalent during their time in Winterfell but still do their duty, that one of them specifically takes issue morally with him using Beth against her father and wishes they could just have an open battle, that he offers them the chance to surrender rather than die with him and they are reluctant to refuse it but most do it. There was never going to be anything like that in the brief plotline of a minor character, obviously, but needing to simplify, was really "they knock him out and hand him over to the enemy" the best simplification? It was for the theme they wanted to convey, which is that there was a right and a wrong choice obvious from the start and that poor Theon, understandably and tragically, chose wrong.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm watching a dude stream trying to RNG manipulate for a shiny glitch mew using a method where he... switches a glitchy-nicknamed(?) eevee and a ditto's position in a PC box (among other things, there was a bad egg in his PC and I just jumped into the stream so I don't know all of what else he had to do to set it up)

...and goes and talks to a bookshelf and a mew appears and man I just love the fact that the old Mew under a truck myth is not true...

...because it's actually in a bookcase.

10 notes

·

View notes