#so you can be criminally convicted and have rape cases against you and be racist your whole life and STILL be president

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

absolutely devastated and embarrassed for those who voted for harris and for like you know. reason? logic? not a racist fascist! but the rest of you can choke !

#so you can be criminally convicted and have rape cases against you and be racist your whole life and STILL be president#cool cool cool#us elections

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because senator Kamala Harris is a prosecutor and I am a felon, I have been following her political rise, with the same focus that my younger son tracks Steph Curry threes. Before it was in vogue to criticize prosecutors, my friends and I were exchanging tales of being railroaded by them. Shackled in oversized green jail scrubs, I listened to a prosecutor in a Fairfax County, Va., courtroom tell a judge that in one night I’d single-handedly changed suburban shopping forever. Everything the prosecutor said I did was true — I carried a pistol, carjacked a man, tried to rob two women. “He needs a long penitentiary sentence,” the prosecutor told the judge. I faced life in prison for carjacking the man. I pleaded guilty to that, to having a gun, to an attempted robbery. I was 16 years old. The old heads in prison would call me lucky for walking away with only a nine-year sentence.

I’d been locked up for about 15 months when I entered Virginia’s Southampton Correctional Center in 1998, the year I should have graduated from high school. In that prison, there were probably about a dozen other teenagers. Most of us had lengthy sentences — 30, 40, 50 years — all for violent felonies. Public talk of mass incarceration has centered on the war on drugs, wrongful convictions and Kafkaesque sentences for nonviolent charges, while circumventing the robberies, home invasions, murders and rape cases that brought us to prison.

The most difficult discussion to have about criminal-justice reform has always been about violence and accountability. You could release everyone from prison who currently has a drug offense and the United States would still outpace nearly every other country when it comes to incarceration. According to the Prison Policy Institute, of the nearly 1.3 million people incarcerated in state prisons, 183,000 are incarcerated for murder; 17,000 for manslaughter; 165,000 for sexual assault; 169,000 for robbery; and 136,000 for assault. That’s more than half of the state prison population.

When Harris decided to run for president, I thought the country might take the opportunity to grapple with the injustice of mass incarceration in a way that didn’t lose sight of what violence, and the sorrow it creates, does to families and communities. Instead, many progressives tried to turn the basic fact of Harris’s profession into an indictment against her. Shorthand for her career became: “She’s a cop,” meaning, her allegiance was with a system that conspires, through prison and policing, to harm Black people in America.

In the past decade or so, we have certainly seen ample evidence of how corrupt the system can be: Michelle Alexander’s best-selling book, “The New Jim Crow,” which argues that the war on drugs marked the return of America’s racist system of segregation and legal discrimination; Ava DuVernay’s “When They See Us,” a series about the wrongful convictions of the Central Park Five, and her documentary “13th,” which delves into mass incarceration more broadly; and “Just Mercy,” a book by Bryan Stevenson, a public interest lawyer, that has also been made into a film, chronicling his pursuit of justice for a man on death row, who is eventually exonerated. All of these describe the destructive force of prosecutors, giving a lot of run to the belief that anyone who works within a system responsible for such carnage warrants public shame.

My mother had an experience that gave her a different perspective on prosecutors — though I didn’t know about it until I came home from prison on March 4, 2005, when I was 24. That day, she sat me down and said, “I need to tell you something.” We were in her bedroom in the townhouse in Suitland, Md., that had been my childhood home, where as a kid she’d call me to bring her a glass of water. I expected her to tell me that despite my years in prison, everything was good now. But instead she told me about something that happened nearly a decade earlier, just weeks after my arrest. She left for work before the sun rose, as she always did, heading to the federal agency that had employed her my entire life. She stood at a bus stop 100 feet from my high school, awaiting the bus that would take her to the train that would take her to a stop near her job in the nation’s capital. But on that morning, a man yanked her into a secluded space, placed a gun to her head and raped her. When she could escape, she ran wildly into the 6 a.m. traffic.

My mother’s words turned me into a mumbling and incoherent mess, unable to grasp how this could have happened to her. I knew she kept this secret to protect me. I turned to Google and searched the word “rape” along with my hometown and was wrecked by the violence against women that I found. My mother told me her rapist was a Black man. And I thought he should spend the rest of his years staring at the pockmarked walls of prison cells that I knew so well.

The prosecutor’s job, unlike the defense attorney’s or judge’s, is to do justice. What does that mean when you are asked by some to dole out retribution measured in years served, but blamed by others for the damage incarceration can do? The outrage at this country’s criminal-justice system is loud today, but it hasn’t led us to develop better ways of confronting my mother’s world from nearly a quarter-century ago: weekends visiting her son in a prison in Virginia; weekdays attending the trial of the man who sexually assaulted her.

We said goodbye to my grandmother in the same Baptist church that, in June 2019, Senator Kamala Harris, still pursuing the Democratic nomination for president, went to give a major speech about why she became a prosecutor. I hadn’t been inside Brookland Baptist Church for a decade, and returning reminded me of Grandma Mary and the eight years of letters she mailed to me in prison. The occasion for Harris’s speech was the annual Freedom Fund dinner of the South Carolina State Conference of the N.A.A.C.P. The evening began with the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and at the opening chord nearly everyone in the room stood. There to write about the senator, I had been standing already and mouthed the words of the first verse before realizing I’d never sung any further.

Each table in the banquet hall was filled with folks dressed in their Sunday best. Servers brought plates of food and pitchers of iced tea to the tables. Nearly everyone was Black. The room was too loud for me to do more than crouch beside guests at their tables and scribble notes about why they attended. Speakers talked about the chapter’s long history in the civil rights movement. One called for the current generation of young rappers to tell a different story about sacrifice. The youngest speaker of the night said he just wanted to be safe. I didn’t hear anyone mention mass incarceration. And I knew in a different decade, my grandmother might have been in that audience, taking in the same arguments about personal agency and responsibility, all the while wondering why her grandbaby was still locked away. If Harris couldn’t persuade that audience that her experiences as a Black woman in America justified her decision to become a prosecutor, I knew there were few people in this country who could be moved.

Describing her upbringing in a family of civil rights activists, Harris argued that the ongoing struggle for equality needed to include both prosecuting criminal defendants who had victimized Black people and protecting the rights of Black criminal defendants. “I was cleareyed that prosecutors were largely not people who looked like me,” she said. This mattered for Harris because of the “prosecutors that refused to seat Black jurors, refused to prosecute lynchings, disproportionately condemned young Black men to death row and looked the other way in the face of police brutality.” When she became a prosecutor in 1990, she was one of only a handful of Black people in her office. When she was elected district attorney of San Francisco in 2003, she recalled, she was one of just three Black D.A.s nationwide. And when she was elected California attorney general in 2010, there were no other Black attorneys general in the country. At these words, the crowd around me clapped. “I knew the unilateral power that prosecutors had with the stroke of a pen to make a decision about someone else’s life or death,” she said.

Harris offered a pair of stories as evidence of the importance of a Black woman’s doing this work. Once, ear hustling, she listened to colleagues discussing ways to prove criminal defendants were gang-affiliated. If a racial-profiling manual existed, their signals would certainly be included: baggy pants, the place of arrest and the rap music blaring from vehicles. She said that she’d told her colleagues: “So, you know that neighborhood you were talking about? Well, I got family members and friends who live in that neighborhood. You know the way you were talking about how folks were dressed? Well, that’s actually stylish in my community.” She continued: “You know that music you were talking about? Well, I got a tape of that music in my car right now.”

The second example was about the mothers of murdered children. She told the audience about the women who had come to her office when she was San Francisco’s D.A. — women who wanted to speak with her, and her alone, about their sons. “The mothers came, I believe, because they knew I would see them,” Harris said. “And I mean literally see them. See their grief. See their anguish.” They complained to Harris that the police were not investigating. “My son is being treated like a statistic,” they would say. Everyone in that Southern Baptist church knew that the mothers and their dead sons were Black. Harris outlined the classic dilemma of Black people in this country: being simultaneously overpoliced and underprotected. Harris told the audience that all communities deserved to be safe.

Among the guests in the room that night whom I talked to, no one had an issue with her work as a prosecutor. A lot of them seemed to believe that only people doing dirt had issues with prosecutors. I thought of myself and my friends who have served long terms, knowing that in a way, Harris was talking about Black people’s needing protection from us — from the violence we perpetrated to earn those years in a series of cells.

Harris came up as a prosecutor in the 1990s, when both the political culture and popular culture were developing a story about crime and violence that made incarceration feel like a moral response. Back then, films by Black directors — “New Jack City,” “Menace II Society,” “Boyz n the Hood” — turned Black violence into a genre where murder and crack-dealing were as ever-present as Black fathers were absent. Those were the years when Representative Charlie Rangel, a Democrat, argued that “we should not allow people to distribute this poison without fear that they might be arrested” and “go to jail for the rest of their natural life.” Those were the years when President Clinton signed legislation that ended federal parole for people with three violent crime convictions and encouraged states to essentially eliminate parole; made it more difficult for defendants to challenge their convictions in court; and made it nearly impossible to challenge prison conditions.

Back then, it felt like I was just one of an entire generation of young Black men learning the logic of count time and lockdown. With me were Anthony Winn and Terell Kelly and a dozen others, all lost to prison during those years. Terell was sentenced to 33 years for murdering a man when he was 17 — a neighborhood beef turned deadly. Home from college for two weeks, a 19-year-old Anthony robbed four convenience stores — he’d been carrying a pistol during three. After he was sentenced by four judges, he had a total of 36 years.

Most of us came into those cells with trauma, having witnessed or experienced brutality before committing our own. Prison, a factory of violence and despair, introduced us to more of the same. And though there were organizations working to get rid of the death penalty, end mandatory minimums, bring back parole and even abolish prisons, there were few ways for us to know that they existed. We suffered. And we felt alone. Because of this, sometimes I reduce my friends’ stories to the cruelty of doing time. I forget that Terell and I walked prison yards as teenagers, discussing Malcolm X and searching for mentors in the men around us. I forget that Anthony and I talked about the poetry of Sonia Sanchez the way others praised DMX. He taught me the meaning of the word “patina” and introduced me to the music of Bill Withers. There were Luke and Fats; and Juvie, who could give you the sharpest edge-up in America with just a razor and comb.

When I left prison in 2005, they all had decades left. Then I went to law school and believed I owed it to them to work on their cases and help them get out. I’ve persuaded lawyers to represent friends pro bono. Put together parole packets — basically job applications for freedom: letters of recommendation and support from family and friends; copies of certificates attesting to vocational training; the record of college credits. We always return to the crimes to provide explanation and context. We argue that today each one little resembles the teenager who pulled a gun. And I write a letter — which is less from a lawyer and more from a man remembering what it means to want to go home to his mother. I write, struggling to condense decades of life in prison into a 10-page case for freedom. Then I find my way to the parole board’s office in Richmond, Va., and try to persuade the members to let my friends see a sunrise for the first time.

Juvie and Luke have made parole; Fats, represented by the Innocence Project at the University of Virginia School of Law, was granted a conditional pardon by Virginia’s governor, Ralph Northam. All three are home now, released just as a pandemic would come to threaten the lives of so many others still inside. Now free, they’ve sent me text messages with videos of themselves hugging their mothers for the first time in decades, casting fishing lines from boats drifting along rivers they didn’t expect to see again, enjoying a cold beer that isn’t contraband.

In February, after 25 years, Virginia passed a bill making people incarcerated for at least 20 years for crimes they committed before their 18th birthdays eligible for parole. Men who imagined they would die in prison now may see daylight. Terell will be eligible. These years later, he’s the mentor we searched for, helping to organize, from the inside, community events for children, and he’s spoken publicly about learning to view his crimes through the eyes of his victim’s family. My man Anthony was 19 when he committed his crime. In the last few years, he’s organized poetry readings, book clubs and fatherhood classes. When Gregory Fairchild, a professor at the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia, began an entrepreneurship program at Dillwyn Correctional Center, Anthony was among the graduates, earning all three of the certificates that it offered. He worked to have me invited as the commencement speaker, and what I remember most is watching him share a meal with his parents for the first time since his arrest. But he must pray that the governor grants him a conditional pardon, as he did for Fats.

I tell myself that my friends are unique, that I wouldn’t fight so hard for just anybody. But maybe there is little particularly distinct about any of us — beyond that we’d served enough time in prison. There was a skinny light-skinned 15-year-old kid who came into prison during the years that we were there. The rumor was that he’d broken into the house of an older woman and sexually assaulted her. We all knew he had three life sentences. Someone stole his shoes. People threatened him. He’d had to break a man’s jaw with a lock in a sock to prove he’d fight if pushed. As a teenager, he was experiencing the worst of prison. And I know that had he been my cellmate, had I known him the way I know my friends, if he reached out to me today, I’d probably be arguing that he should be free.

But I know that on the other end of our prison sentences was always someone weeping. During the middle of Harris’s presidential campaign, a friend referred me to a woman with a story about Senator Harris that she felt I needed to hear. Years ago, this woman’s sister had been missing for days, and the police had done little. Happenstance gave this woman an audience with then-Attorney General Harris. A coordinated multicity search followed. The sister had been murdered; her body was found in a ravine. The woman told me that “Kamala understands the politics of victimization as well as anyone who has been in the system, which is that this kind of case — a 50-year-old Black woman gone missing or found dead — ordinarily does not get any resources put toward it.” They caught the man who murdered her sister, and he was sentenced to 131 years. I think about the man who assaulted my mother, a serial rapist, because his case makes me struggle with questions of violence and vengeance and justice. And I stop thinking about it. I am inconsistent. I want my friends out, but I know there is no one who can convince me that this man shouldn’t spend the rest of his life in prison.

My mother purchased her first single-family home just before I was released from prison. One version of this story is that she purchased the house so that I wouldn’t spend a single night more than necessary in the childhood home I walked away from in handcuffs. A truer account is that by leaving Suitland, my mother meant to burn the place from memory.

I imagined that I had singularly introduced my mother to the pain of the courts. I was wrong. The first time she missed work to attend court proceedings was to witness the prosecution of a kid the same age as I was when I robbed a man. He was probably from Suitland, and he’d attempted to rob my mother at gunpoint. The second time, my mother attended a series of court dates involving me, dressed in her best work clothes to remind the prosecutor and judge and those in the courtroom that the child facing a life sentence had a mother who loved him. The third time, my mother took off days from work to go to court alone and witness the trial of the man who raped her and two other women. A prosecutor’s subpoena forced her to testify, and her solace came from knowing that prison would prevent him from attacking others.

After my mother told me what had happened to her, we didn’t mention it to each other again for more than a decade. But then in 2018, she and I were interviewed on the podcast “Death, Sex & Money.” The host asked my mother about going to court for her son’s trial when he was facing life. “I was raped by gunpoint,” my mother said. “It happened just before he was sentenced. So when I was going to court for Dwayne, I was also going for a court trial for myself.” I hadn’t forgotten what happened, but having my mother say it aloud to a stranger made it far more devastating.

On the last day of the trial of the man who raped her, my mother told me, the judge accepted his guilty plea. She remembers only that he didn’t get enough time. She says her nose began to bleed. When I asked her what she would have wanted to happen to her attacker, she replied, “That I’d taken the deputy’s gun and shot him.”

Harris has studied crime-scene and autopsy photos of the dead. She has confronted men in court who have sexually assaulted their children, sexually assaulted the elderly, scalped their lovers. In her 2009 book, “Smart on Crime,” Harris praised the work of Sunny Schwartz — creator of the Resolve to Stop the Violence Project, the first restorative-justice program in the country to offer services to offenders and victims, which began at a jail in San Francisco. It aims to help inmates who have committed violent crimes by giving them tools to de-escalate confrontations. Harris wrote a bill with a state senator to ensure that children who witness violence can receive mental health treatment. And she argued that safety is a civil right, and that a 60-year sentence for a series of restaurant armed robberies, where some victims were bound or locked in freezers, “should tell anyone considering viciously preying on citizens and businesses that they will be caught, convicted and sent to prison — for a very long time.”

Politicians and the public acknowledge mass incarceration is a problem, but the lengthy prison sentences of men and women incarcerated during the 1990s have largely not been revisited. While the evidence of any prosecutor doing work on this front is slim, as a politician arguing for basic systemic reforms, Harris has noted the need to “unravel the decades-long effort to make sentencing guidelines excessively harsh, to the point of being inhumane”; criticized the bail system; and called for an end to private prisons and criticized the companies that charge absurd rates for phone calls and electronic-monitoring services.

In June, months into the Covid-19 pandemic, and before she was tapped as the vice-presidential nominee, I had the opportunity to interview Harris by phone. A police officer’s knee on the neck of George Floyd, choking the life out of him as he called for help, had been captured on video. Each night, thousands around the world protested. During our conversation, Harris told me that as the only Black woman in the United States Senate “in the midst of the killing of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery,” countless people had asked for stories about her experiences with racism. Harris said that she was not about to start telling them “about my world for a number of reasons, including you should know about the issue that affects this country as part of the greatest stain on this country.” Exhausted, she no longer answered the questions. I imagined she believes, as Toni Morrison once said, that “the very serious function of racism” is “distraction. It keeps you from doing your work.”

But these days, even in the conversations that I hear my children having, race suffuses so much. I tell Harris that my 12-year-old son, Micah, told his classmates and teachers: “As you all know, my dad went to jail. Shouldn’t the police who killed Floyd go to jail?” My son wanted to know why prison seemed to be reserved for Black people and wondered whose violence demanded a prison cell.

“In the criminal-justice system,” Harris replied, “the irony, and, frankly, the hypocrisy is that whenever we use the words ‘accountability’ and ‘consequence,’ it’s always about the individual who was arrested.” Again, she began to make a case that would be familiar to any progressive about the need to make the system accountable. And while I found myself agreeing, I began to fear that the point was just to find ways to treat officers in the same brutal way that we treat everyone else. I thought about the men I’d represented in parole hearings — and the friends I’d be representing soon. And wondered out loud to Harris: How do we get to their freedom?

“We need to reimagine what public safety looks like,” the senator told me, noting that she would talk about a public health model. “Are we looking at the fact that if you focus on issues like education and preventive things, then you don’t have a system that’s reactive?” The list of those things becomes long: affordable housing, job-skills development, education funding, homeownership. She remembered how during the early 2000s, when she was the San Francisco district attorney and started Back on Track (a re-entry program that sought to reduce future incarceration by building the skills of the men facing drug charges), many people were critical. “ ‘You’re a D.A. You’re supposed to be putting people in jail, not letting them out,’” she said people told her.

It always returns to this for me — who should be in prison, and for how long? I know that American prisons do little to address violence. If anything, they exacerbate it. If my friends walk out of prison changed from the boys who walked in, it will be because they’ve fought with the system — with themselves and sometimes with the men around them — to be different. Most violent crimes go unsolved, and the pain they cause is nearly always unresolved. And those who are convicted — many, maybe all — do far too much time in prison.

And yet, I imagine what I would do if the Maryland Parole Commission contacted my mother, informing her that the man who assaulted her is eligible for parole. I’m certain I’d write a letter explaining how one morning my mother didn’t go to work because she was in a hospital; tell the board that the memory of a gun pointed at her head has never left; explain how when I came home, my mother told me the story. Some violence changes everything.

The thing that makes you suited for a conversation in America might be the very thing that precludes you from having it. Terell, Anthony, Fats, Luke and Juvie have taught me that the best indicator of whether I believe they should be free is our friendship. Learning that a Black man in the city I called home raped my mother taught me that the pain and anger for a family member can be unfathomable. It makes me wonder if parole agencies should contact me at all — if they should ever contact victims and their families.

Perhaps if Harris becomes the vice president we can have a national conversation about our contradictory impulses around crime and punishment. For three decades, as a line prosecutor, a district attorney, an attorney general and now a senator, her work has allowed her to witness many of them. Prosecutors make a convenient target. But if the system is broken, it is because our flaws more than our virtues animate it. Confronting why so many of us believe prisons must exist may force us to admit that we have no adequate response to some violence. Still, I hope that Harris reminds the country that simply acknowledging the problem of mass incarceration does not address it — any more than keeping my friends in prison is a solution to the violence and trauma that landed them there.

In light of Harris being endorsed by Biden and highly likely to be the Democratic Party candidate, I thought I would share this balanced, understanding of both sides, article in regard to Harris and her career as a prosecutor, as I know that will be something dragged out by bad actors and useful idiots (you have a bunch of people stating 'Kamala is a cop', which is completely false, and also factless and misleading statements about 'mass incarceration' under her). I'm not saying she doesn't deserve to be criticised or that there is nothing about her career that can be criticised, but it should at least be representative of the truth and understanding of the complexities of the legal system.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Donald Trump is expected to be indicted this week by a Manhattan grand jury following an investigation by Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg Jr. into whether Trump’s alleged payment of hush money to former porn star Stormy Daniels rose to felony-level criminality on the part of the ex-president. Once again, Trump is facing court over allegedly shady dealings, and his chief nemesis is a Black man, only this time that Bragg isn’t trying to rent one of Trump’s apartments, he’s seeking a historic conviction that could mark the first time a former president ends up incarcerated.

If it feels like Trump has spent the last 50 years being sued over his business practices and antagonizing Black people, your instinct isn’t far off. In 1973, the Justice Department sued Trump for discriminating against Black prospective tenants in his then rental real estate portfolio. Trump settled, and to this day claims he did nothing wrong. That lawsuit foreshadowed two themes in Trump’s life that this week could also begin his downfall: court battles over his business practices and tussles with Black folks who refused to be cowed by his racist public policy and rhetoric.

Since then, Trump been accused of jerking contractors who worked on his construction sites out of their money. The Trump Organization reorganized under federal bankruptcy protection three times. The company was convicted last year of tax fraud. He bought an infamous full-page New York Times ad asking for the death penalty (which didn’t exist in New York at the time) for five Black teenagers who were ultimately exonerated for the rape of a white woman who was jogging in Central Park. His presidential campaign and four years in the White House centered on anti-Black and anti-immigrant demagoguery.

So you’re not wrong if you also think it’s fitting that since leaving office, the biggest threats to his fortune and his freedom are investigations led by three Black prosecutors: Bragg, Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis, whose office could still indict Trump over his attempts to undo Georgia’s 2020 election results, and New York Attorney General Letitia James, who is suing the Trump Organization in civil court over the kind of accounting practices at the company’s criminal conviction.

Trump has tried hard to delay or derail all those investigations. He challenged subpoenas. He filed an unsuccessful countersuit against James. He made veiled threats against Willis. He was seen sticking a banana in the tailpipe of Bragg’s chauffeured SUV (ok, that didn’t happen but you can’t stop seeing the visual, can you?). As late as Monday morning, his legal team filed paperwork to try to get Willis thrown off the case and to seal her grand jury’s report, which recommends criminal charges against multiple, unnamed people. Wanna guess who one of those people just might be? So far, none of it has worked.

Still, that it’s Bragg whose investigation appears to have reached the finish line first is ironic. A year ago this week, I questioned whether Bragg was pulling punches on Trump after one of the former lead prosecutors from Bragg’s team wrote a scathing resignation letter that accused his ex-boss of ignoring overwhelming evidence that Trump had committed multiple felonies. Back then, it looked like if any of the investigations against Trump would implode, it would be Bragg’s.

I’ve interviewed Bragg several times since and asked him directly about the Trump investigation. Every time, he was measured and cautious with his words, demure about discussing an ongoing grand jury proceeding. But never once did he close the door on the idea that his office would prosecute Trump if evidence led the grand jury to indict. And as I noted in last year’s piece, it’s pretty easy for New York prosecutors to get grand juries to bring charges if they really want to.

Of course, an indictment is a long, long way from a conviction and the trial of a former president–especially one that would play out in a New York courtroom–would be a spectacle that would do more pay-per-view buys than a Floyd Mayweather fight. But if boxing is the appropriate metaphor for Trump’s current legal woes, maybe with all his antagonizing, he finally picked the wrong opponent, somebody he couldn’t push around the ring too easily. Somebody willing to punch back, or even go on the offensive. Maybe this time, he finally loses.

#Will This Black Man Be Donald Trump's Downfall?#Alvin Bragg#NY State Prosecutors#donald trump#Stormy Daniels

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Martin Luther King Jr., Guns, and a Book Everyone Should Read

BY JEREMY S. | JAN 15, 2018

“Martin Luther King Jr. would have been 89 years old today, were he not assassinated in 1968. On the third Monday in January we observe MLK Jr. Day and celebrate his achievements in advancing civil rights for African Americans and others. While Dr. King was a big advocate of peaceful assembly and protest, he wasn’t, at least for most of his life, against the use of firearms for self-defense. In fact, he employed them . . .

If it wasn’t for African Americans in the South, primarily, taking up arms almost without exception during the post-Civil War reconstruction and well into the civil rights movement, this country wouldn’t be what it is today.

By force and threat of arms African Americans protected themselves, their families, their homes, and their rights and won the attention and respect of the powers that be. In a lawless, post-Civil War South they stayed alive while faced with, at best, an indifferent government and, at worst, state-sponsored violence against them.

We know the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857 refused to recognize black people as citizens. Heck, they were deemed just three-fifths a person. Not often mentioned in school: some of that was due to gun rights. Namely, not wanting to give gun rights to blacks. Because if they were to recognize blacks as citizens, it…

“…would give to persons of the negro race . . . the right to enter every other State whenever they pleased, . . . and it would give them the full liberty of speech . . . ; to hold public meetings upon political affairs, and to keep and carry arms wherever they went.”

Ahha! So the Second Amendment was considered an individual right, protecting a citizen’s natural, inalienable right to keep and carry arms wherever they go. Then as now, gun control is rooted in racism.

During reconstruction, African Americans were legally citizens but were not always treated as such. Practically every African American home had a shotgun — or shotguns — and they needed it, too. Forget police protection, as those same officials were often in white robes during their time off.

Fast forward to the American civil rights movement and we learn, but again not at school, that Martin Luther King Jr. applied for a concealed carry permit. He (an upstanding minister, mind you) was denied.

Then as in many cases even now, especially in blue states uniquely and ironically so concerned about “fairness,” permitting was subjective (“may issue” rather than “shall issue”). The wealthy and politically connected receive their rights, but the poor, the uneducated, the undesired masses, not so much.

Up until late in his life, MLK Jr. chose to be protected by the Deacons for Defense. Though his home was also apparently a bit of an arsenal.

African Americans won their rights and protected their lives with pervasive firearms ownership. But we don’t learn about this. We don’t know about this. It has been unfortunately whitewashed from our history classes and our discourse.

Hidden, apparently, as part of an agreement (or at least an understanding) reached upon the conclusion of the civil rights movement.

Sure, the government is going to protect you now and help you and give you all of the rights you want, but you have to give up your guns. Turn them in. Create a culture of deference to the government. Be peaceable and non-threatening and harmless. And arm-less, as it were (and vote Democrat). African Americans did turn them in, physically and culturally.

That, at least, is an argument made late in Negroes and the Gun: the Black Tradition of Arms. It’s a fantastic book, teaching primarily through anecdotes of particular African American figures throughout history just how important firearms were to them. I learned so-freaking-much from this novel, and couldn’t recommend it more. If you have any interest in gun rights, civil rights, and/or African American history, it’s an absolute must-read.

Some text I highlighted on my Kindle Paperwhite when I read it in 2014:

But Southern blacks had to navigate the first generation of American arms-control laws, explicitly racist statutes starting as early as Virginia’s 1680 law, barring clubs, guns, or swords to both slaves and free blacks.

“…he who would be free, himself must strike the blow.”

In 1846, white abolitionist congressman Joshua Giddings of Ohio gave a speech on the floor of the House of Representatives, advocating distribution of arms to fugitive slaves.

Civil-rights activist James Forman would comment in the 1960s that blacks in the movement were widely armed and that there was hardly a black home in the South without its shotgun or rifle.

A letter from a teacher at a freedmen’s school in Maryland demonstrates one set of concerns. The letter contains the standard complaints about racist attacks on the school and then describes one strand of the local response. “Both the Mayor and the sheriff have warned the colored people to go armed to school, (which they do) [and] the superintendent of schools came down and brought me a revolver.”

Low black turnout resulted in a Democratic victory in the majority black Republican congressional district.

Other political violence of the Reconstruction era centered on official Negro state militias operating under radical Republican administrations.

“The Winchester rifle deserves a place of honor in every Black home.” So said Ida B. Wells.

Fortune responded with an essay titled “The Stand and Be Shot or Shoot and Stand Policy”: “We have no disposition to fan the coals of race discord,” Thomas explained, “but when colored men are assailed they have a perfect right to stand their ground. If they run away like cowards they will be regarded as inferior and worthy to be shot; but if they stand their ground manfully, and do their own a share of the shooting they will be respected and by doing so they will lessen the propensity of white roughs to incite to riot.”

He used state funds to provide guns and ammunition to people who were under threat of attack.

“Medgar was nonviolent, but he had six guns in the kitchen and living room.”

“The weapons that you have are not to kill people with — killing is wrong. Your guns are to protect your families — to stop them from being killed. Let the Klan ride, but if they try to do wrong against you, stop them. If we’re ever going to win this fight we got to have a clean record. Stay here, my friends, you are needed most here, stay and protect your homes.”

In 2008 and 2010, the NAACP filed amicus briefs to the United States Supreme Court, supporting blanket gun bans in Washington, DC, and Chicago. Losing those arguments, one of the association’s lawyers wrote in a prominent journal that recrafting the constitutional right to arms to allow targeted gun prohibition in black enclaves should be a core plank of the modern civil-rights agenda.

Wilkins viewed the failure to pursue black criminals as overt state malevolence and evidence of an attitude that “there’s one more Negro killed — the more of ’em dead, the less to bother us. Don’t spend too much money running down the killer — he may kill another.”

But it puts things in perspective to note that swimming pool accidents account for more deaths of minors than all forms of death by firearm (accident, homicide, and suicide).

The correlation of very high murder rates with low gun ownership in African American communities simply does not bear out the notion that disarming the populace as a whole will disarm and prevent murder by potential murderers.

Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimated 1,900,000 annual episodes where someone in the home retrieved a firearm in response to a suspected illegal entry. There were roughly half a million instances where the armed householder confronted and chased off the intruder.

A study of active burglars found that one of the greatest risks faced by residential burglars is being injured or killed by occupants of a targeted dwelling. Many reported that this was their greatest fear and a far greater worry than being caught by police.48 The data bear out the instinct. Home invaders in the United States are more at risk of being shot in the act than of going to prison.49 Because burglars do not know which homes have a gun, people who do not own guns enjoy free-rider benefits because of the deterrent effect of others owning guns. In a survey of convicted felons conducted for the National Institute of Justice, 34 percent of them reported being “scared off, shot at, wounded or captured by an armed victim.” Nearly 40 percent had refrained from attempting a crime because they worried the target was armed. Fifty-six percent said that they would not attack someone they knew was armed and 74 percent agreed that “one reason burglars avoid houses where people are at home is that they fear being shot.”

In the period before Florida adopted its “shall issue” concealed-carry laws, the Orlando Police Department conducted a widely advertised program of firearms training for women. The program was started in response to reports that women in the city were buying guns at an increased rate after an uptick in sexual assaults. The program aimed to help women gun owners become safe and proficient. Over the next year, rape declined by 88 percent. Burglary fell by 25 percent. Nationally these rates were increasing and no other city with a population over 100,000 experienced similar decreases during the period.55 Rape increased by 7 percent nationally and by 5 percent elsewhere in Florida.

As you can see, Negroes and the Gun progresses more or less chronologically, spending the last portion of the book discussing modern-day gun control. It’s an invaluable source of ammunition (if you’ll pardon the expression) against the fallacies of the pro-gun-control platform. It sheds light on a little-known (if not purposefully obfuscated), critical factor in the history of African Americans: firearms.

On this Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I highly recommend you — yes, you — read Negroes and the Gun: the Black Tradition of Arms.

And I’ll wrap this up with a quote in a Huffington Post article given by Maj Toure of Black Guns Matter:

https://cdn0.thetruthaboutguns.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/huffpo-maj-toure.jpg”

#books#black history#history#american history#Guns#civil rights#constitution#supreme court#gun control#martin luther king jr.#dread scott#concealed carry#concealedcarry#everydaycarry#gun confiscation

288 notes

·

View notes

Note

What? You afraid of little different opinions from your own? The reason you didn’t answer back is because you have no argument carols wasn’t innocent he deserved to die. He had prior criminal records to rape so um you wept for a rapist.

First of all, I was asleep and this is a case I feel strongly about so wanted to give a proper reply. Secondly, he was charged with attempted rape when he cornered his friend’s mother and opened her shirt before running away. Not that that’s okay, I just thought I’d mention the exact charge.

Before we speak about Carlos Hernandez, I’d like to point that the crime scene was completely mishandled. It was a particularly bloody scene with blood throughout the store and out on the forecourt. Inside, Wanda’s flipflops which had come off during the struggle were found behind the counter and a folding knife with its blade exposed was abandoned on the floor nearby. They found shoe prints, a cigarette butt, chewing gum and clumps of hair but these were all overlooked Three fingerprints were found – two on the front door and another on the telephone. However, they were all such poor quality that they were allegedly unusable. There were no fingerprints on the knife. No samples of blood were taken or tested despite the fact that it was probably likely that the killer sustained an injury himself during the frenzied attack. It took less than an hour for the crime scene to be processed. The reason? They were so adamant they had already arrested the killer that they felt there was no need.

There is an abundance of evidence against Carlos Hernandez, who DeLuna named as the killer. He wasn’t identified until after DeLuna was executed but when he was, they decided to come forward and relay their own beliefs that their family member was the killer of Wanda. In fact, Hernandez was well known to police and prosecutors at the time of the trial and had a lengthy police record. He had a long history of violence which included stabbings committed with a knife that was very similar to the one found at the crime scene.

He was in and out trouble with the law throughout his life. In 1971, he was convicted of negligent homicide after he killed his sister’s fiancé while driving drunk. His sentence was suspended and he received no jail time. The following year, he received a 20 year sentence for holding up several gas stations. After just five short years, he was paroled. Then in 1979, Hernandez was arrested for the brutal murder of Dahlia Sauceda, who was found beten an strangled to death in her van. A crude X had also been carved into her body. Hernandez was tied to the crime when his fingerprints were discovered on a beer can inside the van alongside a pair of his boxers. While being held for this crime, Hernandez somehow managed to point the blame towards another man. Prosecutor Ken Botary – who would later be the co-prosecutor in the DeLuna trial – interviewed Hernandez. Furthermore, Hernandez was taken to the interview by Detective Olivia Escobedo, the lead investigator in Lopez’ murder who claimed Hernandez didn’t exist!

Astonishingly, Hernandez was once again released while the other man was acquitted. In 1986, he was re-arrested for the murder of Sauceda after new evidence surfaced. However, the evidence was somehow misplaced and the charges were dropped. Hernandez was once again a free man.

Two months after Lopez’ murder, Hernandez was arrested outside a convenience store with a knife and then several months later, he attacked his wife, Rosa, with an ax handle. During the attack, he smashed a window, shattering glass onto Rosa’s sleeping children. He threatened to kill her and the kids. He was sentenced to just 30 days in jail during which Rosa filed for divorce. In 1989, Hernandez attacked Dina Ybanez with a 7-inch lock-blade buck knife. While he received a ten year sentence, he was paroled after just a year and a half. Then in 1996, he attacked his neighbour with a 9-inch kitchen knife. Three years later, Hernandez died in prison.

The Chicago Tribune not only interviewed Hernandez’s friends and family, but also reviewed thousands of court records. Their findings indicated that the case was compromised by unreliable eyewitness identification, lazy police work and a complete failure to pursue Hernandez as a potential suspect. After all, the police and prosecutors flat out denied he even existed.

The investigation also uncovered that Hernandez had bragged to at least five people about the murder of Lopez as well as the murder of Fahlia Sauceda. Janie Adrian, a neighbour of Hernanfez, told The Chicago Tribune that she had overheard Hernandez talk about stabbing Lopez on at least three occasions.

Dina Ybanez also told the newspaper that Hernandez had confessed to killing Lopez to her and her husband. Both women said that they were too afraid to come forward earlier, particularly Dina, who had been stabbed by Hernandez in the past. She said that during that attack, he had threatened that “he was going to kill me like he did her.” Two other women – Beatrice Tapia and Pricilla Jaramillo – were just young girls when they heard Hernandez confess to the murder. Jaramillo was Hernandez’ cousin and she had been living at Hernandez’ mothers house.

One afternoon, she and Tapia overheard Hernandez speaking to his brother about the murder shortly after it happened. Jaramillo was too terrified to tell anybody about what she had heard because Hernandez had molested her in the past and she was scared of him. The Chicago Tribune also managed to track down Miguel Ortiz, an acquaintance of Hernandez. HE told the newspaper that Hernandez had openly confessed to the murder to him.

The Chicago Tribune even spoke with a former detective named Eddie Garza who said that before the trial, he received tips about Hernandez.

He said that he had heard from informants that Hernandez was openly bragging about the murder. As a detective, Garza knew both DeLuna and Hernandez and said that the crime seemed more like something Hernandez would do, not DeLuna. Garza said that he passed the information on to Olivia Escobedo, the detective leading the investigation. Escobedo, however, claimed she never received such tips. While Garza claims he knew about Hernandez, he still testified at DeLuna’s hearing and told the jury that DeLuna had a bad reputation.

In 2012, The Columbia Human Rights Law Review released a 400-page report which detailed the events of DeLuna’s trial and stated that he had been wrongfully convicted executed. Columbia Law School professor James Liebman and his students had conducted the study as a contribution towards a public debate on the death penalty. They specifically argued that it is an ineffective form of punishment. The group decided on covering the DeLuna case after Liebman did a study on courts across the United States and how they handled legal error.

They tracked down the witness that identified DeLuna while he was sat in the back seat of a dark police car later confessed he was less than 50% sure because “all Hispanics look the same.” He later said he only said DeLuna was the man because officers told them he was. His statement is recorded. There was no evidence against him found inside the store. It was a bloody crime scene yet there was no blood on him.

The Columbia study asserted that it was Hernandez who committed the murder, not DeLuna. “On evidence we pulled together on this case, there is no way a jury could have convicted De-Luna beyond a reasonable doubt, but they could’ve convicted Hernandez beyond a reasonable doubt,” Liebman said.

The Columbia study, which was called “Los Tocayos Carlos,” took five years of investigation to complete. Liebman said that his findings not only show that DeLuna was innocent but that Hernandez was a real person and was guilty of the murder DeLuna was executed for. He wrote that every single thing that could’ve went wrong in a case, did, and that the wrongful arrest of DeLuna was made specifically to avoid departmental embarrassment for the 911 operator not responding to Lopez’s first call for help. The Columbia Study went on to turn their findings into a book named “The Wrong Carlos: Anatomy of a Wrongful Conviction.”

You should read the book and read through all of the evidence that is readily available instead of basing your opinion on the fact that somebody had an attempted rape conviction. If that’s what you’re basing your opinion on then you should look at Hernandez’ history. It’s pretty widely accepted that Carlos DeLuna is innocent and his wrongful execution even led to laws being changed. I would also like to point of if even if DeLuna WAS guilty, I still wouldn’t agree with somebody with an intellectual disability, with the mindset of a child, executed never mind a botched execution.

This isn’t isolated case, either. Three decades have passed since DeLuna was executed but the flaws that condemned him still reverberate in the criminal justice system today - faulty eyewitness testimony, a quick to convict police force, lousy legal representation and withholding of evidence. American is the outlier among industrialized nations and it is the only country in the New World that continues to execute prisoners… Whether or not we agree with it, the death penalty is an extremely flawed system (and racist, biased, hypocritical and archaic) and one that I don’t support.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

I never do this but I’m fucking pissed

This man. If you're not Italian it's more than likely that you've never heard of him before. Well, lucky you. I'm not using irony here, if you've never heard of him, you really are in luck. So, this man is part of a political party called Lega Nord, or Northern League. What many don't know or don't seem to remember, is that the name of his party as a whole is Northern League for the Independence of Padania. Padania is the northern part of Italy so yes, exactly, the main goal of the party was to split Italy in a half. Why? "the south of Italy is made by people who don't want to work, who steal and rob and kill, mafiosi can do whatever they want and there's no law in the south." I'm not saying this. You know where all of this comes from?

Yeah. Racist against their own people. I said before that people "seem to forget about this", and that's because to win the Italian elections of last year the party stopped calling itself Northern League and instead just League, this was made to get the votes of the south of Italy too. But how could those people forget the racist words of Salvini and the League?

Immigrants. African immigrants. They come to Italy to "steal jobs and sell drugs and be criminals". But wait I... I know this. I've already heard it somewhere.

Oh now I remember. If it wasn't clear before, the League is a party of extreme right, so of course they'd hate immigrants. Of course they do. But back to the point. African immigrants have become a big deal in Europe as a whole, the main problem being that the refugees -because let's be real, most of them are refugees-, sail from the Libyan coast to the closest country on the other side of the Mediterranean sea. Which happens to be Italy -or Greece in some cases-. Italy's not a choice, it just happens to be closer to Libya. And yeah they could sail for a bit more and get to the countries where they actually want to go -because guess what, the majority of them don't even wanna come here-, only they can't, because their boats are these.

2014: 3538 deaths 2015: 3771 deaths 2016: 5096 deaths 2017: 3139 deaths 2018: 2023 deaths It breaks my heart to write this. The number of deaths has decreased, but that's only partially good, because the Italian elections of 2018 were won by the League and the 5 Stars Movement, a populist party which has many objectives but... Very few ways of achieving them? Still, the Salvini made it so that African boats could not let anyone off and on Italian grounds, the boats found within Italian boundaries were sent back to Lybia and the people on them?

Here. Libyan prisons are hell for those people, and anyone found on those boats ends up in there. To be raped or hit or beat to death sometimes. This ban on immigrant boats had consequences though, because last summer an Italian boat found 190 people on interational waters close to Malta. 13 people were immediately transferred to Lampedusa, Sicily, because they needed medical care, the rest of them spent four days on the boat, and when they could finally land, Salvini said no, they couldn't set foot on Italian grounds. But he couldn't do that, because yes he's a Ministry, but he can't give that sort of orders without the approval of the Parliament. So he had to go to trial. But here in Italy, I don't know if in other countries it's the same, the Parliament can decide whether or not a Ministry has to go through trial or not. Guess what. Of course he didn't, of fucking course. Also, Salvini has said some awful stuff, talking about a "massive cleaning" with "strong methods". I'd like to say "he's just so fucking crazy" but he's not, he's saying things with a confidence and conviction that gives me the chills. He's said that LGBT+ rights are not a priority, he's anti-vax of course and mocks climate change. He's an awful, awful person, and yet he's one of the most beloved politicians in Italy. Lastly, Italy is seeing more and more fascist rallies, and all of them call out his name as if he was some kind of god. That's alarming and I think more people should talk about this. I probably forgot half of the things Salvini's done, but all of this, all of this came out just from the top of my head.

#politics#donald trump#matteo salvini#fascisim#italy#please read#lgbtq#vaccines#immigration#refugees#africa#libya#europe#european elections#i know i'm gonna get hate for this#but honestly#i don't ever care at this point#like yeah i do care but still#this is important#read#racism

489 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oprah’s Message: “If When They See Us is Hard to Watch...”

Oprah is over the moon about the success of the Ava DuVernay’s Netflix series “When They See Us.” As an executive producer for the project, Ms. Winfrey made it clear: “If you haven’t seen yet...please do. And for everyone who says it’s “hard to watch,” think about the people who still find it “hard to live.” All those families impacted!”

The four part series which premiered last Friday tells the true story of the black teenagers known as the Central Park Five. Under the hand of the law, these children were wrongfully and aggressively accused of the rape of a 28-year-old white woman in 1989. Their case resonated across the globe due the lack of evidence against them and the mishandling of justice on their behalf. Although later vindicated and awarded $41 million dollars by New York City, these children went to prison with one of them, Korey Wise, serving 12 years of a 5 - 15 year sentence.

Via Instagram Oprah praised actor Jharrel Jerome with a photo and caption, "Can we all stand up and give @jharreljerome a round of applause. Incredible performance #standingovation." Jharrel, who portrayed Korey Wise, added a comment to her post saying, “ Thank you so much, Oprah. From the bottom of my heart. You have inspired my family and I, and have taught us how to love and overcome. For my work to deserve a standing ovation from you is UNBELIEVABLE. Okay. I’m gonna go cry and tell my mom now.” Oprah also shouted out the actresses who played his mother and transgender sister in the series.

Since the release of the provocative true story, white privilege has been revoked for Linda Fairstein. Based off of the accurate telling of the story, Fairstein has been forced to resign from executive boards, close out her social media accounts, and was stripped of her 1993 Glamour Magazine Women of the Year Award. In a open letter, Editor in Chief Samantha Barry shared “Unequivocally, Glamour would not bestow this honor on her today. She received the award in 1993, before the full injustices in this case were brought to light. Though the convictions were later vacated and the men received a settlement from the City of New York, the damage caused is immeasurable.” The #CancelLindaFairstein has pretty much ended the former prosecutor for her racist, prejudice, and negligent role in robbing black children of justice. Fairstein, who went on to become a best selling author, has also been dropped from many retailers.

Even after the admitted and proven criminal, Matias Reyes, was found to be guilty with DNA evidence, Fairstein still maintains she was right about the case. In a 2013 tweet, President Donald J. Trump, who took out a $88,000 dollar ad calling for the death penalty for the kids accused said, “The Central Park Five documentary was a one sided piece of garbage that didn't explain the horrific crimes of these young men while in park.”

Thankfully karma has come back to re-balance the scales of justice!

#Isis King#Niecy Nash#Marci Wise#Delores Wise#Korey Wise#Raymond Santana#Antron McCray#Kevin Richardson#Yusef Salaam#Central Park Five#Oprah Winfrey#Ava Duvernay#netflix#When They See Us#Jharrel Jerome#Linda Fairstein#Donald Trump#Glamour Magazine#Woman of the Year

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

On The Death Penalty

20/03/2020. Four out of the five (six, we don’t know whether Ram Singh killed himself or was killed) convicts of the infamous Nirbhaya rape case were finally given the noose. However, if we take a closer look, we’d notice that they didn’t die in 2020. Their fate was sealed seven years ago when the public, the politicians and the media displayed an insatiable thirst for their blood, hence proving the regressive nature of the world’s largest democracy.

Unlike the hanging of Yakub Memon or Afzal Guru, the hanging did not spark widespread outrage. Of course, one could propose multiple reasons for the same. Activists were already immersed in a movement against laws that were aimed at systemically exterminating the Indian Muslim population. Many of my liberal lads ideologically against capital punishment didn’t raise their voices either, claiming that the heinousness of the crime was “too much” for their conscience to stick to the liberal side of the death penalty debate. “Imagine what the mother went through”, they stated.

I cannot speak for the mother, or for anyone in the family, or for any of the victim’s friends and acquaintances. It is more than justified for them to demand justice in the form of the death. But I can speak for liberals, for those who have some shred of objectivity left (Tablighi Jamaat showed that many don’t).

We hear a lot of scattered arguments from today’s conservatives on why the noose, or the needle, or the electric chair is not only justified, but also necessary. I want to tidy up their poorly phrased arguments in a manner that can be constructively used to articulate my own arguments. The two arguments most stressed upon by the proponents are that the death penalty is “just”, and that it ensures “the greater good of society”, by deterring potential criminals (utilitarianism or consequentialism in philosophical jargon). I’ll start by talking about what they call justice, which I call vengeance. On this note, please welcome, our dear old friend, the one and only Immanuel Kant.

Kant’s argument on the death penalty, unlike his three Critiques and the Metaphysics of Morals, is pretty straightforward. He believes in strict equality (lex talionis in Latin jargon) in the magnitude of the crime and the magnitude of the punishment. Of course, it begs questions like, should a serial killer who murdered twenty-three people be injected twenty-three times and resuscitated after each injection, or should a terrorist be blown up to pieces as an “equal” punishment? What about a failed bombing attempt? How is the doctrine of strict equality going to punish liars and cheaters?

The argument of strict equality, basically, is not strict at all (understandably). The conservative interpretation of lex talionis can be stated as follows: Any crime which involves taking a life, or permanently damaging the soul of a human being, or a crime which shakes the moral fabric of society, should be met by a punishment proportional to that crime, and that punishment can only be proportional if it is death. When the liberal asks why, the conservative replies that no human has the right to take a life. The obvious (and weak) liberal response is inquiring about the criminal’s right to life, to which the conservative will paraphrase classic liberals like Kant and Mill, who argued that any human who violates another human’s right to life relinquishes his own. They can also argue that while a human can’t take another human’s life (even a criminal’s), a state, or a Leviathan can, because one of the main purposes of the Leviathan is justice.

So it boils down to me proving that the death penalty is not just.

Let’s begin.

There are two types of cases to make against the death penalty - that it is unjust in principle, or it just in principle but unjust in practice. The first set of arguments claim that it is morally wrong to take a criminal’s life, while the second set claims that while such actions can be morally condoned, the application of such a system of justice is unjust as it systematically targets certain groups of people, while completely ignoring certain other groups. I myself am a proponent of the first one. Defending the latter is relatively easier due to conclusive evidence, so I shall begin with the first one.

French sociologist Émile Durkheim, in his Two Laws of Penal Evolution argued that softening the standards of physical punishment is a sign of “progressive” societies. Such an argument should not surprise us at all since common sense has dictated most of us to call Saudi Arabia a “regressive” society due its refusal to abolish old-age methods of punishment like stoning, lashing and beheading. On the other hand, most first-world nations today, with the notable exception of the United States of America, have abolished the death penalty. India and China are not first-world yet, unlikely that India will ever be. Anyway, the idea that capital punishment does not belong to a progressive society is based on the liberal notion that the death penalty itself is not progressive at all, because it is immoral.

Some of you might have watched Batman Begins. In his League of Shadows training, Ra’s Al Ghul asks Bruce to execute a murderer with a swipe of his sword. Bruce refuses, to which Ghul replies that his compassion is a trait that his enemies will not share. Bruce’s response might just be the greatest quote of the Dark Knight Trilogy, “that’s why it’s so important, it distinguishes us from them.”

The point is that the death penalty brings us down to the moral level of the criminals. This is directly linked to Kant’s eye for an eye argument. If we take an eye for an eye, we respond to barbarity with barbarity. Hence, in our quest for “justice”, we become barbarians too, and justice loses its meaning and is replaced by revenge. Killing is responded to by killing, making everyone a murderer, and hence, immoral.

The counter-argument is often the utilitarian/consequentialist one, that is, capital punishment would deter future crimes by instilling fear into would-be criminals, and therefore, even an immoral act like the death penalty has a morally acceptable outcome, that is, a safer society. But the utilitarians are rather funny in this debate, they’d be willing to hang an innocent man too if they had evidence that that particular miscarriage of justice would lead to a positive outcome in society (like fewer crimes), which is why it does not stand any chance against any deontological argument about the death penalty.

But the most basic flaw in the utilitarian argument is the belief that the death penalty deters, it does not. Not only do statistics contradict the utilitarian claim, but with respect to India, think of the Ranga-Billa case. How many rapes have been prevented by sentencing Ranga and Billa to death? Proponents will say that even if the rape numbers did not go down post Ranga-Billa, numbers could have gone up, but the hanging did not allow rape numbers to spike. Such an argument is wishful thinking and mere speculation.

The right to life is an inalienable right, god-given for believers, and a natural right for atheists. The only two ways this right can be snatched away is via God or via nature. It cannot be taken away by fellow humans, even if some fellow humans have entered into a contractual agreement with each other to form a Leviathan. Not to forget, it is irreversible, and thus the chances of a travesty of justice become much higher. A man being wrongfully imprisoned for a few years is nothing in contrast to man wrongfully given the electric chair. Please read about the case of Timothy Evans, who was wrongfully hanged in Britain for the murder of his wife and child, after which the death penalty was eventually abolished all over Britain. The actual murders were committed by the infamous serial killer John Christie, but that’s a different conversation.

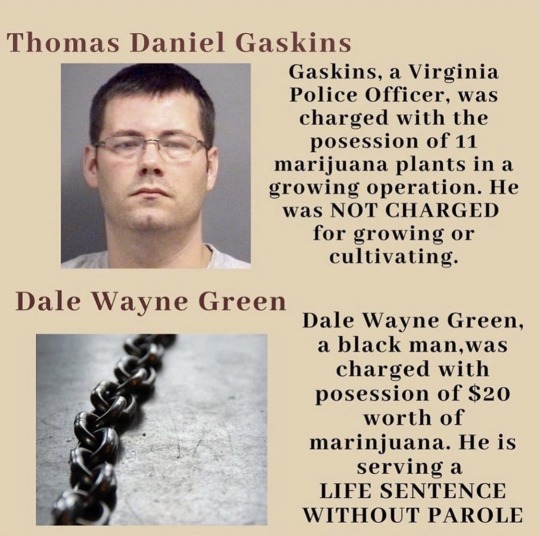

Some soft abolitionists argue that while the death penalty is morally just, its application in real life makes it an unjust practice. The simplest example to illustrate this in India’s case is Kuldeep Singh Sengar. This vile creature, along with his henchmen and relatives, raped a girl for over a month and murdered her father. Did he get the noose? He didn’t. Why? Powerful politician and an upper-caste Hindu? Most likely. That should illustrate the argument, that the death penalty is classist, casteist and racist. Forget intra-community violence, studies have shown that in the USA, blacks are much more likely to be executed for killing whites than whites who have killed blacks. This comes as a surprise to none, so why do the proponents keep their mouth shut about the explicitly discriminatory nature of the noose, the needle, and the chair?

Weak communities and minorities are easy targets. The truth is, the death penalty does not apply to white people, or the rich, or upper castes in India. Sajjan Kumar and Jagdish Tytler, notable Congress politicians who took part in the 1984 pogrom of the Sikhs, did not receive the noose. Kamal Nath was made Chief Minister. Babu Bajrangi and Maya Kodnani, convicted of committing unfathomable crimes in the 2002 pogrom against Muslims were sentenced to prison but are out on bail. The justice system is a joke. So do not put forward the case of the death penalty when its just application is unlikely in an unjust justice system.

There are many other nuanced sociological arguments against capital punishment (like if poor people are more prone to crimes and hence capital punishment, is the state equally responsible for the crimes committed) that I shall not get into, due to the increasing length of this blog. But I’d like to end on a Kantian note. Kant proposed three basic necessities in his support of capital punishment. Proponents shout out the first one, but ignore the other two. They support Kant when he says that the magnitude of the punishment should be equal to the magnitude of the crime. However, they look the other way when he says that only the guilty should be punished, and all the guilty should be punished. Think about whether the last two are fairly applicable in today’s society.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Against Innocence Race, Gender, and the politics of Safety

Saidiya V. Hartman: I think that gets at one of the fundamental ethical questions/problems/crises for the West: the status of difference and the status of the other. It’s as though in order to come to any recognition of common humanity, the other must be assimilated, meaning in this case, utterly displaced and effaced: “Only if I can see myself in that position can I understand the crisis of that position.” That is the logic of the moral and political discourses we see every day — the need for the innocent black subject to be victimized by a racist state in order to see the racism of the racist state. You have to be exemplary in your goodness, as opposed to ...

Frank Wilderson: [laughter] A nigga on the warpath!

While I was reading the local newspaper I came across a story that caught my attention. The article was about a 17 year-old boy from Baltimore named Isaiah Simmons who died in a juvenile facility in 2007 when five to seven counselors suffocated him while restraining him for hours. After he stopped responding they dumped his body in the snow and did not call for medical assistance for over 40 minutes. In late March 2012, the case was thrown out completely and none of the counselors involved in his murder were charged with anything. The article I found online about the case was titled “Charges Dropped Against 5 In Juvenile Offender’s Death.” By emphasizing that it was a juvenile offender who died, the article is quick to flag Isaiah as a criminal, as if to signal to readers that his death is not worthy of sympathy or being taken up by civil rights activists. Every comment left on the article was crude and contemptuous — the general sentiment was that his death was no big loss to society. The news about the case being thrown out barely registered at all. There was no public outcry, no call to action, no discussion of the many issues bound up with the case — youth incarceration, racism, the privatization of prisons and jails (he died at a private facility), medical neglect, state violence, and so forth — though to be fair, there was a critical response when the case initially broke.

For weeks after reading the article I kept contemplating the question: What is the difference between Trayvon Martin and Isaiah Simmons? Which cases galvanize activists into action, and which are ignored completely? In the wake of the Jena 6, Troy Davis, Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin, and other high profile cases,1 I have taken note of the patterns that structure political appeals, particularly the way innocence becomes a necessary precondition for the launching of anti-racist political campaigns. These campaigns often center on prosecuting and harshly punishing the individuals responsible for overt and locatable acts of racist violence, thus positioning the State and the criminal justice system as an ally and protector of the oppressed. If the “innocence” of a Black victim is not established, he or she will not become a suitable spokesperson for the cause. If you are Black, have a drug felony, and are attempting to file a complaint with the ACLU regarding habitual police harassment — you are probably not going to be legally represented by them or any other civil rights organization anytime soon.2 An empathetic structure of feeling based on appeals to innocence has come to ground contemporary anti-racist politics. Within this framework, empathy can only be established when a person meets the standards of authentic victimhood and moral purity, which requires Black people, in the words of Frank Wilderson, to be shaken free of “niggerization.” Social, political, cultural, and legal recognition only happens when a person is thoroughly whitewashed, neutralized, and made unthreatening. The “spokesperson” model of doing activism (isolating specific exemplary cases) also tends to emphasize the individual, rather than the collective nature of the injury. Framing oppression in terms of individual actors is a liberal tactic that dismantles collective responses to oppression and diverts attention from the larger picture.

Using “innocence” as the foundation to address anti-Black violence is an appeal to the white imaginary, though these arguments are certainly made by people of color as well. Relying on this framework re-entrenches a logic that criminalizes race and constructs subjects as docile. A liberal politics of recognition can only reproduce a guilt-innocence schematization that fails to grapple with the fact that there is an a priori association of Blackness with guilt (criminality). Perhaps association is too generous — there is a flat-out conflation of the terms. As Frank Wilderson noted in “Gramsci’s Black Marx,” the cop’s answer to the Black subject’s question — why did you shoot me? — follows a tautology: “I shot you because you are Black; you are Black because I shot you.”3 In the words of Fanon, the cause is the consequence.4 Not only are Black men assumed guilty until proven innocent, Blackness itself is considered synonymous with guilt. Authentic victimhood, passivity, moral purity, and the adoption of a whitewashed position are necessary for recognition in the eyes of the State. Wilderson, quoting N.W.A, notes that “a nigga on the warpath” cannot be a proper subject of empathy.5 The desire for recognition compels us to be allies with, rather than enemies of the State, to sacrifice ourselves in order to meet the standards of victimhood, to throw our bodies into traffic to prove that the car will hit us rather than calling for the execution of all motorists. This is also the logic of rape revenge narratives — only after a woman is thoroughly degraded can we begin to tolerate her rage (but outside of films and books, violent women are not tolerated even when they have the “moral” grounds to fight back, as exemplified by the high rates of women who are imprisoned or sentenced to death for murdering or assaulting abusive partners).

We may fall back on such appeals for strategic reasons — to win a case or to get the public on our side — but there is a problem when our strategies reinforce a framework in which revolutionary and insurgent politics are unimaginable. I also want to argue that a politics founded on appeals to innocence is anachronistic because it does not address the transformation and re-organization of racist strategies in the post-civil rights era. A politics of innocence is only capable of acknowledging examples of direct, individualized acts of racist violence while obscuring the racism of a putatively colorblind liberalism that operates on a structural level. Posing the issue in terms of personal prejudice feeds the fallacy of racism as an individual intention, feeling or personal prejudice, though there is certain a psychological and affective dimension of racism that exceeds the individual in that it is shaped by social norms and media representations. The liberal colorblind paradigm of racism submerges race beneath the “commonsense” logic of crime and punishment. This effectively conceals racism, because it is not considered racist to be against crime. Cases like the execution of Troy Davis, where the courts come under scrutiny for racial bias, also legitimize state violence by treating such cases as exceptional. The political response to the murder of Troy Davis does not challenge the assumption that communities need to clean up their streets by rounding up criminals, for it relies on the claim that Davis is not one of those feared criminals, but an innocent Black man. Innocence, however, is just code for nonthreatening to white civil society. Troy Davis is differentiated from other Black men — the bad ones — and the legal system is diagnosed as being infected with racism, masking the fact that the legal system is the constituent mechanism through which racial violence is carried out (wishful last-minute appeals to the right to a fair trial reveal this — as if trials were ever intended to be fair!). The State is imagined to be deviating from its intended role as protector of the people, rather than being the primary perpetrator. H. Rap Brown provides a sobering reminder that, “Justice means ‘just-us-white-folks.’ There is no redress of grievance for Blacks in this country.”6