#skinner box

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Michael and Mia on prom night!!!! <3 Artwork created by @idrawprettyboys Thank you so much for all your hard work and dedication to bring these characters life from the book/ my imagination to ink lines on the page! You are simply amazing and I cannot thank you enough for this! <3

#the princess diaries#princess diaries#mia thermopolis#michael moscovitz#books#snowflakenecklace#i'm not sorry and i'll wait#ao3 fanfic#book mia thermopolis#book michael moscovitz#artwork#artists on tumblr#watercolour art#i'm not crying you're crying#prom night#skinner box#commission#meg cabot#anne hathaway#robert shwartzman

83 notes

·

View notes

Note

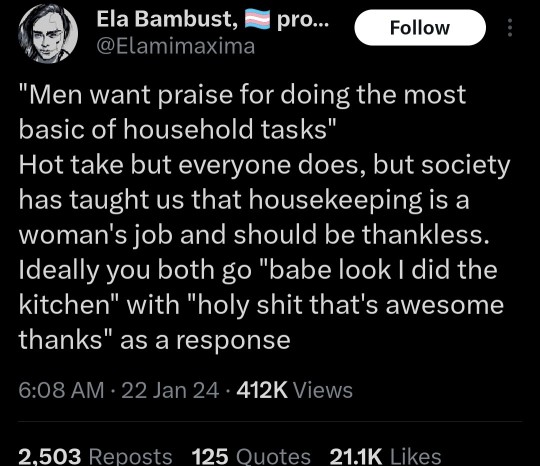

Pfff so I just scrolled your post and obvs I am not the first to tell you about blocking notifications. Hope you get that worked out soon! My other stuff about not panicing still stands tho :D

I'm more worried about this going to my head. I like knowing people are interested in what I have to say, but I'm worried I might start thinking I have to cater to an audience.

I've been spending all morning on Tumblr reacting to this. I haven't eaten and have studying I need to do

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

The people who do well on the test go to the best schools. That's why we let them in to the best schools.

This is the 3rd time I've seen someone who makes YouTube videos go mad trying to second guess "the algorithm."

YouTube provides creators with a firehose of data: How long people watch, when they stop watching, the distribution of views. YouTube also sometimes selects videos using a secret, unknowable algorithm to be "promoted." For small and medium creators this is a huge deal and the difference between 500 views and 500,000 views.

For self-critical analytical minds it's a toxic combination. Think of it this way: You have all this data to help you improve your videos, if the data meets certain criteria your video gets seen. Your video matters. For those who are trying to make a living making videos it's critical.

But, you don't know what those criteria are. Some of your videos get 100,000s of views some get only 100s. The Algorithm decides. The worst kind of boss or parent is the inconsistent, unpredictable boss who inflicts punishment or anger seemingly at random-- all making you think you ought to be able to figure out why it's happening. You keep struggling to please them, to meet their unspoken formless criteria for success. Improve your thumbnails! (by adding exaggerated faces to them) Avoid these colors. Don't forget to ask people to like and subscribe! (People really are more likely to like a video if you ask. So, you should ask because likes are a factor in the mysterious algorithm, right?)

It reminds me of standardized testing.

Why say "like and subscribe" ? Because the data from YouTube proves that when people ask they get more likes. Having a lots of likes means a video is going to be popular. If YouTube determines that a video "will" be popular then YouTube promotes the video *making* it popular. Ouroboros!

(The people who do well on this test go to the best schools. That's why we let them in to the best schools.)

It's enough to make a person crazy. Once again I'm seeing a creator I like as a person, someone who cares about science get obsessed and maybe a little delusional about little blips and kinks in the watch-time graphs for his videos.

You see suddenly "the algorithm" hasn't been boosting his videos like before. He didn't change anything the views just dropped off. And so he's looking for a reason. He is blaming himself. But... it might not be anything rational. They change the algorithm all the time. My advice is to avoid depending on YouTube (if you have the option.) It's not a good work environment.

I hope that this guy comes out of it. I'm not kidding when I've said it's driven other people mad. Like they had to get therapy because of it... which sounds funny ... until you think about what it would really be like.

Thanks for letting me share about this. It's weighing on me today--

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you are doing research about the origins of the JRPG and you find out Dragon quest was solely created to boost shonen jump magazine sales:

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Product design and psychology: The Mechanism of Skinner Box Techniques in Video Game Design

Keywords: Skinner Box, Video Gaming, Game Design, Operant Conditioning, Reward

Abstract:

This paper discusses the application of B.F. Skinner's operant conditioning framework, colloquially known as the Skinner Box mechanism, in the domain of modern video gaming. As a pivotal tool of psychological manipulation, this method has been integral in influencing player behaviour and engagement. Various case studies and examples are presented to provide a comprehensive understanding of its usage in game design.

Introduction:

The digital gaming industry has seen an unprecedented growth trajectory, fuelled by the increasing ubiquity of devices and the inherent human predilection towards engaging, interactive, and rewarding experiences. One psychological technique that has been instrumental in fostering these experiences is B.F. Skinner's operant conditioning principle. The primary objective of this paper is to delve into the specifics of the Skinner Box mechanism in video gaming, highlighting its implications from a product designer's perspective.

Skinner Box in Gaming: Conceptualization and Design

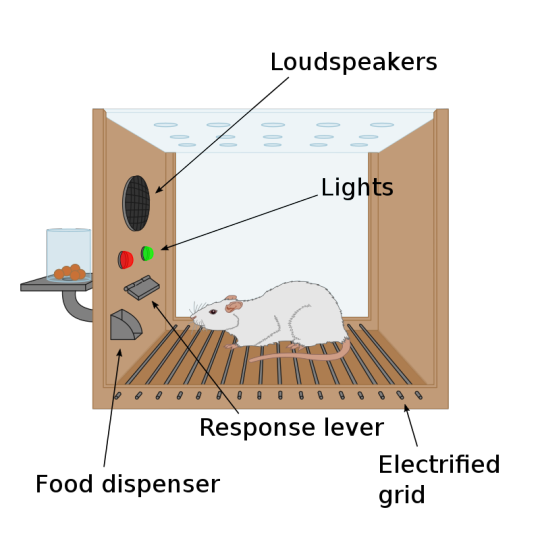

B.F. Skinner's operant conditioning theory revolves around the basic premise of reward and punishment. In a Skinner Box experiment, a rat is rewarded or punished based on its interaction with the environment. This principle, when mapped onto the gaming arena, translates into a design where player actions result in rewards or penalties, shaping subsequent behaviour.

The implementation of the Skinner Box mechanism varies greatly, from straightforward reward systems to intricate loot box mechanisms. For instance, in games like World of Warcraft, players are motivated to continue playing by the promise of levelling up or acquiring rare items, a phenomenon akin to the random reinforcement schedules of Skinner's experiments.

The effective use of the Skinner Box mechanism relies on the careful calibration of reward frequency and intensity. The random reinforcement schedule, akin to a slot machine's unpredictability, plays a pivotal role in maintaining player engagement and addiction. The concept of 'grinding' or performing repetitive tasks for rewards is a prime example of this method.

Case Study: Clash of Clans

Supercell's Clash of Clans offers an instructive example of the Skinner Box principle. Players are rewarded for attacking other players' bases, and these rewards can be used to upgrade their own base, troops, and defences. The time it takes to build and upgrade structures creates a variable ratio schedule of reinforcement that encourages regular engagement. A player might decide to continue playing, anticipating a shorter wait time or a more generous loot after an attack.

Case Study: Candy Crush Saga

King's Candy Crush Saga epitomizes the use of the Skinner Box mechanism through its reward system. As players progress through the levels, they receive varied types of reinforcement: unlocking new levels (positive reinforcement), losing lives for failed attempts (negative punishment), or gaining additional moves to complete a level (negative reinforcement). The unpredictability of rewards creates an intriguing suspense, impelling players to continue their interaction with the game.

Implications for Game Design

As a senior product designer, understanding the dynamics of the Skinner Box mechanism is crucial. The technique's potency lies in its ability to encourage player engagement, foster addiction, and influence in-game purchasing decisions. However, the ethical dimensions of this tool warrant careful consideration. Game designers must strike a delicate balance between maintaining player engagement and avoiding exploitative practices.

Conclusion

The Skinner Box mechanism has emerged as a powerful tool in the hands of game designers, helping sculpt player behaviour in a predictable manner. However, it is paramount for designers to consider the ethical implications of their design choices, ensuring their strategies promote a healthy and enjoyable gaming experience. As the digital gaming industry continues to evolve, it will be interesting to see how Skinner's principles continue to be integrated and innovated upon.

References:

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The Behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York: Appleton-Century.

Zichermann, G., & Cunningham, C. (2011). Gamification by design: Implementing game mechanics in web and mobile apps. O'Reilly Media, Inc.

Eyal, N. (2014). Hooked: How to build habit-forming products. Penguin.

Hamari, J., & Keronen, L. (2017). Why do people buy virtual goods? Attitude towards virtual good purchases versus game enjoyment. International Journal of Information Management, 37(3), 299-308.

Przybylski, A. K., Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). A motivational model of video game engagement. Review of General Psychology, 14(2), 154–166.

King, D., & Delfabbro, P. (2019). The concept of “harm” in Internet gaming disorder. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(3), 456–468.

Koster, R. (2013). Theory of Fun for Game Design. O'Reilly Media.

Madigan, J. (2015). Getting Gamers: The Psychology of Video Games and Their Impact on the People who Play Them. Rowman & Littlefield.

Fizek, S. (2018). Why Fun Matters: In Search of Emergent Playful Experiences. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(5), 950-961.

Smith, S. L., & Toscano, A. J. (2016). Children's and adolescents' cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to reward-related, child-targeted mobile applications. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(7), 441-447.

Chou, Y. K. (2015). Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards. Octalysis Media.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining gamification. Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments, 9-15.

Supercell. (2012). Clash of Clans. [Video Game]. Helsinki, Finland.

King. (2012). Candy Crush Saga. [Video Game]. Stockholm, Sweden.

Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2014). Demographic differences in perceived benefits from gamification. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 179-188.

Alha, K., Koskinen, E., Paavilainen, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). Why do people play location-based augmented reality games? A study on Pokémon GO. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 35(9), 804-819.

#skinner box#video games#game design#user experience#user engagement#product design#psychological manipulation#gaming#operant conditioning#clash of clans#candy crush#gamers

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

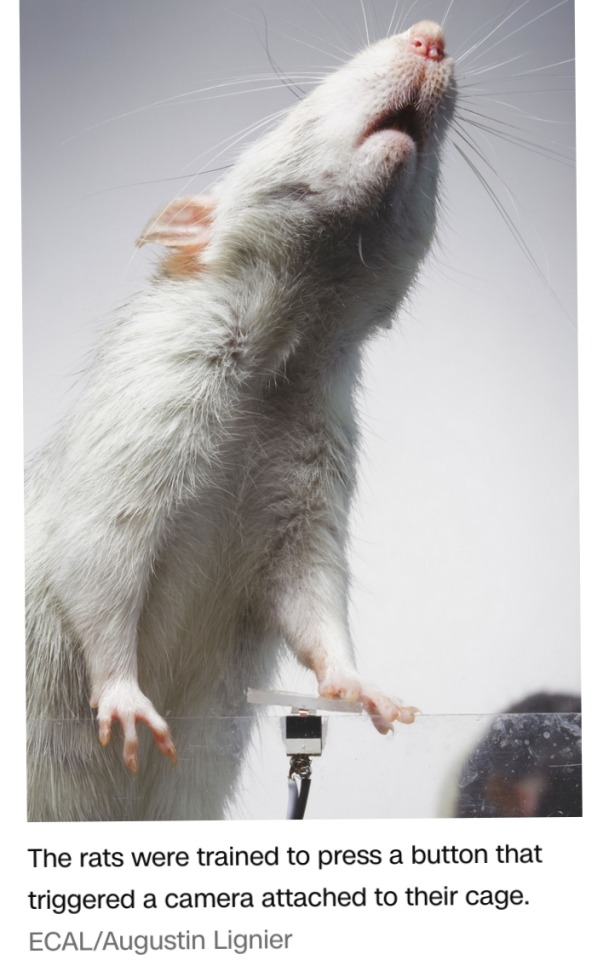

🩶🐀🩶

#rats#selfies#Augustin Lignier#rodents#Skinner Box#B.F Skinner#animal behavior#Augustin#Arthur#headshot#sugar#dopamine#say cheese#camera#photography

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

How they see us.

But we don't even get a treat.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are Players Too Award-Focused?

So, let’s skip the usual preamble and just dive in. What is award-focused? Well, presumably, it is a mercenary attitude in videogaming where a player will not do something unless a tangible award is at the other end. This could be at the end of a quest, or a long arduous set of events that leads to an award. Or it could simply be killing an NPC because they got good stuff, if you are a complete psychopath.

This has come up in MMO circles a number of times. Namely, the “Josh Strife Says” video on MMO Doomscrolling. In this stream, Josh makes the point for level scaling players in MMO, down scaling them, in order for them to participate with lower level friends without outright carrying the whole task. His friend, Callum Upton, states that there is no award or purpose to that. That there is no tangible award, and therefore players won’t do that. He also argues that it has the other effect of making a player’s level “meaningless”. The “award” he argues is being able to one shot any enemy in a given area.

So, to counter point Callum’s argument, the level objectively is not meaningless. To give an example, Guild Wars 2 does level you DOWN to an area in raw stat points and numbers. However, you still carry the abilities and manuevers to you unlocked via leveling up. In Elder Scrolls Online, everyone is basically at the same base power range, but, again, your abilities and tricks and other things you have unlocked makes leveling up meaningful.

Second counter point, bulldozing enemies is, frankly, kind of boring. You have all these abilities for spell interruption, defense debuffs, buffs for yourself, speed and so on. But those become utterly pointless if you’re one shotting enemies. Therefore, you’re “award” is just boring gameplay where nothing challenges you. A good RPG, in my mind, is strategic, requiring you to think, not just plow through.

Side note: I do respect Callum Upton. He is a game designer with experience I likely will never have and he is one of many people doing good work calling out the crypto-bros for their collective bullshit. I recommend his channel wholeheartedly.

But the point I��m trying to illustrate here is the overt focus on some kind of objective award gets in the way of what is supposed to make an MMO fun: Playing with friends in a fantasy world. A friend of mine, once she is done with her dissertation, is planning on getting back into ESO, and I’m excited because it is a game where I already have a character and it does not matter what level she is. I can just do whatever she is doing. Being at max level, with only the Champion Point system giving me anymore buffs, I’m not really looking for a new item anymore. I just want some friends to play with.

And my motivation for going into ESO was never the big weapons or whatever. My goals are thus: 1) Creating a character through look and ability so I can dream up a narrative in my head between him and the main story 2) See the story to its end, 3) Enjoy the combat and some bosses, 4) Do the dungeon raids because they are just good loud fun 5) Check out Tamriel from a time before the “main series”.

Now, I’m NOT saying I’m looking for NO tangible awards. Obviously, I want my equipment to keep up in order to do all those things, but that is a means to an end, not the award I’m shooting for. And little things I would like come up here and there. I wanted my first character, a battlemage take on the Sorcerer class, to have a daedric greatsword. And not just any daedric greatsword: The best I could conjure up. It’s not part of an equipment set, but I cherish that sword because of what it represents: The character’s mastery of sword combat and daedric arts.

Are there better weapons? Probably, if I dig deep enough, there is a more fitting weapon for my build. But the game, for what I’m trying to do, does not require that my numbers are absolute tip top. For me, what is more important, is the look and feel of the character, and part of that is the weapon he uses. For now, I am more interested in how any given story plays out along with the gameplay that comes with it.

But then comes another question: am I still being award focused? After all, I’m expecting SOMETHING on the other end of what I’m doing. I want to play as a hero in a fantasy setting, and I want at least a fitting end to the adventure. I want to see new sites, fun characters and a good note to end a character’s narrative on. I want to see the legendary items and weapons, even if the numbers behind them hold little meaning to me.

I put up with this grind once, redoing dungeons to get the right equipment (the right award) for the Raid Finder during WoW’s Cataclysm expansion. And to be honest, it was the worst part of that whole experience. Dungeons were still fun for the madness that can occur, but it also became infuriating because there were no more sidequests to break them up. Once I GOT to the Raids via the Raid Finder, it was a blast. I threw on my Nightwish playlist and then, during the last Deathwing section, threw on their song “Fantasmic”. There is very little that can top stuffing a giant death dragon into the abyss to symphonic metal. It was such an end, that I knew I could not top it, and so with that, plus my blooming relationship at the time, I decided that was the end of the story. Further experiences in games have veered me away from that game ever since. But my point is that the number crunching award system was a means to see the big ending, not because I needed the Deathwing Axe and it’s accompanying dagger.

(Side note: I lucked out and got both in the same loot role. So not only did I help save the world, I managed to piss off 24 WoW players in the process. It was an objectively complete victory.)

Perhaps it is more a question of what motivates you. If you do not care for number crunching, World of Warcraft is not the game for you. I’ve heard people say that the constant build of numbers is part of the fantasy, and I guess it is not my place to naysay them. I want story completion, character arcs (even if they are just mostly in my head), cool weapons because of what they are and not because of numbers, and nice scenery. Perhaps I am setting/story motivated rather than numbers motivated?

Yet, there is another part of the constant award that does not sit well with me. In short, it is abusive. In length, the constant skinner box design of games abuses award addiction. It encourages the tossing out of relatively new gear for SLIGHTLY newer gear because of a value that the developers just, well, MADE UP. As I have said before, there is literally no mechanical difference between using a level 5 knife in WoW versus a level 30 short sword. The actions will remain the same. The award is not so much a new toy to play with, but a slight variation of the SAME toy. The backstory weapon/armor is meaningless next to its numbers.

The other problem, as illustrated in Folding Idea’s video: Why It's Rude to Suck at Warcraft. Because everyone is so performance focused with their numbers, the world might as well not be there. The design of WoW is so numbers focused that it became more optimal to have the graphical settings as low as possible to not have any distractions. So art assets that a whole team put a lot of work into basically gets tossed out the window because of how the game was designed. The world might as well be a blank page.

And that is what this kind of number crunch boils things down to: A blank page covered in numbers. Why even have the world at all? This is why the constant focus on “objective number awards” disgusts me. The fantasy is gone, and just numbers. The same numbers at your desk at work. The same numbers a bunch of CEO ghouls want you to keep increasing. Just numbers and numbers and numbers, in order to get higher numbers and numbers and numbers.

Forget the actual lore of Azeroth. Forget the characters and motivations. Forget the music. Forget the artwork. Forget story telling. Everything is just numbers.

But here’s the ultimate kicker: Players are enabling this design. It is a constant cycle of addict and drug dealer mentality. There’s a bit of “chicken-and-egg” here: We are told from birth that having more is better. So games are designed that way, and therefore encourage that behavior. And need I go over how toxic their relationship with other players can get, all for the sake of “optimization”? It is a constant pissing contest over made up value. It is an excuse for this award system to keep going.

For players, I encourage that you step back from the usual number crunch, skinner boxes and whatnot and really ask yourself the following questions:

- Why did I play this game in the first place? - Am I still having fun? - Do I understand the greater context?

This is a conversation we need to have, because I suspect the awards have become poison. Poison to us as players, the worlds we play in and the stories we witness.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happiness begets more happiness.

Depression begets more depression.

Happy people don't need to tune out with alcohol, drugs or skinner boxes.

“Get a rat and put it in a cage and give it two water bottles. One is just water, and one is water laced with either heroin or cocaine. If you do that, the rat will almost always prefer the drugged water and almost always kill itself very quickly, right, within a couple of weeks. So there you go. It’s our theory of addiction. Bruce comes along in the ’70s and said, “Well, hang on a minute. We’re putting the rat in an empty cage. It’s got nothing to do. Let’s try this a little bit differently.” So Bruce built Rat Park, and Rat Park is like heaven for rats. Everything your rat about town could want, it’s got in Rat Park. It’s got lovely food. It’s got sex. It’s got loads of other rats to be friends with. It’s got loads of colored balls. Everything your rat could want. And they’ve got both the water bottles. They’ve got the drugged water and the normal water. But here’s the fascinating thing. In Rat Park, they don’t like the drugged water. They hardly use any of it. None of them ever overdose. None of them ever use in a way that looks like compulsion or addiction. There’s a really interesting human example I’ll tell you about in a minute, but what Bruce says is that shows that both the right-wing and left-wing theories of addiction are wrong. So the right-wing theory is it’s a moral failing, you’re a hedonist, you party too hard. The left-wing theory is it takes you over, your brain is hijacked. Bruce says it’s not your morality, it’s not your brain; it’s your cage. Addiction is largely an adaptation to your environment. […] We’ve created a society where significant numbers of our fellow citizens cannot bear to be present in their lives without being drugged, right? We’ve created a hyperconsumerist, hyperindividualist, isolated world that is, for a lot of people, much more like that first cage than it is like the bonded, connected cages that we need. The opposite of addiction is not sobriety. The opposite of addiction is connection. And our whole society, the engine of our society, is geared towards making us connect with things. If you are not a good consumer capitalist citizen, if you’re spending your time bonding with the people around you and not buying stuff—in fact, we are trained from a very young age to focus our hopes and our dreams and our ambitions on things we can buy and consume. And drug addiction is really a subset of that.”

—

Johann Hari,

Does Capitalism Drive Drug Addiction?

(via bigfatsun)

338K notes

·

View notes

Text

Why am I so obsessed?!!! I must admit, Michael (movie version) isn't nearly as dreamy, but knowing how he is in the books, he makes my heart melt!!!

#the princess diaries#princess diaries#mia thermopolis#michael moscovitz#books#movies#anne hathaway#dream boy#skinner box#he plays guitar#and he can sing. He is so hot!"

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gig apps trap reverse centaurs in Skinner boxes

Enshittification is the process by which digital platforms devour themselves: first they dangle goodies in front of end users. Once users are locked in, the goodies are taken away and dangled before business customers who supply goods to the users. Once those business customers are stuck on the platform, the goodies are clawed away and showered on the platform’s shareholders:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/#hey-guys

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/12/algorithmic-wage-discrimination/#fishers-of-men

Enshittification isn’t just another way of saying “fraud” or “price gouging” or “wage theft.” Enshittification is intrinsically digital, because moving all those goodies around requires the flexibility that only comes with a digital businesses. Jeff Bezos, grocer, can’t rapidly change the price of eggs at Whole Foods without an army of kids with pricing guns on roller-skates. Jeff Bezos, grocer, can change the price of eggs on Amazon Fresh just by twiddling a knob on the service’s back-end.

Twiddling is the key to enshittification: rapidly adjusting prices, conditions and offers. As with any shell game, the quickness of the hand deceives the eye. Tech monopolists aren’t smarter than the Gilded Age sociopaths who monopolized rail or coal — they use the same tricks as those monsters of history, but they do them faster and with computers:

https://doctorow.medium.com/twiddler-1b5c9690cce6

If Rockefeller wanted to crush a freight company, he couldn’t just click a mouse and lay down a pipeline that ran on the same route, and then click another mouse to make it go away when he was done. When Bezos wants to bankrupt Diapers.com — a company that refused to sell itself to Amazon — he just moved a slider so that diapers on Amazon were being sold below cost. Amazon lost $100m over three months, diapers.com went bankrupt, and every investor learned that competing with Amazon was a losing bet:

https://slate.com/technology/2013/10/amazon-book-how-jeff-bezos-went-thermonuclear-on-diapers-com.html

That’s the power of twiddling — but twiddling cuts both ways. The same flexibility that digital businesses enjoy is hypothetically available to workers and users. The airlines pioneered twiddling ticket prices, and that naturally gave rise to countertwiddling, in the form of comparison shopping sites that scraped the airlines’ sites to predict when tickets would be cheapest:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/27/knob-jockeys/#bros-be-twiddlin

The airlines — like all abusive businesses — refused to tolerate this. They were allowed to touch their knobs as much as they wanted — indeed, they couldn’t stop touching those knobs — but when we tried to twiddle back, that was “felony contempt of business model,” and the airlines sued:

https://www.cnbc.com/2014/12/30/airline-sues-man-for-founding-a-cheap-flights-website.html

And sued:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/06/business/southwest-airlines-lawsuit-prices.html

Platforms don’t just hate it when end-users twiddle back — if anything they are even more aggressive when their business-users dare to twiddle. Take Para, an app that Doordash drivers used to get a peek at the wages offered for jobs before they accepted them — something that Doordash hid from its workers. Doordash ruthlessly attacked Para, saying that by letting drivers know how much they’d earn before they did the work, Para was violating the law:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/tech-rights-are-workers-rights-doordash-edition

Which law? Well, take your pick. The modern meaning of “IP” is “any law that lets me use the law to control my competitors, competition or customers.” Platforms use a mix of anticircumvention law, patent, copyright, contract, cybersecurity and other legal systems to weave together a thicket of rules that allow them to shut down rivals for their Felony Contempt of Business Model:

https://locusmag.com/2020/09/cory-doctorow-ip/

Enshittification relies on unlimited twiddling (by platforms), and a general prohibition on countertwiddling (by platform users). Enshittification is a form of fishing, in which bait is dangled before different groups of users and then nimbly withdrawn when they lunge for it. Twiddling puts the suppleness into the enshittifier’s fishing-rod, and a ban on countertwiddling weighs down platform users so they’re always a bit too slow to catch the bait.

Nowhere do we see twiddling’s impact more than in the “gig economy,” where workers are misclassified as independent contractors and put to work for an app that scripts their every move to the finest degree. When an app is your boss, you work for an employer who docks your pay for violating rules that you aren’t allowed to know — and where your attempts to learn those rules are constantly frustrated by the endless back-end twiddling that changes the rules faster than you can learn them.

As with every question of technology, the issue isn’t twiddling per se — it’s who does the twiddling and who gets twiddled. A worker armed with digital tools can play gig work employers off each other and force them to bid up the price of their labor; they can form co-ops with other workers that auto-refuse jobs that don’t pay enough, and use digital tools to organize to shift power from bosses to workers:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/12/02/not-what-it-does/#who-it-does-it-to

Take “reverse centaurs.” In AI research, a “centaur” is a human assisted by a machine that does more than either could do on their own. For example, a chess master and a chess program can play a better game together than either could play separately. A reverse centaur is a machine assisted by a human, where the machine is in charge and the human is a meat-puppet.

Think of Amazon warehouse workers wearing haptic location-aware wristbands that buzz at them continuously dictating where their hands must be; or Amazon drivers whose eye-movements are continuously tracked in order to penalize drivers who look in the “wrong” direction:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/17/reverse-centaur/#reverse-centaur

The difference between a centaur and a reverse centaur is the difference between a machine that makes your life better and a machine that makes your life worse so that your boss gets richer. Reverse centaurism is the 21st Century’s answer to Taylorism, the pseudoscience that saw white-coated “experts” subject workers to humiliating choreography down to the smallest movement of your fingertip:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/08/21/great-taylors-ghost/#solidarity-or-bust

While reverse centaurism was born in warehouses and other company-owned facilities, gig work let it make the leap into workers’ homes and cars. The 21st century has seen a return to the cottage industry — a form of production that once saw workers labor far from their bosses and thus beyond their control — but shriven of the autonomy and dignity that working from home once afforded:

https://doctorow.medium.com/gig-work-is-the-opposite-of-steampunk-463e2730ef0d

The rise and rise of bossware — which allows for remote surveillance of workers in their homes and cars — has turned “work from home” into “live at work.” Reverse centaurs can now be chickenized — a term from labor economics that describes how poultry farmers, who sell their birds to one of three vast poultry processors who have divided up the country like the Pope dividing up the “New World,” are uniquely exploited:

https://onezero.medium.com/revenge-of-the-chickenized-reverse-centaurs-b2e8d5cda826

A chickenized reverse centaur has it rough: they must pay for the machines they use to make money for their bosses, they must obey the orders of the app that controls their work, and they are denied any of the protections that a traditional worker might enjoy, even as they are prohibited from deploying digital self-help measures that let them twiddle back to bargain for a better wage.

All of this sets the stage for a phenomenon called algorithmic wage discrimination, in which two workers doing the same job under the same conditions will see radically different payouts for that work. These payouts are continuously tweaked in the background by an algorithm that tries to predict the minimum sum a worker will accept to remain available without payment, to ensure sufficient workers to pick up jobs as they arise.

This phenomenon — and proposed policy and labor solutions to it — is expertly analyzed in “On Algorithmic Wage Discrimination,” a superb paper by UC Law San Franciscos Veena Dubal:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4331080

Dubal uses empirical data and enthnographic accounts from Uber drivers and other gig workers to explain how endless, self-directed twiddling allows gig companies pay workers less and pay themselves more. As @[email protected] explains in his LA Times article on Dubal’s research, the goal of the payment algorithm is to guess how often a given driver needs to receive fair compensation in order to keep them driving when the payments are unfair:

https://www.latimes.com/business/technology/story/2023-04-11/algorithmic-wage-discrimination

The algorithm combines nonconsensual dossiers compiled on individual drivers with population-scale data to seek an equilibrium between keeping drivers waiting, unpaid, for a job; and how much a driver needs to be paid for an individual job, in order to keep that driver from clocking out and doing something else. @ Here’s how that works. Sergio Avedian, a writer for The Rideshare Guy, ran an experiment with two brothers who both drove for Uber; one drove a Tesla and drove intermittently, the other brother rented a hybrid sedan and drove frequently. Sitting side-by-side with the brothers, Avedian showed how the brother with the Tesla was offered more for every trip:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UADTiL3S67I

Uber wants to lure intermittent drivers into becoming frequent drivers. Uber doesn’t pay for an oversupply of drivers, because it only pays drivers when they have a passenger in the car. Having drivers on call — but idle — is a way for Uber to shift the cost of maintaining a capacity cushion to its workers.

What’s more, what Uber charges customers is not based on how much it pays its workers. As Uber’s head of product explained: Uber uses “machine-learning techniques to estimate how much groups of customers are willing to shell out for a ride. Uber calculates riders’ propensity for paying a higher price for a particular route at a certain time of day. For instance, someone traveling from a wealthy neighborhood to another tony spot might be asked to pay more than another person heading to a poorer part of town, even if demand, traffic and distance are the same.”

https://qz.com/990131/uber-is-practicing-price-discrimination-economists-say-that-might-not-be-a-bad-thing/

Uber has historically described its business a pure supply-and-demand matching system, where a rush of demand for rides triggers surge pricing, which lures out drivers, which takes care of the demand. That’s not how it works today, and it’s unclear if it ever worked that way. Today, a driver who consults the rider version of the Uber app before accepting a job — to compare how much the rider is paying to how much they stand to earn — is booted off the app and denied further journeys.

Surging, instead, has become just another way to twiddle drivers. One of Dubal’s subjects, Derrick, describes how Uber uses fake surges to lure drivers to airports: “You go to the airport, once the lot get kind of full, then the surge go away.” Other drivers describe how they use groupchats to call out fake surges: “I’m in the Marina. It’s dead. Fake surge.”

That’s pure twiddling. Twiddling turns gamification into gamblification, where your labor buys you a spin on a roulette wheel in a rigged casino. As a driver called Melissa, who had doubled down on her availability to earn a $100 bonus awarded for clocking a certain number of rides, told Dubal, “When you get close to the bonus, the rides start trickling in more slowly…. And it makes sense. It’s really the type of shit that they can do when it’s okay to have a surplus labor force that is just sitting there that they don’t have to pay for.”

Wherever you find reverse-centaurs, you get this kind of gamblification, where the rules are twiddled continuously to make sure that the house always wins. As a contract driver Amazon reverse centaur told Lauren Gurley for Motherboard, “Amazon uses these cameras allegedly to make sure they have a safer driving workforce, but they’re actually using them not to pay delivery companies”:

https://www.vice.com/en/article/88npjv/amazons-ai-cameras-are-punishing-drivers-for-mistakes-they-didnt-make

Algorithmic wage discrimination is the robot overlord of our nightmares: its job is to relentlessly quest for vulnerabilities and exploit them. Drivers divide themselves into “ants” (drivers who take every job) and “pickers” (drivers who cherry-pick high-paying jobs). The algorithm’s job is ensuring that pickers get the plum assignments, not the ants, in the hopes of converting those pickers to app-dependent ants.

In my work on enshittification, I call this the “giant teddy bear” gambit. At every county fair, you’ll always spot some poor jerk carrying around a giant teddy-bear they “won” on the midway. But they didn’t win it — not by getting three balls in the peach-basket. Rather, the carny running the rigged game either chose not to operate the “scissor” that kicks balls out of the basket. Or, if the game is “honest” (that is, merely impossible to win, rather than gimmicked), the operator will make a too-good-to-refuse offer: “Get one ball in and I’ll give you this keychain. Win two keychains and I’ll let you trade them for this giant teddy bear.”

Carnies aren’t in the business of giving away giant teddy bears — rather, the gambit is an investment. Giving a mark a giant teddy bear to carry around the midway all day acts as a convincer, luring other marks to try to land three balls in the basket and win their own teddy bear.

In the same way, platforms like Uber distribute giant teddy bears to pickers, as a way of keeping the ants scurrying from job to job, and as a way of convincing the pickers to give up whatever work allows them to discriminate among Uber’s offers and hold out for the plum deals, whereupon then can be transmogrified into ants themselves.

Dubal describes the experience of Adil, a Syrian refugee who drives for Uber in the Bay Area. His colleagues are pickers, and showed him screenshots of how much they earned. Determined to get a share of that money, Adil became a model ant, driving two hours to San Francisco, driving three days straight, napping in his car, spending only one day per week with his family. The algorithm noticed that Adil needed the work, so it paid him less.

Adil responded the way the system predicted he would, by driving even more: “My friends they make it, so I keep going, maybe I can figure it out. It’s unsecure, and I don’t know how people they do it. I don’t know how I am doing it, but I have to. I mean, I don’t find another option. In a minute, if I find something else, oh man, I will be out immediately. I am a very patient person, that’s why I can continue.”

Another driver, Diego, told Dubal about how the winners of the giant teddy bears fell into the trap of thinking that they were “good at the app”: “Any time there’s some big shot getting high pay outs, they always shame everyone else and say you don’t know how to use the app. I think there’s secret PR campaigns going on that gives targeted payouts to select workers, and they just think it’s all them.”

That’s the power of twiddling: by hoarding all the flexibility offered by digital tools, the management at platforms can become centaurs, able to string along thousands of workers, while the workers are reverse-centaurs, puppeteered by the apps.

As the example of Adil shows, the algorithm doesn’t need to be very sophisticated in order to figure out which workers it can underpay. The system automates the kind of racial and gender discrimination that is formally illegal, but which is masked by the smokescreen of digitization. An employer who systematically paid women less than men, or Black people less than white people, would be liable to criminal and civil sanctions. But if an algorithm simply notices that people who have fewer job prospects drive more and will thus accept lower wages, that’s just “optimization,” not racism or sexism.

This is the key to understanding the AI hype bubble: when ghouls from multinational banks predict 13 trillion dollar markets for “AI,” what they mean is that digital tools will speed up the twiddling and other wage-suppression techniques to transfer $13T in value from workers and consumers to shareholders.

The American business lobby is relentlessly focused on the goal of reducing wages. That’s the force behind “free trade,” “right to work,” and other codewords for “paying workers less,” including “gig work.” Tech workers long saw themselves as above this fray, immune to labor exploitation because they worked for a noble profession that took care of its own.

But the epidemic of mass tech-worker layoffs, following on the heels of massive stock buybacks, has demonstrated that tech bosses are just like any other boss: willing to pay as little as they can get away with, and no more. Tech bosses are so comfortable with their market dominance and the lock-in of their customers that they are happy to turn out hundreds of thousands of skilled workers, convinced that the twiddling systems they’ve built are the kinds of self-licking ice-cream cones that are so simple even a manager can use them — no morlocks required.

The tech worker layoffs are best understood as an all-out war on tech worker morale, because that morale is the source of tech workers’ confidence and thus their demands for a larger share of the value generated by their labor. The current tech layoff template is very different from previous tech layoffs: today’s layoffs are taking place over a period of months, long after they are announced, and laid off tech worker is likely to be offered a months of paid post-layoff work, rather than severance. This means that tech workplaces are now haunted by the walking dead, workers who have been laid off but need to come into the office for months, even as the threat of layoffs looms over the heads of the workers who remain. As an old friend, recently laid off from Microsoft after decades of service, wrote to me, this is “a new arrow in the quiver of bringing tech workers to heel and ensuring that we’re properly thankful for the jobs we have (had?).”

Dubal is interested in more than analysis, she’s interested in action. She looks at the tactics already deployed by gig workers, who have not taken all this abuse lying down. Workers in the UK and EU organized through Worker Info Exchange and the App Drivers and Couriers Union have used the GDPR (the EU’s privacy law) to demand “algorithmic transparency,” as well as access to their data. In California, drivers hope to use similar provisions in the CCPA (a state privacy law) to do the same.

These efforts have borne fruit. When Cornell economists, led by Louis Hyman, published research (paid for by Uber) claiming that Uber drivers earned an average of $23/hour, it was data from these efforts that revealed the true average Uber driver’s wage was $9.74. Subsequent research in California found that Uber drivers’ wage fell to $6.22/hour after the passage of Prop 22, a worker misclassification law that gig companies spent $225m to pass, only to have the law struck down because of a careless drafting error:

https://www.latimes.com/california/newsletter/2021-08-23/proposition-22-lyft-uber-decision-essential-california

But Dubal is skeptical that data-coops and transparency will achieve transformative change and build real worker power. Knowing how the algorithm works is useful, but it doesn’t mean you can do anything about it, not least because the platform owners can keep touching their knobs, twiddling the payout schedule on their rigged slot-machines.

Data co-ops start from the proposition that “data extraction is an inevitable form of labor for which workers should be remunerated.” It makes on-the-job surveillance acceptable, provided that workers are compensated for the spying. But co-ops aren’t unions, and they don’t have the power to bargain for a fair price for that data, and coops themselves lack the vast resources — “to store, clean, and understand” — data.

Co-ops are also badly situated to understand the true value of the data that is extracted from their members: “Workers cannot know whether the data collected will, at the population level, violate the civil rights of others or amplifies their own social oppression.”

Instead, Dubal wants an outright, nonwaivable prohibition on algorithmic wage discrimination. Just make it illegal. If firms cannot use gambling mechanisms to control worker behavior through variable pay systems, they will have to find ways to maintain flexible workforces while paying their workforce predictable wages under an employment model. If a firm cannot manage wages through digitally-determined variable pay systems, then the firm is less likely to employ algorithmic management.”

In other words, rather than using market mechanisms too constrain platform twiddling, Dubal just wants to make certain kinds of twiddling illegal. This is a growing trend in legal scholarship. For example, the economist Ramsi Woodcock has proposed a ban on surge pricing as a per se violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act:

https://ilr.law.uiowa.edu/print/volume-105-issue-4/the-efficient-queue-and-the-case-against-dynamic-pricing

Similarly, Dubal proposes that algorithmic wage discrimination violates another antitrust law: the Robinson-Patman Act, which “bans sellers from charging competing buyers different prices for the same commodity. Robinson-Patman enforcement was effectively halted under Reagan, kicking off a host of pathologies, like the rise of Walmart:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/03/27/walmarts-jackals/#cheater-sizes

I really liked Dubal’s legal reasoning and argument, and to it I would add a call to reinvigorate countertwiddling: reforming laws that get in the way of workers who want to reverse-engineer, spoof, and control the apps that currently control them. Adversarial interoperability (AKA competitive compatibility or comcom) is key tool for building worker power in an era of digital Taylorism:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/10/adversarial-interoperability

To see how that works, look to other jursidictions where workers have leapfrogged their European and American cousins, such as Indonesia, where gig workers and toolsmiths collaborate to make a whole suite of “tuyul apps,” which let them override the apps that gig companies expect them to use.

https://pluralistic.net/2021/07/08/tuyul-apps/#gojek

For example, ride-hailing companies won’t assign a train-station pickup to a driver unless they’re circling the station — which is incredibly dangerous during the congested moments after a train arrives. A tuyul app lets a driver park nearby and then spoof their phone’s GPS fix to the ridehailing company so that they appear to be right out front of the station.

In an ideal world, those workers would have a union, and be able to dictate the app’s functionality to their bosses. But workers shouldn’t have to wait for an ideal world: they don’t just need jam tomorrow — they need jam today. Tuyul apps, and apps like Para, which allow workers to extract more money under better working conditions, are a prelude to unionization and employer regulation, not a substitute for it.

Employers will not give workers one iota more power than they have to. Just look at the asymmetry between the regulation of union employees versus union busters. Under US law, employees of a union need to account for every single hour they work, every mile they drive, every location they visit, in public filings. Meanwhile, the union-busting industry — far larger and richer than unions — operate under a cloak of total secrecy, Workers aren’t even told which union busters their employers have hired — let alone get an accounting of how those union busters spend money, or how many of them are working undercover, pretending to be workers in order to sabotage the union.

Twiddling will only get an employer so far. Twiddling — like all “AI” — is based on analyzing the past to predict the future. The heuristics an algorithm creates to lure workers into their cars can’t account for rapid changes in the wider world, which is why companies who relied on “AI” scheduling apps (for example, to prevent their employees from logging enough hours to be entitled to benefits) were caught flatfooted by the Great Resignation.

Workers suddenly found themselves with bargaining power thanks to the departure of millions of workers — a mix of early retirees and workers who were killed or permanently disabled by covid — and they used that shortage to demand a larger share of the fruits of their labor. The outraged howls of the capital class at this development were telling: these companies are operated by the kinds of “capitalists” that MLK once identified, who want “socialism for the rich and rugged individualism for the poor.”

https://twitter.com/KaseyKlimes/status/821836823022354432/

There's only 5 days left in the Kickstarter campaign for the audiobook of my next novel, a post-cyberpunk anti-finance finance thriller about Silicon Valley scams called Red Team Blues. Amazon's Audible refuses to carry my audiobooks because they're DRM free, but crowdfunding makes them possible.

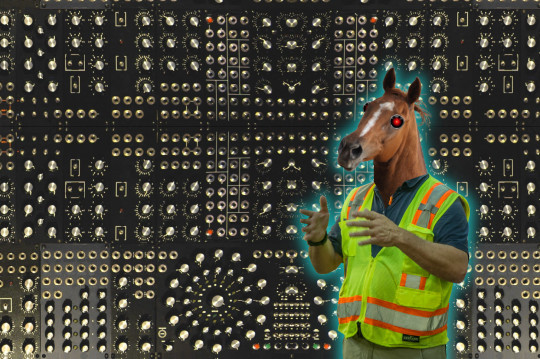

Image: Stephen Drake (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Analog_Test_Array_modular_synth_by_sduck409.jpg

CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

—

Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

—

Louis (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chestnut_horse_head,_all_excited.jpg

CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en

[Image ID: A complex mandala of knobs from a modular synth. In the foreground, limned in a blue electric halo, is a man in a hi-viz vest with the head of a horse. The horse's eyes have been replaced with the sinister red eyes of HAL9000 from Kubrick's '2001: A Space Odyssey.'"]

#pluralistic#great resignation#twiddler#countertwiddling#wage discrimination#algorithmic#scholarship#doordash#para#Veena Dubal#labor#brian merchant#app boss#reverse centaurs#skinner boxes#enshittification#ants vs pickers#tuyul#steampunk#cottage industry#ccpa#gdpr#App Drivers and Couriers Union#shitty technology adoption curve#moral economy#gamblification#casinoization#taylorization#taylorism#giant teddy bears

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

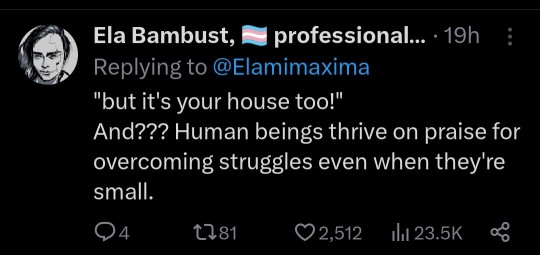

Second tweet reminds me of what I read in a psychology book. B.F. Skinner, behaviorist who make the 'Skinner Box' used for testing rats' behavior, did a study on what type of praise during some sort of assignment is ideal. He found that kids work better with constant, small praise throughout the whole assignment than a huge praise afterwords like a good grade. Isn't that crazy though?

Istg if I had the book, I'd quote that exact paragraph, but it was a library book in which I've returned. If I find a way to read it online or just check it out again, I will reblog this with the paragraph. This was the book

#funny thing#B.F. Skinner got accused of putting his own kid into some sort of freakish human skinner box#(it was just a heater he made for the kid's crib if im remembering correctly)#twitter#b. f. skinner#school#behaviorism#skinner box#psychology#books

144K notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Here it finally is. After effectively being over 6 months in the making, it didn't come exactly as I wanted it but leaving it in the oven is not an option. Sometimes you just have to accept imperfections. It's all part of the road of improvement.

Solving the WRPG VS JRPG discussion required a very specific set of skills and information which took me years to collect, combine and analyze which explains why it took so long for anyone to figure out. I was hoping someone else could have come with it first but if everyone kept waiting for anyone else to do anything nothing would happen, so I guess I had to be the one to do it.

I hope you enjoy this video, despite the dark tone, I tried to make it as entertaining and accurate as possible while still getting my points across.

#game design#youtube#skinner box#funny#the super awesome aarpong#video games#anime#this is sooo me 🥰#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Product design and psychology: Psycho manipulation techniques in gaming

Keywords: Product Design, Gaming, Psychological Manipulation Techniques, Player Behaviour, Player Engagement, Skinner Box Mechanics, Fear of Missing Out, (FOMO) Social Pressure, Sunk Cost Fallacy, Artificial Scarcity, Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment (DDA), Pay to Win, Teasing Future Content, Locus of Control, Grinding, Loot Boxes, Gacha Systems, Zeigarnik Effect, Genshin Impact, Ethics in Game Design, Addiction in Gaming, Excessive Spending, Unfair Gaming Environment, Ethical Game Design Practices, Responsibility of Designers and Developers

Abstract:

This paper explores the implementation of psychological manipulation techniques in product design, particularly in gaming, focusing on their effects on player behaviour and engagement. The discussed techniques include Skinner Box Mechanics, Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), Social Pressure, Sunk Cost Fallacy, Artificial Scarcity, Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment (DDA), Pay to Win, Teasing Future Content, Locus of Control, Grinding, Loot Boxes, Gacha Systems, and the Zeigarnik Effect. Real-world examples, such as the game "Genshin Impact", are used to illustrate the techniques' applications. While acknowledging these methods' effectiveness in increasing player engagement and revenue, the paper raises concerns about their potential to foster addiction, promote excessive spending, and create unfair gaming environments. The study calls for ethical game design practices and highlights the designers and developers' responsibility in maintaining a balanced and fair gaming experience.

Introduction

Psychological manipulation techniques have been employed in various aspects of human life, from interpersonal relationships to marketing and advertising. Understanding these techniques can shed light on how consumer behaviour is shaped, how decisions are influenced, and how interactions are guided. In product design, these methods play a critical role, often subtly, in guiding user experience, driving engagement, and encouraging specific user actions. The gaming industry, in particular, has become adept at employing these techniques to create compelling and immersive experiences.

However, the application of psychological manipulation techniques in product design is not without controversy. Moral and ethical concerns often arise, particularly when these tactics are used in ways that can lead to addictive behaviours or unnecessary expenditure. The impact of these techniques on the mental health and wellbeing of users is a subject of ongoing discussion in both academia and the industry.

To comprehend the dynamics of these manipulation techniques, this paper delves into eleven of them, as applied in game design, with a focus on their influence on player behaviour and engagement. Importantly, each technique will be viewed from both a product design and psychological standpoint to ensure a comprehensive understanding of its implementation and implications.

The Techniques

1. Skinner Box Mechanics

In the world of behavioural psychology, the Skinner Box, developed by B.F. Skinner, plays a pivotal role. This mechanism revolves around the concept of operant conditioning, where subjects learn to associate behaviours, such as pressing a lever, with receiving rewards. Game designers have translated this concept into their work by prompting players to perform simple tasks, followed by randomized rewards, thereby creating a compulsive loop of behaviour.

This is evident in various mobile and free-to-play games, where completion of tasks results in rewards such as virtual currency, points, or character enhancements. However, the randomness of the reward sequence can lead to a compulsive cycle where players continue to perform tasks in anticipation of a potentially more substantial reward next time - an aspect that can become addictive.

2. Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

The phenomenon of FOMO plays a critical role in player engagement strategies in games. Time-limited events or offers with exclusive content available only for a short duration can induce a sense of urgency and scarcity. This pressure can propel players to participate or make purchases for fear of missing out on the exclusive content.

For instance, games often introduce special holiday events or weekend sales offering exclusive items or characters. By time-limiting these events, they can stimulate a sense of scarcity and urgency, urging players to spend more time in the game or make additional purchases.

3. Social Pressure

Social dynamics are influential factors in the gaming experience, particularly within multiplayer environments. Social pressure can push players to spend on cosmetic items to maintain status within a group or use social connections to encourage continuous engagement with the game. For example, games often offer bonuses for inviting friends to join or rewarding cooperative play to capitalize on the innate human desire for social connection.

However, the potential downside of this manipulation technique lies in the pressure it may create among players to conform to group norms or expectations, potentially leading to unnecessary spending or extended playtime.

4. Sunk Cost Fallacy

The sunk cost fallacy has a profound impact on player behaviour. As players invest more time, effort, and money into a game, they are more likely to continue playing to justify their initial investment. This can be the case even if the player's enjoyment of the game decreases over time.

This phenomenon can be problematic, particularly when it encourages players to spend more money or time on a game they no longer find fulfilling, leading to potential addiction or excessive spending.

5. Artificial Scarcity

Game designers often use artificial scarcity to increase the perceived value of in-game items or characters. By limiting the availability of certain items, an illusion of scarcity is created, leading players to spend more resources to acquire them. This can have a significant impact on player behaviour, driving players to play longer hours or make additional purchases to secure these scarce resources.

While this strategy can enhance player engagement and revenue, it also raises ethical concerns about encouraging excessive spending.

6. Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment (DDA)

Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment is a technique that tailors the game's difficulty level based on the player's skill. Transparent application of DDA can enhance player engagement by providing a suitable level of challenge. However, when used non-transparently, it can be seen as manipulative, as it can be used to encourage additional spending.

For instance, making a game temporarily more challenging might push players towards purchasing power-ups or additional resources. This manipulation can create an unbalanced gaming experience, leading to questions about its fairness and ethics.

7. Pay to Win

The 'Pay to Win' model is prevalent in many games, allowing players to purchase items or upgrades that provide a significant advantage in gameplay. While this can help generate revenue for the game, it creates an uneven playing field favouring those who spend more money.

This model raises serious ethical concerns about creating an unfair gaming environment and promoting excessive spending.

8. Teasing Future Content

Teasing future content can be an effective strategy for keeping players engaged and looking forward to new additions. By giving sneak peeks of upcoming features or content, games can retain player interest, even if they may be losing interest in the current content.

However, it's important to consider the potential disappointment and loss of trust that could occur if teased content does not live up to player expectations.

9. Locus of Control

A player's sense of control over the game's environment, narrative, or outcomes can significantly enhance their engagement and immersion. By fostering a sense of agency, game designers can captivate players, keeping them invested in the game world.

However, providing an illusion of control, where the actual impact of player decisions is minimal, can lead to player frustration and dissatisfaction.

10. Grinding

Grinding, or repeating tasks for incremental gain, is common in many games, particularly in Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs). The player's progress is often determined by their character's level, skills, and equipment, which are typically improved through grinding.

While grinding can provide a sense of progress and achievement, it can also lead to fatigue or boredom if not carefully balanced with other gameplay elements.

11. Loot Boxes

Loot boxes, containing a random assortment of in-game items, have become a popular mechanism in game design. They can provide excitement and unpredictability, enhancing the gameplay experience.

However, loot boxes have come under criticism due to their similarity to gambling, raising concerns about fostering addictive behaviours and encouraging excessive spending.

12. Mechanisms of Gacha

The Gacha system, named after Japanese toy vending machines, has become a pervasive strategy within the gaming industry. It operates on a 'loot box' principle, where players pay for the chance to obtain a randomized item of varying rarity. This mechanic is psychologically intriguing, as it taps into the human predilection for chance-based rewards, thereby playing a crucial role in player retention and revenue generation. The intermittent and unpredictable nature of rewards in Gacha systems makes them akin to Skinner's variable-ratio schedule, which is known to produce high rates of response, even in the absence of rewards.

This forms the psychological bedrock of Gacha systems' addictiveness. The thrill of obtaining a rare, powerful character is essentially gambling, which is inherently addictive. Similarly, in "Genshin Impact," players can acquire weapons or characters using Primo gems (the game's currency), resulting in variable outcomes.

13. Zeigarnik Effect

The Zeigarnik effect, originally studied by Russian psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik in the 1920s, postulates that people tend to remember unfinished tasks better than they recall completed ones. The present study explores the Zeigarnik effect from two key perspectives: psychological and product design. Through the detailed analysis of real-world examples and case studies, this paper aims to provide insights into how product designers can harness the Zeigarnik effect to create more compelling, engaging, and user-friendly products.

In the realm of product design, the Zeigarnik effect can be employed to increase user engagement and retention. One of the primary ways is by creating a sense of incompletion that motivates users to return to a product or service.

The gaming industry is a prime example where the Zeigarnik effect is utilized. Games like Candy Crush keep players engaged by offering multiple levels that create a sense of unfinished business. The constant reminder of the pending level increases the likelihood of the user returning to complete the game.

14. Genshin Impact

In the pantheon of modern digital entertainment, 'Genshin Impact' has established itself as a monumental exemplar of the gamic medium's potential. Developed by the Chinese company miHoYo, the game has found global resonance since its release in 2020. The focus of this article is to scientifically dissect the integral components of 'Genshin Impact', emphasizing its gameplay, narrative, technological elements, and its influence on socio-economic aspects.

From a ludo logical perspective, 'Genshin Impact' showcases an amalgamation of game mechanics and systems, providing an extensive interaction spectrum for its players. As an action role-playing game (RPG), it encapsulates various interaction modalities including combat, exploration, puzzle-solving, and character development. The game's combat system relies on a character-switching mechanism that promotes strategic combination of different character abilities, while its progression system encourages continual exploration of the game's vast world.

The incorporation of 'gacha' mechanics, where players can obtain random virtual items or characters, illustrates the application of probability theory and the role of randomness in player motivation. It taps into the psychological principle of intermittent reinforcement, incentivizing continuous engagement through the thrill of uncertain rewards.

Conclusion

While the psychological manipulation techniques employed in game design can effectively enhance player engagement and generate revenue, they also pose potential risks. Fostering addictive behaviours, encouraging excessive spending, and creating unfair environments are significant concerns.

Understanding these techniques, their implementation, and their implications can inform ethical game design practices. It can also stimulate critical conversations about the role of psychological manipulation in product design and the responsibilities that designers and developers bear in ensuring a balanced and fair gaming experience. It's essential that the gaming industry continually assesses these techniques' ethical implications to provide enjoyable, immersive, and ethical gaming experiences.

References:

Fogg, B. J. (2009). A behavior model for persuasive design. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology - Persuasive '09. doi:10.1145/1541948.1541999.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The Behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841-1848.

Cialdini, R. B. (2006). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Arkes, H. R., & Blumer, C. (1985). The Psychology of Sunk Cost. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 35(1), 124-140.

Zagal, J. P., & Deterding, S. (2018). Modes of Play: A Frame Analytic Account of Video Game Play. Games and Culture, 13(8), 854–877.

Hunicke, R., LeBlanc, M., & Zubek, R. (2004). MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research. Proceedings of the AAAI Workshop on Challenges in Game AI.

Consalvo, M. (2009). Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Walz, S. P. (2010). Toward a Ludic Architecture: The Space of Play and Games. ETC Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The "What" and "Why" of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

King, D., Delfabbro, P., & Griffiths, M. (2011). The convergence of gambling and digital media: Implications for gambling in young people. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27(2), 193-213.

Hamari, J., Alha, K., Järvelä, S., Kivikangas, J. M., Koivisto, J., & Paavilainen, J. (2017). Why do players buy in-game content? An empirical study on concrete purchase motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 538-546.

Zeigarnik, B. (1927). Das Behalten erledigter und unerledigter Handlungen. Psychologische Forschung, 9, 1-85.

Hu, J., Gao, H., & Wang, Q. (2017). Examining digital cheating in video games from a moral perspective. Ethics and Information Technology, 19(4), 243–255.

Griffiths, M. D., & Nuyens, F. (2017). An overview of structural characteristics in problematic video game playing. Current Addiction Reports, 4(3), 272-283.

Paulus, F. W., Ohmann, S., von Gontard, A., & Popow, C. (2018). Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 60(7), 645-659.

Zhu, J., & Zhang, W. (2019). Arising of the ethical issues in the digital era of game industry. International Journal of Technology and Human Interaction, 15(1), 1-18.

#ux#ux desgin#psychological manipulation#game design#product design#video games#skinner box#FOMO#loot box#sunk cost fallacy#pay to win#social pressure#dynamic difficulty adjastment#grinding#locus of control#teasing future content#gacha mechanism#zeigarnik effect#genshin impact#artificial scarcity

1 note

·

View note

Text

guh .. learning how to draw beloved simpsons characters. which is to say, heh. partially by memory

+ my oc who you will definitely be seeing/hearing more about (no thanks to my lovely friends fjdjs) and simpsoned mayor majig find everythang ^^

#the simpsons#snake jailbird#rod flanders#todd flanders#timothy lovejoy#reverend lovejoy#ned flanders#gil gunderson#seymour skinner#principal skinner#superintendent chalmers#gary chalmers#cherub berg#mayor majig#me when i go hrm .. i probably shouldn’t tag everyone#but also i love organisation so igaf & cope#tsto#the simpsons tapped out#fe roblox#artberg#my ocs#simpsons oc#the ol’ pen and paper#don’t look at my black box#i cant let you see what’s underneath#springwheel housewives#< placeholder tag ig

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

s6 episode 1 thoughts

season 6!!!! my goodness, how the time sure has flown!! i started this whole project in may of last year, and now we are in january! so much has changed! but other things have stayed the same.

i have heard mixed things on s6, so i am a bit nervous. but i am excited to be reunited.

i am also curious to see where exactly the movie was set after the finale of s5. has it been a while, or only a few days? has our little friend gibson been missing this whole time? what about diana- did she pull through? will we get to know more about her?

we need to microchip gibson so we never lose him again.

(i felt vindicated when people told me diana isn’t a fandom favorite, LMAO. i’m usually the girl that goes to BAT for overhated female characters, but she just seemed too intentionally antagonistic towards scully)

so… this episode shall deal with our agents going on a hunt. well, they had best be careful! there are a bunch of different aliens and beasts on the loose!

(post-episode thoughts: my fury at mulder is 75% normal juni rage and 25% enhanced by me being sick and emotional, a fact i only put together the morning AFTER i took all of these notes. you have been warned....)

anyway. let us begin!

(previously, on the x files)

(and i STAND by my opinion that CSM has a very soothing voice, okay?!? googling this man so i can see if he narrates any audiobooks)

man, i forgot about mulder pushing spender up against the wall and their feud. ah, spender. i feel bad for him, but that doesn’t mean i LIKE him.

OH, WE GET TO SEE CLIPS FROM THE MOVIE IN THIS RECAP!! and they are in such high quality in comparison to the DVD i borrowed!! wow. when i watch it again sometime in the future- hopefully not on a DVD from 1998- i cannot wait to see everything so CRISP.

NOT THE KISS BAIT BEING INCLUDED IN THE RECAP LMAOOO

but now let us begin the adventures of s6!

NOOOOO! roush!!! the evil biological company! their truck is out in the desert. and their guys are pissing.

well. this happens.

sandy is sweating. bro does NOT look good. i know his ass is not making it through the night.

when sandy gets home, he cranks the heat up to 80 in arizona, which is WILD. then he goes to lay on the couch and shiver.

AUGH!!! his hand is JELLY???? it’s see-through!!! i did not want to look at all of sandy’s veins!!!

is he having an alien baby, too?!?!

his work buddies come to fetch him later. we see a bunch of photos of him in his house wearing a lab coat and doing doctor-y things.

AWW, his coworker called him sandman. don’t make me feel bad for the dude who works at the evil alien biotech company…

BLEURGH. he DID have an alien chest baby virus infection thing. OH, this other guy is SHOCKED!! AND HE HEARS THE ALIEN HISSING AT HIM!!!!!

HE’S GETTING EATEN!!!!! NOOOO!!!!

RIP this guy :(

YAAAY, the intro!!! felt weird not having it with the movie!!!

and it was shortened, but okay. i’m getting used to that.

ahhh, look at this computer on which mulder is examining something. is he looking at micro film?

OH, the sweet boy, he’s restoring the fragments from the x files!! this makes me sad!! does that mean there isn’t a huge box of floppy disks somewhere containing all of them? because it is the responsible thing to do, making sure you have all your files saved in multiple sources! well, we’re only a few minutes into the episode. there’s still time for one of those to be found

and now he is presenting before a panel. he says the x files were destroyed “several months ago”, which places us on a vague timeline. scully is here!!!!

“i see your renowned arrogance has been left quite intact”, says this dude on the panel, and HEY! mulder literally isn’t even being arrogant at THIS MOMENT, OKAY? plenty of other times he is. but not now, as he is submitting his report on this alien spaceship!!

“i didn’t see men in black” “well it’s a damn good movie” <- LMAO they are BULLYING HIM!!!

scully looks pained.

NOT THEM GETTING ON HIS ASS FOR THE TRAVEL EXPENSES STOOOOOP BEING MEAN!!!

OHHH NOOOOO!!! he says that scully can prove the whole thing, but she can’t. cut to them fighting in the hallway.

mulder… you’re pissing me off. SHE DOESN’T KNOW WHAT THE VIRUS IS OR HOW IT WOULD MAKE ALIENS!!!!!! maybe you should have brought a camera to the arctic. don’t you BRUSH INTO HER SHOULDER AS YOU WALK AWAY!!! you were going to KISS HER like a few weeks ago!!! i won’t tolerate this disrespect.

CSM is debriefing the syndicate on the arizona alien deaths, saying he made up a cover story and it’s called “blaming it on Native Americans”. classic CSM, world-renowned great guy /s

so, he thinks the arizona guy who gave birth to an alien chest baby accidentally injected himself with the virus, and now the alien is on the loose!!!

man, the presence of well-groomed man is missed. RIP. this other guy is here, though. so that’s good. i guess.

CSM says he is managing the situation. will he be sent out to test his sniping skills?? can you snipe an alien?

skinner is coming down to see mulder on the computer… NOOO, he breaks the news that his reassignment on the x files has been denied!!!!!

mulder's all angry, and skinner tries to clarify he’s not arguing with him, but raises the question: “when will you accept that no amount of pressure or reason will bring to heel a conspiracy whose members walk these halls with absolute impunity?” <- ohhh, a very good point…

so they reopened the x files, then denied his reassignment? are they going to assign them to someone else? or just close them again?? will they keep scully on them?

skinner said that the vote was unanimous… he must have been trying not to blow his cover as mulder’s biggest supporter… but i'm sure this still made mulder very sad

so he gets all his stuff up and starts to leave. BUT SKINNER WANTS TO HELP HIM FIND PROOF??? SO HE CAN PROVE THE OTHERS WRONG??

i told you!!!! that man is my uncle.

he says there’s a file on his desk in the old office……. and sure enough, there is.

is this season much darker in terms of screen brightness?

OH SHIT…. why is spender down here in mulder's old office? WITH DIANA??? “diana, back on your feet. i guess that’s the only way you can stab me in the back” <- damn. he's pissed.

woah, what? okay, i was imagining scully staying on the project and spender taking his place, which would obviously be awful, but diana taking his place is like, worse. so now is it going to be spender and diana? instead of mulder and scully? ew.

jump to CSM lighting up in front of a no smoking sign… he’s just fundamentally a bad boy. he’s walking in where some sort of surgery is taking place!!!

he says he needs the patient bandaged and dressed, even though this might kill them. OH SHIT! IT’S GIBSON!!! and he must be in the middle of surgery!!!!!

EAIGHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH THEY HAVE HIS BRAIN OPEN………….

good lord, i nearly passed out. again, i repeat my grounding mantra: shoutout to the props team.

and he was awake, too………..

poor baby.

AWWWW, THE AGENTS ARE DOWN IN PHOENIX to investigate the case that skinner left them the files on, and scully WILL remind him that they are violating state laws regarding contamination of a crime scene (she lets out a deep scully sigh, asking “why do i bother?”) yeah. idk either queen.

he sees claw marks on the walls!!! that does not look like it came from some bare hands. scully is not fooled by this claim in the evidence report.

ooooooo, he finds a claw!!!!!!!!

“is that an animal?” “ain’t rupaul” <- LMAO I’M CRYING?????????

mulder, i knew you were an ally ✊

(listen, both of those agents are bisexual to me. and maybe ace, too. depends on the day. THAT'S MY OPINION!)

(he hands the claw to scully very carefully <3)

feels wrong to see him in what i think is a polo, but it is hard to tell because the screen is so DARK.

oh yeah, let scully calculate the gestation rate of this hypothetical alien baby. under 12 hours!!! damn!! that is… quick. and also? how could a baby do all this, she wants to know? well. some babies are more equipped for violence than others. i guess.

oh no! CSM IS HERE!! AND POOR BABY GIBSON, BLEEDING THROUGH HIS BANDAGES!!

please someone lay him down and let him watch spongebob. NOW.

gibson announces that "it" (alien baby) isn’t here. and that he knows CSM wants to kill him if he can’t find the creature. poor sweet little dude. they drive off.

mulder emerges into the daylight, and he does, in fact, have a polo on. but he is asking scully why she won’t believe him. MAYBE IT *WILL* TAKE AN ALIEN BITING HER FOR HER TO BELIEVE, BUDDY!!! DON'T RAISE YOUR GODDAMN VOICE AT HER!!