#rose d’or

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#OUR dads won an award#Sophie so real as always#sophie duker#rose d’or#taskmaster#alex horne#greg davies#taskmaster uk

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

J’ai encadré ma rose dorée à la feuille pour l’expo à Poligny

#tilleul#woodcarving#bas relief#handmade#sculpture sur bois#wood carving#sculpture#dorure#feuille d’or#rose#cadre

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'Art et la mode, no. 1, vol. 32, 7 janvier 1911, Paris. Robe de mousseline de soie “pétale de rose” ornée de broderie d’or patiné sur tulle et entredeux de Bruges en transparence. Imp. d'art L. Lafontaine, Paris. Bibliothèque nationale de France

#L'Art et la mode#20th century#1910s#191#on this day#January 7#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#color#bibliothèque nationale de france#dress#gown#evening#january color plates

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

TWST Fanfics guide - nicknames

Rook’s Nicknames

Himself - Le chasseur d’amour

Yuu - Trickster

Grim - Monsieur Fuzzball

Riddle - Roi des Roses

Ace - Monsieur Heart

Deuce - Monsieur Spade

Cater - Monsieur Magicam

Trey - Chevalier des Roses

Leona - Roi des Lions

Jack - Monsieur Tough Guy

Ruggie - Monsieur Dandelion

Azul - Roi d’Effort

Jade - Monsieur Mastermind

Floyd - Monsieur Kills for Thrills

Kalim - Roi d’Or

Jamil - Monsieur Multi-Skilled

Vil - Roi du Poison / Beautiful Vil

Epel - Monsieur Cherry Apple/Crabapple

Idia - Roi de Ta Chambre

Ortho - Monsieur Doll

Malleus - Roi des Dragons

Silver - Monsieur Sleepyhead

Sebek - Monsieur Crocodile

Lilia - Monsieur Curiosity

Neige - Roi de Neige

Floyd’s Nicknames

Yuu - Little Shrimpy (Koebi-chan)

Grim - Baby Seal (Azarashi-chan)

Riddle - Little Goldfish (Kingyo-chan)

Ace - Crabby (Kani-chan)

Deuce - Little Mackerel (Saba-chan)

Trey - Sea Turtle (Umigame-kun)

Cater - Sea Bream (Hanadai-kun)

Leona - Sea Lion (Todo-senpai)

Jack - Sea Urchin (Uni-chan)

Ruggie - Sharksucker (Kobanzame-chan)

Kalim - Sea Otter (Rakko-chan)

Jamil - Sea Snake (Umihebi-kun)

Vil - Betta Fish (Beta-chan-senpai)

Epel - Guppy (Guppy-chan)

Rook - Seagull (Umineko-kun)

Idia - Firefly Squid (Hotaru Ika-senpai)

Ortho - Sea Angel (Clione-chan)

Malleus - Sea Slug (Umiushi-senpai)

Silver - Jellyfish (Kurage-chan)

Sebek - Crocodile (Wani-chan)

Lilia - Flapjack Octopus (Mendako-chan)

Crewel - Beakfish (Ishidai-sensei)

Trein - Red Squid (Akaika-sensei)

Vargas - Lobster (Lobster-sensei)

Sam - Seahorse (Umiuma-kun)

Vil’s Nicknames

Pomefiore 1st years - Fresh potatoes

Epel - Baby potato

Ace - Fresh potato 1

Deuce - Fresh potato 2

Sebek - Cucumber

Leona’s Nicknames

Yuu - Herbivore

Riddle - Red Young Master

Azul - Octopunk

Idia - Radish sprout

Malleus - Young Master, Lizard, Monster

#disney twisted wonderland#twst#twst wonderland#disney twst#twisted wonderland#twst nicknames#twisted wonderland disney

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gary Oldman wins performance gong at Rose d’Or Awards for role in Slow Horses | The Standard

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

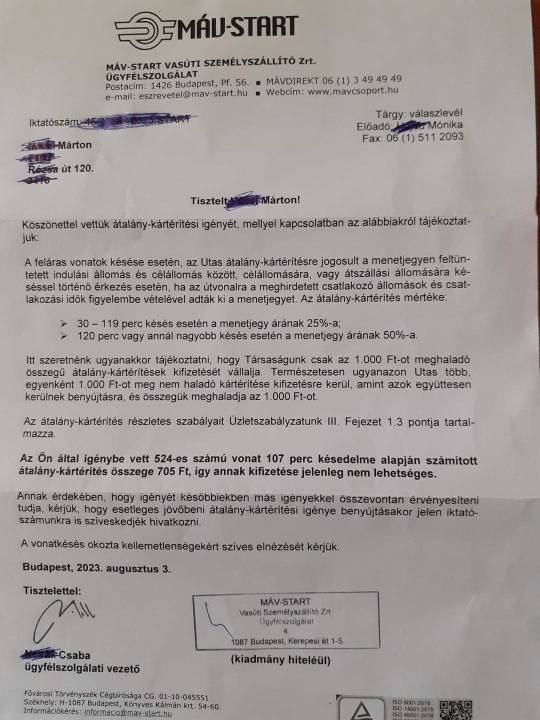

Kedves Csaba!

Amint arról a visszatérítési igénybejelentő lapomból értesülni tetszett, az általam július 28-án igénybe vett 524-es számú vonattal a menetrend szerinti 1 óra 25 perc helyett 3 óra 50 perc alatt jutottam le Budapestről Mezőkövesd állomásra. További félórát töltöttem el az igénybejelentő lappal való baszakodással a máskülönben igen készséges pénztárosnő, H. Mónika társaságában. A vonatom 50 percet a pusztában állt, és ahelyett, hogy előre ment volna, hátrafelé indult tovább. Nem messze Szihalomtól, ahol tüzesen süt le a nyári nap sugára, az Önök édesanyja járt a fejemben. Emiatt szíves elnézését kérem.

Itt szeretném ugyanakkor tájékoztatni arról, hogy a Rose d’Or nevű luxushajó tankjába 130.000 liter gázolaj fér, ami mai áron 81.640.000 forintba kerül. Az én menetjegyem ára 2820 forint volt. Nem kell ahhoz az átalány-kártérítési szabályok nagy ismerőjének lenni, hogy kiszámoljuk, 28.950 db (azaz huszonnyolcezer-kilenszázötven) teljes árú Budapest-Mezőkövesd menetjegy árát tudnák ebből az összegből visszafizetni a károsultaknak.

705 (azaz hétszázöt) ki nem fizethető forint kártérítés jár ma Magyarországon egy 107 perces késésért.

Nem leszek szíves elnézni, hogy lopják az időmet, a pénzemet.

Azt kívánom Önöknek, hogy üljenek az idők végezetéig egy Füzesabony és Szihalom között veszteglő Inter City másodosztályú kocsijában egy nyugdíjas asszonnyal, aki Kassára igyekszik, hogy végre láthassa Rákóczi sírját. Ott rohadjanak meg abban a kocsiban az üzletszabályzatukkal együtt.

Márton

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

« Depuis toujours les marronniers sont présents dans l’œuvre de Proust [...]. “Que d’heures j’ai passées dans ces grottes mystérieuses et verdâtres à regarder au-dessus de ma tête les murmurantes cascades d’or pâle qui y versaient la fraîcheur et l’obscurité !” Ce sont les arbres de la continuité. Même sous la pluie dissolvante, ils rassurent le narrateur : “Assis dans le petit salon, où j’attendais l’heure du dîner en lisant, j’entendais l’eau dégoutter de nos marronniers, mais je savais que l’averse ne faisait que vernir leurs feuilles et qu’ils promettaient de demeurer là, comme des gages de l’été, toute la nuit pluvieuse, à assurer la continuité du beau temps…”

Arbre entre les arbres, trait d’union entre l’ici-bas et l’en-haut, le passé et l’avenir, somptueux, érotique et protecteur, le marronnier érige vers le ciel des fleurs roses et superposées “immobiles comme la tête royale d’un oiseau”. Il brûle de lumières changeantes. Il tremble de pluies. Il laisse “traîner au soleil son vaste plumage lisse et incliné de larges feuilles vertes”. [...] Il participe par son odeur aux sens ; par son feuillage à la cachette ; par la richesse de ses fleurs à une profusion rassurante. Voici enfin une fleur si multiple qu’elle défie le sentiment de la perte [...].

Seule cette profusion, qui masque l’absence, annule ce “jamais assez” qui, chez Proust, bouleverse toute possibilité d’apaisement. “Pour celui qui veut tout, et à qui tout, s’il l’obtenait, ne suffirait pas, recevoir un peu ne semble qu’une cruauté absurde.” »

— Diane de Margerie, Proust et l’obscur

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myth of Medea (2)

Next article, following a chronological order, is “Medea, from the 16th to the 18th centuries”, written by Patrick Werly.

During the Middle-Ages, Medea is depicted in several tales. Benoît de Sainte-Maure’s Roman de Troie, in the middle of the 12th century; Guillaume de Loris and Jean de Meng’s Roman de la Rose, in the 13th century; the anonymous Moralized Ovid of the 14th century ; the Jugement du Roy de Navarre by Guillaume de Machaut in the 14th century, etc…

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, Medea was mostly encountered on theater stages and within operas, in works that are more inspired by the tragedies of Seneca and Euripides, rather than by the Metamorphoses of Ovid. However, there was an effort of appropriation to be made: indeed, the myth of Medea the Scythian, of Medea the Barbarian, part of the classical works of Antiquity, was at risk of ruining the moral values and the aesthetic system that Europe had imposed upon itself. As such, a “displacement” of the figure was required. Three main authors have to be considered: Calderon de la Barca, Pierre Corneille, and Thomas Corneille as the librettist of Marc Antoine Charpentier.

I/ The allegorical reading

The authors of the 17th century mostly found their sources in a mythology manual that had been published in 1552 by Noël Conti (or Noël le Comte, in Latin Natalis Comes, 1520-1582), and which was titled: “Mythology, or the explanation of fables, containing the genealogies of the gods, the ceremonies of their sacrifices, their deeds, their adventures, their loves, and almost all of the principles of the natural and moral philosophy”. Corneille used it to write his Conquête de la Toison d’Or, Caderon also probably used it for his El divino Jason. The seventh chapter of the sixth book is dedicated to Medea: after retelling the myth, Noël Conti presents the “physical mythology”, then the “moral mythology”. In both cases, the process it to try to use the myth for the moral edification of the reader, through mean of the allegory. As such, the reason behind the “dissection and death of Medea’s brothers and children” is because she wanted to put behind her appetite and concupiscence: “if someone let themselves we trapped by the slimy nets of unreasonable pleasures of the flesh, of greed, of cruelty; then it is to no surprise that good advice and counsel climbs on its chariot and flies away in the sky with winged dragon”. According to the etymology offered by Noël Conti, and that Calderon will reuse, Medea is “the advice”, “the counsel”, that is to say, the scholastic tradition, the wise decision, the choice made after a deliberation. The mythographer is aware of the negative image of Medea: but it does not matter if she is good or evil for, in the tradition of the Moralized Ovid, Medea needs to have a usefulness for the moral and religious domains. “Whether we take Medea to be advice and prudence, or to be a very wicked and malevolent woman, the Ancients, through this Fable, intended to shape us and lead us to probity, and to the integrity of the mores”. This is the moral lesson we must keep: the violence of the myth is transposed for the benefit of virtue.

This allegory can be found in the self-sacramental El divino Jason, composed in 1634 by Calderon de la Barca (1600-1681). In this play, the allegory is explicitly Christian since Jason is the Christ, Hercules saint Peter, Orpheus saint John the Baptist, etc… The fleece represents the soul, the one of a lost sheep which fled from the herd of the Christ and that Jason is thus looking for. But the quest of Jason is a dual one, because the soul is also depicted by Medea, which is also the allegory for Gentilism. Jason says of her: “Medea, who means / Advisor and Knowledgeable in all / was once the Gentilism / which offered itself to the superstitious rites / of magic / and to its idols which are but air / smoke, dust and nothingness”. The task of Jason is to bring Medea with him on the Argo ship to take her away from the land of Colchis, but also to free her from the influence of Idolatry, an actual character of the play, which embodies the religion and the pagan wisdom of the Antiquity.

When Medea encounters Jason for the first time, on the shores of Colchis, she decides to simulate her love (“Amor le pienso fingir”), but Jason tells her he only came here to love her (“Vengo a amarte”), and then Medea is caught by her own trap, and falls in love truly (“Pensaba fingir amores / y va verdaderos son”). When she offers herself to Jason, she also offers at the same time the Fleece that he came here to seek (“Digo que de amores muero ; / tuyo sera el vellocino / que buscas, Jason divino”).

Follows a strange scene in which Theseus (here, saint Andre) pronounces a long, poetic speech filled with proper names (those of the Argonauts, of Medea, of Idolatry), with names of flowers, of colors, of virtues. Each, when they hear their name, or the name of their flower, color, virtue, answers Theseus. Medea chose the clover (a leaf without a flower, which makes a beautiful border for others’ bouquets), the color green, and the virtue of Hope. In this long passage, a baroque chorus presents the union of Medea to Jason as her union to Christianity, as well as her rejection of Idolatry (“No quiero / seguirte mas, fero monstruo / Oh, como y ate aborezeo!”)

Jason, to redeem the mistakes of Medea, will undergo the trial of taking the Golden Fleece away from its tree (which is also the Tree of Adam). At the top, he replaces the Fleece with a Lamb which bleeds, and whose light blinds and strikes down Idolatry, while Hell opens up below her. Calderon did not stage in any way the magical powers of Medea: here, she is only a sorceress by reputation. Magic is only due to the characters of the Idolatry, and of the King (which represents the World), but it is powerless against the Argonauts led by Jason. What replaces magic in terms of supernatural effects, is the miracle, the one that Jason accomplishes. In the dramaturgy of the play, the actions that go beyond the power of man are not those of magic, but those of religion, the one to which Medea converts herself. In this allegory, the barbarian, the wizardess, abandons all of her attributes to follow the pastor-Jason. The sheep found back its flock, the soul now belongs to the Church.

II/Medea as a victim

Médée is the first tragedy of Pierre Corneille, which was played during the season of 1634-1635. The play is already a work part of the classical canon (the author tries to respect the unicity of location, time and action), but it does not respect the rule of “bienséance”, since we see dying on stage the king and the princess. Corneille, in his letter-preface to his play, explains that poetry often makes “beautiful imitations of actions we should not imitate”, and he plays on the two meanings of the verb “imitate”. But it is also a trick of Corneille to keep the moral safe. Indeed, the actions of Medea can be explained by the fact that she is victim of a political conspiracy; it is an explanation that allows to rationalize her actions, and thus judge them by the light of “common reason”. Jason, the man that she loves, presents himself as such: “Thus I am not one of those vulgar lovers / I adjust my flame to the good of my businesses / And under whichever climate fate would throw me / I will be in love by State maxim” (I,1). And Creon, the king, talks about Egeus, who originally had to marry Creusa before she was promised to Jason: “Whichever reasons of State might satisfy him” (II,3). Marriage is thus placed under the sign of the “reason of the State”, of which Medea is the victim. She pleads her cause by herself in these words: “Anyone who condemns a criminal without hearing them / Even if they deserved a thousand times their punishment / Turns a just sentence into an injustice” (II,2).

Corneille thus introduced a judiciary dimension to his play: Medea was condemned to exile for the murder of Pelias, but she was not properly put on trial. She becomes the victim of Creon’s tyranny. But beyond her, it is all of her family, an entire dynastic branch that is victim of a tyrannical power. Indeed, Medea is the grand-daughter of the Sun, and if Jason marries Creusa, their children will dishonor the dynasty: “You will mingle, impious one, and put on the same rank / The nephews of Sisyphus and those of the Sun! / […] / I will gladly prevent this odious mixing, / Which dishonors together my family and my gods” (III,3). As such, the series of crimes is explained: Creusa’s death prevents the misalliance, while the death of the children both suppresses radically the cause of the dynastic troubles while also hurting Jason. Medea answers to the conspiracy created “by reason of State” by what was called in the 17th century a “coup d’Etat”, a premeditated act conceived in secret and that goes beyond common law. This coup d’Etat is here placed on the mythological terrain of magic, as Louis Marin analyzed. Pierre Corneille seems to be so far the only author to have turned the murder of Medea into a political act – the 20th century also made the myth politic, but in a different context.

Corneille wrote another play which features Medea: La Conquête de la Toison d’or (1660). Medea the sorceress is here also a garden architect: the setting of the first act is a French-style garden, seen in perspective, and the character of Absyrte reveals that it was conceived by Medea’s art, the only one able to create such a beauty in a savage and hostile nature. Magic is here linked to the laws of geometry ; but it can be vanquished by the laws of love, such as in the twelfth Héroïde of Ovid, or to be more precise by the superior power of love. Medea says to Jason that she cannot help but love him despite his treachery: “Are you in my art a greater master than me?” (II,2). This art, she later says to her brother Absyrte, “if it has on all else an absolute power / Far from charming hearts, it doesn’t see anything in them” (IV, 1). Thus, the tragedy exposes the limits of the power of Medea: we are far away from the supreme power of the 1635 tragedy.

III / Medea in the opera: the embodiment of division

In their 1693 lyrical tragedy Médée, Marc-Antoine Charpentier and Thomas Corneille use, just like Pierre Corneille did before them, Seneca as their main source, but their opera is not concerned with the political dimension of the tragedy. What is rather important here is to gather around the character of the sorceress the most spectacular elements. We see Medea, helped by demons, by Vengeance, and by Jealousy, preparing in a cauldron the poison that will kill her rival (III,7). We see the guards of the king trying to seize Medea, but turning their weapons against each other before seizing Creon, and finally leaving to pursue “ghosts with the shape of pleasant women” (IV, 7). At the end of the fourth act, the earth opens below Creon, and he sees Medea in the waters of the Styx, while the orchestra is divided into two very distinctive groups of instruments. A same motif recurs in those scenes, like a choreography: the idea of division and separation. The guards are divided by fighting against each other, then they turn against the king they receive order froms, then the earth splits open… Medea is the one who separates, she is the creator of strife and discord. In III, 4, she says about herself and Jason “And may the crime separate us / As the crime joined us”. In the final scene, after killing her children, she claims to Jason: “Unfaithful! After your betrayal / Should I have seen my sons in the sons of Jason?”, a sentence in which the “us” disappears for the “you”, and where Medea dissociates herself from her children.

But Medea herself is divided. As the king kills himself, she is herself fractured. In the scenes IV, 5 and V, 1, she deliberates about the murder of her children, and this deliberation (in a typical 17th century fashion) is divided, as much on a semantic level as on a musical one. When the oscillation of the wizardess’ mind makes her regret her decision, we hear a slow, deep, internal music of cord instruments ; but when she is resolved to commit her crime, the tempo becomes faster and the clavecin dominates. The two rhythm finally converge when she takes her decision, because her doubts are only there for a theatrical effct. Medea is still Medea (“When you boast of being king / Remember that I am Medea”, IV, 6), as she was with Seneca (Nunc sum Medea) and as she was with Corneille (“Madam, I am queen / - And I am Medea, Conquête, III, 4).

In the genre of the opera, other pieces of note include Il Giasone (1649) of Pier Francesco Cavalli, and Medea (1797) by Luigi Cherubini, on a French booklet by François Benoît Hoffmann, where Medea switches between supplications and threats, in a role that was made famous in the 20th century by Maria Callas.

IV/ Medea in paintings and drawings

Jean-François de Troy (1679-1752) painted, for an Histoire de Jason in seven pieces by the Gobelin manufacture, a Médée enlevée sur son char après avoir tué ses enfants (1746). This is an episode taken from the seventh book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and Ovid will indeed be the main source of painters, rather than Euripides or Seneca. Medea, on her chariot pulled by two winged dragons, has a cold, hateful stare. In one hand she holds her magic wand, with the other she points towards the body of her two dead children. Jason is trying to pull out his sword while a soldier restrains him. In the background, Corinth and Creon’s palace are burning. Two small Cupids are behind the chariot. One is breaking his bow with his knee, the other is ripping off his blindfold. This detail explains the meaning of the scene, its allegory: the two little gods of love refuse their own power, upon seeing the devastation of love when it turns into a jealousy-fueled hatred. Or maybe should we understand the message as: if such a disaster is to be avoided, love must stop to be blind. All in all, the depiction of the myth of Medea must have a moral purpose: love must be much more aware and conscious, and it should be treated with logic and reason.

To find back the tragedy and the violence of the antique myth, we must look at two drawings of Poussin from around 1645, the second being a cleaner variation of the first. The scene depicts Medea killing her second child: she holds the child naked, by the leg, his head upside-down, and she raises her arm to hit his heart with a dagger. The first child is dead on the floor, and a terrorized woman, crumpled near his body, turns herself towards Medea to stop her. A bit above, separated by a balcony, unable to stop her, Jason points his arms towards Medea while Creusa lifts her hands towards the heavens. On the second drawing, a statue of Minerva also lifts her arms to the sky, using her shield as a protection not to see what is about to happen. All the violence of the scene can be read in the way the hands are organized in this drawing – and this violence, rarely depicted in such a direct way during the 17th century, is the one of Seneca’s tragedy.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunset Dream at the Blue Lagoon

Au Blue Lagoon, sous les couleurs du crépuscule, les eaux turquoise vibrent d’un éclat paisible. Le ciel se pare de teintes d’or et de rose, dans une danse douce où la lumière explose.

Sol de lave mêlé à la brume légère, dans un rêve où le calme est une lumière. La vapeur s’élève comme un voile éthéré, dessine une scène d’une beauté sacrée.

English translation :

In the Blue Lagoon, beneath twilight hues, the turquoise waters glow with a tranquil sheen. The sky dons shades of gold and rose, in a gentle dance where light bursts and flows.

Lava ground mingled with light mist, in a dream where calm is a luminous twist. The steam rises like an ethereal veil, painting a scene of sacred beauty unveiled.

#Cassiopeapoetry

#illustration#nature illustration#digital art#artists on tumblr#poésie#VisualPoetry#french poetry#mywriting#inspiration#nature#BlueLagoon#GeothermalPools#sunset#landscape#TurquoiseWaters

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le soleil brûlant

Les fleurs qu’en allant

Tu cueilles,

Viens fuir son ardeur

Sous la profondeur

Des feuilles.

Cherchons les sentiers

A demi frayés

Où flotte,

Comme dans la mer,

Un demi-jour vert

De grotte.

Des halliers touffus

Un soupir confus

S’éléve

Si doux qu’on dirait

Que c’est la forêt

Qui rêve…

Chante doucement ;

Dans mon coeur d’amant

J’adore

Entendre ta voix

Au calme du bois

Sonore.

L’oiseau, d’un élan,

Courbe, en s’envolant,

La branche

Sous l’ombrage obscur

La source au flot pur

S’épanche.

Viens t’asseoir au bord

Où les boutons d’or

Foisonnent…

Le vent sur les eaux

Heurte les roseaux

Qui sonnent.

Et demeure ainsi

Toute au doux souci

De plaire,

Une rose aux dents,

Et ton pied nu dans

L’eau claire.

Albert Samain, Au jardin de l’infante

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'Art et la mode, no. 52, vol. 21, 29 décembre 1900, Paris. Roses de Noël. Dessin de J. Portalez. Bibliothèque nationale de France

Manteau de panne mauve, drapé par une boucle "art nouveau" entourée de petits velours violets. Le bas et les parements sont dessinés d’iris en taffetas chiffonné, tons naturels.

Purple panne coat, draped by an "art nouveau" buckle surrounded by small purple velvets. The bottom and the facings are with an iris design in crumpled taffeta, natural tones.

—

Manteau en hermine et zibeline. L’hermine cesse sous une guirlande de roses incrustée en taffetas et panne peints. Volants de mousseline de soie blanche semée de roses et pétales incrustés en taffetas et panne, avec çà et là, du strass en gouttes de rosée. Col, revers et bandes de zibeline à l intérieur du vêtement.

Coat in ermine and sable. The ermine ends under a garland of roses inlaid in painted taffeta and panne. Ruffles of white silk muslin sown with roses and petals inlaid in taffeta and panne, with here and there, rhinestones in dewdrops. Collar, lapels and bands of sable inside the garment.

—

Manteau tout en zibeline et velours noir, avec agrafe "art nouveau" or et rubis Les nœuds qui courent sur le volant sont aussi fixés par des motifs "art nouveau".

Coat entirely in sable and black velvet, with gold and ruby "art nouveau" clasp. The bows running along the flounce are also attached by "art nouveau" motifs.

—

Mante en chinchilla, doublée de volants de mousseline de soie rose et lilas superposée en transparent. Capuchon de dentelle et fouillis de' dentelle resserré par un tour de cou de roses sans feuillage. Pans en dentelle enguirlandés de roses et attachés de nœuds de velours noir.

Chinchilla mantle, lined with pink and lilac silk chiffon ruffles in a transparent overlay. Lace hood and lace tangle tightened by a neckband of roses without foliage. Lace panels garlanded with roses and tied with black velvet bows.

—

Manteau de velours améthyste, avec col et revers en hermine. Le haut brodé de galons et de guipure d’or formant boléro. Même galon d’or aux manches. Manches intérieures en mousseline de soie mauve. Agrafe or et opales.

Amethyst velvet coat, with ermine collar and lapels. The top embroidered with gold braid and guipure forming a bolero. Same gold braid on the sleeves. Inner sleeves in mauve chiffon. Gold and opal clasp.

#L'Art et la mode#20th century#1900s#1900#on this day#December 29#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#panorama#description#bibliothèque nationale de france#dress#coat#collar#gutter

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robe du soir 1911

Les Modes (Paris) May 1911 Robe du soir par Drecoll.

Page 19—Mlle Alice Guerra—Robe du soir—Drecoll—Tunique de tulle rose perlé et pailleté d’or, sur un fond de liberty chair ouvert du côté gauche. Côté gauche du corsage en mousseline rose liserée de diamants ; bas de jupe garni d’une haute dentelle d’or.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"On parle souvent des roses, du muguet, des bleuets

Mais une petite fleur dont on ne parle jamais

Dans les prés, chaque année, pousse et pousse encore

C’est une renoncule qu’on appelle bouton-d’or.

Une petite fleur aux cinq pétales d’or

Qui avec ses amies, brillent comme un trésor

Mettent de la gaieté dans les fossés, les champs

Pour le bonheur des yeux des Petits et des Grands

Allons nous promener ce beau matin d’été

Et cueillons pour Maman un beau et gros bouquet

De ces jolies fleurs jaunes comme le beurre ou le miel

Qui remplira son cœur de rayons

de soleil.

Et pour vous amuser, comme tous les enfants,

Sous le menton d’une sœur, d’un ami, d’un parent

Approchez cette fleur et s’il change de couleur

Dites-lui , simplement "Toi, tu aimes le beurre !"

Sauvageonne si belle que tant de personnes aiment !

Il fallait un Poème pour cette fleur suprême"

Maurice CARÊME

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Archive: Review: Chronométrie Ferdinand Berthoud “Oeuvre d’Or” Collection: white gold FB 1.1-2 and rose gold FB 1.2-1

It was not easy to take a decision regarding the first watch to review after SIHH. If you had a look at my SIHH impressions Part1, Part2 and Part 3, you should already have an idea what I have seen. Therefore I decided to start completely random. Why not with one of my preferences. So based only on a feeling given by a random wrist shot – The Ferdinand Berthoud Ref. FB 1.1-2 and, respectively…

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Je lui dis : La rose du jardin, comme tu sais, dure peu ; et la saison des roses est bien vite écoulée. Quand l’Automne, abrégeant les jours qu’elle dévore, Éteint leurs soirs de flamme et glace leur aurore, Quand Novembre de brume inonde le ciel bleu, Que le bois tourbillonne et qu’il neige des feuilles, Ô ma muse ! en mon âme alors tu te recueilles, Comme un enfant transi qui s’approche du feu. Devant le sombre hiver de Paris qui bourdonne, Ton soleil d’orient s’éclipse, et t’abandonne, Ton beau rêve d’Asie avorte, et tu ne vois Sous tes yeux que la rue au bruit accoutumée, Brouillard à ta fenêtre, et longs flots de fumée Qui baignent en fuyant l’angle noirci des toits. Alors s’en vont en foule et sultans et sultanes, Pyramides, palmiers, galères capitanes, Et le tigre vorace et le chameau frugal, Djinns au vol furieux, danses des bayadères, L’Arabe qui se penche au cou des dromadaires, Et la fauve girafe au galop inégal ! Alors, éléphants blancs chargés de femmes brunes, Cités aux dômes d’or où les mois sont des lunes, Imans de Mahomet, mages, prêtres de Bel, Tout fuit, tout disparaît : – plus de minaret maure, Plus de sérail fleuri, plus d’ardente Gomorrhe Qui jette un reflet rouge au front noir de Babel ! C’est Paris, c’est l’hiver. – A ta chanson confuse Odalisques, émirs, pachas, tout se refuse. Dans ce vaste Paris le klephte est à l’étroit ; Le Nil déborderait ; les roses du Bengale Frissonnent dans ces champs où se tait la cigale ; A ce soleil brumeux les Péris auraient froid. Pleurant ton Orient, alors, muse ingénue, Tu viens à moi, honteuse, et seule, et presque nue. – N’as-tu pas, me dis-tu, dans ton coeur jeune encor Quelque chose à chanter, ami ? car je m’ennuie A voir ta blanche vitre où ruisselle la pluie, Moi qui dans mes vitraux avais un soleil d’or !

Puis, tu prends mes deux mains dans tes mains diaphanes ; Et nous nous asseyons, et, loin des yeux profanes, Entre mes souvenirs je t’offre les plus doux, Mon jeune âge, et ses jeux, et l’école mutine, Et les serments sans fin de la vierge enfantine, Aujourd’hui mère heureuse aux bras d’un autre époux.

Je te raconte aussi comment, aux Feuillantines, Jadis tintaient pour moi les cloches argentines ; Comment, jeune et sauvage, errait ma liberté, Et qu’à dix ans, parfois, resté seul à la brune, Rêveur, mes yeux cherchaient les deux yeux de la lune, Comme la fleur qui s’ouvre aux tièdes nuits d’été.

Puis tu me vois du pied pressant l’escarpolette Qui d’un vieux marronnier fait crier le squelette, Et vole, de ma mère éternelle terreur ! Puis je te dis les noms de mes amis d’Espagne, Madrid, et son collège où l’ennui t’accompagne, Et nos combats d’enfants pour le grand Empereur !

Puis encor mon bon père, ou quelque jeune fille Morte à quinze ans, à l’âge où l’oeil s’allume et brille. Mais surtout tu te plais aux premières amours, Frais papillons dont l’aile, en fuyant rajeunie, Sous le doigt qui la fixe est si vite ternie, Essaim doré qui n’a qu’un jour dans tous nos jours.

-poésie: "Novembre", Victor Hugo -image: "The Meeting with Autumn", Vladimir Volegov

#poesie#poetry#french literature#autumn#autumn aesthetic#autumn leaves#fall vibes#autumn vibes#fall aesthetic#autumnal#fallen leaves#fall season#fall leaves#fall#november#sunlight#sunrise#oriental#arab women#ancient egypt#djinn#victor hugo

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rose rose, rose blanche,

Rose thé,

J’ai cueilli la rose en branche

Au soleil de l’été

Rose blanche, rose rose,

Rose d’or,

J’ai cueilli la rose éclose

Et son parfum m’endort.

Robert Desnos

30 notes

·

View notes