#robert graf

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

buddenbrooks, alfred weidenmann 1959

#buddenbrooks#alfred weidenmann#thomas mann#1959#liselotte pulver#hansjörg felmy#nadja tiller#hanns lothar#carsta löck#lil dagover#helga feddersen#wolfgang wahl#robert graf#horst janson#gustav knuth#joseph offenbach#rudolf platte#frühlingssinfonie#the hotel new hampshire

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#buddenbrooks#alfred weidenmann#thomas mann#1959#liselotte pulver#hansjörg felmy#nadja tiller#hanns lothar#carsta löck#lil dagover#helga feddersen#wolfgang wahl#robert graf#horst janson#gustav knuth#joseph offenbach#rudolf platte#frühlingssinfonie#the hotel new hampshire

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nosferatu watching Nosferatu 2024

#Yeah yeah i know his name is count orlok#But for the sake of recognizability#I can't believe Squidferatu is better than Nosferatu 2024 and a much more faithful adaptation compared to whatever bobby egg has cooked up#Disappointed by the leaked script greatly#I ruined the movie for myself#But i am looking forward to the coffin popcorn box :D#the spongebob connoisseur#spongebob squarepants#spongebob#sb#spongebon squarepants#spongebob meme#Nosferatu#Count orlok#Graf orlok#nosferatu eine symphonie des grauens#Nosferatu 2024#Robert Eggers#Nosferatu 1922#nosferatu a symphony of horror

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

uhm. oh my god.😅😳

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Could that have been an option? Did somebody dress up?

#nosferatu#nosferatu - the undead#nosferatu 2024#robert eggers#did you dress up for the nosferatu premiere?#nosferatu movie#bill skarsgård#lily-rose depp#nicholas hoult#graf orlok#ellen hutter#thomas hutter#tomorrow its been a month since the us-premiere

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

His Serene Highness The Count of Münnich and Reutern wishing those of you celebrating a very happy Burns Night tonight.

May your gatherings be filled with the richness of tradition, the melody of verse and the warmth of kinship.

As we honour the immortal bard of Scotland, Robert Burns, let us raise our cups in a resounding Slàinte mhath to the enduring spirit of Scottish culture. May the haggis be plentiful, the whisky flow freely, and the company be as guid an’ braw as the finest of feasts.

Here’s to a night of merriment and poetic reverie!

#burns night#robert burns#count joshua von münnich#members of the royal family#graf von münnich und reutern

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rebecca Dream Cast

As "Rebecca das Musical" connoisseurs™, @edgyparrot and I cooked something up.

We've seen a lot of different versions (never enough) and now we're basically deciding who's best at the characters and putting them in one dream cast.

Ich: Nienke Latten (only from the Wilemijn cast, not with Mark)

Maxim de Winter: Jan Ammann

Mrs Danvers: Pia Douwes (@edgyparrot's love)

Beatrice Lacy: Kerstin Ibald (my love)

Giles Lacy: Raphael Dörr

Frank Crawley: Jörg Neubauer (the chemistry with Jan, omg)

Jack Favell: Hannes Staffler/ Mark Seibert (I know he's theoretically never played Jack, but he basically plays Maxim how I imagine Jack to be, and let's be honest, he would slay)

Ben: Daniele Nonnis

Mrs van Hopper: Isabel Dörfler (our queen <3)

Frith: Matthias Graf

Robert: (forgot his name, will look it up later)

Clarice: Christina Patten

We'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments (but accept no criticism :))

#rebecca das musical#daphne du maurier#pia douwes#jan ammann#nienke latten#kerstin ibald#dream cast#european musicals

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

buddenbrooks, alfred weidenmann 1959 02_02

#buddenbrooks#alfred weidenmann#thomas mann#1959#liselotte pulver#hansjörg felmy#nadja tiller#hanns lothar#carsta löck#lil dagover#helga feddersen#wolfgang wahl#robert graf#horst janson#gustav knuth#joseph offenbach#rudolf platte#material#buw#essen#tp2#pressefreiheit#meinungsfreiheit#die geschichte einer deutschen familie#frühlingssinfonie#kai aus mölln#mölln

1 note

·

View note

Text

I like ya cut g

#spongebob#spongebob squarepants#peter lorre#slappy laszlo#slappy spongebob#spongebob 25th anniversary#Peter lorre fish#The spongebob connoisseur#Doodlebobz#Nosferatu#Count orlok#Graf orlok#Herr knock#Renfield#robert montague renfield#nosferatu eine symphonie des grauens#nosferatu a symphony of horror#Nosferatu spoilers#Nosferatu 2024#nosferatu movie#robert eggers#bill skarsgård#Spongebon sauarepants#Sbsp#Sb#spongebob fanart#Spongebob meme#Spongebob shitpost

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

A class on fairy tales (1)

As you might know (since I have been telling it for quite some times), I had a class at university which was about fairy tales, their history and evolution. But from a literary point of view - I am doing literary studies at university, it was a class of “Literature and Human sciences”, and this year’s topic was fairy tales, or rather “contes” as we call them in France. It was twelve seances, and I decided, why not share the things I learned and noted down here? (The titles of the different parts of this post are actually from me. The original notes are just a non-stop stream, so I broke them down for an easier read)

I) Book lists

The class relied on a main corpus which consisted of the various fairytales we studied - texts published up to the “first modernity” and through which the literary genre of the fairytale established itself. In chronological order they were: The Metamorphoses of Apuleius, Lo cunto de li cunti by Giambattista Basile, Le Piacevoli Notti by Giovan Francesco Straparola, the various fairytales of Charles Perrault, the fairytales of Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, and finally the Kinder-und Hausmärchen of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. There is also a minor mention for the fables of Faerno, not because they played an important historical role like the others, but due to them being used in comparison to Perrault’s fairytales ; there is also a mention of the fairytales of Leprince de Beaumont if I remember well.

After giving us this main corpus, we were given a second bibliography containing the most famous and the most noteworthy theorical tools when it came to fairytales - the key books that served to theorize the genre itself. The teacher who did this class deliberatly gave us a “mixed list”, with works that went in completely opposite directions when it came to fairytale, to better undersant the various differences among “fairytale critics” - said differences making all the vitality of the genre of the fairytale, and of the thoughts on fairytales. Fairytales are a very complex matter.

For example, to list the English-written works we were given, you find, in chronological order: Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment ; Jack David Zipes’ Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion ; Robert Bly’s Iron John: A Book about Men ; Marie-Louise von Franz, Interpretation of Fairy Tales ; Lewis C. Seifert, Fairy Tales, Sexuality and Gender in France (1670-1715) ; and Cristina Bacchilega’s Postmodern Fairy Tales: Gender and Narrative Strategies. If you know the French language, there are two books here: Jacques Barchilon’s Le conte merveilleux français de 1690 à 1790 ; and Jean-Michel Adam and Ute Heidmann’s Textualité et intertextualité des contes. We were also given quite a few German works, such as Märchenforschung und Tiefenpsychologie by Wilhelm Laiblin, Nachwort zu Deutsche Volksmärchen von arm und reich, by Waltraud Woeller ; or Märchen, Träume, Schicksale by Otto Graf Wittgenstein. And of course, the bibliography did not forget the most famous theory-tools for fairytales: Vladimir Propp’s Morfologija skazki + Poetika, Vremennik Otdela Slovesnykh Iskusstv ; as well as the famous Classification of Aarne Anti, Stith Thompson and Hans-Jörg Uther (the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Classification, aka the ATU).

By compiling these works together, one will be able to identify the two main “families” that are rivals, if not enemies, in the world of the fairytale criticism. Today it is considered that, roughly, if we simplify things, there are two families of scholars who work and study the fairy tales. One family take back the thesis and the theories of folklorists - they follow the path of those who, starting in the 19th century, put forward the hypothesis that a “folklore” existed, that is to say a “poetry of the people”, an oral and popular literature. On the other side, you have those that consider that fairytales are inscribed in the history of literature, and that like other objects of literature (be it oral or written), they have intertextual relationships with other texts and other forms of stories. So they hold that fairytales are not “pure, spontaneous emanations”. (And given this is a literary class, given by a literary teacher, to literary students, the teacher did admit their bias for the “literary family” and this was the main focus of the class).

Which notably led us to a third bibliography, this time collecting works that massively changed or influenced the fairytale critics - but this time books that exclusively focused on the works of Perrault and Grimm, and here again we find the same divide folklore VS textuality and intertextuality. It is Marc Soriano’s Les contes de Perrault: culture savante et traditions populaires, it is Ernest Tonnelat’s Les Contes des frères Grimm: étude sur la composition et le style du recueil des Kinder-und-Hausmärchen ; it is Jérémie Benoit’s Les Origines mythologiques des contes de Grimm ; it is Wilhelm Solms’ Die Moral von Grimms Märchen ; it is Dominqiue Leborgne-Peyrache’s Vies et métamorphoses des contes de Grimm ; it is Jens E. Sennewald’ Das Buch, das wir sind: zur Poetik der Kinder und-Hausmärchen ; it is Heinz Rölleke’s Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm: eine Einführung. No English book this time, sorry.

II) The Germans were French, and the French Italians

The actual main topic of this class was to consider the “fairytale” in relationship to the notions of “intertextuality” and “rewrites”. Most notably there was an opening at the very end towards modern rewrites of fairytales, such as Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, “Le petit chaperon vert” (Little Green Riding Hood) or “La princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes” (The princess who didn’t like princes). But the main subject of the class was to see how the “main corpus” of classic fairytales, the Perrault, the Grimm, the Basile and Straparola fairytales, were actually entirely created out of rewrites. Each text was rewriting, or taking back, or answering previous texts - the history of fairytales is one of constant rewrite and intertextuality.

For example, if we take the most major example, the fairytales of the brothers Grimm. What are the sources of the brothers? We could believe, like most people, that they merely collected their tale. This is what they called, especially in the last edition of their book: they claimed to have collected their tales in regions of Germany. It was the intention of the authors, it was their project, and since it was the will and desire of the author, it must be put first. When somebody does a critical edition of a text, one of the main concerns is to find the way the author intended their text to pass on to posterity. So yes, the brothers Grimm claimed that their tales came from the German countryside, and were manifestations of the German folklore.

But... in truth, if we look at the first editions of their book, if we look at the preface of their first editions, we discover very different indications, indications which were checked and studied by several critics, such as Ernest Tomelas. In truth, one of their biggest sources was... Charles Perrault. While today the concept of the “tales of the little peasant house, told by the fireside” is the most prevalent one, in their first edition the brothers Grimm explained that their sources for these tales were not actually old peasant women, far from it: they were ladies, of a certain social standing, they were young women, born of exiled French families (because they were Protestants, and thus after the revocation of the édit de Nantes in France which allowed a peaceful coexistance of Catholics and Protestants, they had to flee to a country more welcoming of their religion, aka Germany). They were young women of the upper society, girls of the nobility, they were educated, they were quite scholarly - in fact, they worked as tutors/teachers and governess/nursemaids for German children. For children of the German nobility to be exact. And these young French women kept alive the memory of the French literature of the previous century - which included the fairytales of Perrault.

So, through these women born of the French emigration, one of the main sources of the Grimm turns out to be Perrault. And in a similar way, Perrault’s fairytales actually have roots and intertextuality with older tales, Italian fairytales. And from these Italian fairytales we can come back to roots into Antiquity itself - we are talking Apuleius, and Virgil before him, and Homer before him, this whole classical, Latin-Greek literature. This entire genealogy has been forgotten for a long time due to the enormous surge, the enormous hype, the enormous fascination for the study of folklore at the end of the 19th century and throughout all of the 20th.

We talk of “types of fairytales”, if we talk of Vladimir Propp, if we talk of Aarne Thompson, we are speaking of the “morphology of fairytales”, a name which comes from the Russian theorician that is Propp. Most people place the beginning of the “structuralism” movement in the 70s, because it is in 1970 that the works of Propp became well-known in France, but again there is a big discrepancy between what people think and what actually is. It is true that starting with the 70s there was a massive wave, during which Germans, Italians and English scholars worked on Propp’s books, but Propp had written his studies much earlier than that, at the beginning of the 20th century. The first edition of his Morphology of fairytales was released in 1928. While it was reprinted and rewriten several times in Russia, it would have to wait for roughly fifty years before actually reaching Western Europe, where it would become the fundamental block of the “structuralist grammar”. This is quite interesting because... when France (and Western Europe as a whole) adopted structuralism, when they started to read fairytales under a morphological and structuralist angle, they had the feeling and belief, they were convinced that they were doing a “modern” criticism of fairytales, a “new” criticism. But in truth... they were just repeating old theories and conceptions, snatched away from the original socio-historical context in which Propp had created them - aka the Soviet Union and a communist regime. People often forget too quickly that contextualizing the texts isn’t only good for the studied works, we must also contextualize the works of critics and the analysis of scholars. Criticism has its own history, and so unlike the common belief, Propp’s Morphology of fairytales isn’t a text of structuralist theoricians from the 70s. It was a text of the Soviet Union, during the Interwar Period.

So the two main questions of this class are. 1) We will do a double exploration to understand the intertextual relationships between fairytales. And 2) We will wonder about the definition of a “fairytale” (or rather of a “conte” as it is called in French) - if the fairytale is indeed a literary genre, then it must have a definition, key elements. And from this poetical point of view, other questions come forward: how does one analyze a fairytale? What does a fairytale mean?

III) Feuding families

Before going further, we will pause to return to a subject talked about above: the great debate among scholars and critics that lasted for decades now, forming the two branches of the fairytale study. One is the “folklorist” branch, the one that most people actually know without realizing it. When one works on fairytale, one does folklorism without knowing it, because we got used to the idea that fairytale are oral products, popular products, that are present everywhere on Earth, we are used to the concept of the universality of motives and structures of fairytales. In the “folklorist” school of thought, there is an universalism, and not only are fairytales present everywhere, but one can identify a common core for them. It can be a categorization of characters, it can be narrative functions, it can be roles in a story, but there is always a structure or a core. As a result, the work of critics who follow this branch is to collect the greatest number of “versions” of a same tale they can find, and compare them to find the smallest common denominator. From this, they will create or reconstruct the “core fairytale”, the “type” or the “source” from which the various variations come from.

Before jumping onto the other family, we will take a brief time to look at the history of the “folklorist branch” of the critic. (Though, to summarize the main differences, the other family of critics basically claims that we do not actually know the origin of these stories, but what we know are rather the texts of these stories, the written archives or the oral records).

So the first family here (that is called “folklorist” for the sake of simplicity, but it is not an official or true appelation) had been extremely influenced by the works of a famous and talented scholar of the early 20th century: Aarne Antti, a scholar of Elsinki who collected a large number of fairytales and produced out of them a classification, a typology based on this theory that there is an “original fairytale type” that existed at the beginning, and from which variants appeared. His work was then continued by two other scholars: Stith Thompson, and Hans-Jörg Uther. This continuation gave birth to the “Aarne-Thompson” classification, a classification and bibliography of folkloric fairytales from around the world, which is very often used in journals and articles studying fairytales. Through them, the idea of “types” of fairytales and “variants” imposed itself in people’s minds, where each tale corresponds to a numbered category, depending on the subjects treated and the ways the story unfolds (for example an entire category of tale collects the “animal-husbands”. This classification imposed itself on the Western way of thinking at the end of the first third of the 20th century.

The next step in the history of this type of fairytale study was Vladimir Propp. With his Morphology of fairytales, we find the same theory, the same principle of classification: one must collect the fairytales from all around the world, and compare them to find the common denominator. Propp thought Aarne-Thompson’s work was interesting, but he did complain about the way their criteria mixed heterogenous elements, or how the duo doubled criterias that could be unified into one. Propp noted that, by the Aarne-Thompson system, a same tale could have two different numbers - he concluded that one shouldn’t classify tales by their subject or motif. He claimed that dividing the fairytales by “types” was actually impossible, that this whole theory was more of a fiction than an actual reality. So, he proposed an alternate way of doing things, by not relying on the motifs of fairytales: Propp rather relied on their structure. Propp doesn’t deny the existence of fairytales, he doesn’t put in question the categorization of fairytales, or the universality of fairytales, on all that he joins Aarne-Thompson. But what he does is change the typology, basing it on “functions”: for him, the constituve parts of fairytales are “functions”, which exist in limited numbers and follow each other per determined orders (even if they are not all “activated”). He identified 31 functions, that can be grouped into three groups forming the canonical schema of the fairytale according to Propp. These three groups are an initial situation with seven functions, followed by a first sequence going from the misdeed (a bad action, a misfortune, a lack) to its reparation, and finally there is a second sequence which goes from the return of the hero to its reward. From these seven “preparatory functions”, forming the initial situation, Propp identified seven character profiles, defined by their functions in the narrative and not by their unique characteristics. These seven profiles are the Aggressor (the villain), the Donor (or provider), the Auxiliary (or adjuvant), the Princess, the Princess’ Father, the Mandator, the Hero, and the False Hero. This system will be taken back and turned into a system by Greimas, with the notion of “actants”: Greimas will create three divisions, between the subject and the object, between the giver and the gifted, and between the adjuvant and the opposant.

With his work, Vladimir Propp had identified the “structure of the tale”, according to his own work, hence the name of the movement that Propp inspired: structuralism. A structure and a morphology - but Propp did mention in his texts that said morphology could only be applied to fairytales taken from the folklore (that is to say, fairytales collected through oral means), and did not work at all for literary fairytales (such as those of Perrault). And indeed, while this method of study is interesting for folkloric fairytales, it becomes disappointing with literary fairytales - and it works even less for novels. Because, trying to find the smallest denominator between works is actually the opposite of literary criticism, where what is interesting is the difference between various authors. It is interesting to note what is common, indeed, but it is even more interesting to note the singularities and differences. Anyway, the apparition of the structuralist study of fairytales caused a true schism among the field of literary critics, between those that believe all tales must be treated on a same way, with the same tools (such as those of Propp), and those that are not satisfied with this “universalisation” that places everything on the same level.

This second branch is the second family we will be talking about: those that are more interested by the singularity of each tale, than by their common denominators and shared structures. This second branch of analysis is mostly illustrated today by the works of Ute Heidmann, a German/Swiss researcher who published alongside Jean Michel Adam (a specialist of linguistic, stylistic and speech-analysis) a fundamental work in French: Textualité et intertextualité des contes: Perrault, Apulée, La Fontaine, Lhéritier... (Textuality and intertextuality of fairytales). A lot of this class was inspired by Heidmann and Adam’s work, which was released in 2010. Now, this book is actually surrounded by various articles posted before and after, and Ute Heidmann also directed a collective about the intertextuality of the brothers Grimm fairytales. Heidmann did not invent on her own the theories of textuality and intertextuality - she relies on older researches, such as those of the Ernest Tonnelat, who in 1912 published a study of the brothers Grimm fairytales focusing on the first edition of their book and its preface. This was where the Grimm named the sources of their fairytales: girls of the upper class, not at all small peasants, descendants of the protestant (huguenots) noblemen of France who fled to Germany. Tonnelat managed to reconstruct, through these sources, the various element that the Grimm took from Perrault’s fairytales. This work actually weakened the folklorist school of thought, because for the “folklorist critics”, when a similarity is noted between two fairytales, it is a proof of “an universal fairytale type”, an original fairytale that must be reconstructed. But what Tonnelat and other “intertextuality critics” pushed forward was rather the idea that “If the story of the Grimm is similar but not identical to the one of Perrault, it is because they heard a modified version of Perrault’s tale, a version modified either by the Grimms or by the woman that told them the tale, who tried to make the story more or less horrible depending on the situation”. This all fragilized the idea of an “original, source-fairytale”, and encouraged other researchers to dig this way.

For example, the case was taken up by Heinz Rölleke, in 1985: he systematized the study of the sources of the Grimm, especially the sources that tied them to the fairytales of Perrault. Now, all the works of this branch of critics does not try to deny or reject the existence of fairytales all over the world. And it does not forget that all over the world, human people are similar and have the same preoccupations (life, love, death, war, peace). So, of course, there is an universality of the themes, of the motives, of the intentions of the texts. Because they are human texts, so there is an universality of human fiction. But there is here the rejection of a topic, a theory, a question that can actually become VERY dangerous. (For example, in post World War II Germany, all researches about fairytales were forbidden, because during their reign the Nazis had turned the fairytales the Grimm into an abject ideological tool). This other family, vein, branch of critics, rather focuses on the specificity of each writing style, of each rewrite of a fairytale, but also on the various receptions and interpretations of fairytales depending on the context of their writing and the context of their reading. So the idea behind this “intertextuality study” is to study the fairytales like the rest of literature, be it oral or written, and to analyze them with the same philological tools used by history studies, by sociology study, by speech analysis and narrative analysis - all of that to understand what were the conditions of creation, of publication, of reading and spreading of these tales, and how they impacted culture.

#fairy tales#fairytales#fairytale#fairy tale#a class on fairytales#brothers grimm#grimm fairytales#charles perrault#perrault fairytales#history of fairytales#vladimir propp#aarne-thompson classification#aarne-thompson#analysis of fairytales#critics of fairytales#book reference#sources#fairytale research#literary vs folklorist#which actually should be more intertextuality vs folklorist

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Truly the SpongeBob frame of all time

#No amount of context will save this#Fun fact! This aired on Valentine's day#spongebob squarepants#spongebob#sb#spongebon squarepants#spongebob meme#slappy laszlo#slappy spongebob#laszlo spongebob#Peter lorre fish#Nosferatu#Count orlok#Graf orlok#Dracula#Renfield#robert montague renfield#dracfield#Slapferatu#Sbsp#New meaning to pet fish#Anime convention ahh activities#The spongebob connoisseur

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

they r so cute

#what r they discussing??#robert d marx#marc liebisch#herbert von krolock#tanz der vampire#graf von krolock#tanzsaal

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite Sampling / Crate-Digging / Classic Finds For The 2010’s.

Walt Barr “Free Spirit”

Azymuth “Jazz Carnival”

Reg Tilsley “Hold The Road”

Willie Bobo “Kojak Theme”

Bobby Lyle “Inner Space”

Marcio Montarroyos “Pedra Bonilla”

Rubba “Way Star”

Eddie Henderson “Involuntary Bliss”

Jaye P. Morgan “It’s Been So Long“

Eric Gale “Morning Glory”

Tribe “Koke Pt. I & II”

Urbie Green The Fox

Hysear Don Walker “Poo Jo”

Weldon Irvine “Morning Sunrise”

Unit Nine “Night Light”

Larry Bright “Solar Visions”

Sun Ra Nuits De La Fondation Maeght Vol. 1

Gary Davis & His Professor “Stay With Me”

L.A. Boppers “Saturday”

Pop Eye “Lazy Haze”

Phil Upchurch “Black Gold”

Ronnie Laws “Always There”

Sauver Mallia “Future Vision”

Sweet Mixture “House Of Fun And Love”

Tantor “Niederwohren”

Catalyst “New-Found Truths”

Brian Bennett & Alan Hawkshaw “Mermaid”

Clive Hicks “Deserted Factory”

Alan Parker & Alan Hawkshaw “The Difference”

Jack Wilkins “Red Clay”

James Clarke “In Suspension”

Negril self-titled

Blackbyrds, The “Mysterious Vibes”

Bill Loose “Almost Sixteen”

Robert Ashley “Purposeful Lady Slow Afternoon”

Steve Khan “The Blue Man”

Puccio Roelens “A Silness Song”

Robert Viger “Limpidite”

Ramsey Lewis “Skippin’”

Alan Hawkshaw “Cruising”

Keith Mansfield “Love De Luxe”

General Lee & The Space Army Band “We Did It Baby Pt. 1 & 2”

Tony Hymas “Final Inspecton”

Antonio Andolfo Feito Em Casa

James Clarke “Waiting Game”

Alan Hawkshaw “Blue Note”

Bob James “Angela”

Tom Scott “Appolonia (Foxtrata)”

Alan Parker & Mike Moran “Your Smile”

Ethel Beatty “Your Love”

Keith Droste “When You Come Around”

Ojeda Penn “Happiness Is Having You Here”

Walt Barr “Creepin’”

Brass Construction “Don’t Try To Change Me”

Sylvano Santorio “Waves”

William Onyeabor “Better Change Your Mind”

Puccio Roelens “Northern Lights”

Ramsey Lewis “Tambura”

Blackbyrds, The “Mysterious Vibes”

Champaign “I’m On Fire”

Starfire “Make The Most of It”

Dick Walter “The Fat Man”

Don Patterson “The Good Life”

Maynard Ferguson “Mister Mellow”

Death “David’s Dream”

Vic Juris “Leah”

Ramsey Lewis “Sun Goddess”

Stuff “Sun Song”

Nancy Wilson ”I’m In Love”

Undisputed Truth, The “Smiling Faces Sometimes”

Heatwave “Leaving For A Dream”

Eddie Henderson “Beyond Forever”

Keith Mansfield “Routine Procedure”

Players’ Association, The “Moon In Pisces”

Jaye P. Morgan “Can’t Hide Love”

Bill Loose “Slight Misgivings”

Bernice Chardiet / Martha Hayes “All By Myself“

Steve Khan “Darling Darling Baby (Sweet Tender Love)”

Gordon’s War “Got To Fan The Flame”

McNeal & Miles “Ja Ja”

Annette Peacock & Paul Bley “A Loss Of Consciousness”

Alan Hawkshaw “Mystique Voyage”

Big Barney “The Whole Damn Thing”

General Lee & The Space Army Band “Magic”

Gene Harris “Losalamitoslatinfunklovesong”

Tomorrow’s People “Open Soul”

Blackbyrds, The “Love Is Love”

Chick Carlton & Mesmeriah “One More Time With Feeling”

Cortex “Huit Octobre”

Flora Purim “Angels”

Francis Monkman “Getting Ready”

Frank Ricotti “Vibes”

Herbie Hancock “Butterfly”

James Mason “I Want Your Love”

Franco Micalizzi “Jessica’s Theme”

Manzel “Midnight Theme”

Sass “I Only Wanted To Love You”

Stars & Bars “Stars And Bars”

Sunburst “Mysterious Vibes”

Mass Production “Slow Bump”

Peter Brown “For Your Love”

Bobby Lyle “Night Breeze”

Brian Bennett “Morning”

Vic Juris “Horizon Drive”

Hailu Mergia & The Walias (ft. Mulatu Astatke) “Yemiasleks Fikir”

Bereket Mengistaab “Lebay”

LaMont Johnson Aces

Alan Hawkshaw “Warm Hearts”

Heatwave “Star Of The Story”

Pasteur Lappe “Mbale (Face To Face With The Truth)”

Joe Beck & David Sanborn “Texas Ann”

Jon Lucien “Sunny Day”

Players’ Association, The “Turn The Music Up!”

Richie Cole “New York Afternoon”

Rufus & Chaka Khan “Your Smile”

Shuggie Otis “Pling!”

Alice Coltraine “Galaxy In Turiya”

Stuff “And Here You Are”

Pharoah Sanders “Greeting to Saud (Brother McCoy Tyner)”

Edgar Vercy “La Mer”

Fa-5 self-titled

Iodi “Sonrie”

Joe Moks Boys And Girls

Blackbyrds, The “Lady”

Teddy Lasry “Riverhead”

Brothers Johnson “Tomorrow”

Håkon Graf & Sveinung Hovensjø & Jon Eberson & Jon Christensen “Alive Again”

Favorite Sampling / Crate-Digging / Classic Finds For The Oughts.

Donny Hathaway ��Singing This Song To You”

Esther Phillips “That’s All Right With Me”

Gil Scott-Heron “We Almost Lost Detroit”

Isaac Hayes “Hung Up On My Baby”

Marvin Gaye “I Want You” (inst.)

David Axelrod “Warning Pts. 1 & 2”

Pharoah Sanders “Creator Has A Master Plan, The”

Lonnie Liston Smith “Expansions”

Kool & The Gang “Summer Madness”

Roy Ayers Virgin Ubiquity I & II

Rotary Connection “Memory Band”

Cal Tjader “Morning Mist”

Dave Grusin “Either Way”

RAMP “Daylight”

Gil Scott-Heron “A Very Precious Time”

Sun Ra “Yucatan” (Saturn ver.)

Edwin Birdsong “Cola Bottle Baby”

Kool & The Gang “Summer Madness” (live)

Neil Richardson “The Riviera Affair”

Roy Ayers Ubiquity “Show Us A Feeling”

Persuaders, The “We’re Just Trying To Make It”

Sun Ra “Enlightenment”

Les McCann River High River Low

Minnie Riperton“Lovin’ You”

Floaters, The “Float On”

Roy Ayers Ubiquity “Miles (Love’s Silent Dawn)”

Les McCann Layers

John Tropea A Short Trip To Space

Lonnie Liston Smith & The Cosmic Echoes Astral Traveling

Chick Corea“Crystal Silence”

Richard “Groove” Holmes “Onsaya Joy”

Gil Scott-Heron & Brian JacksonWinter In America

Delegation“Oh, Honey”

Heatwave “Always And Forever”

Olympic Runners “Don’t Let Up”

Kool & The Gang “Winter Sadness”

Ronnie Laws “Tidal Wave”

Parliament Funkadelic “One Of Those Funky Things”

Roy Ayers A Tear To A Smile

Galt McDermott Ripped Open By Metal Explosion

Idris Muhammad “Crab Apple”

Alan Parker & John CameronAfro Rock

Beginning Of The EndFunky Nassau

Otto Cesana “Hi”

Syd Dale “Cuban Presto”

Chambers Brothers, The “New Generation”

Chick Corea Friends

Edwin Birdsong “Rapper Dapper Snapper”

Jerry Butler “Got To See If I Can’t Get Momma (To Come Back Home)”

Karla Bonoff Restless Nights

Phil Upchurch self-titled

Roy Ayers (Ubiquity) “This Side Of Sunshine”

Billy Cobham “Heather”

Bill Conti “Reflections”

Andre Previn “Executive Party Dance”

Lonnie Liston Smith & The Cosmic Echoes Vision Of A New World

London West End Theatre Orchestra“Apollo 15 (Race Leader)”

#samping#crat-digging#vinyl#records#treasure#jazz#fusion#soul#R&B#groove#funk#omega#music#playlists#mixtapes

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday Robert Graf

1923 - 1966

Robert Graf as Werner in The Great Escape

In The Great Escape Robert Graf played Werner, a Ferret stationed at Stalag Luft 3 who Eagle Squadron pilot Hendley (James Garner) befriends in order to later steal from and bribe him into assisting with materials for the escape.

Werner tells Hendley that he is afraid of being sent to the Eastern Front but in real life Robert Graf served on the Eastern front from 1942-1944 when he was 19-21 years old but after being wounded he was resigned to defence production duties. He then went on to study theatre and film and appeared in his first film in 1952.

There were at least two different versions of The Great Escape Script. The first, written in 1962, was very different to the finished script which was clearly changed when the film was cast as it included characters which do not appear in the film and some characters have been changed.

1962 Version

1963 Version

One reason for the changes to the first version was the cast members themselves of who a few of them had been prisoners of war during WW2 including Donald Pleasence who played Colin Blythe and Hannes Messemer who played Colonel von Luger. The cast were able to give an insight on life as a POW during the war.

One difference between the scripts was that in the first version the German sergeant and Ferrets including Werner were actually noted to have been sent to the Eastern Front after the escape. In real life no enlisted ranks or NCOs were punished for the escape although men did leave the camp to join the front lines due to being called up.

Robert Graf died of cancer at 42 years old just a few years after appearing in The Great Escape.

On another note there is a very small fandom for The Great Escape with some great fanfics on A03 and older sites which I would recommend if anyone is interested.

#the great escape#stalag luft iii#ww2 germany#ww2#Werner the ferret#The Hendley x Werner fandom possibly consists of just myself

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The adventures of two amiably aimless metal-head friends, Wayne and Garth. From Wayne’s basement, the pair broadcast a talk-show called “Wayne’s World” on local public access television. The show comes to the attention of a sleazy network executive who wants to produce a big-budget version of “Wayne’s World”—and he also wants Wayne’s girlfriend, a rock singer named Cassandra. Wayne and Garth have to battle the executive not only to save their show, but also Cassandra. Credits: TheMovieDb. Film Cast: Wayne Campbell: Mike Myers Garth Algar: Dana Carvey Benjamin Kane: Rob Lowe Cassandra: Tia Carrere Stacy: Lara Flynn Boyle Dreamwoman: Donna Dixon Security Guard: Chris Farley Noah Vanderhoff: Brian Doyle-Murray Alan: Michael DeLuise Tiny: Meat Loaf Bad Cop / T-1000: Robert Patrick Alice Cooper: Alice Cooper Glen: Ed O’Neill Mrs. Vanderhoff: Colleen Camp Terry: Lee Tergesen Russell Finley: Kurt Fuller Davy: Mike Hagerty Ron Paxton: Charles Noland Elyse: Ione Skye Frankie Sharp: Frank DiLeo Waitress: Robin Ruzan Officer Koharski: Frederick Coffin Old Man Withers: Carmen Filpi Film Crew: Original Music Composer: J. Peter Robinson Screenplay: Mike Myers Executive Producer: Hawk Koch Director of Photography: Theo van de Sande Director: Penelope Spheeris Producer: Lorne Michaels Editor: Malcolm Campbell Stunts: Hannah Kozak Stunts: Alisa Christensen Associate Producer: Dinah Minot Associate Producer: Barnaby Thompson Screenplay: Bonnie Turner Screenplay: Terry Turner Casting: Glenn Daniels Production Design: Gregg Fonseca Second Unit Director: Allan Graf First Assistant Director: John Hockridge Second Assistant Director: Joseph J. Kontra Set Decoration: Jay Hart Camera Operator: Martin Schaer “B” Camera Operator: David Hennings First Assistant Camera: Henry Tirl First Assistant “B” Camera: Peter Mercurio Steadicam Operator: Elizabeth Ziegler Script Supervisor: Adell Aldrich Sound Mixer: Tom Nelson Boom Operator: Jerome R. Vitucci Additional Editor: Earl Ghaffari Assistant Editor: Ralph O. Sepulveda Jr. Assistant Editor: Ann Trulove Assistant Editor: Brion McIntosh Supervising Sound Editor: John Benson Sound Effects Editor: Beth Sterner Sound Effects Editor: Joseph A. Ippolito Sound Effects Editor: Frank Howard Dialogue Editor: Michael Magill Dialogue Editor: Simon Coke Dialogue Editor: Bob Newlan Supervising ADR Editor: Allen Hartz Foley Supervisor: Pamela Bentkowski Assistant Sound Editor: Carolina Beroza Assistant Sound Editor: Thomas W. Small Foley Artist: Ken Dufva Foley Artist: David Lee Fein Foley Mixer: Greg Curda ADR Mixer: Bob Baron ADR Voice Casting: Barbara Harris Sound Re-Recording Mixer: Andy Nelson Sound Re-Recording Mixer: Steve Pederson Sound Re-Recording Mixer: Tom Perry Music Supervisor: Maureen Crowe Supervising Music Editor: Steve Mccroskey Set Designer: Lisette Thomas Set Designer: Gae S. Buckley Special Effects Makeup Artist: Thomas R. Burman Special Effects Makeup Artist: Bari Dreiband-Burman Makeup Artist: Courtney Carell Makeup Artist: Mel Berns Jr. Hairstylist: Kathrine Gordon Hairstylist: Barbara Lorenz Hairstylist: Carol Meikle Costume Supervisor: Pat Tonnema Costumer: Janet Sobel Costumer: Kimberly Guenther Durkin Location Manager: Ned R. Shapiro Assistant Location Manager: Serena Baker Second Second Assistant Director: John G. Scotti Property Master: Kirk Corwin Assistant Property Master: Peter A. Tullo Assistant Property Master: Jim Stubblefield Leadman: Robert Lucas Special Effects Coordinator: Tony Vandenecker Chief Lighting Technician: Jono Kouzouyan Production Office Coordinator: Lynne White Unit Publicist: Tony Angelotti Still Photographer: Suzanne Tenner Craft Service: Vartan Chakarian Transportation Coordinator: James Thornsberry Color Timer: David Bryden Negative Cutter: Theresa Repola Mohammed Title Designer: Dan Curry Second Unit Director of Photography: Robert M. Stevens Stunts: Tony Brubaker Stunt Double: Steve Kelso Movie Reviews: tmdb15435519: I wish I could dress the exact same every day and still be cool.

#aftercreditsstinger#best friends#breaking the fourth wall#buddy#duringcreditsstinger#heavy metal#multiple endings#parody#romantic rivalry#singer#television producer#Top Rated Movies#woman director

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

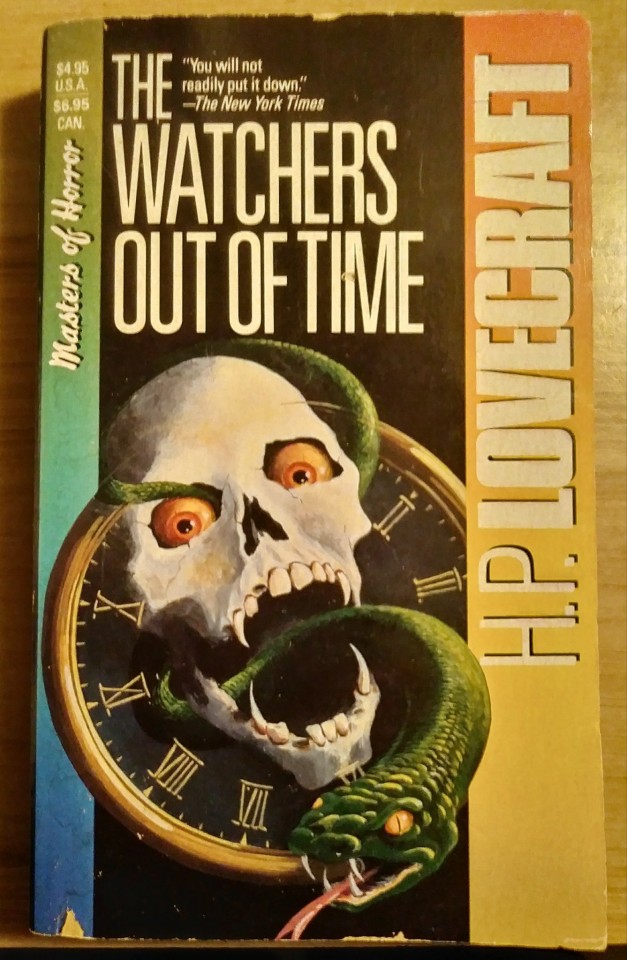

A softcover volume collecting 15 tales of horror promoted as the work of H. P. Lovecraft. Actually the entire contents of the book were almost completely the work of August W. Derleth. To keep interest in Lovecraft from waning Derleth promoted the falsehood that he and HPL had been writing partners and confidants for years before Lovecraft's death. Many new to the whole history of Lovecraft's life and legacy would be surprised to know that the two men never met face to face! Certainly Derleth worked hard to preserve and promote the Lovecraft legend, but he confused things very seriously in doing so. Derleth took control of all things 'Lovecraft' after the masters death in 1937. He moved quickly to be the head-man of Lovecraft's legacy wrestling control (gently perhaps) from Lovecaft's own choice for literary executor Robert Barlow. In Derleth's defense he worked tirelessly to gain this position of control and invested much of his own funds to achieve that position. Certainly Derleth, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Bloch, E. Hoffmann Price, and Frank Belknap Long, (all writers themselves) recognized the depth of the genius in Lovecraft's work. All of these men had received numerous letters from Lovecraft over the years and were also treated to his opinions on so many subjects. HPL's erudition was on full display in his correspondence to his writer friends as well. The book shown was printed by Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc. New York. This third printing was from 1993. I could find no credit for the cover art listed. (Exhibit 346)

15 notes

·

View notes