Stef/Steffi, She/HerCornwall UKWW2 Germans The German Resistance Downfall Parodies and Downfall Actors

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Useful resources on the German Military Resistance during WW2

Memorial to those executed at the Bendlerblock without trial on 20th July 1944.

First of all I have to apologise for not updating lately but unfortunately I am under a great deal of stress at the moment with some family issues which have left me completely exhausted and with very little time to myself at all. I really hope I can pick up writing again soon.

Since today is the 81st anniversary of the assassination attempt on Hitler’s life at The Wolf’s Lair in Rastenburg, East Prussia, I want to at least make the time to leave you, for now, with some useful resources on the German military resistance.

It can be frustrating when the focus of so much written on the subject of the German resistance is reduced to purely the events of 20th July 1944 or where the only key person mentioned in any detail is Claus von Stauffenberg. Such articles, although still useful, marginalise others who held more honourable motives and those active in the years before the shift to him becoming the figurehead of the resistance.

Still, it was Stauffenberg's connections to many within the Wehrmacht’s General Staff which he was able to recruit from and his role within the reserve army that gave him close proximity to Hitler and access to the Valkyrie orders that allowed for a coup which could stand a chance of success.

I have compiled a short list of resources which may be useful to those who want more information on the background and motives of other key conspirators, the scale of the resistance and how it started in the 1930’s at a time when professional army officers who's careers had been held back by the Versailles Treaty were keen to benefit from Hitler's promises.

Books on the military resistance

An Honourable Defeat by Anton Gill (1994) - A thorough account of resistance activity from both civilians and the military within Germany from 1933 onwards. It looks into how opposition within the army began and the varying reasons behind resisting the Nazis and the risks involved. It also highlights the allied reaction to the failed coup. The book includes a detailed timeline of events and a who’s who guide.

Treason by Brian Walters (2024) - Although this book does focus on the life of Claus von Stauffenberg it still covers the rise of resistance from the beginning of the Nazi era. Stauffenberg’s early background is told in detail and it explains how/why the leadership of the military resistance was eventually passed from others to him, ending with a graphic description of the trials of the conspirators by the People’s Court, their deaths within Plötzensee Prison and Nina von Stauffenberg’s imprisonment within Ravensbrook. This book is useful for those who prefer a story format to a reference book and is also available for free as a podcast on Audible which I highly recommend.

Courageous Hearts by Dorethee von Meding (2008) - Interviews with women involved and connected to the German resistance. The women describe their experiences of the Nazi era and the war, what they remember about key conspirators, their own involvement with the resistance and what life was like for them and their children in the post war years.

Saving Munich 1945 by Lesley Yarrangton (2020) - In 1945 a British reporter Noel Newsome was forbidden from publishing a report on the Munich uprising where Wehrmacht, Volkssturm and citizens staged a revolt against their local Nazi leaders in April 1945 as the allies didn’t want to muddy the press at such a crucial time with an article that proposed that there had been Germans who were anti-Nazi. This book contains the findings from Newsome’s article which was only published after his death in 2018.

Movies and Documentaries

Stauffenberg/Operation Valkyrie (2004) -

youtube

Stauffenberg is a German film (in English) and has a good degree of honesty about the person the man was and goes into some detail about his motives and those of key conspirators. Since it is a movie it still contains an certain element of dramatisation.

Valkyrie (2008) -

Valkyrie (with Tom Cruise) tells the same story beginning with Henning von Tresckow's Operation Flash in 1943. It becomes heavily dramatised at key moments as most Hollywood movies tend to do and avoids looking into the motives of the characters but it still has a good degree of historical accuracy if you are simply looking for an overview of events. The well known British/German actors make the film worth a watch.

Die Stunde Der Offiziere (The hour of the officers) (2004) - This is a German documentary (available with English subtitles) which acts out the key events in detail from 1943 and is interwoven with interviews from surviving members of the resistance (at the time) including some of those from the 1943/early 1944 assassination plots which I mentioned in an earlier post soldiers-willing-to-commit-suicide-to-kill-hitler.

youtube

Robert Bernardis - A Forgotten Hero (2018) - This is an Austrian documentary focusing on a lesser known person involved in the July plot, Robert Bernardis, who helped draw up the plans to seize control from the Nazis in Vienna and was executed in August 1944. His family tell the story of how Bernardis was perceived in Austria in the years after the war and how it affected them. It also contains a reconstruction of the bomb explosion to determine what the chance of success was likely to have been as well as archive footage from those who remembered the events at the Bendlerblock.

youtube

Hostages of the SS (2015) - A movie documentary about the families of those arrested after the July coup under Sippenhaft (family guilt clause) and their life in concentration camps before the end of the war. These families and other VIP hostages of Heinrich Himmler faced certain death but were saved thanks to the actions of British POWs and imprisoned Wehrmacht officer Bogislaw von Bonin 1945-wehrmacht-officers-who-made-a-stand-against. While the treatment in concentration camps of the Sippenhaft prisoners varied, the harsh experiences of Fey von Hassel (daughter of Ulrich von Hassel) is also described in David Stafford’s book Endgame.

youtube

Rommel (2011) - A German film (with English subtitles available). This movie focuses on the motives for Rommel’s involvement within the resistance, his chief of staff Hans Speidel, key conspirators who would be involved in the seize of Paris from the Nazis and the wavering loyalty of Fieldmarshall von Kluge.

youtube

Those connected with the military Resistance -

The Desert Fox by Samual W Mitchem (2017) - A biography of the life of Erwin Rommel, the Fieldmarshall who on one hand had at first held personal loyalty to Hitler for restoring the army and who used Nazi propaganda to promote his image, but on the other hand was somewhat politically naive and isolated from the aristocratic officers corp due to his commoner status. Originally overlooked by the leading figures of the military resistance, Rommel would eventually become sympathetic to their cause after his faith in Hitler had been thoroughly eroded and his loyalty replaced with hatred. His involvement would come to an end when he was seriously injured after his car was strafed just three days before the July coup.

Guderian, Panzer General by Kenneth Macksey (2017) - A revised edition of the biography of General Heinz Guderian. Guderian was the Wehrmacht’s last surviving Chief of the General staff and a man who often disagreed with decisions made by Hitler as Commander in Chief of the Wehrmacht. Although connected to the resistance and kept well informed of their intentions he was conflicted with their goals and ultimately chose to remain on the sidelines. He was a man who could have suffered a fate similar to Rommel’s had his implication with the plot been proven. Guderian survived the war and was taken into US captivity going onto write his well known book Panzer Leader. Panzer General examines how much of his writing is truth given the opportunity it had given him to present himself in a cleaner light and what aspects of his career during the war had been omitted including his more personal connections to the some of those in the military resistance.

Tapping Hitler’s Generals by Sönke Neitzel (2013) - Secret recordings of Wehrmacht generals held in British captivity before the end of WW2 reveal a stark variation in opinions held by the generals towards Hitler, the Nazi regime, Nazi war crimes and the faith in the outcome of the war. The recordings give an insight into opinions on the failed attempt on Hitler’s life, and also provide evidence of Rommel’s involvement. The book includes the assessment of each the officers from British records.

Bonhoeffer Agent of Grace (2000) - A movie which sums up key events in the life of the pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer and his brother in law Hans von Dohnanyi who both worked under Hans Oster in the Abwehr while aiding the German resistance. Here Justus von Dohnanyi (Hans’s grandson) plays the close friend and student of Bonhoeffer, Eberhard Bethge.

youtube

Valkyrie

Come before Winter (2017) - Another movie about the life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer but one which equally focuses on the actions of Sefton Delmer who used the BBC German service to broadcast “Black Propaganda” in an attempt to diminish support for the Nazi party within Germany and encourage resistance. He and his German speaking colleagues often spread false rumours about Nazi officials and German officers. The broadcasts were heard by many in Germany and would inspire Ruprect Gerngross 1945-wehrmacht-officers-who-made-a-stand-against who would lead the rebellion in Munich through the use of radio in 1945.

youtube

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Christian spy inside the SS tried to expose the Holocaust

Kurt Gerstein 1905 - 1945

In July 1945, just a couple of months after the surrender of Germany, the body of a 6’3” man was bent to fit into a coffin too small and buried next to a misspelled grave marker without service. To an observer at the time it may have seemed like a just end for an SS war criminal who helped facilitate the Holocaust, but Kurt Gertstein had been no ordinary SS man. He was in fact a resistance fighter who’s life had taken him down an extremely dark and complex path.

To make things clearer in this man’s story, which often brings up more questions than answers, Kurt Gerstein was NOT someone who had joined the SS and then began a righteous path once they had witnessed Nazi atrocities. Rather he had been an outspoken anti-Nazi from the early 1930’s and who, in an effort to expose them for who they were, took the unique path of getting as close to the heart of their criminal matters as he could in order to report them to those who he thought could help, tragically condemning himself in the process.

—

Gerstein’s upbringing was unusual for that of a younger resister as his moral beliefs did not stem from his family. He grew up in Westphalia in an upper middle-class, right-wing, nationalist household with a father (a judge) cold and strict and who boasted of his pure Aryan bloodline.

By rights Kurt should have grown into an ideal Nazi follower but the distance of his parents, who didn’t show much interest in his life, had allowed for him to grow up as a rebellious child of independent thinking and he constantly looked for ways in which he could strike out against authority, earning him the reputation of a “Black Sheep” among his family.

At school he was extremely bright but frequently challenged his teachers often resulting in punishment. He had a curious mind where he desired to know everything, barely allowing for time to eat or sleep while he read every book.

While studying engineering at university, he discovered a deep passion for the Christian faith, something which had not been installed within him by his parents, and for him it became an escape. He quickly became a well known youth leader among Christian circles and he often ran youth camps and bible study groups although at the time he never committed himself to a particular church as he saw priests and pastors as another form of authority he did not want to submit to. He encouraged the children to connect with religion in a spiritual sense while teaching them to not be afraid to speak out or ask questions.

The young man became known as someone who helped others and who others turned to for help. He detested false piety and believed it wasn’t enough to simply read the bible but to live by it. He used a third of his income to support the impoverished children within his group and on facilities for his youth camps.

Gerstein’s opposition to Nazism would begin with concern for the future of his youth groups. Growing up in a family with nationalist values, and who were heavily weighed down by the Treaty of Versailles, Kurt did not reject the Nazi party outright as some of his close friends had done and he acknowledged Hitler’s plans to improve the economy and infrastructure of Germany. Being of a curious mind he told one friend that he thought it was hard to judge the Nazis from the outside without first hand knowledge of who they were. Thus in 1933, he became a party member in the hope they would become everything they claimed to be.

His hopes for the party did not last long though and he became angry at the way he could see the Hitler Youth was moulding children physically and politically, likening it to a Spartan upbringing. Gerstein encouraged the youth who were still within his bible groups to fight back but in December of the same year it was decreed that all Christian youth groups were to be merged with the Hitler Youth.

Kurt was among a small number to have protested about this, writing to the head of the Hitler Youth, Baldur von Schirach, in complaint. He also paid for tens of thousands of pamphlets to be sent to Christian youth leaders around Germany and to his former youth group members who had since joined the Hitler Youth. The pamphlets outlined his growing concerns about the Nazi party, which had deepened since he had now seen how they had dealt with their opponents. Encouraged by Gerstein, handfulls of the once hundreds of children continued to meet in secret.

Gerstein would soon grow bolder in his protests. He strongly opposed the Nazi reformation of the Protestant church which he likened to Paganism and supported those who had stood against it, the founders of the Confessing Church. In 1935 he had attended a local play at Hagen which mocked Christianity, Wittekind. It has been put on by the Propaganda Ministry and the entire town had come to watch in a show of obedience whether willing or they felt obliged to. It wasn’t long before Kurt had shouted from the audience that he would not stand to see his religion insulted and it landed him in a fight with local uniformed Nazi members where his teeth were knocked out.

His pamphleting eventually drew the attention of the Gestapo and he lost his job as a mining engineer. His home was placed under surveillance and he was banned from public speaking.

In 1938 he was falsely implicated with a pro-monarchist plot to overthrow the government. The plot never got off the ground but Kurt was sent to a concentration camp by way of association of those involved. He was released within a short while but witnessing the suffering of those in the camp would have a lasting impact on him.

He briefly left the country for his honeymoon later that year and wrote letters to friends and family members in France and the US, telling them everything he could not send them in a letter from Germany, mentioning he was worried for the country’s future and, at the time, had been thinking of escaping if he was able to. He had been forbidden from speaking about his time in the concentration camp but in his letters he would tell his friends about it and he even spoke of it to foreign travellers he met.

He was however now out of money and in trying to return to a form of stability for his family he was about to start, he sought reinstatement of his party membership with the help of his pro-Nazi father (whom he continued to have a distant relationship with since the man was completely unaware of Kurt’s true self), in order to resume his work within the mining industry (a reserved occupation, but also a position he couldn’t obtain without party membership). His job was reinstated although his resistance activities would remain on his record. Despite an outward display of conformity he continued to be spied on and bullied by local Nazis.

In 1940 rumours had began spreading about the sudden death of people in state institutions. This was the beginning of the Aktion T4 program which sought to euthanise the physically and mentally disabled using carbon monoxide gas. The program had been kept from the public but when relatives began receiving death certificates of family members who were known to be in good health, the secret became open and letters written at that time show there was outrage among many as they felt they were now being deceived by the Nazi party.

Gerstein heard of the deaths through the local churches of whom he was connected with through his former youth groups. Troubled at the news, it was at this point he told his friends whom he was able to confide in that he desired get inside knowledge of what was going on inside the Party. In early 1941 the sister of his brother’s wife, Bertha, who had been temporarily living in an institution but in perfect health suddenly died. Her family quietly accepted the official cause of death but Kurt refused to believe it, certain she had somehow been murdered.

He was now convinced that if more people knew what was going on inside the Nazi party they would rise up against them. Some months before he had been rejected for service by the Wehrmacht but he now put in an application for the Waffen SS, horrifying his friends but he told them, “The only course is to join them, to find out what their plans are and to modify them wherever possible. A person within the movement may be able to sidetrack orders or interpret them in his own way. That is why I have got to do what I’ve decided. I want to know who gives the orders and who carries them out: who sends people to the concentration camps, who maltreats them and who kills them. I want to know them all. And when the end comes I want to be among those who will testify against them.”

Since Gerstein’s father thought his application to be genuine it is possible that he used his influence to secure a place for Kurt within in the SS although the true reason of how he got in remains remains unknown and the record of his anti-Nazi activities went undiscovered for some time.

Despite being fairly athletic for a man in his mid 30’s he made a poor recruit. His uniform never seemed to fit him properly and he never mastered goose-stepping. Like as he has been in school, Gerstein struggled with accepting the authority of his superiors and he would come to realise that the way to move forward with his plan was to get on friendly terms with them using bribery at first and later lending a sympathetic ear despite recognising that many of the people he came in contact with held views vastly different from his own.

His talents in engineering were soon recognised and he was posted to the Institute of Hygiene in Berlin while his wife and children remained in their new home in Tübingen, determined to keep his family at a distance to protect them. In his first year in 1941, his department focused on water filtration to provide clean drinking water for soldiers on the eastern front and tackling the outbreaks of typhus by decontaminating weapons and uniforms. Kurt would perfect the methods used to combat these issues and he became known as a leading expert in this field.

During this time he remained in contact with his friends where he assured them he was still the same person he had always been underneath his uniform. He visited a Dutch friend connected with his country’s resistance whom he told that he believed it would be best for Germany to be defeated in order to save the country from losing its soul. The friend gave him one of the books banned in Germany which exposed Hitler’s prejudices and true aims. Kurt smuggled it back into the country hiding it within SS documents he was carrying.

His work soon took him to many places including Oranienburg concentration camp which was close to the Institute and it was alleged that Gerstein bribed the guards with vast quantities of spirits to smuggle food, paid for by himself, into the camp which he had ordered to be sent there in crates stamped with Waffen SS. In his testimony he would say he also met with resistance contacts at the Louis XIV restaurant in Paris, a common meeting spot for resisters and spies.

In early 1942 Gerstein came across a document at the Institute mentioning the gassing of Jews which greatly alarmed him but it did not specify any location or exact method. He made inspections to concentration camps within Germany to try and find out more information but he found none in these places. Unknown to him to the fate of the European Jews had been decided just weeks earlier at the Wannsee Conference attended by Reinhard Heydrich and Adolf Eichmann.

The substance Gerstein used in his decontamination method was Prussic Acid. It was a very effective substance which could completely sterilise the contents of a confined space. In June 1942 he was asked to order a highly toxic variant of Prussic Acid known as Zyklon B which had been patented by the company Degesch. In August when the consignment was ready he was told it was to be delivered to a location only known to the driver of the vehicle and Kurt was to travel with it.

Gerstein made enquiries at the Degesch factory where he sought clarification from workers that the substance was deadly to humans. Concerned, but still not certain as to where he was going, he ordered the vehicle to stop where he said he could smell a leakage of the gas and ordered a single canister to be disposed of. Since Kurt was considered an expert, this action was not questioned and it would serve as a test for later sabotage.

Gerstein was driven to Lubin in Poland where a meeting was held by Odilo Globocnik, referred to as Globus. The meeting revealed the plans of Operation Reinhard of which Globus was to oversee and he personally warned that all present were sworn to secrecy on pain of death adding that two men had been shot for talking the day prior.

There, Gerstein would learn that Jews were being exterminated in carbon monoxide gas chambers in a method which was considered by the Nazis to be too inefficient and they wished to rectify the issue with the use of Zyklon B. Where he had met his fair share of “extraordinary characters”, his words, at the Institute, he now found himself among men who were discussing killing people like it was a routine decontamination.

The group were then taken to Belzec concentration camp where Gerstein saw the operation of the gas chambers. He noted that every detail at the camp had been set up to appear normal to outsiders; the railway station had timetables to look like it was in public use and there were flowers outside the administration offices. The gas chambers were hidden behind large conifer trees. All this juxtaposed the brutal treatment of the arriving prisoners by the German officers and Ukrainian staff who herded them through the camp using whips.

In his report, Gerstein would give a somber and empathetic account of witnessing the prisoners entering the gas chamber and his feeling of horror at not just the event itself but the banality of the process and the belief of the officers that they were somehow working towards a greater good. In that moment Kurt wished he could die alongside the prisoners but realised that would amount to nothing and that he had to somehow report what he had seen.

When the commandant Christian Wirth made a comment that he thought carbon monoxide was still the best method to use Gerstein used the opportunity to say that the consignment of Zyklon B he had brought with him was now contaminated and needed to disposed of.

Still shaken by what he had seen, he took a train back to Berlin. In the corridor he saw the secretary to the Swedish legation, Göran von Otter. He told Otter what he had seen in the camp and produced his invoice for the Zyklon B telling him he needed to tell his ambassador immediately.

Gerstein was convinced that the allies were the key to stopping the Holocaust and he said if they would stop dropping bombs and instead drop millions of leaflets exposing what was going on then there may be an uprising against the Nazis. He would also make contact with the press attaché of the Swiss legation and his friend in the Dutch resistance in the hope their countries could make contact with the allies. He would later learn that while his contacts had been keen to help, not one of their countries had taken him seriously, dismissing his seemingly unrealistic claim of thousands of Jews being killed each day .

In Germany he only confided in those he could trust since he was risking his and his family’s life in telling state secrets. He told his close friends in the local churches including the Confessing Church but he knew he had to reach out to a larger authority in order to get the message to millions of people.

Since a large percentage of Germany was Catholic he went to the Papal Nuncio, the representative of the Pope in Germany in the hope of notifying the Pope, Pius XII. The Italian pro-fascist Nuncio, Cesare Orsenigo was not interested in what Gerstein had to say and turned him away.

Many Catholic priests had been imprisoned by the Nazis and it was the Catholic bishop Clemens von Galen who had spoken out against the Aktion T4 program so Kurt persisted with this channel. Through another contact, Dr Winters, the Pope was eventually informed and he made a speech at Christmas that year where he mentioned, “persons condemned to death solely for reasons of nationality or race.” Not once did the Pope mention the word Jews or gas chambers.

Growing desperate, Gerstein would even tell his contact at Degesch, Gerhard Peters that the company’s product was being used in mass murder. The man appeared concerned but would not put up any form of resistance against orders given. All the company would agree to on Kurt’s request was to modify the Zyklon B to remove the irritants in order to at least make the deaths less painful. The irritant had also served a purpose to detect leakage of the containers and by removing it Kurt’s judgement had to be solely relied upon to detect leaks which he claimed he was able to use for future sabotage. Kurt finally tried to withhold payment to the company in the hope they would refuse further production and this finally saw him removed from his position. While a relief for Gerstein, the Zyklon B production eventually continued.

By 1944 the Nazis were hiding the evidence of the gas chambers and senior officers at the death camps in Poland who had knowledge of Operation Reinhard were reassigned to anti-partisan units where many were killed in action. Kurt became extremely paranoid and would spend the rest of the war expecting a call to report to somewhere to die fighting or to take his cyanide capsule given to him by the SS. His hair at this point had turned white and he was suffering with low blood sugar. He had had suicidal thoughts since his first discovery of the gas chambers but he held onto life in the hope he would see the Nazis charged.

Letters written by Gerstein indicate as well as the Confessing Church he was also connected to the resistance group, the Kreisau Circle led by von Moltke, although Kurt was not involved in the 20th July plot. His own beliefs by that point were that Hitler could only be defeated by the allies and that assassination was too good for what he deserved. It was alleged that Gerstein had used his contacts to smuggle food and cigarettes to the conspirators inprisoned at Plötenzee before their deaths.

In early 1945 he escaped Berlin taking his invoices with him and surrendered to the French near his home in the Baden-Württemberg region. Eventually imprisoned at Cherche-Midi in Paris Kurt finally began what his life had been leading up to and he wrote a report in great detail of his account of the death camps and gas chambers while expressing great sympathy for the victims. He listed the names of those who had been involved in the planning of Operation Reinhard and also gave his backstory as well as the names of those in the Confessing Church, the foreign legations and Dutch resistance he had contacted.

Possible confusion on the part of his French interrogators led them to believe that Gerstein had been personally involved with the invention of the gas chambers and he later received notification of the charges against him which listed him among the major war criminals in the same category as Odilo Globocnik, the people he had wished to see brought to justice. None of his references were at the time contactable and ultimately his interrogators had come to the conclusion that he had sold out his SS colleagues in order to save himself.

The reaction from the French may be understandable given that many of the suspected SS criminals in custody were denying any allegations against them and they took Gerstein’s words to be a confession. The details of his interrogation and report where he proclaimed his innocence were mocked in the French newspapers and on the radio. Kurt was left devastated by this news.

His final days were of misery as the lice and fleas in his isolated cell feasted on his skin and his body couldn’t get enough sugar. On 25th July 1945 he was found hanged in his cell with suicide as the believed cause of death although it couldn’t be ruled out that he was murdered by other German prisoners since his report had been made public.

There was initially little to no sympathy for the death of Gerstein in prison. He was too tall for a municipal coffin and his body had to be forced to fit into it. He was at first buried with a misspelled grave marker but later his bones were later dug up and scattered elsewhere.

During this time the Swedish secretary von Otter was trying to contact London to vouch for Gerstein but his letter was received days after his suicide. The man never forgot the day the two had met on the train and how Kurt had expressed his horror at having returned from Belzec. He would live to regret not having sent his letter in Kurt’s defence earlier.

All was not completely in vain as Gerstein’s report was brought to light during the Nuremberg Trials and would be used in four separate cases and later the Doctors Trial which saw Kurt’s superior at the Institute of Hygiene, Dr Joachim Mrugowsky, sentenced to death and then the Industrialist Trials where Degesch and Gerhard Peters were proven to have knowledge of the intended use of Zyklon B.

In the years after the war Gerstein’s wife was denied a widow’s pension. A denazification court took a harsh view even with von Otters testimony taken into account as they could not separate Kurt’s anti-Nazi stance from his involvement with the Holocaust. The court said that once he had learned of the gas chambers and he realised that there was little that one person could do to help, he should have made all efforts to abandon his duty. Elfriede Gerstein would continue to apply to for a pension to support her three children and eventually succeeded after 15 years on the grounds that that Gerstein had been persecuted by the Nazis in the 1930’s, had been removed from his job and had also been held in a concentration camp during this period.

Today Gerstein is remembered for all that he did during the Nazi-era, the good and the bad, and his character is often the subject of debate. Many have concluded that he cannot be solely to blame for his role in the Holocaust since it was the silence and conformity of hundreds of thousands that fuelled the Nazi machine which he was not able to fight or escape from.

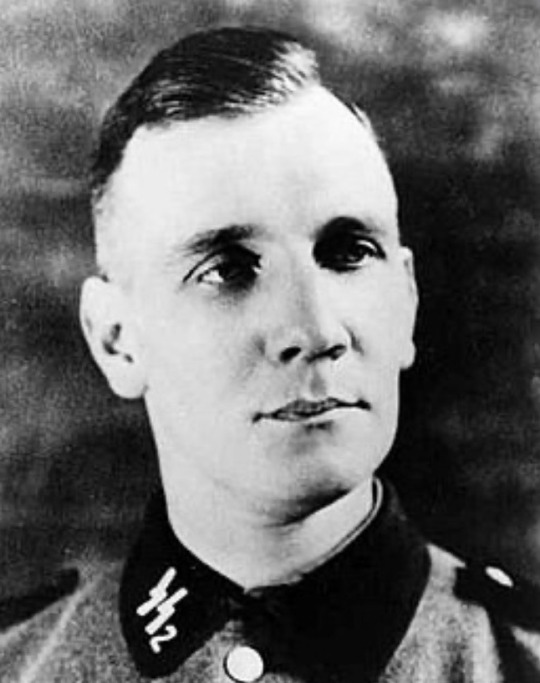

Kurt Gerstein in uniform with the collar tabs of the SS Germania division.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sergeant who risked everything to aid the Jewish resistance.

Anton Schmid 1900 - 1942

While not as well known as the fate which awaited those bound for the death camps, the Holocaust in Lithuania, largely perpetrated by the Einsatzgruppen, German police units and willing Lithuanian collaborators, bore witness to some of history’s most savage acts of barbarianism.

Still, in the midst of the chaos there were a few individuals among the invading forces acting out of humanity to preserve lives; The previously mentioned Karl Plagge, Oskar Schönbrunner and Alfons von Deschwanden were among those stationed in Lithuania who have been formally recognised for their efforts to save Jews from the mass slaughter which was happening around them.

Another man, Anton Schmid, is remembered in particular for the great risks he took to save others which eventually cost him his own life.

Like Plagge, Schmid was an older conscript assigned to a position behind the front line on the Eastern Front. In his hometown of Vienna, Austria, he had opposed antisemitism prior to the 1938 Annexation and he had physically fought against a man in the street who he had caught smashing the windows of a Jewish owned shop. When the Nuremberg laws became applicable to Austrian citizens he had helped his Jewish friends by aiding them to travel to Czechoslovakia where the German anti-Jewish laws at that time were not yet in force.

Upon his arrival in Vilnius in September 1941 he was assigned reaponsibility of a Versprengten Sammelstelle, an office which oversaw the return or re-assignment of soldiers who had been separated from their units. Some of the men he would encounter were suffering with shell shock and didn’t want to return to the front lines, Schmid was able to help a few of them by reassigning them roles within his department.

In addition to his office he also held responsibility for an upholstery and shoe-repair workshop to serve the Wehrmacht and employed a number of Jews who carried certificates to prove they were essential workers.

Schmid had heard that those without certificates were being taken from the ghetto to be shot and like Plagge and Schönbrunner, in an effort to preserve lives, he too used his authority to increase his number of workers far beyond the actual amount required, employing a total of around 150 people which came to include Russian prisoners of war.

Survivors would later recall that Schmid did his best to provide extra food in addition to the starvation rations, not just for his workers but for their families also.

Although he was only a sergeant, Schmid was allowed to operate without too much supervision from his superiors and since the Wehrmacht was keen to use all resources available to assist with its war effort, including using Jewish civilians for labour, it was possible for his initial actions alone to have passed under the radar but within a short amount of time his resistance efforts would steeply increase.

A Jewish man, Max Salinger, who had traveled from Poland and was not registered in the Vilnius ghetto, came to his workshop and asked him for a job. Unable to issue the man with a work permit like he had done with the others, Schmid gave Salinger a uniform of an enlisted soldier and employed him as a typist in his office.

Part of Schmid’s role was to notify the units of soldiers who turned up in the hospital and he was able to find a corporal there who had died earlier that day with the same first name of Salinger and gave him his papers to assume his identity. To cover his actions, Schmid would falsely report that the soldier had recovered and had been reassigned to his office.

Just days after this event a young woman, Luisa Emaitisaite, approached Schmid for assistance after she had missed the evening curfew in returning to the ghetto. It was unclear whether she had realised in the dark that he was a Wehrmacht soldier but Schmid would shelter her in the spare room of his own accommodation.

Wanting to do more for her he sought the help of a local Catholic priest whose church he had regularly gone to for confession since his arrival in Vilnius. Schmid got on well with the priest since the man had also previously lived in Vienna and they often talked together. He asked the priest if he could issue her with a document which identified her as Catholic and the man agreed to help saying that he could justify the fraud to God since he was saving a life.

The document was typed on official paper of the church and once the German and Lithuanian administration was convinced Emaitisaite was a catholic, Schmid was able to employ her in his office as a typist like Salinger and she was able to live within the city as a regular citizen. Schmid and the priest went on to help more Jews using the same method and he soon had several people hidden in his apartment he was trying to arrange papers for.

Meanwhile, a resistance group had formed within the ghetto and once they had heard that Schmid could be trusted a couple among them approached him for help and Schmid held a meeting in his accommodation with Salinger, in his corporal’s uniform, guarding the door.

The couple asked if Schmid was willing to assist with smuggling Jews from Vilnius to Bialystock in Poland with the aim of joining larger resistance groups from there. Schmid agreed to help and would accompany a small group in a Wehrmacht truck to Bialystock, arranging a signal with Salinger where he would telephone the office from his destination to let him know he had been successful.

This action was repeated several times over the next few weeks and Schmid and the resistance group were able to smuggle 350 Jews out of Lithuania. Some resistance members would later recall that they considered Schmid to have been a friend although they remembered that he had become extremely worn down by his double life and had taken to heavy drinking. When asked if he feared being discovered he replied, “We all must die. But if I can choose whether to die as a murderer or a helper, I choose death as a helper.”

Mordechai Tenenbaum, a member of the resistance, told Schmid he would make sure his name would be remembered after the war. Later Tenenbaum would take part in the Bialystock ghetto uprising where he would be killed.

In January 1942, just a few short months after arriving in Vilnius, Schmid was arrested by the secret field police (GFP) while escorting Jews into neighbouring Belarus and he was imprisoned. When Salinger hadn’t received Schmid’s usual telephone call, the man was able to give warning to the resistance members to stay away from Schmid’s office. With their papers now identifying them as non-Jews, Max Salinger and Luisa Emaitisaite were able to flee the area and both would later survive the war.

Due to many records having been destroyed only fragments of the details of Schmid’s trial remain. The transcript of the trial is missing so it not known exactly what he was charged with, although what is known is that Schmid objected to his own defence when the lawyer provided wanted to claim that he had only acted in the interests of the Wehrmacht in protecting valuable workers from liquidation. Schmid had said that this wasn’t true and that he had acted out of humanitarian reasons as he disagreed with the Nazi’s treatment of the Jews. He was therefore admitting to violating orders given to army personnel to treat Jews as the enemy regardless of sex or age.

In April 1942 Schmid was executed by a firing squad along with a group of soldiers who were charged with cowardice. Shortly beforehand he had written to his wife in prison telling her about everything which had happened since his arrival in Vilnius including the atrocities he had heard about and how he was soon to be shot for his intervention. He would write to her, “I only acted as a human being and didn’t want to do harm to anyone.”

It is not known exactly how many of those that Schmid helped eventualy survived the war but his name was mentioned in several diaries left behind in the Vilnius ghetto.

At the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, Schmid’s name was mentioned by survivor Abba Kovner where he said Schmid had told him shortly before his arrest that he had heard rumours of a man called Eichmann who was said to be one of most senior SS men organising the mass murder of the Jews.

The mention of Schmid’s name at the trial prompted interest in his story. Max Salinger who was then living in Israel, told Simon Wiesenthal that Schmid’s widow Stefanie had faced scorn and violence in the immediate years after her husband’s death and that he had given her some money after the war since she had been denied a war widow’s pension.

Wiesenthal would personally visit Stefanie in Vienna and he helped her to travel to Israel where Schmid was honoured as one of the first Germans to be recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

The tree planted for Anton Schmid on the Avenue of the Righteous in Israel.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Truth & Treason

youtube

Trailer for the upcoming movie Truth & Treason about the brave actions of Helmuth Hübener and his friends mentioned in my earlier post two-young-german-resistance-fighters.

He was the youngest German to have been tried by the People’s Court for resistance activities and was executed by guillotene in Plötzensee prison at just 16 years old.

I‘m really looking forward to watching this and seeing how his life is portrayed even I though I have a preference for Germans to be portrayed by actual Germans if possible.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

One officer’s attempt to save 1200 Jews was almost lost to history

Karl Plagge 1897 - 1957

The deeds of Karl Plagge, a man who is now thought of by some as the “forgotten Oskar Schindler”, were only brought to public attention when the son of a Polish Holocaust survivor, Michael Good, began to look for information on a Wehrmacht officer his mother and grandfather had always credited their survival to.

Although decades after Plagge’s death, through extensive research into his actions during the war, writing to and meeting with other Holocaust survivors, obtaining his Wehrmacht files and reading the transcript of his post war trial, Good was able to put together a picture of the man Karl Plagge had been and his motives for wanting to help Jews.

—

Plagge had served as a young officer in WW1 and during time spent as a POW in the UK he acquired polio through infection leaving him partially disabled and he left the army. He went on to study chemical engineering but struggled with unemployment and financial problems in 1920’s.

He joined the Nazi party in the early 1930’s as he believed it could help grow the economy in Germany but quickly grew to dislike the party when seeing the way they had dealt with their opponents when coming to power.

Through his party membership he was appointed a job teaching science in a Nazi institute but he refused to teach their views on racial theory or wear the required Nazi uniform which led to him being dismissed and he would stop paying his membership fees. He also fell under suspicion of local party members for not distancing himself from his Jewish friends. Although it was never discovered, he had also chosen to become godfather to a half-Jewish child, the son of a close friend, undertaking a sizeable risk in 1938.

By the time of his conscription into the Wehrmacht, Plagge held strong anti-Nazi views. Due to not being able to serve as a frontline solidier he was assigned to a Heeres Kraftfahr Park (HKP), a Wehrmacht car pool based in Germany where he was tasked with overseeing the repair of army vehicles. In June 1941 he was promoted to Major and transferred to another HKP unit in Vilnius, a city in previously Polish territory but since declared part of Lithuania. This unit would be known as HKP 562.

Just days after the German occupation of the city, the Einsatzgruppen and antisemitic Lithuanian collaborators rounded up and killed thousands of the Jewish population in the Forrest of Ponary leaving just a small number in a ghetto in Vilnius. Plagge saw the evidence of this upon his arrival and was shocked.

Wehrmacht officers had written to SS commanders saying they disapproved of the mass killings, mainly because they needed labour to support the army but some on moral grounds. It was then agreed the Wehrmacht could use the remaining skilled workers within the ghetto although the SS would still hold the ultimate authority. It was through this action that Plagge was able to do something to help.

Skilled Jewish workers were given a work permit which protected them and their families, while those without a permit faced deportation to concentration camps or death. Plagge used this opportunity to issue as many permits as he could to employee the civilians of the ghetto in his workshop, Good’s Grandfather among them.

Of the people he had issued permits to, many were actually unskilled and had no prior knowledge of vehicle repair. Plagge had known of this and to cover his actions his men worked alongside the Jewish workers to give them training.

Plagge told his staff at the workshop that he would not tolerate violence towards Jewish or Polish workers and did his best to transfer to the frontline those in his unit who were reported to have broken this rule or anyone who held strong national socialist views.

At first his workers would remain living within the ghetto, but in order to protect them and their families from further liquidations Plagge battled with the SS via letters and visits to their HQ to insist his workers would be more productive if families were kept together and eventually they allowed him to acquire two large apartment buildings just outside of the city and he moved his workshop there. With word of an upcoming liquidation Plagge ordered his men to drive to the ghetto and take with them as many civilians as possible rescuing hundreds more than the original number of workers.

As there were so many people, in order to prove to the SS that everyone was of use to the Wehrmacht he set up further enterprises to enable everyone to be employed which included making furniture, the rearing of rabbits for gloves and hats, the repair of German uniforms and also shoe making. A total of 1250 Jewish civilians as well as several Polish families would move into the new HKP 562 complex.

Although HPK 562 was a labour camp with a surrounding barbed wire fence, Plagge did his best to ensure conditions were as good as he could make them within his authority. In the living accommodation there were cooking and cleaning facilities and even though more than one family had to share a room there were beds to sleep on. He also made sure that there was a doctor among his workers and he later set up a small hospital.

Postwar photo of the HKP 562 accommodation

Plagge knew the starvation rations issued by the German administration were certainly not enough so he instructed his men to acquire what food they could and was able to provide his workers with an extra meal per day with the remaining food items being sold in the camp on the black market. Since it had been made illegal for both the military and civilians to assist Jews, this black market was necessary as it diverted the intention of Plagge to feed the workers away from the army as they were the ones profiting from it.

Since the soldiers in Plagge’s unit were mechanics also, they maintained a good relationship with the Jews they worked alongside and in many cases actual friendships were formed. From the survivor testimonies Good could only find a few incidences of violence from Plagge’s men and when it had happened there was evidence he had tried to intervene.

On one occasion, when an SS officer threatened two workers with his gun he had caught stealing food, Plagge saw this and dragged the men into the army barracks out of sight and told them to scream as if he was beating them until the SS officer believed they had been punished. What would remain out of his control were the capital punishments the SS would issue to those who were caught outside of the camp trying to escape.

The survivors told Good that Plagge never asked for bribes or favours. Some who had personal contact with him such as the Jewish representative at the camp said it seemed Plagge was actively trying to protect his workers and another said Plagge had told him that he had the authority to grant work permits to all local civilians but he had tried to reserve his permits for Jews as he knew they were at greater risk. They also said that working hours within the camp were reasonable and that they had been permitted a day of rest each week. Plagge had given the children small gifts at Christmas and he had allowed them to put on a play in respect of Purim.

In late March 1944 Plagge took leave to visit his family but he returned to find the camp grieving. While he had been away there had been an order for the SS to deport the 200 children in HKP 562 to a concentration camp. When the soldiers had arrived the children had ran to hide and a small number were later found alive but because they could no longer be seen in the camp their parents had no choice but to conceal them behind walls or under stairs for the entire remaining time they would live there, one of these children would be Good’s mother. Plagge knew there were children hiding in the camp but he never gave anything away.

Parents of those who survived thought it was too risky to tell anyone that their child was still alive and it was a common held belief among these children that they were each the only one to have lived through the what was known as the Kinder Aktion. Good would later discover that around 25 children had survived and through his reuniting of the camp survivors some were finally able see their friends once again.

With the Germans retreating on the Eastern Front, Plagge was informed with little warning that his HKP workshop was to be closed and his Wehrmacht unit was to be moved back within German territory. Realising it was likely that the SS would now liquidate the remaining Jews within the camp, on 1st July 1944 in a final effort to give everyone a chance of survival he made a speech to announce his departure and warned his workers that they were now in the hands of the SS who had already began to arrive to take over control the camp.

Over the next two days the residents began to look for places to hide while the SS guards increased in number. A small number would managed to escape during this time but it wasn’t possible to leave in large numbers due to the increased risk of detection. As predicted, the mass killings began on 3rd July and tragically all but 250 people would survive with the remainder being shot and buried in a mass grave. The survivors would remain in their hiding placing until the city was liberated by the soviets weeks later.

Plagge would never learn how many people had lived or died and his half-Jewish Godson who survived the war said that the man was racked with guilt over not being able to have done more to help and said he was escpecially haunted by the death of the children.

Like all German officers who had ran POW or labour camps, Plagge was investigated for war crimes however a small number of HKP survivors would willingly attend his trial in his defence. Having listened to the testimonies, the court wanted to declare Plagge as innocent but he refused to accept this saying he had to share the guilt of those who had brought the Nazis to power.

In his research, Michael Good would learn that Plagge had written to one of the survivors who had given evidence at his trial, David Greisdorf, enquiring about the man’s family’s wellbeing and arranged to meet with him since his family was now living in a displacement camp in Germany.

From the letters written by Plagge to Greisdorf and kept by the man’s son, another survivor of the children’s Aktion, Good saw that Plagge had expressed much gratitude towards the family’s hospitality and kindness and that the two men had spent hours together talking about the recent years.

In addition to the survivors who had given evidence at the trial, several members of Plagge’s HKP unit had made statements also. Although it wouldn’t be possible for Good to find out much about these men without investigating each one, he found it clear from the transcript of the trial that the men had at least been aware of Plagge’s aims of protecting the Jews within his care. It was also reported that on more than one occasion Plagge had found ways to defend his men who had expressed anti-nazi sentiments and had prevented the accusations from being investigated further.

In a surprise for Good, he discovered that a member of Plagge’s Wehrmacht unit, Alfons von Deschwanden, was still alive and had already been contacted by two of the surviving families years earlier. Deschwanden was only 19 when he was assigned to HPK 562 in 1942 as a mechanic but had been remembered by the survivors as having stood alongside the workers during inspections by the SS and that he had personally hidden a two year old child behind his workbench while their family searched for a better hiding place.

Alfons von Deschwanden

Deschwanden’s father had been outspoken about the Nazis and would be one of the thousands arrested after the July plot but fortunately later released. Deschwanden himself had learned about concentration camps early on since his family had known people imprisoned for political reasons and during his time at HKP 562 almost faced trial himself when an officer reported to Berlin that he let slip a remark about the White Rose movement after he had heard about their deaths while at home on leave.

Despite the warnings from others in his unit he engaged in close friendships with his Jewish colleagues. Since their contact after the war he had received an annual box of oranges from the family of one of the survivors from their new home in Israel.

Good’s family wanted to seek recognition on behalf of Plagge for his actions but needed to prove the personal risk the man had taken. Good looked into the circumstances as to what challenges he may have faced in his position. The orders given to German officers within the Vilnius area were as follows, “Social communication with Jews as well as any private conversation is most strongly forbidden. Who will associate privately with Jews has to be treated as a Jew.”

These orders matched those by the Wehrmacht personal office to all officers with the added line, “Whoever violates this intransigent bearing, is not acceptable as officer.” Good discovered that another officer based in Vilnius, had been executed for assisting Jews in a similar way to Plagge, the Austrian Anton Schmid and a man as equal deserving in respect as Karl Plagge. Good deduced that Plagge had taken several risks but went to great lengths to make it appear as if he was playing within the rules, realising that there was always the chance of his plan collapsing if he stuck his neck out too far.

In 2004 Yad Vashem honoured Plagge with the title of Righteous Among the Nations with Good’s family, Plagge’s Godson and many survivors who remembered him in attendance at the ceremony in Israel. There was also a ceremony in Plagge’s hometown of Darmstadt and Alfons von Deschwanden attended with his family.

From a personal point of view it must said that the journal of Good’s path to finding the answers he was looking for is extremely enlightening and delves deep into the decisions faced by soldiers and civilians during the Holocaust, both the good and the bad. The story goes beyond what I have written here and a must read for anyone with an interest in the Holocaust. The efforts put in by Michael Good and the survivors to honour Karl Plagge, often reliving painful memories, can hardly be put into words. I can’t recommend his book The Search for Major Plagge enough.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Krebs and Burgdorf - Last seen alive around midnight on 1st May 1945

The Krebsdorf shipper within me means I sometimes find myself getting sentimental over the death of these two, in the sense of the parodied characters the fandom has created that is.

On a serious note I do think about the real life Burgdorf way more often than what is healthy. I read in one book that he kept a diary which is probably long since lost but I think it would be very interesting to read. He may not have been famous as some of the other generals but he had an impact on so many in the final year of the war and not for the better.

I would like to know the inner thoughts of the man who in the last years of his life hit the self destruct button (and the booze) pretty hard. A man who abandoned his loyalty to almost the entire officers corps to prove himself to Hitler’s inner circle, the same circle who he would feel completely isolated from in his final weeks and cause him to bitterly regret his choices.

What was going through his mind as he watched Rommel die, when he handed over the 20th July conspirators to the Gestapo and when he weeded out disloyal officers by sending them to frontlines where there was little chance of survival?

Like the tens of thousands who died in Berlin because of the stubbornness of him and others he even condemned his best friend to die when he recommended him for the job no one was lining up for. From a distance it seems that anyone who came into contact with Burgdorf was doomed.

As one of the most fanatical Nazis among the Wehrmacht he was reported to have had an almost childlike belief in the final victory until the last moment but I often think did he have that much faith in Krebs that the man could turn things around for Germany or could hold out indefinitely?

I could be wrong but I think that a man who had isolated himself from the world that much, probably wanted to have his best friend beside him, in what even he must have known were the final days, so he didn’t have to be alone.

0 notes

Text

WW2 German Artefacts passed on by POWs 1945-1946

As @cursedreverie1945 was interested, below is a small collection of pins given to my grandad by German POWs in 1945-46.

List of pins

EBoat, Panzer, Party badge, Service pin 1939, Red Cross and Radio Operator/Air Gunner/Mechanic

My grandad was a sergeant in the RAF and had joined at a young age in 1938 before the war broke out. He was a mechanic and driver and served in 500 Squadren based in Kent.

After the war ended in Europe he was assigned with picking up Wehrmacht personnel in his truck and delivering them to where they would be transported to larger camps. The prisoners were mainly Luftwaffe but occasionally from the other services also.

He was a man who enjoyed talking and would often try to engage in conversation with the prisoners to put them at ease and to ensure the transfers went smoothly. He remembered there was generally respect between the Luftwaffe and RAF men and he particularly liked taking to his counterparts, the drivers and mechanics on the other side. It seemed to him that everyone including his own men wanted to go home.

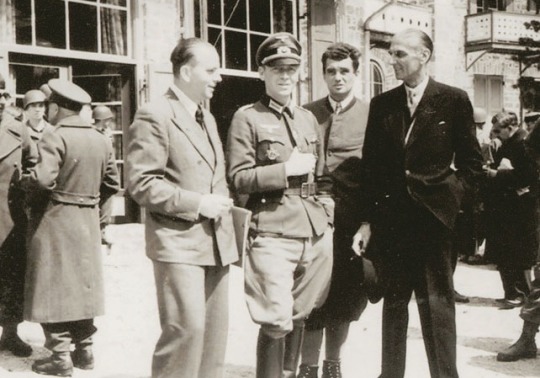

The photographs below are of my grandad (with the mustache) and Luftwaffe prisoners. He is only in his mid 20’s here but he looks much older.

As well as in the previously occupied countries, the RAF played a large role in providing humanitarian aid to Germany and Austria immediately after the war and my grandad was a part of this also. He eventually left the RAF in late 1946 having finished his service based in Innsbruck (inside the British Zone of Austria).

Between the end of the war and this time he was passed on a number of military items by German prisoners as allied personnel were looking for keepsakes of the war they had fought in and many prisoners were happy to give them away. Originally he had a much bigger collection including many more photographs but due to living in government housing for many years and often moving, only a few items sadly remain.

The pins now all show signs of age but the radio operator pin still has the box and is in very good condition. The initials on the back of the pin say CE. Junker Berlin. It was a common pin at the time but is now sought after among collectors.

He was also given an Ehren Chronik (Honour Cronical), a book presented to milititay personal so they they could record details of their service in war. It is a fascinating book containing many propaganda statements and photos of Hitler and the heads of the Wehrmacht. It also has a section where the owner could list their Aryan heritage going back several generations.

This particular book does not contain any personal information or photographs and the generic contents can be found online however if anyone would like me to post more of what is inside, I will.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isa Vermehren, Werner Finck and the 1930’s Berlin Cabaret

Isa with her accordion Agathe

The Berlin cabaret scene, known for its rise to fame in the early 20th century had been heavily represented by performers who were politically left leaning, Jewish or LGBT, many of whom would be imprisoned or would leave Germany once the Nazis rose to power.

By the early 1930’s, only a few of the original venues would remain open where a small number of people would continue the industry, daring to oppose the Nazis social norms and often bringing to light political issues through on stage satire. Isa Vermehren and Werner Finck are among those most remembered.

Isa Vermehren was born to well educated parents with strong anti-Nazi sentiments. Although their own resistance was passive, her parents were both connected and related to conspirators of the 20th July plot.

Isa’s first act of resistance against the Nazis came in 1933 when she was just 15 years old. In support of her best friend at school who was half-Jewish and who had been told that she was not allowed to salute the Nazi flag with the rest of her class, Isa would stand in solidarity with her friend by refusing to salute the flag herself and would promptly be expelled from the school.

Her younger brother Erich would also make a stand by refusing to join the Hitler Youth, an act which would later cause his passport to be revoked and he would lose his chance to study at Oxford University.

Isa would move to Berlin with her family and due to leaving school without a certificate she chose to join the Berlin cabaret, Katakombe, where she first performed under her stage name Hanna Dose.

The Katakombe cabaret began in 1929 and was run by Werner Finck. It was intentionally political with satirical acts designed to mock the Nazi party. From 1933 the cabaret continued but was heavily monitored with Gestapo informants present each evening.

The songs never mentioned the party directly or names of its leadership but the words were enough for the audience to guess who they were singing about and it was enough to upset those in Hitler’s inner circle. Julius Streicher, publisher of Die Stürmer and an early party member would write, “Should it happen again that a cabaret artist makes fun of a political leader, we shall close the shop on him. I shall annihilate any such impertinent prattler. If I again hear reports of people circumventing the rules which the Führer does not want ignored, I shall take them to task and there will be serious consequences.”

Isa’s contribution to the cabaret would be her sea shanties which she sang and played on her accordion Agathe. Although she began at only 16 years old she quickly became a headline act. One of the songs she was most famous for was Eine Seefahrt die ist Lustig (A see journey which is funny), an already known song but with the added verse,

“Our first mate on the bridge, is a guy three cheeses tall, but he has a mouth as big as an anchor sling hole.”

It was clear to all exactly who she was mocking and it did not go down well with the propaganda minister.

Werner Finck himself was known for his extremely quick wit which he often used to both make fun of and defend himself against Nazi agents. One evening he called out from the stage to the Gestapo man in the audience, asking him if he was speaking too fast for him to keep up writing his notes.

The life of the Katakombe cabaret would come to an abrupt end in 1935 with the sudden raid and arrest of many of the performers including Werner but even in arrest he pushed back with humour. When an SS officer asked him if he was carrying any weapons he quipped back, “Why? Should I need one?”

Werner was interned in a concentration camp where he would continue his satirical performances to entertain the prisoners for which he received beatings from the guards. He addressed the audience of prisoners telling them, “What are their bullets compared to our jokes that hit (the Nazis) much harder?” He was later released and would serve in the Wehrmacht until the end of the war.

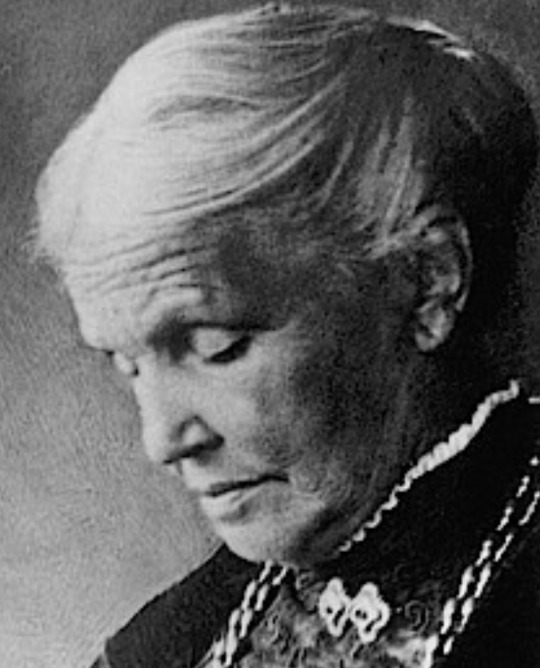

Werner Finck

Fortunately Isa had not been present at the Katakombe that night and managed to avoid arrest. She returned to evening school where she met other students who opposed the Nazis but her life would change drastically as she turned to religion.

In 1938 she converted to Catholicism and took up residence as a student in the home of a religious order. She desired to become a nun but was rejected entry to the convent there due to her previous career on stage. She volunteered with the Red Cross cross and when the war broke out the nuns in the order would serve as nurses on the front and Isa went with them. She would sing for Wehrmacht troops although this time her songs would remain politically neutral.

Her brother Erich meanwhile had married into a family who had already been imprisoned due to the distribution of anti-Nazi leaflets in 1937. He had used his connections to join the Abwehr with the intention of escaping Germany with his wife and in 1944 defected to the British leaving Isa, her parents and her other brother to all be imprisoned under Sippenhaft (the family guilt clause).

Isa was at first sent to Ravensbrück then Buchenwald and finally Dachau where she would become part of the group of special prisoners (VIPs) that Himmler intended to use as leverage to gain more favourable conditions of surrender.

During her time within the camps she was allowed to bring her accordion although the guards would force her to play to entertain them. From her cell where she received better treatment than most, although still poor overall, Isa witnessed the harsh treatment of the women in the camp and saw executions take place. She was able to play to the women but would later remember the physical pain in their weakened voices as they tried to sing along.

Once assigned to the group of VIP prisoners she played to comfort the children who had been imprisoned with their parents under Sippenhaft after the failed July plot.

Due to the intervention of a Wehrmacht unit commanded by Captain Wichard von Alvensleben, the group was rescued from the SS and were later freed by the US Army in the final days of the war. Her parents who survived also, encouraged her to write down her experience and that of the other women in the camps in a book, Reise durch den letzten Akt (Journey through the last act).

Immediately after the war she had to put off returning to her religious studies due to having no money and appeared in a film, In jenen Tagen (In those days) which dealt with the issues of collective guilt of the German people and of those who resisted passively, a matter close to her own heart. She also began teaching as well as studying theology, history, German studies and English.

In 1951 she finally entered a convent while continuing to teach children, eventually becoming the head teacher of a school and would give lectures on faith into her retirement and up until her death in 2009. She would receive the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany for her contribution to education.

Werner Finck survived the war and continued his career in cabaret and satirical writings, often making light of post war politics. He died in 1978.

Isa as a nun in the years before her death

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Woidsteel Freiheitsaktion

youtube

German to English translation of Woidsteel’s amazing song Freiheitsaktion based on the Freedom Action Bavaria resistance group.

The first song I have heard dedicated to a WW2 resistance group within Germany.

—

April fünfundvierzig - April forty five

Die Dämmerung bricht - The twilight breaks

Der Krieg fast vorbei - The war almost over

Doch die Furcht weicht nicht - But the fear does not give way

München in Ketten - Munich in chains

Ein Reich in Zerfall - An empire in decay

Doch ein Mann erhebt sich - But one man rises

Zum letzen Kampf - To the last fight

Geboren in Shanghai - Born in Shanghai

Fern in fremdem Land - In a foreign country

Ein Bayer im Herzen - A Bavarian at heart

Mit eisernen Mut - With iron courage

Für Freiheit und Frieden - For Freedom and peace

Für Heimat und Ehre - For homeland and honor

Er ruft zum Sturm - He calls for the storm

Zur letzen Schlacht - To the last battle

Für Bayern, für Freiheit - For Bavaria, for freedom

In finstern Nacht - In (the) dark night

—

Rupprecht Gerngross - Rupprecht Gerngross

Führt uns in den Kampf - Leads us into the fight

Freiheitsaktion, jetzt ist es soweit - Freedom Action, now is the time

Hoffnung entflammt in der dunkelsten Zeit - Hope ignites in the darkest time

Unser Freistaat lebt - Our free state lives

Die Stadt wird gefreit - The city will be free

—

Mit Waffen zu schwach - With weapons too weak

Doch die Wille so groß - But the will (is) so great

Ein Funke aus Mut - A spark of courage

Gegen Hitler’s Wahn - Against Hitler’s delusion

Die Sender besetzt - The transmission occupied

Die Lüge zerbricht - The lie breaks

Legt die Waffen nieder - Put down your weapons

Ertönt es ins Land - It sounds in the country

Ein Volk erwacht - The people awakes

Die Angst vergeht - The fear passes

Der Tyrann erbebt - The tyrant trembles

Doch es ist zu spät - But it is too late

—

Rupprecht Gerngross - Rupprecht Gerngross

Führt uns in den Kampf - Leads us into the fight

Freiheitsaktion, jetzt ist es soweit - Freedom Action, now is the time

Hoffnung entflammt in der dunkelsten Zeit - Hope ignites in the darkest time

Unser Freistaat lebt - Our free state lives

Die Stadt wird gefreit - The city will be free

—

Doch die Waffen SS - But the Waffen SS

Schlägt blutig zurück - Strikes back with blood

Die Freiheitsbewegung, ein kurzer Blick - The freedom movement, a brief moment

Auf das Ende der Herrschaft - To the end of the rule

So nah und doch fern - So close and yet far

Ein Opfer aus Mut - A victim of courage

Die Welt wird wissen - The world will know

—

Rupprecht Gerngross - Rupprecht Gerngross

Führt uns in den Kampf - Leads us into the fight

Freiheitsaktion, jetzt ist es soweit - Freedom Action, now is the time

Hoffnung entflammt in der dunkelsten Zeit - Hope ignites in the darkest time

Unser Freistaat lebt - Our free state lives

Die Stadt wird gefreit - The city will be free

—

In Shanghai geboren - In Shanghai born

Für Bayern gelebt - Lived for Bavaria

Ein Held unserer Heimat - A hero of our homeland

Vergisst ihn nie - Never forget him

0 notes

Text

90 year old Julie Bonhoeffer stood up to SA Stormtroopers

In Berlin 1933 when Nazis began blockading and encouraging the boycott of her favourite Jewish owned shops Julie would simply brush the line of SA men aside, telling them she had always shopped there and would continue to do so. She was largely protected by her age but she was not afraid of their presence.

Julie was a woman of strong principles and had been outspoken on women’s rights in the early 20th century. She would pass her kindness and her strength to stand up for others on to her son Karl Bonhoeffer and her Grandchildren Dietrich and Klaus Bonhoeffer and their sister Christine von Dohnányi, married to Hans von Dohnányi.

A tight bond existed between her family and extended family and they were among the most active of those who resisted the Nazis within Germany, starting in the early 1930’s, often bridging the gap between the civilian and military resistance groups.

In the final years before her death in 1936 Julie lived with Dietrich who would often refer to her as his inspiration for becoming a pastor and would continue to uphold her belief in treating everyone as equal. He would support her in writing letters of comfort to her Jewish friends.

Dietrich, Klaus and Hans would eventually be arrested and all three were executed in concentration camps just weeks before the end of the war. Christine was arrested also and separated from her children but was later released.

#Julie is also the great great grandmother of Justus von Dohnányi#ww2 germany#ww2#german history#german resistance

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Last Words of Admiral Canaris

80 years ago today, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris head of the Abwehr in Nazi Germany was executed in Flossenbürg concentration camp.

A complex figure among the German resistance, Canaris came to despise Hitler and cried when orders were given to invade Poland. Although not an organisation free from corruption he sought to use his intelligence service to bring down Hitler from within Germany.

Arrested in the wake of the July plot he endured months of torture prior to his death at the hands of the SS. On the 9th April 1945 he would be hanged naked from a meat hook.

In the hours before his execution he was recorded to have tapped on the wall of his cell,

“I die for my country and with a clear conscience. I was only doing my duty to my country when I endeavoured to oppose Hitler and to hinder the senseless crimes by which he has dragged Germany down to ruin. I know that all I did was in vain, for Germany will be completely defeated.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

1945: Wehrmacht officers who made a stand against the SS

Part 2

Freedom Action Bavaria

In April 1945 BBC Journalist Noel Newsome travelled to interview Rupprecht Gerngross the leader of Freiheitsaktion Bayern who had led an uprising in Munich and the surrounding towns during the final days of the war.

His article for The Times newspaper was rejected by the British Foreign Office for the reason that it was “not thought desirable to suggest that there were ‘good Germans’”. Outside of Munich the story went unknown for several decades and many of the details did not come to light until Gerngross’s biography was written in 2018.

I want to include the background to this story as it is as important as the event itself.

—

Rupprecht Gerngross, born in 1915, was the son of a Bavarian Professor based at the German Medical School in Shanghai. His parents gave him a liberal upbringing with respect for the local culture and encouraged him to learn many languages.

When the political situation in Shanghai became tense, Gerngross and his parents moved back to Munich but would discover Germany was facing its own political tension due to the economic crisis. Everywhere people were turning to the Nazi Party and at school several boys had joined the Hitler Youth. As it had not yet become compulsory, Gerngross would choose to join the Boy Scouts instead.

In the early 1930’s the Nazis in Munich held rallies and produced propaganda to divide the population against those they said were destroying Germany. Gerngross’s liberal parents were deeply offended by it all and walked out of an Easter festival where the Nazis has taken over the stage and played the Horst Wessel Lied instead of the national anthem.

His parents formed their own small anti-Nazi group of mixed political views, holding meetings at their home. The group, and Rupprecht, would discuss the truth behind what they read in the, now only available, Nazi newspapers and what was really going on in Dachau. The group was soon discovered and SA men ransacked their home, threatening the family with being classed as Jewish if they did not stop. They had no choice but to end the meetings.

As he reached adulthood, Gerngross’s own political beliefs became more conservative than his parents. He identified as a patriot of his country, opposing the Versailles Treaty while being weary of both Communists and Nazis. He became friends with like minded people whose beliefs were that “It was possible to put your own country first without resorting to the hatred and denigration of others.”

Gerngross at first felt proud to serve his country when he received his call up papers but within months of the start of the war he began hearing rumours of murders committed by the Einsatzgruppen and eventually would see this for himself and later in 1941 the cruel treatment of Jews by his own Wehrmacht commander who when he received a life threatening injury, left him for dead. This moment would be the turning point for Gerngross and when he realised he had to make a stand somehow.

This would be easier said than done as when he returned to Munich, now declared unfit for service, he saw Nazi ideology had become fully engrained in every part of life and it had now become almost impossible to put up any form of resistance. Dachau had expanded and his parents were still under the watch of the Gestapo. Due to their previous resistance activities, they were denied any assistance when their house was bombed.

Gerngross’s opportunity came when he volunteered to DOLKO, the Interpreter company within the Wehrmacht. With his language skills earning him the rank of captain, he used his authority to recruit politically like minded soldiers, eventually reaching 400 men.