#read a book on this history of racism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

some of u guys are defending a billionaire company a bit toooooo hard

#niche genshin drama that was on my feed#they cant just yoink and twist a CULTURE but make them all white#read a book on this history of racism#or colourism#or BOTH#and the harmful role media portrayal plays in perpetuating stereotypes and harmful ideals#soooooooo many L takes#some of u guys are LOSERS#and also billionaire company will never do anything for u no matter how much money u spend or how much u defend them online#natlan#hoyoverse

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

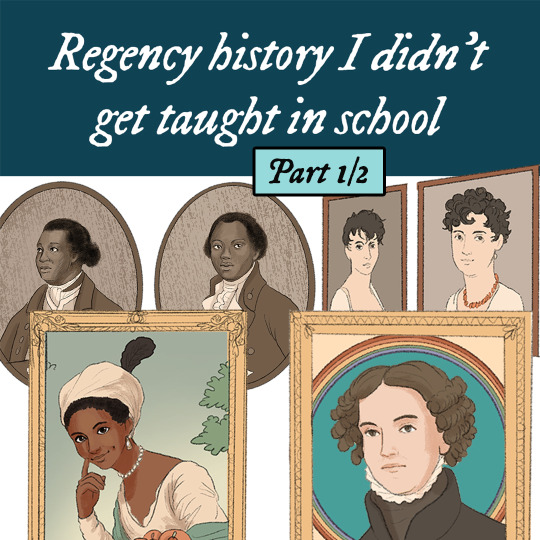

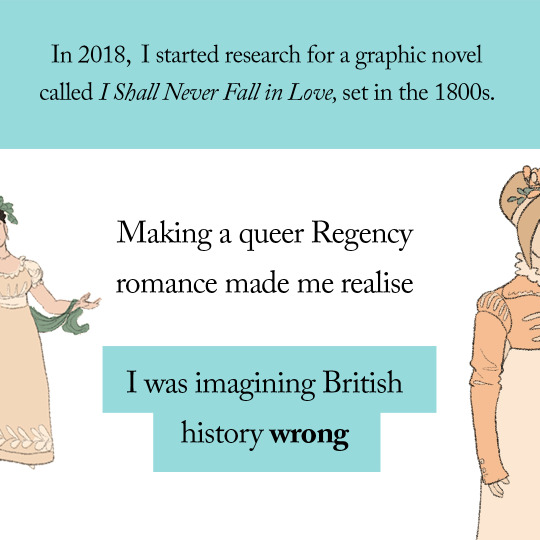

Excuse the format (I made this for instagram since that's what the publisher wants, rip) but this is basically a shorter, easy-to-read version of the history section at the back of my new book.

(Part 2 || The book)

---

Disclaimer: I'm extremely not an expert, and this is only scratching the very surface of complex topics that are hard to simplify. I mostly made this to EXTREMELY rec these books and podcasts, and would urge you to go check them out if you're not familiar!!

This stuff might seem obvious to some of you, but let me tell you, I do NOT think it's widely known in the general UK population.

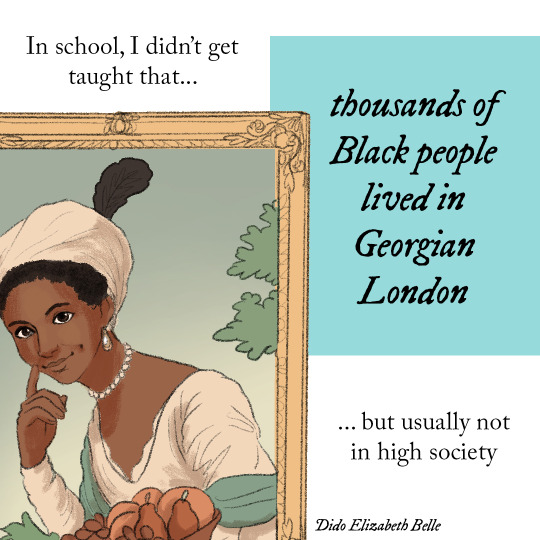

Imo a lot of the general (especially white) public think that the Windrush generation - Caribbean migrants brought in to help rebuild postwar Britain in the 50s - were the first Black communities in the UK. And yet there's deliberately not much focus on why the Caribbean has links with northern europe. HMMMM

(Britain loves, for example, to celebrate the abolition of slavery without mentioning WHAT CAME BEFORE IT - Britain being the biggest trader of enslaved people, with more than 1 million people enslaved in the British Caribbean. They literally just did it overseas.)

Telling the truth about history or British imperialism gets this massive manufactured backlash at the moment. There are so many ideas prevalent in UK politics - anti-Black, anti-refugee, anti-trans - based on going ‘back’ to some imaginary version of the past. Those are enabled by a long tradition of carving parts out of the historical record, and being selective about whose histories get told and preserved. Even though the book I was making is a fun rom-com, by the time I finished researching, I decided to make an illustrated history section at the back too (this is a mini version). My hope is that readers who haven’t come across these histories might get an introduction to them - and some pointers of what they could read next to get a clearer view of our past.

#i feel like it's also gone the other way a bit#where some people imagine a sanitised bridgerton version of historical britain where racism doesnt exist?#trying to speak to BOTH groups#but like. you can't understand british history without the white supremacy inherent in its empire building. that IS british history#can't overstate how impossible it was to read anything about 1800s england without being clobbered round the face with colonialism#anyway uk people pls read at least one imperial history book by someone who's not white AND not entrenched in establishment revisionism#i shall make a tag for this in the hope i do more#hari's history corner

986 notes

·

View notes

Text

"How We Win The Civil War" by Steve Phillips is a really good history/political book about how confederates and their successors have continued to promote white supremacy in the US after officially losing the war, and how the advocates of equality and a multi-racial democracy can finally win the war for real.

Very accessible and interesting throughout. Very well sourced as well. Highly recommended.

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

IWTV S2 Ep7 Musings - The Trial: "But It's Not About Race~!" said the (white) fandom

The Blacks (play) - Wikipedia "Do the white thing," The Guardian (2017)

#interview with the vampire#racism#racial inequality#louis de pointe du lac#iwtv tvc metas#louis de pointe du black#democracy of hypocrisy#read a dang history book#like wtf

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancestors Neely Fuller Jr. & Dr. Frances Cress Welsing...

Two of the greatest minds we've ever had. 👑🕊️🧠📚✊🏿✨❤️🖤💚🔥🔥🔥🔥🙏🏿🙏🏿

#neely fuller jr#frances cress welsing#black history#history#reading#books#information#knowledge#sunbookie#bookshelf#mental health#racism#psychology

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having a fearful moment where I think one of my friends might be transphobic.

#personal#we were talking about video games and the topic switched to Hogwarts Legacy#because my friend is still an active Harry Potter fan in 2025#and let me start with the fact that I’ve always tried to assume they just didn’t know about how awful J K is#but yesterday proved that they are aware#because they were upset that the girl characters don’t have the option to wear pants and can only wear skirts#I replied by saying how that would line up with J K’s terf nature and she’d probably hate to see a woman in pants#to which my friend said ‘but she put a trans character in the game!’#what I should’ve said to that was ‘that doesn’t excuse her history of transphobia and trans misogyny’#instead I said that wasn’t even a good portrayal#I mean for fucks sake she named her Sirona Ryan#like making a character based on the people you hate doesn’t make it okay???#that’s a real ‘I can’t be racist I have black friends’ excuse#and I might have to be an adult and ask my friend if they can really overlook J K’s history of transphobia and racism that easy#(and the rampant antisemitism in that game)#for the sake of a bland game and even blander new movies#like having an attachment to books you read as a kid is understandable#but I lose that ability to understand when you’re actively putting more money in her pockets#I’m stressing cause I can tell they didn’t like that I brought up how J K is a bad person

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

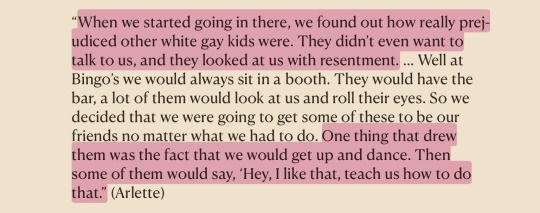

a Black fem (Arlette) & stud (Jodi) on racism from white butches & fems in the 1950s

from Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community by Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy & Madeline D. Davis (1994)

excerpt 1:

“When we started going in there, we found out how really prejudiced other white gay kids were. They didn’t even want to talk to us, and they looked at us with resentment. … Well at Bingo’s we would always sit in a booth. They would have the bar, a lot of them would look at us and roll their eyes. So we decided that we were going to get some of these to be our friends no matter what we had to do. One thing that drew them was the fact that we would get up and dance. Then some of them would say, ‘Hey, I like that, teach us how to do that.’” (Arlette)

excerpt 2:

Jodi remembers that the presence of Black studs made many white butches nervous: “Some of the stuff that happened was so typically racist, it was so ridiculous. I mean it was like Black studs were coming into the bar, people would just kind of put their arm around their women … [as if] they were just coming in there to snatch up their women.”

excerpt 3:

White lesbians also attended [house parties] but not in large numbers. This was resented by those Black lesbians who wanted a racially mixed community. “White kids started coming. Now they come up with, ‘that neighborhood,’ which I resent. Because there’s no such neighborhood that anybody’s gonna attack you. I get mad at that. ‘Well where do you live? I don’t want to come over there.’ What do you mean you don’t want to come over there?” (Arlette).

#butch/femme#stud/femme#queer history#racism#antiblackness#quotes#image described#boots of leather slippers of gold#mac’s bookshelf#at least 2 other narrators (a white butch & a stud) mentioned the racist comments about ‘neighborhoods’ but they were more tolerant of that#so i chose Arlette’s quote instead.#anyway the fact that white butches & fems only started talking to Black people at the bars when they wanted to benefit from Black dances?#possibly the singular most ‘holy fuck it’s just the same shit all the way back’ moment reading this book

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The list of banned young adult (YA) books by Black authors above, was retrieved from PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans (July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022). In addition to the book titles and authors, the document lists the state, district, type of ban, date of challenge/removal, and origin of challenge. The document is being updated periodically, so check for new books added. Visit the PEN America link above for a detailed definition of a school book ban.

bcbooksandauthors.com

#books#banned books#young adult#booklr#books and reading#reading#bookworm#currently reading#black people#black lives matter#blacklivesmatter#black excellence#black pride#black culture#black history#african american#racism#racial injustice#race in america#race issues

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your National Anthem in Above Ground by Clint Smith

#reading recommendation#poetry#Clint Smith#Above Ground: Your National Anthem#just listened to him read several poems from his recent book#he was featured on Here&Now on WBEZ and WBUR#He is also the author of 'How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America'#racism#antiblackness

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is what i imagine taylor swift was thinking of when she said 1830s without the racism

#decidedly didnt include orientalist paintings but did include a book of mormon bc i thought it was funny#so not really free of racism.#jordan talks#she wants to do her whole poet thing im assigning her some poetry readings from tennysons lady of shallott#its 2 am dont mind me#i just finished a 19th century (european) art history class can u tell#sorry it should be the revised frankenstein but hey. still existed then#imagine she said 1930s instead ……… Depression core with a capital D

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think love and light spirituality is toxic?

Definitely yes.

Now some of you will run away just from reading those two words, let me elaborate: It's not just toxic, it's actively harmful and racist, ableist, it's white cis hetero male supremacist in every way. Completely rooted in naz1 ideas from the very beginning of it. You just gotta look at the history of the whole movement and there's flaming red flags everywhere.

But even if you don't know the history and social context of how it came to be and popularized (which you should, do your research), just by looking at these people and how they move through life you can still clearly see the issues with it.

I have 3 main problems with the whole "love and light" thing that a lot of new age people spread, the first and biggest for me is spiritual bypassing. New Age "love & light" culture is not only completely incorrect (the dark is just as important, real and necessary for balance as the light, really, I'm saying it as someone with 10+ years of experience and a whole family background in ancestral traditions. The dark shit is Important and necessary, to understand all aspects of life, spiritual and not, to grow as a person and as a practitioner, to protect yourself and yours from both material and spiritual things and to fight either if needed.) but the whole "good vibes only" ends up being delusional at best and straight out abusive at worst, many times gaslighting people and denying racism, colonialism, oppression of all kinds, spiritual and physical illness, mental illness, basic history and science, all things that can have very real, physical consequences on people's mental health, overall health, and safety in general, not to mention the wider effects on society as a whole (having people running around with the emotional inteligence of a clam shell, scratch that, even clams are better than that lmao and spreading misinformation and harm like wildfire). The Second big mess is how much it promotes the complete lack of literacy and rational critical thinking. People will learn a new fancy thing and just run with it without knowing the full history and correct use of things and words, without questioning the source and context of the whole situation. Misinterpreting the little knowledge they have, either because it's something they overheard, or read in 1 book and never bothered to dive deeper into it's roots and history and true meaning, having the most shallow and incorrect "knowledge" of things, etc. It goes hand in hand with the 1st problem to create the 3rd issue: straight out willful malicious ignorance. They don't know any better and they can't be bothered to learn any better either. It's not just laziness or disinterest, it's straight out conscious denial of truth, repression of their own feelings and thoughts and identity even in some cases, to just be able to keep this facade of "love & light" that's killing them from the inside, hurting themselves and hurting anyone they come into contact with aswell, all to serve their selfish purposes and their own agendas.

All these three things feed off and enhance each other in an endless loop, that gets even worse in the kinds of conspiracy theory echo chambers these people move in. The ignorance and immaturity combined with someone who doesn't do any introspection at all and is straight out lying to themselves and others, either from a place of delusion, or in the case of most white people, priviledge. It's a huge system that only feeds white supremacy and keeps people of color disconnected from their true feelings and health, personal identity, culture and community, taking people away from any and every possible source of real power. It's keeping the priviledged in power and the disenfranchised in misery while denying the whole situation, spreading misinfo to confuse, divide and put the blame on the victims instead of the actual victimizer.

Priviledged people spread misinformation and lies because they don't know and don't care + actively benefit from keeping you in the dark, all while screaming from the top of their lungs that they have your best interests at heart and will "shine light on truths" while their actions are the complete opposite of that, then hide from the results of anything harmful they do under the "love & light positive thoughts only" thing to avoid conflict and consequences. It's bullshit. Call them out on their bullshit everytime.

#I love my people#but some of y'all got some serious undiagnosed mental illness going on and don't want to acknowledge it#got people thinking they're atlantean kemet aliens when their true african ancestors side eye and sigh#know yourself#know your people#know WHITE FOLKS WILL SAY THE CRAZIEST SHIT JUST TO KEEP YOU AWAY FROM YOUR TRUE POWER and SOME!! OF Y'ALL DEEPTHROATING THAT SHIT!!!!#without even knowing it was yt folks that made it up to justify racism and eugenics like !!!#and know mentall illness is a real thing that leaves you seriously exposed to these kinds of abusive environments#so keep that in check and stay in touch with reality thankyewww#seriously read some actual history books and even better: TALK TO PROPER ELDERS.....NONE of them is gonna mention anything like#what you hear from new age folks#cause all new age shit was made up less than 100 years ago and WE!!! GO BACK!!! 400+ years!!!! just as diaspora!!!! THOUSANDS as natives!!!#(american or african or else)#tap into THAT!!!!

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

it drives me nuts how much suffering we force people to go through to meet some arbitrary idealized standard vs something that'd actually help. they're making my 60 yr old mom with fibro take pain management classes because they're too scared to put her on the prescription pain meds that she was already on before. i just read about someone with adhd talking about how the only med that works really well for them without making them depressed when it wears off or causing anxiety is desoxyn but doctors are too afraid to prescribe it to them because it's technically methamphetamine. the drug war is a complete burden on society

#when you know even a little bit of the history of the war on drugs you will go fucking insane.#i dont mean the reagan administration war on drugs i mean the harry anslinger war on drugs#i genuinely need to do more reading cause i cant just recommend the same two books all the time but uh#you all should read chasing the scream and high price :)#i'm gonna be doing more research in the meantime to see if there's more i can recommend than just those two#fun fact the reason why a lot of drugs are illegal worldwide is because of the US threatening sanctions :) :) :)#china didn't want to initially ban opium dens because it was a long standing tradition but the US threatened them :) :) :)#there was a program in britain to provide prescription drugs to addicts (of the drug they were addicted to) that was working !#really well! the addicts turned their lives around substantially ! but the US threatened britian about it :) :) :)#and shut the program down. almost all the addicts went on to DIE right after#and the fucking racism. hoh boy the fucking racism.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Rhythm and blues was too good to remain a black secret for long and as the fifties dawned, certain musically adventurous white DJs started to add it to their playlists. By 1956 a quarter of the best-selling US records would be by black singers. This move was accelerated by the dramatic commercial success of some of the new black stations, exemplified by WDAI in Memphis - since 1948 the first black-owned radio station - which, as well as being home of DJs BB King and Rufus Thomas (he of the 'Funky Chicken'), was extremely profitable.

In adopting this subversive music, white DJs also started adopting black slang. This 'broadcast blackface', as Nelson George calls it, let them speak (and advertise) to both the black community and younger whites. Dewey Phillips of Memphis's WHBG was so successful at integrating his audience that the wily Sam Phillips of Sun Records chose him to broadcast Elvis Presley's first single.

The idea of the 'white negro' was still born of racism, however. George recounts the amazing tale of Vernon Winslow, a former university design teacher with a deep knowledge of jazz, who was denied a radio announcing job on New Orleans' WJMR simply because he was black. After what seemed like a successful interview, Winslow, who was quite light-skinned, was asked, 'By the way, are you a nigger?' Denied an on-air job merely because of his race, Winslow was hired for a most extraordinary job. He was to train a white DJ to sound black. Winslow had to feed a white colleague - now christened Poppa Stoppa - with the latest local slang, teaching him to say things like 'Look at the gold tooth, Ruth' and 'Wham bam, thank you ma'am'. The show became a smash. One night, frustrated by his behind-the-scenes existence, Winslow snuck a turn at the mic. He was fired immediately. WJMR kept the Poppa Stoppa name and continued using a white man, Clarence Hamman, to provide Poppa's voice. (Winslow had his revenge, though, as Doctor Daddy-O on New Orleans' WEZZ where he would become one of the country's top ten DJs.)"

- excerpt from Last Night a DJ Saved My Life by Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton

#black american history#dj history#dj tag#music history#radio history#racism#new orleans history#black music history#vernon winslow#book im reading right now

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

TW for racism and genocide of Native Americans

Today I learned that the original "The only good _, is a dead _," was "The only good Indian, is a dead Indian." And it really sucks that now I know this information.

Looks like it's speculated to be attributed to one specific Union general due to his actions, but it was more likely just a common anti-Native sentiment of the time held by a lot of the settlers, not just one person.

Like I know I hear 'the only good snake, is a dead snake' most often since I love being in snake discussion groups, which also sucks because I love snakes, and they shouldn't be killed.

But I've also heard like 'the only good Nazi, is a dead Nazi.' And like, I So agree with that, fuck Nazis, but I don't want to think about the original phrase being reclaimed like that for a laugh, no matter how much I agree that Nazis suck.

It should stay as horrifying and sickening as 'the only good Indian, is a dead Indian' in my opinion. I think we should retire the phrase entirely and just note that, that was the origin of it - the continued genocide of Native Americans during the 1800s when settlers were eager to get rid of us so they could claim property for themselves while forcing us into insufficient reservations as US America expanded westward.

This book I'm reading describes that the usual retaliation for the theft of a cow would have been the execution of an entire Indian village. One specific horrifying example given, is from accounts of a traveler that joined a group of Mexicans pursuing Indians (Chumash) in possession of stolen horses. They come across a group of some old Indians, women and children, drying the horse meat. Every last one was killed, and their ears cut off as proof for the priests that they made every effort to retrieve the horses.

This shit is so sickening. They were hungry and trying to survive.

It also describes how the accounts of Indians from my tribe before the mission system were all about how generous and welcoming they were. (Though, it was through the lens of the Spanish who saw us as ideal candidates for conversion because of this.) Then after the collapse of the missions and post-assimilation, the accounts simply describe the Indians' drunkenness and disorder. What did you expect???? You assimilate a group of people so they're entirely reliant on you (the rigid structure of the mission system and the dismantling of their previous tribal villages), and then suddenly turn them out to a world without their previous villages and social order. Of course they're going to struggle and suffer and abuse the drugs (alcohol) you introduced them to.

I hate this so much.

The book also mentions how, during the mission period, anyone who ran away from the missions to go back to their original tribal lives, would be dragged back to the missions and cruelly punished with restraints, lashing, or stocks, and they couldn't understand why because punishment was exceedingly rare before Spanish rule.

Ugh. Anyway.

I'm going to bring this up any time I hear anyone mention that phrase, because the horror of that time period should not be diminished in its modern reclamation. ('Diminished,' because I, a 30yo Native American, did not even know the origin. I thought it was a modern phrase. Our local Native history was always glossed over in school to focus on the mission system. I didn't even learn of my tribe's revolt until like 2016 when I went to a lecture my tribe held.)

I get that reclamation is supposed to be like a good thing, to take away the power of its original use, but I personally don't think that's appropriate for this phrase that was used as a rally for genocide.

Maybe I'm just being a sensitive baby, though, who knows! I'm crying while reading a history book about my tribe. This shit really hurts deep, though. It always has.

#native#native american#n8v#ndn#the only good indian is a dead indian#history#american indian#indigenous#chumash#california#idk what to tag this bro#racism#genocide#prob gonna get this post blacklisted for that word with the current world events ugh#ill just leave it at that for now im not done w the book yet so i might post more when i get to the actual purpose of the book#this is just like part of the intro to set the historical background the book is focused on our cave art and i havent gotten there yet#Cori.exe#Post.exe#maybe this was something obvious to other people but i literally had no idea i dont watch westerns or anything...#...like that where i couldve heard the original phrase before today#this is the shit those 'parents rights' nuts dont want youth educated about#but we need to learn this even when its extremely uncomfortable because this is how life was for people in the 1800s#anyway ill leave it at that i wanna get through this book its already been renewed once and i still have a lot more to read

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

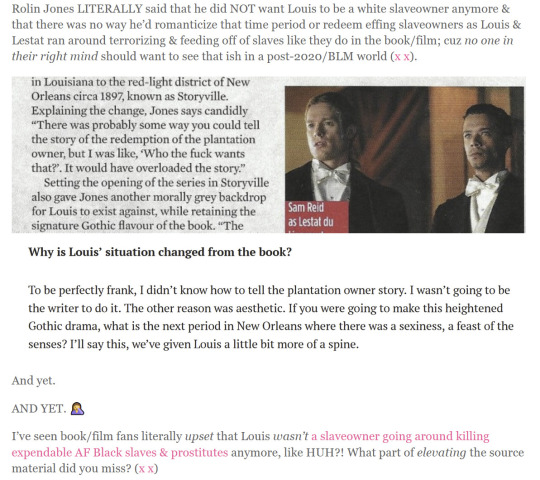

IWTV Musings: Racism & Intersectionality, in Hollywood and in Fandom Spaces (Pt1: The Raceswaps)

This is in response/support of @adamnablelittledevil's post on this very subject:

"Hopefully people would finally understand nobody is making it up or exaggerating and it is indeed real and worse than they probably think."

Folk try to act like certain problems don't exist, especially when it concerns Black & Bipoc people in predominately white spaces with a KNOWN history of racism. People love to gaslight & be dismissive & rewrite history with revisionist narratives--especially to impressionable people & fans who are NEW to certain fandom spaces or racial dynamics/demographics, and DON'T know the history of the spaces they're entering, or the convos taking place--which is PRECISELY how we wound up with non-Black IWTV fans who ended up in the actual NEWS for prancing around an IRL plantation in 2024, acting like they never heard of slavery, ffs.

At some point, the venn diagram of accidental/willful ignorance, careless/irresponsible tone deafness, and active/passive-aggressive racism actually does intersect.

Incidents like this reflect a fandom steeped in problematic behavior that's too-long gone unchecked by the fans & network alike--who are also at fault for constantly mishandling its own project.

Contrary to poorly researched articles like USA today that denied/handwaved racist backlash against IWTV (a MUCH smaller & younger fandom compared to the LOTR & Amazon's Rings of Power adaptation), from its very inception, as early as the cast announcements, TVC's white fans were PISSED about the raceswaps & outright accused AMC of being woke/DEI (a la Bridgerton) when Jacob Anderson was cast as Louis DPDL.

A Quora thread from 2021:

A Reddit thread from July 2022: (Wayback Machine)

A Reddit thread from 2022 (circa Ep5): (Wayback Machine)

And boy oh boy did this one on Facebook in 2021 age poorly: 💀

Book fans constantly treat AMC's IWTV like performative colorblind trash, rather than as color-conscious prestige tv show that treats historical racism, colorism, classism, sexism, & homophobia seriously. They DGAF what showrunner Rolin Jones had to say about perpetuating the glorification of slaveowners, and just want a 1:1 adaptation of the books, when that was NEVER Rolin's intention.

There's fans who to this day refuse to see/accept Delainey!Claudia, and apparently there's colorist trends on Twitter (cuz ofc 🙄😒) about seeing her as Armand's daughter instead of Lestat's, just cuz of her skin color, which WTF??? (x x x):

Book/film fans hypocritically complain constantly about Bailey Bass (18-19) AND Delainey Hayles (25) playing 14y/o Claudia; but then gush about Vampire Diaries & Twilight & other shows on MTV & CW--who have all casted full grown adults as teenagers. Critiques like this are interesting (x x):

Cuz they specifically mention the Romanian kids and how Claudia supposedly "cannot at all pass for a child." However:

Some of those actual children ain't exactly tiny little toddlers & tykes either! 😅 Cuz age is a spectrum, not a monolith, imagine that.

And laaaawd don't get me started on Armand, and the BS that was happening on Reddit a few years ago (x x):

THIS is the kind of fandom we've been dealing with since DAY ONE.

And yet white fans have the nerve to whine about how tired and pissed they are whenever Bipoc fans call out the racism in the fandom/network, or god forbid look too-deep in the actual racially sensitive/relevant context of the show itself.

But I'll save my thoughts on all that for another post.

#interview with the vampire#amc immortal universe#racial inequality#racism#louis de pointe du lac#justice for claudia#read a dang history book#meritocracy of hypocrisy#america#amerikkka#louis de pointe du black

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

So you guys might have heard me mention this thing called Operation Ajax. Operation Ajax -- known as Operation Boot in the UK -- was a coup carried out against the 1953 Iranian prime minister by the US and UK governments. You can read about it in the book All The Shah's Men by Stephen Kinzer, but I just found this meme and it really drove home what an absolutely disgusting racist Dwight Eisenhower -- the US president behind the coup -- was.

Cause it feels like the name Operation Ajax was chosen to show how he thought white Christians were stronger than Muslims and South-East(?) Asians.

Fun Fact: Operation Ajax served as the inspiration for Frank Herbert's scifi book series Dune -- the plot is a metaphor for oil wars🙃

#random thoughts#eww#only in america#us history#global history#the middle east#christofascism#dwight eisenhower#this is so gross#books books books#books and reading#things they dont want you to know#all the shahs men#dune#racism#islamophobia

3 notes

·

View notes