#provençal literature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

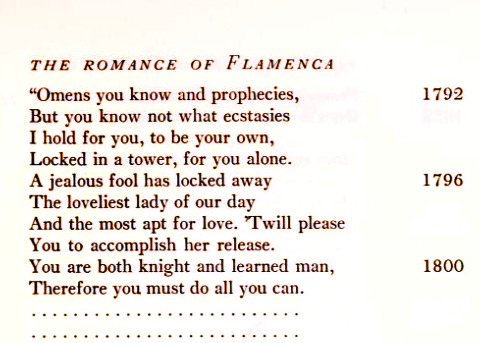

The Romance of Flamenca is an anonymous novel of the 13th century written in old occitan.

The novel recounts the torments that Archambaut de Borbon inflicts on his wife, the young and beautiful Flamenca. The precautions taken by the jealous husband to isolate Flamenca from other men, lead to his punishment by provoking a love affair between the lady and the knight Guilhem de Nivers.

~~~

The Romance of Flamenca is the kind of story that Sansa Stark & GRRM would love.

The novel is hyper descriptive of all the heraldry and all the pageantry of the events that take place in the story: weddings, tournaments and feasts full of bards and troubadours, something that GRRM really loves.

The story is about courtly love with a radiant lady pursued by many suitors -a couple of kings included, a jealous malicious queen, a courtious lord husband that becomes a brute because of jealousy, then the radiant lady is locked in a tower, but there's a true knight on a quest to her rescue. Later, the lovers meet in hotsprings, and during the final tourney, that takes place in a meadow, the radiant lady wears the crown of beauty, but we don't know how the tourney ends . . . . (the only copy of the ancient manuscript is incomplete).

In addition to the similarities already mentioned, the two ladies that loyaly serve Flamenca are called Alis (Alys) and Margarida (Margaery), and there's also a Count of Brienne mentioned.

Rosalía's album 'El Mal Querer' was inspired by The Romance of Flamenca.

'El Mal Querer' can be traslated as 'Bad Love,' and that's precisely what Archambaut de Borbon gave Flamenca, a bad love, a toxic love, full of jealousy without motive, hence he was punished by Love itself that conspired to make Flamenca and Guilhem fall in love and consummate their passion.

One of my favorite lyrics from 'El Mal Querer' are from the song called 'A Ningún Hombre:'

Hasta que fuiste carcelero, you era tuya compañero, hasta que fuiste carcelero.

That can be trasnlated as:

Until you became my jailor, I was yours, partner; I was yours, until you became my jailor.

Finally, it's worth to mention that The Romance of Flamenca also has its own fanfiction called 'The story of Flamenca: the first modern novel, arranged from the Provençal original of the thirteenth century' by William Aspenwall Bradley, published in 1922, with the aim to give an end to the story of the fair Flamenca and her gallant Guilhem.

#the romance of flamenca#le roman de flamenca#medieval literature#occitan literature#provençal literature#sansa stark#asoiaf#grrm#rosalía#el mal querer#a ningún hombre

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daniel, Armand, and Keats???

Ok so the incredibly grainy footage of the new teaser has me spiraling! Devils minion on screen! But even more exciting, is Armand describing himself as “easeful death”, presumably to Daniel. Ok Rolin Jones, listen up. I don’t know a ton of literature by heart by I WAS a depressed and then chronically ill teen and early twenties person, who identified maybe a little too hard with romantic poet John Keats. Some of his poems are permanently tattooed on my brain. So I see what the writers are doing here. “easeful death” is from Ode to a Nightingale. The full line is: “Darkling I listen; and, for many a time/I have been half in love with easeful Death”. I mean. Come on.

I reread the poem after watching the trailer last night, and it’s actually SUCH a clever reference. It could practically be written by Daniel about Armand. We already know the writers room is familiar with and willing to reference other classic poets (Emily Dickinson absolutely is a vampire) so I think this is 100% intentional.

The narrator of the poem is tired of the difficulties of life and is longing for death; he speaks to the nightingale as a kind of immortal figure who is free from all cares. He is able to momentarily accompany the nightingale, at least mentally, as it flies and forget all troubles, but must come back to earth by the end of the poem. It’s pretty easy to read this as Daniel talking about Armand.

In fact, the first thing the speaker longs for is not death or the nightingale, but wine to take his mental pain away.

O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been

Cool'd a long age in the deep-delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green,

Dance, and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,

With beaded bubbles winking at the brim,

And purple-stained mouth;

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen

And we know that Daniel was numbing himself with drugs when he first met Louis and Armand. In fact the voiceover in the trailer almost feels like a pitch to Daniel; Armand is saying “I’m better than the best drug you’ve ever had”, effectively.

The speaker is determined to forget what the lucky nightingale (or Armand) “hast never known”:

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

The nightingale doesn’t know about the trials of living and aging, just like Armand. The speaker wants to forget about the inevitable “palsy shakes” that arrive with age. which could easily be a reference to what we now diagnose as Parkinson’s Disease.

At this point in the poem, the speaker tells the nightingale that he will join him in forgetting life not with the help of “Bacchus and his pards” (wine) but with “posey” (poetry). Which makes me think of Daniel using his writing to get closer to the vampires.

The fact that the speaker calls the nightingale “Darkling”! I mean what a perfect name for Armand. In fact I think this whole section is just perfectly about a vampire if you want it to be:

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call'd him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain,

While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad

In such an ecstasy!

Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain—

To thy high requiem become a sod.

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!

No hungry generations tread thee down;

The voice I hear this passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown

Armand was not born for death; he’s seen many an emperor and clown and in fact been both (leader of the coven, pretending to be Rashid). There’s also an emphasis on the nightingale’s song. I don’t know if Armand will be a musician at all in the show, but he and the coven are definitely performers.

In the last stanza, the speaker comes back to himself. He knows that he does not get to escape the burden of life for the ease of death, or at least not yet. It makes me wonder if Daniel will eventually turn down the gift at some point in the devils minion timeline. We know that he rejects Louis' mocking offer to give him the gift in the Dubai timeline.

Forlorn! the very word is like a bell

To toll me back from thee to my sole self!

Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well

As she is fam'd to do, deceiving elf.

Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades

Past the near meadows, over the still stream,

Up the hill-side; and now 'tis buried deep

In the next valley-glades:

Was it a vision, or a waking dream?

Fled is that music:—Do I wake or sleep?

The last line and the confusion about whether the time spent with the nightingale is a dream or not makes me think of Daniel waking up from the dream of Polynesian Mary’s.

In summary, Rolin Jones what the fuckkkkk. I’m so so excited about this season and all the Armand/Daniel content we’re about to get.

Oh also, as a bonus, if you want to hear Ben Whishaw recite the entire poem, and you definitely do, here you go:

youtube

#interview with the vampire#iwtv#my meta#devils minion#and john keats I guess!#armandaniel#interview with the vampire amc

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Georges Charles Brassens - sale petit bonhomme

I don't always post pictures of men I would like (or have liked) to sleep with. That might surprise you.

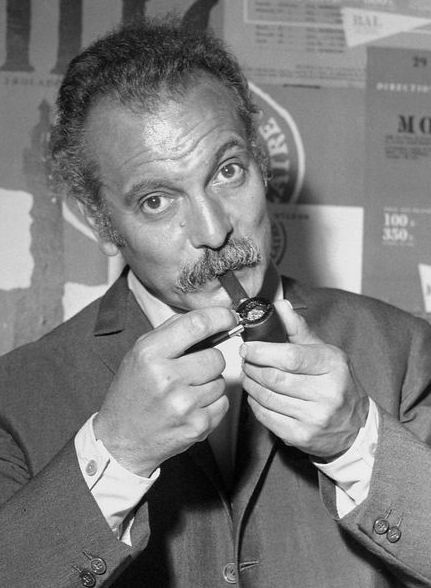

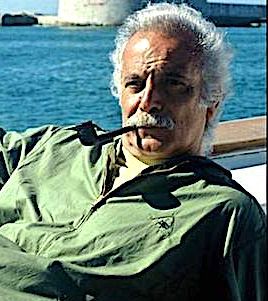

There are very few images of the man where I find a certain sexual attraction (although this one...maybe). For those of you who don't know, Georges Brassens (1921-1981) was a French singer-songwriter who became a French national treasure.

Self-taught in music and classical literature, his songs are masterworks of melodic complexity and literary gymnastics. Am I getting carried away here? Yes, probably. He was a genius and a hero of mine and one of my two favourite artists (Brel being the other, and I cannot decide which of them I love most).

He could also be obscene (listen to Le Gorille or Le Temps ne fait rien à l'affaire) for which he was criticised, so he produced Le Pornographe du phonographe. He also wrote La Mauvaise réputation, currently my favourite, about being frowned upon by les braves gens.

Famous as a pipe-smoker (though he occasionally smoked cigars), politically engaged and with a wonderful deep voice and Provençal accent. Listen to Mourir pour des idées, one of the angriest songs I've ever heard.

He died aged 60 (looking at the image above it's hard to believe he was that young), but he packed in at least two lifetimes of wonderful songs that live on. Oh, and the moustache. Mustn't overlook the moustache.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Award-winning culinary travel author Carole Bumpus releases new book

While the red poppy of Spring and Summer brings to mind Veterans Day, for culinary travel writer Carole Bumpus, the red poppy is one of many things that makes Provence, France more than memorable.

This November 12, Bumpus released ADVENTURES ON LAND AND SEA: Searching for Culinary Pleasures in Provence and the Cote d'Azur,

Praised by Booklist as … “a charming introduction to the South of France and an excellent reading companion to Peter Mayle's now-classics like ‘A Year in Provence’ and ‘Toujours Provence,’” Bumpus is honored and delighted by the praise.

She remarked. “I was pulled in by the delight I saw in Peter Mayne’s magical book, ‘A Year in Provence,’ as my husband Winston and I decided to go to France for the first time in the 1990s. We discovered the charm of the people and the beauty of place, high in the hills above Cannes.”

This new release is Book Four of her award-winning culinary-travel series, ‘Savoring the Olde Ways…’

Travel-literature affectionados will affirm that all of the books in her series are enjoyable as stand-alone guides in and of themselves.

In this book in particular, Bumpus is on a quest to find the real Provençe.

In recalling further that first time visit, she noted. “And, then we were hooked with the history, whether along the shores or in the mountains, as well as our love of trying the wines, olive oils, and the delectable offerings in a farmers market, including succulent olives, tomatoes, peaches, plus, strawberries as big as your fist and . . . . Oh, exclaimed Bumpus, it all was so marvelous!”

Because of the marvelous aspects of France, it was only a few years later on another trip, she unexpectedly, stumbled into an opportunity to write a historical novel. It was entitled “A Cup of Redemption.”

That unexpected experience and novel, changed the course of her career.

Since then Bumpus has continued to be an award-winning culinary-travel author, extending her adventures to Italy and beyond.

Audiences will be given a one-of-a-kind look at Provence, one of Europe’s most coveted spots.

‘ADVENTURES ON LAND AND SEA: Searching for Culinary Pleasures in Provence and the Côte d’Azur’ will provide lots of details that only someone who loves travel can share.

During the three separate excursions in the new book—from Nice to Nîmes, Moustiers to Marseilles,and San Tropez to San Remy—Bumpus invites you to come along as she uncovers the mysteries of Provençal customs, traditions, and ancient cooking.

Usually, when people think of French cuisine they often imagine an expensive and elaborate restaurant setting.

Yet, as Bumpus explained. “At its heart French cooking is really about simple foods such as onions, garlic, mushrooms, etc.”

“It can be described as ‘peasant food’ said Bumpus, a food of the people because it can be enjoyed by everyone.”

The ‘good life’ as some people exclaim about France isn’t as out of reach as one might think. As Bumpus tries to convey to the readers, the genuine ‘good life’ is to appreciate life.

Good food and gracious living is more about being open to life and nature’s bounty rather than an ‘elite-mindset.’

Bumpus has discovered in her travels of more than 25 years, that the people of Europe, especially France are more about a Joie de vivre - a joy of living than anything else.

Reviews have proclaimed the book as informative, fun, sometimes funny, and filled with goodwill,

‘ADVENTURES ON LAND AND SEA Searching for Culinary Pleasures in Provence and the Cote d'Azur, is travel writing at its best.

For more information about Carole Bumpus and her new book, visit her website.

0 notes

Text

Historical figures who used Anagrams: Thomas Billon.

Anagrams flourished in 17th-century European literature. In France, Louis XIII, the Bourbon monarch, named Provençal native Billon as Royal Anagrammatist. Billon's court duties involved crafting prophetic, entertaining, and mystical anagrams, often based on individuals' names.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Like... I enjoy linguistics and I don't mind medieval literature in general/troubadour songs as a genre or whatever like they're literally fine but specifically the fact that romance philology is a dying discipline that nobody gives a fuck about other than my prof and like 4 other technologically incompetent guys who made a completely unusable online dictionary of ancient provençal dialect is literally making me sick like your discipline is dying because it's literally extremely inaccessible even to poor cunts like me who only have to take one exam about it and then never have to see it again let alone anyone who's actually thinking of studying this in a serious manner... 🧍♂️ Please hire someone to make your online dictionaries less dogshit

I whole heartedly hope everyone involved in the birth of romance philology as a discipline is roasting in hell rn. 🫶

#🗨️#throwback to when we were translating a song in class and the site crashed because “too much traffic” and literally 13 of us had it open

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 Poems About Food

Food has always played a central role in human experience, serving not only as sustenance but also as a source of inspiration and expression in art and literature. Poets have long captured the essence of food in their work, exploring themes of culture, memory, love, and even identity. This article delves into eleven notable poems that celebrate food in its various forms, showcasing how these works highlight the emotional and cultural significance of culinary experiences.

1. This Is Just to Say by William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams’ poem This Is Just to Say is a charming, light-hearted confession that captures the human experience of temptation and indulgence. The poem opens with a simple declaration of guilt.

I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox

In this brief yet powerful work, the speaker acknowledges having devoured the plums meant for someone else. The poem continues with an apology, reflecting a playful tone as the speaker describes the sweet taste of the plums.

and which you were probably saving for breakfast.

The casualness of the language invites readers to empathize with the speaker’s small transgression. This poem captures the joys of food, temptation, and the human condition.

Analysis of Themes

The themes of desire and guilt are central to this poem. The simplicity of the event—a snack taken from the icebox—highlights how even small actions related to food can carry emotional weight. Williams encapsulates the complexities of human relationships, all within the confines of a kitchen. This poem exemplifies how food can symbolize indulgence, guilt, and the everyday moments that define our lives.

2. The Bean Eaters by Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks’ The Bean Eaters presents a poignant portrait of an elderly couple who lead a humble life. The poem begins by depicting their simple diet.

They eat beans mostly, this old yellow pair. Dinner is a casual affair.

Brooks uses straightforward language to portray the couple’s life, and the repetition of “they eat beans” emphasizes the monotony and simplicity of their meals. The beans symbolize their financial struggles and enduring love.

They buy the beans by the flat And they eat beans mostly.

Despite their poverty, the couple finds comfort in their shared meals. The poem reveals how food can reflect not only socioeconomic status but also the warmth of companionship.

Analysis of Themes

The Bean Eaters explores themes of poverty, resilience, and the beauty found in everyday life. Brooks highlights the couple’s ability to find joy in their simple meals. Food, in this case, transcends mere sustenance; it becomes a symbol of their shared existence. The poem invites readers to appreciate the significance of food in relationships and the small yet profound moments that define a life together.

3. Ode to a Nightingale by John Keats

In Ode to a Nightingale, John Keats meditates on beauty and mortality, using food as a metaphor for life’s fleeting pleasures. The poem opens with the speaker longing for a taste of wine.

O for a draught of vintage! that hath been Cool’d a long age in the deep-delved earth, Tasting of Flora and the country green, Dance, and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

Here, Keats intertwines the richness of wine with the joys of life, reflecting on how food and drink can provide an escape from reality. The speaker’s desire for vintage wine symbolizes a yearning for beauty and transcendence.

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen, And with thee fade away into the forest dim:

The poem captures the connection between food, pleasure, and the ephemeral nature of life. Keats elevates the simple act of drinking into a profound reflection on existence.

Analysis of Themes

The poem explores themes of beauty, mortality, and the transient nature of pleasure. Food, represented by wine, becomes a means of experiencing the richness of life. Keats’ imagery evokes the senses and highlights the role of food in the quest for joy. The poem serves as a reminder of the complexities inherent in our relationship with food and the emotions it can evoke.

4. Eating Together by Li-Young Lee

Li-Young Lee’s Eating Together is a tender exploration of family and the significance of shared meals. The poem begins with a warm depiction of a family gathering.

In the steamer, a catfish swims, its mouth open wide, its heart a hunk of ice.

The imagery immerses readers in the sensory experience of preparing food, highlighting the importance of cooking as a familial ritual. The catfish represents nourishment and connection.

I want to see my father’s face, his eyes like two saucers full of sugar.

Lee’s longing for connection underscores the emotional weight of shared meals. The poem beautifully captures how food can bring family together and evoke feelings of love and nostalgia.

Analysis of Themes

Eating Together emphasizes themes of family, connection, and the shared experience of food. Lee illustrates how meals can create lasting memories and strengthen bonds between loved ones. The poem serves as a reminder of the importance of food in nurturing relationships and the joy that comes from sharing meals.

5. To a Daughter Leaving Home by Linda Pastan

In To a Daughter Leaving Home, Linda Pastan uses food to symbolize the bittersweet emotions associated with a daughter growing up and leaving home. The poem opens with a nostalgic memory of teaching her daughter to ride a bike.

When I taught you at eight to ride a bicycle, you fell off the first time, and I ran to you, picked you up, and kissed you.

The imagery of falling and rising reflects the challenges of growth and the protective instincts of a mother. The act of sharing meals becomes a comforting backdrop to the evolving relationship.

The last time I saw you, you were in your new home, a whole world of your own.

Pastan’s use of food imagery evokes warmth and nostalgia, illustrating how meals symbolize nurturing and care.

Analysis of Themes

To a Daughter Leaving Home explores themes of motherhood, growth, and the passage of time. Pastan’s use of food as a metaphor highlights the emotional ties between mothers and daughters. The poem invites readers to reflect on their own familial relationships and the bittersweet nature of growing up.

6. The Fish by Elizabeth Bishop

In The Fish, Elizabeth Bishop presents a vivid encounter with a fish that symbolizes struggle and beauty. The poem opens with a detailed description of the fish caught by the speaker.

I caught a tremendous fish and held him beside the boat half out of water, with my hook fast in a corner of his mouth.

Bishop’s imagery immerses readers in the sensory experience of fishing, emphasizing the relationship between humans and nature. The fish represents both sustenance and the beauty of life.

He was speckled and browned with barnacles, like the pattern of a painted bowl.

The detailed description highlights the fish’s beauty, elevating it beyond a mere object of consumption.

Analysis of Themes

The Fish explores themes of struggle, respect for nature, and the interconnectedness of life. Bishop’s vivid imagery invites readers to appreciate the complexity of food and its role in the human experience. The poem serves as a reminder of the significance of food in survival and the beauty found in nature.

7. The Pancake by E.E. Cummings

E.E. Cummings’ poem The Pancake celebrates the joy of cooking and the simple pleasures of breakfast. The poem opens with a cheerful depiction of pancakes.

Oh, how happy we are to be here together! With a pancake on our plates,

Cummings’ playful language and rhythm create a sense of joy and excitement surrounding food. The pancake symbolizes comfort and happiness.

The sweet syrup flows, dripping down, a golden river on our plates.

The imagery evokes the sensory experience of breakfast, celebrating the joy of sharing meals with loved ones.

Analysis of Themes

The Pancake explores themes of joy, simplicity, and togetherness. Cummings celebrates the act of cooking and sharing meals, inviting readers to appreciate the small pleasures of life. The poem highlights how food can create moments of happiness and connection, enriching our daily experiences.

8. A Blessing by James Wright

In A Blessing, James Wright reflects on the beauty of nature and the joy of sharing food with a friend. The poem opens with a serene description of a moment in the natural world.

Just off the highway to Rochester, Minnesota, Twilight bounds softly forth on the grass.

Wright’s imagery sets a peaceful tone, inviting readers to connect with the natural world. The act of sharing food becomes a symbol of friendship and connection.

I could feel the warmth of their bodies And the smell of the food They were eating,

The poem captures the sensory experience of sharing a meal, emphasizing the bonds formed through food.

Analysis of Themes

A Blessing explores themes of friendship, connection, and the beauty of the natural world. Wright’s use of vivid imagery invites readers to appreciate the simple act of sharing food. The poem underscores the importance of connection and the role of food in fostering relationships, creating a sense of warmth and belonging.

9. Food by A.R. Ammons

A.R. Ammons’ poem Food offers a philosophical exploration of the relationship between food and existence. The poem opens with a reflection on the nature of food.

Food is a means of being; we eat to survive.

Ammons’ straightforward language emphasizes the fundamental role of food in life. The poem contemplates the significance of sustenance in the human experience.

What we eat becomes us, and we become what we eat.

The cyclical relationship between food and existence is a central theme in the poem. Ammons invites readers to reflect on the deeper connections between nourishment and identity.

Analysis of Themes

Food explores themes of survival, identity, and the interconnectedness of life. Ammons’ philosophical musings elevate food beyond mere sustenance, inviting readers to consider its role in shaping our identities. The poem serves as a reminder of the profound impact food has on our lives, extending beyond the physical act of eating.

10. Honey by Mary Oliver

In Honey, Mary Oliver captures the sweetness of life through the lens of food. The poem opens with a vivid description of honey.

I have a friend who is always bringing me honey,

Oliver’s imagery evokes the richness and sweetness of honey, symbolizing the joys of life. The act of sharing honey becomes a metaphor for connection and generosity.

And it is always a moment of delight.

The poem emphasizes the joy of sharing and the simple pleasures of life. Oliver celebrates the sweetness of relationships, inviting readers to reflect on the connections formed through food.

Analysis of Themes

Honey explores themes of generosity, sweetness, and the joy of sharing. Oliver’s use of vivid imagery creates a sense of warmth and connection, highlighting the significance of food in fostering relationships. The poem serves as a reminder of the beauty of simple pleasures and the impact of kindness in our lives.

11. The Fishmonger by Michael Donaghy

Michael Donaghy’s poem The Fishmonger presents a vivid portrait of a fish market, capturing the sensory experience of food shopping. The poem opens with a description of the fishmonger’s wares.

In the market, the fishmonger is a magician, his hands quick and sure,

Donaghy’s imagery immerses readers in the bustling atmosphere of the market, emphasizing the artistry of food preparation. The fishmonger becomes a symbol of skill and craftsmanship.

He lays out his catch, a rainbow of scales and fins.

The vibrant imagery highlights the beauty of fresh seafood, transforming the act of shopping into an art form.

Analysis of Themes

The Fishmonger explores themes of craftsmanship, artistry, and the sensory experience of food. Donaghy celebrates the skill of the fishmonger, inviting readers to appreciate the beauty of food preparation. The poem underscores the significance of food in our lives, connecting us to the artistry of cooking and the joy of sharing meals.

Conclusion

These eleven poems about food illustrate the diverse ways poets have explored the theme of nourishment throughout history. From the simple joys of shared meals to the complex relationships we have with food, these works invite readers to reflect on their own experiences. Food serves as a powerful metaphor for connection, love, and the human experience. Through these poems, we gain a deeper appreciation for the role food plays in our lives, enriching our understanding of culture, relationships, and the beauty of everyday moments. Whether it’s a simple meal shared with family or the artistry of a skilled chef, food continues to inspire poets and readers alike, reminding us of the richness of life’s culinary tapestry.

0 notes

Text

"[En Provence] La littérature en français ne s’y développe vraiment qu’à partir du XIXe siècle, en contact étroit avec langue et littérature provençales. Ces effets sont surtout perceptibles, d’une part, dans l’usage d’un français mêlé de provençal dans son lexique, et, d’autre part, dans des styles sous influence des façons de dire provençales. Au point qu’on peut parler d’une littérature francophone de Provence, à la fois pour la distinguer de l’expression littéraire en provençal et pour indiquer sa situation de littérature de contact entre deux langues et deux cultures, comme l’ont proposé des spécialistes de la littérature francophone de Bretagne."

#This is from a media I hate but it's interesting#Provençal#Provence#Marcel Pagnol#upthebaguette#French literature#Littérature française

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing a total social history of 18th Century New Orleans, Cécile Vidal offers to reframe it as a Caribbean outpost of the French Empire rather than [primarily] as a North American frontier town. [...] [Vidal] proposes [...] [the French] colonial period as one primarily affected by the relations with the main French colony of Saint-Domingue [Haiti] that “exhorted a profound influence on New Orleans society” (p. 9). More largely, this vantage point on the city aims at [...] situating “early North America history on the periphery of Caribbean history”, and, more broadly, “all American colonial and slave societies as parts of a continuum” (p .2). [...]

---

[S]tructural developments in the city’s history under French rule were often found at “the intersection between the North American and West Indian worlds” (p.23). [...] While exploring the contours of the city’s founding era until the 1731 Crown takeover, [Vidal’s first chapter] puts great care in replacing the city’s emergence within the specific imperial, Atlantic, and regional conditions, that ultimately led to the “Caribbeanization of New Orleans and Louisiana society” (p. 29).

Then, the colony came to a turning point in November 1729 after a deadly Natchez Indians’ attack on Fort Rosalie that “could have led to a complete inversion of the colonial order” (p. 106). The revolt [...] truly forms a turning point in this relation between race and empire analyzed throughout the book. It prompted a sharp migratory trend from the plantations back to the capital that eventually concentrated both the white and slave populations within the same area. For white colonists, this pitted the lower ranks of the urban population against the top urban dwellers formed by administrative officials and clergymen who sought to distinguish themselves by acquiring nearby plantations. For slaves, the general direction adopted was similar but the strategies different.

A “rival geography”, as Vidal puts it, was developed by slaves many of whom resorted to a petit marronage made of short-term escapes from their plantations or households in and around New Orleans, but also by a desire to find temporary employment, sometimes a one-day task, in the city, in order to “enjoy a more autonomous life” (p. 130) and attain a “measure of anonymity” (p. 131). Nevertheless, “disappearing was not easy” (p. 131) in a locale where patrolling militias and networks of control had been patiently built in the aftermath of the Natchez revolt. [...] [T]he apex of the Louisianan colonial project became centered on New Orleans after 1731 after another plot among the Bambara slaves was discovered and suppressed.

The administrative capital progressively became the ville above all other cities where “a sense of community among white urbanites” (p. 141) developed against the sources of disorder represented by Indians and Africans. [...]

---

Against generalizations on the “Creole” character of Louisiana, Chapter IX finally examines how the use of particular labels was contingent to racial and political understandings of what constituted a pays, and, then, later on, during the 1768 revolt against the new Spanish governor Ulloa, a nation. For the white population, “ethno-labels” (p. 468) were varied and referred to the origins of French speaking migrants whether these were Canadiens or Provençal or from another pays in continental France. [...] These attempts at differentiation found echoes later with the larger debates on racial degeneracy initiated by Cornelius De Pauw and Buffon in the metropole. [...] This tendency to define and exclude through different ethno-labels thus achieved its apex with “Creole” from the 1740s onward when both authors with a colonial background and enlightened metropolitan critics attached a “Creole” identity with “a person’s purity with blood”, and guarded against “the suspicion of métissage” (p. 455) [...]

Furthermore, this study goes beyond the encyclopedic exercise on secondary literature as it also presents detailed archival references in both local (American) and colonial (French) archival centers, the whole constituting the most erudite and synthetic study of a colonial city since Anne Pérotin-Dumon’s book on Pointe-à-Pitre and Basse-Terre, published in 2000. Carribean New Orleans remarkably concludes decades of research conducted by the author [...]. [T]his total social history of the city will help scholars to move away from the “creole singularity” paradigm and finally “draw comparisons between New Orleans and other places within the greater Caribbean, the French empire, and the Atlantic world.”

---

All text above by: Andy Cabot. “Was New Orleans Caribbean?” Books and Ideas (College de France). Published online 20 April 2020. At: booksnadideas.net/Was-New-Orleans-Caribbean. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Article refers to Cecile Vidal’s book Caribbean New Orleans: Empire, Race, and the Making of a Slave Society (2019).]

#colonial#imperial#ecology#abolition#caribbean new orleans#geographic imaginaries#tidalectics#ecologies#multispeciess

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Favorite History Books || Four Queens: The Provençal Sisters Who Ruled Europe by Nancy Goldstone ★★★☆☆

Marguerite, Eleanor, Sanchia, and Beatrice, as daughters of the count and countess of Provence, were steeped in the culture of the troubadours. It played as important a role in their upbringing as their lineage—indeed, it was their lineage. Their father, Raymond Berenger V, came from a long line of poets. His grandfather, Alfonso II, king of Aragon, was a highly respected troubadour whose verses were praised by Peire Vidal, the greatest poet of his day. Raymond Berenger V inherited his grandfather’s talent and passion for literature, and embraced the troubadour culture. He wrote verses and his castle was always open to visiting poets and minstrels. His was a very literary court.

... Despite the troubadours’ influence, by all accounts, the sisters’ mother, Beatrice of Savoy, countess of Provence, was very happy with her husband. Beatrice had married Raymond Berenger V in 1219, when he was fourteen and she twelve. Raymond Berenger V was the first count of Provence to actually live in Provence in more than a century—all his predecessors had preferred to stay in Aragon. During the summer months, when the weather was fine, he and Beatrice traveled around the county, meeting the barons and accepting their homage. The count was young and strong and athletic: he climbed the long eastern side of the Alps and visited villages unknown to his ancestors. In the winter months, he and Beatrice held court at their castle in Aix-en-Provence, or sometimes went south to Brignoles, which he had given to Beatrice as a wedding present.

Beatrice gave birth to twin sons in 1220, but they did not survive. Marguerite was born in 1221, when Beatrice was just fifteen years old. Eleanor came in 1223, followed by Sanchia in 1228, and finally the baby, Beatrice—four girls in ten years. The children inherited their mother’s loveliness. The renowned thirteenth century English chronicler Matthew Paris, an eyewitness with no great love of foreigners, called Beatrice of Savoy “a woman of remarkable beauty.” But she was also intelligent and capable. One of ten children, eight of whom were boys, Beatrice had learned at an early age to value strength and power. From her father, Thomas, a bellicose, domineering man who was happiest when making war on his neighbors, she had inherited a family ethos of solidarity at all cost. Thomas had ruled his large, unwieldy brood unconditionally and with an iron will. From their first breaths, Beatrice and all of her siblings had been taught to think first of the family’s ambitions, and these were many.

… During this period, Marguerite and Eleanor, only two years apart, were each other’s constant companion (Sanchia and Beatrice were too young to be interesting as playmates). Marguerite’s temperament resembled her mother’s. She was patient, capable, intelligent, and responsible, with a rigid and highly developed sense of fairness. Eleanor was more mercurial. As is often the case with second children, she both admired and competed with her accomplished older sister. The differences in their personalities were complementary, and the bonds these two established while growing up in Provence would survive into adulthood. Marguerite and Eleanor were always much closer to each other than they were to either Sanchia or Beatrice.

... Raymond Berenger V and his family were very much a part of this culture of studied affluence. They entertained often and lavishly. “Count Raymond was a lord of gentle lineage…a wise and courteous lord was he, and of noble state and virtuous, and in his time did honorable deeds, and to this court came all gentle persons of Provence and of France and of Catalonia, by reason of his courtesy and noble estate,” wrote the medieval chronicler Giovanni Villani. Among his many visitors were his wife’s brothers. The count kept a large retinue and rewarded his entourage with gifts of money and clothes. His daughters were dressed in gowns of rich red cloth, the sleeves long and tightly laced to their arms. Over this they might wear a jacket of green silk. White gloves protected their hands from the sun. Even as children, they had their hair, which they wore down around their shoulders (only married women put up their hair), dressed in jeweled combs.

#historyedit#litedit#margaret of provence#eleanor of provence#sanchia of provence#beatrice of provence#medieval#french history#european history#english history#german history#italian history#women's history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The influence of Chaucer is conspicuous in all our early literature; and, more recently, not only Pope and Dryden have been beholden to him, but, in the whole society of English writers, a large unacknowledged debt is easily traced. One is charmed with the opulence which feeds so many pensioners. But Chaucer is a huge borrower. Chaucer, it seems, drew continually, through Lydgat and Caxton, from Guido di Colonna, whose Latin romance of the Trojan war was in turn a compilation from Dares Phrygius, Ovid, and Statius. Then Petrarch, Boccaccio, and the Provençal poets, and his benefactors: the Romaunt of the Rose is only judicious translation from William of Lorris and John of Meung: Troilus and Creseide, from Lollius of Urbino: The Cock and the Fox, from the Lais of Marie: The House of Fame, from the French or Italian: and poor Gower he uses as if he were only a brick-kiln or stone-quarry, out of which to build his house. He steals by this apology,—that what he takes has no worth where he finds it, and the greatest where he leaves it. It has come to be practically a sort of rule in literature, that a man, having once shown himself capable of original writing, is entitled thenceforth to steal from the writings of others at discretion. Thought is the property of him who can entertain it; and of him who can adequately place it. A certain awkwardness marks the use of borrowed thoughts; but, as soon as we have learned what to do with them, they become our own.

—Emerson, “Shakespeare; or, The Poet” (my emphasis)

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The significance of Lucena’s Arte de axedrez goes far beyond its recreational value, however. The work is not only the first printed book on chess playing; it is also the earliest documentation of a radical alteration in the rules of the game. The change took place quite suddenly in the last quarter of the fifteenth century, transforming the way chess had been played for five hundred years. It is central to my argument that this revolutionary change centers dramatically on the only female piece on the chessboard, the Queen.

Chess historians differ in their determination of the date or country of origin of the “new chess.” The erudite H. J. R. Murray believed that the new moves were invented in Italy, and he cites as evidence Lucena’s prefatory statement that he acquired knowledge of the game on travels to Rome and France. More recent authorities believe the moves originated in either Spain or southern France. Richard Eales, for example, states that “it is hard to ignore the fact that almost all the reliable early evidence is linked with Spain or Portugal” (76). There was, in fact, in a general acknowledgment in the late Middle Ages of Spaniards’ expertise at chess, their skill at the game considered an indication of a high level of civility. In book 2 of Castiglione’s Il Cortegiano (The book of the courtier), the nobleman Federico Fregoso touts the benefits of chess as a pastime, calling it “a refined and ingenious recreation” (1140). Interestingly, especially in light of Pulgar’s comment on Fernando’s excessive dedication to the game, Don Federico also advises against devoting too much time to the pastime, lest it detract from more serious pursuits. Gaspar Pallavicino responds by praising the Spaniards for their seemingly effortless skill at the game: “there are to be found many Spaniards who excel at chess and at a number of other games, and yet do not study them too exhaustively or neglect other things,” to which Federico replies, “You may take it for granted . . . that they put in a great deal of study, but they conceal it” (140).

Chess scholars also disagree as to when exactly the new rules came into being. There is, however, unanimity in that they replaced the old game with remarkable swiftness. By 1510, the medieval game was obsolete in Spain, Italy, and probably France. By 1550, there is no evidence for its existence anywhere in Europe besides parts of Germany, Scandinavia, and Iceland (Eales, 76). Eales expresses the prevailing scholarly puzzlement over the rapidity with which modern chess replaced the Islamic form that had prevailed throughout the preceding millennium as follows: “The transition from medieval to modern was a complex and gradual process, in almost every area of life. Few historians or readers of history now expect to find specific events which tipped the scales from one age to the next. . . . So it is ironic that the game of chess experienced the only major change in its internal structure in over a thousand years of documented history through a single and dramatic shift in its rules of play at just about this time, the late fifteenth century” (71).

The drastic shift in rules centers dramatically on the Queen. In the old game, identified by Lucena as “old-style chess” [axedrez al viejo], the Queen was far weaker than the Rook or Knight and only slightly stronger than the Bishop (Murray, 776). In the new game, the Queen combines the moves of Rook and Bishop, to become by far the strongest piece on the board. This shift caused a radical alteration in the method and tempo of play. As Murray explains,

the initial stage in the Muslim or mediaeval game, which lasted until the superior forces came into contact, practically ceased to exist; the new Queen and Bishop could exert pressure upon the opponent’s forces in the first half-dozen moves, and could even, under certain circumstances, effect mate in the same period. The player no longer could reckon upon time to develop his forces in his own way; he was compelled to have regard to his opponent’s play from the very first. . . . Moreover, the possibility of converting the comparatively weak Pawn into a Queen of immense strength . . . [meant] it was no longer possible to regard the Pawns as useful only to clear a road by their sacrifice for the superior pieces. Thus the whole course of the game was quickened by the introduction of more powerful forces. (777)

It is important to note that whereas medieval players had been experimenting with extended moves for the Pawn and the Bishop since the thirteenth century, no known medieval precedent for the new Queen exists. The impression that the change in the Queen’s power made on European chess players and theorists is best seen in the names they gave the new game in France and Italy: “chess of the mad lady” [eschés de la dame enragée] and “mad chess” [scacchi alla rabiosa] (Eales, 72). Lucena calls it simply “chess of the lady” [axedrez de la dama].43 Chess authorities have proposed a variety of reasons for the sudden and drastic shift in the power of the Queen. These range from the “impact of the Renaissance” and the “urge toward individual independence,” to the invention of the printing press and the geographical discoveries of Columbus, to the creation of the idealized courtly lady by the Provençal troubadours (Cereceda, 24), to strong female role models such as Joan of Arc or Catherine Sforza (Eales, 76–77; Murray, 778–79).

It is perhaps a measure of the marginalization of Iberia in modern cultural history that no one has related the transformation of the Queen’s power in chess sometime between 1475 and 1496 with the unprecedented strengthening of royal authority simultaneously being effected by a historical queen who was decidedly a queen regnant and not a queen consort. Richard Eales, for example, states confidently that “It is certainly striking that the dominant piece in the new chess should be the queen, the only one with a female name, but no conceivable change in fifteenth-century history can explain it” (77).

It seems likely that the tastes and patronage of a queen who significantly shaped literature, art, and architecture in the final quarter of the fifteenth century also affected the recreational arts. Certainly, Isabel is a far more likely candidate for this distinction than the historically remote Joan of Arc (1412?–31) or the geographically displaced Catherine Sforza (1463–1509) proposed by Eales. Although there is no proof that Isabel’s real and symbolic power caused the transformation in the game itself, we can say that at the very least the recording of that dramatic change was a result of the impression that the absolutist power of this “new kind of queen” made on one aspiring letrado.

- Barbara F. Weissberger, Isabel Rules: Constructing Queenship, Wielding Power

#perioddramaedit#historyedit#women in history#isabella i of castile#chess#isabel tve#1x01#michelle jenner

229 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is Italian a similar language to French?

Anon, know you made a far more difficult question than you think it is. Lucky you this relates quite closely to the subject of my next exam, so I can consider it an exercise, lol.

The short answer is: they’re similar but not so much. The most notable differences one can notice are that Italian very seldom has words that not end in vowel, while French doesn’t utter vowel sounds even when they are written. Another difference is the pronunciation of sounds, but to show it I’d need to use IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) or to make audios (which is a big no for me), so I suggest, if you’re curious, to listen to the same song in the two languages (Disney songs are easy to confront, to say) to hear how different they sound.

The mid-long, slightly more technical answer is: both are neo-Latin languages, meaning they both descend from Latin so they’re bound to share similarities on a morphological and lexical point of view that are evident in themselves in written form. They also influenced each other in the centuries, so the relationship is thick enough.

But! The territory now known as France that was once conquered by Romans (in fact, the area that Romans held for the longest time) had its own population, the Gauls, with their own language which, in a certain measure, influenced the Latin spoken there. Then, during the barbaric invasions, the zone was invaded by the Frankish, a germanic population that brought there their own language, from the fusion of those influences, there emerged the Franco-Provençal and other forms, the d’oc and d’oil forms, the latter is the one from which currently spoken French evolved from.

And I promised myself I wasn’t going to write a long answer about the Italian language to add on it, but I did anyway, so here it is, under the cut.

Before that, I’d like to sum up what there’s down here, with a little more:

Italian was created from one of the many dialects Italy had, all of which derived from Latin, by Dante Alighieri (yes, the one I make fun of, but I’ve been studying him as part of my study course for 10+ years so I am allowed to do that from time to time) and then cultivated by people for centuries as a language made only for literature and not quite spoken until the Unity of Italy. During those centuries more influxes entered, but none prevalent to the base Dante made.

Now, to the long one:

Unlike French, Italian, although it is an evolution from Latin, had numerous influences from other languages, but none as strong as French had from Frankish. In fact, Italian is the evolution of the dialect of a singular area of Italy, the volgare fiorentino, aka the tongue spoken in Florence. Now, the discussion is incredibly complicated, so I’ll try to reduce it to the essential lines.

The volgari were the tongues spoken by everyone, at every level, that derived from Latin’s spoken tongue, which was different from the written for a number of phenomena that it’d be too long to explain here. Every zone of Italy, every city even, had its own, and many of them started to evolve a written tradition separated from the Latin one, which was still prevalent. The Sicilian court of Frederich II is known to be the first Italian volgare that produced high-level literature (although there are recent finds that show how this may not be entirely correct, but that calls for more research...).

Enter the Florentines Stilnovisti, a group of poets that started to use their own dialects instead of the Sicilian one, to write their love poetries. Dante Alighieri was one of them.

But Dante was above them. He was a genius (for how much I love to make fun of him, it’s undeniable how great he was at what he did) who first theorized the creation of a tongue that could be the same for all of Italy, the way Latin once was, a tongue which had the same dignity and expressive abilities of Latin, and then HE MADE IT.

The Comedìa (worldwide known as the Divine Comedy) is the result of his work, 80% of the Italian vocabulary can be already found in it, most of the syntax and morphological structures are already in there and he built the tongue from his mother dialect, the tongue spoken in Florence, but not only! He made up words, he used Latin and Franco-Provençal and other Italian dialects and much much more to create a new tongue that became what we now speak!

And yes, then there came Petrarca that set a higher standard for poetry by “cleaning up” the mixed language of the Comedìa, and then Boccaccio became a baseline for prose (the three of them are known as the Three Crowns of Italian language) but the groundwork was made by Dante Alighieri.

And then, centuries later, there was Alessandro Manzoni (as a matter of fact, there would be a few passages in the middle, but this is already long as it is, so I’ll skip to here). By that time, Italian language was, just like the country, not a reality but more of a solid idea (I made some time ago a series of posts about Italian History, in case you want to see what the situation was). It was a language for literature only, with all the heaviness of being old and not quite up to date as it a spoken language was supposed to be. Manzoni had the bright idea to take this novel he was writing and modify the tongue according to how real people in his time’s Florence actually spoke. And it worked marvels! The tongue made by Dante was renewed with the influx of the practical evolutions the people did without even noticing they made!

When the Unity of Italy came shortly after, the tongue Manzoni used was basically adopted by the whole country, the novel I Promessi Sposi became a school book that was functional to teach the language to all the people who spoke only their own dialects and it’s still an essential part of Italian kids’ education today.

#question answered#languages#history#I'll have you know I wrote it in less than 1 hour so if there's something weird forgive me#anyone who wants to add more about the french language is welcome to do so

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay i want to point out something about ninth house that probably doesn't make any sense but i need to say it anyway.

so alex is dante and darlington is virgil, right? we all know those characters are from the divine comedy.

but you know what also dante wrote? "dolce stil novo" sonnets. it's a literature movement (that has similarities with provençal/french poetry) where the poets are usually knights (intended as second-born sons) express their impossible love to their loved ladies, but since their love is well...impossible (for class reasons and often because those ladies are already married but this doesn't matter here) they express their devotion through servitude to the lady.

i'm probably reaching at straws but darlington seeing himself as a knight and wanting to serve alex at all costs remembered me this.

#ninth house#alex stern#darlington#let's also pretend that the ladies weren't a metaphor for feuds shhhh#texts#*mine

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In my grandmother's school, in Marseille, in the early 20th century, the girls who were caught speaking Provençal language had to clean the toilets. And the repeat offenders were forced to lick them "because they had shit in their mouth"!

My grandmother did not pass Provençal on to her children."

Philippe Blanchet, linguist. L'Express, 5th April 2016.

And this is how languages are killed.

France's policies known as the Great Linguistic Genocide are referred to as "la Vergonha" ("the Shame" in Occitan) because of the feeling they forced onto its speakers. The people whose mother tongue was the local language (Occitan, Breton, Basque, Catalan, Alsatian, Arpitan, Corsican, etc) were forced to feel so ashamed that they hid their language even from their children. Many, even nowadays, think that their "patois" (a word that means "badly spoken mix of languages") doesn't have a written form and doesn't allow complex thoughts. Not aware that some of these languages, such as the case of Occitan (of which Provençal is a variant) have one of the oldest and richest literature heritages in all of Europe. Cultures that the State of France murders a bit more everyday.

#occitan#provençal#language imperialism#languages#occitania#stateless nations#imperialism#linguistics#langblr#french#france#💬

547 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alfonso VI of León & Urraca of Zamora

The two siblings were children of Fernando I "El Magno" and Sancha of León. After the death of their father, Alfonso inherited the Kingdom of León and Urraca the city of Zamora, and the Infantazgo, that is, "the patronage and income of all the monasteries belonging to the royal patrimony" on the condition that she remained unmarried. The figure of doña Urraca is one of the most powerful of medieval Iberia. She is the pious and devout daughter, sister, and co-ruler recorded in the Latin historical chronicles, as well as the passionate and cruel temptress in vernacular chronicles and in the ballad tradition. Undoubtedly the wildest rumor surrounding Urraca is that of an incestuous relationship and even marriage with her own brother. Urraca and Alfonso's mutual admiration was well known in their day and alluded to in contemporary documents. Alfonso governed jointly with Urraca: "Adefonsus Serenissimus rex, una cum consensu sororis mee Urraka". Alfonso refers to her with the conventional but certainly true formulation "dilectissima adque amantissima sóror mea".

The earliest known written allegation of Urraca and Alfonso's incest appears in a work by the mid twelfth century Granadine historiographer Abu Bakr ibn al-Sayrafi. The second known early reference to Urraca's incest with Alfonso appears in Fray Juan Gil de Zamora's historical tract De praeconibus Hispaniae (c. 1278-1282). As in the Arabic version, Fray Juan alleges that the incestuous acts took place following the siege of Zamora and their brother Sancho's murder. Whatever motives Ibn al-Sayrafi and Fray Juan had in reporting the allegation, their testimony affirms the existence of early peninsula-wide epic poems containing narratives of an incestuous marriage between Urraca and her brother Alfonso VI. The original source of this report is impossible to ascertain. Lévi Provençal and Menéndez Pidal considered the incest accusation plausible. Catalán agrees, noting that incest was part of eleventh century reality. Alfonso VI's biographer, Bernard F. Reilly, doubts the incest charge. He sees "nothing innately surprising or sinister" in Urraca's sisterly preference for Alfonso and finds neither the Muslim source nor Gil de Zamora to be "convincing".

Urraca was a woman of status and power in a world of ruthless dynastic imperatives. Alfonso was what we would now call a warlord, constantly on the offensive, leading his nomadic court, intent on securing borders, keeping rebellious nobles under control, and fighting to reconquer al-Andalus. During their brother's long reign (1065-1109), both Urraca and Elvira exercised power equivalent to or greater than all of Alfonso's queens. Like their mother Sancha, Urraca and Elvira, had they married, would have been transmitters of lineage. From this point of view, the brother-sister marriage would have been a possible strategy to consolidate inheritance. With all other heirs defeated, the brother-sister liaison would have unified the previously dispersed paternal territories. Urraca did not need a royal marriage to exert influence: her privileged position as a member of the royal family and daughter of Fernando and Sancha and her own ability to use that position guaranteed her more prestige and authority than any matrimonial alliance. The Chronica Seminensis enthusiastically describes Urraca's fervent love for Alfonso, her maternal care for him, and her rejection of husbands and carnal relationships:

Indeed, from childhood on, Urraca loved Allonso with a heartfelt fraternal love, more than the others. Since she was older, she raised him as a mother, and dressed him. She was distinguished by her wise counsel and probity. We affirm this not from rumors, but from our own experience, in that she disdained carnal relationships and the fleeting adornments of matrimony.

Subsequent Latin chronicles follow the Seminensis in characterizing the nature of Urraca's and Alfonso's relationship as that of mother and son.

Because Urraca was very noble in her ways, Alfonso was commended to her by their mother and father, for she loved him more than the other children. At the time that King Alfonso conquered the Kingdom of León, he obeyed his sister Urraca as he would a mother.

The evolution of the scandalous Urraca persona was part of the jongleuresque anti-Alfonso discourse. Hostility to Alfonso, explicit in Islamic historiography and exemplified in Ibn al-Sayrafi's accusation, is summarized in the famous verse referring to him in the Poema del Mio Cid: " iDios qué buen vasallo / si oviesse buen señor!". In the epics of the Castilian juglares, in the chronicles which rephrased them, and in popular balladry, Urraca was the narrative scapegoat and sexual libel was the weapon of choice. The open and intense personal-political complicity between the two was translated into intense sexual complicity. The specific incest charge was certainly a serious attack, breaching, as it does, a nearly universal taboo, but in the end its narrative buttress was fragile. It never became as widely disseminated as the accusations of Urraca's fratricide/regicide, prostitution, and promiscuity. The exact nature of the relationship between Urraca and Alfonso, whether maternal, fraternal, carnal or platonic, can never be definitively reconstructed. Historical reality, as always, slips through our fingers.

Source:

Doña Urraca and her Brother Alfonso VI: Incest as Politics by Teresa Catarella. Published by La corónica: A Journal of Medieval Hispanic Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, Volume 35, Number 2, Spring 2007, pp. 39-67 (Article)

#Urraca of Zamora#Alfonso VI of León#Urraca de Zamora#Alfonso VI de León#Women in history#Men in history#Spanish history#Couples in history

92 notes

·

View notes