#our endless war

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Phil Bozeman of Whitechapel

#Phil Bozeman#Whitechapel#Whitechapel Band#Deathcore#Death Metal#Somatic Defilement#This Is Exile#A New Era Of Corruption#Our Endless War#Mark Of The Blade#The Valley#Kin#A Visceral Retch#Band Post#Hymns Of Dissonance

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

#whitechapel#deathcore#the somatic defilement#this is exile#a new era of corruption#our endless war#mark of the blade#the valley#kin#metal#metal blog

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gallery: Whitechapel @ Doug Mitchell Thunderbird Sports Centre - Vancouver, BC Date: November 25, 2023 Photographed by: Danielle Costelo

#PRmusic#PRphoto#Danielle Costelo#Music#live music#Vancouver#yvr#Doug Mitchell Thunderbird Sports Centre#Whitechapel#UBC#Thunderbird#Phil Bozeman#Ben Savage#Gabe Crisp#Alex Wade#Zach Householder#Mark of the Blade#The Valley#Our Endless War#This is Exile#A New Era of Corruption#The Somatic Defilement#Metal Blade Records#Metal Blade#The Saw Is the Law#Let Me Burn#concert#concert photography#concert photos#gig

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐥𝐞𝐬𝐬 𝐰𝐚𝐫 - 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐞𝐥

album of the day: march 2, 2025

0 notes

Text

WHITECHAPEL 'Our Endless War (Bonus Track Version)'

♫ WHITECHAPEL new album 'Our Endless War (Bonus Track Version)' out NOW via Metal Blade Records. Check it out now at: www.InfraredMAG.com #NewMusic #NewMusicFriday #Whitechapel #OurEndlessWar #BonusTrackVersion #MetalBladeRecords

WHITECHAPEL Our Endless War (Bonus Track Version) April 29, 2014 Metal Blade Records (more…) “”

View On WordPress

#Bonus Track Version#Earsplit PR#Metal Blade Records#Our Endless War#Our Endless War (Bonus Track Version)#Whitechapel

0 notes

Text

the legend of ron speirs

roland aimed his thompson gun he didn't say a word...

#band of brothers#bobedit#hbo war#hbowaredit#ron speirs#ronald speirs#idk how people tag him lol#kbsd.amv#kbsd.hbow#ok director's commentary:#another amv that's been finished and sitting in my drafts for a month bc it was waiting to be posted after a deadline lmao#this was my entry for our server's monthly fanwork challenge with the prompt myth/legend (h/t kira)#obv my mind immediately went to speirs#i LOVE warren zevon so when i was brainstorming this video and trying to think of what music to use#and what feeling i wanted to evoke i knew it HAD to be him and well. thompson gunner? come on…#truly could only be more perfect if speirs’ name was roland not ronald hahaha#anyway. i was less concerned with following the /exact/ narrative of this song#and more with using its central character—a legendary‚ immortal gunner driven by endless war—#as a vehicle for the sound bites i wanted to weave about speirs’ mythic status in easy company#(i even downloaded a karaoke version so i could drop some lyrics out to make room for dialogue lol)#i also wanted to highlight how the fear surrounding the rumors slowly shifts to respect#i really tried to capture a specific rhythm and feeling with this one#and i'm SO so proud of how it turned out <3#i was going to make a companion video to a different zevon song that kind of dismantled the legend?#and showed the more human/scared side of speirs#but i didn't quite have the footage i needed i'm going to fold it into a larger gen video idea i have...we'll see#ANYWAY. SPEIRS SUNDAY

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

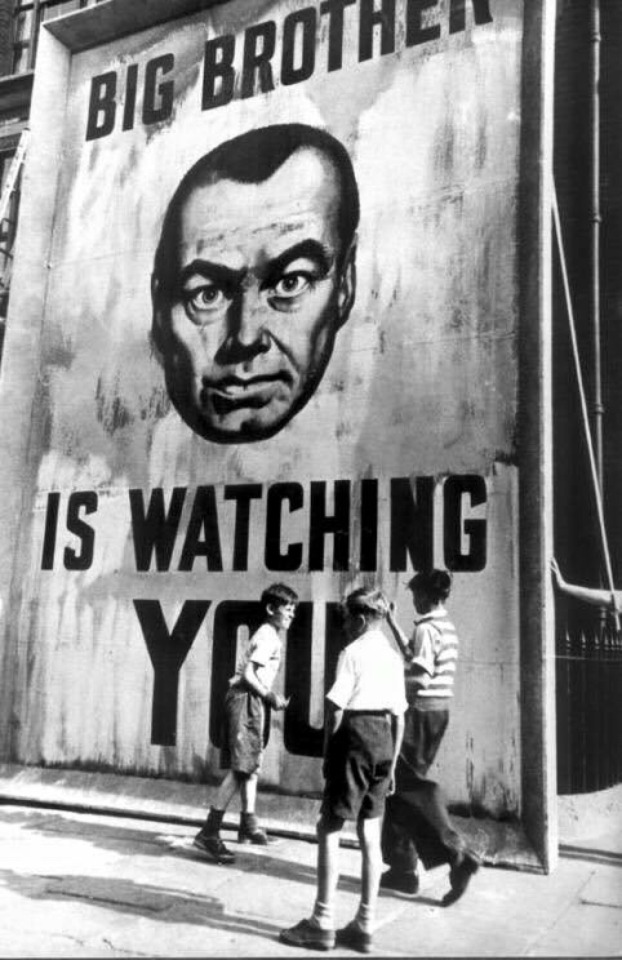

2024

#1984#george orwell#big brother#richard burton#dystopia#our future#authoritarianism#movie adaptation#endless war#thought police#war is peace#cult of personality#ministry of truth#propaganda#winston smith#animal farm#doublethink#thought crime#brave new world#fuck maga#maga morons#MAGA#totalitarianism#ingsoc#ministry of love#big brother is watching you#donald trump

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

Save what we love. #RenewTheAcolyte

Renew it Disney you cowards.

youtube

#oshamir#the acolyte#oshmir#the acolyte tv series#star wars series#the acolyte spoilers#the acolyte cancellation#save the acolyte#renew the acolyte#the acolyte discussion#star wars#qimir#osha aniseya#osha x qimir#not fighting what we hate#saving what we love#renew it you cowards#give us back our story#stop listening to the ones who hate it#wit and folly#wit&folly#wit and folly youtube#disney#disney lucasfilm#tv series cancellation#the acolyte fandom#oshamir fandom#the coven💜#I will scream about this show for as long as I can#bless Wit&Folly for speaking our truth and giving us another voice in the endless dark of this just relentless hatred and backlash

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

[捌] We the people have spoken against our endless war

I need whoever happens to read this dumb journal entry to realize something: Individuals can be stupid and to hold them up in any sort of pedestal is going to, more often than not, do more harm than good, both for them and to yourself. ---- And this isn't just because the default "Ignore celebrities" tool that I've grown more and more accustomed to deploying now that I'm on my mid-to-late 30's, but maybe just realize that artists, celebrities, influencers, etc are also human, and we humans can be really dumb. ---- Sure, humans being... well, human (in this specific case, meaning "kinda dumb"), can also be charming and make you go "Oh they just like me frfr!" and like that's fine. It's fine: You can still stan and/or enjoy whoever you like, just never become so incurious that you take what anybody recognizable says as gospel. ---- That's the whole idea behind the phrase "stay woke" that african-americans have been saying since the 1930's: Stay alert of racial-prejudice + racial discrimination. "Alert" being the opposite of incurious and ignorant. Be aware. Be awake. ---- Sure, I know that the term (mostly the word woke, in this case) has come to mean something else entirely in the 2010's and 2020's because language changes all the time, and I know that change can feel like it sucks, but it doesn't have to. Humans are all about being stubborn bastards who refuse to remain in obsolescence. ---- When something sucks, we don't just go "it is what it is". Fuck that shit. We work hard to make it stop sucking. Or to give way to people so that they can make it better. Anyway, keep yourselves safe out there and read ya' later!

#diary#daily life of an old shithead#whitechapel#whitechapel reference#deathcore? in this blog? WOW#“our endless war” is such a weird album#like it rocks#legit has some of the better songs whitechapel has written#but it also feels like it's at war with itself theme-wise#also probably the best 10 minutes of any whitechapel album#Rise->Our Endless War->The Saw is the Law? All rippers.#people being people#dumb#but also getting past that#dealing with life#and other people#be kind#be smart#learn to get over past shit you couldn't do before#on learning

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

hateshinai yozora

endless night sky...dusty spiders..machina weaving your dreams inside her. ethereal webs which grid the astral, spinning in a waltz, connected through lux, catching prey, in her Ether Netz.

#because if machina is an AI spider.....we are just bugs on this ether net .#poem#a bad one#i think mcr5 should focus on noise that isnt sound based#our AI foe....#killjoys to invisible soldiers...#endless night sky#the noise that is louder than silence that we all create..#there's silence...then there's.....a silence....with a hint of something wrong in the air.#its being so connected through the internet that we forget how to connect in real life.#anyways#frequencies? i mean if noise jam became an album live song it would fit my theory !#how frequencies can make one do things..words like..WAR...and...EXTERMINATION

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phil Bozeman

•

•

📸 Credits: Slashleyphotography

#Phil Bozeman#Whitechapel#Somatic Defilement#This Is Exile#A New Era Of Corruption#Our Endless War#Mark Of The Blade#The Valley#Kin#Deathcore

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

#deathcore#deathcore blog#whitechapel#phil bozeman#the somatic defilement#our endless war#this is exile#mark of the blade#oceano#a new era of corruption#job for a cowboy#angelmaker#shadow of intent#enterprise earth#to the grave#thy art is murder#carnifex

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because of You, We Still Have Hope 💙🙏

There are moments when it feels like the world has moved on, like everything we’ve lost is just another story that people scroll past. But every now and then, kindness reminds us that we are not forgotten.

Today, we’ve reached $1,580 out of $90,000, and while it’s still a long way from what we need, it’s proof that people still care. That hope still exists.

I never thought I would be in a position where I had to ask for help just to survive. 25 members of my family are gone. Our home has been reduced to rubble. Every day is a fight—not just for survival, but to hold onto the smallest piece of dignity.

💔 No stability, no safety, no certainty. 💔 Evacuations, grief, and endless struggles. 💔 Dreams on hold, because survival comes first.

But through all of this, your kindness gives me strength.

Even if you can’t donate, just sharing this post helps us reach more people who might be able to. Your support—no matter how small—makes all the difference.

🙏 If this post has reached you unexpectedly, I truly apologize. I promise I wouldn’t be asking if we weren’t in desperate need. If this isn’t for you, please feel free to ignore it. No hard feelings at all.

From the bottom of my heart, thank you. Your kindness is the only reason we still have hope. ❤️

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

URGENT!!!Help Abdul Salam Al-Anqar and his family get through this war in Gaza!!!

(URGENT) THEY ARE AT €3,445 OUT OF €50,000 GOAL

I was asked by @nader5555 to make this, if u cannot donate please please share this post. Copy pasted from a message i was sent:

"Only a Few Hours Left Before We Enter Our First Year of War, Genocide, Starvation, and Displacement A Final Plea from the Heart of Hell: Save Us Before Hope Dies 💔🔥 I am Abdel Salam, and I have nothing left but words written by a trembling hand ✍️. The war has not only destroyed our lives; it has taken everything from us. Our home, which was once our refuge, is now a pile of rubble 🏚️.

My car, my only source of livelihood, was destroyed in a sudden strike 🚗, and the work that sustained us is now a distant memory 💼. Today, I live in an endless nightmare. Under a sun that burns everything in its path 🌞🔥, my family and I sit in a worn-out tent, a tent that shields us neither from the summer heat nor the winter cold ❄️. Insects 🦟 invade the place, diseases consume our bodies ��, and my younger siblings cry from hunger and thirst 🍞💧. We have no clean water or a crumb of bread to ease our hunger. Each passing day deepens the weight of this hell we live in.

My Daughter Eman is Dying from Malnutrition 😨 My daughter Eman suffers from malnutrition; I have nothing to feed or treat her with. The deterioration of her health is killing me slowly. Every glance in her eyes, every pain she endures, crushes my heart 💔. How can I explain to her that what was once our hope has now turned into nothing but a mirage? The Night Only Adds to Our Pain 🌙 The night does not bring us rest; it only adds to our pain. We sleep on hard ground, feeling the cold in every bone of our bodies 🥶, with nothing but pieces of cardboard 📦 to cover us. My wife Aya cries in silence 🥺 as she watches our daughter’s future fade before her eyes. My mother Eman suffers from illness and needs urgent medical care 🩺💊.

My Father Ahmed is Sick with Cancer and Needs Emergency Treatment My father Ahmed, who is sick with cancer, needs emergency treatment outside Gaza, and the cost of his treatment is at least $10,000, not including accommodation. As he suffers from severe pain, I cannot provide the treatment he needs due to our dire situation.

My Siblings Are in Constant Suffering ⚰️ My brother Omar was unable to continue his studies due to the situation. My brother Nader could not take his high school exams, and my younger brother Mohammad suffers from brittle bones and needs treatment we cannot afford. Every day we live brings us one step closer to the end. Death surrounds us from every side: if not from hunger 🍽️, then from illness 🦠. And if not from illness, then from the despair that devours our souls. Where is Humanity? Where is the World? 🌍💔 We want to leave the devastated Gaza Strip to escape the machinery of destruction and killing and the severity of hunger and poverty. The cost of travel for each person is $5,000, and we are a family of seven members, bringing the total cost to $35,000.

Where are the compassionate hearts? Are you waiting for us to disappear into the depths of this suffering? Are you waiting until death takes us before you act? We are drowning, and we don’t have enough strength to scream for help 🆘. Will you let this cry go unanswered? 😭 Your donation today is our last thread of hope. With the little support I received, I was able to buy a simple phone 📱 to reach out to you. But the bitter truth is that what I and my family need is much greater. We are not asking for much; just enough to save our lives from this hell 🔥. Every donation, no matter how small, could be the difference between life and death for us 👐. Don’t Let Us Disappear in the Darkness of Suffering 🌑 Don’t let our story end here. Be the light that guides us to salvation 🕯️���.

With every tear, with every pain, I write this final plea to you, Abdel Salam."

taglist

@butchniqabi @xinakwans

@batekush

@appsa

@nerdyqueerr

@butchsunsetshimmer

@biconicfinn @stopmotionguy

@t4tvampireisms

@strangeauthor

@bryoria @shesnake

@legallybrunettedotcom

@lautakwah @sovietunion

@neechees @evillesbianvillain @antibioware

@akajustmerry @dizzymoods

@ree-duh @neptunerings

@explosionshark

@heritageposts

@ibtisams

@schoolteacher

#my art#**mine#free palestine#free gaza#gfm#palestine gfm#b00st#help#mutual 4id#donation link#boost#signal boost#art#artists on tumblr#digital artist#digital art#artblr#save palestine#palestine#all eyes on palestine#free plaestine#gaza#from river to sea palestine will be free#artists#please help#important#edit: changing photos per nader5555's request

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

All the takes are correct and yet they also miss the point. Yes, it was insane for the Democrats to think they could win by running a soulless candidate, without a shred of progressive policy vision, pursuing endorsements from neocon war-hawks everybody hates, while arming and funding a genocide, and belittling and crushing those who have enough morality to protest it. It is enraging that the Democrats are so smug and blind to this. But these are all just symptoms. The deeper reality is that liberalism has failed, liberalism is dead, and people urgently need to wake up to this fact and respond accordingly. It is a defunct ideology that cannot offer any meaningful solutions to our social and ecological crises and it must be abandoned. Democrats have proven over and over again that they cannot accept even basic steps like public healthcare, affordable housing, and a public job guarantee - things that would dramatically improve the material, social and political conditions of the working classes. And they cannot accept a public finance strategy that would steer production away from fossil fuels and toward green transition to give us a shot at a liveable future. Why? Because these things run against the objectives of capital accumulation. And for liberals capital is sacrosanct. They will do whatever it takes to ensure elite accumulation, it is their only consistent commitment. At home, they suppress and demonize progressive and socialist tendencies. Abroad, they engage in endless wars and violence to suppress input prices in the global South and prevent any possibility of sovereign economic development. The Democrats have done all this purposefully and knowingly, for my whole life, not as some kind of "mistake" but in full consciousness that it is in the interests of capital. And because liberalism cannot address our crises, and because it crushes socialist alternatives, it inevitably paves the way for right-wing populism. They know this pattern, and yet they risk it every time - this election being only the most recent example. They did it in 2016, when they actively crushed the Sanders campaign and sent Trump to the White House. They do it because ultimately they (and I mean the liberal ruling class here) don't really mind if fascists take power, so long as the latter too ensure the conditions for capital accumulation. They 100% prefer this to the possibility of a socialist alternative. So, progressives have to face reality. The dream of "converting" the Democratic party is dead. This is now a fact and it must be accepted. The only option is to build a mass-based movement that can reclaim the working classes and mobilize a political vehicle that can integrate disparate progressive struggles into a unified and formidable political force and achieve substantive transformation. This will take real work, actual organizing, but it must be done and that process must begin now.

Jason Hickel

8K notes

·

View notes