#or from cholera

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I...What.

Why the fuck the 1830s? "But without the racists" Okaaaaaaaaay, even if we set aside all the other bigotries alive and well, that's still a very simplified way of looking at slavery, white supremacy, and colonialism.

Also if the song isn't about those topics, that I'm sure she doesn't give a fuck about, why bring up racism at all? It just sounds like the songwriter was like "oh right the 1830s had slavery, let's just rhyme this with racists aaaaannnd perfect." Which again, whyyyyy the 1830s?

One thing is for sure, I'm still side eyeing my cousin who ADORES Taylor Swift and thinks her music is the best thing ever.

i can't believe this is real this sounds like it was pulled directly from the "i wanna have straight sex" tiktok

#lix rambles#i feel like context would make this lyric worse#even as a rich white woman i don't see why you'd want to go to the 1830s#unless you WANT to die due to complications from childbirth#or from cholera#or smallpox#or polio#VACCINES WERE STILL IN THEIR INFANCY FOR FUCKS SAKE#also again childbirth got to pump out an heir

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

"But the two of us are performing admirably!"

barebones lineart + effectless version+the continuing bit of hungarian hale

#ghosts art#SAYER podcast#SAYER#jacob hale#me when i end up rendering a randomass idea i got on a walk to school instead of something ive been wanting to work on for days#i considered putting the line ''I'm barely standing broken toy'' from cholera by tardigrade inferno as the caption but it didnt feel right#w/ the version that had SAYER talking HAHWKJA#ill be reserving cholera for later use#<-insane sentence out of context#also fun little detail! the blood on his lips is smeared a little. whos been kissing him .

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy new year everyone! We just had our Christmas yesterday (don't worry about it) and I need to show you what majesty @beauxoiseaux has handcrafted this time.

Also I have been using @xosailormars's usagi bun tutorial for like a decade now and it never steers me wrong

#the artemis was a gift from myself to myself#i will show you my artemis collection one of these days#there are many#american girl doll#sailor moon#doll cosplay#she's leaning on the armoire because my kirsten larson cannot stand on her own#the cholera got her!!#anyway now i need to get her to make 10 more senshi fuku + tuxedo mask

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’m probably going to, finally, at long last, finish the neapolitan quartet/my brilliant friend series today. i don’t have that much more left, but i am considering slowing down to one page a day so i can drag this out. i’ve fallen so deeply in love with these girls and idk what i’m gonna do without them 😭

#hey elena ferrante dissolve this boundary 🖕#i’m trying to figure out what i’m gonna read next but it’s gonna largely depend on what the library has readily available#because im going out of town on saturday#i’m considering:#love in the time of cholera by marquez#despair by nabokov#dona flor and her two husbands by jorge amado#2666 by roberto bolaño#or#the idiot by elif batuman#(the latter was recommended to me by the same friend who recommend my brilliant friend so it’s a very serious contender rn)#pretty much every time i place a hold on a book they have to transfer it from the main branch downtown to my branch#and i’ll just read something short off my own bookshelf in the meantime#but i’ve exhausted every slim volume i own#so i’ll need to find an excuse to leave work early sometime this week so i can get to the library downtown#OR!#i just never finish the neapolitan quartet and lenu and lila live with me forever#personal

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

imagine being less competent than the Fyre Fest guy

#gaza#rafah#free palestine#fyre fest#fyre fest was a mess but no one died of cholera so it is coming out ahead#quote is from NBC article

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

i often like to think that the bad oyster grantaire ate today gave him cholera. it's not remotely thematically compelling but boy is it funny to me

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

According to the popular theory of “epidemiological transitions,” first articulated by the Egyptian scholar Abdel Omran, the demise of infectious diseases in wealthy societies was an inevitable result of economic development. As societies prospered, their disease profile shifted. Instead of being plagued by contagion, they suffered primarily from slow-moving, chronic, noncommunicable conditions, like heart disease and cancer.

I confess to once being a true believer in this theory. I knew from visiting places like the south Mumbai ghetto where my father had grown up that societies that suffered significant burdens of infectious diseases were indeed crowded, unsanitary, and impoverished. We stayed in south Mumbai every summer, crammed with relatives into two-room flats in a dilapidated tenement building. Like the hundreds of other residents, we flung our waste into the courtyard, carried our own water in aging plastic buckets to shared latrines, and fitted two-foot boards over the thresholds to keep out the rats. There – as in other crowded, waste-ridde, poorly plumbed societies – infection was a constant reality.

But then, thanks to the same conditions that brought cholera to the shores of New York City, Paris, and London in the nineteenth century, writ large, the microbes staged their comeback. Development in once remote habitats introduced new pathogens into human populations. A rapidly changing global economy resulted in faster modes of international travel, offering these pathogens new opportunities to spread. Urbanization and the growth of slums and factory farms sparked epidemics. Like cholera, which benefited from the Industrial Revolution, cholera's children started to benefit from its hangover: a changing climate, thanks to the excess carbon in the atmosphere unleashed by centuries of burning fossil fuels.

The first new infectious disease that struck the prosperous West and disrupted the notion of a “postinfection” era, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), appeared in the early 1980s. Although no one knew where it came from or how to treat it, many commentators exuded certainty that it was only a matter of time before medicine would vanquish the upstart virus. Drugs would cure it, vaccines would banish it. Public debate revolved around how to get the medical establishment to move quickly, not about the dire biological threat that HIV posed. In fact, early nomenclature seemed to negate the idea that HIV was an infectious disease at all. Some commentators, unwilling to accept the contagious nature of the virus (and willing to indulge in homophobic scapegoating) declared it a “gay cancer” instead.

And then other infectious pathogens arrived, similarly impervious to the prevention strategies and containment measures we'd long taken for granted. Besides HIV, there was West Nile virus, SARS, Ebola, and new kinds of avian influenzas that could infect humans. Newly rejuvenated microbes learned to circumvent the medications we'd used to hold them in check: drug-resistant tuberculosis, resurgent malaria, and cholera itself. All told, between 1940 and 2004, more than three hundred infectious diseases either newly emerged or reemerged in places and in populations that had never seen them before. The barrage was such that the Columbia University virologist Stephen Morse admits to having considered the possibility that these strange new creatures hailed from outer space: veritable Andromeda strains, raining down upon us from the heavens.

By 2008, a leading medical journal acknowledged what had become obvious to many: the demise of infectious diseases in developed socieites had been “greatly exaggerated”. Infectious pathogens had returned, and not only in the neglected, impoverished corners of the world but also in the most advanced cities and their prosperous suburbs. In 2008, disease experts marked the spot where each new pathogen emerged on a world map, using red points. Crimson splashed across a band from 30-60° north of the equator to 30-40° south. The entire heart of the global economy was swathed in red: northeastern United States, western Europe, Japan, and southeastern Australia. Economic development provided no panacea against contagion: Omran was wrong.

— Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond (Sonia Shah)

#book quotes#sonia shah#pandemic: tracking contagions from cholera to ebola and beyond#history#medical history#medicine#epidemiology#economics#wealth#poverty#academia#science#epidemiological transition#india#mumbai#abdel r. omran#stephen morse#hiv#west nile virus#sars#ebola

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#personally I’m getting strong vibes from patience#but if the ghost of Christmas future was like#a little less grim I’d say flower honestly#and yes some ghosts are missing… that’s for a reason I promise#trust#cbs ghosts#ghosts cbs#hetty woodstone#hetty ghosts#trevor lefkowitz#ghosts flower#flower montero#issac higgintoot#thorfinn#sassapis#pete ghosts#alberta#alberta haynes#thor odinson#patience ghosts#nancy#cholera ghost#there’s too many tags 😭

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

not to be an annoying crotchety back in my day boomer, but American Girl dolls really were better when I was a kid, right? like, they used to have actual stories and stuff. now every American Girl doll is like “Her name is Generic Blue-Eyed Straight-Blonde-Hair Girl #128838. She comes from a painfully ordinary, modern-day upper-middle-class household, she has exactly two (2) Conventionally Feminine Girl Hobbies, and she has experienced zero real problems ever in her life”

#not that any of this affects me in any way but I’m still unreasonably annoyed by it#I thought the historical stories were so cool as a kid!#they were all so unique and dramatic#now the brand seems to have moved away from all of that and towards the most vapid nonsense imaginable#these girls used to go through. like. the great depression and cholera and stuff#and now the plotlines are like “I’m lactose intolerant” or#or “I have a horse”#which I found really boring even as a child#idk maybe I was just a weird macabre kid but I would rather read about WWII than yet another story#about a generic well-off suburban girl having a minor problem

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's so cold but I don't wanna get properly dressed bc im scared of running out of my good clothes... water please come back I miss u......

god if ur hearing this CLEAN WATER. FROM THE PIPES. IN MANAGEABLE QUANTITIES. 🫷😳🫸

#my neighborhood didnt flood and we still have electricity so were ok#its just the water thats still cut off#we were able to buy drinking water and the whole building collected the rain from these past few days#but its still such a pain in the ass#oh you wanna take a shit? yeah sure just remember to go up to the 21st fucking floor and bring down a bucket of water so you can flush#you wanna take a shower? go put the kettle on and sit in this tub (as in the plastic recipient you use for laundry and not a bathtub)#like we were legitimately so fucking lucky and privileged to like. still have a home and our lives and all dont get me wrong#but i think i still have the fucking right to be pissed#exploding every billionaire climate change denier and complicit politician's houses a thousand times with my mind#the worst thing is that since my anxiety is through the roof ive been picking my skin a lot more.#you know. in the worst time possible to have dermatilomania#WHEN WE DONT HAVE FUCKING CLEAN WATER TO WASH OUR BODIES OR CLOTHES WITH AND THE HOSPITALS THAT HAVENT BEEN FLOODED ARE FULL#WITH PPL WITH DENGUE AND RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS AND IDK FUCKING LEPTOSPIROSIS AND CHOLERA PROBABLY#hell world#opost#why did i even write this in english#this is abt the rio grande do sul floods#brazil mentioned#latam#rio grande do sul#i just hope this pisses other ppl off enough to motivate them to take radical action i guess#........... 😮💨#vent#ok to rb

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

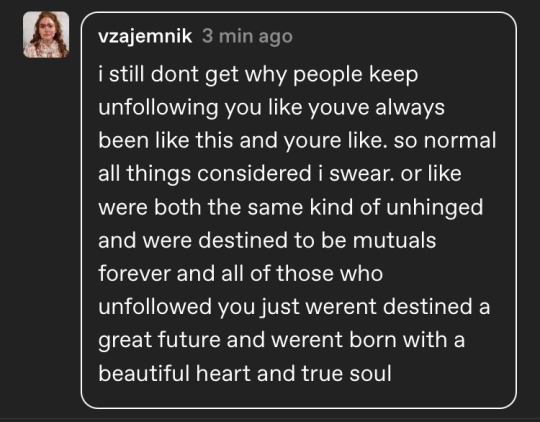

@vzajemnik

#im sorry but i need to save these in like a gilded cage somewhere or like pin them to my monitor as post it notes#dr juvenal arbino from love in the time of cholera voice: ONLY GOD KNOWS HOW MUCH I LOVE YOU!!!!!!!!!!!#THE FEET THINGBFGFGVB.F.G..... HELP ME..i truly cannot believe that feet and rpf are gonna be my legacy of all things in this world .#the youtuber thing makes me sooooooooooooooooooo happy omg that actually is like the main thing that makes me feel like all this#(the misery and insanity i experience on this blog) is worth it like thats truly beautiful on such a profound level THATS AWESOME...#i love you soooooooo bad and i dont rly get it either tbh like i never in my life imagined that my little loser blog would inspire#any kind of controversy abt anything but i guess this is tumblr after all . also we need to go celebrate our platinum wedding anniversary#Immediately.#❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

OHHHHHH YEAH IT CAN, BABEYYY

and that’s not even mentioning the other carcinogens that go into casket-making, varnishes on coffins, etc. etc.

embalmed bodies decay. caskets decay, no matter what they are made of--yes, metal too. ALL of EVERYTHING that made up what you put in the ground during the funeral becomes... well, we’ll call that mixture of “grandma and everything she was buried in” something like “compost.” (funfact! the actual term of all of... that is called “necroleachate!”)

just runoff from farms gets into groundwater

burying bodies sure as hell gets into groundwater

oh! and that doesn’t even include the gallons of arsenic they used to use when embalming bodies between about the civil war and world war one! which were often an undertaker’s top secret mix of formaldehyde, arsenic, and a bunch of other decay-stalling bacteria-killing chemicals like borax and mercury! that they kept as trade secrets. <3 so we still have no idea WHAT exactly went into a bunch of people embalmed during this era <3

#even before formaldehyde and arsenic#there have been cases of cemeteries contaminating groundwater#just from the decay of the bodies seeping into the ground over time#a couple of cholera epidemics STARTED because of runoff from cemeteries into groundwater and wells in the 1800s#AND YES#THIS ALL APPLIES TO YOU EUROPEANS TOO

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

the fluro yellow +44 life vests for the floating grandstand would slap actually

#imagine ur fave dnfing and you need to wait to be towed back to shore…humiliating#cant even throw yourself overboard bc you’d catch about nine different strains of cholera from that river

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Current Reading List

Legends & Lattes by Travis Baldree

The Grimrose Girls by Laura Pohl

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez

A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan

#currently reading#legends and lattes#the grimrose girls#wide sargasso sea#one hundred years of solitude#love in the time of cholera#a visit from the goon squad

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

huffs a little.

"i don't just drink milk religiously. yes it is halal but that's beside the point. milk is very healthy compared to other non-nutritious drinks. i also drink water and juice in case you haven't noticed."

Hook smirked. "Its only that I only really see you with a glass of milk in your hand, my love."

"And where I'm from, milk is only healthy straight from the farm or breast for a babe, swill milk was foul and I refused to drink it as a child."

#grandvizier#fun fact; most people if not all drank filtered down alchohol in the 1600s/1700s cause it was considered healthier#and its a good job hook didnt drink the milk cause most people caught cholera from swill milk that were in cities

1 note

·

View note

Text

The loss of species diversity in northeastern forests of the United States similarly allowed tickborne pathogens to spill over into humans. In the original, intact northeastern forests, a diversity of woodland animals such as chipmunks, weasels, and opossums abounded. These creatures imposed a limit on the local tick population, for a single opossum, through grooming, destroyed nearly six thousand ticks a week. But as the suburbs grew in the Northeast, the forest was fragmented into little wooded plots crisscrossed by roads and highways. Specialist species like opossums, chipmunks, and weasels vanished. Meanwhile, generalist species like deer and white-footed mice took over. But deer and white-footed mice, unlike opossums and chipmunks, don't control local tick populations. When the opossums and the chipmunks disappeared, tick populations exploded.

As a result, tickborne microbes increasingly spill over into humans. The tickborne bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi first emerged in humans in an outbreak in Old Lyme, Connecticut, in the late 1970s. If left untreated, the disease it caused – Lyme disease – can lead to paralysis and arthritis among other woes. Between 1975 and 1995, cases increased twenty-five-fold. Today, three hundred thousand Americans are diagnosed with Lyme every year, according to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control. Other tickborne microbes are spilling over as well. Between 2001 and 2008, cases of tickborne Babesia microti, which causes a malaria-like illness, increased twentyfold.

Neither West Nile virus nor Borrelia burgdorferi and its kin can spread directly from one person to another, yet. But they continue to change and adapt. And elsewhere, the reordering of wildlife species that precipitated their spillover into humans proceeds. Globally, 12 percent of bird species, 23 percent of mammals, and 32 percent of amphibians are at risk of extinction. Since 1970, global populations of these creatures have declined by nearly 30 percent. Just how these losses will shift the distribution of microbes between and across species, pushing some over the threshold, remains to be seen.

— Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond (Sonia Shah)

#sonia shah#pandemic: tracking contagions from cholera to ebola and beyond#science#virology#epidemiology#climate change#global warming#environmentalism#ecology#deforestation#animals#zoology#insects#entomology#usa#borrelia burgdorferi#lyme disease#ticks#chipmunks#weasels#opossums

12 notes

·

View notes