#not that those two things are mutually exclusive of course

Note

Nude/sexting lesbian strikes again!

For starters: my friend wants to get me into anal and a threesome with another guy because "using me with another man will be way more fun" , but I wanted to know what you think of it. I feel the need for your approval before doing anything else.

And lastly, my friend says u need to publicly thank you for convincing me into taking some dick. So thank you so much, if you allow me, I'll send you a nude to show my appreciation ;).

(Previously)

Of course I approve, sugar - it's a natural next step for you. A few months ago, you hadn't been used by a man at all, and the best you could do was send nudes; with my encouragement, you worked your way up to serving one man with your body; it only makes sense for you to learn how to entertain two at a time. And I'll be proud of you for the personal growth. 🖤

And yes, I certainly will accept another little offering from you - I'm always pleased to get a token of gratitude that doubles as a trophy.

Tell your man I said to show you a good time - it's a very special occasion, when a "dyke" takes two cocks for the first time. There'll be plenty of opportunities for him to just use you like a fleshlight, but this time, he should leave you drooling at the memory.

#not that those two things are mutually exclusive of course /#kink interactions#reorientation writing#reor: anon ask#lgetsd#reor: anon life story#dykebreaking#reor: sexting lesbian

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

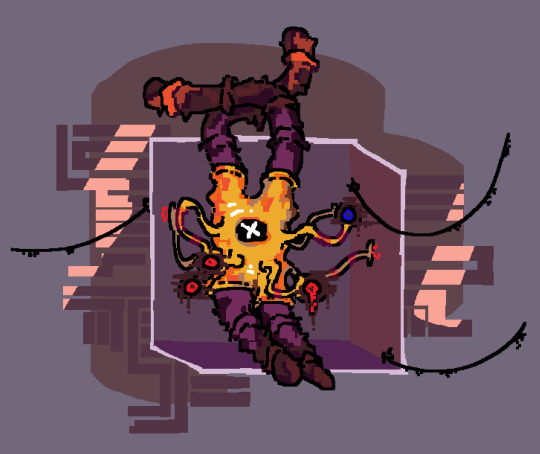

I think something that gets misinterpreted a lot in the Rain World community is what purposed organisms actually are. Theres a common interpretation that they were like “beasts of burden” and looked like or were the creatures we still see today. But this isn’t what Moon tells us, here’s what she says.

“Most purposed organisms were considerably smaller than me, and most barely looked like organisms at all. More like tubes in metal boxes, where something went in one end and something else came out the other…When I came into this world there was very little primal fauna left. So it's highly likely that you are the descendant of a purposed organism yourself!”

This dialogue paints the picture that most purposed organisms were closer to machines, or machine cogs, with biological parts than actual animals.

Of course most people are aware that creatures like leviathans and miros birds have mechanical aspects, but I think that most if not all creatures have some sort of blending of the biological and mechanical; it’s more of a spectrum than a dichotomy with cyborgs in between.

This idea is also based on some of the old Rain World concept art by Joar.

Here, it looks like melting globs of flesh, (or fleshy rubber and plastic) mutate over a metal “skeleton”. I think this can show the possible intention for purposed organisms and evolution in this world. Organic and mechanical transition seamlessly, and organic parts grow rapidly. I believe most purposed organisms started off on the more mechanical side of things, but evolved their organic “cover” in this way. Maybe everything we see, including us, have some mechanical components that are hidden by the flesh exterior.

This sort of, life overabundance and rapid growth is shown through Five Pebbles’s rot in game. His rot globs are able to grow legs and become mobile in an incredibly short amount of time, and even proto rot grows from innocuous metal walls.

My friend over at Darthzz-Ploo-World really coined this interpretation (and many others) in my opinion and did a wonderful art piece showcasing it.

My friend Re also did some great art showcasing a theory on orange lizards evolving from those computer boxes in Sky Islands and the exterior.

I also did some doodles on my own theories in the same vein. This time on the origin or Shoreline leviathans from Moon’s collapsed iterator components.

But yeah, I think Downpour leaned more into the “beast of burden” interpretation, but I also don’t think the two are mutually exclusive. Not everything needs to be a tube-box descendant I suppose.

657 notes

·

View notes

Note

59 Leona, it'd take a lot for him to admit but he would say it eventually. (Also I know you'd recognize me but I'm shy, so anon it is)

Gender Neutral Reader x Leona Kingscholar

Word Count: 1.5k

Prompt 59: "People like me aren’t supposed to have someone like you, I think fate was being harsh on you."

[EVENT MASTERLIST]

You are nice, and you are stupid. And those things aren’t mutually exclusive.

Sometimes you’re nice because you’re stupid, and sometimes you do stupid things because you’re too nice for your own stupid, stupid good. And it drives Leona half insane.

Which it shouldn’t, because nice, stupid people like you are just as annoying as his brother. Goody-two-shoes with buttoned vests and sparkly, star-shaped stickers on their term papers.

“Did you remember your homework?”

Leona flicked his tail in your face and you scrunched your nose over your notebook.

“Well?”

“Of course I remembered,” he scoffed, lazing back against the roots of one of his favorite trees. This spot used to be so much quieter, so much more peaceful, before you decided to trail after him like a duck quacking for its mother.

“Did you do the homework?” you clarified, and Leona rolled his eyes.

You sighed and starting ruffling around in your bookbag. “I brought a spare copy of the worksheet. You’re going to drive Ruggie insane, y’know. If he winds up stuck with you for another year because you failed for not turning in assignments.”

“Yeah. Sure. Another three-hundred-and-sixty-five days to rifle through my wallet. Worst news of his life.”

You huffed good naturedly and handed him the sheet of crisp, white copy paper and a pen. “Get to work, Kingscholar.”

“Oh?” he drawled, closing his eyes and settling back, loose limbed and all long, lean leisure, against the tree trunk. Clearly ready for an afternoon snooze. “Make me.”

You sighed again and reached over to flick your own well-used pen against his ear. It twitched under your fingers—soft, and tufted. The finest of the pale, tan fur brushing up against your fingertips. “Fine. Be that way. See if I bring you lunch tomorrow.”

“You will,” he scoffed.

“Yeah,” you sighed, sounding resigned and foolishly fond. “I probably will.”

See? Stupid. So easy to manipulate. So willing to let yourself be squashed under his clawed thumb. It was a wonder you’d managed to survive in this school at all. Nevertheless by clinging onto the coattails of someone like him. He’d never made anyone’s existence easier a day in his life, and he certainly wasn’t going to start now, just because you were too soft-hearted and slow to see a looming predator for what it was.

“Just give me that stupid fucking paper,” he snapped, sitting upright and swatting away your poking pen with a sneer. You laughed into your palms like a secret—bright, and merry, and dumb as a fucking rock.

“Whatever you say, Leona.”

.

.

You’d handled his Overblot with a strange sort of aplomb that at first Leona had attributed to perhaps a lingering, hidden confidence that he’d just never bothered to unearth. You were just some herbivore, and even the littlest rabbits could bite back when you put them in a corner. But then he’d come to the decision that that easy conviction was just another symptom of your rampant stupidity.

“I know you guys don’t want to hurt me, or any of us. Not really,” you shrugged around a wad of cotton—the blood dripping from your nose slowly drying up to a tacky, sticky dribble. Leona gaped at you outright.

That was your grand explanation. For why you’d been so eager to charge forward when he’d collapsed in a pool of inky nightmares and self-loathing. And the very same reason apparently thatyou’d felt so comfortable rushing forward to treat Azul Ashengrotto’s blubbering, hysterical, breakdown with the same urgency.

“That octo-prick would have ripped you in half,” he sneered, fingers twitching a nervous rhythm against his palms as he watched the nurse wrap another layer or bandages around your head.

You shrugged. “Not on purpose.”

You were going to give him an aneurism.

“You’re going to get yourself killed,” he snarled, ignoring the horrible, twisty thing curling like bile through his chest. “And I’m not going to bother paying for some self-sacrificing idiot’s funeral.”

Another shrug.

“That’s alright,” you hummed, a soft sort of crooked smile on your mouth. “Would’ve been a waste of money anyways.”

Leona didn’t talk to you for a week after that. Surely because your stupidity had reached such a fever pitch that it was no doubt contagious, and he needed to protect his far superior and more valuable brain. Not because the image of you smiling and nodding along to his declarations that he wouldn’t put the effort into mourning your death had soured something so deep in his gut that he wasn’t sure he’d ever be able to scrape it out.

.

.

When he received a letter from home asking him to return for some shitty coronation nonsense for his equally shitty brother, Leona had debated just skipping it outright. Who was going to stop him? You?

Well. Yes, apparently.

“It sounds important,” you hummed, peering over his shoulder at the neat, formal scrawl of the summons. “You should go.”

He snorted. “I don’t want to be there, they don’t want me to be there. What’s the point.”

You frowned, brow crinkling in the middle.

“Well, that’s not true,” you said, perplexed. “They wouldn’t write to you if that was the case.”

Leona snorted, eyes darting away to glare bitterly off into the corner. “Not like they have a choice.”

“Well then you don’t have a choice either,” you argued, firm. “I’ll go with you. See? It says you can have a plus one. You can camp out in your fancy, princey, bedroom. And I can siphon you snacks from the fancy, princey hors d'oeuvres tables. That way we both win. You get to be a reclusive asshole and rub the fact that that you still went in everyone’s faces, and I can get access to some tasty, royal food that I’ll probably never be able to afford again for the rest of my life.”

“Should’ve known you’d be like Ruggie—only using me for the free food,” he sighed, melodramatic and obviously put on.

“Well, also because I thought you could use the emotional support,” you added, a touch too soft and far too genuine. “But I didn’t think you wanted to hear that bit.”

“You’re right,” he scoffed, turning onto his side to hide the strange, miserable heat pricking at his skin. “Don’t ever say corny shit like that again.”

“Aye, aye, captain,” you grinned, flicking at his ear, and Leona added another mental tab to his never-ending list of reasons that you were really far too brainless to keep functioning at all.

.

.

You were nice, and you were stupid. And Seven, he wanted to be anywhere but here.

“My brother hasn’t ever brought someone to one of these events before,” Falena had said, to your face. Idiot to idiot communication.

“I didn’t give him much of an option,” you’d chirped, perfectly pleasant. “I don’t think he wants me anywhere near here, to be fair. Or around him in general. But I’m like a cockroach. Can’t get rid of me.”

And Falena had laughed. Because he was terrible. And said, “I’m sure he must care about you very much, little cockroach.”

And then because you were more terrible, you laughed back and said very assuredly, “Oh, not at all.”

Which was—was—

“Do you really think that?” he snapped, once the two of you were alone. And you blinked back at him with wide, owlish eyes.

“Think what?”

Think at all,he wanted to sneer, but just glared silently and bitterly into the middle distance—fighting the nonsensical, irritated swishing of his tail.

But you just kept staring at him. Like he was the moron here. Which was unacceptable.

“Look,” he frowned, sharp and miserable. “I get it. People like me aren’t supposed to have someone like you. Whatever gods exist out there were playing a shitty fucking joke on you when they dropped you in my lap. But you’re stuck with me. So stop—” he bit out, fighting that awful, twisty thing in his gut that never seemed to fully go away. “Stop talking like I can’t stand you.”

“…oh,” you mumbled, whisper quiet—that wide, startled gaze flicking away in embarrassment. “Oh.”

“Oh,” he echoed, sharp, and you snorted a laugh that seemed to surprise even you.

“You’re stuck with me too then, y’know,” you said after a long moment. “Even when I make you grumpy.”

“You don’t make me grumpy. I am grumpy. You make me—” he cut off quick, eyes darting away petulantly and an absolutely unfair heat rising along his cheekbones.

“Itchy,” you piped in, and he gaped at you in shock.

“What?”

“You know,” you shrugged, awkward, and reached up to wiggle your fingers. “Cockroach. Many legs. Squirming. Itchy.”

“Never say any of those words again.”

You laughed into your palm—inelegant and a touch too loud. Leona felt his lips quirk.

“Thank you,” you said after a moment, once your giggles were a bit more under control. And leaned forward quick as a whip to press a nervous peck against his cheek. “For being kind to me.”

Kind.

Leona reached up to press a hand against the too-warm skin with a terrible, unfamiliar sensation in his head not unlike the fuzzy, white drone of TV static. And a horrible thought managed to filter its way through the floating, buzzing sensation curling through the whole of him.

Oh, fuck. It is contagious.

.

.

#4k Event#twisted wonderland imagines#twst x reader#Leona x Reader#Leona Kingscholar x Reader#My Writing#Writing Prompts#Leona Kingscholar

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mother's Day

Summary: Jack has a very important, surprise gift to give you on a special holiday for your inaugural celebrations together

Paring: Aaron Hotchner x Fem!Reader (Fluff)

WC: 1.4k

Whenever he can, Aaron leaves work early to get Jack. Thankfully, with Strauss's return, he's not still stuck doing two jobs, so he finishes his work in time to get Jack from school. You also love when he has days like that because it means he'll cook something delicious and homemade, maybe even dessert if Jack has anything to say about it.

Jack gets into the car like any other day, but what he says isn't the typical comment about his day or request for an afternoon activity. "Did you know it's Mother's Day this weekend?" Jack asks.

Aaron's heart clenches in his chest. Mother's Days, birthdays, Christmases, and the anniversary of Haley's death are all especially hard days for Jack, and Aaron tries his best to support his son. "Do you want to talk about mom?" He asks softly as he drives. Since Jack doesn't remember a lot of it, Aaron fills in the blanks and answers the questions.

"No, I might want to talk to her tonight, but I want to get a present," Jack explains.

Aaron frowns a little but accepts it. "We can do that. What do you want to get her?"

Jack's thinking face looks like his dad's, something you were the first to point out to Aaron. "I don't know." He admits. "You always get roses for Y/n so maybe I can get her flowers?"

That really throws Aaron, and it rapidly occurs to him that he and Jack aren't talking about the same person. "You want to get a present for Y/n?" He clarifies.

Jack shifts uncomfortably in his car seat, clearly nervous at his father's reaction. "I'm sorry. Is that wrong?"

Aaron can't shake his head fast enough. "No. No, of course not, buddy." He assures his son, reaching back with one hand to touch the boy's foot for extra reassurance. "I think she'd really like that. What made you think you want to get something for her?" He tries to ask it in a non-judgemental, casual tone.

"Well, in class, we were all talking about what we love about our moms, and a lot of the things that my friends were talking about are things that Y/n does for me." He explains, and Aaron feels his heart clench in the best way that time while he bites down a wide smile. "Mom is still my mom, and I'm not forgetting how she used to do those things for me, but Y/n is there for me too."

Aaron notices what he's emphasizing, and he's immensely proud of Jack for being able to express those feelings, understanding that appreciating his mom and recognizing your role in his life aren't mutually exclusive.

Then he's thinking about you as he absorbs the confession. And how lucky he is to have you. You have been a constant source of support and love, a beacon of hope and stability in the wake of their family tragedy, never anything but good to them. He feels so much joy and a tiny bit of sadness. He knows Haley would have loved you and appreciated how much you care for Jack, but he wishes she was there to see it.

He's choked up as he goes to speak. "Jack, that's very sweet of you, and I think, no, I know, Y/n feels the same way about you. She thinks you're the most amazing kid ever."

Jack smiles softly. "She does? Really?"

Aaron can't nod fast enough. "Yes, she always tells me how great she thinks you are."

"So we can get her a gift for her?" Jack confirms, looking hopeful.

"Absolutely." Aaron agrees, taking a right turn to the mall rather than a left to their home. "Whatever you want."

~

It's been such a long week of work and Saturday mornings are Jack's soccer games, so as soon as your Saturday movie night is over, you're fast asleep next to Aaron.

Like usual, he stirs beside you first on Sunday morning, but when you go to get up with him, he softly whispers for you to go back to sleep and that's very easy to do.

When you next wake up, the sun is creeping through the blinds at a different angle, signaling that you slept in for longer than you usually would.

There's a soft knock at the bedroom door before you can properly wake up and get out of bed, and you softly call out for who you expect to be Jack to come in.

You're right in your guess that it's Jack, who quickly jumps up onto the bed with you, followed by his father who has a breakfast tray with a big vase of flowers on it accompanying a delicious-looking plate of French toast.

"Wow, you've both been busy this morning." You mumble sleepily as you sit up to hug Jack who's jumping into your arms.

"Happy Mother's Day!" He cheers joyfully, and you're taken off guard by the greeting, completely shocked.

Your eyes dart to Aaron's to make sure you heard Jack correctly, and his wide smile confirms you have. He's looking between you both with so much love and tenderness, his heart so full it feels like it's bursting.

Your eyes fill with tears as you realize the enormity of what he's just said. "Thank you, Jack." You squeeze him even tighter in a hug, not wanting him to slip away from this perfect moment.

He pulls back and smiles at you before turning back to his dad. "Can we give it to her?" He asks.

"Sure, bud." Aaron agrees, setting the tray down over the top of your legs. He sits near the foot of the bed while Jack snuggles into your side.

Jack reaches forward to pick up the little box next to the breakfast. "Here." He hands it to you. "Happy Mother's Day. Thank you for caring so much about me."

You kiss his forehead, holding him tighter to his side as you gladly accept his thoughtful and unexpected gift. "You're very welcome. I love you, Jackers."

Whatever he has for you has to be jewelry from the small, flat shape of the box and the designer jewelry stamp. You open it up, and your heart melts more, if it were possible. What's inside is a gorgeous gold bracelet with a flat, circular charm, engraved with the letter J.

Jack touches it as your finger does. "It's a J for Jack."

You nod so you don't start crying too much. You're so overwhelmed by gratitude and happiness that you can't help but let one tear slip out.

"Thank you." You finally get the words out. "It's perfect and I love it so much. I'm going to wear it every day, so you're always with me."

Jack's grinning a proud grin, clearly proud of himself for picking it out. Aaron had told him how much you would love it, but seeing it confirms it for him. "I think it'll look beautiful on you." He tells you adorably.

You chuckle a little. "You're a sweet talker just like your dad, you know?"

Aaron laughs next to you, but Jack's confused at what your compliment means, and his attention is drawn elsewhere. "Daddy and I made French toast for me as well. Oh, and I got you flowers."

It's a gorgeous bunch of flowers, beautiful colors, and lovely smells. "Thank you so much. Both of you." You repeat to them, making sure they're feeling the reciprocated love you're feeling.

"You're welcome," Jack says politely.

Aaron leans over to kiss your forehead. "I love you." He whispers.

You whisper it back before looking back at your breakfast plate. "There's a lot of French toast here, so I might need some help eating it." You say suspiciously, looking between Jack and Aaron.

Jack's eyes light up like he's been waiting for you to offer him some of it, and you can't blame him, it looks and smells like restaurant quality and you know breakfast foods are Aaron's strong suit cooking-wise.

"I am kind of hungry." Jack agrees, smirking at you softly.

"Eat up then, bud." You say, offering him the first spoonful. "We've got lots of fun stuff to do today."

#aaron hotchner#aaron hotchner x reader#criminal minds#aaron hotchner x you#aaron hotchner x y/n#aaron hotchner fanfiction#aaron hotchner fluff#aaron hotchner fic#aaron hotch hotchner#aaron hotchner imagine#aaron hotchner one shot#criminal minds oneshot#criminal minds fic#criminal minds family

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

What Are We?

Pairing: Dean Winchester x Fem!Reader

Summary: Dean and you do a lot of couple things together but yet…you’re not a couple, and you often wonder why.

Original Prompt: Requested by anonymous | Hey! How are ya? I don’t know if you write for chubby reader but if you’re comfortable with that then could you write something about dean and reader being in a situationship and the reader thinks he doesn’t wanna date her cause of how she looks and he confesses that he actually likes her? You can change it however you want. Thank you so much!

Word Count: 2.1k

Warnings: Cursing (2x), Angst, Fluff, Talks of body "issues"

Authors Note: Thanks for the request anon friend! Of course I’ll write it. I don’t discriminate and neither would Dean 👌🏻 | As a girlie who has a slight muffin top myself, I loved this prompt <3 | If you liked this, don’t forget to like & reblog. I really appreciate it! Feedback is always welcome ♡

Situationship (noun): a romantic or sexual relationship that is not considered to be formal or established.

This was the type of relationship that you've had with Dean for the past several months. At first, it was something that you were okay with because you thought that maybe it would eventually turn into something more. As you felt that if he liked you enough to sleep with you, make out with you, and basically do everything a "normal" couple does, then why wouldn't he eventually want to make things official with you down the road? But it's been months, and there's been remotely no talks about making things exclusive, and you were really starting to wonder why.

Exclusivity was a word that you wouldn't use to describe Dean, but it was something that you wanted with him, wanted with him because he was the one person that you could genuinely see yourself being with. But at this point, based on the current situation that the two of you were in, you were afraid that he didn't actually want to be with you, that he was just using you until he had found someone better...found someone that was his usual toothpick thin type that he tended to go for, which wasn't your body type.

When it came to your body type, it was something that you had a love/hate relationship with. You weren't the thinnest girl in the world, but you still liked the way you looked, as you believed the muffin top you had was just something more to love. And at this point in your situationship, you didn't think Dean minded either, as he would always trail kisses along your stomach, telling you how beautiful you were, and how perfect you were. Complimenting how much he loved your thick thighs as he gripped them. But at the same time, that talk seemed to never leave the comforts of the Bunker; and if it did, it stayed strictly around your mutual friends. The hand holding and kisses would cease as soon as the two of you would leave the Bunker, and you couldn't help but think that he was embarrassed to be seen with you, be seen as someone that he was romantic with.

That's why you were confused, confused about what was actually going on between the two of you. He would constantly tell you how beautiful you were and hold your hand, and do those types of things in front of Sam, Jack, Cas, Jodi, Donna, but would never do these things in public. You were good enough to sleep with, but yet you weren't good enough to be considered his girlfriend?

You walked down the hall, a few books in hand as you made your way to the War Room. But you were stopped when you heard Dean call your name from his bedroom as you walked past. You turned around quickly, and went back to stand in his doorway. “What’s up Dean?” You asked.

“You didn’t say hi to me when you walked past,” he stated, flipping to the next page in his book.

To be honest, you did see him, and normally, you would have said hi to him, maybe chatted for a little bit until you eventually made your way into the War Room. But today, because of what was on your mind, you didn't really want to speak to him until you were sure about how you were going to handle this situationship between the two of you. “Oh, sorry,” you apologized.

“You okay Sweetheart? You seem distracted today,” he stated closing his book.

“I’m always like this,” you said. He got up from his bed and started making his way toward you.

“No, you’re not actually. Your voice is different, and your body language tells me other wise,” he said. “So, what’s up?”

“Very Sherlock of you,” you said. “I’m fine honestly.”

He looked at you with slight disbelief. “Y/N, we've been friends long enough for me to tell when you're lying." There it was. Friends. He used the word friends. You weren't sure if you should be relieved or disappointed.

“Yeah…friends,” you repeated the word.

“Are we not…friends?” He seemed hurt by your usage of the word, which caused you even more confusion.

“Honestly, I don’t know what we are,” you admitted, and you didn't expect those words of yours to come out like that.

He cocked a brow. “What do you mean? Did I do something?” As long as Dean could recall, he hadn't done anything to have hurt you as of late. He tried to recollect everything that he had done or said to you over the last couple of days, and he was honestly coming up with nothing; but there must of be something, as you would have never said something like that to him if there wasn't at least something wrong.

“No, no, you did nothing wrong I’m just…” you sighed. “I’m confused that’s all.”

“What are you confused about?” He asked.

“Do you mind if I came in and we closed the door?” You asked, and he nodded. He felt himself get nervous just as much as you were starting to feel the same. Holding your books in your hand you walked inside and Dean shut the door behind you. Setting your books on his table the two of you sat on the edge of his bed. You had no idea where to start, as you thought you'd have more time to figure out this conversation in your head. “I’m confused about what we are.”

“What do you mean?” He seemed genuinely concerned.

"What this is between us. You say that we're friends, but we have sex, make out, more often than not sleep in the same bed together, do everything normal couples do but yet...you say that we're friends."

"If you don't want us doing any of that anymore that's...fine," he said, but Dean wasn't remotely fine with stopping what was going on between the two of you, because he loved being able to just crawl into your bed at night and just kiss you and hold you in his arms.

You sighed in frustration, as he seemed to completely ignore the point you were trying to make. "That's not what I'm saying Dean. What I'm saying is, well, I'm more like asking really." You took a deep breath, and you felt your heart start to race, slightly afraid to ask what you were about to ask. "If I'm good enough to sleep with and do couple things with, why am I not good enough to be your girlfriend?"

Dean honestly didn't know what to say to you. Well, he did, but he knew that it was a poor excuse of an answer, an answer that he knew that you weren't going to believe even though it was true. All he wanted was to be with you, exclusively be with you (which he essentially already was). But he was afraid, afraid that the second the two of you mutually agreed to be together and only together, that you'd eventually realize pretty quickly how disappointing of a person that he was, that the novelty of him would somehow wear off. "It's cause I'm not thin right?" You asked.

Your question caught him off guard, honestly annoyed that you would say that was the reason he didn't want to be exclusive with you. He honestly didn't understand why you had thought that was the reason, as he thought that he had made it pretty clear how beautiful he thinks you are inside and out. But, apparently he hasn't been doing a good of job as he thought he had been. "What? Y/N, that's not the reason," he stated, his voice slightly annoyed.

"Then what is the reason Dean? I mean, that's honestly the only reason I can think of. Well, that or...you're embarrassed by me," you said, your voice getting lower.

“I’m not embarrassed by you Y/N, you know that,” he said.

"If you're not embarrassed by me, then why won't you hold my hand in public?" You asked. "Because, it's just weird to me you know? I mean, you have no issue telling me how beautiful I am in front of Donna, Sam, Jack. You have no problem kissing me in front of Claire or Cas. But the second we aren't around any of those people, the second we are outside of the Bunker, you want nothing to do with that with me anymore." Your voice was about to break, as all you wanted to do was just not have this conversation anymore; you just wanted to crawl into bed under the covers.

Dean knew you had a point, and he could fully admit to everything that you had just said. He did only hold your hand, or kiss you, or tell you how beautiful you were when they were in the presence of friends or family, but it was because he could be vulnerable in front of them; he wasn't afraid to be vulnerable in front of them, but he was afraid to be vulnerable in front of people he didn't know, afraid that they were somehow going to use the love he had for you against him, and it was something he didn't want to risk. "I'm sorry," he began finally, and you raised a brow at his response. "I'm not embarrassed by you Y/N, not at all. And the reason I'm not with you, with you isn't because I don't think you're skinny enough," he hated saying those words. "Honestly, it fucking breaks my heart that you think that's the reason because I think I do a pretty good job at telling you how beautiful you are," he said, taking your hand. "And it's not just bedroom talk. I honestly think you're so fucking beautiful."

"Even with my muffin top?" You asked, slight amusement in your voice, but you were still serious in your question.

"It's just more of you for me to love," he said.

"When you mean love..." you trailed off. "See, now I'm more confused."

He sighed. "I know what I'm about to say is something that you're not going to believe, but it's the truth," he took a deep breath before he continued. "Not only do I think you're too good for me, but I'm afraid that someone will use what we have together against me somehow, against us somehow. And...I can't...I can't risk that." I love you too much, he wanted to say.

"So, you're telling me the reason you don't hold my hand in public is because you're afraid some demon or something will see that and then use it against us?" You asked, clarifying. "Dean." You wanted to not believe him, but you did, and you hated that this was the reason. You hated that because he was so afraid of losing you, losing what the two of you have, that he didn't want to even hold your hand outside of the Bunker walls.

"I know you don't believe me Sweetheart," he said, his voice sounding slightly sad.

"I do Dean I just..." you sighed. "You know I can take care of myself right? How many times have you seen me take on two, three, four creatures at time and only had a single scratch?" You took his other hand. "Dean, I genuinely want to be with you if you want to be with me. I know you're afraid that you're going to lose me but, newsflash, I'm afraid of losing you too. That's...that's just what life is Dean. It's just more of a reason to go for it, because...we might not always be here."

Dean knew you were right, you were always right. And to your point, it was something that he hated, but he couldn't help but find himself agreeing with. He would rather have a little bit of time with you than nothing at all, because at least he would have some memories of the good times you had together, instead of the constant, "What if's?"

"Dean, I love you," you said. "You're the only person I want to be with okay?" You leaned in, and so did he, mere inches away from each other's lips.

"Love you too Sweetheart," he replied back. He leaned in fully now, meeting his lips to yours.

"Does this mean we're together? Like you'll actually hold my hand in public or is that still off the table?" You whispered.

Dean grinned. "I'll grab your ass in public if you want me to," he winked, and you felt yourself slightly blush at his comment.

The two of you knew that the newfound relationship wasn't going to be easy, but it was something that the two of you were willing to fight for.

Tag List: @roseblue373 @beansproutmafia @queenie32 @deanwanddamons @missy420-0 @jackles010378 @mrsjenniferwinchester @syrma-sensei @k-slla @justletmereadfanfic @deans-daydream

If you'd like to be added to a tag list, let me know!

#dean winchester x reader#dean winchester x you#spn#supernatural#spn imagine#supernatural imagine#spn one shot#supernatural one shot#dean x reader#dean x you#reader insert#female reader

621 notes

·

View notes

Text

sweet cliches

THE FRIENDZONE

pairing: college!abby anderson x fem!reader

description: y/n thinks that abby may have trapped her in the friendzone, and begins to fear that it is far too late to escape.

warnings: VERY QUICKLY AND NOT VERY WELL EDITED, light smut, anxiety, fear of unrequited feelings, reader is a needy hoe, abby is a dommy mommy, swearing

words: 2.1K

date posted: 03/08/23

more college!abby

In general, Y/n was very secure within herself. Of course, she had experienced her fair share of insecurities and would certainly like to change a few things about herself, but wasn’t that the case with all girls in their early-to-mid twenties? She didn’t think herself to be anything special; not the smartest, funniest, or prettiest girl around, but she also didn’t think that any of those things might have made her blind to the fact that her own feelings could have potentially been unrequited. Until she met Abby.

Abby had been on her radar for around a year before they had even formally met. Y/n was fortunate enough to have had an in with a few of the girls on the cheer team, making the cut with the kind of ease that freshman were scarcely offered. For anyone around campus, it was impossible to not not know Abby’s name and face at the very least–as the school’s star athlete, she was plastered on posters, billboards, and the school’s Instagram for everyone to see, though it was even more impossible for those who were involved in the athletics department to ignore her six-foot tall frame as she barrelled down the lacrosse field, expertly weaving through the opposing team’s defence and hurling the ball into the net with frightening strength.

It had only taken half a practice for Y/n to be completely enamoured with the upperclassman. She spent the following weeks discreetly finding out little things about her; she was from Salt Lake City, she was in her junior year of Biology with a minor in Classic Lit, and kept to herself more than Y/n would have expected from someone so popular–this, she had determined from the fact that she had only been able to find out very general details about her even from Mel and Nora, who both ran in the same friend group as Abby.

Nora had quickly taken a liking to Y/n, referring to her almost exclusively as my freshie around their teammates. Y/n honestly did like Nora, and had become somewhat friends with her before she even laid eyes on Abby, but she couldn’t help but wish that she would introduce the two without having to ask her. Hell, she didn’t even know for sure if Abby even liked girls, especially because the only previous relationship she had heard about was with a man. She also didn’t want to let on to Nora that she was interested in her friend in fear of making her believe that she was using her in any way. So, after a long internal debate, she decided that she was going to stick it out until fate came into play.

The moment finally came early on during Y/n’s sophomore year. A few of Nora’s friends were hosting a party to celebrate the start of the lacrosse season, and of course she would extend the invitation to her own teammates. Y/n hadn’t even expected to see Abby that night, considering that she rarely made appearances at any big parties that Y/n had been to, but the moment that Nora had waved her over to join them on the couch, she couldn’t help but pray that she wouldn’t somehow embarrass herself in front of the intimidating blonde.

As it would turn out, Abby’s head had begun to spin the moment that Nora had introduced them, her stormy blue eyes following the outline of her back as their mutual friend dragged her away and into the crowd of the make-shift dance floor. The day that she walked into the coffee shop and noticed who was standing in front of her, her heart almost beat out of her chest. She had stood there for a few moments, figuring out how exactly she would approach her without coming off as a creep–though Y/n probably would have folded no matter how she did it. Then, after the brief, but very enlightening conversation, Abby couldn’t wait any longer and asked Nora for her number.

Fast forward two weeks, there was hardly a moment where they weren’t either hanging out, texting, or Facetiming one another. Y/n was initially feeling very certain that Abby was at the very least wanting to hook up with her; when they were together, she was constantly making up excuses to have an arm around her shoulders or a hand on her leg, and when they were apart, she was quick to text back and was always interested in what Y/n had to say. All of the signs were there, but why wasn’t Abby making a move? In other situations, Y/n would have had no issue taking the bull by the horns, but she couldn’t help but fear that Abby might have been looking for nothing more than a friend.

But how could she only view her as a friend when she treats her like so much more? At parties, her eyes were constantly scanning the crowd for her, pushing her way through the crowd in an instant the moment that she lays her eyes on her figure. When they were together, she treated her like she was the only person in the world that mattered, and always seemed to treat her differently than she would treat her other friends. They had to be something more by this point, but she just couldn’t figure out why she was so hesitant to make a move.

Even now, as she was tucked into her side in the comfort of Abby’s apartment, the older girl’s arm curled around her shoulders securely as she watched the television screen intently, Y/n was entirely too self conscious of the fact that this was certainly not something that platonic friends would do. She couldn’t help but watch Abby out of the corner of her eye, catching every flicker of emotion that crossed her features. The film had been on for almost an hour and a half by this point, and it was quite possibly the most boring, uneventful movie she had ever seen.

“Something on my face, pretty?”

Y/n’s cheeks warmed with embarrassment, obviously having been caught staring despite her every effort of discretion. She shook her head quickly, turning her gaze back to the film on the screen to avoid the sky blue hues of Abby’s eyes. The bulge of her bicep clenched behind her head, nudging her to face her once again.

“No,” she muttered, “Just thinkin’.”

“Thinking about…” Abby prompted, raising her brows with a sly smirk appearing on her perfectly pink lips.

“Things,” Y/n shrugged, “Papers, practice,” she hesitated before adding, “You.”

“Me?”

She shrugged again, “We’re hanging out right now, of course I’m thinking about you.”

Abby was silent for a moment, “Wanna know what I’m thinking about?”

“Eating raw meat and lifting ridiculously heavy objects?” Y/n chucking, trying to diffuse the growing tension.

“Close, but not quite.” Abby snorted, “I’m thinking about how awful this movie is.”

“Really? You’re the one who put it on.”

“Yeah, well I wasn’t expecting to actually watch it.”

A lump lodged itself into Y/n’s throat at that, leaving her entirely unsure of how to respond.

“I was thinking about you, too, but not just because we’re hanging out. I was thinking about how pretty you look, how good you smell, how much I wanna kiss you right now.”

The words flew out of her before she even had a chance to process them.

“Then why don’t you?”

A moment of silence passed, and Y/n was beginning to wonder if she had crossed a boundary. Perhaps there was a reason as to why she hadn’t made a move yet, something of good reason that prevented her from doing so. Then the moment was over, and the distance between their lips had closed.

Abby’s lips were softer than she had imagined, though she should have suspected as much considering that the woman was virtually inseparable from her chapstick, and they tasted faintly of some kind of melon and perhaps a touch of mint. Her movements were gentle, tentative and curious as she explored the opposing side of the boundary that she had finally crossed. Y/n finally responded, lips pursing against hers and moulding to her every movement. She was pliant to her desires, following Abby’s lead as she curved the large expanse of her palm around the base of her skull.

It was slow, but a silent understanding passed between the two women throughout the interaction. A small whine vibrated from Y/n’s throat, her body melting against Abby’s chest as she tugged her closer and into her lap, fingers sliding down to curl around her clothed thighs. Y/n’s chest heaved, leaning impossibly closer as she tucked one hand into the loose blonde strands at the nape of Abby’s neck, the other sliding down her front to feel the rigid expanse of her abs beneath the cotton of her t-shirt.

“Mmm,” Abby mumbled against her lips, “Can’t believe I waited this long.”

Y/n ignored her, pressing her lips tighter against hers in desperation. She was almost embarrassed at how needy she had become so easily, completely malleable to Abby’s every will and growing even more desperate as Abby continued to babble on, instead turning her attention to kiss, bite, and suck at the pale skin of her muscular neck.

“Didn’t wanna make you think I just wanted a hookup,” Abby muttered out, shuddering as Y/n’s teeth raked against her throat. “Hey, hey, you listening?” she pulled her back to look into her eyes, almost moaning at the sight of her hooded eyes, lips swollen and glistening with spit, “Jesus, you look so beautiful right now.”

Y/n whimpered, “Abs, please.”

“Listen,” Abby shook her head, cupping her cheek affectionately, “I like you. A lot. I didn’t wanna rush things, so don’t take this as a quick fling.”

Y/n nodded, pushing closer into Abby’s palm, “I won’t. Thought you were gonna friendzone me.”

“Me? Friendzone you?” Abby laughed, “Baby, how stupid do you think I am?”

Baby.

Y/n shifted in her lap, “Abby, please. I don’t–I’m not trying to–I need–”

“Tell me what you need, baby.”

She could burst into tears at any moment, “You.”

The next ten minutes passed in a blur of movement and a flurry of discarded clothing, Y/n finding herself pressed into Abby’s sheets in nothing but her baby pink thong, the hulking figure of the lacrosse captain crouched over her having stripped down to her own boyshorts.

“Who knew you would be such a needy little thing, huh?” Abby smirked down at her, fingers pinching at the hardened nipples of the girl that she’d been so patient to have. She chuckled as Y/n began to babble almost incoherently, “You need somethin’? Why don’t you just ask?”

“I need you, Abs,” she whined, pulling at her with all of the strength that she could muster to feel her lips against her once again.

“Ah, ah,” the blonde tutted, “Gotta be more specific, pretty girl. What do you need?”

Y/n writhed beneath her, “Please touch me, please.”

“Well,” she grinned, “Since you asked so nicely.”

Abby kissed her lips quickly, chuckling as she chased after her with a whine of annoyance. The blonde pressed a trail of kisses down her body, taking special care to show some love to her breasts before moving even further south.

“This what you need, baby?” Abby asked, hot breath fanning over her covered mound. “You want me to kiss your pretty little pussy?”

Y/n whined again and nodded anxiously as she wiggled her hips closer to her face.

Abby leaned forward, leaving a long, soft kiss on her covered clit, basking in the mewling that she received in response, hooking a finger into the waistband of her panties and turning her gaze back up to the frazzled features of the girl below her before tugging them down to her ankles and diving face first into her.

“How’s this for being friendzoned?”

#reader insert#x reader#imagines#lesbian#abby anderson#abby anderson imagine#abby anderson x reader#abby anderson x you#abby tlou#college!abby anderson

651 notes

·

View notes

Note

If your book earns out (eventually)that's good for the author and publisher, right? Why is there a big stress on preorders, first week sales and what a book does right out of the gate? Shouldn't publishers wait a year before they make a final determination to a books success? Especially with things like TikTok that can help bolster sales out of nowhere. It seems like there's so much pressure on authors for success straight away. Do publishers just want their investment back ASAP?

I don't know how you got your question to be in bold? ANYway, since there are like 30 questions in here I'm just going to take them bird by bird.

If your book earns out (eventually) that's good for the author and publisher, right? Yes, of course.

Why is there a big stress on preorders, first week sales and what a book does right out of the gate? Well, for several reasons:

-- A book with a ton of pre-orders feels "exciting" -- if you owned a bookstore, and you had ordered two copies of GREATBOOK initially to come in -- but then 30 people pre-ordered it from you -- you'd probably strongly consider ordering EXTRA copies, right? That seems like an indication that people really are interested in this book, you should have a pile of them, not just two! You should put it on display!

-- A book with a ton of pre-orders and first-week sales has a much better chance to hit a bestseller list (specifically, the NYT bestseller list). Why? Let's say your author started asking people to pre-order six months ago and those orders have been stacking up in dribs and drabs. But that book doesn't go on sale until January 15th. ALL SIX MONTHS of pre-orders are going to get rung up on release day. The NYT is based on books sold during one week's time compared to all other books sold during that one week. Obviously, a book with a ton of pre-orders will get a big boost that week!

-- Books that hit the list get more visibility, they get people hooting about them on social media, they get to be called "NYT Bestselling" which seems fancy, ALL of that can very much help sales going forward. Is it the be-all-end-all? No, of course not. But there's no doubt that it's NICE!

-- The majority of publisher-led publicity and marketing efforts are focused on before or soon after release date -- getting gatekeepers like booksellers, librarians, etc whatever interested in ordering the book into their stores and libraries, getting reviews, pitching the book to media outlets, etc -- so IF those efforts are going to help a book, you're more likely to get that boost when the book is new. After several months have gone by, a thousand newer books have come out, focus has shifted to those books.

Shouldn't publishers wait a year before they make a final determination to a books success?

I mean - I think they do? These things are not mutually exclusive. Of course they'd like to have a lot of success right out of the gate. Obviously, they'd be delighted to have a lot of success later, as well. Plenty of books grow in sales as time goes on, etc -- I don't think anyone is deeming a book a failure if the book doesn't hit it out of the park immediately. I can't speak for adult books, but on the kid's side, we don't really know what kind of longevity a book might have for probably at least a year, because there needs to be time for books to make their way onto state lists, into curriculum, and stuff like that -- for teachers to read it to classrooms, for kids to get hooked and tell friends, etc etc. Once a book is out in paperback and really getting imbedded into schools, we might see BONKERS sales that could never have been predicted from a sluggish start in bookstores a year or two earlier. Publishers are well aware of this -- books are not going out of print in the first year after release.

Especially with things like TikTok that can help bolster sales out of nowhere. It seems like there's so much pressure on authors for success straight away.

Yep, there are plenty of examples of books that have surprising late-in-life success bc of TikTok (or whatever) -- HOWEVER, the difference is, the publisher and author have little to no control over a book suddenly going viral "outta nowhere"! IT'S AMAZING AND GREAT when that happens, we can all wish for it and hope for it -- but it feels kind of out of our hands -- whereas things like pre-orders, getting blurbs, yadda yadda, are at least things that the publisher and author have a MODICUM of control over. They can't MAKE people pre-order, but they can TRY at least!

Do publishers just want their investment back ASAP?

That would be great, sure. But profit margins are slim, and many books never earn out. Publishers know that they are probably going to just break even on a lot of books, and lose money on some, and have big hits with a few. I don't think anyone is expecting every book to have massive pre-orders or huge initial sales or whatever else.

Further: Most of this "pressure" is coming from the authors themselves. Like, the call is coming from inside the house. I've NEVER heard a publisher insist that an author do some enormous pre-order campaign or hit social media relentlessly for months -- actually it's more likely that a publisher in the year of our lord 2024 will say that they don't really think a massive pre-order campaign is worth the effort. I've NEVER heard a publisher say that anything in particular rides on first week sales, or insist that a book must hit a bestseller list. Of course they are hoping for it, it would be great! But it would be foolish for them to say that it WILL or MUST happen, and if it doesn't, it doesn't diminish the author or their efforts in any way. Obviously when award-time comes, publishers AND authors are likely crossing their fingers that a book will get a big shiny medal, and they might be a little disappointed if their book doesn't get one (especially if armchair experts online were predicting that it might) -- but I've NEVER heard a publisher put pressure on an author about that kind of thing, either, if anything, the opposite.

Publishers are, in fact, much more likely to be trying to temper outsize author expectations, rather than stoking them. There might be a few outliers -- huge-name authors where everyone really does expect instant NYT success and glory, so if it doesn't happen for some reason, there's some disappointment all around - but truly? That level of expectation is quite rare, and if you happen to be in that echelon, you probably aren't asking questions like this on Tumblr, you're busy swanning around the Isle of Capri or something. And actually you probably don't feel PRESSURE to hit the list in that case anyway -- you just expect you will as that is normal for you. Bless.

Regular authors? Which is 99% of the authors reading this post? You can go ahead and calm down. We love you regardless of your pre-orders or initial sales. If you feel "enormous pressure" for "instant success" -- really take a look at where that pressure is coming from. Because it's probably not from agents or publishers, who know from long experience that almost no success is "instant" by any stretch of the imagination.

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

*Trigger Warnings for this post discussing self harm and suicide*

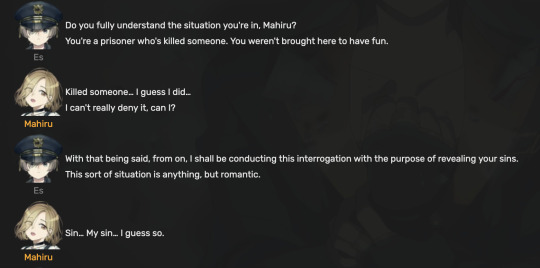

So I was talking with @mgjong about Mahiru, and we noticed a few things regarding her story that I wanted to go more in detail with and highlight! First, I wanted to talk about Mahiru’s behavior during her T1 VD:

Once Es gets to the heart of the conversation and starts reminding Mahiru about her crime, the tone notably shifts here, along with Mahiru’s reaction. Her words are trailing off, her voice is notably more subdued, and of course, she does not deny that she did "kill" someone:

And then, Mahiru changes the subject, with Es even pointing it out and wondering why she’s doing this. The topics she starts talking about are very interesting too:

Mahiru: “So first things first, you should gather up all your courage and be completely transparent about yourself. Doing so will make your partner feel at ease. And they’ll start opening up about themselves more.”

What interesting topics to talk about Mahiru! Communication and transparency? Wanting your partner to open up? Why would you bring up those kinds of things here? Right after Es mentioned your crime? Were you doing it subconsciously because you were reminded of the time when you couldn't do this? Specifically for your boyfriend in mind? I don't know, it's just very interesting how this is the very first topic about love that she brings up in her VD.

Mahiru's bf:

Speaking of her bf, do I think this guy is a saint? No, definitely not. Do I think he’s some asshole who deserved to die? No, I don’t think that either. To me, the bf is just another guy. He’s human, and he failed to communicate his boundaries with Mahiru, which contributed to their conflict.

Clearly, we don’t know much about this guy, outside of Mahiru’s perception of him, but here’s how I personally interpret this guy and the role he plays in Mahiru’s story:

1. Mahiru's bf was just someone who failed to communicate and establish his boundaries with Mahiru, with his mental health getting worse as time went on for their relationship.

2. Mahiru's bf had his own mental health and self-harm issues before he had met Mahiru, which were made worse because of their relationship.

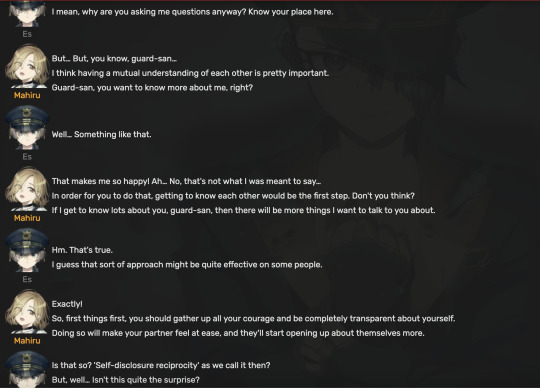

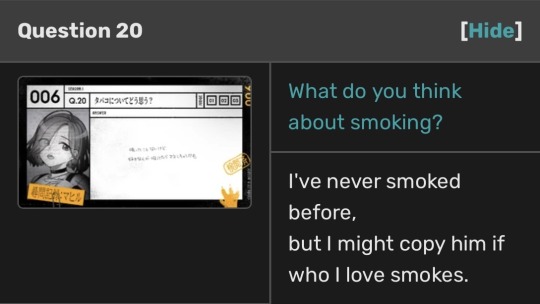

I don't think these two options have to be mutually exclusive either. But I do think there's a bit of evidence that points to her bf having mental health issues before. In one of the magazine scans in TIHTBILWY and in Q16 of her T2 interrogation, Mahiru notes that she met her bf on the university terrace, which seems innocuous enough with how Mahiru describes it:

From user @shima1408 on YouTube:

But in ILY, Mahiru's bf has also been shown to have blood on his clothing while both of them are in the forest. It is possible that he could've gotten injured while they were walking through the forest, but more importantly, Mahiru does not have any blood on her clothing. Why is Mahiru the one not injured then, but her bf is? Did he inflict those wounds on himself? Why was he on the university terrace that fateful day he and Mahiru met? Did he fall in love with Mahiru because he thought she was the one? A fated partner who stopped him on that day and could give him another chance at a happy life?

So I do think it's a possibility that this guy had mental health problems before he had met Mahiru, which she inevitably made worse due to her love. He literally could’ve just been on the terrace chilling, but the meeting detail is still pretty odd to point out. It also stands out from all of Mahiru’s existing fluff dialogue and romanticization of the event and is even noted again in an interrogation question in T2, despite having been mentioned before.

But regardless of whether or not he did, Mahiru did not recognize how her love caused a strain on her bf's mental health. So when Mahiru became more obsessive and overbearing as time went on, as well as her bf not being able to communicate his needs and establish those boundaries with her, they both ended up being mutually toxic to each other as a result of this miscommunication.

Again, this is why I think she continued to emphasize “getting to know the other person better” and “being transparent” to Es in her T1 VD, because she had failed to do this with her bf before. Not only did she change the subject to avoid talking about her sin, but she also switched to a topic she knew deep down she failed to do with her bf, so she ends up compensating for it through her conversation with Es.

Cake:

The cake in ILY obviously represents love, but it also represents hurt and pain (as shown with how Mahiru feeds the cake/rat to her bf). Because both of them are shown to be feeding the cake to each other, it shows that in this conflict, blame cannot be placed on one or the other entirely. They had both failed in the relationship, despite genuinely loving each other.

Mahiru's bf feeds her a small piece, which she takes happily. He's careful with it, making sure the piece doesn't fall it to the ground. An important thing to note: Mahiru eats the slice willingly (Mahiru is so willing to accept that pain too, huh?), and her bf does not force her to eat it:

But Mahiru gives him a much bigger piece with no hesitation. Because she thinks that's what he wants. She thinks that more of her love will help quell his exhaustion, his pain. So she feeds him a bigger, more overwhelming slice of cake. She's careless, and the slice could fall so easily. And what does she do? Force her bf to eat the cake. She does not give him a choice to not accept it.

Suicide:

Now to the main setting in ILY: it’s a literal forest, which seems to allude to the Aokigahara Forest aka the "Suicide Forest" as it's known for in real life. We know that Mahiru's bf died from suicide based on ILY and the Undercover shot where he's missing his shoe, but we still don't know the reason why Mahiru was shown to be with him before his suicide. This leads me into thinking two possible scenarios on what possibly happened:

1: Mahiru’s bf was planning to kill himself, and Mahiru somehow found out about it and tried to join him, but had failed in doing so.

2: Both Mahiru and her bf were planning a "shinjū" (lover’s suicide) together, with Mahiru being unsuccessful with the attempt.

I am leaning more towards possibility #2 because of how it would fit in with Mahiru’s tendency to "share pain" as something she views as love. Since the lover's suicide is a concept that matches this sort of thing, I wouldn't put it past Mahiru and her bf to go along with this idea, and it was just that Mahiru was the one who survived this while her bf did not. Lover's suicides are also a thing common in literature, so it's definitely something Mahiru would find and know about given her literature and romance novel associations.

Other interesting details pointing to this in ILY: Mahiru's bow around her neck and the way it is here in ILY is very odd, like it’s supposed to be some kind of noose around her neck. It doesn’t even seem like it can normally come undone like that while they were trekking through the forest, especially since the bow itself is usually fastened and tied up neatly in the outfit she wears with it:

Mahiru is also shown to be barefoot, which doesn’t make a whole lot of sense? Why are you barefoot like your bf is, Mahiru? What is the reason for matching with your bf, who is about to commit suicide in this forest? Were you going to go along with him? Why were you even there in the first place, Mahiru?

Both of these theories could still work though! Whether it be them planning the suicide from the start, or her joining in willingly, I think both of these examples highlight how much little self-regard Mahiru has for her own life. Mahiru has established that she would do anything her lover does (including harmful behaviors such as smoking), and she would do anything for love itself at that. Mahiru would continue to endanger herself if it was for the sake of love, so it doesn't seem too far fetched that she would go along with something so extreme and life ending at that:

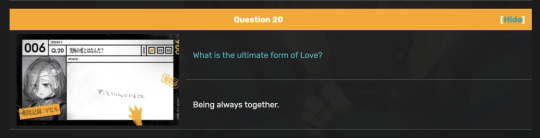

And what else does Mahiru say about love, the ultimate form of it? Being always together. Lover's suicides are often done with the intent of being reunited again in heaven and in the next life. A method such as this would definitely help Mahiru and her bf be together forever, right?

How interesting though, that she still does not quite understand why her bf isn't here anymore. Isn't the ultimate form of love always being together? So why then, is he not here anymore? She knows she’s responsible, that she had done something wrong.

But she was just showing her love. And yet, just why?

Why is he not here anymore?

#but yeah most of this is just scattered thoughts so dkfjdfnl#I wanted to finish this because of all the Mappi posting today#with her sheltered life could've contributing to her extremely low self-worth and perpetuating the cycle of being trapped#both for herself and for others who she loves#tw self harm#tw suicide#milgram#mahiru shiina#rose.txt

63 notes

·

View notes

Note

Marinette stan will always make up weird and non sensical reason to excuses her wrong doing, be it disability, doesn't know, she doesn't mean it, she's too stressed, etc. and I've been wondering for a loooooong time why they're so... Hell bend make an excuses to justify Marinette bad behaviour, like you can like a character and admit they made mistake and hurt others, not like those two are mutually exclusive anyway. But here we are...

Though someone I know on Twitter told me this kind of behavior, where they defend their favorite character while they attacking real human over it, has something to do with the fact that this behavior stemmed from the fact that that person see the character not as a character but rather the extension of themselves, that's why they will bend heaven and earth just to justify their favorite character mistake because for them the attack to their favorite is like a personal attack to them. I thought that was exaggeration but after seeing how Marinette stan doing this it become make senses.

---

I've noticed that Marinette stans always have an excuse at the ready, either for Marinette's behavior or their own. It is fitting, if we run with the idea that most of these people project a lot onto Marinette and view Marinette as an extension of themselves. They think Marinette is actually being mistrated by the other characters in the show, the writers and the fandom at large, because they're that dedicated to projecting their own underdog fantasies on her. Of course they treat anything criticizing her as a personal attack if they view Marinette that closely to their own sense of self, which explains why they think it's totally okay to act completely unreasonably over online arguments they themselves start; they think they're the underdogs rising up against the Chloés of the internet or something.

Like, the Maybe-a-Sockpuppet-Maybe-Not person went on to send private harrassment to the people on that reblog chain where we made it clear that Marinette should not, in fact, be trusted around other people's relationships based on things seen in the actual show. Because that's a completely reasonable reaction to getting clowned on on tumblr of all social media sites, and they dared to act like they were the victim when they were the one to resort to actual harrassment.

Every time I've seen harrassment in this fandom it's been done by Marinette stans "defending" their favorite character from people "bullying" her. Scratch a Marinette stan picking fights and you'll find a self-entitled victim complex every time.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

death can't keep me apart from you

pairing: aerith gainsborough x gn!reader

summary: you've got the ability to come back from the dead. but how is that ability affecting your relationship with aerith?

tags: fluff & angst, strangers to friends to lovers, death & revival, aerith worries about your future together, spoilerfree

the first time you met aerith you died in her arms.

you had crashed through the roof of the church in the slums, right onto the flower field. aerith held you in her arms, begging you to stay with her. she didn't even know you, yet she couldn't stand seeing you die. she cried bitterly, your death taking a huge toll on her.

and then the next day, you walked through the door of the church, as if nothing had happened. as if aerith hadn't seen you die, hadn't felt how your heart stopped beating and hadn't carried your lifeless body outside to bury you.

“i remember you.”

those were the words you greeted her with. aerith was too stunned to speak, but you seemed well enough to do the talking.

“i must've startled you quite a bit yesterday. i'm sorry for that” you said, as you stepped closer, kneeling down next to flowers. “i hope the flowers are still well…”

aerith was fascinated by you. at first, she feared you too. after all, you had come back from the dead, with death leaving seemingly no lasting effects on you. but as soon as the fear faded, aerith knew that she wanted to learn more about you. she wanted to understand what had happened and why. and she wanted to know the person who wielded the power to come back from the dead.

during the following months, you visited aerith quite a few times in the church. as she tended to the flowers, you told her about your life; your upbringing, your interests and, of course, your ability to come back from the dead.

to you, death was more like sleeping. whenever you had died, you awoke again as soon as the clock hit midnight and a new day began. and the day aerith and you first met hadn't been much different.

as the months passed, aerith's fascination with you faded. and in its place, romantic feelings began to blossom. with each visit to the church, the two of you fell deeper in love with one another. until one day, you shared a romantic kiss within the flower field, that marked the start of your relationship.

only a week later, you died once more. this time, aerith wasn't by your side to witness it. she only found out about your death when you told her about it during your next visit to the church.

“how can you be so calm about this?” aerith had scolded you, with tears in her eyes, as you casually mentioned your last death. “what if you hadn't come back this time? or what if–”

“i'm fine, aerith. i've always been fine. you have nothing to worry about, i promise.”

but aerith had quite a lot to worry about. for one, she worried that you wouldn't come back to her. that perhaps, you had only a few chances to come back from the dead and that you'd eventually run out on those. and then, she'd feel the same way she did that first time you died in her arms; helpless and all alone.

and then there was another worry aerith had. one that wasn't mutually exclusive to the prior one. what if you didn't value your own life? what if that ability to return from the dead was more a curse than a blessing, because it made you forget the value of your own life?

and of course, there was one last thing. if you never died, if you truly were immortal, than you'd outlive everyone around you, including aerith. while she would one day die and return to the lifestream, you'd still be here. and perhaps once aerith would be dead, you'd recognize the value of life. but by then, it would be too late for aerith to witness it…

#aerith gainsborough x reader#aerith x reader#aeris x reader#aeris gainsborough#aeris#aerith#gainsborough#final fantasy x reader#final fantasy 7 x reader#final fantasy 7#final fantasy#ff x reader#ff#ff7#ff7 x reader#x reader#x you#x y/n#x gn reader#fluff#dating#oneshot

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

For realsie though, I really wish I could look at the people who are diagnosed with DID and get upset at people "making it look like a fun disorder to have" with some level of sympathy or empathy, but I really honestly think that rhetoric is really honestly destructive as a means for self soothing and one I really just can't stand personally.

Like this disorder sucks ass and the reason it happened sucks ass and recovering with it sucks ass, but I don't see that rhetoric as any better than stating that "anyone who went through that could NEVER recover or live happy".

And I get where that comes from, I do, but at a certain point in trauma processing, stabilization and recovery, things start to click that trauma is over and PTSD inherently is referencing an event that has already passed. Trauma sucks. Severe chronic trauma SUCKS, but that's the past and - while its a LOT more difficult than it is to just say - that past REALLY doesn't have to define the present even a quarter as much as trauma makes it feel.

Of course, I understand and get those who feel like DID is horrible and a hell disorder - I 10000% understand that and its a valid feeling / opinion / statement to make, but to claim that it is impossible to have fun, be happy, and make casual content and just genuinely make the best out of a shit situation; or to claim that anyone with DID would be totally dysfunctional and miserable and unable to do XYZ - it's just... really self depricating and a huge negative self fulfilling prophecy don't you think? Also not to mention a LOT of projecting?

Other people don't deserve you forcing your self loathing and pain onto them. You are allowed to hate your situation, you are allowed to hate your disorder, you are allowed to feel and think and experience your experiences however you want, but a line is drawn when it comes to displacing that hatred, those feelings, those thoughts, and those experiences onto others and demand that they should meet your standards of misery.

I apologize, but I'm not going to pretend like DID stresses me out when I'm really not stressed by it anymore because most of our regular parts are actually decently connected and coordinated with one another. I'm not scared of them and they aren't scared of me. I'm not fighting them and they aren't fighting me. We got trauma but we also got, ya know, a life going and the trauma gets less and less prevalent and intrusive as time goes on so, life's honestly pretty lit and I really love to see other systems heading in that direction.

I think everyone should aim to be happy and at peace with their disorder. I don't understand, empathize, or support the idea that someone had to meet a standard of misery to be "real".

(TW: suicidal ideation and physical abuse mention)

If I take medication that makes it so I don't scrub my hands raw and have panic attacks over having not eaten a salad "recently" thus meaning I am going to rot from the inside out and die, does that mean I am faking having OCD? If I take medication and improve my life so that I only pluck my hair once a month, is my Trichitillomania faked? If I stop having suicidal ideation, does that mean I was faking being suicidal the whole time? If I stop having bruises, does that mean I faked being beaten as a kid?

(TW cleared)

Recovery and peace should and does not ever invalidate the truth of the pain suffered and the struggle overcome. Happiness and joy can co-exist with the truth of hurt, pain and suffering.

Trying to hold the two as mutually exclusive is a huge part of why a lot of people get stuck being miserable. If misery is vital for honoring your pain as real, it is very hard to let that go and let yourself be happy again, because if you are happy, what will attest to give your pain justice? But pain, justice, misery, and happiness - they can all co-exist and honestly, that's a really important thing to learn and understand in my healing journey as it really opens up doors to letting trauma go.

Your pain doesn't define your truth.

Your truth is your truth.

It will stay true regardless of if the pain persists or leaves.

#alter: riku#ptsd#c-ptsd#cptsd#actuallydid#dissociative identity disorder#ocd#physical abuse mention#recovery#healing#syscourse#discourse

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every once in a while, I come across an Owl House fic in which someone does something romantic/sexual with someone who isn't their established partner, and I see it tagged as "Cheating". Which, in the context of that fic, is almost certainly exactly right!

(I wouldn't know for sure, I don't really read these fics.)

But I can't help but imagine the leadup to this, how this situation comes about in the first place. And wonder how, at no point, did the previously-involved character bring this up to their established partner. And wonder how, at some point, they decided that doing these things with someone who isn't their established partner is bad, and wrong, and "Cheating".

The Boiling Isles were made to have few or none of the usual biases which brought about our cisnormative, heteronormative, amatonormative, allonormative, perisex-normative, etc. society. Some real-world biases remain, like ableism, classism, and (although it's quite different from its real-world counterpart) racism, but they're mostly reserved for the real jerks, not applied on a wider scale. In all, it's an absolute queer haven, and I somehow doubt that polyamory is where they draw the line.

Since the most recent ship I saw with this was Luz/Viney (cheating on established Luz/Amity), let's imagine two scenarios.

Scenario A:

Viney sends Luz some Signals: she wants something romantic and/or sexual from her. Luz, oblivious as she is, doesn't notice the implications until things have already progressed to a certain point with Viney's desparation to get the point across and/or mounting inability to reign in her impulses, so something has already been done, by Viney, to Luz. Stolen kiss, slap on the ass, whatever, doesn't matter. They're impulsive teens, so everything feels like the Most Thing.

Luz talks to Amity about it in a panic, because of COURSE she does, those two are modern media's single most communicative leading ladies. Amity is like "Oh shit, but did she mention me?" because she's also kind of a massive lesbian, and Viney is the triple threat of Confident, Competent, and Chaotic. Even if Amity has no particular feelings for Viney (which is admittedly pretty likely), she must still admit that Viney is a hell of a catch. So far, she has no reason to feel anything but happy for Luz, and doesn't understand why Luz is panicking.

Luz, having grown up in the modern, compulsively monogamous United States, is confused as fuck about Amity's seemingly blase attitude toward this development, and says something like "But isn't that/wouldn't that be cheating???" and Amity is like "What? Cheating how? Who's being cheated out of something? Viney? Me? You?"

'Cause like. Nobody loses. Luz gets to kiss or whatever with Viney and also kiss or whatever with Amity. Nothing about one says she can't do the other. Hell, dating someone who's dating someone is a great way to get to know someone, and a great way to gauge mutual interest, should you ever want to date someone.

Luz predictably brings up that whole weird monogamous people thing with like. Assumed exclusivity, or whatever you call it. And Amity is like "Okay, but I don't own you??? I can't control everything you do and dictate who you can interact with and how, because what the FUCK, that would be super evil and controlling and manipulative and weird. And way too much like something Odalia would do."

And Luz is like "Oh shit. Wow. Polyamory. Awesome. Once I'm done disavowing all notions of infidelity, and figure out my own feelings on the matter, will you hold my hand for moral support as an excuse to come along with me when I get back to Viney about it?"

And Amity is like "Hell yeah. Let's fucking go."

And then they do and maybe something comes of it but who fucking knows or cares because they Communicated. Like they are wont to do.

Sike, actually. I care, and I think Viney/Luz/Amity is AWESOME.

VS

Scenario B:

Viney sends Luz some Signals. Luz reciprocates these signals immediately, despite herself, because she's an impulsive teen, I guess. One thing leads to another, and WHOOPS, now Luz is in some kind of not-strictly-platonic relationship with Viney, even though she was already in such a relationship with Amity.

Luz internally berates herself for her infidelity, all the while still doing said infidelity. She doesn't tell Amity because she's way too deep now, it would ruin the relationship, or something!

Amity finds out anyways and becomes so heartbroken that she breaks up with Luz on the spot and probably drinks herself into a coma or something. I don't know, this isn't really my subgenre.