#not by the actual narrative rather the narrative of their creation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i really wanna do perci + staci redesigns because UGHHH

#sonic#sonic boom#perci the bandicoot#staci the bandicoot#they were doomed by the narrative#not by the actual narrative rather the narrative of their creation#i get that the show's budget was sort of quantity over quality (at least im guessing)#so that's great. 2 new characters and you only have to model + rig them once#but the fact that there is lore behind them while theyre mostly just used to make twins jokes and be extras...#i mean perci does have her own episode. where she isnt being herself for most of it.#but staci is just “perci's twin” and for one episode “manipulative girlfriend”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

baffled at the way people approach character creation. wdym you can take a trope like smug demonguy or muscle mommy and flesh that out into a character you care about without having to mangle 5 already existing characters into it and also throw out the entire concept when you find out something wholly different works infinitely better

#soda.txt#one of my OCs was intended to be butch lesbian werebear#she's still a lesbian but everything else about that concept was thrown out after i gave it actual thought#not because it was bad but because she could not have worked like that in the context of the narrative#she went from a confident loner who didn't give a shit to someone who gives way too many shits and worries way too much#and it works better now in the larger context#my antagonist placeholder trope was tumblr sexyman bait and now they're everything but that#idk i just can't wrap my head around to a trope approach to character creation in terms of character traits#rather than tropes in the sort of roles they're supposed to fill which gives me so much more room to work with

1 note

·

View note

Note

I was going through some of Rowling’s old interviews and came across one in 2004 where she spoke of Sirius:

“I am so proud of the fact that a character, whom I always liked very much, though he never appeared as much more than a brooding presence in the books, has gained a passionate fan-club.”

This wasn’t the only time she expressed surprise that Sirius became a fan favourite, and it’s honestly baffling to me??? He had an entire book named after and primarily revolving around him, and is canonically the closest thing to a parent that Harry, the protagonist of the series, ever had. Even if we disregard everything else we know about Sirius and his storyline, there’s no way in hell he wasn’t going to be popular. If I didn’t know better, I’d have said that a character like that was specifically designed for fan service (I mean...he's hot, has a flying motorbike, and is literally named after a star, lol). It’s bizarre that Rowling seems to have had no idea, and that she believed he was / intended him to be nothing more than a “brooding presence” in the series – which is at any rate an appalling and deeply unsympathetic way to describe his trauma and depression.

It made me think of how there's such a major disconnect between authorial intent and authorial execution when it comes to his character as well, especially in Order of the Phoenix. Characters like Molly or Hermione call him irresponsible/reckless/immature, claim he confused Harry and James, that he treated Harry like a friend rather than a godson, that he was biased against Snape, etc. Rowling’s interviews confirm that she intended to characterize Sirius in such a way and that Hermione and Molly are meant to be viewed as her mouthpieces. But Sirius’s actual behavior and relationship with Harry does not correspond with any of this and his actions + dialogue are for the most part very reasonable and sympathetic. (There’s also Kreacher’s storyline, which made me dislike Sirius a lot when I was younger, but upon my reread comes across as almost entirely nonsensical, contradictory, and seems specifically designed to paint Sirius in a bad light to the point where he’s compared to VOLDEMORT of all people by Hermione - who, in the process of criticizing Sirius, dehumanizes house elves entirely by claiming that none of them are capable of individual morality or have any ethical agency of their own. It's frustrating because she's 100% right that house elves should be freed but the way she infantalizes them is...pretty shitty and not the way to go about it. But I digress.)

Rowling seems to have done a complete 180 degree turn on how Sirius is presented by the narrative between Goblet of Fire and Order of the Phoenix, and I can’t really understand why.

I get the sense that the creation of Sirius’s character in particular was, at the very least, partly accidental on Rowling’s part. She didn’t expect him to blow up the way he did, and I get the sense that she doesn’t seem to have been thrilled by how much the early HP fandom liked/valorized him. There was an interview where she was asked if she liked him, and she said that she did, only to immediately list down all his alleged flaws and emphasize that “I do not think he was wholly wonderful” (which character in the series is wholly wonderful, lol? Sirius came across as a great deal better than most to me). There have been so many other interviews where she’s done the same thing despite the fact that Sirius's faults or perceived faults had absolutely nothing to do with the questions at hand. It’s such a startling contrast how she talks about pretty much everyone else from his generation, all of whom she seems considerably warmer and more sympathetic towards in varying degrees.

As I haven’t been back in the fandom for very long, this is the first time I’ve come across her interviews - I’m not sure if I’m reading too much into them or not. I wondered if you agree/disagree, as you’ve been in the fandom for much longer and I love all your metas about the series. Thanks :)

You’ve hit upon my personal Rage Point for the entire series, anon.

I want to start by pointing something out about Sirius and Kreacher, which is that in GoF Sirius tells Ron and Harry (and Hermione, though he brings it up to compliment her observational skills) that Crouch Sr.’s mistreatment of Winky is an indicator of his character. (“If you want to know what a man’s like, take a good look at how he treats his inferiors, not his equals.”) This is, somehow, the same man who one book later is egregiously dismissive of and abusive toward his family’s house-elf, to the point that this dismissal causes his death (oh, and Albus blames him for dying, too.) Despite Sirius expressing two wildly different viewpoints from book to book, we’re intended to take that as his true self, as the authentic expression of his beliefs and position.

I’ve spoken before more than once about other drastic character shifts that happened as a result of the Three Year Summer, both as a writing break and as a paradigm shift in the notoriety of and ubiquity of the series thanks to the movies being released starting in 2001. I was in elementary and middle school while the books were being published, and OotP was the first book I remember seeing large-scale advertisement for in my school outside of a book fair - there was a big larger-than-life poster teasing the book cover with a release date during the summer to get us all hyped up for it. I’d obviously heard of Harry Potter before that, but that was the moment when the books went from “famous book series” to “cultural phenomenon,” at least in my mind. And I think that we can trace this shift in opinion on Sirius Black back to the Three Year Summer, too.

In my opinion it’s obvious that Joanne really liked Sirius, when she first developed him. I don’t think she’s telling the truth when she says she doesn’t think he’s wholly wonderful - when she first came up with him she absolutely did. He’s got pride of place as a Cool Character in all the ways she loves to lavish attention on someone. He’s set up with a phenomenal entrance in PS chapter one and then he spends all of PoA in the spotlight. He has a dramatic reveal of his true allegiances and his innocence, and he’s Harry’s best and most supportive parental figure throughout GoF who consistently gives good advice and who risks his own life and liberty to make sure his godson is safe. He considers coming back to England and living in a cave and eating rats to be his duty as a godfather, and while Harry feels responsible for his circumstances he’s always really clear that he (1. doesn’t care about the risks to his health and safety (2. will gladly sacrifice comfort and stability if it means being able to protect this boy (3. will not let Harry feel guilty.

These aren’t the actions of a man who confuses Harry with James - throughout GoF he continues to insist that his decisions are his own, made as an adult trying to parent and support a kid who desperately needs a stable presence in his life. Harry’s used to taking the blame for the actions of adults (my heart is still rent asunder by his expectation that Lupin is going to gaslight him about denying him the chance to face the boggart in their first DADA lesson) and he’s also used to feeling like he has to manage the emotional state of a household (see: all the times he plans out what to say or not to say to the Dursleys to get them to do what he wants), and Sirius doesn’t let him sink into either of those pits. He also prevents Harry from bottling up his feelings or concealing his distress, and never lies or twists the truth. He’s being very deliberately written as someone who serves as a positive role model and positive mentor figure for Harry, and then suddenly come OotP he’s moody and immature and subject to a number of very strange smear campaigns from characters the author confirms are intended to reflect her real opinions.

So… what happened, over the course of the Three Year Summer, to make her change her mind? We can’t ever know for sure, obviously, because Joanne hasn’t ever bothered to lay out how her feelings on each member of her cast changed and evolved, and she’s unlikely to do so at any point in the future because now when people talk to her they mostly talk to her about transphobia. But I have a theory.

See, between 1998 and 2003, the HMS Wolfstar set sail. While most of the seminal meta came out after OotP (see “The Case for R/S” as probably the one I and others my age are most familiar with as an introduction to the ship) and most of the really famous fanfics started trickling out around that time (The Shoebox Project started in 2004), there were fanfics before that point, a growing fan community, and a number of pieces of fanart and fancomics (check out the list of doujinshi in the linked Fanlore article, some of those date back to 2001). Edit: here is an archived humorous/gently snarky list of Wolfstar fanfic tropes created in 2002 - while I can’t personally remember the names of fics from before 2004 or so I want to point to this as evidence that there was an established fan community, even using the “WolfStar” name, prior to the publication of OotP.

Normally, I wouldn’t think that fanfic from prior to 2010 or so had much of anything to do with the author’s opinions on their work, because norms and fan culture around fanfic were much more focused around keeping these stories private and away from the prying eyes of The Powers That Be/TPTB.

I say normally, because Joanne was aware of fanfiction, and aware of fanfiction remarkably early in her career as a public figure.

Younger fans are almost certainly not going to know this, but one of the first real fandom divides in HP had to do with fanfiction, and specifically the question of how to treat fanfiction written by and for adults that featured sex scenes or other mature content. Since the books were children’s books (though there was an adult fandom since the start, especially online - the Harry Potter For Grown-Ups/HP4GU mailing list and its descendant communities still loom large in fan history as some of the early pillars of today’s digital scene) a lot of people didn’t know what to do or how to treat fanfic. This was also compounded by fanfic being a lot more subject to legal action or takedown notices - Anne Rice, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, and Anne McCaffrey all became infamous either for pursuing individual authors and archives until they took down their stories or instituting guidelines about what kinds of transformative works were acceptable, or both in McCaffrey’s case.

Rowling, however, was different. Rowling said that noncommercial fanfic was completely fine, that she wasn’t going to pursue any kind of legal action against fanfic authors, and that as long as adult-oriented fanfic was appropriately warned for and not shown to or targeted to children, she didn’t care if it existed.

This laid the groundwork for the founding of Fanfiction.net, for fanfic communities on LiveJournal, and eventually for Archive of our Own and the Organization for Transformative Works. In an era where legal disclaimers were common on fanfics as a mostly-useless attempt to prevent being shut down by IP holders, Rowling threw the doors open and democratized her stories in a way she - I would argue - ultimately came to regret.

I can’t prove that her sudden slander of Sirius was a result of latent unexamined homophobia and a desire for revenge against the fandom for daring to claim one of her favorite characters as a gay man. I can’t prove that his backstory of being kicked out of his house (for unspoken Family Drama reasons centering around him being filthy and disgraceful) only to be shoved back into it, or Trustworthy Adults suddenly painting him as dangerous to children and inherently irresponsible and reckless, or all of his trauma being ignored and painted over, or every scrap of his heroism being erased, has to do with Joanne deciding that if we’ve made him gay he shouldn’t get to be a character anymore.

I can’t prove it.

But I do believe it. I believe it because when you ask yourself “is this queercoded character being subjected to authorial homophobia”, suddenly everything about Sirius’s arc in OotP makes complete and total sense in the worst way possible. This is also why I think Tonks and Remus were paired off, why Tonks suddenly becomes more gender-conforming, and why Bill Weasley transforms into Normal Settled-Down Hetero William. It feels like her desperate attempts to take her characters and shove them back into a box that she controls. I don’t think she was at that point consciously and virulently homophobic, but I think her clear and evident discomfort with fans interpreting these characters who she wanted to be straight comes through in her writing.

I also believe it because she does the same thing to Albus, after his death. Someone who’s been uncomplicatedly heroic and praised by all parties and even used as her mouthpiece to pass judgment on Sirius suddenly becomes morally suspect and untrustworthy and shady and secretive, with enemies lining up as soon as he’s dead to slander him - and again, just like with Sirius, we’re meant to accept this as the correct version of events. He even confirms all of this to Harry himself in the King’s Cross afterlife. The old Albus can’t come to the phone right now, he’s dead, and only his critics remain. Coincidentally, Albus is of course the only confirmed gay character in the entire story. Funny how that works out, isn’t it?

I’ve been angry at her for 20 years for killing Sirius, and angrier still at her straightwashing efforts. I wouldn’t believe her if she said she wasn’t doing that, at this point.

It’s not as if I expected her to be a perfect ally as a center-left moderate cishet white woman in the late 90s/early 2000s, and I do think that Dumbledore being gay was revolutionary in a way that most modern audiences seriously fail to appreciate, but I wish she wasn’t so damned insistent that no one else could be queer in any way at any point. She’s also really evidently uncomfortable about any displays of affection between confirmed same-sex pairings - she was absolutely neurotic about the amount of physical contact between Mads Mikkelsen and Jude Law during FB3, to the point that she fought with David Yates about it. And her behavior contributed to the intense homophobia I and others experienced in our formative early years in fandom - no-slash mailing lists and archives, the immediate classification of all queer fanfic as inherently more mature or more sexual simply by virtue of having queer people in it, Wizards For Bush, etc. As a result, boycott or no boycott, I hope that Wolfstar is canon in the new series, I hope Mundungus stays the crossdressing icon that they are, I hope Tonks is canonically nonbinary, and I hope Joanne loses sleep over it.

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's this idea floating around the general TTRPG space that's kind of hard to put one's finger on which I think is best articulated as "the purpose of an RPG is to produce a conventionally shaped satisfying narrative," and in this context I mean RPG as not just the game as it exists in the book but the act of play itself.

And this isn't exactly a new thing: since time immemorial people have tried to force TTRPGs to produce traditional narratives for them, often to be disappointed. I also feel this was behind a lot of the discussion that emerged from the Forge and that informed the first "narrativist" RPGs (I'm only using the word here as a shorthand: I don't think the GNS taxonomy is very useful as more than a shibboleth): that at least for some TTRPGs the creation of a story was the primary goal (heck, some of them even called themselves Storytelling games), but since those games when played as written actually ended up resisting narrative convention they were on some level dysfunctional for that purpose.

There's some truth to this but also a lot of nuance: when you get down to the roots of the hobby, the purpose of a game of D&D wasn't the production of a narrative. It was to imagine a guy and put that guy in situations, as primarily a game that challenged the player. The production of a narrative was secondary and entirely emergent.

But in the eighties you basically get the first generation of players without the background from wargames, whose impressions of RPGs aren't colored by the assumption that "it's kind of like a wargame but you only control one guy." And you start getting lots of RPGs, some of which specifically try to model specific types of stories. But because the medium is still new the tools used to achieve those stories are sometimes inelegant (even though people see the potential for telling lots of stories using the medium, they are still largely letting their designs be informed by the "wargame where you only control one guy" types of game) and players and designers alike start to realize that these systems need a bit of help to nudge the games in the direction of a satisfying narrative. Games start having lots of advice not only from the point of view of the administrative point of view of refereeing a game, but also from the point of view of treating the GM as a storyteller whose purpose is to sometimes give the rules a bit of a nudge to make the story go a certain way. What you ultimately get is Vampire: the Masquerade, which while a paradigm shift for its time is still ultimately a D&D ass game that wants to be used for the sake of telling a conventional narrative, so you get a lot of explicit advice to ignore the systems when they don't produce a satisfying story.

Anyway, the point is that in some games the production of a satisfying narrative isn't a primary design goal even when the game itself tries to portray itself as such.

But what you also get is this idea that since the production of a satisfying narrative is seen as the goal of these games (even though it isn't necessarily so), if a game (as in the act of play) doesn't produce a satisfying narrative, then the game itself must be somehow dysfunctional.

A lot of people are willing to blame this on players: the GM isn't doing enough work, a good GM can tell a good story with any system, your players aren't engaging with the game properly, your players are bad if they don't see the point in telling a greater story. When the real culprit might actually be the game system itself, or rather a misalignment between the group's desired fiction and the type of fiction that the game produces. And when players end up misidentifying what is actually an issue their group has with the system as a player issue, you end up with unhappy players fighting against the type of narrative the game itself wants to tell.

I don't think an RPG is dysfunctional even if it doesn't produce a conventionally shaped, satisfying narrative, because while I do think the act of play inevitably ends up creating an emergent narrative, that emergent narrative conforming to conventions of storytelling isn't always the primary goal of play. Conversely, a game whose systems have been built to facilitate the production of a narrative that conforms to conventions of storytelling or emulates some genre well is also hella good. But regardless, there's a lot to be said for playing games the way the games themselves present themselves as.

Your traditional challenge-based dungeon game might not produce a conventionally satisfying narrative and that's okay and it's not your or any of your players' fault. The production of a conventionally satisfying narrative as an emergent function of play was never a design goal when that challenge-based dungeon game was being made.

485 notes

·

View notes

Text

✦ ─ ˗ˋ RATIONAL GAZE ˊ˗ ─ ✦

⬨ Summary: Black Sapphire Cookie Tends To Your Wounds

⬨ Character(s): Black Sapphire Cookie (Cookie Run)

⬨ Genre: Headcannons, SFW

⬨ Warning(s): None - Completely Safe!

⬨ Image Credits: @rottenpuppet

★ A bemused sigh—low and velvety—escapes him as he kneels beside you, a stark contrast to the chaos mere moments prior. “My, my,” Black Sapphire Cookie murmurs, deft fingers inspecting your injuries with a mix of amusement and irritation. “Throwing yourself into harm’s way for me? Darling, you must know I live for drama, but this… This is a touch excessive, don’t you think?”

★ His hands, normally so theatrical in their gestures, are uncharacteristically steady as he works. He winds the bandages with slow, precise movements, as if weaving a new narrative between the fabric and your skin. “We can’t have you falling apart so soon,” he muses, lips quivering into a smirk. “Who else would be foolish enough to believe in me so earnestly?”

★ The ever-present glint of amusement in his eyes flickers—just for a moment—as he presses a cool hand against your forehead, assessing your state with an unreadable expression. He doesn’t do sentimentality. He doesn’t do sincerity. And yet, something about you bleeding for his sake leaves an unfamiliar weight in his chest.

★ His microphone floats idly nearby, the eye within it narrowing in something close to disapproval. Even though it seems to know that this moment is different, that Black Sapphire Cookie is not out of calculation, but something far softer. “Don’t look at me like that,” he huffs at his own creation. “I’m merely keeping my most entertaining listener in one piece.”

★ He works efficiently, but his fingers linger. A touch too long here, a brush too soft there. When he finishes, he leans back, examining his handiwork with an expression you can’t quite place. “You’re rather fragile,” he finally says, voice dipping low, almost thoughtful. “But I suppose that only makes your recklessness all the more intriguing.”

★ His wings twitch, his usual grandiose gestures noticeably absent as he tugs at the cuff of his sleeve, gaze flicking toward you, then away. “Try not to make a habit of this,” he says, tone light, but lacking its usual bite. “I wouldn’t want to start thinking you’re actually irreplaceable.”

★ He chuckles, soft and indulgent, when you wince. “Oh, don’t be so dramatic,” he teases, despite the irony of those words coming from him. “A little pain builds character. Besides…” His eyes gleam, mischief returning in full force. “What a thrilling headline this will make. ‘Foolish Cookie Throws Themselves into Danger for an Undeserving Rogue.’ Very compelling.”

★ When he ties the final knot on your bandages, he lifts your hand—gently, unexpectedly so. He presses a fleeting kiss against your knuckles, the gesture mocking, theatrical. And yet, there’s something else there, something softer beneath the act. “A token of my gratitude,” he drawls, as if the words don’t quite sit right on his tongue.

★ As he helps you up, one arm slipping around your waist with practiced ease, he clicks his tongue. “You’ve given me quite the predicament, dearheart,” he sighs. “Now, if anyone asks, should I say you’re my reckless protector, or simply a tragic fool? Ah, what a choice… Perhaps I should let the rumors decide.”

★ Later, when the night is quiet and the fire of battle has dimmed, you catch him watching you—just for a second, just long enough for you to know that despite all his teasing, his flourishes, his carefully crafted persona… Something about the sight of you wounded unsettled him. “Rest,” he finally says, tone quieter than before. “I need you well. After all, who else would be foolish enough to keep me in check?”

#imagine blog#imagine#ask blog#writers on tumblr#headcanon#asks open#ask box open#black sapphire cookie#black sapphire crk#cookie run x y/n#cookie run x you#cookie run x reader#crk#cookie run kingdom#cr kingdom#crk x reader#crk x you#crk x y/n#crk headcanons#black sapphire x reader#writeblr#writing community#cookie run fandom#x reader#sfw headcanons#writerscommunity#writblr#writing#cookie run ovenbreak#cookie run black sapphire cookie

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

As I’ve alluded to, I think a lot of the failures of c3 can be traced to the fundamental gap that, in a plot where so much revolved around “”the gods”” CR never answers the question:

What the fuck is a god?

Others have made excellent points in how we talk about epic fantasy and the difficulties in fully receiving a world where gods definitively exist. What's interesting to me is that, if you really want to get deep into the philosophical weeds (and I always do), then what does it actually mean when we say "gods exist" in Critical Role?

Disclaimer: this isn't exactly as comprehensive as I would like but what I hoped to articulate in one meta post is more like 2-5 thesis proposals in a trench coat, and I still want the catharsis of yeeting my thoughts into the void so I can finally take a nap. I tried to limit the academia of it all but there's still plenty of jargon, and also a bibliography because I like to show my work.

Short version: Godhood/divinity is a semantic lacuna in the CR's worldbuilding. That's not a bad thing, in fact it's kind of necessary. The problem arises when the plot makes gods and godhood a central problem without resolving or even acknowledging the barriers to understanding those concepts, thus leading to hours of dialogue, plot beats, and a supposedly climactic resolution which all amount to nonsense if you look too closely.

As anyone who’s so much as dipped a toe into philosophy will tell you, you gotta define your usage of terms or the discussion is DOA. On all levels of CR text, words like "god"/"the gods"/"divine"/"deity"/etc. are used interchangeably in so many contexts, and the meaning of those terms is only accessible via contextual implication, and the deducible meanings in so many of those contexts directly contradict each other. C3 especially reveals a dissonance between how the mytho-cultural text approaches divinity compared to the contours drawn by the mechanico-ontological text.1

The former in Exandria refers to "the gods" in terms of the Pantheon, a definite collection of individual entities. These otherworldly beings of Tengar, a realm of pure possibility. But "god" is also a rank within D&D's cosmic taxonomy—a rank to which, in Exandria, other entities can rise via the Rites of Ascension. The Matron is a god same as the others; Tharizdun is part of the pantheon but separate, not of Tengar. Maybe a "god," maybe not?

In the mytho-cultural role "the gods" play in Exandria, their being-qua-being is positioned as necessarily plurally defined and unknowable, but nevertheless possessed of immense "cosmic power" befitting their role in the Creation myth and ongoing worship. It makes perfect sense that the in-world mythology is (intentionally) plural and contradictory. However, as others have pointed out,* Exandria's socio-political and cultural worldbuilding vis a vis religion are (less intentionally, I would imagine) rather underbaked, leaving significant gaps in our understanding of what the gods (and religion) mean for the cultural part of mytho-cultural.

Now let’s get into the latter. Because CR isn't just a narrative—it's a ludonarrative, and the game mechanics have huge ontological implications.1

In the mechanico-ontological sphere, the gods are positioned as sort of exceptions to the rule, by which I mean, like, we don't get stat blocks for deities. Which again, on its own, makes perfect sense! D&D focalizes the PCs, and so on the purely mechanical level, gods/the divine are subordinate, acting only through proxies. This is necessary for the game-narrative D&D supports. Giving god-level power explicit stats would be a catch-22:

first, it would severely demystify "cosmic power"—to define is to limit, after all. Not doing so can imply an ontology where gods are not confined by mechanics—their powers go beyond, their powers are not only unwritten but unwriteable.

secondly, if the rulebooks were to even attempt codifying mechanical abilities on par with the semantic associations of “god-level” power, then it would be very difficult to maintain either the PCs focal role as agents of the narrative or a fairly balanced game, much less both. We saw this play out in Downfall—the point of the mechanics in the final battle outlined the huge disparity between mortals and gods.

Speaking of Downfall—as well as their mechanic and mythic existences, the gods also exist on the narrative level as characters. As such, we must necessarily consider questions of agency and consciousness in qualifying their existence, but fuck if that isn’t a messy question on the one layer, let alone putting it in the contexts of these shifting, intersecting layers.2 Keeping it brief though, the gods’ narrative agency is subject to similar issues as their mechanical powers.**

Being an exception to the rules of mechanico-ontological existence only holds together so long as divinity remains separate from everything governed by mechanics when mobilized in a narrative. I'm not trying to nitpick—Matt's "NPCs are not governed by the same rules as PCs" MO isn't automatically world-logic breaking, and there's a degree of pedantry on that front that is simply unsportsmanlike. But the problem in c3 specifically is that the plot focalizes the gods and divinity as a construct in such a way that invites—demands even—closer inspection. And the coherence between the structural layers of the narrative breaks down quite quickly under this scrutiny.

It's not like c3 brought this theme out of nowhere. Disproving that there is any essential divide between gods and mortals defines the zeitgeist of the Age of Arcanum. The Matron’s ascension proves that, however the difference is defined, the state of being one or the other is traversable. Exu: Calamity brought this up plenty: Laerryn contends that the distinction is access to the Celestial plane, and seeks to dissolve the difference by achieving large-scale interplanar travel for all of Avalir; Zerxus embodies that so called "divine magic" is not strictly tied to a worshipful relationship with a deity.

In c2, god-or-not is a huge element of Jester's arc with the Traveler. Her build shows that, despite the very different class abilities/powers of warlocks and clerics, there is no mechanico-ontological constraining the distinction between a warlock patron and a god. These are roles defined through a relational existence, not in keeping with any essential taxonomy of substances.1 The Traveller’s position in the cosmic taxonomy as an Archfey has less bearing on the type of magic he can grant than the belief and conviction on the side of the grantee. Similarly, there’s the Luxon in all its mystery—a god but not a pantheon deity? Divine but not a god? The semantics seem less and less significant.

Now’s probably a good time to remember that CR is a story, and stories are representative constructions wherein any logic other than narrative logic is secondary. D&D as a story engine allows fictional representation to evoke a unique facsimile of materialism because the diegetic laws of physics are established in such detail via mechanics. But still, in a fictional world, metaphysics kind of are physics, and also kind of are semiotics, and both answer to the symbolic. It's fun (for me) to dig into the worldbuilding using philosophy as a framework, but at the end of the day, it doesn't matter if the philosophy finds gaps so long as the rest of the narrative elements cohere around those gaps.

In c3, they do not.

Next to c3, c1 gets the closest to leaning too hard against the logical house-of-cards making up cosmic ontology in Exandria due to the importance of the Divine Gate in defeating proto-god Vecna. The Divine Gate is, imo, the material nexus point where all the semantic and ontological contradictions coalesce: it was created so as to specifically block gods from traversing out of the Celestial plane, but is permeable to mortals. Presumably there is some quality or essential substance that decides who can move through it and who can’t—but what is that? What is the substance of divinity, not in the ontological sense but in the materialism of arcana? It’s not something exclusive to denizens of Tengar, because the Matron is also trapped; perhaps “divine” is a misnomer, and it only traps the specific entities designated at the time of its creation, regardless of any shared essential quality? Except no, because Vecna was able to be trapped behind it as well.

On the flip side, the great thing about the Divine Gate is that it encompasses and narratively justifies that catch-22 of divine mechanics by adding the element of time. The gods used to be un-writably powerful Pre-Divergence, hence their cosmic standing, but the Divine Gate limits their powers of acting in the present, allowing for their mechanical impotence. The Divergence and the Divine Gate incorporate the gods’ disparate ontological states into the history of Exandria, a physical and temporal division that allows for these contradictions to coexist in separate corners of the narrative.***

This coheres throughout campaigns 1 and 2—even when c1 started approaching concepts of “divinity” more closely, the plot maintains a separation between mortal stakes and divine stakes. Vecna was Vox Machina’s problem because he posed a threat to mortals; he posed a threat to mortals because he was seeking to achieve god-level power on the mortal plane. We don’t need to know what the “power” exactly means to know it would be a huge imbalance. The threat is nullified by trapping Vecna behind the Divine Gate. We still don’t know what he is vis a vis godhood, but we do know his powers of acting and affecting on the Material Plane are curtailed and as such he’s not mortal’s problem anymore. Compare this to the Bell’s Hells attitudes towards their joint BBEGs of Ludinus and Predathos. Ludinus is the threat on the Material Plane; for much of the campaign, BH cap off cyclical debates on the gods by agreeing that stopping Ludinus is their actionable concern. In the end, however, Ludinus’ rhetoric succeeds in focalizing cosmic concerns: the narrative concludes with the resolution to the questions of ‘what to do about the gods and Predathos,’ reifying Ludinus’ view that the cosmic structure was a problem to be solved (despite the complete lack of supporting evidence to that point). Meanwhile the resolution to the—previously central—question of ‘what to do about Ludinus’ is ‘leave him to his cottage-core Thanos epilogue,’ as though he is not nor has he ever been a primary source of conflict.

I think Predathos is where the irreconcilability of material substance and ontological substance really start to chip away at the foundations of narrative coherence. The “God-eater” must be subject to the same questions re: “so what do you mean by god?” The takeaway is that the Predathos lore is frankly a hot mess of ludonarrative dissonance—perfect illustration for the other side of that catch-22 I was talking about!

In theory, Matt could have introduced Predathos into Exandrian cosmology without it becoming a narrative problem, had it remained at a sufficient distance from the immediate plot to sit comfortably obscured in the same miasma of metaphysical unknowns as the Luxon or Tharizdun. It’s Ludinus and all the discussion surrounding these cosmic entities that shines a glaring spotlight on the contradictions by way of placing the gods into an ethical framework and using that judgement as a basis for praxis. Moral philosophy is not my area, but as far as it intersects with ontology: it is, to put it mildly, very fucking hard to put a subject under ethical judgement when said subject has no defined being as such that it’s very subjecthood is in question.

What I’m trying to say is that you hold a guy in a very different ethical standing than the sun. The Dawnfather is both and can be reduced to neither. He is a character in a narrative with agency and personality and relationships at the same time he is a mechanical construction that has no independent existence and extremely limited powers of acting, and all the while he is semantically presumed all-powerful.

*I can’t find the post now to link it but I’m 99% sure it was by @utilitycaster

**For an illustration of (non-game) narratives where a pantheon of gods explicitly exist, are in possession of a certain cosmic power, and are direct narrative agents, see: Homer. I ran out of steam before getting to the full comparison I wanted to make, maybe I’ll get to that in another post, but trust me when I say it has massive implications—like, ‘requires a totally different method of engagement with the work, one which heavily departs from, and at times directly contradicts, literary and pedagogical tradition since at least the early modern period’-level implications.

***In terms of Pre-Divergence depictions, frankly I need to finish rewatching both Calamity and Downfall (possibly multiple times) to properly incorporate Brennan’s contributions to the text into this consideration. Drive-by assessment though, as it pertains to the main campaigns: we see glimpses of what the gods powers of acting can be without the Divine Gate, both with Asmodeus at the end of Calamity and the final battle in Downfall, to use as a comparison. These are useful for when c3 brings up the possibility for an alternate state of affairs while providing no examples for what those alternatives would entail.

1. Bryant, Levi R. “Substantial Powers, Active Affects: The Intentionality of Objects.” Deleuze Studies 6, no. 4 (2012): 529–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45332014.

2. The structuralism I’m employing follows a number of works and theorists, namely Roland Barthes for lit theory and Richard Schechner for performance theory; the most relevant direct citation is Daniel McKay’s book The Fantasy Role-Playing Game: A New Performing Art (2001), which references both of the above and many others.

#critrole#c3#don't mind me#I'm actually furious that tumblr formatting won't let me do superscript footnotes#cr discourse#anyway cheers to Divergence tonight I will certainly be watching with this lens on standby

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s my birthday, so I’m taking the chance to spread my agenda! ^^

Do you remember what the scribe of Enkanomiya said? “The Primordial One may have been Phanes.” Wouldn’t that confusion be understandable if Phanes both was and wasn’t the Primordial One? Or rather, if was just one part of the Primordial One, aka his soul?

I will argue that Venti is Phanes, and also two things about Phanes (that are technically their own theory):

Phanes is the soul of the Primordial One, just like what Cocouik was to Ochkan

Phanes was created through the Chemical Marriage between the Primordial One and Istaroth

Yes, I am coming back with a refined version of my old “Venti is Phanes” theory, after studying and organizing my thoughts and what I knew about the lore. The old post was pretty messy.

(I actually spent weeks preparing posts about other aspects of the lore, but meanwhile we got the moons web event that kinda ruined my time to shine, along with some leaked artifacts that basically confirmed much of what I was theorizing about, so I missed my opportunity and the things I was about to bring up won’t feel as special anymore. To feel a bit better, I decided to go back to my true agenda - Venti brainrot, that is. But I will still incorporate important lore parts that I studied into this post, and expand on them properly over time.)

✦•······················•✦•······················•✦

Section 1: What is Phanes? 2 theories:

First, let me remind you of what the book Before Sun and Moon says:

“The Primordial One may have been Phanes. It had wings and a crown, and was birthed from an egg, androgynous in nature. But for the world to be created, the egg's shell had to be broken. However, Phanes, the Primordial One, used the eggshell to separate the "universe" and the "microcosm of the world."”

The next theories about Phanes, that I will present next followed by connecting it with Venti, may be true at the same time:

» Theory 1: Phanes was born from a Chemical Marriage between the Primordial One and Istaroth

Many ties between the PO and Istaroth are obvious, not just because she was very very likely a Shade, but also because she was probably the Moon-themed White Queen to the PO’s Sun-themed Red King, who joined in a Chemical Marriage. That produced the egg/pearl/wtv that birthed Phanes, necessary to the creation of the world.

Please notice that there is evidence that, at some point, Istaroth was the Ancient Seelie who married the Traveler from Afar, but that is not incompatible with the fact that she was bound to the PO first. In fact, I think that the fact that she was likely the Ancient Seelie is a crucial aspect, especially given the crown that she dropped, which in turn was probably the golden-ring artifact created by the Rhine Maidens / moons who confered power to the PO. I have posts about that on the way.

Let me explain. I will summarize what a chemical marriage is (I will eventually make a post fully dedicated to this concept, and to show in detail why all the pairs I mention from genshin fit this doomed narrative).

The chemical marriage / chemical wedding is a concept in alchemy that represents an union of opposites: male and female, sun and moon, gold and silver, sulphur and mercury, body and spirit, red King and white Queen. DON’T mistake this with actual marriages or ship stuff, btw.

It’s meant to produce a new and improved product, the Rebis (an androgynous being, sometimes called the Philosopher’s child), or according to some tales, the Philosopher's Stone. That stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver.

(I can’t help but recall that Venus/the morning star, aka Istaroth, in Chinese, is called Jīn-xīng (金星), the golden planet of the metal element - and Istaroth and her rhine maidens/moons/fates are likely responsible for the golden ring/crown mentioned in the drama Der Ring des Nibelungen.)

According to Jakob, the Seal of Chymical Marriage can be used to seal off the source of life, aka the Primordial Sea, which sounds similar to creating a world/pearl/philosopher’s stone/egg/dream bubble that floats in the sea of quanta or wtv is the logic used across Hoyoverse’s worlds. Basically, a necessary process to create the world, or perhaps reshape it and change it to be inhospitable for dragons yet hospitable for humans, essentially what the Primordial One did at the very beginning. In other words, the eggsehll was used to separate the sea, a sea of elements and souls and such that granted shapeshifting and abilities to the dragons, like a sort of hivemind that is incompatible with the individualism of humans. For more info on that, check the Men of Lithin book.

The Chemical Marriage is hinted at by Albedo, through the stages of the Magnum Opus in his Ascension - although in the game, the 2 last stages are swapped, with Rubedo coming before Citrinitas (perhaps to reinforce the goal to obtain gold) in the game.

That process also sometimes involves a dove. It’s in consideration to the 3 parts of a person, body (the king), soul (the seelie) and spirit (the dove), and in Christianity, the dove often represents the Holy Spirit. The marriage is sometimes blessed by a descending dove from starry heaven. The dove sometimes is the one that brings the ring. There are other trinities that can be associated with this.

Last but not least, here are all the pairs I could think of from Genshin that execute this, that I will elaborate in detail on a different post. They are made of a Seelie or prophetic being who shared forbidden knowledge with a King, who tried to save humanity by creating a hivemind, bringing tragedy: Traveler from Afar and Seelie (who may still be Istaroth), Decarabian and Amos, Zhongli and Guizhong, Deshret and the Goddess of Flowers, Liloupar and Ormazd, Remus and Sybilla, Ochkan and Ixlel… and potentially in the future either the Traveler with the Abyss Twin, or the Traveler with Paimon.

We can also compare Istaroth and PO to Chronus and Anake, two serpentine beings who created the egg that birthed the world. But according to some mythologies, what came from the egg was Phanes instead.

It’s technically more complicated than that, here is a list of alternate possibilities I found for his origins:

Phanes hatched from the egg of Chronos and Ananke

Phanes hatched from the cosmic/orphic egg placed in Aether (who was the personification of the bright upper sky and another son of Chronos)

Phanes is a first-born deity who emerged from the abyss and gave birth to the universe, and is a god of creation, light and goodness. The Abyss part is extra intriguing because the world has an abyss half, and some in-game books even compare wine with the Abyss, and also with the idea that drinking the abyss/wine is a way to acquire Forbidden Knowledge - check this video for more on that.

Sometimes Nyx is also involved - she is Phanes counterpart. In some tales, she is Phane’s wife, sometimes his daughter, and in others she creates an egg from which Phanes is born, so wtv. I don’t know who Nyx is (besides being likely The Night Mother from the book of the Six Pygmies), but it’s pretty clear that the Abyss half is under her responsibility in some way.

If you refer back to the quote from the book Before Sun and Moon…:

It doesn’t clarify if Phanes and the PO are the same entity or not, the scribe just decides to treat them as the same. I have my own explanation for it, in the next section precisely, but my answer would be “more or less”

It says that Phanes was birthed from an egg, but then proceeds to give a different purpose to the egg, or at least to the eggshell

Here is my interpretation: The PO and Istaroth created an egg/pearl with a chemical marriage, and Phanes was born from an egg. Once he broke the eggshell to be born, the eggshell was used (unclear if by the PO or Phanes) to change Teyvat, to create the world as it is now: a bubble separated from the rest of the universe by a fake sky, less hospitable for dragons, where Abyssal matter and the Primordial Sea stuff are separated from humans, etc. So technically, yeah, Phanes was involved in at least one step for creating the world, and that guaranteed step was the breaking of the eggshell.

This is not in the book, but in the Gnostic Chorus custcene, there is a black serpent tied surrounding the gnostic/genesis pearl. The pearl and an egg are sort of interchangeable, and according to mythology, Phanes is a figure that has the serpent Ananke coiled around him. So that matches up well.

» Theory 2: Phanes is the Primordial One’s soul, just like what Cocouik was to Ochkan

Och-kan, a half-human half-dragon being who hated dragons, sabotaged the plans of his father (the Sage of the Stolen Flame) by following the human Pyro Sovereign Xbalanque - and, after Xbalanque’s death, forbid people from worshiping either the Night Kingdom or even other gods. In his quest to save humans, he became a Tyrant, whose erratic behavior only got worse after excavations that led him to meet Ixlel.

Ixlel was a prophetic figure that used to lead the dragon civilization of the area in the past, who at first was an ally of Och-kan but, upon sharing secret knowledge and prophecies with him, was betrayed. She got revenge by convincing him to use his draconic nature to power his city, by putting his Soul in the Core of Chu'ulel (who later became Cocuik, freed only much later by Bona, after the Cataclysm). Even after Och-kan was overthrown by rebels, he couldn’t die because of that split between body and soul, and his now fully dragon body was used by his father to be an Abyssal conduit, until the interference of the Traveler in the present.

This story has many more details, and once again matches the concept of Chemical Marriage and prophecies that doom Kings, so you can check my post on the topic for proper details.

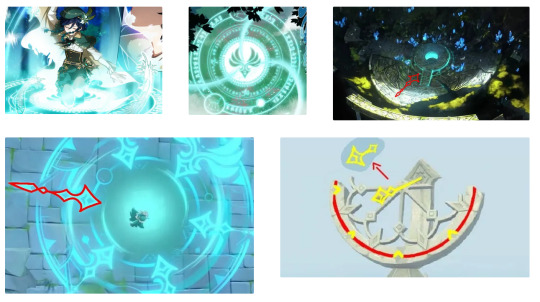

There are several similarities between Venti and Cocouik:

Color scheme and overall shape is the same, that was literally what everyone first thought when seeing it

In wisp form, he had 3 wings, or rather, 3 separate parts that didnt even connect to his body, they just floated behind him, sort of like the wings of the twins at the start of the game, and exactly like the 3 wings of Cocouik. And in human form, his Vision has a single wing with 3 parts.

The power that Cocouik displays against the dragon resembles the power that Venti lends to the traveler to use against Dvalin in the flying sequences. That is the power to supress the corrosive power of the Abyss - it’s what Venti uses, and it’s in the description of Cocouik’s ability too

The description of Cocouik also mentions a halo, within which the Traveler is protected form the Abyss, and halos are often associated with angels

So… if all of those things are comparable with Venti, why would the fact that Cocouik is the soul of a dragon not be?

Oh, right, there was a sus leak that broke my mind months ago and seemed completely nonsensical, but since I started cooking this theory, I can’t help but look back at it. It claimed that Venti was the guide of the Primordial One. Humm… yeah, if Venti was the soul of the PO, I could see that. Maybe he is assuming Istaroth’s role now that she is gone in supporting the PO?

✦•······················•✦•······················•✦

List of EVERYTHING sus and interesting about Venti

Some of the following things will correlate to the theories presented above, while others are just fun fancts that I didn’t know where to place.

✦•······················•✦•······················•✦

Appearance

» Wings:

I already discussed the relevancy of Venti’s angel form and how that ties with being a Seelie, and potentially cursed at first. But the wings are also relevant for another reason: Phanes is described has having wings.

But there is more:

Both in his fake Vision and in wisp form, he only has wings on one side of his body. Just like Cocouik. Possibly hinting at an incomplete nature, or at a duality of natures (dragon and seelie, or the others I already considered)

The wisp wing is formed sort of by 3 wings/parts, and the same is sort of true for the wing in his Vision. The number 3 might just be a coincidence, but it would also fit well with the connections between a chemical marriage and the involvement of the dove, with that third presence representing how a person has 3 parts, body, soul, and spirit. And I already argued why I think Phanes is the PO’s soul.

It’s also possible that this connects with the idea that angels supposedly have 6 wings. So by just having 3 or 3 parts, that is **half of that, aka half angel/**seelie

Funnily enough, in Archon Form he has a wing at each side, and I can’t fully point why that contrast given the previous 2 cases. It’s similar to what happens to Arlecchino in boss form.

Contrary to what the statues portray, the wings in Archon form don’t connect to his back, instead seemingly fusing with his cloak. In Wisp form, and Cocouik’s case, the wings also didn’t connect. That resembles the wings of the twins at the start of the game, the mechanical wings of The Sage of the Stolen Flame, and the wings of the Seelies/envoys always depicted in murals.

In Archon form, the wings have a circular metallic part further hinting at how the wings might be mechanical/not a part of the body. Besides that, the shape has 3 tips, and strongly resembles the wings of the boss Lord of Eroded Primal Fire / Gosoythoth when imitating the form of the Pyro Sovereign. Once again connecting Venti with dragons, although dragons and seelies are really just variations of the same species.

» Other characteristics:

Phanes is also described as androgynous, which, yeah, Venti definitely is. The androginity also matters in the context of a chemical marriage between a union of opposites, since Phanes is supposed to reunite the trates of both “parents”, and the gender-neutral appearance is not the only fusion relevant here. If he turns out to be part dragon part seelie, that is just as relevant.

One thing lacking in Venti, that Phanes has, is a crown. Not even his Archon form has one, at least, not so far. But some people point out that the base of his beret hat has a golden intricate line that could kinda be interpreted as a mini-crown.

Another interesting point about his appearance is the fact that, in wisp form, the top of his head was shaped like an apple, with even a stem and leaf-shape on top. I will talk about the relevance of apples next.

His whole wisp form heavily resembles Cocouik, the soul of a dragon, and I already went over why that matters in one of my theories. The powers Venti lends to the traveler to shoot against Dvalin also resemble the powers of Cocouik used against Ochkan.

And ofc, he has a Cecilia in his hat, and I will go over the relevance of that.

✦•······················•✦•······················•✦

“When I first arrived here, I too was like Dvalin, cursed and left to waste”

During the Mondstadt Archon quest, Venti says that "When I first arrived here, I too was like Dvalin, cursed and left to waste".

Here are some guesses of mine that could explain that:

We know that his Archon form presents him as an angel (source: manga, official arts, and in-game arts and statues) and that angels are seelies (thanks to Natlan’s Archon quest). We also know that the Seelies and Moon kingdom fell, probably symbolizing the end of the Unified Civilization, as a consequence of the marriage between a Seelie and a Traveler from afar, who in turn was likely the Second Who Came, who waged war more a less at the same time as Nibelung and his War of Vengeance. Refer to my (future) other theories for more details. What matters here is that, after that event, the Seelies were cursed to lose their minds and original form, thus why they present as we currently see them in-game. And if angels were seelies, that was probably Venti’s fate too, thus why he showed up as a wisp to the bard.

Since he is comparing himself with Dvalin, maybe his curse was instead related with abyssal corruption. We don’t know what happened to the Primordial One who is currently afk, but if Venti was his soul, and considering that Nibelung used forbidden knowledge and maybe even abyssal energy (unsure of how much those two things overlap), perhaps Nibelung tainted the PO in the confrontation.

Alternatively, maybe he was cursed at existence, which could also explain how he somehow got involved with the bard and the rebellion in Mondstadt and possibly didn't have a strong identity before that? If he was derived from the primordial one, and the PO was the Usurper who took the power away from the original dragons, I don’t think it would be unheard of in stories for the off-spring of authority figures to be cursed by those who hated them.

✦•······················•✦•······················•✦

Knowledge of secret information, and songs of the past, present and future

» About General types of knowledge:

He is the one narrating the Gnostic Chorus cutscene, so he knows about the origins of Teyvat and other important stuff.

He ruled Mondstadt for a long time alongside Istaroth (the Thousand Winds temple was used to worship both of them), so she might have shared relevant knowledge with him from the period of the Unified Civilization, and even from before that.

He knows of others worlds, and titans: "In other, distant worlds…Pangu gave his blood to form the rivers and seas…the gods sacrificed Purusha and cut his body to pieces, and then fashioned all living beings with those parts…the brain of the giant Ymir became clouds. Their sacrifices seeded life in the unliving cosmos. These songs sing of the primeval ones."

In fact, he tells the Traveler about that in the manga prologue, and I don't think none of the things there were discarded - in fact, judging by the element of the traveler (Pyro) in this scene, I and some people speculated for a while that we would return to Mondstadt after Natlan.

» About music - I have a whole post on the importance of music for Teyvat incoming:

He claims to know all songs of the past, present and future, which even denotes knowledge that transcends time, fitting for the son of Istaroth, the Thousand Winds of Time - and also for a Seelie/Angel, which we know he is given his Archon form, who were always prophets.

Istaroth is heavily connected to the moons, who controlled the Fates - past, present, and future - and who were named after song and poetry: Aria, Sonnet, and Canon. The loading screen song, that is the theme of Genshin, is even called Dream Aria. Dream Aria might very well be the Sourcesong that I’m going to elaborate on soon.

Seelies/angels are in turn connected to the moons, and they are at least from the period of the Unified Civilization. They, just like possibly the dragons who originally inhabited Teyvat, know well the value of song. That once again matches with Venti, in part because of his angel archon form, and in part because of how he values song as a way to preserve the truth.

People theorize that Venti is trying to find the Sourcesong, or even knows it already, thus why he knows songs from past, present, and future. According to the Aranara, all songs in the world derive from the Sourcesong, that can diverge into different memories, just like a river diverges into creeks, yet just like creeks eventually flow into the sea, the songs converse.

In other words, that definition might hint at the creation of a hivemind and fusing the souls of the people into a collective conscience, similar to what some God-Kings ended up doing in their attempts at saving humanity and controlling Fate, with Remus being the most relevant since he used the Symphony of Fate to weave the threads, and fates, as if they were strings of an intrument. They only attempted those feats after meeting with Seelies. [Check my future post about Chemical Marriage to see an exhaustive list of all cases of that in genshin]

Venti also canonically states he can read the the rhythmic flow of energy dispersed by the Abyss Order and copy its magic with his lyre - that was how he took down the barriers during the Archon Quest.

His constellation is called Carmen Day, "God of Songs", although in practice that's the title he is less refered as. As 4clover31 on tumblr added: "Carmen also means God's Vineyard, plus, the term Carme or Carmen was used by Romans to reference a poem with a ritual and propitiatory tone."

✦•······················•✦•······················•✦

Venti’s strength

Funnily enough, I don’t find this point relevant for my theory, because even if he turns out to be the weakest Archon currently, there can be many explanations for that, and that is not indicative of his original strength. So it’s possible that he was extremelly powerful and still the soul/son of the PO, while being weak now.

But here is a list of what the fandom usually points out, and the different sides of the argument:

Venti is currently weak:

That’s what he claims, justifying it by saying that the strength of an Archon depends on how much faith the people of the Nation have in their Archon. Since he doesn’t actively rule Mondstadt, and people are free from his influence, he sort of implies that they don’t believe in his enough and that he his willing to let his powers pay the price for his ideals

He hasn’t showcased particularly strong powers even when Mondstadt was in crisis, or when trying to stop Signora from taking away the Gnosis.

We also know he has been gone for a long time, returning to Mondstadt during the Stormterror crisis, so it’s possible that he hasn’t regained his powers.

Maybe he was strong when returning to Mondstadt at present, but he delivered the Anemo Authority to Dvalin by the end of the Archon quest, so even if he lied initially, he is actually weaker now.

Venti is currently strong:

People who defend this argue by using Venti’s own definition of what grants power to an Archon, basically by pointing out how, in some ways, he is more worshipped than many other Archons, even if he doesn’t use that to rule the people. He has a Church, people in Mondstadt clearly pray to Barbatos and mention him often, and they completely adhere and live according to his ideals

As such, there is no reason for him to have lost the powers he once presented, like when he terraformed the land of Mondstadt and also completely changed its weather (after Old Mondstadt got rid of Decarabian, since at the time Mondatadt was covered in snow)

Consequently, Venti simply pretended to be weak out of respect for the autonomy and independence of the humans

Some people who believe this think he was just pretending until the Gnosis was taken, while others think he handed out a fake Gnosis and didn’t even try to resist Signora, and there is even people who think he lost the Gnosis but that hasn’t affected his powers

✦•······················•✦•······················•✦

Cecilias

The only characters in the game connected with Cecilias are: Venti, Istaroth (we see that in Ei’s second story quest), and Albedo (a prototype primordial human, who uses Cecilias as his Ascencion material too)

Cecilias were confirmed in an event, and then at the start of Natlan, to represent “the true feelings of the prodigal son”. But that information actually is as old as his announcement, way back in 2019.

An inactive user in this post found that the name Cecilia possibly came from a Latin word meaning "blind", and according to this source, “Cecilia is as much to say as the lily of heaven, or a way to blind men.” SexyPoro also commented that it’s a variant of the word caecus, that can mean other variations of blind, such as Devoid of light, Vague, Aimless, Invisible, Hidden, Secret, Obscure

Fun fact, Caerus, that sounds a lot like caecus, is an alternatively spelling of Kairos, another of Istaroth’s names. Kairos is a Greek god that resembles Hermes, and who needs wind to fly. Guess that might explain why she ruled Mondstadt alongside Venti for a while, like the Mondstadt saying goes, seeds of stories need to be brought by the wind before they can be cultivated by time.

The Saint Cecilia is a virgin martyr in christianity, and the patron of musicians, composers and poets.

Cecilias are also an important symbol in HI3. They are the symbol of the House Schariac, known for Divine Maidens, warriors who have a chance of taking in the Holy Blood. The Abyss Flower in that game, a ‘Divine Key’ and weapon from the civilization’s Previous Era made specifically to kill herrschers, is also a Cecilia. It’s very possible that Istaroth/Kairos turns out to be an expy of HI3’s Cecilia. She’s known for wielding the Abyss Flower.

The closest real life inspiration would be the flower trillium, which represent the Holy Trinity in Christianity, in turn correlated with the chemical marriage (remember when I mentioned the addition of the dove so that the number 3 represented body, soul and spirit? And how those 3 parts are important for parallels between Cocouik and Ochkan?)

Cecilias look a lot like triquetras, once again connected with the Holy Trinity in Christianism, while in Celtic culture it represents the triple goddesses (3 goddesses that function as a whole, like the Moirai or Norse Norns, who in turn are a bit like the Tribbies of HSR and the 3 moons/fates of genshin). Triquetras are a recurring symbol in Genshin.

Everything here hints at the importance of Venti’s birth and lineage. And while he might just be connected to Istaroth and things stop there, and it would be enough to justify that importance, it’s still possible that it means a little more.

✦•······················•✦•······················•✦

Venti and apples, the fruit of Fate

Here is a list of every connection between Venti and apples that I could find:

In his wisp form, the top of his head is shaped like an apple, including stem and leaf.

He is always asking for apples, even as payment. He also offers them sometimes. He also really enjoys apple cider.

While terraforming Mondstadt, he created the Golden Apple Archipelago

Speaking of golden apples, he literally offers one in one of his birthday arts, and the text that accompanies it is one of the most suspicious things ever: “It is written that there is a whole tiny world hidden inside an apple core. Here, this half is for you. Let's take a stroll in the tiny little world. But remember to keep it a secret because... you're the only one I want to bring there.” Please keep this in mind.

Mondstadt is a land full of apples. There are a few apple trees in Liyue too, and ofc thishas to do with the inspirations behind Mondstadt, so it’s a tenue connection, but still fitting.

Especially in anime, Apples are often depicted as the fruit of Fate (look no further than Mawaru Penguindrum), and in Inazuma, the girl giving Fortune Slips is called Gendou Ringo, with Ringo meaning ‘apple’ in Japanese.

In Sethian Gnosticism, in the Biblical story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, they succumb to the serpent’s temptation and eat the forbidden fruit (often imagined as an apple) from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. That is depicted as a good thing, and as the first step towards freedom from Yaldabaoth (a demiurge, chaos entity and false god, who keeps the souls of people trapped in physical bodies).

I can’t help but wonder if the connection with apples means that he has secret knowledge and awareness of fates and the future, and is waiting for someone else to learn it too, to assume control of Fate or to break free.

If he derived from the PO, that would also made him sort of serpent/dragon-like, or at least part dragon part seelie/angel. He is probably holding fate in his hands - and if an apple contains a tiny world, according to what he said, holding it is not too different from holding the Genesis Pearl - once again tying him with the Gnostic Chorus.

The fact that Venti has only offered one half of the apple in his birthday art may connect with the fact that Phanes only rules half of the world, while the other half, potentially the Abyss, belongs to Nix, the Night Mother. It may alternatively connect to the idea of Chemical Marriage and union of opposites, since that seems to be a fundamental pattern in Teyvat, as I already mentioned.

(Thank you to u/HashtagLowElo on reddit for reminding me of this) In Lyney's teaser, when Lyney is sitting at the bard with the drunkard, Lyney took his drink and transformed it into an apple scented wine. As the man closed his eyes to drink it, Lyney transformed it into an apple before talking about the connection between miracles and magic tricks while also going on to hold the moon. So, the apple was somewhat compared to the moon.

The Golden Apple is specifically relevant in mythology. For example, in Greek Mythology, the Golden Apple of Discord was thrown by Eris at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, leading to the Judgement of Paris and the Trojan War. In the Garden of the Hesperides, golden apples were guarded by a dragon and were part of Hercules' labors. In Irish Mythology, golden apples are depicted on the Silver Branch of the Otherworld.

✦•······················•✦•······················•✦

Sacramental Wine, Dionysus and Phanes

Some myths say that Phanes was Dionysus (god of wine… amongst other things), or Eros (god of love, yes I’m simplifying), and oh boy isn’t Venti the god of all of that too? Although this is complicated since it has to do with gods being iterations of past gods and such.

Okay, this gets less obvious now. Phanes is a first-born deity who emerged from the abyss and gave birth to the universe, and is a god of creation, light and goodness. The Abyss part is extra intriguing because the world has an abyss half, and some in-game books even compare wine with the Abyss, and also with the idea that drinking the abyss/wine is a way to acquire Forbidden Knowledge.

Let’s keep talking about wine. I have to start by recommending this video by Ashikai that I used for a lot of the info that follows.

Sacramental Wine is consumed after sacramental bread, in celebration of the Eucharist. The Catholic Church maintains that by the consecration, the substances of the bread and wine actually become the substances of the body and blood of Christ, and in genshin, a similar process happens when a being consumes the body/blood of gods - sometimes even inheriting powers and an extended lifespan, although corruption as well.

The different types of liquids/elixirs in genshin can even be compared to real life ones: leyline liquid is nectar, primordial seawater is absinthe, and forbidden knowledge is wine. Refer to Ashikai’s video for explanations on the first two, but regarding wine, in the book A Drunkard’s Tale, a character says: “What you humans call wine, we wolves call the abyss”. I already shared how many things connected to Venti relate to the Abyss, from Cecilias to the origins of Phanes.

Fungi (more specifically, yeast) are required to make wine, for the processes of fermentation, and you can see in the list of game examples below how much fungi are relevant in the process of eucharistic rites and how often they are sacramental, as a way to grant powers or memories. Mushrooms in a circle also form the so-called fairy-rings, and besides the importance of rings in the context of genshin as objects that confer power to god-kings, they are also considered a portal. They are also called witch’s rings.

» Mondstadt and wine

Mondstadt is heavily known for its wines, and not just for the production of it. During the distiling process, the portion of alcohol that evaporates is even callled Angel’s Share, the name of Diluc’s tavern. Angels, or seelies, in turn tend to have alcoholic beverages associated with them (really, watch Ashikai’s video for more evidence).

Wine breewing is also heavily connected to witches, who have strong connections with Mondstadt. The witches are also connected to Venti, as revealed in the second Windblume Festival.

Speaking of witches, I already mentioned how witches’ rings or fairy rings are made of mushrooms and considered portals.

Albedo is a famous alchemist created by the witch Rhinedottir. Alcohol is one of the possible solvents used in alchemy, known as alkahest. In Lulian alchemy, quintessence is a solvent distilled from wine, sometimes called aether. Alkahest is the ascension material used for the sword Cinnabar Spindle, and cinnabar in turn refers to the Rubedo stage of the Magnum Opus. That’s typically the final stage, although genshin swaps it, with citrinitas/gold, but usually the Magnum Opus ties with the Chemical Marriage - you know, the thing I said that created Phanes.

Oceanids are often associated with turning water into Wine. The weapon Dialogues of the Desert Sages supports that idea. The oceanid of Springvale, also sometimes called a fairy, blessed/cursed Diona to always make great alcoholic beverages. Oceanids also strongly resemble Hydro Idolons, and Idolons are the kind of ghost most associated with Istaroth, even being one of the names for the Sin Shades from Enkanomiya.

In the Alchemy Ascension event, conveniently said by Venti while standing with Diona, he says “If alchemy has the power to transform matter… I wonder if it could also be used to turn water into wine?”

Kaeya’s Skewers are soaked in Death after Noon, Kaeya’s favorite drink, and if you check the list of examples, you can see that the medicine for Caribert required drawing water in the early AfterNoon, and it was used to water the mushrooms growing on the body of Caribert’s dead mom. The drink is also made with absinthe. The drink, or Kaeya’s skewers, are also mentioned in many sus quests, like Canotila quest about dissolving people and their memories, and in a dialogue with Xamaran.

» Examples of sacramental food/wine in genshin

The desert is full of such examples, from Apep who got to eat King Deshret after his death to gain his knowledge, to the Consecrated Beasts (”consecreated” even means “blessed”.

Jacob in Fontaine also turned into a Iniquitous Baptist abyssal creature after consuming the flesh of a dragon, and it’s possible that other abyss creatures - not hillichurls - went through a similar process, especially considering how all of them have a type named after religious positions (even mages, since the word comes from “Magi” who was a Zoroastrian priest).

Rukkhashava mushrooms, in CN, are called Rukkhadevata Sacramental Mushrooms. Before the description change, it said that the Akademia Sages consumed them to honor the sacrifice of the goddess, and remember her wisdom, like in a Eucharistic ritual. This mushroom is based on the Reishi mushroom (believed to give immortality in Taoism). Wanderer, who tried to ascend to godhood, and Collei who contains remnants of a snake god, need this as an ascension material.

In the first Caribert quest, we see a red/cinnabar version of these mushrooms. They grew in the body of Clothar’s dead wife, and while mushrooms grow on wood, Norse mythology believes that humans were carved from trees. He also had to draw water in the early afternoon (Death After Noon is the name of Kaeya’s favorite drink) to tend to them, and for the medicine. The medicine for Caribert created from those mushrooms had to be blessed by a god, and it followed a similar recipe to the Memory Recipe taught by the Aranara: a Rukkhashava mushroom variation, a lotus (Kalpalata/Barsam), and a purple flower (Sumeru rose/Yajna grass). It’s a sacramental beverage.

Fun fact, the taxonomic name for the Reishi mushroom is ganoderma, and there are mushroom-like aquatic ascension materials called Sea Ganoderma in genshin. Their description says “In the folktales told in a certain land, these mouthless, noseless creatures are the transformed souls of children who died young.” They are used by Yae Miko (guards a Irminsul tree) and Kazuha (ganoderma really like mapple trees)

Xamaran, the giant mushroom in the Chasm, is often taken as the irminsul tree of the area (it even looks like a dragon tree), or instead as a mushroom growing in the body of the main Irminsul (like how mushrooms grow on trees). The name sounds like Shahmaran, a mythological being from Persian mythology who was half human half snake, and the name can be broken into "queen/king of serpents" - and serpents in genshin are somewhat interchangeable with dragons. There are tales both about the queen and the king. What matters is that in the Queen's tale, her flesh leads to recovery, her broth leads to knowledge, and her extract leads to death.

✦•······················•✦•······················•✦

Confused timelines and slumbers

I don’t think there are many instances of this, but there are a few examples that fans point of Venti possibly confusing timelines - either because the wind is free from the confines of time, or because of Venti’s connections with Istaroth and even poential prophetic abilities.

One is during Mondstadt’s AQ, when he tells the Traveler to meet at the “usual place” when we have never met him there before.

Another is a voiceover hidden in a menu, where he greets the Traveler with “Ah, Traveler, we meet again! What? You don't remember me? Ahaha, well, allow me to join you on your quest once again.”

He had to dissapear and go into slumber multiple times, usually after seemingly using a lot of his power: some time after establishing new Mondstadt and making sure that the humans got it (we see him waking up in the manga and realizing how corrupt the aristocracy had become), some time after helping Vennessa win and form the Knights and still taking some time to raise Dvalin, and after the fight against Durin. People theorize it’s only after moments where he spends lots of power, but since we don’t know the exact circunstances that made him go to slumber for the first 2 examples, it’s hard to say.