#michel discourse

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

inside you there are two michel:

michel delpech and michel polnareff

#shitpost specifically designed for 2#psae6#if the michel inside you is michel sardou i don't want to talk to you anymore <3#pau.txt#michel discourse

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

@ michel discourse: out of hands

@effervescentdragon: "who do I vote for?"

@saecookie: "Berger or Polnareff. To put it simply for you. Heartwrench or slut."

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

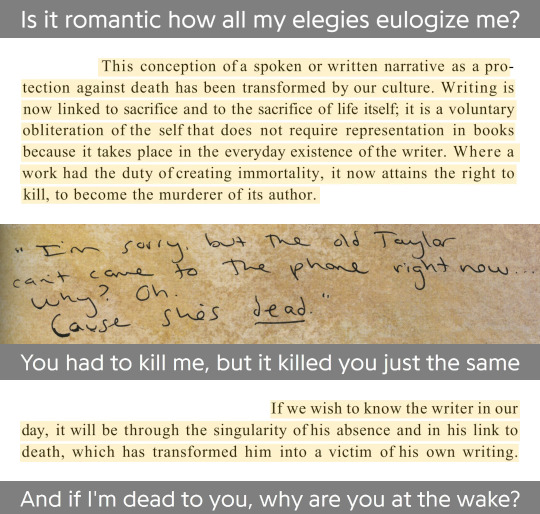

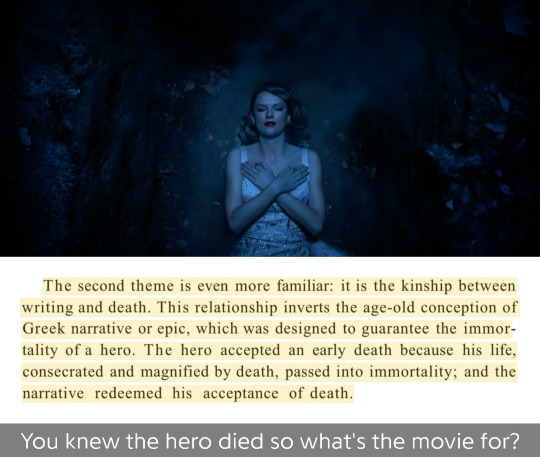

Death of the Tortured Poet

Taylor Swift and other poets in conversation with Roland Barthes's "The Death of the Author" (1967) and Michel Foucault's "What is an Author?" (1969)

I want to say thank you to @ttpds @youmeetyourself and @ohdorothea. This post would not exist were it not for your musings on the topic, our conversations, and your encouragement. Seriously, thank y'all.

Sources:

Unless otherwise noted, lyrics are from Genius and screenshots/scans/etc are from taylorpictures.net

Barthes, Roland. "The Death of the Author"

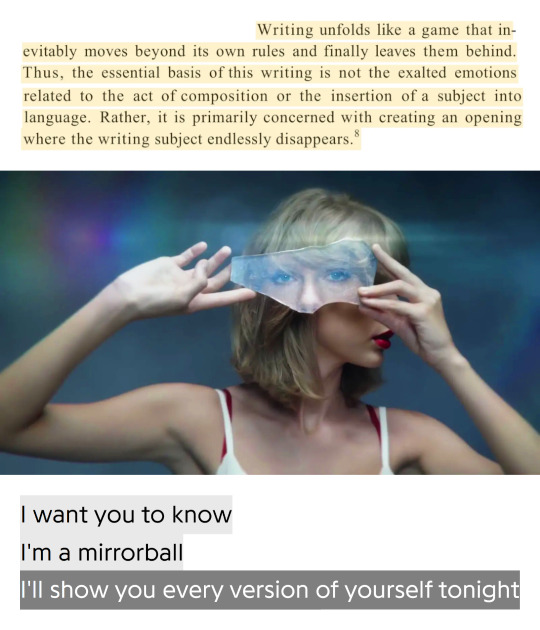

"delicate" music video

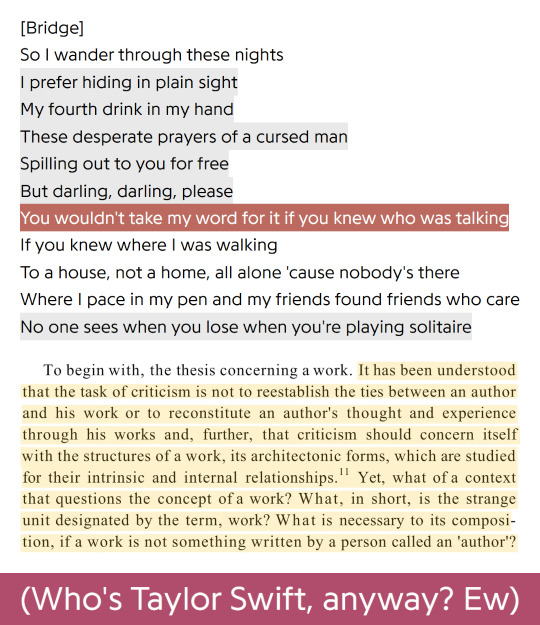

"Dear Reader" lyrics

Foucault, Michel. "What is an Author?"

"Style" music video

"mirrorball" lyrics

Barthes

Taylor Swift before singing "betty" on the Eras Tour in Glendale, AZ on March 17, 2023 (text from @cages-boxes-hunters-foxes)

Siken, Richard. "The Torn-up Road" in The Iowa Review

Promotional image for The Tortured Poets Department from Swift's social media

Savage, Mark "Midnights: What we know about Taylor Swift's songwriting" for BBC.com

Foucault

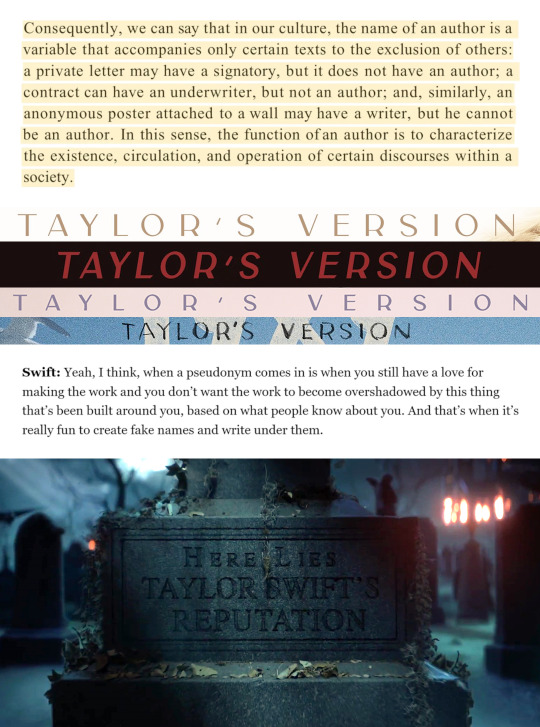

reputation prologue

Barthes

Promotional image for The Tortured Poets Department

Barthes

Halsey. "Gasoline" lyrics

"mirrorball" lyrics

Barthes

Florence & the Machine. "King" lyrics

"Dear Reader" lyrics

Foucault

"22" lyrics

Foucault

"Out of the Woods" music video

"...ready for it?" music video

"Anti-Hero" music video

"look what you made me do" music video

"if you're anything like me" from the reputation magazines

Foucault

Album covers for the Taylor's Versions of Fearless, Red, Speak Now, and 1989

Taylor Swift in Musicians on Musicians: Taylor Swift & Paul McCartney for Rolling Stone

"look what you made me do" music video

"the lakes" lyrics

Foucault

"look what you made me do" handwritten lyrics from the reputation magazines

"my tears ricochet" lyrics

Foucault

"my tears ricochet" lyrics

"look what you made me do" music video

Foucault

"hoax" lyrics

"why she disappeared" from the reputation magazines

Barthes

1989 prologue

Foucault

#alternate title: what if you got so invested in fandom discourse that you read literary theory and got really weird about it#alternate alternate title: oh michel we're really in it now#taylor swift#the tortured poets department#sydposting

805 notes

·

View notes

Note

Good lord, im having such impure holycat thoughts...

I imagine them cuddled together in bed, with Gregor waking up first. Michelle doesn't wear her hair down very often and it's longer and softer than it looks, so Gregor caress her hair, careful not to wake her, and when Michelle wakes up she pretends to still be asleep just so that moment doesn't end.

I have such a sinful mind...

Sinner...../j

#[ ✝️ ] Father Gregor#[ 😸 ] Michelle Erotoph#[ 👨❤️💋👨 ] Ship Discourse#spooky month#spooky month confessions

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

what are yalls thoughts on the “Seeing Red” episode in Buffy: The Vampire Slayer?

I always felt like what Spike did was OOC (out of character) and there is a common opinion (not sure where this originated from), that it was written in only because Joss didn’t like that people preferred Spike over Xander (his self insert).

While I think the topic shouldn’t be dismissed, as it’s important, obviously, but I can see why some don’t consider it canon, as it was written in not based on any plot etc, but on Joss resentment.

#buffy summers#buffy and spike#spuffy#spike btvs#spike#sarah michelle gellar#james marsters#buffy the vampire slayer#btvs#fandom discourse

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

These two things can be true simultaneously:

People are always profoundly influenced by the norms, trends, and incidents in the culture around them, and it's not accurate or fair to reach a judgment that takes zero account of this.

People are not automatons of their cultures with no ability to think critically or exercise moral agency.

Let me give an example!

One of my favorite writers is Michel de Montaigne, who collected many, many opinions in his Essais and was dead before the year 1600. His opinions on women are generally ... not great by our standards, let's say.

He argues that women are irrationally and unpleasantly jealous and petty. He also argues that society is broadly unfair to women, men have wild double standards for them, and women's fundamental nature is not so very different from men's, it's education and society that makes them different.

I would not have a lot of charity for some guy making that argument in 2023. And I'm not going to give Montaigne a pass for every misogynistic argument he makes; those arguments are still wrong, factually and morally. But I'm also not going to go on about personal responsibility!!!! in a way that completely ignores his social context and refuses to give him credit for going so much further, however imperfectly, than most people in his time and circumstances would have.

#people who kneejerk to 'well it was the times' are annoying as hell and sometimes worse#people who kneejerk to pointing out rare exceptions as if it means culture has no effect on people are also deeply annoying#anghraine babbles#anghraine rants#general fanwank#i guess!!#michel de montaigne#discourse hell

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyway i know we’ve discussed the parallels between tommy and buck’s other exes but have we considered the parallels between tommy and ana

#i could write essays on just the eddie/edmundo and buck/evan thing alone#but there’s also the fact that neither was introduced in a positive light at first#the disruption ana initially causes for chris vs whatever the fuck was up with buddie’s friendship in 7x04#anyway idk where this is going#but it’s just making me Think#is all#911 abc#i’ll tag this with#anti bucktommy#just in case#911 discourse#evan buckley#there’s something to be said about tommy being the culmination of both his exes AND eddie’s ex AND somehow eddie himself as well#he’s making things awfully complicated for himself#michelle rambles

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

#michel de montaigne#étienne de la boétie#heart locket meme#i’d write ‘i’d be your voluntary servant’ but boétie wouldn’t like it :/#de l’amitie#discourse on voluntary servitude#gif warning

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do not dislike Michelle Keller, formerly Michelle Lasso, but I do dislike how the series and most fans either refuse to criticize her or defend her.

I understand that fans, esp women, are compelled to defend Michelle because she’s a woman and women are overly criticized and dragged unnecessarily at times. I get that. However, there would be think pieces about Michelle is she were Michael. And I truly hate this current trend of pretending everything is different when it’s a woman involved.

It’s quite strange how people are so sad for Ted being made to feel like he’s too much—hmm, I wonder who made him feel that way—and are rooting for him to have a happy ending with someone who accepts him as he is. Then when you directly criticize Michelle, it’s a ton of excuses about how separation/divorce is hard, Ted wouldn’t be transparent with her, and so forth.

While this is true, intentionally or not, Michelle still hurt Ted in a major way. And, I don’t know about you all, but I believe you should still apologize for hurting someone even if it wasn’t intentional.

Michelle became short tempered with him and had an issue whenever he tried to do things for her. While her reaction wasn’t malicious, there’s nothing wrong with, “hey, I know you meant well. I just—it’s hard being around you and having this life with you when I don’t even feel like I know you. I shouldn’t have lashed out. You didn’t deserve that.”

Boom!

This NEVER happens.

Michelle never has to take any accountability for the things she’s down, which we know has a major effect on Ted. Essentially, people are arguing he deserved that treatment all while saying, “poor Ted.”

Michelle making Ted feel bad for saying “I love you.” I understand Michelle was going through her own shit, but Christ! Would we defending her if the genders were switched? I’ll need to rewatch the episode to really dig into that, but it felt unnecessarily cruel even if she didn’t intend for it to be so.

Someone will correct me on this, but Michelle and ted separate in February and by March of that same year she’s pushing for ted to sign divorce papers. It’s not like he’s a busy man or anything??? Literally most divorces, esp considering how long they’d been married, take a while to happen. Ted fucking granted her the divorce without her even asking and was kind about the entire thing and Michelle is pushing for a divorce within the month.

Is that not strange?

I honestly think this was just a bad writing choice, but my God, I can’t imagine the discourse if Ted was a woman—Thea. And how “Michael” would be dragged for that and people speculating that either they were cheating or wanted to be with new and different women. Not even accounting for how some would relate to “Thea” and how their ex did them dirty.

But again, we can’t talk about that. No matter how fucked up that was, NOPE!

And this recent shit. I don’t even know.

I don’t know if it’s a case of poor writing or not because I don’t think the series is going to go there. Meaning I don’t think the series is going to say Dr. Jacobs groomed Michelle. But let’s keep in mind that he was her therapist originally, and then their marriage counselor. He was the one who fueled Ted’s dislike of therapists and always sided with Michelle. I don’t think Ted even felt like he could be heard.

When Dr. Jacobs realizes it’s Ted, he freezes as if being caught. As if he was cheating with Michelle. Even Michelle is acting suspicious as fuck. There’s no, “I didn’t want him to find out about this, he may take it hard.” It felt like they’d both done something they were supposed to be doing. Both come off as guilty as hell.

Do I think the actually had an affair?

No.

Or maybe it was an emotional affair.

But people love to skip over the shit Michelle does (or inadvertently blame Ted) and it’s fucking annoying. Not necessarily because they don’t pay attention to her, but because the discussion around her behavior when they actually engage with it is either brushing off what she does or defending it.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

mostly offline this weekend

#just in case someone misses my constant constant presence online lol#need to maybe do some discourse distance lol#michelle rambles#getting to asks and tag games soon no worries

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

ok mais quid de michel forever tonight?

je suis ravie de voir que michel forever est autant apprécié, mais vraiment je l'ai oublié sur le post original mais il a eu une mention dans mes tags haha

Michel Forever, mon Jack Bauer 💖Il est hors catégorie.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

In August of 2019, a special issue of the Times Magazine appeared, wearing a portentous cover—a photograph, shot by the visual artist Dannielle Bowman, of a calm sea under gray skies, the line between earth and land cleanly bisecting the frame like the stroke of a minimalist painting. On the lower half of the page was a mighty paragraph, printed in bronze letters. It began:

In August of 1619, a ship appeared on this horizon, near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the British colony of Virginia. It carried more than 20 enslaved Africans, who were sold to the colonists. America was not yet America, but this was the moment it began.

The name of this endeavor was introduced at the very bottom of the page, in print small enough to overlook: “The 1619 Project.” The titular year encapsulated a dramatic claim: that it was the arrival of what would become slavery in the colonies, and not the independence declared in 1776, that marked “the country’s true birth date,” as the issue’s editors wrote.

Seldom these days does a paper edition have such blockbuster draw. New Yorkers not in the habit of seeking out their Sunday Times ventured to bodegas to nab a hard copy. (Today you can find a copy on eBay for around a hundred dollars.) Commentators, such as the Vox correspondent Jamil Smith, lauded the Project—which consisted of eleven essays, nine poems, eight works of short fiction, and dozens of photographs, all documenting the long-fingered reach of American slavery—as an unprecedented journalistic feat. Impassioned critics emerged at both ends of the political spectrum. On the right, a boorish resistance developed that would eventually include everything from the Trump Administration’s error-riddled 1776 Commission report to states’ panicked attempts to purge their school curricula of so-called critical race theory. On the other side, unsentimental leftists, such as the political scientist Adolph Reed, Jr., accused the series of disregarding the struggles of a multiracial working class. But accompanying the salient historical questions was an underlying problem of genre. Journalism is, by its nature, a provisional and fragmentary undertaking—a “first draft of history,” as the saying goes—proceeding in installments that journalists often describe humbly as “pieces.” What are the difficulties that greet a journalistic endeavor when it aspires to function as a more concerted kind of history, and not just any history but a remodelling of our fundamental national narrative?

In the preface to a new book version of the 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones, a Times Magazine reporter and the leading force behind the endeavor, recalls that it began, as many journalistic projects do, in the form of a “simple pitch.” She proposed a large-scale public history, harnessing all of the paper’s institutional might and gloss, that would “bring slavery and the contributions of Black Americans from the margins of the American story to the center, where they belong.” The word “project” was chosen to “emphasize that its work would be ongoing and would not culminate with any single publication,” the editors wrote. Indeed, the undertaking from the beginning was a cross-platform affair for the Times, with special sections of the newspaper, a series on its podcast “The Daily,” and educational materials developed in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. By academic standards, the proposed argument was not all that provocative. The year 1619 itself has long been depicted as a tragic watershed. Langston Hughes wrote of it, in a poem that serves as the new book’s epigraph, as “The great mistake / That Jamestown made / Long ago.” In 2012, the College of William & Mary launched the “Middle Passage Project 1619 Initiative,” which sponsored academic and public events in anticipation of the approaching quadricentennial. “So much of what later becomes definitively ‘American’ is established at Jamestown,” the organizers wrote. But the legacy-media muscle behind the 1619 Project would accomplish what its predecessors in poetry and academia did not, thrusting the date in question into the national lexicon. There was something coyly American about the effort—public knowledge inculcated by way of impeccable branding.

The historical debates that followed are familiar by now. Four months after the special issue was released, the Times Magazine published a letter, jointly signed by five historians, taking issue with certain “errors and distortions” in the Project. The authors objected, especially, to a line in the introductory essay by Hannah-Jones stating that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” Several months later, Politico published a piece by Leslie M. Harris, a historian and professor at Northwestern who’d been asked to help fact-check the 1619 Project. She’d “vigorously disputed” the same line, to no avail. “I was concerned that critics would use the overstated claim to discredit the entire undertaking,” she wrote. “So far, that’s exactly what has happened.”

The pushback from scholars was not just a matter of factuality. History is, in some senses, no less provisional than journalism. Its facts are subject to interpretation and disagreement—and also to change. But one detected in the historians’ complaints a discomfort with the 1619 Project’s fourth-estate bravado, its temperamental challenge to the slow and heavily qualified work of scholarly revelation. This concern was arguably borne out further in the Times’ corrections process. Hannah-Jones amended the line in question; in both the magazine and the book, it now states that “some of the colonists” were motivated by Britain’s growing abolitionist sentiment, a phrasing that neither retreats from the original claim nor shores it up convincingly. In the book, Hannah-Jones also clarifies another passage that had been under dispute, which had claimed that “for the most part” Black Americans fought for freedom “alone.” The original wording remains, but a qualifying clause has been added: “For the most part, Black Americans fought back alone, never getting a majority of white Americans to join and support their freedom struggles.” As Carlos Lozada pointed out in the Washington Post, the addition seems to redefine the meaning of the word “alone” rather than revise or replace it. In my view, the original wording was acceptable as a rhetorical flourish, whereas the amended version sounds fuzzy.

In the book’s preface, Hannah-Jones doesn’t dwell, as she well could have, on the truly deranged ire the Project has triggered on the right over the past few years. (Donald Trump’s ignorant bluster is mercifully confined to a single paragraph.) But neither is she entirely honest about the scope of fair criticism that the work has received. She files both academic disagreement (from “a few scholars”) and fury from the likes of Tom Cotton under the convenient label “backlash,” and suggests that any readers with qualms resent the Project for focussing “too much on the brutality of slavery and our nation’s legacy of anti-Blackness.” (Meanwhile, even the five historians behind the letter wrote that they “applaud all efforts to address the enduring centrality of slavery and racism to our history.”) The editors of the book, who include Hannah-Jones and the Times Magazine’s editor, Jake Silverstein, want to “address the criticisms historians offered in good faith”; accordingly, they’ve updated other passages, including ones on Lincoln and on constitutional property rights. But even the use of the term “good faith” suggests a hawkish mentality regarding the revisions process: you’re either against the Project or you’re with it, all in. There is little room in a venue as public as the 1619 Project’s for the learning opportunities that arise when research sets its ego aside and evolves in plain sight.

As Hannah-Jones notes, the disagreements needn’t undermine the 1619 Project as a whole. (After all, one of the letter’s signatories, James M. McPherson, an emeritus professor at Princeton, admitted in an interview that he’d “skimmed” most of the essays.) But the high-profile disputes over Hannah-Jones’s claims have eclipsed some of the quieter scrutiny that the Project has received, and which in the book goes unmentioned. In an essay published in the peer-reviewed journal American Literary History last winter, Michelle M. Wright, a scholar of Black diaspora at Emory, enumerated other objections, including the series’ near-erasure of Indigenous peoples. Wright sees the 1619 Project as replacing one insufficient creation story with another. “Be wary of asserting origins: they tend to shift as new archival evidence turns up,” she wrote.

The Project’s original hundred pages of magazine material have, in the new volume, swelled to more than five hundred, and certain formatting changes seem designed to serve its “big book” aspirations. Lyrical titles from the magazine issue, such as “Undemocratic Democracy” and “How Slavery Made Its Way West,” have been traded for broadly thematic ones (“Democracy,” “Dispossession”) and now join sixteen other single-word chapter titles, such as “Politics” (by the Times columnist Jamelle Bouie), “Self-Defense” (by the Emory professor Carol Anderson), and “Progress” (by the historian and best-selling anti-racism author Ibram X. Kendi). Along with the preface and an updated version of the original ruckus-raising essay, Hannah-Jones has written a closing piece, cementing her role as the 1619 custodian. In the manner of an academic text, the Project is showier about its scholarship this time around, sometimes cumbersomely so, with in-text citations of monographs with interminable titles. New essays, by scholars including Martha S. Jones and Dorothy Roberts, pointedly bolster the contributions from within the academy. Perhaps also pointedly, endnotes at the back of the book list the source material, which the series in magazine form had been accused of withholding.

At the same time, many of the essays in the book remain shaped according to the conventions of the magazine feature. First, a contemporary scene is set: the day after the 2020 election; the day Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd on a Minneapolis street; Obama’s first campaign for President; Obama’s farewell address. Then there is a section break, followed by a leap way back in time, the sort of move that David Roth, of Defector, has called, not without admiration, “The New Yorker Eurostep,” after a similarly swerving basketball maneuver. For the 1619 Project, though, the “Eurostep” isn’t merely a literary device, used in the service of storytelling; it is also a tool of historical argument, bolstering the Project’s assertion that one long-ago date explicates so much of what has come since. Modern-day policing evolved from white fears of Black freedom. Slave torture pioneered contemporary medical racism. For each of those points a historical narrative is unfolded, dilating here and leapfrogging there until the writer has traversed the promised four hundred years and established a neat causal connection.

For instance, an essay by the lawyer and professor Bryan Stevenson traces the modern plague of mass incarceration back to the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery but made an exception for those convicted of crimes. In his eight pages outlining the “unbroken links” between then and now, Stevenson breezes past the constellation of policies that gave rise to mass incarceration in the span of a single sentence—“Richard Nixon’s war on drugs, mandatory minimum sentences, three-strikes laws, children tried as adults, ‘broken windows’ ”—and explains that those policies have “many of the same features” as the Black Codes that controlled freed Black people a century and a half ago. (The language here has been softened: in his original magazine piece, Stevenson deemed the Black Codes and the latter-day policies “essentially the same.”) It is not an untruthful accounting but it is an unstudious one, devoid of the sort of close reading that enlivens well-told histories. Alighting only so briefly on events of great consequence, many of “The 1619 Project” contributions end up reading like the CliffsNotes to more compelling bodies of work.

At its best, the book’s repetitive structure allows the stand-alone essays to converse fruitfully with one another. Matthew Desmond, explaining the origins of the American economy, describes the lengths the Framers went to secure the country’s chattel, including by adding a provision to the Constitution granting Congress the power to “suppress insurrections.” The implications of that provision and others like it are explored in the essay “Self-Defense,” by Anderson, whose note that “the enslaved were not considered citizens” acquires richer significance if you’ve read Martha S. Jones’s preceding chapter on citizenship. But the formula wears over time. With few exceptions—among them, a piece by Wesley Morris, a masterly stylist—the voices of the individual writers are unrecognizable, hewn to flatness by the primacy of the Project’s thesis. Regretfully, this is true even of the book’s poems and short fiction, which, in a rather utilitarian gesture, are presented between chapters along with a time line that aids the volume’s march toward the present.

For instance, the book’s very first listed event—the arrival of the White Lion in August, 1619—is followed by a poem by Claudia Rankine, which sits on the opposite page and borrows its name from that ship: “The first / vessel to land at Point Comfort / on the James River enters history, / and thus history enters Virginia.” A short piece by Nafissa Thompson-Spires depicts the interior monologue of a campaigner for Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman to run for President, after Chisholm decided to visit George (“segregation forever”) Wallace in the hospital following an assassination attempt in 1972—a visit noted in a time line on the preceding page. As in much of the other fiction in the volume, Thompson-Spires’s prose is left winded by the responsibilities of exposition: “It seemed best not to try to convert the whites but to instead focus on registering voters, especially older ones on our side of town, many of whom, including Gran and PawPaw, couldn’t have passed even a basic literacy test.”

The didacticism does let up on occasion. An ennobling found poem by Tracy K. Smith derives its text from an 1870 speech by the Mississippi Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first Black member of congress, who, a month after his swearing in, had to argue to keep Georgia’s duly elected Black legislators, who’d been denied their seats by the Democrats. (“My term is short, fraught, / and I bear about me daily / the keenest sense of the power / of blacks to shed hallowed light, / to welcome the Good News.”) A poem by Rita Dove channels the antsiness of Addie, Cynthia, Carol, and Carole, the four children who perished in a church bombing in Birmingham on September 15, 1963: “This morning’s already good—summer’s / cooling, Addie chattering like a magpie— / but today we are leading the congregation. / Ain’t that a fine thing!” But, on the whole, the literary creativity fits awkwardly with the task of record-keeping. It is a shame to assemble some of the finest and most daring authors of our time only to hem them in with time stamps.

So what are the facts? There are plenty in the volume that aren’t likely to be disputed. In the late seventeenth century, South Carolina made its whites legally responsible for policing any slave found off of the plantation without permission, with penalties for those who neglected to do so. In 1857, the Supreme Court decided against Dred Scott, ruling that Black people “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides.” In 1919, the U.S. Army strode into Elaine, Arkansas, and gunned down hundreds of Black residents. In 1960, Senator Barry Goldwater mourned the decline of states’ rights heralded by Brown v. Board of Education, contending that protecting racial equality was not federal business. In 1985, six adults and five children in Philadelphia received “the commissioner’s recipe for eviction,” as Gregory Pardlo writes in a poem, including “M16s, Uzi submachine guns, sniper rifles, tear gas . . . and one / state police / helicopter to drop two pounds of mining explosives combined with two / pounds of C-4.” In 2020, Black Americans were reportedly 2.8 times more likely to die after contracting covid-19. What the 1619 Project accounts for is the brutal racial logic governing the “afterlife of slavery,” as Saidiya V. Hartman has put it in her transformative scholarship (which is referenced only once in this book, in an endnote, but without which a project such as 1619 might very well not exist).

The book’s final essay, by Hannah-Jones, argues in favor of reparations so that America may “finally live up to the magnificent ideals upon which we were founded.” By “we” here she is referring to the nation as a whole, but embedded in Hannah-Jones’s vision is a more provincial collective identity. The convoluted apparatuses of anti-Black racism don’t spare individuals based on the specifics of their family trees. Black Americans encompass those whose roots in this country date back for many generations, or for one. Yet Hannah-Jones’s unstated but unsubtle suggestion is that a particular subset of Black people, namely those of us who can trace our ancestry to slavery within the nation’s borders, are the truest inheritors of America, both its ills and its ideals. We represent the country’s best “defenders and perfecters,” are “the most American of all,” and are not “the problem, but the solution.” These dubious honors are pinned, like badges of pride, at the volume’s beginning and end, and, for me, the imposition of patriotism is more bothersome than any debated factual claim. In spite of all of the ugly evidence it has assembled, the 1619 Project ultimately seeks to inspire faith in the American project, just as any conventional social-studies curriculum would.

This faith finds its most sentimental expression in another new book about 1619, “Born on the Water,” which was co-authored by Hannah-Jones and Renée Watson for school-aged readers. Beautifully illustrated by Nikkolas Smith, it centers on a young Black girl’s familiar dilemma during a classroom genealogy assignment—what knowledge does she have to share about an ancestry that was torn asunder by the Middle Passage? One answer comes on the story’s final page, in which the girl is seated at her desk, smiling, her hands poised midway through crayoning stars and stripes for “the flag of the country my ancestors built, / that my grandma and grandpa built, / that I will help build, too.” Here the 1619 Project has left the genres of journalism and history for the realm of fable. But a similar thinking resides at the center of the 1619 Project in all of its evolving forms—past, present, and future, arranged in a single line.

#the 1619 project#nikole hannah-jones#lauren michele jackson#us history#LMJ is such an incredible thinker/writer and this essay always makes me mad about the relative paucity of the rest of the discourse#around the 1619 project#everything getting swept up into our endless culture war debates robs us of real thoughtful scholarship and cultural criticism#also this reminds me that I still need to read her book it's been on my list for years now

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think fankids/ fanchilds are actualy one of the most creative ways to create an oc so im droping some ship ideas because I really want so see how their fankids would look like.

Michelle x Gregor

Carmen x Dexter

Lila x Frank

Kevin x Rick

Evermore x Rick

Evermore x Garcia

Moloch x Lila

Frank x Bob

Carmen x Kevin

Moloch x Bob

.

#[ 😸 ] Michelle Erotoph#[ ✝️ ] Father Gregor#[ 💵 ] Carmen#[ 🐭 ] Dexter The Exterminator#[ 🪻 ] Lila#[ 🚐 ] Frank#[ 🍬 ] Kevin#[ 💤 ] Rick#[ 🪞 ] Mayor Evermore#[ 🤡 ] Clown / Garcia#[ 👹 ] Moloch#[ 🍖 ] Bob Velseb#[ 👨❤️💋👨 ] Ship Discourse#spooky month#spooky month confessions

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

happy pride please wear a fucking mask and don’t send hate to disabled people who don’t show up to celebrations because we are not, and never have been, safe at pride. buy gay art, have gay sex or gay platonic existences, and put every bigot you know on the scientology mailing list.

cishet allies: open your wallets and hand cash directly to every queer person you see for the next 30 days, pay double to those who are black and triple to those who are black and trans, and learn how to support a future and government where queer folks arent your scapegoats.

thats all i got i have to go be a dyke, work on queer theatre, give my queer conference presentation, finish the edits on my lesbian article, and write my lesbian thesis all before the end of the month so i wont be here for any of your discourses this year (thank god)

#i think i got all the discourses out of the way#nobody @ me i am so fucking tired#old dyke yells at cloud#happy pride#lgbtq#michelle does txt

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Batman Freaky Femme Fatales - A Thought

(I made a post about this on my side tumblr and then deleted it without properly copying it so I could post it here.)

But one thing I will probably never see but really like is if there was a Batman movie where the Femme Fatales are sexy but also really FREAKY.

And by FREAKY I mean the freaky awesomeness of Danny De Vito's grotesque yet memorable version of the Penguin. The makeup, the sewers, the actual penguins, the live fish, the Biting of Noses!!

Don't get me wrong, the 80s/90s Batman movies had their faults. But I will never forget Michelle Pfeiffer's Selena Kyle lying dead and twitching as cats lick and bite on her bloody, lifeless fingers.

Let's take this freaky energy and go even FARTHER.

What if Selena Kyle was always the Weird Cat Lady of the apartment complex (they think it's strange for a lady her age but at least the rats are finally gone). What if her fellow tenants don't bat an eye at 50 cats visiting her apartment window the night of her transformation? But what they don't see is Selena in an eye-less trance shoveling raw fish into her mouth a la Tom Hardy in Venom.

What if Catwoman looks like a slinky Leather Dominatrix from afar, or even up close. But her victims don't just get whiplashes and scratches, they also have jugular bites from canine teeth that would put Dracula to shame?

Imagine Batman has his first fight with her and discovers that her teeth are sharp as razors, and they glisten when she grins in the moonlight. He watches her claws grow and retract because, surprise, they are her actual Fingernails!

What if Bruce Wayne struggles to kiss his girlfriend Selena because he secretly witnessed Catwoman catch a live rat with that same mouth? What if Selena secretly hopes that Bruce Wayne sleeps upside-down and eats moths for an evening snack?

What if Poison Ivy was Literally a Cryptid? What if she is the patron saint of Gotham City's most Rejected Creatures. Rats, pigeons, ravens, flies, and cockroaches visit her in swarms when they discover this new source of sustenance. They are starving, she feeds them, she eats them.

What if she is a Venus-human-trap? She looks like a forest nymph, she lures you into a false sense of security. Then the instant you are no longer useful or friendly to her, she becomes something Different. She becomes something Else. You are shrieking and crying and begging for mercy as she feeds your flesh to her Unfathomable Self.

What if Batman and Alfred, when discussing strategies to take on Poison Ivy, have to recall their understanding of Lovecraftian themes? What if Batman has the same kind of harrowing battle as a protagonist in a Junji Ito story? What if Batman has to stop Poison Ivy not only to save Gotham but also because he knows every time she allows her Ego to die it lasts a little longer than before?

Long story short, I really would love someone to make a version of Batman femme Fatales to be just a little more off, maybe just a little more strange than they usually are.

Because I promise, they will still be quite sexy, at least to me.

(Post Script: In this scenario, Batman is NOT a creature. I think it's funny if he is just a Human-Man with Human-Man training and this surprises EVERYONE he fights.)

#poison ivy#catwoman#batman#penguin#danny de vito#michelle pfeiffer#I really am not looking for discourse guys. I'm just a monster fan that wants to monsterify my favorite batman characters#let's have poison Ivy be an eldritch creture. as a treat. if you ship her with harley quinn you know DAMN well she won't give a fck#Let's have Tim Burton and Del Toro direct batman movies just to say f*ck it#Doug Jones can be SCARECROW with his fancy HANDS. And idk bring back danny de vito penguin. fuck it.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

you guys don’t know what discourse is but that’s okay :)

#one post with a dumb take is not discourse#everyone’s reactions to said post however IS discourse#michel foucault is rolling in his grave

3 notes

·

View notes