#masculinist culture

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In its uncertainty, feminism at this moment hedges with a philosophy of individual choice: let there be rights; let there be choices; let there be no right or wrong way for all women. Neo-rationalism is thus condoned (after all it champions the right to individual choices). And neo-romanticism is condemned only for its absolutism, for its hostility to free choice. As neo-romanticist ideology gains ground, fueled by the subjective crisis in women's lives, feminism seems to be come ever more nervously defensive of "choice" for its own sake, less and less prone to pass judgment on the alternatives, or to ask how these came to be the choices in the first place.

The reason we hang back is because there are no answers left but the most radical ones. We cannot assimilate into a masculinist society without doing violence to our own nature, which is, of course, human nature. But neither can we retreat into domestic isolation, clinging to an archaic feminine ideal. Nor can we deny that the dilemma is a social issue, and abandon each other to our own "free choices" when the choices are not of our making and we are not "free."

The Woman Question in the end is not the question of women. It is not we who are the problem and it is not our needs which are the mystery. From our subjective perspective (denied by centuries of masculinist "science" and analysis), the Woman Question becomes the question of how shall we all—women and children and men—organize our lives together. This is a question which has no answer in the marketplace or among the throng of experts who sell their wisdom there. And this is the only question.

There are clues to the answer in the distant past, in a gynocentric era that linked woman's nurturance to a tradition of skill, caring to craft. There are the outlines of a solution in the contours of the industrial era, with its promise of a collective strength and knowledge surpassing all past human efforts to provide for human needs. And there are impulses toward the truth in each one of us. In our very confusion, in our legacy of repressed energy and half-forgotten wisdom, lies the understanding that it is not we who must change but the social order which marginalized women in the first place and with us all "human values."

The romantic/rationalist alternative is no longer acceptable: we refuse to remain on the margins of society, and we refuse to enter that society on its terms. If we reject these alternatives, then the challenge is to frame a moral outlook which proceeds from women's needs and experiences but which cannot be trivialized, sentimentalized, or domesticated. A synthesis which transcends both the rationalist and romanticist poles must necessarily challenge the masculinist social order itself. It must insist that the human values that women were assigned to preserve expand out of the confines of private life and become the organizing principles of society. This is the vision that is implicit in feminism—a society that is organized around human needs: a society in which child raising is not dismissed as each woman's individual problem, but in which the nurturance and well-being of all children is a transcendent public priority . . . a society in which healing is not a commodity distributed according to the dictates of profit but is integral to the network of community life . . . in which wisdom about daily life is not hoarded by "experts" or doled out as a commodity but is drawn from the experience of all people and freely shared among them.

This is the most radical vision but there are no human alternatives. The Market, with its financial abstractions, deformed science, and obsession with dead things—must be pushed back to the margins. And the "womanly" values of community and caring must rise to the center as the only human principles.

-Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women

#barbara ehrenreich#Deirdre English#the future of feminism#masculinist culture#neo rationalism#neo-romanticism

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ep.68 Ovidie & Tancrède Ramonet "Nous sommes plus qu'amis et moins qu'amants. Nous créons ensemble."

Je suis TELLEMENT fière et heureuse d’avoir eu la chance, l’honneur, de rencontrer Ovidie ❤️🔥✊🏽 et son ami et co-auteur, Tancrède Ramonet. J’en rêvais, j’ai tenté et ils ont accepté ! Dans cet épisode, nous parlons bien sûr du livre culte d’Ovidie “La chair est triste” (éd. Julliard, coll. Fauteuse de trouble, dirigée par Vanessa Springora). Mais aussi des documentaires sonores qu’elle a réalisé…

View On WordPress

#achab#amitié#amour#anarchisme#arte#épilation#binge audio#célibat#célibataire#couple#dating#féminisme#france culture#hétéronormativité#livres#masculinistes#misandrie#misogynie#ovidie#patriarcat#podcast#politique#polyamour#rencontres#sif#sociologie#tancrède ramonet

1 note

·

View note

Text

"If gender attributes and acts, the various ways in which a body shows or produces its cultural signification, are performative, then there is no preexisting identity by which an act or attribute might be measured; there would be no true or false, real or distorted acts of gender, and the postulation of a true gender identity would be revealed as a regulatory fiction.

That gender reality is created through sustained social performances means that the very notions of an essential sex and a true or abiding masculinity or femininity are also constituted as part of the strategy that conceals gender’s performative character and the performative possibilities for proliferating gender configurations outside the restricting frames of masculinist domination and compulsory heterosexuality."

- Judith Butler, Gender Trouble

#philosophy#sociology#politics#queer#lgbtq#nonbinary#transgender#trans#ftm#mtf#non binary#enby#genderqueer#genderfluid#feminist#feminism#transfem#transmasc#bi#gay

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since I finished watching The Terror I've been thinking about "The Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell to The Terror Pipeline" (cf. Tumblr user pudentilla). I came to the show because a number of people I followed for JSAMN posts were also posting about The Terror, and naturally I was like, dudes on ships looking very cold and rather gay, what is this. Of course, I liked it immediately, but the reason for the "pipeline" still seemed fuzzy.

I joined this conversation about Tuunbaq's role in the story--how The Terror would still be a great show without the demon bear, but his presence definitely adds a certain whatsit--but things didn't really crystallize for me until I was reading an article that discussed speculative fiction as a form of resistance to the Western, colonialist, capitalist, masculinist model of literature that is often unfortunately dubbed "realist" fiction.

It would be easy to write The Terror as a "realist" narrative about the doomed Franklin expedition. All you do is take out Tuunbaq. It would still be excellent. And yet Tuunbaq--the entity that turns the story into speculative fiction--is the force that overwhelms the entire Western, colonialist, capitalist, masculinist enterprise.

I was fascinated by the end of Mr. Hickey: on the one hand, he appears to reject his native culture in favor of reinventing himself as a wild cannibal shaman of the frozen north. On the other hand, everything about what Hickey wants/tries to do is colonialist, exploitative, and driven by the urge to dominate. He fantasizes that he's connecting with Tuunbaq, but he doesn't understand it at all. And then it eats his face.

That was the fantasy moment that made me think ohhhh, what a beautiful connection. Magic in Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell is always and forever the enemy of colonialist, capitalist, masculinist domination. Lots of other people have blogged about this (recently @fluentisonus, good stuff), and I won't rehash that in detail here. But in JSAMN, magic puts itself into the hands of a Black man, servants, women, people who reject conquest and domination as a way of living. It rescues and sustains those people (like Tuunbaq brings Silna a nice fat seal). But those who would use it to dominate others, it utterly crushes.

tl;dr: 1) The Terror isn't The Terror without Tuunbaq; 2) I rode the JSAMN to The Terror Pipeline and I think I get it now

#long post#speculative fiction#the terror#amc the terror#the terror amc#jonathan strange and mr norrell#jsamn#cornelius hickey#tuunbaq#stephen black#john segundus#lady pole#henry lascelles#the gentleman with the thistledown hair

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

OK OMFD pals. I come to you now with a brief queer history lesson, that absolutely has nothing at all to do with Izzy Hands, I mean...

So in the 1960s, Susan Sontag wrote an essay on Camp as an aesthetic sensibility. Beforehand, camp had been this mode of expression that, while not purely invented by or strictly unique to queer folks, had become (much like polari) something of a secret language between queers. In many ways, camp was performed as a survival mechanism, a way of reclaiming insults and derision. If the general population was going to call gay men fairies and pouffes, then turn lemons into lemonade. Live that fabulously and make fun of the weaponizers in the process.

This is an extremely brief and oversimplified explanation of early camp, but what's important is that after Sontag, this was fashionable and exciting, and the straights all knew about it now.

As this discourse developed, in the 70s and 80s (with some bleed in either direction) we saw huge boom of masculinist queers, exemplified by the leather community. A lot of these masculinists were also, in some ways, assimilationists. A lot of these masculinists (though of course not all) started to reject camp and chafe at camp being seen as synonymous with queer expression because they were Manly Men and wanted to be taken seriously, not seen as effeminate weaklings. They felt that camp was setting them back.

Which is of course hugely ironic given that Leather Culture are EXTREMELY camp, as it is masculinity to such a performative extreme that calls into question so many normative ideas but I GUESS SURE, whatever. (Not all leather queers were anti camp to be clear but there's overlap)

So the assimilationist masculinists thought that being associated with camp hurt their cause at being taken seriously. And actively tried to make camp a thing of the past not to be taken seriously. But here's the thing about camp...Camp is all about flourishing in the margins and undercutting the overly serious. Camp takes not being taken seriously very seriously. The assimilationists would not have a platform to stand on if camp hadn't helped keep the heart beating. Camp kept us alive. Camp kept us loving ourselves when the world wanted otherwise.

Camp is funny, glamorous, overtly silly, playful, ironic with a razor sharp edge, and camp loves so deeply.

And so anyway, Izzy Hands the serious masculinist finding the open arms of camp waiting for him in his time of need?? I'll just be over here crying about how well David Jenkins knows his history.

#our flag means death#our flag means death spoilers#ofmd#ofmd spoilers#izzy hands#israel hands#I LOVE THIS BROKEN LEATHER MAN SO MUCH#Fang and Wee John please take turns spooning him at night while he chokes down his sobs#queer history#camp

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

look I know it’s a like a whole image that’s been lionized by masculinist cultural work for decades now but it’s also kinda true: sometimes you wake up and you have cigarettes (because you’re addicted to nicotine) and coffee (because they make the morning cigarettes taste better it’s a whole thing…also the addiction to caffeine) and you realize ‘huh I don’t think I need to eat this morning I have work anyway’ it’s all extremely healthy and reasonable but most importantly common

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I have chosen to do instead of starting my history/film studies essay

Billy Hargrove is a deeply complicated character who was born of two white mens’ want to get out of the very real and valid accusations of racism following the way they wrote Lucas’s character in series 1. However, because this is fandom and The Duffers, there is a tendency to simplify him. And that is fucking boring. This is why (in a very brief form) Billy Hargrove acts the way he does from the perspective of history, politics and sociology.

(Discussing topics less touched on because analysis of Billy in relation to queerness or abuse have been done FAR better than I would explain them)

Even just his name tells us a lot about him as a character. The surname Hargrove originates in Cheshire, in the north west of England. Based on historical context, the Hargrove’s likely moved from Cheshire to Liverpool sometime after 1770, looking for work in Liverpool’s ports, possibly making the move to America sometime post 1850. His mothers side are very clearly Catholic, possibly Irish-Americans. And the first name Billy is a traditional blue collar, working class name. Probably coincidental but a name popular in Liverpool.

Neil and the absolute piece of steaming shit that he is fits in chronologically with the rise of Californian conservatism in the 1960s and 1970s, and the “plain folk” stance that politicians like Nixon took in order to appeal to the white working to upper working class. This type of plain folk outlook blamed both the upper class from the north but also relied on the racist and classist politics of blaming African Americans and those in poverty for all societal ills.

Significantly, Billy in canon was living through a time of globalisation where exposure to the international was becoming more accessible than it had ever been. Just though watching the news it would have been easy to become disillusioned. The Troubles, Brazil’s military dictatorship, The Miners Strike, Israel’s colonisation of Palestine, Cold War propaganda, the AIDS pandemic. It would be very easy to drop into a counter culture subculture.

Do we have any proof that he cared about these issues? Not really. Do we have any proof that he DIDN’T care about these issues though- I’m going to say no to that as well.

Billy represents a more demonised figure than both Eddie and Jonathan for one simple reason though. He is the most stereotypical portrayal of a working class man. Jonathan and Eddie both have tangible connections to interests read as more middle class but Billy’s hyper masculinist presentation and relationship with his car makes him the perfect Proletariat villain.

In relation to why it is so popular to hate Billy in comparison to literally every other character in stranger things, even Neil and Karen, who were objectively terrible people, there could be a lot of different reasons.

One thing is undoubtedly true though.

You can’t ignore Billy Hargrove

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's hard to escape the conclusion that Ovid's stories of mothers who engage in son-slaughter are graphic fulfilments of the patriarchal fantasy which asserts women's causal contribution to man's death as well as his birth. Their inner psychic turmoil, leading to a renunciation of a maternal 'love' in the service of paternal power, is yoked symbolically by Ovid to the unconcealing of all that was supposed to remain inside, repressed, hidden from view (...) it is as if the body's inner uterine spaces, the viscern, are turned outwards to engulf and reconsume the men who emerged from them. The monstrous wombs of Ovid's murderous mothers seem to epitomize (by representing in reverse) the abjection of the maternal body as irredeemably, terrifyingly "other". The abject, for Kristeva, is an inassimilable or excessive component of the superego that is radically excluded and draws me to a place where meaning collapses', where insides and outsides are terrifyingly conflated. The original object of abjection is the maternal body, on whom we existed in a necessary, but potentially overwhelming dependence (...) In Kristeva's account, the abjection of the maternal body is a process that is necessary for the formation of human subjectivity in Western culture.

And yet I want, perhaps improbably, to resist such a determined conclusion, even though Ovid's text clearly flirts with and is seduced by the fantasy of demonic, dismembering mothers, and the supposed necessity of their abjection. Alongside their viscerality and bodily interiors, I've drawn attention to these women's internal dilemmas, articulated through rhetorical debates with themselves, debates which are contrary to the model of maddened maternal speech usually perceived by critics in Roman epic-rational, eloquent, thetorically coherent in their own way. They may be frenzied, but these women do not at least at this point 'wail'. Their debates are particularly Ovidian reflections on agency and the limits of language: "I want to act and I cannot," as Althaea says, "now pietas and the name of mother break my resolve". The primary metamorphosis in the cases of Procne and Althaea is thus not of shape but of psyche: they experience a radical switch from joy to grief to rage, but express this painful metamorphic process in terms of a certain loss of self and the struggling emergence of another. Split between words and action, conjugal and natal identities, Procne and Althaea engage in projects of self-fashioning, exploring a notion of the self in progress or flux. Which should come first, sisterly or motherly love? Passion or reason? Living kin or the dead? Like Medea, Ovid's mothers who kill their kin are radically unsettling because they do not so much reject their motherhood outright as choose, according to social and rhetorical context, to generate another identity out of what they perceive as their degraded maternal bond. The causal relationship of maternity and death is presented here not as inevitable and 'natural', but as the anguished offspring of masculinist violence, patriarchy's guilt coming back to haunt it.

'Matermorphoses: Motherhood and the Ovidian Epic Subject' from Reproducing Rome: Motherhood in Virgil, Ovid, Seneca, and Statius by Mairéad McAuley

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

one thing the barbie discourse really highlighted for me was how men equate having humanity as being dominant, hence, whenever women are dominant and men subordinate, men insist that men are being persecuted, hurt, or oppressed.

that's why they think that matriarchy would be violent. that's why they're so offended and vitriolic when women dare to assert themselves in any way (or denounce femininity and subjugation). to be a human man is to be dominant. there can be no other definition. so if a man isn't dominant then he is suffering and his humanity is under attack.

women cannot suffer in subordination because that's what being a woman is. so if women are beaten, raped, humiliated, barred from education, women cannot feel injustice because to be woman is to be inhuman. like animals, we do not recognize or feel things like suffering. we do not crave things like dignity. so men haven't done anything wrong by subjugating us. not really. they can't do anything wrong because we don't have a developed sense of morality, so their morality cannot be applied or meaningful to us.

but what men fear isn't women dominating them, they fear men dominating them. because they know what dominance does to a man. it may complete him, but it also makes him dangerous to his competitors. that, and their entire world is male-centric. so when they view women in power, they view them not as women, but as women becoming men.

that's why barbies ignoring kens is egregious and the idea of matriarchy frightening. they cannot imagine it outside patriarchal and masculinist culture. they cannot believe that a woman would not want to rape or kill or pillage once in power. human, after all, means male, so if a woman became human, it would have to mean she thought, acted, dressed and behaved as men did.

they are too afraid to admit to what that would mean about themselves. if the woman, the animal, can feel and have a moral sense, if they can understand and experience suffering, then the humanity of the man is in question because as someone with a supposed moral sense and enlightenment, he has been the one oppressing them, cruelly cutting them down without thought (that is mind). he is the inhuman one. now the man must question god, he must question his integrity and sense of innocence and identity, he must begin to wonder if he or any man is truly even redeemable.

and then they'd have to face guilt. and with that guilt torment. and with that torment, they would see that the only way to begin to live with themselves is rebel against the system, side with women, and that would mean marking himself as woman, as animal, to other men.

as viable for the slaughter

for if he is rejecting dominance, he is rejecting male humanity, divinity and authority, he is forfeiting his right to be treated as human by other men.

and not many men in history have ever been willing or brave enough to do that. so instead, they insist that animals are bloody and violent and mindless (despite the fact that there are no animal-created human farms) and that women would be just as bad, just as wicked, once they had power, once they became human.

in other words, once they became men.

#radblr#barbie#masculinity#femininity#humanity#veganism#feminism#feminist discourse#mine#dominance and submission are male hierarchial terms#it is male philosophy to insist that only the hunter only the destroyer is god and human and divine#they assume that this is human philosophy that we all share because they view humanity on male terms#but it is just men#it is simply male culture#it is not universal#it is not humanity#radfem#radical feminism#grasp it from the root gyns

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Most mar a garbage day is megirta (egybol ossze is omlott a site)

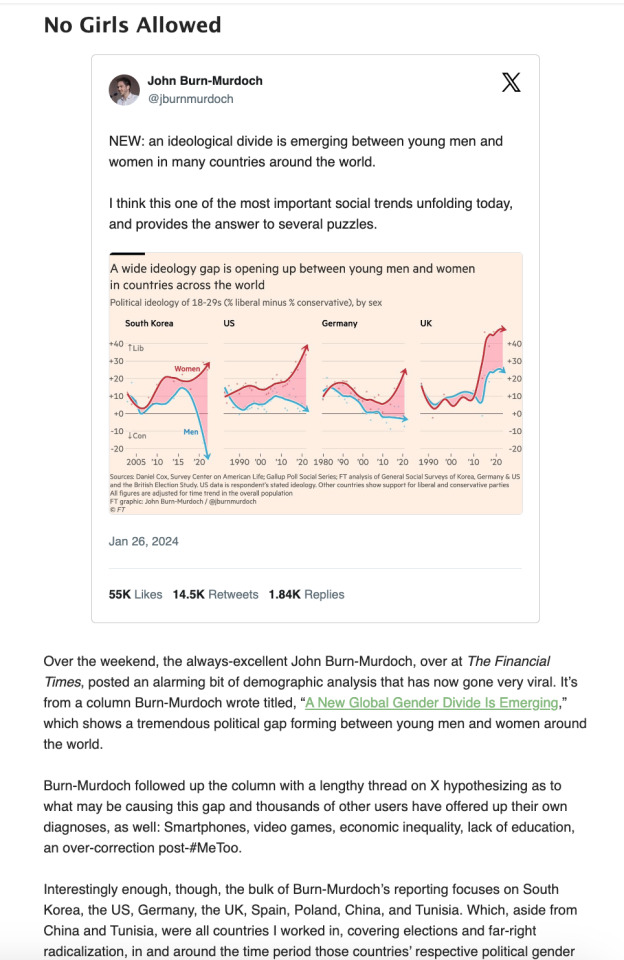

Over the weekend, the always-excellent John Burn-Murdoch, over at The Financial Times, posted an alarming bit of demographic analysis that has now gone very viral. It’s from a column Burn-Murdoch wrote titled, “A New Global Gender Divide Is Emerging,” which shows a tremendous political gap forming between young men and women around the world.

Burn-Murdoch followed up the column with a lengthy thread on X hypothesizing as to what may be causing this gap and thousands of other users have offered up their own diagnoses, as well: Smartphones, video games, economic inequality, lack of education, an over-correction post-#MeToo.

Interestingly enough, though, the bulk of Burn-Murdoch’s reporting focuses on South Korea, the US, Germany, the UK, Spain, Poland, China, and Tunisia. Which, aside from China and Tunisia, were all countries I worked in, covering elections and far-right radicalization, in and around the time period those countries’ respective political gender gaps began widening. I’m not saying I have a tremendously in-depth understanding of, say, Polish toxic masculinity, but I did spend several days there following around white nationalist rappers and Catholic fundamentalist football fans. And, in South Korea, I worked on a project about radical feminists and their activism against the country’s equivalent of 4chan, Ilbe Storehouse.

In fact, between 2015-2019, I visited over 20 countries, essentially asking the same question: Where do bad men here hangout online? Which has given me a near-encyclopedic directory in my head, unfortunately, of international 4chan knock-offs. In Spain, it’s a car forum that doxxes rape victims called ForoCoches. In France, it’s a gaming forum that organized rallies for Marine Le Pen called Jeux Video. In Japan, it’s 2channel. In Brazil, it’s Dogolachan. And most, if not all, of these spaces pre-date any sort of modern social movement like #MeToo — or even the invention of the smartphone.

But the mainstream acceptance of the culture from these sites is new. Though I don’t actually think the mystery of “why now?” is that much of a mystery. While working in Europe, I came to understand that these sites and their culture war campaigns like Gamergate were a sort of emerging form of digital hooliganism. Nothing they were doing was new, but their understanding how to network online was novel. And in places like the UK, it actually became more and more common in the late-2010s to see Pepe the Frog cosplayers marching alongside far-right football clubs. In the US, we don’t have the same sports culture, but the end result has been the same. The nerds and the jocks eventually aligned in the streets. The anime nazis were simply early adopters and the tough guys with guns and zip ties just needed time to adapt to new technology. And, unlike the pre-internet age, unmoderated large social platforms give them an infinitely-scalable recruitment radius. They don’t have to hide in backrooms anymore.

Much of the digital playbook fueling this recruitment for our new(ish) international masculinist movement was created by ISIS, the true early adopters for this sort of thing. Though it took about a decade for the West to really embrace it. But nowadays, it is not uncommon to see trad accounts sharing memes about “motherhood,” that are pretty much identical to the Disney Princess photoshops ISIS brides would post on Tumblr to advertise their new life in Syria. And, even more darkly, just this week, a Trump supporter in Pennsylvania beheaded his father and uploaded it to YouTube, in a video where he ranted about the woke left and President Biden. Online extremism is a flat circle.

The biggest similarity, though, is in what I can cultural encoding. For ISIS, this was about constantly labeling everything that threatened their influence as a symptom of the decadent, secular West.

(X.com/jeremykauffman)

Taylor Swift, an extremely affluent blonde, blue-eyed white woman who writes country-inflected pop music and is dating a football player headed for the Super Bowl. She should be a resounding victory for these guys. Doesn’t get more American than that. But due to an actually very funny glitch in how they see the world, she’s actually a huge threat.

Pop culture, according to the right wing, should be frivolous. Because before the internet, it was something sold to girls by corporations run by powerful men. Famous pop stars through the ages, like Frank Sinatra, America’s first Justin Bieber, or The Beatles, the One Direction of their time, would be canonized as Great by Serious Men after history had forgotten they rocketed to success as their generation’s Tumblr Sexymen. But from the 2000s onward, thanks to an increasingly powerful digital public square, young women and people of color were able to have more influence in mainstream culture and also accumulate more financial power from it. And after Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign was able to connect this new form of pop influence to both liberal progressive politics and, also, social media, well, conservatives realized they had to catch up and fast. And the fastest way to do that is to try and smash the whole thing by dismissing it as feminine.

Pop music? It’s for girls. Social media? It’s for girls. Democrats? Girls. Taylor Swift? Girls and also a government psyop. But this line of thinking has no limit. It poisons everything. If Swift manages to make it to the Super Bowl, well, that has to become feminine too. And at a certain point, the whole thing falls apart because, honestly, you just sound like an insane loser.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Generally post-modernism sits most comfortably in the realm of philosophy, within which there exists a long standing debate about whether philosophy has a practice. This theory emerges from the practice of intellectualising or thinking, without the necessity to include experience or intuition. Although postmodernism is said to challenge a whole epoch or paradigm for making sense of the world (known as the Enlightenment Project of Modernity), it nonetheless replaces this paradigm with one, no less masculinist than its predecessor. Whether it be through quantum physics, eastern philosophies or post-modern deconstruction, the voice of masculine discourse continues to occupy this new territory. It is primarily the voices of men that create the metaphors for meaning that are given space in post-modern discourse. Even in this epoch of change, the dominant words and ideas that create the meanings by which we make sense of the world, come from a masculine discourse. In both the modern and post-modern era it is primarily men who make the metaphors for meaning. For example James Jean replaced the image of the world as a machine in saying, "the universe begins to look more like a great thought than a great machine" (cited in Capra: 1982, p. 76).

Friedrich Nietzsche said:

. . .there are many kinds of "truths," and consequently there is no truth . . . "Truth" is therefore not something there, that might be found or discovered, but something that must be created (1990, р. 55).

The Buddha thousands of years previously said:

We are what we think. All that we are, arises from our thoughts. With our thoughts we make our world.

Notwithstanding the potential for liberation to be found in such ideas, history has shown us that good ideas alone do not make a significant difference to the oppressed, the dispossessed or suffering. To work for change in the lives of women who have experienced violence and to decrease the use of violence against women in the future, I embrace the words and meanings arising from women's experiences. I will continue to create and work with radical feminist theory that names the violence committed against us, and seeks to change the structures that perpetuate it. As Elizabeth Ward states in Father-Daughter Rape:

In the development of the feminist movement, women have seized the power of naming. This is a revolutionary power because in naming (describing) what is done to us (and inevitably to children and men as well), we are also naming what must change. The act of naming creates a new world view. The power of naming resides in the fact that we name what we see from the basis of our own experience: within and outside patriarchal culture, simultaneously (1984, p. 212).

I believe a good measure to apply to theories, and specifically postmodern theory, is to ask the following questions: Whose interests do they serve; do they have a liberatory purpose and who will benefit from them; how useful are they and to whom, and what direct actions and strategies emerge from these theories? Then we will see the real threat that the radical feminist pursuit of truth, grounded in the gritty reality of women's lives constitutes, and then we can begin to name the backlash, on the streets and in the academy.

-Katja Mikhailovich, ‘Post-modernism and its "Contribution" to Ending Violence Against Women’ in Radically Speaking: Feminism Reclaimed

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Ribu's anti-imperialist feminist discourse would later manifest in its solidarity protests against kisaeng tourism. This sex tourism involved Japanese businessmen traveling to South Korea to partake in the sexual services of young South Korean women who worked at clubs called kisaengs. Ribu's protests against kisaeng tourism represented how the liberation of sex combined with ribu's anti-imperialism and enabled new kinds of transnational feminist solidarity based on a concept of women's sexual exploitation and sexual oppression. From ribu's perspective, this form of tourism represented the reformation of Japanese economic imperialism in Asia. They were not against sex work by Japanese women, but opposed to the continued sexual exploitation of Korean women as a resurgence of the gendered violence of imperialism: Ribu activists hence connected imperialism and sexual oppression of colonized women to the continuing sexual exploitation of Korean women in the 1970s. In this way, they were able to expand the leftist critique of imperialism and, at the same time, point to the fault lines and inadequacies of the left.

In her critique of the left, Tanaka points to its failure to have a theory of the sexes.

Even in movements that are aiming towards human liberation, by not having a theory of struggle that includes the relation between the sexes. the struggle becomes thoroughly masculinist and male-centered (dansei-chushin shugi].

According to ribu activists, this male-centered condition infected not only the theory of the revolution and delimited its horizon, but it created a gendered concept of revolution that privileged masculinist hierarchies within the culture of the left. Ribu activists decried the hypocrisy of the left and what it deemed to be the all-too-frequent egotistical posturing of the "radical men" who "eloquently talked about solidarity, the inter national proletariat and unified will," but did not really consider women part of human liberation. Ribu activists rebelled against Marxist dogma and rejected these gendered hierarchies that valued knowledge of the proper revolutionary theory over lived experience and relationships. Moreover, ribu activists criticized what they experienced as masculinist forms of militancy that privileged participation in street battles with the riot police as the ultimate sign of an authentic revolutionary. While being trained to use weapons, activists like Mori Setsuko questioned whether engaging in such bodily violence was the way to make revolution. Ribu's rejection and criticism of a hierarchy that privileged violent confrontation forewarned of the impending self-destruction within the New Left.

...

News of URA [United Red Army] lynchings, released in 1972, devastated the reputation of the New Left in Japan, and many across the left condemned these actions. This case of internalized violence within the left marked its demise. Although ribu activists were likewise horrified by such violence expressed against comrades, many ribu activists responded in a profoundly radical manner that I have theorized elsewhere as "critical solidarity." Ribu activists had already refused to lionize the tactics of violence; hence, they in no way supported the violent internal actions of the URA. However, rather than simply condemning the URA leaders and comrades as monsters and nonhumans [hi-ningen), they sought to comprehend the root of the problem. They recognized that every person possesses a capacity for violence, but that society prohibits women from expressing their violent potential. In response to the state's gendered criminalization of Nagata as an insurgent and violent woman, ribu activists practiced what I describe as feminist critical solidarity specifically for the women of the URA. Ribu activists went in support to the court hearings and wrote about their experience and critical observations of how URA members were being treated. By visiting the URA women at the detention centers, consequently, ribu activists came under police surveillance. Ribu activists enacted solidarity in ways that were tot politically pragmatic but instead philosophically motivated. Their response involved a capacity for radical self-recognition in the loathsome actions of the other. Activists wrote extensively about Nagata - for example, Tanaka described Nagata in her book Inochi no onna-tachi e [To Women with Spirit] as a kind of "ordinary" woman whom she could have admired, except for the tragedy of the lynching incidents. In 1973, Tanaka wrote a pamphlet titled "Your Short Cut Suits You, Nagata!" in response to the state's gendered criminalization of the URA's female leader, the deliberate publication of such humanizing discourse evinces ribu's efforts to express solidarity with the women who were arguably the most vilified females of their time. Hence, ribu engaged in actions that supported these criminalized others even when the URA'S misguided pursuit of revolution resulted in the unnecessary deaths of their own comrades. Through ribu's critical solidarity with the URA, they modeled the imperative of imperfect radical alliances, opening up a philosophically motivated relationality with abject subjects and a new horizon of counter-hegemonic alliances against the dominant logic of heteropatriarchal capitalist imperialism.

While the harsh criticism of the left was warranted and urgently needed given the deep sedimentation of pervasive forms of sexist practice, it should be noted that, at the outset of the movement, there were various ways in which ribu's intimate relationship with other leftist formations characterized its emergence. At ribu's first public protest, which was part of the October 21 anti-war day, some women carried bamboo poles and wooden staves as they marched in the street, jostling with the police." Ribu did not advocate pacifism; its newspapers regularly printed articles on topics such as "How to Punch a Man." During ribu protests from 1970-2, some ribu activists-as noted, with Yonezu and Mori - still wore helmets that were markers of one's political sect and a common student movement practice."

- Setsu Shigematsu, “'68 and the Japanese Women’s Liberation Movement,” in Gavin Walker, ed., The Red Years: Theory, Politics and Aesthetics in the Japanese ‘68. London and New York: Verso, 2020. p. 89-90, 91-92

#setsu shigematsu#ribu#revolutionary feminism#feminist history#patriarchal violence#heteropatriarchy#social justice#history of social justice#militant action#far left#new left#1968#japanese 68#japanese history#left history#academic quote#reading 2023#critical solidarity#united red army#anti-imperialism#sex tourism

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Freud’s understanding of sexuality is completely masculinist and also reifies the culture of bourgeois fin-de-siecle Vienna as the transhistorical model of psychological formation. Yet what Marx and Freud do tell us is that seeming contradictions might not be examples of intellectual bad faith but keys to the not-so-secret, yet disavowed, relationships that have come to structure ways in which we perceive and act upon symbols and things. By looking at sexual and other forms of desire, and their self-deceptions, historians might uncover such acts of simultaneous forgetting and remembering, self-deception and aggressive desire— acts or the historical detritus of acts that displace deeply contradictory issues onto objects or even other persons. Indeed, historically constructed questions of group and individual identity are often charged with fierce, even erotic passions, and surrounded in processes of forgetting and remembering that defy constraint in simplistic paradigms. Having once forgotten his or her creation of the “impassioned object,” the fetishist returns compulsively, often renewing relationships of exploitation in the process. For by doing so, he or she pleasures the self with the unacknowledged remembrance of a transgression Without blame, an ambiguity controlled and fixed, a memory displaced onto and encoded in the fetish object. So even in our own day, we see the fetishization of flags, of skin color, battlefields, historic mansions, presidents’ reputations, or black athletes.

Edward E. Baptist, '"Cuffy," "Fancy Maids," and "One-Eyed Men": Rape, Commodification, and the Domestic Slave Trade in the United States'.

#ska reads a thing#this piece is good but also devastating -- hearing these men describe their own crimes in their own words is deeply ugly

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Any Halloween read recommendations off the top of your head?

Nothing I've never mentioned before, but I'll repeat some recommendations.

There are always the foundational horror classics from the 19th century if you've never read them: Frankenstein, which is all-around the best of them, a metaphysical tragedy of almost Shakespearean and Miltonic proportions; Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Hyde, which is the most aesthetically perfect and beautiful, as praised by Nabokov; and Dracula, which is most rollicking and fun for "cultural studies" purposes, the basis of innumerable theses on Late Victorian psychology, sexuality, and politics.

Somebody recently asked me about Shirley Jackson, so let me recommend as a 20th-century classic The Haunting of Hill House—perhaps paired with The Turn of the Screw for a double feature of psychosexually ambiguous revenants.

I recently mentioned that Sara Gran's 2003 possession novel Come Closer had become trendy, I assume because it blends the demonic genre (in this case a Jewish—rather than the more common Catholic—demon) with an anticipation of the sad/gross-girl and/or feminine rage content of the post-Moshfegh literary novel; I myself read it in one sitting after randomly picking the 2011 reissue up off the new shelf at the library. If you're looking for something more "pop" while intelligently done, Come Closer more than fits the bill. Another demonic possession novel, also rooted in Jewish culture, but a bit more modernist and remote, and shall we say masculinist rather than feminist, is I. B. Singer's remarkable Satan in Goray, which I read a couple of years ago and loved.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reframing the American Dream: Justine Kurland’s Photographic Journey

Justine Kurland's career as a photographer has been shaped by her fascination with the American landscape and the communities that live on its fringes. Her work has consistently challenged traditional narratives and offered alternative perspectives on the country's cultural identity. Two key aspects of her work are her reinterpretation of the American landscape and her exploration of the intersection between freedom and everyday reality.

Kurland's reinterpretation of the American landscape is a central aspect of her work. Her early photographs, taken during road trips across the country, contradicted the masculinist mythology of the American West and instead offered a radical female imaginary. This approach not only challenged the dominant male gaze, but also created a new narrative that was more inclusive and representative of women's experiences. In this way, Kurland's work has helped reframe the way we think about the American landscape and the people who inhabit it.

In her more recent work, Kurland has continued to explore the intersection between freedom and everyday reality. One series examines the relationship between the freedom of the open road and the mundane reality of car culture. By highlighting the tension between the romanticized ideal of the open road and the practical reality of maintenance and repair, Kurland's work invites critical reflection on how freedom is experienced and the role of cars in American life.

Kurland's work has been widely recognized and celebrated, with exhibitions in museums and galleries throughout the United States and abroad. Her photographs are included in the permanent collections of institutions as a testament to the impact and influence of her work and the significance of her contributions to the field of photography.

Justine Kurland (ICP Lecture, 2014)

youtube

Friday, October 18, 2024

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early feminist analysis of rape exposed the myths that it is a crime of frustrated attraction, victim provocation, or uncontrollable biological urges, perpetrated only by an aberrant fringe. Rather, rape is a direct expression of sexual politics, an assertion of masculinist norms, and a form of terrorism that perseveres the gender status quo.

Femicidal atrocity is everywhere normalized, explained as "joking," and rendered into standard fantasy fare, from comic books through Nobel Prize-winning literature, box-office smashes through snuff films. Meanwhile, the FBI terms sex killings "recreational murder."

We too must be able to face horror in ways that do not destroy but save us.

We must now demand an end to the global patriarchal war on women. The femicidal culture is one in which the male is worshipped. This worship is obtained through tyranny, subtle and overt, over our bruised minds, our battered and dead bodies, our co-optation into supporting even batterers, rapists, and killers.

2 notes

·

View notes