#new left

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

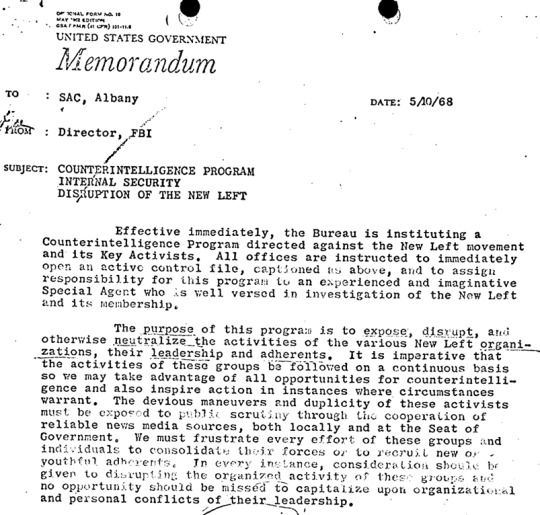

Ruh-Roh Raggy, Rointelpro.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Domestically, ribu was born through the contradictions of the radical political formations of the '68 era, including the anti-Vietnam War, New Left, and student movements. Many ribu activists had experienced the radicalism of the student movements and sectarian struggles of the New Left. As defectors from existing leftist movements, ribu activists were conversant and in critical dialogue with the ongoing struggles such as those of the Sanrizuka, Shibokusa, Zainichi, and Buraku liberation activists, the politics of occupied Okinawa, and other movements including immigration, labor rights, and pollution. Following other radical movements of Japan's '68, horizontal relationality was privileged in reaction to the rigid hierarchies of the established left and many New Left sects. The movement involved a decentralized network of autonomous ribu groups that organized across the nation, from Hokkaido to Ayashi; with no formal leader, its leading activists were Japanese women in their twenties and early thirties.

Ribu's birth was traumatic and exhilarating. Having experienced a spectrum of sexist treatment and sexualized violence while organizing with leftist men, from verbal abuse to sexual assault and rape, ribu activists revolted against the myriad ways that sexism and misogyny were endemic across leftist culture. Women typically supported male leadership through domestic labor, by cleaning, cooking, and other housekeeping duties. There were instances when young women activists were referred to as public toilets [benjos] and assaulted and raped by leftist male activists. In some cases, the rape of the women of rival leftist sects became part of the New Left's tactics of uchi geba [internal violence or conflict]. In 1968, Oguma Eiji describes such incidents of sexual violence. Ribu activists spoke, wrote, and testified about their experiences of sexism, assault, and rape at the hands of leftist male activists. Given such forms of sexual violence that were hidden, too often, in the shadows of Japan's 1968, how did ribu women respond?

Never before in the records of Japanese history had ink sprayed such rage-filled declarations of revolt against Japanese heteropatriarchy and sexist men. The slogans of the movement, like the "liberation of sex and the "liberation from the toilet" [benjo kara no kaiho], unleashed an unprecedented flurry of militant feminist denunciations. With minikomi (alternative media] titles such as Onna no hangyaku [Woman's Mutiny] and art evoking images of vaginas with spikes, ribu activists raised a political banner that had never been so explicit and bold in its declaration of sexual oppression and sexual discrimination.

Ribu activists reacted to the counterculture movement of the 1960s and the sexual revolution. Some of its earliest activists, such as Yonezu Tomoko, criticized the "free love" espoused by male activists even while they emphasized the importance of politicizing sex. Along with her student comrade Mori Setsuko, Yonezu named their cell "Thought Group SEX," and painted "SEX" on their helmets the first time they disrupted a campus event at Tama Arts University in Tokyo. Sex and sexuality emerged as key concepts in ribu's manifestos for human liberation. The politicization of sex was a revolt against the sexism in mainstream society and the Japanese left. Heralding the importance of liberating sex also distinguished ribu from former Japanese women's liberation movements, Tanaka Mitsu, a leading activist and theorist of the movement, harshly criticized previous women's movements, saying that the "hysterical unattractiveness" of those "scrawny women" was due to their having to become like men. The brazen and contemptuous tone of their manifestos was a stark departure from past political speech about women's liberation.

This emphasis on sexual liberation evinced ribu's affinity with US radical feminist movements that also exploded in 1970." Ribu activists recognized their shared conditions when they heard news of women's liberation movements emerging in the United States. Information about these movements flowed into Japan via news and alternative media, as documented by Masami Saitō. Japan's largest newspapers, the Yomiuri and Asahi Shimbun, printed photos of thousands of women protesters in the streets of New York City for the August 26, 1970, Women's Strike. Anti-war posters with defaced US flags decorated the walls of ribu communes and organizing centers." Activists from the United States and Europe visited ribu centers." This cross-border exchange among activists also characterized the internationalist spirit of '68 and a common desire for liberation.

Like so many others around the world, ribu activists were also inspired by the Black Power movement and attempted to follow its lead. This passage from a ribu pamphlet evinces how ribu activists were emboldened by Black Power struggles - as were radical feminists in the United States - and drew new lines of departure and separation from the leftist men with whom they had been organizing.

By calling white cops "pigs," Blacks struggling in America began to constitute their own identity by confirming their distance from white- centered society in their daily lives. This being the beginning of the process to constitute their subjectivity, whom then should women be calling the pigs?... First, we have to strike these so-called male revolutionaries whose consciousness is desensitized to their own form of existence. We have to realize that if we don't strike our most familiar and direct oppressors, we can never "overthrow Japanese imperialism"... Those men who possess such facile thoughts as, "Since we are fighting side by side, we are of the same-mind," are the pigs among us."

For leftist women to be calling leftist male revolutionaries pigs constituted a kind of declaration of war against sexism in their midst and their newfound enemy-sexist leftist men. When women of the left began to identify this intimate enemy, this moment of dis-identification with Japanese leftist men constituted a decisive epistemic break. Their conflict with sexist male comrades forced these women to recognize that they had to redefine their relationship to the revolution from the specificity of their own subject position."

- Setsu Shigematsu, "'68 and the Japanese Women's Liberation Movement," in Gavin Walker, ed., The Red Years: Theory, Politics and Aesthetics in the Japanese ‘68. London and New York: Verso, 2020. p. 79-82

#setsu shigematsu#ribu#revolutionary feminism#feminist history#patriarchal violence#heteropatriarchy#social justice#history of social justice#militant action#far left#new left#1968#japanese 68#japanese history#left history#academic quote#reading 2023

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I like to do little projects while I study whatever my brain decides is it's interest of the week - so to my fellow commies in the audience (love you babes ♡) I created this flowchart of socialist/communist parties in the United States!!

I made this over a year ago during the height of having COVID brainfog (please get your vaccinations besties it's not fun!). Please note that the inclusion of a group isn't an endorsement! There's some judgement involved in what exactly should be counted; some groups here are social democrats but have ties to more explicitly socialist parties, but at the same time I excluded reactionary groups that had similar ties, so it all comes down to my judgement that I might not even agree with any more but one-year-ago-covid-brain-me has decided and it. is. final.

I want to do a second revision to include the post-2000s Maoist movement (I have the Red Guards here but even then it's not really accurate to relegate them as an offshoot of the CPUSA), but for now here's revision 1 have funn!!

PS this isn't a live link and if you mess it up just reload, it's fine don't panic you didn't ruin it for anyone else

PPS I literally don't care if you use this or add to it or do whatever, I'd love credit because I love attention but go wild with it besties

PPPS if any of this is inaccurate please tell me because I want all the information that exists just be nice to me about it or else I'll cry

#communism#socialism#marxism#leftist#politics#flowchart#us politics#communist party#psl#dsa#cpusa#this is my first Tumblr post and I'm not sure what the hashtag etiquette is#what else can i put here#marxist#i guess i didn't put that one yet?#marxism leninism#trotskyism#new left#thatll get a few more people?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evil bastards! No surprise there, but still.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michael Shermer: Why I'm No Longer Woke

Source:Skeptic publisher & blogger Michael Shermer. Source:The New Democrat “Before the transmogrification of the word woke into the pejorative slur against far-left politics it represents today, I would have called myself woke—and even a social justice warrior—inasmuch as I believe in civil liberties, civil rights, women’s rights, LGBTQ rights, animal rights, and the continued expansion of the…

#2024#America#Authoritarianism#Collectivism#Communism#Far Left#Illiberalism#Marxism#Michael Shermer#Negative WOKE#New Left#Positive WOKE#Regressivism#Skeptic#Skeptic Magazine#Socialism#Statism#United States#Woke

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"ALWAYS HAS BEEN."

PIC(S) INFO: Spotlight on American anarchist agitation collective and/or revolutionary protest group, BLACK MASK, marching on Wall Street in the winter of early 1967 to protest the fiscal terrorist institutions of the American status quo in NYC, New York, USA. 📸: Larry Fink.

“The next target is Wall Street,” an anarchist collective known as Black Mask wrote in its January newsletter, 1967. On February 10th, around twenty-five members of the group, wearing black balaclavas and carrying giant skulls, took to the streets of the financial district and handed out this statement:

"WALL STREET IS WAR STREET...

...The traders in stocks and bones shriek for New Frontiers—but the coffins return to the Bronx and Harlem. Bull markets of murder deal in a stock exchange of death. Profits rise to the ticker tape of your dead sons. Poison gas RAINS on Vietnam. You cannot plead “WE DID NOT KNOW.” Television brings the flaming villages into the safety of your home. You commit genocide in the name of freedom.

BUT YOU TOO ARE THE VICTIMS!""

-- THE NEW YORKER, "Occupying Wall Street in 1967," by Rollo Romig, published on October 5, 2011

Sources: www.agenteprovocador.es/publicaciones/los-primeros-encapuchados-de-nueva-york, X, the New Yorker, PM Press, various, etc...

#Black Mask#Photography#Anarchists#NYC#Sixties#Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers#Anarchism#American Style#American history#Larry Fink#New York#Anarchist Collective#Wall Street is War Street#Revolutionaries#Up Against the WallMotherfucker!#60s Style#New York City#Anarchist Left#1960s#60s#Wall Street#Wall St. is War St.#Protest Groups#Larry Fink photography#Anti-war#War Street#Vietnam War#Agitators#New Left#Wall St.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[…] Anti-Zionism is part of a larger intellectual crack-up on the left with distant roots. There is now a kind of meeting point between simplistic post-modernism and simplistic anti-imperialism. This conjuncture can be called ‘the anti-imperialism of fools,’ a phrase that echoes the famous criticism of antisemitism on the left in the late 19th century by socialist August Bebel. When some on the left tried to blame ‘Jewish capitalists’ for Europe’s woes, he called it ‘the socialism of fools.’ Formulations of both the antisemitism of fools and anti-imperialism of fools depend on intellectual twisting and turning until somehow, no matter what, blame is ascribed to, respectively, Jews and Zionists. Ominously, that ascription is often there before the twisting and turning.

Opposition to imperialism and colonialism has always been part of any morally intelligent left-wing programs and should be. Decolonisation after World War II was of world historical importance. In many ways it culminated in Nelson Mandela’s heroic leadership of South Africa’s liberation from apartheid. But three decades later, the party he led is in miserable shape, as is South Africa as a whole, and it faces electoral decline. So, it seeks to make itself the moral leader of the ‘Global South’ and accuses Israel of genocide and apartheid but won’t condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It is a species of scapegoating and has attracted great support in parts of the world including from the western left. But those supporters are reminiscent of what a New York literary critic, Harold Rosenberg, once called (referring to New York intellectuals) as a ‘herd of independent minds.’

Nobody can take a walk in Tel Aviv or Haifa and see apartheid. Using such words is a vulgar, opportunistic misapplication of political terms, corrupting their content. If you believe that Israel is an ‘apartheid state’ then you can also believe that Donald Trump won the 2020 American elections and that Hamas with its Islamist supremacism is a force of liberation even if – well, sorry about that little slip by brave ‘resisters’ – they rape Jewish women.[…]

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

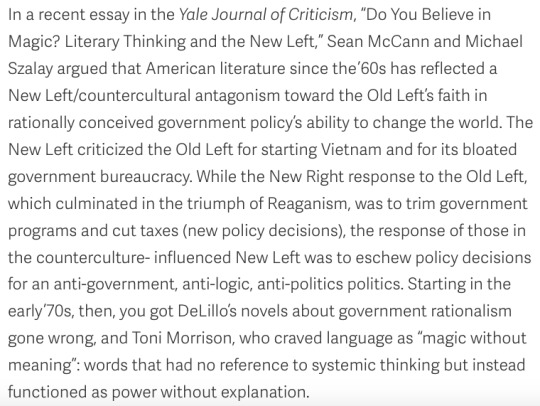

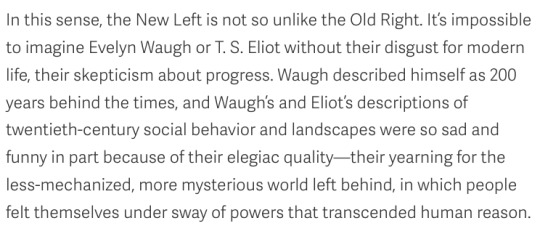

—Benjamin Nugent, "Why Don't Republicans Write Fiction?"

I found the above 2007 essay from n+1 by a circuitous route—I was essentially trying to decide if I should put Mark Helprin's Winter's Tale even on the long-range reading list—and admire the above paragraphs for articulating something I myself have been trying to say over the years about the inapplicability of the left-right distinction to the greatest works of modernist-postmodernist literature, about how if we can't appreciate the radical nature of T. S. Eliot and the reactionary nature of Toni Morrison, we're not going to understanding anything.

2007 was a long time ago. The Democratic Party is now the institutional heir to the neoconservatism of the Bush-era Republicans (for now), above all in its prostration toward the techno-security state or "deep state" that was such a major object of critique in New Left fiction from Dick to Pynchon to DeLillo. It's no surprise, therefore, that interesting fiction and culture in general, even in the teeth of current hegemonic left-liberalism's censorious turn as foreshadowed by McCann and Szalay's essay demanding political legibility and rationality from writers, has tended to come from those skeptical of this liberalism and aesthetically attracted to a populist right many of whose at least superficially anarchic convictions echo the now old New Left. This pendulum may swing again soon, however, with the rise of political figures like RFK Jr. (an actual throwback to New Left anti-authoritarianism on the left) and Ron DeSantis (a Bush-style neocon in unconvincing populist costume signalling the end of the Trumpian carnivalesque on the right).

P. S. Despite the progressive Nugent's magnanimity toward Helprin, Winter's Tale doesn't sound from the essay much like my type of novel. Please let me know, though, if I must read it.

#benjamin nugent#modernism#postmodernism#liberalism#leftism#conservatism#new left#mark helprin#t.s. eliot#toni morrison#literary criticism#american politics

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

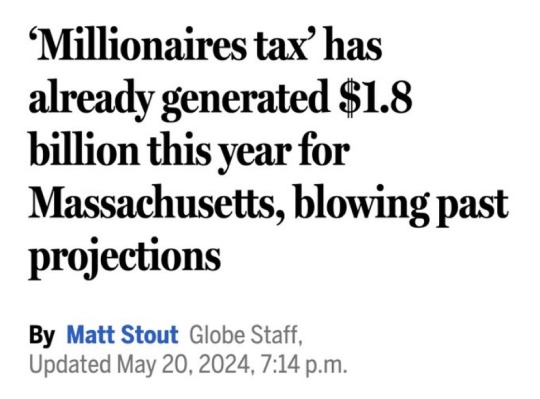

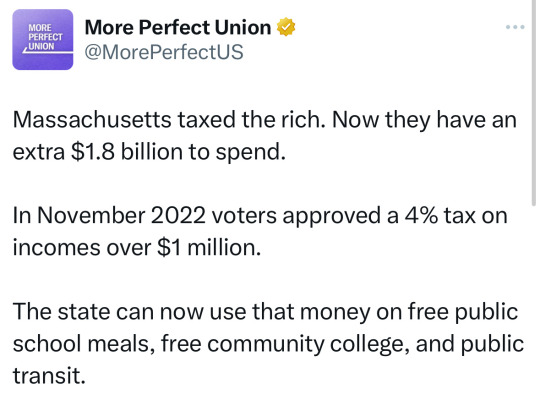

Source

#tax the rich#eat the rich#politics#us politics#government#massachusetts#the left#progressive#current events#news#billionaires should not exist#good news

129K notes

·

View notes

Text

shaking my head while playing neko atsume so people know that I don’t support outdoor cats

#I heard they made neko atsume 2 and I couldn’t decide which I wanted so I downloaded both#the nice thing is that 1 comes with a watch app so I can easily check if there are new cats without pulling out my phone#great for when I go to pee at work and realize I left my phone but still wanna procrastinate#but 2 you can visit other people’s yards???

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Ribu's anti-imperialist feminist discourse would later manifest in its solidarity protests against kisaeng tourism. This sex tourism involved Japanese businessmen traveling to South Korea to partake in the sexual services of young South Korean women who worked at clubs called kisaengs. Ribu's protests against kisaeng tourism represented how the liberation of sex combined with ribu's anti-imperialism and enabled new kinds of transnational feminist solidarity based on a concept of women's sexual exploitation and sexual oppression. From ribu's perspective, this form of tourism represented the reformation of Japanese economic imperialism in Asia. They were not against sex work by Japanese women, but opposed to the continued sexual exploitation of Korean women as a resurgence of the gendered violence of imperialism: Ribu activists hence connected imperialism and sexual oppression of colonized women to the continuing sexual exploitation of Korean women in the 1970s. In this way, they were able to expand the leftist critique of imperialism and, at the same time, point to the fault lines and inadequacies of the left.

In her critique of the left, Tanaka points to its failure to have a theory of the sexes.

Even in movements that are aiming towards human liberation, by not having a theory of struggle that includes the relation between the sexes. the struggle becomes thoroughly masculinist and male-centered (dansei-chushin shugi].

According to ribu activists, this male-centered condition infected not only the theory of the revolution and delimited its horizon, but it created a gendered concept of revolution that privileged masculinist hierarchies within the culture of the left. Ribu activists decried the hypocrisy of the left and what it deemed to be the all-too-frequent egotistical posturing of the "radical men" who "eloquently talked about solidarity, the inter national proletariat and unified will," but did not really consider women part of human liberation. Ribu activists rebelled against Marxist dogma and rejected these gendered hierarchies that valued knowledge of the proper revolutionary theory over lived experience and relationships. Moreover, ribu activists criticized what they experienced as masculinist forms of militancy that privileged participation in street battles with the riot police as the ultimate sign of an authentic revolutionary. While being trained to use weapons, activists like Mori Setsuko questioned whether engaging in such bodily violence was the way to make revolution. Ribu's rejection and criticism of a hierarchy that privileged violent confrontation forewarned of the impending self-destruction within the New Left.

...

News of URA [United Red Army] lynchings, released in 1972, devastated the reputation of the New Left in Japan, and many across the left condemned these actions. This case of internalized violence within the left marked its demise. Although ribu activists were likewise horrified by such violence expressed against comrades, many ribu activists responded in a profoundly radical manner that I have theorized elsewhere as "critical solidarity." Ribu activists had already refused to lionize the tactics of violence; hence, they in no way supported the violent internal actions of the URA. However, rather than simply condemning the URA leaders and comrades as monsters and nonhumans [hi-ningen), they sought to comprehend the root of the problem. They recognized that every person possesses a capacity for violence, but that society prohibits women from expressing their violent potential. In response to the state's gendered criminalization of Nagata as an insurgent and violent woman, ribu activists practiced what I describe as feminist critical solidarity specifically for the women of the URA. Ribu activists went in support to the court hearings and wrote about their experience and critical observations of how URA members were being treated. By visiting the URA women at the detention centers, consequently, ribu activists came under police surveillance. Ribu activists enacted solidarity in ways that were tot politically pragmatic but instead philosophically motivated. Their response involved a capacity for radical self-recognition in the loathsome actions of the other. Activists wrote extensively about Nagata - for example, Tanaka described Nagata in her book Inochi no onna-tachi e [To Women with Spirit] as a kind of "ordinary" woman whom she could have admired, except for the tragedy of the lynching incidents. In 1973, Tanaka wrote a pamphlet titled "Your Short Cut Suits You, Nagata!" in response to the state's gendered criminalization of the URA's female leader, the deliberate publication of such humanizing discourse evinces ribu's efforts to express solidarity with the women who were arguably the most vilified females of their time. Hence, ribu engaged in actions that supported these criminalized others even when the URA'S misguided pursuit of revolution resulted in the unnecessary deaths of their own comrades. Through ribu's critical solidarity with the URA, they modeled the imperative of imperfect radical alliances, opening up a philosophically motivated relationality with abject subjects and a new horizon of counter-hegemonic alliances against the dominant logic of heteropatriarchal capitalist imperialism.

While the harsh criticism of the left was warranted and urgently needed given the deep sedimentation of pervasive forms of sexist practice, it should be noted that, at the outset of the movement, there were various ways in which ribu's intimate relationship with other leftist formations characterized its emergence. At ribu's first public protest, which was part of the October 21 anti-war day, some women carried bamboo poles and wooden staves as they marched in the street, jostling with the police." Ribu did not advocate pacifism; its newspapers regularly printed articles on topics such as "How to Punch a Man." During ribu protests from 1970-2, some ribu activists-as noted, with Yonezu and Mori - still wore helmets that were markers of one's political sect and a common student movement practice."

- Setsu Shigematsu, “'68 and the Japanese Women’s Liberation Movement,” in Gavin Walker, ed., The Red Years: Theory, Politics and Aesthetics in the Japanese ‘68. London and New York: Verso, 2020. p. 89-90, 91-92

#setsu shigematsu#ribu#revolutionary feminism#feminist history#patriarchal violence#heteropatriarchy#social justice#history of social justice#militant action#far left#new left#1968#japanese 68#japanese history#left history#academic quote#reading 2023#critical solidarity#united red army#anti-imperialism#sex tourism

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New Left versus Marxism

I was a part of the U.S. New Left. I can’t speak for the UK New Left or, more broadly, the European New Left. The New Left also extended beyond Europe and North America.

We were a mix of people. Some were associated with a particular Marxist or anarchist tendency. Others were not. I was, as might be expected from my age at the time, in the final category. At 12-years old, the New Left (the Students Democratic Coalition) in my junior high school (now called “middle school” in most places — except for where I live) introduced me to radical politics.

I don’t think that any of us in my school were actually Marxists or anarchists per se. Honestly, if someone had asked me back then to define Marxism or anarchism, I would have been clueless.

I did, however, consider myself to be a communist. Much of our work was focused on emancipating the Mexican migrant workers in California. (Sadly, we failed.) So I began as a Third Worldist; and I am a Maoist-Third Worldist today.

Some people have criticized the New Left, unfairly in my opinion, for not having a strong theoretical grounding. That is an over-generalization. I wish I knew where it originated. My guess, however, is that, whoever came up with the idea, they were not involved in the New Left.

Many, mostly university and college students, were committed Maoists, Trotskyists, classical Marxist-Leninists, autonomist Marxists, left anarchists, etc. Regardless, the New Left is all we had. We did the best we could.

Marxism, or really the Marxisms (some prefer marxisms), is a collection of theories inspired, to one extent or another, by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels along with their successors. That is to say, there are many different Marxisms.

As with most theoretical traditions, after the founder or founders died, Marxism has moved in numerous directions. My own Marxism is a composite of Bhaskarian critical realism and intersectional Marxism (not to be confused with legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw’s progressive, and non-Marxist, intersectionality).

Most Marxist communists, such as myself, are not fans of progressivism (Bernie Sanders, AOC, etc.). There is no love lost between Marxist communists and progressives. We have very little in common. Although, anecdotally, progressives appear to like us more than we like them. 😁

0 notes

Text

The New Left Party had a magazine called 'Comet' which was produced to promote the New Left Conference. It ran for one year, from 1989 to 1990.

#communism#socialism#marxism#leftism#communist#leftist#marxist#socialist#anti capitalism#dismantle capitalism#new left#new left party#auspol#australia#australian history#new left conference#leftwing

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bernard Goldberg: When Even Murder Is Tolerated

Source:Bernard Goldberg with a left at militant-left “rockstar” Luigi Mangione. Source:The New Democrat “Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg said Thompson’s death on a midtown Manhattan street “was a killing that was intended to evoke terror. And we’ve seen that reaction.” —AP News Report It didn’t take long, did it? Brian Thompson, the CEO of UnitedHealthcare, was shot and killed, and before…

#2024#America#Baltimore#Bernard Goldberg#Brian Thompson#Far Left#FBI#Health Care#Luigi Mangione#Manhattan#Maryland#Militant Left#New Left#New York#New York City#Socialists#Southern District of New York#U.S. Department of Justice#U.S. Government#United Health Care#United States#Washington#Washington DC#Woke#WOKE Left

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reedición en formato fanzine del texto "La Nueva Izquierda", escrito en 1969 por Miguel Grinberg, poeta beatnik, cronista independiente de la insurrección interior y activista contracultural argentino. El texto fue publicado como prólogo en la edición argentina de La Sociedad Carnívora de Herbert Marcuse, traducido y editado por Grinberg a través de su editorial Eco Contemporáneo. Las fotos que acompañan al fanzine conforman el archivo digital Las Llamas del Cordobazo, elaborado por LaTinta.com.

Aquí puede visualizarse como pdf Aquí puede descargarse en formato fotocopiable

#Miguel Grinberg#Grinberg#fanzines#new left#contracultura argentina#contracultura#beatnik#nueva izquierda#Cordobazo

1 note

·

View note