#it's the sort of thing where actually authorial intent *does* matter

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

.

#it's like. this short comic has lived in my head rent free for going on a year now and it is probably the most disturbing comic#i've read in a really long time and it's so difficult to parse how i feel about it bc it feels laden with such visceral intent#but i just cannot figure out what that intent actually *is* so i'm just kinda stuck with this horrible feeling not knowing what to do#with it bc i'm not much for authorial intent post-publication but in this case? god *damn* do i want to know what the intent was#bc it could be playing shock and horror for the sake of exploitative shock and horror but it feels so personal at the same time#i won't call it lived-in but it feels like processing something that has happened adjacent idk idk#maybe it's that it's such a short thing but it punches like a freight train to the gut and leaves a sick cold horror and i don't even know#what the intent behind it was and that bothers the everliving fuck out of me#it's the sort of thing where actually authorial intent *does* matter

1 note

·

View note

Note

hi i didn’t know what Star Trek was until i came across your fic it’s so. Real. poor McCoy bruh nobody’s gonna know what he went through …I guess it’s not entirely gone, but still. He didn’t get the three socks metaphor.

YOU TRICKED ME. canon divergent LIEEE LIEEEE

The way you omit time travel as a tag is craaazyy (I love time travel) AND AND THE SUNMARY BEING

“About men who love each other” LIKE NOT TWO MEN but all THREE

I do have one question though. If McCoy said “tell him you missed him” and set up the holo night, then in the first timeline had McCoy already gone back at that point and failed?

Hi! So I saw your comment on AO3 (please forgive me if it takes a moment to reply, I have an enormous backlog of comments to get around to after I took a break when the fic ended!) and I knew I absolutely had to ask you these burning questions: how did you find my fic if you didn't know what Star Trek was? What inspired you to read it?

I am beyond thrilled that you enjoyed the story and so touched that you read it all the way through without having seen Star Trek, but I absolutely have to ask what the story behind this is if you're willing to share with me!

It's definitely still canon divergent in a sort of way! At least in my figurative and literal book if you know the episode that inspired this novel, it would definitely be considered divergent:) I wanted to keep things as spoiler-free as possible to retain the surprise and emotional weight of the story, so I made the decision early on to not tag where the plot or ending was going, which definitely threw a lot of people off! Sorry for the trickery!

I ADORE that you pointed out the summary. I was actually shocked when I was reading this ask, because it was absolutely intentional and a huge part of the foreshadowing, but you're the only reader to my knowledge that has consciously noticed that choice, and you haven't even seen Star Trek!! Amazing!! I have such a big smile on my face right now!

More below because I realize this is getting long already!

As for poor McCoy, it is truly tragic nobody will know what he went through. In Star Trek, a lot of fans (rightfully) emphasize the love between Kirk and Spock, which I feel is only kept alive because of McCoy's quiet love for them both in the background as he takes care of them. In a way, it's a tribute to love that goes unnoticed, unseen.

With regards to your question, it's a great question! And I don't have a perfect answer for it, because it's entirely paradoxical. The first half of the story can only happen if the second half happens, because Kirk and Spock would not act on their feelings without the existence of the holo night and McCoy's intervention. But in the original timeline, they still die even though McCoy's actions in the latter half of the novel seem to exist. It's totally circular. It's expounded on somewhat in Forever and a Day, where McCoy tries to make sense of the same question and concludes that even if he does succeed, they will still die.

McCoy tries not to think about the horrifying implications. The knowledge that no matter what he did, he could not undo their deaths. To live, they would always need to die.

This doesn't necessarily mean that McCoy has gone back before, but it raise some serious questions about metaphysics and leaves a lot unanswered, because the two events now cause each other, and they also contradict each other. I actually took a stab at explaining the metaphysics in way greater detail in the fic originally, but my beta reader (correctly) told me this would confuse readers. So because it's confusing, I later just wave my sci-fi authorial wand to try and convince you to go along with it! :)

"And I like how the paradox makes no sense.” “I reckon it’s not meant to. They never do."

I do have to say, I recommend giving Star Trek a watch if you were interested! I think it's an amazing show. Again, thank you so much for taking the time to read a whole novel about a show you had no idea about!!

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.tumblr.com/olderthannetfic/729708592592306176/how-about-a-different-discourse-death-of-the

What this ask is missing, a bit, is that Death of the Author *does* mean that the author’s take on things is no more or less valid than anyone else’s. It’s about decentering authorial intent in analyses of media. Barthes is pretty clear and quite pointed about it in the original essay.

What bothers me about misuses of it and what I think this anon means to say is when people start decentering the actual *text*. The idea behind Death of the Author is also that the text stands alone. You don’t need to look at any extra shit to understand it. As you said, it was a response to a mode of analysis that obsessed over plumbing through author biographies.

The issue with what people do in fandom is they ignore the text. “I don’t like this element of canon, so it doesn’t exist.” (Which is different from arguing that it’s there but it sucks because of XYZ reasons, so I’m going to consciously ignore it in my fan works. This is when people just act like it isn’t there in the text in the first place.) “You have to take my bizarro world out-of-nowhere headcanon that is based on nothing except that I want it to be true, that I love this character and I wish they were XYZ therefore they are” and take it just as seriously as headcanons that actually engage with what’s in the show/video game/book/movie/whatever and use that as their basis (like building off something that is subtextual in the original work).

Granted we all do this to some degree, we all come to a text with our own biases and you can’t *always* easily separate those out, and that can affect, for instance, your interpretation of what the subtext is, but I think the irritating fandom behavior is when this kind of ignoring-the-text-to-substitute-your-own-reality is this very deliberate sort of laziness. The annoying thing in my current fandom is people who are fans of this one ship that they insist is the most progressive and other people just don’t see the scintillating “subtext” of because we are bigots or whatever, between two characters who don’t interact that much for two MCs and when they do it’s not at all shippy (but these characters both have very shippy subtext with different characters), but where these people think the ship *should* exist because of their identities. And their “evidence” for the ship is always gifsets taken way out of context and not including the dialogue that makes the non-shippy context for that scene very clear (including that it might actually be shippy for conflicting pairings). It’s like this bizarre version of “close reading” that strips out the largely context *deliberately* in order to make a particular conclusion seem more compelling than it actually is.

Anyway, all that ignoring-the-text stuff is STILL bad analysis per DOTA. Since the point of DOTA is to go based on the text, if you’re obscuring the text you’re kind of just installing yourself as a new author.

This is why DOTA doesn’t mean “anything goes.” It just means “authorial intent is just one interpretation that doesn’t have to matter.” It doesn’t mean other stuff we use in analysis doesn’t matter, and if anything the point is to make it even more text-centric than the older author-centric analyses were. People can still disagree about what the text says, of course, but they should both be going back to it in how they construct those arguments, and not, like those shippers, deliberately ignoring chunks of the text that weaken their arguments.

--

I don't think all of them are consciously throwing out actual canon, but they are often throwing out all context that would help evaluate subtext.

Like... if you're analyzing a Marvel movie, you might ignore what the director said in an interview, but you probably shouldn't entirely ignore the fact that it is a Marvel movie and apply assumptions that make sense for some arthouse film.

And, yes, if you're arguing for shippy subtext, even unintentional on the part of creators, "I like this ship because..." needs very little, but "This ship has more support than this other ship" requires going back to the actual text and looking at it in its totality.

There's a lot of faux-intellectualism around garbage like TJLC where people try to make themselves feel smart by using the language of close reading while having the media literacy of a bucket of rotting fish.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve seen all sorts of posts about what people miss about fandom in ‘the old days’ and ‘old time fanfiction’, so I thought I’d do one myself. You know what I miss?

I miss the threat of cease and desist orders.

And before you go “Ah, yes, another post on how we were getting away with so much!” let me stop you right there by pointing out: we weren’t getting away with shit. Anne Rice made that very, very clear. Everything that we ‘got away with’ we ‘got away with’ because the creators themselves supported fan fiction or, at the very least, didn’t bother to come after us. Anyone who decided to shut us down had but to call their lawyers and we were toast.

So what was so good about that, you ask? What was good about the continual worry that it would all go south? If we weren’t part of the Glorious Rebellion Against The Creator?

One word: Manners.

The rest of the fandom could be as nasty a bunch of bullies as they liked. They could write essays on how their high school physics instructor told them it was impossible to fly on a magic broomstick and how that knowledge made them so superior. They could bully actors into giving up their careers or, better yet!, contemplate suicide. They could be as intolerant and unforgiving and demanding as they liked, but the writers?

We had to at least pretend to respect the creators and view them as actual people. We needed our disclaimers saying “I own nothing except my student debts and a pile of dirty laundry! Please, oh creator, do not break me open like a bag of groceries and dance on my sticky bones!” No, really, those were things people actually said in their disclaimers. We needed those to keep ourselves safe.

Unlike the rest of the fandom, we could not take that safety for granted. We couldn’t afford it. Thought something should have been done differently? “I get where the author was going with this, but I’d have like to have seen it done this way instead”. Thought a scene would have been more interesting from the view of a side character rather than the main? “I thought I’d explore this through the eyes of John Doe over here.” We could still write everything we do now, and for all of the same reasons, but we could not get away from the fact that the creator was a human being who had reached into their skull and pulled out something that inspired us.

It protected us in other ways too. When people came at us complaining that fan fiction was disrespectful to the author, we had a thesis paper’s worth of disclaimers: disclaimers thanking the author for their work; disclaimers promising the reader that we were just having fun; disclaimers saying in plain words that this was not to be taken seriously, but was written as finals-week-therapy at three-bloody-am. Even the people who were lying in their disclaimers, who really did look on the creators as the lowest form of life, had to pretend to have respect and that, in turn, made sure they could never completely overlook the truth of the matter: without the creator, they wouldn’t have anything to write about.

We were Emperors and the threat of a law suit was the man following us in the parade, whispering in our ears: Remember, one day you will die.

It kept us humble.

It kept us respectful.

It kept us, to some degree, empathetic. After all, we were writers too, weren’t we? We were just having fun, mind, or practicing our writing, or whatever, but the important part was that we were all writers.

Maybe it’s a reflection of the people I spent time with, but it showed in our meta too. When talking about characters, the other fans might sprinkle their posts with snide comments about authorial intent, but we stuck to observations about the characters themselves. “But of course, the creator didn’t think about that” was again a non-writer line. If we wondered what the creator had been doing in a particular plot, it was because we were genuinely curious and wanted to know, not because we wanted to look clever. If the creator ended the series like a Shakespearean comedy rather than a John Webster piece, we didn’t sit around debating the likelihood that the whole cast would be eaten by a rabid rhino the second the credits stopped rolling, because really, let’s look at the creator’s history here. We celebrated our happy ending.

We had conversations because we wanted to enjoy things. We were in the fandom to have fun, period, end stop.

This was really important when I was in my twenties and working on getting a B.A. in Creative Writing. The idea of publishing, particularly in a pre-self-publishing craze, was daunting. Basically everything the big publishing houses put out were novels. That was a lot of work, a lot of revision, a lot of money for editors and agents and shipping things around. You were looking at a lot of rejection, so much so that writers like Steven King gave advice in interviews and autobiographies on how to deal with the sea of ‘sorry, not interested’. And it wasn’t much money, usually. The idea that, if you made it, you could wind up with millions of ‘fans’ bitching about how the book you got on eating disorders in 1893 had given you bad information and calling you a no talent, idiotic hack because you believed it was enough to make someone just give up and go into landscaping. However, the knowledge that people might be inspired to write their own things based off of your work, that they might recognize you as the source of their inspiration, and that there might wind up being a communal, living body of work based on something that you pried out of your brain….that was exciting. That was worth it. That made being part of a fandom and the thought of having one of your own encouraging and fun and supportive.

To twenty something me, that made being a published author seem like an infinitely better job than packing groceries.

Then we got lawyers. We got rights. That should have been a good thing, and in ways it is, but we now have the privilege of being entitled, spoiled bullies like the rest of the fans, and God forbid we not make the most of our privileges. ‘Having fun and enjoying the thing’ has given way to ‘find as many things to be dissatisfied about as possible’. Telling the nay-sayers ‘no, we’re all just having fun’ has turned into a battle to defend our hobby against someone armed with a list of fiction summaries along the lines of ‘fixing the plot because the author is a no talent hack who couldn’t write their way out of a wet paper bag!’

Forty something me packs groceries for a living and plans on doing it until I retire. Yeah, self-publishing is a thing now, and I’m financially stable enough to do it. I could finish a rough draft (Hell, I have one that’s probably good enough to pitch at an editor), hire someone to help me clean it up, and get it out into the world.

I just don’t want to. It might do well, and then what? I get to hear all about how I’m an idiot because side plot B didn’t make sense to five people? About how someone had a great revelation about character C and it’s a pity I couldn’t be clever enough to have actually thought about it myself? About how they know that my story is really super cringe, but they found a way to think about it that I never intended and actually makes it good? About how all of the problematic parts are clearly because I’m majority? (Well, you know, mixed status, but that just means ‘worst of both worlds’.)

Working retail I have to put up with a constant stream of superior people being nasty and critical, but I don’t have to spend more money than it takes to drive to work. I don’t have to let people see my thoughts and dreams. I don’t have to hand them characters that I’ve poured hours of thought and care into, developing them to be the best, most human people I can manage, only to have them run over with steamrollers and be criticized for making them so flat.

Not to mention it pays better.

No, really. People assume that once you’ve published a book or worked on a TV script, you’re set for life, but I’ve already made more money this year boxing groceries than a bottom tier novelist. And before you say ‘oh, but the bottom tier is practically unknown and doesn’t need to worry about fans’, that is not the point. The point is that a lot of well known creators have second jobs. They still get routinely attacked by people who claim to like their work.

It’s not encouraging anymore. It’s not supportive. And I’m sure there are people out there all ready to say ‘Oh, but with you it will be different because-” no it won’t. I’m not that special. I’m not special at all, except in that way that everyone is a unique and special individual, and that statement applies to every human being in history, including the genocidal maniacs.

There are days I’m not even sure why I bother with fan fiction anymore, except that I want to write and this is what’s inspired me. Half the time it feels like people just see my comments section and go ‘Ah yes! A fresh forum to complain about the creator!’ or my meta and go ‘Oh yeah! I can add to this, and get in a few digs on the creator to boot! Gee, I can’t believe you forgot that part!’ And I want to get better at writing and that requires feed back and being able to ask people who have different specialties than I do how things work and…

I just want to be able to enjoy talking to people about things again. I want to be able to read a great observation on a character and not have it ruined by the obligatory “But of course, we have to take into account who’s writing it!” comment. I want to be able to see a story with an awesome looking summary that isn’t labeled “fixing what the creator ruined by being a no-talent hack”. I want to be able to see I have a comment and not have to hold my breath that it’s yet another person complaining about what a horrible, awful thing the creator did by writing a scene that makes me feel represented in a way nothing else ever has and how much they hate it and of course I hate it too, right? I want to not feel bad about supporting a fan author knowing full well that they’re writing because they think the original creator sucks and will interpret everything possible in a way that reflects badly on them.

I’m glad we have the right to create fan works without fear of repercussions, but I’m really not sure we deserve it.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The shifting narrative of God’s interventism and how it reflects on the narrative on John

This post will ignore the issue authorial intent entirely because I can, but it’s also about authorial intent in a way, but I also don’t like to talk about things as happening “accidentally” because a) a serialized story like Supernatural, especially one that got renewed for much longer than anyone could possibly expect or hope in their wildest ambitions, structurally relies on serendipity, because that’s how stories work when they’re work in progress, b) a television show is an extremely multi-authored text and the chance that something happens out of the intent of any of the multiple layers of creators is kind of... statistically negligible. So, yeah, that’s my stance on the topic. Anyway.

The shifting narrative about God is simultaneously something that hangs on fortunate storytelling clicks on an essentially programmed narrative. At first, we don’t know where the fuck God is. Cas starts looking for him with little success. Raphael says he’s dead, Cas doesn’t believe it. Dean relates to his struggle because he knows the feeling of not knowing where the fuck your father is and going looking for him with little success, not knowing if he’s even alive. Then the theory that gets assumed as the truth is that God has left. He fucked off who knows where, who knows why, leaving his creation to struggle alone. Also essentially how Dean had felt after John had died; in that case there was guilt for his demon deal and everything, but the most cruel weight on Dean’s shoulder was that John left him alone to struggle with his devastatingly horrific instructions he doesn’t understand. The angels are also left with horrific instructions they don’t understand. No wonder Cas does his own ‘demon deal’ in season 6, as he desperately tries to do what he assumes his father wants from him, but he doesn’t actually know what that is.

“God has left” is maddening, and everyone is angry about it, but it has its own dignity. God has left us without clear instructions, we are confused and in pain and evil runs amock but at least, we suppose, the evil of it is our own doing. We are alone and we do our best, our best is simply not enough. We wish he gave us guidance, but he won’t. He wants us to figure it out ourselves, possibly. We don’t actually know what he wants. But maybe that’s the point. It’s possible he doesn’t even know what’s happening, he just has left the building entirely.

But then Chuck reveals himself. We find out that he never actually left. He was there. “I like front row seats. You know, I figured I’d hide out in plain sight”. He simply chooses not to intervene. He chooses not to answer. He chooses to be hands-off. He presents himself as a laissez-faire parent, because, he says, it’s better for his children to have the responsibility they need to grow up. He’s absent, but in a different way than we thought! It’s not that he doesn’t know what’s happening or isn’t interested in knowing what’s happening. He’s here, he knows what’s happening, he just stays there and watches as you stumble and struggle and scream. It’s worse, and it pains Dean so much he isn’t even afraid to yell at God. You know we’re suffering and you just don’t give us any support, any comfort.

You’re frustrated. I get it. Believe me, I was hands-on, real hands-on, for, wow, ages. I was so sure if I kept stepping in, teaching, punishing, that these beautiful creatures that I created... would grow up. But it only stayed the same. And I saw that I needed to step away and let my baby find its way. Being overinvolved is no longer parenting. It’s enabling.

But it didn’t get better.

Well, I’ve been mulling it over. And from where I sit, I think it has.

Well, from where I sit, it feels like you left us and you’re trying to justify it.

I know you had a complicated upbringing, Dean, but don’t confuse me with your dad.

At that point of the show, the writing team almost certainly didn’t have the s14-15 twist in mind. So this was probably intended to be Chuck’s truth. Later it gets twisted (retconned?) into a lie, but about that later.

Here, Chuck is really good at manipulating the conversation. Dean has a perfectly valid point, because there IS a middle ground between being overinvolved and not being involved at all. There is a middle ground between enabling your children and abandoning them completely. But Chuck hits Dean where it hurts, plays the emotional card, basically tells him that he’s too emotional to understand, too emotional to think rationally about it, because he mixes his feelings about his father to the issue and thus cannot see it clearly. He basically tells him he’s too close to it to get it. You don’t understand parenting, Dean, because you’re too blinded by your emotions about your own little life and cannot see the big picture.

It doesn’t really matter here if he’s telling the truth or lying, it already says a lot about Chuck that he’s emotionally manipulating Dean, silencing him by hitting the painful spot.

But the thing is, 11.20 immediately presents Chuck as a liar. He makes Metatron read his autobiography and the very first line is a lie (“In the beginning, there was me. Boom – detail. And what a grabber. I mean, I’m hooked, and I was there.” “I’m hooked too, and yet... details. You weren’t alone in the beginning. Your sister was with you.”) and the stuff he talks about his experience as Chuck is not exactly truthful about anything (“That, you know, makes you seem like a really grounded, likable person.” “Yeah, what’s wrong with that?” “You are neither grounded nor a person!”). Metatron calls him out (“Okay. There are two types of memoir. One is honest... the other, not so much. Truth and fairy tale. Now, do you want to write Life by Keith Richards? Or do you want to write Wouldn’t It Be Nice by Brian Wilson?”). Chuck SAYS he chooses truth and gives Metatron a different manuscript, supposedly containing the truth, to which Metatron reacts positively. Metatron believes it, and we believe it with him.

Oh! Oh, this! This is what I was talking about. Chapter Ten “Why I Never Answer Prayers, and You Should Be Glad I Don’t”, and Chapter Eleven “The Truth About Divine Intervention and Why I Avoid It At All Costs”.

Nature? Divine. Human nature – toxic.

They do like blowing stuff up.

Yeah. And the worst part – they do it in my name. And then they come crying to me, asking me to forgive, to fix things. Never taking any responsibility.

What about your responsibility?

I took responsibility... by leaving. At a certain point, training wheels got to come off. No one likes a helicopter parent.

This is sort of what he later says to Dean, except that to Dean he talks about “beautiful creatures” “my baby”, talks about helping, none of the harsh tone he’s using here. When Metatron accuses him of hiding from Amara, he retorts “I am not hiding. I am just done watching my experiments’ failures”. What a different language, uh? Then Metatron asks him why he abandoned them, and Chuck answers “Because you disappointed me. You all disappointed me”. Then, he admits he lied about “learning” to play the guitar and so on, because he just gave himself the ability, and then appears to Dean and Sam, after Metatron’s passionate speech about humanity.

So, no matter the authorial intent at the time - the truthiness of Chuck’s words was already ambiguous. He kept lying and being called out, or silencing the conversation with some good ol’ gaslighting.

The season 14 finale introduces the big twist: it was, indeed, all a lie. The whole of it. Chuck didn’t abandon shit. It was all him, minutely controlling the narrative of the universe, putting the characters through all the pain and struggles for his own amusement.

The “absent father” narrative was a lie.

What does this tell us about John? Nothing, according to the authorial intent that shines through Dabb’s Lebanon. But we don’t give a crap about Dabb’s authorial intent about John! He’s just one dude and plenty of other authors have painted a different picture. So I’m going to read the narrative the way I want, because I can, and the narrative allows me to. It’s all there.

I’m suggesting that the fact that Chuck lied when he talked about being a hands-off/absentee father parallels how Dean and Sam prefer to think of their father as an “absent father” when that’s not exactly a reflection of the truth.

You left us. Alone. ‘Cause Dad was just a shell. [...] And I-I had to be more than just a brother. I had to be a father and I had to be a mother, to keep him safe.

Setting aside how “I had to be a father and I had to be a mother” sort of retcons and cleans up the Winchester family picture painted by ealier seasons, the fact that John didn’t really count as a functional father figure and Dean and Sam were essentually alone is not incorrect or anything. It is true that John would leave them to their own devices a lot, thus the long stays in motels, the hunger, the food-stealing, and all. But John wasn’t always absent, at all. He trained them as soldiers, he disciplined them, he was around enough for them to be intimately familiar with what happened when he drank. He drove them around.

It’s almost like it’s preferable to Dean and Sam to spin their own “absent father” narrative, putting the accent on the time they spent alone, painting their childhood as a time they had to grow up on their own, rather than acknowledge they grew up under the thumb of a controlling, looming figure they would regularly live in fear of, even when he was not physically present.

The “absent father” narrative is what Dean and Sam need to use to avoid confronting the reality of the father figure whose moods and whims they had to dance around. “I know things got dicey... you know, with Dad... the way he was. And I just... I didn’t always look out for you the way that I should have. I mean, I had my own stuff, you know. In order to keep the peace, probably looked like I took his side quite a bit.”

John shaped their lives. He shaped their identities. Even in the episodes where he abandons Dean or both children somewhere, he’s portrayed as the figure who drives the car. He symbolically drives the car, you know? John shaped Dean and Sam’s relationship with each other, both on a surface level (the conflicts) and on a deeper level (the parental dynamic).

Heck. The entire first season of the show plays on John’s disappearance as the “elephant in the room”. John is there by not being there, you know? And after he dies, his death - his absence - is again the elephant in the room for Dean, the weight on his psyche that he shatters under.

It is not wrong that Dean and Sam had to spend long periods of time without John. But John structured their lives in quite minute detail. Where they needed to be, what they needed to do, what they must not do, everything had to follow John’s instructions. A drill sergeant, the narrative called him, ordering how his sons needed to live their lives. That’s no absence, except on a level where Chuck not showing himself and pretending he’s not there can be considered absent. That’s a presence, not necessarily always physical, but semiotical and psychological.

John is an absent father as much as Chuck is a hands-off god. He even writes himself into the story around the time Cas has the “season 1” phase (let’s go look for dad/let’s go look for god), which is when John actually was alive and appeared. Then he was no longer physically there, but he was still shaping his characters’ lives, just like he’d always done.

The “absent father” narrative on John is that - a narrative. Spun by the characters themselves because it’s easier and actually kinder on John. Or, better, it allows them not to be crushed by the psychological implications of having to accept that their father was such a looming, minutely formative figure in their lives. They know, but they can wave the “absent father” idea around to avoid thinking about it.

“I had to be a father and I had to be a mother” is something easier to tell yourself. I was the one who did it all. But he wasn’t, and that’s the problem. The fact that John was their father - Dean’s and Sam’s - is the problem. But ironically, blaming himself for every failure is a better option for Dean than fully acknowledging John’s abuse. As long as he blames himself, he has control over it. The moment he acknowledges the extent of John’s influence, he loses control over the entire narrative of his own identity and the family identity, the family dynamics. That’s scarier, just like realizing that God manipulated everything is much scarier than the alternative. “God abandoned us” was indeed a better option, and “John left us alone” was a better option. But neither was true, and the characters faced the implications of the cosmic level, but never got to face the implication of the familial level, because the narrative always danced around it and then Dabb’s apologist version “won”.

But what’s been put in the show is still there. The narrative of John’s abuse is still there. Nothing can take it out of the story.

#my spn thoughts#spn meta#dean and john#dean and sam and john#dean and chuck#dean and god#spn 11x20#spn 11x21#spn 14x20#spn 12x22#et alii#spn#long post

579 notes

·

View notes

Note

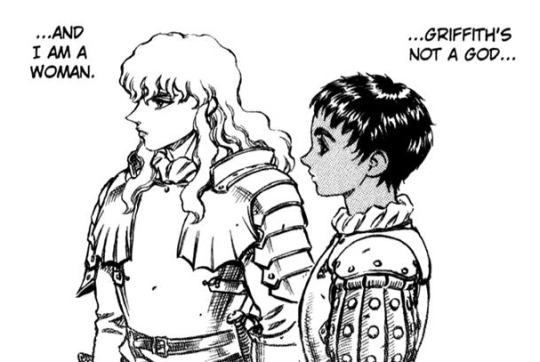

I wanted to touch on the whole gutsca thing with someone (I know zero people in this fandom so you're my lucky pick!). Am I alone in feeling like their first time together came out of no where? My meta with Guts is that he was not at all comfortable with sex at that time of his life (this instance being his first time [outside of the rape he experienced as a child]). His choice of words too, "here I go", translated to me like someone only doing what they felt was expected of them rather than something he was yearning for. He clearly wasn't even ready given how rough he was and how he regressed and attacked her. This moment seemed very forced and almost rang to me like Kentaro's declaration of "no homo though". I would be curious to know how Kentaro felt about homosexuality (bisexuality, etc) and if he ever addressed the ever blatant gay tension and romantic-non-platonic-love blossoming between Guts and Griffith pre-eclipse. I do get the sense that this may be a case of severe queer baiting or perhaps a PSA against gay love altogether ("falling for a man will literally destroy you and send you and everyone you love to hell" type of message); but I'm a very jaded person so I hope to be proven wrong. Sigh, my point being Gutsca seems pretty dang forced and empty of true development. I buy them more as besties than anything romantic. Especially since both he and Casca are actually in love with Griffith (what a fucking triangle!). Does anyone in fandom have any opinions on the sad possibility of this whole beautiful and ultimately tragic love between Griffith and Guts actually being a fucked up anti-gay PSA? Are there any interviews with Kentaro shooting this theory down so I can stop being sad and bitter about it? What are your thoughts?

Thanks for sending this, I'm definitely down to talk about it! I hope you connect with more people in the fandom but don’t worry about sending random asks even if you do lol.

Anyway you’re definitely not alone. I have a lot of thoughts on Guts and Casca's hook up, and they're all pretty much "it feels really forced and not particularly romantic but I think you can argue that that's deliberate" lol. For instance I discuss in a lot of detail here how various aspects of the scene indicate that Guts and Casca having sex is shown to be a case of both of them rebounding from Griffith and sort of giving to each other what they were unable or failed to give to him.

And I talk a lot about how Judeau essentially orchestrates it all and what that suggests about Guts and Casca's relationship here.

And lol sorry for all the links but also this post is about how their relationship feels one-sided to an extent and is used to illuminate a lot of Guts' flaws, using Judeau as a comparison point.

Oh shit and also one more lol, here's a comparison between the sex scene and Griffith's with Charlotte that suggests that both start as ways for the dudes to repress their feelings.

(Don't feel obligated to read all those posts if you don't want, you should get the gist of what I'm saying w/ those descriptions.)

But yeah basically I do think that Guts and Casca getting together felt forced and awkward. At best it might be intended to be seen that way, as two friends hooking up awkwardly in an emotionally intense moment but probably doomed to failure because neither of them are ready for a relationship with the other, or particularly interested in one deep down, once they finished "licking wounds." At worst it’s just bad writing lol. But again like I think there are good arguments for the former.

I also totally agree that their relationship has a strong vibe of doing what's expected. Like for real, at least to me both Guts and Casca read so easily as gay and repressed lol. Casca talks about her feelings for Griffith in terms of “he was a boy she was a girl can I make it any more obvious”

and I can’t help but see it as Casca like, wow I have strong feelings towards Griffith, he’s a man and I’m a woman, so clearly these feelings must be romantic, there’s no other option. Then when she has sex with Guts she keeps contextualizing it essentially as repayment for Guts saving her, like she owes him. “I too want a wound I can say you gave me.” “Not just being given to... maybe I can give something as well.” Which just doesn’t make her desire for him look all that genuine lol.

And then you have Guts. The way he tells Casca that from the start only her touch was okay with him after he has sex with her, referencing the scene when he wakes up with her on top of him and starts to panic before realizing she’s a woman, is soooo suggestive of repression to me. Like, first off because it’s incorrect, he was also okay with Griffith going in for a face-grab after winning a duel Guts had been projecting his rape trauma all over, which seems like a pretty conspicuous omission. And secondly because the reason he was okay with Casca’s touch specifically is solely because she’s a woman, not because she’s special or because they have a magic romantic connection - it’s because she’s not a man. To me that just screams that Guts was open to sex with Casca because she’s the only woman he knows, and he’s afraid of the idea of physical intimacy with men, regardless of what he might actually want deep down.

So yeah that’s basically how I feel about Guts and Casca’s relationship, strong agree with you.

When it comes to Miura’s intent, I can tell you that Miura was asked about the subtext in an interview once, back in 2000, and he responded with something along the lines of ‘two men can have passionate feelings for each other without it being romantic.’ The interview is here, but this is a paraphrase the translator mentioned in the comments.

Other than that I’ve never seen him address it directly, but on the flipside he has cited several textually gay stories as inspiration (off the top of my head: Kaze to Ki no Uta, Devilman, Guin Saga, mangaka Moto Hagio in general), and he has straightforwardly said that the (magical intersex) central character of his other work, Duranki, was intended to have romances with both male and female love interests. Also people tell me there are strong griffguts vibes with the main, presumably canon or intended-to-be-canon ship there. So there’s that lol.

As for the no homo aspect and the potential homophobia in the griffguts subtext... I can’t deny I’ve also considered the idea that it’s a deliberate anti-gay PSA (though I haven’t seen anyone else address the idea as far as I remember, and I’ve only briefly mentioned it offhandedly). Like, Guts and Griffith’s relationship turns bad because they’re both too invested in each other, maybe the barely-subtextual desire is meant to look like a sinister twisting of pure platonic feelings that ruins everything, if Griffith hadn’t loved him the Eclipse never would have happened, etc.

But honestly I don’t think that reading holds up compared to a much more positive reading of their feelings, in which it’s their failure to understand them and act on them, thanks largely to formative childhood trauma and self-hatred, that leads to tragedy.

I don’t know what Miura intended, and there certainly are aspects of the story that are homophobic regardless of his intent, even if my best-faith reading is entirely correct, like the only textual gay attraction being pedophiles and over the top heretic orgies lol, or yk, Guts and Griffith both assaulting the same woman while looking at/thinking about the other in a very sexually charged way.

But the reading of their relationship where it’s positive and good for both of them, even including sexual desire, and only gets fucked up because they both incorrectly think their feelings are unrequited is legitimately so weirdly strong, much stronger than a reading where the sexual nature of their feelings is what fucks everything up, so I’m pretty happy just rolling with that take.

And as much as Casca can be seen and may very well be intended as a no homo, it’s also very easy for me to read her relationships with both as less of a hopeful opportunity for positive heterosexual romance and more of a “here’s how repressing your feelings thru attempts at heterosexuality fucks you up” PSA lol. Griffith and Charlotte too, for that matter. It’s definitely a stretch to think that’s intended, but whether it’s intended or not it’s an easy sell for me and I’m fine with not really worrying too much about possible authorial intent there.

Finally, I also want to link this post that goes pretty thoroughly into why I interpret griffguts as very positive rather than as a cautionary tale or predatory gay lust etc

And also have this shorter post about Femto on the same subject too, why not

Oh and maybe this thing where I split hairs about Guts’ lust for Griffith and desire for revenge to make a point that the homoeroticism isn’t necessarily being equated with violence by the narrative lol

#ask#a#b#anonymous#theme: repression#theme: homoeroticism#interviews#ship: griffguts#ship: gtsca#theme: homophobia#theme: heteronormativity

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey @give-zuko-peace-and-tea, i noticed your tags on my post and i would like to respond to some of them, because while i believe you were well intentioned, there were some points that i wanted to clarify.

#this person is right #but narratively i think trans zuko makes more sense than trans sokka because sokka's character arc is about masculinity #and idk i just think if you make him trans it changes the nature of why he feels so bound by his gender roles

why does sokka (or zuko, for that matter) being trans Have to fit within the narrative? sure, him being trans would affect the Perspective from which he’s coming from, but that shouldn’t nor is the entire narrative focus. him Being trans wouldn’t detract nor change that significantly. disregarding the fact that the southern water tribe, while more traditional, isn’t even half as sexist as the northern water tribe (disregarding the fact that bryke making either of the water tribes sexist in any sort of way is. fucked up). furthermore, it’s interesting how sokka, being More Traditionally Manly, seems to translate to “trans headcanons don’t really apply to him” through the justification of “him being trans doesn’t serve his role in the narrative as well as him being a cis man does”. which is funny, because the entire point of my post was specifically that these sorts of things (being hc’ed as gay, trans, autistic, or all three) happen to No One Other Than Zuko.

#the root of why sokka needs to feel like a Man is because he thinks that is the only way to have honor #so if hes trans it becomes a story of oppression and restriction from his community

i have to disagree with you here. while sokka does have his own deal with honor going on, his emphasis on being a man is moreso tied with the concept of being a leader, which is what his dad was and left him alone to do when they went off to fight in the war. his whole thing is not fitting into those big shoes he Knows he has to fulfill eventually, as the son of the chief of the southern water tribe. there are quite a few sokka centric episodes that show his core beliefs and wants (such as jet, bato of the water tribe, the library, sokka’s master, just to name a few) which are much more war and leadership-oriented, rather than gender, even if him being a man has a role to play. and if he was canonically trans, i do have to ask- why Must his story become one of oppression and restriction? why is that the only other alternative? is it because the narrative doesn’t serve him being trans? or is it the other way around? why does either have to exist or happen? why does there have to be justification for one or the other?

trans people just... exist. they don’t have to have a reason to. again- their gender and transition influences their perspective. if atla was an lgbtq+ story Intended to be viewed through an lgbtq+ lens, it’d be different, because then his gender serving the narrative would Actually serve the narrative, with his transness being brought to light and maybe focus. but it’s not. sokka is a guy with feminine attributes. you could say that for any character. the problem lies in Only giving somewhat feminine characters the gay or trans narrative, because then, it shows that you are moreso relying on stereotypes, rather than just letting these characters exist as they are. this also plays into another thing- where are all of the trans women headcanons? where are all the trans women headcanons for women who Aren’t somewhat androgynous or masculine? do either of the previous things i said immediately equate them as “just right” for being trans coded?

#also I agree that zuko is the more traditionally manly of the two and he is very feminized in fanon and is the lightest skinned main boy #seeing the light skinned richer character as feminine and the dark skinned as butcher is messed up

yes. the point of my post was that racism, fetishization, infantilization and stereotyping of zuko and Zuko Only leads to the butchered fanon interpretation we see today. but the point of my post Wasn’t that zuko Can’t be feminine, even if i think he doesn’t really struggle with the concept of being perceived as feminine in the exact same breadth nor capacity as sokka. i don’t particularly enjoy how the headcanoning of characters as trans (which wasn’t even in the original post, mind you- it was in the tags) took precedence over my intended, previously stated points. however, by you mentioning it to this degree, it brings up another problem- the concept of trans people Having to serve the narrative in order to exist as trans people, as well as the gearing of lgbtq+ storylines towards oppression and suffering. these are things that a cis writer writing for a cis audience often do. and again, atla is in no way an lgbtq+ story. there was no authorial intent for such characters within the story, no matter how coded they are, so the narrative service argument and their identities “fitting better” is hard to apply to begin with.

we see multiple characters struggle with their identity over the course of the series- aang is the last airbender, katara is the last waterbender of the southern water tribe, sokka is the son of the chieftain and the only man left in charge, toph is a blind rich kid who isn’t taken seriously because she is blind, and zuko is the prince of the imperialist fire nation who has to come to terms with the atrocities his people committed all while establishing his own identity as someone separate from his father.

any of them being trans would serve the perspective of those individual journeys, but narratively, this is what their journeys would be geared towards.

but that wasn’t my point.

#also i should add#i talked a lot about authorial intent but i mean it in the sense of. that’s not gonna stop people from headcanoning whoever they want as#trans#and i know you did say these sorts of hcs are valid for characters but. still. i understand where you were coming from but.#it's still not really cool?#and if you're cis why are you determining the validity of transness to a blog run by a trans guy?#why does a trans person have to be interesting to exist.#zuko#atla zuko#zuko atla#sokka#atla sokka#sokka atla#atla#avatar the last airbender#atla crit#atla meta#fandom crit#original#response

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello again! Im the tinfoil hat anon with the long ass asks and I finally had the time to read your response. Thank you, it makes my day reading your answers. I honestly just enjoyed them over a cup of coffee like a good book.

Now, the gun pointing scene I mentioned was in fact the one from the droid fight facility like the other anon suggested. But I really liked that you covered the boat scene too, I haven’t thought of it much myself and now I definitely have!

I also would like to mention I love your “candy bar” choice analogy and I 100% agree Hunter’s “invitation” to join back wasn’t welcoming in the slightest. It is very likely just an obligation as you said. Sort of “you gave us a chance, we owe you a chance too”.

And the problem with it is now I am struggling to figure out how the batch members might change their attitude toward Crosshair going forward, especially Hunter. As of right now Crosshair’s best relationship is not with his brothers but with Omega(as surprising as this is). And I think he does realize now she cared about him the most out of all of them during the short time they interacted(both 1st and last episodes). Even between themselves(not counting Omega) I find most of the bad batch members to be cold and distant to each other. They feel less like a family than Rebels for example. And they aren’t even a “found family”(a trope everyone loves) but an actual one! And I get that they’re soldiers and supposed to be tough, I don’t expect them to share all “the feels”. I just can’t put my finger on it but something feels off. I agree with your previous post, the show doesn’t do a very good job showing or even telling they love each other.

Will Hunter and co only start caring about their brother again only after he leaves the empire?(assuming he does at some point). What about Disney’s prevailing theme and message that “family always love and care for each other no matter what”? I guess it’s “family always love and care for each other but only if you’re good guys making right choices”. There is no room for mistakes or wrong decisions. In the last episode everyone form the batch seemed to have given up on Crosshair(besides Omega). For now their attitude seems to be just “you’re not our enemy” and that’s that.

I realize Crosshair is a “bad guy” and consciously made his choice(and we know it’s the wrong one) but to me it felt like he thought he didn’t even had a choice or rather became so lost and confused he actually thought he chose the empire as “the lesser evil”(as in the less shitty choice out of all the other bad ones). We as audience have the benefit to know exactly how atrocious the empire really is but maybe Crosshair still doesn’t realize that.

So what exactly must Crosshair do to get back “in their good graces” as you say? Start saving “the good guys”? Save the bad batch multiple times? There is a popular opinion on how Crosshair can redeem himself. That he eventually heroically sacrifices himself to save them. I personally REALLY hope it’s NOT what’s going to happen but I heard so many people speculating his story is set up to be redemption=death. I know you mentioned you don’t want “Vader style redemption” either. Personally I think it would be a waste of a character who has a lot of potential. And I just think that the batch kind of don’t really deserve his sacrifice(maybe save for Omega) after how they never tried to save him themselves and how they treated him overall. Maybe he will risk his life to save Omega at some point and that will “prove” to Hunter he cares? Although he has already shown he cares by saving her(even if in Crosshair’s own words it’s just so they’re “even”). And the thing is, he doesn’t need to prove that he loves them, he already did that in episode 15 and made it clear he does care. He actually went to extreme by shooting his squad to prove his loyalty. What were the moments the batch demonstrated they care about him? Hunter saying “you never were our enemy” and taking his unconscious body to safety? To me Hunter “not leaving him behind” during bombardment felt more like guilt about the last time it happened and an obligation to Crosshair for helping them with droids, rather than them showing care. And I kinda of think if that was any random civilian(or anyone other than an enemy or a threat) they would carry them out too just because that’s what good guys do and not because it’s their brother. You also mentioned that minutes later Hunter snaps at him with “if you want to stay here and die, that’s your choice” which I agree can be interpreted in different ways. And I think it’s one more point to it being an obligation that in Hunter’s eyes is fulfilled now. He corrected his mistake of leaving a brother behind and saved him this time, now his guilt won’t burden him any longer.

Anyway, I can’t wait for season 2 and I appreciate you and all the anons sharing the tinfoil hat, interacting and speculating together. Those discussions have been a lot of fun!

TLDR: How do your think the relationship between the brothers will mend or evolve in the next season? Do you think S2 will improve in portraying the batch more as a family rather than a group of mercs doing missions together? What are your thoughts on the popular idea of Crosshair’s redemption by ultimate sacrifice? As in, how likely do you think this scenario is?

Anon, that is just wonderfully hilarious to me. Ah yes, the sunrise, a good cup o' joe, and the overly long character analysis of a snarky, fictional sniper. Exactly what everyone needs in the morning! 😆

You know, TBB is far from the first show I've watched where there's an obvious, emotional conclusion the creator wants the audience to come to—the squad all love each other Very Much—yet that conclusion isn't always well supported by the text. It creates this horribly awkward situation where you're going, "Yes, I'm fully aware of what the show wanted to do, but this reading, arguably, did not end up in the story itself. So what are we talking about here? The intention, or the execution?" It's like Schrödinger's Bad Batch where the group is simultaneously Very Loving and Very Distant depending on how much meta-aspects are influencing your reading: those authorial intentions, understanding of how found family tropes should work, fluff focused fics/fan art that color our understanding of the characters, etc. And, of course, whether someone saw TCW before they watched TBB. I personally wouldn't go quite so far as to say they're "cold" towards one another—with Crosshair as an exception now—but there wasn't the level of bonding among the squad that I expected of a show called The Bad Batch. Especially compared to their arc in TCW. The other night I re-watched the season seven premiere and was struck not just by how much more the squad interacted with each other back then, but how those interactions added depth to their characters too. For example, Crosshair is the mean one, right? He's the one picking fights with the Regs? Well yeah... but it's also Wrecker. While they're trying to decide what to do with Cody injured, Jesse calls out Crosshair on his attitude—"You can't talk to Captain Rex like that!"—and Wrecker's immediate response is, "Says who?" and he hefts Jesse into the air. And then he just holds him there, clearly using his superior strength to do as he pleases, until Hunter (sounding pretty angry) tells him to put Jesse down. If Wrecker had put him into a more classically understood bullying position, like pinning him to the ground, it would probably read as less funny—less "Haha strong clone lifts Jesse up in the air!" and more "Oh shit, strong clone can do whatever the hell he wants to the Regs and few are able to stop him." It's such a quick moment, but it tells us a ton about Wrecker. That he's going to stick up for his brothers, no matter the context (Crosshair deserves to be called out). That he will gleefully assist Crosshair in bothering the Regs (something that is reinforced when he later throws the trays in the mess hall, after Hunter has already deescalated the situation). That he's likely been hurt by awful treatment from the Regs too. That he'll only listen to Hunter when it comes to backing off. Little of this work—that interplay among the squad that shows us new sides to them other than basic things like "Wrecker is the nice, happy brother"—exists in TBB.

Or, at least, little exists after Omega becomes an official member of the squad.

Because, as said previously, she becomes the focus. I don't mean that as a total criticism. As established, I love Omega. But if we're talking about why the squad can feel so distant from each other, I think she's the root cause, simply because the story became all about her relationships with the Batch, rather than the Batch's relationships with each other. Having dived headfirst into reading and writing fic, it occurred to me just how many of the bonding moments we love, the sort of stuff we'll see repeated in fics because we understand that this is where the story's emotional center is, are given to Omega in canon:

Someone is hurt and in need of comfort. Omega's emotional state is the focus + moments like her being worried over Hunter getting shot.

Someone needs to learn a new skill. Echo teaches Omega how to use her bow.

Someone reveals a skill they never knew they had before. Omega is a strategic genius and plays her last game with Hunter.

Someone is in serious danger and in need of rescue. Omega rescues the group from the slavers + is the most vocal about rescuing Hunter. (Which, again, is a pretty sharp contrast to the whole Crosshair situation.) Omega, in turn, needs rescuing from things like the decommission conveyor belt.

Similarly, someone is kidnapped and in need of rescue. Omega is kidnapped twice by bounty hunters and the Batch goes after her.

Someone saves another's life. Omega saves Crosshair from drowning.

Someone does something super sweet for another. Wrecker gives Omega her room. Omega gives Wrecker Lula.

A cute tradition is established between characters. Wrecker has his popcorn-esque candy sharing with Omega.

Someone hurts someone else and has to ask forgiveness. Wrecker is upset about nearly shooting Omega and they have that sweet moment together.

Note that most of these examples could have occurred between other Batch members, but didn't. Someone could have created a space for Echo on the ship too. Wrecker also could have apologized to Tech for choking him, etc. It's not that those moments shouldn't happen with Omega, just that there should be more of a balance across the whole season, especially for a show supposedly focused on the original squad. Additionally, it's not that cute bonding moments between the rest of the Batch don't exist. I love Hunter selling Echo off as a droid. I love Wrecker and Tech bickering while fixing the ship. I love the tug-of-war to save Wrecker from the sea monster. Yes, we do have moments... it's just that comparatively it feels pretty skewed in Omega's direction.

So, as a VERY long-winded way of answering your question, I think we need to fix the above in order to tackle Crosshair's redemption in season two. Now that we've had a full season focused on Omega, we need to strike a better balance among the rest of the squad moving forward. We need to re-established the "obvious" conclusion that the rest of the Batch loves Crosshair and that's done (in part) by establishing their love for one another too. To my mind, both goals go hand-in-hand, especially since you can develop their relationship with Crosshair and their relationships with each other simultaneously. Imagine if instead of just having Wrecker somewhat comically admit that he misses Crosshair (like he's dead and they can't go get him??), he and Tech had a serious conversation about why they can't get him back yet, despite very much wanting to. Imagine if Echo, the one who was rescued against all odds, got to scream at Hunter to go get Crosshair like Omega screamed at them to go back for Hunter. Imagine if we'd gotten more than a tiny arc in TCW to establish the Batch's dynamic with each other, providing a foundation for how they would each react to Crosshair's absence. Instead, what little we've got in TBB about Crosshair's relationship with his brothers is filtered through Omega: Omega's embarrassment that she knocked over Crosshair's case, Omega treating Crosshair's comm link like a toy, Omega's quest to save Hunter that just happened to involve Crosshair along the way.

Obviously, at this point we can't fix how the first season did things, but I think we can start patching over these issues in season two. It would be jarring—we'd still be 100% correct to ask where this "Brothers love you, support you, and will endlessly fight for you" theme was for Crosshair's entire time under the Empire's thumb... but I'd take an about-face into something better than not getting any improvement at all. It is frustrating though, especially for a show that I otherwise really, really enjoyed. For me, the issue isn't so much that the show made a mistake (since no show is perfect), but that the mistake is attached to such a foundational part of the franchise. Not just in terms of "SW is about hope and forgiveness" but the specific relationship most clones have with each other: a willingness to go above and beyond for their brothers. The focus on Omega aside, it's hard to believe in the family dynamic when one member of the family was so quickly and easily dismissed. I couldn't get invested in Hunter's rescue as much as I should have because rather than going, "Yes!! Save your brother!!!" my brain just kept going, "Lol where was this energy for Crosshair?" It messes with your reading of the whole story, so in order to fix that mistake going forward, we need to start seeing the bonds that only sometimes exist in season one. Show the guys expressing love for one another more consistently (in whatever way that might be—as you say, soldiers don't have to be all touchy-feely. Give us more moments like Wrecker supporting his brothers' bad habits) and then extend that to Crosshair. Which brother is going to demand that they fight for him? Which brother is going to acknowledge that they never tried to save him? Which brother is going to question this iffy statement about the chip? In order to buy into the family theme, Omega can't be the only one doing that emotional work.

Ideally, I wouldn't want Crosshair to go out of his way to prove that he's a good guy now. I mean, I obviously want him to stop helping the Empire and such, duh lol, but I'm personally not looking for a bunch of Extra Good Things directed at the Batch as a requirement for forgiveness. Simply because that would reinforce the idea that they're 100% Crosshair's victims, Crosshair is 100% the bad guy, and he's the only one who needs to do any work to fix this situation. Crosshair needs to stop doing bad things (working for Empire). But the Batch needs to start doing good things too (reaching out to him). Especially since Crosshair made a good play already, only to be met with glares and distrust. He saved Omega! And AZI! And none of them cared. So am I (is Crosshair) supposed to believe that saving one of their lives again will result in a different reaction? That doesn't make much sense. And no, his own life wasn't at risk when he did that, but does every antagonist need to die/nearly die to prove they're worth fighting for? As you say, he's already shown that he loves them, far more than they've shown the reverse. Every time Crosshair hurt them (attacking) it was while he was under the chip's influence. In contrast, the group has no "I was being controlled" excuse for when they hurt him (abandonment). Season two needs to acknowledge the Batch's responsibility in all this—and acknowledge that they're all victims of the Empire—in order to figure out an appropriate arc for Crosshair's redemption.

Right now, the issue is not Crosshair loving his brothers, the issue is how Crosshair chooses to express that love: trying to keep them safe and giving them a purpose in life by joining the organization that's clearly going to dominate the galaxy. The only way to fix that, now that his offer has been rejected, is for him to realize that a life on the run from the Empire, together, is a better option for everyone. And the only way for that to happen is for the Batch to seriously offer him a place with them again. They need to make the first move here. They need to fight for him. And yeah, I totally get that a lot of people don't like that because it's not "fair." He's the bad guy. He's with the fascist allegory. He's killed people and has therefore lost any right to compassion and effort from the good guys... but if that's the case, then we just have to accept that (within the story-world, not from a writing perspective) Crosshair is unlikely to ever come back from this. When people reach that kind of low, they rarely pull themselves out on their own. They need other people to help them do that. Help them a lot. But with the exception of Omega's reminder—which Crosshair can't believe due to how everyone else has treated him—they leave him alone and seem to expect him to fix himself first, then he gets their support. It needs to be the other way around. Support is what would allow him to become a good guy again, not "Well, you'll get our love when you're good again, not before." That's unlikely to occur and, as discussed, it doesn't take into account things like this bad guy life being forced on Crosshair at the start. If the story really wanted this to be a matter of ideological differences... then make it about ideological differences. Let Crosshair leave of his own free will, right at the start. Don't enslave him for half the season, have him realize he was abandoned, imply all that brainwashing, give him no realistic way out, and then punish him for not doing the right thing. This isn't a situation where someone went bad for the hell of it—the story isn't asking us to feel compassion for, say, the Admiral—it's a situation where Crosshair was controlled and now can't see a way out. That context allows for the Batch, the good guys, to fight for him without the audience thinking the show is just excusing that behavior. They should have been fighting from the start, but since they didn't, I hope we at least start seeing that in season two.

Ultimately though... I don't really expect all of the above. The more balanced dynamics and having the Batch fight for Crosshair rather than Crosshair going it alone... I wouldn't want to bet any money on us getting it, just because these are things that should have been established in season one and would have been more easy to pull off in season one. (If the Batch wouldn't fight for Crosshair while he was literally under the Empire's control, why would they fight now when he's supposedly acting of his own free will? It's backwards in terms of the emotional effort involved.) But again, it could happen! I'd be very pleased if it did happen, despite the jarring change. I don't want to make it sound like I think they're going to write off Crosshair entirely. Far from it, I think there are too many details like his sad looks for that, to say nothing of Omega's compassion. But the execution of getting him on Team Good Guys again might be preeeetty bumpy. I expect it to revolve around Crosshair's sins and Crosshair's redemption, even if what I would like is balancing that with Crosshair's loss of agency, the Batch's mistakes, and their own redemption towards him.

Honestly though, I just hope that whatever happens happens soon. It's a personal preference, absolutely, but after a season of Crosshair as the antagonist, I'm ready for him to be back with the group, making the Empire (and bounty hunters) the primary enemy. Whether his return happens through a mutual acknowledgement of mistakes, or through Crosshair being depicted as the only one in the wrong who has to do something big to be forgiven... just get him back with the squad lol. Because if the writing isn't going to delve into that nuance, then the longer he remains unforgiven, the longer some of us have to watch a series while going, "Wait, wait, wait, I really don't agree with how you're painting this picture."

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello I am the Tsumugi love hotel anon Thank you for answering my ask it's great to know that other people have the same problem Sorry if this sounds strange but it's hard for me to enjoy V3 without thinking about this I love Danganronpa and I like Tsumugi but this really really bothered me And I kinda don't want to assume that someone who created a series I like so much is like this I guess as a fan Do you have any advice? So sorry but I have this habit of overthinking things and just want help

Hi again anon! It’s not a strange question at all; this is sadly kind of a common dilemma to run into in most fandom spaces, and it’s perfectly normal to have conflicting feelings about these things.

The best advice I can give is to view everything through a critical lens. By this, I don’t mean “you can’t ever enjoy things casually” or “you have to hate the media you consume in order to be a Good Fan™.” I simply mean that it’s important to be aware that pretty much all media is going to be flawed on some level, and that it’s important to not brush aside those flaws when having a real discussion about the content we enjoy and consume.

Part of the reason why I love meta and analysis so much is precisely because it’s a really good way to sort through some of these more complicated feelings I have on certain topics. For as much as I love DR and as much as it’s been a huge source of enjoyment and comfort to me for quite a few years now, I’m never going to sit here and act like it doesn’t have its fair share of flaws. It’s certainly not for everyone, and I can completely understand why some people may not like it.

There’s a very fine line when discussing media too, between raising awareness that all media and content we consume is inherently flawed in some way, and simply dismissing it as okay because “well, everything is problematic in some way so it doesn’t matter.” These things do matter, and I feel like discussion of them is a very important part of critical analysis, especially when it raises awareness of potentially upsetting subject matter to people who may have been unaware of it before.

The entire love hotel scene with Tsumugi is undeniably in extremely poor taste, particularly when incest is a very real and terrible form of abuse that real survivors have suffered through. Seeing it used for nothing more than skeevy fanservice to pander to an otaku audience is deeply upsetting, particularly coming from a game that explicitly touches on the ways in which fiction can and does impact reality in very real, tangible ways.

It doesn’t help that the love hotel scenes themselves hang in a weird sort of limbo as far as their role in the game goes, either. There’s been a lot of debate in the fandom as to whether these scenes can even be considered “canon” on any level—and even if they’re not technically canon, which I think is a fair assessment given that none of the other characters even remember them after waking up and they have no real lasting impact on the plot, the decision to include them at all is still gross on some level.

In my personal opinion, the best way to determine how comfortable you are continuing to support a series or not, is to try and gauge authorial intent: why are these topics or themes included in this piece of media? What purpose do they serve? Are they contributing to a larger narrative by being included here?

To take a topical example… let’s compare this with Harry Potter. DR certainly has its flaws, and ndrv3 is no exception. Not only are certain unsavory “tropes” like incest played as either a punchline or a tool for fanservice, but even earlier parts of the series don’t hold up particularly well (like Chihiro’s “gender reveal”). These things are definitely not enjoyable parts of the narrative—but their presence in the narrative seems to stem from a larger issue of fanservice tropes in visual novels and anime overall, rather than some overarching attempt to either demonize any marginalized group or normalize harmful behavior in real life.

By contrast, through watching JK Rowling’s downward spiral on twitter in the last few years, we’ve seen her become more and more brazen about her hatred of trans people, and trans women in particular. Though she often attempted to brush these tweets aside at first as “middle-aged moments” or “accidents” where she wasn’t aware of the content being spouted by the people she was following, she’s become perhaps one of the most unapologetic T*RFs in the public consciousness.

No matter how much a series like Harry Potter may have shaped my and many other people’s childhoods in the past, it’s really impossible for me to go back to it nowadays as a trans individual. Re-reading the series with a much more critical eye shows that many of Rowling’s most harmful, offensive beliefs are not only something she spews on twitter every other month, but also downright woven into the narrative. Lines about “boys pretending to be girls to try and sneak into the dormitories” and Rita Skeeter’s “rather large, mannish hands” while she “disguises herself” to infiltrate the school premises just hit differently, knowing Rowling’s stance on trans issues and the disgusting harm that she advocates for with her huge platform.

I suppose that’s the biggest line I try to be aware of in deciding where I draw the line between enjoying a series while remaining critical of it, and just flat out refusing to support said series anymore. This line is understandably going to be different for different people, no doubt—but I think being mindful of what creators are actually doing with their platforms is the biggest indicator about the potential intentions behind their works.

The only other piece of advice I can think of to offer, and perhaps the most important one, is to simply support small creators with all the enthusiasm and love that you would for a large series. As long as we maintain a critical eye and awareness about the flaws within popular works like Danganronpa, I think it’s okay to keep enjoying said works. But there are so many content creators out there trying to contribute all kinds of meaningful works with better representation than anything we’ve seen in mainstream media, and it’s incredibly important to support these people so that their works can become better-known.

My best recommendation is to make sure you’re striving to support these smaller content creators: especially black artists and trans artists, who often get overlooked even when hashtags on twitter to support smaller artists are trending.

This sort of became a lengthier response than I was intending, but I felt your question deserved more of an in-depth look at the topic. I hope I was able to get my points across! Thank you for the question anon, and I really hope I could help.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Billboard #1s 1969

Under the cut.

Tommy James And The Shondells – “Crimson And Clover” -- February 1, 1969

There are barely any lyrics to this thing, and they don't make any sense. Why crimson and clover over and over? And over and over and over and someone make it stop. Also it's musically attempting to be interesting and failing miserably for me. This song is apparently a critical darling these days. I don't get it. It bores and irritates me.

Sly & The Family Stone – “Everyday People” -- February 15, 1969

A funk song about how people are bad at accepting outward differences, and that we should stop with that nonsense. With a line about "For bein' such a rich one that will not help the poor one" as well. It's got a lot of oomph and musical interest, and it's a sentiment that people will probably always need to hear. Great song.

Tommy Roe – “Dizzy” -- March 15, 1969

The music of this song, with the constant key changes, does make me feel dizzy. They lyrics are the normal stuff about wanting a girl ever since the narrator saw her, except for this line: "I want you for my sweet pet." Um, what? That's off even for the day. Not something I like.

The 5th Dimension – “Aquarius/Let The Sunshine In” -- April 12, 1969

Was this song taken seriously at the time? The tune is a good Broadway show-stopper, but the lyrics are just... seriously? "Mystic crystal liberation." And the "let the sunshine in" part is unbearably repetitive.

The Beatles – “Get Back” (Feat. Billy Preston) -- May 24, 1969

Billy Preston injected some needed inspiration back into The Beatles. The lyrics are pretty much nonsense. It's an okay Beatles song but with a great bassline.

Henry Mancini – “Love Theme From Romeo And Juliet“ -- June 28, 1969

We watched Franco Zeffirelli’s version of Romeo And Juliet in high school, with one caveat: The geometry teacher/boys' swim team coach had recorded a sunset over the football field over the part of the balcony love scene where they get all hot and heavy, apparently thinking it was just too much for 13 and 14 year olds. They left the sound though. Which made it way dirtier than it would have been with the images still there. So anything associated with that movie is hilarious to me. This is a Henry Mancini instrumental, which means it's good and I really shouldn't be cackling.

Zager & Evans – “In The Year 2525″ -- July 12, 1969

On a musical level, I hate this. It's a tidge too slow, it's a lot too bland, and something about the far future should sound futuristic, and this doesn't at all. Also the lyrics are dumb. It's not all of us who have fucked up the environment; it's the powerful. And I refuse to be morally scolded by someone who says in total seriousness, "In the year 4545/ You ain't gonna need your teeth, won't need your eyes/ You won't find a thing to chew." Dull and annoying.

The Rolling Stones – “Honky Tonk Women” -- August 23, 1969