#it was like they went out of their way to de-jewish the film

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Is It Really That Bad?

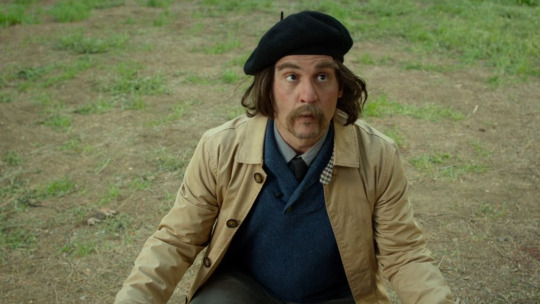

It’s hard to believe nowadays, but there was a time where the Tim Burton/Johnny Depp duo was known for delivering nothing but certified bangers. Edward Scissorhands, Ed Wood, Sleepy Hollow… It was just hit after hit when these two joined forces. But in the mid 2000s, something shifted. It suddenly seemed like people were sick of Burton, sick of Depp, and most of all sick of them working together. Sure, Corpse Bride and Sweeney Todd were still well-liked, but once Alice in Wonderland hit theaters people weren’t shy about voicing their dislike of the director and especially the actor. Burton kind of skidded to a halt for a while, while Depp just kept making increasingly worse movies with Disney and generally not doing anything worthwhile after Rango, and while Alice was the breaking point, the cracks started to show in 2005 with a little film called Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

An attempt to redo Roald Dahl’s novel about a precocious child touring the candy factory of a wacky candymaker was being planned for a long time, with even Nicolas Cage in talks at one point to be Wonka, and at another point good ol’ Martin Scorcese was attached to direct. But things just kept falling through until Burton got dragged in, and from there he proceeded to get things done and talk the studio out of stupid decisions like killing off Charlie’s dad and making Wonka a parental figure. Ah, but speaking of Wonka, that crucial role needed filling, and it seemed a lot of famous actors were considered for the role by the studio—Robin Williams, Patrick Stewart, Michael Keaton, Steve Martin, Bill Murray, Christopher Walken, Brad Pitt, Leslie Nielsen, Robert De Niro, Will Smith, Mike Meyers, Ben Stiller, pretty much every living member of Monty Python left at the time, Adam Sandler, and Marilyn Manson among them according to TVTropes—and Burton had an interesting idea for his second pick to play the guy:

But instead he went for his first pick, someone who’s actually very similar to Marilyn Manson in a lot of ways! Good ol’ reliable JD himself! Surely this was gonna bring in the big bucks! And... it did! It's the highest-grossing adaptation of one of Dahl's works ever, and Burton's second highest-grossing film!

Critics seemed mostly fine with it, but audiences were a lot more divided. Some people liked that it was a new and different take on the story that stayed a lot more true to the book than the beloved 1971 Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (a movie that Dahl famously hated as much as he did Jewish people, so frankly who gives a shit about his opinion), while others clung to the nostalgia of the Gene Wilder Wonka and treated this new film like a war crime. How dare they remake their favorite movie, even though this isn't a remake, it's just a different adaptation of the same book!

So yes, this movie isn’t the most reviled film out there, but it definitely is incredibly divisive, and what’s more I distinctly recall even as a child being aware of the attitude towards Depp and Burton shifting towards the more negative when this film came out. So I figured it was a high time I see about revisiting it and find out if this second cinematic outing into Wonka’s factory was really that bad, or if it genuinely was a work of impure imagination.

THE GOOD

It may surprise you to hear that this film actually does a few things better than the 1971 film. This is especially evident in the four shitty children touring the factory with Charlie.

The ones from Willy Wonka were, to put it bluntly, dull and forgettable, and came off as far too sympathetic in regards to their fate because none of them aside from Veruca Salt showcased any terrible traits that would lead to them deserving their punishments. In this film, all these kids are assholes, so watching them fall prey to the karmic justice of Wonka's factory is all the more satisfying. We also get to see what happens to them after they get out, which is kind of funny. I’m not gonna pretend that they made them the deepest and most complex characters ever, but with how they updated them and with the young actors they got to portray them, they managed to inject a bit more life into them than you’d expect.

This movie also fixes Grandpa Joe, who is pretty infamous to fans of the '71 film as a total asshole who constantly encourages Charlie to steal and just in general seems like a massive burden to his family. Here, he actually is every bit the sweet old grandpa that you’d expect, and his motivations for wanting to go on the tour are a lot nicer and more sympathetic. He also never tries to push Charlie into a life of crime, which is nice.

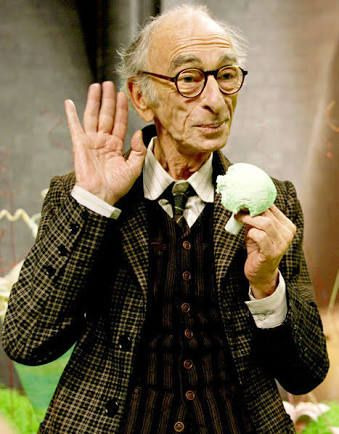

Of course, the very best aspect of this movie is Deep motherfucking Roy. He’s the second best dwarf actor out there, only oovershadowed by Warwick “Leprechaun” Davis, and much like Davis was in Star Wars as the ultimate Glup Shitto—Droopy McCool.

And in this film he gets the incredible honor of being every single fucking Oompa-Loompa there is, and he is clearly having a blast and busting his ass. He had no prior dancing experience, but you could not tell with how he’s pulling off all these sick moves while spitting out diss tracks for children like he’s Blood on the Dance Floor. He really is the single best actor in the movie, and that’s not to slander anyone else—Roy is just that good. Like we have a scene-stealing minor role for Christopher Lee as Wonka’s dad, a crabby dentist who hates candy, and as amazing as he is Roy still is better. You better respect this man.

Speaking of men to respect: Danny Elfman. Taking lyrics straight from the book and weaving a unique style for each kid—Big Bollywood spectacle for Augustus (that was Roy’s idea), 70s funk for Violet, psychedelic rock for Veruca, and hard rock for Mike—the songs are all genuinely great and fun to listen to. I’d never go as far as to say they’re more iconic than the Oompa-Loompa tracks from the ‘71 film, but I think they function better as songs, and the fact each of them has their own distinct style to set them apart from each other was the right way to go. I do think Mike’s song is the weakest of the bunch, feeling a lot messier than the other three, but it’s not unbearably awful or anything.

THE BAD

The biggest issue with the film is that the two most important characters—Charlie and Wonka—fucking suck.

Let’s start with Charlie. Now, to be clear, I’m not putting any blame on Freddie Highmore—he was literally a child, and even then I think he’s doing his damndest to make Charlie cute and whimsical. The issue here is definitely on the writers, who saw fit to stuff him full of all the syrupy sweet Tiny Tim-esque kind-hearted poor child cliches but forgot to impart a personality to go with them. Charlie is, to put it bluntly, a boring and generic nice guy, and one who ends up feeling like a living plot device to further Wonka’s character development, something that feels especially egregious when his name is literally in the title.

And now let’s talk about Wonka. Boy, is there a lot to unpack with this guy.

Literally everything about this take on Wonka is incredibly awkward and off-putting. The most infamous aspect of him is definitely the look; with his pale skin and dorky haircut he looked a lot like Michael Jackson, who at the time the film came out was going through a very serious scandal where he was accused of doing awful things to children in his big rich guy mansion… which is essentially the plot of this film when you think about it.

But that’s just an unfortunate coincidence! It’s an ugly look, sure, but a good performance could make it palatable, and this was Johnny Depp during his big post-Jack Sparrow renaissance working together with the guy who helped put him on the map. Surely he wouldn’t deliver an incredibly awkward, cringey, and insufferable performance that dials up all his acting quirks to annoying levels, right?

youtube

Here’s the thing: On paper, Depp’s Wonka is honestly not that different than Wilder’s. They’re both weird, quirky, reclusive confectioners with a not-so-hidden disdain for the kids touring their factory and snarky, condescending attitudes. What it all comes down to is the presentation, and to show you what I mean I’m going to use the most batshit comparison you’ve ever seen:

Burton’s Wonka is very similar to Zack Snyder’s Ozymandias.

“Now hold on, Michael,” I hear you exclaiming in utter bewilderment, “how are these two comparable? I know that both are fine with the wonton murder of children if it helps achieve their goals and that a lot of people are weirdly horny for them, but how is this a good comparison?” Well luckily I’m not trying to compare a mass-murdering anti-villain to a quirky chocolatier in terms of character, but in how the adaptation drops the ball with how they’re presented by removing the more warm and positive aspects of them. In Alan Moore’s comic, Adrian Veidt is essentially a relentlessly charming gigachad, an affable and approachable fellow who seems beneath suspicion because he exudes a traditionally heroic warmth. In the movie, however, Snyder chose to portray Veidt as a cold, distant twink who doesn’t seem particularly approachable at all (another case of Daddy Zaddy tragically missing Moore’s point).

This same "missing the point" issue plagues Wonka. Yes, Wilder’s take is just as much a smug asshole reveling in the comeuppance the children are receiving, but he also has a genuine warmth to him which is codified perfectly with him singing “Pure Imagination.” Sure, he’s perfectly willing to traumatize everyone with a demented boat ride shortly after, but Wilder’s performance and the presentation of his Wonks help sell him as a quirky genius who is more likable than insufferable, and you really understand how despite being kind of a dick he is also a beloved figure.

Depp’s Wonka fails as the character in the same basic ways that the movie version of Veidt does: He's a condescending, cold, openly rude, guy who is just genuinely unpleasant to be around despite the movie really trying hard to make him likable and relatable, to the point where unlike Wilder's take it's hard to grasp why this guy gets any respect from anyone. He’s like the proto-Rick Sanchez, except he’s not even particularly funny to make up for it. Maybe this take is more accurate to the book, but if it is it’s really just proof that taking liberties when adapting really is for the best.

And this failure is only compounded by the movie piling on a tragic backstory for Wonka. Yes, Christopher Lee is great, but there is genuinely no need to pile on a traumatic childhood and weird daddy issues to Willy Wonka. The character works best as this weird, trickster mentor figure who dishes out karma to the naughty kids and ultimately rewards the good egg of the bunch. Trying to bring a guy with a magical factory full of dwarfs who do choreographed diss tracks every time a kid falls into the incinerator down to earth and make him relatable is just a mind-boggling decision.

These are really the only two issues with the film that stand out as excessively bad, but… you see the problem, right? The titular character and the owner of the titular chocolate factory are both bad. One’s a living prop, the other is just an obnoxious asshat who is given unneeded character development that ends up falling flat, and while this would be easy to ignore if they were side characters it’s impossible to let slide since they are the main fucking characters. The whole film revolves around the two very worst things in it, and no matter how good the other stuff in the movie is these elements alone drag it down a lot.

IS IT REALLY THAT BAD?

Look, I’m not going to pretend like this is a great film. If it really is closer to Dahl’s book, all it managed to do is convince me to never read it and solidified my belief that being pragmatic when adapting books to screen is the way to go. It’s also really easy to see how the Burton-Depp fatigue came about, as this is some of the weakest work in both of their filmographies.

But I still feel like there’s plenty to like here. The songs, the bratty kids, Deep motherfucking Roy, it’s all genuinely good shit! There was never a chance it was going to be iconic as the Wilder film, but it’s disingenuous to write it off entirely when it does a lot good things (and a few things better than the '71 version). A lot of people are nostalgic for this one these days, as it's the one this generation grew up with, and honestly? I can't really blame them entirely. It's a decent enough movie, and I honestly think that score it has up there is pretty fair. It's certainly a mixed bag but when it actually succeeds at being charming it does it in its own unique way rather than trying to ape the beloved classic that came before it, and I do respect it for that.

And hey, if Johnny Depp's worst and most annoying movie role is in a movie I'd still say is okay, that's a good thing right? He couldn't possibly ever take a role more cringeworthy and annoying than Wonka in a film that's genuinely shitty, right?

Right?

RIGHT?!

#is it really that bad?#IIRTB#Charlie and the Chocolate Factory#Tim Burton#Johnny Depp#Willy Wonka#Roald Dahl#book adaptation#review#movie review#Youtube

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

On that Puss in Boots brainrot, so here’s a list nobody asked for that I can’t get out of my brain

Classical Music I think characters would appreciate for one reason or another, usually because of the story or impetus behind its writing or meaning, in an increasingly longer title

Disclosure: these are just my thoughts. Feel free to comment, reblog, add, discuss! I’m just some dude on the Internet talking about fictional characters, have fun with it!

Under a cut cuz it’s long and there’s a lot of video links

My goal was to explore the music a bit more, get into the reasoning behind its existence, and how that story might play into why I think these characters would appreciate to it. (Sometimes, though, it’s a bit more simple than that)

Gotta start with our favorite, fearless Hero

Puss

“Heroic” Polonaise in Ab, Frederic Chopin

youtube

You’ve probably heard this one before, as it’s one of Chopin’s most popular works. Some research, however, I found that Chopin apparently didn’t like attaching descriptive titles to his work - “Heroic” was added by the modern listeners and music historians. The piece was written during the revolutions of 1842, and Chopin’s love at the time, Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil - known by her pen name George Sand - wrote that the piece had the energy and passion needed for the French Revolution. It seems their correspondence was a part of why it gained the name “Heroic” later in life.

While initially I chose this piece because “haha heroic for the hero,” I found I had a “wait a minute” moment reading about how the name was added later on. If having a title and being perceived a certain way doesn’t describe this cat (at least, for most of the film), then I watched the movie wrong. But the energy and vigor with which it clearly gets performed with, the emotional weight it can carry for so many people, during a time of political upheaval…I think Puss would resonate with that, being a Robin Hood himself.

Death

I have to talk about my boyfriend my boyfriend next, of course, being the reason for Puss’ journey in the first place.

Piano Trio No 2 in e, Dmitri Shostakovich

youtube

(This is likely the most difficult piece to listen to and talk about, tonally and emotionally. It’s incredibly dark. I’ve linked the fourth movement, because it beautifully synthesizes all the themes and ideas from the previous three, but if you have the time and spoons to spare I highly recommend listening to the entire composition start to finish.)

I’ve actually mentioned this piece specifically in this context on my blog before, but now I can elaborate a bit more. Shostakovich was heavily scrutinized by Stalin’s regime, and his works and performances were subject to the whims of the government for most of his life and beyond. He often had to write as carefully as he could so as to appear to be aligned with those in power, but often would write using themes and motifs counter to what the government would have liked.

The Piano Trio No 2 in e was part dedicated to Shostakovich’s friend and mentor, Ivan Sollertinsky - who passed away during the writing of the piece -, and part dedicated to the Jewish prisoners of war during WWII. Apparently, Shostakovich heard they were made to dig their own graves, and then dance on them. The fourth movement I linked makes the most clear use of a Yiddish-sounding theme in the violin, and the tormented nature of the composition is undeniable. As a character who clearly values life, I feel Death would appreciate the dedications and thought behind the piece, but also enjoy how beautifully macabre it sounds.

Kitty

Kitty was difficult for me, to be honest. Trying to find something that captures her arc is tricky, as I don’t personally know of much music that discusses trust, both in general, and the way she experiences it. But I do think she has a lot of pride in herself as a strong individual, and has pride in her work, which is why I went with

Danzon No 2, Arturo Marquez

youtube

The Danzon is a partner dance that developed from the Habanera, and is an active musical form in Mexico today. Marquez’s Danzon No 2 takes this to the next level, in a high energy and blistering work that will leave you humming it for hours. This piece is important as a modern work, as its popularity brought about not only greater respect for Mexican composers, but caused people (read: Western classical musicians) to explore and perform more Hispanic literature, especially Marquez’s. This is also the only piece on this list by a living composer, premiered in 1994.

Being of Hispanic descent, I felt Kitty would find pride in her nation’s music and dances becoming popular across the world due to the popularity of this piece. We also know this cat likes to dance, and it’s incredibly difficult to resist when listening to it.

Perrito

Nimrod, from Enigma Variations, Edward Elgar

youtube

The Enigma Variations are small vignettes written for Elgar’s friends. The most recognizable and known of the Variations, Nimrod is an absolutely gorgeous piece of music. The title “Nimrod” is a play on words - the friend in question’s name was Jaeger; Jaeger means “Hunter” in German; Nimrod was a biblical hunter of fame.

Jaeger was not only a friend, but Elgar’s publisher. He would offer advice and helped Elgar rework sections of music here and there. Jaeger’s presence as a confidant is shown in the slow moving lines, reflecting on years of support. If Perrito doesn’t embody dedicated friendship, support, and love in this way, then again - I must have watched the movie wrong. He learns to sit and listen through his time with Puss and Kitty, and this movement almost forces you to take a moment and really sit, listen, and appreciate what you’re hearing.

Goldi

Symphony No 1 in c, Johannes Brahms

youtube

I literally cannot think of a better “just right” story in music history than this piece. Brahms was known for destroying his manuscripts of works and sketches he didn’t approve of - he famously ached and pained over writing his first symphony, despite having already solidified himself as a successful composer. He was afraid of the looming shadow of Beethoven, who he had already been compared to by audiences and critics. Some records say it took 14 - others upwards of 21 - years for him to finish this first symphony, and even still he trialed it before publishing.

It seems things ended “just right” for this piece, after all. It was received positively, and spurred him on to compose his second symphony in about a year after the first. Music historians have pointed to this as a shift in the romantic symphonic style. While comparisons to Beethoven were still made (Brahms apparently being frustrated by this - not because of them, but because he felt it was obvious), Brahms had carved his own path of symphonic writing.

Okay I’m done here that’s as far as I got

If you made it down to here, congratulations! This idea came about because, uh, I thought it’d be fun! It gave me a chance to research a bit, and it was fun to try and think of music these characters that I can’t stop rotating in my head would appreciate.

Music is so universal, you could probably find a reason in any piece to give it to anyone, but that’s also what makes it so great. I am by no means an authority, and if you read all this way, feel free to let me know what you think!

Thanks for your time.

#puss in boots the last wish#puss in boots#kitty softpaws#perrito#puss in boots death#Goldilocks#music#profblogson#death puss in boots

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brainwashing in Conflict: Palestine and Israel

By Isabel De Los Santos Ramirez

During the film screening of Israelism offered by Georgia Tech’s Muslim Student Association, a diverse set of emotions arose in me. Before coming into this, I was always up to date with news on social media and would say I was already well informed of the history and devastation that has been occurring from Jewish settlements in the land that Palestians call home. What I did not know, and honestly found extremely shocking, is the Israeli culture of raising Jewish children in a way that makes their entire personality about Israel. In a way that I would say even overshadows practicing Judaism. To the extreme that Jewish-American teenagers choose to go to a country they have most likely never been to in order to serve in the military as an attempt to express patriotism.

Relating to the filming aspects of the documentary, I enjoyed the way the film progressed and how everything was introduced and expanded upon. For example, the main characters telling their story of how they were raised and how they experienced the real world for themselves which lead to them growing out of the “brainwashing” inflicted upon them by older zionist leaders in their communities. I appreciate the different perspectives on the Palestine-Israel situation. I had no idea some Jewish communities took such extremities in beliefs and nationalism. Just from this, I learned that we are not who we are raised to be. Anyone can change their way of thinking, their way of loving, their way of respecting, their way of having hope, their way of being a human being. It might take a tap on the shoulder or getting hit by a garbage truck, but it is possible.

For example, Simone Zimmerman, one of the main characters in Israelism, went from being a conservative Zionist to an activists for Palestinian Liberation who founded IfNotNow, which is a “movement of American Jews organizing community to end U.S. support for Israel's apartheid system and demand equality, justice, and a thriving future for all Palestinians and Israelis”.

Since this watching experience, I have learned a lot more from class, the news on social media, books (Minor Detail), podcasts, and other short films. I can’t help but to feel anger and helplessness about not being able to do something that will have an immediate impact to make things better. I know liberation and peace take time and loss, but for what reason? I don’t think I will ever understand.

After the screening of Israelism I expanded my research by watching these videos:

youtube

youtube

0 notes

Text

Welp, just watched Red Sea Diving Resort. It was visually stunning, (Chris Evans, I’m looking at you,) but that was...the least Jewish movie about Jewish people helping other Jewish people I’ve ever seen.

I mean, they didn’t have to play it up, but nobody did Israeli accents? They’re all supposed to be Israeli and NOBODY did the accents?? They changed the real Ari Levinson’s story so Chris Evans could sound like a bro and like...why, dude? Get a dialect coach, you can afford one! There was no shabbat, no brachas, nobody spoke Hebrew for even a second, they out here eatin’ lobster and talkin’ like they’re from the Midwest.

And who was that chick?? Was that not the most Aryan looking woman they could’ve gotten to play Rachel? You’re telling me that there was not ONE Jewish actress who could’ve played her? Not that there aren’t blond Jewish girls, but that was NOT what the actual Rachel Reiter looked like. She had cute mid-east curls! Dark hair! She was full on Ashkenazi-adorbs, and they couldn’t even find a brunette or dye the actress’ hair? Boo-urns!

I literally could not tell that the story wasn’t about a bunch of Americans rather than Israelis, and that is reallllly fucking weird.

Also, for a movie about refugees, it would’ve been nice to have the refugees get more face-time, more lines, more something. A scene or two that shows us what it means to be Jewish in Ethiopia. A Rabbi leading a group in prayer in the Sudanese camps, something. The whole impetus for saving these particular refugees was shared culture and religion, bringing a lost tribe home to Israel... and there wasn’t one scene of brotherhood in that sense in the film. There’s footage of the real rescues over the credits that shows the rescuers and the refugees dancing the hora together and like...yeah. That’s what I wanted in the actual movie.

I just...I had such high hopes, man. Sigh.

#the red sea diving resort#stitch watches the cinema#it was like they went out of their way to de-jewish the film#there aren't a lot of movies where Jews get to be the heroes#I was just hoping for better representation I guess#jewish things#or not

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

If/when they make a Joe/Nicky prequel movie, what are some of the Dos and Don’ts for them, with regards to historical accuracy. Like, what do you think they should include, and what do you think they should avoid?

Oof. This is a GREAT question, and also designed to give me a chance to ramble on in a deeply, deeply self-indulgent fashion. That is now what will proceed to happen. Consider yourself warned. So if they were miraculously to be like “well that qqueenofhades person on tumblr seems like she knows what she’s talking about, let’s hire her to consult on this production!”, here are some of the things I would tell them.

First off, a question I have in fact asked my students when teaching the crusades in class is whether you could actually show the sack of Jerusalem on screen. Like... if you’re making a film about the First Crusade, what kind of choices are you going to make? What narrative viewpoint are you going to uphold throughout the story? Are you actually going to show a slaughter of Muslim and Jewish inhabitants that some chroniclers described as causing enough blood to reach up to the knees of horses? (Whether it actually did this is beside the point; the point is that the sack went far beyond the accepted conventions of warfare and struck everybody involved in it as particularly horrific.) Because when you’re making a film about the crusades, you are also making it by nature for a modern audience that has particular understandings of Christian/Muslim conflict, religious warfare and/or tolerance, the War on Terror, the modern clash over ISIS, Trump’s Muslim ban, and so forth. The list goes on and on. So you’re never making a straight, unbiased historical adaptation, even if you’re going off the text of primary sources. You’re still constructing it and presenting it in a deliberate and curated fashion, and you can bet that whichever way you come down, your audience will pick up on that.

Let’s take the most recent example of a high-profile crusades film: Kingdom of Heaven from 2005. I’ve written a book chapter on how the narrative choices of KoH, aside from its extensive fictionalization of its subject matter to start with, make it crystal clear that it is a film made by a well-meaning Western liberal filmmaker (Ridley Scott) four years after 9/11 and two years after the invasion of Iraq, when the sympathy from 9/11 was wearing off and everyone saw America/Great Britain and the Bush/Blair coalition overreaching itself in yet another arrogant imperial adventure into the Middle East. Depending on how old you are, you may or may not remember the fact that Bush explicitly called the War on Terror a “crusade” at the start, and then was quickly forced to walk it back once it alarmed his European allies (yes, back then, as bad as America was, it still did have those) with its intellectual baggage. They KNEW exactly what images and tropes they were invoking. It is also partly why medieval crusade studies EXPLODED in popularity after 9/11. Everyone recognized that these two things had something to do with each other, or they made the connection somehow. So anyone watching KoH in 2005 wasn’t really watching a crusades film (it is set in the late 1180s and dramatizes the surrender of Jerusalem to Saladin) so much as a fictional film about the crusades made for an audience explicitly IN 2005. I have TONS to say on this subject (indeed, if you want a copy of my book chapter, DM me and I’ll be happy to send it.)

Ridley Scott basically sets it up as the Christian and Muslim secular leaders themselves aren’t evil, it’s all the religious fanatics (who are all made Templars, including Guy de Lusignan, going back to the “evil Templar” trope started by Sir Walter Scott and which we are all so very familiar with from Dan Brown and company). Orlando Bloom’s character shares a name (Balian de Ibelin) but very little else with the eponymous real-life crusader baron. One thing Scott did do very well was casting an actual and well-respected Syrian actor (Ghassan Massoud) to play Saladin and depicting him in essential fidelity to the historical figure’s reputed traits of justice, fairness, and mercy (there’s some article by a journalist who watched the film in Beirut with a Muslim audience and they LOVED the KoH Saladin). I do give him props for this, rather than making the Evil Muslim into the stock antagonist. However, Orlando Bloom’s Balian is redeemed from the religious extremist violence of the Templars (shorthand for all genuinely religious crusaders) by essentially being an atheistic/agnostic secular humanist who wants everyone to get along. As I said, this is a film about the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq made three years after 9/11 more than anything else, and you can really see that.

That said, enough about KoH, back to this presumable Joe/Nicky backstory. You would obviously run into the fact that it’s SUPER difficult to make a film about the crusades without offending SOMEBODY. The urge to paint in broad strokes and make it all about the evil Westerners invading is one route, but it would weaken the moral complexity of the story and would probably make it come off as pandering to guilty white liberal consciences. Are we gonna touch on the many decades of proto-crusading ventures in Iberia, Sicily, North Africa, and other places, and how the eleventh century, especially under Pope Gregory VII, made it even thinkable for a Christian to be a holy warrior in the first place? (It was NOT normal beforehand.) How are we going to avoid the “lololol all religion sucks and makes people do crazy things” axe to grind favoured by So Very Smart (tm) internet atheists? Yes, we have to demonstrate the ultimate horror of the crusade and the flawed premises it was based on, but we can’t do that by just showing the dirty, religiously zealot medieval people doing that because they don’t know any better and are being cynically manipulated in God’s Name. In other words (and the original TOG film did this very well) we can’t position ourselves to laugh at or mock the crusader characters or feel confident in looking down on them for being Dumb Zealots. They have to be relatable enough that we realize we could BE (and in fact already ARE) them, and THEN you slide into the horror and what compels them to do those kinds of things, and THAT’S when it hits. Because take a look at the news. This is happening around us right now.

Obviously, as I was doing in my First Crusade chapter in DVLA, a lot of this also has to spend time centering the Muslim point of view, the way they reacted to the crusade, the ways in which Yusuf as an Isma’ili Shia Muslim (Kaysani is the name of a branch of Isma’ili Shi’ites, he has a definite historical context and family lineage, and hence is almost surely, as I wrote him, a Fatimid from Egypt) is likewise not just A Stock Muslim. In this case, obviously: Get actual Muslims on the set to advise about the details. Don’t make stupid and/or obvious mistakes. Don’t necessarily make the Muslims less faithful or less virtuous than the Christians (even if this is supposed to praise them as being “less fanatic” than those bad religious Catholics). Don’t tokenize or trivialize their reaction to something as horrific as the sack of Jerusalem, and don’t just use dead brown bodies as graphic visual porn for cheap emotional points. Likewise, it goes without saying, and I don’t think they would anyway, but OH MY GOD DON’T MAKE THIS INTO GAME OF THRONES GRIMDARK!!!! OH MY GOD!!! THERE IS BEAUTY AND THERE IS LIGHT AND THERE IS POETRY AND THAT’S WHY IT HURTS SO MUCH WHEN IT’S DESTROYED! AND THE CHOICES THAT PEOPLE MAKE TO DESTROY THOSE THINGS HAVE TO BE TERRIFYINGLY PLAUSIBLE AND FAMILIAR, BECAUSE OH MY GOD!!

Next, re: Nicolo. Evidently he is a priest or a former priest or something of the sort in the graphic novel, which becomes a bit of a problem if we want him to actually FIGHT in the crusades for important and/or shallow and/or OTP purposes. (I don’t know if they address this somehow or Greg Rucka is not a medieval historian or whatever, but never mind.) It was a Major Thing that priests could not carry weapons, at least and especially bladed weapons. (In the Bayeux Tapestry, we have Odo, the bishop of Bayeux, fighting at the battle of Hastings with a truncheon because he’s a clergyman and can’t have a sword). They were super not supposed to shed blood, and a broadsword (such as the type that Nicky has and carries and is clearly very familiar with) is a knight’s weapon, not a clergyman’s. The thing about priests was that they were not supposed to get their hands dirty with physical warfare; they could (and often did) accompany crusade armies, bishops were secular overlords and important landholders, monks and hermits and other religious preachers were obviously part of a religious expedition, and yes, occasionally some priests would break the rules and fight in battle. But this was an exception FAR more than the rule. So if we’re going by accuracy, we have Nicky as a priest who doesn’t actively fight and doesn’t have a sword, we have him as a rule-breaking priest with a sword (which would have to be addressed, and the Templars, who were basically armed monks, weren’t founded until 1119 so he can’t be one of those yet if this is still 1099) or we just skip the priest part and have him as a crusader with a sword like any other soldier. If he was in fact a priest, he also wouldn’t be up to the same standard of sending into battle. Boys, especially younger sons of the nobility, often entered the church at relatively early ages (12 or 13), where it was treated as a career, and hence they stopped training in arms. So if Nicky is actually out there fighting and/or getting killed by Yusuf several times for Important Purposes, he’s... almost surely not a priest.

Iirc, they’ve already changed a few things from the graphic novel (I haven’t read it, but this is what I’ve heard) so they can also tweak things to make a new backstory or a hybrid-new backstory in film-verse. So once we’ve done all the above, we still have to decide how to handle the actual sack of Jerusalem and massacre of its inhabitants, the balance between violence comparable to the original TOG film and stopping short of being exploitative (which I think they would do well), and the aftermath of that and the founding of the new Latin Christian kingdom. It would have to, as again the original film does very well, avoid prioritizing the usual players and viewpoints in these events, and dig into presenting the experiences of the marginalized and way in which ordinary people are brought to the point of doing these things. It doesn’t (and frankly shouldn’t) preach at us that U.S. Invasions Of The Middle East Are Bad (especially since obviously none of the characters/people/places/events here are American at all). And as I said already but bears repeating: my god, don’t even THINK about making it GOT and marketing it as Gritty Dramatic Medieval History, You Know It’s Real Because They’re Dirty, Violent, and Bigoted!

Also, a couple tags I saw pop up were things like “Period-Typical Racism” and “Period-Typical Homophobia” and mmm okay obviously yes there are these elements, but what exactly is “period typical?” Does it mean “using these terms just because you figure everyone was less tolerant back then?” We know that I, with my endless pages of meta on medieval queer history, would definitely side-eye any attempts to paint these things as Worse Than Us, and the setting alone would convey a sense of the conflict without having to add on gratuitous microaggressions. I basically think the film needs to be made exactly like the original: centering the gay/queer perspectives of marginalized people and people of color, resisting the urge for crass jokes at the expense of the identity of its characters, and approaching it with an awareness of the deep complexity and personal meaning of these things to people in terms of the historical moment we’re in, while not making a film that ONLY prizes our response and our current crises. Because if we’re thinking about these historical genealogies, the least we can do (although we so often aren’t) is to be honest.

Thanks! I LOVED this question.

#history#medieval history#kingdom of heaven#joe x nicky#long post#persephone-rose-r#ask#the old guard meta

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mysterious Death of a Hollywood Director

This is the tale of a very famous Hollywood mogul and a not-so-famous movie director. In May of 1933 they embarked together on a hunting trip to Canada, but only one of them came back alive. It’s an unusual tale with an uncertain ending, and to the best of my knowledge it’s never been told before.

I. The Mogul

When we consider the factors that enabled the Hollywood studio system to work as well as it did during its peak years, circa 1920 to 1950, we begin with the moguls, those larger-than-life studio chieftains who were the true stars on their respective lots. They were tough, shrewd, vital, and hard working men. Most were Jewish, first- or second-generation immigrants from Europe or Russia; physically on the small side but nonetheless formidable and – no small thing – adaptable. Despite constant evolution in popular culture, technology, and political and economic conditions in their industry and the outside world, most of the moguls who made their way to the top during the silent era held onto their power and wielded it for decades. Their names are still familiar: Zukor, Goldwyn, Mayer, Jack Warner and his brothers, and a few more. And of course, Darryl F. Zanuck. In many ways Zanuck personified the common image of the Hollywood mogul. He was an energetic, cigar-chewing, polo mallet-swinging bantam of a man, largely self-educated, with a keen aptitude for screen storytelling and a well-honed sense of what the public wanted to see. Like Charlie Chaplin he was widely assumed to be Jewish, and also like Chaplin he was not, but in every other respect Zanuck was the very embodiment of the dynamic, supremely confident Hollywood showman.

In the mid-1920s he got a job as a screenwriter at Warner Brothers, at a time when that studio was still something of a podunk operation. The young man succeeded on a grand scale, and was head of production before he was 30 years old. Ironically, the classic Warners house style, i.e. clipped, topical, and earthy, often dark and sometimes grimly funny, as in such iconic films as The Public Enemy, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, and 42nd Street, was established not by Jack, Harry, Sam, or Albert Warner, but by Darryl Zanuck, who was the driving force behind those hits and many others from the crucial early talkie period. He played a key role in launching the gangster cycle and a new wave of sassy show biz musicals. At some point during 1932-33, however, Zanuck realized he would never rise above his status as Jack Warner’s right-hand man and run the studio, no matter how successful his projects proved to be, because of two insurmountable obstacles: 1) his name was not Warner, and 2) he was a Gentile. Therefore, in order to achieve complete autonomy, Zanuck concluded that he would have to start his own company.

In mid-April of 1933 he picked a public fight with Jack Warner over a staff salary issue, then abruptly resigned. Next, he turned his attention to setting up a company in partnership with veteran producer Joseph Schenck, who was able to raise sufficient funds to launch the new concern. And then, Zanuck invited several associates from Warner Brothers to accompany him on an extended hunting trip in Canada.

Going into the wilderness and killing wild game, a pastime many Americans still regard as a routine, unremarkable form of recreation, is also of course a conspicuous show of machismo. But in this realm, as with his legendary libido, Zanuck was in a class by himself. He had been an enthusiastic hunter most of his life, dating back to his boyhood in Nebraska. Once he became a big wheel at Warners in the late ’20s he took to organizing high-style duck-hunting expeditions: the young executive and his fellow sportsmen would travel to the appointed location in private railroad cars, staffed by uniformed servants. Heavy drinking on these occasions was not uncommon. (Inevitably, film buffs will recall The Ale & Quail Club from Preston Sturges’ classic comedy The Palm Beach Story, but DFZ and his pals were not cute old character actors, and their bullets were quite real.) Members of Zanuck’s studio entourage were given to understand that participation in these outings was de rigueur if they valued their positions, and expected desirable assignments in the future. Director Michael Curtiz, who had no fondness for hunting, remembered the trips with distaste, and recalled that on one occasion he was nearly shot by a casting director who had no idea how to properly handle a gun.

But ducks were just the beginning. In 1927 Zanuck took his wife Virginia on an African safari. In Kenya Darryl bagged a rhinoceros and posed for a photo with his wife, crouched beside the rhino’s carcass. Virginia, an erstwhile Mack Sennett bathing beauty and former leading lady to Buster Keaton, appears shaken. Her husband looks exhilarated. During this safari Zanuck also killed an elephant. He kept the animal’s four feet in his office on the Warners lot, and used them as ashtrays. If any animal lover dared to express dismay, the Hollywood sportsman would retort: “It was him or me, wasn’t it?” Zanuck made several forays to Canada with his coterie in this period, gunning for grizzly bears. Director William “Wild Bill” Wellman, who was more of an outdoorsman than Curtiz, once went along, but soon became irritated with Zanuck’s bullying. The two men got into a drunken fistfight the night before the hunting had even begun. In the course of the ensuing trip the hunting party was snowbound for three days; Zanuck sprained his ankle while trailing a grizzly; the horse carrying medical supplies vanished; and Wellman got food poisoning. “It was the damnedest trip I’ve ever seen,” the director said later, “but Zanuck loved it.”

Now that Zanuck had severed his ties with the Warner clan and was on the verge of a new professional adventure, a trip to Canada with a few trusted associates would be just the ticket. This time the destination would be a hunting ground on the banks of the Canoe River, a tributary of the Columbia River, 102 miles north of Revelstoke, British Columbia, a city about 400 miles east of Vancouver. There, in a remote scenic area far from any paved roads, telephones, or other niceties of modern life, the men could discuss Zanuck’s new production company and, presumably, their own potential roles in it. Present on the expedition were screenwriter Sam Engel, director Ray Enright, 42nd Street director Lloyd Bacon, producer (and former silent film comedian) Raymond Griffith, and director John G. Adolfi, best known at the time for his work with English actor George Arliss. Adolfi, who was around 50 years old and seemingly in good health, would not return.

II. The Director

Even dedicated film buffs may draw a blank when the name John Adolfi is mentioned. Although he directed more than eighty films over a twenty-year period beginning in 1913, most of those films are now lost. He worked in every genre, with top stars, and made a successful transition from silent cinema to talkies. He seems to have been a well-respected but self-effacing man, seldom profiled in the press.

According to his tombstone Adolfi was born in New York City in 1881, but the exact date of his birth is one of several mysteries about his life. His father, Gustav Adolfi, was a popular stage comedian and singer who emigrated to the U.S. from Germany in 1879. Gustav performed primarily in New York and Philadelphia, and was known for such roles as Frosch the Jailer in Strauss’ Die Fledermaus. But he was a troubled man, said to be a compulsive gambler, and after his wife Jennie died (possibly of scarlet fever) it appears his life fell apart. Gustav’s singing voice gave out, and then he died suddenly in Philadelphia in October 1890, leaving John and his siblings orphaned. (An obituary in the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent reported that Gustav suffered a stroke, but family legend suggests he may have committed suicide.) After a difficult period John followed in his father’s footsteps and launched a stage career, and was soon working opposite such luminaries of the day as Ethel Barrymore and Dustin Farnum. Early in the new century the young actor wed Pennsylvania native Florence Crawford; the marriage would last until his death.

When the cinema was still in its infancy stage performers tended to regard movie work as slumming, but for whatever reason John Adolfi took the plunge. He made his debut before the cameras around 1907, probably at the Vitagraph Studio in Brooklyn. There he appeared as Tybalt in J. Stuart Blackton’s 1908 Romeo and Juliet , with Paul Panzer and Florence Lawrence in the title roles. He worked at the Edison Studio for director Edwin S. Porter, and at Biograph in a 1908 short called The Kentuckian which also featured two other stage veterans, D.W. Griffith and Mack Sennett. Most of Adolfi’s work as a screen actor was for the Éclair Studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey, the first film capital. The bulk of this company’s output was destroyed in a vault fire, but a 1912 adaptation of Robin Hood in which Adolfi appeared survives. That same year he also appeared in a famous docu-drama, as we would call it, Saved from the Titanic. This ten-minute short premiered less than a month after the Titanic disaster, and featured actress Dorothy Gibson, who actually survived the voyage, re-enacting her experience while wearing the same clothes she wore in the lifeboat. (This film, unfortunately, is among the missing.) After appearing in dozens of movies Adolfi moved behind the camera.

Much of his early work as a director was for a Los Angeles-based studio called Majestic, where he made crime dramas, Westerns, and comedies, films with titles like Texas Bill’s Last Ride and The Stolen Radium. In 1914 the company had a new supervisor: D. W. Griffith, now the top director in the business, who had just departed Biograph. Adolfi was one of the few Majestic staff directors who kept his job under the new regime. A profile in the February 1915 issue of Photoplay describes him as “a tallish, good-looking man, well-knit and vigorous, dark-haired and determined; his mouth and chin suggest that their owner expects (and intends) to have his own way unless he is convinced that the other fellow’s is better.” It was also reported that Adolfi had developed something of a following as an actor, but that he dropped out of the public eye when he became a director. Presumably, that’s what he wanted.

Adolfi left Majestic after three years, worked at Fox Films for a time as a staff director, then freelanced. During the remainder of the silent era he guided some of the screen’s legendary leading ladies: Annette Kellerman (Queen of the Sea, 1918), Marion Davies (The Burden of Proof, 1918), Mae Marsh (The Little ‘Fraid Lady, 1920), Betty Blythe (The Darling of the Rich, 1922), and Clara Bow (The Scarlet West, 1925). Not one of these films survives. A profile published in the New York World-Telegram during his stint at Fox reported that Adolfi was well-liked by his employees. He was “reticent when the conversation turned toward himself, but frank and outspoken when it concerned his work. Mr. Adolfi is not only a director who is skilled in the technique of his craft; he is also a deep student of human nature.” Asked how he felt about the cinema’s potential, he replied, with unconscious irony, “it is bound to live forever.”

III. The Talkies

In spring of 1927 Adolfi was offered a job at Warner Brothers. His debut feature for the studio What Happened to Father? (now lost) was a success, or enough of one anyway to secure him a professional foothold, and he worked primarily at WB thereafter. Thus he was fortuitously well-positioned for the talkie revolution, for although talking pictures were not invented at the studio it was Sam Warner and his brothers, more than anyone else, who sold an initially skeptical public on the new medium. After Adolfi had proven himself with three talkie features Darryl Zanuck handed him an expensive, prestige assignment, a lavish all-star revue entitled The Show of Shows which featured every Warners star from John Barrymore to Rin-Tin-Tin.

Other important assignments followed. In March of 1930 a crime melodrama called Penny Arcade opened on Broadway. It was not a success, but when Al Jolson saw it he sensed that the story had screen potential. He purchased the film rights at a bargain rate and then re-sold the property to his home studio, Warner Brothers. Adolfi was chosen to direct, but was doubtless surprised to learn that Jolson had insisted that two of the actors from the Broadway production repeat their performances before the cameras. One of the pair, Joan Blondell, had already appeared in three Vitaphone shorts to good effect, but the other, James Cagney, had never acted in a movie. Any doubts about Jolson’s instincts were quickly dispelled. Rushes of the first scenes featuring the newcomers so impressed studio brass that both were signed to five-year contracts. While Adolfi can’t be credited with discovering the duo, the film itself, re-christened Sinners’ Holiday,remains his strongest surviving claim to fame: he guided Jimmy Cagney’s screen debut.

At this point the director formed a professional relationship that would shape the rest of his career. George Arliss was a veteran stage actor who went into the movies and unexpectedly became a top box office draw. He was, frankly, an unlikely candidate for screen stardom. Already past sixty when talkies arrived, Arliss was a short, dignified man who resembled a benevolent gargoyle. But he was also a journeyman actor, a seasoned professional who knew how to command attention with a sudden sharp word or a raised eyebrow. Like Helen Hayes he was valued in Hollywood as a performer of unblemished reputation who lent the raffish film industry a touch of Class, in every sense of the word.

In 1929 Arliss appeared in a talkie version of Disraeli, a role he had played many times on stage, and became the first Englishman to take home an Academy Award for Best Actor. Thereafter he was known for stately portrayals of History’s Great Men, such as Voltaire and Alexander Hamilton, as well as fictional kings, cardinals, and other official personages. The old gentleman formed a close alliance with Darryl Zanuck, whom he admired, and was in turn granted privileges highly unusual for any actor at the time. Arliss had final approval of his scripts and authority over casting. He was also granted the right to rehearse his selected actors for two weeks before filming began. All that was left for the film’s director to do, it would seem, would be to faithfully record what his star wanted. Not many directors would accept this arrangement, but John Adolfi, who according to Photoplay “was determined to have his own way unless he is convinced that the other fellow’s is better,” clearly had no problem with it. His first film with Arliss was The Millionaire, released in May 1931; and in the two years that followed Adolfi directed eight more features, six of which were Arliss vehicles. He had found his niche in Hollywood.

One of Adolfi’s last jobs sans Arliss was a B-picture called Central Park, which reunited the director with Joan Blondell. It’s a snappy, topical, crazy quilt of a movie that packs a lot of incident into a 58-minute running time. Central Park was something of a sleeper that earned its director positive critical notices, and must have afforded him a lively holiday from those polite period pieces for the exacting Mr. Arliss.

In spring of 1933, after completing work on the Arliss vehicle Voltaire, Adolfi accompanied Darryl Zanuck and his entourage to British Columbia to hunt bears. Arliss intended to follow Zanuck to his new company, while Adolfi in turn surely expected to follow the star and continue their collaboration. Things didn’t work out that way.

IV. The Hunting Trip

It’s unclear how long the men were hunting before tragedy struck. On Sunday, May 14th, newspapers reported that film director John G. Adolfi had died the previous week – either on Wednesday or Thursday, depending on which paper one consults – at a hunting camp near the Canoe River. All accounts give the cause of death as a cerebral hemorrhage. According to the New York Herald-Tribune the news was conveyed in a long-distance phone call from Darryl Zanuck to screenwriter Lucien Hubbard in Los Angeles. Hubbard subsequently informed the press. The N.Y. Times reported that the entire hunting party (Zanuck, Engel, Enright, Bacon, and Griffith) accompanied Adolfi’s remains in a motorboat down the Columbia River to Revelstoke. From there the body was sent to Vancouver, B.C., where it was cremated. Write-ups of Adolfi’s career were brief, and tended to emphasize his work with George Arliss, though his recent success Central Park was widely noted. John’s widow Florence was mentioned in the Philadelphia City News obituary but otherwise seems to have been ignored; the couple had no children.

V. The Aftermath

Darryl F. Zanuck went on to found Twentieth Century Pictures, a name suggested by his hunting companion Sam Engel. One of the company’s biggest hits in its first year of operation was The House of Rothschild, starring George Arliss and directed by Alfred Werker. The venerable actor returned to England not long afterwards and retired from filmmaking in 1937. In his second book of memoirs, published three years later, Arliss devotes several pages of warm praise to Zanuck, but refers only fleetingly to the man who directed seven of his films, John Adolfi, and misspells his name.

In 1935 Zanuck merged his Twentieth Century Pictures with Fox Films, and created one of the most successful companies in Hollywood history. He would go on to produce many award-winning classics, including The Grapes of Wrath, Laura, and All About Eve. Zanuck’s trusted associates at Twentieth-Century Fox in the company’s best years included Sam Engel, Raymond Griffith, and Lloyd Bacon, all survivors of the Revelstoke trip. Personal difficulties and vast changes in the film industry began to affect Zanuck’s career in the 1950s. He left the U.S. for Europe but continued to make films, and sporadically managed to exercise control over the company he founded. He died in 1979.

In 1984 a onetime screenwriter and film critic named Leonard Mosley, who had known Zanuck slightly, published a biography entitled Zanuck: The Rise and Fall of Hollywood’s Last Tycoon. Aside from his movie reviews most of Mosley’s published work concerned military matters, specifically pertaining to the Second War World. His Zanuck bio reveals a grasp of film history that is shaky at times, for the book has a number of obvious errors. Nevertheless, it was written with the cooperation of Darryl’s son Richard, his widow Virginia, and many of the mogul’s close associates, so whatever its errors in chronology or studio data the anecdotes concerning Zanuck’s personal and professional activities are unquestionably well-sourced.

When Mosley’s narrative reaches May 1933, the point when Zanuck is on the verge of founding his new company, we’re told that he and several associates decided to go on a hunting trip to Alaska. The location is not correct, but chronologically – and in one other, unmistakable respect – there can be no doubt that this refers to the Revelstoke trip. From Mosley’s book:

“There is a mystery about this trip, and no perusal of Zanuck’s papers or those of his former associates seems to elucidate it,” he writes. “Something happened that changed his whole attitude towards hunting. All that can be gathered from the thin stories that are still gossiped around was that the hunting party went on the track of a polar bear somewhere in the Alaskan wilderness [sic], and when the vital moment came it was Zanuck who stepped out to shoot down the charging, furious animal. His bullet, it is said, found its mark all right, but it did not kill. The polar bear came on, and Zanuck stood his ground, pumping away with his rifle. Only this time it was not ‘him or me,’ but ‘him’ and someone else. The wounded and enraged bear, still alive and still charging, swerved around Zanuck and swiped with his great paw at one of the men standing behind him – and only after it had killed this other man did it fall at last into the snow, and die itself. That’s the story, and no one seems to be able to confirm it nor remember the name of the man who died. The only certain thing is that when Zanuck came back, he announced to Virginia that he had given up hunting. And he never went out and shot a wild animal again, not even a jackrabbit for his supper.”

VI. The Coda

Was John Adolfi killed by a bear? It certainly seems possible, but if so, why didn’t the men in the hunting party simply report the truth? Even if their boss was indirectly responsible, having fired the shots that caused the bear to charge, he couldn’t be blamed for the actions of a dying animal. But it’s also possible the event unfolded like a recent tragedy on the Montana-Idaho border. There, in September 2011, two men named Ty Bell and Steve Stevenson were on a hunting trip. Bell shot what he believed was a black bear. When the bear, a grizzly, attacked Stevenson, Bell fired again – and killed both the bear and his friend.

That seems to be the more likely scenario. If Zanuck fired at the wounded bear, in an attempt to save Adolfi, and killed both bear and man instead, it would perhaps explain a hastily contrived false story. It would most definitely explain the prompt cremation of Adolfi’s body in Vancouver. Back in Hollywood Joe Schenck was busy raising money, and lots of it, to launch Zanuck’s new company. Any unpleasant information about the new company’s chief – certainly anything suggestive of manslaughter – could jeopardize the deal. A man hit with a cerebral hemorrhage in the prime of life is a tragedy of natural causes, but a man sprayed with bullets in a shooting, accidental or not, is something else again. That goes double if alcohol was involved, as it reportedly was on Zanuck’s earlier hunting trips.

Of course, it’s also possible that Adolfi did indeed suffer a cerebral hemorrhage. Like his father.

John G. Adolfi is a Hollywood ghost. Most of his works are lost, and his name is forgotten. (Even George Arliss couldn’t be bothered to spell it correctly.) Every now and then TCM will program one of the Arliss vehicles, or Sinners’ Holiday. Not long ago they showed Adolfi’s fascinating B-picture Central Park, that slam-bang souvenir of the early Depression years in which several plot strands are deftly inter-twined. One of the subplots involves a mentally ill man, a former zoo-keeper who escapes from an asylum and returns to the place where he used to work, the Central Park Zoo. He has a score to settle with an old nemesis, an ex-colleague who tends the big cats. As the story approaches its climax, the escaped lunatic deliberately drags his enemy into the cage of a dangerous lion and leaves him there. In the subsequent, harrowing scene, difficult to watch, the lion attacks and practically kills the poor bastard.

by William Charles Morrow

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

My sources for this article, in addition to the Mosley biography cited in the text, include Stephen M. Silverman’s The Fox That Got Away: The Last Days of the Zanuck Dynasty at Twentieth-Century Fox (1988), and Marlys J. Harris’s The Zanucks of Hollywood: The Dark Legacy of an American Dynasty (1989). For material on John Adolfi I made extensive use of the files of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Special thanks to James Bigwood for his prodigious research on the Adolfi family genealogy, and to Mary Maler, John Adolfi’s great-niece, for information she provided on her family.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

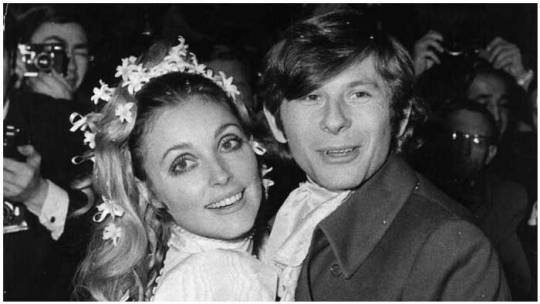

The Life of Roman Polanski

The director of our current movie under review, Roman Polanski, is a man that has been surrounded by sadness and controversy. I think that he is a great director and an amazing creator of the visual arts, but he has a major flaw that makes me very glad he is nowhere near me. I think a statement like that deserves some explanation, but know that a lot of my take is based on opinion. I was not alive when a lot of his issues occurred so I base my opinion on news and official record statements. I will try and rely on recorded facts as much as possible and make a point to mention if something is not proven. I also encourage anyone who is interested to find out more because it is a fascinating story.

Polanski started off the in a pretty bad way as he was born in 1933 in Paris during the height of Nazi reign in Europe. He was moved to Krakow in 1937 right before the German invasion and his parents were taken in raids. He was kept alive in foster homes under an assumed identity and was lucky to survive. His mother died in Auschwitz, but he was reunited with his father after the war in 1946. Roman had quite the artistic eye and used it for both photography and filming. He attended the National Film School in Lodz, Poland and started directing short films that gained recognition. One film in particular was called Bicycle. It was a true story of a thief that tricked Polanski out of his money when purchasing a bicycle and instead beat Polanski around the head with the butt of a gun. The thief was found and eventually executed for past crimes including 3 murders.

After graduating in 1959, Polanski went to France and continued to make short films. He reported that there was a problem with xenophobia at the time since so many Polish people had dispersed around Europe after the war. He went to England and made three movies between 1965 and 1968 that gained recognition in America: Repulsion, Cul-de-sac, and Dance of the Vampires. A young woman named Sharon Tate played a role in Dance of the Vampires and Polanski fell in love. He married her in 1968 in England, and they moved to the U.S. so he could make movies in Hollywood. His first film in the states was a horror film entitled Rosemary’s Baby, one of the highest rated horror films of all time. Polanski had a beautiful young wife, a son on the way, a hit movie with more work coming, and great prospects for life in the United States.

As horrific as his formative years were, I am surprised to find myself writing that this is when Polanski’s life really went out of control. On August 9th, 1969, cult members who followed a man named Charles Manson broke into the Polanski home in Los Angeles and murdered the 8 month pregnant Sharon Tate and four friends that were at the home. Polanski had been working in London on a new film and wasn’t there that night. He says to this day that it is by far the greatest regret of his life. Remember this. It seems that some wires got crossed as far as Roman’s thinking process because his behavior really took a turn.

His films had been dark and violent in the past, but they started to have sexual undertones with more graphic nudity. His first movie back after the loss of his wife was Macbeth, a movie that was rated X at the time for graphic nudity and violence. Polanski later said that he was in a dark place, but the media would find things in his movies always looking for a story. He hated the media after the sensationalism and lack of privacy involved with the loss of his wife and son. Next came an extremely odd road trip sex comedy that was appropriately called What?. And then came his last work filmed in the United States and the film he was probably best known for, Chinatown. I don’t want to go over the film too much since it is the film currently under review for the group, but it is very dark and has an extremely down beat ending.

And then another crime was committed in Polanski’s life that would haunt while simultaneously erasing any good will the American public had for him. He was charged for drugging and raping a 13-year-old girl who modeled for him during a Vogue photoshoot. It was recorded as occurring at the Bel Air estate of Jack Nicholson. There is no question about this encounter as Polanski was arrested and confessed to the charges. He thought he was going to receive probation and timed served for a guilty plea, but the judge was reported to have changed his mind and was planning to reject the plea and give Polanski prison time for all charges. This would result in up to 50 years in jail and what amounted to life in prison. Polanski would not serve this sentence so he fled the country to France where he would not be extradited.

The charges are still pending and there is no statute of limitations on rape in the United States, so Polanski is on a list of people that if found outside of certain countries will be immediately sent back to the U.S. to face charges. He has dual citizenship in France and Poland; both countries do not extradite citizens. He went on to make one of his best works, a film called Tess, while in Europe. It was a great success and Polanski was nominated for Best Director. The film ended up winning three Academy Awards (none for Polanski). So it seemed that this acclaimed director would live in France and hope that things would blow over. He settled a civil suit in court with the girl and she went on to marry and says she forgives Polanski. But it didn’t end...

Because the woman was in the U.S. and Polanski was not, she was harassed by the press to speak out and tell her story. She reported that the media did much more harm to her and her family than Polanski did. That is a very strong statement considering the charges. Things finally cooled down somewhat when Polanski married an actress from one of his films, Emmanuelle Seignor in 1989. The couple have two kids together and things were apparently going fine in France.

Things remained well through the 90s although nothing Polanski did got much attention. It seemed he would simply live out his life quietly in France. Then in 1999, he came out with a film called The Ninth Gate that garnered attention since it starred the very popular Johnny Depp. Polanski was back on his game and he directed and produced a film called The Pianist. It stars Adrian Brody and told the story of a Polish-Jewish composer who survived the concentration camps because of goodwill received from German officers that appreciated his work. It is a masterpiece and earned Polanski the award for Best Director. He could not accept the award in person because he would be arrested, so Harrison Ford accepted it on his behalf and took it to him in France. A strange little detail about this is that The Pianist was also up for best picture, but stirrings about Polanski’s past were brought up by a competing producer to throw the award. There is no real proof of this, but the man said to have done this was quite powerful in Hollywood at the time. Ironically, that man who was said to remind people of old rape charges was none other than Harvey Weinstein. I don’t have proof of this, but it is an interesting story. One of those “I heard it is said that” kind of things from TMZ.

Anyway, these reminders had people trying to interview Polanski and his wife about the past and he basically said that people needed to move past it. This does not tend to go over very well with the American public or the legal system and Polanski was arrested while in Switzerland and held in Zurich. Public sentiment in America, France, and Poland leaned towards Polanski being sent to America to face trial. The Swiss judge denied extradition and Polanski was sent back to France. There were requests in 2014 by US courts that Poland send Polanski to stand trial since there was question concerning the conduct of the original judge in Polanski’s case. It was believed that Polanski would be given some form of probation, but it also meant he could travel. Polish courts ruled that Polanski had served his punishment and should not have to face U.S. courts again. In 2016, it was presented by Polish officials that no amount of time could account for the crime of rape, but the decision of the lower court was held.

In 2018, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences removed Polanski as a member. Strangely, that same year, they offered a membership to his wife (who loudly said no).

So the final say about how to feel about Polanski and his works lies firmly on the individual. Here is all the information about the trial that can keep it nice and ambiguous for you. The judge, the lead prosecutor, and the LA County Deputy DA at the time all admitted bias against Polanski. He would not have gotten a fair trial and would likely have ended up in prison for life. The prosecutor said later in an interview for a documentary that he was not surprised at all that Polanski left and it would have been a media circus. Polanski paid the victim almost a million dollars in civil settlement money and she said she doesn’t want to see any further prosecution. Okay. In 2017, a website run by Matan Uziel was sued by Polanski for libel when it was posted that 5 other women had come forward and accused Polanski of sexual assault. Polanski did not show up in court so Uziel was dismissed of charges. Uziel requested specifically that the cases not be dropped so that Polanski could not try and sue him at a future date. It is true that, in 2010, an English actress accused Polanski of “forcing himself” on her during filming of the movie Pirates. In 2017, a Swiss woman accused Polanski of raping her in the 70s when she was only 15. The same month, another woman accused him of assaulting her in 1975 when she was only 10. Finally, in 2019, a former actress model from France said that Polanski violently raped her at a Swiss chalet in 1975.

So what can you say about the man? His early life was tragedy and misery. The loss of his wife and child was horrific. He seemed like he was in a very bad place in the 70s. I don’t want to give credence to accusation without proof, but it can be sure that he committed at least one sexual assault of an under aged girl. He ran from his trial because he knew it would not be fair, but he was still never held accountable in a court of law for what he did. He has been forced to stay in Poland and France, but he is wealthy with a wife and kids, never seeing the jail time for what he did. And if it is true that he has committed other crimes like this, then he needs to be in jail. But could he ever get a fair day in court at this point? The man is 87 and will likely die soon, likely before any sentencing could occur. Also, how reliable is testimony from any parties about things that happened between 40-50 years ago? Everything he is accused of seems to have happened after the death of Sharon Tate and before his marriage to his current wife, so it seems like his behavior was linked to his state of mind and he is no longer in that state. That may explain things but it does not forgive them.

I don’t know. This is probably why I chose psychology instead of law enforcement or criminal justice. Trying to decide if someone has adequately paid for crimes they have committed is not my specialty. It will be a moot point soon enough because he will be dead. So what do we do with the guy? He has encountered both great suffering and great joy in his life. He as also caused great suffering and great joy. I guess it is more about how he will be remembered at this point. I would be curious to hear what others think.

#roman polanski#sharon tate#chinatown#rosemary's baby#film director#extradition#court charges#life and times#assault#70s#media coverage#introvert#introverts

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once Upon a Time in America Is Every Bit as Great a Gangster Movie as The Godfather

https://ift.tt/38Ku8cF

This article contains Once Upon a Time in America spoilers.

The Godfather is a great movie, possibly the best ever made. Its sequel, The Godfather, Part II, often follows it in the pantheon of classic cinema, some critics even believe it is the better film. Robert Evans, head of production at Paramount in the early 1970s, wanted The Godfather to be directed by an Italian American. Francis Ford Coppola was very much a last resort. The studio’s first choice was Sergio Leone, but he was getting ready to make his own gangster epic, Once Upon a Time in America. Though less known, it is equally magnificent.

Robert De Niro, as David “Noodles” Aaronson, and James Woods, as Maximillian “Max” Bercovicz, make up a dream gangster film pairing in Once Upon a Time in America, on par with late 1930s audiences seeing Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney team for The Roaring Twenties or Angels with Dirty Faces. Noodles and Max are partners and competitors, one is ambitious, the other gets a yen for the beach. One went to jail, the other wants to rob the Federal Reserve Bank.

Throw Joe Pesci into the mix, in a small part as crime boss Frankie Monaldi, and Burt Young as his brother Joe Monaldi, and life gets “funnier than shit,” and funnier than their more famous crime films, Goodfellas and Chinatown, respectively. Future mob entertainment mainstays are all over Once Upon a Time in America too, and they are in distinguished company. This is future Oscar winner Jennifer Connelly’s first movie. She plays young Deborah, the young girl who becomes the woman between Noodles and Max, and she even has something of a catch-phrase, “Go on Noodles your mother is calling.” Elizabeth McGovern delivers the line as adult Deborah.

When Once Upon a Time in America first ran in theaters, there were reports that people in the audience laughed when Deborah is reintroduced after a 35-year gap in the action. She hadn’t aged at all. But Deborah is representational to Leone, beyond the character.

“Age can wither me, Noodles,” she says. But neither the character nor the director will allow the audience to see it beyond the cold cream. Deborah is the character Leone is answering to. She also embodies the fluid chronology of the storytelling. She is its only constant.

The rest of the film can feel like a free fall though. Whereas The Godfather moved in a linear fashion, Once Upon a Time in America has time for flashbacks, and flashbacks within flashbacks, and detours that careen between the violent and the quiet. It’s a visceral experience about landing where we, and this genre, began.

Growing up Gangster

Both The Godfather and Once Upon a Time in America span decades; it’s the history of immigrant crime in 20th century America. But they differ on chronological placement. Once Upon a Time is set in three time-frames. The earliest is 1918 in the Jewish ghettos of New York City’s Lower East Side.

Young Noodles (Scott Tiler), Patrick “Patsy” Goldberg (Brian Bloom), Philip “Cockeye” Stein (Adrian Curran) and Dominic (Noah Moazezi), are a bush league street gang doing petty crimes for a minor neighborhood mug, Bugsy (James Russo). New on the block, Max (Rusty Jacobs) interrupts the gang as they’re about to roll a drunk, and Max makes off with the guy’s watch for himself. He soon joins the gang, and they progress to bigger crimes.

The bulk of the film takes place, however, from when De Niro’s Noodles gets out of prison in 1930, following Bugsy’s murder, and lasts until the end of Prohibition in 1933. Max, now played by Woods, has become a successful bootlegger with a mortuary business on the side. With William Forsythe playing the grown-up Cockeye and James Hayden as Patsy, the mobsters go from bootlegging through contract killing, and ultimately to backing the biggest trucking union in the country as enforcers. They enjoy most of their downtime in their childhood friend Fat Moe’s (Larry Rapp) speakeasy. Noodles is in love with Fat Moe’s sister, Deborah, who is on her way to becoming a Hollywood star. The gang’s rise ends with the liquor delivery massacre.

The final part of the film comes in 1968. After 35 years in hiding, Noodles is uncovered and paid to do a private contract for the U.S. Secretary of Commerce Christopher Bailey… Max by a different name who 35 years on has been able to feign respectability and make Deborah his mistress. An entire life has become a façade.

Recreating a Seedier Side of New York’s Immigrant Past

While The Godfather is an adaptation of Mario Puzo’s fictional bestseller, Once Upon a Time in America is based on the autobiographical crime novel, The Hoods. It was written by Herschel “Noodles” Goldberg, under the pen name of Harry Grey while he was serving time in Sing-Sing Prison.