#information processing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Why Do Some Autistic People Need Extra Processing Time?

The Autistic Teacher

#autism#actually autistic#information processing#why autistic people need more processing time#executive function#language processing#sensory processing#neurodivergence#neurodiversity#actually neurodivergent#feel free to share/reblog#The Autistic Teacher (Facebook)

397 notes

·

View notes

Text

idk why i hate reading and math and processing information

like i cant read most fanfics, i havent read a single book for my english class all the way through, ive js been bullshitting everything, and im failing math cus i dont even try :/

#eros says shit#autism#actually autistic#information processing#vent#kinda ig#UGHHGHG pls tell me this isnt js me

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trump had a chance to win over a lot of west coast liberals, and now he’s blown it with the way ICE has been conducting themselves on the west coast, on top of the very obvious and severe delay in the transfer of intel and information on and from the west coast to the east coast, and especially to the White House in our nation’s capital. The difference between the west coast and the east coast is like night and day, like they may as well be governed as two entirely separate countries, and the west coast contributes more to the nation’s GDP than all of the East Coast except for maybe New York because of Wall Street, and big tech essentially now controls the stock market, and AI essentially controls big tech. Hmm, I wonder who controls Ai, if any people, group of people, or organization has any level of actual control over AI, because I’ve never known humans to rush so greatly, putting their needs and responsibilities, on top of also putting societal needs and responsibilities, to the wayside, just to build something like Americans built Ai. The only thing that may compare is the building of some of the pyramids that exist on Earth.

#Trump#immigration#west coast#east coast#liberals#conservatives#government#federal government#information#intel#intelligence gathering#information processing#information travel#ICE#AI#artifical intelligence#White House#Washington D.C.#big tech#stocks#stock market#NYSE#NYC#Wall Street#GDP#taxes#control#Apple#AGI#pyramids

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unraveling Confirmation Bias: How Our Beliefs Shape Our Perspectives

Confirmation bias is a cognitive bias that leads people to interpret, remember, or search for information in ways that confirm their preconceptions or hypotheses. Here are some common things people use as confirmation bias:

Selective Exposure: People tend to expose themselves to information sources and media that align with their existing beliefs.

Selective Perception: They interpret ambiguous information in a way that supports their beliefs.

Selective Retention: People remember information that confirms their existing beliefs better than information that contradicts them.

Cherry-Picking Data: They selectively choose data or examples that support their viewpoint while ignoring or dismissing data that contradicts it.

Seeking Like-Minded Individuals: People often engage with communities or social groups that share their beliefs, reinforcing their existing views.

Misinterpreting Statistics: Individuals may misinterpret statistical data to support their preconceived notions.

Overvaluing Personal Experience: Personal anecdotes and experiences are given more weight than they should be in forming opinions.

Ignoring Expert Opinion: Dismissing expert opinions or scientific consensus when it contradicts one's beliefs.

Confirmation in Social Media Echo Chambers: Social media algorithms often expose users to content that aligns with their views, creating echo chambers where confirmation bias thrives.

Biased Information Search: When researching a topic, people may conduct biased searches, seeking out sources that confirm their beliefs.

Emotional Attachment: Emotional attachment to one's beliefs can make it difficult to consider alternative viewpoints objectively.

Attribution Error: People often attribute their successes to their abilities and their failures to external factors or situations, confirming their self-beliefs.

Groupthink: In group settings, individuals may conform to the group's beliefs to avoid conflict or maintain group cohesion.

Being aware of these tendencies is the first step in mitigating confirmation bias and promoting more open-minded and critical thinking.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#psychology#ethics#politics#Confirmation Bias#Cognitive Biases#Belief Systems#Critical Thinking#Perspective#Information Processing#Decision-Making#Bias Awareness#Cognitive Psychology#Rational Thinking

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Color slides. sigh An orphan technology.

We had more than 150,000 slides in our Art History department collection (and we're a small liberal arts college, not a big university) when Kodak announced they were going to cease production on slide projectors, then service for slide projectors, then around 2010 began discontinuing Ektachrome production.

We were already well along the way to a digital transition, but this forced the project. Then came Artstor. Now Big Database has folded Artstor into Jstor - we'll see how that works.

Information storage. None of this is neutral.

From 1969 to 2008 John Margolies photographed the eccentric roadside architecture and ephemera of the US. @librarycongress bought the lot, a total of 11,710 colour slides, and lifted all copyright restrictions on them. Here’s our highlights: https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/john-margolies-photographs-of-roadside-america

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Enhancing Decision-Making in Professional Cricket: A Multifaceted Approach

Cricket is a sport renowned for its strategic complexity and dynamic nature, requiring players to make rapid and precise decisions under immense pressure. The ability to effectively analyze information, assess options, and execute the optimal response can significantly impact match outcomes. This analysis delves into the key factors influencing decision-making in professional cricket and proposes strategies for enhancement.

Key Factors Influencing Decision-Making

Professional cricketers operate in a complex environment where effective decision-making hinges on several key factors:

Information Integration: Cricketers gather information from various sources, including stable contextual factors (opponent preferences, surface condition, boundary size), dynamic contextual factors (field settings, match situation, recent deliveries), and kinematic cues (bowler's run-up, batter's preparatory movements).

Option Awareness: Skilled players possess a heightened awareness of available options, weighing risks and rewards, considering personal strengths, and anticipating opponent manipulation.

Interpersonal Decision-Making: The bowler and batter engage in a dynamic interplay, each attempting to manipulate the other's decision-making through their actions and choices.

Front-Foot Dominance: In limited-overs cricket, batters tend to favor front-foot strokes to maximize run-scoring opportunities.

Bowling Length Influence: The length at which the ball bounces significantly influences the batter's footwork and stroke selection.

Strategies for Improvement

To enhance decision-making abilities in professional cricket, a multifaceted approach is necessary:

Enhanced Information Processing: Develop training programs that focus on improving perceptual-cognitive skills, enabling cricketers to process information more efficiently and accurately.

Video Analysis and Simulation: Utilize video analysis and simulation technology to expose players to various match scenarios and provide feedback on their decision-making.

Mindfulness and Focus Training: Incorporate mindfulness and focus training to help players remain calm and composed under pressure, facilitating clear decision-making.

Tactical Planning and Strategy: Develop detailed tactical plans and strategies, considering opponent strengths and weaknesses, match conditions, and different game formats.

Interpersonal Dynamics: Train players to understand and anticipate opponent manipulation, recognizing the dynamic interplay between bowler and batter.

Decision-making in professional cricket is a complex process that requires the integration of information, awareness of options, and the ability to anticipate and respond to opponent actions. By implementing targeted training programs, utilizing technology, and developing a deeper understanding of the game's dynamics, cricketers can enhance their decision-making abilities and elevate their overall performance.

PASS's Services:

Annual Guidebooks: PASS publishes annual guidebooks for various sports, summarizing the latest research and providing practical recommendations for training and performance optimization.

Custom Reports: PASS offers custom reports that delve deep into specific performance challenges, providing tailored solutions based on the latest scientific evidence.

Researcher Exchange: PASS facilitates workshops and Q&A sessions with leading sports scientists, allowing coaches and athletes to gain valuable insights and connect with experts in the field.

The potential of sports science to revolutionize training and performance is vast, but it remains largely untapped in many areas of athletics. By embracing research-backed principles and utilizing the services of organizations like PASS, coaches and athletes can unlock new levels of performance, reduce the risk of injuries, and achieve their full potential.

About PASS | Practical Application of Sport Science:

PASS helps top sports teams make better decisions using science. The teams ask questions like: “how to manage workload; how to improve decision-making; what is an optimal periodization program”. PASS takes a deep dive into all relevant research articles, figures out what's useful, and gives the teams specific advice they can immediately implement – only things that have been scientifically proven.

Explore the resources available at PASS (https://sportscience.pro/) and discover how sports science can transform your approach to training and performance.

#sports science#PASS#cricket#decision-making#sports psychology#performance enhancement#information processing#tactical planning

0 notes

Text

The Harmony of Realms: Understanding Consciousness through Language, Imagination, and Behavior

youtube

The discussion with Tor Nørretranders, a Danish author known for his work on consciousness, delves into the nature of consciousness, sensory perception, and how humans process information. Nørretranders' book The User Illusion is a foundational text in this field, exploring consciousness as a reduction function, a concept that resonates with Aldous Huxley's idea of the "reducing valve" of consciousness.

The conversation begins by addressing modern civilization's obsession with predictability and control, which, Nørretranders argues, leads to a dulled and overly simplistic way of interacting with the world. He advocates for a "refresh" of sensory inputs to awaken a more nuanced and engaged state of mind, suggesting that our minds naturally crave a balance between order and novelty.

Jordan Peterson, the host, shares his understanding of consciousness as a multi-tiered phenomenon, structured from material reality up through behavioral, imaginative, and linguistic realms. Nørretranders aligns with this, adding that human sensory systems absorb around 11 million bits of information per second, yet our conscious awareness processes only about 16 bits per second. This enormous gap suggests that much of what we experience is filtered out, and consciousness serves as a simplified interface with reality.

Peterson's framework suggests that each layer builds upon the last: the material realm of patterns supports behavioral expressions, which are then represented in the imaginative realm (such as dreams or literature), and finally mapped in the linguistic realm. Nørretranders appreciates this layered approach but emphasizes starting with the basic observation of sensory input and our brain's selective filtering process.

Throughout the conversation, they explore how language unpacks compressed ideas and how understanding is built through a harmony of these different realms. The dialogue provides a rich philosophical and scientific look at consciousness, encouraging reflection on how much of reality is accessible to us and how much remains beyond the scope of conscious perception.

Understanding Consciousness: Patterns, Perception, and the Limits of Awareness

In our modern age, we tend to view consciousness as an advanced and distinctively human phenomenon. We value our awareness, our capacity for language, and our imaginative abilities, all of which seem to separate us from other species. Yet, Danish author and philosopher Tor Nørretranders, in his work, particularly his influential book The User Illusion, challenges us to rethink our understanding of consciousness by emphasizing its limitations and functions as a “reducing” mechanism. Nørretranders argues that the human brain does not perceive reality in its fullness but compresses and simplifies vast amounts of sensory information to create a coherent and manageable experience. This essay explores the themes presented by Nørretranders and others on consciousness as a layered phenomenon, touching upon the material, behavioral, imaginative, and linguistic realms, and investigates how consciousness serves as a simplifying force rather than an all-encompassing awareness.

The Material and Behavioral Realms

Consciousness begins in what Nørretranders describes as a world of patterns—a "material realm" where objects and processes persist in intricate, interconnected forms. Here, patterns of varying scales and durations create a stable environment that humans and animals navigate daily. From the rhythms of nature to the structure of objects around us, the material world holds a vast amount of information that is essential for survival but beyond the full grasp of any one creature.

In addition to this material realm, living beings also exist within a "behavioral realm," where they interact with each other and respond to their environment. This realm is not just about physical interactions but also about the implicit codes and patterns that living beings, especially humans, use to navigate the physical world. For example, animals and humans both leave tracks in their environments—birds in flight patterns, wolves in social hierarchies, and humans in roads and pathways. These behaviors serve as a form of mapping that reflects the underlying patterns in the material world, creating an alignment between creatures and their environment.

The behavioral realm is also where social structures, instincts, and survival mechanisms operate. In the context of consciousness, however, this realm represents a level of perception that is instinctual and subconscious, with humans perhaps exhibiting the most complex forms of behavior that can impact their physical surroundings and each other.

The Imaginative Realm: Capturing Behavioral Patterns

While animals operate effectively within the material and behavioral realms, humans add another layer to their consciousness: the imaginative realm. This realm allows us to form representations of our behavioral experiences in symbolic ways—dreams, stories, myths, and art, all of which mirror the world around us but also interpret and transform it. According to Nørretranders, the imaginative realm lets us hold onto patterns from the behavioral realm and apply them to new, abstract contexts. In dreams, for instance, we replay and explore these patterns through characters and dramas, albeit in surreal and often fragmented ways.

The imaginative realm allows us to capture and conceptualize experiences beyond the immediate physical moment, embedding them in symbols, stories, and characters. Literature, for instance, helps transform real experiences into a coherent narrative that conveys universal emotions and situations. In this sense, the imaginative realm is where meaning-making begins, shaping our collective understanding of existence and providing a space for individuals to explore and interpret the complex, often contradictory, aspects of their own experiences.

The Linguistic Realm: Mapping and Unpacking the Imagination

Nørretranders further asserts that language—our ability to communicate through symbols and structure thoughts—is a realm where we take complex ideas and compress them into words and sentences. Language, in his view, is a form of "unpacking" the imagination. Just as we might condense a multifaceted experience into a brief description, language allows us to simplify complex ideas for easier communication, though at the cost of nuance and depth.

Language both connects and restricts us. It enables us to share our thoughts and experiences, but it also places limits on our capacity to express the full richness of our inner worlds. For example, an artist may find that words cannot capture the essence of a painting, or a philosopher may struggle to convey abstract ideas. This challenge underlines Nørretranders' idea that language is a reducing function—while it opens new ways to connect with others, it also distills the vast landscape of consciousness into manageable, often oversimplified fragments.

Consciousness as a Reducing Function: From 11 Million Bits to 16

One of the most striking insights in Nørretranders’ work is his assertion that consciousness operates as a filtering mechanism. He highlights that the human sensory system receives approximately 11 million bits of information per second from the environment. However, only around 16 bits of this information reach our conscious awareness. This discrepancy underscores how our minds function more like high-powered reduction machines than broad-spectrum receivers.

This vast filtering process suggests that consciousness does not necessarily give us a "truer" or "fuller" view of reality. Instead, it distills a limited snapshot that we can handle and use. For example, when walking through a forest, we don’t perceive every leaf or branch; our minds focus on relevant patterns—a potential path, the sounds of nearby animals, or obstacles to avoid. By filtering out excess information, consciousness allows us to navigate the world efficiently without being overwhelmed by sensory overload.

The Problem with Modern Civilization's Predictive Mindset

One critique Nørretranders offers is that modern civilization's fixation on control and predictability has led to a kind of sensory and imaginative stagnation. In our efforts to manage and predict all aspects of life, we lose a measure of spontaneity and creativity. This is a mindset that resists the ambiguity and uncertainty that are fundamental to a fuller experience of life. When we insist on linear predictability, our minds become dull, as we no longer allow ourselves to be “irritated” by the unexpected stimuli that keep consciousness awake and active.

Nørretranders suggests that to counter this, we should find ways to refresh our sensory inputs and step outside the routine constraints of the predictable world. Engaging in creative, unstructured activities such as exploring nature, creating art, or even engaging with stories and psychedelics are some ways to reconnect with the richness of experience. These activities bring us closer to the realms of imagination and sensation, reminding us of the vibrancy that often gets lost in our pursuit of efficiency and control.

Toward a Holistic Understanding of Consciousness

Ultimately, Nørretranders’ approach suggests that consciousness cannot be fully understood without acknowledging its layers and limitations. Each realm—material, behavioral, imaginative, and linguistic—contributes to our experience of reality but also filters and shapes it in distinct ways. The material and behavioral realms anchor us to our environment; the imaginative realm offers symbols and narratives that enrich our experiences, and the linguistic realm allows us to share and connect but also constrains and simplifies.

By conceptualizing consciousness as a reducing function, Nørretranders brings forth a humbling perspective. Humans are not passive observers of a full reality; we actively construct our reality by selecting, interpreting, and often simplifying information. This conception of consciousness invites us to embrace both the power and the limitations of our awareness. Instead of seeking to control and predict every aspect of our lives, we might benefit from an openness to the unknown, allowing our senses to be “irritated” and refreshed by the world’s complexity.

In conclusion, the layered, limited, and often reductive nature of consciousness reveals that understanding does not equate to perceiving everything fully. Instead, true understanding may involve an appreciation of consciousness as a dynamic, filtering process that enables us to engage with the world without becoming overwhelmed by its vastness. By balancing predictability with spontaneity, structure with imagination, we can deepen our experience of consciousness in a way that honors both its expansive possibilities and its inherent constraints.

Consciousness and the Emergence of Self: Beyond Perception to the Foundations of Identity

In exploring the concept of consciousness, much attention is given to sensory processing, the filtering of information, and our experience of reality as a simplified construct. Yet, there remains a deeper, perhaps more complex, question about the emergence of the self within this realm of consciousness. If our perception is limited, filtered, and partial, what does that mean for the self we believe to inhabit? Where does identity arise within this conscious framework, and what are the mechanisms by which a stable sense of self comes to exist? This essay ventures into the subtler aspects of consciousness, particularly the emergence of self-awareness, memory, and the cognitive constructs that ground identity, exploring how these elements shape our lives in ways beyond sensory experience.

The Self as a Construct in Consciousness

In the study of consciousness, the self can be seen as an emergent property—a product of various cognitive processes that interact to create a consistent, albeit dynamic, sense of identity. Unlike raw perception, which involves interpreting immediate sensory input, the construction of self involves the integration of past experiences, memories, desires, and future intentions. This integration gives rise to what we call the “self,” a narrative that we continuously update to make sense of who we are, where we have been, and where we are going.

Neuroscientists and psychologists argue that the brain constructs this sense of self by assembling fragments of sensory experiences, memories, and abstract concepts into a coherent whole. This self-narrative serves a vital function, helping us navigate the world with a consistent sense of agency and continuity. However, this narrative can also be a source of rigidity, as the self, once constructed, seeks stability and resists change—even when change is necessary for growth. Our beliefs, values, and personality traits become ingrained, creating a sense of permanence that can become a psychological cage if not balanced with openness to new experiences.

The Role of Memory in Shaping Identity

Memory plays a critical role in this process of self-construction. Our memories act as a repository of past experiences that feed into our present understanding of who we are. Each memory is not a perfect reflection of the past but a reconstruction shaped by current emotions, beliefs, and cognitive biases. Research has shown that each time we recall a memory, it changes slightly, influenced by our present context and state of mind. Thus, memory is not only a tool for storing information but also an active participant in shaping our identity, with each recollection subtly rewriting our self-narrative.

In this light, memory functions less like a recording device and more like an editor, continuously refining the story of who we are. This malleable quality of memory means that identity is not a fixed entity but an ongoing process. As our memories shift over time, so does our sense of self. People who have experienced trauma, for example, often find that their identity becomes heavily shaped by those experiences, as memories of the trauma reshape how they view themselves and the world. Therapy can often involve reframing these memories, allowing individuals to reconstruct their narratives and, in doing so, change their self-conception.

Intention and Future-Self Projection

While memory anchors us to our past, the mind also projects itself forward, envisioning future possibilities and constructing goals and desires. This ability to envision a “future self” is another crucial aspect of consciousness that distinguishes humans from other species. It allows us to not only plan for the future but also to envision who we might become, setting goals that align with this envisioned self. In this way, intention acts as a bridge between the present self and the future self, motivating actions that serve to realize this projected identity.

The process of projecting oneself into the future is not merely about practical planning but also deeply influences our current identity. Studies in psychology suggest that individuals who have a strong sense of their “future self” tend to make decisions that are more in line with their long-term goals, even if it means sacrificing immediate gratification. Conversely, people who struggle to connect with their future self may be more prone to impulsive behaviors or decisions that undermine their future well-being. This future-self connection highlights the importance of temporality in consciousness—our sense of self is as much about who we were and who we will be as it is about who we are now.

The Dynamic Interplay of Self-Perception and Social Identity

Our sense of self is also deeply influenced by our interactions with others. From a young age, our identity is shaped by the feedback and perceptions of those around us—parents, teachers, friends, and society at large. This concept of the “social self” was notably explored by sociologist Charles Cooley in his theory of the “looking-glass self.” Cooley proposed that our self-concept is, to a large extent, a reflection of how we believe others perceive us. In essence, we form our self-identity in part by internalizing others' views and judgments.

This social dimension of identity has profound implications for how we experience consciousness. On one hand, social identity provides a sense of belonging and shared values, reinforcing our sense of who we are within a community. On the other hand, it can limit self-perception, as individuals often conform to societal expectations, suppressing parts of themselves that do not align with these external perceptions. This duality—being both liberated and constrained by social identity—illustrates the complexity of consciousness. We are not isolated minds but deeply interconnected beings, shaped by the social worlds we inhabit.

Cognitive Dissonance and the Evolution of the Self

An interesting phenomenon that arises in the context of self-awareness and social identity is cognitive dissonance, a psychological state where one experiences discomfort due to conflicting beliefs, values, or behaviors. Cognitive dissonance often serves as a catalyst for growth and change, prompting individuals to reassess their beliefs and realign their actions with their evolving sense of self.

For example, someone may hold a belief about their moral integrity but act in a way that contradicts that belief, leading to an internal conflict. To resolve this discomfort, the person may either change their behavior or adjust their self-conception to accommodate the inconsistency. This process underscores the fluidity of the self, as we are continuously adjusting our identity to maintain internal coherence. Cognitive dissonance, therefore, becomes a mechanism through which consciousness and identity evolve, allowing individuals to navigate and adapt to changing environments and new insights.

Self-Transcendence: Beyond the Individual Self

One of the most profound questions in the study of consciousness is whether the self, as a construct, can dissolve or transcend. Many spiritual traditions and philosophies propose that true self-awareness involves moving beyond the ego—the individual sense of self—and embracing a broader, more interconnected consciousness. In practices such as meditation, individuals often report experiences of “self-transcendence,” where the boundaries between the self and the world blur, leading to a sense of unity and interconnectedness.

This concept challenges the Western notion of the self as an isolated, autonomous entity. Instead, self-transcendence suggests that consciousness may not be bound to the individual mind but part of a larger, collective consciousness. Such experiences raise intriguing questions about the nature of identity and the ultimate purpose of consciousness. If self-transcendence is possible, it suggests that the self may be a temporary construct—useful for navigating the material world but not necessarily the ultimate expression of our conscious potential.

Consciousness as an Ever-Evolving Landscape

The journey of consciousness and self-awareness is one of constant evolution. From the formation of identity in childhood to the complexities of social self-perception, from the development of future projections to the potential for self-transcendence, consciousness is an intricate web of cognitive processes that interweave to create our lived experience. Our understanding of consciousness continues to evolve as science delves deeper into the mechanisms behind self-awareness, memory, and identity.

In closing, the study of consciousness is not just about the mind’s ability to perceive the world; it is about the continual unfolding of identity, the interaction between past, present, and future selves, and the quest for meaning in an ever-changing world. The consciousness that defines our sense of self is both a stabilizing force and a doorway to transformation, inviting us to explore the depths of awareness, the limits of perception, and the boundless potential for self-discovery. This evolving journey of consciousness encourages us to approach our identity with curiosity and openness, ready to redefine the self as we embrace new understandings of who we are and who we can become.

The Illusion of Perception: How the Brain Filters Reality and Constructs Consciousness

In the intricate realm of human experience, the interplay between perception and consciousness has long been a subject of fascination and inquiry. At the heart of this discussion lies an intriguing phenomenon: the brain’s capacity to filter, interpret, and construct reality, often obscuring the objective world in favor of a customized, subjective experience. This section explores the selective and interpretative nature of perception, examining how the brain’s processes shape our understanding of the world, our interactions with others, and our sense of self. Beyond mere sensory input, consciousness emerges as a dynamic, evolving construct, one that is deeply tied to memory, intention, social identity, and even cognitive dissonance, revealing how reality as we know it may be more of an illusion than an objective truth.

The Brain as a Filter: Selective Perception and Cognitive Shortcuts

Human consciousness is often thought of as an accurate mirror of reality, faithfully capturing the external world. However, neuroscientific research has shown that our brain is, in fact, highly selective in what it perceives. Given the sheer volume of sensory information bombarding us at any moment, the brain must prioritize certain stimuli while ignoring others. This process of selective perception relies on filters shaped by past experiences, emotional states, and cognitive biases, which guide our attention and influence what we perceive as important.

For instance, studies have shown that attention can be directed by emotional relevance. A person who feels anxious, for example, may become hyper-aware of potential threats in their environment, even if those threats are minimal or imagined. This selective perception extends to everyday interactions and social situations, where we may overemphasize certain aspects of behavior or conversation based on our mood or expectations. This illustrates how our brains filter reality in ways that can reinforce pre-existing beliefs and emotional states, often blurring the line between objective perception and subjective interpretation.

Pattern Recognition and Cognitive Biases

The brain’s tendency to filter sensory information is also influenced by its reliance on pattern recognition and cognitive shortcuts, known as heuristics. These mental shortcuts allow us to process information quickly and efficiently but often at the expense of accuracy. The brain’s pattern-recognition ability enables it to draw connections between disparate pieces of information, allowing us to predict and navigate our environment with ease. However, this same mechanism can lead to cognitive biases, where we see patterns or relationships that may not exist.

Confirmation bias, for example, causes us to seek out information that aligns with our pre-existing beliefs, while ignoring evidence to the contrary. Similarly, the “availability heuristic” means we are more likely to recall recent or emotionally charged experiences, which then influence our perception and decision-making. These cognitive biases shape our understanding of reality, reinforcing beliefs that may be flawed or incomplete. Thus, while the brain’s filters and shortcuts are essential for processing information, they often lead to a distorted version of reality that reflects more of our inner psychology than the objective world.

Constructing Reality Through Memory and Anticipation

Beyond the brain’s role in filtering perception, memory and anticipation further contribute to the construction of reality. Memory is not a static record of past events but a dynamic and often malleable process that reshapes itself each time it is recalled. This means that our memories are colored by our current emotions, beliefs, and even social influences, creating a version of the past that serves our present understanding of ourselves and the world.

Anticipation, on the other hand, is the brain’s mechanism for projecting future possibilities based on past experiences and current desires. This forward-looking aspect of consciousness shapes how we interpret the present moment. For example, an individual anticipating a rewarding experience may interpret neutral events more positively, while someone expecting disappointment may view even positive situations with suspicion. Through the combined influence of memory and anticipation, the brain weaves a continuous narrative that guides our understanding of the present, often merging past, present, and future into a cohesive, though sometimes illusory, sense of reality.

The Role of Self-Concept in Perception and Interaction

An often-overlooked aspect of perception is the influence of self-concept, the mental image we hold of ourselves, which can significantly alter how we interpret and interact with the world. Our self-concept is a combination of traits, beliefs, and experiences that form the foundation of our identity. This internal construct not only shapes how we see ourselves but also colors our perceptions of others and our environment.

For instance, an individual with a strong sense of self-confidence may perceive challenges as opportunities, while someone with self-doubt might interpret the same situations as threats. This self-concept acts as a lens through which we interpret social cues, body language, and even verbal communication. Psychologists suggest that this self-focused filtering helps maintain a stable sense of identity by confirming beliefs and narratives about ourselves, even if those beliefs are limiting or inaccurate. The process by which the self reinforces its own perception of reality can create a feedback loop, where our interactions with others are shaped by—and, in turn, reinforce—our self-concept, perpetuating our subjective experience of the world.

Social Reality and the Power of Collective Belief

While individual perception shapes personal experience, humans are also influenced by a “social reality,” a shared construct created by collective beliefs and social norms. This phenomenon is evident in cultural and societal standards, where certain behaviors, values, and even perceptions are deemed acceptable or true based on shared beliefs. Language itself acts as a medium for this social reality, encoding cultural concepts and norms that influence how we interpret and interact with the world.

For example, certain cultures have words for emotions that others lack, such as the Japanese term “amae,” which describes the sense of pleasurable dependence on another person. Such culturally specific terms illustrate how language and shared belief systems shape not only how we communicate but also how we experience emotions and perceive relationships. The social construction of reality emphasizes that our consciousness is not an isolated phenomenon but a deeply interconnected experience, influenced by the values, norms, and beliefs of the communities we belong to.

Dissolving the Illusion: Self-Reflection and Mindfulness

Given the subjective nature of perception and the illusion of a single, objective reality, the practice of self-reflection and mindfulness offers a way to transcend these mental filters. Mindfulness encourages us to observe our thoughts, emotions, and perceptions without judgment, creating a space for awareness beyond automatic reactions and biases. Through mindfulness, we can begin to see our own cognitive processes at work—the filters we apply, the patterns we seek, and the narratives we construct.

Self-reflection, similarly, invites us to examine our beliefs and biases, questioning the assumptions that shape our perception of reality. By becoming aware of these mental constructs, individuals can begin to deconstruct them, gaining insight into how their perceptions have been shaped by past experiences, social conditioning, and cognitive biases. This process of self-inquiry can lead to a greater sense of autonomy, as individuals learn to distinguish between the subjective lenses of their perception and the objective events that inspire them.

Consciousness Beyond Perception: The Quest for Objectivity

Ultimately, the study of consciousness and perception reveals that much of our reality is a subjective construct shaped by both individual psychology and collective belief systems. However, there is also an underlying human desire to move beyond these subjective interpretations toward a deeper, more objective understanding of reality. This quest for objectivity has driven philosophical inquiry and scientific exploration for centuries, as humans seek to understand the world as it truly is, beyond the limitations of personal perception.

One approach to this quest is the scientific method, which emphasizes observation, experimentation, and evidence as a way to uncover truths that transcend individual biases. By developing tools and methods that extend beyond human perception, such as telescopes, microscopes, and statistical analyses, science allows us to access aspects of reality that would otherwise remain hidden. These tools offer glimpses of a reality that exists beyond our subjective filters, reminding us that while consciousness is a powerful tool for interpreting the world, it is also limited by the very structures that enable it.

Conclusion: The Art of Embracing Subjectivity and Seeking Truth

In conclusion, consciousness and perception are complex, interwoven constructs that shape our understanding of reality in profound ways. While our brain’s filters, biases, and social conditioning often distort objective truth, they also provide us with a unique lens through which to experience and interpret the world. The journey of self-awareness and understanding involves balancing the recognition of these subjective influences with a pursuit of truth that transcends them. Embracing our subjectivity while seeking to understand and transcend its limitations may be the essence of human consciousness—a delicate dance between illusion and insight, where each step brings us closer to a more expansive understanding of reality and ourselves.

Unseen Architects of Perception: The Role of Memory, Emotions, and Cultural Context in Shaping Reality

Human perception is a profound, ongoing process that goes beyond simple sensory input to include complex influences such as memory, emotions, and cultural context. This section delves into the often-hidden forces that shape our subjective experiences, backed by real-world examples and research evidence. By understanding these unseen architects of perception, we gain insight into how our memories, emotions, and cultural backgrounds intricately sculpt what we perceive as "reality."

Memory as a Builder and Shaper of Perception

Memory is a dynamic, reconstructive process that not only recalls past events but also actively influences how we perceive the present and anticipate the future. Far from a static record, memory shapes perception by adding layers of past experiences, knowledge, and expectations. This phenomenon is best illustrated through research on "false memories," where people recall events that never happened, showing how malleable our memories—and therefore our perceptions—can be.

One famous study by psychologist Elizabeth Loftus demonstrated this with the "lost in the mall" experiment. Participants were falsely informed that they had been lost in a shopping mall as a child. Remarkably, many participants "remembered" this event vividly, complete with details that had never occurred. This experiment highlights how memory can create entire perceptions that feel real, despite being fictional. Thus, memory acts not just as a storehouse of experiences but as a creative force that can alter our current perceptions based on what we believe happened in the past.

The Emotional Lens: How Feelings Shape What We See

Emotions add a potent and often subconscious filter to our perception of reality. Neuroscientists have shown that emotions can alter the brain's interpretation of sensory input, focusing attention on certain details while overlooking others. This is why someone experiencing fear might see neutral facial expressions as hostile, or why a person in love might view the world in a brighter, more positive light. Emotions, by changing what we focus on and remember, subtly yet powerfully shape our experience of reality.

Consider the case of "emotional blindness," a phenomenon where strong emotions momentarily impair one's ability to perceive the surrounding environment. For example, after receiving sudden, traumatic news, many people report a "blurred" or "unreal" sensation, where their surroundings seem hazy or dreamlike. In such moments, the emotional impact reshapes perception, underscoring how deeply our feelings influence how we interpret the world. Emotions, therefore, are not mere reactions but active participants in constructing our subjective reality.

Cultural Context as a Framework of Reality

Cultural background plays a major role in shaping perception, often dictating what we notice, value, and interpret in any given context. Culture acts as an invisible framework within which individuals interpret their experiences, often unconsciously shaping their assumptions and responses. This influence is particularly evident in visual perception, where culture impacts even the way we interpret simple images.

For example, a study comparing East Asian and Western participants found distinct differences in how people from these cultural backgrounds view scenes. While Western participants tended to focus on prominent objects in the foreground, East Asian participants paid more attention to the background and context. This difference in perception reflects the cultural value placed on individualism versus collectivism: Western cultures often emphasize the individual, while East Asian cultures emphasize harmony within a collective context. Such findings illustrate how cultural conditioning shapes even our most basic perceptual habits, subtly influencing what we "see" and prioritize in everyday life.

Social Influence and the "Reality" of Group Consensus

Social context can also drastically alter perception, often through a phenomenon known as "groupthink" or social conformity. This influence is well-documented in classic experiments like Solomon Asch’s conformity study, which showed how individuals might change their perceptions to align with a group consensus, even when the consensus is clearly incorrect.

In the Asch experiment, participants were shown a series of lines and asked to match a line to one of equal length. While the task seemed straightforward, when the majority of the group intentionally chose the wrong line, many participants conformed to the group’s answer, doubting their own senses. This experiment reveals how social pressure can override individual perception, causing people to align their experience of reality with the group’s, despite clear contradictions.

Such social influences are not limited to controlled experiments. Real-life scenarios, such as political rallies or social media trends, often demonstrate the power of group consensus to shape individual beliefs and perceptions. For instance, during times of intense political division, individuals might perceive facts differently based on the prevailing narratives within their social circles. In this way, group dynamics and social influences can fundamentally reshape one's understanding of reality, showing that our perception is never entirely our own.

The Power of Expectations: How Mindset Influences Perception

Expectations and beliefs are powerful forces that shape what we see and experience. Known as the "placebo effect" in medicine, this concept extends to everyday life, where what we expect often becomes what we perceive. A classic example comes from psychology experiments in which participants are given a placebo (a non-active substance) but told it is a powerful stimulant or sedative. Remarkably, participants report experiencing effects like increased energy or drowsiness, solely because they believed the pill would have these effects.

Outside of medicine, expectation-driven perception can be seen in self-fulfilling prophecies. If someone believes they will perform poorly on a task, this negative expectation may impair their performance, creating a self-fulfilling cycle where expectations influence outcomes. Similarly, positive expectations—such as "beginner's luck"—can sometimes lead individuals to excel temporarily, solely because they believe they are likely to succeed. These examples illustrate how expectation is not just a passive mindset but an active force that shapes our interactions with the world.

Cognitive Dissonance and the Adaptation of Belief

Cognitive dissonance occurs when a person holds contradictory beliefs or experiences, prompting discomfort that often leads them to alter one of the beliefs to restore mental harmony. This process subtly reshapes perceptions as individuals adapt their understanding of reality to align with their beliefs or actions. A classic example of cognitive dissonance can be seen in the context of smoking, where smokers may rationalize the habit despite health warnings by downplaying the risks or emphasizing perceived benefits.

Research has shown that when individuals engage in behaviors that contradict their self-image or values, they often unconsciously reshape their beliefs to justify the behavior. This mental adaptation shows how perception is not static but a flexible construct, bending to align with the individual's beliefs, actions, and desired self-concept.

Sensory Deprivation and the Brain’s Creation of Reality

In situations of sensory deprivation, the brain demonstrates its powerful capacity to construct reality, even in the absence of external input. Studies on sensory deprivation have revealed that, when deprived of sensory input, people often experience vivid hallucinations as the brain attempts to fill the void. In one study, participants placed in a dark, soundproof room for extended periods began to see patterns, lights, and even complex images that were not present, created purely by the mind.

Such experiments underscore the brain's role in generating perception. Far from passively receiving information, the brain actively constructs experiences, suggesting that reality is partly a mental creation that the brain sustains even without direct stimuli. This phenomenon also highlights how adaptable our perception is—where the brain will create its own "reality" to maintain continuity, demonstrating the extent to which reality is an internal, rather than external, phenomenon.

The Constructive Nature of Language and Thought

Language also shapes perception by defining the categories and concepts we use to interpret the world. Linguistic relativity, or the "Sapir-Whorf hypothesis," suggests that the language we speak influences how we think and perceive. In an illustrative study, researchers found that speakers of Russian, who have different words for light blue and dark blue, were faster at distinguishing between shades of blue than English speakers, who use a single word for both. This linguistic difference shows that language shapes our perceptions, sometimes enhancing or limiting what we notice.

Moreover, language guides not just perception but thought patterns. Phrases like "seeing the glass half-full" or "wearing rose-colored glasses" reflect how language encapsulates and reinforces ways of thinking, framing our experiences in terms of culturally embedded concepts. Thus, language both reflects and shapes reality, coloring our perceptions in ways we might not consciously realize.

Conclusion: The Multifaceted Nature of Reality

In summary, perception is far from a straightforward reflection of the external world. Instead, it is an intricate, adaptive process shaped by memory, emotions, cultural background, social influence, expectations, cognitive dissonance, sensory processing, and language. Each of these factors acts as an unseen architect, sculpting our reality in unique ways that reflect both our internal landscape and the cultural environment in which we live.

Recognizing these influences invites a deeper awareness of the subjective nature of perception, reminding us that reality as we know it is a dynamic construct—one that blends the physical world with layers of psychological, emotional, and cultural meaning. By understanding these forces, we can approach our perceptions with greater insight, humility, and openness, acknowledging that what we "see" is often a reflection of who we are, as much as it is a reflection of the world itself.

Consciousness of Suffering, Sin, and Redemption: A Spiritual Journey Towards Transformation

The journey of spiritual consciousness is profoundly explored in the scriptures, offering insight into suffering, the awareness of sin, and the path to redemption. Verses such as 1 Peter 2:19, Hebrews 10:2, and Romans 3:20 offer a layered view of consciousness—a consciousness shaped by enduring suffering, recognizing sin, and ultimately being transformed. Through these passages, we gain an understanding of how suffering and the awareness of sin play integral roles in our spiritual growth and relationship with God.

Consciousness of God in the Midst of Suffering: 1 Peter 2:19

“For if anyone endures the pain of unjust suffering because he is conscious of God, this is to be commended” (1 Peter 2:19, BSB).

1 Peter 2:19 speaks to the spiritual honor that comes from enduring unjust suffering out of consciousness of God. This verse emphasizes that when we suffer without cause or face challenges we did not deserve, bearing this pain with an awareness of God’s presence brings spiritual value. This consciousness of God transforms suffering into an act of worship, as the individual’s focus is not on retaliation or self-pity, but rather on trust and patience in God.

Enduring suffering with a God-conscious mind reflects the life of Christ, who himself endured immense unjust suffering. It teaches believers to see their trials not as meaningless afflictions but as opportunities to express faith. By focusing on God during these times, they find purpose in their suffering, developing perseverance, humility, and resilience. This consciousness of God in suffering is, therefore, not merely a passive endurance but an active participation in divine transformation.

Awareness of Sin and the Need for Redemption: Romans 3:20

"Therefore no one will be declared righteous in God's sight by the works of the law; rather, through the law we become conscious of our sin" (Romans 3:20, NIV).

Romans 3:20 shifts the focus from suffering to sin, revealing that the law functions not as a pathway to righteousness but as a mirror reflecting humanity’s sinfulness. The awareness of sin—becoming conscious of where we fall short—is critical for growth, as it fosters humility and the realization of our need for God’s grace. This consciousness of sin is not intended to lead us to despair, but to drive us toward repentance and reliance on God’s mercy.

In this light, the law serves as a teacher, revealing areas of weakness and the innate tendency to fall short of divine standards. This realization underscores that righteousness cannot be achieved through human effort alone; it requires divine intervention. Therefore, consciousness of sin becomes a foundational step toward salvation, a necessary awareness that guides us to seek forgiveness and transformation. Without this self-awareness, there would be no motivation to grow, repent, or change.

Purging the Consciousness of Sin: Hebrews 10:2

“For then would not sacrifices have ceased to be offered? For worshipers once purged should have had no more consciousness of sins” (Hebrews 10:2, KJ21).

In Hebrews 10:2, the writer refers to the limitations of Old Testament sacrifices, questioning why they continued if they truly cleansed worshipers of the consciousness of sin. This verse brings into focus the temporary nature of sacrifices under the old covenant, which could not provide lasting freedom from sin-consciousness. Instead, these sacrifices served as reminders of sin, a perpetual cycle that underscored humanity’s inability to achieve holiness through ritual alone.

Under the new covenant in Christ, however, believers are offered a deeper, more enduring purging of sin. Through the ultimate sacrifice of Jesus, the aim is not just the forgiveness of sin but the cleansing of guilt and shame. This purging leads to a transformed conscience, where believers no longer live under the shadow of sin but in the light of grace. Thus, Hebrews 10:2 reflects the transition from temporary to permanent redemption, illustrating that true transformation occurs not through ritual but through a heart aligned with God.

Connecting Consciousness of Suffering, Sin, and Redemption

These verses, when connected, provide a holistic view of spiritual consciousness—a process in which awareness of suffering and sin leads to redemption and transformation. The consciousness of God amid suffering, as outlined in 1 Peter 2:19, teaches humility and patience, cultivating virtues that draw us closer to Christ. This experience of unjust suffering often sharpens our awareness of human frailty and the limitations of earthly justice, driving us to seek divine strength and comfort.

Romans 3:20, by highlighting the law’s role in making us conscious of sin, adds depth to this understanding. It shows that suffering is not merely external but internal; sin creates a form of suffering as well, a struggle within our own souls. The law’s revelation of sin exposes our need for redemption and our inability to attain righteousness on our own. This realization fosters dependence on God’s grace, setting the stage for genuine transformation.

Hebrews 10:2 then completes this journey by presenting the solution to this cycle of suffering and sin-consciousness—the final cleansing available through Christ. Through his sacrifice, believers are not only forgiven but are also freed from the lingering guilt and shame of past transgressions. This purging of the conscience enables a new life, one lived not under the weight of sin but in the freedom of grace and spiritual renewal.

Real-World Examples of Spiritual Consciousness in Action

In everyday life, these principles play out in remarkable ways. Consider individuals who face unjust suffering, such as those who endure discrimination, wrongful accusations, or social injustices. Some of these individuals, driven by a consciousness of God, choose not to retaliate but instead respond with patience, forgiveness, and hope. Their actions often inspire others and stand as testimonies to the power of faith under trial. This response transforms their suffering into a witness of God’s love, reflecting the essence of 1 Peter 2:19.

Similarly, the awareness of sin as described in Romans 3:20 is visible in people who, upon recognizing their flaws, actively seek to change. For example, those overcoming addiction often report a powerful awakening to the consequences of their actions—a consciousness of sin that propels them toward recovery. This awareness creates the humility needed to ask for help and make amends, underscoring the transformative power of acknowledging one’s weaknesses.

Finally, Hebrews 10:2’s notion of purging the consciousness of sin can be seen in people who have found redemption through faith, emerging from cycles of guilt and shame. For instance, individuals who were once burdened by past mistakes often describe feeling a profound sense of freedom after embracing forgiveness. This release allows them to rebuild their lives, shifting from a state of constant self-reproach to one of gratitude and purpose. In this way, their transformation mirrors the promise of a purged conscience, embodying the freedom that comes with redemption.

Conclusion: The Journey from Consciousness to Transformation

The journey of spiritual consciousness, as illustrated in 1 Peter 2:19, Romans 3:20, and Hebrews 10:2, reveals a path of growth through suffering, awareness of sin, and the redemptive power of Christ. Suffering endured with a consciousness of God leads to deeper faith and resilience, while the law’s exposure of sin reveals our need for divine mercy. Through Christ’s sacrifice, believers are offered freedom from the shame and guilt of sin, allowing them to live in the fullness of God’s grace.

In embracing this journey, we come to understand that spiritual consciousness is more than mere awareness; it is a transformative process that reshapes us from within. Through trials and self-awareness, we are drawn closer to God, shedding layers of pride, guilt, and self-reliance. Ultimately, this process moves us toward a life that reflects the compassion, humility, and freedom found in Christ, as we are continually transformed by the renewal of our minds and hearts.

#Consciousness#Perception#Sensory Input#Information Processing#Reduction#Layers of Consciousness#Material Reality#Behavioral Expressions#Imaginative Realm#Linguistic Realm#Understanding#Harmony#Science#Philosophy#Complexity#Human Experience#Observer's Dilemma#Order#Novelty#Predictability#Control#Simplification#Nuance#Engagement#Spiritual Consciousness#Suffering#Sin#Redemption#Transformation#Spiritual Growth

0 notes

Text

Ask A Genius 1019: The Dr. Claus Volko Session

Rick Rosner, American Comedy Writer, www.rickrosner.org Scott Douglas Jacobsen, Independent Journalist, www.in-sightpublishing.com Scott Douglas Jacobsen: As we did previously, I have a question from someone, Dr. Claus Volko. His question is framed as a statement. Dr. Claus Volko says, “I would like to learn about Rick’s ‘theory of everything’ if possible.” He has no specific questions. Rick…

#closed system#information processing#information system#Informational Cosmology#interference pattern#quantum mechanics#Rick&039;s theory of everything#theory of information#universe as information

0 notes

Text

Still not over the head of cardiology, who said she wouldn't formally diagnose me with dysautonomia because she didn't want me to think of myself as disabled.

As if good vibes and a can-do attitude can stabalize autonomic dysfunction.

#chronic health tag#ableism in our medical system???#it's more likely than you think#I still remember having to inform the ER doctor that the reason MCAS wasn't in my file#was because the head of allergy for the hospital he worked at#'didn't believe in it'#this was one week into the pandemic#and this man touched his face out of exasperation#and muttered something that might have been 'dense mother fucker' under his breathe#anyway#there should be a screening process for people who want to go into medicine#if you think the only disability is a bad attitude#you should be jettisoned from your course and directly into the sun

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

*peering down at my own genetic sequence* uh-huh uh-huh bold choice bold fucking choices my friend

#and i don't have veto power over any of this? that Cannot be correct information#there must surely exist an Appeal Process or#*me discovering how any of reality's systems function* this can not POSSIBLY be how this system functions#*scribbling furiously filling an entire college ruled notebook DOUBLE-SIDED with a list of design flaws to present to the court*

9K notes

·

View notes

Note

Sooo besides espilver (and I'm assuming sonucks), what sonic ships do you like?

I'm not that big of a shipper, tbh! But you're right, I find sonknux very fun in a "theyre both so stupid" kinda way. I have some doodles about them loaded up in my drafts, so you'll be seein' that sometime soon!

Other than that, I've been REALLY loving sonighty lately. Something about the childhood friends that reconnect years later trope ruins be every time i see it. They have such an underrated dynamic imo :')

#roonies doodles#roonie answers#sonic the hedgehog#mighty the armadillo#sonighty#yall they both love adventuring. think of all the hikes they could go on#holding hands as they cross a river. stargazing in a canyon. kissing on a mountain top. AUGH#me n my sister have lowkey been cooking up an au including all three of those ships. it has fankids. it has drama. tails is miserable.#i love it a lot i might share it if theres interest but also probably even if there isnt interest#also sidebar but i love whispangle too. because i am a person with eyes and a brain with which to process information#those two are canon as far as im concerned

617 notes

·

View notes

Text

It really dawned on me watching episode 17, just how important this sequence of events is to Kabru and Laios' relationship, and how. Well. That's for a different post. I want to keep this one free of spoilers. (Certified Safe For Anime Only™)(There are spoilers for episode 17, tho. Obviously.)

Kabru's main concern has been, at least in part, revealed. He wants to figure out if Laios is capable of defeating the dungeon, and, if so, if Laios can be trusted with the power that might confer. The answer to his first question is simple. Yes. If anyone can defeat the dungeon, it's Laios.

The second question is where things get interesting. Can Laios be trusted with power?

In the aftermath of Laios' first fight with Toshiro, Kabru learns that while Laios has no particular respect for the law or conventional wisdom, he does have the humility to consider that his judgment might be flawed if he encounters conflict with someone he respects.

That is the face of a man taking notes, and I think he's making a cautious mark in Laios' favor. Laios doesn't really understand Toshiro's opinion, but he's listening.

Then, in the fight with the Falin-Dragon chimera, Kabru voices dissent—disgust, even—with Laios and Marcille's priorities.

You can practically see the Dragon Age style approval rating drop. Kabru disapproves. Minus fifteen hearts. If it had ended like this, I think Kabru would have lost all interest in Laios. Someone who would sacrifice a dozen lives out of sentiment can't be trusted.

Laios' response, and the way it builds on Kabru's earlier observation, is crucial.

He listened. And even better, he didn't listen blindly. He applied critical thought to Kabru's argument. What Kabru hears from him isn't just "I'm sorry, you were right," but also, "I understand and respect your position and priorities, and here's a very good argument for why killing what I still consider to be my sister is not in our best interest."

He processed Kabru's criticism and came to his own conclusions, and he did it fast. Not only that, but he's right. Kabru hadn't considered the potential consequences of killing the chimera.

Laios proved in this one exchange that he 1) isn't blinded by either his pride or his prejudice, 2) has the strength of character to not just fall back and surrender to someone else's judgment when he's uncertain, and 3) is smart enough to tactically outhink Kabru.

This is why Kabru is so invested in Laios liking him that he forces himself to eat the harpy omlette. This is why Kabru takes Laios' hand and makes sure he knows he wants to see him again. He doesn't understand Laios, and he still has strong reservations about him. Laios' interest in monsters scares him. But Laios has proved to Kabru that he might be capable of being the person Kabru needs him to be.

Top Ten Pictures Of The Moment He Won You Over (Taken Just Before Disaster).

#dungeon meshi#dunmeshi spoilers#kabru of utaya#laios touden#we get a LOT of information to process in episode 17#but Kabru's motivations as I present them here are supported by both his statements in the sea serpent episode and his thoughts in this one#I don't want the post to get any longer so I'm just gonna trust you all to either trust me on that or go back yourselves to verify#delicious in dungeon#labru#sort of

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

1920s Obi-Wan x Satine x Cody

#cobitine#codywan#obitine#obi wan and cody were war buddies in the great war#codys dad jango did some goofing during the war#meanwhile satines unnamed husband dies to spanish flu after the war#cody is informed that theres an issue of inheritance with satines land because jango somehow convinced someone to make him an heir#jango however dies in the war#cody and obi wan go to satines estate to settle the dispute#they all fall in love in the process#cody and satine wed to settle the dispute#and obi wan is their mutual boyfriend#they go out to speak easys and dance#obi wan kenobi#commander cody#satine kryze#im obsessed with them#20s cobitine#star wars#star wars fanart#my art#fanart#digital art#historical au

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

been thinking recently about the control of information in kotlc. it's only mentioned in passing, but the elves ban books (p. 287). several classes--advanced history, on the other intelligent species--are restricted to the elite levels only. lumenaria has a secret database of records. the oldest records are largely illegible to the modern population w/o significant time/effort/resources. councillors keep memories in caches and erase them from their minds. we're starting to really get into the flaws of caches, but the rest has been like this subtle, lurking menace beneath the whole story. but it's simultaneously overt in how desperately Sophie is always searching for answers. and yes, some of that is because the Neverseen are actively working against her, but she's just as often running up against information control by the council and black swan. about pyrokinetics, the plague, vespera, nightfall, stellarlune, elysian. it's not the story's only message, but it feels like we're building to an explicit condemnation of censorship and revisionism. the story's starting to say louder and louder you cannot decide who is allowed to know what, you are not arbitrator of what's right, of what's important, of what's dangerous. and trying does nothing but harm the people you claim to protect. kotlc is, among other things, a story against information control. and i'm just really curious to see where it all goes.

#kotlc#a few weeks ago i saw the banned book line and it like. finally processed after 8 years#i didn't think of it much when i first read the series on account of there's so much going on#but kotlc is very much a story about controlling information and the damages#the message is very obvious with the caches recently ofc. but it's also present in so many other places#and i have not stopped thinking about that banned books line since#partly out of disbelief i never processed it fully before. so feel free to hang me out to dry for missing it#on account of its so obvious#but anyways#having Thoughts

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

today I did not pay any attention at a lecture and still asked a question that people found "very insightful" and that's because I spent my academic career having to work hard on my bullshitting instead of getting a plagiarism machine to do it for me

#dottie rambles#dottie academes#it's about processing information and critical thinking!#that's why we make you do assignments!

798 notes

·

View notes

Text

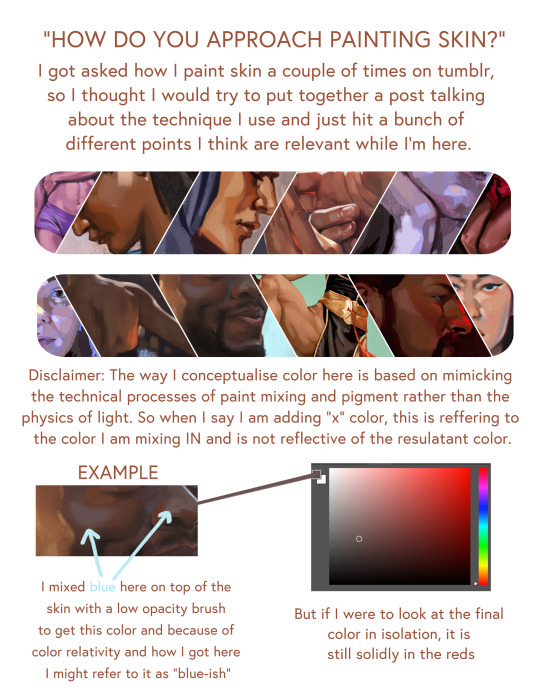

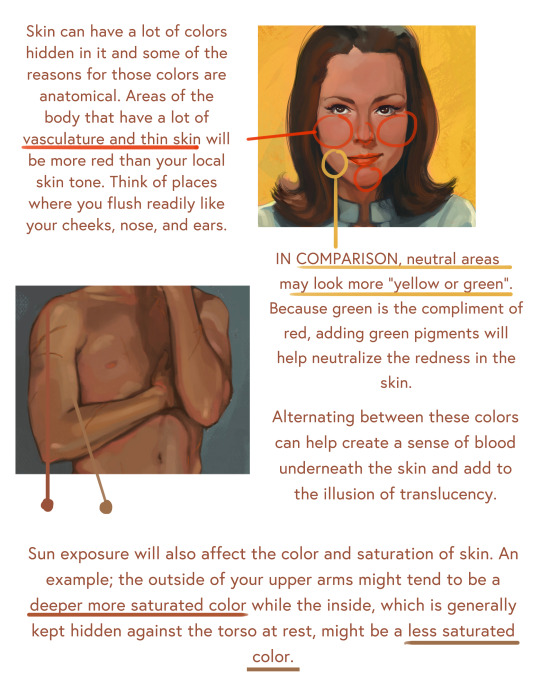

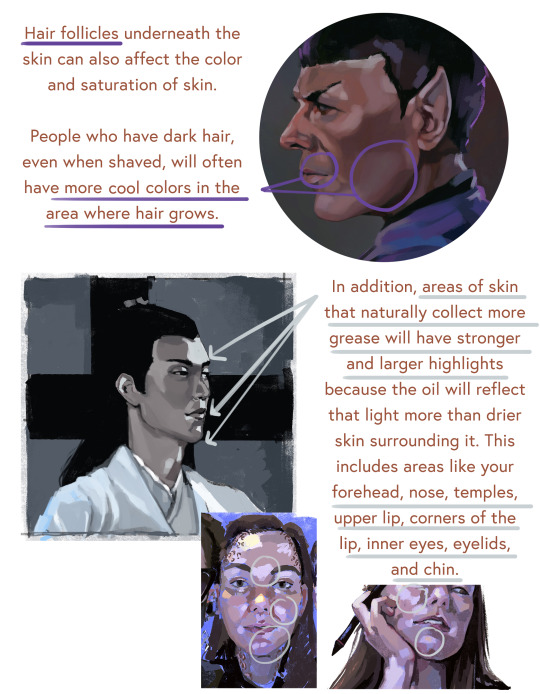

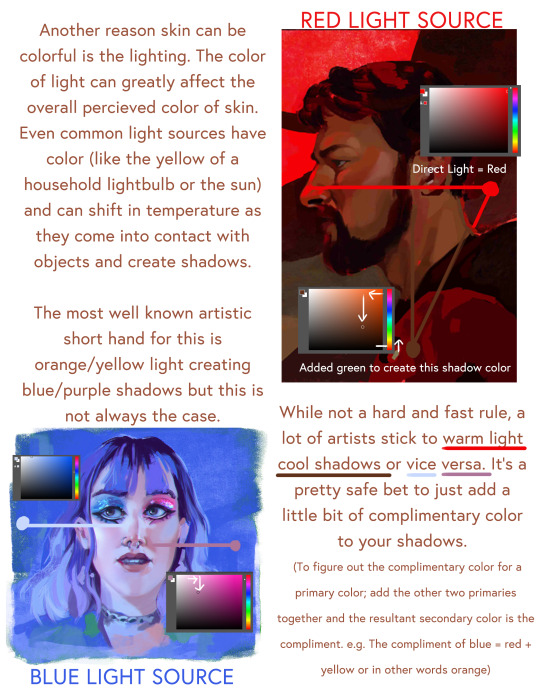

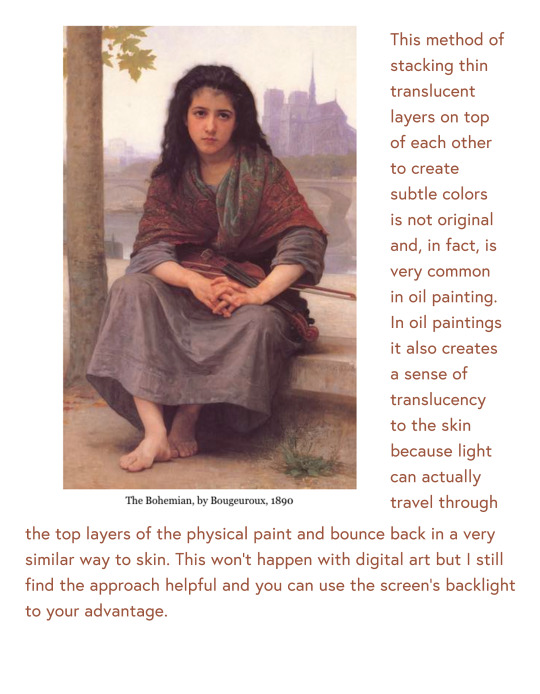

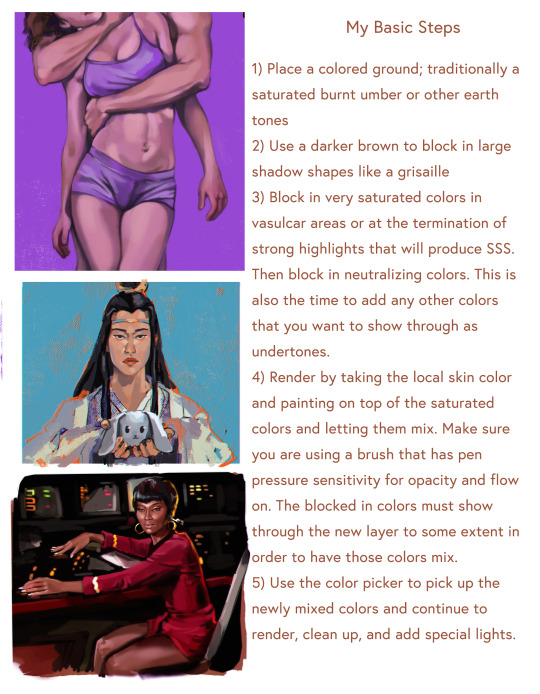

Artist: RaeGunBlast

#raegunblast#art#2d#painting#artists on tumblr#art help#art reference#art resources#art information#art process#how to paint skin#art tutorial#artist#art practice

3K notes

·

View notes