#hebrew university 2006

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

masterlist of introductory materials for the hebrew bible and new testament

below are resources intended for beginners. these would be assigned to upper level undergraduate theology courses or first year theological master degree courses. they represent academic/ "the Academy's" mode of introducing material. bold are titles most frequently used in syllabi.

these are just general introductions, done well but limited by scope. they attend to the testaments as a whole, not their individual books. i recommend, after getting introduced, that your self-study explore particular books, and then, particular hermeneutics: womanist theology, feminist, mujerista, postcolonial, queer, liberation, etc.

as always i recommend reading the texts themselves: an nrsvu(e) translation is expected in academic theology, and this one is a great annotated version.

sefaria is also useful—a jps translation that allows you to see alternative translations for each word

hebrew bible

Collins, John J. Introduction to the Hebrew Bible : And Deutero-canonical Books. Third ed. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2018.

Coogan, Michael David, and Chapman, Cynthia R. The Old Testament : A Historical and Literary Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Fourth ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Brueggemann, Walter., and Linafelt, Tod. An Introduction to the Old Testament : The Canon and Christian Imagination. Second ed. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2012.

Gottwald, Norman K. The Hebrew Bible : A Socio-literary Introduction. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985.

Hasel, Gerhard F. Old Testament Theology: Basic Issues in the Current Debate. 4th ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1991.

Butterfield, Robert A., and Westhelle, Vítor. Making Sense of the Hebrew Bible. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 2016.

new testament

Allison GT. Fortress Commentary on the Bible. The New Testament. (Aymer MP (editor), Fortress Press; 2014.

Holladay CR. Introduction to the New Testament : Reference Edition. Baylor University Press; 2017.

Green, Joel B. 2010. Hearing the New Testament : Strategies for Interpretation. 2nd ed.. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co.

Powell, Mark Allan. 2018. Introducing the New Testament : a Historical, Literary, and Theological Survey. Second edition.. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic.

Carter, Warren. 2006. The Roman Empire and the New Testament : an Essential Guide. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

Smith, Mitzi J. 2018. Toward Decentering the New Testament : a Reintroduction. Edited by Yung Suk Kim. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books.

Ehrman, Bart D. A Brief Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Barton, Stephen C., ed. The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Bockmuehl, Markus, and Donald A. Hagner, eds. The Written Gospel. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Perkins, Pheme. Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007.

Stanton, Graham. The Gospels and Jesus. 2d ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

439 notes

·

View notes

Text

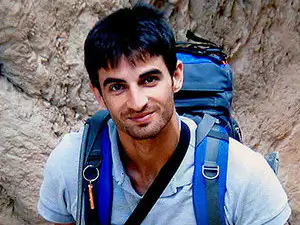

THURSDAY HERO: Roi Klein

Recently researchers at Hebrew University conducted an extensive survey of young Israelis, asking the question, “Who embodies heroism to you?”

Over and over, they heard the same name: Roi Klein.

Roi was born in Raanana, Israel in 1974, the son of two Holocaust survivors. Growing up, Roi was known as an exceptionally kind and thoughtful child who was devoted to daily Torah study.

Like every Israeli, he was drafted into the IDF at age 18. He served in the elite counter-terrorism unit of the Golani Brigade. Roi became an officer, and was the Deputy Commander of the 51st Brigade at the time of the Second Lebanon War in 2006.

During the Battle of Bint Jbeil, Roi and his men were ambushed by Hezbollah terrorists. Roi was treating one of his wounded men, when a terrorist threw a grenade at the group.

Roi immediately threw his body on the grenade to save his men.

As the grenade exploded, mortally wounding him, Roi shouted out “Shema Yisrael” – the essential prayer of Judaism: “The Lord is our God, the Lord is one.” Traditionally, this is the last prayer a Jew says before death.

After the Shma, Roi reported his own death over the radio: “Klein is dead, Klein is dead.” He then succumbed to his wounds, leaving behind his wife Sara and two young children.

Roi was buried the next day, on his 31st birthday.

May his memory always be for a blessing.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

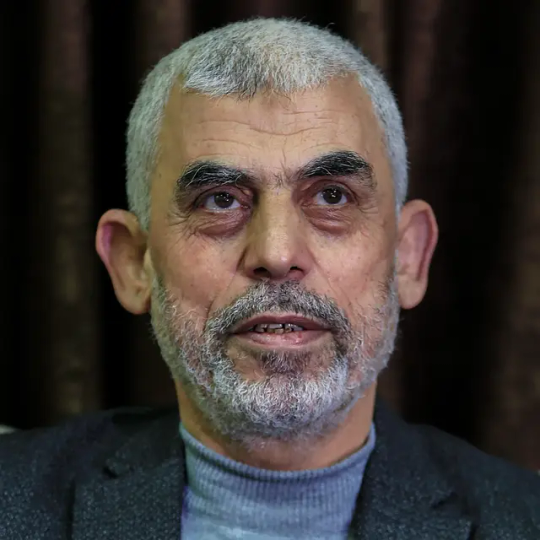

Yahya Sinwar

Hamas leader who plotted the 7 October attack on Israel that triggered war in the Middle East

Yahya Sinwar, the Hamas leader who has been killed by an Israeli patrol in the Gaza Strip at the age of 61, was the principal architect of the attack on Israel on 7 October 2023 that killed 1,200 Israelis, kidnapped 251 hostages, and propelled the Middle East into its greatest peril since the 1973 Yom Kippur war.

The overall leader of Hamas after the assassination of Ismail Haniyeh in July 2024, he was its key strategist before and after 7 October, Israel’s most wanted man and the ultimately pivotal Hamas figure during ceasefire negotiations. Though presumed to have been hiding for most of the year within Gaza’s vast tunnel network, he was killed alone in a ruined apartment in Rafah, according to the Israeli military.

Despite repeated vows by Israeli leaders to assassinate him during their devastating retaliation for the 7 October attack, and after what Israel announced was the killing of his close collaborator Mohammed Deif, the head of Hamas’s military wing, in July 2024, Sinwar was the last survivor of the three Hamas leaders against whom the international criminal court’s chief prosecutor, Karim Khan, sought arrest warrants for suspected war crimes.

Sinwar first came to prominence in 1985 when Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, founder of the organisation that would become Hamas in 1987, put him in joint charge of an armed internal enforcement agency known as al-Majd.

He missed direct participation in the momentous Palestinian events of this century’s first decade, including Hamas’s election victory in 2006, the subsequent imposition of an international boycott, and its armed seizure of full control in Gaza in 2007, because he was in jail. In 1989 he received four life sentences for orchestrating the abduction and killing of two Israeli soldiers and the execution of four Palestinians suspected of cooperating with Israel. According to his interrogators, Sinwar admitted without remorse to personally strangling one victim with his bare hands.

By a historical irony, he was among the 1,027 prisoners released in 2011 by Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, to free a kidnapped Israeli soldier, Gilad Shalit. The exchange reinforced Sinwar’s belief that such abductions were needed to release Palestinian prisoners. During his 22-year incarceration he assumed a commanding role among Palestinian inmates and tried at least twice to escape. Jail, he later said, had been turned by militants into “sanctuaries of worship” and “academies”. He learned fluent Hebrew, studied Israeli politics and society, and by his own account became “a specialist in the Jewish people’s history”.

Sinwar was born in Khan Yunis in southern Gaza. His father, Ibrahim, and his mother had been forced to flee Majdal, now Ashkelon, as refugees from the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. He would tell fellow inmates in prison, said one, Esmat Mansour, that he had been heavily influenced by conditions in the impoverished refugee camp, with its daily humiliation of queueing for food. He was four when Israel overcame Egypt in the six-day war of 1967 and took control of the Strip. He attended Khan Yunis senior school for boys and then the Islamic University, graduating in Arabic language. Sinwar was active in student organisations fusing Islamism with Palestinian nationalism after the perceived failures of the secular PLO. He was briefly detained in 1982 and again in 1988 after Israel’s discovery of al-Majd weapons.

An autobiographical novel he completed in prison in 2004, called Thorns and Carnations, describes the protagonist Ahmed sheltering with his family during the 1967 war, only to find their dreams of Palestinian liberation shattered by Israel’s victory; Ahmed becomes an Islamist after a cousin convinces him of the religious concept of the waqf – the God-given Muslim land from the River Jordan to the Mediterranean. Infatuated with a young woman, Ahmed ends the relationship – chaste in accordance with strict Muslim custom – because in “this bitter story” there was “only room for one love”: for Palestine.

Also in 2004, Sinwar had a brain tumour removed by Israeli surgeons, detected by a quick-thinking Israeli prison dentist (and later intelligence officer), Yuval Bitton, who had Sinwar rushed to hospital. Over multiple conversations in jail before and after this life-saving episode, for which Bitton was warmly thanked by Sinwar, he recalled the prisoner telling him: “Now you’re strong, you have 200 atomic warheads. But we’ll see, maybe in another 10 to 20 years you’ll weaken, and I’ll attack.���

After his release, Sinwar was elected to Hamas’ political bureau in 2012 and, in what was seen as a shift towards its militarist tendency, to the faction’s Gaza leadership in 2017, replacing Haniyeh, who subsequently succeeded Khaled Mashal as political bureau chief. Hamas was losing popularity after two wars with Israel, in 2008-09 and 2014, and Gaza’s deep impoverishment by the blockade imposed by Israel (and Egypt) since 2007.

Sinwar seemed at times to adopt a relatively pragmatic approach. No ally of Mashal, he worked to restore relations with Iran that Mashal had ruptured by opposing Syria’s president, Bashar al-Assad, in his repression of a popular revolt. But he did not demur when Mashal published a (for Hamas) innovative 2017 document which, without recognising Israel, or abandoning its aspiration for the whole land, indicated it would meanwhile accept a Palestinian state based on 1967 borders – comprising the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem.

In 2018 Sinwar conspicuously appeared at the Great March of Return, a series of unarmed mass protests at the border barrier. Increasingly organised by Hamas, to the chagrin of some civil activists who had devised them, the protests seemed briefly to offer some alternative to armed insurgency, despite the lethal gunfire against them by Israeli troops. Sinwar even wrote (in Hebrew) to Netanyahu, proposing a long-term truce.

But a turning point came in 2021, when Sinwar and Deif are thought to have begun planning for what became the 7 October attack. By then, the 2020-21 Abraham accords between Israel, the UAE and Bahrain had reversed the Gulf countries’ refusal to recognise Israel unless the Palestinians secured a state. How far this – and the fear in 2023 that Saudi Arabia might imminently follow suit – dominated Sinwar’s thinking is unclear. But in his 7 October speech praising Sinwar and Deif for the attack, Haniyeh excoriated the Arab states for seeking “normalisation” with Israel.

Sinwar reacted defiantly during Ramadan in May 2021 when police raided the al-Aqsa mosque compound in Jerusalem, after clashes in the city between Palestinians and rightwing Israelis. When police did not leave the compound by a Hamas-set deadline, Gaza militants fired 150 rockets, Israel responded with airstrikes, and there was a short but intense 11-day war. Sinwar warned that Hamas, whose rockets had reached deeper into Israel than before, had enacted a “general rehearsal” for what would happen “if Israel tries to harm al-Aqsa again”.

Less conditionally, in December 2022 Sinwar addressed Israel at a Gaza rally: “We will come to you, God willing, in a roaring flood. We will come to you with endless rockets, we will come to you in a limitless flood of soldiers.” Hamas would name the 7 October attack the “al-Aqsa flood”.

So secretive was its planning that Sinwar kept its timing and scale – though apparently not that something was being prepared – from most of the Hamas external leadership. Western intelligence agencies also believe he did not confide his intentions in advance to Iran or its Lebanese proxy, Hezbollah.

According to a June 2024 Wall Street Journal report, Sinwar described the huge Palestinian losses in a wartime message to Hamas leaders in Qatar as “necessary sacrifices”. In another, on the seizure of women and children as hostages, but without clarifying whether he was referring to Hamas fighters or others who joined the attack and its accompanying atrocities, he said: “Things went out of control … People got caught up in this, and that should not have happened.”

Though he told hostages he met in the tunnels that they would be protected and exchanged in a prisoner release, one 85-year-old peace activist, Yocheved Lifshitz, freed in the week-long ceasefire in November, said she had challenged Sinwar on whether he was “not ashamed to do such a thing to people who have supported peace all these years. He didn’t answer. He was silent.”

In 2011 he married Samar Abu Zamar, and they had three children, the fate of all of whom is unknown. Sinwar’s brother (and close ally), Mohammed, is still being hunted by Israeli forces.

🔔 Yahya Ibrahim Hassan Sinwar, politician, born 29 October 1962; died 16 October 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the Library of Anne Rice (Part 3)

Flynn, Gillian. Gone Girl. New York: Crown Publishing, 2011. Lightly annotated.

Green, John. The Fault in Our Stars. New York: Penguin Books, 2012. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Le Carre, John. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. New York: Bloomsbury, 2005. Ownership signature. Tabbed.

Martin, George R.R. A Dance with Dragons. New York: Bantam Books, 2011. Ownership signature.

Metalious, Grace. Peyton Place. New York: Julian Messner, 1957. Ownership signature.

Sebold, Alice. The Lovely Bones. New York: Back Bay Books, 2007. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Sheldon, Sidney. The Other Side of Midnight. New York: Willam Morrow & Company, Inc., 1973. Ownership signature.

Sienkiewicz, Henryk. Quo Vadis. New York: Hippocrene Books, 2002. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Silva, Daniel. The Kill Artist. New York: Random House, 2000. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Susann, Jacqueline. Once is Not Enough. New York: Willam Morrow & Company, Inc., 1973. Ownership signature. Lightly annotated.

Susann, Jacqueline. Valley of the Dolls. New York: New Market Home Library, 1996. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Turow, Scott. Identical. New York/London: Grand Central Publishing, 2013. Ownership signature.

Turow, Scott. Identical. New York/London: Grand Central Publishing, 2013. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Bowman, Carol. Children's Past Lives. New York: Bantam Books, 1998.

Burpo, Todd with Lynn Vincent. Heaven is for Real. Nashville, Dallas, Mexico City, and Rio de Janeiro: Thomas Nelson, 2010.

Fronkzac, Paul Joseph and Alex Tresniowski. The Foundling. New York: Howard Books, 2017.

Greven, Philip. Spare the Child. New York: Vintage Books, 1990.

Joyce, Stephen H. Suffer the Captive Children. By the Author, 2004.

Malarkey, Kevin & Alex The Boy Who Came Back from Heaven. Carol Stream, Illinois: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 2011.

Mcfarland, Hillary. Quivering Daughter. Dallas, Texas: Darklight Press, 2010.

Postman, Neil. The Disappearance of Childhood. New York: Vintage Books, 1994.

Rafferty, Mary and Eoin O'Sullivan. Suffer the Little Children. New York: Continuum, 1999.

Reilly, Frances. Suffer the Little Children. London: Hachett UK, 2008.

Szalavitz, Maia. Help at Any Cost. New York: Riverhead Books, 2006.

Taylor, Marjorie. Imaginary Companions and the Children Who Create Them. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Tucker, Jim B. Life Before Life. New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 2005.

Woititz, Janet Geringer. Adult Children of Alcoholics. Deerbeach, Florida: Health Communications, Inc., 1983.

Bloom, Harold. The Book of J. New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1990. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Collins, Andrew. From the Ashes of Angels. Rochester, Vermont: Bear & Company, 2001. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Collins, John J. The Scepter and the Star. New York: Doubleday, 1995. Annotated.

Cook, John Granger. The Interpretation of the New Testament in Greco-Roman Paganism. Hendrickson Publish, 2002. Ownership signature.

Ehrman, Bart D. Lost Scriptures. [Oxford]: Oxford University Press, 2003. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Enns, Peter. The Bible Tells Me So... HarperOne, 2014. Ownership signature.

Fox, Everett. The Five Books of Moses. New York: Schocken Books, 1995. Ownership signature. Annotated.

House, H. Wayne. Charts of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1981. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Howard, Thomas. Evangelical is Not Enough. San Francisco: Ignatius, 1984. Ownership signature.

Lockhart, Douglas, Jesus the Heretic. Shaftsbury, Dorset: Element, 1997. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Luckert, Karl W. Egyptian Light and Hebrew Fire. State University of New York Press, 1991.

Parenti, Michael. God and His Demons. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 2010. Ownership signature.

Shaw, Russell. Our Sunday Visitor's Encyclopedia of Catholic Doctrine. Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitors Publishing, 1997. Annotated.

Sparrow, W. Shaw. The Gospels In Art. New York: Frederick A, Stokes Company, 1904. Annotated.

Townsend, Mark. The Gospel of Falling Down. Winchester, UK: O Books, 2007. Inscribed by author.

Valenti, Connie Ann. Stories of Jesus. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2012. Inscribed by author.

Yallop, David A. In God's Name. Toronto: Bantam Books, 1984. Annotated.

Zuesse, Eric. Christ's Ventriloquists. New York: Hyacinth Editions, 2012. Ownership signature. Annotated.

Cayce, Edgar. On Atlantis. New York: Grand Central Publishing, 1968. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Collins, Andrew. Gobekli, Tepe Genesis of the Gods. Rochester, Vermont: Bear & Company, 2014. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Cremo, Michael A. and Richard L. Thompson. Forbidden Archaeology. Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Publishing, 2003. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Eno, Paul F. Faces at the Window. By the Author, 1998. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Fiore, Edith. The Unquiet Dead. New York: Ballantine Books, 1988. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Hoagland, Richard C. and Mike Bar. Dark Mission: The Secret History of Nasa. Feral House, 2007. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Icke, David. The Biggest Secret. David Icke Books, 1999. Ownership Signature.

Joseph, Frank. The Atlantis Encyclopedia. Career Press, 2005. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Knight, Christopher and Alan Butler. Before the Pyramids. London: Watkins Publishing. 1988. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Leshan, Lawrence. A New Science of the Paranormal. Wheaton, Illinois: Theosophical Publishing House, 2009. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Peake, Anthony. The Out-of-Body Experience. Watkins, 2011. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Redfern, Nick. Shapeshifters Woodbury, Minnesota: Llewellyn Publication 2017. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Roberts, Scott Alan. The Secret History of the Reptilians. Pompton, N.J.: New Page Books, 2013. Ownership Signature.

Spence, Lewis. The Occult Sciences in Atlantis. London: The Aquarian Press, 1970. Ownership Signature. Annotated

Temple, Robert with Olivia Temple. The Sphinx Mystery. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2009. Ownership Signature. Lightly Annotated

Thyme, Lauren O. The Lemurian Way. Lakeville, Minnesota: Glade Press, 2012. Ownership Signature.

Wilson, Colin and Rand Flem-Ath. The Atlantis Blueprint. Delta Trade Paperback, 2000. Ownership Signature. Annotated.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you happen to have any good book recommendations for someone looking to read more from Jewish/Israeli voices? By pure happenstance I ended up reading a memoir called “As Figs in Autumn” by Ben Bastomski who is a former IDF soldier (I’m not done with it yet but it’s beautifully written so far!) and I realized that the diversity of my reading is definitely lacking in this department. No pressure for this though! I know thinking of book recs can be taxing sometimes, so I won’t be upset if you don’t want to answer this.

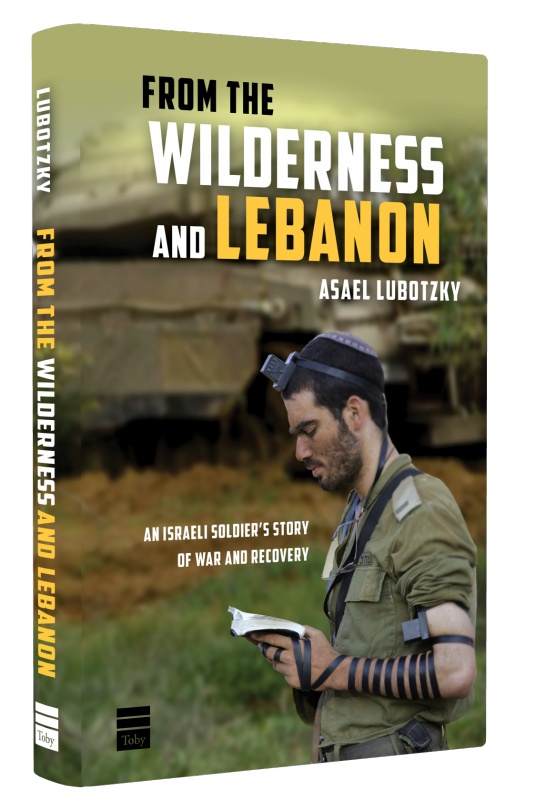

Hi Nonnie!

Awww, thank you for sharing this rec with me and with anyone reading this ask, and even though I haven't read many Israelis' memoirs myself, I will pass on a rec I got from my sister. Full disclosure: the guy who wrote this book was a fellow medicine student when she was at uni.

His name is Asael Lubotzky, and he wrote about his experience of fighting in Gaza, and then in Lebanon in 2006, during the Second Lebanon War. He was injured, and the second part of the book deals with his recovery process, and how it put him on course to study medicine at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

My sister read the book, and said it was powerful. I couldn't bring myself to read it, because one of the battles that he describes there, happened in a place where one of my friends from my army days, Idan Kobi, was killed by Hezbollah terrorists, during the same war. May his memory be a blessing.

Idan was such a special guy, he served as a Paratroopers combat medic, he wanted to travel the world, learn Spanish, and become a doctor. He was the first person I met, who I could say with certainty had a healer's soul. He would have made an amazing doctor, and he was an amazing guy, and it's hard even writing this much about him without being overwhelmed by the loss.

Sorry, I kind of digressed.

Anyway, to not leave you with just one rec... While it's not a proper memoir, there is a book series by Tovia Tenenbom, an Israeli-American writer, who comically shares his experiences, traveling and meeting up with people. Catch the Jew is the book in the series, in which he pretends to be an anti-Israel journalist and travels Israel, and the Palestinian ruled territories. I did read Catch the Jew, I think it's better as a comical take on new antisemitism, than describing regular Israeli experiences, or educating against this new type of Jew hate (Tenenbom assumes you know what's wrong with some of the stuff people said to him when they assumed he was an anti-Israeli non-Jewish journalist), but it's still a fun read. He also has a new book published in Hebrew this year (I haven't had the chance to read it yet), IDK if it's been published in English, but I haven't found any indication of an English title for the book. In Hebrew it's called (roughly) "Charedi and happy" (Charedi is an ultraorthodox Jew), and it covers Tenenbom's experiences of living with the ultraorthodox Jewish community in Jerusalem about a year prior. He was actually born into this community and left it, so I'm sure this book has a special significance for him.

I hope this helps! And maybe someone reading this ask reply would want to add recs in the comments. Have a good day! xoxox

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The mysterious name of God, revealed from the burning bush, a name which separates this God from all other divinities with their many names and simply asserts being, "I am", already presents a challenge to the notion of myth, to which Socrates' attempt to vanquish and transcend myth stands in close analogy.[8] Within the Old Testament, the process which started at the burning bush came to new maturity at the time of the Exile, when the God of Israel, an Israel now deprived of its land and worship, was proclaimed as the God of heaven and earth and described in a simple formula which echoes the words uttered at the burning bush: "I am". This new understanding of God is accompanied by a kind of enlightenment, which finds stark expression in the mockery of gods who are merely the work of human hands (cf. Ps 115). Thus, despite the bitter conflict with those Hellenistic rulers who sought to accommodate it forcibly to the customs and idolatrous cult of the Greeks, biblical faith, in the Hellenistic period, encountered the best of Greek thought at a deep level, resulting in a mutual enrichment evident especially in the later wisdom literature. Today we know that the Greek translation of the Old Testament produced at Alexandria - the Septuagint - is more than a simple (and in that sense really less than satisfactory) translation of the Hebrew text: it is an independent textual witness and a distinct and important step in the history of revelation, one which brought about this encounter in a way that was decisive for the birth and spread of Christianity.[9] A profound encounter of faith and reason is taking place here, an encounter between genuine enlightenment and religion. From the very heart of Christian faith and, at the same time, the heart of Greek thought now joined to faith, Manuel II was able to say: Not to act "with logos" is contrary to God's nature.”

- Pope Benedict XVI, MEETING WITH THE REPRESENTATIVES OF SCIENCE - Aula Magna of the University of Regensburg, 12 September 2006

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ilan Pappe dedicated this book: “To the Palestinian children, killed, wounded, and traumatized by living in the biggest prison on earth.” Ilan Pappé (Hebrew: אילן פפה, pronounced [iˈlan paˈpe]; born 7 November 1954) is an expatriate Israeli historian and political scientist. He is a professor with the College of Social Sciences and International Studies at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, director of the university's European Centre for Palestine Studies, and co-director of the Exeter Centre for Ethno-Political Studies. Pappé was born in Haifa, Israel.[1] Prior to coming to the UK, he was a senior lecturer in political science at the University of Haifa (1984–2007) and chair of the Emil Touma Institute for Palestinian and Israeli Studies in Haifa (2000–2008).[2] He is the author of Ten Myths About Israel (2017), The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (2006), The Modern Middle East (2005), A History of Modern Palestine: One Land, Two Peoples (2003), and Britain and the Arab-Israeli Conflict (1988).[3] He was also a leading member of Hadash,[4] and was a candidate on the party list in the 1996[5] and 1999[6] Knesset elections.

#israel is a terrorist state#stop the genocide#genocide in gaza#Gaza#Palestine#Israeli historian#Israeli Scientist#غزة#فلسطين#educate yourself#تعلم

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In southern Israel, crops are now waiting in the sun, wilting further with every passing minute and shuddering a bit as army vehicles buzz past. The area’s farms have become a vast army staging area, pocked with olive green tents and tanks. Farmhands are nowhere in sight.

On Oct. 7, Hamas rampaged through this region killing more than a thousand people, including foreigners. As many as 7,000 Thai nationals, who make up the largest share of the agricultural workforce, fled Israel after nearly two dozen were abducted and three dozen massacred.

The veritable greenhouse of the nation is now dependent on university volunteers. They have tried to salvage the situation and pick the fruit before it rots, but their efforts have fallen short and the Israeli government has already started to import some items.

Israelis are proud of their technological innovations in agriculture and of their ability to grow in a largely arid region and feed their people. Now it is at the top of the list of sectors that will bear the brunt of a long war with Hamas. Oil and gas, tourism, health care, retail and technology are some of the others.

“Many of my colleagues have left,” said Cindy, a care-giver from the Philippines who asked to be identified only by her first name for safety reasons. “We are going, too, if it gets any worse,” she told me at a market in Jerusalem.

Many airlines have stopped flying to Israel while the government has asked for activities at a gas field to be halted to minimize the risk of a targeted attack. The Israeli shekel has already plummeted to a 14 year low, the central bank has cut the forecast for economic growth this year from 3 percent to 2.3 percent, and prominent industries are facing disruptions.

Israel entered the war with $200 billion in reserves and $14 billion in aid, mainly for military funding, from the United States. And yet experts say the ongoing conflict will cost the Israeli economy billions more and take much longer to recover than it has in the past. Israeli volunteers at home and abroad are chipping in with extra labor and economic assistance—an admirable gesture but insufficient to make up the economic shortfall.

Michel Strawczynski, an economist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and former director of the research department at the Israeli central bank, said the cost of previous two confrontations—the Lebanon war in the summer of 2006 and against Hamas in 2014—cost up to 0.5 percent of the GDP and mainly impacted the tourism sector. But this time, “estimations are for a fall of 3.5 percent to 15 percent in annual terms” in the last quarter of this year.

Entire towns have been abandoned and businesses shut down as 250,000 people have been evacuated and forced to seek refuge across hotels in the country or with relatives living elsewhere. Furthermore, the call to 360,000 reservists, who were employed in various jobs in peace time, has stretched companies and made their continuation as profit-making businesses precarious.

“This war will cause additional costs compared to these two (previous) confrontations also because of a massive participation of reservists, who are inserted in the labor market in normal times but will be absent from their jobs during the war,” Strawczynski said. “If the war is long, the impact of lack of human resources will result on a high cost for the Israeli economy.”

Tourism, a sector that makes up 3 percent of Israel’s GDP and indirectly provides 6 percent of total jobs, has been dealt a fatal blow, too. The beach in Tel Aviv and cobbled lanes of the old city in Jerusalem, the main tourist attractions, both lie vacant.

It’s peak tourist season, but restaurants and bars in the historical quarters of Jaffa gate served few visitors, mostly journalists. The tourists who throng this part of the world to soak in the sun and bathe in a mix of Middle Eastern and Western vibes—enjoying hummus and cocktails in a breezy balmy November—were absent.

The hotels were hosting the internally displaced, with some subsidy from the government but still at a huge loss.

“It’s peak season, but there are no tourists,” said Mohammad, an Arab Israeli and owner of a candy shop in Tel Aviv who also asked that only his first name be used for safety reasons. “No families, no children lining for candies.” His friend Ahmad Hasuna lifted his hands in the air and looked up at the sky when I asked about his business. “There is nothing. It’s very difficult,” he said and pointed to several shops that hadn’t opened since the war broke out in the south.

Both Israeli Jews and Arab entrepreneurs here were united in their desperation, sipping on coffee and hopelessly gazing at the empty streets. At the Market House Hotel nearby, Alaa Marshagi, an Israeli Arab, sat at the reception and said there was only 10 percent occupancy compared to previous years, “all journalists.” His colleague Avi Cohen, an Israeli Jew, said most of the rooms were occupied by people who evacuated from the south at a heavy discount. “We are hosting them at a 50 percent loss, plus free meals,” he told Foreign Policy. “Right now, the government is helping, but that’s only until Nov. 22.”

The startup industry in Israel has been a great success and, although it stands to suffer less in comparison, it was already under pressure as investors pulled back from a country mired in mass protests over judicial reforms. Investments in the sector halved last year sensing instability as thousands gathered against the government’s judicial reforms that would allegedly weaken the courts and empower ruling politicians.

A group of global venture capitalists have come to the aid of budding Israeli startups and are trying to raise millions of dollars to save them from bankruptcy. They have launched an initiative called Iron Nation to protect the companies, and the country’s economy, from collapsing under pressure. (Up to 20 percent of reservists doubled up as employees in the tech industry.) The founders of the initiative claimed that 150 companies have already sought help for a chance at receiving between $500,000 and $1.5 million to keep their businesses running.

According to a study by Hebrew University titled “Civil Society Engagement in Israel During the Iron Swords War,” nearly half of the Israeli population volunteered in some way to help compatriots directly or indirectly reeling under the effects of Hamas’s attack and the concomitant war. Professor Michal Almog-Bar, the author of the study, told Israeli media that domestic philanthropic organizations and NGOs donated “tens of millions of dollars,” while donations from Jews in North America was estimated to run into hundreds of millions of dollars.

Meanwhile, to meet the costs of the war effort—expected to rise into billions of shekels—the economists are pushing the government to reprioritize the budget. Three-hundred Israeli economists have written an open letter to the government and called on Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who hails from a far-right party, to urgently implement a range of measures however unpalatable to some of their constituents. They have asked that the money kept aside for educational programs for the ultra-orthodox communities be redirected to military expenditure.

Strawczynski said the priorities are to reallocate billions of shekels towards “defense expenditure” and to “indemnizating affected individuals and firms” particularly in the south and the north. “We recommend redirecting what is called coalition funds,” money allocated for key programs of different parties under the coalition agreement. “These issues are related to the groups of voters of those parties, and not to common interest,” he said.

The Israeli government has presented an economic aid plan that offers $1 billion to help businesses, and Finance Minister Smotrich has promised that “whatever doesn’t involve the wartime effort and the state’s resilience will be halted.” The far-right, however, is still adamant on not letting Palestinians be a part of the solution. National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir, the most vocal far-right leader, has blocked a proposal to hire more Palestinians to meet the shortfall of workers in Israel farms.

The agriculture industry faces a shortfall of 10,000 farmers and the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture has proposed a plan to hire 8,000 of those from the West Bank—Palestinian women of all ages and men at 60 or older. Gvir, however, warns of a security risk, a claim that some support as mistrust between Israelis and Palestinians deepens but others find prejudiced, especially since 2 percent of the Israeli population already comprises Israeli Arabs who arguably have some sympathy for the Palestinian cause but are not in cahoots with Hamas.

Even as the shekel depreciated, a five-member committee of the Bank of Israel which oversees the monetary policy has decided to maintain the interest rate at 4.75 percent and the governor of the central bank underscored the economy’s resilience. “There should be no major changes to our fundamental fiscal position,” Bank of Israel Governor Amir Yaron said.

Israel is not new to conflict and has in the past sailed through, but this time the war is expected to be a longer affair and may turn into a regional confrontation. Strawczynski suggested the key factor would ultimately be the length of the conflict.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tikva Frymer-Kensky, Wisdom from the Witch of Endor

Tikva Frymer-Kensky, Wisdom from the Witch of Endor @Eerdmans -

Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. Wisdom from the Witch of Endor: Four Rules for Living. Foreword by Adele Reinhartz. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2024. xvii+78 pp.; Pb; $12.99. Link to Eerdmans This sermon was discovered among Frymer-Kensky’s papers after she died in 2006. She served as professor of Hebrew Bible and history of Judaism at the University of Chicago. She was known for In the Wake of the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

For a school assignment, I'm assembling an anthology around the theme of queer divinity and desire, but I'm having a hard time finding a fitting essay/article (no access to real academic catalogues :/ ), do you know of any essays around this theme?

below are essays, and then books, on queer theory (in which 'queer' has a different connotation than in regular speech) in the hebrew bible/ancient near east. if there is a particular prophet you want more of, or a particular topic (ištar, or penetration, or appetites), or if you want a pdf of anything, please let me know.

essays: Boer, Roland. “Too Many Dicks at the Writing Desk, or How to Organize a Prophetic Sausage-Fest.” TS 16, no. 1 (2010b): 95–108. Boer, Roland. “Yahweh as Top: A Lost Targum.” In Queer Commentary and the Hebrew Bible, edited by Ken Stone, 75–105. JSOTSup 334. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim, 2001. Boyarin, Daniel. “Are There Any Jews in ‘The History of Sexuality’?” Journal of the History of Sexuality 5, no. 3 (1995): 333–55. Clines, David J. A. “He-Prophets: Masculinity as a Problem for the Hebrew Prophets and Their Interpreters.” In Sense and Sensitivity: Essays on Reading the Bible in Memory of Robert Carroll, edited by Robert P. Carroll, Alastair G. Hunter, and Philip R. Davies, 311–27. JSOTSup 348. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002. Graybill, Rhiannon. “Yahweh as Maternal Vampire in Second Isaiah: Reading from Violence to Fluid Possibility with Luce Irigaray.” Journal of feminist studies in religion 33, no. 1 (2017): 9–25. Haddox, Susan E. “Engaging Images in the Prophets: Feminist Scholarship on the Book of the Twelve.” In Feminist Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Retrospect. 1. Biblical Books, edited by Susanne Scholz, 170–91. RRBS 5. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2013. Koch, Timothy R. “Cruising as Methodology: Homoeroticism and the Scriptures.” In Queer Commentary and the Hebrew Bible, edited by Ken Stone, 169–80. JSOTSup 334. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim, 2001. Tigay, Jeffrey. “‘ Heavy of Mouth’ and ‘Heavy of Tongue’: On Moses’ Speech Difficulty.” BASOR, no. 231 (October 1978): 57–67.

books: Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006. Bauer-Levesque, Angela. Gender in the Book of Jeremiah: A Feminist-Literary Reading. SiBL 5. New York: P. Lang, 1999. Black, Fiona C., and Jennifer L. Koosed, eds. Reading with Feeling : Affect Theory and the Bible. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2019. Brenner, Athalya. The Intercourse of Knowledge: On Gendering Desire and “Sexuality” in the Hebrew Bible. BIS 26. Leiden: Brill, 1997. Camp, Claudia V. Wise, Strange, and Holy: The Strange Woman and the Making of the Bible. JSOTSup 320. Gender, Culture, Theory 9. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000. Chapman, Cynthia R. The Gendered Language of Warfare in the Israelite-Assyrian Encounter. HSM 62. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2004. Creangă, Ovidiu, ed. Men and Masculinity in the Hebrew Bible and Beyond. BMW 33. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2010. Eilberg-Schwartz, Howard. God’s Phallus: And Other Problems for Men and Monotheism. Boston: Beacon, 1995. Huber, Lynn R., and Rhiannon Graybill, eds. The Bible, Gender, and Sexuality : Critical Readings. London, UK ; T&T Clark, 2021. Guest, Deryn. When Deborah Met Jael: Lesbian Biblical Hermeneutics. London: SCM, 2005. Graybill, Rhiannon, Meredith Minister, and Beatrice J. W. Lawrence, eds. Rape Culture and Religious Studies : Critical and Pedagogical Engagements. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2019. Graybill, Rhiannon. Are We Not Men? : Unstable Masculinity in the Hebrew Prophets. New York, NY: Oxford University Press USA, 2016. Halperin, David J. Seeking Ezekiel: Text and Psychology. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993. Jennings, Theodore W. Jacob’s Wound: Homoerotic Narrative in the Literature of Ancient Israel. New York: Continuum, 2005. Macwilliam, Stuart. Queer Theory and the Prophetic Marriage Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible. BibleWorld. Sheffield and Oakville, CT: Equinox, 2011. Maier, Christl. Daughter Zion, Mother Zion: Gender, Space, and the Sacred in Ancient Israel. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2008. Mills, Mary E. Alterity, Pain, and Suffering in Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel. LHB/OTS 479. New York: T. & T. Clark, 2007. Stökl, Jonathan, and Corrine L. Carvalho. Prophets Male and Female: Gender and Prophecy in the Hebrew Bible, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Ancient Near East. AIL 15. Atlanta, GA: SBL, 2013. Stone, Ken. Practicing Safer Texts: Food, Sex and Bible in Queer Perspective. Queering Theology Series. London: T & T Clark International, 2004. Weems, Renita J. Battered Love: Marriage, Sex, and Violence in the Hebrew Prophets. OBT. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1995.

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

The cheap and easy way to protect your family from colds and flu

Elderberries naturally contain vitamins A, B, and C and stimulate the immune system. Israeli researchers found that the complex sugars in elderberries support the immune system in fighting cold and flu. They developed several formulas based on these complex sugars that have been clinically shown to help ameliorate all kinds of cold/flu.

In fact: “Dr. Madeleine Mumcuoglu, of Hadassah-Hebrew University in Israel found that elderberry disarms the enzyme viruses use to penetrate healthy cells in the lining of the nose and throat. Taken before infection, it prevents infection. Taken after infection, it prevents spread of the virus through the respiratory tract. In a clinical trial, 20% of study subjects reported significant improvement within 24 hours, 70% by 48 hours, and 90% claimed complete cure in three days. In contrast, subjects receiving the placebo required 6 days to recover.”

What you need to make a single batch:

2 x Empty Kilner Bottle or empty glass jars 1 x bottle 100% cold pressed Biona Elderberry Juice 4 x Tablespoons of maple syrup, algave or raw honey 1 x Kakadu Plum powder

METHOD: Mix it altogether in a jug Pour into the kilner bottle or glass jars Store in the fridge

I use Kakadu plum powder as it is a powerhouse of vitamin C and full of antioxidants, a fantastic natural preservative and has the highest food-based form of vitamin C of any food known on this planet.

The elderberry juice can have a bitter taste without the sweetener added, this will depend on preference.

You could substitute the honey with maple syrup to sweeten (if vegan or under 12 months). Raw Manuka honey can also be used for children over 24 months.

DOSAGE: Elderberry Syrup is suitable for 12 months and over and if you are pregnant or are breastfeeding if you have used maple syrup.

**If you have used Manuka honey in the mixture, then it is ONLY suitable for children OVER 24 MONTHS**

Take 1 x Tablespoon every day (adults) Take 1 x Teaspoon everyday (children)

If you are feeling sick or have a cold or the onset of flu, increase dosage to 1-2 tablespoons every 3-4 hours up to 4 times per day (for children over 12 months with Maple syrup use 1-2 teaspoons

For children over 24 months and you have used raw Manuka honey then its 1-2 teaspoons per day.

About Helen

Helen Monaghan B.A (hons) has an active interest in Holistic and Alternative Medicines since 2006, where she started making her own chemical free, natural, and organic skin care products for her friends and family.

Since then, she has studied hard to become the best in her field of natural health and self healing.

Helen has worked with many other professionals across the globe where she has helped them to complete books that has inspired thousands of people across the planet and today she brings with her new ways of living, using her knowledge and expertise where she encompasses a variety of different healing techniques.

This year she has created her Online Store and the Academy of Self Mastery learning centre, so that many more people have access to her natural health and wellbeing products, whether it be skincare, mini course, e-books or other ways of being and staying healthy.

0 notes

Text

A Visual way to Music. Seminar

The Hebrew University, Jerusalem Musicology Department: Dr. Roni Granot

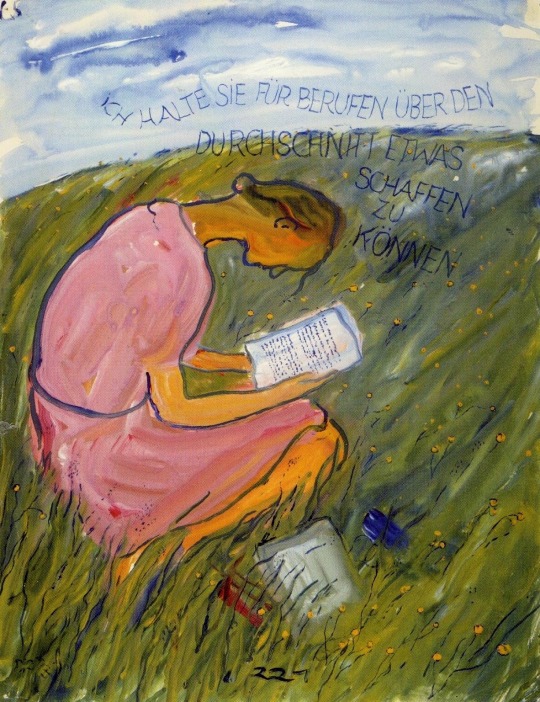

Music Cognition Seminar December 2006 A visual way to music by Jezabel Cohen Foreword This study is inspired on the work of a painter called Charlotte Salomon, at her last few years of her short life she produced 800 paintings with the artistic talent to document the tragic story of her life using a variety of multimedia effects in her work, where she combined in texts, audio and mainly through her painting. The set of visual art together with elements like literature, drama, dance, or music gave as a result a tool of great and powerful communicational force that transforms the original piece of art as well of the affecting alteration on the receptor when approaching to the art. Reading, watching, listening, performing and understanding what is in front of us and mainly when all is together at once, requires a row of information processing that can change meaningfully our awareness of things and our enjoyment of them. My work will focus in the study of the use of music mutually with other arts, and how can music receives a great deal of protagonism alone sometimes and how different it becomes while combined with visual arts, how is it that we can experience such a catharsis, sometimes without noticing, and how can these combinations change the meaning, the understanding and the perception of our way to music. Most listeners of music are seeking for pleasure in music and this is probably one of the reasons it is so much important for our lives and it’s not a minor pleasure, to try understanding it. Music has the power to take us away from reality in a very unique way and has the impetus to introduce itself into our lives and change our moods and emotional activity. Like a language that we can’t imagine it without accents or intonations that are some of the different ways words may sound, music is the component for distinguishing between one idea, one intention and also emotions or feelings, but most of all has the ability to transport us to imaginary places. When speaking of ideas and of pictures in music it is very important to remind the category of instrumental music that many composers of the romantic period made use of, Program Music. Program music is music intended to bring extra musical ideas, images in the mind of the listener by musically representing a scene, image or mood, it was meant for instrumental music and not for music with words, lieder or operas. Some examples are the symphonic poems of Liszt, based on literary narrative and illustrative elements or Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. Works of music are almost always suggesting ideas that are the understanding of the relationship among people and the world and the people and things, all kind of relationships. Ideas are the product of countless human actions, are not emotions, but they transform the life of people and change their emotional life. For that it is almost impossible to think music without taking in account time place, society, history and nature of a work of music, the real context of a piece of music that created it is very hard to ignore when analyzing music. Music cannot do all but is it almost the art that can reflect many aspects of people’s life faithfully. Berlioz comes out against the division made by theoretician Carpani, who claims that music must imitate nature just as in drawing, which is direct imitation. Contrary to this Berlioz maintains that there is no need for direct imitation of nature and he sets 4 conditions for “correct” imitation: Imitation must not be the goal, but only a means for presenting an idea.

The composer must imitate only what music can imitate in nature Imitation must be accessible to the listener (i.e. not too sophisticated) Direct imitation must not come in place of indirect, spiritual imitation The goal of spiritual imitation, which Berlioz supports, is to attract the soul of the listener, passing on the experience. In terms of the experience music rises above the plastic arts, but the moment it tries to describe objects in nature perfectly, it misses the mark. (Therefore music needs to describe the dimension behind the reality, a direct continual line to Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer criticized the philosophers of his generation, as well as the musicians. The need to translate the imagination of music into words is distorted. The language of music is specific and cannot be spoken in text. He brings the example of Beethoven as the expression of general feelings, abstractly with no textual content. According to him Beethoven brings his feelings in a pure form. Therefore only instrumental music can express the essence of music perfectly. . The melody expresses the intellectual world, the feelings, while the words are the language of reason. In The Republic Plato declared “when modes of music change, the fundamental laws of the State always change with them” (Republic IV, 424c). He meant to the emotional influential powers that music has when good or bad to the human soul because it possesses an ethical influence and is intimately connected with it through the concept of harmony of the soul and of harmony of the state. I don’t know how much relevant a statement like this can be nowadays. General aspects on -Music and Pictures- by Stephen Davies From his book Musical Meaning and Expression Davies opens the preface of his book with a description of one of the last parts of the film Close Encounters of the Third Kind, by Stephen Spielberg, there the extraterrestrials and humans attempt to communicate neither in Alienese (extraterrestrial language) nor in English, but in music. The aliens might have share the view that music can be the universal language. In his book Musical Meaning and Expression, Stephen Davies proposes several comparisons between music and language, music and pictures, music and symbols, feelings, expressions of emotions, response and understanding. He is exploring the meanings of music. In chapter two of his book he compares Pictures with Music. Music used in operas, film and ballet not only to accompany the action and the texts but to illustrate the texts. Davies set up his theory by saying that the idea is perhaps rather than asserting or describing, as language does, music represents or depicts, as nonabstract paintings and sculptures do.

One part of program music claims to be representational, using literary titles and texts to focus the listener’s attention on the subjects depicted. Many composers believed that they could paint pictures in sound. The differences between painting and music, rather than marking a distinction between types of representation, are such as to suggest that music is not a depictive art form. He is suggesting that music has a certain power as pictures do to depict things as paintings do. He mentions Kendall Walton, a philosopher at the University of Michigan that develops a theory of make-believe and uses it to understand the nature and varieties of representation in the arts. He has written on pictorial representation, fiction and the emotions, the aesthetics of music, in his view all paintings are representational and no photographs are representational. He distinguishes depiction from representation, he says that depiction is a species of representation. Davies on the contrary is using both terminologies as synonymous.

Davies first defines pictorial representation, he takes pictures, drawing, silhouettes, also statues, dolls to provide the paradigm and to discover the central condition of music that if it were representational, would be so in its own way. He is not asking whether music might represent the same subjects as may be depicted in paintings or nevertheless whatever differences there are between music and pictures. If music is representational it must have the general conditions for that.

The differences between music and pictures rather than marking a distinction between types of representation are such as to say that music is not a depictive artform. He focuses in two types of theory “semantic”, which gives priority to the work’s title, the title of a work can contribute to representation only where elements are systematized in a way that might allow them to combine appropriately with the title to secure denotation and a characterization of the subject, and “seeing –in” accounts of representation. Davies himself is defending the seeing-in account. He lists his own four conditions for art as pictures, none of which is sufficient alone, the second and fourth of the conditions would agree with both, the“semantic” and “seeing –in” theories of depiction. The seeing-in theory endorses the third condition while the semantic theory rejects it. (1) Intention, it is a necessary condition for X’s representing Y that X be intended to represent Y. Three objections must be raised for this conditions right for representation, 1. There are noncircular ways of specifying the intention-example, as the intention to produce an X in which Y can be seen. Consistency in the use of the relevant conventions is important for representation. 2. When by accident the representation happens, example a camera is triggered by mistake and produces a representation, despite the absence of the relevant intention. If music is representational it is so by equivalence with painting rather than with photography. Such musical image making as is achieved relies in the composer and not in a machine mechanism. 3. Against relevant intention as necessary for representation might be put this way: Misunderstanded intentions. The gap between a painter want to transmit and what is understood or what is the result of it mainly depends on the intimate relation between the painter and the conventions for pictorial representation that have a life of their own, more often the artist succeeds, so the viewer is the direct receptor for the effect the artist wanted to create. A painting can look as something different from the intentions of the artist. There is a break between the conventions for representation and their intentional use, and this because the conventions are used successfully, most of the time, putting the exceptions mentioned above. Representational character of music assumes that there are established conventions for musical depiction and that suppose that musical representation is possible. Davies’s approach provides some grip on Walton’s defense an anti-intentionalist posture, example a cloud might represent a camel, this position is designed to stress the degree in which the conventions of representation take on a life of their own. (2) Medium/content distinction, it is necessary condition for X’s representing Y that there be a distinction between the medium of representation and the represented content. Arthur Danto sustains that the use of the medium of representation not only separates the representation from the subject, it allows the depiction to comment on its subject in presenting a way of seeing that subject. Artworks are about the mode of representation as much as they are about the subjects represented. Arthur Danto (1981) sustains that if one thinks on the medium of representation as the stuff of representation, then the use he puts to this point appears not to sustain the force of his claims. But if we agree that the idea of the medium of representation pays attention to not only the material qualities of the stuff but to the histories, context and traditions of the use of that stuff, his claims says Davies are more acceptable.

(3) Resemblance between perceptual experiences It is necessary condition for X’s representing Y that there be a resemblance between a person’s perceptual experiences of X and of Y, given that the person views X in terms of the applicable conventions. According to Wollheim, the attempt to represent a man in painting is successful only if a man can be seen in the painting. This position which Davies calls it the seeing-in theory, distinguishes between representational and abstract paintings by reference to the content of the visual experiences to which they give rise. He accepts the version of the seeing-in theory that treats as a necessary condition for representation a resemblance between one’s seeing X in a representation and one’s seeing X, provided that it also allows that the naturalness of this element is tempered, structured, and shaped by conventions that have varied in their detail place to place and time to time. Davies concluded that the resemblance condition claim is at its most plausible when it compares music’s dynamic pattern to that apparent in nonverbal, behavioral expressions of emotion. (4) Conventions X represents Y within the context of conventions (that might be regarded as constituting a symbol system), so that the recognition of Y in X presupposes the viewer’s familiarity with those conventions and his viewing X in terms of them in perceiving Y in X. This condition concerns to the recognition of a representation as such. In musical depiction, Davies’s argument is trying to explain how applicable is the musical case of representation, above described in general terms, by giving conclusions mainly indicating that music is not a depictive art. Music representational powers can’t be denied in ballet or opera, but the argument focuses not in the contribution of music to such artworks, but on its own capacity to be a depictive in its pure form. Many musical representations are a regular and persistent aspect in music, but not common in instrumental works. The most often identified as depictive types of music are the genres of song and program music. Other views claim that all music is programatic and consequently depictive, J.W.N. Sullivan (1927) who describes all great music as involving a program about human spirituality. Davies names Jacques Barzun, Richard Kuhns and their support to the view where musical representation is important precisely because it is enjoyed, and that to be enjoyed it must be perceivable, since is seeing every human action as programmatic and self referential and self representational. These views involve and expansion of the concept of representation. The depiction theories that most fit to the musical case, there seem to be no conventions which for pure music would allow one to distinguish relevant difference style or school of representation, as there are within painting. To deny that there are many distinctive musical styles is not to deny that music is a conventionalized artform. Davies is trying to say that each style may characterize through rules governing the combination of the musical elements and they don’t function as those of a representational symbol system. Davies again sustains that the seeing in theory allows that titles are important in determining the represented content of the work, so it has not consistency to exclude reference to them in the musical case. And the problem then is focused not in the vagueness cases of musical depiction but with the nature of what it is that is said to be represented. In the case of paintings if a man is depicted in a painting, this is because people familiar with the relevant conventions have a visual experience as of a man while looking at the picture. For music, Davies sustains that one would expect the relevant perceptual experience to be aural, while music sometimes is represent is said to represent sounds, so that one can hear a sound of a hand knocking on the door (Shostakovich, String Quartet N08) in hearing repeated drumbeats, more often it is said to represent things that have no sound. All music seems to be depictive for love, yearning, motion and the phenomenal qualities of emotions and moods. Seems to Davies that the seeing in theory is not relevant if the perceptual element of the experience is lost and this must result where one attempts to accommodate the musical depiction of the phenomenal, nonperceptual qualities of emotional states and the like to a hearing-in account of musical depiction. A person, who knows that Debussy’s work is titled La Mer, will be inclined to develop a description of the work in suitably watery terms. That person naturally enough, seems to hear such things in the work. But this need not be evidence of the work’s representationality, even if the title is part of the work.

Music is expressive in character rather than representational as pictures are, and sometimes the title of a musical work can be relevant to an appreciation of the detail of its expressive character. Representation might be achieved by music in its marriage with words, states Davies, though depiction is not a feature of pure music. After all music is an important element in many hybrid artforms-ballet, opera, film and song - that are undoubtedly held to be representational. Music is joined with many other elements and in many different proportions, to create hybrid artforms, Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, based on ten drawings and watercolors produced by a deceased friend, the architect and artist Victor Hartmann, through works with an accompanying text supplied or indicated by the composer, through works with a narrated story, like Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, through song, choral music, oratorio, mass, and the passions, through opera and ballet, through film music, Prokofiev’s famous work for S.M. Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky, or through supplementary music for plays such as Bizet’s music for Alphonse Daudet’s L’Arlesienne, case where the music conforms a more or less supplement to the main artistic fare. Davies says that ballet, opera, song, film should be viewed as synthetic artforms. It is significant that this artforms are not called “music”, as for example orchestral music, choral music, chamber music, etc) music being one element in the whole. It makes sense to talk only of music’s representational place only within the context of the whole to which it contributes. Davies believes that music does not satisfy these conditions and see no interest in holding to the view that music achieves a special variety of representation. The differences between paintings and music are not attributable to the specific character of their modes of depiction. He concludes that while “painting can be depictive, music usually cannot be”. He has rejected the view that music is representational as pictures often are, but allowed that there may be a degree of depiction in music (like that in pictorial representation) based on natural (but conventionally structured) resemblances. Analyzing Musical Multimedia- Nicholas Cook Music and Pictures In this chapter Cook takes a close look to Madonna’s Material Girl, video, to exemplified the theme of study. Cook analyzes the nature of song by saying that this form is not a visual text, in the sense of containing gaps for the incorporation of visual elements, he uses the “visual” word in a logic corresponding to the musical or music-ready text. The pictures serve to open the song up, he says and believes that both music and picture can be understood in terms of distributional analysis, and the relationship between them can be understood as interplay of structurally similar media, with this he intends to say that the pictures can be analyzed musically. For that he analyses in terms of how many words and musical phrases fit in a certain period of time, giving the example on the video of Madonna, Material Girl. He analyzes this through an attempt to destabilize the meaning of the words and, through them, the closure of the song as a whole. The pictures serve to open the song up to the emergence of new meaning. He sustains that many music videos are constructed out of a small number of easily distinguishable visual sections, which are edited in a very similar way that music is constructed (MTV is an example, Cook sustains). “Videos represent visual staff to listen to”, for this statement he gives a graph of Madonna’s video where he cuts the words and scenes, and counts the verses. The main cuts on the video are closely coordinated with also the metre of the phrase structure that come together on the down beat. Another association between cutting rhythms and the distribution of musical model classes would be that the high level of musical redundancy resulting from the immediate repetition is compensated by increased activity in the visuals.

He directs his conclusion to compositional means, a formal link between music and pictures suggests a reflexion on the composition of both, the introduction, the middle, the conclusion, and the structure is the main effect. These views have nothing in common to the points that Davies above bring to light. These are views that take in account only the parameters of video together with music and the distribution into the length of the artwork. Cook observes that little has been done in cross-fertilization between the analysis of song and that of opera, and neither offers much of a model for analyzing music videos or film. It exist virtually nothing in the way of a general theory of multimedia that explains or provides a background of its many genres. Cook says that he intended to start his analyses with still images juxtaposed with music exemplified on record sleeves ( the idea that I had in mind when starting this work) He came to the conclusion that the mix of music with moving images could be a more rich scenario for his work.

Musical Communication The role of music communication in cinema Scott D. Lipscomb and David E. Tolchinsky

The plot begins to thicken, they say (authors say), when one considers what is being communicated, to use a film metaphor. They open the chapter with a filmic example after they had presented a general model of music communication in the book, they‘ll introduce experiential and theoretical models, on the role of music in film and its perception. Investigating the relationship between sound and image in the cinematic context. The authors wants us to pay attention on the difference terminology when talking of film, motion picture and cinema, as they acknowledge the distinction between the three terms and the variety of media types upon which each may exist. Sound can be fitting with an image, in opposition to what is expected or to what is different from what is conventionally anticipated, the sound track can clarify image events, contradict them, or render them ambiguous (Bordwell and Thompson 1985, p.184). The relationship between audio and visual is both dynamic and active. Before the 1990s, as noted by Annabel Cohen (2001) (not Jezabel) the study of film music and its place in the cinema context had been neglected by musicologists, today there is amount of research done and confirming that the presence of film music affects apparently enlarge the emotional content of a visual scene. As well music is able to evoke emotion in a scene that would be neutral without a sound. Psicho, Alfred Hitchcock’s film, in the rainstorm scene, this will have a different effect without any music, this example is quite extreme as we are talking of horror movies and where all kind of effects are being used to bring a certain sentiment of fear in the audience is obviously requested, but this case might demonstrate that also without the sound behind, the effect of horror might not exist at all. The term “film music” is used here as one component of a variety of sounds that includes musical score, ambient sound, dialogue, sound effects and silence. The functions of these elements interact with each other. In the case of absence of musical score, other elements like ambient sound that can function similarly to music are giving dynamic moves and structurally meaningful sound to push the narrative ahead. Music communication as a form of expression is the model described by Campbell and Heller (1980) that consists of a composer a listener and a performer, for this tripartite model it is outlined a process involving states of coding, decoding and recoding. As music is a culturally defined artifact, successful communication will involve shared implicit and explicit knowledge structures. Composers succeeds when in communicating a musical message this one is in proportion to the level of agreement between emotional and/or expressive intent of the message and that perceived by the listener. Kendall and Carterette suggest that this is a process that includes grouping of elementary thoughts units, and these units are mental representations involved in the process of creating, performing and listening to musical sounds. Film music communication empirical models In an effort to give meaning to what Marshall and Cohen (1988) sustain as a model called “congruence-associationist” the model gives connotation of film when is altered by the music as a result of two cognitive processes. Researchers results demonstrate that based upon responses, Potency, strong –weak, the Activity, passive-active and the Evaluative dimension, good-bad, relies on the similarities the audio and the visual components on all three dimensions as determined by comparison. The next part of the model attributes to the similar components between audio and visual. The result they put it in words “the music alters meaning of a particular aspect of the film” (Marshall and Cohen, 1988), they also acknowledge the temporal characteristics of sound and of the image saying that the importance of the accent to events will affect retention, processing, and interpretation, i.e. the point to which significant events in the musical score take place at the same time with significant events in the visual scene.

The purpose of a series of three experiments utilizing stimuli ranging for simple and complex animations, suggested by Lipscomb (1995), gave as a result that two implied judgments appears to be dynamic as that accent structure association plays an important role, when the stimuli was more sophisticated the determinant of meaning in audio appeared in for example when focusing audience attention on specific aspects of the visual image. The changes on complexity and simplification on the experiments of the visual imaginary and musical score (highly repetitive), Lipscomb (1995) in the level of complexity stimuli apparently alter the way that the different audio-visual components are processed in human cognition. The most complex and developed model of film music up to date they say, is the one that Cohen’s (2001) has made.

Congruence-associationist framework to understand film music

communication. That they explain as follow: The model tries to look for meaning that comes from speech, images and musical sound. Level A represents bottom- up processing, based on physics. Level B presents a determination of cross-modal similarities based both on associational and temporal grouping features. A level D represents top-down processing, determined by a person’s past experience and the retention of that experience in long term memory. In terms of this model, levels B and D meet in the observer’s conscious mind level C, where information is ready to transfer it self to short term memory. This model sustains an assumption on visual primacy, the authors of this chapter express their reservation on this assumption and suggest that more research is required before a claim like that can be supported.

Film Music Communication Theoretical Models

The authors open the sub-chapter bringing as an example Richard Wagner as the creator of the form of art that developed in the nineteenth century music drama as the Gesamtkunstwerk, Suzanne K. Langer, music has all the earmarks of the symbol, but one, the existence of an assigned connotation, thus representing an unconsummated symbol. (1942, p.240), this unfinished symbol, (Royal Brown, 1988) is represented by the predominance of the orchestral film score. Brown argues that the very human presence felt through the performance of a vocalist tends to move the musical symbol on step close to consummation. For a film to make impact, it is necessary an interaction between verbal dialogue and cinematic images (consummated symbols) with musical score (unconsummated symbol).

There are three methods presented by Gorbman (1987) where music can “signify” inside a narrative film. Purely musical signification, that comes from syntactical relationships natural in the association of one musical tone with another. Patterns of tension and release give a sense of organization and meaning to musical sound, apart from other spare musical association that might exist. Hamslick’s (1891/1986) absolute music. Cultural musical codes are represented by music that has come to be associated with a certain mood of mind; Meyer’s (1956) referentialism. These associations have been included into Hollywood film industry into conventional expectations, completely known from the start by enculturated audience members- determined by the story content of a given scene. The last influence musical meaning, simply because of the place of the musical sound is within the filmic context are the cinematic codes. Music that represents a recurring theme that illustrates a character or a situation, as well as in the opening credits and the titles music. Film music is determined to communicate the underlying psychological drama of the narrative at a subconscious level (Libscomb 1989).

All sounds - including music – that are meant to be heard by characters of the narrative are referred as diegetic, while those that are not, like orchestral score, are called as non-diegetic. Diegetic music is in a more conscious level and non-diegetic remains at the subconscious, but the authors say that more research must be done to probe this true. Michael Chion (1990/1994) distinguishes these two types using the term onscreen and off-screen, respectively. The authors name two more models of the role and function of film music, Gorbman (1987) compiled a list of principles for composition, mixing, and editing classical Hollywood film between the 1930s and 1940s King Kong, Gone with the wind, Casablanca.

Seven principles were considered as discursive, in the book the authors give a graph with six principles: invisibility, Inaudibility, Signifier of emotion, Narrative cueing, Continuity, Unity.

The second model is the one proposed by Nicholas Cook (1998), above described in general terms on his chapter on Music and Images. The model presented here explains the express purpose of analyzing musical multimedia, like the present authors of this chapter agree with Cook on the often-stated fact that music plays a subsidiary role to the image, what he refers to as depictive translucency of image. In opposition to what Gorbman classifies music-image and music narrative as mutual implication. Cook explains that words and pictures, deal with the objective, while music deals primarily with responses, that is with values, emotions, and attitudes, the connotative qualities of the music complement the denotative qualities of words and pictures (p.22). Cook presents three ways for the identification of similarities and differences between the component media, with the parameters of conformance, complementation, and contest. The model provides two processes for determining this relationship. The first to identify the similarities, determining the consistency with each of the media component, an application of this model would be to ask if the amount of information presented via both the auditory and the visual are similar. Also a question can be whether the music and the image are consistent or merely coherent. The authors after this models say the they relationships and perceived meanings can be reciprocal as one can state that it is equally valid to say that music projects the image meaning or the other way around. Then conformance would be the one that fits with the similarity test. In places where the component media is coherence rather than consistent, one steps to the second part of the model, the difference test. Here the uncertainty relies on whether the media components relationship is in coalition with another inter-media component, and if this exist the relation is the one of contest. Without any contradiction or similarities the relation is of complementation. Were the media shares the same narrative structure but each medium elaborates the underlying structure in a different way (Cook 1998, p.102). Music can convey mood in the film, can convey scope in film, can convey the quality and size of a space, can establish the narrative’s placement in time, to authenticate the era or to provide a sense of nostalgia. (Stuessy and Lipscomb 2003, pp.410-11), Amadeus (1984), and Immortal beloved. Music can convey a sense of energy.

The level of perceived energy increases by the presence of music, and can be manipulated, i.e. Adagio for Strings of Samuel Barber, appeared in the scene where the battle in the movie Platoon (1986) is taking place. Music can also communicate a perspective or a message intended by the director or as applied by Gorbman to describe the capability influences of music in the meaning of the film, the term of commutation, as an example of the dynamic manner in which cinematic meaning can be manipulated by sound. (Gorbman, 1987) Music can convey the internal life or feelings of a character, one of the most used effects in cinema as well as in opera, the unspoken thoughts that underline the drama. Music can convey character, the director can choose to define a character by sound, in Psycho, the mother character, in Der Ring des Nibelungen (1857-74) Wagner’s nineteenth century music drama, the leitmotif the theme or the musical idea to define and identify a place or object, idea state of mind, supernatural or any other element in the work.