#exegetical study

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Spiritual Gift of Teaching

The New Testament references the gift of teaching in several passages (Rom 12:6-8; 1 Cor 12:28; Eph 4:11). This gift involves the ability to clearly explain and communicate biblical truths so that others can understand and apply them. A teacher, in the biblical sense, is responsible for instructing others in the doctrines of the faith, helping believers grow in their knowledge of God and in their…

View On WordPress

#1 Corinthians 12:28#2 Timothy 4:2#Bible exegesis#Bible study resources#Bible teacher&039;s journey#Bible teaching#biblical communication#biblical expositors#Biblical instruction#biblical transformation#biblical truths#Christian contentment#Christian integrity#Christian Ministry#Christian scholarship#Christian service#Christian stewardship#church edification#divine guidance#divine provision#doctrinal integrity#doctrinal teaching#early morning study#effective ministry#Ephesians 4:11#exegetical study#expository preaching#Ezra 7:10#Ezra&039;s example#faithful teaching

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gates of Hell Shall Not Prevail: A Proper Exegetical Commentary and Analysis of Matthew 16:18

The Grave Has No Victory When Jesus declared in Matthew 16:18, “the gates of hell shall not prevail against it”, He made one of the most powerful statements in scripture about the endurance of His church. This promise isn’t just about survival—it’s a declaration of victory over death, evil, and apostasy. For Christians, and particularly Latter-day Saints, this verse affirms divine authority, the…

#Bible#Biblical analysis of Matthew 16:18#Binding and loosing authority explained#Christ&039;s divinity in Matthew 16:18#Christianity#Exegetical study on Matthew 16:18#faith#Gates of hell shall not prevail meaning#God#Greek meaning of gates and hell in Matthew 16:18#Jesus#Jesus&039; authority over death and the grave#Keys of the kingdom in the Bible#Matthew 16:18 commentary#Matthew 16:18 theological interpretation#Peter&039;s confession and church foundation#Revelation of Christ&039;s authority in the Bible#Spiritual significance of the keys of the kingdom#Symbolism of keys in Scripture#Understanding the gates of Hades

0 notes

Text

Women Disciples: Jesus's Call to Mary of Magdala

John has put it on record that Jesus called women as his disciples and commissioned them to apostolic ministry just as he did with men, and we can do no less today. #MaryMagdalene #WomenDisciples #WomenApostles #John20

Though Mary of Magdala is a well-known figure in the gospels, she is not introduced by name until Jesus’s crucifixion in John’s Gospel (John 19:25). John doesn’t explain who she is, or what her relationship is to Jesus or his family, but there she is, with John and Mary, Jesus’s mother. That alone says how important she was to Jesus’s inner circle. The Morning of the Resurrection 1886 Sir Edward…

View On WordPress

#archaeological#Archaeology#Bible#Bible study#biblical teaching#biblical women#Christ#Egalitarian#equalitarian#exegesis#exegetical teaching#expository teaching#feminism#feminist#Jesus#Jesus Christ#Jesus Messiah#mary magdalene#Mary of Magdala#Messiah#scriptural teaching#scriptural women#Scripture#WOmen#women apostles#women deacons#women disciples#women in Scripture#women in the Scriptures#women of the Bible

0 notes

Text

WE ARE IN A SPIRITUAL WARFARE, RELIGION WILL SOON DIE. THE TRUTH IS COMING

So much overlooked wisdom in the book of Galatians. In my humble opinion, i feel if you don’t fully understand this book it’s so easy to misinterpret the entire Bible. We are dived as a nation because we focus on religion instead of the heart of Christ’s message. It’s dishonorable when we miss that true righteousness comes through faith, not rules. God always intended the laws to be a temporary measure until Jesus came. Of course this text is referring to the gentiles and the jews however what is the author trying to tell us?

This is where you learn how to use different bible study techniques . My favorite is cross referencing, observational study and word study. I also primarily like to focus on the heart of the father because no one talks about how central faith is to the Christian life superseding a lot of the things we face today. # 1 being someone appearance. Faith is how righteousness is gained because this is what leads to a transformed life empowered by the holy spirit like nothing else. Stop disqualifying people because they are different. Do not put limits on our God and what he can do through someone else's unique story.

I want to emphasize this does not mean we encourage sinful living and do whatever we feel like doing. Christ freed us so that we could live lives that truly honor God. He did not Free us so we could gratify our flesh and do as we wanted. What is being said here is that, there is a right and proper use for this freedom. It is a transformation of the heart that gets one justified.

The Lord judges a person by their HEART and that is clearly stated in 1 Samuel 16:7 … Truly being saved means, it is no longer YOU who lives but it is Christ who lives in you. There is so much theological goodness in this book if you really take the time to understand it. It is without a doubt exegetically ambiguous so it can be difficult to fully understand. However our human classification system has nothing to do with whether we are loved, saved or can participate in the community of the kingdom nor your ability to conform in those things.

So when we put conditions back onto the gospel saying “you have to be this” or “be that” in order to gain access to God that is literally saying that there is something more important than faith and stronger than Gods love for us.. We need to bring back relationship the way it is was always meant to be. Talk to God . Get your heart right with him . He’s a lot cooler than what people paint 🎨 …

-Mesh

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

alarmed by what you can read in Christian theological journals today (from Peters, 2023, Adultery as sexual disorder: An exegetical study of Matthew 5:27–30, click)

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ten Questions for Writers

Thank you for the tags! @artsyunderstudy @roomwithanopenfire @youarenevertooold @emeryhall @monbons @larkral I'm eating up reading your answers because we're all so DIFFERENT.

How many works do you have on AO3? 9 (technically 10 but we orphaned one of them out of shame)

What’s your total AO3 word count? 99,978 (mine) + 7,531 (shared) + 9,991 (someone else's) = 117, 500 (total)

What fandoms do you write for? presently, Carry On but back during my high school ff.net days I did some Percy Jackson/Heroes of Olympus (Percabeth and some separate OCs), Alex Rider (OCs), The 100 (as an elaborate prank), Harry Potter (literally just a My Immortal parody), and Divergent (OCs) and if they weren't oneshots they were never finished.

Do you respond to comments? Why or why not? YES! I'm currently behind on my replies, but it's so fun! It's like a book club but for stuff I created!!???? Shit rocks. I fully didn't expect anyone to read IKABIKAM (my first fic on ao3) when I first published it and so every comment still feels like a miracle.

Have you ever had a fic stolen? No.

Have you ever co-written a fic before? Yes! I love collaborating because it gives me something to bounce off of. A scene partner. A ticking timer. It's like lifting a heavy object by yourself versus getting someone else to bear some of the weight with you. It's easier. I also find myself constantly seeking collaboration with other people even with my solo fics. I'm all up in those DMs pestering people both as motivation and as external processing. And by GOD, do you fuckers have some good ideas. Y'all make me exponentially better.

What’s your all-time favorite ship? SnowBaz but also in a very real sense...Percabeth. (You never forget your first.)

What are your writing strengths? I got my start with rping, so dialogue is really comfortable for me. I also think my training in other art forms (dance, music, theatre, film, academia) positively influence my approach. When writing action, I often mentally frame it as 'blocking' the scene or 'choreographing' the movement. When crafting sentences, I'm constantly evaluating the rhythm and rhyme and repetition (not to mention alliteration) as if it's a song, always searching for the perfect word or metaphor. I also listen to actual songs and pull the emotion from them, using them as character studies or a musical soliloquy. I imagine shots and then write what I see from the perspective of a director explaining the actor’s motivating thoughts. I constantly revisit my thesis, grounding the narrative in callbacks and a cohesive structure like it's an academic paper. And all those things combined create this kinetic cause and effect style I'm really proud of and tangibly improves every time I write something new.

What are your writing weaknesses? I do not have a firm grasp on proper grammar. I'm also really slow and inconsistent with my output because my process is so physically disorganized and meticulous which often frustrates me. I'm also impatient. I don't do wholesale messy drafts; I edit as I go and when I'm done I want it published immediately. I also fall victim to the white room syndrome with physical descriptions. Establishing shots? Don't know them. What a guy looks like? What they're wearing? Sorry, I haven't told you because it felt weird to jam in there. Outside of fanfiction, I also struggle with creating something from nothing. I'm a theologian rather than a god. I much prefer playing in a sandbox and exegeting meaning from someone else's grunt work rather than conjuring the wood and the sand myself. My writing is also incredibly referential to pop culture which I'm not sure would translate outside of fanfic, but I guess I'll cross that bridge if I ever get to it.

First fandom you wrote for? Divergent (big cringe)

Now tagging! @onepintobean @cutestkilla @theearlgreymage @thewholelemon @mooncello @brilla-brilla-estrellita @you-remind-me-of-the-babe @bookish-bogwitch @facewithoutheart @fatalfangirl @urban-sith @prettygoododds @valeffelees @ileadacharmedlife TELL ME HOW YOU WRITE YOU GENIUSES

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

When you an other commenters talk about Watsonian and Doylist, do you mean diegetic and exegetic? I am asking for clarification as much for the fancy terms as well, because I've never really been certain that's how they are being used when discussing story, and the online definition I found is more about music, so if you want to answer this, if you could explain a little more than yes or no, I would really appreciate it.

Watsonian vs. Doylist are terms to describe something in context of the narrative. Something that is Doylist comes from outside of the narrative structure, while Watsonian is internal. The names comes from Sherlock Homes, a Watsonian perspective is from a character in the novel (Watson) while Doylistic perspectives are from outside the novel (Doyle, the author).

Watsonian perspectives are similar to diegetic things, which are things contained within the narrative structure. The reason why it's used as a term to discuss sound has to do with musical scores - diegetic sound is sound that actually exists within the narrative, while extradiegetic sound would not be. Think Star Wars, John Williams might have an excellent score to a lightsaber fight, but it's not internal to the world and story in and of itself; it's extradiegetic meant to enhance the experience of the consumer. But the diegetic level can come to mean other issues as well, such as the level of narration. A third person omniscient narrator would be extradiegetic, literally external to the narrative, while a first person limited narration would be diegetic, internal to the narrative. There are advantages and disadvantages to both, depending on how you want to tell your story.

Exegetic means critical interpretations of works, which includes study of the author. So, for example, discussing the context of GRRM's Vietnam experiences insofar as it relates to his perspectives on war (most evident with the Broken Man speech) would be considered exegetic.

Thanks for the question, Anon.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

But what is most prized is not elegant verbal trickery, but rather the putting into words of a cosmic truth. This aspect of Vedic religion has been much discussed -- and much disputed -- especially in the last fifty years or so. The discussions have centered around two terms, bráhman- and tá-. The neuter noun bráhman- is the derivational base to which the masculine noun brahmán- 'possessor of bráhman-' and ultimately bråhmaa-, the name both of the priestly caste and of the exegetical ritual texts. Bráhman- has been the subject of several searching studies by eminent 20th century Vedicists, e.g. Renou and Silburn 1949, Gonda 1950, Thieme 1952, Schmidt 1968. Philological examination of the gvedic passages seems especially to support the view of Thieme that bráhman refers originally to a "formulation" (Formulierung), the capturing in words of a significant and non-self-evident truth.66 The ability to formulate such truths gives the formulator (brahmán-) special powers, which can be exercised even in cosmic forces (see Jamison, 1991, on Atri). This power attributed to a correctly stated truth is found in the (later) "*satyakriyå" or 'act of truth', seminally discussed by W. Norman Brown (1941, 1963, 1968), which is in fact already found in the RV and has counterparts in other Indo-European cultures (see e.g. Watkins 1979). Such formulated speech (bráhman) must be recited correctly, otherwise there is danger of losing one's head (as explained in the indraśatru legend TS 2.4.12.1, ŚB 1.6.3.8), and it must be recited with its author's name.

[above regards early vedic, below regards middle vedic]

So, it is clear that the elevation of the ritual in the middle Vedic period has affected every aspect of the religious and a large section of the social realm. In turn, the new power of the ritual derives from the strengthening of the system of identifications we discussed briefly above. The ritual ground is the mesocosm in which the macrocosm can be controlled. Objects and positions in the ritual ground have exact counterparts in both the human (i.e. microcosmic) realm and the cosmic realm -- e.g. a piece of gold can stand for wealth among men and the sun in the divine world. The recognition of these bonds of identification -- many of which are far less obvious than the example just given -- is a central intellectual and theological enterprise, the continuation of the 'formulation of mythical truths' discussed above. The universe can be viewed as a rich and often esoteric system of homologies, and the assemblage, manipulation, and apostrophizing of homologues in the delimited ritual arena allows men to exert control over their apparently unruly correspondents outside it. This "ritual science" is based on the strictly logical application of the rule of cause and effect, even though the initial proposition in an argument of this sort ("the sun is gold") is something that we would not accept.69 Ritual Science received a seminal discussion by Oldenberg 1919 and also by Schayer 1925 and has frequently been treated since, e.g. in the most recent extensive treatment by B. K. Smith 1989; for references to other lit., see Smith 1986 : 95, n. 44.70

Vedic Hinduism, Witzel and Jamison

"the formulation of significant and non-obvious truths via the drawing of connections" is a natural category to me. obviously cf say, kabblah, but also the use of clever mappings between disparate objects in math

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023 In Books!

Due to mild fatigue, 2023 was a bad reading year for me - I did not reach my yearly 2-books-a-week goal for the first time since I began logging them, and many of the books I did read did not agree with me. But I still found ten fiction and 7 (!) non-fiction books I had to shout out for the end of the year.

Top 10 Fiction THE RED PALACE by June Hur A historical murder mystery set in Joseon Korea, featuring crystalline prose, a painstakingly evoked historical setting, and an understated romance in a dark atmosphere of terror, secrets, and palace intrigue. Despite being written for a young adult audience, this book impressed me with its complex picture of a deeply flawed real historical context.

TOOTH AND CLAW by Jo Walton A Victorian style comedy of manners in which every single character is a dragon, from the dragon parsons and spirited young lady dragons to the crotchety old dragon dowagers and feckless young dragons-about-town. All of them wear little hats. Sheer cosy perfection.

DRAKE HALL by Christina Baehr My bestie surprised me this year by spontaneously producing four whole novels pitched as "cosy Victorian gothic, with dragons". I haven't read the final edition of DRAKE HALL yet but it's sunshiney, summery, cosy goodness. With dragons.

CRIMSON BOUND by Rosamund Hodge (re-read) A dark and bloody fantasy full of lifegiving female friendship, ride or die siblings, theology, guilt, and stabbings. This one also contains gratuitous St Augustine quotes, a one-page retelling of the VOLUNDARKVIDA, and a love triangle that exists to present the heroine not so much with drama as a proper ethical dilemma.

EMILY WILDE'S ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF FAERIES by Heather Fawcett The story of a mildly autistic lady academic researching faeries with her flamboyant rival professor, who is probably secretly an exiled fae king…but the annoying part is his habit of making his students do all his field work. Cosy, thrilling, hilarious.

THE LAST TALE OF THE FLOWER BRIDE by Roshani Chokshi This gothic-infused psychological thriller was dark, creepy, and sometimes heavy, but it's also a tale that flips the roles of innocent maiden and Bluebeard, engages in valid Susan Pevensie Discourse, and ends on what I found to be a genuine note of hope and healing.

THE COLDEST GIRL IN COLDTOWN by Holly Black This book tackles vampirism as a metaphor for the evil hidden in the human heart, and it's epic, bloody, twisty, and monstrous. I couldn't put it down. Not sure I'd recommend it for the target audience, but it's mature and well-crafted enough to be enjoyed by grown-ups as well.

THE WITCHWOOD KNOT by Olivia Atwater I've read a number of Olivia Atwater books, and this one is head and shoulders above the rest. The best blend of gothic and fae, like a grown-up LABYRINTH, with one of the great fae butlers and so many subtle yet walloping feels. It felt like an old fairytale in the best possible way.

BEHIND THE CURTAIN by WR Gingell The WORLDS BEHIND series is about trauma and healing and repentance, and in this, the fourth book, everything comes decisively to the boil as our favourite twisty knife uncle pits his wits against an enemy who very uncomfortably mirrors himself.

Top 7 Non-Fiction (because I couldn't get it down to just five)

TWO VIEWS ON WOMEN IN MINISTRY by Beck & Gundry (eds.) Four New Testament scholars from a range of complementarian and egalitarian perspectives debate the question of women in ministry, with a lot of detailed scholarship. If nothing else, this book proved that this is something orthodox Christians can honestly disagree about, because there are significant exegetical strengths and difficulties with each position - it's time to stop seeing women holding ministry positions in the church as tantamount to heresy.

REFLECTIONS: ON THE MAGIC OF WRITING by Dianna Wynne Jones This collection was magical - funny and sad tales of her life, many good and passionate thoughts on books and writing, and one absolutely marvellous study of narrative structure in THE LORD OF THE RINGS. Absolutely delightful and highly recommended.

PATERNAL TYRANNY by Arcangela Tarabotti A 17th-century nun takes aim at the misogyny of early modern Europe, wielding razor-sharp logic to argue boldly for the equality of women. But it's Tarabotti's passionate faith, which somehow managed to survive moral injury and spiritual abuse, and even came to see hope and encouragement in scriptures which must so often have been used against her, that will stay with me.

THE GOLDEN RHINOCEROS: HISTORIES OF THE AFRICAN MIDDLE AGES by Francois-Xavier Fauvelle A series of bite-sized essays on the medieval history of Africa from approximately the Islamic conquests of the 7th century to the arrival of Portugese colonists in the fifteenth. Each essay offers the most fleeting glimpse of a long-vanished, half-imaginary world of often breathtaking sophistication and splendour. I loved them.

ONE HOLY LOCAL CHURCH? by Bojidar Marinov This short book, which draws very solidly on past luminaries like Rutherford, Gillespie, Spurgeon, and Hodge, helped me think through some of the questions I've been asking myself about ecclesiology and the role and authority of elders, particularly as I've been rethinking women in ministry. Terrific.

TEN DAYS IN A MAD-HOUSE by Nellie Bly "People on charity should not expect anything and should not complain." In 1887, the American "girl reporter" Nellie Bly got herself locked up in a New York lunatic asylum, and this shocking expose was the result. Sometimes, nineteenth century attitudes towards women and the poor were beyond parody.

A PEOPLE'S TRAGEDY: THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION, 1891-1924 by Orlando Figes Some aspects of this book have aged poorly - the unthinking acceptance of Russian imperial aspirations, for instance - but apart from that, this is a sweeping, epic picture of the Russian Revolution, covering three decades and every level of society, from daily life in the village commune to the political rivalries of Lenin's declining years, without ever becoming dull or bogged down in detail.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eli Kittim: New Testament Exegete

Kittim’s Eschatology: The Kittim Method

Eli of Kittim is the author of the award-winning book The Little Book of Revelation: The First Coming of Jesus at the End of Days, and a former contributor to the Journal of Higher Criticism, and Rapture Ready, which has published work by Billy Crone, David Reagan, Jan Markell, Thomas Ice, Thomas Horn, Bill Salus, Jonathan Cahn, Randall Price, John McTernan, Tim LaHaye, Ron Rhodes, Renald Showers, & Paul McGuire.

Eli of Kittim’s work is grounded on the original language of the New Testament. It pulls the rug from under a great deal of what passes for scholarship these days. But his work is also based on a revelation from Mount Sinai! So, it is both inspired and scholarly. According to Kittim, a view must be based on revelation, with scholarship added. Otherwise it is grounded on guesswork and conjecture.

Eli Kittim’s conclusion that the New Testament is essentially a collection of prophecies which will culminate in the last days, rather than a record of past events, is groundbreaking, challenging the hermeneutical assumptions of the status quo! It deserves serious consideration, otherwise we’re either dealing with consensus theology or downright academic dishonesty.

To examine his evidence (The Kittim Method), see the following materials:

1). What if the crucifixion of Christ is a future event? (Video)

This is based on translation and exegesis of the Greek New Testament

youtube

2). When is the end of the age? (Article)

This is based on word studies of parallel passages and verbal agreements in the New Testament

#the little book of revelation#TheFirstComingofJesusattheEndofDays#KittimEschatology#TheKittimMethod#NewTestamentExegete#TheLittleBook#ελικιτίμ#ΤοΜικροΒιβλιοΤηςΑποκαλυψης#theendoftheage#bible translation#WhatifthecrucifixionofChristisafutureevent#wordstudies#NewTestamentexegesis#ek#GreekNewTestament#koine greek#biblicalinterpretation#author#specialrevelation#scholarly research#goodreads#rapture ready#EliofKittim#journalofhighercriticism#bible prophecy#end times#last days#elikittim#BiographizingtheEschaton#the Kittimian view

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perhaps one is gradually, but not without difficulty, getting rid of a great allegorical distrust. By that I mean the simple idea, with regard to a text, that consists in asking oneself nothing else but what that text is really saying underneath what it is actually saying. No doubt, that is the legacy of an ancient exegetical tradition: concerning anything that is said, we suspect that something else is being said. The secular version of this allegorical distrust had the effect of assigning to every commentator the task of recovering the author's true thought everywhere, what he had said without saying it, meant to say without being able to, meant to conceal and yet allowed to appear. It is clear that today there are many other possible ways of dealing with language. Thus contemporary criticism — and this is what differentiates it from what was still being done quite recently — is formulating a sort of new combinative scheme [combinatoire] with regard to the diverse texts that it studies, its object texts. Instead of reconstituting the immanent secret, it treats the text as a set of elements (words, metaphors, literary forms, groups of narratives) among which one can bring out absolutely new relations, insofar as they have not been controlled by the writer's design and are made possible only by the work itself as such. The formal relations that one discovers in this way were not present in anyone's mind; they don't constitute the latent content of the statements, their indiscreet secret. They are a construction, but an accurate construction provided that the relations described can actually be assigned to the material treated. We've learned to place people's words in relationships that are still unformulated, said by us for the first time, and yet objectively accurate.

From a 1967 interview with Michel Foucault, "On the Ways of Writing History"

Another one for the "generative AI is reinventing structuralism" file. Implied here is that the underlying structure of language expresses an "accuracy" regardless of the facticity of an specific statement generated through that structure. Foucault calls it the "abandoning of the great myth of interiority." In AI terms, that means there doesn't need to be an intention for the discourse it produces to have meaning.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is difficult, of course, to judge the emotional tone, the intensity of the terror which the medieval Jew experienced in braving such a demon-ridden world. Our sources are wholly impersonal; writing of an introspective nature was altogether unknown. We can only conjecture on the basis of the chance personal comments that wormed their way quite incidentally into a literature which was primarily legalistic and exegetical. It is significant, for instance, that a homely little book like the Yiddish Brantspiegel, intended for the intimate instruction of womenfolk, a book which certainly came closer to the folk psyche than did the more formal writing of the period, singled out as the foremost dangers to life and limb demons, evil spirits, wild animals and evil men.

Joshua Trachtenberg, Jewish Magic and Superstition: A Study in Folk Religion; Man and the Demons: Attack

#jewish magic and superstition#joshua trachtenberg#sheydim#jewish magic and superstition; a study in folk religion#man and the demons

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

ABHINAVAGUPTA

"Abhinavagupta (c. 950 – 1016 AD) was a philosopher, mystic and aesthetician from Kashmir. He was also considered an influential musician, poet, dramatist, exegete, theologian, and logician – a polymathic personality who exercised strong influences on Indian culture.

He was born in Kashmir in a family of scholars and mystics and studied all the schools of philosophy and art of his time under the guidance of as many as fifteen (or more) teachers and gurus. In his long life he completed over 35 works, the largest and most famous of which is Tantrāloka, an encyclopaedic treatise on all the philosophical and practical aspects of Kaula and Trika (known today as Kashmir Shaivism). Another one of his very important contributions was in the field of philosophy of aesthetics with his famous Abhinavabhāratī commentary of Nāṭyaśāstra of Bharata Muni.

Life

"Abhinavagupta" was not his real name, rather a title he earned from his master, carrying a meaning of "competence and authoritativeness". In his analysis, Jayaratha (1150–1200 AD) – who was Abhinavagupta's most important commentator – also reveals three more meanings: "being ever vigilant", "being present everywhere" and "protected by praises".Raniero Gnoli, the only Sanskrit scholar who completed a translation of Tantrāloka in a European language, mentions that "Abhinava" also means "new", as a reference to the ever-new creative force of his mystical experience.

From Jayaratha, we learn that Abhinavagupta was in possession of all the six qualities required for the recipients of the tremendous level of śaktipāta, as described in the sacred texts (Śrīpūrvaśāstra):] an unflinching faith in God, realisation of mantras, control over objective principles (referring to the 36 tattvas), successful conclusion of all the activities undertaken, poetic creativity and spontaneous knowledge of all disciplines.

Abhinavagupta's creation is well equilibrated between the branches of the triad (Trika): will (icchā), knowledge (jñāna), action (kriyā); his works also include devotional songs, academical/philosophical works and works describing ritual/yogic practices.

As an author, he is considered a systematiser of the philosophical thought. He reconstructed, rationalised and orchestrated the philosophical knowledge into a more coherent form, assessing all the available sources of his time, not unlike a modern scientific researcher of Indology.

Various contemporary scholars have characterised Abhinavagupta as a "brilliant scholar and saint","the pinnacle of the development of Kasmir Śaivism"] and "in possession of yogic realization".

Social background, family and disciples

"Magical" birth

The term by which Abhinavagupta himself defines his origin is "yoginībhū", 'born of a yoginī'. In Kashmir Shaivism and especially in Kaula it is considered that a progeny of parents "established in the divine essence of Bhairava", is endowed with exceptional spiritual and intellectual prowess. Such a child is supposed to be "the depository of knowledge", who "even as a child in the womb, has the form of Shiva", to enumerate but a few of the classical attributes of his kind.

Parents

His mother, Vimalā (Vimalakalā) died when Abhinavagupta was just two years old; as a consequence of losing his mother, of whom he was reportedly very attached, he grew more distant from worldly life and focused all the more on spiritual endeavour.

The father, Narasiṃha Gupta, after his wife's death favoured an ascetic lifestyle, while raising his three children. He had a cultivated mind and a heart "outstandingly adorned with devotion to Mahesvara (Shiva)" (in Abhinavagupta's own words). He was Abhinavagupta's first teacher, instructing him in grammar, logic and literature.

Family

Abhinavagupta had a brother and a sister. The brother, Manoratha, was a well-versed devotee of Shiva. His sister, Ambā (probable name, according to Navjivan Rastogi), devoted herself to worship after the death of her husband in late life.

His cousin Karṇa demonstrated even from his youth that he grasped the essence of Śaivism and was detached of the world. His wife was presumably Abhinavagupta's older sister Ambā, who looked with reverence upon her illustrious brother. Ambā and Karṇa had a son, Yogeśvaridatta, who was precociously talented in yoga](yogeśvar implies "lord of yoga").

Abhinavagupta also mentions his disciple Rāmadeva as faithfully devoted to scriptural study and serving his master. Another cousin was Kṣema, possibly the same as Abhinavagupta's illustrious disciple Kṣemarāja. Mandra, a childhood friend of Karṇa, was their host in a suburban residence; he was not only rich and in possession of a pleasing personality, but also equally learned. And last but not least, Vatasikā, Mandra's aunt, who got a special mention from Abhinavagupta for caring for him with exceptional dedication and concern; to express his gratitude, Abhinavagupta declared that Vatasikā deserved the credit for the successful completion of his work.

The emerging picture here is that Abhinavagupta lived in a nurturing and protected environment, where his creative energies got all the support they required. Everyone around him was filled with spiritual fervor and had taken Abhinavagupta as their spiritual master. Such a supporting group of family and friends was equally necessary as his personal qualities of genius, to complete a work of the magnitude of Tantrāloka.

Ancestors

By Abhinavagupta's own account, his most remote known ancestor was called Atrigupta, born in Madhyadeśa: [Manusmirti (circa 1500 BC, 2/21) defines the Madhyadesh region as vast plains between Himalaya and Vindhya mountains and to the east of the river Vinasana (invisible Saraswati) and to the west of Praya]. Born in Madhyadeśa he travelled to Kashmir at the request of the king Lalitāditya, around year 740 CE

Masters

Abhinavagupta is famous for his voracious thirst for knowledge. To study he took many teachers (as many as 15), both mystical philosophers and scholars. He approached Vaiṣṇavas, Buddhists, Śiddhānta Śaivists and the Trika scholars.

Among the most prominent of his teachers, he enumerates four. Vāmanātha who instructed him in dualistic Śaivism and Bhūtirāja in the dualist/nondualist school. Besides being the teacher of the famous Abhinavagupta, Bhūtirāja was also the father of two eminent scholars.

Lakṣmaṇagupta, a direct disciple of Utpaladeva, in the lineage of Trayambaka, was highly respected by Abhinavagupta and taught him all the schools of monistic thought : Krama, Trika and Pratyabhijña (except Kula).

Śambhunātha taught him the fourth school (Ardha-trayambaka). This school is in fact Kaula, and it was emanated from Trayambaka's daughter.

For Abhinavagupta, Śambhunātha was the most admired guru. Describing the greatness of his master, he compared Śambhunātha with the Sun, in his power to dispel ignorance from the heart, and, in another place, with "the Moon shining over the ocean of Trika knowledge".

Abhinavagupta received Kaula initiation through Śambhunāthas wife (acting as a dūtī or conduit). The energy of this initiation is transmitted and sublimated into the heart and finally into

consciousness. Such a method is difficult but very rapid and is reserved for those who shed their mental limitations and are pure.

It was Śambhunātha who requested of him to write Tantrāloka. As guru, he had a profound influence in the structure of Tantrāloka and in the life of its creator, Abhinavagupta.

As many as twelve more of his principal teachers are enumerated by name but without details. It is believed that Abhinavagupta had more secondary teachers. Moreover, during his life he had accumulated a large number of texts from which he quoted in his magnum opus, in his desire to create a synthetic, all-inclusive system, where the contrasts of different scriptures could be resolved by integration into a superior perspective.

Lifestyle

Abhinavagupta remained unmarried all his life, and as an adept of Kaula, at least initially maintained brahmacharya and supposedly used the vital force of his energy (ojas) to deepen his understanding of the spiritual nervous system he outlined in his works—a system involving ritual union between Purusha as (Shiva) and Shakti. Such union is essentially non-physical and universal, and thus Abhinavagupta conceived himself as always in communion with Shiva-Shakti. In the context of his life and teachings, Abhinavagupta parallels Shiva as both ascetic and enjoyer.

He studied assiduously at least until the age of 30 or 35, To accomplish that he travelled, mostly inside Kashmir. By his own testimony, he had attained spiritual liberation through his Kaula practice, under the guidance of his most admired master, Śambhunātha.

He lived in his home (functioning as an ashram) with his family members and disciples, and he did not become a wandering monk, nor did he take on the regular duties of his family, but lived out his life as a writer and a teacher. His personality was described as a living realisation of his vision.

In an epoch pen-painting he is depicted seated in Virasana, surrounded by devoted disciples and family, performing a kind of trance-inducing music at veena while dictating verses of Tantrāloka to one of his attendees – behind him two dūtī (women yogi) waiting on him. A legend about the moment of his death (placed somewhere between 1015 and 1025, depending on the source), says that he took with him 1,200 disciples and marched off to a cave (the Bhairava Cave, an actual place known to this day), reciting his poem Bhairava-stava, a devotional work. They were never to be seen again, supposedly translating together into the spiritual world.

Works

Abhinavagupta's works fall into multiple sections: manuals of religious ritual, devotional songs, philosophical works and philosophy of aesthetics. Here are enumerated most of his works.

Religious works

Tantraloka

His most important work was Tantrāloka,(translates into "To Throw Light on Tantra"), a synthesis of all the Trika system. Its only complete translation in a European language – Italian – is credited to Raniero Gnoli, now at its second edition. The esoteric chapter 29 on the Kaula ritual was translated in English together with Jayaratha's commentary by John R. Dupuche, Rev. Dr. A complex study on the context, authors, contents and references of Tantrāloka was published by Navjivan Rastogi, Prof. of the Lucknow University. Though there are no English translations of Tantrāloka to date, the last recognized master of the oral tradition of Kashmir Shaivism, Swami Lakshman Joo, gave a condensed version of the important philosophical chapters of ‘‘Tantrāloka’‘ in his book, Kashmir Shaivism – The Secret Supreme.

Another important text was the commentary on Parātrīśikā, Parātrīśikāvivaraṇa, detailing the signification of the phonematic energies and their two sequential ordering systems, Mātṛkā and Mālinī. This was the last great translation project of Jaideva Singh.

Tantrasara

Tantrasara

Tantrasāra ("Essence of Tantra") is a summarised version, in prose, of Tantrāloka, which was once more summarised in Tantroccaya, and finally presented in a very short summary form under the name of Tantravaṭadhānikā – the "Seed of Tantra".

Pūrvapañcikā was a commentary of Pūrvatantra, alias Mālinīvijaya Tantra, lost to this day. Mālinīvijayā-varttika("Commentary on Mālinīvijaya") is a versified commentary on Mālinīvijaya Tantra's first verse. Kramakeli, "Krama's Play" was a commentary of Kramastotra, now lost. Bhagavadgītārtha-saṃgraha which translates "Commentary on Bhagavad Gita" has now an English translation by Boris Marjanovic.]

Other religious works are: Parātrīśikā-laghuvṛtti, "A Short Commentary on Parātrīśikā", Paryantapañcāśīkā ("Fifty Verses on the Ultimate Reality"), Rahasyapañcadaśikā ("Fifteen Verses on the Mystical Doctrine"), Laghvī prakriyā ("Short Ceremony"), Devīstotravivaraṇa ("Commentary on the Hymn to Devi") and Paramārthasāra ("Essence of the Supreme Reality").

Devotional hymns

Abhinavagupta has composed a number of devotional poems, most of which have been translated into French by Lilian Silburn:

• Bodhapañcadaśikā – "Fifteen Verses on Consciousness";

• Paramārthacarcā – "Discussion on the Supreme Reality";

• Anubhavanivedana – "Tribute of the Inner Experience";

• Anuttarāṣṭikā – "Eight Verses on Anuttara";

• Krama-stotra – an hymn, different from the fundamental text of the Krama school;

• Bhairava-stava – "Hymn to Bhairava";

• Dehasthadevatācakra-stotra – "Hymn to the Wheel of Divinities that Live in the Body";

• Paramārthadvādaśikā – "Twelve Verses on the Supreme Reality" and

• Mahopadeśa-viṃśatikā – "Twenty Verses on the Great Teaching".

• Another poem Śivaśaktyavinābhāva-stotra – "Hymn on the Inseparability of Shiva and Shakti" was lost.

Philosophical works

One of the most important works of Abhinavagupta is Īśvarapratyabhijñā-vimarśini ("Commentary to the Verses on the Recognition of the Lord") and Īśvarapratyabhijñā-vivṛti-vimarśini ("Commentary on the explanation of Īśvarapratyabhijñā"). This treatise is fundamental in the transmission of the Pratyabhijña school (the branch of Kashmir Shaivism based on direct recognition of the Lord) to our days. Another commentary on a Pratyabhijña work – Śivadṛṣtyā-locana ("Light on Śivadṛṣṭi") – is now lost. Another lost commentary is Padārthapraveśa-nirṇaya-ṭīkā and Prakīrṇkavivaraṇa ("Comment on the Notebook") referring to the third chapter of Vākyapadīya of Bhartrihari. Two more philosophical texts of Abhinavagupta are Kathāmukha-tilaka("Ornament of the Face of Discourses") and Bhedavāda-vidāraṇa ("Confrontation of the Dualist Thesis"). Abhinavagupta's thought was strongly influenced by Buddhist logic.

Poetical and dramatic works

Abhinavabharati

Abhinavaguptas most important work on the philosophy of art is Abhinavabhāratī – a long and complex commentary on Natya Shastra of Bharata Muni. This work has been one of the most important factors contributing to Abhinavagupta's fame up until present day. His most important contribution was that to the theory of rasa(aesthetic savour).

Other poetical works include: Ghaṭa-karpara-kulaka-vivṛti, a commentary on "Ghaṭakarpara" of Kalidasa; Kāvyakauṭukavivaraṇa, a "Commentary to the Wonder of Poetry" (a work of Bhaṭṭa Tauta), now lost; and Dhvanyālokalocana, "Illustration of Dhvanyāloka", which is a famous work of Anandavardhana."

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

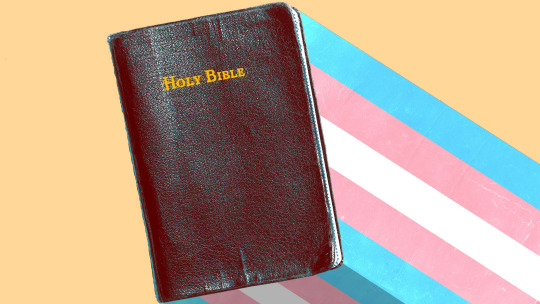

Galatians 3:28 is Transgender Affirming, Actually

An exegetical exploration of the text

I used to be a pastor. That occupation affords a position as a lot of things within the church, an opportunity to be “all things to all people” as Paul would say. 1 Perhaps the one that I was most well suited to and excelled at was being the neighborhood theologian in residence and academic in practice. Now that I am an academic full-time in my graduate studies, I am practically drowning in research, but remarkably, little of it is explicitly biblical in nature. This is something I quite miss, and so I began this blog partly to fill that missing piece of my former life, because I believe that as a Christian, drinking deep from the well of scripture is generally good practice and ideal to work towards.

So, call me surprised when a few weeks ago, I heard a murmur of a discourse on the site formerly known as Twitter, discourse revolving around Galatians 3, specifically Galatians 3: 28: “There is no longer Jew or Greek; there is no longer slave or free; there is no longer male and female, for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.”

Now, let me say this up front: this passage has meant a lot to me most of my life. It is a message that is designed to unify, to build community, to embolden us to set aside differences for the common good of the Christian community. But also, it has meant a lot to me personally, as it signaled to me that God simply does not regard my being transgender as something to be used against me, that in the end it does not matter to God, because God is beyond all of the binaries and dividing lines we might draw here on earth.

However, this is not exactly consensus. (Not that Twitter is at all an engine for consensus-building—in fact it was engineered to be the opposite!) For every person who argued that Galatians 3:28 was an affirming passage as regards people of the transgender experience, there were perhaps dozens more who said that interpreting it that was robs the passage of its context, and goes against the sacred word of Paul of Tarsus.2

This naturally got my pastor engine burning, because to me, it seems obvious, even with context, that Galatians 3 would be affirming for transgender people. Yet, most likely, there are many that would not see it so. Therefore, allow me to make my case for a queer, trans reading of Galatians 3.

(Note: though I am a trained pastor and theologian, I am NOT an expert in New Testament studies or biblical Greek. Additionally, though I am a queer theologian, Queer Theology as an area of

focus is not my exact specialty, not as much as disability or ethics is. This is my own exegesis and interpretation, make of that as you will.)

The Text in Context

Paul’s Letter to the Galatians is a text with a fraught history, which makes sense considering the letter was written to a problematic church. If Paul was going to write to a church, there was usually a significant enough problem at stake for the foundling churches of Asia. Moreover, if the letter was to be included within biblical canon, it meant that the issue was significant enough for the leaders of early church to have found it essential for the spiritual formation of the church itself. That issue was nothing less than a question of inclusion and discrimination within the church.

Paul was faced with the question: Who is to be included within the church? Who is to be given salvation? It’s a soteriological question with social implications, and to erase the second facet is to do a disservice to the first facet. Paul relates as much in his discussion in earlier chapters regarding his disagreement with Peter, Cephas, and James. To be a follower of Christ, did one need to be a Jew first? They had agreed, and sent Paul with their blessing, that the correct answer is no. One did not need to be a Jew in order to be saved through the redeeming work of Jesus Christ. One could be a Gentile or a Jew, and this pivotal decision set in motion the course of the church for the rest of history, one which would ultimately spell final division with our Jewish siblings.

But I digress. The point was, there was confusion among the church as to who was included in the family of God, and Paul emphatically declared in Galatians that this entire line of questioning was out of order. Paul was of course chiefly focused on the Jewish/Gentile divide, but he was not blind to the hierarchical realities of the society in which he lived. The statement he makes in 3:28 is a threefold formulation, one that approaches the chief dividing lines in society as he saw it: Jew and Gentile, slave and free, male and female.3 This entire letter was birthed by inequality and division occurring socially4, and Christian communities are reflections of their societies and communities. Jim Reiher puts it like this: “...human ‘horizontal’ relationships were not reflecting the ‘vertical’ equality we all have in Christ with God.”

Thus, in response to these divisions among the people of the church, Paul’s response is that it is in the waters of baptism in Jesus Christ that we are given common salvation. Jennifer Slater states that in a post-Christ paradigm, “both men and women share equally in Christ and so become equal members or participants of the Kingdom of Jesus Christ.”5 This is not in ignorance of the realities of division, nor a collapse of identity. People remain distinct, and so do identities within the church. To ignore such would

be to ignore reality. Rather, it’s instead not a dissolution of distinction, but rather a negation of difference as a basis for exclusion. 6

In Paul’s day, and in ours, it would be the height of foolishness to state that difference did not exist. Yet despite that, we as the church are called to not necessarily bless the structures that divide us in our society, but reflect a different reality in which those differences do not deny any of us citizenship in the Reign of God through Jesus Christ. Christ did away with those when he took on human flesh and was resurrected from the dead. When we undergo the waters of baptism, we are initiated into that reign, that new reality, and offered salvation through faith.

That Paul knew what he was doing here seems obvious. There was a very strict codification of gender binary within Roman society in that time, with a clear advantage given to men over women. Women had less social status than men, often could not hold property, and even were seen as property of men in every arena. To state “there is neither male nor female” is a direct contradiction of the social order as it stood, and different gender roles were proscribed by society. As such, this disregarding of gender as it affects life in the church is a radical statement indeed, and thus worthy of modern interrogation.

Queering the Text

This is, of course, where the fun begins. I needed to get through that background to get to the question at hand: how is Galatians 3:28 a trans affirming passage?

I am going to state here that queer theory and queer criticism is a relatively new field of criticism, doubly so for theology. Though the interrogation of the text as a gender-inclusive statement can be seen to go back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, queerness as a subcategory of theology can only go back a few decades. Therefore, the scholarship is scant on the matter of Galatians 3:28, but not impossible to find. For a more in-depth analysis, I’ll recommend an excellent paper by Jeremy Punt, full citation in the footnotes.7 His work is excellent, yet it is mostly focused on establishing a basis for a queer reading of Galatians 3, not as much the specific queerness that being transgender poses.

In claiming that in Christ there is “no male nor female,” there is an androgynizing effect to the passage that poses a danger to the male audience, much more than the female one.8 Men stood to lose much in the categorical collapse of gender: social status, privilege, and legal rights. In the bargain, women stood to gain much more than men would lose, and thus this was a radical proposal for 1st century church members. Yet, one could argue that this collapse was potentially less dangerous than the difference collapse between rich and poor, slave and free, and most especially for Paul’s interest, Jew and Gentile. The presence of salvation through the work of Jesus Christ was a radical proposition, and to separate social reality from soteriological would be folly, especially since the social aspect seemed to be the chief problem that was being posed to salvation.

This naturally leads to a significant question for the interpreter: what do we mean by salvation? Is salvation simply something that happens in the great by and by? Is it simply a reality relegated to existence after death? Or does salvation mean something in the present, the here and now? I would argue that for Paul, it absolutely matters. Salvation was a social issue, because the material reality with which the church was faced was affecting their theological prejudices and division. Thus, when Jesus saves, Jesus does not simply save us for later, but saves us right now. When he first speaks in the Gospel of Mark, Jesus says “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news.”9 That’s not a promise of the reign in the future, in some far away time or place that is immediate and urgent. Thus, salvation only makes sense if we frame it in the present, material reality of the listener.

Jeremy Punt wisely stated that “...queer theory is not so much about bestowing normalcy on queerness but rather queering of normalcy.”10 If one takes that task seriously, it is then a very queer thing indeed for Jesus to have proclaimed the arrival of the Reign of God. It very much queered the normalcy of the people he preached to, and Paul is very much queering the normalcy of the people of Galatia in this broad, unifying pronouncement. He is blurring the divisions between ethnic groups, economic groups, as well as gender groups, something that is usually believed to have been an unreconcilable divide. After all, did God not create the two genders in the Garden of Eden? ”Male and female, he created them?” Yet in Christ, we see that this division need not be maintained so strictly, because the things of heaven, the Reign of God, does not seem to care about these divisions all that much.

The case for gender inclusion in Galatians seems straightforward, then. Women ought not be barred from anything within the church itself. The social dimension directly affects this salvation issue, and God is freeing us from division within salvation and society. But this leads to the crucial question:

Does this include transgender people?

The T-shaped Hole in our Text

Our beliefs and understanding about gender, sex, and the social constructs around them have changed in the intervening millennia between our us and our text. There was no way for Paul to have talked about what we now understand as transgender people, because that category did not exist for him in that context.

That does not mean that we did not exist back then, mind you. The existence of transgender people in history is being uncovered on a daily basis. Our journals, our records, our stories exist, but on the margins of social consciousness. The truth of the matter is, we did not simply appear in the last few years, when people started making more of a fuss about us in the public sphere. We simply have learned more about how gender works, and that is a concept and topic that is expanding each day. So, while Paul did not consider transgender people in his writing, that does not mean that we did not exist in his day and age, and that does not mean that this text doesn’t have something to say about us.

If one had to boil down the entire text of Galatians to a single point, it would be that our divisions do not stop us from receiving the love of God through Jesus Christ. Quite the reverse. Jesus

Christ does not care about our divisions. God’s love does not end at an arbitrary dividing wall of our own creation. That love is shared among God’s children equally; how could you make a holy parent like God choose among their creation? Likewise, God does not contain within themselves division. God may be triune in nature, but that triune aspect of God only heightens the communal aspect of love, and the love that God shares within God’s selves is only stronger when it is shared with God’s creation.

When I was a child, I was baptized into the life of the church. There is not a day that goes by where I did not know God’s love for me. It has been a constant throughout my life, and I cherish the fact that I have always had assurance of God’s love for me. God does not suddenly stop loving someone like me when I learn more about myself, about my mind, my identity, and my manner of expression. If, as Paul says, “There is no longer male and female,” then why get hung up on whether or not God’s love is extended to transgender people? You can hop that binary divided at any point, and God’s love for you would not change. You can ride that line all day long if you want! You may say, forget the line! Because the line is only there because we say it’s there.

In the end, male and female are simply categories, and if God is any indicator, categories are meant to be defied. God does not have a gender, because God is beyond the binary. God is beyond every binary, in fact. This isn’t a controversial statement, it simply has been the understanding of the church going back to antiquity. That we call God Father, Son, and Holy Spirit and use predominantly masculine pronouns is because of how language works, and how God through Jesus Christ revealed themselves to us. That is the language they used, but any language we use is provably lacking when talking about the divine, because it is a construct of human making, and therefore flawed and fallible. Our understanding of biology is simply what we have so far observed and tested, backed up on documentation, and is liable to change as more information is gathered. Furthermore, gender is different from biological sex, and while both are important—fascinating, even!--they are also more malleable than we might imagine.

Christians are also a people of change. We believe that Jesus came to change the world from how it is to how it will be under the Reign of God. Jesus calls us to repentance, to change ourselves, and be transformed by the love that God has for us. You are changing every day in small, unnoticeable ways. Transgender people are just people who have observed an interior discrepancy in how we are perceived by the world, and work to change that in our lives to better reflect the person that we always were inside. That’s not dishonesty or delusion, it is simply how humans work! It's the height of honesty to be transgender, because the most intimate part of ourselves, our identity, is important, and God honors that. Because of that, God does not really care if we transition. Because God shows no partiality. Man, woman, something in between, something outside the binary completely—there is no longer any division, because all are one in Christ our Lord. If you belong to Christ, you belong to the promise that God will always love you, no matter what.

Conclusion

To me, a theologian and one deeply called to teaching the truths of our faith, are deep truths that cannot be denied. Paul does not want there to be any division among us, as division only sows injustice, infighting, and chaos. Jesus came to both men and women, slave and free, rich or poor, Jew and Gentile. This is a text that is designed to free us from our interior divisions, to work towards a reality in which those divisions do not matter anymore.

The context of the text recognizes the social reality of our world, and then subverts it. The message of Jesus Christ, then, is a revolutionary attitude of inclusion, love, and support. It goes beyond gender divisions, to the very cores of our being. God loves us, God includes us, God celebrates us. God wants us to live in truth and love with one another—and being transgender is a truth that should not be denied.

Look, I have tried to deny it for decades. I tried to be what I was assigned at birth, and have found so much freedom in acknowledging the truth of who I am inside. Ask any transgender person, and they will tell you the same. If it could be denied, we wouldn’t be honest with ourselves, or with God. God wants us to be free, loved, and honored in our communities, especially in the church.

So yes, Galatians 3:28 is a transgender affirming text, actually. It is a text that unbinds us to binaries and reveals a vision of a community that has progressed beyond division to true unity, solidarity, and love. Go therefore and act like God has freed you from your interior divisions. Live in truth, and the truth shall set you free.

______________________________________________

Footnotes:

1- 1 Cor. 9:22 (NRSV).

2 -I quite like Paul, by the way! But he was a human being, and as a human being, his words bear the stain of human frailty and fallibility. Therefore, it is more than acceptable to criticize and/or examine his work as such. He was an excellent writer and theologian, and demands that his work be taken seriously as an academic; I imagine he would want nothing less

3- Slater, Jennifer. “'Inclusiveness’ - An Authentic Biblical Truth That Negates Distinctions: A Hermeneutic of Gender Incorporation and Ontological Equality in Ancient Christian Thought.” Journal of Early Christian History 5, no. 1 (2015): 116–31. Pg. 118.

4- Reiher, Jim. “Galatians 3: 28 – Liberating for Women’s Ministry? Or of Limited Application?” The Expository Times 123, no. 6 (March 1, 2012): 272–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014524611431773. Pg. 275.

5- Slater. Pg. 119.

6- Ibid. Pg. 122.

7- Punt, Jeremy. “Power and Liminality, Sex and Gender, and Gal 3:28: A Postcolonial, Queer Reading of an Influential Text.” Neotestamentica 44, no. 1 (2010): 140–66.

8- Punt. Pg. 154.

9- Mark 1: 15, NRSV.

10- Punt. Pg. 156.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maybe as a woman I can relish over the good food I made today AND discuss theology and exegete scripture and study the original languages. Maybe I can also enjoy studying the really cool lizard I found on my porch that changes colors. Maybe women are more than just 2D caricatures.

Just a thought.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The late Professor John Murray taught the significance of understanding the doctrine of definitive sanctification. As he studied the exegetical statements of the New Testament that spoke of believers having been sanctified through the death of Christ (e.g. 1 Corinthians 1:2; 6:11; Heb. 10:10, etc.), Murray suggested that “it is a fact too frequently overlooked...

4 notes

·

View notes