#ethiopian highlands

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis) resting on grass with flowering Rift Valley sage (Salvia merjamie) behind, Bale Mountains National Park, Ethiopia. The world's rarest species of wild canid, found only in the Ethiopian Highlands, fewer than 500 remain in the wild. Endangered. Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition 2023 People's Choice Award.

Photographer: Axel Gomille

#axel gomille#photographer#wildlife photographer of the year competition#ethiopian wolf#wolf#canis simensis#rift valley sage#salvia merjamie#bale mountains national park#ethiopia#animal#mammal#wildlife#nature#ethiopian highlands

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Qemant Judaism

Qemant Judaism refers to the traditional religious beliefs and practices of the Qemant people, an ethnoreligious group in northwestern Ethiopia, primarily located in the Amhara Region near Lake Tana. The Qemant religion has historically drawn the attention of scholars for its complex fusion of Hebraic elements, Cushitic traditions, and a unique local religious system that exhibits remarkable continuity with certain aspects of ancient Israelite religion, despite the community’s isolation and lack of written scripture.

Qemant religion, while related to Judaism in numerous aspects, is not Rabbinic and predates modern Jewish movements. It retains elements that some scholars argue may reflect a form of pre-Talmudic, possibly pre-Second Temple Hebraic tradition, influenced by and interwoven with indigenous African customs. As such, Qemant Judaism has long been considered a key to understanding the diversity of Jewish religious expression and the diffusion of Israelite traditions across Africa.

The Qemant are a small Cushitic-speaking group whose language, Qemantney or Agäw, is a dialect of the Agaw languages, which are a subgroup of the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic language family. The Agaw peoples are among the most ancient inhabitants of the Ethiopian Highlands and were historically influential in the region, particularly during the time of the Zagwe dynasty (c. 900–1270 CE), which claimed descent from Israelite heritage.

Historical accounts of the Qemant indicate a long-standing religious system with strong similarities to ancient Hebraic customs. The first substantial documentation of Qemant religion came through 19th- and early 20th-century European travelers and Ethiopian scholars, including the works of Wolf Leslau, who conducted extensive fieldwork in the mid-20th century. Their documentation reveals that the Qemant religious system developed independently of mainstream Rabbinic Judaism and of the Ethiopian Beta Israel (Falasha) Jewish community, though some contact and cross-influence likely occurred over time.

Qemant theology is monotheistic, centered on the worship of a single, omnipotent deity known as Yägzo (or Yägzo Amlak), which translates roughly as "the God of the Sky." This concept bears resemblance to the Hebrew concept of El Elyon (God Most High) and aligns with general Semitic monotheistic frameworks. Yägzo is believed to be omniscient, omnipresent, and morally sovereign.

The Qemant reject images and idols in worship, adhere to strict dietary laws, and observe ritual purity, all of which are reminiscent of ancient Israelite customs. However, their conception of God is not anthropomorphized, and their worship is largely abstract, expressed through prayer, sacrifice, and observance rather than via iconography or visual representation.

The Qemant religion does not rely on a written religious canon. Instead, it is entirely oral, with religious knowledge transmitted through a hereditary priesthood known as kǝmǝnt, which also designates the religious specialists and the broader ethnic-religious identity. These priests are responsible for preserving religious law, performing rituals, mediating disputes, and maintaining community moral standards.

Their oral tradition includes detailed accounts of creation, laws of conduct, genealogies, and ritual instructions. Some of these traditions parallel Old Testament narratives, including beliefs about the Flood, dietary restrictions, sacrificial rites, and the moral codes resembling the Ten Commandments, though the Qemant deny direct derivation from Jewish scripture. Instead, they assert a tradition passed down independently through the ages.

Qemant religious practice is highly ritualistic and closely tied to nature and seasonal cycles. They worship in sacred groves called däqqo, which function as natural temples. The trees and groves are treated with reverence, and no tree within the däqqo may be cut. Worship in the däqqo is conducted by the priests and involves hymns, prayers, and animal sacrifices.

Animal sacrifices are central to Qemant worship, especially during major festivals. The animals, usually sheep or goats, must be without blemish and are sacrificed according to strict purity laws. The blood is poured on stones, and the meat is consumed by the community, with portions reserved for the priests and the poor. The practice is reminiscent of the ancient Israelite Temple rituals described in the Torah.

A notable ritual is the Feast of the New Moon, observed monthly. During this observance, the Qemant community gathers in the däqqo, offers sacrifices, prays, and shares a communal meal. The day is considered holy, and no labor is allowed. Their calendar is lunar-based, similar to the Hebrew calendar.

The Qemant have a complex legal and moral system known as sǝratä mängǝst ("order of the kingdom"), which encompasses religious laws (halakhah-like codes), social norms, and ethical behavior. Laws are enforced by religious elders and priests and pertain to ritual cleanliness, marriage, dietary restrictions, and moral conduct.

Purity laws are rigorous: menstruating women, individuals who have touched corpses, and those who have eaten unclean food are considered ritually impure and must undergo prescribed purification rites, including ablution and periods of seclusion.

Dietary laws prohibit the consumption of pork, shellfish, and animals that do not have cloven hooves and chew cud. Animals must be slaughtered in a ritual manner. Blood consumption is strictly forbidden. Food preparation, storage, and mixing of meat and milk are regulated, though not in the exact manner as Rabbinic kashrut.

The religious leadership of the Qemant is organized in a hierarchical system, with the High Priest (abä gäräz) at the top, followed by other ranks of clergy responsible for individual villages or districts. Priests are male, and positions are usually hereditary, though piety, knowledge, and moral standing are also key criteria for advancement.

Priests serve as arbiters of law, educators, and officiants at religious events. They must remain in a constant state of ritual purity and are required to abstain from various forms of impurity. They also serve as spiritual mediators between the community and Yägzo.

The Qemant religious calendar includes several unique festivals, many of which align with agricultural cycles and lunar events. One of the most important is the Maari Festival, associated with the renewal of nature and community purification. During this festival, sacrifices are offered, debts are forgiven, and communal reconciliation is sought.

Another important observance is Tensae, a springtime celebration that coincides approximately with Passover, and involves rituals of renewal and liberation, although the Qemant do not link it explicitly to the Exodus narrative.

Weekly observance includes a Sabbath-like rest day called Sanbat, held on Saturday. Work is prohibited, and communal worship is held in the däqqo. This practice aligns with both Jewish and Ethiopian Orthodox traditions, though the Qemant Sabbath includes unique local customs and prayers.

The relationship between the Qemant and the Beta Israel is complex. While both groups share Hebraic features, they developed independently. The Beta Israel possess written scripture (a Ge’ez-based canon related to Jewish writings), and their practices are more aligned with Rabbinic norms, albeit with distinctive Ethiopian features. Nonetheless, some Qemant have historically been absorbed into the Beta Israel community, particularly during the 20th century, when religious distinctions became increasingly blurred.

The spread of Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity in the region has significantly impacted the Qemant. Over the centuries, many Qemant have converted, either voluntarily or under social and political pressure. This process has accelerated in the modern era, with a majority of Qemant now identifying as Christians, although often retaining elements of traditional belief, especially in rural areas.

Qemant religion is currently endangered. As of the 21st century, only a small fraction of the Qemant people continue to actively practice their ancestral religion. Many traditional rituals, especially sacrificial practices, have declined due to external pressures, including government restrictions, Christian missionary activity, and integration into broader Ethiopian society.

Nonetheless, there have been recent movements to preserve Qemant heritage. Cultural organizations, scholars, and international anthropologists have worked to document oral traditions, record rituals, and support cultural revival efforts. There have also been political movements among the Qemant to assert ethnic and religious identity in the context of Ethiopia's federal structure, which grants limited cultural autonomy to recognized ethnic groups.

Qemant Judaism has fascinated scholars of comparative religion, anthropology, and Hebraic studies due to its apparent preservation of archaic Hebraic elements. Some interpret the Qemant as representing a form of "African Israelite religion" that may predate the full codification of Rabbinic Judaism and reflect an older, decentralized, agrarian model of Israelite worship.

Others caution against drawing direct historical lines to ancient Israel, arguing that Qemant religion is better understood as a localized, indigenous religious system with selective Hebraic borrowing. Regardless of origin theories, there is consensus that the Qemant religious tradition is a rare and valuable repository of religious expression that intersects Semitic, Cushitic, and African spiritual frameworks.

Qemant Judaism represents one of the most unique and underexplored religious traditions in Africa. With its complex synthesis of monotheism, ritual purity, oral law, sacred ecology, and sacrificial worship, it challenges modern assumptions about the boundaries of Judaism and the transmission of religious ideas across cultures and time. Though the tradition is now in decline, it remains a vital subject of study for those interested in religious syncretism, African history, and the global diversity of Hebraic traditions.

#qemant#qemant judaism#ethiopia#african judaism#indigenous religion#religious history#cushitic peoples#agaw#beta israel#hebraic traditions#judaism in africa#ethiopian culture#ancient religions#monotheism#oral tradition#spiritual heritage#ethnography#cultural anthropology#afroasiatic#traditional beliefs#sacred groves#ethiopian highlands#african history#lost tribes#folk religion#historical judaism#sacred rituals#ethiopian religions#cultural preservation#forgotten faiths

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ethiopian Highlands

Photo: Amazing panorama of the Simien Mountains National Park in Ethiopia, Africa by Framalicious. Welcome to the mesmerizing world of Ethiopia’s Highlands, where nature’s grandeur takes center stage. In this enchanting mountain range, discover a realm of breathtaking beauty that will leave you in awe. From cascading waterfalls to ancient rock-hewn churches, the Ethiopian Highlands offer a…

View On WordPress

#Ethiopian Highlands#ethiopian highlands facts#ethiopian highlands location#ethiopian highlands mountain range#Ethiopian Highlands mountains

0 notes

Text

Spectember 2024 #04: Forest Gelada

Someone who identified themself only as Pendrew asked for a "ruminant-like Old World Monkey":

After much of East Africa rifted off into a separate continent, shifting climate turned the alpine grasslands of what was once the Ethiopian Highlands into into warmer subtropical forests – and the highly terrestrial grass-eating geladas that inhabited the region adapted to new sources of food.

Yedenigelada pendrewsii is a large quadrupedal herbivorous monkey, about 1.5m tall at the shoulder (~5'). It has a specialized pseudoruminant digestive system with a three-chambered stomach, similar to that of camelids, and it occupies an ecological niche convergent with the ancient chalicotheres, selectively browsing on trees and shrubs while sitting upright and using its long clawed forelimbs to pull branches within reach.

Unlike its highly social ancestors this species is mostly solitary, although during the breeding season groups of males come together in leks to compete for female attention. Displays consist of inflating large colorful throat pouches to make loud resonating calls, and flipping upper lips to bare teeth and gums.

#spectember#spectember 2024#speculative evolution#gelada#cercopithecidae#old world monkey#primate#mammal#art#science illustration

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illuminated Gospel—Amhara region, Ethiopia, late 14th to 15th century

Via the Met: "This illuminated manuscript of the Four Gospels was created at a monastic center in northern Ethiopia. Twenty full-page paintings depict scenes from the life of Christ and four portraits of the evangelists introduce the respective Gospel texts. The New Testament was translated from Greek into Geez, the classical language of Ethiopia, in the sixth century. Both this text and its pictorial format draw upon Byzantine prototypes, which were transformed into a local idiom of expression. Stylistically consistent, the paintings reflect the hands of two distinct artists. The color scheme consists of red, yellow, green, and blue. A stylized uniformity is reflected in the abbreviated definition of facial features and the bold linear articulation of the human form in black and red. Figures' heads are depicted frontally, their bodies often in profile. Bodies are treated as columnar masses encased in textiles composed of striated fields juxtaposed against one another.

This work is evidence of sub-Saharan Africa's historically complex interrelationships with Arabia, Egypt, and the eastern Mediterranean. The origins of civilization in Highlands Ethiopia can be traced to the sixth century B.C.E., when emigrants from Arabia merged with indigenous groups to develop the kingdom of Aksum. In the fourth century C.E., scholars from Alexandria converted the Ethiopian king Ezana, and Christianity became the official religion of a state that endured until modern times. Over the centuries, as the Ethiopian state expanded, monasteries were founded as centers of learning responsible for disseminating knowledge and consolidating the power and influence of the monarchy. In the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, the text of the Gospels was considered the most important holy writing; the miniatures at the beginning of this manuscript were intended to be viewed during liturgical processions. Such works were frequently presented to churches by distinguished patrons; they reflected both the prestige of royal benefactors and the erudition of the monastic scriptoria in which they were created. Recent research suggests that a member of Ethiopia's ruling elite may have commissioned this manuscript at Dabra Hayg Estifanos monastery for presentation to his or her favored church or monastery. Brief notations indicate that the church in question was dedicated to the Archangel Michael."

120 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kingdom of Abyssinia

The Kingdom of Abyssinia was founded in the 13th century CE and, transforming itself into the Ethiopian Empire via a series of military conquests, lasted until the 20th century CE. It was established by the kings of the Solomonid dynasty who, claiming descent from no less a figure than the Bible's King Solomon, would rule in an unbroken line throughout the state's long history. A Christian kingdom which spread the faith via military conquest and the establishment of churches and monasteries, its greatest threat came from the Muslim trading states of East Africa and southern Arabia and the migration of the Oromo people from the south. The combination of its rich Christian heritage, the cult of its emperors, and the geographical obstacles presented to invaders meant that the Ethiopian Empire would be one of only two African states never to be formally colonised by a European power.

Origins: Axum

The Ethiopian Highlands, with their reliable annual monsoon rainfall and fertile soil, had been successfully inhabited since the Stone Age. Agriculture and trade with Egypt, southern Arabia, and other African peoples ensured the rise of the powerful kingdom of Axum (also Aksum), which was founded in the 1st century CE. Flourishing from the 3rd to 6th century CE, and then surviving as a much smaller political entity into the 8th century CE, the Kingdom of Axum was the first sub-Saharan African state to officially adopt Christianity, c. 350 CE. Axum also created its own script, Ge'ez, which is still in use in Ethiopia today.

Across this Christian kingdom, churches were built, monasteries founded, and translations made of the Bible. The most important church was at Axum, the Church of Maryam Tsion, which, according to later Ethiopian medieval texts, housed the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark, meant to contain the original stone tablets of the Ten Commandments given by God to Moses, is supposed to be still there, but as nobody is ever allowed to see it, confirmation of its existence is difficult to achieve. The most important monastery in the Axum kingdom was at Debre Damo, founded by the 5th-century CE Byzantine ascetic Saint Aregawi, one of the celebrated Nine Saints who worked to spread Christianity in the region by establishing monasteries. The success of these endeavours meant that Christianity would continue to be practised in Ethiopia right into the 21st century CE.

The kingdom of Axum went into decline from the late 6th century CE, perhaps due to overuse of agricultural land, the incursion of western Bedja herders, and the increased competition for the Red Sea trade networks from Arab Muslims. The heartland of the Axum state shifted southwards while the city of Axum fared better than its namesake kingdom and has never lost its religious significance. In the 8th century CE, the Axumite port of Adulis was destroyed and the kingdom lost control of regional trade to the Muslims. It was the end of the state but not the culture.

Continue reading...

162 notes

·

View notes

Note

so interesting that armenians don't consider themselves european! i am a little uneducated on this topic, so i've never thought otherwise. i'm now gonna research this topic more, thank you. how would you say armenians determine themselves?

I’d like to start by saying that, for me, being considered Asian or European holds no inherent preference. My answer contains no malcontent; I am simply addressing the question as it's been posed. Interestingly, I had never thought of myself as European. I’ve always identified as Asian and as someone from the Caucasus.

I’ll explain my reasoning shortly, but first, let’s not confuse "Caucasian", meaning a person from the Caucasus, and the term "Caucasian" as coined by Blumenbach in his highly problematic racial theory. Many people use "Caucasian" to refer to white people (a surprise to me at first) without knowing the term’s problematic origins. Blumenbach categorized humanity into five groups—Caucasian, Mongolian, Malayan, Ethiopian, and American. His work was mostly scientific, but he showed bias by declaring the skull of a Georgian woman the “most handsome”, suggesting that the most beautiful people lived on the southern slopes of Mount Caucasus. He then made a leap by claiming that whiteness was the “primitive color of mankind”. This is how "Caucasian" became synonymous to "white" and this is why I find the use of "Caucasian" to mean white people so problematic. But, once again, when I call myself/Armenians Caucasian, it is because we are actually from Caucasus.

Armenians are indigenous to the Armenian Highlands, which are bordered by the Pontic Mountains to the north, the Caucasus Mountains to the northeast, the Zagros Mountains to the south, and the eastern Taurus Mountains to the west. This clearly places us in Western Asia, not Europe. Modern-day Armenia occupies only a small part of the historical Armenian Highlands, situated in the South Caucasus. So, in conclusion, as an Armenian, I don’t consider Armenians to be European.

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kingdom of Axum (Aksumite Empire): An In-Depth Analysis of Africa’s Lost Superpower

Introduction: Axum – The Forgotten African Empire

The Kingdom of Axum (Aksumite Empire) was one of the greatest African civilizations, yet its history remains largely unknown to many. Located in what is now modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea, Axum flourished between 100 BCE and 940 CE, becoming a powerful empire that dominated trade, politics, and culture in Africa, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean.

Axum was more than just a kingdom—it was a global superpower, rivalling the Roman Empire and the Persian Empire. It was one of the earliest African civilizations to develop advanced trade networks, coinage systems, and monumental architecture.

From a Garveyite perspective, the study of Axum is crucial because it proves that:

Black civilization existed at the highest levels long before European colonialism.

African nations were dominant players in global trade, economy, and military power.

Black leadership and governance were sophisticated and independent, not reliant on foreign intervention.

By reclaiming the history of Axum, Black people today can understand that our ancestors were not just victims of history—we were rulers, builders, and strategists.

1. The Origins of Axum: The Birth of an African Empire

A. Geographic and Strategic Location

Axum was located in the Horn of Africa, controlling trade routes between Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Indian Ocean.

It was surrounded by the Red Sea, the Nile River, and the highlands of Ethiopia, making it a natural hub for commerce and military defense.

Its fertile lands allowed for agriculture, livestock farming, and gold mining, ensuring a strong economy.

Example: The Ethiopian Highlands provided Axum with a natural fortress, making it difficult for invaders to conquer.

Key Takeaway: Axum was not an isolated kingdom—it was a central force in African and world history.

2. The Rise of Axum as a Global Trade Power

A. Axum’s Control Over International Trade

Axum controlled Red Sea trade routes, connecting Africa with the Middle East, India, and the Mediterranean.

It became one of the world’s first major exporters of gold, ivory, frankincense, myrrh, and exotic animals.

Axumite merchants traded with the Romans, Persians, Indians, and Arabs, making Axum one of the wealthiest states of its time.

Example: Roman and Greek historians described Axum as one of the four great world powers, alongside Rome, Persia, and China.

Key Takeaway: Black civilizations were not just local powers—they influenced global commerce and trade.

B. The Axumite Coinage System: Africa’s Early Banking System

Axum was one of the first African kingdoms to mint its own coins (gold, silver, and bronze).

These coins were used in trade with the Roman Empire, Arabia, and India, proving Axum’s economic dominance.

The coins often featured the images of Axumite kings, showcasing Black leadership and national identity.

Example: Axumite coins were found as far away as India and China, proving that African goods and culture travelled across the world.

Key Takeaway: Africa had a sophisticated economic system long before European colonization.

3. Axum’s Architectural and Cultural Achievements

A. The Obelisks of Axum: Africa’s Forgotten Monuments

Axum is home to some of the tallest ancient obelisks in the world, serving as monuments to Axumite kings.

These structures, carved from single blocks of granite, are over 100 feet tall and demonstrate advanced engineering skills.

The obelisks were used as royal tomb markers, showing the kingdom’s rich burial traditions.

Example: The Obelisk of Axum, stolen by Italy during its invasion in the 20th century, was only recently returned in 2005.

Key Takeaway: Black civilizations built monumental structures that rivalled those of Egypt and Rome.

B. The Architecture of Axumite Palaces and Temples

Axumite kings built grand palaces, temples, and underground tombs, many of which still stand today.

The city of Axum itself was a vast metropolis, filled with markets, administrative buildings, and places of worship.

Example: The Dungur Palace, often called the "Palace of the Queen of Sheba," is a massive Axumite structure showcasing the empire’s architectural brilliance.

Key Takeaway: Africa was home to urban centres and royal capitals long before European cities reached similar levels of sophistication.

4. The Religious Transformation of Axum

A. Axum’s Conversion to Christianity

Axum was one of the first major African states to convert to Christianity around 330 CE, under King Ezana.

Christianity became the official state religion, leading to the construction of churches, monasteries, and religious texts.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church, which traces its origins to Axum, remains one of the oldest Christian institutions in the world.

Example: The Church of St. Mary of Zion in Axum is believed to house the Ark of the Covenant, one of the most sacred relics in biblical history.

Key Takeaway: Christianity in Africa did not come from European missionaries—it was practised in Axum over 1,000 years before colonialism.

B. The Role of Axum in Early Islam

When Prophet Muhammad and his followers were persecuted in Mecca, they fled to Axum for protection.

The Axumite king, Negus (King Armah), granted them asylum, making Axum one of the first nations to support Islam.

Despite being a Christian empire, Axum maintained peaceful relations with early Muslims.

Example: Islamic tradition refers to King Negus as a righteous ruler, proving Axum’s influence in world religions.

Key Takeaway: Africa was a centre of religious and spiritual movements, shaping both Christianity and Islam.

5. The Decline and Legacy of Axum

A. Why Did Axum Fall?

Over time, Axum faced challenges such as:

Overuse of resources and deforestation.

Trade competition from rival states like Persia and the Byzantine Empire.

Invasions from Muslim armies and internal conflicts.

By the 10th century CE, Axum declined and was eventually replaced by the Zagwe Dynasty and later the Ethiopian Empire.

Example: Many Axumite traditions were carried on by Ethiopia, which remained one of the few African nations never fully colonized.

Key Takeaway: African civilizations did not simply "vanish"—their traditions and legacies were passed down to future generations.

6. The Garveyite Vision: Lessons from Axum for Today

Axum proves that Africa was a centre of global trade, wealth, and innovation.

Black nations today must rebuild economic self-sufficiency, just as Axum controlled trade.

African unity is possible—Axum ruled multiple regions and maintained strong leadership.

Religious institutions must serve Black self-determination, as Axum used Christianity to strengthen its empire.

Final Thought: Will We Restore Africa’s Greatness?

Marcus Garvey believed that:

“Africa for the Africans, at home and abroad!”

Will Black people continue to depend on foreign nations, or will we reclaim our economic and political power?

Will we rebuild African empires, or continue to suffer under neocolonialism?

The Choice is Ours. The Time is Now.

#blog#black history#black people#blacktumblr#black tumblr#black#black conscious#pan africanism#africa#black power#black empowering#african kingdom#AksumiteEmpire#black excellence#ReclaimOurHistory#Garveyism#marcus garvey

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ethiopian Highlands...

#nature#hiking#travel#naturecore#nature photography#ethiopia#highlands#mountains#mountain range#east africa#africa#africa travel#african photography#sunrise#sunsets#clouds#vista#gelada#baboon#travelcore#travel destinations#travel photography#landscapes

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Oromo people are one of the largest ethnolinguistic groups in Africa, primarily concentrated in Ethiopia but also found in Kenya and parts of Somalia. Numbering over 40 million, they represent the single largest ethnic group in Ethiopia and among the largest in East Africa. The Oromo possess a deeply rooted cultural, linguistic, and historical identity shaped by indigenous institutions, centuries of resistance and integration, and a rich oral tradition.

The term Oromo is an endonym used by the people to refer to themselves. Historically, external sources used various exonyms such as Galla, a term now considered pejorative and rejected by the Oromo themselves. The origin of the word Oromo is not definitively established, but scholars believe it may derive from the root orma, meaning "person" or "human being" in the Oromo language. This etymological link aligns with the people's cultural emphasis on egalitarianism and collective identity.

The Oromo predominantly inhabit Oromia, a vast regional state in central, southern, and western Ethiopia, which is administratively recognized within the federal system of Ethiopia. Oromia borders nearly every major Ethiopian region, including Amhara, Somali, Benishangul-Gumuz, and the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region. Oromo communities are also found in northern Kenya, particularly in the Marsabit and Moyale areas, and to a lesser extent in Somalia.

Their ecological distribution spans highland, lowland, and semi-arid regions, which has historically enabled them to engage in varied economic activities, from pastoralism and agro-pastoralism to sedentary agriculture and urban labor.

The Oromo speak Afaan Oromoo (also known as Oromo language), a Cushitic language of the Afroasiatic family. With tens of millions of native speakers, it is among the most widely spoken African languages and the most spoken language in Ethiopia. Afaan Oromoo is notable for its dialectal diversity, which includes major regional varieties such as Western Oromo, Eastern Oromo, and Southern Oromo. Despite this, mutual intelligibility is generally high.

The language was traditionally written using indigenous scripts such as Ge'ez and later Latin alphabets. Since the early 1990s, the Latin-based orthography known as Qubee has become the standard script for writing Afaan Oromoo, promoted especially following the fall of the Derg regime and the subsequent rise of linguistic nationalism among the Oromo. Afaan Oromoo is currently used in regional government, education, and media in Oromia.

The Oromo people are indigenous to the Horn of Africa, with linguistic and archaeological evidence indicating their presence in the region for millennia. Their origins trace back to the Cushitic-speaking populations that have inhabited northeast Africa since at least the third millennium BCE. While concrete written historical records are sparse for early periods, oral traditions and comparative linguistics place the proto-Oromo in the southern highlands of Ethiopia by the first millennium CE.

A defining episode in Oromo history is the period of expansive migrations during the 16th and 17th centuries, referred to as the Great Oromo Migrations. Triggered by socio-political and ecological pressures, the Oromo expanded northward and westward from their earlier homelands in the Borana region. This movement was both military and demographic in nature, involving the absorption of and conflicts with multiple ethnic groups, including the Sidama, Gurage, Amhara, and Somali.

These migrations resulted in the widespread Oromo settlement across much of present-day Ethiopia and parts of Kenya. The expansion was organized under the leadership of the gadaa system, a uniquely Oromo sociopolitical institution, and was instrumental in shaping the demographic and political map of the region.

During the late 19th century, the Oromo regions were gradually incorporated into the expanding Ethiopian Empire under Emperor Menelik II. This process, often accomplished through military conquest, resulted in the loss of Oromo political autonomy and the imposition of centralized imperial authority, predominantly dominated by the Amhara ruling elite.

The incorporation led to significant land alienation, cultural marginalization, and suppression of the Oromo language and institutions, contributing to deep historical grievances. The period also witnessed forced religious conversion, imposition of new administrative systems, and the introduction of tax burdens that disrupted traditional economic systems.

Throughout the 20th century, Oromo identity and political activism grew steadily, especially in opposition to imperial centralism, military dictatorship under the Derg (1974–1991), and later federal challenges. The formation of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) in the 1970s marked a turning point in organized resistance, aiming for self-determination and cultural revival.

After the fall of the Derg in 1991, the new federal constitution of Ethiopia established a system based on ethno-linguistic regional states, and Oromia was created as a semi-autonomous region. Despite this, tensions between Oromo nationalists and the central government persisted. The late 2010s and early 2020s saw widespread protests across Oromia demanding political reform, economic justice, and greater linguistic and cultural recognition. These culminated in the rise of Abiy Ahmed, an Oromo, to the office of Prime Minister in 2018. However, internal conflict, unrest, and violence continued in parts of Oromia in subsequent years.

The gadaa system is a sophisticated indigenous socio-political and generational system through which the Oromo traditionally governed themselves. Recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, gadaa organizes society into generational classes that rotate leadership every eight years. It includes functions of law-making, conflict resolution, military organization, and ceremonial life.

The system is democratic in nature, allowing for the peaceful transfer of power, the institutionalization of age-based roles, and public accountability. While colonial and post-imperial structures weakened the institutional power of gadaa, it remains a potent symbol of Oromo identity and governance philosophy.

Oromo religious practice is historically diverse. Traditionally, many Oromo followed Waaqeffanna, a monotheistic belief in a supreme deity called Waaqaa. Waaqeffanna is a deeply spiritual and moral system centered on the reverence for nature, ancestors, and truth (safuu).

In the last few centuries, significant numbers of Oromo have converted to Islam and Christianity due to missionary activities, regional influences, and historical assimilation. Today, the Oromo population includes Muslims (particularly in eastern and southern Oromia), Ethiopian Orthodox Christians (more prevalent in the central highlands), and Protestant Christians (especially in the western regions).

Despite religious differences, Oromo communities often retain cultural unity and elements of shared indigenous spirituality, especially through rituals, oral poetry, and moral codes rooted in safuu.

The Oromo economy is traditionally based on a combination of agriculture, pastoralism, and trade. In the highland regions, crop farming is dominant, including the cultivation of cereals like teff, maize, barley, and wheat. Enset (false banana) is important in the southern highlands. In lowland and semi-arid zones, pastoralism—centered on cattle, goats, and camels—remains crucial.

In urban and peri-urban areas, the Oromo have increasingly engaged in wage labor, commerce, education, and professional services. The economic role of Oromia within Ethiopia is substantial: it includes significant coffee-growing areas, gold deposits, and central transport corridors including Addis Ababa (Finfinne), which, though a federal city, is geographically within Oromia.

Afaan Oromoo is rich in oral literature, which includes epic poetry, proverbs, storytelling, and songs that convey historical knowledge, moral codes, and social values. Geerarsa (a type of praise poetry) and weedduu (songs of lament or celebration) are especially prominent forms of expression.

Oromo arts include leatherwork, beadwork, pottery, and weaving. Oromo music uses traditional instruments such as the krar (lyre), cabbal (drum), and various flutes, with performances accompanying social rituals, seasonal celebrations, and political gatherings. Traditional dances such as shagoyyee or dhaabaa also reinforce social cohesion.

Oromo society is organized along age-sets, clans (moieties), and lineage groups. Clans are exogamous and play a central role in identity, conflict mediation, and marriage arrangements. Despite patriarchal norms, women historically played roles in ritual life and social resistance. For instance, the siiqqee tradition—symbolizing women’s right to justice and sanctuary—provided women collective power to protest against domestic and social injustice.

In recent decades, gender roles have begun to shift, with increased access to education and political participation for Oromo women, although challenges of inequality and gender-based violence persist.

Oromo political movements have long centered on autonomy, language rights, land issues, and resistance to domination. The OLF and other organizations, including the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), have advocated for greater self-determination, federal equity, and the protection of Oromo rights.

Contemporary issues include internal displacement due to conflict, land disputes, human rights violations, and debates about the status of Addis Ababa/Finfinne. Youth-led movements such as the Qeerroo (youth) network have emerged as powerful forces for political change, contributing to national reform agendas but also facing government crackdowns.

The Oromo diaspora has grown significantly since the 1970s, with communities in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia. These diasporas have played important roles in cultural preservation, transnational activism, and lobbying for human rights in Ethiopia. Diaspora organizations support media platforms, humanitarian aid, and civic education among Oromo populations globally

The Oromo people, with their rich heritage, linguistic legacy, and resilient social systems, constitute a central pillar in the historical and cultural fabric of the Horn of Africa. Their contemporary struggles and contributions reflect broader themes of identity, resistance, and transformation in the postcolonial African context. Despite historical marginalization, the Oromo continue to assert their cultural and political presence, striving for justice, equality, and recognition in an evolving national and global landscape.

#oromo#oromia#horn of africa#east africa#african history#indigenous peoples#afaan oromoo#oromo culture#ethnic studies#african studies#anthropology#gadaa system#waaqeffanna#oromo tradition#pan african#african diaspora#ethiopian history#oromo resistance#african languages#oromo heritage#black history#traditional clothing#oral tradition#african art#ethnic aesthetics#cushitic languages#postcolonial africa#cultural preservation

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

IceWing Names- Letter A

Abalone (A shellfish, or a very pale gray color.) Achromatic (Literally means 'without color'.) Adélie (A type of penguin. Great for a SeaWing hybrid.) Agate (A variety of chalcedony that comes in many colors, often with swirl or banded patterns throughout.) Ague (A fever or shivering fit.) Ahmar (A mountain range of the Ethiopian Highlands.) Akaishi (A mountain range in Japan.) Alabaster (A soft, white, translucent rock that is often used for carving and making decorative objects.) Alaska (As in the state.) Alba (Latin for 'white'.) Albedo (The fraction of light reflected by a surface.) Albescent (Growing or shading into white.) Albite (A white, brittle, glassy mineral.) Album (Also Latin for 'white'.) Algid (Very cold or chilly.) Alp (A high, rugged mountain that is often snowcapped. Could also be good for a SkyWing hybrid.) Alpenglow (The rosy light of the setting or rising sun seen on high mountains.) Alpine (Relating to high mountains.) Amethyst (A violet or purple quartz gem or a violet color.) Ametrine (A mixture of amethyst and citrine.) Andes (A South American mountain range that i also one of the worlds longest.) Anhydrite (A mineral that is made up of calcium and sulfate. Often pale blue or pale violet.) Annapurna (The 10th highest mountain in the world, located in Nepal.) Antarctic (Relating to the south polar region or Antarctica. Antarctica can work too.) Antler (Horns typically grown on the head of male animals such as deer, and often shed.) Apatite (A phosphate mineral.) Apex (The top or highest part of something, especially one forming a point.) Apricity (The warmth of the sun in winter.) Aragonite (A calcium carbonate mineral that forms in carbonate sediments.) Arctic Hare (A species of hare adapted to live in the arctic.) Arctogadus (A type of fish found in icy waters.) Aufeis (A sheet-like mass of layered ice that forms from successive flows of ground or river water during freezing temperatures.) Aurora (A luminous phenomenon that consists of streamers or arches of light appearing in the upper atmosphere of a planet's magnetic polar regions.) Avalanche (A mass of snow, ice, and rocks falling rapidly down a mountainside.) Azure (A shade of bright blue.) Azurite (A soft, deep-blue copper mineral.)

#wings of fire#wof#wings of fire names#wof names#icewing#icewing names#a names#mineral names#gemstone names#blue color names#names in other languages#natural phenomena names#mammal names#fish names#location names#landscape names#purple color names#bird names#white color names#cold names#winter names

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

There was discourse about continents a while ago and I saw this graphic and realized that that's basically how I would do it (as you can see I was more in the continent proliferation camp), only more properly geographically (and keeping N & S America):

or alternatively (with Africa split as well + different East/North Asia boundary):

North America (Darién Gap; Bering Strait, Denmark Strait → Greenland in N America)

South America (Darién Gap)

Europe (Urals, Ural river, Caucasus; Novaya Zemlya Through → Novaya Zemlya in Europe, Caspian Sea, Bosporus & Dardanelles, Mediterranean Ridge, Strait of Gibraltar, Denmark Strait → Iceland in Europe)

Mesothalassia* [~Middle East, ~Afghanistan, ~Pakistan] (Isthmus of Suez, Caucasus, Kopet Dag, Paropamisus Mts, Hindukush, Toba Karkar Mts, Kirthar Mts; Mediterranean Ridge border means Cyprus in Mesothalassia)

Africa (Isthmus of Suez)

Oxo-Siberica* [Central Asia, Siberia] (Urals, Ural river, Kopet Dag, Paropamisus Mts, Hindukush, Pamirs, Tian Shan, Dzungarian Alatau & Dzungarian Gate, Altai, Tannu-Ola Mts, lake Baikal, Yablonoi Mts, Amur-Shilka-Ingoda rivers /alternatively: lake Baikal, Stanovoy Highlands, Zeya, Uda; Novaya Zemlya Through, Bering Strait, Sea of Okhotsk, Bussol Strait → Kuril Islands split)

Transsinitica* [East Asia] (Red river, Hengduan Mts, Kangri Karpo Mts, Himalaya, Hindukush/Karakoram, Pamirs, Tian Shan, Dzungarian Alatau & Dzungarian Gate, Altai, Tannu-Ola Mts, lake Baikal, Yablonoi Mts, Amur-Shilka-Ingoda rivers /alternatively: lake Baikal, Stanovoy Highlands, Zeya, Uda; Gulf of Tonkin → Hainan in Transsinitica, Sea of Okhotsk → Sakhalin in Transsinitica, Bussol Strait → Kuril Islands split)

Suvarnia* [Southeast Asia] (Red river, Hengduan Mts, Arakan Mts; Lydekker Line, Philippine Trench, Luzon Strait/Bashi Channel, Gulf of Tonkin)

Cishimalaya* [South Asia] (Arakan Mts, Kangri Karpo Mts, Himalaya, Hindukush, Toba Karkar Mts, Kirthar Mts)

Oceania (Lydekker Line → Papua in Oceania)

Antarctica

if Africa were to be split I would consider the Congo-Aruwimi-Ituri rivers – Lake Albert – Imatong Mts – Ethiopian Rift Valley – Awash river – Gulf of Tadjoura line separating Saharica* and Subcongolia*

*The names of these continents are done jokingly (because it's fun), but also because you can't call a continent "Southeast Asia", it needs its own name for it to be considered as such – well... at least not when the geographic delimiters are much less established (than in the case of N & S America, for example) and the term usually groups countries and is thus an element of political rather than physical geography.

Mesothalassia is done on the pattern of Mesopotamia but with μέσος mésos ‘middle, between’ + θάλασσα thálassa ‘sea’ + -ιᾱ as the land between seas (five to be exact – Pentathalassia (> Penthalassia) doesn't sound too bad either); Oxo-Siberica takes Oxus=Amu Darya and Siberia (Oxsiberica would be going a bit too far, I feel, though it is quite euphonic); Sinitica would be too focused on China – Transsinitica goes ‘beyond’ that; Suvarnia references Suvarṇabhūmi ‘Golden land’ from Sanskrit sources that was probably somewhere in SE Asia; Cishimalaya because it is this side of Himalaya (Transsinitica could then also be Transhimalaya). Saharica and Subcongolia should be obvious – maybe Transcongolia?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

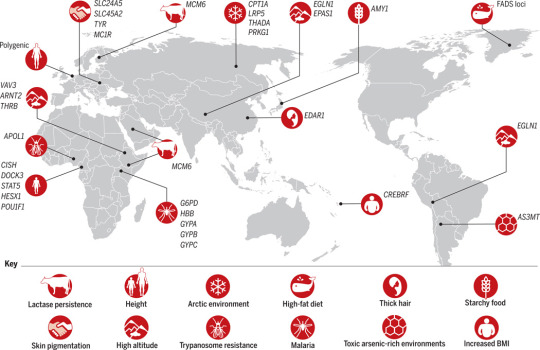

Recent evolutionary adaptations to the environment in human populations, from Going global by adapting local: A review of recent human adaptation (Fan et al., 2016). The icons show the type of adaptation recorded in various parts of the world, and the acronyms besides (e.g. EDAR1) are the names of the involved genes. Also see Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations (Sabeti et al., 2009), Population Genomics of Human Adaptation (Lachance & Tishkoff, 2013).

Some examples are:

Lactase persistence in Europe, Near East, and East Africa, allowing the digestion of milk in adult age (by default, the lactase required to digest milk sugar would only be produced by infants; this was just a matter of removing a timed switch).

Similarly, greater production of amylase, which breaks down starch, is reported in Europe and Japan (diet based on farmed grains) and among the Hadza of Tanzania (diet based on starchy tubers).

Improved conversion of saturated into unsaturated fatty acids in the Arctic Inuit peoples. This makes it easier to live on a diet of fish and marine mammals in an environment where plant food is scarce.

Smaller stature ("defined as an average height of <150 cm in adult males") in the "pygmy" peoples (Aka and Mbuti) of Central Africa, and other hunter-gatherer peoples in equatorial Asia and South America. This helps shed heat in a hot humid climate where sweat does not evaporate.

More efficient fat synthesis in the Samoa, helping with energy storage at the price of more risk of obesity or diabetes with a richer modern diet.

Improved resistence to malaria, sleeping sickness (trypanosome), and Lassa fever in Subsaharan Africa. Fighting off against parasites is especially difficult (since unlike the inorganic environment, parasites also evolve), so this resistence often comes at a cost, such as anhemia, but is still a great advantage on net. Some improved resistence to arsenic poisoning is noted in an Argentinian population.

Denser red blood cells on the Andean, Ethiopian, and Tibetan highlands, to carry more oxygen which is scarcer at high altitude. I recall from elsewhere that this might increase the risk of thrombosis or strokes due to obstructed blood vessels.

Less melanin (which blocks UV light) and therefore lighter skin color in Eurasia. Melanin shields skin cells from damage due to UV radiations, but some UV light is necessary for the synthesis of vitamin D.

A change in the gene EDAR1, resulting in denser head hair, slightly different tooth shape, and fewer sweat glands (all skin annexes), appears strongly selected for in East Asia, but as far as I can find the advantage of this mutation is still unknown.

From another article (Ilardo et al., 2018): the Sama Bajau people of Indonesia, who have a long tradition of free-diving in apnea, seem to have developed larger spleen to store more oxygenated blood during dives.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Ethiopian wolf’s diet is pretty basic: its proverbial meat and potatoes consists of a large rodent called a giant mole rat (which is meat but looks more like a fuzzy potato). But it seems that the endangered canid also has a sweet tooth. It regularly laps up sugary nectar from a tall, fiery-hued flower that adorns the animal’s high-elevation ecosystem. In the process the wolf may be serving as a pollinator, a role usually occupied by insects, birds and flying mammals—not large carnivores.

That hypothesis comes from a team at the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Program, which published its observations in the journal Ecology. For years the group’s monitors have noticed the occasional wolf drinking nectar from a local flower called the Ethiopian red hot poker (Kniphofia foliosa), which blooms from June to November and looks something like a large, furry matchstick set aflame. (Its nectar is also popular with children and baboons, says study co-author Sandra Lai, an ecologist at the University of Oxford and the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Program.)

An Ethiopian wolf (C. simensis) licks nectar from an Ethiopian red hot poker flower (K. foliosa) (left), and its muzzle is covered in pollen after feeding on the nectar (right).

Adrien Lesaffre

The new report doesn’t surprise Anagaw Atickem, an ecologist at Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia. He was not involved in the research but has studied how domestic dogs compete with Ethiopian wolves, and he says he has noticed that the dogs have a taste for this same nectar. Based on the new study’s finding, he wonders whether sharing the flowers may even spread diseases between the two species.

Both Atickem and Lai say there’s a lot more to learn about the behavior and its importance. The wolves end up with a muzzle covered in pollen, raising the possibility that they could transport it between flowers and pollinate them in the process. If they did, the wolves would be among the first known large carnivores that facilitate plant reproduction in this way. Pollination is more commonly associated with flying creatures, Lai says; scientists are only beginning to consider ground-bound mammals such as mice, squirrels, monkeys, lemurs and civets as potential pollinators.

Biologists require intricate experiments to determine whether an animal really is pollinating a specific species of flower, however; they need to confirm not only that the creature can transport pollen but also that the interaction results in fruit. “It is not impossible, although it is quite challenging,” Lai says, adding that a first step toward understanding the relation between wolf and flower might be to catalog all the animal species that appear to visit the red hot pokers.

The wolves’ sweet treats also raise conservation questions, given the challenges that the region is facing. Both the wolves and the red hot pokers are native to Ethiopia’s afroalpine ecosystem, found only in mountains some 3,000 meters above sea level. But as the nation’s human population grows, people and livestock are venturing to higher altitudes. Meanwhile climate change is raising temperatures in these highland areas.

Atickem now wonders whether the nectar provides a crucial nutrient. If so, it would underscore the need to keep the flower on the landscape as the habitat shrinks and warms. “Even small amounts of nectar may be helpful,” Atickem says. “The conservation of these flowers may be very relevant for the Ethiopian wolf.”

#article#wolves#ethiopia#pollinators#pollination#science#biology#plants#animals#carnivore#scientific american#climate change#habitat loss#flowers

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

These Wolves Like a Little Treat: Flower Nectar. (New York Times)

Excerpt from this New York Times story:

he Ethiopian wolf, Africa’s most endangered predator, has a sweet tooth.

While the wolves are otherwise strict meat eaters, scientists have spotted the canids slurping nectar from torch lilies, tall, cone-shaped flowers also known as red hot pokers with nectar that tastes like watered-down honey. And because the wolves’ muzzles get absolutely covered in sticky yellow pollen, researchers suspect they might even be acting as pollinators — a first for a large carnivore, the authors write in a paper published last week in the journal Ecology.

It’s a scene from a storybook, said Sandra Lai, an Oxford University ecologist and an author of the paper.

“The wolves lick the flowers like ice cream cones,” she said.

The Ethiopian wolf is a lanky, reddish-brown canid that looks more like a coyote or fox than a wolf. It lives in Ethiopia’s mountainous highlands, a tundra-like landscape where the wolves feed on abundant rodents.

In the Bale mountain range, the wolves’ prey of choice is the big-headed African mole rat, a preposterous-looking creature with eyes set directly on top of its head so it can peep out of underground burrows. The mole rats surface for about only an hour a day to forage for vegetation. “They try keep their butt inside the hole so they can retreat if something happens, so they stretch out as long as they can” and grab at plants with their buck teeth, Dr. Lai said.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kingdom of Axum

The African Kingdom of Axum (also Aksum) was located on the northern edge of the highland zone of the Red Sea coast, just above the horn of Africa. It was founded in the 1st century CE, flourished from the 3rd to 6th century CE, and then survived as a much smaller political entity into the 8th century CE.

The territory Axum once controlled is today occupied by the states of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, and Somaliland. Prospering thanks to agriculture, cattle herding, and control over trade routes which saw gold and ivory exchanged for foreign luxury goods, the kingdom and its capital of Axum built lasting stone monuments and achieved a number of firsts. It was the first sub-Saharan African state to mint its own coinage and, around 350 CE, the first to officially adopt Christianity. Axum even created its own script, Ge'ez, which is still in use in Ethiopia today. The kingdom went into decline from the 7th century CE due to increased competition from Muslim Arab traders and the rise of rival local peoples such as the Bedja. Surviving as a much smaller territory to the south, the remnants of the once great kingdom of Axum would eventually rise again and form the great kingdom of Abyssinia in the 13th century CE.

Name & Foundation

The name Axum, or Akshum as it is sometimes referred to, may derive from a combination of two words from local languages - the Agew word for water and the Ge'ez word for official, shum. The water reference is probably due to the presence of large ancient rock cisterns in the area of the capital at Axum.

The region had certainly been occupied by agrarian communities similar in culture to those in southern Arabia since the Stone Age, but the ancient kingdom of Axum began to prosper from the 1st century CE thanks to its rich agricultural lands, dependable summer monsoon rains, and control of regional trade. This trade network included links with Egypt to the north and, to the east, along the East African coast and southern Arabia. Wheat, barley, millet, and teff (a high-yield grain) had been grown with success in the region at least as early as the 1st millennium BCE while cattle herding dates back to the 2nd millennium BCE, an endeavour aided by the vast grassland savannah of the Ethiopian plateau. Goats and sheep were also herded and an added advantage for everyone was the absence of the tropical parasitic diseases that have blighted other parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Wealth acquired through trade and military might was added to this prosperous agricultural base and so, in the late 1st century CE, a single king replaced a confederation of chiefdoms and forged a united kingdom that would dominate the Ethiopian highlands for the next six centuries. The kingdom of Axum, one of the greatest in the world at that time, was born.

Continue reading...

61 notes

·

View notes