#deciduous forest invertebrates

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Life in the Slow Lane: The Brown Garden Snail

Perhaps the most widely known member of the mollusk group, the brown garden snail (Cornu aspersum), also known as the European garden snail, is native to the Mediterranean region of southern Europe and northern Africa, and his since spread to every continent except Antarctica. It thrives in temperate zones, particularly in open forests, coastal dunes, and urban parks and agricultural spaces. This spread has largely been facilitated by humans, and may have started as early as the Neolithic era nearly 8500 years ago.

The brown garden snail's name is an excellent descriptor of the species; both the body and the shell are mainly shades of brown. Generally the body is lighter than the shell, and secretes a thin layer of mucus to keep itself moist. The shell is about 2.5 to 4 cm (0.98-1.57 in) wide, while the body itself is roughly 5-9 cm (1.97-3.54 in) long. Body and shell combined, C. aspersum only weighs 15g (0.53 oz) at maximum. The body is made of two parts; the head, which carries the eye stalks, mouth, and sensory tentacles; and the foot, essentially a large muscle which the snail uses to move from place to place. The rest of its organs, including the heart, lungs, stomach, and anus are contained within the shell itself. Only the genital pore, located on the side of the foot, is exposed.

C. aspersum is primarily an herbivore, feeding on leaves, flowers, and fruits, as well as rotting plant and animal matter. In order to obtain the calcium it needs to build and maintain its shell, the European garden snail also occasionally consumes soil. Because of its slow nature, reaching a maximum of only 2.4 mm/s (0.09 in/s), this species is a common food item for other predatory snails, centipedes, glow worms, small mammals, lizards, frogs, and birds. However, the brown garden snail is able to retreat into its shell and produce a thick, frothy mucus membrane when threatened.

Like other terrestrial mollusks, the European garden snail is a hermaphroditic species, possessing both male and female gametes. Individuals may reproduce year round, provided with plentiful resources and good environmental conditions. When two snails encounter each other and wish to mate, each one spears the other with a hard calcite spine, known as a love dart. These darts allow the two to exchange sperm, and the process may take several hours. Afterwards, an individual may store viable sperm for up to 4 years. About ten days after a snail fertilizes its sperm, it lays about 50 eggs in a sheltered area; a single snail may do this up to 6 times a year. Eggs take between 2-4 weeks to hatch, and emerge with a soft shell. It takes about 10 months for juveniles to reach full maturity, and they may live up to 3 years in the wild.

Conservation status: C. aspersum has been rated as Least Concern by the IUCN. In both its introduced and native range, it is considered a pest species due to its consumption of crops. However, this species has also been adopted in some areas as a pet or as an edible delicacy.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Bill Frank

Alan Henderson

Kostas Zontanos

Rand Workman via iNaturalist

#brown garden snail#european garden snail#Stylommatophora#Helicidae#land snails#snails#gastropods#mollusks#invertebrates#deciduous forests#deciduous forest invertebrates#grasslands#grassland invertebrates#urban fauna#urban invertebrates#europe#southern europe#africa#north africa#animal facts#biology#zoology

112 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I saw you have an inbox for arthropod suggestions so here's mine: Typhochlaena seladonia.

Top left: "Brazilian jewel tarantula (Typhochlaena seladonia) is a species of aviculariine tarantula. They are found in Bahia and Sergipe, Brazil in rainforest parts. It is unique as an arboreal spider that constructs trapdoors in the bark of trees. Doesn't really like human contact much. They are generally more docile, although some individuals are particularly defensive."

Top middle: "Purple pink toe or purple tree tarantula (Avicularia purpurea) are mainly present in Ecuador in the Amazon Region. This species can be found in very different habitats, but frequently it is present in agricultural areas, especially in the field of grazing cattle. Sometimes it can be found in holes of walls of buildings or in the spaces below the roofs. They builds their nests primarily in hollows in the trees, sometimes in the vicinity of epiphytic plants. They eat mostly crickets, cockroaches, meal worms, waxworms and darkling beetles, but they also can catch small rodents."

Top right: "Trinidad dwarf tiger (Cyriocosmus elegans) is a New World Terrestrial Tarantula that comes from the tropical climates of Trinidad, Tobago and Venezuela. They are venomous. Also, due to being a such a small tarantula, females have an average lifespan of around 7 years while males tend to only live about 2 years."

Down left: Golden Brown Baboon Spider "Augacephalus breyeri is a species of harpactirine theraphosid spider, found in South Africa, Mozambique and Eswatini. They live in a hole that takes it between five to seven years to construct. They feed on a variety of small invertebrates such as beetles, grasshoppers, millipedes, cockroaches, crickets, and other spiders!"

Down right: "Gooty Sapphire Ornamental Tarantula (Poecilotheria metallica) also known as the peacock tarantula, is an Old World species of tarantula. This is the only blue species of the genus Poecilotheria. Like others in its genus it exhibits an intricate fractal-like pattern on the abdomen. The species' natural habitat is deciduous forest in Andhra Pradesh, in central southern India. They live in holes of tall trees where it makes asymmetric funnel webs. The primary prey consists of various flying insects."

Here's some more tarantula for you guys! Also from now on every species I make will have short description about em. Thank you for suggestion!

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

October 15th, 2023

Winter Firefly (Ellychnia corrusca)

Class: Insecta

Distribution: North America; the United States, Mexico and Canada East of the Rockies.

Habitat: Variety of habitats; coniferous and deciduous forests, along bodies of water and salt marshes, in meadows, orchards and agricultural fields, yards and open parks.

Diet: Larvae are carnivorous, hunting soft-bodied invertebrates (like snails, slugs and earthworms) within decaying wood and leaf litter; adults have been observed feeding on the sap of maple trees, as well as on the nectar of maple, aster and goldenrod flowers.

Description: Unlike most other fireflies, the winter firefly is diurnal. For this reason, it does not have a lantern and doesn't glow at night. The eggs, larvae and pupae are all bioluminescent, but adults lose their glowing capabilities within hours of emerging.

The winter firefly gets its name from its amazing capacity to survive sub-zero temperatures as they overwinter as adults. As temperatures begin to fall, fireflies gather in the gaps and grooves of trees (and sometimes buildings, too!) where they can receive sunlight, remaining warm and protected from the elements. Because they remain semi-active during the winter instead of being dormant, winter fireflies can be spotted resuming their activities as early as February, if the weather is mild.

(First and second images by me, third by Katja Schulz)

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

A writer’s guide to forests: From the poles to tropics, part 2

Dearest writers, and all who find this guide, big shout out to you. Now let’s get back into things and move ever closer to the equator.

Temperate rainforest

While most people think of rainforests as being a purely tropical environment, several exist in more seasonal areas of the planet.

Location- Coastal regions. The North American temperate rainforest is a thin belt stretching from California, through British Columbia and up into southern Alaska. In the southern hemisphere, the largest forest is found along the southern stretches of the Andes.

Climate- Temperate to subpolar. Conditions are wet, with moisture coming in the form of rain and sea mist. Seasons are variable, with summers being warm and winters cold and snowy.

Plant life- Conifers dominate these forests, with deciduous trees restricted to lower altitudes. In the north, the primary species are Sitka spruce, Douglas fir, red cedar, western hemlock, and giant redwoods. Southern forests are dominated by Podocarps, Monkey puzzle, and southern beech. High humidity means that moss, lichens and ferns grow amongst tree trunks and the forest floor.

Animal life- Whilst more densely populated than the boreal forests, the amount of wildlife is limited by resinous conifer needles, and the lack of plants on the forest floor in denser areas. Most species are arboreal, with weasels, squirrels, and various birds along up the majority of life. Moist conditions mean that there are many types of amphibians and invertebrates that live on the forest floor. Southern hemisphere forests have become host to many invasive species, such as deer, beavers, rats, and ferrets.

How the forest affects the story- The most obvious challenge for characters will be the changing of the seasons. What do your characters do as the days grow shorter and colder? And let’s not forget that rain and mist are common. Damp conditions are a breeding ground for mold and rot, so people will have to come up with ways of keeping them and their possessions dry.Then comes the vegetation. What kind of culture would develop among the tallest trees in the world? Do they live on the forest floor or up in the trees? The density of the canopy can make farming impractical, unless done in clearings or tree top platforms. If your characters and their society are arboreal, then how do they travel between trees? Bridges? Zip-lines? Or do they take inspiration from nature and glide between trees? Imagine if people on the ground meet those from up above. How would these two cultures be different? Would interactions be peaceful, antagonistic, or do they have no contact (at least until the plot requires it)? Being close to the coast, does the sea have an influence on characters and their culture? How would you explain this to someone not familiar with this environment? And you are not limited to the Earth. Remember, the California forests were the stand-in for the forest moon of Endor from Star Wars.

#writing#creative writing#writing guide#writing inspiration#writing prompts#writer on tumblr#writeblr

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Climate Change Fuels Northwest Tree Die-back

I’ve been living in the Pacific Northwest since 2006. I moved here in part because of the overall milder weather compared to the Midwest where I grew up. And yet since then I’ve watched the average temperatures get hotter, the hot periods get longer, and the rainy season shorten at both ends like the edges of a dried leaf curling up in drought. This has led to an increase in tree die-back.

There’s no more iconic natural symbol of this region than a forest. Images of vast conifer woods are used to attract tourists here, and tree iconography graces company logos, license plates, and the flag of our bioregion. The timber industry still holds immense amounts of power and land here, but conservation groups are hard at work preserving as much non-plantation forest as possible, especially the last few scraps of old growth.

It is alarming, then, to see that some of the first widely visible casualties of climate change are trees.

Last year Oregon saw the biggest die-off of fir trees–true firs in the genus Abies, not the Douglas fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii. My favorite species of tree, the western red cedar (Thuja plicata) is also declining at a frightening rate. And for the last few years, I’ve watched numerous Sitka spruce trees (Picea sitchensis) struggle and ultimately die; mature trees are surprisingly susceptible. It’s not just the conifers that are in trouble, though; one of the region’s largest deciduous trees, the bigleaf maple (Acer macrophylla) has also been hit hard by hotter, drier summers.

It’s a one-two punch, because drought-stressed trees are more susceptible to diseases and parasites. The Sitka spruce are plagued by spruce aphids, for example, but the other species also have trouble fighting off their attackers. Couple that with warmer winters that may not kill off as many invertebrates, fungi, and bacteria as usual, and infestations often roar back even bigger once spring returns. If the trees were healthy and well-hydrated their immune systems might have a better chance of fending off pathogens, but drought weakens them too much.

Other denizens of the forest are struggling, too. Amphibians here and elsewhere aren’t just going to be seeing more of their habitat dry up, but they’re also feeling more pressure from fungal infections and other pathogens. And last year the mycelium of many fungi dried out so badly in the heat that we had a terrible fall mushroom season; fungi need a certain level of hydration to be able to move the nutrients required to build the mushrooms.

I wish I could tell you there were sure fixes for tree die-back and other environmental ills. Unfortunately, even a basic understanding of climate change makes it clear that this is a massive, multi-faceted problem compounded by other environmental destruction. There are plenty of people trying to pick this massive Gordian knot apart, but it’s going to take time, and for those of us alive right now climate change mitigation is more likely than total reversal.

But–sometimes the best thing one single person can do is tug at an individual thread. And sometimes that can make a difference on a local, personal level. For example, arborists suggest that if you have a small number of vulnerable trees in your yard, you may be able to help them get through the drought with supplemental watering. Planting more native trees is still a valid way to help, too! Your young seedlings and saplings may also need some extra water each summer, but even if only some of them survive further tree die-back that’s still more trees than there were before. Just make sure you’re planting them in appropriate ecosystems!

Since I mentioned them earlier, amphibians and other wildlife can benefit from the preservation and restoration of their habitat, even small patches of wetlands and other cool, damp places. If you’re feeling ambitious and have the opportunity, building a small pond and surrounding it with native plants may offer frogs and salamanders a safe place to spawn and rest.

Even if you don’t have a yard or can’t take on a project at home, see if any local municipal, county, or nonprofit organizations need volunteers for habitat restoration projects in your area. Biodiversity centered on native species is one of the best ways to help an ecosystem weather harsh changes; even if one species is struggling, another native species in the ecosystem may be able to take up some of the slack and still support the overall web of interrelationships. Removing invasive species is quite possibly one of the best ways to prepare an ecosystem for the onslaught of climate change. And not every member of a given species is going to drop dead instantly; a healthy population of a species can handle some mortality and still reproduce enough to keep going. Habitat restoration is key to both bolstering biodiversity and increasing population numbers of the species themselves. That’s going to help the trees, the fungi, the amphibians, and everyone else, too.

Finally, it’s important to keep taking care of yourself. You can’t be a good steward to the nature around you if you’re so tired and depressed that you can barely get out of bed. The stress of climate change, sociopolitical turmoil, and interpersonal issues, among other things, is enough to have knocked a lot of people down; even I have days where my optimism gets tarnished and worn. So please don’t feel bad if you just can’t muster the time, energy, or other resources to “go save the world.” Do your best to get that self-care going, even if it’s just the bare bones, and no need to feel guilty, either.

One thing I find helps a lot when I’m feeling down about, well, everything is to take Mr. Rogers’ advice and look for the helpers. The news is full of negativity because that’s what gets clicks. But I try to focus on ways people are trying to improve things. Sometimes amid the scary headlines I do find stories of scientific breakthroughs that can help curb climate change symptoms, or other environmental success stories. I consider that in spite of the unwieldiness of large, governmental bodies, there are people within federal, state, and other public entities who are doing their best to use the resources available to them to do some good in the world. I also reconnect with individual people I know who are trying to make the world a better place, even in very small ways, and I remember that quite often the changes that are helping are too quiet and unobtrusive to make it into the media. Or, as Tolkien said via Gandalf the Grey: “I have found that it is the small everyday deed of ordinary folks that keep the darkness at bay. Small acts of kindness and love.”

And I walk outside, where there are still many Sitka spruce in view. A few of them still show damaged branches from previous heat waves, but they persist in spite of that. In the weeks to come, the tips of their branches will start growing bright green new growth for the year. I can’t promise them that I can save every single one in the next tree die-back, but it reaffirms for me that I still have many reasons to keep fighting.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#climate change#tree#forest#environment#environmentalism#conservation#habitat restoration#endangered species#nature#trees#look for the helpers#amphibians#wildlife#ecology#self care#fungi#mycelium#drought

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ectopistes migratorius better known as the passenger pigeon or wild pigeon is an extinct species of pigeon that was endemic to North America. Its common name is derived from the French word passager, meaning "passing by", due to the migratory habits of the species. The scientific name also refers to its migratory characteristics. Pasenger pigeons once ranged throughout the majority of North America, being found anywhere where deciduous forests and mixed woodland could be found. However breeding primarily occurred around the Great Lakes, Hudson Bay, eastern rockies, and the Appalachian mountains. There diet primarily consisted of nuts, seeds, cherries, berries, grapes, grains, worms, caterpillars, snails, ticks, and other invertebrates. The passenger pigeon was nomadic constantly migrating in enormous flocks searching for food, shelter, and breeding grounds. The passenger pigeon was once the most abundant bird in North America and possibly the most numerous species of bird on earth numbering anywhere from 3 to 5 billion animals. With flocks so big people reported they blocked out the sun for hours on end. Reaching around 15 to 16 inches (38 to 40.6cms) in length and 9.2 to 12oz (260 to 340g) in weight, the passenger pigeon was a sexually dimorphic species with males being slightly larger and possessing a coloration of mainly gray on the upperparts, lighter on the underparts, with iridescent bronze feathers on the neck, and black spots on the wings. Whilst the slightly smaller female had a coloration of grey on throat, breast, and belly, brown on the head and body, and rufous on the edges of the wings. Although the Passenger pigeons had been hunted by Native Americans for millennia, hunting intensity increased exponentially after the arrival of Europeans, particularly in the 19th century. Pigeon meat was commercialized as cheap food, resulting in hunting on a massive scale for many decades. There were several other factors contributing to the decline and subsequent extinction of the species, including shrinking of the large breeding populations necessary for preservation of the species and widespread deforestation, which destroyed its habitat. A slow decline between about 1800 and 1870 was followed by a rapid decline between 1870 and 1890. In 1900, the last confirmed wild bird was shot in southern Ohio. The last captive birds were divided in three groups around the turn of the 20th century, with some breeding attempts occurring with mixed success. The last known captive passenger pigeon Martha died on September 1, 1914, at the Cincinnati Zoo.

Art used can be found at the links below

#pleistocene pride#pliestocene pride#pleistocene#pliestocene#cenozoic#ice age#extinct#animal facts#bird#passenger pigeon#pigeon#recently extinct

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: a nilgiri wood pigeon sits in a tree, various shades of grey and red-grey, with a sort of checkerboard pattern on it's neck and a red and yellow beak. in the next photo, a sri lanka wood pigeon, similar looking to the nilgiri wood pigeon, but with a red and green iridescent neck and a black and yellow beak. it is sitting in a tree]

Two more Wood pigeons join the fray, and these 2 are both wonderful models they both have appeared on stamps!

The Nilgiri wood pigeon likes deciduous forests in southwestern India. they are a large pigeon with a distinctive checkerboard pattern on their necks! They eat fruit but they have also been seen been seen eating small snails and other invertebrates. they are also been seen eating soil possibly possibly to help with digestion or to gain extra nutrients. they make movements within the forest according to the fruiting seasons.

The Sri Lanka wood pigeon lives In damp evergreen woodlands. outside of the breeding season it is silent! It is considered vulnerable but it is legally protected in Sri Lanka, which is also the only country where it is found.

[ID: two postal stamps, one of a nilgiri wood pigeon, the other of a sri lanka wood pigeon, both sitting in trees.]

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun fact: Banana slugs secrete a mucus that numbs the tongue of predators! Some potential predators will instead roll around on the slugs to coat themselves in the mucus and gain that protection for themselves.

The famous Ariolimax columbianus, better known as the Banana Slug, is one of the largest terrestrial slugs in the world. They can grow to be 7-10 inches (185-260 mm) long and can be found in the dense, wet forests surrounding Mount Rainier. While they are often yellow, they can also be green to almost white and can have black or brown spots.

NPS Gifs ~kl

#banana slugs#Stylommatophora#Ariolimacidae#terrestrial snails & slugs#slugs#gastropods#mollusks#invertebrates#terrestrial invertebrates#evergreen forest#evergreen forest invertebrates#temperate rainforest#temperate rainforest invertebrates#deciduous forests#deciduous forest invertebrates#north america#western north america

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

the wood thrush is a common passerine bird throughout much of north america. they are primarily known for the male’s distinctive, often regarded as beautiful, song. they primarily feed on invertebrates, with a preference for earthworms. they are often solitary birds dwelling in deciduous forests, but may forage and feed in mixed-species flocks.

555 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frolic with the Fire Salamander

The fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) is a species of salamander native to the deciduous forests of central and southern Europe. They commonly reside near sources of water such as ponds or streams, but can also be found under logs and leaf litter in moist environments.

Fire salamanders are so named for their bright yellow and black coloration, which serves to warn away potential predators. In addition to their unique look, S. salamandra is also noted as the largest salamander species, at up to 25 cm (9.8 in); females are slightly larger than males. The two are otherwise indistinguishable outside the breeding season, when the area around the male's vent swells.

Depending on their region, S. salamandra breed at different times of the year; those in colder climates begin in June or July, while populations in warmer areas mate in October. Males seek out females on land, and after a brief courtship ritual he deposits a packet of sperm for her to pick up. The eggs develop internally throughout the winter, and the female gives birth to 20-75 newly hatched larvae in the following spring. These larvae live in ponds or slow-moving streams for 3-5 months before fully metamorphosing into adults. Individuals can survive for up to 14 years in the wild.

The bright coloration of fire salamanders is a form of aposematism; warning predators of their toxicity. The skin secretes a highly potent toxin, which can also be sprayed directly at potential threats. However, only adults have this ability, so juveniles may be victim to birds, frogs, fish, and mammals like weasels and foxes. S. salamandra in turn consumes mainly insects and invertebrates like earthworms, slugs, larvae, beetles, and centipedes. They do most of their foraging at night, and rarely stray far from their small home territory./

Conservation status: The fire salamander is considered Vulnerable by the IUCN. Their main threat is from the chytrid fungus, which can wipe out entire localities. Populations are also threatened by habitat loss, as they require both pristine waters and dense forests to thrive.

Photos

William Warby

Quentin Martinez

Christian Jansky

#fire salamander#Urodela#Salamandridae#true salamanders#salamanders#amphibians#deciduous forests#deciduous forest amphibians#europe#central europe#southern europe#animal facts#biology#zoology#ecology

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Early Temperocene: 145 million years post-establishment

These Nuts: Flora and Fauna of the Disnut Forests

The northern, temperate regions of Mesoterra are flourishing with life in the early Temperocene. These lush regions are covered in temperate, deciduous forest, ones that experience varying, but moderate weather, with warm summers and mild winters, enough to experience seasons but stable enough for life to thrive all-year round.

The trees that comprise this forest are, like many of the trees on HP-02017, are descendants of drupes: the stonefruit family. Like their relatives, the pebblefruit and the beachpeach, they too have evolved their own unique adaptations over the many millennia of co-habiting with its fauna. Yet unlike the pebblefruit, which evolved clusters of multiple small hard seeds inside each fruit, these drupes have taken an opposite route. Rather than make their seeds smaller and harder, they made each seed very large -- roughly mango-sized-- and invested more on fewer seeds, with the fruit itself, rather than being soft and juicy, instead forms a tough shell around the seed as a protective layer. These are the disnuts, or the Pseudamygdalidae: seeds that evolved into a false nut of sorts, due to significant evolutionary pressures that have changed over time.

Early in the Rodentocene and in the Therocene, fauna consisted exclusively of small, gnawing rodents that would inevitably damage the seed. Now, in the Temperocene, far bigger browsers have evolved, ones that could more easily swallow large seeds whole and disperse them. As such, while their pebblefruit relatives catered to smaller rodents, by having small, hard, swallow-able seeds, the disnuts evolved to deter them with hard shells and large seeds: instead catering to the giant browsers that call Mesoterra home.

Of these browsers, among the most common are the thompers: giant hamtelopes of the rabbeast family that in the Temperocene have evolved into enormous knuckle-walkers whose digits evolved into claws rather than hooves, and are among the primary dispersers of disnut seeds. As browsers, they use their powerful front claws to hook branches down and gobble up their contents, leaves, stalks and fruit alike. The bearded thomper (Titanolagus griseus) is one such disperser, with the powerful digestive enzymes helping break off the seed's tough outer coating to germinate in its droppings: many disnut species will only germinate if stimulated by their passage through the herbivore's digestive system and will not sprout otherwise.

By passing out seeds in their dung, the thompers inadvertently cultivate a forest wherever they migrate in search of food, and other herbivores soon follow. Hoofed bambunnies like the varicolored stabruck (Smilungulus splendens), another more gracile lineage of rabbeasts, browse on the tender low-level shoots, as well as use their tusks to scrape lichen and bark off the trunks. Dwarf piggalo also take refuge here, some becoming omnivorous foragers rummaging on the leaf litter of the forest floor. They eat leaves, stems and even sometimes invertebrates if they can find them, but the fallen fruit of the disnuts are consumed with a special relish. Unfortunately for the seeds, however, piggalo are so efficient at processing vegetation that seeds seldom survive their pulverizing molars and powerful digestive juices, which is why they are a much less favorable vector of the seeds. With the relatively colder weather of the forests, these smaller northern piggalo are quite hairier than their bigger southern cousins, such as the hirsute nuthog (Hirsutosuimys minimus), however they still are not very well-suited for cold and migrate south in winter in herds: many disnut tree species have taken advantage of their seasonal absence by producing fruit in late autumn, where their seeds are less likely to be destroyed by the ravenous foragers and instead find their way into more preferred hosts, the thompers. Thompers stay in the forest all year round, and have adapted to the fickle weather, with insulating coats, and large ears that act as heat sinks in hot weather, but be folded down in cold teperatures to conserve heat, allowing them to tolerate the different climes of the region and thus exploit the seasonal bounties of food.

These herbivores, in turn, are prey to Mesoterra's local apex predator, one that arose in the Temperocene after the extinction of the ripperroos and their harmster kin: the fangaroos, with the disnut forests being home to one of the larger species, the forest fangaroo (Lycasmilotherium sylvus). These, like their predescessors, are carnivorous podotheres from the loupgaroo lineage, but instead of slashing and slicing teeth and claws, they possess a pair of long, piercing fangs, derived from the pseudo-canine first molars of their ancestors, for dealing deep wounds into large prey. These fangs are kept concealed in specialized oral pouches when the mouth is closed to protect them from damage, as they are vital for its survival. Preferred prey items include thompers and piggalo, though great care must be taken, as the former's powerful claws, and the latter's formidable tusks, make them very dangerous game, especially for a solitary predator, but if a kill is successful, it will yield plentiful food for days.

Smaller predators on Mesoterra skulk in the shadows of the fangaroos: the scabbers, a clade of long-tailed hunters hailing from Isla Centralis that had convergently evolved with the zingos of the mainland into cursorial canid-like runners. Still, here, in the disnut forests, they have adopted a smaller an humbler role, such as the fuzz-tailed groundhound (Cynorattus pelagocauda), a small fox-like omnivore that targets smaller game, particularly furbils, duskmice, small rattiles and ratbats, as well as invertebrates in the leaf litter and at times even berries and fruit it finds in shrubs and bushes in the undergrowth. Unlike other species of scabbers living further south, with long naked tails used for thermoregulation, the groundhound's tail is shorter and covered in hair, as to reduce heat loss in the relatively cooler climate.

But the most distinctive life of the Mesoterran disnut forests are the ones that dwell high up in the treetops. Here, like on Gestaltia and South Ecatoria, the lemunkies rule the trees --a niche instead filled in Gestaltia and Austro-Easaterra by the arboreal rhinocheirids known as treebumms-- yet here on Mesoterra, they are trending toward the small and agile. Pygmy chitterpitters (Chitta pitta) are abundant in the forests canopy, traveling in tight social bonds numbering in the dozens. They too feed eagerly on the abundant disnuts, and spend their days foraging for the disnut fruit while sentries look out for danger. Much like the piggalo, they not only eat the hard outer fruit, but the seed as well: but, while they may sound destructive, their seed hoarding behaviors can actually prove beneficial-- as many of their cached meals are inadvertently forgotten and misplaced, effectively being planted and allowed to grow. With the great numbers of seeds they bury, their forgetfulness in a way has unintentionally made them one of the forest's most important gardeners.

The chitterpitters social foraging and sentry duty helps them to keep watch out for arboreal hunters, as being small has the downside of being on the menu for many other creatures. And the disnut forest's canopy has one such unusual predator dwelling in the branches: the woodspringer (Parapterodens tigris). This podothere's unique anatomy, with opposable grasping toes on its feet and skin flaps under its arms to allow it limited gliding, mark it as one of the cragspringers, a clade of mountain-dwellers native to the Mesoterran Alps that gave rise to the now-successful pterodents. Some basal cragspringers, however, descended from the mountains and found new environments to put their climbing and leaping skills to good use. Woodspringers are omnivores, but lean more heavily toward carnivore, and one favored prey species are small lemunkies like the chitterpitter. They tend to strike from above by dropping down from branches and parachuting downward to their quarry to pin them with their feet, a strategy evolved in parallel to their flighted cousins the pterodents. Aside from lemunkies, woodspringers will take anything they can get, even disnut fruits on occasion, and it is this degree of behavioral flexibility that has allowed basal cragspringers to persist, in a world where their flying cousins the pterodents have since diversified, bearing all the cragspringer's advantageous traits, and more.

------------------

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

typhlonectes:

Cecropia Moth (Hyalophora cecropia)

What flies in the night, is almost as big as a bat, is brown and red and white, and (possibly) lives in your own backyard?

You may never have seen one, but chances are good you’ve hosted giant Cecropia Moths at some phase of their lives. Adult Cecropia Moths, the largest North American moth, flaunt their nearly 6-inch wingspan after dark, but vanish against tree trunks during daylight.

Caterpillars eat leaves from many common backyard trees, and grow to fat, green, 5-inch sausages on their diet. Every bite these caterpillars eat counts twice as much, since they’re also eating for their future selves.

Adult Cecropias live for up to two weeks on energy stored from their youth, because after pupating, Cecropias never eat another bite.

photo by Mark Beckemeyer | Flickr CC

via: Peterson Field Guides

Fun fact: Female cecroptia moths will release pheromones that males as far away as one mile can detect. Males will travel up to seven miles to find a mate.

#cecropia moth#Lepidoptera#Saturniidae#saturniids#moths#insects#Arthropods#invertebrates#deciduous forests#deciduous forest insects#generalist fauna#generalist insects#north america

299 notes

·

View notes

Text

December 16th, 2023

Six-spotted Tiger Beetle (Cicindela sexguttata)

Distribution: Found in the northeastern USA and southern Canada; north to Ontario, west to Minnesota and as far south as Kentucky.

Habitat: Mainly found in deciduous forests, but also in sunny areas like dirt paths, sidewalks and roads, fields, grassy areas and on decaying logs (but rarely far from wooded areas).

Diet: Adults and larvae are both carnivorous, feeding on insects and other invertebrates, such as caterpillars, ants and spiders.

Description: Despite being called the six-spotted tiger beetle, the spots on thus tiger's elytra may vary between zero to eight spots. They also have remarkably long legs, allowing them to run at high speeds—they're so fast, in fact, that their eyes have trouble processing fast enough to keep up, meaning they can't run more than short spurts without being blinded. As expected by their speed, adults are active predators—the grub-like larvae, however, are ambush predators, burrowing into patches of sandy substrate and lunging out at their prey when it comes near. In order to avoid being dragged out of their burrow, larvae also have hooks on their abdomen, allowing them to hang onto the substrate.

These beetles are rather long-lived, usually living around three or four years. In order to survive the cold winters, adults overwinter in the same burrows they used as larvae. They're also mostly harmless—though the adult has large, threatening mandibles and is an aggressive predator, it will not bite unless handled.

(Images by TheAlphaWolf and Mathew L. Brust)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) is Canada’s largest woodpecker, approximately crow-sized. They occur in woodlands and boreal forests across Canada, and in appropriate habitat down the west coast of North America, and south through the predominately deciduous forests of the eastern U.S., deep into Florida.

I have shown the female, above, a male below, and young nearly ready to leave the nest, which the birds carve out of the trunks of trees, giving it a distinctive shape, narrower at the top than at the bottom. When they are searching for food, their strength allows them to dig deeply, even into live trees, leaving holes that are characteristically more or less in the shape of perpendicular rectangles.

Decades ago, an adult Pileated Woodpecker found in a weakened condition, unable to fly, was brought to my mother, a pioneer in wildlife rehabilitation. We called her Priscilla, and never did determine what was wrong with her – but she responded to our help, growing stronger each day. She eventually developed enough strength to draw blood with her blows on our hands as we hand-fed her (she was otherwise a reluctant feeder). We lived in a century old, mostly wooden heritage house famous because Group of Seven artist Fred Varley, had lived there at the end of his life. (Footnote, I knew him, discussed art with him and he had once been on an arctic voyage with one of my mentors, bird artist T.M. Shortt; Varley’s basement studio became my own for many years.)

Anyway, as she strengthened Priscilla figured out how to open the dog crate we had kept her in. Having a Pileated Woodpecker loose in a valued, rented wooden house was nerve-wracking, especially when she hid in the space between the hardwood main floor and the basement ceiling, and began hammering. She would only come out when we were absent. Eventually I was able to noose her and pull her out, protesting loudly. Happily, she was soon completely healthy and we released her into the forest, it being a joy to do so.

They eat mostly invertebrates, including carpenter ants and various wood-boring beetles plus various fruits, nuts and berries (Audubon painted them amid wild grape). They sometimes will come to the ground, and can be attracted to bird feeders (including, one winter, my own) with suet or shortening. Pairs remain together year-round, are very territorial when breeding, and normally lay three to five eggs which both parents incubate on woodchips at the bottom of the cavity, which is then abandoned, often to be used later by other species such as Wood Ducks or owls. The painting is in oils and is 24 by 18 inches, the birds approximately life size. I’ve included a few studies done years ago.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Species: Foxes (Vulpes)

This series focuses on helping people choose interesting species for their fursona through informing them of the many, often overlooked, species out there! This post is about foxes.

──── ◉ ────

Bengal Fox (Vulpes bengalensis)

Size: 46cm (18in) lenght, 25cm (10in) tail lenght, 2.3-4.1kg (5-9lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on invertebrates, small mammals, birds, reptiles; eats fruit

Habitat: scrublands, deciduous forests, grasslands

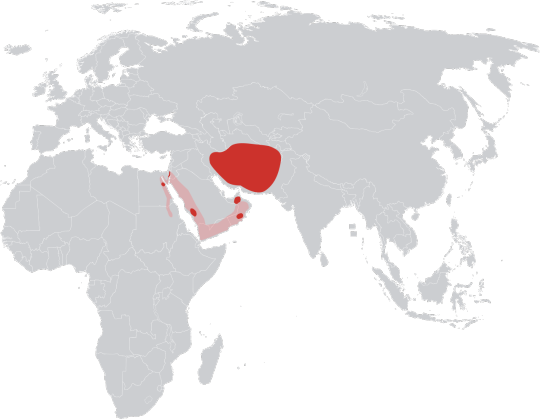

Range:

Status: least concern

──── ◉ ────

Blansford's Fox (Vulpes cana)

Size: 38-80cm (15-31in) lenght, 33-41cm (13-16in) tail lenght, 0.8kg (1.7lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on invertebrates; eats capers, fruit

Habitat: mountainous deserts

Range:

Status: least concern

──── ◉ ────

Cape Fox (Vulpes chama)

Size: 30-35cm (12-14in) height (at shoulder), 45-60cm (17.5-24.5in) lenght, 30-40cm (12-15.5in) tail lenght, 2.5-4.5kg (5.5-9.9lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on small mammals, invertebrates, birds, reptiles; eats carrion, fruit, tubers

Habitat: savannahs, dry grasslands

Range:

Status: least concern

──── ◉ ────

Corsac Fox (Vulpes corsac)

Size: 45-65cm (18-26in) lenght, 19-35cm (7.5-13.8in) tail lenght, 1.6-3.2kg (3.5-7.1lbs) weight

Diet: mostly carnivorous, eats small mammals, invertebrates; eats carrion

Habitat: steppes, semideserts

Range:

Status: least concern

Please note! The corsac fox has 3 subspecies!

──── ◉ ────

Tibetan Fox (Vulpes ferrilata)

Size: 60-70cm (24-28in) lenght, 29-40cm (11-16in) tail lenght, 4-5.5kg (8.8-12.1lbs) weight

Diet: carnivorous, preys on small mammals, reptiles; eats carrion

Habitat: semi-arid and arid grasslands

Range:

Status: least concern

──── ◉ ────

Arctic Fox (Vulpes lagopus)

Winter coat

Summer coat

Size: 25-30cm (9.8-11.8in) height (at shoulder), 41-68cm (16-27in) lenght, 30cm (12in) tail lenght, 1.4-9.4kg (3.1-20.7lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on small mammals, fish, birds, invertebrates; eats carrion, berries, seaweed

Habitat: tundra, drift ice, boreal forests

Range:

Status: least concern

Please note! The arctic fox has 5 subspecies!

──── ◉ ────

Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis)

The kit fox has 2 subspecies:

Vulpes macrotis macrotis

San Joaquin Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica)

Size: 45-53cm (17.9-21.1in) lenght, 26-32cm (10.2-12.7in) tail lenght, 1.6-2.7kg (3.5-6lbs) weight

Diet: mostly carnivorous, preys on small mammals, reptiles, invertebrates, fish; eats carrion

Habitat: desert scrubs, shrublands, grasslands

Range:

Status: least concern (V. m. macrotis), endangered (V. m. mutica)

──── ◉ ────

Pale Fox (Vulpes pallida)

Size: 38-55cm (14.9-21.6in) lenght, 23-29cm (9-11.4in) tail lenght, 2-3.6kg (4.4-7.9lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on rodents, reptiles, invertebrates; eats berries, other plants

Habitat: semideserts, savannahs

Range:

Status: least concern

Please note! The pale fox has 5 subspecies!

──── ◉ ────

Rüppell's Fox (Vulpes rueppellii)

Size: 66-74cm (26-29in) lenght including 27-30cm (11-12in) tail lenght, 1.7kg (3.7lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on small mammals, invertebrates, reptiles, birds; eats fruit, succulents

Habitat: sandy and rocky deserts, semiarid steppes, scrublands

Range:

Status: least concern

Please note! The rüppell's fox may have 5 subspecies (it is debated)!

──── ◉ ────

Swift Fox (Vulpes velox)

Size: 30cm (12in) height (at shoulder), 79cm (31in) lenght including tail

Diet: omnivorous, preys on small mammals, invertebrates; eats carrion, fruit, grasses

Habitat: prairies, deserts, grasslands

Range:

Status: least concern

──── ◉ ────

Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)

Size: 35-50cm (14-20in) height (at shoulder), 45-90cm (18-35in) lenght, 30-55.5cm (11.8-21.9in) tail lenght, 2.2-14kg (5-31lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, varied; preys on small mammals, birds, reptiles, invertebrates; eats carrion, berries, fruit, other plant material

Habitat: Literally Everywhere My God™

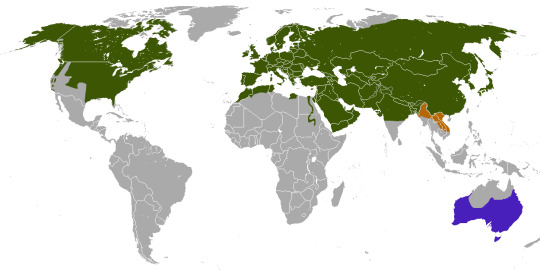

Range (green native, blue introduced, orange uncertain):

Status: least concern

Please note! The red fox has 45 subspecies!

Of which I would like to highlight:

Labrador Fox (Vulpes vulpes bangsi)

Arabian Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes arabica)

Kodiak Fox (Vulpes vulpes harrimani)

American Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes fulva)

Please also note, there is color variation among red foxes regardless of subspecies

──── ◉ ────

Fennec Fox (Vulpes zerda)

Size: 34.5-39.5cm (13.6-15.6in) lenght, 23-25cm (9.1-9.8in) tail lenght, 1-1.9kg (2.2-4.2lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on small rodents, reptiles, invertebrates; eats fruit, tubers

Habitat: deserts

Range:

Status: least concern

──── ◉ ────

#fursona resources#species#furry#fursona#fox#foxes#mammals#canidae#canines#vulpes#bengal fox#blansford's fox#cape fox#corsac fox#tibetan fox#arctic fox#kit fox#pale fox#rüppell's fox#swift fox#red fox#fennec fox

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fun fact: This moth was first described in 1773 by entomologist Dru Drury, who thought it was from Bengal or China. Because of their beautiful pattern, the wings were sometimes used to make jewellery in the Victorian era.

#madagascan sunset moth#Lepidoptera#Uraniidae#day moths#moths#insects#Arthropods#invertebrates#tropical insects#tropical rainforests#tropical rainforest insects#tropical fauna#deciduous forests#deciduous forest insects#africa#east africa#madagascar

640 notes

·

View notes