#deciduous forest insects

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Night Out with the Eastern Firefly

The eastern firefly, or North American firefly (Photinus pyralis), is a popular sight throughout the United States and southern Canada east of the Rocky Mountains. They are commonly associated with the beginning of summer, as they spend the winter hibernating underground and emerge only when the weather begins to warm. They are commonly seen in deciduous forests, grasslands, gardens, and backyards.

Contrary to their name, the eastern firefly is actually a type of beetle with well-developed wings. Adults are quite small, only 10-14 mm (0.39-0.55 in) long. They have a yellow and red head and a dark brown body with a narrow yellow stripe marking the outline of the wing casings. The main difference between the two sexes is the length of their wings; males have longer wings and are capable of flight, while females have shorter, less functional wings. Both sexes have a special organ on the end of their abdomens that produce light; however, the female's light tends to be weaker. The North American firefly produces its light by combining oxygen with a chemical called luciferin; the resulting chemical reaction gives off a glow which is amplified by special reflective cells in the firefly's abdomen.

Like all fireflies, P. pyralis uses its light producing ability to attract a mate. Males flash only while flying, in bursts about 6 seconds apart. Once a female signals her interest-- also by flashing-- the male lands near her and offers her a package called a spermatophore made of sperm, protein, and nutrients. If the female accepts, she inseminates herself and buries the rest of the package with her clutch of about 500 eggs. These eggs, which glow slightly during development, hatch about 4 weeks after being laid, and the larvae feed on the remains of the nutrient-rich spermatophore. The larvae can take one or two years to develop, and spend most of their time underground or near sources of fresh water like lakes and streams. Once the larva pupates and develops into an adult firefly, they only live in this stage for about a month before dying.

Both larva and adult eastern fireflies are predators, feeding on other insects like worms, snails, and other fireflies. However, larva spend almost all their time hunting for food, while adults spend the majority of their time seeking out a mate. To avoid predation, P. pyralis can emit foul-smelling odors and excretion of sticky substances; they also emit a chemical called lucibufagin that repells spiders. However, other species of fireflies will actually mimic the light patterns of the eastern firefly in order to predate upon them.

Conservation status: The North American firefly is currently considered Least Concern by the IUCN. However, they are threatened by light pollution, pesticides, and habitat loss.

Photos

Judy Gallagher

Katja Shultz

Sydney Penner via iNaturalist

#eastern firefly#north american firefly#Coleoptera#Lampyridae#rover fireflies#fireflies#beetles#insects#arthropods#deciduous forests#deciduous forest arthropods#grasslands#grassland arthropods#urban fauna#urban arthropods#animal facts#biology#zoology#ecology

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

the hazel grouse, also known as the hazel hen, is a small member of the grouse family found across the palearctic as far east as hokkaido, and as far west as central europe. as is typical for gamebirds, the female (hen) raises a clutch of 3-6 chicks without assistance from the male. they prefer damp deciduous forest habitat, preferably with a high percentage of spruce. they primarily feed on plants with the exception of a heavy increase in insect consumption during the breeding season. the sexes can be distinguished by a few features; males have a short erectile crest (shorter in females), and a white-bordered black throat that females lack.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

ГОРНОСТАЙ (MUSTELA ERMINEA).

Небольшой и очень активный зверёк, один из самых маленьких хищников. Длина тела — 17-38 сантиметров (из которых 6-12 сантиметров приходятся на хвост), вес взрослых зверьков — 70-260 граммов. Телосложение типично для куньих: длинное, тонкое, гибкое тело на коротких лапах. Окраска очень характерна: летом горло, грудь и живот желтовато-кремовые, остальное тело окрашено в рыжевато-бурый цвет; зимой весь зверек чисто белый, кроме задней половины хвоста, окрашенной (как и летом) в черный цвет.

Горностай активен утром и вечером. Ведет преимущественно одиночный территориальный образ жизни. В общении между собой большое значение имеют обонятельные (запаховые метки), визуальные и звуковые сигналы. В качестве убежищ используют норы убитых ими ��рызунов. Выводковые жилища устраивают в норах, дуплах деревьев, под навалами валежника. Горностай легко передвигается даже в совершенно затопленных местах, ловко прыгая по стеблям тростника, хорошо плавает. Питается грызунами, реже другими мелкими животными, падалью, ягодами. Иногда х��дит по следам крупных хищников и подбирает остатки их добычи.Так же помимо грызунов, основу его питания составляют также крупные насекомые, мелкие птицы, яйца и птенцы. При изобилии пищи часто делает запасы. Ели пищи не хватает, горностай может покинуть свою территорию и отправиться на поиски более благоприятных условий.

Населяет тундры, лесотундры, хвойные и лиственные леса, лесостепи; по речным долинам проникает в степную и полупустынную зоны. Поднимается в горы до высоты 3500-4000 метров. Селится в основном в речных поймах, на опушках, зарастающих гарях и вырубках, в южных районах — в лесополосах и заросших балках. Часто встречается в агроценозах, лесопарках и даже населенных пунктах.

Максимальная продолжительность жизни — до 7 лет, но в природе подавляющее большинство горностаев живет не больше двух. Основные враги — лисы, куницы, крупные хищные птицы.

STOAT (MUSTELA ERMINEA).

A small and very active animal, one of the smallest predators. Body length is 17-38 centimeters (of which 6-12 centimeters are the tail), the weight of adult animals is 70-260 grams. The body type is typical for mustelids: a long, thin, flexible body on short legs. The coloring is very characteristic: in summer, the throat, chest and belly are yellowish-cream, the rest of the body is colored reddish-brown; in winter, the entire animal is pure white, except for the back half of the tail, colored (as in summer) black.

The stoat is active in the morning and evening. It leads a predominantly solitary territorial lifestyle. Olfactory (smell marks), visual and sound signals are of great importance in communication with each other. They use the burrows of rodents they have killed as shelters. Brood dwellings are arranged in burrows, tree hollows, under piles of deadwood. The ermine easily moves even in completely flooded places, deftly jumping along the stems of reeds, and swims well. It feeds on rodents, less often on other small animals, carrion, and berries. Sometimes it follows the tracks of large predators and picks up the remains of their prey. In addition to rodents, its diet also consists mainly of large insects, small birds, eggs, and chicks. When food is abundant, it often makes reserves. If there is not enough food, the ermine can leave its territory and go in search of more favorable conditions.

It inhabits tundra, forest-tundra, coniferous and deciduous forests, forest-steppe; it penetrates into the steppe and semi-desert zones along river valleys. It rises into the mountains to an altitude of 3500-4000 meters. It settles mainly in river floodplains, on forest edges, overgrown burnt-out areas and clearings, in the southern regions - in forest belts and overgrown gullies. It is often found in agrocenoses, forest parks and even populated areas.

The maximum lifespan is up to 7 years, but in nature the vast majority of ermines live no more than two. The main enemies are foxes, martens, large birds of prey.

Источник://rtraveler.ru/photo/1372831/,//www.rusmam.ru/photo/index?page=421, /fotkiflo.ru/zhivotnye/sibirskiy-gornostay, /ybis.ru/ kartinki/gornostay, //www.vokrugsveta.ru/vs/article/6767/, //astrakhanzapoved.ru/горностай-mustela-erminea/.

#video#nature#animal video#animal photography#Ermine#Mustela erminea#Eurasian Ermine#mustelids#predator#forest#tundra#snow#wonderful#видео#природа#фото животных#животные#куньи#хищник#Горностай#лес#тундра#снег

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

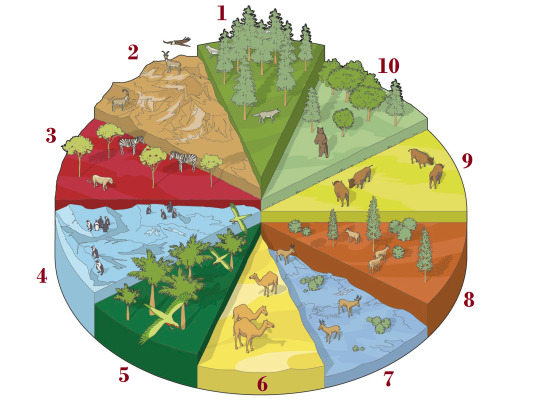

Writing Notes: Habitats

Coniferous forest - Vast areas of Scandinavia, Russia, Alaska, and Canada are the site of coniferous forests—home to moose, beavers, and wolves.

Mountain - High mountain ranges have arctic climates near the peaks, where few plants grow. Animals must cope in dangerous terrain.

Savanna - These tropical grasslands with wet and dry seasons support huge herds of grazing animals and powerful predators.

Polar ice - The ice that forms on cold oceans is a refuge for animals that hunt in the water. The continental ice sheets are almost lifeless.

Tropical rainforest - The evergreen forests that grow near the equator are the richest of all biomes, with a huge diversity of plant and animal life.

Desert - Some deserts are barren rock and sand, but many support a range of plants and animals adapted to survive the dry conditions.

Tundra - These regions on the fringes of polar ice sheets thaw out in summer and attract animals such as reindeer and nesting birds.

Mediterranean - Dry scrub regions, such as around the Mediterranean, are home to a rich insect life and drought-resistant shrubs and plants.

Temperate grassland - The dry, grassy prairies with hot summers and cold winters, support grazing herds such as antelope and bison.

Deciduous forest - In cool, moist regions, many trees grow fast in summer but lose their leaves in winter. The wildlife here changes with the seasons.

Animals, plants, and all living things are adapted to life in their natural surroundings. These environments are called habitats.

Every living species on Earth has its own favored habitat, which it shares with others. These different species interact with each other and with their natural environment—be it hot or cold, wet or dry—to create a web of life called an ecosystem.

Some ecosystems are very small, but others such as rainforests or deserts cover huge areas. These are called biomes.

Life on Land

Different climates create different types of habitats for life on land. Warm, wet places grow lush forests, for example, while hot, dry regions develop deserts. Each biome consists of many smaller habitats and, in many areas, human activity such as farming has completely changed their character.

Source ⚜ More: Writing Notes & References ⚜ Worldbuilding

#writing notes#worldbuilding#writeblr#dark academia#spilled ink#nature#writing reference#literature#writers on tumblr#writing prompt#creative writing#writing ideas#writing inspiration#poets on tumblr#poetry#writing resources

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antrostomus vociferous, better known as the eastern whip-poor-will or whip o whill, is a species of bird within the nightjar family, Caprimulgidae, which is endemic to the deciduous forests and mixed woodlands of North and Central America from Canada in the north to Costa Rica in the south and from the east coast to the great plains. Often migrating to the north of there range to breed and to the south of there range to overwinter. It is named onomatopoeically after its song as whilst the whip-poor-will is commonly heard within its range, it is rarely seen because of its elaborate camouflage. Eastern whip-poor-whills are a nocturnal species which spends there days resting amongst leaf litter, tree roots, branches, hollows, and fallen logs, emerging at night to feed upon various flying insects such as beetles, flies, mosquitos, and in particular moths. Eastern whip-poor-wills are generally solitary preferring to spend time on their own; however, during migration, they may form loose flocks. Reaching around 8.5 to 10.5 inches (22 to 27cms) in length, 1.5 to 3 ounces (42 to 85grams) in weight with a 17.5 to 19.5 inch (45 to 50cms) wingspan, eastern whip poor whills sport a large head and broad body. They have mottled camoflauged plumage: the upperparts are grey, black and brown; the lower parts are grey and black. They have a very short bill and a black throat. Males have a white patch below the throat and white tips on the outer tail feathers; in the female, these parts are light brown. Breeding often begins in March, with pairs meeting up and building a loose nest on the ground, in shaded locations among dead leaves. Here a female will usually lay 2 eggs at a time. Incubation lasts 19-21 days performed by both parents. Eastern Whip-poor-wills lay their eggs in phase with the lunar cycle, so that they hatch on average 10 days before a full moon. As when the moon is near full, the adults can better forage at night and capture large quantities of insects to feed to their young.The chicks hatch well developed covered in down but with their eyes closed. They are fed and protected by both parents and start to fly at the age of 20 days. Eastern whip-poor-wills usually produce 1 or 2 broods per year and females may lay a second clutch while the male is still caring for chicks from the first brood. Under ideal conditions an eastern whip poor will can live up to 15 years.

#pleistocene pride#pliestocene pride#pleistocene#pliestocene#cenozoic#bird#eastern whip-poor-will#eastern whip poor will#whip-poor-will#nightjar#whip-o-will#whip-o-whill#whip-or-whill#whip-or-will#north america#animal facts#central america#canada#usa#mexico#costa rica#colombia#guatemala#nocturnal

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moth of the Week

Bird-Cherry Ermine

Yponomeuta evonymella

Image source

The bird-cherry ermine is a part of the family Yponomeutidae, the ermine moths. It was first described in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus. It was originally placed in the genus Phalaena but was later transferred to the genus Yponomeuta, becoming Yponomeuta evonymella. This species’ common name comes from their main food plant: Bird Cherry.

Description This moth has a white thorax, head, and forewings. The forewings have five horizontal lines of small black dots, and a few black dots are also on the back of the thorax. The hindwings are shorter and wider than the forewings and are a beige/light brown color. Both the forewings and hindwings have a fringe on the end however, the forewings’ white fringe is short and only on the outer margin while the hindwings’ brown fringe is all over the hindwings’ edges besides the parts touching the forewings. Additionally the hindwings’ fringe is longer on the bottom of the wing. This moth’s thin and wiry antennae are two thirds the length of the forewing and are usually white.

Wingspan Range: 16 - 25 mm (≈0.63 - 0.98 in)

Diet and Habitat This species’ caterpillars mainly feeds on Bird Cherry (Prunus padus), but they also occasionally feed on cherry (Prunus) or buckthorn (Rhamnus). They are known to sometimes be pests of the bird-cheery because the caterpillars pupate and feed together in web like nests that can cover whole trees. This web keeps them protected and allows them to eat mostly unbothered by other insects and predators. The tree is still likely to survive after this, but may grow less in the following growth season/spring. Adults feed on nectar.

This species can be found in Europe and the northern and eastern parts of Asia. They live in many habitats such as river lowlands, deciduous forests, alluvial forests, stream banks with bushes and trees, gardens, parks, and more. Strangely according to Butterfly Conservation, this moth can be found “often far from the known foodplant.”

Mating This moth is seen in June to September and has only gerarion per year. Females let their eggs on the winter buds of their food plants.

Population sizes fluctuate, but it’s not uncommon for mass outbreaks of caterpillars to happen, which results in defoliated trees.

Predators This species is preyed on by parasitic wasps and seems to have few other predators.

Fun Fact This moth is attracted to light. Additionally when disturbed, this moth can skip away and falls to the ground. Note: this second fact does not currently have a citation on Wikipedia so it may be disproven in the future.

(Source: Wikipedia, Butterfly Conservation)

#libraryofmoths#animals#bugs#facts#insects#moth#lepidoptera#mothoftheweek#Yponomeuta evonymella#bird-cherry ermine#Yponomeuta

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

HAVE YOU SEEN THIS GUY? This lil' dude is the Chinese Bushbrown Caterpillar, and he is VERY important (insomuch as biodiversity is important but also just because he is very cute and I love him). Butterflies are some of the most well-documented insects in the world, but quite often their larval stages get overlooked. This little creature should never be overlooked. Native to a fairly widespread area from the Himalayas into southeast Asia, the Chinese bushbrown (or Mycalesis gotama) is a member of the satyrine group of butterflies, and their larval stage is distinct, having been referred to as the 'Hello Kitty caterpillar". Their preferred habitat in rainforests and deciduous forests, especially near glades and beside streams or logging roads. Anyway, thought you should know. c: Please enjoy possessing knowledge of this very important dude.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet September's Pal of the Month... the Flame Leg Millipede!

Living in the lush, damp deciduous forests of the Philippines, the flameleg millipede earned its name for a reason. Its vibrant orange and yellow legs stand out like tiny flames against its sleek black body, a dazzling display believed to warn potential predators. When threatened, these millipedes can secrete a liquid that can even stain human skin!

Despite their fiery appearance, flame leg millipedes are peaceful herbivores. Often found in small groups, they munch on decaying leaves and organic matter, playing a vital role in decomposition and returning nutrients to the soil. Some enthusiasts in the exotic pet hobby claim their legs even glow under blacklight.

The flame leg millipede is classed as "least concern" and is an uncommon but popular pet for insect enthusiasts due to its beautiful colors.

Members of the Ko-fi Club will get a 3in sticker and a collectible trading card!

#art#millipede#flame leg millipede#invert#sticker club#sticker#trading card#cute#monthly#monthly sticker club#palofthemonth#steve and pals#artsyaxolotl

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I saw you have an inbox for arthropod suggestions so here's mine: Typhochlaena seladonia.

Top left: "Brazilian jewel tarantula (Typhochlaena seladonia) is a species of aviculariine tarantula. They are found in Bahia and Sergipe, Brazil in rainforest parts. It is unique as an arboreal spider that constructs trapdoors in the bark of trees. Doesn't really like human contact much. They are generally more docile, although some individuals are particularly defensive."

Top middle: "Purple pink toe or purple tree tarantula (Avicularia purpurea) are mainly present in Ecuador in the Amazon Region. This species can be found in very different habitats, but frequently it is present in agricultural areas, especially in the field of grazing cattle. Sometimes it can be found in holes of walls of buildings or in the spaces below the roofs. They builds their nests primarily in hollows in the trees, sometimes in the vicinity of epiphytic plants. They eat mostly crickets, cockroaches, meal worms, waxworms and darkling beetles, but they also can catch small rodents."

Top right: "Trinidad dwarf tiger (Cyriocosmus elegans) is a New World Terrestrial Tarantula that comes from the tropical climates of Trinidad, Tobago and Venezuela. They are venomous. Also, due to being a such a small tarantula, females have an average lifespan of around 7 years while males tend to only live about 2 years."

Down left: Golden Brown Baboon Spider "Augacephalus breyeri is a species of harpactirine theraphosid spider, found in South Africa, Mozambique and Eswatini. They live in a hole that takes it between five to seven years to construct. They feed on a variety of small invertebrates such as beetles, grasshoppers, millipedes, cockroaches, crickets, and other spiders!"

Down right: "Gooty Sapphire Ornamental Tarantula (Poecilotheria metallica) also known as the peacock tarantula, is an Old World species of tarantula. This is the only blue species of the genus Poecilotheria. Like others in its genus it exhibits an intricate fractal-like pattern on the abdomen. The species' natural habitat is deciduous forest in Andhra Pradesh, in central southern India. They live in holes of tall trees where it makes asymmetric funnel webs. The primary prey consists of various flying insects."

Here's some more tarantula for you guys! Also from now on every species I make will have short description about em. Thank you for suggestion!

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

A writer’s guide to forests: from the poles to the tropics, part 7

Is it no.7 already? Wow. A big shout out to everyone who has had the patients to stick with this. Now onto this week’s forest…

Dry forest

Water is life. That’s a fact. And especially where it doesn’t rain for more than half the year.

Location: Dry forests are scattered throughout the Yucatán peninsula ,South America, various Pacific islands,Australia, Madagascar, and India. Areas have been cleared by human activity, and the SA dry forests are classified as the most threatened tropical forests.

Climate: Temperate to tropical, with just enough rain to sustain trees. Many are monsoonal, with rain coming in one or two brief periods separated by a long dry season.

Plant life- Hardy trees, such as Baobab and Eucalyptus are able to last with little rain by tapping into groundwater with extensive root systems. Many trees are evergreen, but in India, many species are deciduous. Trees are often more spaced out, and shrubs and grasses grow extensively. Cacti are common plants in the Americas, with some growing tall enough to be considered trees. In order to survive the heat and lack of water, many small plants are annuals, or store water in tubers. Palms can make up a large percentage of the trees, as was the case in the now vanished forests of Easter Island.

Animal life- As they can come and go when they please, birds are common species. Larger animals are active year round, with smaller species of mammals, amphibians, and certain insects only coming out during the rainy season. Isolation means that islands become home to many endemic species; think about Madagascar and the lemurs, or Darwin’s finches, iguanas, and tortoises in the Galapagos. Isolation has also led to the marsupials of Australia developing to fill the niches that would normally be occupied by placental mammals .The introduction of invasive species has brought about the extinction of island fauna.

How the forest affects the story- Water, or the lack of will be the biggest challenge your characters will face. Rivers and lakes may be seasonal, so other sources will have to be utilized. Drinkable fluids can be obtained from various plants and animals, or maybe the bedrock is porous and water accumulates in cenotes. Your characters could come from a culture that builds artificial reservoirs to collect the rain and store it for the dry season. With careful water management, cities can thrive in dry areas. But your characters will have to be careful. Prolonged drought will see societies go the way of the Maya. Deforestation leaves the topsoil vulnerable to the wind, and forests, farms, and grassland will inevitably turn to desert. Whether nomadic or sedentary, your characters and their society will have to find a way to interact with the forest without destroying it or themselves. Can they do it? Can a damaged biosphere be restored before it’s too late? The success or failure of your characters and/or their predecessors can be a driving focus of the plot. Of course ,when the rains do come, it could be in the form of a cyclone. Dry ground does not readily absorb water, and flash floods are a danger. Water can grant life, but it can take it as well.

#writing#creative writing#writing guide#writing inspiration#writing prompts#writer#writers#writing community#writer on tumblr#writeblr

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this Margaret Renkl Op-Ed from the New York Times:

Until last fall, when PBS screened “The American Buffalo,” a documentary by Ken Burns, I had no idea bison were native to Middle Tennessee, where I have lived for 37 years. I just assumed that Nashville was part of the great temperate deciduous forests that once covered much of the eastern half of the United States.

I should’ve guessed that the picture was more complicated. When I went looking for the once-endangered Tennessee coneflower in 2019, I found them in a rocky glade surrounded by grasslands blooming with wildflowers. And if there are grasslands here now, surely there must have been grasslands here in the past.

Before the European settlers arrived in North America, the region we know today as the American South was home to seven to 10 million acres of prairie, according to Dwayne Estes, a botanist, professor of biology at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tenn., and executive director of the Southeastern Grasslands Institute, which works to research, preserve and restore native grasslands across the South. Today nearly all those Southern prairies — along with nearly all the other types of Southern grassland ecosystems, and nearly all the plants and animals they supported — are gone.

The scope of this loss of is enormous. Until the early 18th century, the South had up to 120 million acres of grasslands — prairies, savannas, wet meadows, barrens, glades, fens, marshes, coastal dunes, balds and riverscour that collectively supported a truly breathtaking array of plants and animals. In a study published in 2021, a team of scientists including Dr. Estes identified 118 major types of grassland ecosystems in the South. Some are close to extinction.

The most widespread were the savannas, grasslands characterized by scattered trees and a wildflower-rich soil. Historically, what kept young trees from filling the grasslands and turning them into dense, closed-canopy forests were two things: fire and bison (or both). “If you take fire and bison off savanna grasslands, which we did for the first time in world history, they will naturally grow up into trees,” Dr. Estes said in an interview. “They will become what we call artificial forests.” By the end of the 19th century, both bison and fire had been largely eliminated from the Southern landscape.

We know the European settlers chopped down much of the Eastern hardwood forests to harvest timber, but the ecological devastation wrought by a belief in Manifest Destiny didn’t stop with deforestation. The grasslands began to disappear, too, as trappers and settlers slaughtered the bison and suppressed the fire and turned the rich soil into farms.

Between row-crop agriculture, urban sprawl, and the transformation of open woodlands into closed-canopy forests, among other human encroachments, there is almost nothing left of the original grassland ecosystems that once sustained the immense biodiversity of the American South, from tiny insects to grasslands birds to the great buffalo itself. The grassy places we still have — pastures, public parks, highway medians and the like — don’t serve the same ecological function that our native grasslands did. These days, “grass” means species imported from Europe and Asia, monocultures that don’t support diverse plant species or native wildlife.

Today, according to calculations by the Southeastern Grasslands Institute, less than 5 percent of our original grasslands still exist. “Yet the remaining scraps include more grassland plants and animals than the Great Plains and Midwest combined,” notes Janet Marinelli in the publication Yale Environment 360. Preserving these remnants is vital, and not just for the biodiversity they sustain. Grassland remnants tell ecologists what a nearby grasslands-restoration project should look like, and they can serve as seed stock for propagation fields that will in turn provide the seeds needed to return the landscape to itself.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fritter Away with the Mormon Fritillary

The Mormon fritillary (Speyeria mormonia) is a common species of butterfly found throughout western North America. There are multiple subspecies distributed throughout its range, which extends from northern Canada to the southern United States, following the Rocky Mountain range. They are found in a variety of habitats, including alpine grasslands, meadows, and sparse pine forests.

Larval S. mormonia are almost entirely dependent on violets for food, while adults will also feed on milkweeds, thistles, and daisies, as well as mud puddles and animal waste. Birds, rodents, lizards, frogs, spiders, and mantids are all common predators of both caterpillar and adult Mormon fritillaries.

Mating for the Mormon fritillary occurs in mid to late summer. Males regularly search open areas for available females, and following an encounter females lay their fertilized eggs in leaf litter near patches of violets. After about 10 days the eggs hatch, but rather than feeding the caterpillars enter a period of hibernation that lasts throughout the winter. Come spring, they emerge and feed on their host plant for just over a month. Pupation takes 10-12 days, after which they emerge as fully mature adults. In the wild, individuals can live up to 4 years.

S. mormonia are rather small, but brightly colored butterflies. The wingspan for females ranges from 25-27mm (0.98-1.06 in), while males are slightly smaller at 23-26mm (0.9-1.02 in). The top wings of both sexes are orange with black spotting, while the undersides are lighter yellow with white spots, and the body is covered in brown or tan fur.

Conservation status: The Mormon fritillary has not been evaluated by the IUCN, but populations are generally considered to be stable across the US. Its most common threat is the disappearance of its host flower species.

Want to request some art or uncharismatic facts? Just send me proof of donation of any amount to any of the fundraisers on this list, or a Palestinian organization of your choice!

Photos

John Lane

Mark Leppin

David Inouye

#mormon fritillary#Lepidoptera#Nymphalidae#greater fritillaries#butterflies#lepidopterids#insects#arthropods#generalist fauna#generalist arthropods#grasslands#grassland arthropods#deciduous forests#deciduous forest arthropods#mountains#mountain arthropods#north america#western north america#animal facts#biology#zoology#ecology

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

the saffron-billed sparrow is a small member of the new world sparrow family found in argentina, bolivia, brazil, and paraguay. they live in tropical deciduous forests, and feed on fruits, seeds, and insects. the birds’ name comes from their distinct bright orange beaks. males have a distinct black head with a white supercilium and a soft yellow back; females look similar, but are duller in color.

675 notes

·

View notes

Note

fascinating! Different anon here for the for the winter isopod topic. (I'm in Canada, the Canadian Shield region, which is like... Extra rocky taiga mixed with lots of freshwater sources and deciduous forest.)

If the ground is frozen, where would they go? Like, where I'm from, it reliably gets down to -35 celsius (-31 F) every single winter, during it's coldest weeks. For areas not maintained by regular plough schedules (like roads and sidewalks and specific dedicated paths in yards and lawns), we get a lot of snow and ice buildup. (Even then, sidewalks and paths get build ups of ice. Roads are usually fine because of industrial metal scrapers on the ploughs but even then.) By the end of the winter, despite the constant upkeep of dedicated paths within our yard in order to minimize the amount of snow one sinks in when walking around, there's still a solid foot and a half of snow and ice underfoot, that's been incredibly compressed by the usage of the path. For areas not upkept, they are oftentimes dedicated as "dumping grounds" for snow we need to displace, so it builds up a lot. We get huge snow banks on the sidewalks, I'm talking taller than people and cars. It doesn't get that high in our yard, around four feet on average.

Our temperatures fluctuate a lot as well, and that causes melting, which the ground absorbs. Which freezes up the next time the temperature drops. I'd say at most a solid foot into the ground, it freezes. This oscillation of the temperature also causes there to be different layers and levels of consistency within the snow, as well as causing it to move around and shift and morph into new cracks and crevices and spots.

So with all of that in mind, where the hell would the isopods go? You mentioned under rocks warmed by sun, but where I'm from, rocks loose enough to provide any kind of crawlspace, rocks that aren't anchored in the ground, those easily get congealed within ice. Basically, if you plan on using or moving an item, you better move it before late october, after which it risks being trapped and abused by the weather conditions.

I suppose shelter can be found within the thick buildups of needles under especially large coniferous trees, where snow and ice has a harder time penetrating and freezing to the core. And also human buildings would help too- like where we keep all of our firewood, we keep it clear of snow so that the logs don't rot or get frozen together.

I'm just amazed, honestly, that things like isopods and centipedes and ant colonies can survive and endure such harsh conditions for so long.

Crazy

if it’s any explanation, there don’t appear to be isopods in most of the area you described (map is off iNaturalist.) isopods are livebearing animals that can’t go dormant in egg or pupa form like insects can, so extreme cold is definitely a limiting factor in where they can exist. keep in mind also that most large North American isopods are invasive species from temperate Europe, so aren’t adapted to extreme northern environments in the first place.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

November 3rd, 2023

Giant Swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes)

Distribution: Found across the United States, up to southern Canada and down to Mexico, Jamaica and Cuba.

Habitat: Mainly found in deciduous forests and citrus orchards.

Diet: Adults feed on nectar and the liquid from animal waste; plants fed on include lantana, azalea, bougainvillea, soapwort, dame's rocket, goldenrod, Japanese honeysuckle and milkweed. Caterpillars feed on the leaves of plants in the citrus family.

Description: The giant swallowtail's larva is also called the orange puppy due to the fact that it's a pest of citrus trees, including orange trees. In order to protect itself from predators, the caterpillar camouflages itself by imitating the appearance of bird or lizard poop. If this doesn't fool a predator, it has a trick up its sleeve—or more accurately, its head; it can deploy an osmeteria, which is a brightly-colored Y-shaped growth, whose appearance is often accompanied by a strong, foul odour. This only really works to startle smaller predators, though, such as lizards and other insects.

Due to global warming, the giant swallowtail's range has gradually expanded northward. However, they're still only able to overwinter in areas of the deep south. They can be spotted fairly easily—adults have a wingspan of up to 19 centimetres, making the giant swallowtail the largest butterfly in North America!

(Pictures by D. Gordon E. Robertson and Lanare Sevi)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lar gibbon also known as the white handed gibbon is an endangered primate in the gibbon family, Hylobatidae which is native throughout Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, China, Myanmar, Burma, Thailand, and Northern Sumatra. They sport the largest contiguous range of any gibbon species and typically inhabit lowland and submontane rainforest, mixed deciduous bamboo forest, and seasonal evergreen forest.They are a diurnal, arboreal, and social species which lives in familial groups comprised of a mated pair or polyandrous group and there young offspring which often communicate via there loud & distinctive calls. The diet is comprised mostly of fruit, leaves, flowers, vines, insects, and eggs. Lar gibbons are themselves eaten by tigers, clouded leopards, marbled cats, crested serpent eagles, and reticulated pythons. Both sexes reach around 16 – 24in (41 -61cms) in head to body length and 8-17lbs (3.6 -7.7kg) in weight. As gibbons they are true brachiators, propelling themselves through the forest by swinging under the branches using their arms. Reflecting this mode of locomotion, the lar gibbon has curved fingers, elongated hands, extremely long arms and relatively short legs. The fur of this animal can vary from dark brown to ginger, tan, or cream in coloration. Its face is black, with a distinct white ring of hair around it. Its hands and feet are also white. Mating may occur year round but typically peaks during the dry season around March, after a 6-7 month pregnancy a mother lar gibbon will give birth to a single baby. For the first 4 to 6 months of its life, the infant is nursed and carried around by its mother. She then carries it around less and less, and it begins eating solid food, before becoming fully weaned by 2 years old. After weaning it is primarily cared for by its older siblings, and after 3 years it in turn starts caring for its younger siblings as well. Lar gibbons reach sexual maturity between 6 to 9 years of age at which point they leave there familial group in search of mates. Under ideal conditions a lar gibbon may live upwards of 25 years.

#animal#animals#lar gibbon#gibbon#ape#primate#pleistocene#pleistocene pride#white handed gibbon#white hand gibbon#asian#asia

90 notes

·

View notes