#but the author is a black american and i did find this novel in my librarys afrofuturism section. so. ill go with it.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Prey of Gods

by Nicky Drayden

This is an Afrofuturist novel that weaves together elements of sci-fi and fantasy to create a story of five main characters, who are tangled up in the dangerous, fantastical rise of the old gods.

My Rating: 4/5

If I had to describe this in the simplest way possible, I'd say that the book was really fun to read! You get to follow five characters who are VERY different from one another, and see how somehow their paths intersect into this crazy, larger-than-life story, and end up in ways that they absolutely could never anticipate in their wildest dreams. There are so many twists and turns of varying levels of hilarity, absurdity, and questionability, and it can get so weird, in ways where you really have to have fun with it and go along for the ride.

I ultimately did enjoy this book a lot, but I wasn't confident enough in my liking of this book to give it a 5/5; I also have some criticisms which I feel were substantial enough to knock it down to a 4/5 at least for me.

Content warnings (which might be spoilery) and full review under the cut!

The content warnings for this book include death, sexual assault (including brief depictions of SA on children), child abuse, animal death, drug use, medical procedures, and torture.

Let's start with what I liked about this book, of which there was a lot. One specific thing I want to shout out is the author's ability to develop character voice. Giving five different POV characters a unique voice is hard, but Drayden does it and she does it well. I especially like a lot of the chapters in the POV of Nomvula, who is a child, somewhere between 6-10 years old (I can't quite remember). Nomvula genuinely narrates like a child - a child that has been through a lot of trauma and hardships, sure, a child with strong moral fiber, but a child nonetheless. Other POVs that are worth mentioning are Muzi, a teenage boy, and Stoker, a politician - their character voices both reflect their respective personalities and way of speaking based on their ages and roles in society.

Drayden's writing style was unique, in a way I almost struggle to describe, because while its not flowery or prosaic, I also feel like "concise" is the wrong word to use. It's crisp but it's also very animated, which ties into what I said earlier about her strong character voice. It adds to the overall funky vibe of the story, and helps the book stand out against those written by authors who employ a more traditional, typical style of writing.

The plot itself has a lot of fun twists and turns, including a more sci-fi plotline that I won't reveal to you. From the start, the book is weird, and I mean that in a positive way. You have to laugh and enjoy the absurdity of some of the things written, and the good thing is that those absurd sounding things still tie into the plotline, and make sense later. Speaking of plotlines, one of the fun things to see is how the five characters become involved in the same crazy events by the end of the novel. Even at the beginning of the novel, there are tiny threads that show how the characters are loosely connected to each other; by the time the action ramps up, the five characters are at the heat of the conflict, probably wondering how the hell they ended up here.

Each character came from a unique background, and it is a very diverse cast in terms of race and other identities - there are gay characters, trans characters, and disabled characters. I think plugging diversity as a feature of a story can be dicey, because I think that runs the risk of tokenism, but in this story the characters and their various identities are done well - their experiences aren't angst fodder, but they do impact the characters and therefore the whole story in profound ways. There isn't any in-your-face messaging about their identities or any other social issue, for that matter, which I think is important because ultimately, our identities are deeply personal and should mean more for a character than just being a way to preach to the audience.

So while the majority of the things I have to say about this book are positive, there are some things I didn't love that I do have to mention.

One thing is that while I appreciated the author's brisk writing style, I do think it led to certain pitfalls when it came to character development or introspection. There were several instances in this book where I felt like a character changed their mind on a certain thing or had "character development" so quickly that it gave me whiplash. I didn't feel like there was very good buildup to all of these character developing moments - quite literally I felt as if someone had snapped their fingers and the character had changed their mind. I was able to overlook it because I enjoyed the overall story, but I really wish that the author had allowed for more gradual development and introspection for the characters. I attribute this to the writing style because I feel like the way Drayden writes really isn't introspective in general - the text doesn't really try to get deep into the characters' heads, which is fine, but there are some parts where this is sorely needed. There is one specific scene where the change in a side character's attitude to one of the main characters was so abrupt that I think it was, plainly, just badly written, but I won't say more because spoilers.

There were also one specific thing that peeved me enough to mention it here, which is that at one point in the second half of the book, Nomvula, the character who is under 10 years old, starts talking to older characters in a way that's very "wise beyond her ages". There's no reason for this to occur, especially since in previous chapters she clearly talks like a child. I absolutely detest child characters talking like adults, and it makes zero sense to me that Nomvula would start acting like another character's emergency therapist, talking about grief or some shit, while she is quite literally fighting for her life and also about seven years old.

In general, I think that there were certain heavier topics that the book should have addressed with more deliberation and depth. For example, one character is a politician, and while the book's main purpose isn't social commentary, there's clear corruption and all sorts of political mishappenings in the government they work in. Given that, I think the way the author wrote their political career and attitudes towards politics came across as naive - the character had a level of sincerity and optimism towards politics and the governing system that definitely doesn't exist in real life. This is just one example - there are other aspects of both character and world-building that I think should have been explored more to give the story additional depth.

Overall, though, I think this is a good book that I'd recommend to anyone who likes interesting, funky types of storytelling. I think it's important to read these sort of non-traditional styles to make sure we aren't bound by made up constraints of genre or any other standard we have for "good writing", and this book in particular created a fun and compelling narrative that I think can be enjoyed by a wide group of people.

#the prey of gods#book review#bookblr#scifi books#fantasy books#lgbtq books#queer lit#i wont lie im not 100% certain about my use of the term afrofuturism#because definitions seem to say its related to african diaspora and technically the story takes place in south africa#but the author is a black american and i did find this novel in my librarys afrofuturism section. so. ill go with it.#some articles refer to black panther as afrofuturist. so. im not certain. but im keeping it in. let me know if i shouldnt.

1 note

·

View note

Text

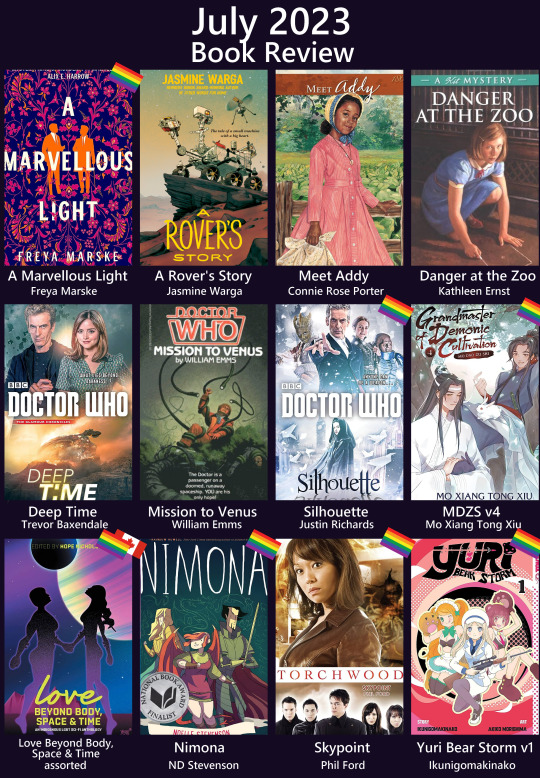

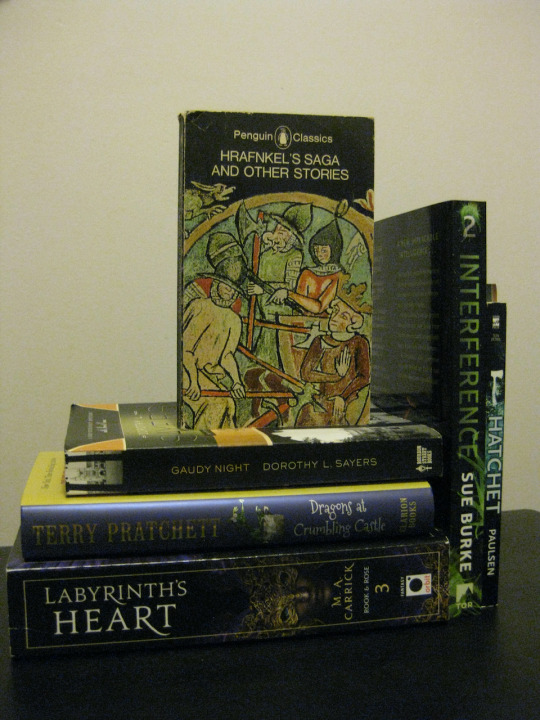

reading updates: april 2025

HI wow what a month! 2025 felt like it was going REAL FAST until about mid-March, and ever since then it's slowed to a sort of molasses. despite the seeming influx of extra time I read much less in April than I have in any of the previous months this year - this is the first month I haven't even cracked double digits! which is fine, of course, it's not a competition, but it is interesting to think about what slowed me down so drastically.

(just kidding, it's not a mystery. it's heaps and heaps of stress. oops!)

ANYWAY. fortunately April's book haul has largely been a case of quality of over quantity, introducing me to several books that I think are guaranteed to land on my year-end best-of list. without further ado:

what have I been reading?

Under the Skin: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and on the Health of Our Nation (Linda Villarosa, 2022) - I checked this book out last month alongside Dr. Uché Blackstock's memoir, Legacy: A Black Physician Reckons With Racism in Medicine, as kind of a mini-series on racial bias in the American medical system. while I feel like I broadly learned more overall from Villarosa, thanks to her taking a journalistic approach that allows for a broader scope than Blackstock can achieve by primarily focusing on her personal experiences, I found that the two books complemented each other extremely well and each served to bolster and deepen the other. one major advantage of Villarosa's work is the geographic variability and the ability to meet healthcare workers and patients from a much wider range of places than Blackstock's New York hospitals, with particular focus on poor communities in southern states. Villarosa's writing has a strong, compassionate, deeply curious voice that makes her subjects incredibly vivid, rendering them with dignity even as their medical nightmares are laid bare. it was an incredible read and one that had been languishing on my TBR for a while, and I'm very glad I finally made the time.

Earthlings (Sayaka Murata, 2018, trans. Ginny Tapley Takemori, 2020) - while I didn't love this novel quite as much as Murata's briefer wonder, Convenience Store Woman, it did cement Murata as an author whose work absolutely fascinates me. her grasp of trauma and alienation is incredible, and she has a way of depicting unconventional desire in a way that's unlike anything I've ever seen. I'm supremely excited to read more of her work.

The Love Hypothesis (Ali Hazelwood, 2021) - in case you haven't already heard the news: I read the alleged Reylo laboratory AU romance novel expecting to be a big hater and I ended up loving it. joke's on me! you win this round, Ali Hazelwood.

Crying in H Mart (Michelle Zauner, 2021) - listen: you never want to be the guy saying that a woman's memoir about losing her mother to a painful and sudden cancer isn't that sad. to be clear, it is an extremely sad book! Zauner does an incredible job rendering the all-consuming pain of nursing her mother through her final days, a pain devastatingly unique to everyone who experiences it. in this case, the biracial Zauner also has the daunting sense of losing not only her mother but also a core part of her identity, struggling to figure out how to be a Korean American woman without the connection her mother provided. it's a tragedy! it's several tragedies all in one place, make no mistake! but I also feel like I've spent YEARS hearing this book hyped up as The Saddest Book Ever, and perhaps I've just read too many sad memoirs but it was like. it was fine. it's just fine. solid B+, not mad I read it, but I have read sadder. probably I am going to hell for this.

Liquid: A Love Story (Mariam Rahmani, 2025) - I was super excited for Rahmani's debut novel, which has a compelling premise: stuck in a stagnating academic career and with her parents nagging her to wed, an unnamed queer Iranian-American woman decides to go on 100 dates across Los Angeles to find a likely candidate for a marriage that can bring her financial security. her plans inevitably go awry when a family tragedy requires her to travel to Iran, where her goals are brought more sharply into focus - and she ultimately resolves her romantic quandary. it's a stylish book, almost painfully so; I can't say I'd recommend this to anyone who dislikes literary fiction because GOD is this Literary Fiction, our protagonist deeply preoccupied with her own witty malaise and caustic observations. she's a little awful and I liked her a lot, but I also think that the resolution Rahmani brings her protagonist to was devastatingly expected - and unfortunately, no amount of self-aware lampshading actually makes it less predictable. I'm conflicted! it felt like a lot of building up to not a lot of payoff, but I'm compelled all the same and I'm hoping to see more of Rahmani in the future.

Before We Were Trans: A New History of Gender (Kit Heyam, 2022) - god, what a delight of a book. Heyam takes a gorgeously open approach to what constitutes "trans history", casting their net wide to recognize gender nonconformity far beyond contemporary understandings of what it means to be transgender. Heyam advocates for a wide recognition of experiences throughout history: people whose gender identities were shaped by non-Western religions and cultures, those whose identities blurred between same-gender attraction and a desire to be recognized as a different gender than the one expected of them, those whose transgressions of gendered boundaries can't be proven to be align strictly with 21st century ideas of transness. Heyam's approach is one of radical inclusiveness, seeking not to "prove" any particular understandings of transness in historical figures but simply to point at a long, global history of people living outside of a gender binary and weave all of these instances together in the understanding that all of these experiences support and bolster each other in affirming that across time, language, and culture, people bucking gender norms have always existed. reading this book felt like holding a mug of hot chocolate.

Afterparties (Anthony Veasna So, 2021) - genuinely impossible for me to talk about this short story collection without acknowledging that it was published posthumously by So's mother and partner after he died very young. I will freely admit that the first story did not grab me, and since I'm fussy about short stories I might well have set down the book after that if not for the strange sense that I was holding a small representation of a man's life in my hands. I guess that's always the case with a book, but somehow it felt extra sharp here. in any case, I'm glad I stuck it out; So's stories about Cambodian immigrant communities in California are messy and loving and sorrowful and silly, delving deep into the sadness that can cling to a family for generations. I'd be absolutely remiss not to pay particular attention to the final story, "Generational Differences," in which So writes from the point of view of his own mother, talking to his child self and recounting a tragedy. it's a brave and vulnerable approach that I've never encountered before, and it's really something special.

an obligatory update on my book bingo sheets: as usual, the sheet that I'm filling in opportunistically is thriving, with the addition of Liquid completing another bingo and getting me very close to two more

and the list of books that I specifically planned out is LANGUISHING

finger crossed for May, when I'm hoping to cross at least two more off the list...

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

purple haze // charles leclerc

summary: writing a novel is a long an arduous process. luckily for y/n, she has a very supportive partner in crime, and when it all works out, he's the only person she would want by her side.

pairing: charles leclerc x author reader

warnings: alcohol consumption, talk of deadlines, book referenced is a good girls guide to murder by holly jackson. gets a lil steamy towards the middle but nothing comes of it. still not sure how i feel about this one, but i havent written for charles in forever and i got an idea i really liked but i don't know if it worked out when i put it on paper.

by the time y/n closed her laptop, she felt like her fingers were going to fall off. she leaned back in her desk chair, gutted to find that the monaco cityscape outside her living room window was now pitch black, as might had fallen on the city.

her first book had been a red-wine and oasis fuelled fever dream, the last three chapters being written to ‘don’t look back in anger’. and now, the final edits were done.

“I’m so proud of you, mon tresor.” charles gushed, bringing her another glass of wine.

“the last three years are finally paying off. a good girls guide to murder is done, and the world is ready to meet pippa and ravi.” she grinned, clinking her glass against her boyfriends.

she had poured three years of her life into that book, and Charles had been by her side for all of it. through numerous rejections, edits and late night idea-vomit, nobody was prouder than charles was so see it work out for her.

and now he knew she needed a break.

taking her hand in his, he gently dragged her out of the desk chair and towards the couch, placing their wineglasses on the coffee table as he urged y/n to sit on the ground between his legs.

his hands were warm as he began to massage her shoulders, attempting to release the tension caused by the last round of edits, which she had worked on almost from sunup to sundown.

“there’s still so much to do.” she whined, tilting her head back to look up at her lover. “now there’s arcs and extra promotions and finding advance reviewers and-“

charles cut her off with a kiss. “none of that right now. right now, you and me are going to finish this bottle of wine and watch something pointless on tv.”

smiling to herself, y/n got up from the floor and moved to the leather couch, slipping seamlessly into charles' lap and nestling against his chest. his body was warm, and his sweater soft. even if his cologne was a little bit too strong, he made her feel safe. treasured.

"that sounds perfect." she hummed, gently turning his face so she could kiss him. "thank you for supporting me."

"always, my love." charles smiled before kissing her again.

SIX MONTHS LATER

it was half past five in the morning when the phone rang. charles could sleep through just about anything, but it was the vibrations of the phone against her side table that woke y/n.

she looked over at her sleeping lover, pressing a gentle kiss to the smooth skin on his shoulder blades before slipping out of bed and creeping into the hallway to answer a call from her agent, cecelia.

"cece, its five in the morning. couldn't this have waited?"

ceclia cleared her throat. "i've just heard from the american office. the preliminary numbers for the new york times list are in."

"fuck. how did we do?" she closed her eyes, holding up her crossed fingers and praying to every god she wasn't sure she believed in.

and when cecelia spoke again, she almost dropped her phone.

"okay. thank you for letting me know, cece."

she slipped back into the bedroom, bare, dry feet sinking into the plush carpet at the end of the bed before she sat down at the end of the bed, gripping the phone so tightly that her knuckles had gone white.

"mon amour." charles rasped, exhaustion in his voice as he rolled over onto his back. "what's wrong?"

"i just got a call from cecelia." she started, trying not to let her emotions show through. "she's just been on the phone with our american agent with the new york times numbers."

charles sat up, one of his warm hands going to rest on her thigh. "and?' he asked hesitantly, his piercing eyes meeting her uncertain ones in the dark.

"i made the top ten." she shouted, grin spreading all across her features.

making the new york times list had made everything worth it. all the sleepless nights when she had woken up with an idea she was scared to lose, all the rewrites, the weeks of writers block. the rejections, the aggravation, the insecurity.

this was it.

she had done it.

"i'm so proud of you." charles beamed, folding her into a hug. "i knew you could do it, my brilliant girl."

she dropped her phone on the bed, red-faced and giggly as she kissed him, allowing her hands to wander across his toned chest. "wanna show me just how much?"

THREE YEARS LATER

the theater was almost silent when the lights came up, the end credits of the final episode fading out on the screen. she held her breath, fingers gripping charles' hand so tightly that she thought she might break the fragile bones in her husband's fingers.

oh, yeah. they had gotten married about a year after her book had come out, while she was in the middle of writing as good as dead, the conclusion to the series.

since a good girls guide to murder had come out, her life had changed for the better. she felt more secure in herself and her talent, and the words had never come easier when she started writing the sequel, eager ton continue the story. she had since written two more books to complete the trilogy, as well as two standalone novels: five survive and the reappearance of rachel price. around the time that rachel price was announced, she had gotten another call from cecelia, asking if she and charles could come to london and meet with representatives from the bbc.

they wanted to turn her first book into a tv series.

she had been hands on from the beginning, throwing herself into her work and doing her best to make sure that the version of the story the readers saw on screen was the version that she had visualized when she'd first explained the storyboard to charles, the driver helping her connect everything on their living room wall with red yarn.

and now was the time. the time to see if it had all paid off. the theater was filled with minor celebrities, influencers, and the tiktokers who had made her book blow up in popularity.

it all came down this night.

"it's okay. whatever happens, you know you did your best." charles whispered in her ear, running one hand up and down her bare back. underneath the flimsy straps of her red dress.

she closed her eyes, taking a deep breath when the roar off applause began to drown her.

she rode the rush of emotions, allowing the tears of gratification and relief to ruin her mascara as she let her body go slack, resting against charles as she watched the room rise in a standing ovation for pippa and ravi.

"we did it. we made it, charles." she laughed, tilting her head up to kiss him.

"no, cherie. you did this. they're all here for you."

she watched as the event's host, a former spice girl that charles knew through his paddock connections, stepped out into the middle of the small stage set up at the front of the theater.

"and now, the moment i'm sure you've all been waiting for, a few words from y/n /y/l/n-leclerc!"

she wiped her eyes and fixed her hair, taking a deep breath before she walked across the stage, taking the microphone from geri halliwell, and turning to face the crowd.

in the front row, there was charles. her one true love. her biggest supporter.

and in that moment, she truly allowed herself to believe that she had made it.

#charles leclerc x reader#formula one x reader#f1 iagine#f1 x reader#f1 one shot#charles leclerc imagine#charles leclerc x you#Spotify

314 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am genuinely asking this question and I do not in any way mean it as a “gotcha” or trying to discourage the way you or anyone views THG characters: why do you believe the Seam families are canonically people of color? I completely understand the headcanon and think it enriches the political world of THG but I just don’t give Suzanne that much credit and I think it’s even more obvious with the way she ran as far away from that interpretation as possible in Sotr while giving confirmation to literally every other headcanon the fans have come up with. again I’m not saying this in a “you should stop thinking this” kind of way I’m asking the opposite, what am I missing? because I’ve seen lots of people say Lionsgate white washed the Everdeens, Haymitch and Gale but were they ever actually not white? Suzanne is just way too much of a pussy for me to believe she’d take the risk of alienating her self insert white audience like that. If this question comes off in a condescending tone or an accusatory “they’re all white stop diversifying it tone” please just ignore it because it’d be a fault in my writing style not my genuine intentions but i wanted to ask you specifically because (well you’re a very articulate person and) i remember you saying that Suzanne shouldn’t have made Haymitch an alcoholic because of the negative stereotype already associated with Native American men (i hope i’m remembering that right) which would make complete sense if they’re confirmed to be Native but i don’t recall her ever admitting to that. I feel like fans (not you i’ve followed you long enough to know you know her better) really wanna see Suzanne as this revolutionary author who’s a political genius and stands for marginalized communities when she’s very much just writing a regular YA novels and put the blame of all white leads on outside sources rather than her

i can’t say this enough i’m not suggesting the characters should be white, I prefer the Native American interpretation of the Seam families, the Covey are clearly (it’s the one thing i will give SC credit for) Romani, and when you said Finnick was clearly a man of color because of the imbalanced rates of sex trafficking among races it made me feel like an idiot for not realizing it before! ugh i really really hope this question doesn’t sound cruel or condescending

I’ll be honest, my answer to this question would’ve been very different pre sotr…I think in the original trilogy they’re people of color. I think SC then retconned that because she wants to pander to as wide of an audience as possible and make as much money as she can, and she did that by erasing the racial and class tensions she alluded to in the original trilogy. I don’t subscribe to this bootlicking thing and I definitely don’t think she’s a political genius (you nailed me on that for sure lol), I actually think she’s quite spineless and only cares about marginalized communities in the laziest possible fashion and just so far as she can use their portrayals in her work to make more money. I do find it upsetting that she capitulated and backed away from something as basic as a physical description of Haymitch in sotr when those descriptions are so prominent in the original trilogy, just to better align with the movie casting.

personally, this is the evidence I use. the people from the Seam are physically described to have olive skin and black hair many times. yes, phenotypic variation, but District 12 is located in an area with a large indigenous population, and I think more tellingly Seam people are frequently contrasted with the Town people who have light hair, skin, and eyes. SC leans more heavily on class divides than racial divides in the world of thg, but I also think about the ostracization and what seemed to be the enormous shakeup that happened with Katniss’s parents when they were married. this could be because of class differences, but that type of backlash is seen much more frequently with interracial couples. it’s also undeniable that in the United States today, yeah, there’s class divides between different groups of white people, but structural racism and inequality has made it so that class divides between white people and people of color are generally very pronounced. The fact that people from Town are wealthier, more established with generational businesses, and light skinned, while people from the Seam are olive skinned, the ones who perform backbreaking physical labor, and very poor to me suggests a class divide that’s also along racial lines.

In addition, a lot of the struggles portrayed in the Seam echo a lot of the preexisting struggles and barriers that are found on reservations and in primarily native towns/villages today. Lack of access to food, enormous and disproportionate poverty, no or very limited healthcare, and substance abuse issues are all things that plague indigenous communities and are included as present issues with Seamfolk. I also think Katniss and Gale’s reliance on a subsistence lifestyle as a way to provide for their families is something she sort of threw in that codes them as native, which is. I have feelings about that but this response is already really long.

I also want to add the caveat to all this that a lot of what people read into as evidence of people from the Seam being indigenous is based on lazy and often racist stereotypes by SC, as this anon pointed out, and so it should be looked at critically with the eye that this is a very privileged author who couldn’t commit to making her characters people of color, decided to just allude to it for decades, and then completely backed away from it.

#ask and you shall receive#lovely anon#thg#glad to hear that speaking about the disproportionate rates of sex trafficking in marginalized communities was an eye opener for you!!!#please don’t feel dumb about it we can all learn and grow for sure. but I think anon you and I are definitely of the same mind here and I#really appreciate how respectful this question was#long post#idk also. this isn’t in the body of the post but also it pissed me off that she made Haymitch an alcoholic. that’s an example of something#I think on her part was a lazy stereotype

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, dear Angela! I'm a huge fan of Just Say Yes fanfiction, I'm re-reading it, for me it's a powerful comfort novel that soothes me, makes me smile, laugh and cry - these are good tears, not the kind I shed during Banana Fish, those were the kind of tears where you would ask others close to you: why haven't you shot me down and ended my suffering? XD My question to you would be, after Just Say Yes, how do you envision Ash and Eiji's life going on, what direction will their life together take, and how will they continue to grow together? You're one of my all-time favourite authors with amazing talent, imagination and writing skills and I hope to read more of your novels in the future.

Thank you! This wonderful feedback on my story has really made my day! The fact that it's soothing, as well as entertaining, is really significant for me--I write to entertain, so it's like a super-extra thing that it also can bring you comfort. <3<3<3

So you want to know what would happen to Ash and Eiji after "Just Say Yes"? That's such a fun thing for me to contemplate!

Well, first of all, Eiji jumped straight into training again. He and Jill worked hard to get him back into Olympics shape (his fondness for working out made this easy!). He made it to Paris in June and did his best and won gold! Ash (who applied for a passport right after the end of the fic) went with him, and was able to cheer him on. Eiji kept going and, four years later in 2028, he won silver at the Los Angeles Games. After that, he retired from the pole vault on his own terms.

Kenichi gave him his job back at Dainobu, so he stayed employed there this whole time. Once he retired, however, his photography career really took off. He did gallery shows and was featured in magazines and art publications, and he became a bit of minor celebrity in the Manhattan art scene.

Ash finished school. After that, he was at loose ends for a while. He applied for a government economics job, but some agents showed up to explain why he was absolutely never going to get any kind of job that required any level of security clearance. This pissed him off and he got a bit reckless for a few months, but Eiji was able to reel him in. Together, they brainstormed other career options, and then Max ended up knowing a guy who was the head editor of a serious business/economics magazine. Ash got a job writing articles.

After about a decade of getting really great attention for his articles, Ash turned to writing books about the American and global economy, and eventually, representatives the US government came to see him again, this time to offer him an advisory role with the executive branch. Ash turns it down, because he wants to stay in New York with Eiji. "DC can go fuck itself," he said.

About a year after JSY, Eiji finds a dog in the park. He tries for weeks to find the dog's owner, but eventually Eiji decides just to keep him. Ash thinks the apartment is very small for a dog, but he can't say no to Eiji and the dog (Buddy) settles into their lives. When Eiji is away for competitions, Ash can be seen letting Buddy yank him around the neighborhood on a leash. After one of his trips, Eiji comes home to find a tiny black tuxedo kitten sleeping on Ash's pillow. Apparently, Ash found her in dumpster. He named her Harper after Harper Lee.

I could go on forever, especially if I go into the side characters (Shorter and Sunny's wedding, Nadia's baby, etc.), but I think this should be enough right now. You've made me very happy, asking a question like this. I've really enjoyed writing this out! <3

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

because i was a young kid surrounded by all the women in my family who had careers teaching language i would come across the weirdest fucking books in my library that i would read out of pure boredom and that is how i came to be weirdly well read for my age.

here are some of the books that i read which i wouldnt have expected to read and yet i did.

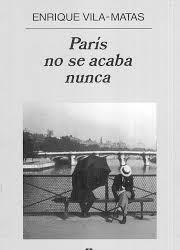

paris never ends

an autobiographical account of an artist who studied in paris in the seventies. the guy talks a lot about the artistic scene in paris in the times of hemmingway and gertrude stein. i have no idea how i got through it all but i somehow did

the locked room

a book about the life of a man who, after his best friend dissapears, becomes the inheritor of his works and starts publishing them, afterwards he becomes obsessed with the guy and starts trying to find him again

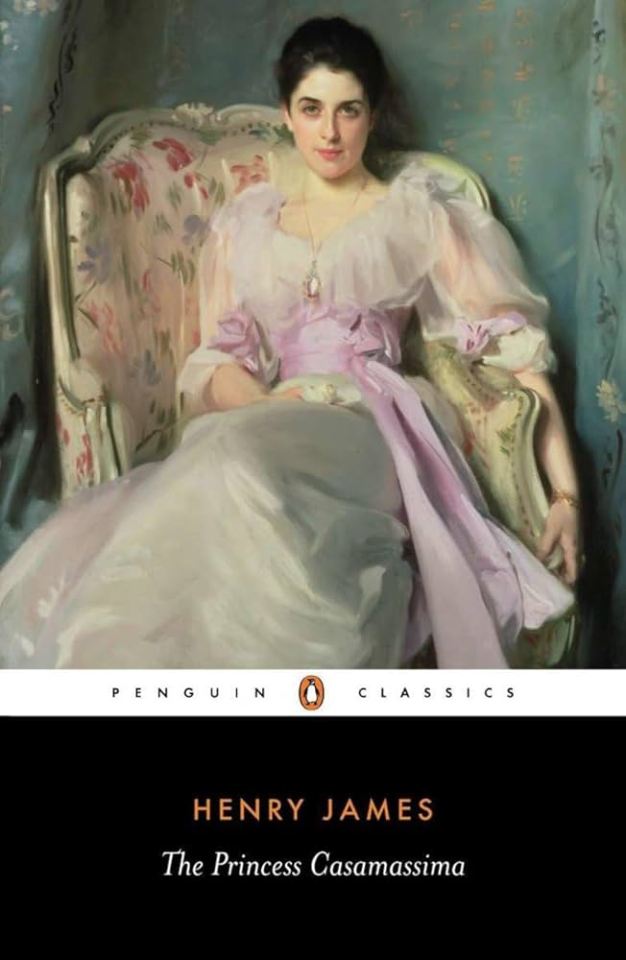

princess casamassima

a book about a young man, i think a revolutionary, who becomes infatuated with an aristocrat lady and who gets his heart broken by her. this one is particularly baffling because i remember this book being boring as shit and yet i couldnt stop reading it in the hopes that something interesting would happen, i think i read this thing at a time i didnt have internet

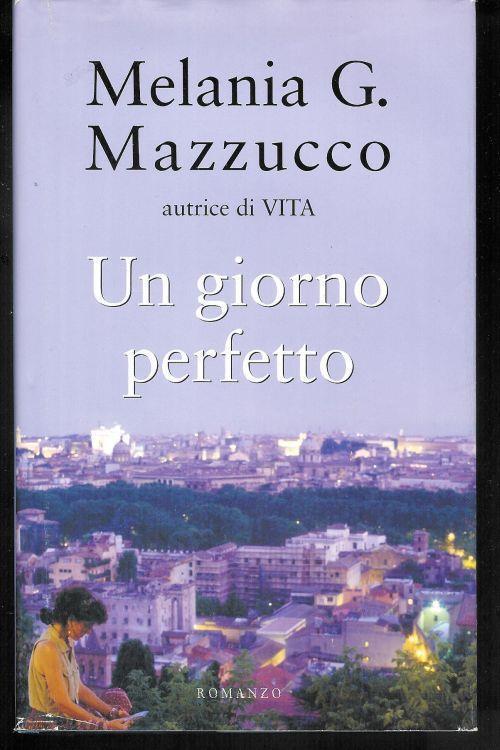

a perfect day

a depressing book with an ambiguously depressing ending. a very italian book, which with me being argentinian it was like reading abou my second cousins. it really well written and all the different plots come together fascinatingly so but again, sad ending. at the time it left me really angry

go fast, run far

a fascinating little crime thriller with lots of personality and charisma about a serial killer who kills by bringing back the black plague. it brushes on fantasy and a bit of sci fi a little, but only very slightly.

all the names

i read A LOT of saramago because my mom and my grandma were obssesed with the guy. i read essay on blindness, its sequel essay on lucidity and the gospel according to jesus christ. each one a master piece, saramago, next to borges, is probably one of my favourite "literary" authors. all the names is particularly fascinating because of how boring it sounds at a first brush. a guy working at the civil registry of births and deaths comes across the file of a young woman and he becomes obsessed with her, to the point that once he sees her death certificate he snaks into his own offices at night to change the file back to make her stay alive. the way its all descrived is so engrossing and absorbing that you cannot put the book down

the words

i discovered sartre first as a philosopher and at the time (12 years old) he was my favourite philosopher by far. existentialism is very seductive to a teenager. it wasnt until much later that i rediscovered him as a novelist and playwright with the cog. but it was this book in particular the swept me off my feet. he descrives his own chilhood as a nerdy shy introverted kid obsessed with jules verne, as a nerdy, shy introverted kid obsessed with jules verne myself i fell in love with this book instantly. it was the first time i truly realized that people from very different countries and very different time periods can form a powerful connection based on their shared humanity.

the tunnel

not much to say here, it is a very simple book about an obsessive old man (im starting to notice a pattern here) written by one of argentina's most popular authors ernesto sabato. i remember it being easy to read but i forgot basically all of it

the invention of morel

a surprisingly engaging science fiction. you know how you will see stuffy old books in your mom's library and they are from some obscure latin american writer and you are like "it will probably be some impenetrable rummiation on life tinged with magical realism elements"? well this is not that type of book, a great, straight forward mystery science fiction novel. incredibly entertaining and with a fantastic twist at the end

noone writes to the colonel

another fantastically boring book, only beat in terms of sheer fucking mindnumbing boredom by hemmingways the old man and the sea. nothing fucking happens and the nothing that doesnt happen is descrived with the spark and the enthusiasm of a cracker dipped in room temperature water. the only interesting thing in the entire book is the very last sentence and its not worth it.

the adventures of greenbeard

now this book on the other hand is a fucking blast. imagine the superhero genre filtered through the thickest, most whimsical layer of sheer latin american magical realism. its a very silly and fun book. it plays with the concept of the super villain, the mad scientist, the intrepid reporter, the dashing hero and the action scene in ways that pay no heed to the conventions of the genre and does its own unique thing instead. perhaps a bit too cute by half and the gender and sex politics of it are a bit... uh, confusing? but regardless some of the most fun i had reading a book in my life

stories of cronopios and famas

finishing this list with the biggest classic here, i dont think i need to introduce cortazar to you guys. a fantastically funny, endearing and whimsical examination of the strange creatures known as cronopios, famas and esperanzas. i should also mention the other books of his i enjoyed instruction manual and the astronauts of the cosmoroute

conclussion:

im glad i read these books, even the ones that i didnt like, im glad i got to expand my horizons and get a wider perspective on what literature and stories can be. im genuenly kind of proud of myself that i actually was willing to go this far outside my comfort zone and pleasantly surprised that i had the capacity to do so.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

REVIEWS OF THE WEEK!

Every week I will post various reviews I've written so far in 2024. You can check out my Goodreads for more up-to-date reviews HERE. You can friend me on Goodreads here.

Have you read any of these? What were your thoughts?

___

337. Gameboard of the Gods by Richelle Mead--⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

I finished GAMEBOARD OF THE GODS and immediately came onto Goodreads to see how the rest of the series was and if they would be nearly impossible to buy because it was an older one...only to find that Mead never had book 3 published. So...I'm never going to read book two, sadly, because I don't want to be left hoping.

And it truly is too bad because this was an entertaining read! It was definitely a product of its time--meaning it came out when this genre was very popular in fantasy. I can think of a few series that this reminded me of, but this one had more of a dystopic feel.

For all intents and purposes, this is a detective novel set in a dystopia, featuring a badass FMC and a down-on-his-luck-but-very-smart-and-persuasive man. This type of duo was not uncommon in the 2010s, so I'm surprised this one didn't take off like Mead's prior big series. Maybe it was the wrong time to jump from YA to Adult Fantasy.

I liked the mystery and the character dynamics. Everyone worked off each other so well and there were some reveals that were pretty impactful. The banter between the characters was entertaining, and their sexual chemistry was pretty great too--this was a lot spicier than I expected (and though we don't get a lot of spicy scenes, the ones we got were only spicy to me because I wasn't expecting it in this book).

The world-building was great and I really liked the realistic touches here and there that morphed this from a fantasy to dystopic novel for me. I wasn't expecting it and actually really enjoyed it. The pacing was also great.

Essentially, there was a lot of "great" things about this book and I'm sad that it will never be finished and if going by what the author wrote on the synopsis of book 3, we will never get a conclusion to this series because of low sales. Alas.

I'd recommend this one to those who love confident women who kick ass in a dystopic mystery novel. But be aware that this series will never be completed.

___

338. All the Sinners Bleed by S.A. Cosby--⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️.5

I finally picked this book up and honestly, I'm really glad I did. Even though it had moments that were really hard to read, it was eye-opening and powerful. Cosby truly didn't miss with this one.

ALL THE SINNERS BLEED explores racism and how it can take many different forms. These scenes were jarring, but so important. It goes to show that no matter where you are in the power hierarchy, you can still be the target for racist rhetoric. But this was also a heartbreaking look into how society, specifically North American society, treats missing Black children. The fact that no media coverage had spoken on the missing children in this book before that fatal shooting that starts the book is very telling and very reflective of today's society.

Some of the best parts of this book, beyond the obvious, were the moments where the MC was a total badass against the racists in the town. I think the irony of the Black main character being the sherif in this town isn't lost on the reader, but beyond the obvious of having this MC be a strict law-abiding citizen, he does not let the badge overshadow who he is at his core (no matter what others accuse him of).

The pacing of ALL THE SINNERS BLEED was great and kept the story flowing pretty well. And the side characters gave this book a lot of personality beyond being just a murder mystery--which, by the way, was incredibly compelling. Much like the MC, I really wanted them to catch the remaining killer. It kept me hooked until the end.

There was a love interest in this, but much like the MC, I think the reader will lose focus on her and just want answers regarding the murders. It's sad to say and it could be because of how Cosby wrote her with such disregard, or like a side note, but it was to the point where the book could have survived without her. I think the MC would have benefitted from having this character be more developed. But it definitely helped to show that he was very much a flawed character. But it's kind of sad that this female character with so much potential was so easily disregarded because of the male main character's fickle affection.

Shock-full of commentary on social justice issues that make this a very timely read, ALL THE SINNERS BLEED should be on most people's TBRs--I say most because there are some very triggering moments in this.

___

339. Phantom of the Auditorium by R.L. Stine--⭐️⭐️⭐️

I enjoyed PHANTOM OF THE AUDITORIUM for what it was.

I think this is one of those GOOSEBUMPS books where it can be a very entertaining October read because it had that spooky atmosphere of the school and the being that haunts the underground of the school. The whole concept of THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA is creepy to me, so it only makes sense that this one was kind of the same for me.

We had, yet again, more adults being jerks to kids and not listening to them. Sigh. I think narratives like this feed into the mistrust that kids have in adults and in the idea that if you talk to an adult, they won't believe you.

Anyway, I really enjoyed the ending and it finally pulled my attention fully to the story. This wasn't a favourite, but I was entertained.

___

340. Adam & Evie's Matchmaking Tour by Nora Nguyen--⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

First off, I know reading is subjective but I need to say that this book is better than the rating it currently has (it used to be worse than what it has now).

ADAM & EVIE'S MATCHMAKING TOUR had so much going for it--culture, adventure, romance, wit and banter, and characters who worked so well off each other. I really enjoyed the push and pull between them because they're also fighting familial expectations.

I also liked that author had the complexities that come those above-mentioned familial expectations, mainly reputation, how difficult it can be to navigate familial relationships, and how to follow your heart despite having that family be so heavily against what you want.

One of the best things about this book is that not only is the FMC is on her own journey of rediscovering herself while grieving, but the MMC is also on his own journey. These two characters were perfectly suited (despite others saying otherwise), because he was so set in his course and she was trying to find a way to break that life track she thought was meant for her. They are both helping each other in bettering themselves.

There was some spice, but it wasn't the made point of the story. I think it won't be spicy enough for most romance readers, but this book is so much more than the potential spice. For example, it has some pretty great side characters that give this book so much personality.

If it isn't obvious, I really enjoyed this one. I was hooked from the first chapter. And while this might not be a life-changing read, it was great for what it was. Plus, you get the chance to go on this gorgeous tour with the characters!

___

341. Graveyard Shift by M.L. Rio--⭐️⭐️

This is a novella, but it felt like a full novel. The pacing was not great. Man, it was an exhaustingly long read.

I think this was another case of me going into a book with high hopes. I loved Rio's IF WE WERE VILLAINS, so I was really hoping to get some of that writing in this one. And while the writing itself is actually very good, it was the pacing that killed me and where the story went.

The draw of this book was the promise of a creepy atmosphere (or at least, that's what the cover felt like for me), but the creepy set lasted for about a chapter. What followed after was a mystery that...kind of lacked reasoning. I get that need to solve the mystery of the sudden hole in the cemetery, but it felt like it went off the rails a bit. I would have loved more exploration of the night life surrounding this cemetery or the old abandoned church. THAT would have been cool.

I did like that we got to see from different perspectives--some a bit more relevant than others. Hannah was a particular favourite because of how unhinged she was. I could probably read a whole book from her POV. And seeing as how the author also comments on how she has a complicated relationship with sleep, it makes sense that this would be the most intriguing character because it is the one with the most personality in the whole novella.

GRAVEYARD SHIFT was one of those books that both felt like it belonged as part of a longer book, but also definitely shouldn't have felt as long as it did. Rio makes a comment in the introduction of the book about how she was approached by the publisher to write a novella, and while she mentions that this story has lived in her head for years, it kind of shows that this was an...approached story.

Anyway, that cover is stunning and creepy, but the story is not. Some will love this, because again, the writing itself is beautiful, but phew, that pacing and SO MUCH potential. It all tied up at the end, so at least we got that, but man, it had so many ways it could have gone.

___

342. The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates--⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

THE MESSAGE by Ta-Nehisi Coates was a great collection of essays that explored various topics that are all incredibly timely. One being about identity and how important it is to acknowledge and learn more about who you are. I liked this essay because of how it felt like Coates was truly learning more about himself and his heritage and we were lucky enough to hear about it.

Admittedly, I first picked this up because of that awful interview Coates had about Palestine and I wanted to see what he had written. I wanted to see why this Z was so hot and bothered about the section on Palestine. I wasn't disappointed. That section was incredible and I liked how he experienced Palestine with multiple guides. And his genuine fear during some moments were palpable. This section unfolded much like when a person first finally understands the truth.

THE MESSAGE was POWERFUL and had some great and insightful commentary on various issues plaguing society regarding racism, apartheid, and the internalized racism built on trauma.

This may have been a short read, but it packed quite the punch. I think this should be a must-read for a lot of people. Especially when Coates dives into his own difficult past with a learning disorder and how fraught the American education system is and how learning disorders are looked at by society. And also, how book banning not only has affected so many authors throughout the The States, including Coates himself.

While THE MESSAGE was sad in its truths, it still held a note of hopefulness.

___

343. The Rule Book by Sarah Adams--⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

THE RULE BOOK was such a fun little surprise. Adams wrote one of my favourite second chance romance tropes, which is that of young lovers who come back together and don't immediately fall back into love. That added bit of "enemies" to lovers made this even more enjoyable for me.

The banter between these two was so much fun and heated. I loved seeing the MMC slowly thaw out as the book progressed, but I also liked seeing the FMC gain confidence through their banter and his unfair treatment born out of long-held anger and heartache.

The MMC had to deal with his anxiety and confidence and it was refreshing to see an athlete acknowledge his insecurities (even if it IS a fictional character). But it was still nice to have that incite into his character, especially because we had that perspective. Truly, one of the reasons why I love dual perspective so much. But I also liked that despite his fears, he was genuinely good at his sport.

The FMC was a badass. Not only did she have to deal with the raging sexism in her work space and career, but she didn't let it ruin her goals. Her confidence was incredible and she would definitely be someone I'd like in my corner.

Finally, I loved the communication between the characters AND the surprising spice. It wasn't overly spicy, but it was spicier than book one.

If you like sports romances, second chances, and a sassy FMC that the MMC stands no chance against, then this might be one to add to your list! Also, to add, there are SOME allusions to the couple in book one, but I'd almost say that you can read this without having read book one.

___

344. A Shocker on Shock Street by R.L. Stine--⭐️⭐️⭐️

A SHOCKER ON SHOCK STREET had a pretty great ending and I enjoyed that.

This would have absolutely kept me up at night as a kid--both to keep reading it, and because of all the creepy crawlies that the characters faced. This was a fun and creepy adventure perfect for an October night of reading for a kid.

I will admit that some parts were a bit confusing, but i think that can be expected for a story that is so fast-paced and focused on getting to that ending. I think this is definitely one of those Goosebump books that would have benefitted from being just a bit longer.

I think that ending was on par with another one of Stine's books that I really liked and it saved the book for me. BUT the creepiness wise was definitely one of the better ones. It was a lot of jump scares and honestly, I wouldn't be surprised if people would actually love to go on the ride in this book.

___

Happy reading!

#Reviews of the Week#Book reviews#book review#my writing#my opinion#book list#books#booklr#bookish#features#bookworm#bookaholic#book blogger#book blog#bibliophile#long text post#on books#on reading#readers of tumblr

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

tuesday again 8/29/2023

my ENTIRE SUMMER has been either worrying about moving or actually moving. ALL OF IT. however an incredibly hot butch milf on the gay community bulletin board/dating app lex has finally answered my piteous call for gun safety classes with an invitation to her private range. unfortunately she is a landlord who owns a VERY large apartment complex. houston is a land of contrasts

listening

more joywave! one of my favorite bands bc they are best listened to in full album format, and i did a fuck of a lot of driving this weekend. little lies you’re told has an opening like a big machine warming up while you are in a control room way high up on a gantry somewhere. spotify

-

reading (2x bonus round)

All The Trimmings by Tesni Morgan (published 2001 in the UK) is a gift from @believerindaydreams. it is “erotic fiction written by women for women” (debatable) and “the publishers recommend that this book should be sold only to adults”. also, “Black Lace novels contain sexual fantasies. In real life, make sure you practise safe sex.” idk i’ve ever seen that kind of notation on an american novel before? fascinating precursor to the saccharine little “stay safe kids” ao3 authors notes

i do find the premise genuinely fun and compelling— two divorced milfs opening a hotel/bordello with historically themed rooms. i have had to look up a lot of british purple prose and i refuse to believe anyone says “rogering” in real life.

im being edged with glimmerings of bisexuality. every time one of the milfs gets turned on and goes out roaming to distract herself from being turned on, i go “oh?” like at a pokemon go egg, but so far all the dalliances and encounters have been dudes.

had a very strange experience with cormac mccarthy's blood meridian. i don’t normally interrogate whether or not i am the intended audience for a work except when it’s literally made for children, bc i as a modern bisexual woman am the intended audience for vanishingly few works. for example, many entire genres (westerns) are very challenging to enjoy.

a western has never made me go "wait so why DO i like westerns at all" so hard. like, what AM i doing here in this genre that is often deeply fucking uncomfortable to consume as a woman, and where the most foundational american and european works of the genre often uncritically embrace the worst parts of the american mythos in the most violent way possible? i do believe critics when they say mccarthy is not embracing violence for the sake of, and in fact has something to say with his revisionist western, but my god is it hard to wade through. anyway, dad media will not fuck me and i still have only a tenuous grasp on why i try so hard to glean enjoyment from it.

i know what mccarthy is trying to do and the overall tone of “weird old maybe-uncle” spinning a yarn to a big group of you and your cousins around a fire somewhere is pretty effective. unfortunately I have less tolerance for mccarthy’s style now than when I read The Road thirteen years ago in high school. i was immediately super invested in The Road’s single dad and how he and his kid were surviving, which does not need a lot of interiority.

blood meridian also has very little interiority. the first five chapters are a teen falling in and out of various fights. i was not, and am still not invested. if im reading A Man Goes On A Journey western (as opposed to A Stranger Comes to Town western) i would like to know two or three things about the man, especially if it seems to be angling at a bildungsroman. i don't typically care for third-person objective narration when it is this closely focused on one guy, and i really don't care for loving descriptions of maggots. comforting to know a lot of critics were also squicked out by this book. so it goes.

-

watching

finished watching s1 of spy x family! a Legally Not West German spy in Legally Not East Berlin has to go into deep cover and pose as a family man in order to gain access to Legally Not Erich Honecker, because the only social events Legally Not Erich Honecker goes to are the ones at his son's elite prep school.

this man FLINGS himself into being the absolute best husband and father possible. for the mission, of course.

i found the first few episodes the best, which is generally the opposite of my normal anime experience. i think it does a really good job of balancing high-octane spy hijinks and chases and explosions with very domestic concerns (he PROPOSES. with a THE RING OFF A HAND GRENADE. AFTER THROWING IT), and once you're really hooked on these characters it turns into a bit of a curtainfic. curtainanime? i had fun with all of it and anxiously await season two, but the actual applied spycraft does drop off significantly as the series goes on.

-

playing

we're going to continue with out of context genshin screencaps for the duration. the watery land of fontaine has a neat smorgsabord of visual style-- freshwater but also saltwater but also the aquarium section at petsmart.

-

making

unpacking mostly. acquired this coffee table and its mother. needs a very deep cleaning and some touchups but is intact. the individual tables are a bit large for like individual party drinks tables but all six together are QUITE large. four tigether would be a comfortable coffee table size for many apartments imo but! bc everything truly is bigger in Texas including my apartment it works for right now. for the first time in my life i am considering a sectional sofa bc the living/dining room is that dang big.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

As I’ve tried to show here, realism once was among the staunchest allies to the violence perpetrated globally by European colonial power. It’s hardly surprising then to see realism find its strongest legacy in American literature today. That said, my point here isn’t that realism doesn’t produce compelling storytelling. It couldn’t have served power for this long if it didn’t. My point is about the countless erasures enacted by the hegemonic forms of storytelling and its many gatekeepers. My point is about the soft violence of narrative, that in its vast potential to silence dissenting voices, upholds and fortifies imperial violence. This violence is nowhere as immediate and forceful as the mass slaughter of children, starving or bombing entire families off the face of Earth. Yet as a brown woman writer, I haven’t been able to look away from the subtler form of narrative violence that lasts for generations if not centuries, and at some point it stops needing the colonizer to do the work for empires. If narrative is inextricable from power, my point is about the ways in which narrative erases many of us and a few of the many ways in which we reclaim it.

In 2022 my debut novel, Border Less, was published in North America (7.13 Books) and South Asia (HarperCollins India), two spaces of diasporic life and aesthetic legacies that my fiction centers. When the novel was first released in the United States, I was nervous about its reception even if I was proud of the book I’d written. I was nervous mostly because when I transitioned from a world of literary criticism to a world of fiction writing, I learned how much narrative forms harden and tangle with the tastes of the market, especially in the United States, a key player within global anglophone literature. In an industry documented to be predominantly white at the highest levels of literary gatekeeping, I feared that my indie debut as a brown woman writer would mark the end of a dream that had barely begun to manifest.

To my relief, Border Less was received generously by its readers, who appreciated in general the novel’s play with form. In the United States, though, a couple of questions came up often in my conversations with literary gatekeepers, informed readers whose opinions hold power to shape the larger response to a book. Some asked me—explicitly or implicitly—to explain why my book should be called a novel if it employs fragmentation, discontinuity, and perspectives of multiple characters. Others—spoiler alert—asked me to explain why I chose to end my novel with a minor character’s meta-narrative perspective over the main character’s narrative one. What I heard in these recurrent questions was the assumption that a “real” novel is one that maintains continuity of narration and perspective, one that focuses on and pursues until the closing note the protagonist’s inner journey. What I heard here was the assumption that a real novel is the realist novel.

Before I continue I’d like to clarify my intent in sharing this observation. In emphasizing a partial and North American reaction to Border Less, my intention isn’t to condescend to critics or readers who didn’t get it. Neither am I here to dismiss the merits of realism as a narrative form. As an author I’m grateful to every reader who engaged with my debut in all ways they did. As a critic and educator I spent over a decade reading and teaching the realist novel, mainly those authored by Black and brown writers from across the world; it’s a narrative form I still love. Yet as I continued to explain my debut book as a novel to a North American literary community, I couldn’t help wondering: How did the novel, known to be the most versatile of narrative forms, congeal here into such a bordered form? In other words, how did the contemporary American novel become synonymous for so many with the modern realist novel? Who do these literary borders serve, and what’s at stake if we don’t ask these questions?

In his groundbreaking book Culture and Imperialism (Knopf, 1993), Palestinian American literary critic Edward Said chronicled the massive growth of the realist novel in recent Western history, especially in the three homes of unparalleled imperial power: England and France in the nineteenth century and the United States in the twentieth. Similar to social media’s capacity for the rapid, mass circulation of ideas today, the realist novel served then as a key tool of Western imperial propaganda, especially through the form’s emphasis on narrative principles that weren’t central to fiction from many other parts of the world, or even to precolonial Europe. Whether we consider the first English novel, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and its widely popular subset of imitations called Robinsonades, all featuring a protagonist who leaves the motherland to establish a colony elsewhere, or we consider Defoe’s successors—Joseph Conrad, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Jane Austen, and others—the realist novel encoded a web of references and attitudes toward non-Western peoples that bolstered Western imperial expansion.

Through close readings of excerpts from novels by Defoe, Conrad, Austen, Dickens, and other colonial writers, Said shows how realism focused on character development in stories of survival and self-determination and served a predominantly bourgeois readership. In these books, “The novelistic hero and heroine exhibit the restlessness and energy characteristic of the enterprising bourgeoisie, and they are permitted adventures in which their experiences reveal to them the limits of what they can aspire to, where they can go, what they become.” To borrow from today’s workshop parlance on “craft”—and to echo John Gardner’s famous description of good fiction—the realist novel worked hard at building “a vivid and continuous dream in the reader’s mind” through a prioritization of craft elements like character development, causality with its notion of linear time, continuity of narration maintained through verisimilitude, commentary, setting, and description, especially of the imperial home-country, articulated through the secondary yet key presence of distant colonies.

Said, of course, isn’t the only writer to show us how much of a recent geo-historic construct realism and its narrative principles are, even if it was in his work that I first understood how much storytelling serves power. About two decades later, acclaimed Indian writer Amitav Ghosh published a nonfiction book on the relationship between Western humanistic thought and global environmental concerns, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (University of Chicago Press, 2016). In this book, Ghosh talks about the rise of the Anthropocene in Western arts, sciences, and contemporary culture in which the human being—rather than nonhumans, the landscape, or some other element—became a literary narrative’s main agent of force, the one in charge of shaping plot. Here, too, the centrality of character development or the pursuit of “individual moral adventure” that is most associated with “serious fiction” in the West and the Anthropocene’s upholding of human agency, gained ground with the marriage of modernity, colonialism, capitalism, and monotheistic religions, especially Protestantism in which “Man began to dream of achieving his own self-deification by radically isolating himself before an arbitrary God.” Furthermore, The Great Derangement shows us how the realist novel upheld continuity of narration through the use of detail and description or “narrative fillers” (to echo literary theorist Franco Moretti) to establish verisimilitude or the principle of probability, once again with the goal of not disrupting the implied bourgeois reader’s pleasure.

In 2017, Chinese American writer Gish Jen’s book The Girl at the Baggage Claim: Explaining the East-West Culture Gap (Knopf) echoed Ghosh’s claim of the Anthropocene dominating the Western literary arts where the conception of self, in general, remains individualistic. Similar to Ghosh, Jen attributes the recent historic emphasis on individualism over the collective in Western storytelling to a string of historic developments that include “monotheism, Judeo-Christianity, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Reformation, and Romanticism, not to say the rise of market economy.”

Said’s, Ghosh’s, and Jen’s works name well—in their own ways—the historic context that allowed realism to dethrone other forms of storytelling, first in the West and increasingly around the world. Yet these works don’t link this history enough to a key space through which realism continues to maintain its legitimizing hold on anglophone literature in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries. What I’m talking about here is the role of the mainstream MFA program in the United States, the nation of the largest military and imperial power of our time. As I have written elsewhere, the MFA is an undeniable, hegemonic force on contemporary American letters, an empire of its own that often universalizes a provincial pedagogy of “good” storytelling. So much necessary ink has already been spilled by my peers here. Several contemporary writers, including Junot Díaz, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Claudia Rankine, Felicia Rose Chavez, Matthew Salesses, Beth Nguyen, David Mura, and Joy Castro, as well as my own essays elsewhere, have shown how much of what we understand to be the craft of good storytelling in the United States disseminates the historic context and cultural capital of a highly narrow demographic: upper- to middle-class, able-bodied, cis white men. Eric Bennett’s work here is particularly incisive in understanding the nexus between the production of American literature and American imperialism. For instance, Bennett published two essays in recent years in the Chronicle of Higher Education whose titles and bylines say it all: “How Iowa Flattened Literature: With CIA help, writers were enlisted to battle both Communism and eggheaded abstraction. The damage to writing lingers” (2014) and “How America Taught the World to Write Small: It exported a literature of individualism and domesticity—not one of solidarity and big ideas” (2020). These essays situate the origins of creative writing programs in the U.S. in the mid-twentieth-century American fear of Communism and the MFA’s economic foundations in the CIA, the State Department, and patronage by conservative American businessmen. “The discipline of creative writing was effectively born in the 1950s. Imperial prosperity gave rise to it, postwar anxieties shaped it,” Bennett affirms, referring to the explosion of MFA programs across the U.S. whose pioneering figures like Paul Engle at Iowa and Wallace Stegner at Stanford “shared a common vision for American culture with the internationalists of the Truman and Eisenhower administrations and influential philanthropic foundations.” Bennett writes about how the mainstream MFA program fostered a highly bordered kind of writing, one that upheld “the putative civic sufficiency of unapologetic selfhood” as key not only to good, literary storytelling, but also to the American identity defined in opposition to a Communist one.

In 2014, Brian Merchant, technology columnist for the Los Angeles Times, echoed Bennett on the MFA and the CIA in a piece for Vice in which he equated postwar American literature produced by “the MFA factory” to a “content farm” that perpetuated a specific ideology and aesthetic of writing. This specific aesthetic, often taught as a universal one, valorized the concrete over the abstract; showing over telling; the role of emotions and imagination over critical thinking; domesticity and nationalism over transnationalism; the right grammar, syntax, and sentence craft over one’s relationship to a lived historic moment and the world. For Bennett, Merchant, and many of my American peers of color, this aesthetic both proceeds and follows the birth of the MFA in an anticommunist paranoia; it finds its most enduring legacy in names like F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Paul Engle, Frank Conroy, Wallace Stegner, Ernest Hemingway, John Cheever, Raymond Carver, and periodicals like the O. Henry anthologies, the Paris Review, the New Yorker, the Best American Short Stories, and more.

As I write this essay, almost a century since the birth of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, whose graduates are most credited with the rise of the American MFA, the latter has produced several faculty members of color who, as I’ve noted earlier, practice and write about an alternative pedagogy of literary storytelling. Moreover, in spotlighting the traditional MFA program in the U.S., its dominant ideology and pedagogy of writing, my irritation isn’t with a practice of craft that pushes our students to choose concrete details over abstractions or engage with feelings over critical thinking or our visual faculties over aural ones while working with the page. The aforementioned approaches can produce effective explorations with writing for the novice writer, as well as finely crafted stories by any writer who takes them seriously. Neither is this essay about my exasperation with realism or its core narrative assumptions; I continue to love the form, even if I do read the realist novel through a different critical lens now. As a writer and an educator, I often rail against the pedestalization of narrative assumptions from a colonial era that continue to be upheld as timeless, universal truths within a field of U.S. “creative” writing that prides itself on celebrating innovation and, increasingly these days, diversity and decolonization. What baffles me is the centrality of realism as the—not a—respectable form of literary storytelling in the twenty-first-century U.S., whether it is through the mainstream writing workshop and its decontextualized pedagogy of craft, fiction, or reviews published by prestigious literary magazines, major deals for “literary” fiction by the Big Five, the adjudication of prestigious awards, and more.

Moreover, it raises the questions, however rhetorical: Can “minority” writers break the aesthetic and ideological walls drawn by imperial institutions in the name of good storytelling and still be celebrated for their work? In an industry where diversity has become a profitable buzzword and phenomenon, a marginalized point of view in fiction may be very welcome, even rewarded with the highest honors, but what of marginalized points of view that tell their story through marginalized forms of storytelling? In other words, for the minority writer, is travel toward aesthetic innovation doomed to follow a fiercely bordered road? A path predetermined by the hegemonic notions of form?

A book that resonated deeply with me while I grappled with questions of narrative form and gatekeeping as an Asian American writer is Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning (One World, 2020), even if it centers a highly bordered notion of Asian America. I read Minor Feelings in 2020 while I was finishing drafting my novel, Border Less, which was due for publication at the time. In her collection of essays that digress unapologetically, Hong reminds her readers how much the white gatekeepers of American literary fiction love coming-of-age stories by nonwhite writers, delivered on the page through “the MFA orthodoxy of ‘show don’t tell.’” The latter is a narrative move in which readers are invited to view a character’s journey without authorial intervention, a narrative move perfected by realism, I add. In returning often to her journey with artistic expression that would feel true to herself, Hong confesses that she abandoned her novel-in-progress about the 1992 L.A. riots and the complexity of American race relations, mostly because she couldn’t write a book that would suit the U.S. fiction market’s narrative taste. This market’s “ethnic literary project,” Hong reminds us, craves and rewards narratives of becoming by BIPOC, those that highlight stories of “survival and self-determination,” recalling in many ways Said’s “enterprising bourgeois” protagonist in colonial, realist fiction. Furthermore, the U.S. market’s love of realist fiction—with its narrative preferences for continuity, linearity, third-person narration, and show-don’t-tell—serves its implied white readers as it allows them to consume stories of pain by people of color without having to confront a white history of colonial violence and its global aftermath.

As much as I loved reading and teaching Hong’s journey as an Asian American writer, I haven’t stopped wondering: How many “minority” writers routinely abandon their novels because the forms available to or legitimized for them do not suit the stories they are trying to tell? In my community of aspiring and published authors, I know too many. And I ask myself, often in vain: Whose voice speaks loudest in their heads when aspiring novelists convince themselves that their manuscript is best laid to rest?

In 2004 in Mumbai, I started working every night on my debut novel, even if I didn’t know then that my jottings would eventually become a book. I had returned to my hometown after taking a year of leave from my graduate program in the United States, where I was training to become a literary critic, the closest I thought people like me could get to becoming a fiction writer. Even if I had always loved the world of art, language, and storytelling and had a strong legacy of these within my community, even if I had won a doctoral fellowship from an elite literature program, I wondered while scribbling in my notebook if the world of art, language, and storytelling was a path for me. From the time I mastered reciting Wordsworth’s “[I wandered lonely as a Cloud]” or excerpts from Shakespeare’s Hamlet in my middle school in Mumbai to the years I wrote the earliest drafts of Border Less, the stories I grew up imbibing from my community felt a galaxy away from the stories I was taught to appreciate as Literature. When I say Literature with an uppercase L, I refer to a body of writing that is legitimized by the Western establishment or imperial powers as the “literary” or “fine” arts. At the end of my sabbatical in Mumbai, I returned to the United States, finished my education, and started teaching, the only way I knew to financially sustain myself while nurturing writerly dreams. On the long, winding road to becoming an author, things about which I often write elsewhere, I was fortunate to encounter the right mentors, “minority” women across the racial spectrum who taught me an alternative relationship to literature and storytelling. After a colonial education in English that pushed me away from Literature in my earlier years of schooling, I discovered later in life storytelling by Black and brown writers from across the world who resisted erasure and reclaimed power through colonial languages in Literature: Arundhati Roy, Aimé Césaire, Édouard Glissant, Bharati Mukherjee, Ananda Devi, Toni Morrison, Maryse Condé, Gloria Anzaldúa, and many more.