#because “frontispiece” is only in the front

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

it's good but sometimes also cryingly frustrating when you can't even word enough to word the words

I am a(n):

⚪ Male

⚪ Female

🔘 Writer

Looking for

⚪ Boyfriend

⚪ Girlfriend

🔘 An incredibly specific word that I can’t remember

#the page in an anthology between authors#like a title page#but it's not about the stories#it's the book just reminding you it's an anthology#I've gone with “story break”#because “frontispiece” is only in the front#“interleaf” would be blank#“flyleaf” is at the front or back but also blank#I was tempted by “illuminate” but that's wrong for so many reasons

411K notes

·

View notes

Text

“So that’s [“Wild Pear Tree”] the first poem in the book after the frontispiece poem, and it really is sort of a poem for my cat, which is a silly thing to say, but it isn’t. My cat was my only companion for a long time, and he is in my current life the person who has really sort of known all of the “me”s that I’ve been. I got him when he was—his name is Filfy, f-i-l-f-y—and I got him when he was four weeks old. His mother had rejected him. He was the runt of his litter. He was flea bitten, and, you know, you could literally, like, if you pinched his fur you would come up with a pinch of fleas. And he had ringworm and roundworm and a respiratory infection and ear mites, and his eyes were swollen shut. I thought he was blind, but it was just he had so many fleas. And we just sort of nursed each other to health; we were kittens together. There were—I mean, not to get too “war story-y,” but there were lots of mornings or nights when he would be the one who came and sort of pawed at my face, and I would sort of wake up and realize that I hadn’t been breathing. This is, like, a real thing that happened, and he was the only one in the house. There was also another instance where I left the front door open one night—I mean, it was cold, because I couldn’t be responsible for anything—and lots of cats if you leave the front door open will sort of dart off never to be seen again. When I woke up the next morning, Filfy was in the doorway, and all these neighborhood cats were on the sort of, like, front area trying to come in, and Filfy was just there guarding the doorway, so we were really in it. I’m getting goosebumps talking about that. We were really in it together, and yeah, I mean, that poem I think is for him.”

— Kaveh Akbar, in an interview

#WE WERE KITTENS TOGETHER !!!!!#that is one of my favourite interviews ever I cannot believe I never shared it on here#w#interview#kaveh akbar

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

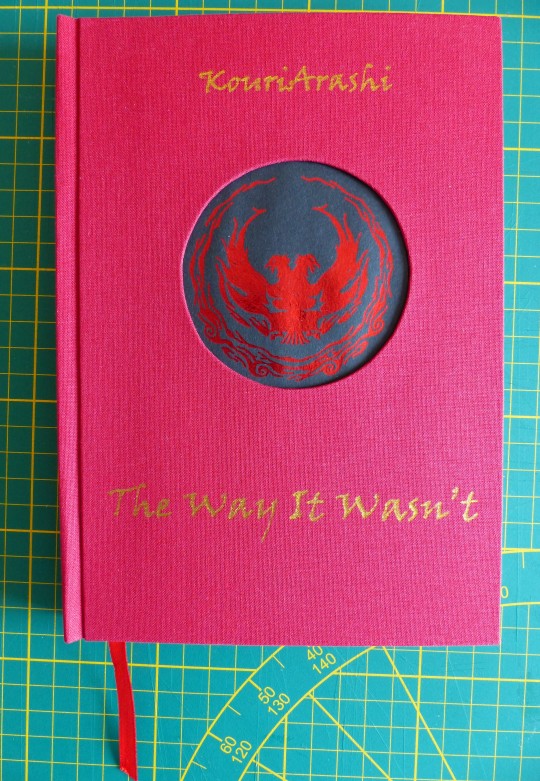

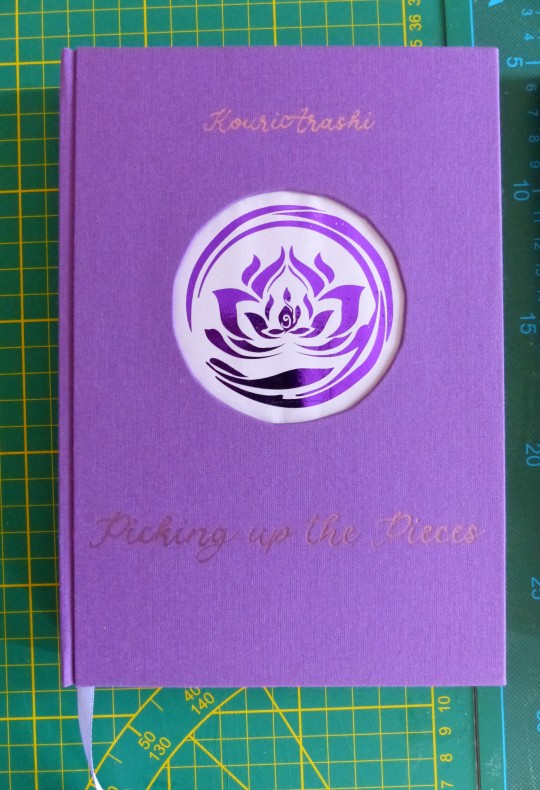

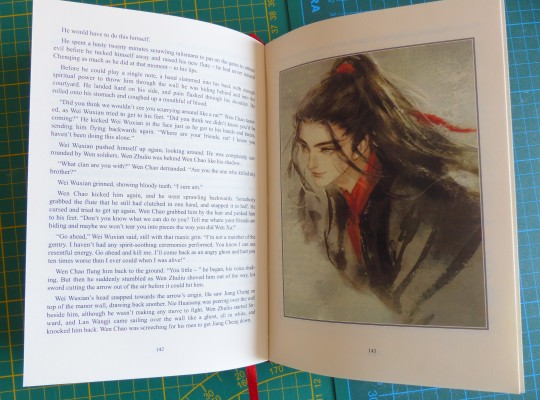

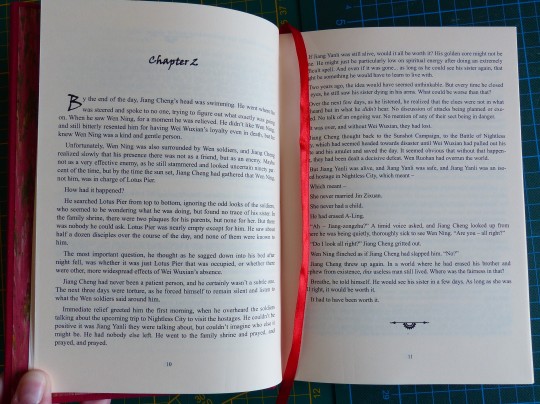

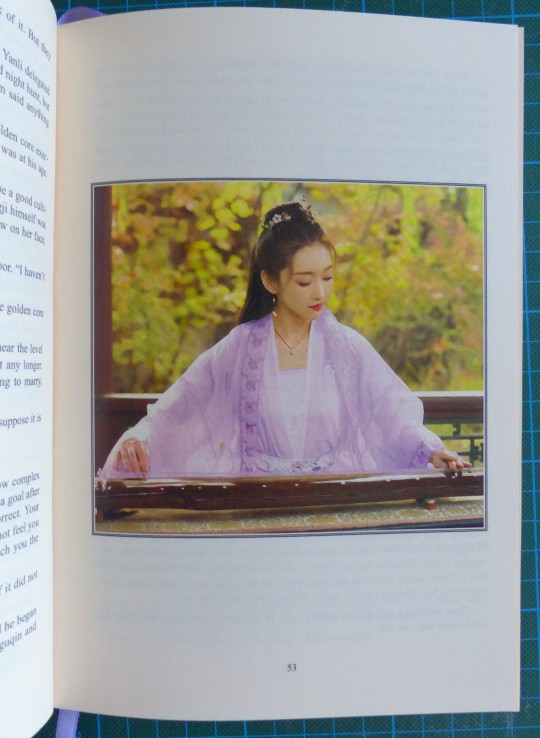

New Fanbinding! Two fics by KouriArashi

Now that the gift copies for @gingersnapwolves have arrived (and how quick the post was this time, I'm in awe!), I can post about my latest fanbinding project.

I had decided on binding both fics about, uhm, two years ago? XD I love all of Kouri's CQL fics; she's actually the reason I started watching the show in the first place, so it was a no-brainer to bind some of her fics!

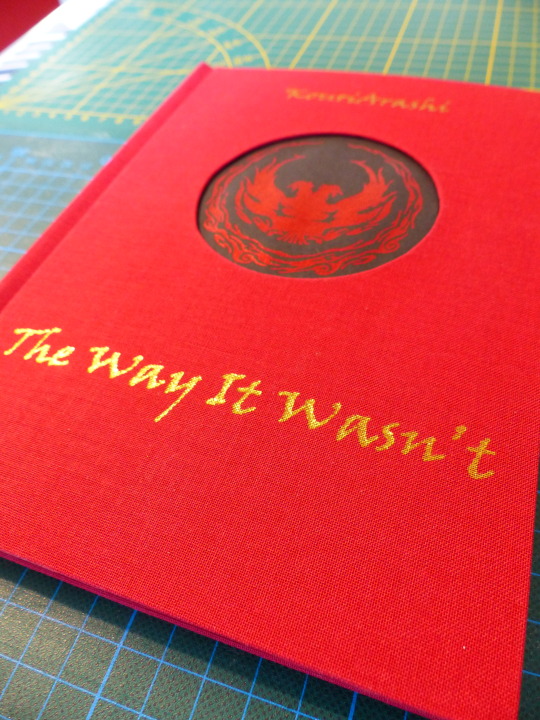

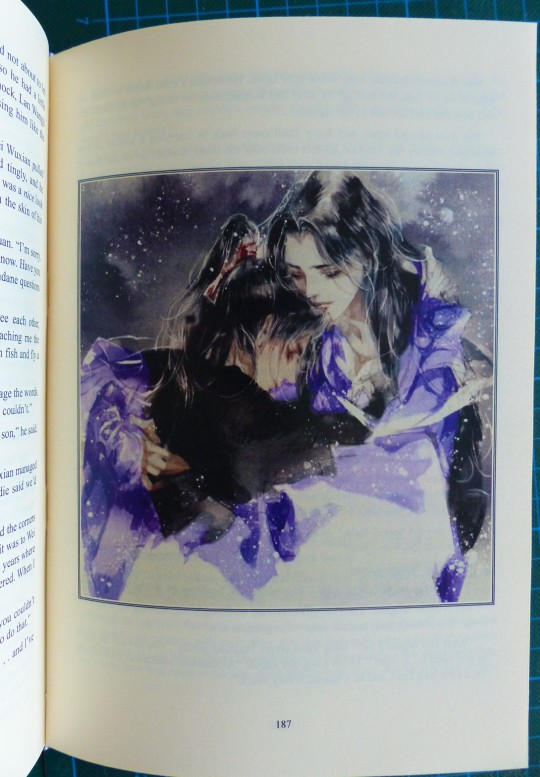

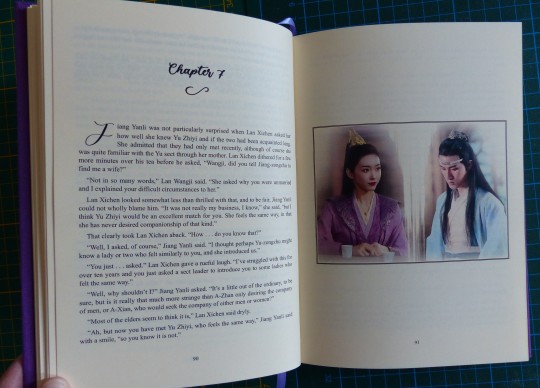

I think I did the typset for "The Way It Wasn't" in 2021 but I had a specific design idea for the case in mind and didn't feel confident to tackle that just yet, so the printed version sat around for... a while. Sometime after that, I did the typeset for "Picking Up the Pieces", which took longer because of the photo edits.

I finally got around to actually making the books in May and I'm very pleased with the results, though there were a lot of stumbling blocks in both projects and I'm actually surprised that the finished books look good. XD I was sure I'd case in the block upside down after all the other mishaps, but at least I didn't do that. XD (I might have checked each book like five times, though... just in case. XD)

More pictures and info about the process behind the cut.

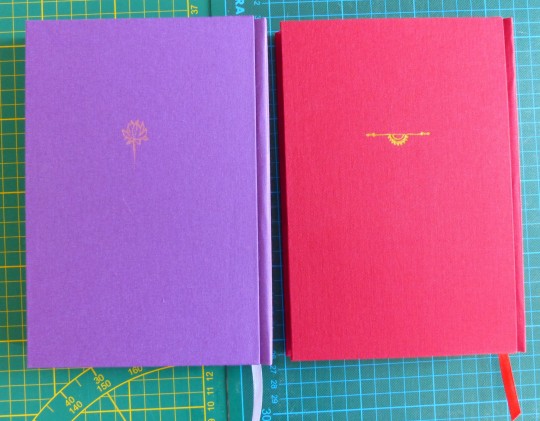

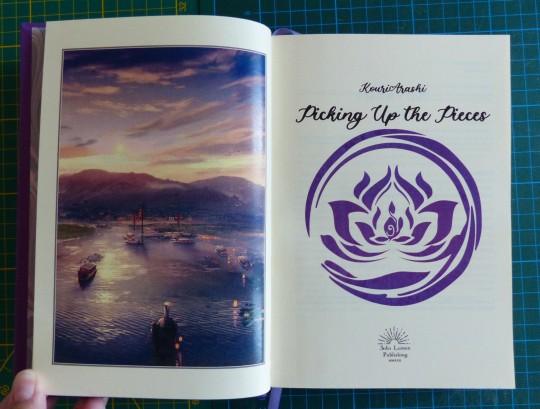

The books are supposed to be the first in a series of 5, each focussing on one of the great sects, and so I decided to use the same basic design ideas: colour-coded for the sect, the cut-out on the front, the little graphic on the back, same brand of Parisian marbled paper, frontispiece depicting the location, sect logo as title page, same design for titling on the spine.

For some reason, my camera refuses to really catch the foil colour from "Picking Up the Pieces" on the titling - it's a light pink/ rosé coloured foil.

The planned design for that book really caused me quite some grief, because it turned out that the foil I'd wanted to use (a light lilac one) did not work on this kind of book cloth. It's only for using a laminator / hot iron and so also doesn't work on paper with a foil pen.

I changed the colours for that books so often, going to a coated lilac cloth (where the foil works because it's coated...) but that didn't look good with the light coloured paper I used with the logo (no contrast), so I went back to this cloth and went looking for another foil. I tried rosegold which was okay, but then I lucked out and got the light pink one at a local shop.

For "The Way It Wasn't", I used a lot of official art:

For "Picking Up th Pieces", I used a mix of (edited) official art and photo edits I made myself. The "problem" of this fic is that Lan Wangji starts living at Lotus Pier, wearing Jiang colours most of the time and no forehead ribbon.

Also, Jiang Yanli is now sect leader and needed some fancy clothes. Luckily, Xuan Lu has acted in a lot of dramas recently where she wore some more dramatic robes that would fit a sect leader. I had to do colour edits of the robes at times and at one point had to photoshop Lan Wangji into a picture with her. My old Photoshop did not like all of this but I managed in the end. XD

I'm pleased with the results and might make a post with the photo edits at one point.

I also asked Kouri about her fancast for the OC Yu Zhiyi; that was a while ago. I wanted to include a picture of the character but didn't want to choose someone at random if Kouri already had someone in mind. Of course, I never mentioned that this was for the book; it was supposed to be a surprise after all! ;D

I'm really pleased with how the books turned out, especially considering all the stuff that went wrong in making the cases... XD I guess I can say I learned some things? XD

It's always fun if you mess up something on one case and think, "Ah well, this will be my copy then, I guess!" and then you mess up even worse on the other case! XD So Kouri got the book with more air bubbles in the logo because on the other case, the title was crooked. Argh!

I added some ornaments to distract a bit from that. It's also important to know that I'm a bit OCD about titles and stuff being crooked, I just hate it. This was a very sad moment for me.

But that's always the danger when fumbling around with that flimsy foil and the print-out. I'll live! :D

Materials used:

Printed on Clairefontaine Papago 80g (TWIW) and Clairefontaine DCP 100g (PUTP)

Case + endpapers "The Way It Wasn't":

- booklinen Brillianta - French marbled paper 120g - craft paper - hot foil (on brand)

Case + endpapers "Picking Up the Pieces":

- booklinen Imperial - French marbled paper 120g - Rössler letter paper 100g - hot foil (cheap stuff)

#fanbinding#bookbinding#my fanbinding#the untamed#mdzs#wangxian#mo dao zu shi#chen qing ling#arts and crafts#jiang cheng#jiang yanli#yunmeng siblings#wei wuxian#lan wangji#books#my posts

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In the name of love, sincerity, and knowledge, and with a clear conscience, I have dealt with the most profound and delicate problems. I challenge and have little regard for laws, customs, and conventions. Because I reject that which is false, that which is not the fruit of love. And if laws, customs, uses, and conventions serve hatred and falseness, I shall want nothing to do with them.”

- Aldo Mieli, preface to Il libro dell’amore, 1916

(Drawing of Aldo Mieli, a man with short, swept-back hair and a dark, trimmed mustache. He wears round-framed glasses and is smiling slightly.)

Aldo Mieli was a Jewish Italian gay man, socialist, internationalist and pacifist, a pioneer of early gay rights, and one of the founders of the history of science. Born in 1879, he founded the journal La Rassegna di studi sessuali in 1921, through his publishing house (Leonardo da Vinci, or L.D.C): opening the door to contributions and debates encompassing the perspectives of Catholic moralists, laymen, psychologists, endocrinologists, sexologists, creatives and scientists on a range of topics related to sexuality and gender. Mieli, along with a mysterious collaborator known only as Proteus, contributed extensively on the topic of homosexuality.

(Frontispiece of the first issue of La Rassegna di studi sessuali)

La Ressegna embraced the contribution of German sexologists, and in fact Mieli became a close friend of Magnus Hirschfeld. Frustrated by Italy’s more tentative approach to the emerging status of what we would now call gay rights, Mieli advanced the work on sexuality and gender being done at the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft in Berlin. The example that Germany provided led Mieli to organise the second World Congress of the League for Sexual Reform, originally slated to be held in Rome in June, 1922 (the location was later switched to Germany for economic reasons).

Mieli moved to France in 1928, however in 1939- unable to return to fascist Italy, and at risk from the advancing Nazi front in France- Mieli fled Europe for Buenos Aires, where he took up a teaching position and worked to found and direct South America’s first institute for science and history. Towards the end of his life, he poignantly wrote:

“In Italy, Fascism has destroyed all movements for redemption by introducing a true reign of hate. However, there is no doubt that I have been able to awaken a sense of human solidarity in some souls. For years I have fought, written, and taken action in support of a better comprehension of sexual life in an effort to overcome strongly rooted false ideas and proclaim a kingdom of physical and spiritual love. I am sure I have obtained some results and convinced some dubious souls. However, it appeared as though all my efforts had ended in failure when another morality based on power, imposition, and superstition began to dominate and reduce populations to slavery.”

Source: The Enemy of the New Man: Homosexuality in Fascist Italy, Lorenzo Benadusi, trans. Suzanne Dingee and Jennifer Pudney

#history of sexuality#gay history#msm history#lgbt+ history#queer history#italian history#20th century#socialist history#jewish history#fascism

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

What exactly was Jack thinking when he up and disappeared? I know that his “relationship” with Piki at the time wasn’t the most healthiest, but did he even leave a note? Or only have Pitchiner know about it as a contingency plan to prevent suicide on Piki’s part? I say Pitchiner because Piki would read his twin like an open book. I just wanna know what exactly was going through his mind while he made that decision, and what pushed him to finally make it?

Every single writer or fanartist for Nightmare Dork University has their own headcanons about the boys and their inter-relationships…. That is one of the things that has delighted me over time, ever since I found this RotGoC subfandom in 2015. I love everyone’s takes and all the permutations of story that happen.

Most of the creators involved in NDU agree that Jack and Piki *had* to split up to become stronger individually, and most of them have the two reuniting in the future.

I have constructed my Footlights & Frontispieces AU by basing it on the building blocks of NDU Stagefright stories written by @emeraldembers , @bowlingforgerbils and @neyiea, and then fleshing it out largely with my own experiences. [For the record, I was a “Jack” fleeing headlong from one “Piki”, running slambang into a second one, but the second one, thank all the powers that be, had a bit more capability for learning and changing than the first one did, which is *why* I can write happy middles and endings for my Jack/Piki tales. I can write both the good and bad headspaces.]

So to answer your questions about *my* take on the Stagefright split, in segments…

1] What was Jack thinking when he up and disappeared? He wasn’t thinking coldly enough and clinically enough to have solid thoughts other than his own survival. Oh, Piki wasn’t beating Jack physically, or literally holding Jack captive, but Jack was being smothered, losing his individuality. Jack was being asked, overtly or not, by Piki to give up people, things and activities meaningful to Jack, so that they could spend all their time together doing things meaningful to Piki, and Piki being oblivious to his own manipulativeness. When one is in a relationship like that, and one wants to change that and get out, one doesn’t really think…. One sees an opportunity to escape, and one takes that opportunity to save one’s own life.

2] Did Jack even leave a note? In my take on things, yes, Jack did leave a note. Nothing terribly long or elaborate… just “I have to go. I’m sorry,” left on the hallway table in their apartment, next to the front door.

3] Informing Pitchiner as a contingency plan against Piki committing suicide? No, that isn’t what happened in my version, for several multi-layered reasons.

3a] First off, in the way I see things, Jack wouldn’t confide in Pitchiner because, for all the nicest reasons, Pitchiner would try to talk Jack out of leaving town, and Jack knows on a gut level that he HAS to leave town, not just leave Piki. Jack is fairly sure that Pitchiner’s and Pitch’s apartment is the first place Piki would look.

3b] Regarding Jack considering the possibility of Piki’s committing suicide… as horriblly callous as this is going to sound, by the point that Jack is ready to jump ship and leave Piki, Jack is so far gone in his own head that he can’t AFFORD to think of that possibility, so he just locks it away in his subconscious. Again, overtly or covertly, for years Piki has been giving Jack the message, “I would just wither up and die if you leave me”. It gets to the point in Jack’s head that *Jack* will just wither up and die if he *stays* with Piki. So the “committing suicide” bargaining chip has no more weight with Jack.

4] You are absolutely dead-on correct that Piki and Pitch, despite their own estrangement, can read one another like the proverbial open book, so yes, Jack would certainly *not* confide in Pitch that he was leaving.

5] Thus, in my scenario, when Jack is offered the opportunity to not only leave Piki, but to leave town, that opportunity comes as assistance from someone with only the most tenuous of ties to our NDU & EBU boys, and Jack’s decision to flee is a split-second one, with no meticulous planning behind it. He just grabs that opportunity and goes, albeit taking the time to leave the above-mentioned terse note.

I hope that answers your question, dear! I’ll be expanding on this in the story “Sweater Weather”, which is in progress over on Archive Of Our Own.

https://archiveofourown.org/series/1253675

#ndu headcanons#ndu stagefright#askapaleexperiment#footlights and frontispieces au#nightmare dork university#fic: sweater weather#my boys WILL get a happy ending#i so decree

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lilac

Just a little while longer, just a little further up-- and there is a beautiful, solemn place: apart from coin, apart from the endless war, apart from any sovereign other than the divine.

(OOC: Here, have some accompanying music!)

The air seems impossibly thin, upon this remote mountainside-- but it only serves to make one’s lungs all the more strong. Flora breathes in deeply as she hoists herself over a steep ledge-- As much as she has numbed herself to her old fear of heights, it remains a relief to rest on solid ground again.

She stays there for a long while, resting on her back and staring up at the endless grey skies. There’s a faint crackle of levin in a faraway cloud-- but that hardly ever means much other than a spring shower, in these parts, so she doesn’t think about where to find shelter, or anything like this.

Her mind is swimming with questions that seem stupid, today. Stupid, but necessary-- “It is known that the first Fist attained the Destroyer’s sublimity at Schism, yes,” she starts again, pressing her dry, tired eyes shut, “but accounts and scriptures vary so much on the details. Was it he himself who announced to his followers that he had attained it? On his deathbed, he was said to have said this unto the man who cared for him. How-- how must he have felt? Was this what killed him? Had he known so much of the Destroyer that he-- became at peace with the death Rhalgr gave him? The mirage-- His mirage-- was it shattered in this way?”

Her brows knit for a moment, and she sits up, rubbing at her eye with a bandaged fist. As she told Martin, this faith was one of endless questions. She had envy for the Ishgardians, their Enchridion, their high Halonic masses at their cathedrals: One text, one orthodox faith-- well, mayhap it was all changing now, but the precedent, yes-- that solid, concrete precedent set was something to be envious of. “I wonder what they think of all of this-- My god of paradoxes, my faith of endless questions.”

She stands and looks down at the wasteland that stretches on and on-- Ala Ghiri is just a pretty blue stitch of embroidery on the horizon, from here, hidden behind a crest of red mountains. A little merchant caravan struggles by, on the road below-- Ul'dahn, no doubt, by the dead, languid, altitude-sick gait of the poor birds drawing the carriages.

She feels close to the world of men, still, when she sees this-- and she frowns. Just a little while longer, just a little further up-- and there is a beautiful, solemn place: apart from coin, apart from the endless war, apart from any sovereign other than the divine.

She travels and travels for bells, up a steep, rocky little trail that cuts into a little canyon. The further up she goes, little bits of fresh green vegetation sprout up from between the stones. “True knowledge of His sublimity comes to those who have spent their lives striving to know Him, but-- Ah, centuries ago, when our faith was so much more alive, I wonder--”

A pang of loneliness hits as she takes in the utter silence of this mountain path. Nothing at all like being packed into St. Reymanaud’s Cathedral, shoulder to shoulder with followers of Halone-- the hymns, the bells, the priest’s exaltations. With few notable exceptions, her days as an ascetic had been lonesome, and left her thirsty for discussion of the questions that kept appearing in her mind. “I wonder if it was easier, then, in those days-- to know Him truly. To-- to be among so many others, searching for the same closeness to Rhalgr as I am, who have taken that same vow.”

Flora briefly daydreams of what Sali Monastery must have been like in its prime, before it had become the ruin she called her home. Images flit through her head of the wizened old monks holding forums, discussing His nature-- and, finally, imparting this wisdom on the children the order had honored, by taking them as their own. It must have been such an idyllic world, there, in those days.

With some warmth, too, she thinks on Berrod, Autgar, N’hara-- And to some extent, Martin, too, was fast becoming part of this peculiar brotherhood of monks. “The Reformed Fist-- I’ve such high hopes. I owe them so much. I’ve my own role to play, among them. That much is certain.”

Autgar likened her to a priest, and often-- And more and more, each day, she had begun to see it, too. Mayhap she would not lead armies, or be a protector of the motherland. Mayhap she would never be a figurehead that the world of men respected, in any sense, because the world of men respects power and not much else-- And power could never entice her more than knowledge.

“And folk like me-- we have a place in the new Fists too, yes? Rhalgr did call me to be this way-- did he not?” She hardly ever smiles, but it’s thoughts like this-- yes, that will do it.

She finally comes upon a clearing-- the place she was looking for. The place carpeted in greenery, where the highland lilacs and the Rhalgr’s Gold bloomed with abandon. What stood in the center of this field was something strange, however: A small, wooden statue of the Destroyer. It seemed wrought not by the hand of a commissioned artisan, like so many other monuments close to the cities-- but by common, clumsy, naive hands like her own. She found offerings here, often-- offerings she had not left, herself. This was a holy place she shared with someone else, certainly, but she was unsure just how many others.

She had, in moons past, taken it upon herself to place something here of her own construction-- A plank of wood driven into the ground, with the following words carved in: “The land He strikes does not become barren.”

Whomever she shared this place with must have taken an interest to it. Every time Flora returned here, she’d find some manner of correspondence, always in the same shaky, meandering handwriting. Today was no exception-- at the base of the sign, sat a little bundle of papers, weighed down by a stone.

There’s a little scrap of folded paper on top that says “F. V.”

Flora’s heart skips a beat, when she sees it. “Ah!” She exclaims aloud, her voice echoing through the empty clearing. “Another letter-- and, ah-- it’s so much! What is all of this?” She gathers up the bundle, and unfolds the little note on top.

“I have transcribed this for you, from my own collection. Please tell me what you think. I look forward to your reply, as always.

V. M.”

“V.M., again!” Flora’s chest pounds. “How kind they are-- to always let me read such things! And this-- this is mine? Ah, what is it? Who--?”

Her excited, trembling hands thumb through the attached manuscript-- it appears to be an essay, of some sort, and a very dense one at that-- Written by a Brother Ewald, in the year 1328, the frontispiece says.

“It will take a few reads to make heads or tails of this, won’t it,” Flora admits to herself, plopping defeatedly onto the ground. V.M’s bizarre, frenetic handwriting doesn’t help matters at all.

But she settles herself in and starts to focus on the text, and it starts to make sense. The meaning of “one’s own mirage,” what it means to “best one’s own mirage--” The pieces of the Twelve hidden in all of their creations, obscured by the desires of man. Yes, yes, there’s a lot she agrees with, here, but-- “Ah, certainly ordinary men are driven by want, but this ought not mean ordinary men cannot be taught to seek His sublimity-- this is important! Our motherland was not so wounded in Brother Ewald’s time, certainly, but-- ah, this world of ours has seen much.”

Flora’s thoughts swirl and swirl until she realizes she’s come to the end of the essay. “O-Oh. Ah…” She gulps. “Mayhap I understood all of that, after all.” She has paper to write on, in her bag, and a pen her husband mistakenly left at Sali, last time he visited her there-- And V.M, it seems, does expect her thoughts.

She sets the paper out in front of her, and begins, in the finest handwriting she can muster:

“V.M.,

I am full glad, as always, to hear from you…” (tagging @berrodarmstrong, @dynamitecowboy, @nhara-tia, @friendly-fire-engaged because mentioned! THANKS FOR READING AAAA)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

W. Kirk MacNulty, 32°

The symbols used in 18th-century Masonic tracing boards are references to the vast body of literature and philosophy which documents Renaissance thought.

Art: Frontispiece from Stephen Jones, Masonic Miscellanies (London: Vernor & Hood, 1797)

Masonic Tracing Boards are training devices. In the earliest days of speculative Masonry, the Master would sketch designs on the floor of the Lodge using chalk. Then he would talk about the drawing during the meeting. During the course of the 18th century, the drawings were transferred to "Tracing Boards" which are pictures, one per Degree, that encapsulate the symbols of each of the Degrees. The Boards to which we will refer are English.

Speculative Masonry started in the 1600s, and its symbols are references to that vast body of literature and philosophy which documents Renaissance thought. In the Renaissance, the dominant metaphysic was Judeo-Christian monotheism with an admixture of Classical thinking. Renaissance philosophers incorporated many Greek (particularly neo-Platonic) and Jewish mystical ideas into their orthodox Christianity. Some of these influences came from the Hermetica which had, itself, been a substantial influence in the formation of early Christian doctrines. Others came from Kabbalah, the mystical tradition of Judaism. This fusion of classical and Jewish philosophy is called the "Hermetic/Kabbalistic Tradition"; and after it had been interpreted in the context of orthodox Christian doctrine, it became the basis of Renaissance thinking. Speculative Masonry dates from the end of the Renaissance (the mid-17th century), and it is no surprise that Masonic symbolism reflects this tradition.

The First Degree Tracing Board, which looks at first glance like a collection of heterogeneous objects, is, I think, a representation of the entire Universe. It is also a picture of a human being standing in a landscape. Neither of these images is immediately obvious, but I think the ideas will become clear.

The central idea of Renaissance thought was the unity of the Universe and the consequent omnipresence of the Deity. This idea is represented by the "Ornaments of the Lodge." The fact that Masonry has gathered these three objects into a single group suggests that we consider them together. The Ornaments of the Lodge are the Blazing Star or Glory, the Checkered Pavement, and the Indented, Tessellated Border; all refer to the Deity. The Blazing Star or Glory is found in the Heavens at the center of the picture. It is a straightforward heraldic representation of the Deity. Look at the Great Seal of the United States on a dollar bill, and you will see the Deity represented there in the same manner. The Checkered Pavement represents the Deity as perceived in ordinary life. The light and dark squares represent paired opposites, a mixture of mercy and justice, reward and punishment, passion and analysis, vengeance and loving kindness. They also represent the human experience of life, light and dark, good and evil, ease and difficulty. But that is only how it is perceived. The squares are not the symbol; the Pavement is the symbol. The light and dark squares fit together with exact nicety to form the Pavement, a single thing, a unity. The whole is surrounded by the Tessellated Border which binds it into a single symbol. The Border binds not simply the squares, but the entire picture, into a unity.

The idea of duality occurs throughout the Board: from the black and white squares at the bottom to the Sun and Moon at the top. In the central area of the Board, duality is represented by two of the three columns; but here the third column introduces a new idea. The striking thing about these columns is that each is from a different Order of Architecture. In Masonic symbolism, they are assigned names: Wisdom to the Ionic Column in the middle, Strength to the Doric Column on the left, and Beauty to the Corinthian Column on the right. How shall we interpret these Columns and their names?

One of the major components of Renaissance thought was Kabbalah. The principal diagram which is used by Kabbalists to communicate their ideas is the "Tree of Life." The column on the right is called the "Column of Mercy," the active column. That on the left is called the "Column of Severity," the passive column. The central column is called the "Column of Consciousness." It is the column of equilibrium with the role of keeping the other two in balance. The three columns all terminate in (depend on) Divinity at the top of the central column. Referring to the columns on the First Degree Tracing Board , note that the Corinthian Pillar of Beauty is on the right; in the classical world the Corinthian Order was used for buildings dedicated to vigorous, expansive activities. The Doric Pillar of Strength is on the left; the Doric Order was used for buildings housing activities in which discipline, restraint, and stability were important. The Ionic Pillar of Wisdom is in the middle. The Ionic Order is recognized as an intermediate between the other two and was used for Temples to the rulers of the gods who coordinated the activities of the pantheon. The Three Pillars, like the Tree of Life, speak of a universe in which expansive and constraining forces are held in balance by a coordinating agency.

The Universe of the Renaissance philosophers consisted of "four worlds." The Kabbalistic representation of this idea is shown in the figure above by the four large circles denoting four "worlds." They are the "elemental" or physical world, the "celestial" world of the psyche or soul, the "supercelestial" world or spirit, and the Divine world. These same levels are represented on the First Degree tracing board pictured on the front inside cover of this issue. The Pavement represents the "elemental," physical world; the central part of the Board, including the columns and most of the symbols, represents the "celestial" world of the psyche or soul; the Heavens represent the "supercelestial" world of the spirit; and the Glory represents Divinity.

These ideas describe the "landscape." Where is the man?

Another important Renaissance concept was that of a Macrocosm (the universe as a whole) and a corresponding Microcosm (the human individual). The idea is that the universe and human beings are structured using the same principles (both being made "in the image of God"). Consider the Ladder. It extends from the Scripture on the Altar to the Glory which represents the Deity; and in the Masonic symbolism, it is said to be Jacob’s Ladder. We consider the ladder together with another symbol, the Point-within-a-Circle-Bounded-by-Two-Parallel-Lines, which is shown on the face of the Altar.

These symbols are discussed together because in many early Masonic drawings they appear together as if they have some connection. (See the illustration from Masonic Miscellanies, 1797, at the head of this article.) Consider the Two Parallel Lines first. They, like the Doric and Corinthian columns, represent paired opposites, active and passive qualities. In Masonic symbolism, they are associated with the Saints John; the Baptist’s Day is mid-summer, the Evangelist’s is mid-winter.

Now, this Point-within-a-Circle-Bounded-by-Two-Parallel-Lines, together with the Ladder and its three levels, reveals a pattern very similar to the three columns. There are three verticals, two of which, the Lines, relate to active and passive functions while the third, the Ladder between them, reaches to the heavens and provides the means "by which we hope to arrive there." The ladder has "three principal rounds" or levels, represented by Faith, Hope and Charity, which correspond to the three lower levels of the four-level Universe we observed earlier.

Both the Macrocosmic "Landscape" and the Microcosmic "Man" share the fourth level of Divinity, represented by the Blazing Star, or Glory. Taken together the Ladder and the Point-within-a-Circle-Bounded-by-Two- Parallel-Lines represent the human individual made "in the image of God," according to the same principles on which the Universe is based.

A Mason is sometimes called "a traveling man." One of the Masonic catechisms gives us an insight into this term. "Q. - Did you ever Travel? A. - My forefathers did. Q. - Where did they travel? A. - Due East and West. Q. - What was the object of their travels? A. - They traveled East in search of instruction, and West to propagate the knowledge they had gained." Notice the cardinal points of the compass on the Border of this Tracing Board; they define the East–West direction in Masonic terms, and, in doing so, they describe the nature of the journey to which the new Mason apprentices himself. That journey from West to East is represented, symbolically, by the progress through the Masonic Degrees; and it is, in fact, the ascent up Jacob’s Ladder—one of the "Principal Rounds" for each Degree.

The notion of a "mystical ascent" was part and parcel of the Hermetic/Kabbalistic Tradition. It is a devotional exercise during which the individual rises through the worlds of the soul and the spirit and at last finds himself experiencing the presence of Deity. Some of these ascents are deeply Christian in their character. In De Occulta Philosophia, Agrippa "rises through the three worlds, the elemental world, the celestial world, the supercelestial world...where he is in contact with angels, where the Trinity is proved, ... the Hebrew names of God are listed, though the Name of Jesus is now the most powerful of all Names." (Frances A. Yates, The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, London, RKP, 1979, p.63)

The Second Degree Tracing Board shows a familiar pattern: two columns which have opposite characteristics, and between them a staircase, a form of ladder. We cannot investigate this symbol here because of space limitations (see Heredom, vol. 5, 1996, for a fuller explication), but we know we are to climb this staircase. The picture summarizes the Renaissance idea of the approach to Deity as an interior journey.

On the Third Degree Tracing Board, the grave probably does not refer to physical death. During the Renaissance there was much discussion about "the Fall of man" and its effect. "The Fall" seems to refer to some event by which human beings, who were at one time conscious of the Divine Presence, lost that consciousness. After "the Fall," ordinary human life, as we live it on a day-to-day basis, is "like death" when compared to human potential and to a life lived in the conscious awareness of Divine presence. The grave suggests such a "death" to be our present state. The acacia growing at the top of the grave suggests that there is a spark of life which can be encouraged to grow and refers to the possibility of regaining our original Divine connection.

The view of the Temple in the center of the Third Degree Board shows "King Solomon’s Porch," the entrance to the "Holy of Holies." The veil is drawn back a little offering a glimpse into that chamber where the Deity was said to reside. This suggests that at the end of the journey from West to East some process analogous to death enables the individual to experience the Divine presence. After this process has occurred, he lives once more at his full potential. Again, I think that this refers neither to a resurrection after physical death nor to a life after physical death; both of which are the domain of religion, not Masonry. Rather, it refers to a psychological/spiritual process which can occur, if it be God’s will, within any devout individual who seeks it earnestly and which I believe it to be the business of Freemasonry to encourage. After all, we claim to be Freemasons, and this is that Truth, the knowing of which "make[s] you free."

This article has been shortened by the author from the original published in Heredom, Vol. 5, 1996.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Complete Review of House of Leaves

The Remastered Full-Color Edition

House of Leaves

Mark Z. Danielewski

A Novel

What the fuck does “Remastered” mean? What the fuck does “Full-Color” mean?

Because as the copyright page tells us:

A Note On This Edition

Full Color

The word house in blue; minotaur and all struck passages in red.

The only struck line in Chapter XXI appears in purple. (Which btw, so does A Novel on the front cover. These are the ONLY 3 WORDS IN PURPLE. WHY? WHO THE FUCK KNOWS.)

Xxxxxxx and color plates. (REDACTED color plates. LOST color plates. Otherwise black, unfocused photography that may as well be printed in black and white, more incoherent collages, and incoherent models. See EXHIBITS and Appendices.)

2-Color

Either house appears in blue or struck passages and the word minotaur appear in red.

No Braille.

Color or black & white plates.

Black & White

Color is not used for the word house, minotaur, or struck passages.

No Braille.

Black & white plates.

Incomplete

No color.

No Braille.

Elements in the exhibits, appendices and index may be missing.

But what do we find in the Index?

house (black) . . . DNE

DNE - Does Not Exist. And, indeed, METICULOUSLY, EVERY time the word house is written, it IS in blue. Regardless of if it’s in the text, in the footnotes, in the reviews, in another language, as part of another word, on the cover, or in the fucking copyright. It Is Blue.

And the copyright page informs us this was copyrigthed in 2000, with no prior publication dates.

I refuse to fucking believe ANY other edition of this book exists, save the Incomplete edition which I DO believe exists because someone other than Mark Z. fucking Danielewski told me it does.

The cover is, intentionally, too small for the width of the book, with the frontispiece sticking out

Frontispiece of incoherent junk meant to set the mood for the entire fucking trip.

The dimensions of this book are patently unusual. It does not adhere to the standard book ratio; it is too wide for its height. Everything about this book is DESIGNED to fuck with you, to challenge every standard, to SCREAM “I Am Not What You Think I Am. I Am Not Normal.”

“A Novel”

*distant hysterical sobbing of someone ripping up their English degree*

And that’s. just. the fucking. cover.

Good luck.

#House of Leaves#this is intended to educate those who have not had the pleasure#Welcome to hell friends#What's real???#Is ANYTHING real???#If you ever want post-modernism defined I will just throw this book at you

467 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacopo Sannazaro’s The Piscatory Eclogues and Aldus Manutius

The Special Collections Department is featuring articles written by our student staff in conjunction with our current exhibit, The Compleat Angler: And Other Meditations on the Art and Philosophy of Fishing, 15th Century to the Present, which is currently located in Hillman Library, Third Floor, Room 363, Special Collections Department, University of Pittsburgh.

Fig. 1. Frontispiece portrait of Jacopo Sannazaro and Title Page. From: Sannazaro, Jacopo. 1570. Iacobi Sannazarii Opera Omnia. Latine Scripta. Venetiis: Ex Bibliotheca Aldina.

One of the earliest published pieces of literature on the topic of fishing is Jacopo Sannazaro’s work The Piscatory Eclogues. This text set the stage for many later books on fishing, such as Izaak Walton’s Compleat Angler, bringing the life of fishermen into the forefront of scholarly discussion. In writing the eclogues, Sannazaro transformed a traditional literary genre, the pastoral eclogue, into a new form that focused on fishermen living near bodies of water instead of the shepherds in the rural settings of the pastoral.

The pastoral eclogue is a type of literature that has been around since Theocritus’ Idylls, which was published before 250 B.C. Around that time, Virgil also wrote his own Eclogues in the same style. While the technique fell out of popularity after that, it resurfaced during the Italian Renaissance (“Aldus Manutius” 2016). The pastoral eclogue is unique from other literary genres in that it incorporates monologue, dialogue, narrative action, and more, all within the same composition. Additionally, it makes extensive use of allusion to convey meaning (Kennedy 1983). These qualities allow writers a freedom that cannot be found in other literary styles.

Fig. 2. Svedomsky, Pavel. 1892. Naples. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Available from: The Athenaeum

Because of these features, Sannazaro was drawn to the eclogue. It is clear that he was directly influenced by Virgil, as The Piscatory Eclogues are parallel in style and structure to Virgil’s (Hankins 2009). However, Sannazaro felt that fishing would make better subject matter than shepherding, and he changed the traditional aspects of the form to reflect that. Pastoral eclogues are typically set in a land called “Arcadia,” which is an idyllic wilderness setting, distantly influenced by Italian landscape. To make his narratives more relatable to contemporary Italian readers, Sannazaro chose to use real places as the background of his eclogues, setting The Piscatory Eclogues in actual towns along the shoreline of Naples, Italy (Hankins 2009). Another decision Sannazaro made was to publish the verses in Latin. Though he wrote other works in the vernacular Italian, he used Latin for his eclogues to create a bridge between classical literature and contemporary Italy (Kennedy 1983). These literary choices were successful in attracting readers, and when The Piscatory Eclogues were published in Naples in 1526, they were well received throughout all of Italy. They even made their way into other parts of Europe, becoming popular in countries like Germany and Portugal (Mustard 1914).

The University of Pittsburgh’s library system has several editions of this text, including English translations and versions published within the past century. The most important edition, which was published in 1570 by Aldus Manutius in Venice, can be found in Archives & Special Collections at Hillman Library. Our copy was donated by William M. Darlington, and he noted in an inscription in the front of the book that it is “One of the Earliest books on the Art of Angling Printed by Aldus.” While the age of the volume is noteworthy on its own, the fact that Aldus Manutius published it is even more significant.

Fig. 3. Portrait of Aldus Manutius. From: Grendler, Paul F. 1995. Books and Schools in the Italian Renaissance. Aldershot, Hampshire, Great Britain: Variorum.

Aldus Manutius, one of the most famous printers ever, worked in Italy during the Renaissance, printing books for Italian readers. He began his career as a Humanist teacher, focusing on Latin classics, though he was also familiar with ancient Greek texts. When he was forty, he decided that it was more important to live honestly rather than to endlessly search for truth. He formed a partnership with two wealthy Venetians and opened his own printing company, the Aldine Press. In choosing what to publish, he concentrated on appealing to Humanists. Humanists preferred to study ancient volumes in their original language and context without contemporary commentary added by translators. Because he spoke Greek, Manutius was able to publish texts from writers like Aristotle in their original language, a phenomenon that was previously unheard of. Manutius attained great success with this approach, and he continued to revolutionize the publishing industry with his versions of Latin classics. He printed them on smaller paper without additional comments. Additionally, he created the Aldine Italic and Roman type fonts. With these changes, he was able to produce small octavo-sized books that people could easily carry with them (Grendler 1995).

Fig. 4 and 5. New Aldine type fonts. From: Sannazaro, Jacopo. 1570. Iacobi Sannazarii Opera Omnia. Latine Scripta. Venetiis: Ex Bibliotheca Aldina.

All publishers of the time had their own characteristic devices that were printed in their books to establish their authority. Manutius created the Aldine Dolphin and Anchor Device, which features an anchor with a dolphin wrapped around it. The motto he chose for this device was “Festina lente,” which means “make haste slowly” (Englade). The image fits this motto well, as the dolphin is a fast animal, made slower by the anchor it holds onto. All of the works published by the Aldine Press contained this device. It can be seen on both the title page and the tail-piece device of the 1570 edition of Iacobi Sannazarii Opera Omnia. Latine Scripta, which includes The Piscatory Eclogues. Even after the dissolution of the Aldine Press, the device has remained connected to printing. Other famous publishers over time, including William Pickering in London and Doubleday in the United States, have appropriated the device to use in their own books.

Fig. 6. Aldine Dolphin and Anchor Device. From: Sannazaro, Jacopo. 1570. Iacobi Sannazarii Opera Omnia. Latine Scripta. Venetiis: Ex Bibliotheca Aldina.

Throughout Manutius’ career, he chose the books he published carefully, only printing what he thought would be profitable. In addition to Greek and Latin classics, he also published contemporary texts, both in Latin and Italian. The books he chose usually sold well, and he was able to turn the company over to his brother-in-law, son, and grandson before his death in 1515. They continued to operate successfully, but without Aldus’ charm, they eventually lost collaborators and closed the press in 1598 (Grendler 1995). Despite this, the Aldine Press continues to be seen as an important influence in the history of book printing. Manutius’ choices regarding language, book size, and font revolutionized the publishing world, paving the way for books to become more affordable and accessible to the general public.

The 1570 copy of The Piscatory Eclogues held in Archives & Special Collections is representative of a typical Aldine book. Though it was printed after Aldus’ death, it retains the characteristics that made him famous. For example, it is small in size and printed in Italic and Roman fonts. People who bought it would have been able to carry it around with them, enjoying Sannazaro’s fishing poems in the same Italy where they were set.

-Cassie Frank, graduate student employee

Works Cited

“Aldus Manutius.” 2016. Encyclopedia Brittanica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Aldus-Manutius.

Englade, Emilio. Accessed August 31, 2017. “Dolphin-and-Anchor device of Aldine Press, ca. 1500.” Harry Ransom Center: The University of Texas at Austin. http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/permanent/windows/southeast/aldine_press.html.

Grendler, Paul F. 1995. Books and Schools in the Italian Renaissance. Aldershot, Hampshire, Great Britain: Variorum.

Hankins, James, ed. 2009. Sannazaro: Latin Poetry. Translated by Michael C. J. Putnam. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Kennedy, William J. 1983. Jacopo Sannazaro and the Uses of Pastoral. Hanover and London: University Press of New England.

Mustard, Wilfred P., ed. 1914. The Piscatory Eclogues of Jacopo Sannazaro. Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press.

Sannazaro, Jacopo. 1570. Iacobi Sannazarii Opera Omnia. Latine Scripta. Venetiis: Ex Bibliotheca Aldina.

Svedomsky, Pavel. 1892. Naples. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Available from: The Athenaeum, http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/full.php?ID=217351# (accessed September 14, 2017).

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I finally got hold of a copy of Thick as Thieves

And may have reflexively clutched it to my chest in the bookstore like it was a long-lost friend, don’t look at me. Scattered reactions underneath the cut! (Scroll like hell if you’re on mobile; there’s major spoilers but there’s also a rambly-ass wall of text to conceal them.)

I think it’s interesting, structurally, that it’s been three frickin’ books since we actually got anything at all from Eugenides’s POV even though it is very much his series. It does at least reinforce my impression of The Queen of Attolia as the central book in the series and no, I’m not just saying that because it’s my favorite, shut up. But I do wonder if, since apparently the next book is going to be the last, if we’re going to end up with two triptychs: The Thief, The Queen of Attolia, and the unnamed last one as the main story, and The King of Attolia, A Conspiracy of Kings, and Thick as Thieves as the “spinoffs.” KoA is the least convincing as a spinoff, and the most Eugenides’ story out of the three, since it’s the story of how he took command of Attolia as much or more as it is the story of Costis gaining respect for him.

Sidebar: the way that I read these books was Exactly Wrong, because it was as follows: I read half of The Thief while entirely too young for it, forgot about it completely, received KoA several years later when it was the most recent in the series, and read through it with no more idea of what was going on than Costis. I wouldn’t recommend this - it was like never getting to read Queen of Attolia for the first time, just skipping ahead to the first reread - but it made for a really interesting experience of KoA, and I think probably an unusual one? And is probably why it took me until now to think “hey, Costis kind of stands in for all of Attolia in going from contemptuous of Gen to devoted!”

Anyway. Thick as Thieves is definitely a side-story, as is Conspiracy of Kings - I’d need to reread CoK to analyze it at all, but everything that’s relevant to the story of the Little Peninsula in ToT is in the last, oh, fifty pages? But both of them are, I think, the stories of how Eugenides affects other people. (And this is why I lumped KoA in with them earlier). In ToT it’s about Eugenides rearranging his life; in CoK it was about Eugenides inspiring Sophos to go from uselessly scholarly heir to king. They’re both about Gen’s impact, just as KoA is also about how Gen affects Costis. I really love the personal-vs-political pressures in this series, can you tell?

Speaking of personal-vs-political, I’ve seen a few intersections between this series’ fandom and that of the Vorkosigan books, which I have to stop myself from calling the Barrayar books on a regular basis. I think that pressure, personal and political playing off each other, probably draws people to both series. The end of the book, with Kamet getting fond of Attolia (and I do wish that that had more focus), made me want a particular kind of story – a story about how Attolia changes everyone who comes into her borders – and I think that also reminds me of the Barrayar books, because they also had that thread in them.

Anyway, back to the actual book I’m reacting to, here. I guessed that Costis was Costis very early on, but that wasn’t really meant to be a secret, and I liked that the moment when Kamet finally used his name still had impact even though we all knew by that point. I knew Kamet wasn’t going to be delivered and then thrown out, obviously – we know Gen’s not like that. And we know that the series twists on you and there’s always more going on than you think, so I at least was looking for the twist the whole time. I guessed what it was wrong, though; I thought for a very large chunk of the book that Costis knew Nahuseresh was dead and hadn’t realized Kamet didn’t know he knew. Eventually I started realizing that I was wrong; I didn’t really have a replacement theory. I did guess that Kamet was being abducted for reasons other than annoying Nahuseresh, and that it was for the things he knew, but I’m not sure how much that counts as guessing the twist, given that we know Gen. I guessed that Gen was the disobedient Attolian servant Kamet was friends with, though I’m still a little vague on the timeline there – before Gen got his hand cut off, I think? Or was it an offscreen bit in QoA? Either’s possible. I did not guess that Nahuseresh was still alive, so, MWT’s still got it.

I was definitely expecting Ennikar or Immakuk to show up, and I do think Ennikar did, that feverish Costis had the right of it. I doubt we’re supposed to know, though.

Whatever was going on with Gen’s youngest attendant at the end went right past me – young Erondites? What? I thought there were only two Erondites children, Dite and Sejanus; was there a sister who’s now Gen’s sweet-Polly-Oliver attendant? What? I need a reread, I guess.

Her Highness Gitta Kingsdaughter is making me tear my hair with frustration. Who introduces something like that on a frontispiece map? Who? Who does that? Googling brought up interviews, and apparently she’s trying very hard to have her own story and MWT is trying not to write it, and. Tearing of hair, gnashing of teeth, why aren’t the other books in front of me!

And finally – until tomorrow, anyway – Costis/Kamet. Oh my God. I was actually… not expecting, but faintly hoping, that it was on purpose? It didn’t seem to be, and, well, I didn’t expect it, but I wish it had been there. Not just because I ship it like burning, although that’s true, but because… this series and I go a long way back, and it would have meant a lot to me to have a queer love story in a series that has been so important to me for so long. (See also: Nico di Angelo, intense feelings about.) And I got my hopes up, just a little, never really thinking I had a chance, so it stung a little. On the other hand, I was genuinely afraid for a while that they were going to part ways forever, so the relief of realizing that Gen was sending them off into the sunset together was a balm to that particular self-inflicted hurt.

Fangirl hat taking over from queer girl hat (not that they’re not often comorbid hats) – for fuck’s sake. “My Attolian.” Tongue-in-cheek talking about who could ever possibly be so foolish as to get romantically entangled, followed by staring at the sky and waiting for the other one to speak. The constant push-and-pull of power between the two of them, of Costis trying not to hold power and Kamet pushing them back into master-and-slave roles because that’s how he knew how to interact with the world – that is a damned fascinating dynamic whether it’s romantic or not, but I’m a person with a sexual interest in complicated power dynamics and it had my attention. Kamet’s complete shutdown when he thought Costis was dead, and complete inability to abandon Costis to his illness. That fucking scene where Costis and his bulging muscles pull Kamet close by the replacement chain and tear the inks apart. I know what I want for Yuletide. (They also get a tag.)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Function of a Book: Readers and Collectors

Special Collections welcomed Will Rhodes’ ENGLIT1125 Masterpieces of Renaissance Literature on Wednesday, March 15th. Students had the opportunity to examine facsimiles of Renaissance literature and poetry; fine press and private press editions of literature and poetry; and historical texts dating back to the Renaissance. Students worked closely with these materials and completed an in-class assignment to create a short essay. Professor Rhodes selected a handful of these essays for us to feature on the Special Collections Tumblr. We hope that you enjoy!

What is the purpose of a book? Well, to be read of course! But is that always true? While the contents of a book may never change, even down to the style of font it is published in in various editions, the purpose of the book may change. Special Collections houses many facsimiles, or exact copies, and modern editions of older books. I will compare one facsimile and one Renaissance book in order to show how a book is transformed from an object with a practical function to an object meant to be collected.

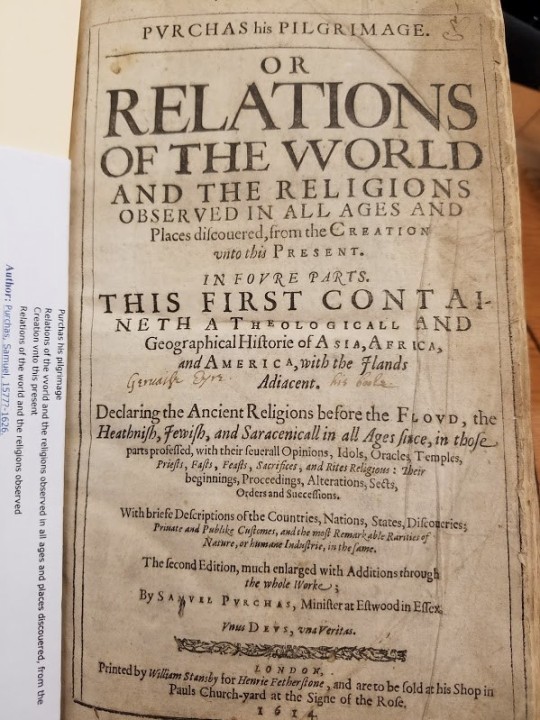

Purchas His Pilgrimage, or Relations of the World, Samuel Purchas, 1614

This book is an encyclopedic work, which describes various religions, their practices, and briefly about the nation from which they originate. Samuel Purchas was a well-educated Anglican priest, who, despite the extent of his works, never left England. In fact, he collected this knowledge from the stories of sailors and the manuscripts of past travelers. One might wonder why 17th century Christians would be interested in the traditions of other cultures. This is clearly answered on the title page.

Under the author’s name is the phrase “Unus Deus, Una Veritas,” meaning “One God, One Truth.” Therefore, these descriptions of other cultures represent what is false in the world. In an era where Europe is exploring and missioning to these places it would make sense to try and understand the culture of the native people. Purchas calls this his “pilgrimage.” This book therefore has a religious function. It is not a literal journey but a metaphoric journey around the world. The knowledge gained on this journey could allow others to better conduct their mission work in these countries.

But the book also functions to justify the growing authority of Christianity in these places. In one description of religious practice in China, the author writes that when people “obtain not their requests [to the Gods], they will whip and beat these Gods.” It is clear that these people do not understand the reverence and proper worship that Europeans do. This likely pleased, the Archbishop of Canterbury George Abbot, to whom the dedicatory epistle is written.

Another indication of its intended use by the clergy is the numerous printed notes in the margin. These often give evidence for what has been written or more avenues for research. The notes may be in Latin, Greek, or English, which implies the reader must have had the education to understand these annotations. The clergy would have learned Greek to read some of the oldest versions of the Bible and Latin for most church documents up until the reformation.

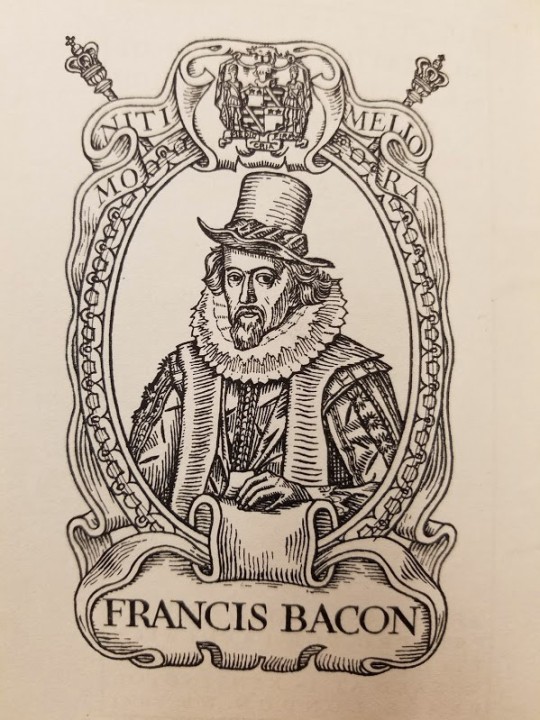

Essayes- Religious Meditations- Places of Perswasion and Disswasion, Francis Bacon, Originally Published 1597, Haslewood Edition: 1924

This collection of writings from philosopher and scientist Francis Bacon covers a wide variety of topics from a “regiment of health” to “atheism.” I am most interested in the middle text of the three works included in this book. It is called the “Meditationes Sacrae” or “Sacred Meditations.” This work is completely in Latin despite the other texts of this book being in English. Bacon must have had a sense that for anyone to take you seriously when writing about religious matters you had to write in Latin. In these short meditations he discusses common religious concerns such as the nature of Christ’s miracles and controversies between Church and scripture. This was likely regarded as a useful and edifying book in its time.

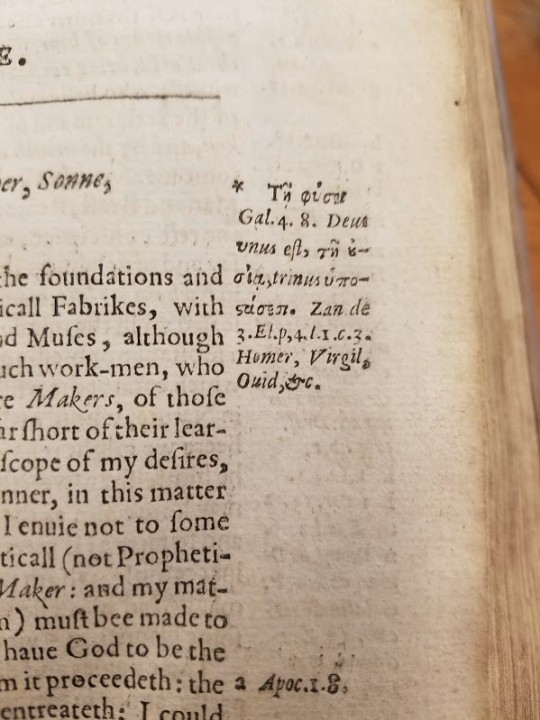

While one could make some interesting points about how Bacon’s logical scientific method influenced his religious beliefs, the fact that a facsimile was published more than three hundred years after it was originally published raises equally interesting ideas. While the book says it is an exact copy, “page for page and line for line,” of the first edition octavo this is not quite true. The note in the front of the book reveals that the outdated “f” has been replaced with the modern “s.” The frontispiece, shown above, is also redrawn from a different work of Bacon’s. It is also interesting that the editor’s note points out that this version is not the most well known, because Bacon continued to add to and edit these essays for many years.

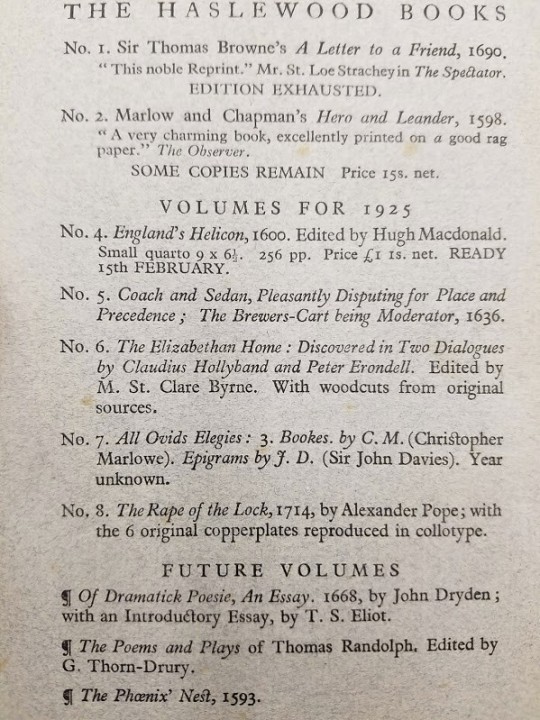

This book is neither the text that made it famous nor a totally accurate copy of the original so perhaps the purpose is not for it to be read but to be collected. Part of the challenge and fun of collecting is the rarity of the object. For instance, you could go to a comic book store and buy any new comic and there’s no challenge there. But if you want issue #134 of Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen to complete your collection of Jack Kirby comics it’s a lot harder. So the publisher has created this sort of challenge by limiting the number of copies printed. This book had a run of only 975 books.

Artist and architect Frederick Etchells founded Haslewood Press, the publisher of this book. This explains why this book is an object of aesthetic value. It was printed on all cotton paper with a deckled edge that gives the appearance of the paper being handmade. The top edge is gilt. It is these small details that make the book more beautiful almost to the point that it does not matter which classic work of literature it is. The back of this book is an advertisement for other books from this publisher. To promote the collecting of this series it announces that their copies of the first book have been “exhausted” and that only “some copies remain” of the second. Also interesting, is a review of one book, which describes the contents as “charming” but the printing to be “excellent” on “good rag paper.” A list of the upcoming books with their unique features is also included. These details further convey that in the case of these reprints, it seems more important to have a beautiful library of famous books than to be particularly invested in the contents of the book.

-Mark Connor, University of Pittsburgh undergraduate

#books#bookhistory#bookstudies#historyofthebook#bibliophile#bibliography#samuel purchas#religion#francis bacon#scpittclasses

24 notes

·

View notes