Rare books and printed material at the University of Pittsburgh - part of Archives & Special Collections. Statements made and opinions expressed on these pages are those of the authors alone and not of the University Library System. Be Sure to check out our other blog, Archives & Manuscripts @ Pitt for posts on archival and manuscript collections.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Community of Resistance: Losing and Rediscovering Queer Solidarity in Pittsburgh

This post is written by Sarah Trexler, a recipient of an Archival Scholar Research Award for the 2024 Spring Semester.

My project offers a comparative analysis of Pittsburgh��s queer communities and social life in the 1970s, the 1990s, and the twenty-first century. Along with other communities around the country, queer individuals in Pittsburgh faced a variety of implicit and explicit discrimination, fed by the conservative turn towards a more hetero- and cis-normative culture after the Second World War. In response to direct systemic violence and social isolation, queer people began to create their own community spaces where they could turn for resources, support and mutual aid.

My interest in this topic began as I consumed queer media, specifically Sapphic media like Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues and the 2022 reproduction of A League of Their Own. In these sources, I noticed the role of gay bars in the formation of identities, relationships, and communities. At a time when being queer in public could attract danger and violence, bars were safe havens of free love and expression. However, bar spaces were not always conducive to conversation and there were many, young, sober, or otherwise inhibited, queer people who had to seek other spaces. Outside of bars, there were more accessible and inclusive queer-created spaces such as bookstores, restaurants, and coffeeshops – some of which existed right in Pittsburgh.

My curiosity brought me to the University of Pittsburgh Library System's Archives & Special Collections, where I began my work with the Pittsburgh Gay News, a newspaper published during the 1970s. Flipping through the pages brought me to a new time and place. One in which the vibrancy and joy of queer community was documented by queer people for queer people.

(Above) Excerpt from Gay News. Pittsburgh: Gay Alternatives Pittsburgh (Issue 11: 1974). Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Although my research began with queer periodicals from the 70s, I soon realized that my project was much larger than that. Newspapers did not tell the whole story of the spaces that I was studying – I was lucky if I got a few pictures. But when the addresses became familiar and recognizable, I wanted to know more. What were these spaces like? Who patronized them? And most importantly – where did they go?

In an attempt to situate my findings in a larger timeline, I broadened my horizons. In addition to queer periodicals, I also found event fliers and records from local businesses and organizations, like the Persad Center and Donny’s Place, useful to my research. I also began considering archival materials from the 1990s, hoping to find discussion of the big names in the Pittsburgh queer community of the 1970s. Unfortunately, this investigation only yielded more questions.

(Above) Act Up! Pittsburgh Advertisement in 1993 Pittsburgh Pride program. “A Family of Pride: 1993 Pittsburgh Pride”, Archives of Industrial Society (AIS) Information Files, Pittsburgh Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Pride Celebration, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

I had been hoping to pick up the same names and patterns that I noticed in the sources from the 70s, but the queer community had undergone a dramatic shift as a result of the AIDS epidemic. The vibrancy and joy that I had noticed in earlier media was subdued – cluttered with statistics, infection rates, and mutual aid requests. There was still a strong element of community, but it had moved out of the bars and physical spaces of the earlier decades. Instead, it was found more in support groups, PSAs, and volunteer opportunities. I also found no mention of the earlier community spaces. Mentions of new bars and coffeehouses popped up, again with familiar addresses, but those proved to be dead ends as well. When I attempted to uncover the stories of these places, I found that those stories too were left unfinished. Queer spaces from the 1970s and 1990s were since turned into furniture stores, car dealerships, or simply left abandoned.

My questions continued to pile up and all I could find were unfinished stories. It was a disheartening and isolating experience – to not know my history and not even know where to look. I created working relationships across several archives, including Carnegie Mellon and the Heinz History Center, searching for the lost lives and stories of this earlier generation. I eventually came to realize that the absence of answers to my questions and solutions to my problems were answers and solutions in and of themselves.

(Above) Shawn’s Place bar, once located in Downtown Pittsburgh (April 1995). [Photograph]. Donald Thinnes Papers. Detre Library and Archives, Heinz History Center, Pittsburgh.

Queer stories were never intentionally recorded. Understanding this scarcity gave me a new insight into the value of community and queer joy where you can find it. I came to treasure the photographs, letters, and even the obituaries that commemorated lives full of love. I became inspired. Instead of leaving my work in the past, I want to set a tone for the future. I have created a contemporary archive of sorts to record my community’s joy, love, and stories. It will be a place for people to honor and appreciate their friends and space.

To learn more and contribute to my project, visit: https://forms.gle/RLVVV1tw3ReEL48G8

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trust in Trans Becomings

This post is written by Vasudha (they/them), a Brackenridge Fellow in the David C. Frederick Honors College and a fourth year undergraduate student majoring in Natural Sciences and Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies.

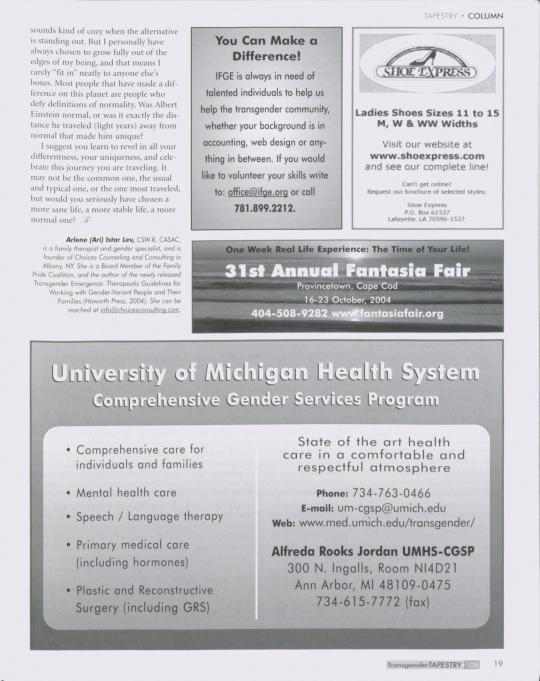

My time with the transgender underground press in the Hillman Archives & Special Collections lead me to think about how trans pasts and trans presents are intertwined, especially with trans people being heavily scrutinized in our current political climate. Bans against gender-inclusive books, drag shows (1), and gender affirming healthcare (2) are being proposed and even passed at state-wide levels in an attempt to eradicate “gender ideology”, at the cost of the trans community’s safety and well-being. In looking through issues of TV-TS Tapestry, which was later renamed Transgender Tapestry, I found one trans political narrative from the past that is still present today, although in different language.

Detransitioning stories have been used often as conservative talking points for why gender affirming care should be limited, framing it as causing irrevocable harm to those who supposedly hopped on the “trans train” without a second thought, and ultimately regretted their decision (3). In a 1988 issue of Tapestry, the term “pseudo-transsexual” was used to describe people who were convinced they were trans, but were instead “very confused” and “emotionally disabled”, in the words of Sister Mary Elizabeth.

(Above) Excerpt from "Sy Rogers and the 700 Club: A Response" by Sr. Mary Elizabeth, n/SSE, The TV-TS Tapestry, Issue 52, pg 46-47, 1988. University of Pittsburgh Library System, Archives & Special Collections.

As a devout Christian nun, the words of Sister Mary may seem like they come from a place of compassion and concern, seeing as she places blame on the religious community for condemning gender-diverse people, turning them away from God (see third paragraph of the above excerpt). But as a White trans woman, Sister Mary’s words only serve to cast doubt on the self-knowledge of trans people of color and other marginalized trans people, whose trans identity is more likely to be written off as false or self-convinced (4). This doubt quickly becomes reason to turn them away from receiving care, giving providers the power to choose who is “really” trans, and who isn’t.

(Above) Image of Sr. Mary Elizabeth with Christine Jorgensen at the International Foundation for Gender Education 'Coming Together' Convention in 1988 from "Sy Rogers and the 700 Club: A Response" by Sr. Mary Elizabeth, n/SSE, The TV-TS Tapestry, Issue 52, pg 46-47, 1988. University of Pittsburgh Library System, Archives & Special Collections.

Today, narratives of detransitioning are covertly doing the same by feigning concern for those who were supposedly coerced into receiving gender affirming care by the “transgender ideology” spread by trans people and enabled by medical caregivers. Politicized detransitioning organizations encourage those who detransition to sue their physicians, effectively scaring well-meaning providers off from treating patients who they deem “emotionally unfit” to transition, and pushing medical practitioners to question the self-knowledge of their patients.

In addition, restricting doubt from trans experiences has related implications. In Transgender Tapestry’s Summer 2005 “Ask Ari” column, a trans woman admits to feeling doubtful about medically transitioning. Ari responds to reassure her that although medical professionals make it difficult to voice these feelings, it is completely normal for trans people to have fears surrounding the process of transitioning.

(Above) "Ask Ari" Column from Transgender Tapestry, Issue 108, pages 18-19, Summer 2005, University of Pittsburgh Library System, Archives & Special Collections.

I resonated with this column as someone who has felt illegitimate for experiencing trans doubt myself, and I realized that we’ve been conditioned to feel that way through medical practices. Throughout the history of trans medical care, diagnostic criteria have included experiencing mental distress in the form of gender dysphoria (formerly known as gender identity disorder) to be eligible for care. Until last year, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) required a psychologist recommendation and diagnosis for patients to be able to receive care. Although this has been removed from their standards of care, a majority of clinics still use this criteria, which in many cases doesn’t allow for trans doubt to be explored without disqualifying patients from care.

Many trans people do have doubts and fears about medically transitioning, and it’s important that these feelings can be spoken about freely so that patients can be honest about their trans experiences and trust providers with their care. If a patient is forced to exaggerate their need for care in order to be trusted and qualified to receive it, there is no space for real conversations about a patient’s needs and what they hope to achieve through gender affirming care, which is what may lead to experiences of detransitioning (in the way that conservatives view it) in the first place.

Looking into snippets of trans history provided me with a better sense of trans experiences in today’s world, by being able to see similarities at the core of trans issues throughout time. Trans archival materials serve an important purpose of reminding us that trans people have always been here, and have been fighting the same anti-trans sentiments for centuries, although they may seem different today. They give us the strength to keep fighting.

Footnotes & Works Cited

Garnand, Ileana. "How drag bans fit into larger attacks on transgender rights." The Center for Public Integrity, April 14, 2023.

HRC Foundation. "Map: Attacks on Gender Affirming Care by State." Human Rights Coalition, Accessed August 8, 2023.

For a better understanding of more common reasons for detransitioning, see this NIH article: Turban, Jack L., et. al., "Factors Leading to "Detransition" Among Transgender and Gender Diverse People in the United States: A Mixed-Methods Analysis." LGBT Health, May/June 2023; 8(4): 273-280. DOI: 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0437. Accessed August 8, 2023.

For a detailed archive-based history on racialized medical gatekeeping of gender affirming care, read Chapter 5 of Jules Gill-Peterson’s Histories of the Transgender Child, titled “Transgendered Boyhood, Race, and Puberty in the 1970s”.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anxiety and Stress by Susan Lark: Advice for Coping with Anxiety from the 1990s Popular Psychology Text in Archives & Special Collections

This blog post was written by Taylor Brooks, a student employee in Archives & Special Collections.

I am a Psychology/ Social Work major and I chose to write about this topic because it hits close to home for me. As a student, anxiety levels can increase, so I wanted to bring some light to this topic and help give ways to cope with it.

Anxiety is something that most people deal with at some point in their lives. Anxiety can mean a person is in a state of being uneasy, apprehensive, or worried. The feeling of anxiety can often make a person feel that they are powerless in a situation. It is one of the most inevitable parts of life. There are many different types of anxiety, according to the Diagnostic Statistics Manual-3 (DSM), including social anxiety, generalized anxiety, OCD, PTSD, and many others.

(Above) Cover of Anxiety and Stress by Susan Lark, 1993. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

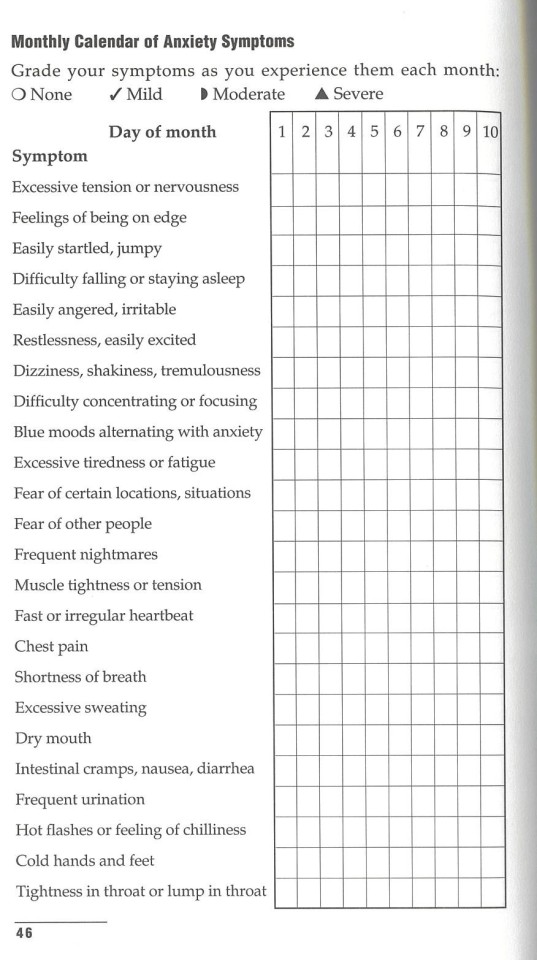

In the 1993 book Anxiety and Stress by Susan Lark, held by Archives & Special Collections, Lark explains some of the risk factors of anxiety. “These include physiological imbalance, genetic factors, family programming, major long and short-term life stresses, and personal belief systems.” Self-evaluation can help people become aware of possible risk factors based on lifestyle habits, as well as the existence of health problems that can trigger anxiety symptoms.

Lark goes over many ways you can better your anxiety. In her book, she shows how eating healthier foods can play a role in preventing and relieving anxiety and stress. Breathing exercises help because you are getting more oxygen into your body and allowing your body to regulate itself. If you do breathing exercises while having a panic attack it can help, give you something else to focus on and be able to calm down. Physical exercise can help “discharge physical and emotional tension that accompanies a vigorous session of exercise directly and immediately reduces anxiety and stress.”

(Above) “Monthly Calendar of Anxiety Symptoms” worksheet, page 46, Anxiety and Stress by Susan Lark, 1993. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Currently in 2022 the CDC estimates 9.4 percent of children, ages 3-17, have been diagnosed with anxiety. Anxiety symptoms are common in all children at various times and circumstances. Anxiety interferes with cognitive processing. “It is possible that a child or adolescent might be miserable and show significant social maladjustment but maintain acceptable school performance.”

Work Cited

Cambridge University Press. DSM-III: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition. 3rd ed., The American Psychiatric Association, 1985.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 13). Anxiety and depression in children: Get the facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/features/anxiety-depression-children.html#:~:text=Anxiety%20and%20depression%20affect%20many,diagnosed%20anxiety%20in%202016%2D2019.

House, Alvin. DSM-IV Diagnosis in the Schools, Revised Edition. Guilford Publications, 2002.

Lark, Susan. Anxiety and Stress: A Self-Help Program (The Women’s Health Series). Westchester Pub Co, 1993.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harmonia Macrocosmica or Atlas Universalis Et Novus

This post was written by Natasha Skorupski, a Department of Classics Intern in Archives & Special Collections for the Spring of 2022.

Archives & Special Collections at the University of Pittsburgh holds many rare books and printed materials. During my internship with the Hillman library and the Classics Department, I came across an interesting book: Harmonia Macrocosmica or Atlas Universalis Et Novus created by Andreas Cellarius and published in 1708. However, it was not the words or even the illustrations that interested me; instead I was taken by how the book was printed. The images and texts seemed to be printed on one page and then that page was bound to another.

(Above) If you look very closely you can see a faded line parallel to the final bordering black line. The faded line marks where the page, containing the colored print and illustrations, is adhered to the blank page that is part of the bound book.

For hours I searched trying to figure out the name and more about this process. Eventually I came upon a small bit of information. Tip in (or tipping-in) printing is when a printed sheet is inserted into a book or manuscript by gluing (or stapling) it to an existing page. However, the printed page is not part of the book’s binding (Glossary of Book Terms). This was exactly what I was looking for, except after discovering this, I could find absolutely nothing directly about its history. From searching many different sources and putting pieces together, I came across this conclusion—the original printed pages were mass produced and then (at least for this manuscript) the illustrations were hand painted in, and the paint looks quite similar to a watercolor based paint.

Having the pages as individual sheets allows for multiple people to be working on the pages at once, and also allows the artist to immediately move to the next page without having to wait around for the paint to dry. Whenever the paint on the page has dried, it can be bound or glued to a bound book. This is a slower process as only one page can be done at a time, and the glue/paste binding the pages together must fully dry before one is able to move onto the next page. While it was hard finding out about the background of these types of books, there were numerous resources on how to paste bookplates and individual pages into a book.

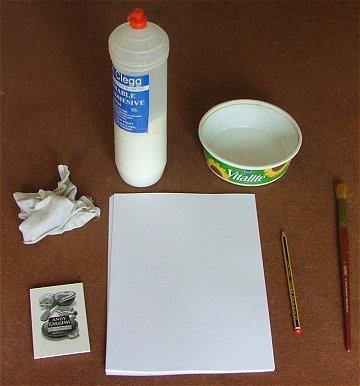

The process of binding pages together is extremely simple and is precisely what you think it would be. There are tiny variations in the process, but I will explain to you the one I found on the website of wood engraver and illustrator Andy English. The materials he used were a bookplate, scrap paper, pencil, small brush (good enough to avoid bristles detaching themselves), glue, a soft cleaning cloth, and a container to mix in (English).

(Above) Image from “Pasting Bookplates into Your Books” by Andy English, 2021.

He recommended PVA (Polyvinyl acetate) glue as it is easily thinned with water, flexible, and acid free. This is important as his mixture is about 60% glue and 40% water, with is mixed in the container. However, he notes that he uses a little less water for paperbacks. Before you start, make sure to wash your hands and keep them clean at all stages. Take the bookplate/page you wish to attach and place it on the book/page where you want it. If you wish, you may mark in faint pencil marks the corners of where the attached page will go. Once the mixture is made, place the bookplate/page face down on a clean piece of scrap paper (photocopy paper is perfect). Take some paste on the brush and (holding the plate firmly with a finger) brush the paste on the bookplate/page from the center going outwards (English).

(Above) Image from “Pasting Bookplates into Your Books” by Andy English, 2021.

It is important not to overload the plate with paste! Once the paste is on, take the bookplate/page and hold it above where you want to place it in the book. Then carefully, but deliberately, place it onto the book and smooth it down. If there is a little too much glue, use a clean cloth (lightly dampen with clean water) to wipe it carefully and use light pressure to avoid damaging the surface of the paper (English).

(Above) Image from “Pasting Bookplates into Your Books” by Andy English, 2021.

Lastly, leave the book open until it has thoroughly dried.

Works Cited

English, Andy. “Pasting Bookplates into Your Books.” Pasting In Your Bookplates, PB Hosts, 2021, https://www.andyenglish.com/pasting-in-your-bookplates.

“Glossary of Book Terms.” AbeBooks, AbeBooks, 28 Mar. 2022, https://www.abebooks.com/books/rarebooks/collecting-guide/understanding-rare-books/glossary.shtml#T.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I started to wonder about the history of Latin”

This post was written by Natasha Skorupski, a Department of Classics Intern in Archives & Special Collections for the Spring of 2022.

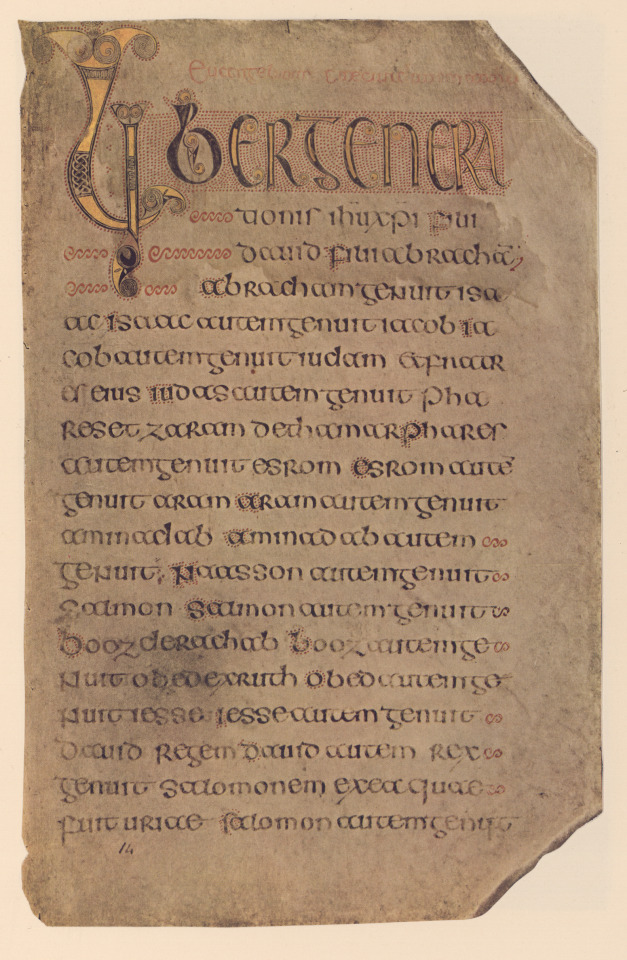

During my internship with the Hillman library and the Classics Department of the University of Pittsburgh I worked in the Archives & Special Collections, looking over Latin manuscripts. While looking through these I started to wonder about the history of Latin and how the spoken language fell yet the written word continued.

(Above) Evangeliorum quattuor Codex Durmachensis or The Book of Durrow, Olten: Urs Graf; sole distributors in the United States: P.C. Duschnes, New York by Arturus Aston Luce, 1960 facsimile. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Due to that I have found out the following information. Latin is thought to be derived from ancient Greek and Italic languages. Italy used to be made up of many different tribes that spoke many different languages, and these languages are called Italic languages today. The first evidence of Latin is an inscription on a cloak pin that was found from the sixth century BCE. On the pin it says, “Manius me fhefhaked Numasioi” which translates to “Manius made me [this] for Numerius”. The first literary records of Latin have been dated back to 250-100 BCE. The popularity of Latin increased with the rise of Roman political power. This spread was initially in Italy and then continued to most of Western Europe and parts of coastal Africa.

Latin has been classified into three groups. There is the written Latin, oratorical Latin (public speaking), and colloquial Latin (common speaking) (When Did Latin Die? and Why). The later Latin saw the greatest variation in its use and continuous divergence from it eventually evolved into Vulgar Latin. From Vulgar Latin we get the Romance Languages we know today, which include Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Romanian.

The beginning of the end of the western Roman empire occurred in 395 CE. It fell for multiple reasons, some of them being military invasions, economic troubles, overreliance on enslaved labor, overexpansion and overspending of the military, political instability and corruption, among others (Andrews). With this fall came the decline of colloquial and Vulgar Latin.

There was a small period of resurrection for Latin under the “Roman Emperor” Charlemagne during 768-814AD. At this point in time, Latin was spoken, written, and read predominantly in religious settings as Italian, French and Spanish were rapidly evolving, allowing for a great decline of Latin (When Did Latin Die? and Why). During the mid-14th century, the Black Death Plague occurred. It killed millions of people, including numerous scholars and professors, creating a negative ripple effect on the entire education system (When Did Latin Die? and Why).

During the 15th and 16th centuries, there was another slight resurgence as people started to read Latin literature from classical authors. This was the time of the renaissance that spread mostly through Italy, France and later Britain. With the greater developments in science, Latin terminology was put into place as a way to regulate findings and encourage international research (When Did Latin Die? and Why).

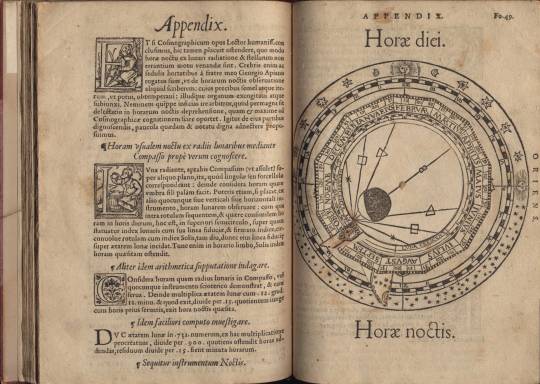

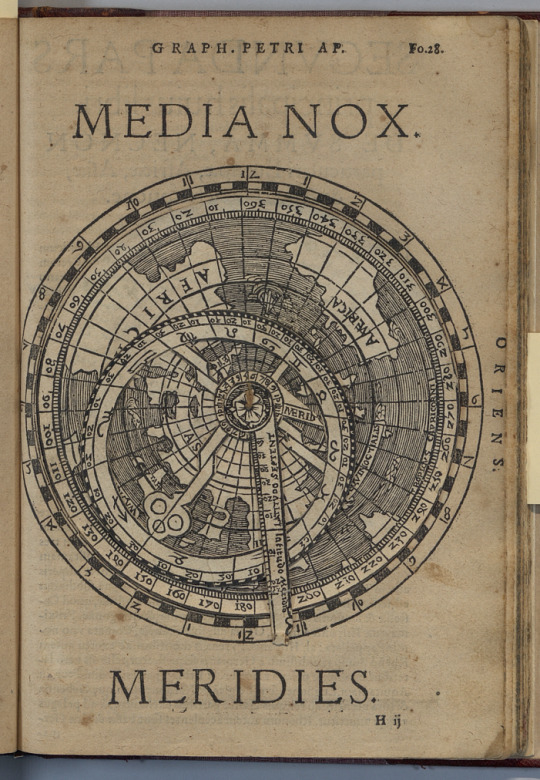

(Above) Cosmographia Petri Apiani. Antwerp: Veneunt Antuerpiæ Gregorio Bontio sub Scuto Basiliensi .. by P. & Gemma Apian, 1553. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Latin was seen as a status symbol at this point—you were seen as educated if you could read and write it. Though it was no longer spoken, it was used predominantly in literature and religion. Until the 19th century, Latin was a requirement for all that attended college. College was usually attended by white males of a privileged background (When Did Latin Die? and Why). However, this changed around the mid 1960s when the younger generation decided they also shared the right to higher education.

Today very few people can read Latin, even fewer can write it, and almost no one speaks it. However, it is one of the official languages of Vatican City and plays a vital role in Catholicism. Latin words are all over Catholic scripture and there are many recited terms that come from it (Is Latin a Dead Language? Let's Explore Why?).

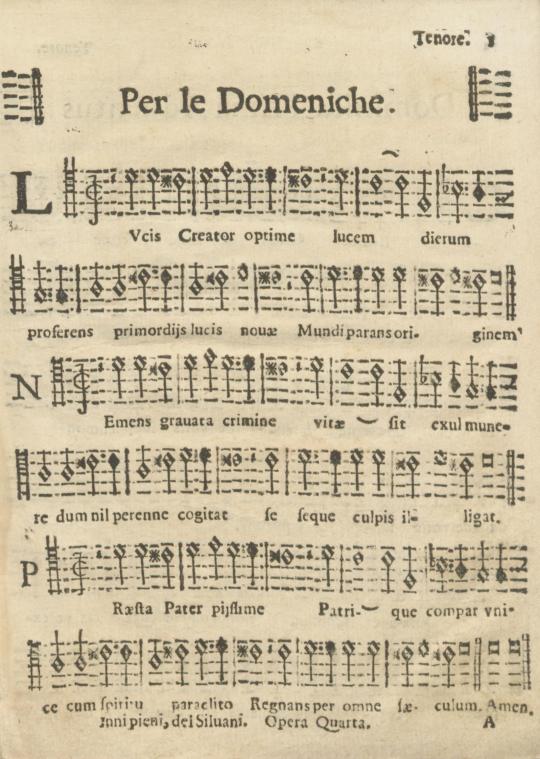

(Above) Inni sacri, per tutto l’anno : à quattro voci pieni, da cantarsi con l’organo e senza ... : opera quarta by G. A Silvani, 1705. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

A fun fact, Pope Francis is the most influential Latin speaker today with about 40 million followers between his multiple accounts that vary in languages. One of these accounts posts solely in Latin! With his bio stating “Tuus adventus in paginam publicam Papae Francisci breviloquentis optatissimus est” which roughly translates to “Your arrival to the public page of the Tweeting Pope Francis is most welcome” (Pope Francis).

Latin words also dominate in modern science as names of medicine, drugs, diseases, body parts, and it is especially used in binomial nomenclature (the system for naming plants and animals). It is also greatly prevalent in the legal field. Amicus curiae, habeas corpus, and ex post facto being just a few of the more common ones. A fun fact is the jury comes from the Latin word “jurare” meaning “to swear” (Is Latin a Dead Language? Let's Explore Why?).

Latin is a dead language as it is no longer spoken. However it is not extinct, and still can be encountered more than most people in the world today would expect.

Works Cited

Andrews, Evan. “8 Reasons Why Rome Fell.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 14 Jan. 2014, https://www.history.com/news/8-reasons-why-rome-fell.

“Is Latin a Dead Language? Let's Explore Why?” The Language Doctors, 14 Mar. 2022, https://thelanguagedoctors.org/is-latin-a-dead-language/.

Pope Francis. “Pope Francis Tweeter Account.” Twitter, Twitter, 23 Apr. 2022, https://twitter.com/pontifex_ln?lang=en.

“When Did Latin Die? and Why?” Global Language Services, Global Language Services Ltd, 3 Feb. 2022, https://www.globallanguageservices.co.uk/did-latin-die/.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Guide to Perfecting Femininity: Virginia Prince’s “How to Be a Woman Though Male”

This post was written by Tayler Fane, a recipient of an Archival Scholar Research Award for the 2022 Spring Semester.

“[By embracing your femmeself], you will…put yourself that much nearer the future—not a time when all men will wear skirts, they are only symbols, but a time when the polarization of our present culture will have been vastly modified; to a time when all people—males and females alike—will be able to express their reactions to a given environmental or emotional situation by whatever means and mechanisms seem appropriate and satisfying to them at the moment” (Prince 117).

(Above) Author photograph of Virginia Prince, featured in How To Be a Woman Though Male, 1987.

Virginia Prince (1912-2009) was a self-proclaimed “transgenderist” educator and activist who dedicated her time to providing information for heterosexual crossdressers. As the founder of Transvestia, a magazine dedicated to creating a social and educational resource for crossdressers to communicate and share their stories, Prince helped create a sense of belonging within the crossdressing community for 20 years. Prince also founded the Alpha Chapter of the Foundation for Full Personality Expression (FPE) which became the Society for the Second Self, or Tri Ess, in 1975.

(Above) Cover of How To Be a Woman Though Male, 1987.

At 55, Virginia Prince began living as a woman full-time. A few years after transitioning, Prince first published her influential book How To Be a Woman Though Male in 1971. Archives & Special Collections at the University of Pittsburgh Libraries holds an edition of the 6th printing from 1987. This book acted as a guide for heterosexual crossdressers, providing information on the physical, cosmetic, and aesthetic elements of fully embracing one’s feminine self and how to successfully pass as a “real” woman.

The book is split into 14 chapters. The first 11 give readers tips and tricks on how to dress, accessorize and behave in manners that emphasize one’s feminine traits and suppress one’s masculine traits. While Prince did not believe that crossdressing required one to abandon their masculine traits completely, she did believe that the goal of crossdressing was to be as good looking a woman as possible, which requires careful attention to the details that help flatter and femininize one’s appearance to create a realistic transformation.

(Above) “Useful Hair Styles I” illustration on page 38 of How To Be a Woman Though Male, 1987.

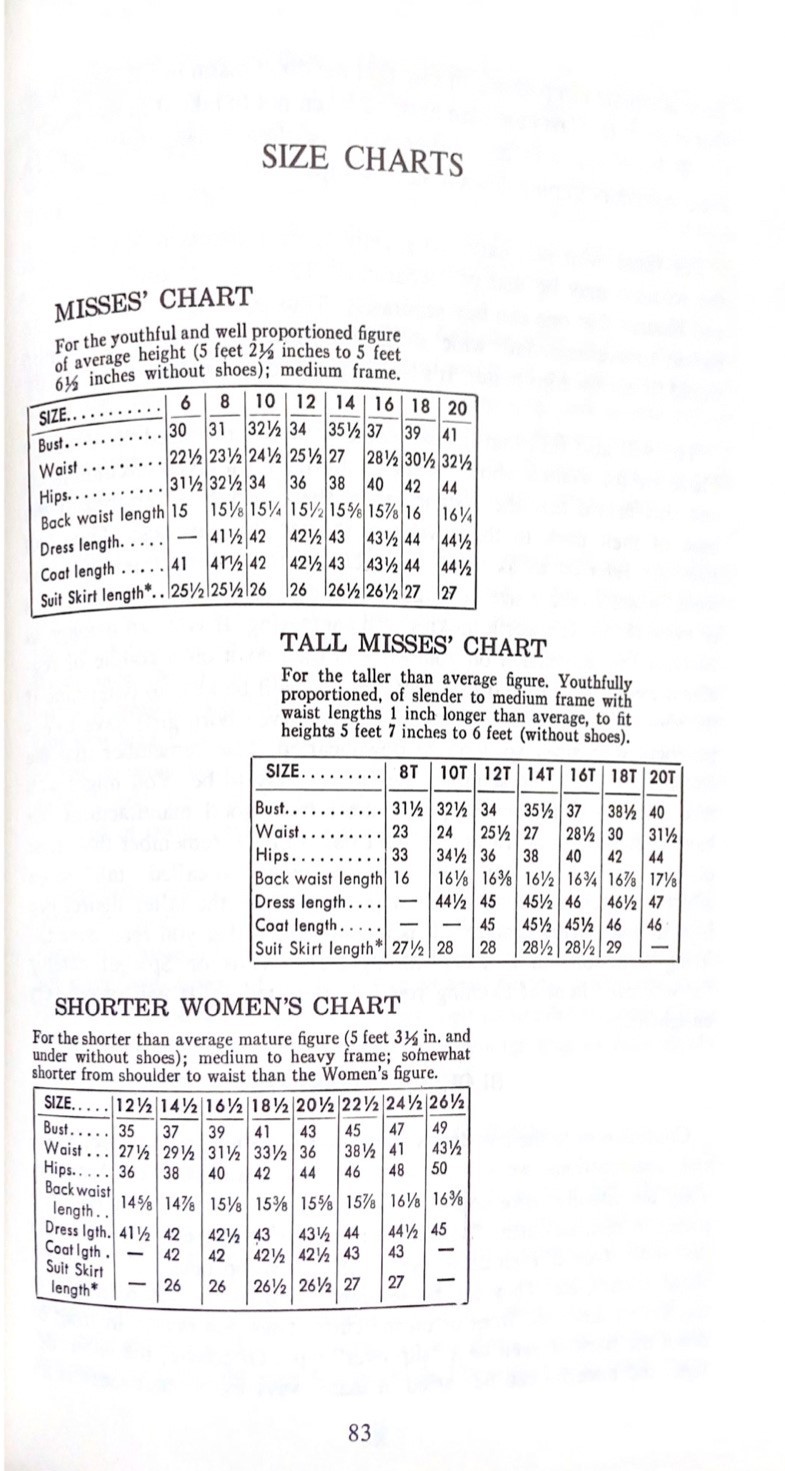

(Above) “Size charts” on page 83 of How To Be a Woman Though Male, 1987.

In the last three chapters of How To Be a Woman Though Male, Prince provides her insight on the distinction between sex and gender and the difference between transgender and transsexual identities. While transgender and transsexual essentially mean the same thing today, these two terms represented two different experiences of transness in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. Prince believed that a little boy’s desire to “be a girl” was not the same as the desire to “be a female,” and that the distinction between the two was crucial to fully understanding transgender and transsexual identities. Prince argued that most individuals who found themselves longing to transition only wanted to adopt the gender, or patterns of behavior and social roles, of their counterparts, and that sex was rarely considered or acknowledged in these feelings. Because of this, Prince argued that most folks could satisfy these feelings by simply crossdressing or learning to live as a woman full-time and that surgeries to affirm one’s gender was often misguided and unnecessary to transition.

While some of Virginia Prince’s views of the trans community do not reflect what we believe and know today, her works provided crucial information that helped pioneer trans research and community building. Prince’s activism and dedication to her community is the blueprint for how embracing one’s identity also entails giving back to your community and helping others reach that same sense of self-love and acceptance. Prince book How To Be a Woman Though Male as well as issues of her magazine Transvestia can be found at the Archives & Special Collections at the University of Pittsburgh.

Works Cited

Prince, Virginia. How To Be a Woman Though Male. Chevalier Publications, 1987.

“Virginia Prince & Transvestia.” University of Victoria, https://www.uvic.ca/transgenderarchives/collections/virgina-prince/index.php.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Power and Popularity of Periodical Publication

This blog post was written by Maddy Dean, a student in Dr. Jessica FitzPatrick’s ENGLIT 0512 Narrative and Technology Course. This class visited Archives & Special Collections in the Fall 2021 term.

Since the 19th century, narrative technologies have appealed to the masses publicly through periodical printing – even the traditional novel started appearing periodically throughout publications. Charles Dickens’ “The Personal History of David Copperfield” (1849-1850) and Ernest Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms" in Scribner’s magazine (1929) were published monthly for distribution to the public, with advertisements and the inclusion of other fiction pieces to be consumed and shared between friends and families.

(Above) An advertisement for Home Goods in Scribner’s October issue. Hemingway, Ernest. “A Farewell to Arms.” Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1929. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Bookending each of Hemingway’s and Dickens’ serial fictions, the advertisements invite readers to browse different products, services, and even books before diving into a volume of the novel. These ads offer a level of interactivity and immersion that can almost be equated to ads we see on television or online today. Readers had the choice of either skipping over ads and diving straight into the magazine pieces or browsing the columns for things like household furniture or printing services (pictured above). An interesting feature of the narrative discourse offered in these magazines is the inclusion of ads for books and publications by authors other than Hemingway or Dickens. Advertising other pieces informs readers of new stories and authors, but it also takes away from the idea of single authorship in a book since the novel appears in a periodical, not in traditional book format.

These ads also suggest the type of audience who read magazine fictions, with home goods and beauty services appealing to the public. Ads for printing services and other stories indicate that readers of Hemingway and Dickens were also interested in reading other works and maybe even publishing their own (pictured below). They show that narratives are not always composed of just a story but include other elements that invite readers to browse their contents and choose what they want to read. Ads act as element of narrative discourse, changing how the novels are read and viewed through their inclusion either before or after the actual story. The magazines serve as a form of entertainment as well as advertisement.

(Above) an advertisement for copying machines in a volume of David Copperfield. Dickens, Charles, and Hablot Knight Browne. The Personal History of David Copperfield. 1st ed., Bradbury & Evans, 1849. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

The periodical printing of Hemingway’s and Dicken’s novels also suggests that audiences in this period preferred serialization for a quick read rather than consuming the novel in its entirety. Readers would pass the periodicals along to other families or cut them up for the print – ads that might be beneficial to save or special sections of the novel volume to be read again. Similar to magazines we might pick up in the check-out line at the grocery store today, audiences of magazine fictions passed along these novels or retired them to the bookshelf after consuming their content, eagerly waiting for publication of the next volume.

After exploring “A Farewell to Arms” in Scribner’s magazine and David Copperfield, it’s clear that readers engaged and appreciated narrative technology by buying a new volume each month, passing the stories onto others to share the great works of Hemingway and Dickens. These periodical magazines are comparable to current magazines and even streaming services that we interact with daily. Subscriptions, the inclusion of ads, and the choice to read (or watch) different stories is still present in narrative technologies and guides our understanding and experience of narratives. While narrative technologies constantly change, it’s evident that the audience consuming these narratives consists of the mass public, reading and absorbing new information as narrative form continues to evolve.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles, and Hablot Knight Browne. The Personal History of David Copperfield. 1st ed., Bradbury & Evans, 1849.

Hemingway, Ernest. A Farewell to Arms. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1929.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Psalmodia vespertina

This post was written by Nicole Arnold, Summer 2021 Classics Department Intern.

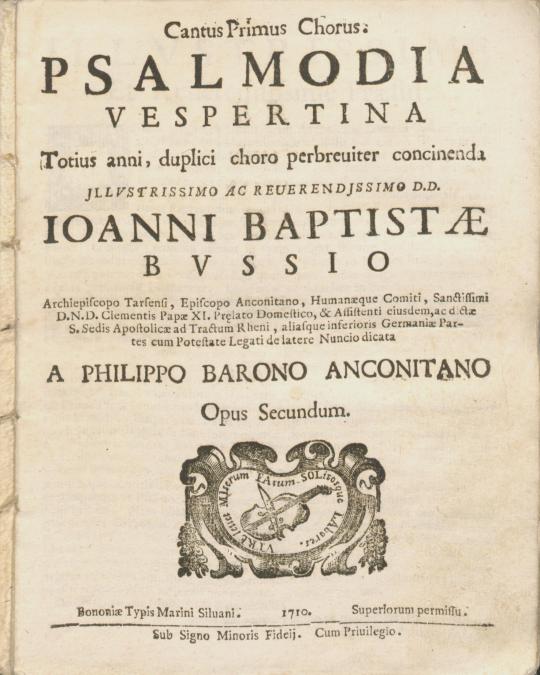

(Above: Title page, Psalmodia vespertina by Filippo Baroni, c. 1710, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System)

Like in any language, certain Latin words have different meanings in different contexts. Latin written in a religious context particularly changes the meanings of words. The Psalmodia vespertina, circa 1710, in the Archives & Special Collections contains a psalm that furthers this point.

The word “Domine,” which in Psalm 19 refers to God, is a form of the Latin noun “dominus.” In its purest form, “dominus” means “master.” However, in the religious context, it means “the Lord.” Using the word that means “master” is to indicate God’s almighty power. Furthermore, since “Domine” is in the vocative case, God is being addressed directly. It is best translated as “oh Lord.”

Other, more mundane words also take on different meanings with certain devices. For instance, the word “insaecula” technically does not exist in Latin. “Saecula” by itself has several meanings, such as “age” or “generation.” Adding the prefix “in-” changes the meaning, though; adding it makes the word “insaecula” mean “forever.”

Capitalization, much like in English, also gives words new weight in Latin. On its own, “patri” means “father.” However, when it is capitalized, “Father” takes on a religious meaning and refers to God. The same construction happens with “Filio,” meaning “son” or “son of God.” The word “sancto” is in a class of its own since the definition is literally “holy,” and modifies “Spiritui” to mean “the Holy Spirit.”

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Decacordum” and “Cithara”

This post was written by Nicole Arnold, Summer 2021 Classics Department Intern.

(Above: A modern approximation of a decacordum. Image from Liuteria Severini.)

One of the most constant aspects of music across time has been instruments. Even if their names are different than what they once were, the sound and function of the instrument is often the same. The instruments of ancient and medieval times very much inform the modern music world. Similar instruments often exist across multiple cultures and religions too. Churches in the Middle Ages included certain instruments in their music that had connections to ancient Greece and Rome, especially string instruments. Some of these included the decacordum and cithara.

The decacordum is defined as a ten-stringed instrument (perseus.tufts.edu). The prefix “deca” means “ten”; the “cordum” suffix refers to the strings. The word itself seems to have been a general term for ten-stringed instruments. Some scholars believe that ten-stringed instruments in the church referenced the ten commandments while the sides of them represented the four gospels. (Kolyada 31) Other sources, like the Musurgia Universalis (circa 1650) of University of Pittsburgh Library Systems’ Archives & Special Collections, describe the instrument’s strings as similar to a spiderweb. This is most likely in reference to their intricate weaving. Modern depictions of the instrument resemble a small harp. It is possible that could be what the spiderweb comment means; the trapezoid in a spiderweb looks much like the harp. The decacordum was one of several string instruments commonly used in the church.

(Above: Apollo, the Greek god of music, playing a cithara. Image from wikipedia.org.)

Another instrument of the medieval European church was the cithara. Although it was used like a harp in the church, the cithara originated in ancient Greece as a type of lyre, which resembled a guitar. The ancient Romans adopted it into their culture as well, and it became the most common instrument in Rome. It had anywhere between three and twelve strings. It is believed that “cithara” is the etymological stem of “guitar” (britannica.com). Descriptions of its features in medieval church music imply a resemblance between the two instruments. The “choking strap” of the cithara is mentioned in the psalm “Confitebor Angelorum,” in the Archives & Special Collections’ Psalmodia vespertina. (circa 1710) Since this instrument was a kind of lyre and had a strap that went around the neck, it can be inferred that the modern twelve-string guitar bears a resemblance to it. Notably, 21st-century musician Taylor Swift plays a twelve-string guitar rather than a typical six-string one; the doubled number of strings creates a more intricate sound.

youtube

(Above: Taylor Swift performing “Sparks Fly” on a twelve-string guitar. YouTube video.)

Works Cited

Kolyada, Y. (2014). A compendium of musical instruments and instrumental terminology in the bible. ProQuest Ebook Central <aonclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank') href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.Created from pitt-ebooks on 2021-06-14 20:13:12.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Kithara". Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Nov. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/art/kithara. Accessed 29 June 2021.

“Psalterium Decachordum.” Liuteria Severini, https://liuteriaseverini.it/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=90&Itemid=1030. Accessed 29 June 2021.

“Cithara.” Wikipedia,17 April 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cithara#/media/File:Apollo_Musagetes_Pio-Clementino_Inv310.jpg. Accessed 29 June 2021.

“Decachordum.” Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0059:entry=decachordum. Accessed 29 June 2021.

Kircher, Athanasius, and Jacobus Viva. Musurgia universalis; sive, Ars magna consoni et dissoni in X. libros digesta ... Romae: Ex typographia haeredum Francisci Corbelletti, 1650.

Baroni, Filippo. “Psalmodia vespertina: totius anni, duplici choro perbreuiter concinenda : opus secundum” Bononiæ: Typis Marini Siluani, 1710.

Swift, Taylor. “’Sparks Fly’ (acoustic) Live on the RED Tour!,” YouTube Video, 0:48, March 15, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nx-5bHeC6xo

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stripped Down: Ethical and Feminist Approaches to Archival Research

This post was written by Emily Kelly, a recipient of an Archival Scholar Research Award for the 2021 Spring Semester.

In the early phases of archival research, questions often center around the subject of the media. Who is being documented, why are they in the archive, who was left out of the archive, did the subject consent to being here? This is especially true in the delicate research of erotic art and alternative press such as On Our Backs, a lesbian erotica magazine that ran during the height of the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

There have been attempts to digitize the entire run, met with resistance related to the ethical concerns of digitizing nude bodies that only consented to their viewing in the print magazine. Tara Robertson wrote about the ethics of viewing images that were created for print being placed online. In a discussion with a model from On Our Backs, it was revealed that towards the end of the run, models were even promised their images wouldn’t be placed in online publications while signing copyrights for fear that their bodies would be, “Cut up and [made into] a collage.” (Robertson) In the article, the focus is very clearly centered on the subjects of the magazines being a minoritized group that could experience harm from the publication’s digitization.

On another note, the founder of the periodical, Debbi Sundahl (pictured below), wrote in her 1994 editorial “Battle Scars” about the empowerment that she and other women felt in their portrayals of sex and intimacy. She wrote about how the magazine refused to comply with expectations in production as well as readership, how the AIDS pandemic shaped the publication by the way of including safe sex practices, and how the heart of the magazine was always the team of women behind it. It was a place that was free of the patronizing male gaze that allowed for open exploration of sexuality among queer individuals.

(Above) Image of Debbie Sundhal from “Battle Scars,” On Our Backs, 1994. Photographed by Robert Pruzan ca. 1984.

This safety that comes within the magazine creates a cause for concern when digitizing the run. A digital archive would create a great deal of access to the content and broaden the audience that the magazine could meet, yes, but it would also open the women and individuals within the magazine to the public eye. While anyone could have gone and bought the magazine when it still lived on the shelves, there was a sense of community found within those who sought it out. With that community came an ethics of care, even while presenting criticisms.

The question of consent is of the utmost importance when digitizing any archival material, but it is especially important to realize that the reason archivists may abstain from creating a digital run of On Our Backs is not rooted in the continued censorship of female and queer bodies. Even more so when publishing ideas relating to this media to social media platforms such as Tumblr, which took an aggressive stance against “female-presenting nipples”, queer content, and content that relates to sex. (Community Guidelines) Any concerns that may arise from digitizing these publications are not founded upon censorship of sex, but upon concern and care for the bodies within them. The role of an archivist, and anyone who participates in the archive, is not one of judgment and decision making, but one of stewardship for the subjects within.

(Above) Cover, On Our Backs, Winter 1986

Citations

On Our Backs. San Francisco, CA: On Our Backs, 1984-2006. Print.

Sundahl, Debbi. “Battle Scars,” On Our Backs. San Francisco, CA : On Our Backs, 1994.

Robertson, Tara. “Update on On Our Backs and Reveal Digital.” Tara Robertson Consulting, August 27, 2016. https://tararobertson.ca/2016/oob-update/.

“Community Guidelines.” Tumblr. Accessed 6 March 2021. https://www.tumblr.com/policy/en/community

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christo-centrism in a Medieval Moralized Bible

This post was written by Charlie Taylor, a recipient of an Archival Scholar Research Award for the 2021 Spring Semester.

As part of my ASRA research, I’ve explored medieval illuminated manuscripts commissioned by queens of France, including this volume commissioned by Blanche of Castile. Blanche’s husband, Louis VIII of France, died when his heir was just 12 years old, and Blanche served as regent until Louis IX was old enough to take the throne. During her regency, which lasted from 1226 to 1234, she commissioned the Biblia de San Luis. The book is structured as a Bible moralisée, or moralized bible, intended to educate a young Louis on Christian doctrine and proper kingship.

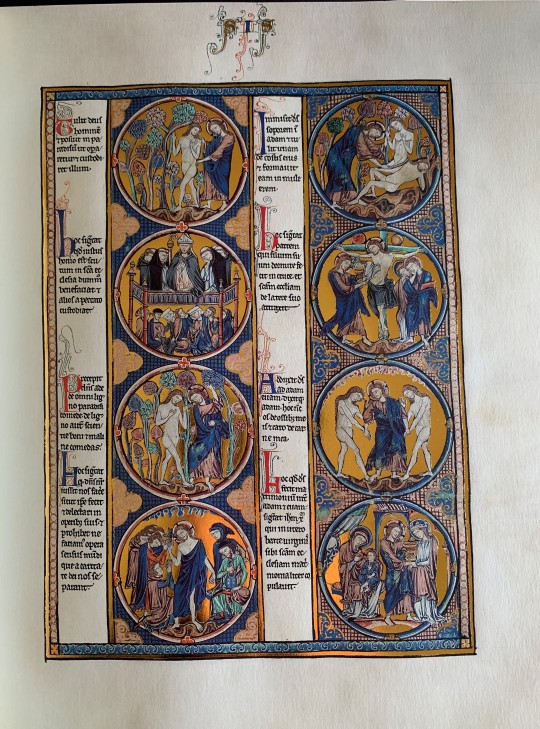

(Above) Excerpt from 2001 reproduction of Biblia de San Luis.

The page pictured above comes from a facsimile — a close reproduction made for scholarly purposes — of the Biblia de San Luis in Pitt’s Frick Fine Arts Library. The page contains two columns of text accompanied by illustrations, some of which depict scenes from the book of Genesis: at top left, God strolls with Adam in the Garden of Eden; at top right, God removes a rib from Adam to create Eve.

However, not every illustration shows a scene from Genesis. If we look again at the top right, immediately below the creation of Eve, we see Christ on the cross, with a figure emerging from a wound in his chest. What is Jesus doing in the book of Genesis? Why does explicitly Christian imagery appear on this page, when the life of Christ occurred centuries after the Hebrew Bible was written? Why does God have a cruciform halo — a halo containing the image of a cross?

Bibles moralisées don’t contain the entire text of the bible front to back; rather, they take stories from the bible and provide commentary on them, explaining their relationship to Christian doctrine. In the Biblia de San Luis, each roundel forms a pair with the one immediately below it, with the first scene taken from the bible and the second offering commentary.

It is important to note that the commentary in this bible represents a Christian-centric worldview and often dismisses Jewish readings of the text. The Biblia de San Luis treats the events of the Hebrew Bible as natural precursors to the events of the Christian Bible. Typology, as a form of commentary, takes certain events to foreshadow other events; this book asserts a typology in the creation of Eve and the creation of the Christian Church. In the second roundel, Ecclesia, a personification of the Church, emerges from Christ’s chest. The accompanying text explains that the scene from Genesis, in which God puts Adam to sleep and makes Eve from his rib, signifies God putting Christ to rest on the cross and pulling the Church from his side. Here, Christian doctrine (and the Church as an institution) becomes central to understanding the book of Genesis, pushing the story’s Jewish origins to the margins.

Works cited

William of Auvernge and Ramón Gonzálvez Ruiz. Biblia de San Luis. Barcelona: M. Moleiro, 2001.

Ferrante, Joan. “Blanche of Castile, Queen of France.” Epistolae, 2014. https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu/woman/77.html.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring Philosopher Carl Hempel's Connection to Chinese Philosophy

This post was written by Simone Mohite, a recipient of an Archival Scholar Research Award for the 2021 Spring Semester.

2020 has proved to be anything but ordinary. With the sudden onset of the coronavirus, millions of people comprising a non-scientific jury tried to determine the rules of survival. To wear a mask or not to wear a mask? Are vaccines safe or is the data weird? Is this science, or is it pseudo-science?

Although dismissive statements about science and questionable “scientific” claims in the public sphere are routine, the coronavirus epidemic has shown us that it is even more difficult to know who and what to trust when the doctors and scientists offer conflicting guidance. We all want to know the truth that science can tell us—in this case, to keep us safe—but what classifies something as science in the first place? To answer this question, I turned to philosopher Carl Gustav Hempel’s work on logical empiricism. I examined a manuscript from 1981 in which to understand how Hempel developed his ideas before they were ‘fixed’ into print and disseminated.

The manuscript I chose was titled “Logical empiricism: Its problems and changes.” It is the revised text of a lecture delivered by Hempel in China in 1981. On the very first page, there is a note that says, “Revised and Submitted to Hung.” I was curious to know why Hempel was in China giving this lecture on the recent history of Western philosophy. As it was towards the end of his career, I wanted to know if Hempel had taken an interest in Chinese Philosophy, or if philosophers in China had taken an interest in him.

(Above) Title with inscription “Revised, Submitted to Hung, 6/9/81,” Logical Empiricism: It’s Problems and It’s Changes by Carl G. Hempel, Box 57, Folder 7, Carl Gustav Hempel Papers, 1903-1997, ASP.1999.01, Archives of Scientific Philosophy, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Before assessing the content, I began by examining the document itself. The first half of the manuscript is mainly typewritten. In the second half of this document are what appear to be Hempel’s notes for the lecture, mainly made using a black ink pen; however, visible changes and edits were made with a pencil. It looks as if the document were written in a journal notebook, from both the size of the writing and comparing it to the typewritten pages. His handwriting on these notes is significantly more legible than other notes available at the archive under Hempel’s name, which made me think someone else was probably supposed to read this – possibly for more edits.

(Above) Page 1, typed, Logical Empiricism: It’s Problems and It’s Changes by Carl G. Hempel, Box 57, Folder 7, Carl Gustav Hempel Papers, 1903-1997, ASP.1999.01, Archives of Scientific Philosophy, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

(Above) Page 2, notes. Logical Empiricism: It’s Problems and It’s Changes by Carl G. Hempel, Box 57, Folder 7, Carl Gustav Hempel Papers, 1903-1997, ASP.1999.01, Archives of Scientific Philosophy, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Another thing I found interesting was Hempel’s remarks on the second page in the handwritten journal. They stated, “I remember my teachers with great respect and gratitude, but in the course of time, I have found certain difficulties in their ideas” (Hempel, 1981). Hempel then omits this from the revised text. I plan to delve deeper into Hempel’s correspondence to see which teachers he may be referring to and how he came to disagree with their ideas. I noticed other omissions between the two versions of the text, but they seem generic, as if he was refining his language for publishing this text.

(Above) Page 22, notes. Examples of generic corrections in the lecture. Logical Empiricism: It’s Problems and It’s Changes by Carl G. Hempel, Box 57, Folder 7, Carl Gustav Hempel Papers, 1903-1997, ASP.1999.01, Archives of Scientific Philosophy, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

I then turned my attention to the content of these versions of Hempel’s texts. My brief analysis helped me develop two insights, and additional research helped me begin to answer my questions about Hempel’s relation to China and Chinese philosophy. First, this manuscript helped me figure out what the Logical Empiricists and members of the Vienna Circle characterized ‘pseudoscience’. To my surprise, figuring out what separated scientific truth from metaphysics was an issue that logical empiricists, like Hempel, were thinking about back in the 1930s! They were concerned with verifications and considered any metaphysical statement meaningless.

Second, this manuscript provides evidence of who had influenced Hempel’s philosophy and who he may have had corresponded with. In Hempel’s lecture he mentioned a few recurring references to philosophers in Berlin and the Vienna Circle, such as Otto Neurath, Hans Reichenbach and Rudolph Carnap. However, the one that particularly interested me was “Professor Hung” – likely the same Hung from the first page!

As it turns out, I soon discovered that ‘Professor Hung’ was Tscha Hung, a Chinese Philosopher who was curious about logical empiricism and the foundations of truth (Cohen, 1996). This evidence provided an answer to my initial question: it seems Hempel was invited to China because Hung had an interest in Logical Empiricism and Western philosophy. Cohen (1996) mentions that he had heard of Hung while having a conversation with Marie Neurath Reading Hempel’s notes in the second half of this manuscript, I found Hempel’s account of meeting Professor Hung in Vienna. Apparently, Hung also attended the Vienna Circle meetings or one of the classes taught by either Moritz Schlick or Carnap. Hempel also mentions that the next encounter he had with Professor Hung was when he was giving a lecture in China 50 years later! Comparing the handwritten lecture and the revised version, I saw that Hempel had omitted this story about meeting Hung, which was surprising to me, considering that he was delivering this lecture in person, with Professor Hung in attendance. However, the final typewritten version might be an article he wrote, based on said lecture, so that may have led him to cut out all the informal sentences spoken at this lecture.

Works Cited

Cohen, R. S., Risto. Hilpinen, and Renzong. Qiu. “Realism and Anti-Realism in the Philosophy of Science : Beijing International Conference, 1992 ” Dordrecht ;: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1996.

Carl Gustav Hempel Papers, 1903-1997, ASP.1999.01, Archives of Scientific Philosophy, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atsumori 敦盛 (ca. 1897) from Nōgaku zue 能樂圖繪 in the Kōgyo: The Art of Noh Collection

This post was written by Maxwell Reiver, a recipient of an Archival Scholar Research Award for the 2021 Spring Semester.

Tsukioka Kōgyo, Atsumori 敦盛, ca. 1897, ukiyo-e 浮世絵 (Japanese color woodblock print), 243 x 363 mm, Tokyo: Daikokuya [Matsuki Heikichi]. From Kōgyo: The Art of Noh, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

This print depicts the moment of death for the shite 仕手(primary role) in Japanese playwright Zeami’s noh play Atsumori (ca. 1400). In this ashura noh 阿修羅能 (warrior category) play, Zeami creates a narrative adaptation to a battle that occurred during the 12th c. Genpei Civil War, between Taira Atsumori from the Heike (or Taira) clan, against a warrior from the Genji (or Minamoto) clan. In the story, Atsumori is killed by the warrior Kumagae, who goes on to become a Buddhist priest called Renshō to atone for having slayed this his youthful opponent.

Close up of Tsukioka Kōgyo, Atsumori 敦盛, ca. 1897, ukiyo-e 浮世絵 (Japanese color woodblock print), 243 x 363 mm, Tokyo: Daikokuya [Matsuki Heikichi] From Kōgyo: The Art of Noh, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Taking a closer look, this print expands upon a moment in Zeami’s script which invokes the image of birds taking flight through the noh text peeling back towards the viewer. Playing into the intertextuality of the Japanese literary cannon, this imagery pays homage to one of the early narrative versions of the Genpei Civil War, Heike Monogatari 平家物語 (Tale of the Heike), in which a captured Heike warrior is compared to a caged bird. As the dialogue in this scene makes reference to this motif of a caged bird briefly before Atsumori’s death, this image of circling birds in the corner of this print feels very appropriate, as Atsumori’s demise will permit him to take flight from this life, into the next, granting his soul another chance at life through reincarnation.

One of the other facets of the narrative echoed in this delicate imagery involves Atsumori’s youthful beauty and musical prowess at playing the flute. Like a singing bird, Atsumori’s harmonious music echoes through the bird motif, in a fleeting, miraculous panoply of beauty. The muted blue sky surrounding the birds stands in stark contrast to the white nōmen jūroku能面十六 (the Atsumori noh mask), promising transcendent clarity to the dying warrior’s soul.

Works Consulted

Brazell, Karen, ed. Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays. Columbia University Press, 1998.

Tsukioka Kōgyo, Kōgyo: The Art of Noh, 1869-1927. From the University of Pittsburgh Library System Archives & Special Collections. https://digital.library.pitt.edu/collection/k%C5%8Dgyo-tsukioka-art-noh (accessed February 5, 2021).

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fan Interactions: Then and Now

Professor Rachel Grozanick’s ENGLIT 0512 Narrative and Technology class visited Archives & Special Collections during the Spring 2020 term. Students had the opportunity to closely examine collections around the themes of constructing the canon, inclusivity, alternative formats, and fandom. Students examined artists’ books, comics, pop-up books, Modern Language Association editions, and Clifton Fadiman.

Today it is easier than ever to find and participate in communities centered around any niche media series or hobby imaginable, but that was not always the case. Before the age of the Internet, it was much harder for the earliest fans to connect and correspond with each other. One of the earliest ways these gaps were bridged was through the creation and limited publication of fan made magazines, often abbreviated to fanzines or simply zines. Small audiences developed around these independent projects, and over time the focuses of many of these once tiny and relatively unknown groups have grown to be parts of the mainstream consciousness. This growth is largely due to the widespread and increasingly accessible virtual communication platforms and social media. Despite the differences in format, platform, etc, there are striking similarities between old fan interactions in fanzines and modern fan interactions online.

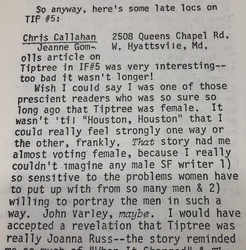

The lightning fast response times of internet forums today may be taken for granted now, but decades ago discussions around media and fandom depended on the postal systems to flourish. This is often lamented in The Invisible Fan #7, an issue of a zine containing a debate relating to feminism, inclusion, and the effectiveness of feminist groups comprised entirely of men, as the editor, Avedon Carol, occasionally mentions her annoyance with having to maintain and truncate an active mailing list along with the slow response time of those writing to respond to her (Carol 13, 21). These responses took the form of a "loc", or letter of comment, which subscribers would write in to the publishers or creators to give their thoughts on the topics discussed or the quality of the zines themselves (Southard 27). This particular issue of The Invisible Fan also contained a number of these referring to previous issues, which revolved around similar topics, specifically women and writing science fiction (Carol 18-19). This entire issue is almost like looking at a transcription of an internet forum discussion, especially in the case of the locs, as many of these have a bit of a dialogue between the fans and Carol.

Figure 1: An excerpt from one of the many locs from The Invisible Fan #7 (Carol 18).

While originally these dialogues consisted only of fans themselves, overtime industry professionals and creators began to get involved directly as well. This is not solely due to the rise in social media and instead has roots in zines themselves. In his book detailing the history of zines, New York University Gallatin Professor of Media and Culture Stephen Duncombe notes that science fiction zines were integral in pushing for more interactivity between fans and media producers, as well as between fans and other fans (Duncombe 114). Originally, fans simply wrote in letters with concerns or requests to the relevant publishers as well as to each other, and it was this active participation, Duncombe argues, that eventually allowed fans to play a part in shaping the final products as opposed to just consuming them (Duncombe 114). A more fully realized version of this relationship can be seen today with fans reaching out to companies and individual creators on social media platforms, where they can discuss their favorite franchises with the people responsible for them. Because some of these platforms have millions of users, in the past there have been instances where enough of them have formed collective pushes towards these companies to elicit changes they deem necessary. A recent example would be the delay of the movie Sonic the Hedgehog, as after initial trailers were uploaded fans were so outspoken in their dislike of the main character’s design that the movie’s release date was pushed back in order to update it. Clearly modern fandoms have a much larger impact than a handful of letters.

That isn’t to say that fans and zines never had any interactions with those working in the industries before the Internet. Another zine, Incognito, which was centered around Marvel and DC comics, published an issue that contains an interview between one of its editors, Rick Jones, and the late Marvel Comics Writer Stan Lee, who is responsible for many of the superheroes in mainstream culture today (Jones et al. 4). It’s more common now because it’s much easier to reach out to the people behind shows and movies directly. Creators and companies themselves have also taken steps to involve fans by hosting promotional question and answer sessions on Twitter or Reddit before upcoming releases, among other things. This, along with the added level of anonymity online usernames provide that may make others more comfortable in participating, ensures that discussions are open and available to everyone.

Some other avenues of fan discussion and discourse include the sharing of related pictures and fan made art. Because resources were often limited while making these zines, some took it upon themselves to recreate officially produced artwork via copying or tracing the official art as best they could, like in figure 2. Alternatively, some took to creating their own original artwork instead of or in addition to tracing. In the current year, we still often circulate and share images or memes of our favorite shows, and it's never been easier to find high resolution reference material, images or otherwise, via Google or similar search engines.

Figure 2: Doctor Strange characters traced by Bill Schelly in order to provide simple visual aids (Jones et al. 9).

What may be lost today, however, is the amateurish charm of yesteryear due to the advances and availability of better tools and technology. Both The Invisible Fan and Incognito contain some sort of spelling errors or printing errors, which can be seen in figure 3. While this may hurt any professionalism they may have aspired for, it could also be argued these mistakes add to the charm, as these projects were usually the work of small but dedicated teams or even single individuals. They might not be incredibly polished, but the passion shines through regardless. Currently, with the prominence of word processors with automated spell checking software, unintentional spelling mistakes are almost always seen negatively due to how easy they are to fix. This luxury was not a feature of the typewriters the original zines were written on. There is also a seemingly endless supply of such high quality fan art now due to the increasing availability of professional software. That doesn’t mean that the artists and fans of today don't have the same levels of dedication as those in the past. In fact, as these fan made pieces grew in elaboration, the time and technical skill required to produce them grew as well. Regardless, these works are still shared far and wide with others, but through the Internet instead of the mail or in person.

Figure 3: A particularly gruesome printing error. A spelling mistake is also visible in the top right corner (Carol 5).

The fans of today are still largely doing what the original fans accomplished through their zines decades ago except now there’s a much wider audience. The large communities of today are so expansive that the feeling of being a part of a small, tight-knit group might be lost. For example, it would be impossible to know every single individual personally today, due to some communities being so expansive they encapsulate millions worldwide. What may have felt like a special and even exclusive club back then now has the door bolted open for anyone and everyone to participate in. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, and in fact on the whole it’s more beneficial for those who want to get involved and participate. It's now possible for everyone to be an active participant, fan content producer, or just an observer, in the current cultural climate. The activities are largely the same, it's simply the avenues of distribution and communication that have changed.

- Derek Halbedl, undergraduate, University of Pittsburgh

Works Cited

Carol, Avedon. “The Invisible Fan.” The Invisible Fan, 1978, pp. 1–21.

Duncombe, Stephen. Notes from underground: Zines and the politics of alternative culture. Microcosm Publishing, 2014, pp. 114

Jones, Rick, and Billy Schelly. “Incognito.” Incognito, Sept. 1965, pp. 1–17.

Southard, Bruce. “The Language of Science-Fiction Fan Magazines.” American Speech, vol. 57, no. 1, 1982, pp. 19–31. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/455177. Accessed 2 Feb. 2020.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Psalmodia Vespertina by Philippus Baronus Aconitanus

This post was written by Emma-Leigh Jones, an intern from the Classics Department.

Continuing with my Latin internship at the Archives and Special Collections Department online, another work I have chosen to analyse is the Psalmodia Vespertina by Philippus Baronus Aconitanus. The Psalmodia Vespertina, or a collection of religious evening Psalms, is a musical work that was collected by Aconitanus and published in 1710. Not much is known about Philippus Baronus, or Filippo Baroni, other than that he was a composer of religious music in the 1700s. As I am myself a musician, analysing music from the 16th century has been challenging but intriguing; the way music is composed and written today is very different.

Translation: First Singer Part. Psalmodia Vespertina. For the whole year, to be sung together briefly by a twofold chorus. For the most illustrious and most reverend patron, John the Baptist, and Bussio. The second work by Filippo Baroni Aconitus.

As a 21st century violinist, I am used to reading music composed in treble clef:

However, the music I have analysed in the Psalmodia is written in a C-clef that I have never seen before. And the notes looked different from what I am used to seeing:

This clef can attach to any position on the staff, which makes it difficult to read because it can often change throughout the piece and does not stay consistent, unlike the modern treble clef. The middle line in the ladder chain represents the note middle C, so whichever staff line it is on or between would represent that note. In this picture, the middle staff line would represent C.

The first piece in the Psalmodia is a good demonstration of the function of this C-clef.

Translation: Lord hurry toward me who is to be assisted, Lord hurry toward me who is to be assisted, hurry toward me who is to be assisted. Glory to the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit. As it was in the beginning, and now, and always, and in ages of ages, amen amen amen amen.

As shown in the first piece in the Canto Primo part, or first singer (soprano) part, the clef jumps up on the last line of music. Having the clef so low on the staff in the first three lines would make it easier to notate the higher notes that the soprano part would use. I was curious to hear what this piece would sound like, so I transposed it into treble clef to make it more readable for modern musicians.

(Yes, it took several tries.)

Overall, I had a lot of fun analysing and transposing this 16th-century music, and I am glad I have more works from this time period to look at!

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice & Latin

This post was written by Lyonas Xu, an intern from the Classics Department

Recently, I have been wondering how many people are suffering from a miserable life like I do. Sleeping or staring at the ceiling to kill the time, while this coronavirus grounding everyone with a lethal excuse. Though I am physically restrained, my mind is free, daydreaming to wherever I wish. Speaking of daydreams, we all know the mistress of this specialty who unveiled a wondrous dreamland to the world—Alice, the most remarkable character designed by Lewis Carroll (or specifically, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson).

Alicia in Terra Mirabili, is the Latin translation of Alice in Wonderland. The first Latin version of this worldly renowned childhood’s book was translated by Canadian translator Clive Carruthers and published in 1964. It is not modern scholars’ first attempt to translate English classics into Latin, but this is definitely one of the most delightful ones. Just think about reviving both the wonderland characters and an ancient language—what a spark they light!

Beginning with the book cover (above), an exquisite illustration of the iconic figure in wonderland, the white rabbit, is embossed in golden color. I was captivated by the delicacy of the cover already, but the inner artworks are on another level. For example, the picture adjacent to the title page (right) depicts the courtroom in wonderland, with all sorts of living things. The appearances of the king and queen of hearts resemble their classic designs in the playing cards and the readers can even tell the “flatness” of the attendant’s garment at the bottom left.

Another notable setup is the end papers (left), which are printed with a mind-map of Alice’s adventure. Following the thread and starting with the upper right corner, there are “initium somnii” (the beginning of the dream), “cuniculi cavum” (the rabbit hole), “stagum lacrimarum” (the pool of tears) and so forth. Although the “index capitum” (right), the table of contents (distinct from the mind-map), is provided by Carruthers, I personally enjoy the game-board-like one, which is more playful as well as enables its readers to easily connect the Latin title and the picture aside.

I never expect quarantine to be interesting, but neither does it mean I will surrender to boredom. Surely, I can find great pleasure through spending time with Alicia and her terra mirabili!

Sources:

Carroll, Ludovici. Alicia in Terra Mirabili. Translated by Clive Harcourt Carruthers, St Martin’s Press, 1964.

Herald, Times. “Alicia in Terra Mirabili.” Washington Post, 16 October 1964, p. A20.

Schnur, Harry C.. Review of Alicia in Terra Mirabili, liber notissimus latine redditus ab eius fautore vetere gratoque, translated by Clive Harcourt Carruthers. The Classical Journal, May 1965, p. 378.

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cosmographia by Petrus Apianus

This post was written by Emma-Leigh Jones, an intern from the Classics Department.

In January I had the opportunity to start a Latin/Classics internship at the Archives and Special Collections Department in Hillman Library. Over these past few weeks, I have examined and translated a few pages of three works, one of those being the Cosmographia by Petrus Apianus and Gemma Frisius. Petrus Apianus, or Peter Apian, was a German humanist who worked at the University of Ingolstadt. Although he was called there to teach mathematics, he often neglected his teaching duties to study his own works. The university didn’t mind because they just wanted him for his name and reputation. Gemma Frisius was a Dutch physician and instrument maker. He invented and improved many mathematical instruments, like Gemma’s rings, or astronomical rings.

This older edition of the Cosmographia was printed in 1553. It includes many detailed pictures and pull-out maps, and also volvelles. A volvelle is a paper wheel chart that has strings or handles that rotate it. The word volvelle comes from the Latin word volvere which means to turn. When they were first introduced, many people thought that they were the work of black magic. They believed that they had “mystical origins” and that they could predict the future. To their credit, the volvelles did “predict the future” - by means of science. Although they were more widely used in the twentieth century, the origins of volvelles can be traced back as early as the year 1000. They have been argued to be the first origins of modern technology.

One of the volvelles featured in the Cosmographia is pictured above, labelled horae diei and horae noctis, “times of day” and “times of night.” It is used to figure out the positioning of the moon and the sun during different times of the year. Unfortunately, I am unable to move any of the parts of this volvelle because the paper is very fragile and has already been broken in. However, as you can see in the picture, the dirt marks on the handles show that many other people have enjoyed turning the wheels.

Another volvelle that is featured is this one above. From the labels, we can tell that this one was used to find the longitude of certain places. The use of a string has been implicated, and the cap in the middle with a face on it (I think it looks like a monkey, just my professional opinion) has been used to cover the knot. Covering the knot with an intricate design was a common practice in the making of volvelles.

Translations for labels: - organum praedictas propositiones declarans: “instrument declaring predicted propositions” - de longitudine Regionum, Provinciarum, Oppidorum, locorum’ve investiganda: “about the longitude of regions, provinces, towns, and places which are to be investigated”.

http://drc.usask.ca/projects/archbook/volvelles.php

89 notes

·

View notes