#scpittclasses

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Evolution of Cinderella

Last semester Jessica FitzPatrick’s class, Introduction to Critical Reading, visited Special Collections. The class took a closer look at serialized novels, fine press and private press books, and variances in editions published over time. Students had the opportunity to submit blog posts about their findings to Special Collections for extra credit:

These two versions of Cinderella provide hints as to the time in which the story was written or published. The first edition, by George Cruikshank, is a very small edition that is falling apart, as seen in Fig. 1. The second version is written by Charles Evans and that book is larger and in better condition, depicted in Fig 2. There are three factors in each edition that are telling of the time the books were written: the way the book was published, the language, and the nickname given to Cinderella.

Figure 1. George Cruickshank’s book, example illustration, pencil used to show relative size

Figure 2. Charles Evans’ book, example illustration, pencil used for relative size

Cruikshank’s book did not have a binding, the paper was only folded in the middle. In 1814, the printing press was used, but the machinery did not bind paper together, it simply printed words on the paper. The method used to put pictures on the paper was called “woodcutting.” It was a technique where a piece of wood acts as a stamp for paper in woodcutting. Knowing that the illustrations were not printed directly onto the page tells that it is an old copy, but the text coming from a printing press tells that it cannot be too old.

The illustrations in Evans’ book were done by Arthur Rackham, a renowned artist in the early 20th century. The technique for publishing in this case involved Rackham drawing a picture with pencil or ink, taking a photograph of the image, and having the photograph mechanically reproduced. This method portrayed how Evans’ book is a newer copy because of the improvements to photography. One can tell that this process was used because of the way the images are attached to the paper. The photos being reproduced required thick paper; they could not be printed on the same paper that the text was printed on. Instead, the images were printed on a thick paper and then pasted onto the pages with the text. In addition, the binding is strong and the book is still in good condition. The paper, illustrations, and condition of Evans’ book are indications of the book being published in more recent times.

Next I will discuss how the language in the books is a sign of the era it was written in. Cruikshank’s book uses words such as “thee” “thou” and “nay.” Reading these words, it is obvious that the book was not written in recent times because they are not used in modern language. These types of words were used in the Shakespearean era. The book was not published until 1814, but it could have been written years earlier when those words were still used. However, this type of language adds to the legacy of “Cinderella.” By reading the story in old fashioned words, I gained a deeper understanding of how much of a classic the story truly is. I knew that the story had been retold for hundreds of years, but reading this form emphasized just how long the story has been told. Of course, language has evolved and these words have disappeared from modern language. Evans’ book shows that evolution because the language in his book is more contemporary. It is the same language used today, so readers would know that it must have been written relatively recently. The language used in both editions hints at a time period in which it was written.

The last aspect of the story that relates to history is the nickname given to Cinderella. Her stepsisters always gave her a nickname that was supposed to be offensive. In Cruickshank’s edition, her stepsisters called Cinderella “Cinderbreech.” The oxford dictionary online gives an “archaic” definition that means “buttocks.” The name has lost its offensiveness because nobody today refers to a butt as a “breech.” The definition being defined as “archaic” provides even more evidence to how the nickname implies that it is an old version of the story. In Evans’ version, Cinderella was called “Cinder-slut.” At first, I was taken aback by the word choice considering it is a children’s book. However, then I hypothesized that Evans used slut to warn young girls of what not to do. Being promiscuous in the early 1900s was frowned upon and not socially acceptable for women. Then, women were more conservative than they are now and there were more expectations of a woman to be lady-like. Evans adding phrase “Cinder-slut” represents the societal norms in the early twentieth century, and how being conservative and “pure” was valued.

-Abby Markey, Freshman, University of Pittsburgh

Works Cited

Cruikshank, George. The Interesting Story of Cinderella and Her Glass Slipper. N.p.: Banbury, 1814. Print.

David Miles Books, The Interesting Story of Cinderella and Her Glass Slipper 2017. Web. 24 March 2017.

Evans, Charles. Cinderella. Norwood, London: Complete, 1919. Print.

Oxford Living Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2017. Web. 24 Mar. 2017.

"Style, Subjects, Technique, and Technology." Central Michigan University. Clarke Historical Library, n.d. Web. 24 Mar. 2017.

"1814 - 2014: 200 Years Steam-driven Cylinder Printing Press." What They Think. N.p., 1 Dec. 2014. Web. 24 Mar. 2017.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Function of a Book: Readers and Collectors

Special Collections welcomed Will Rhodes’ ENGLIT1125 Masterpieces of Renaissance Literature on Wednesday, March 15th. Students had the opportunity to examine facsimiles of Renaissance literature and poetry; fine press and private press editions of literature and poetry; and historical texts dating back to the Renaissance. Students worked closely with these materials and completed an in-class assignment to create a short essay. Professor Rhodes selected a handful of these essays for us to feature on the Special Collections Tumblr. We hope that you enjoy!

What is the purpose of a book? Well, to be read of course! But is that always true? While the contents of a book may never change, even down to the style of font it is published in in various editions, the purpose of the book may change. Special Collections houses many facsimiles, or exact copies, and modern editions of older books. I will compare one facsimile and one Renaissance book in order to show how a book is transformed from an object with a practical function to an object meant to be collected.

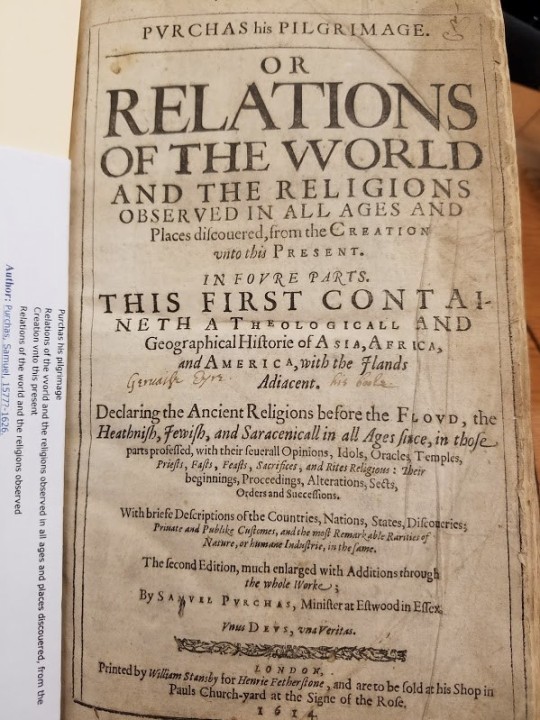

Purchas His Pilgrimage, or Relations of the World, Samuel Purchas, 1614

This book is an encyclopedic work, which describes various religions, their practices, and briefly about the nation from which they originate. Samuel Purchas was a well-educated Anglican priest, who, despite the extent of his works, never left England. In fact, he collected this knowledge from the stories of sailors and the manuscripts of past travelers. One might wonder why 17th century Christians would be interested in the traditions of other cultures. This is clearly answered on the title page.

Under the author’s name is the phrase “Unus Deus, Una Veritas,” meaning “One God, One Truth.” Therefore, these descriptions of other cultures represent what is false in the world. In an era where Europe is exploring and missioning to these places it would make sense to try and understand the culture of the native people. Purchas calls this his “pilgrimage.” This book therefore has a religious function. It is not a literal journey but a metaphoric journey around the world. The knowledge gained on this journey could allow others to better conduct their mission work in these countries.

But the book also functions to justify the growing authority of Christianity in these places. In one description of religious practice in China, the author writes that when people “obtain not their requests [to the Gods], they will whip and beat these Gods.” It is clear that these people do not understand the reverence and proper worship that Europeans do. This likely pleased, the Archbishop of Canterbury George Abbot, to whom the dedicatory epistle is written.

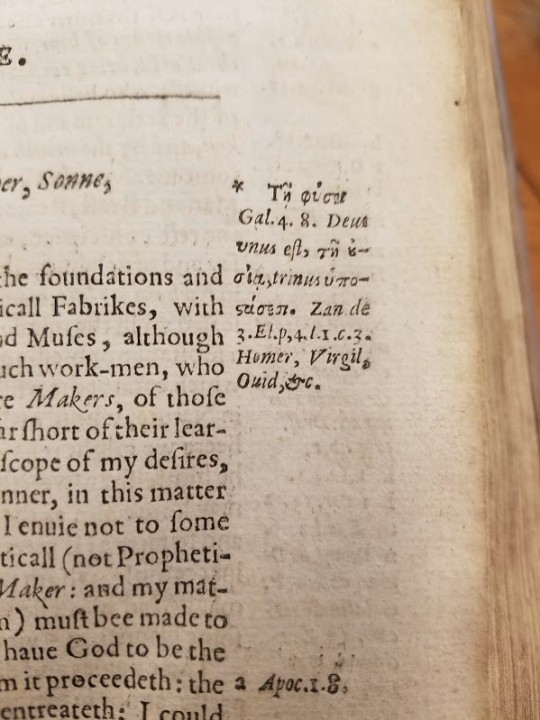

Another indication of its intended use by the clergy is the numerous printed notes in the margin. These often give evidence for what has been written or more avenues for research. The notes may be in Latin, Greek, or English, which implies the reader must have had the education to understand these annotations. The clergy would have learned Greek to read some of the oldest versions of the Bible and Latin for most church documents up until the reformation.

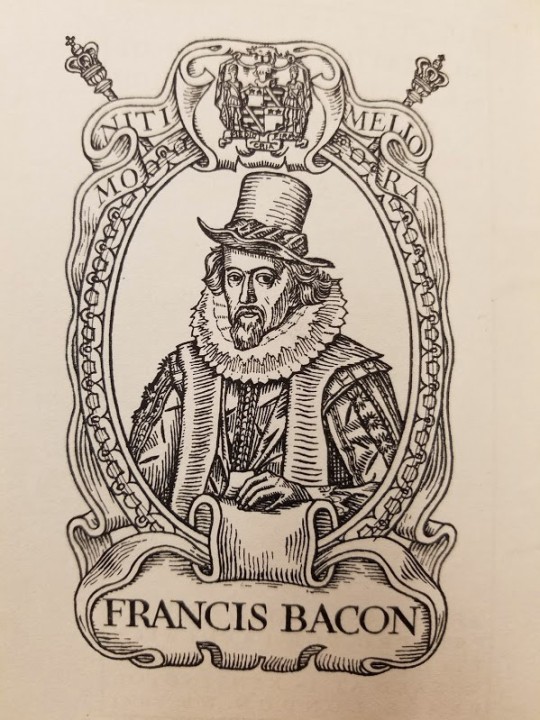

Essayes- Religious Meditations- Places of Perswasion and Disswasion, Francis Bacon, Originally Published 1597, Haslewood Edition: 1924

This collection of writings from philosopher and scientist Francis Bacon covers a wide variety of topics from a “regiment of health” to “atheism.” I am most interested in the middle text of the three works included in this book. It is called the “Meditationes Sacrae” or “Sacred Meditations.” This work is completely in Latin despite the other texts of this book being in English. Bacon must have had a sense that for anyone to take you seriously when writing about religious matters you had to write in Latin. In these short meditations he discusses common religious concerns such as the nature of Christ’s miracles and controversies between Church and scripture. This was likely regarded as a useful and edifying book in its time.

While one could make some interesting points about how Bacon’s logical scientific method influenced his religious beliefs, the fact that a facsimile was published more than three hundred years after it was originally published raises equally interesting ideas. While the book says it is an exact copy, “page for page and line for line,” of the first edition octavo this is not quite true. The note in the front of the book reveals that the outdated “f” has been replaced with the modern “s.” The frontispiece, shown above, is also redrawn from a different work of Bacon’s. It is also interesting that the editor’s note points out that this version is not the most well known, because Bacon continued to add to and edit these essays for many years.

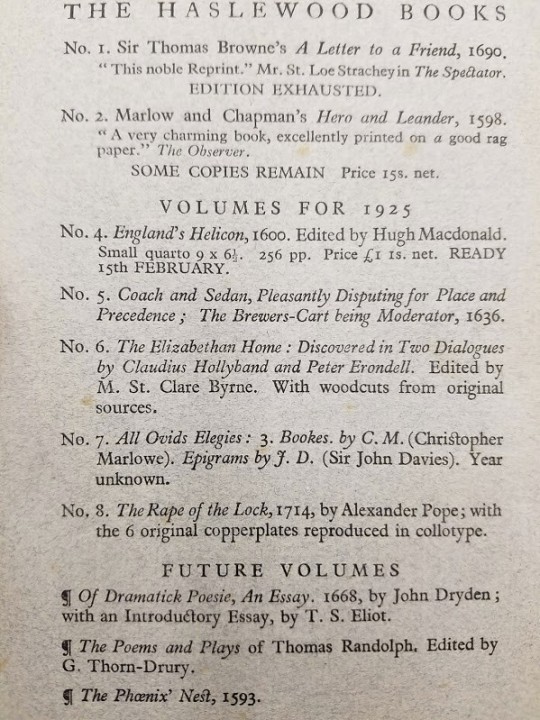

This book is neither the text that made it famous nor a totally accurate copy of the original so perhaps the purpose is not for it to be read but to be collected. Part of the challenge and fun of collecting is the rarity of the object. For instance, you could go to a comic book store and buy any new comic and there’s no challenge there. But if you want issue #134 of Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen to complete your collection of Jack Kirby comics it’s a lot harder. So the publisher has created this sort of challenge by limiting the number of copies printed. This book had a run of only 975 books.

Artist and architect Frederick Etchells founded Haslewood Press, the publisher of this book. This explains why this book is an object of aesthetic value. It was printed on all cotton paper with a deckled edge that gives the appearance of the paper being handmade. The top edge is gilt. It is these small details that make the book more beautiful almost to the point that it does not matter which classic work of literature it is. The back of this book is an advertisement for other books from this publisher. To promote the collecting of this series it announces that their copies of the first book have been “exhausted” and that only “some copies remain” of the second. Also interesting, is a review of one book, which describes the contents as “charming” but the printing to be “excellent” on “good rag paper.” A list of the upcoming books with their unique features is also included. These details further convey that in the case of these reprints, it seems more important to have a beautiful library of famous books than to be particularly invested in the contents of the book.

-Mark Connor, University of Pittsburgh undergraduate

#books#bookhistory#bookstudies#historyofthebook#bibliophile#bibliography#samuel purchas#religion#francis bacon#scpittclasses

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Professor Sreemoya Dasgupta “Childhood’s Books” recently visited Special Collections. The class worked with at a variety of children’s stories and how they were depicted across time and by various author’s/interpretations. Included was The Jungle Book, Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Peter Pan, and “Jack” stories. They analyzed the differences both within and among the texts by viewing first editions, fine press printings, pop-up style, abridged illustrated editions, and Disney editions. For extra credit, students had the option of submitting Tumblr posts, which we will feature throughout the week.

Peter Pan’s A.B.C is one of the many existing adaptations of the original story written by J.M Barrie. This adaptation was published by Hodder & Stoughton in 1913 which was two years after the original novel, Peter and Wendy, and nine years after the publishing of the original play, Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up. Interestingly, this novel is speculated to be unauthorized due to the lack of credit given to J.M Barrie on the cover and throughout the book. The ambiguity of this adaptation continues with the widely undocumented illustrator, Flora White, as well as the unknown identity of the author.

Unlike the largely black and white illustrations found in Peter and Wendy, Peter Pan’s A.B.C contains 24 fully colored illustrations. These illustrations not only help the young reader comprehend the story, but also aid children in learning the alphabet. White’s illustrations are viewed as indicative of perspectives of culture and the stereotypes surrounding characters such as pirates and native people in early 20th century London (i.e feathered head dresses and furs). While the target audience may be young readers, these detailed and often insightful illustrations are something that the adult reader can appreciate. The original novel structure of Peter and Wendy has been transformed into a brief narrative followed by short rhyming sequences that correspond with each of the alphabet letters and the 24 illustrations.

These rich images, large print text, and playful rhymes draw in a younger audience and also create a sense of enchantment for the adult reader. In fact, the wide appeal of this novel is indicated by the mark of ownership that is found in the front of this physical copy of the book. It appears to have been given to someone as a gift years ago.

-Lydia Belezos, sophomore

References:

Diab, Vanessa, Stephen Hanbury, and Tammy Leung. "Peter Pan's ABC: An Illustrated Alphabet." Project Gallery - Children's Literature Archive - Ryerson University. N.p., Fall 2010. Web. Nov. 2016. http://www.ryerson.ca/childrenslit/group8.html

"List of Works Based on Peter Pan." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. Nov. 2016.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Professor Sreemoya Dasgupta “Childhood’s Books” recently visited Special Collections. The class worked with at a variety of children’s stories and how they were depicted across time and by various author’s/interpretations. Included was The Jungle Book, Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Peter Pan, and “Jack” stories. They analyzed the differences both within and among the texts by viewing first editions, fine press printings, pop-up style, abridged illustrated editions, and Disney editions. For extra credit, students had the option of submitting Tumblr posts, which we will feature throughout the week.

I had seen the signs for Special Collections at Hillman Library multiple times, but had never been there until our class visit. I thoroughly enjoyed the experience of getting to see old relics of classic children’s texts. A text that I remember reading a lot when I was younger was The Wizard of Oz. I had read the book when I was a child and watched the movie many times; so seeing the different adaptations of the story was extremely interesting. My favorite version was the pop-up book with art by Robert Sabuda, even though it was one of the most contemporary, being published in 2000.

It was possibly the most intricate pop-book that I have ever seen. It was an extremely thick, large book even though it had at most ten pages. This is perfect for a child to be able to immerse themselves in. Once the book is opened, the pop-ups take over the pages. They are very large and intricate with pop-ups appearing on the main part of the page as well as smaller pages revealing the text. These pages have pop-ups on them as well. The entire book is extremely colorful and interactive with shiny materials on special aspects like the yellow brick road and emerald glasses for the reader to where when looking at the emerald city. The text itself still read like an abridged novel. The paragraphs of text would obviously be read by an adult while the child interacted with the pop-ups and listened to the story. Even though this was the most contemporary version of the text, it was extremely interesting to look at how a child would read it.

-Jessica Morris, junior

10 notes

·

View notes