#and like 90% of the people who i knew from there came out queer and neuro atypical

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

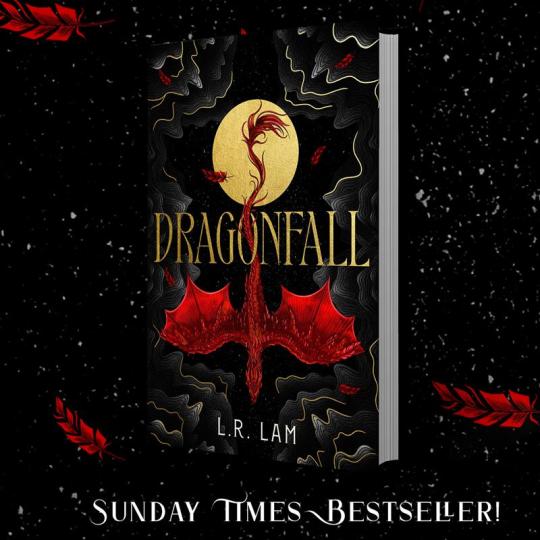

So I wrote this weird book about queer dragons. It came out the same day as the other dragon book everyone talks about. It was a Sunday Times bestseller in the UK, though, which was incredible!

However, I'm not sure how to continue to promote this book--people either seem to really like it, or not quite get it. Or it just wasn't what they expected. Which is fine, no book can please everyone, and I knew I'd made some unusual craft choices that was going to make it more marmite. (Or, as my brain tells me at midnight, I'm just a bad writer). However, there's that librarian saying "every book its reader" and the people who love this book REALLY love it, and that makes me so happy. So I decided to write this post and explain its weirdness and lay out what you can expect if you do pick it up. Maybe you're my kind of odd, too. :-)

Short pitch: 800 years ago, dragons and humans were bonded, then humans were dicks, stole the dragons' magic, and banished them to a dying world. But humans have short memories, forgot, and now worship dragons as gods. The dragon "gods" remember, and they do not forgive.

Thief Arcady steals their grandsire's stone seal (which helps them funnel magic) from their tomb. Their grandsire supposedly released a magical plague that killed a proportion of society, and Arcady is locked out of society as a result. They perform a spell to rewrite the seal to have a new identity as they want to go to university at the Citadel and also clear their family's name. Problem? The spell also accidentally calls through Everen, the last male dragon, trapped in human form. Everen has been foretold to save his kind, and now he has a chance: he just has to convince one little human to trust him mind, body, and soul, and then kill them. Then he'll be able to steal the human's magic back, rip a hole in the Veil, and the dragons can return. Good news for dragons, less good news for humans. As you might expect: this does not go to plan. Because emotions.

Grab it now. (Note: there's still a contractual delay so it's not available in US audiobook yet, annoyingly. Hopefully soon). (If you are like "weird queer dragons?! Sign me up" but aren't interested in hearing why the author has made certain decisions and want to go into the text cold, stop here! Death of the author/birth of the reader, etc. Otherwise, carry on.)

You should pick up Dragonfall if:

You like experimental narrative positions! It's all collected by an unnamed archivist who has access to both first person narratives (Arcady, the genderfluid human thief, Everen the hot dragon) and can scry into the past and draw out third person narratives (Sorin, hot priest assassin. Cassia, Everen's sister, who is also hot. Spoiler: everyone in this book is hot). Then to make it even weirder, Everen's bits are technically in first person direct address, so he's writing it all to Arcady (the first chapter ends with: "For that human was, of course, you. And this is our story, Arcady.") I ended up writing it this way for a few reasons, even though it probably would have been simpler to just stick to straight up third throughout, like most epic fantasy does. The big one is that Arcady is genderfluid and uses any pronouns (I tend to default to they when I talk about them outside of the text), and constantly gendering them in the text felt wrong whether I used he, she, or they. This way bypasses that a lot in the first volume, so it's up to the reader to make up their own mind. I also just really love first person direct address as a narrative position. It can be a little confronting, and it makes Everen the dragon sound a bit more predatory at the start. But it's also quite intimate. Is he writing his sections as an apology, or a love letter? Both? You find out at the end. So if your green flag books are: The Fifth Season, The Raven Tower, or Harrow the Ninth, this might also be your jam.

You love classic 90s fantasy. This is in many ways an homage to all the stuff I read growing up: Robin Hobb and the Realm of the Elderlings (the book is dedicated to Hobb in particular), the Dragonriders of Pern, Tad Williams, Lynn Flewelling, Robert Jordan, Mercedes Lackey, Tamora Pierce, etc. But I wanted to give it a more modern twist. I'm NB and growing up I didn't see a lot of queerness in fantasy, and I clung to the examples I did find (Vanyel, the Fool). Also, not 90s fantasy, but I also freaking loved Seraphina by Rachel Hartman and Priory of the Orange Tree, so those were influences too.

You're not put off by Worldbuilding(TM) and a slower pace. Probably because I grew up on the likes of Tad Williams, I honestly love slow-paced fantasy. I love to luxuriate in a world and take my time getting to know a made up world. In Assassin's Quest it takes over 100 pages for Fitz to leave the forest. Love it. I have a more lyrical writing style, I guess, and I'm pretty descriptive. My stuff always tends to start off slower, set the stage, and then ramps up the pace as we get further along. So yes, my book starts out with some infodumping, depending on your tolerance level of that sort of thing. I worked with a linguist and they made a conlang for the dragon language (hi @seumasofur). There's a map by Deven Rue (cartographer for Critical Role). I got nerdy.

You love queernorm fantasy! This is set in a world where it's considered rude to assume a stranger's gender and so you tend to default to they/them. If you consider someone much higher in status than you, you'd capitalise it to the honorific, such as They/Them. Once you get to know someone, you tend to flash your pronouns to them with a hand signal, since a sign language called Trade is also a lingua franca in the world. 99.95% of all the dragons are also lesbians, BTW. Everen is the last male dragon.

You like frankly silly levels of slow burn. Everen and Arcady can't physically touch without it causing Everen pain while they're half-bonded. They may or may not find creative loopholes. But it's not mega mega spicy, if you're expecting that. I expect the spice levels will gradually go up as the series progresses.

Alright, I think that's more than enough to give you a sense of what you'd find in Dragonfall. If you're open to sharing this post so it reaches more people outside of my little corner of the internet, I'd really appreciate it. Whenever I do any bit of self-promo, I'm always so anxious and worry it'll get like, 2 eyeballs on it anyway or that I'm just annoying people by mentioning that my art even exists. And if you end up liking it, please tell a friend.

I'm loving the recent dragon renaissance! Long live dragons.

#dragonfall#fantasy books#epic fantasy#fantasy romance#robin hobb#farseer trilogy#samantha shannon#the raven tower#priory of the orange tree#micah grey#pantomime#lr lam#laura lam#gay dragons#sexy dragons#I never know what to put in tags#post this before imposter syndrome makes me implode#lgbtqia#pride books#queer books#queer fantasy

294 notes

·

View notes

Text

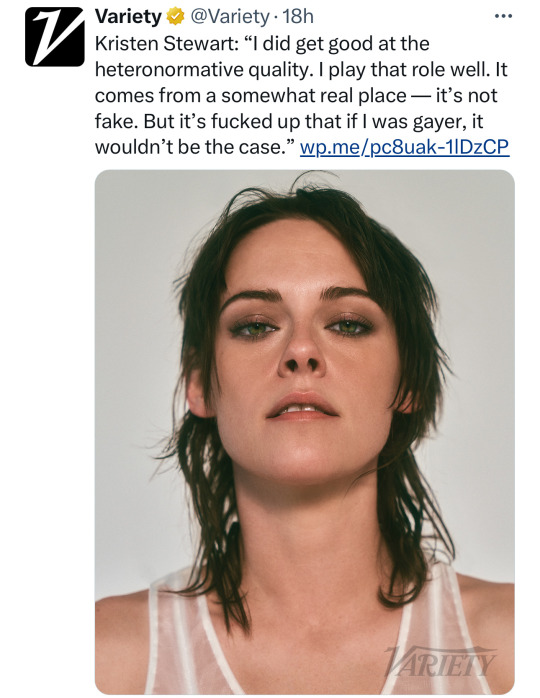

This was a very good article! I loved hearing Kristen’s (and Jodie Fosters) perspective as a queer trailblazer. Inserting some snippets below 🤍

To get to this point, Stewart’s weathered more than a decade of unrelenting media scrutiny, first about her straight relationships, then about her gay ones, as she figured out her own identity. She leveraged her global stardom from the “Twilight” franchise not to become a superhero or a lifestyle guru, but to fuel an astonishing run of acclaimed independent films, including “Clouds of Sils Maria,” “Still Alice,” “Certain Women,” “Personal Shopper” and the Princess Diana drama “Spencer,” for which she earned an Oscar nomination.

“Whenever I hear that she’s doing something new, I’m so curious to see what it is, because it’s going to be a movie that hasn’t been made before,” says Clea DuVall, who directed Stewart in one of her only Hollywood films during this period, Hulu’s 2020 release “Happiest Season,” the first lesbian Christmas rom-com backed by a major studio. “She really is so herself. And I think that’s why so many people respond to her the way they do — because she is so authentic.”

By the time Stewart stepped on the stage of “Saturday Night Live” in February 2017, she’d spent the previous two years trying to convince the press that it was OK to write about her relationships with women, rather than resort to the vexing practice of referring to her girlfriend as her “gal pal.”

“It wasn’t even like I was hiding,” she says. “I was so openly out with my girlfriend for years at that point. I’m like, ‘I’m a pretty knowable person.’”

But even with that posture, the media’s “gal pal” dog whistle triggered a deeper, more painful history of intrusive curiosity about Stewart’s sexual identity. “For so long, I was like, ‘Why are you trying to skewer me? Why are you trying to ruin my life? I’m a kid, and I don’t really know myself well enough yet,’” she says. “The idea of people going, ‘I knew that you were a little queer kid forever.’ I’m like, ‘Oh, yeah? Well, you should honestly have seen me fuck my first boyfriend.’”

It’s worth dwelling on this point: For almost the entire history of Hollywood, queer actors dreaded the public discovering who they really were, and that fear kept the closet door firmly closed. “Because I was gay, I really retreated,” says DuVall, who came out publicly in 2016. “Even doing a teeny tiny movie like [the ’90s lesbian cult favorite] ‘But I’m a Cheerleader,’ people immediately were like, ‘She’s gay, how can we out her?’ I wanted to stay small.”

Stewart, though, went big, with a monologue on “SNL” about how President Donald Trump, in 2012, obsessively tweeted about her relationship with Pattinson. “Donald, if you didn’t like me then, you’re really probably not going to like me now, because I’m hosting ‘SNL’ — and I’m, like, so gay, dude,” she said to wild cheers from the audience.

“It was cool to frame it in a funny context because it could say everything without having to sit down and do an interview,” Stewart says before running through the kind of questions queer actors have had to consider before coming out publicly: “‘So what platform is that going to be on? And who’s going to make money on that? And who’s going to be the person that broke it?’ I broke it, alone.”

A few days later, I mention Stewart’s “SNL” monologue to Foster over the phone, and she lets out a big laugh. “I never knew that,” she says. “What a wonderful, funny, wry, modern way to be honest to the world. That’s just awesome.”

As Stewart talks about her “SNL” experience, I think about how no stars of her age and stature ever came out when I was growing up as a gay kid in the 1980s and ’90s. So to have her professional trajectory not skip a beat feels like real progress.

When I tell her as much, she takes the conversation in an unexpected direction. “Because I’m an actor, I want people to like me, and I want certain parts,” she says. “I have lots of different experiences that shape who I am that are very, very far from binary. But I did get good at the heteronormative quality. I play that role well. It comes from a somewhat real place — it’s not fake. But it’s fucked up that if I was gayer, it wouldn’t be the case.”

I try to clarify what she means: “So your career maybe would have suffered after coming out had you not affected a performative femininity …”

“… that I know works to my advantage,” she admits, nodding. “That’s why I’m fucking stoked about ‘Love Lies Bleeding.’”

Stewart didn’t let that scandal, as intense as it was in the moment, stifle her. Instead, she grew to fully embrace her queerness in her public life — like bringing her girlfriend, screenwriter Dylan Meyer, to the Oscars in 2022. “It’s not that I wasn’t scared,” Stewart says. “It was just that there was no other way to live.”

She’s even started to recognize that the most ostensibly heterosexual thing she’s done, “Twilight,” has its own queer sparkle. “I can only see it now,” she says. “I don’t think it necessarily started off that way, but I also think that the fact that I was there at all, it was percolating. It’s such a gay movie. I mean, Jesus Christ, Taylor [Lautner] and Rob and me, and it’s so hidden and not OK. I mean, a Mormon woman wrote this book. It’s all about oppression, about wanting what’s going to destroy you. That’s a very Gothic, gay inclination that I love.”

I ask Stewart if she understands how much her decision to come out has also made her a role model for LGBTQ people. She cackles. “Oh, you have no idea,” she says. “Every single woman that I’ve ever met in my whole life who ever kissed a girl in college is like, ‘Yeah, I mean, me too.’ I’m constantly joking with my girlfriend. I’ll be sitting there and be like” — she whispers — “‘She’s gay too. Everyone’s gay.’”

It can be easy to forget just how rare this still is, a giant movie star living such an openly queer life. “It feels like a generational thing, where I’m watching somebody make the leaps that I didn’t think I could ever do,” Foster says.

After fiercely guarding her privacy for decades, Foster came out publicly at the 2013 Golden Globes, and has just now played her first explicitly gay character in the 2023 biopic “Nyad.” Talking about Stewart has put Foster in a reflective mood. As our call is coming to an end, she offers this unprompted insight: “I get a lot of questions about who I was and what I represented in the industry, and was I — I don’t know …” She exhales. “Was I helpful in terms of representation? I’m sure there’s a 12- or 13- or 14-year-old when I was making movies as a young person who said that I had something to offer to them in their life as a queer person. I had to do it my way. I had pioneers to help the way, who I’m grateful for. And now people can be grateful for Kristen for being the pioneer. I’m just — I’m grateful to her.”

This sense of communion with the wider LGBTQ tribe is why Stewart has dedicated herself to embracing the fullness of who she is as a bro-y, butch-y queer woman in her work as an actor and, come hell or high water, a director.

“I was like, ‘I would like to be on that team because we need each other,’” Stewart says. “I didn’t want to be left out anymore. It was this whole world that I didn’t realize I could explore.”

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bengiyo's Queer Media Syllabus

For those who are not aware, I have decided to run the gauntlet of @bengiyo’s Queer Cinema Syllabus and have officially started Unit 1: Coming of Age Post Moonlight. The films in Unit 1 are Pariah (2011), Get Real (1998), Edge of Seventeen (1998), My Own Private Idaho (1991), and Mysterious Skin (2004)

Today I will be writing about:

Edge of Seventeen (1998) dir. David Moreton

[Available on: Kanopy, Archive, Amazon, Run Time: 1:44]

Summary: A teenager copes with his sexuality on the last day of school in 1984. It shows him coping with being gay and being with friends. (from IMDB)

Cast: Chris Stafford as Eric, the main character Tina Holmes as Maggie, Eric’s best friend/girlfriend-ish? Anderson Gabrych as Rod, Eric’s gay awakening Lea DeLaria as Angie, former work supervisor of Eric, Maggie, and Rod at their summer job.

__

I had some firsts with this film. This was the first film in the syllabus that had identifiable tropes that carry through some of the BLs, which makes sense as this syllabus was designed as a progression in to BL. But most importantly, this was the first film in the syllabus that made me truly understand how important it was for me to work my way through these films, and that comes down to the surrounding conversation I had with @bengiyo and @shortpplfedup, when I expressed absolute shock and awe that a film from 1998 had two men shoving their tongues down each other’s throats, mouthing at penises through pants, massaging bare asses on screen, mentioning/simulating rimming, showing and actually using lube.

I decided to work my way through this syllabus because growing up I a) didn’t know I was queer or at the very least b) did not admit to myself I was queer, c) did not have any out queer people in my family and d) did not have any our queer elders in my surrounding life. Therefore every single piece of queer cinema or television that I consumed was something that I just happened to stumble across, or that I had potentially seen someone post about on tumblr. Thus, there is a wealth of queer cinema that I never knew existed.

In the past few years I have reflected a lot on how little history I know about my community. I have thought about lines in The Inheritance play where older gay men are discussing how baby gays just Simply Do Not Understand but also how they don’t know the names of important and influential people in the community, we may all know Stonewall, but honestly until a year or so ago I could not name a single other important moment in US queer history. I don’t like how much I am missing because I didn’t know myself and didn’t have anyone around to learn it from.

All of this to say, I wanted to watch more queer cinema because I didn’t know what was out there, and in doing so I have realized how important it is to me to see these glimpses of history in what was allowed, acceptable, tolerated, made visible, and the level to which queer characters were humanized and treated with empathy and compassion.

Anyway, I was watching this film and DMing Ben and Nini about it and when I expressed surprise that they were going this far in a film from over 20 years ago, they said the following (independent of each other):

“I realize you came of age after 9/11, but you truly have no idea how hard this nation regressed”

“Ah the halcyon days of the 90’s before the weird post-911 puritanical backlash”

So, naturally a conversation begun around society, art, and culture and how it change between the 90s and 2000s (@shortpplfedup). How military service and gay marriage were compromises compared to what queer people were pushing for before 9-11 (@bengiyo). And that is when I was struck with the understanding that I needed to go through this syllabus. For the sake of understanding what art and culture and queerness was like before 9-11. For the sake of understanding just how far film and television have regressed in the US when it comes to queerness and how it is portrayed, how frequently, and in what contexts in film and television.

And there are little moments in this film that I see nodding to queer history, the most visually striking one for me being the shot of the back of a record holder that had a pink triangle as its design. That feels extremely intentional to me.

It is also the first film in the syllabus I’ve seen that contains trends/tropes utilized in BL. First being where a boy, left unattended, grabs the nearest article of his crush’s clothing and smells it. The way the enter the final sex scene in this film by focusing initially on the feet, which I have seen done a number of times in the BLs that I have watched (l just finished You’re My Sky today and they imply sex through foot position, you can see it in the trailer for Only Friends as well). But unlike most of the BLs, I’ve watched that utilize that imagery due to rating requirements or censorship, THE CAMERA KEEPS GOING and you’ve got bare, hairy asses, all the hip you could possibly want, and two men practically eating each other’s faces. I see so many echos of Teh and Tarn’s relationship to one another reflected in the dynamic between Eric and Maggie.

I guess I don’t have much else say about the film itself except that it is very clearly created by people who are queer, who get it, who understand what Rod is saying when he says he likes Madonna, how you can immediately tell that Eric is going to a gay club when he pulls up to the parking lot of Universal Fruits and Nuts. The way the exterior of that building feels very different from what is inside, and made me think a bit about speakeasies. The shirt Eric wears when he comes out being a disassembled, abstracted face, his brother wearing a That’s The American Way t-shirt. You know what the film is trying to tell us about Eric’s identity based on which female musical artists he has on his wall.

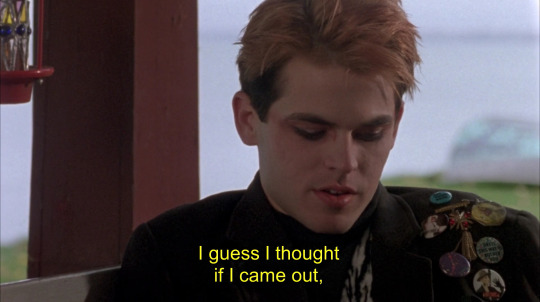

Like the other two films I have seen in Unit 1, the ending of the film is the most striking, lingering part for me. Eric comes out to his mother in the following exchange:

Eric says “I’m gay” \\ in the quietest voice she has, his mother says “I know” Eric and his mother hug* and she asks him“What did I do wrong?” she lets go and moves to the other end of the living room \\ Eric looks devastated says* “I love you” \\ she turns to look at him and says “I don’t know how to handle this”.

In that initial “I’m gay” \\ “I know” exchange be followed by a nice, warm hug, there was a spark of hope in me that this would be a coming out that his parent would handle gracefully (despite the other moments in the film where she starts to suspect and question him). I thought for the briefest of seconds that her question “What did I do wrong?” was her asking Eric how she had misstepped in ways that he was worried about coming out to her. But in about the same amount of time that it took for Eric to process the question, I realized a much deeper, more painful thread was being called to the surface: “What did I do wrong [to make you gay?]”

This feels like an admission a la Mol in 180 Degrees, telling Wang that she is, in fact, disappointed that he is gay. And you can see the way it impacts Eric. And silly me, I should never for a second thought that this coming out might go over flawlessly, because this story and parts of gay culture and gay sex that are included in this film indicate to me there are queer people behind the story. Which means the way that Eric’s mother handles the coming out is so much more likely to be realistic. Parent and child both confirming that they love each other, but their child still being hurt by their parent’s inability to understand and figure out how to handle new information like that spoke directly to how the conversation between me and my mother went when I came out.

But even more important to me than that scene, than the complexity that comes from loving someone and not knowing how to reconcile love and homophobia, is that life goes on. Eric leaves the house, and ends up back at the gay club, surrounded by queer elders, seeing a boy he has a crush on, and smiling and enjoying himself with his community while he listens to his friend sing the words “nothing but blue skies from now on”. Which just feels…idk, so goddamn real? Carrying the pain of rejection with you but being determined to find joy in the people who accept you, despite how much the rejection may hurt.

I place this film in the by, for, about category

In general, I would have given this show an 8.5/10, but with the inclusion of poppers, blow jobs, rimming, use of condoms, and the first fucking inclusion of lube in any gay sex scenes I’ve ever seen on screen, I’m bumping it up to a 9.

Favorite Moment:

The Redi-Whip can spraying in Eric's hand after Rod says something out of pocket.

Favorite Quote:

Eric: “I guess I thought if I came out, everything would get easier”

Angie: *immediately bursts out laughing*

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red, White, & Royal Blue Movie Rant

Spoilers. All the spoilers. You've been warned.

I'm going to be talking pretty negatively about the movie, and if you don't want that, please, please scroll. I'm not trying to rain on anyone's parade. I know how important this movie is to a lot of people and the last thing I want is to upset anyone with my opinions. I just need to get my thoughts down. I'm a list autistic (yes, ha, like Alex).

My ramblings about this are not in any way meant to take away the importance of this movie. It is sacred in a way to a lot of people, the same way Harry Potter was when it came out (fuck JKR). It makes people feel seen despite how good or bad it is and that is important. This is my opinion on this piece of media as just a movie, as a thing. NOT as a concept that is good and needed and unashamed. I really hope this is the beginning of more feel-good queer movies. As a queer person, as an American in a time of trans-bills who is dating a trans person, this movie is powerful. But like, also bad. And I have opinions on it.

So, I didn't like the movie. The mixture of the promos, the R rating, and the 90% it had on Rotten Tomatoes before it came out definitely got my hopes up. And I love the book. But in the end, I don't like the movie. I wasn't expecting something worthy of awards and critical acclaim, but I was expecting something more.

I think the reason I can say I didn't like the movie and not something more along the lines of, "I enjoyed it despite its problems," is because of how many issues I have with it. If it was just pacing, or just the cheesiness, or just an actor I think I would have liked it. But I pretty constantly went, "Oh, I don't like that." And the issues just kept stacking.

Going into it, I knew the main differences from the book were the lack of June and the fact Ellen and Oscar weren't divorced. And I think those two huge elements that play a part in Alex's character are really apparent in the movie. I thought Alex was kind of flat. I thought a lot of the characters were kind of flat. And this one is going to piss a lot of people off, but I didn't like Nicholas Galitzine's acting at all. I think the moment the movie went from enjoyably bad to bad bad for me is the last third where it's from Henry's perspective. The scene where he started browsing the books in the red room like that was particularly awkward and stilted. A lot of his scenes felt like that, like he was acting for a play or something. It wasn’t realistic. Since he’s a main character, it really did affect my opinion of the movie as a whole.

Amy and Zarah were amazing. And Stephen Fry as the King did a great job. Taylor Zakhar Perez’s acting was on point, most of the time. I think some of my favorite scenes were Alex interacting with his mom, Zarah, Amy, and Nora at the beginning of the movie. Also, I fucking loved Nora. I wish she had been in the movie more, and also explicitly bisexual. And Pez. I just really wanted Nora/June/Pez, but I digress, not having that is not what made the movie unenjoyable for me.

I tried not to compare it to the book as a way to determine how good or bad it was. Like, when I heard June wasn't a character, I didn't immediately go, "Well, that means it going to be bad." But one of the great things about the book is the way all the characters interact with each other, not just Alex and Henry. We get to see what kind of relationship Alex and June have with their mom as their mom and as the president. We get to see the White House Trio be goofy but genius young adults figuring themselves out. Those were the moments that flesh the characters out and make you care about them. And there just really wasn’t very much of that in the movie.

The R rating made me happy, for one, because Alex says “fuck” so much in the books. His potty mouth is commented on. It is part of his character. It’s such an easy way to portray this very genuine and good character as someone who is still brash and a bit of an asshole. I had also hoped that the rating would help it feel like the book (says the person desperately trying not to compare it to the book). It is supposed to be sexy and fun on top of being unapologetically queer. But on the flip side, that was such a PG-13 movie and I have a feeling whoever decides the rating of movies was being homophobic. Because a gay sex scene is more “inappropriate” than a straight one. I also associate a level of maturity with R-rated movies, not because of more mature content but because the people consuming the movie and the movie itself should appeal to a more mature audience. If that makes sense. But it felt like a Hallmark and Disney’s ever so slightly more raunchy lovechild.

The pacing immediately took me out of the movie. It was like watching a movie on 2x speed. I totally get why so many people thought it should be a mini-series or something. And I know they couldn't fit all 400 pages into a movie, but there have been adaptations before that do a solid job. I don't think RWRB did. I feel like Alex’s character development was flat and a bit magical—unnatural and unearned. Like, Henry apologizes and suddenly they are BFFs.

AND THE EMAILS. That’s what the whole ending conflict and it felt very much forgotten. We got the text messages and stuff, but when it came to the emails, it was just voiceovers. I think, like in the book where Alex thinks about private email servers (which is like my favorite joke in the book, it’s so layered in so many ways), there needed to be the equivalent of that in the movie before to bring attention to it. But this catalyst just kind of gets overlooked until it’s relevant.

And motherfucking Miguel Ramos. He felt like just a juvenile addition by being into Alex and being big bad because he’s into Alex. It was kind of icky in a way the book avoided. In the book, it was about politics, and while icky, they didn’t use a queer character to achieve the big conflict. His character, and really the whole progression, reminded me a lot of fanfiction written by a new writer. Like, the concept is good but the execution is what holds it back.

Okay, so, I for sure have more things I disliked than things I liked, but I did appreciate the humor. It was the one part that 100% felt like the book. It was stupid and inappropriate, but witty and compelling. The direct quotes had me fangirling. Zarah, Amy, and Nora. Just ugh. I’m gay. Shaan? I also miss his sweet ass.

I didn’t expect this movie to be perfect but I would be lying if I said I wasn’t disappointed. I’ll try watching it again when I’m not in hyperfixation mode. Thanks for coming to my TED talk.

EDIT: Also, Alex confirmed their relationship in the speech BEFORE the talk with the king. Like, Sir King Stephen Fry, it's already out there, man. The speech was supposed to take place after their talk with Philip and the King.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is probably going to be long

OK, I lived through the AIDS crisis. I was a young person questioning my sexuality at arguably the worst possible time in American history. I discovered the word "bisexual" (hooray I have a label) only to read a few days later in mainstream news about how "bisexuals were responsible for spreading AIDS to the hetero community" which was a take that was tolerated on national news shows at the time. The only sex education I had in my entire public education was a film we were forced to watch about how you could get AIDS from french kissing (you can't) and heavy petting (which we didn't know what it was because it was outdated old people code for oral lol)...

The entire LGBTQIA plus community was not attacked as a monolith, the focus of hate came on gay men, because they were the most obviously effected and also the most visible and prominent in the community. The rest of the community did their best to embrace and protect them. (For example lesbian groups that were on the front lines of caring for people who were sick when no one else would...).

And there were people like myself who identified as allies but were in a place where they didn't feel safe to come out themselves. I did not come out at that time because even though I was in accepting local community at University and working at a feminist journal I knew I would lose friends and family and possibly future work opportunities. Being Bi it was easier to blend in for me and I took advantage of that. Part of the reason I hesitated so long about coming out was I felt a lot of guilt that I didn't come out in the 90s during the AIDS crisis. I felt like a coward who wasn't worthy to stand with such brave people.

It took me a long time to let go of that self-hate to the point where I could come out. A big part of it was acknowledging how fucked up the climate for LGBTQIA folks in the 80s and 90s. We had two family friends (which is how I knew I would probably be rejected by a lot of my family) who died of AIDS. Yes, these were brilliant, creative men who worked in theater. One of them was the props coordinator for Late Night with David Letterman (responsible for building Dave's velcro suit etc.). I also have a peer who died of AIDS in the early 2000s, long after the disease had supposedly been "not a death sentence" who also happened to be an actor.

Despite their lack of political involvement, they were be seen as radical just because they lived openly as gay men in a society that hated them and wanted them dead, and only tolerated them if they were the "fun gays" who weren't actually threatening the status quo...

Being in theater or the arts was a survival tactic for a lot of people ya know because it was a more accepting environment and because it wasn't considered important like politics, medicine, science etc. (Miss me with the gays can't do math jokes. A gay man invented the fucking computer).

The gay men I knew in long-term monogamous relationships survived the worst of the crisis and they automatically became "respectability queers" for having not died and wanting jobs with health insurance etc. Because one dude follows his dream of working in theater and the other quits theater and goes to work at the phone company and buys a house with his partner, one is fun and the other boring? One is a creative genius creating culture and the other is a consumer of cultural pap? Wow. Great take.

FUCK. I'm just getting so angry thinking about this. You want to know why it took me till I was FIFTY fucking years old to come out: AIDS. That's it. ONE Fucking word.

Sorry I have no idea WHY I fucking started this other than I saw a shitty post that said, our culture became boring because all the fun gays died and left only the boring gays who only care about marriage or whatever.

#Also: what the fuck is wrong with CATS and ghostbusters???#both are great#both have their value#if you want to bitch about marvel or shitty broadway musicals then do it#please don't throw all the old gays under the bus for being boring while you do it#also there was that post yesterday about Anthony Perkins and I did not realize he died of AIDS#I don't know how I missed it...oh it happened in 1992 when I wasn't living at home and didn't have a tv...#sometimes the sex positive bubble of tumblr will prefer the LOLZ lifetime achievment of fucking take#over the he was conflicted because all of society hated him for being gay and many many shitty people rejoiced I'm sure when he died take#as they did when other prominent gay men died of AIDS#PS: those are the same people trying to pass legislation attacking trans people#the same fucking people

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Kevin Ray

Published: Jan 23, 2024

Prologue: Navigating Cultural Revolution

I’m days away from starting rehearsals for my third literary adaptation as a theater director; my heart is pounding with excitement and fear. There’s nothing more thrilling than the electricity of a vibrant rehearsal room full of talented, generous, creative actors and designers, collaborating with me to adapt literature into a play, but it’s also anxiety-producing because there are a million creative decisions to make. Nonetheless, the theater is booked and the curtain will rise in October 2024; the only thing to do is persist in the pursuit of making great theater.

The inspiration for this production—an adaptation of a 1924 dystopian novel by Russian heretic Yevgeny Zamyatin—arose from my experience, not in creative persistence, but persisting in the face of an ideology that endeavors to bar heretics like me from the arts.

A culture of the arts without heretics isn’t a healthy culture—it's a boring culture. Regrettably, a small but very loud group of activists in the theater have sidelined heretics by demanding artists conform to an identity-grievance fueled monoculture.

Fortunately, I found a way to make theater. I feared I’d be forced out of the field altogether. I lost work for refusing to promote concepts such as “White Supremacy Culture” and “Decolonization,” I infuriated some by refusing to adopt “gender-neutral pronouns,” and I faced disdain for being white, male, and even for identifying as gay and not “queer.”

Unfortunately, I was prepared to deal with identity-based discrimination—I’ve faced prejudice since the beginning of my career.

Act I: The Wrath of Westboro

I was drawn to theater from a young age, partly because theater groups were welcoming to oddballs, weirdos and outcasts who didn’t fit in elsewhere. Even before it was clear to me, my classmates knew I was gay, and I silently endured daily bullying. Theater was an oasis where I could get away from demeaning comments and fit in with other kids. I relished using my imagination to stand in the shoes of a character who was not me; facing obstacles in a different time and place.

By the late 1990’s I was acting, singing and dancing in a professional production of a musical that toured small and mid-sized cities across the United States. Getting paid to tour in that musical was the epitome of a “dream come true.”

I was lucky to be in that show for various reasons. First, the production held auditions in New York, a city overflowing with talented performers. Being cast in that show was, as they say, “a lucky break.” But this was not the first break I had had in my life.

When I was eight years old, I had a break of a different kind: I broke my neck. The two vertebrae just below my skull were fractured. A neurosurgeon told my mother and me it was rare to see someone with this injury still alive, most people died instantly; the few who lived were permanently paralyzed. After the neurosurgeon explained the procedure he would perform, he looked directly into my eyes and said, “If there is anything you want to do in your life, you should do it before this surgery.” I said I wanted to have another birthday.

I survived; and at twenty-six, I was dancing across stages around the country. More than lucky, that was miraculous.

The last bit of luck I had was the date of my birth. If I had been born a few years earlier, I may not have lived to see my twenty-sixth year. The generation of gay men who came just before me were ravaged by HIV/AIDS. As reported, “by 1995 one American gay man in nine was diagnosed with AIDS.” The epidemic also spawned an anti-gay activist movement.

Enter stage left: the Westboro Baptist Church. Founded by Fred Phelps in 1955, the church gained notoriety in the early 90’s for picketing a park frequented by gay men. As reported, they also “picketed at American soldiers’ funerals, thanking God for killing those who’d fought for a country that ‘institutionalized sin.’ They prayed God would kill Westboro’s enemies.” The musical I was in prominently featured gay male characters, making it a prime target for Westboro’s bigoted activism.

As our tour bus pulled into the parking lot of a Kansas theater, church members stood outside holding signs that read “God Hates Fags” and “Two Gay Rights: AIDS and Hell.” Many in the cast were gay, but to the Westboro protestors we were not three-dimensional human beings with the capacity to love, dream and hate, just like them. They didn’t care about the commitment we had to our craft, the challenges everyone overcame to be cast in the show, and that, at the end of the day, we were all performing in the musical because of our love for theater. The point of identity-grievance activism is to ignore our common humanity and weaponize identity.

The protesters were within their legal right to peacefully hold signs with heinous language. Considering the musical highlighted how difficult the lives of gay men can be because of the discrimination they face, I wonder if Westboro’s activism only deepened the meaning of our show: as they walked past the signs, that audience experienced, first-hand, the ignorant vitriol many gay men encounter.

I was afraid that night, but I did what I had to do: I went on with the show; Westboro didn’t stop me from living my dream.

Despite fringe groups like Westboro, the late 1990’s was a time of great advances for gay men. As the country headed toward a new century, society was becoming more welcoming to a wide variety of minority populations. How could any of us have predicted the identity-grievance nightmare that was to come, and the impact it would have on the theater?

Act II: A New Dream

When actors aren’t working in a show, they survive by holding down a “day job.” Around 2002, I stumbled into a day job as a Teaching Artist. Teaching Artists visit schools on behalf of cultural institutions (theaters, dance companies, orchestras etc.) delivering arts programming, often in under-funded districts that don’t have budgets to hire full-time arts teachers.

I didn’t think I would like teaching, but within a few months I was hooked. The students loved the opportunity to get out of their seats and participate in theater activities, and I was fascinated by the challenge of writing a lesson plan; it was like a magical chemistry experiment: two parts explaining directions, twenty parts playing games, one part classroom management. And it was a kind of performing, the curtain went up every time I entered a classroom.

I remember the exact moment I decided to stop pursuing acting. When I arrived at an elementary school in Far Rockaway, Queens for my third or fourth visit, I opened the door to the classroom, and the students exclaimed, “HE’S HERE!” At that moment I thought, “Nobody is excited when you walk into an audition room, but these kids, their teacher, and you are excited to be together in this classroom – go where it’s warm.”

I worked hard to improve my skills. I read books about teaching, went to conferences, and studied pedagogical theories. But the best way to learn how to teach, is to teach. So I took as many jobs as I could get, working with every age group from pre-K to high school, with students diagnosed with “special needs”, students who predominantly spoke Spanish and Polish, jobs in low-income neighborhoods and jobs at high-profile theaters offering programming for youth from wealthy families. I worked in schools, summer camps, and church basements. I loved theater, and I now loved teaching, which led me to a new dream: to become a theater professor.

In 2008, I enrolled in a graduate program without understanding all master’s degrees are not considered “terminal.” When I completed the program, I was devastated to discover my degree had no value in the academic job market. I sank into a deep clinical depression and spent the next year and a half digging myself out with the help of a skilled therapist. But in 2016, I had another lucky break: I was chosen for a Masters of Fine Arts (MFA) in Theater Directing. I earned my “terminal degree” in 2018. I was on my way to a successful career in academia, but a new kind of activism attempted to kill that dream.

Act III: Something Wicked This Way Comes

In the summer of 2018, I attended a national conference for theater professionals in higher education. A panelist with experience on hiring committees explained, “To teach theater and direct productions at a college or university, you have to have an MFA and you have to show the committee you can get yourself directing work at regional theaters.”

I left the panel deflated. During my final stretch of graduate school, we practiced “elevator pitches” for potential interviews with artistic directors. Although the professor said my pitch was excellent, I wondered, “Who would I pitch to? My chances of meeting with an artistic director are less than my chances of a sit down with the Pope!”

I knew this because an activist movement sometimes referred to as Critical Social Justice (CSJ) was deeply entrenched in the theater industry. In the same way Westboro Baptist Church demonized me based on an identity trait I could not change, CSJ activists in the theater were deciding who was a so-called “oppressor” based on identity. I was nearly everything they deemed “oppressive”: white, male, middle-aged and, probably worst of all, I identified as gay, not queer. For readers unfamiliar with the distinction, gay simply connotes same-sex sexual orientation while queer conjoins sexual orientation with a laundry list of radical leftist politics. Although many claim the word queer is “inclusive” of the variety of identities encapsulated in the ever-growing LGBTQIA+ acronym, as Andrew Sullivan explains, “queer” is “designed to trigger gay men, especially gay men who aren’t politically of the far left … to make us feel we aren’t part of the world or of the community.” Rather than function as a term of inclusivity, “queer” has been weaponized to identify and exclude traitors.

When I asked an aspiring playwright what she thought my chances were, she said white men had been directors “for so long” and it was time that they step aside. I didn’t think a person’s race or sex determined whether or not that person had the skills, talent or commitment to be a theater director.

Theater artists were the last people I suspected would attempt to bar anyone from participating in the arts based on identity. We were the oddballs, outcasts, and weirdos who accepted each other because our differences excluded us from mainstream culture. Now, my colleagues in the theater no longer saw me as a three-dimensional person with thoughts, feelings, and dreams untethered to my identity. Instead, I was nothing but an embodiment of identity characteristics they wanted to amputate.

I ran into a professor from my first stint in graduate school at a reception for theater directors in higher ed. Mid-conversation he said, “Look around this room! I’m the only person of color in here. I’m not feeling supported! Come with me.” Without telling me his intentions, he led me over to the event’s planner and told her the organization needed to do a better job getting “directors of color” into the room. I stood frozen, a dumbstruck pawn furthering someone else’s activist agenda.

I was used as a pawn again when I attended the second night of a festival of theater directors’ projects in development. The first two works came and went from the stage, but the third piece started on an odd note. A bald, middle-aged man stood center stage and a young female director sat far away from him on the stage’s edge. At first, I thought this was a curious experiment in hyper-realism, but I soon realized it was not a performance. The director apologized to the audience for the work presented the night before because, she said, she’d received several emails saying the piece “offended” and “harmed” some audience members. The man center stage chimed in, but was quickly cut off by the director who asserted, “I’m speaking now.” It was revealed the man was a former NYPD officer who asked the director to help adapt his experiences on the police force into a play. Suddenly, audience members who had been at the previous evening’s performance were standing and shouting at the retired officer. Each time he tried to defend himself, the director cut him off saying it was not his “time to speak.” The man’s wife stood up and pleaded, “My husband is a good man! He protected this city on 9/11!” But the ravenous audience continued to shred the retiree over the “offensive” and “harmful" words presented the night before, words we were now not allowed to hear. I never learned what the police officer said that caused this reaction. But from the way he was treated, it seemed his mere existence as a police officer was contrived as somehow “harmful" to these people—who wouldn’t even let him talk. After the “show” I approached the theater’s artistic director and said, “I didn't know I was going to be a participant in a public shaming before I bought a ticket to this event.” She said, “There were some things he needed to hear.”

On a cold January weekend in 2019, I was alone in my Brooklyn apartment desperately trying to hatch a plan to change my prospects in an ecosystem increasingly intolerant of people and views that did not conform to CSJ. To get a college teaching job, I needed to direct something. I decided I could either whine and cry that the activists were preventing me from realizing my dream, or I could create my own opportunity. If I couldn't direct a play at an established non-profit theater, maybe I could independently direct and produce it myself.

ACT IV: Burning Down the House

As part of my Teaching Artist work, I had experience “devising” original plays with youth. Devising is a theater-making technique that means collaboratively creating a play originating from an idea rather than a playwright’s pen. “Devisors” start with source material such as newspaper articles, transcripts of court documents, old photographs, paintings, stories, anything that stimulates ideas a devising ensemble can transform into a play. On that frigid weekend in 2019, I decided to devise a play from ghost stories by Edith Wharton. Best known for her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Age of Innocence (1920), Wharton skillfully used fiction to criticize rigid social structures and her lesser-known ghost stories overflow with rich social commentary and wry humor. I pitched the project to some colleagues from my MFA program. Excited both by the stories and my collaborative approach, they all said, “Yes!” They didn't see my identity as a liability, but my employers did.

In the fall of 2019, at an annual “back to school” workshop, I was, for the first time, segregated into what’s called a “racial affinity group.” When asked why we were breaking into groups by race, our supervisor said, “Because we live in a systemically racist country.” I was asked prior to the meeting via a Google survey if I was willing to participate in racially segregated groups, and I responded, “No.” After I was put in the “white affinity group,” I asked the facilitator why I had been segregated at work against my will. She told me she would get back to me. She never did.

At another arts organization, my supervisor called me into a private meeting to reprimand me for refusing to let my co-workers address me with “they/them” pronouns in emails. She said everyone was using “gender-neutral pronouns” in an organization-wide campaign to “dismantle patriarchal systems of oppression.” I let her know that I was a gay man, proud to be one, was not willing to let anyone else decide what my pronouns should be, and that applying pronouns to a person who doesn’t want them is the definition of “mis-gendering.” My supervisor bristled. I said, “Well then, we will have to agree to disagree.” In response, she slammed her hand on her desk, jumped out of her seat exclaiming, “NO!” and left the room. I wasn’t hired back.

I was also pressured to incorporate concepts from CSJ into my teaching. The idea was to “embed” theories such as Paulo Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” Ibram X. Kendi’s “Anti-Racism,” Judith Butler’s “Queer Theory,” Frantz Fanon’s “Decolonization,” Kimberly Crenshaw’s “Intersectionality,” Robin DiAngelo’s “White Fragility,” and Tema Okun’s “White Supremacy Culture” into pre-K to 12 arts-instruction.

Instead of spreading the joy and excitement of theater, I was to use theater instruction as cover for indoctrinating children into a worldview that taught them to see themselves as victims or “oppressors” based on their race and sex. When I voiced concerns, I wasn’t offered further work.

Determined to “dismantle” so-called “harmful white-centered” practices in the theater, activists were inadvertently destroying collaboration. The most important ingredient in collaboration is trust. Trust enables collaborators to bravely take artistic risks as an ensemble. But the activists were sowing distrust by reducing everyone to identities “oppressing” each other; re-casting benign interactions as overt acts of prejudice or covert insults like “white women’s tears” and “microaggressions”—the latter is a doctrine that turns everyday interactions, like asking where someone is from, into a grave racial insult if a listener decides their subjective feelings are hurt. Where there are no real insults or real acts of aggression, “microaggressions” can be manufactured out of thin air. Rehearsal rooms became ticking time bombs where activist artists could hurl overblown accusations of supposed psychic harm at any moment.

Not satisfied with obliterating collaboration, the activists jettisoned their audience. As reported in Washingtonian, when a theater endeavored to revamp its programming to create “the most woke theater in Washington,” the journalist wondered, “Can they do this without alienating a crowd who, liberal as they may be, might also be slower to get with the times?” To which an executive board member replied, “It’s entirely likely that as we continue the work we’re doing, we’re going to lose more people, and I think we’re all okay with that.”

I attended one show that ended by pressuring “the folks who call themselves white” to leave their seats and stand on stage to understand that they don’t “own” their seats. At another show, “non-Black audience members were invited to leave” before the end because the play was “not for or about” them. Some productions held segregated “black out” performances. How do you reach hearts and minds when you’re kicking hearts and minds out of the space?

When the pandemic hit, and all our work meetings took place on Zoom, I repeatedly heard the phrase “burn it all down” from my Millennial and Gen Z colleagues. Their perspective seemed to be the theater that existed before the lockdown was a racist, sexist, misogynist, homophobic, transphobic, xenophobic, capitalist (fill in whatever “-ists” and “-phobics” you could think of) oppressive system of “predominately white institutions” traumatizing artists through a “nonprofit industrial complex” (an oxymoron in any case) that needed to be vaporized. As reported in The Intercept, Millennial and Gen Z employees across the nonprofit sector were, in the words of one anonymous senior leader, “not doing well” and creating a “toxic dynamic of whatever you want to call it - callout culture, cancel culture whatever - [that’s] creating this really intense thing, and no one is able to acknowledge it, no one's able to talk about it, no one's able to say how bad it is.” It should have come as a surprise to no one that, during 2020’s summer of “fiery but mostly peaceful” protests, the atmosphere imploded.

First came the "Not Speaking Out” list, a Google spreadsheet listing the names of not-for-profit theaters that did not make a “sufficient” statement on social media about “systemic racism.” Then came “We See You White American Theater,” a twenty-nine page list of demands for reform that included race-based hiring quotas, ceasing “all contractual security agreements with police departments,” and requiring “creative teams to undergo Anti-Racism Workshops at the beginning of each rehearsal or tech process and ensure accountability with signed statements.” Finally came the targeted attacks on non-compliant individuals. One of the most heartbreaking incidents was the pressure campaign that preceded an executive director’s resignation. Her own staff circulated an online petition to the entire membership stating:

We are here to tell you that, underneath your dress of respectability politics, your slip is showing… it looks like your predatory tokenism of BIPOC staff members, your opportunistic fundraising, and your calculated obstruction of anti-racist programming.

This executive director played a major role in sustaining not-for-profit theater in New York City through the aftermath of 9/11 and "The Great Recession” of 2007-08 and was an ardent advocate for promoting women as leaders in the field. But the petition painted her as a notorious racist who needed to be excommunicated. I was horrified to see the document populated with the names of people I’d known for years. I declined to sign. No one publicly came to this woman's defense because the activists’ tactic was clear: do what we say, or we will cull you from the field too.

Overt discrimination permeated every meeting I attended that summer. At an organization established to support theater directors, one member asked the group’s president, “Can we have a conversation at some point about the ethics of white directors?” When asked for clarification, the member said, “This is about the ethical responsibilities of white… members as we work to transform the American theater… and whether white directors should be directing.” The president responded, “We’ve already begun to put a task force together… to help particularly our white members work through setting up rehearsal halls and production processes that are anti-racist.” It was odd that only white directors were singled out as needing support understanding what is or isn't “anti-racist” because, from what I saw, there was a lot of racial discrimination aimed at white people.

A prime example was American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter Keith Wann, who lost work solely based on his skin color. As New York Post reported, the director of ASL for Broadway’s The Lion King stated, “Keith Wann, though an amazing ASL performer, is not a black person and therefore should not be representing Lion King.” To be clear, and typical of the convoluted logic of this movement, the director was advancing the proposition that only black ASL performers should play the animal characters in The Lion King. Since when was it “anti-racist” to insist that only black people were uniquely fit to play animals? Citing race-based employment discrimination, Wann sued. According to court documents, the case settled in Wann’s favor with lightning speed. Perhaps this employer should have provided staff with “anti-racist” training that included Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John G. Roberts and his plurality opinion in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School Dist. No. 1, which states, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

Activists pressured artists to create theater aligned with their beliefs. As reported in The New York Times, the artistic director of a festival that once prided itself on being “uncensored” canceled a show because the playwright and performer dared to assert, “There are two sexes, male and female.” The artistic director explained, “I support free speech, I think all speech should be legally protected, but not all speech should be platformed.” Jonathan Rauch, Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institute, explains the motivation behind this type of behavior in his book Kindly Inquisitors, “In an orthodox community, the threat of social disintegration is never further away than the first dissenter. So the community joins together to stigmatize dissent.” Stigmatizing unorthodox views by canceling shows that express them is censorship, and theater artists used to know better: In 1992, Stephen Sondheim refused the National Medal of Arts award from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), stating it would “be an act of the utmost hypocrisy” to accept the award because the NEA had become “a conduit and a symbol of censorship and repression rather than encouragement and support.”

Unlike film, television and recorded music, live theater has no rating system; it should not look for ways to self-censor. Not only should theater reject self-censorship, it should overflow with a wide variety of plays that explore uncharted, daring and dangerous topics. Why not unleash diverse perspectives on various stages and let audiences decide what they think? Instead, activists insist the theater should be comprised of people who, however much they all may look different superficially, must all share the same beliefs. That’s not diversity, it’s monoculture.

If some artists want to create shows that extol CSJ, they have every right to pursue their projects. However, they have no right to bar other artists from daring to critique CSJ’s inconsistencies and intolerance.

Westboro knew they could hold slanderous signs, but they understood attempting to stop the show was beyond their purview–it’s time CSJ activists in the arts learned that lesson.

A few voices of dissent have begun to document the devastation caused by this activism as Clayton Fox does in his essay “The Toxic Gentleness of the American Theater”, but a New York Times article titled “A Crisis in America’s Theaters Leaves Prestigious Stages Dark” hints insiders know some of this “crisis” was self-inflicted. As an executive director admits, “Some theaters have forgotten what audiences want — they want to laugh and to be joyful and to cry, but sometimes we push them too far.”

ACT V: Building New Institutions

At the risk of being the skunk at the garden party, I don't believe logic and reason can be used to persuade theater leaders to take an off-ramp from their misguided allegiance to CSJ. Their devotion is fundamentalist in nature, and that is nearly impossible to pierce by persuasion, even if someone could get them to listen in good faith.

Look at the example of former Westboro member Megan Phelps-Roper: it took thirteen years of engaging with opposing views before she left the church. At fifty-one, I can’t wait for people to change their minds before I make art. The way to make art now is to build new institutions that state from inception a commitment to freedom of artistic expression, a recognition that ideological conformity is not a prerequisite for participation in the arts, and a pledge to refrain from making statements on social media about current events. If theaters want to tackle current events, do it on the stage.

Despite the storm around me, I pursued my ghost story project. I needed funding, so I looked for grant opportunities. One application asked, “Why this project, why now?” I wrote that a project based on ghost stories was relevant to the moment because they are about our relationship to transgressions in the past. Every ghost story features the living encountering an apparition who returns either to make the protagonist aware of a past injustice, or to punish the protagonist in the present. Considering Ibram X. Kendi declared in How to Be an Anti-Racist, “the only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination,” I thought it would be meaningful for audiences to experience what happens when people are punished for things in the past, whether they had anything to do with the earlier transgression or not.

It worked! In 2021 I received two small grants to produce and direct Unearthly Visitants. The project went so well that my collaborators and I decided to mount a second show, an adaptation of E.M. Forster's 1909 science fiction story "The Machine Stops." In a review, a critic wrote the play was "a Space Mountain roller coaster ride, an intellectual white water rafting expedition, a production that will have you talking about it for hours and days to come.”

Every moment putting those shows together was pure joy and fulfillment. I didn’t “embed” CSJ into the rehearsal room or the plays. I didn’t force the ensemble to declare preferred gender pronouns, no one was accused of “microaggressions,” and I didn’t impose my socio-political beliefs onto anyone else. The rehearsals were about the bliss of creating the best productions we could devise.

Identity is important. I don't deny that. My identity surely informs my views, but it is not the totality of who I am. Reducing everyone to the same person based on identities serves activists’ causes, but we are simply not all the same.

Artists have choices: they can use identity to blame, shame and divide, or they can use identity to bring people together, helping us see what we have in common, despite our differences. Most new theater I've seen that wades into identity expresses a contradiction that linguistics professor and New York Times columnist John McWhorter identifies in Woke Racism: “You must strive eternally to understand the experiences of black people,” while simultaneously insisting, “You can never understand what it is to be black, and if you think you do you’re a racist.” McWhorter discusses only race, but the contradiction he pinpoints has been applied to various “oppressed” identities in several plays. This fashion is wearing itself out, but I fear it will leave behind a long-lasting stain of resentment, assuming an audience remains in its aftermath.

One of the four Wharton ghost stories I chose to include in Unearthly Visitants, “The Eyes,” featured a main character Wharton strongly suggests is homosexual. The story shows the cost he pays for not accepting himself. Anyone can identify with struggling for self-acceptance. Wharton didn’t wield homosexuality as a weapon to berate and alienate, she used it as a window to let readers experience the price paid for refusing to accept oneself. Theater should offer audiences more windows, and fewer mirrors merely reflecting back every audience member's identity.

Being an independent producer and director is hard, but rewarding. I choose who I work with, what we work on, and how we collaborate. It’s a lot of responsibility, but when things go right it feels great. It’s not what I imagined I’d be doing in my fifties, yet here I am, putting together my third production: an adaptation of Russian dissident Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1924 dystopian novel We. Zamyatin is a true hero: a Bolshevik who left the party when it declared “all art must be useful to the movement,” he spoke out against party orthodoxy when doing so had mortal consequences. In his 1921 essay “I Am Afraid,” Zamyatin wrote,

“True literature can exist only where it is created, not by diligent and trustworthy functionaries, but by madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels, and skeptics.” The same could be said of “true theater.”

I owe both the Westboro Baptist Church and Critical Social Justice activists heartfelt gratitude because their efforts backfired: instead of culling a gay, white, middle-aged artist from the field, they created a resourceful, resilient and persistent artist, committed to freedom of expression, fairness, a belief in common humanity, and hellbent on finding joy and fulfillment as a theater director – isn’t that a great thing.

And I haven’t given up my dream of getting a college or university teaching job. As the saying goes, “Don’t quit before the miracle.”

Epilogue: Calls to Action

Essays like this can make readers feel overwhelmed because things aren’t changing fast enough. Fear not–there are things you can do to help:

Like and follow artists whose work you support on social media;

Subscribe to Substacks and alternative publishing outlets like this one;

Write a letter to your local theater. If you see a show you liked, let them know. If they put on lousy shows, write a letter telling them you didn’t like what you saw and why;

Don’t give money to theatrical institutions putting on shallow morality plays. Instead, give money to organizations you like. Send a letter explaining why you didn’t contribute to the former’s annual fundraiser and why you did to the latter;

Keep in mind the saying, “Politics is downstream of culture.” If you care about the future of our country, get involved in the arts.

==

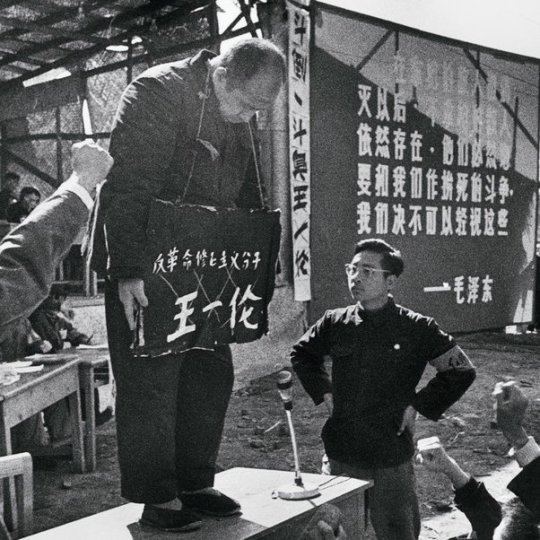

“I didn't know I was going to be a participant in a public shaming before I bought a ticket to this event.”

This is literally what they did in China. It's called a struggle session.

#We The Black Sheep#Kevin Ray#corruption of arts#the arts#social justice activism#critical social justice#ideological conformity#ideological capture#ideological corruption#Westboro Baptist Church#racial discrimination#woke racism#wokeness#woke#cult of woke#wokeism#wokeness as religion#politics is downstream of culture#religion is a mental illness

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you mind if I ask your top 10 favorite characters (can be male or female) from all of the media that you loved (can be anime/manga, books, movies or tv series)? And why do you love them? Sorry if you've answered this question before.....Thanks...

Character: Draco Malfoy (HP) Why I love them: I don't. I love the version of him I frankensteined together from fics I read/wrote as an undiagnosed autistic preteen who wished I knew how to be meaner, and was hopelessly demisexually gay for a brunette with glasses.

Character: Uzumaki Naruto (Naruto) Why I love them: Emotionally neglected ADHD powerhouse who thinks "what do 600 hot girls look like? Me with titties and pigtails 600 times obviously" followed by "what do 600 hot boys look like? All my male friends with bedroom eyes OBVIOUSLY" and somehow hasn't figured out he's into dudes and is probably genderfluid. The Haku and Zabuza arc came SO close to "child soldier figures out that making children into soldiers is bad, actually, and resolves to create a better society where fewer people needlessly suffer" but then I think the author got old and forgot his own trajectory in favor of endless spectacle creep and, idk, something about the moon crushing Konoha or whatever. I lost interest in the story, but not the BOY. Also his relentless fixation with that dark haired cool guy he kissed one time makes every other character feel awkward, and I relate to that.

Character: Urameshi Yusuke (Yu Yu Hakusho) Why I love them: LOVE me a guy who even HEAVEN writes off as an irredeemable asshole surprising everyone with an act of selflessness. Love me an asshole who dedicates his life to love and friendship. Yusuke's narrative is basically "Obviously all yokai are evil. Wait, some aren't (some of my best friends are yokai)? Wait, most aren't (I actually really enjoy the yokai world/community)? Wait, I'M a yokai? (THAT'S why I am the way I am, and actually that's not evil it's just different)??? So there's evil humans AND evil yokai but neither are inherently bad, MOST are just regular people on both sides, and both are worth protecting" and anyway this is a neurodivergent and queer allegory to me, which slaps severely.

Character: Shi Qingxuan (Heaven Official's Blessing) Why I love them: Gender

Character: Luke Fon Fabre (Tales of the Abyss) Why I love them: Nobody's doing character growth like this little shit. An icon. It takes like 30 hours of gameplay for him to become likable and when he does it's somehow genuinely worth it.

Character: Changheng (Love Between Fairy and Devil) Why I love them: (I'm picking only one character per story, which is the only reason Xiao Lanhua and Dongfang Qingcang aren't also on this list.) You're telling me the God of War's narrative is a "tragic princess, betrothed since childhood, can't escape her family's expectations, constantly has to put everyone else above herself, until finally she snaps" story blended with "man who has been forced to live in war, falls for the first person who acknowledges that he, too, needs protection, ultimately rejects the violence he's been forced to endure and enact in favor of pursuing peace" and I'm what? NOT supposed to go insane? Also his nose freckle gives me heart palpitations.

Character: Logan Echolls (Veronica Mars, specifically season 1) Why I love them: What an excellent example of a badly coping shithead jerk fuckup boy who would be SO soft in any context where he's not under constant threat. Something about his mouth-breathing under duress compels me.

Character: Kyo (Fruits Basket) Why I love them: Badly coping under duress, the entire system is stacked against him, anger management issues and the snatched waist of a 90's manga twink. What can I say, a feral cat finding stability and love gets me every time.

Character: Xue Yang (MDZS) Why I love them: Irredeemable asshole feral cat ass man, coping badly at all times with all things but holding it together with a winning personality (gratuitous violence and bad jokes). Falls SO hard for the first person to show him love and kindness, becomes SO soft when not under threat for the first time ever, and then fucks up SO badly he ruins his whole fucking life. Spends more time trying to get back what he lost than he actually HAD what he lost. He's irredeemable. He's irredeemable. He makes apple rabbits for A Qing because she's sad. He's irredeemable. He doesn't pull a weapon on Xingchen even when Xingchen has already stabbed him and he's renowned for violence and revenge. He's irredeemable. I starting writing a post in his defense and hit the character limit halfway through my 'notes to flesh out later' bullet pointed list. He's irredeemable?? Xiao Xingchen could, though, is all I'm saying. The deeper you look into his actions the more humanity there is to find. I'm rotating every single thing about him in my mind like a rotisserie chicken.

Character: Chu Wanning (ERHA) Why I love them: He's hopelessly demisexually gay for literally just one guy. His story is gratuitously tragic but with a happy ending. Autistic Yearning incarnate. He's a burnt out husk of a blushing virgin, and the horniest person alive. Would readily die for his convictions, but won't ask for help. Prettiest wife anyone could ever wish for, with a strong masculine jaw. Total knockout gorgeous with body dysmorphia. Hyper competent with zero emotional intelligence. Widely respected and beloved with intense self loathing. He's never not masking. He's an atticked wife, he's a bossy husband, he's a piece of wood. He's 45. He's 6. He's 20. He's 32. He is catnip for me.

#mo dao zu shi#mdzs#xue yang#asks#anon#2ha#erha#erha he ta de bai mao shizun#lbfad#love between fairy and devil#naruto#yyh#yu yu hakusho#i'm not gonna tag all these#anyway I love asks like this it just always takes me a while so [blesses you with patience] or whatever

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last year, a childhood friend of mine ran for mayor. Tonight, she gave a presentation about the experience and how to get politically involved and stuff. But I'm not here to talk about her actual thesis. I'm here to talk about some details she mentioned in passing.

I knew there was some kind of drama between her campaign and the Democrats in our state, but I didn't know the details. My friend didn't talk much about that, but she mentioned some disparaging remarks various people had said to her over her campaign, and it sounded like some of them came from institution Democrats.

One point she mentioned was that basically nobody expected her to win. She was running against someone I'll call the Incumbent; he wasn't actually in office last year, but that's just because he took a term off after sixteen years in office. He's a Republican, but a pretty mild one; conservative, but not violently reactionary. The Incumbent was expected to win with over 90% of the vote if anyone ran to oppose him.

When my friend made her candidacy official, she started getting advice from institution Democrats. (I'm not sure exactly who, because my friend was trying to explain the challenges she faced without saying anything mean about the Democratic Party, but I don't know who else would say this kind of stuff.) They told her to stop making a big deal about LGBTQIA+ rights, abortion rights, etc etc.

The things they told her to stop focusing on weren't my friend's entire campaign (she didn't mention pushback about her "affordable housing" rhetoric), but they were some of the pillars, the things that made me and other people want her to win. It almost sounded like they were asking her to be a different version of the Incumbent—a few different policies, a blue tie instead of a red one, but basically the same moderate policy proposals.

My friend ignored them, doubling down on all the "controversial" topics that she cared about. She's far from the only person who cared; she got 42% of the votes, not the <10% expected. I have no doubt that she got that many votes because she was willing to make a stink about those controversial issues, because she was willing to be more than "Incumbent, but blue".

...

My friend is a big fan of Obama. Say what you will about the man, but he promised Change You Can Believe In. Obama ran with a similar strategy to my friend's—he made big promises about things people cared about. Some people hated it, but most of them wouldn't vote Democrat. By contrast, many moderates and the disaffected liberals found his promises compelling and turned out to vote for Obama.

Candidates who promise change earn votes. But the Democrats keep supporting candidates like Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden, saying it's to secure the moderate vote. They take it as a given that they don't need to appeal to left-liberal voters, because who else are they gonna vote for?

(And maybe, just maybe, the institution Democrats don't actually want the change their candidates promise.)

I don't think that's unique to the USA's Democratic party. I've seen liberal politicians across the Pond compromise on progressive issues, only to be defended by their constituents. They have to make those compromises, you see, or they won't get elected! Making a big deal about serious political issues will alienate moderate voters, after all, and they're the only ones we should worry about. Who else are progressives and leftists and queers gonna vote for?

Their strategy relies on a combination of overwhelming threat from conservative politicians and "vote blue no matter who" rhetoric. (Or "vote red if they're not dead," in countries where the liberal party is red. The US has to do everything its own way...) As long as they can safely assume the left wing of their population will vote for them out of desperation, they can shift as far to the right as they want. It's better than the nascent fascists in the other party, after all!

I don't have a solution. I understand the short-term strategic strategy of voting blue for damage control, but in the long term that just enables them to slip farther to the right.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

[huge disclaimer up top that I am incredibly lacking in knowledge as to queer/lgbtq+ history and culture in Thailand, especially outside the context of globalized queer identity, so this post should absolutely not be taken as any sort of authority or statement on the topic; i'm just in the very beginnings of doing my own research and wanted to sort through some thoughts as well as see if anyone else out there knew more or could point me toward other sources]