#as they did when other prominent gay men died of AIDS

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

this is probably going to be long

OK, I lived through the AIDS crisis. I was a young person questioning my sexuality at arguably the worst possible time in American history. I discovered the word "bisexual" (hooray I have a label) only to read a few days later in mainstream news about how "bisexuals were responsible for spreading AIDS to the hetero community" which was a take that was tolerated on national news shows at the time. The only sex education I had in my entire public education was a film we were forced to watch about how you could get AIDS from french kissing (you can't) and heavy petting (which we didn't know what it was because it was outdated old people code for oral lol)...

The entire LGBTQIA plus community was not attacked as a monolith, the focus of hate came on gay men, because they were the most obviously effected and also the most visible and prominent in the community. The rest of the community did their best to embrace and protect them. (For example lesbian groups that were on the front lines of caring for people who were sick when no one else would...).

And there were people like myself who identified as allies but were in a place where they didn't feel safe to come out themselves. I did not come out at that time because even though I was in accepting local community at University and working at a feminist journal I knew I would lose friends and family and possibly future work opportunities. Being Bi it was easier to blend in for me and I took advantage of that. Part of the reason I hesitated so long about coming out was I felt a lot of guilt that I didn't come out in the 90s during the AIDS crisis. I felt like a coward who wasn't worthy to stand with such brave people.

It took me a long time to let go of that self-hate to the point where I could come out. A big part of it was acknowledging how fucked up the climate for LGBTQIA folks in the 80s and 90s. We had two family friends (which is how I knew I would probably be rejected by a lot of my family) who died of AIDS. Yes, these were brilliant, creative men who worked in theater. One of them was the props coordinator for Late Night with David Letterman (responsible for building Dave's velcro suit etc.). I also have a peer who died of AIDS in the early 2000s, long after the disease had supposedly been "not a death sentence" who also happened to be an actor.

Despite their lack of political involvement, they were be seen as radical just because they lived openly as gay men in a society that hated them and wanted them dead, and only tolerated them if they were the "fun gays" who weren't actually threatening the status quo...

Being in theater or the arts was a survival tactic for a lot of people ya know because it was a more accepting environment and because it wasn't considered important like politics, medicine, science etc. (Miss me with the gays can't do math jokes. A gay man invented the fucking computer).

The gay men I knew in long-term monogamous relationships survived the worst of the crisis and they automatically became "respectability queers" for having not died and wanting jobs with health insurance etc. Because one dude follows his dream of working in theater and the other quits theater and goes to work at the phone company and buys a house with his partner, one is fun and the other boring? One is a creative genius creating culture and the other is a consumer of cultural pap? Wow. Great take.

FUCK. I'm just getting so angry thinking about this. You want to know why it took me till I was FIFTY fucking years old to come out: AIDS. That's it. ONE Fucking word.

Sorry I have no idea WHY I fucking started this other than I saw a shitty post that said, our culture became boring because all the fun gays died and left only the boring gays who only care about marriage or whatever.

#Also: what the fuck is wrong with CATS and ghostbusters???#both are great#both have their value#if you want to bitch about marvel or shitty broadway musicals then do it#please don't throw all the old gays under the bus for being boring while you do it#also there was that post yesterday about Anthony Perkins and I did not realize he died of AIDS#I don't know how I missed it...oh it happened in 1992 when I wasn't living at home and didn't have a tv...#sometimes the sex positive bubble of tumblr will prefer the LOLZ lifetime achievment of fucking take#over the he was conflicted because all of society hated him for being gay and many many shitty people rejoiced I'm sure when he died take#as they did when other prominent gay men died of AIDS#PS: those are the same people trying to pass legislation attacking trans people#the same fucking people

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paris Is Burning

Continuing my series of learning about things referenced in the book, I'm looking at things Alex references when he talks about engaging with queer history. These are all tagged #a series of learning about things that are referenced in the book, if you want to block the tag.

Please note the following topics are metioned: murder, AIDS - and death due to complications, sexual violence, sex work, racism, queerphobia.

Paris is Burning is a documentary film, released in 1990, that focuses on the 1980s ball culture of Harlem (New York) and the communities of gay & transgender African-American &Latino people involved in that culture. It offers an exploration of race, class, gender, and sexuality in the US at that point in time. The AIDS crisis was growing in severity, and impacted many of the people involved with the documentary. Many of them have since died due to AIDS complications - including Angie Xtravaganza (age 28), Dorian Corey (age 56), and Willi Ninja (age 45).

Documentarian Jennie Livingston interviewed key figures in the ball world, and the film features monologues from many of which addresses their understanding of gender roles, subcultures of both the ball world and the queer world, as well as sharing their own life stories. It also provides an introduction to slang terms used within the subculture, such as house, mother, shade & reading. Interspersed with this is footage of colourful ballroom performances. The documentary also looks at how AIDS, racism, poverty, violence, and homophobia impacts their lives. Some of those involved became sex workers to support themselves, at great risk to their safety - one member is found strangled to death, seemingly by a client. The 'Houses' of the ball culture provide safety and security to those disowned by queerphobic parents, as well as those largely ostracised by mainstream society.

The documentary did have some criticisms - notably for reinforcing stereotypes, having a white filmmaker, and for not properly providing compensation - but it has remained important as a depiction of ball culture, the most prominent display until Drag Race began to popularise the concept to a wider audience.

-----

Ball culture - also known as the Ballroom Scene/Community, Ballroom Culture or just Ballroom - takes its origins from a series of drag balls, including those organised by William Dorsey Swann (the first person known to self-describe as a drag queen) in Washington DC, during the late 1800s. These drag balls were masquerade themed and took place to defy laws which banned people from wearing clothes of the opposite gender. Many early attendees were formerly enslaved men, and the events were held in secret. While balls were integrated during a time of racial segregation, non-white performers regularly experienced racism from the white judges and performers. This prompted Black and Latino performers to create their own spaces within the subculture, and the modern culture grew out from Harlem in the late 1960s, spreading to other major cities soon after.

The structural and cultural issues facing the community in 1980s New York - including poverty, racism, homophobia, as well as sexual violence and AIDS - didn't stop Ballroom from thriving, acting not only as an escape from real life but also offering those involved a support system that was not often present in other areas of their lives. The culture included a system of 'Houses' - headed by an elder queer person (although often not much older than those in the family), either a 'mother' (mostly gay men or trans women) or a 'father' (mostly gay men or trans men) - which would become a surrogate family for young queer Black and Latino youth who were estranged from family, homeless, and/or struggling to get by. House members would often take on the surname of their house parent, and the houses would compete together in balls - often with a specific style identifiable as belonging to that group.

Drag ball culture works to resist the dominant cultural norms people experience from wider society. The performers create a space to challenge gender roles and heteronormativity through subversive outfits, slang, and actions. It gives them a space to feel supported and to work through their abuse they experienced as members of minority groups.

The balls not only provide a community, but also provide spaces for education. Aware of the prevelence of AIDS and the lack of support, in 1990 the Gay Men's Health Crisis (GMHC) launched the Latex Ball to distribute health information to those involved in ball culture. Offering free HIV testing and prevention materials, it attracts thousands of people from around the world and is still active to this day.

-----

The importance of Paris is Burning continues to grow as the years pass. It was a rare film that focused on the lives of queer people of colour, whose charisma and humanity shines through in their witty to-camera interviews and their fierce routines and performances.[source]

Sources: Wikipedia - Paris is Burning Guardian - Burning down the house: why the debate over Paris is Burning rages on Vanity Fair (archived) - Paris Is Burning Is Back—And So Is Its Baggage Janus films - Paris is Burning Wikipedia - Ball Culture Rolling Stone - Striking a ‘Pose’: A Brief History of Ball Culture All Gay Long - A Brief History of Modern Ballroom Culture Shondaland - The Psychological and Political Power of Ball Culture

Additional Reading: Paris is Burning, 1990

#elio's#elio's meta#a series of learning about things that are referenced in the book#long post#alt text added#rwrb#red white and royal blue

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Profiles of Pride: June 21st! 🏳️🌈Phill Wilson🏳️🌈

Phill Wilson (born April 22, 1956) founded the Black AIDS Institute in 1999 and served as its CEO and is a prominent African-American HIV/AIDS activist.

Phill Wilson's career in activism started after he and his partner, Chris Brownlie, were both diagnosed with HIV in the early 1980s. This was at a time when the AIDS epidemic was just starting in the United States, and Wilson has said he did not feel like anyone was bringing together the black community to solve the problem. The country believed that AIDS was a gay disease, and outreach was primarily focused in white, gay communities, when Wilson believed that AIDS affected the black community much more. When his partner died of an HIV-related illness in 1989, Wilson channeled his grief into activism.

In 1981, Wilson was already involved in the gay community in Chicago through sports activities and social activities. He attended Illinois Wesleyan University, where he got his B.A. in theater and Spanish. When he graduated, he moved to Los Angeles in 1982, and got involved in the National Association of Black and White Men Together. His first jump into the activist lifestyle came in 1983, when he read the poem "Where will you be when they come?" at a candlelight vigil for AIDS victims, which he also helped organize.

After organizing the candlelight vigil in 1983, Wilson began working as the Director of Policy and Planning for the AIDS Project in Los Angeles. During this time he was also the AIDS Coordinator for Los Angeles. From 1990 to 1995, Wilson served as the co-chair of the Los Angeles HIV Health Commission. In 1995, he became a member of the HRSA AIDS Advisory Committee. Wilson took a break from work in 1997, when his disease became too immobilizing. Wilson went back to work in 1999, when he founded the Black AIDS Institute. In 2010, Wilson became appointed to President Obama's Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS, becoming the co-chair of the disparities subcommittee. During his career, Wilson has also worked as a World AIDS Summit delegate. Also during his career, he, along with other Black AIDS activists, "urged the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to provide additional funding to African American groups eager to educate and mobilize their community around HIV/AIDS issues. The result was the announcement of a 5-year domestic 'Act Against AIDS' campaign that resulted in 14 Blacks organizations, including the National Newspaper Publishers Association, being awarded grants to hire an AIDS coordinator to expand their work.

"Wilson has said that when he dies, he hopes people will remember him for not giving up. His biggest fear is that the black community will give up fighting against this disease.

In June 2020, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the first LGBTQ Pride parade, Queerty named him among the fifty heroes “leading the nation toward equality, acceptance, and dignity for all people”.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

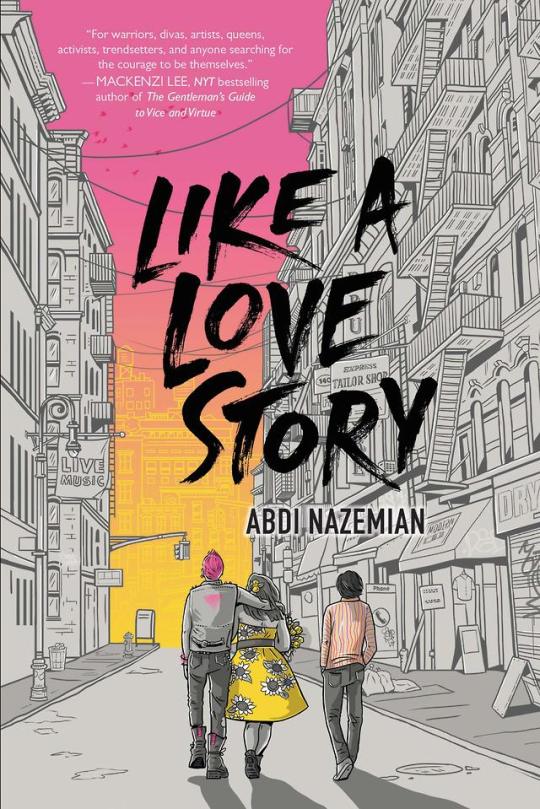

Like a Love Story by Abdi Nazemian

[Goodreads]

It's 1989 in New York City, and for three teens, the world is changing.

Reza is an Iranian boy who has just moved to the city with his mother to live with his stepfather and stepbrother. He's terrified that someone will guess the truth he can barely acknowledge about himself. Reza knows he's gay, but all he knows of gay life are the media's images of men dying of AIDS.

Judy is an aspiring fashion designer who worships her uncle Stephen, a gay man with AIDS who devotes his time to activism as a member of ACT UP. Judy has never imagined finding romance...until she falls for Reza and they start dating.

Art is Judy's best friend, their school's only out and proud teen. He'll never be who his conservative parents want him to be, so he rebels by documenting the AIDS crisis through his photographs.

As Reza and Art grow closer, Reza struggles to find a way out of his deception that won't break Judy's heart--and destroy the most meaningful friendship he's ever known.

Thoughts:

Spoiler-Free Thoughts:

This was a book that I instantly became excited for when I learned what it was about. It discusses queer love, HIV/AIDS, NYC, the late 80’s, and those are all right up my alley. I’ve personally spent a lot of time educating myself about this history, be it in classes such as the one I took that focused on QPoC and HIV/AIDS specifically, or online, so you can say I’m pretty invested. I even wrote my own short story that focuses on similar themes (more on that some other time). Those parts of this book were so great, to an extent. One of my favorite historical moments is the St Patrick's Cathedral protest in the late 80’s, the die-in, where an individual can be heard screaming ‘You’re killing us!” and that made it into this book. So many other important historical moments made it into this book and I think that is its strongest aspect.

I was also excited about this book because it discusses this topic AND is by a person of color, an Iranian American specifically and one of the main characters is Iranian American as well. I felt like, ‘who better to explore themes of love and friendship during this time than someone who was alive during that time and also is a person of color’, aka, a voice I don’t hear enough of when discussing this topic. So much of this book is important! The queer Iranian representation, the queer youth rep during this time in history, queer sex + safe sex, the iconic activism, and even just some of the general references. I respect this book for that alone, for attempting to tackle it all and doing some of it very well.

Unfortunately, I had a lot of problems throughout the book. I know one or two might be very biased and personal things, but I know there are some I would like others to know or talk about. This includes: love triangle/melodrama?, general pacing, Madonna, the white characters, cis-normativity, privilege, the pov’s, and more. I will discuss that below, so run to read the book (if you want) or continue to read my spoiler-ful thoughts!

Spoiler-ful Thoughts:

I feel like some of what I have to say might be controversial so bear with me. For context, I am a young queer Mexican-American writer from Los Angeles, and that’s where I’m coming from with this, identity wise.

I was so stoked to hear this history told in a PoC perspective but aside from the author being of color, I don’t actually think I got a PoC perspective??? Let me break that down. First of all, the story is a multi-pov that alternates each chapter from Reza, Art, and Judy. Realistically, 1/3 of the story is told from the Iranian American character’s eyes. Then the other two are white characters. That itself is where I began being a little iffy (because, again, I was excited about a young PoC pov on this topic) but I was open, especially because I enjoyed them all in the beginning. I just didn’t understand why we needed a straight ally’s point of view? Overall her arc fell flat, aside from the cute moments of fashion design or that moment with Reza’s brother surprisingly. I would have been okay/would have preferred if it was just Reza and Art’s pov though.

In relation to Judy, the whole romance between her and Reza and then Reza and Art was so overblown and unnecessary. Reza didn’t need to date her, though that is a valid and relatable gay teen feels. I wish it ended in that “oh!!! you’re gay, wait!! lol let’s be friends then!” thing. Instead, she’s in love with him for half the book, super pushy with sex and gets extremely upset with Art for… liking Reza, and then you don’t ‘see’ her much throughout the rest of the novel anyway? It just felt so unnecessary, and so love-triangle-y. I did really like Art’s “you don’t understand how it is to like someone and be gay” speech cos felt valid to gay teen vibes, but that could have just been said in a way less dramatic argument? It really made no sense to me.

Before we leave Judy, lets touch on privilege, specifically white privilege and class privilege. Reza’s family, was once poor but now filthy rich. Art’s family, filthy rich and white. Judy’s family, allegedly shown to not be ‘rich’ by the two lines that say “my friends’ rich parents gifted us that cos we’re not as rich as my rich friends” and yet there is really no discussion on that any deeper than that. Like why are her parents not shown working, her mother especially? And her uncle? He lives alone in an apartment in the upper east side or whatever, and doesn’t work anymore? I might have missed that but I shouldn’t be able to just ‘miss that.’ Like, how did they pay to go to PARIS. It just didn’t at all feel like a story I could relate to or one that this history could relate to entirely. Like, even them having a whole ass wake/party thing for her uncle in a night club? Most people who died of AIDS complications didn’t get that, especially not ones who aren’t from ‘not-rich-families’. It was subtle and yet the smell of privilege was everywhere.

Then even Art and Reza’s relationship was also weird? It was forbidden then it immediately wasn’t and they were in love, due to one or two time jumps that really did not help to build their relationship at all. Okay though, some teens love easily, especially gay teens who don’t know many other gay teens so it could slide? Then, however, there is this really real and valid fear ingrained in Reza regarding AIDS and gay sex. He is terrified, and I loved (and hurt) for how terrified he was because it felt reasonable. What I didn’t love was, knowing this, Art was also super pushy sexually? Do you realize he, at multiple times, tried to pressure Reza into sex and once even got naked and pushed his body against him? Doing this after full well knowing how uncomfortable Reza was? No, thank you. From the author’s note in the book, I felt like MAYBE this could have been intentional and not meant to be an extremely positive? While that could be a stretch, it also doesn’t at all criticize or directly address this toxic behavior so boop.

This brings me back to not feeling like I get a QPoC perspective. Reza is our main queer person of color, and really the only prominent one (Jimmy was a rather flat character). Yet, everything else revolves around whiteness. I already addressed Judy taking up space as a narrator. Then there is Art, the super queer activist teen. He is mostly where Reza learns all the queer things from, and he is mostly the perspective where we see the queer action/activism from. Then, who is the elder HE learned everything from? Stephen, the gay white poz uncle of Judy. THEN, who do they frame EVERYTHING around? Madonna, the straight white woman.

Sure we hear about Stephan’s deceased Latino boyfriend and, as I said, Jimmy didn’t have much character to him aside from wearing a fur coat, saying “my black ass,” and helping move Stephan’s character along. He also has one of the few lines that directly addressed qpoc, where he says qpoc are disproportionally affected by AIDS but no one is talking about it. Ironic. It almost rarely addressed PoC throughout the rest of the novel. Heck, it almost never addressed trans characters either. What about the qpoc and trans woc who were foundational to queer rights movements that take place before this book? Sure he name drops Marsha P. Johnson, in passing, on the last page of this 400 page book, but why not mention them in depth even in one section?

Someone asked me, why does the author HAVE to do all of this. Why do they have to representing everyone, like Black trans women. Isn’t that unfair? My answer is no, it’s not unfair in situations like this. This author isn’t writing just a casual romance/friendship story. No, he is heavily touching on so much literal queer history and yet leaving out so many key players that are so often left out because of white-washing that happens in history. He didn’t even have to name these people, but just addressing that they are there as a community. Instead we get two or three throwaway lines about Ball culture after they “went to a ball that one time,” a random line from Jimmy, and a Marsha P. Johnson name drop at the end. It is honestly disappointing.

Even framing everything in the words of Madonna was a bit much for me. Sure, I know of her history and importance to queers so this is one of the more biased parts of this review. I just don’t think we needed several references to her every other page. I then screamed when, not only did we time jump like 20+ years (gays don’t do math, sorry) and the last quote is Lady Gaga! Oh, my god. I won’t linger on the white popstar allies because it’s not worth it. In regards to that time jump, though. It felt unnecessary as well, just trying to tie it all up with a bow. It’s reference to Pulse seemed random, and honestly felt a bit cheap, but so did lots of the things I’ve referenced.

Lastly, why did Art abruptly lick Reza’s lips out of nowhere, or when he was angry it was shown by saying “ and his brow sweats”? Anyway, I’m bummed out. I haven’t been reading as much this year or writing reviews but here I am, writing a novel-sized review basically dragging this book. I liked it enough to finish, and I think it’s important. I know some queer kids reading this will love it and learn from it but I just couldn’t help but realize that right under the surface, this book was sort of a let-down.

Thanks if you read all of this, and also sorry at the same time. Share your thoughts!

#this is a pretty blah review - the book was just a bit disappointing#2019#Like a Love Story#abdi nazemian#the boy who cried books#3/5#review

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Take on Bohemian Rhapsody

Let me say, Freddie Mercury, is an inspiration of mine. He is a queer icon. An icon for the bullied and abused. And importantly an icon for how to be a wonderful, caring person despite international fame. The movie Bohemian Rhapsody has definitely shed some light on him, making these more apparent. I just want to rave about this movie but also point out some things that if the movie had more time I think more representation would have been nice. I just want to address certain things that I have seen come up that I think are problematic and deserve discussion

“Bohemian Rhapsody erases the AIDS crisis!”

No, it doesn’t erase it as that implies that it was never a part of the story. It was artfully woven in and melded into Freddie’s life. It was just as much a part of his life as his cats and his work with the band. AIDS is woven into the story outside of his life as well, adding to his insecurities about his sexuality and life with Paul Pretner. Don’t get me wrong, when I first heard this I was upset. As an activist against the stigma of HIV/AIDS, I was upset that this outlet that we could have had was not speaking of it. But it’s not what Freddie wanted. He never wanted to be a poster boy for the disease as he knew that not only it would ruin his career and the career of the band but it would be all he was remembered for. His life was music and he wanted that to be his legacy as well. It was his decision to not reveal his diagnosis until 24 hours before his death. To make the movie a PSA for AIDS would have not been a legacy to him which is ultimately what Brian and Roger were trying to do. The only thing that I think was poorly done, albeit being necessary to the plot is the fact that they shortened Freddie’s life by two years by altering the timeline of his discovery of his diagnosis. He was unaware that he was infected until 1987 and Live Aid occurred in 1985. Freddie had been in a relationship with Jim Hutton for two years at the time of his diagnosis. I know that they wanted to artfully integrate his diagnosis into the story, I seriously didn’t care for the shortening of his life. I also think that this could have been included and would have helped introduce Jim more into the story.

“The movie is bi-erasure!” or “Freddie Mercury wasn’t bisexual, he was gay!”

I will admit that I agree that the issue of Freddie’s sexuality could have been better portrayed having shown more of his other relationships than his one with Mary Austin. I wish that Jim Hutton could have been more in the movie as he was a pivotal person in Freddie’s life towards the end. That man was his husband, he wore a wedding band for him. He lived happily and shared his final breaths with Jim. Mary was also this for him. He wanted to marry her. He wanted a life with her. Women were just as appealing to him as were men. She was a large part of his life, especially during their early career, of which the movie focuses on. To erase her is to not tell a huge part of Freddie’s life. Where I find fault in the discussion of Freddie’s relationships is the fact that the prominent male relationship shown in the movie is Freddie with Paul Pretner, his decidedly most toxic partner. I don’t say this in just my pure dislike of him. The band, as well as Freddie himself, admitted that his influence was harmful for Freddie and led him to unhealthy behaviors. I was sad to not see Jim get more screen time as that relationship was full of love and admiration, something that Freddie needed as an insecure man. In Jim, it seemed he found the same home he found earlier with Mary and I definitely think that this is downplayed in the movie, much to my chagrin.

I think we too often forget that Freddie is not here to speak for himself. This is a devastating fact to his fans and his friends and family. Brian May and Roger Taylor, two of his bandmates and dearest friends were the producers of the movie. They were there from the conception of the film, during the filming, and along the press tour. They made it clear to the directors that they wanted to pay homage and give love to a wonderful man that died way too early. You can tell they miss him dearly and would love to have him back. It’s one of the reasons bassist John Deacon retired from music. So yes, of course, Roger and Brian are going to edit things and focus on a specific timeline. That is precisely what they did. They focused on the bands early years from the late 1960s to 1985 and their performance at Live Aid. It is true chronologically that Mary was his more present love interest at that time. It is also true that Jim only showed up around the end of that timeline for Freddie. They stayed true to what they said they were doing and to be truthful I highly doubt that anyone could have encapsulated the man that was Freddie Mercury. They did the best they can and honestly, I wholeheartedly believe that they have Freddie’s best interests in mind. Give props to the band, they lost him too. They definitely put a lot into the two hours they had and have readily admitted that had they had more time, more would have been included in their story.

#freddie mercury#bohemian rhapsody#bohemian rapsody movie#bohemian rhapsody movie#rami malek#bisexual#hiv aids#aids crisis#aids#brian may#roger taylor#john deacon#joe mazzello#gwilym lee#ben hardy#farrokh bulsara#glam rock#red ribbon#biopic#bi-erasure#queer#lgbtq community#lgbtq#lgbtpride#lgbtq pride

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Research Paper on ABC’s ‘General Hospital’

I have been watching soap operas since I was nine years old. Soap operas made me who I am today — they laid the foundation of my love for stories and real television beyond cartoons. Soap Operas are a foundational television genre in defining the television industry. Soap operas began on United States radio networks in the 1930 as the radio was being introduced to homes across the United States (Soukup). The early soap operas were fifteen minute daytime radio serials used to market products such as soap and other mainly feminine products, earning the name “soap opera”. The commercial sponsorship of soap operas is what formed the structure of advertiser-supported programming that we currently have on television today (Meyers). With the World War II over and television on the rise, broadcasting networks adapted their radio shows for television to meet the demands of the developing world (Soukup). The familiarity of soap operas from the radio is arguably said to have been one of the reasons audiences across the country were so easily able to change mediums from radio to television. By 1951, all three networks had their own soap operas. Into the 1960s and 1970s, more than 10 hours of network programming per day was dedicated to soaps and brought audience members over the 20 million mark. Once the 1980s arrived, soap opera ratings began to decline and more than ten soap operas have been cancelled since the 1990s, including iconic ABC soap operas like One Life to Live and All My Children in 2011. As of 2017, there are only four soap operas currently on broadcast television (Meyers). This is a shame. We don't value soap operas like we use to which is a loss to the culture of The United States because daytime soap operas focus on taboo social issues such as AIDS and abortion more than any other genre of television. Many people remember the iconic episode of Degrassi where a young girl gets an abortion. In fact, it was not aired in American during the early days of its airing in 2004. The N (a subsidiary channel of Viacom’s Nickelodeon now known as TeenNick) refused to air the controversial two-part episode until two and a half years later in August of 2006, when the actress ranked it her favorite episode and so the network had to air it (McDermott). But this wasn’t the first time abortion had been a featured storyline in United States television. The first abortion storyline on television took place on the soap opera Another World (Lane). This begs the question - If we talked about it all the way back then on daytime television, why can we still not talk about it today on primetime? Another World aired from 1964 to 1999 on NBC for 35 years. Pat Matthews’s boyfriend, Tom Baxter convinced Pat to have an illegal abortion in New York. Pat had the abortion and then developed an infection which left her able to have any children. Tom then revealed he never loved Pat, and she shot him. While on trial for murder, she fell in love with her attorney, John Randolph. In the 1970s, the writers of Another World had Pat have correctional surgery and she had twins (Newcomb). In 1973, Erica Kane (played by the iconic Susan Lucci) on All My Children had the first legal abortion on Daytime television before Roe vs. Wade was decided on. Erica had her abortion because she was a model and did not want to end her career. The storyline made headlines over its controversy of the reasoning to have an abortions — to maintain a career rather than due to health concerns. The storyline was perceived well by feminists and ratings rose from 8.2 to 9.1. These groundbreaking moments in women’s history proved daytime television dealt with complex social issues that were relevant to the mainly female audience and their sophistication (Jr., Kevin Mulcahy). In the 1990s, AIDS was still very underrepresented and stigmatized. Children were warned to stay away from people with HIV and AIDs and treated it like the common cold. Most people still didn’t even know all the facts about it or its symptoms — they just knew to be afraid. One of the first shows to ever feature a character with AIDS was Stone Cates in 1993. Stone was living with the iconic mobster, Sonny Corinthos, along with his brother, Jagger Cates. He then began dating Robin Scorpio. Their love story was called “epic” and “tragic”. Stone became sick with the flu and Robin took care of him. Robin, a volunteer at the hospital, asked Stone to get tested for HIV. Stone got tested a year prior and was HIV negative, so he did not take another test. Unfortunately, the test was only negative because he took it to close to exposure for the antibodies to come up. Robin and Stone then had unprotected sex. When Stone’s flu did not let up, he got tested and was diagnosed HIV positive. Once Stone was shot and got his blood on Robin’s hands, he confessed to her that he was HIV positive and his previous girlfriend had been a drug addict and could have possibly contracted HIV. Robin and Stone were tested again, where Robin tested negative and Stone was revealed to have AIDS. Later, Robin contracted the flu and tested HIV positive as well. When Stone died, he had gone blind, but asked Robin to stand by the window and the light. As Stone looked towards the light, he saw Robin one last time before he died. The actor, Michael Sutton, was nominated for an Daytime Emmy for his performance. Stone, although a very prominent character in General Hospital’s past, was only on the show for roughly two years from 1993-1995. Dr. Robin Scorpio-Drake, however, remains a very prominent recurring character on General Hospital to this very day since 1985. Robin’s storyline has been a wonderful example to those living with HIV that they can live healthy, fulfilling lives. Robin ends up getting married to Patrick Drake, having a healthy daughter named Emma and a son named Noah, and becoming a renowned doctor. Robin still often brings up Stone Cates, which is a rare occurrence for such a short lived character arc. Robin refers to Stone as her first love and the reason she became to pursue her career as a doctor. Robin’s story influenced thousands around America because thousands of people watched Robin grow up from a child into a teenager for almost ten years. The storyline of Robin becoming HIV positive was so important to viewers because she was a character no one wanted to see go — and uninformed people assumed HIV positive was a death sentence. Robin Scorpio-Drake’s legacy still lives on, giving hope to many others living with the disease. An after school special called Positive: A Journey Into AIDS aired December 7th, 1995 on ABC after General Hospital hosted by Kimberly McCullough and Michael Sutton, who played Robin and Stone respectively. The after school special was done as a documentary as the actors talked to real people living with HIV and AIDS to prepare them to do the part justice. The special also showed a press conference where a reporter asked Michael Sutton if he was nervous about being stereotyped as gay due to the abundance of gay and bisexual men affected by the disease. Sutton responded that he was heterosexual and comfortable with his sexual preferences, but remained challenged by the interviewer’s question. He spoke about how “pigeon-holed” AIDS and HIV are and that people want to stereotype it as a gay disease in order to downplay it (Harrington & Watkin). The after school special won two Emmys in 1996 (""ABC Afterschool Specials" Positive: A Journey Into AIDS (TV Episode 1995)"). This special was so important because it was a fictional weekly story talking about the making of the storyline and talking to people who truly had HIV and were living with it in order to better the fictional weekly material. The Nurses’ Ball was founded in 1994 as an event for the citizens of Port Charles to fundraise for HIV and AIDS awareness and research. The event stands as a catalyst for various different storylines because all the characters are put together in one place. The actors who portray citizens of Port Charles, New York perform song and dances. In 1996, once Robin was diagnosed with HIV, The Nurses Ball became personal for many characters, each donating money for the cause. Even beyond the characters in the show, the show itself has donated more than $109,000 to the nonprofit organization Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation since 1998. The Nurses Ball became a day to mark the nationwide Day of Compassion. In 1997, AIDS-infected actor Lee Mathis, who played a recurring lawyer on General Hospital, passed away weeks before the annual ball he helped stage. General Hospital then donated the royalties from Robin’s Diary, a book to go along with the storyline, and Nurse’s Ball t-shirts (Bidwell). In 2013 when the Nurses Ball was brought back on as a plot device, the soundtrack to each performance was released on iTunes. And I could not find any sources for this, but I’m sure that some of the royalties to toward the same AIDS foundations. Not only has General Hospital and other daytime serials spent their money and time from their small budget to portray complex social issues, but they also donate money to the outside real people who’s real life stories they are portraying. Celebrity Health Narratives and The Public Health notes, “Interracial romance, homosexuality, divorce, alcoholism, mental illness, unwanted pregnancy, abortion, impotence, addiction, incest, down syndrome, suicide, anorexia, HIV/AIDS, rape, adultery … you name it. Daytime has dealt with it. NO other form of entertainment as so effectively addressed social issues” (Christina S. Beck,, Stellina M.A. Chapman, Nathaniel Simmons, 135). Because soap operas air every weekday, they are able to tell their stories from a unique place of creating suspense everyday. Everyday there has to be a reason for you to turn in tomorrow. And every Friday there has to be a reason to turn in next week. They constantly have to create drama to fulfill the quota of airing almost 250 days out of the year. And to create drama, the writers of soap operas take real issues in society and bring them to the beloved characters we already know and love and grew up with. They use things like abortions and AIDS and HIV to create a lasting impact on characters who have a long history. For example, when Starr Manning from General Hospital lost her baby in a car crash, it was more painful because we as an audience had grown up watching Starr and the actress Kristen Alderson — she had become family. We watched her day in and day out 250 days out of the year. That’s more than I see my own family. So instead, soap opera families become family. That can’t happen on primetime television. Primetime shows are based around the formula of there being a problem that is solved for the most part within thirteen to twenty-one episodes. Soap operas, on the other hand, can have baby switches that last more than half the year. Soap operas air so often that storylines can be given proper timing — pregnant characters can be pregnant for nine whole months. Primetime television simply doesn’t have the time to create such a product based on interpersonal relationships rather than the actual drama itself. These issues have to be personalized and how do you personalize someone when their time on the air is so short? Soap operas, however, can get into the heart of personal-social problems. Personal- social problems “consist of extraordinary circumstances that affect individuals or individual units of society - usually, crises in relationships or health” (Thoman). These problems are about people, and only then become a societal problem after people begin to be affected. The AIDS epidemic being a prime example — people were not interested until it began to effect the people in their community that they cared about. Soap operas talk about the people and the people who are affected and are able to give their time and effort in portraying stories about people and their personal-social problems that audiences can relate to. In conclusion, it is a shame that we as an American society value primetime television more than daytime soap operas because the latter gets to talk about social injustice and real life issues such as AIDS and abortion to educate their viewers. I think that is is truly tragic that audiences are being aged out of daytime when back in their prime, the 1960s-1990s, people of all ages watched. College students were a main part of the age group — both males and females spend their time between classes glued to a television screen (Lemish). And it probably meant a lot more for young impressionable kids living with their parents stigmas about HIV to see teenagers living with the disease. When I started watching One Life to Live in fourth grade, it was because I fell in love with pregnant sixteen year old Starr Manning and her high school friends. I fell in love with the character Shane Morasco and the question of who his father was. I fell in love with the missing baby Sam storyline. It was the storylines about children and teens that attracted a young Nieve to tune in tomorrow. I truly believe that if soap operas put their time and effort into teenage characters again, they will see a resurgence of young fans, especially if the storylines have to do with the social climate of Trump’s United States. Society is begging for a progressive genre on television, and I hope that they soon learn that it has been here all along, waiting, during the day rather than at night.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

It’s no surprise that after the death of former president George H.W. Bush we’re seeing media pundits, advocates and popular historians promote a rosy view of his tenure as president. In the era of Donald Trump, there’s a tendency to portray every Republican leader of the past in a nostalgic, sugar-coated way.

The first thing that caught my eye was a report on CNN’s website that included a tweet from the president of Covenant House, a charity that runs shelters across the U.S. for homeless youth and which has a historical connection to the Catholic Church. The tweet included photos of the former president and the late first lady Barbara Bush hugging children, implying that Bush was an important advocate for people with AIDS.

Perhaps that was what Bush “believed,” but it was far from the truth. Bush was as captive to the evangelical right on social issues — and thus a decidedly Republican president — as was his predecessor, Ronald Reagan, who cultivated religious conservatives as a potent political force and bowed to their anti-LGBTQ agenda as the AIDS epidemic mushroomed in the 1980s.

Reagan’s history of callously ignoring the epidemic while thousands died is well-documented. Bush, at the outset of his term, promised a “kinder, gentler” presidency than the man he’d served under as vice president. He even gave a speech on the AIDS epidemic in 1990, which was long on compassion but short on strategy and commitment to funding. During the speech, in fact, Urvashi Vaid, an invited guest and then the executive director of the prominent National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, now the National LGBTQ Task Force, took the unprecedented and heroic act of standing up and holding a sign, “Talk Is Cheap. AIDS Funding Is Not.”

Bush, in the end, bowed to the same extremists Reagan did when it came to AIDS and LGBTQ rights. As The Washington Post noted, Bush allowed evangelicals to mature as a movement within the GOP after Reagan brought them in, rather than pushing back.

Bush did sign the Americans With Disabilities Act, which protected people with disabilities against discrimination, including people with HIV. And he signed 1990′s Ryan White Care Act — after it passed overwhelmingly in Congress — which federally funded treatment for AIDS for people with little resources. But it took years of work by the indefatigable Democrats Sen. Edward Kennedy and Rep. Henry Waxman, and was too little, too late. By that point, nearly 10 years into the epidemic, 150,000 cases of people with HIV had been reported in the U.S., and 100,000 people had died due to AIDS.

Bush’s administration still dragged its feet on drug treatment and refused to address prevention to the most affected community, gay and bisexual men, which it could have done by simply promoting and funding critical safer sex programs and condom distribution. When ACT UP, the AIDS activist group, targeted Bush in actions at the White House and at his Kennebunkport, Maine, summer retreat, Bush said “behavioral change” was the best way to fight the disease.

Infamously, Bush had said in a television interview that if he had a grandchild who was gay he would “love” the child but would tell the child he wasn’t normal. And like Reagan, he stocked his Cabinet with anti-gay zealots. Health Secretary Louis Sullivan, also protested by ACT UP for his terrible response to HIV, joined forces with evangelical leaders to cover up a government-funded study on teen suicide that found LGBTQ teens were at much higher risk.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bWbzinqIlPk

While Bush signed the Hate Crimes Statistics Act in 1990, which allowed for collecting data on anti-gay hate crimes in addition to other hate-motivated crimes, and signed a measure that struck “sexual deviation” from an immigration law used to ban LGBTQ immigrants, he took a hard turn to the far right when conservative commentator and former Reagan aide Pat Buchanan scared him with a strong challenge in the 1992 Republican primaries.

Bush eventually joined anti-gay attacks on the National Endowment for the Arts that had originated with right-wing members of Congress over the agency’s funding of queer artists, and put in place an acting chairwoman who defunded gay and lesbian film festivals. That same year, Bush signed a bill to stop the Washington, D.C., Council, a body that Congress can ultimately overrule, from offering health care benefits to domestic partners of gay and lesbian city workers.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Copypasta from @zestychille OMG IDK if everyone here gets the Roy Cohn joke in this. Y’all might be too young, or unlearned, and that is ok, but it’s time to learn some gay history. Roy Cohn was known for being a bad man. He was Donald Trump’s Lawyer, but he had MANY even more prominent roles to be remembered. Roy Cohn was a lawyer in the McCarthy Hearings accusing people of being communists during the red scare 2 electric boogaloo. He was one of the most despicable lawyers I have ever heard of, and he helped the government bully an amazing amount of people. They were convicted of being treasonous if found guilty of being communists or communist sympathizers/etc. They targeted liberals, gays, etc. And Roy Cohn secretly fucked men, while making it his life’s work condemning people who would have saved him if the roles were reversed. His life wasn’t all glamour, but he REALLY played the wrong side. Roy Cohn helped get RAEGAN elected in the first place, to champion his fight against the gays. Eventually his train would kick him off though, as he got DISBARRED for being a scumbag who did shit like physically forcing people to sign documents.(among other BS) He lost everything, and it was quite the scandal. Then they figured out he had AIDS when he had to seek treatment, and he died of related complications soon after1. He had been hiding it as long as he could. Him dying of aids was a BIG deal, because if someone regarded by republicans as so influential and mighty for their cause could have been a filthy homosexual the whole time, why then ANYONE could be gay. It was almost as if some people were BORN that way. WHOA. They had never really given that idea any thought, and many of them still deny it. It didn’t save the gay community form the aids crisis, not at all. But it DID play a part RUINING Roy Cohn’s name just before he died of a disease that was disproportionately stigmatized at the time. So when you see Roy Cohn with a communist flag, it’s a big part FUCK YOU ROY COHN YOU LITERAL OOZING PUSTULE OF A HUMAN BEING, and a little part, YOU SHOULD HAVE BEEN THERE FOR US ROY COHN YOU STUPID PILE OF SHIT, and a little part, YOU WERE ONE OF US EVEN IF YOU DENIED IT AND YOU COULD HAVE HAD A HOME WITH US IF YOU HADN’T BEEN AN ABSOLUTE SACK OF GARBAGE ROY COHN. Because in the end, Roy Cohn was a gay man who let himself become the scourge of his own people. He spent his life unhappy, both being bullied, and bullying others even harder. And if he had stayed true to his heart and been openly gay, OR EVEN JUST NOT OUTWARDLY ANTI GAY, he not only may have found a better life, but he would have saved the lives of countless people who were condemned due to his championing of hate. This has been a lesson in history some of us let be erased.

AIDS quilts

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Systemic Response to AIDS and Reagan's Failure

The 80’s was not a good time to have an epidemic. Ronald Reagan was elected into office in 1981, the beginning of the AIDS crisis. When everything started to break out, the Center of Disease Control, or the CDC, noticed patterns in the virus affecting two prominent groups: gay men and drug users (Francis). The CDC then was preparing how to handle such a virus, however, the head director of the CDC at the time had very close ties to the Reagan administration. This would not have been any issue if it hadn’t been for the fact that “...Reagan himself did not understand the seriousness of AIDS…” (Francis). Very little action was taken to control the virus. The afflicted had to endure the administration and CDC do nothing to stop the deadly disease, while thousands were soon to become infected. Many people would point to the CDC’s failure to respond, but it was in fact the governmental control that ultimately failed America. The CDC, “was very capable of responding, as it has done with innumerable disease outbreaks before and since. But with AIDS, the Reagan administration prevented it from responding appropriately to what very early on was known to be an extremely dangerous transmissible disease” (Francis). Speculation about why this was rampant, but of course it was because of the homophobia that the disease brought with it. The CDC even concocted a prevention plan that would inform the masses of what to expect from the virus, how to prevent it, and other guidelines that follow what the CDC have done in the past with other similar diseases. However, “he nation's first AIDS prevention plan worked its way up the administrative channels to the highest levels of the Department of Health and Human Services, and got rejected (Francis). This inaction led to the death of thousands of innocent Americans, and yet this event did not leave a large stain on Ronald Reagan's presidency.

Despite one of the largest displays of avoidance and ignorance in the government, Reagan is deemed to be one of America’s greatest presidents. This is very similar to how his presidency is treated relating to mistreatment of African Americans. Other than making very racist claims throughout his presidency, Reagan also firmly opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in the beginning of his career and was also opposed to the 1965 Voting Rights Act, one of the most important legislation in civil rights history (“Black America”). Ronald Reagan was a white, conservative president that did not care about the well being of marginalized people.

AIDS primarily affecting gay men was the main reason that so many died in the epidemic. Had it affected straight, christian, white men in the same way, there would have probably been five different amendments passed for victims of the disease. Maybe if Reagan labeled the virus as communist, there would have been at least some action taken. A strong government should be able to take care of their government, and the Reagan administration left a bad mark on American history.

Works Cited

“Black America Has Overlooked the Racist Policies of Ronald Reagan.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 64, 2009, pp. 13–14. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40407458. Accessed 12 Dec. 2020.

Francis, Donald P. “Commentary: Deadly AIDS Policy Failure by the Highest Levels of the US Government: A Personal Look Back 30 Years Later for Lessons to Respond Better to Future Epidemics.” Journal of Public Health Policy, vol. 33, no. 3, 2012, pp. 290–300. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23253449. Accessed 12 Dec. 2020.

0 notes

Text

Pandemic Fears: What the AIDS Battle Should Teach Us About COVID-19

By ANISH KOKA, MD

As the globe faces a novel, highly transmissible, lethal virus, I am most struck by a medicine cabinet that is embarrassingly empty for doctors in this battle. This means much of the debate centers on mitigation of spread of the virus. Tempers flare over discussions on travel bans, social distancing, and self quarantines, yet the inescapable fact remains that the medical community can do little more than support the varying fractions of patients who progress from mild to severe and life threatening disease. This isn’t meant to minimize the massive efforts brought to bear to keep patients alive by health care workers but those massive efforts to support failing organs in the severely ill are in large part because we lack any effective therapy to combat the virus. It is akin to taking care of patients with bacterial infections in an era before antibiotics, or HIV/AIDS in an era before anti-retroviral therapy.

It should be a familiar feeling for at least one of the leading physicians charged with managing the current crisis – Dr. Anthony Fauci. Dr. Fauci started as an immunologist at the NIH in the 1960s and quickly made breakthroughs in previously fatal diseases marked by an overactive immune response. Strange reports of a new disease that was sweeping through the gay community in the early 1980’s caused him to shift focus to join the great battle against the AIDS epidemic.

The first reported cases of AIDS were reported in the United States in the 1981 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 5 young men, all previously healthy and all active homosexuals were found to have Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, a disease that prior had been restricted to the severely immunocompromised. An avalanche of clinical reports subsequently woke the nation to a disease that appeared to have a predilection for the gay community. The remarkable subsequent successes of medical therapies that followed to make AIDS a manageable disease to grow old with are now a matter of history, but in the early years this success seemed anything but inevitable.

The charge leveled against the establishment of the day by a public becoming aware of the tragedy of young, previously healthy individuals dying by the thousands was that there was an attempted cover up of a ‘dirty’ disease in a community America would rather not talk about. But from the first description of the disease by the medical community, the activity in the research industry (both public and private) was intense. It took 2 years for two labs to simultaneously identify the HIV virus that appeared responsible for the development of AIDS. Elaborating the mechanism by which the virus destroyed the body’s immune system lead to the discovery of potential therapies.

The first drug therapy with the most promise was AZT, or azidothymidine. Remarkably this wasn’t a drug that was developed from scratch, it had been developed in the 1960’s by a US researcher to battle cancer. The drug failed in mice and was set aside. The problem with the drug wasn’t that it was ineffective, but that it was a solution without a problem. The drug was targeted to retroviruses that affected humans, but at the time of its development, there were no important retroviruses infecting humans.

The HIV virus turned out to be the problem AZT had been in search of. HIV’s genetic information lives in a single strand of RNA that requires an enzyme called reverse trancriptase to transform into a double stranded DNA which then integrates into the host cell. AZT is a thymidine analogue that works by selectively inhibiting the reverse transcriptase enzyme. The company that had AZT, Burroughs-Wellcome, used the agent successfully in an animal model of a retrovirus surrogate, but that was not a specific model for HIV infection. Fortuitously, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) had a model of immune cells (CD4) that they had developed to use as an antiviral assay for potential HIV therapies. AZT was one of a promising group of drugs Burroughs-Wellcome sent to the NCI. The in-vitro results were impressive. The HIV virus was unable to infect the CD4 cells in the presence of AZT.

The year was 1985. It had taken four years since the first clinical report of the disease by the CDC to find a promising drug. The time was intense. There were 20,000 reported cases, and as many as a million people believed infected but asymptomatic. Doctors were helpless, serving as witnesses to the eventual progression to death, rather than agents that could alter the the natural history of the disease.

AIDS hospices were set up. It was a terrible time, encapsulated by a haunting picture taken of AIDS activist David Kirby as he lay near death, cradled in his father’s arms. It turns out that diagnosing a disease with no cure is its own desperate malady.

Identifying a drug that works in a lab was progress, but at the time, the FDA’s usual timeline for a drug to be judged safe and effective enough to be used in patients was 8-10 years. Under intense pressure, the FDA fast-tracked everything. A phase 1 trial where the drug was injected into healthy volunteers to test for safety suggested symptoms at high doses, but a tolerable safety profile. The next step mandated by the FDA was a double blind randomized control trial in patients with AIDS. This meant half of the patients in the trial would get a placebo drug, while the other half would get AZT. The trial was terminated early when 19 patients died in the placebo arm, but only 1 died in the AZT arm. The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1987, six years after the first clinical report of AIDS, and rapidly approved by the FDA panel in the same year.

The trial was criticized for its early termination, and the entire fast-track process was challenged by skeptics who felt the FDA shouldn’t have bent to the wishes of activists.

Fauci was asked about pressure from activists and responded positively.

“No, actually it is difficult to say what was the right or wrong thing to do. It was a situation where there was only one drug available–it was not like trying out one amongst many antibiotics–and the activist community and the constituents were suffering. They demanded that they have access to anything that could give them even a little hope. Pressure was put on the FDA. They responded appropriately for rapid expedited approval of AZT, making drugs available that normally would not have been available for years and years.”

He went on to note that the British were able to complete a long term 3 year study of AZT that could never have been completed in the United States that showed no long term benefit. Apparently AZT blessed patients with a brief reprieve, not a long term cure. The investigators at the time had no way of knowing that the HIV virus mutated in response to the initial single agent therapy and eventually became resistant to the drug. The initial doses used were also very high, and caused patients a number of well described side effects. Investigators since have learned to use lower doses of the drug to avoid the toxicities that plagued patients in the early years.

Many in the scientific community were upset with the early approval of AZT, and prominent critics emerged comparing the drug to aspirin, as well as alleging financial interest in the drug approval. The activists in the United States that pressured the scientific community were eventually proven right. The desperation of the dying patients in the early years is well represented in the movie starring Matthew McConaughey – The Dallas Buyers Club. Unwilling to be randomized to the placebo arm of the AZT trial, the character played by McConaughey flees to Mexico, only to be prescribed a cocktail of vitamins by an unlicensed expatriate US doctor. The movie butchers the actual history by constructing the well-worn conspiracy narrative of a pharmaceutical company terminating a trial early to foist a dangerous drug (AZT) onto the public. What’s correct is that the community wanted hope in the form of some drug, and every day that a therapy was delayed was paid in lives lost. Ultimately the public pressure to get AZT out into the community was the right decision. A longer trial may very well have been negative, and subsequent non-approval may very well have confined the use of the drug to Mexican black market clinics and unlicensed doctors until the biology of the virus was better understood. There would have been no winners in that scenario.

There are important lessons to heed as the global biotech community races to cure doctors of their impotence when faced with a patient dying of the COVID-19 virus. Once a drug proves promising in-vitro, the same FDA will stand guard. Randomized control trials are planned to test these drugs for efficacy against the novel coronavirus. The emergency will certainly lubricate the timeline of approval just as it did with the AIDS epidemic, but a great deal of caution is to be advised in designing and interpreting trials where the patients range from mild symptoms with recovery with no intervention, to severely ill in intensive care units. Use a novel therapy too late, and a drug effective when used earlier may look ineffective. Used too early in the process, and any positive effect may be washed away by the mild natural history of the disease in most.

Part of the discomfort for the medical community lies in an aversion to dead ends in these battles. But as any detailed analysis of medical progress will clarify – the forward march of science is messy. Thalidomide, the drug responsible for the FDA as we now know it, eventually found use in patients with multiple myeloma.

The current approach is also paternalistic to the extreme. Patients dying of their disease may choose to enter a randomized control trial where they have a 50% chance of being placed on a “sugar pill”. But I question the ethics of denying patients an active drug unless they choose to enter this flip-of-a-coin lottery. As Fauci himself noted, the AIDS fight taught the NIH the importance of working with the community.

“When the gay activists were demonstrating, predominantly against the FDA but also against the NIH, and being very strident in their criticism, I challenged them. I said, “Okay, come on in, sit down, and let’s talk about it. What is it that you want?” That was when we developed relationships with them that are now very productive. We have activists who are important members of our advisory councils. We consult back and forth with them all the time. AIDS changed the way we do business at NIH in that, when appropriate, the constituencies play a major role in some of the policy and decision-making processes. You cannot just cave in and let people tell you how to do science the wrong way, but there is a lot you can learn from understanding how the disease is affecting a particular population, somewhat removed from the bench, and removed from the “ivory towers” that we have here.”

Science turns out to be an imperfect war waged with many casualties. Patients aren’t soldiers to be conscripted into this war. If people are to die, they deserve agency if they are to be part of the scientific enterprise. Patients and their doctors deserve the right to choose paths that end up being dead ends. Our job as doctors shouldn’t be to lean into the dichotomonia of positive and negative randomized control trials that frequently guides FDA approval. The AIDS struggle shows the chinks in the armor of the regulatory framework that keeps us safe, but in doing so risks keeping us from effective therapies. While it shouldn’t take grave threats of the scale of AIDS and COVID19 to lower barriers to treatments, it would be stupidity on the scale of the current pandemic to not adapt regulatory barriers to the problems faced.

What the world needs months ago is a therapy for patients stricken with COVID19. This would completely alter the public health response. No need to self quarantine, little need to test the mildly symptomatic since most get better, and cruises would become great again. A COVID-19 illness would prompt the same response as someone found to be actively ill with tuberculosis – not fun for close contacts, but no chance 16 million people would wake up in Italy to a quarantine.

The story of AIDS is a story of human ingenuity that should inspire hope for the COVID-19 pandemic. Effective therapies will take time. Patients will die, but the deaths will not be in vain. Skeptics will rightly cast doubt on claims of success. They will be right most of the time. Regulatory frameworks will be appropriately challenged by the desperate. Conflicts of interest will be raised to question data. The process will be messy and documented in a hypercritical manner by the Monday-morning journalists of the day. It will seem hopeless. But we will prevail despite the long odds because in the end, it will be those that remember the patients at the center of the storm that will show us the way forward.

It is always darkest just before the dawn.

Anish Koka is a cardiologist in practice in Philadelphia. He can be reached on Twitter @anish_koka

The post Pandemic Fears: What the AIDS Battle Should Teach Us About COVID-19 appeared first on The Health Care Blog.

Pandemic Fears: What the AIDS Battle Should Teach Us About COVID-19 published first on https://venabeahan.tumblr.com

0 notes

Text

Pandemic Fears: What the AIDS Battle Should Teach Us About COVID-19

By ANISH KOKA, MD

As the globe faces a novel, highly transmissible, lethal virus, I am most struck by a medicine cabinet that is embarrassingly empty for doctors in this battle. This means much of the debate centers on mitigation of spread of the virus. Tempers flare over discussions on travel bans, social distancing, and self quarantines, yet the inescapable fact remains that the medical community can do little more than support the varying fractions of patients who progress from mild to severe and life threatening disease. This isn’t meant to minimize the massive efforts brought to bear to keep patients alive by health care workers but those massive efforts to support failing organs in the severely ill are in large part because we lack any effective therapy to combat the virus. It is akin to taking care of patients with bacterial infections in an era before antibiotics, or HIV/AIDS in an era before anti-retroviral therapy.

It should be a familiar feeling for at least one of the leading physicians charged with managing the current crisis – Dr. Anthony Fauci. Dr. Fauci started as an immunologist at the NIH in the 1960s and quickly made breakthroughs in previously fatal diseases marked by an overactive immune response. Strange reports of a new disease that was sweeping through the gay community in the early 1980’s caused him to shift focus to join the great battle against the AIDS epidemic.

The first reported cases of AIDS were reported in the United States in the 1981 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 5 young men, all previously healthy and all active homosexuals were found to have Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, a disease that prior had been restricted to the severely immunocompromised. An avalanche of clinical reports subsequently woke the nation to a disease that appeared to have a predilection for the gay community. The remarkable subsequent successes of medical therapies that followed to make AIDS a manageable disease to grow old with are now a matter of history, but in the early years this success seemed anything but inevitable.

The charge leveled against the establishment of the day by a public becoming aware of the tragedy of young, previously healthy individuals dying by the thousands was that there was an attempted cover up of a ‘dirty’ disease in a community America would rather not talk about. But from the first description of the disease by the medical community, the activity in the research industry (both public and private) was intense. It took 2 years for two labs to simultaneously identify the HIV virus that appeared responsible for the development of AIDS. Elaborating the mechanism by which the virus destroyed the body’s immune system lead to the discovery of potential therapies.

The first drug therapy with the most promise was AZT, or azidothymidine. Remarkably this wasn’t a drug that was developed from scratch, it had been developed in the 1960’s by a US researcher to battle cancer. The drug failed in mice and was set aside. The problem with the drug wasn’t that it was ineffective, but that it was a solution without a problem. The drug was targeted to retroviruses that affected humans, but at the time of its development, there were no important retroviruses infecting humans.

The HIV virus turned out to be the problem AZT had been in search of. HIV’s genetic information lives in a single strand of RNA that requires an enzyme called reverse trancriptase to transform into a double stranded DNA which then integrates into the host cell. AZT is a thymidine analogue that works by selectively inhibiting the reverse transcriptase enzyme. The company that had AZT, Burroughs-Wellcome, used the agent successfully in an animal model of a retrovirus surrogate, but that was not a specific model for HIV infection. Fortuitously, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) had a model of immune cells (CD4) that they had developed to use as an antiviral assay for potential HIV therapies. AZT was one of a promising group of drugs Burroughs-Wellcome sent to the NCI. The in-vitro results were impressive. The HIV virus was unable to infect the CD4 cells in the presence of AZT.

The year was 1985. It had taken four years since the first clinical report of the disease by the CDC to find a promising drug. The time was intense. There were 20,000 reported cases, and as many as a million people believed infected but asymptomatic. Doctors were helpless, serving as witnesses to the eventual progression to death, rather than agents that could alter the the natural history of the disease.

AIDS hospices were set up. It was a terrible time, encapsulated by a haunting picture taken of AIDS activist David Kirby as he lay near death, cradled in his father’s arms. It turns out that diagnosing a disease with no cure is its own desperate malady.

Identifying a drug that works in a lab was progress, but at the time, the FDA’s usual timeline for a drug to be judged safe and effective enough to be used in patients was 8-10 years. Under intense pressure, the FDA fast-tracked everything. A phase 1 trial where the drug was injected into healthy volunteers to test for safety suggested symptoms at high doses, but a tolerable safety profile. The next step mandated by the FDA was a double blind randomized control trial in patients with AIDS. This meant half of the patients in the trial would get a placebo drug, while the other half would get AZT. The trial was terminated early when 19 patients died in the placebo arm, but only 1 died in the AZT arm. The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1987, six years after the first clinical report of AIDS, and rapidly approved by the FDA panel in the same year.

The trial was criticized for its early termination, and the entire fast-track process was challenged by skeptics who felt the FDA shouldn’t have bent to the wishes of activists.

Fauci was asked about pressure from activists and responded positively.

“No, actually it is difficult to say what was the right or wrong thing to do. It was a situation where there was only one drug available–it was not like trying out one amongst many antibiotics–and the activist community and the constituents were suffering. They demanded that they have access to anything that could give them even a little hope. Pressure was put on the FDA. They responded appropriately for rapid expedited approval of AZT, making drugs available that normally would not have been available for years and years.”

He went on to note that the British were able to complete a long term 3 year study of AZT that could never have been completed in the United States that showed no long term benefit. Apparently AZT blessed patients with a brief reprieve, not a long term cure. The investigators at the time had no way of knowing that the HIV virus mutated in response to the initial single agent therapy and eventually became resistant to the drug. The initial doses used were also very high, and caused patients a number of well described side effects. Investigators since have learned to use lower doses of the drug to avoid the toxicities that plagued patients in the early years.

Many in the scientific community were upset with the early approval of AZT, and prominent critics emerged comparing the drug to aspirin, as well as alleging financial interest in the drug approval. The activists in the United States that pressured the scientific community were eventually proven right. The desperation of the dying patients in the early years is well represented in the movie starring Matthew McConaughey – The Dallas Buyers Club. Unwilling to be randomized to the placebo arm of the AZT trial, the character played by McConaughey flees to Mexico, only to be prescribed a cocktail of vitamins by an unlicensed expatriate US doctor. The movie butchers the actual history by constructing the well-worn conspiracy narrative of a pharmaceutical company terminating a trial early to foist a dangerous drug (AZT) onto the public. What’s correct is that the community wanted hope in the form of some drug, and every day that a therapy was delayed was paid in lives lost. Ultimately the public pressure to get AZT out into the community was the right decision. A longer trial may very well have been negative, and subsequent non-approval may very well have confined the use of the drug to Mexican black market clinics and unlicensed doctors until the biology of the virus was better understood. There would have been no winners in that scenario.

There are important lessons to heed as the global biotech community races to cure doctors of their impotence when faced with a patient dying of the COVID-19 virus. Once a drug proves promising in-vitro, the same FDA will stand guard. Randomized control trials are planned to test these drugs for efficacy against the novel coronavirus. The emergency will certainly lubricate the timeline of approval just as it did with the AIDS epidemic, but a great deal of caution is to be advised in designing and interpreting trials where the patients range from mild symptoms with recovery with no intervention, to severely ill in intensive care units. Use a novel therapy too late, and a drug effective when used earlier may look ineffective. Used too early in the process, and any positive effect may be washed away by the mild natural history of the disease in most.

Part of the discomfort for the medical community lies in an aversion to dead ends in these battles. But as any detailed analysis of medical progress will clarify – the forward march of science is messy. Thalidomide, the drug responsible for the FDA as we now know it, eventually found use in patients with multiple myeloma.

The current approach is also paternalistic to the extreme. Patients dying of their disease may choose to enter a randomized control trial where they have a 50% chance of being placed on a “sugar pill”. But I question the ethics of denying patients an active drug unless they choose to enter this flip-of-a-coin lottery. As Fauci himself noted, the AIDS fight taught the NIH the importance of working with the community.

“When the gay activists were demonstrating, predominantly against the FDA but also against the NIH, and being very strident in their criticism, I challenged them. I said, “Okay, come on in, sit down, and let’s talk about it. What is it that you want?” That was when we developed relationships with them that are now very productive. We have activists who are important members of our advisory councils. We consult back and forth with them all the time. AIDS changed the way we do business at NIH in that, when appropriate, the constituencies play a major role in some of the policy and decision-making processes. You cannot just cave in and let people tell you how to do science the wrong way, but there is a lot you can learn from understanding how the disease is affecting a particular population, somewhat removed from the bench, and removed from the “ivory towers” that we have here.”