#ancient female poets and historical literature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Enheduanna, the World's First Author Known by Name

This lesson introduces students to Enheduanna, an important but lesser-known female poet and her contributions to literature and history. Students will also consider how the role of women in history might change in various times and locations.

Complete Lesson

One class period needed. It could be the first of a three-period sequence on ancient female poets, utilizing all three parts of the World Poetry Day video.

Essential Questions

Who was Enheduanna?

What contributions did she make to Ancient Mesopotamia?

Objectives

Improve reading fluency and comprehension of an encyclopedia article

Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media

Examine historical artifacts

Includes

Lesson plan

Worksheet

Map

Illustrations

Answer keys

Continue reading...

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some of my favourite terminology for sex, sexuality, and gender that have mostly fell out of use:

Sapphist: Similar to the term Sapphic which is still in use, derived from the woman loving Greek poet Sappho. The -ist has implications of doing rather than being. A Sapphist is a woman who has romantic and sexual relationships with other women. It was commonly used in the 19th and early 20th century, eventually replaced by lesbian in common usage. Some famous historical figures who used this term include Vita Sackville-West, who also used the terms lesbian and homosexual.

Mukhannathun: Translates roughly to "effeminate ones" or "ones who resemble women", typically refers to a feminine male, an intersex person, or one whose sex is indistinct. Modern scholars place the term Mukhannath in correlation with trans feminine. Mukhannathun traditionally took on the social roles of women in Saudi Arabia and feature in Ḥadīth Islamic literature. They were often musicians and entertainers, Abū ʿAbd al-Munʿim ʿĪsā ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Dhāʾib (or Tuwais) being perhaps the first famous Mukhannath musician. I could not find any depictions of Mukannathun.

Invert: Sexology in the early 20th century believed that same sex desire and cross gender identification were natural in some people. It was coined in German by Karl Friedrich Otto Westphal (1833-1890) and translated across Europe and eventually into English as sexual inversion by John Addington Symonds Jr. (1840-1893) in 1883. Inverts were people whose natural sex instinct (heterosexual, cisgender) were "inverted", causing a natural desire for the same sex or to live as the other sex. It was thought that most inverts desired a relationship with a "normal" member of their own sex, for example a masculine presenting woman would desire a feminine presenting "normal" woman, a feminine presenting man would desire a masculine or "normal" man. While most sexologists thought sexual inversion was natural, they worried about corruption of "normal" people by inverts. The writer 'John' Radclyffe Hall (1880-1943) identified as an invert and explored the life of inverts in her 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness.

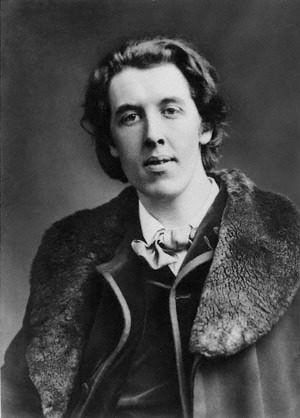

Uranism: A Uranian was a man who was romantically or sexually interested in other men. One of the earliest records of the term comes from Friedrich Schiller's 'Sixth Letter' in the Aesthetic Education of Man in 1795. It is derived from the ancient Greek goddess Aphrodite Urania, a manifestation of Aphrodite who was free of physical desire and instead was attracted by mind and soul. Ancient Greek literature was very important in the early formations of queer identity and self-recognition. Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) was known to use the term Uranian.

Tribadism: Derived from the Greek "tribas" which means "to rub", tribadism denotes both a sexual position (now known as tribbing or scissoring) and a woman who seeks to sexual dominate and/or penetrate another woman. This term could also be used to describe an intersex person who lives as female and is the penetrating partner during sex with women. It became the most common word to describe any kind of sexual intimacy between women in English literature from the 16th to 19th centuries. Marie Antoinette, queen of France from 1773 to 1792 was "defamed" in many anti-monarchist newspapers as being a tribade.

Eonism: Eonism was coined by English sexologist Havelock Ellis (1859-1939) to describe cross gender identification and presentation. "Eon" after the French diplomat Charlotte-Geneviève-Louise-Augusta-Andréa-Timothéa d'Éon de Beaumont, who was assigned male at birth but lived as a woman from 1777 until her death in 1810. Eonism was later replaced by transvestism in popular usage in the early to mid 20th century, coined by Magnus Hirschfeld (1868-1935) in 1910.

Eunuch: the term Eunuch has many connotations but the one common factor that almost all definitions share is that a eunuch is an intentionally castrated male. Eunuchs can also be uncastrated, but put into the social role as eunuch due to their 1) feminine presentation 2) inability to procreate 3) attraction to men. Eunuchs were not seen as men in most cultures, they were specifically chosen and castrated in order to fill a specific, separate social role from men and women. It was sometimes punitive, for example under Assyrian law men who were caught in sexual acts with other men were castrated. Eunuchs often had positions in royal households in the Ancient Middle East, their sexlessness was seen to enhance their loyalty to the crown as they were less likely to be distracted by sex or marriage, and it also allowed for jobs to be given on merit, and not inherited since Eunuchs could not reproduce. In Ancient Greece certain sects of male priests were eunuchs. China had Eunuchs who were fully castrated (penis and testicles) and high ranking in imperial service. In Vietnam, many eunuchs were self castrated in order to gain employment in the royal households.

Homophile: coined in 1924 by Karl-Günther Heimsoth (1899-1933) in his dissertation Hetero- und Homophilie. The term was in common use in the 50s and 60s in gay activism groups. It was an alternative to homosexual coined in 1868 by Károly Mária Kertbeny (1824-1882) which was thought to have pathological and sexual implications, whereas homophile prioritised love and appreciation over the sex act or pathology. It is still in use in some parts of northern Europe. The Homophile Action League was founded by lesbian couple Ada Bello (1933-2023) and Carole Friedmann (1944-?) in Pennsylvania, U.S.A. in 1968, a year before the Stonewall Riots.

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emily Windsnap characters name meaning

Emily: The Latin origin of the name Emily comes from the feminine version of "Aemilius," "Aemilia." Emily is frequently understood to mean "eager" or "rival." (which matches Emily's spirit of adventure and competes with the competition between her and Mandy.) Throughout history, Emily has been a popular name, especially in literature. Emily Dickinson, a significant American poet renowned for her distinct style and contemplative subjects, is one of the notable individuals. Emily Brontë, the author of the beloved book "Wuthering Heights," is another important person. I always have head-canon books that have Emily writing her own biography about her adventures, demonstrating her love of English. Emily turns into a writer and author.) "In some folklore traditions, names carry specific meanings or attributes that influence a person’s destiny. While not directly tied to any mythological tales about an individual named Emily, it can be said that those who bear this name may be seen as destined for creativity or leadership roles based on historical associations."

Last name Windsnap: Wind, a symbol of freedom and movement, is often personified in mythologies as a powerful force. The term "windsnap" implies quickness or suddenness, suggesting agility. These themes are often used in creative works to evoke imagery and character identifiers, enhancing world-building.

Mary P: In the Bible, the name Mary is most prominently associated with Mary, the mother of Jesus. The name itself is derived from the Hebrew name Miriam, which carries meanings such as “beloved,” “bitter,” or “rebellious.” (Mary, being Emily's mother, gave birth to the hero of the story, Emily. She also seemed to be rebellious and free-spirited when she was younger, meeting Jake, her being "beloved by Jake," and bitter about her fear of water because of the memory drug losing her husband for 12 years.) The name Penelope may derive from the Greek word “penelops,” which translates to “duck” or refers to a type of waterfowl that was sacred to the Ancient Greeks. This connection to waterfowl could symbolize adaptability and nurturing qualities. Another interpretation suggests that it comes from the Greek roots “pene,” meaning “web,” In the Odyssey, Penelope embodies loyalty and patience. Similar to Penelope’s unwavering loyalty to Odysseus during his long absence, Mary P demonstrates loyalty to her friends throughout the series. While Penelope waits for Odysseus, cleverly navigating challenges posed by suitors, both Penelope and Mary P represent aspects of female agency within their respective narratives. Penelope’s intelligence is highlighted through her cunning plans.

Jake: Much like biblical Jacob’s loyalty to his family (despite his initial deceit), Jake Windsnap demonstrates unwavering support for Emily throughout their adventures. fluidity, and emotional depth—qualities that resonate with the essence of the name Jake. The connection to water aligns with mythological interpretations where water often symbolizes transformation.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is Sapphic Poetry?

Sapphic poetry, named after the ancient Greek poet Sappho, is a distinctive and influential form of poetry that originated in the 6th century BCE. It is characterized by a particular meter known as the “Sapphic stanza,” which combines lines of various lengths and rhythmic patterns to create a lyrical, flowing style. Sappho’s poetry, often focused on themes of love, desire, and personal reflection, has had a profound impact on Western literary traditions and continues to inspire poets today.

This article explores the origins of Sapphic poetry, its defining characteristics, its influence on later poets, and the ways in which contemporary writers have interpreted and adapted the Sapphic form. We will also examine the life of Sappho, whose works form the foundation of this poetic tradition, and discuss how her unique voice shaped the development of this genre.

The Origins of Sapphic Poetry

Sapphic poetry takes its name from Sappho of Lesbos, one of the earliest known female poets in Western literature. Sappho lived on the island of Lesbos in Greece during the 6th century BCE. Little is known about her life, but her poetry has survived in fragments, and she is often regarded as one of the greatest lyric poets of ancient Greece.

Her work is known for its emotional depth and personal nature, often focusing on the themes of love, passion, and longing. Sappho wrote in a dialect of ancient Greek known as Aeolic, and much of her poetry was meant to be sung, accompanied by the lyre. Her influence has been so profound that the term “Sapphic” not only refers to her specific style of poetry but also to themes of female homoeroticism, given the nature of many of her surviving works.

Who Was Sappho?

While much of Sappho’s biography is speculative, historical sources suggest that she was part of an aristocratic family on the island of Lesbos. It is believed that she was involved in leading a group of women devoted to the arts and worship of the goddess Aphrodite, the deity associated with love and beauty. Sappho’s poetry, much of which is lost, was revered in the ancient world for its intimacy and emotional power.

Sappho’s reputation was such that Plato referred to her as the “tenth Muse.” While only fragments of her work remain today, those fragments offer a glimpse into her genius, focusing on personal feelings, particularly love and desire, rather than the grand, epic themes that dominated much of Greek poetry during her time.

The Sapphic Stanza

The defining feature of Sapphic poetry is the Sapphic stanza, a metrical form that Sappho is credited with developing. This stanza consists of four lines: three longer lines, followed by a shorter one known as the Adonic line. The structure is as follows:

Three lines of 11 syllables each, with a specific metrical pattern.

One final line of 5 syllables, known as the Adonic line, which follows the pattern of one dactyl (one long syllable followed by two short syllables) and one trochee (one long syllable followed by one short syllable).

Here’s a visual breakdown of the meter:

First three lines: – u – x | – u – x | – u u – u

Fourth line (Adonic): – u u | – u

In these notations, a “–” represents a long syllable, a “u” represents a short syllable, and an “x” represents a syllable that can be either long or short.

The Sapphic Meter

Sapphic meter is structured and rhythmic, combining lyricism with strict rules of syllable length and stress. This form lends itself well to personal, emotional expression because of its musicality and fluidity. The alternating pattern of long and short syllables creates a dynamic flow, while the use of the Adonic line at the end of each stanza serves as a rhythmic conclusion, offering a brief but powerful closing note to each verse.

While Sapphic meter is highly structured, it allows for considerable flexibility in terms of tone and theme. Poets can explore a wide range of subjects, but the meter’s emphasis on musicality and rhythm makes it particularly suited to lyrical expressions of emotion, such as love, desire, and introspection.

Examples of Sapphic Meter

One of the most famous examples of Sapphic poetry, albeit in translation, comes from one of Sappho’s surviving fragments, often titled “Hymn to Aphrodite.” While the original Greek adheres strictly to the Sapphic meter, modern translations often adjust the syllable count and rhythm to capture the spirit of the poem in different languages. The following is a translation of a fragment:

“Come to me now, O holy Aphrodite, Freed from your mortal weariness, your golden Chariot, yoked with doves, through the wide heaven Drawn on the breezes.”

Although translations may not always retain the exact meter of the original, the emotional depth, lyrical quality, and thematic focus on love and longing remain central to Sappho’s poetic style.

Themes in Sapphic Poetry

Sappho’s poetry is often focused on themes of personal emotion, love, and desire, which set her apart from many of her contemporaries, who wrote more about epic battles, gods, and heroes. In Sappho’s work, the emotional experience is central, and her poems often reflect deeply personal experiences.

1. Love and Desire

One of the most recurring themes in Sapphic poetry is the exploration of love, often unrequited or filled with longing. Her poems frequently express a yearning for connection, particularly with other women. Sappho’s expressions of desire are candid and tender, exploring the pain, joy, and complexity of love.

This focus on personal emotion, particularly romantic and erotic love, was rare in the ancient world, where most poetry concentrated on heroic deeds and public life. Sappho’s focus on the interior emotional world was groundbreaking and has influenced countless poets throughout history.

2. The Divine and Nature

In addition to love, Sappho’s poetry often invokes the divine, particularly the goddess Aphrodite. Sappho’s relationship with Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, is one of personal devotion, and many of her poems are hymns or prayers directed toward the goddess.

Sappho also wrote about nature, often using natural imagery to mirror human emotions. Flowers, birds, and the sea frequently appear in her poetry, symbolizing various aspects of love, beauty, and transience.

3. Female Experience and Friendship

Sappho’s poetry offers rare insight into the lives and relationships of women in ancient Greece. Many of her poems focus on her relationships with other women, including romantic love, friendship, and mentorship. The island of Lesbos, where Sappho lived, was home to a community of women involved in the arts, and Sappho’s poetry often reflects the deep emotional connections she had with these women.

4. Passage of Time and Loss

Sappho also wrote about the passage of time and the inevitability of loss. Many of her poems reflect on aging, the fleeting nature of beauty, and the sorrow of lost love or separation. These themes give her work a melancholic tone, but they also highlight the intensity and transience of human experience.

Influence of Sapphic Poetry

The influence of Sapphic poetry is far-reaching, extending beyond ancient Greece and into modern times. Sappho’s work has inspired poets and writers for centuries, and the Sapphic stanza has been adopted and adapted by many.

Classical Influence

In antiquity, Sappho’s influence was widespread. Poets such as Alcaeus and Anacreon drew inspiration from her lyricism and emotional depth. The Roman poet Catullus adapted the Sapphic stanza in his own works, blending the Latin language with the Greek meter to create poems that carried Sappho’s lyric spirit into Roman literature.

Influence on Renaissance and Romantic Poets

During the Renaissance, interest in classical Greek literature was revived, and poets across Europe began to explore Sappho’s works once again. Many writers of the period admired her style and themes, particularly the exploration of personal emotion and desire.

The Romantic poets, in particular, embraced Sappho’s intense emotionalism and lyricism. Writers such as Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley looked to Sappho as a model for writing about love, nature, and the sublime. In Shelley’s poem “Sappho,” he reflects on her legacy and the way her emotional depth transcends time.

Sapphic Poetry in Modern Times

In the 19th and 20th centuries, poets such as Algernon Charles Swinburne, Ezra Pound, and H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) revived the Sapphic form in their own work. H.D., in particular, was influenced by Sappho’s fragmented style and lyrical intensity, drawing on the ancient poet’s themes of love, beauty, and loss in her own modernist verse.

The Sapphic form continues to be influential today, with many contemporary poets adopting or adapting the Sapphic stanza to explore themes of love, gender, and identity.

Sappho’s Legacy: Sapphic Love and Modern Interpretations

In addition to her formal contributions to poetry, Sappho’s legacy extends to her exploration of female desire, particularly same-sex desire. The term “Sapphic” has come to be associated with romantic and erotic relationships between women, thanks to the themes explored in her poetry.

Though Sappho’s works do not explicitly focus on homosexuality in the modern sense, her candid expressions of love for women have been interpreted as significant representations of female desire. Over the centuries, Sappho has become a symbol of female homoeroticism and a central figure in LGBTQ+ literature and history.

Conclusion

Sapphic poetry is a lyrical and emotionally rich form of poetry, deeply rooted in the ancient traditions of Greece but also possessing timeless qualities that have resonated with poets and readers throughout history. Through the Sapphic stanza, Sappho created a unique poetic structure that allowed for intense personal expression, making her one of the most celebrated poets in literary history.

Sappho’s exploration of love, desire, friendship, and loss continues to inspire poets today, and the term “Sapphic” has evolved to symbolize both a poetic form and a broader cultural understanding of female relationships and desire. Sapphic poetry remains an essential part of the poetic tradition, bridging the gap between ancient and modern expressions of the human experience.

0 notes

Text

Women in art - history series (very long ago)

Asia

China

Ancient Chinese society was patriarchal, and women were expected to conform to traditional gender roles and remain confined to domestic duties. However, some women challenged these norms and made significant contributions to the art world, leaving behind a legacy that inspires artists today. Despite the societal constraints placed upon them, these women bravely paved the way for future generations of female artists.

Some women were known to be poets, some of their written work has been documented. Ban Zhao was one of the early famous female writers, her most well-known work was Nuje or Instructions for Women, explaining the four virtues women were expected to follow speech, virtue, behavior, and work. Some women could be successful writers and painters or pursue other arts. Generally, these women were in wealthy families or married to men who were influential in society.

Japan

The art world has been greatly enriched by the contributions of these women, who overcame limitations to create remarkable works. Their art reflects the diverse and culturally rich heritage of ancient Japan, and their stories stand as a powerful testament to the resilience and creativity of women throughout history. Today, they continue to inspire artists and admirers alike.

Murasaki Shikibu

Murasaki Shikibu emerged as a prominent writer and poet whose contributions have impacted Japanese literature. Her masterpiece, "The Tale of Genji" , is widely regarded as one of the greatest works in Japanese literature. Notably, Murasaki Shikibu was highly respected by her contemporaries, who recognized her literary prowess and exceptional skills as a poet. Her legacy as a celebrated female artist endures to this day.

Tamako Kataoka

Tamako Kataoka, a renowned artist of the Edo period , was one of the most celebrated female painters of her time. Her artistic achievements were attributed to her exquisite brushwork and mastery of color, which she expertly employed to capture glimpses of nature and everyday life in her works. Despite the societal limitations imposed on women during that era, Kataoka established herself as a highly respected artist. Even today, her paintings continue to profoundly influence the world of Japanese painting.

Americas

In many Native American Tribes women played an essential role in developing art. Native American women participated in day-to-day tribal politics and governance development, which remained unchanged for centuries.

Africa

There are many talented and skilled female artists throughout the continent's history. However, work may not have been as widely recognized or celebrated as male counterparts. For example, women in many African cultures were responsible for creating pottery, textiles, and other everyday items that their families and communities used. While these objects were often beautifully crafted and decorated, they were not always viewed as "art" like, paintings or sculptures.

It is also worth noting that many of the written records and historical accounts from Africa were created by men and may, therefore, not accurately reflect the contributions and achievements of female artists.

Source: GUSTLIN, Deborah and GUSTLIN, Zoe, 2023. Herstory: Women Artists in History.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journal Reflection 5: The Male Gaze

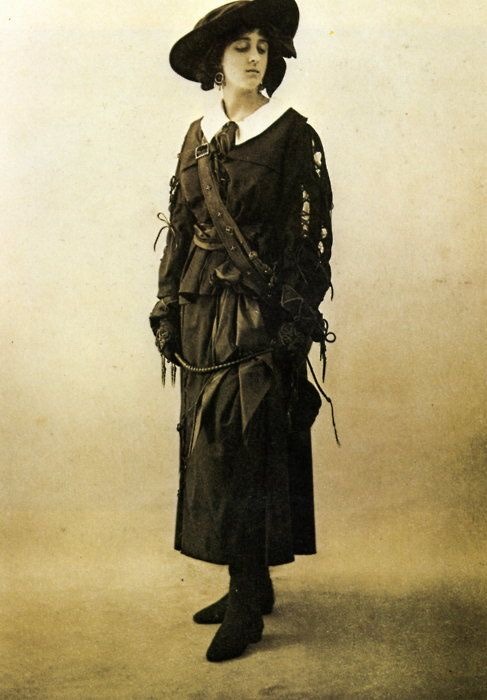

[Dante Gabriel Rossetti, “Joan of Arc” (1882)]

The term for male gaze was coined by Laura Mulvey in 1975, and it is the presentation of women in visual art and literature from a male perspective, where women are portrayed as passive, seductive and sexual objects for the pleasure of the male audience. During the Pre-Raphaelite Brothers the term ‘stunners’ was assigned to women who became their models, which essentially, they kept adding fuel to the fire and sexualizing women more in their paintings. The Pre-Raphaelites depicted their women with red hair, pale skin, and long-neck women, showcased as courtly lovers in ancient, medieval, and Shakespearian tales. One of the notorious models who posed for the pre-Raphaelite artists was Elizabeth Siddal, and I will elaborate more on her later. Furthermore, Mulvey, described the male gaze as a “social construct, emphasizing that if women are seen as objects to be valued for their beauty, physique and sex appeal in art, they will also be seen as such in life”. A good example of this explanation is Joan of Arc, she was a historical female figure in the 15th century and came from a poor and religious background, it is said she used to have religious visions that led her to win the battle against the English in the Hundred Years war. Styling herself as “The Maiden”, wearing a cropped hairstyle, and male armor, she was commanded by God to wear men’s clothing. When she was captured by the English, she was burned at the stake for refusing to wear women’s clothing due to being viewed as controversial, wearing opposite clothes was against religious beliefs at that time. This is already a fixed perspective of how males perceived women, not just because of religious beliefs, what was being portrayed to the audience during that time. There are a couple of paintings where the pre-Raphaelite artists strip Joan of Arc of her origin and what she wore to win the war, they didn’t depict her as a warrior or with short dark hair, but as an alluring figure of a maiden, with a long, beautiful dress, and a sword in hand, provoking beauty.

[Painting of Joan of Arc by Albert Lynch, (1906)] Elizabeth Siddal, as mentioned, was a model for the pre-Raphaelite artists and wife to Dante Gabriele Rosetti, Siddal was more than a muse, she was a painter and a poet. Both Elizabeth and Dante were influenced by each other where they shared artistic commissions and created artworks together, synchronizing their styles and ideas. Although Siddal’s career started before her relationship with Rosetti, she posed for ‘Ophelia’ where she almost died lying in the cold water for 6 hours, and Walter Deverell’s painting ‘Twilight Night’ (1850), where she posed as Shakespeare’s cross-dressing Viola, she portrayed herself as a pageboy Cesario, that was sitting beside the duke and secretly Viola was falling in love for him. This describes her situation at the heart of the brotherhood, where she played multiple characters from mythical and literary characters in paintings and drawings by Holman Hunt, Anna Mary Howitt, and Barbara Bodichon, in addition to others. It is known as well, that Rossetti wasn’t a great husband to Siddal, demanding her to model for him only, meanwhile, he slept and worked with other models, moreover, he remained engaged for ten years to Siddal without planning a wedding date, thus, leaving her in a difficult position given the Victorian attitudes towards unmarried models. We see Elizabeth Siddal as more than a muse, she had a lot to offer us, and she was “the rallying cry of many feminist art historians”. Consequently, we see her as Rossetti desired, his partner alone, rather than an established figure that collaborates with other artists as a means of infiltrating the patriarchal art world prior exhibiting with them. Many writings of Elizabeth Siddal were written by and to benefit men, and they showcase the trope of a submissive, romantic female model at the mercy of a great male artist. Therefore, this stereotype is harmful, Feminist art history rearranges the contributions of Siddal, who was an artist and poet who inspired, performed for and collaborated on multiple masterpieces.

References

Frisby, N., 2020. ‘I am a woman, not an exhibit.’ The effects of the male gaze in art, literature and today’s society. [Online] Available at: https://www.panmacmillan.com/blogs/literary/the-doll-factory-the-effects-of-the-male-gaze#:~:text=In%201975%2C%20film%20critic%20Laura,pleasure%20of%20the%20male%20viewer. [Accessed 22 January 2024].

Millington, R., 2023. Elizabeth Siddal: More than a muse?. [Online] Available at: https://ruthmillington.co.uk/elizabeth-siddal-paintings/ [Accessed 22 January 2024].

Scott, F. H. R., 2022. Joan of Arc didn’t call herself non-binary – but gendering her isn’t that straightforward. [Online] Available at: https://www.thepinknews.com/2022/08/16/joan-of-arc-non-binary-historian/ [Accessed 22 January 2024].

0 notes

Note

Uh hey. One of your interests/hypes was ancient female poets? Could you recommend some names or works you found interesting? Sorry I just REALLY like poetry.

OH MY GOODNESS YES OKAY GIMME A MINUTE TO COLLECT MYSELF

..............

My list begins here:

Renèe Vivien- A lesbian poet who was known for her multiple collections of poems, including: A Crown of Violets, The Woman of The Wolf (and other stories), and A Woman Appeared to Me.

Katherine Philips- A wonderfully underrated poet who has been featured in a few separate books about historical poetry, including: The Collected Works of Katherine Philips: The Matchless Orinda, Minor Poets of The Caroline Period (Volume 1), and The Renaissance Poets (Volume 2).

Anna de Noalles- A french poet and a feminist! She only has one collection, and that is: A Life of Poems, Poems of a Life.

Natalie Clifford Barney- One of Vivien's lovers, actually! She was a playwright and a novelist, generally speaking, but she does have one collection of poems: Poems & Poems; autres alliances.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning- A victorian poet, personally I don't enjoy her work very much (no real reason.. it just doesn't hit quite right). But she has several, and I mean SEVERAL works. Notable ones are: Sonnets From the Portuguese, and Aurora Leigh. Many of the others are just titled "Poems" but the volumes do not align with the times they were published (volume 2 was published ten years before volume 1??? And other weird things) so I'll let you sort that out if you're really interested.

I saved the best for last:

Phillis Wheatley (or Phyllis Wheatly)- The very first black woman author of a published book of poetry in the USA(according to what I've read, if anyone else does more research and finds out this is incorrect, please let me know). Her published book (1773) is Poems on Various Subjects: Religious and Moral, and there are several modern collections that have been published over the years.

..............

I hope these were helpful!! I can 100% find some more for you if you'd like, thank you for indulging me!! Poetry is one of my favorite forms of literature and I'm always looking for an opportunity to talk about it with other people that find it interesting.. You've truly made my night :)

#hopefully the read more banner worked#if not I'll feel stupid#poetry#female poets#lesbian#lesbiansafe#bambi lesbian#sappho#bambi lesbian posts#wlw#literature#ancient female poets and historical literature

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book rec: Sapphistries by Leila J. Rupp

“From the ancient poet Sappho to tombois in contemporary Indonesia, women throughout history and around the globe have desired, loved, and had sex with other women.

In beautiful prose, Sapphistries tells their stories, capturing the multitude of ways that diverse societies have shaped female same-sex sexuality across time and place.

Leila J. Rupp reveals how, from the time of the very earliest societies, the possibility of love between women has been known, even when it is feared, ignored, or denied. We hear women in the sex-segregated spaces of convents and harems whispering words of love. We see women beginning to find each other on the streets of London and Amsterdam, in the aristocratic circles of Paris, in the factories of Shanghai. We find women’s desire and love for women meeting the light of day as Japanese schoolgirls fall in love, and lesbian bars and clubs spread from 1920s Berlin to 1950s Buffalo. And we encounter a world of difference in the twenty-first century, as transnational concepts and lesbian identities meet local understandings of how two women might love each other.

Giving voice to words from the mouths and pens of women, and from men’s prohibitions, reports, literature, art, imaginings, pornography, and court cases, Rupp also creatively employs fiction to imagine possibilities when there is no historical evidence.

Sapphistries combines lyrical narrative with meticulous historical research, providing an eminently readable and uniquely sweeping story of desire, love, and sex between women around the globe from the beginning of time to the present.“

Downloand PDF

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: I really enjoyed your book review of Sebastian Junger’s Homecoming. Perhaps enjoyment isn’t the right word because it brought home some hard truths. Your book review really helped me understand my older brother better when I think back on how he came home from the war in Afghanistan after serving with the Paras and had medals pinned up the yin yang. It was hard on everyone in the family, especially for him and his wife and young kids. He has found it hard going. Thanks for sharing your own thoughts as a combat veteran from that war. Even if you’re a toff you don’t come across as a typical Oxbridge poncey Rupert! As you’re a classicist and historian how did ancient soldiers deal with PTSD? Did the Greeks and Roman soldiers even suffer from it like our fighting boys and girls do? Is PTSD just a modern thing?

Part 1 of 2 (see following post)

Because this is subject very close to my heart as a combat veteran I thought very long and hard about the issues you raised. I decided to answer this question in two posts.

This is Part 1 and Part 2 is the next post.

My apologies for the length but this is subject that deserves full careful consideration.

Thank you for your lovely words and I especially find its heart warming if they touched you. I appreciate you for sharing something of the experience your ex-Para brother went through in coming home from war. I have every respect for the Parachute regiment as one of the world’s premier fighting force.

Working alongside them on missions out in Afghanistan I could see their reputation as the ‘brain shit’ of the British Army was well deserved. They’re most uncouth, sweary, and smelliest group of yobbos I’ve ever had the awful misfortune to meet. I’m kidding. The mutual respect and the ribbing went hand in hand. I doff my smurf hat to the cherry berries as ‘propah soldiers’ as they liked to say especially when they cast a glance over at the other elite regiments like HCav and the guards regiments.

Don’t worry I’ve been called a lot worse! But I am grateful you don’t lump me with the other ‘poncey’ officers. Not sure what a female Rupert is called. The fact that I was never accused of being one by any of those I served with is perhaps something I take some measure of pride. There are not as many real toff officers these days compared to the past but there are a fair few Ruperts who are clueless in leading men under their charge. I knew one or two and frankly I’m embarrassed for them and the men under their charge.

I don’t know when the term PTSD was first used in any official way. My older sister who is a doctor - specialising in neurology and all round brain box and is currently working on the front lines in the NHS wards fighting Covid alongside all our amazing NHS nurses and doctors - took time out one evening to have a discussion with me about these issues. I also talked to one or two other friends in the psychiatric field too. In consensus they agree it was around 1980 when the term PTSD came into usage. Specifically it was the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-lll) published by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980 partly because as a result of the ongoing treatment of veterans from the Vietnam War. In the modern mind, PTSD is more associated with the legacy of the Vietnam War disaster.

The importance of whether PTSD affected the ancient Greeks and Romans lies in the larger historical question of to what extent we can apply modern experience to unlock or interpret the past. In the period since PTSD was officially recognised, scholars and psychologists have noted its symptoms in descriptions of the veterans of past conflicts. It has become increasingly common in books and novels as well as articles to assume the direct relevance of present-day psychology to the reactions of those who experienced violent events in the historical past. In popular culture, especially television and film dramas, claims for the historical pedigree of PTSD are now often provided as background to the modern story, without attribution. Indeed we just take it as a given that soldier-warriors in the past suffered the same and in the same way as their modern day counterparts. We are used to the West to map the classical world upon the present but whether we can so easily map the modern world back upon the Greeks and Romans is a doubtful proposition when it comes to discussing PTSD.

Simply put, there is no definitive evidence for the existence of PTSD in the ancient world existed, and relies instead upon the assumption that either the Greeks or Romans, because they were exposed to combat so often, must have suffered psychological trauma.

There are two schools of thought regarding the possibility of PTSD featuring in the Greco-Roman world (and indeed the wider ancient world stretching back into pre-history, myth and legend) – universalism and relativism. Put simply, the universalists argue that we all carry the same ‘wetware’ in our heads, since the human brain probably hasn’t developed in evolutionary terms in the eye blink that is the two thousand years or so since the Greco-Roman Classical era. If we’re subject to PTSD now, they posit, then the Greeks and the Romans must have been equally vulnerable. The relativists, on the other hand, argue that the circumstances under which the individual has received their life conditioning – the experiences which programme the highly individual software running that identical ‘wetware’, if you will – is of critical importance to an individual’s capacity to absorb the undoubted horrors of any battlefield, ancient or modern.

Whichever school one falls down on the side of is that what seems to happen in any serious discussion of the issue of PTSD in the ancient world is to either infer it indirectly from culture (primarily, literature and poetry) or infer it from a comparative historical understanding of ancient warfare. Because the direct evidence is so scant we can only ever infer or deduce but can never be certain. So we can read into it whenever we wish.

In Greek antiquity we have of course The Illiad and the Odyssey as one of the most cited examples when we look at the character traits of both Achilles and Odysseus. From Greek tragedy those who think PTSD can be inferred often point to Sophocles’s Ajax and Euripide’s Heracles. Or they look to Aeschylus and The Oresteia. I personally think this is an over stretch. Greek writers do; the return from war was a revisited theme in tragedy and is the subject of the Odyssey and the Cyclic Nostoi.

The Greeks didn’t leave us much to ponder further. But, with rare exceptions, the works from Graeco-Roman antiquity do not discuss the mental state of those who had fought. There is silence about the interior world of the fighting man at war’s end. So we are led to ponder the question why the silence?

This silence also echoes into the Roman period of literature and history too. Indeed when we turn to the Roman world, descriptions of veterans are rare in the writings that survive from the Roman world and occur most often in fiction.

In the first poem of Ovid’s Heroides, the poet writes about a returned soldier tracing a map upon a table (Ov. Her. 1.31–5):

...upon the tabletop that has been set someone shows the fierce battles, and paints all Troy with a slender line of pure wine:

‘Here the Simois flowed; this is the Sigeian territory,

here stood the lofty palace of old Priam, there the tent of Achilles...’

This scene provides an intimate glimpse of what it must have been like when a veteran returned home and told stories of his campaigns: the memories of battle brought to the meal, the crimson trail of the wine offering a rough outline of the places and battlefields he had experienced. The military characters in poems and plays show a world in which soldiers are ubiquitous, if somewhat annoying to the civilians. Plautus, for instance, in his Miles Gloriosus, portrays an officer boasting about his made-up conquests – the model for the braggart in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum – and Juvenal complains about a centurion who stomps on his sandalled foot in the bustling Roman street.

Despite this silence, compelling works have been written that interweave vivid modern accounts of combat and its aftermath with quotes from ancient prose and poetry. At their best, these comparisons can illuminate both worlds, but at other times the concerns of the present-day author are imposed on the ancient material. But the question remains are such approaches truthful and valid in understanding PTSD in the ancient world?

So if arts and literature don’t really tell us much what about comparative examples drawn from military history itself?

Here again we are in left disappointed.

According to the Greek historian, Herodotus, in 480 B.C., at the Battle of Thermopylae, where King Leonidas and 300 Spartans took on Xerxes I and 100,000-150,000 Persian troops, two of the Spartan soldiers, Aristodemos and another named Eurytos, reported that they were suffering from an “acute inflammation of the eyes,”...Labeled tresantes, meaning “trembler,”. It is that Aristodemos later hung himself in shame. Another Spartan commander was forced to dismiss several of his troops in the Battle of Thermopylae Pass in 480 B.C, “They had no heart for the fight and were unwilling to take their share of the danger.”

Herodotus again in writing about the battle of Marathon in 490 B.C., cites an Athenian warrior who went permanently blind when the soldier standing next to him was killed, although the blinded soldier “was wounded in no part of his body.” Interestingly enough, blindness, deafness, and paralysis, among other conditions, are common forms of “conversion reactions” experienced and well-documented among soldiers today

Outside the fictional world, Roman military history tell us very little.

Appian of Alexandria (c. 95? – c. AD 165) described a legion veteran called Cestius Macedonicus who, when his town was under threat of capture by (the Emperor-to-be) Octavian, set fire to his house and burned himself within it. Plutarch’s Life of Marius speaks of Caius Marius’ behaviour who, when he found himself under severe stress towards the end of his life, suffering from night terrors, harassing dreams, excessive drinking and flashbacks to previous battles. These examples are just a few instances which seem to demonstrate that PTSD, or culturally similar phenomena, may be as old as warfare itself. But it’s worth stressing it is not definitive, just conjecture.

Of course of accounts of wars and battles were copiously written but not the hard bloody experience of the soldier. Indeed the Roman military man is described almost exclusively as a commander or in battle. Men such as Caesar who experienced war and wrote about it do not to tell us about homecoming.

It seems one of main challenges when we try to see military history through the lens of our definition of PTSD is to first understand the comparative nature of military history and what it is we are comparing ie mistaking apples for oranges.

The origin of military history was tied to the idea that if one understood ancient battle, one might fight and, more importantly, one might lead and strategise more effectively. In essence, much of the training of officers – even in the military handbooks of the Greeks and Romans – was an attempt to keep new commanders from making the same mistakes as the commanders of old. Military history is intended to be a pragmatic enterprise; in pursuit of this pragmatic goal, it has long been the norm to use comparative materials to understand the nature of ancient battle.

The 19th Century French military theorist Ardant du Picq argued for the continuity of human behaviour and assumed that the reactions of men under the threat of lethal force would be identical over the centuries: “Man does not enter battle to fight, but for victory. He does everything that he can to avoid the first and obtain the second....Now, man has a horror of death. In the bravest, a great sense of duty, which they alone are capable of understanding and living up to, is paramount. But the mass always cowers at sight of the phantom, death. Discipline is for the purpose of dominating that horror by a still greater horror, that of punishment or disgrace. But there always comes an instant when natural horror gets an upper hand over discipline, and the fighter flees”

These words offer insight to those of us who have never faced the terror of battle but at the same time assume the universality of how combat is experienced, despite changes in psychological expectations and weaponry, to name but two variables.

Another incentive for scholars and researchers is to turn to comparative material has been the growing awareness of the artificiality of how we describe war. A mere phrase such as ‘flank attack’ does not capture the bloody, grinding human struggle. Roman authors – especially those who had not fought – often wrote generic descriptions of battle. Literary battle can distort and simplify even as it tells, but if the main things are right – who won, who lost, and who the good guys are – the important ‘facts’ are covered. Even if one intends to speak the truth about battle, the assumptions and the normative language used to describe violence will affect the telling. We may note that the battle accounts in poetry become increasingly grisly during the course of the Roman Empire (perhaps owing to the growing popularity of gladiatorial games),while, in Caesar’s Gallic War, the Latin word cruor (blood) never appears and sanguis (another Latin word for blood) only appears in quoted appeals (Caes. B. Gall. 7.20, in the mouth of Vercingetorix, and 7.50, where the centurion M. Petronius urges his men to retreat). The realities of the battlefield are described in anodyne shorthand. In much the same way that the news rarely prints or televises graphic images, Caesar does not use gore, and perhaps for the same reason – to give a sense of reportorial objectivity.

Another element in the interpretive scrum is a given author’s goal in writing an account in the first place: Caesar, for example, was writing about himself, and he may have been producing something akin to a political campaign ad. Caesar makes Caesar look great and there is reason to believe that, if he was not precisely cooking the books, he did give them a little rinse to make him look more pristine. Given the many factors that complicate our ability to ‘unpack’ battle narratives, Philip Sabin has argued that the ambiguity and unreliability of the ancient sources must be supplemented by looking at the “form of the overall characteristics of Roman infantry in mortal combat”. Again the modern is used to illuminate that which is obscured by written accounts and the “the enduring psychological strains” are merely unconsciously assumed.

These legitimate uses of comparative materials have led to a sort of creep: because military historians have used observations of how men react to combat stress during battle to indicate continuity of behaviour through time, there appears to be a consequent expectation that men will also react identically after battle. This creep became a lusty stride with modern books written about the ancient world and PTSD.

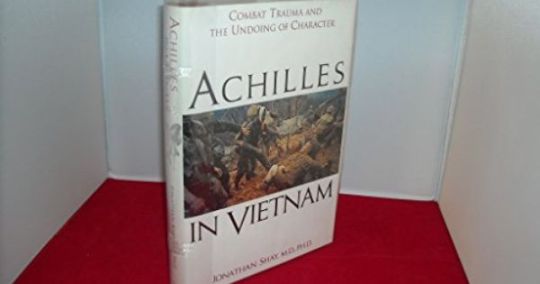

After I finished my tour in Afghanistan I read many books recommended to me by family and friends as well as comrades. One of these books is well known in military circles - at least amongst the thinking officer class - as an iconic work of marrying the ancient world and the modern experience of war. I read it and I was touched deeply by this brilliant therapeutic book. It was only months later I began to re-think whether it was a true account of PTSD in the ancient world.

This insightful book is called Achilles in Vietnam by Jonathan Shay. Shay is psychiatrist in Boston, USA. He began reading The Iliad with Vietnam veterans whom he was treating. Achilles in Vietnam, is a deeply humane work and is very much concerned with promoting policies that he hoped would help diminish the frequency of post-traumatic stress. His goal was not to explain ancient poetry but to use it therapeutically by linking his patients’ pain to that of the Iliad’s great hero. His book offers a conduit between the reader and the experiences of the men that Shay counsels. In the introduction to this work he makes a nod to Homerists while also asserting the primacy of his own reading:

“I shall present the Iliad as the tragedy of Achilles. I will not glorify Vietnam combat veterans by linking them to a prestigious ‘classic’ nor attempt to justify study of the Iliad by making it sexy, exciting, modern or ‘relevant’. I respect the work of classical scholars and could not have done my work without them. Homer’s poem does not mean whatever I want it to mean. However, having honored the boundaries of meaning that scholars have pointed out, I can confidently tell you that my reading of the Iliad as an account of men in war is not a ‘meditation’ that is only tenuously rooted in the text. “

After outlining the major plot points around which he will organise his argument, he notes, “ ‘This is the story of Achilles in the Iliad, not some metaphorical translation of it”.

The trouble was and continues to be is that many in the historical and medical fields began to rush to unfounded conclusions that Shay, on the issue of PTSD in the ancient world, had demonstrated that the psychological realities of western warfare were universal and enduring. More books on similar comparative themes soon emerged and began to enshrine the truth that PTSD was indeed prevalent throughout the ancient world and one could draw comparative lessons from it.

Perhaps one of the most influential books after Shay was by Lawrence Tritle. Tritle, a veteran himself, wrote From Melos to My Lai. It’s a fascinating book to read and there are parts that certainly resonate with my own experiences and those of others I have known. In the book Tritle drew a direct parallel between the experiences of the ancient Greeks and those of modern veterans. For instance, Xenophon, in his military autobiography, presents a brief eulogy for one of his fallen commanders, Clearchus. Xenophon writes that Clearchus was ‘polemikos kai philopolemos eschatos’ (Xen. An. 2.6) – ‘warlike and a lover of war to the highest degree’.

Tritle comments:

“The question that arises is why men like Clearchus and his counterparts in Vietnam and the Western Front became so entranced with violence. The answer is to be found in the natural ‘high’ that violence induces in those exposed to it, and in the PTSD that follows this exposure. Such a modern interpretation in Clearchus’ case might seem forced, but there seems little reason to doubt that Xenophon in fact provides us with the first known historical case of PTSD in the western literary tradition.”

Arguably in the West and especially our current modern Western culture is predicated at baulking at the notion of being ‘war lovers” as immoral. But such an interpretation speaks more of our modern Christianised ambivalence towards war; to the Spartans and Athenians the term would not have had a negative connotation. ‘Philopolemos’ is, in fact, a compliment, and the list of Clearchus’ military exploits functions as a eulogy. There are points where his analysis does not adequately address the divergences between ancient and modern experiences.

For all the talk of our Western culture being rooted in Ancient Greece and Rome we are not shaped by the same ethics. Our modern ethics and our moral code is Christian. There is no such thing as a secular humanist or atheist both owe a debt to Christianity for the way they have come to be; in many respects it’s more accurate to describe such people as Christianised Humanists or Christian Atheists even if they reject the theological tenets of the religious faith because they use Christian morality as the foundation to construct their own. Many forget just how brutal these ancient societies were in every day life to the point there would be little one could find recognisable within our own modern lives.

Now we come to third point I wish to make in determining where the Greeks or Romans actually experienced PTSD. This is to do with the little understood nature of PTSD itself. As much as we know about PTSD there is still much more we don’t know. Indeed one of the most problematic and complicated issues is the continued disagreement around the diagnosis and specific triggers of the disorder which remain little understood. We have to admit there are competing theories about what causes PTSD but, in terms of experiences that make it manifest, there are essentially three possible triggers: witnessing horrific events and/or being in mortal danger and/or the act of killing – especially close kills where the reality of one’s responsibility cannot be doubted. The last of these was strongly argued in another scholarly book by D. Grossman, On Killing, the Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (1995).

Roman soldiers had the potential to experience all of these things. The majority of Roman combat was close combat and permitted no doubt as to the killer. The comparatively short length of the gladius encouraged aggressive fighting. Caesar recounts how his men, facing a shield wall carried by the taller Gauls, leaped up on top of the shields, grabbed the upper edges with one hand, and stabbed downwards into the faces of their opponents (Caes. B. Gall. 1.52). As for mortal danger, Stefan Chrissanthos in his informative book, Warfare in the Ancient World: From the Rise of Uruk to the Fall of Rome, 3500BC-476AD, puts it this way: “For Roman soldiers, though the weapons were more primitive, the terrors and risks of combat were just as real. They had to face javelins, stones, spears, arrows, swords, cavalry charges, and maybe worst of all, the threat of being trampled by war elephants.”

Such terrors are regularly attested. During his campaign in North Africa, Caesar, noting his men’s fear, procured a number of elephants to familiarise his troops with how best to kill the beasts (Caes. B. Afr.72). It should also be noted that it was not unusual for the reserve line to be made up of veterans because they were better able to watch the combat without losing their nerve. Held in reserve, they had to watch stoically as their comrades were injured and killed, and contemplate the awful fact that they might suffer the same fate. This was not a role for the faint of heart.

However, while the Romans certainly had the raw ingredients for combat trauma, the danger for a Roman legionary was much more localised. Mortars could not be lobbed into the Green Zone, suicide bombers did not walk into the market, and garbage piled on the street did not hide powerful explosives. The danger for a Roman soldier was largely circumscribed by his moments on the field of battle, and even here, if he was with the victorious side, the casualties were likely to be light: at Gergovia, a disaster by Caesar’s standards, he lost nearly seven hundred men (Caes. B. Gall. 7.51). In his victory over Pompey the Great at Pharsalus, his casualties numbered only two hundred (Caes. B. Civ. 3.99).

So we are left with the disturbing question: were the stressors really the same?

This is the part where I also defer to my eldest sister as a doctor and surgeon specialising in neurology and just so much smarter than myself.

My eldest sister holds the view in talking to her own American medical peers that despite similar experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq, British soldiers on average report better mental health than US soldiers.

My sister pointed out to research study done by Kings College London way back around 2015 or so that analysed 34 studies produced over a 15-year period (up to 2015) and found that overall there has been no increase in mental health issues among British personnel - with the exception of high rates of alcohol abuse among soldiers. The study was in part inspired the “significant mental health morbidity” among U.S. soldiers and reports that factors such as age and the quality of mental health programs contribute to the difference between the two nation’s servicemen and women.

She pointed out that these same studies showed that post-traumatic stress disorder afflicts roughly 2 to 5% of non-combat U.K. soldiers returning from deployment, while 7% of combat troops report PTSD. According to a General Health Questionnaire, an estimated 16 to 20% of U.K. soldiers have reported symptoms of common mental disorders, similar to the rates of the general U.K. population. In comparison, studies around the same time in 2014 showed U.S. soldiers experience PTSD at rates of 21 to 29%. The U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs estimated PTSD afflicted 11% of veterans returning from Afghanistan and 20% returning from Iraq. Major depression was reported by 14% of major soldiers according to another study commissioned by RAND corporation; roughly 7% of the general U.S. population reports similar symptoms.

It’s always tough comparing rates between countries and is not a reflection of the quality of the fighting soldier. But one finding that consistently and stubbornly refuses to go away is that over the past 20 years reported mental health problems tend to be higher among service personnel and veterans of the USA compared with the UK, Canada, Germany and Denmark.

However my sister strongly cautioned against making hasty judgements. And there could be many variable factors at play. One explanation is that American soldiers are more likely than their British counterparts to be from the reserve forces. Empirical studies showed reservists from both America and British troops were more likely to experience mental illness post-deployment. It was also worth pointing out that American soldiers also tended to be younger - being younger and inexperienced as well as untested on the battlefield, service personnel would naturally run the risk of greater and be more vulnerable to mental illness.

In contrast, the elite forces of the British army, such as your brother’s Parachute Regiment or the Royal Marines, were found to be the least affected by mental illness. It was found that in spite of elite forces experiencing some of the toughest fighting conditions, they tended to enjoy better mental health than non-elite troops. The more elite a unit is or more professional then you find that troops tend to enjoy a very deep bonds of camaraderie. As such the social cohesion of these fighting forces provides a psychological protective buffer. Not for all, but for many.

More intriguing are new avenues of discovery that might go a long way to actually understanding one of the root causes of PTSD. According to my sister, recent research carried out in the US and Europe and published in such prestigious medical journals as the New England Journal of Medicine (US) and the Lancet (UK), seems to establish a causal link between concussive injury and PTSD.

One recent study looked at US soldiers that concerned itself with the effects of concussive injuries upon troops after their return from active duty during the war in Iraq.

Of the majority of soldiers who suffered no combat injuries of any sort, 9.1 per cent exhibited symptoms consistent with PTSD. This allows a baseline for susceptibility of roughly 10% of the population. A slightly higher number (16.2%) of those who were injured in some way, but suffered no concussion, also experienced symptoms. As soon as concussive injuries were involved, however, the rates of PTSD climbed dramatically.

Although only 4.9% of the troops suffered concussions that resulted in complete loss of consciousness, 43.9% of these soldiers noted on their questionnaires that they were experiencing a range of PTSD symptoms. Of the 10.3% of the unit who suffered concussion resulting in confusion but retained consciousness, more than a quarter (27.3%) suffered symptoms. This suggests a high correlation between head trauma and the occurrence of subsequent psychological problems. The authors of the study note that ‘concern has been emerging about the possible long term effect of mild traumatic brain injury or concussion...as a result of deployment related head injuries, particularly those resulting from proximity to blast explosions’

Although these results are preliminary, if confirmed they have profound implications for anyone trying to understand the nature of warfare in the ancient world, especially the Western world.

So why does it matter?

In Roman warfare, wounds were most often inflicted by edged weapons. Romans did of course experience head trauma, but the incidence of concussive injuries would have been limited both by the types of weapons they faced and by the use of helmets. Indeed the efficacy and importance of headgear for example can be deduced from the death of the Epirrote general Pyrrhus from a roof tile during the sack of Argos. It is likely that the Romans designed their helmets with an eye to blunting the force of the blows they most often encountered. Connolly has argued that helmet design in the Republican period suggests a crouching fighting stance (see P. Connolly, ‘The Roman Fighting Technique Deduced from Armour and Weaponry’, Roman Frontier Studies (1989). However my own view is that the change in helmet design may signal instead a shift in the role of troops from performing assaults on towns and fortifications when the empire was expanding (and the blows would more often rain from above) to the defence and guarding of the frontiers.

While the evidence is clear that concussion is not the only risk factor for PTSD, it is so strongly correlated that it suggests that the incidence of PTSD may have risen sharply with the arrival of modern warfare and the technology of gunpowder, shells, and plastic explosives. Indeed, accounts of shell shock from the First World War are common, and it was in the wake of that war that those observing veterans suspected that neurological damage was being caused by exploding shells.

For soldiers of the Second World War and down to our modern day, an artillery barrage is like an invention of hell.

As one American put it in his memoirs of fighting the Japanese at Peleiu and Okinawa, “I developed a passionate hatred for shells. To be killed by a bullet seemed so clean and surgical but shells would not only tear and rip the body, they tortured one’s mind almost beyond the brink of sanity. After each shell I was wrung out, limp and exhausted. During prolonged shelling, I often had to restrain myself and fight back a wild inexorable urge to scream, to sob, and to cry. As Peleliu dragged on, I feared that if I ever lost control of myself under shell fire my mind would be shattered. To be under heavy shell fire was to me by far the most terrifying of combat experiences. Each time it left me feeling more forlorn and helpless, more fatalistic, and with less confidence that I could escape the dreadful law of averages that inexorably reduced our numbers. Fear is many-faceted and has many subtle nuances, but the terror and desperation endured under heavy shelling are by far the most unbearable” (see E.B. Sledge, With the Old Breed at Peleiu and Okinanwa, 2007).

The psychological effect of shelling seems to result from the combined effect of awaiting injury while at the same time having no power to combat it.

There is another aspect that I alluded to above which is the psychological and societal conditioning of the Roman soldier. In other words a Roman male’s social and cultural expectations of his place in the world. Feelings of helplessness and fatalism were probably a less alien experience for most Romans – even those in the upper classes. In general, the Romans inhabited a world that was significantly more brutal and uncertain than our own.

This another way of saying that the Roman and 21st century combat are very different in a variety of ways that subject the modern soldier to a good deal more stress than the legionary was ever likely to suffer. And the Roman’s societal preparation – his life before the battle – was far more robust than that we enjoy today.

Take infant mortality. In the modern developed world, our infant mortality rates are about ten per thousand. In Rome, it is estimated that this number was three hundred per thousand. Three-tenths of infants would die within the first year, and an additional fifth would not make it to the age of ten - 50% of children would not survive childhood. Anecdotal evidence supports these statistics: Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi, gave birth to twelve children between 163 bc and 152 bc; all twelve survived their father’s death in 152 bc, but only three survived to adulthood. Marcus Aurelius and his wife, Faustina, had at least twelve children but only the future emperor Commodus survived.

Then look at how that child grows up. The typical Roman child would be raised in a society that readily accepted ultra-violent arena entertainment, mob justice, frequent and bloody warfare as a fact of life. This was reinforced by religious and societal encouragement to see war as natural and beneficial, open butchering of food animals, a total lack of support structures for the poor and less able.

Compared to the legionary our modern soldier has been protected from such realities to a greater degree than at any other point in history, and will thus be far less well prepared for the horror of a warfare that contains far more stress factors than for a man who might fight a handful of battles in his military career, with long periods of relative calm in between, state of war notwithstanding. Modern special and elite forces training often emphasises the brutalisation and ‘rebuilding’ of the recruit in readiness for this step into darkness, but it seems likely that no such conditioning would have been needed two thousand years ago.

I would argue that we experience war very differently from the way the Romans did. Our modern identity is defined far more by our Western Christian heritage than our Western Classical roots. They are in fact world apart when it comes to ethics and morality. Consider the fact that when we talk of war and killing today we often do so through conflict between our civilian moral codes – which offer the strict injunction not to do violence to other human beings – and wartime, when men are commanded to violate such prohibitions. It is a terrible thing to try to navigate ‘Thou shalt not kill’ and the necessity of taking a life in combat.

It is sometimes the case that the qualities that make the best soldier do not make the best civilian, a point amply attested in Greek poetry by heroes such as Heracles and Odysseus.

The Romans, for their part, celebrated heroes such as Cincinnatus, who could command effectively and then leave behind the power he wielded to return to his humble plough. It is important, however, when evaluating combat and its effects in the ancient world, that we do not read our ambivalence about violence onto the Romans. They inhabited an empire whose prosperity was quite openly tied to conquest.

As M. Zimmerman writes in his academic article, “Violence in Late Antiquity Reconsidered’ (2007), “The pain of the other, seen on the distorted faces of public and private monuments, or heard in the screams of criminals in the amphitheatre, reassured Romans of their own place in the world. Violence was a pervasive presence in the public space; indeed, it was an important basis for its existence, pertaining as it did not only to victories over external enemies but also to the internal order of the state.”

Violence then was both the means and the expression of Roman power. The Roman soldier was its instrument. The Roman warrior then would have brought a different perspective to lethal violence, and would have had a far more restricted moral circle to his modern counterpart – his friends and family, clan, patron and clients, as opposed to millions of fellow citizens via the internet and social media.

Part II follows next post

#question#ask#PTSD#war#roman#greek#classical#legionary#spartan#mental health#depression#trauma#warfare#british army#mental illness#homecoming#soldiers#combat veterans#veterans

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thoughts on a person from history you want the old guard to have interacted with?

OH MY GOSH SO! A QUESTION and also i’ll have to give multiple answers lol

One of the ideas I love most that i think is hinted at is if they interact famous historical people from history it’s two or three generations earlier like it has these ambiguous implications of either a) some kind of divine mission which i LOVE or else b) the whole theme of you get helped up and then you help someone else up we are not meant to be alone circa Celeste the French Shop Clerk... but writ super large anyway this is to say i think most of the time it’s the grandparents of famous people they meet? but i digress. anyway on my list of Famous People from history i want them to have interacted with i’m leaning more towards artist/ and scientist types from what copley’s said, some of the coolest (female) ones maybe include Alice Ball a Black female scientist who at the age of 24 found the first effective treatment for Hansen’s disease/leprosy until antibiotics were invented, Dr. Rita Levi Montalcini, an Italian Jewish neurobiologist who won a Nobel prize for groundbreaking work on nerve factors, and Dr. Flossie Wong-Staal, the Chinese-American scientist whose work on HIV helped ID it as cause of AIDS among other things. Moving on to artists... just a personal fave but on my personal canon of “Nicky likes to play guitar” i totally think there’s a time when Copley’s cleaning out his wife’s record collection and like. realises Nicky’s been on the cover of one of her vinyls of Joan Baez’s recording sessions as a backup guitarist. but she was super cool and probably my favorite 20th century folk singer both for her original work and covers , as well as a Latina woman and dedicated supporter of civil rights and left-wing causes.

that got america centric but moving deeper into history! Andy and Quynh and Lykon are just so... UNIMAGINABLY OLD and it’s wild to think that the birth of writing would have only happened like. a good chunk of the way into their lives. SO- 𒂗𒃶𒌌𒀭𒈾, Enheduanna, the first writer in history whose work we can attach to a name! Cool as hell. (Also it would be fun if they’d gotten cheated by that one sketchy ancient grain dealer tumblr looses their shit over periodically but i don’t know anything about him.)

As for medieval figures i really want Yusuf to have met- Samuel HaNagid! COOL AS HELL AND SOOO interesting! a medieval Jewish polymath from Al-Andalus who was variously a poor spice merchant, statesman, vizier to the caliph, Hebrew and Arabic language poet, Arabic calligrapher, grammarian, Talmudic Scholar and commentator, warrior, and supporter of literature and learning. (Also due to how much of a pleasure seeker the caliph he was vizier for was- arguably ruled as caliph himself, at least in running things and military battle) you can read some of his poetry here, just gonna throw out to all fic writers that he literally wrote the lines “ Make me drunk with the blood of the foe on the day of war And satisfy me with his flesh on the night of redemption.” (haven’t found the og hebrew so can’t testify how accurate this is BUT) (ALso pretty sure some of his love poetry was about men but i can’t find it right now)

ANyway this is just some TOP figures, others i kind of have... squirrelled away to use in fics! hope this was roughly what you were looking for and also i tried hard but am ya know an undergrad with google rather than a trained historian so hopefully this is broadly free of historical mistakes!

#asks#thank you so much!#i have like ideas this isn't even like 1/3 of the people i've thought of#the old guard

77 notes

·

View notes

Note

Follow up questions because I’m a Nerd and I love learning: is there any evidence to suggest frequent inclusion of women in Scandinavian warfare? Or is finding something like women’s armor rare? Was there a standard definition of any queer terminology in any ancient civilization? Did any Norse culture ever find its way to the Middle East???

I feel a bit like an over eager student writing this but uh...I’m very curious. 👀👀

When talking about women in Scandinavia you run into people describing how it appeared these women would take on the role of men in the absence of men. But I think there is an issue in that we’re assuming the role of women in these societies would match the role of an Ancient Greek woman (which is a whole other thing but I digress)

They’ve found that some of the founding fathers of Iceland were women, thirteen of them to be exact. women could inherit land and money from their parents. Women could be involved in legal matters and hold official positions.

There is lots of evidence that women were very frequently going raiding. They have been debating recently I believe if the term dregnr a young warrior really was only applied to men. Young women were described in the same vulgar terms as dominators and something we discuss in ancient Rome was the ideal of male “hardness” basically just being the top dog in the room. Women were the same in Ancient cultures if not expected to hold themselves differently but Skalds (the poets) describe the women just like the men.

Another thing quite recently (1993 so really recent in terms of historical archives) is the idea of the surrogate son. Basically, if a man died with no son to inherit a surrogate son would be chosen over a daughter. It has recently been noted that they very well could have been describing the daughter as a surrogate son. Someone to take up that male role of head of the household. This suggests in the sagas we have noted women but there is also a possibility for women to be described with male traditional words because of the role they were playing.

And we have found tons of armor that looks ceremonially and some battle worn for women yep. All women could fight though it was excepted they could defend themselves and their home front. Against potential attackers and wild animals.

Plus in the 13th century, the Christians introduced the Law of Gulathing which were sets of rules for people to follow. Women were then banned from cutting their hair like men, dressing like men, or in general behaving like men. This suggests It was common enough for them to throw it in the laws that banned traditional things that Scandinavians did that did not fit the Christian narrative or way of life.

-- This is gonna go under the cut for the rest cause wow I got long lol.

Okay queer terminology. You’ll see lesbian which was women who fucks women. and you’ll see penetrator a lot. These were slave cultures also so the idea of sleeping with another citizen was defiling them you shouldn’t do it.

In Ancient Athens, you saw men preferred the company of men over women because they didn’t think women were of value they were only good for producing heirs. There was a thing called pederasty where a wealthy man in his 20s, the erastes, would court a young wealthy man from the ages of 13-19, the eromenos, and teach him and keep him as a lover. Their debate over Achillies and Patroclus for example wasn’t if they were sleeping together but who was fucking who really. Because Patroclus was older but Achillies was the hero so was he being emasculated or were they breaking the age rule? That was their debate cause these things mattered to them

They were kinda the exception to the citizenship rule. The Spartans felt the pederastry was weird because it involved citizens but they were all in with the homo. Obviously, this was all very public and you’d be scorned if they thought you were being penetrated.

All in all, being penetrated was something women and slaves did and the last thing you wanted to be was a woman.

Another thing to consider was these cultures had a lot of problems with excess. So too much sex or food and in Rome you were a uh Cnidus? Idk I can only spell it in Greek which is staggeringly unhelpful but basically, you can’t control your urges. Based off that time someone tried to fuck a statue I think or something like that

The Norse had a similar word ergi which meant you had too much heterosexual sex actually, you were too promiscuous. In the 12th century we know in Iceland homosexual acts like sodomy were banned under Christian canon (Thanks Richard I of England) so there is that. Pre-Christian influence there seemed to be no stigma around this minus don’t force yourself on your friends that’s rude but slaves were fair game. (I wrote a paper on the weird stereotypes of Vikings being the sexual aggressors when the literature of the time suggests the Lotharingians were way way more likely to commit those acts. At least according to French who were besieged constantly by everyone all the time.)

níð was an insult for the ancient norse which basically you had displayed unmanliness. Or you liked to take it up the ass to be plain about it. (Ancient people were vulgar as shit the Romans were obsessed with sexual threats to the point where its just in common day-to-day speech.) Ragr was a term that meant you were unmanly which is much more severe and you could like legally kill someone for saying that up till the 13th century.

There is actually some debate that the concept of unmanly comes from making fun of the Germans. So like if you were Ancient Germanic or Ancient Brittania you were the savages of the day. Which is interesting when you consider the rhetoric those two countries put out. Like literally no one like the Germans or the Brits they thought they were filthy uncivilized and cowardly people.