#a new england folk tale

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Anya Taylor-Joy - The VVitch (2015)

#anya taylor joy#the witch#folk horror#robert eggers#the vvitch#thomasin#2010s horror#2010s movies#a new england folk tale#2010s#2015

332 notes

·

View notes

Text

Credit: drea.d.art | IG

#drea.d.art#art#fanart#the vvitch#folk tales#horror#black phillip#thomasin#gothic#1630s#new england#satan#puritans#christian#movie art#robert eggers#gothcore#witchcore#witch#witchcraft#🖤

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝖙𝖍𝖆𝖙 𝖎𝖘 𝖓𝖔𝖙 𝖜𝖍𝖆𝖙 𝖞𝖔𝖚 𝖜𝖆𝖓𝖙, 𝖙𝖍𝖆𝖙 𝖎𝖘 𝖜𝖍𝖆𝖙 𝖞𝖔𝖚 𝖓𝖊𝖊𝖉. 𝖞𝖔𝖚 𝖆𝖗𝖊 𝖓𝖔𝖙 𝖒𝖆𝖉𝖊 𝖔𝖚𝖙 𝖔𝖋 𝖓𝖊𝖊𝖉𝖘, 𝖞𝖔𝖚 𝖆𝖗𝖊 𝖒𝖆𝖉𝖊 𝖔𝖚𝖙 𝖔𝖋 𝖞𝖔𝖚𝖗 𝖉𝖗𝖊𝖆𝖒𝖘 𝖆𝖓𝖉 𝖉𝖊𝖘𝖎𝖗𝖊𝖘. 𝖜𝖍𝖆𝖙 𝖎𝖘 𝖎𝖙 𝖞𝖔𝖚 𝖜𝖎𝖘𝖍 𝖆𝖓𝖉 𝖉𝖗𝖊𝖆𝖒 𝖔𝖋?

#mine#storyseekers#my edit#edit#horror literature#litedit#lit edit#literature edit#horror books#book tag#book quote#bookedit#book edit#horroredit#brom#gerald brom#slewfoot book#slewfoot#slewfoot : a tale of bewitchery#witch horror#folk horror#new england#new england gothic#aesthetic#horror aesthetic#book aesthetic#witchy aesthetic#dark aesthetic#historical fiction#horror fiction

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

@zeroatthebone @kelcipher

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think a big part of the reason why, even when Pratchett was alive, it was always Rowling who was held up as the gold standard of a modern British fantasy author, is that Pratchett was above all else just far more honest about like, The English writ large.

a lot of ink has been spilled on the saccharine nostalgia of Harry Potter books, particularly as they went on, that longing for the WW2 Blitz spirit that Rowling herself didn't actually live through, but is lionised in our culture and was subsequently regurgitated uncritically by her, on account of her being an unimaginative hack. "keep calm and carry on" is the core aesthetic of the later books, while the earlier ones are far more of the sort of irritating, faux-charming, brilliant baffling bouncing Britishness that captured the hearts of teaboos who knew no better around the world, and also presented a highly self-flattering image to the people who have to actually live on this shithole island. this was especially true of cultural institutions such as schools, libararies, etc, who found it germaine to push these middling children's books relentlessly on kids, while massive multimillion dollar movie projects were cranked out, because they were deeply, painfully in love with a cutesy mirage of England that we like to project to the world to cover for the fact that this place is the husk of a dead empire, inhabited by tiny islands of obscene hoarded wealth in an increasingly desperate sea of insane deprivation and poverty.

and on a certain surface-level reading, you could almost accuse Pratchett of doing the same thing. after all, he also wrote whimsical fantasy tales largely set in a transparently England-ish setting (that is, Ankh-Morpork and the surrounding countryside areas on the Discworld). they even feature lots of witches and wizards! his books are full of bumbling, good-natured Englishmen doffing their caps to the lord, scenic countryside vistas, dirty and yet charming city streets, bustling fairs, rascally pickpockets, and generally a lot of the same aesthetic signifiers of Rowling's earlier work especially.

but.

read any amount of Pratchett's stuff and you realise very quickly that he understands that there is a persistent, genuinely violent nastiness underpinning a lot of this stuff. I Shall Wear Midnight is a good example, as the honest, hard-working country folk of the Chalk never even acknowledge the shameful mob killing of the old toothless woman who Tiffany has had to bury. these charming communities are places where well-known cases of domestic violence go unaddressed until a pregnant girl is beaten so badly she has a miscarriage, and they are places where miserable, curtain-twitching sneaks spread lies and rumours with impunity. Guards, Guards! fits here as well, a book about how the not-insincere love of the people of Ankh Morpork for their new king is insane and destructive and ends up getting quite a lot of innocent people killed.

what i appreciate most about how Pratchett talks about this stuff is that neither the nastiness nor the more charming elements are artifice. while they seem to exist as a contradiction at first glance, a core feature of English culture from Pratchett's perspective is that these impulses exist in a tense balance at all times. Mr Petty hits his daughter until she miscarries, and also stings his hands gathering nettles to make a little grave for the poor kid before trying to hang himself. that doesn't make what he did ok, but it does mean grappling with the fact that people are complicated and don't make sense, culture doesn't entirely cohere, and that the things you might like about "Englishness" are part and parcel of some genuinely horrifying shit.

obviously i'm not going to sit here and pretend that Pratchett was some plucky underdog compared to Rowling, the dude had a knighthood, and there are even a few movies based on his stuff (I'm rather partial to the 2008 The Colour of Magic adaptation myself), although nothing on the scale of the Potter movies. but at a glance, it does seem strange that Rowling was our nation's marquis literary export in the 2000s, considering that Pratchett was more established, working in the same genre, and also a significantly more technically skilled and insightful writer than her. but, that's the thing, he was insightful enough that his writing didn't make for decent cultural slop like Rowling's did. Harry Potter is vapid enough for corporate interests and cultural institutions to build a multinational media empire on, not through some insidious conspiracy to poison the minds of a generation of irritating millenials, but because it was there and it was popular enough and it was easy to use, because it's not very complicated or challenging. Discworld is not perfect by any means, and i have my personal disagreements with Pratchett's (relatively) rosy perspective on humans as being fundamentally very decent. but the stories make you think, they encourage you to engage with the world critically, and they are written with a degree of empathy and kindness that clash with any earnest attempt to shore up "English values".

#“english” chosen quite deliberately here btw#not using it interchangably w british#discworld#i shall wear midnight#guards! guards!#terry pratchett#fuck harry potter#fuck jkr#long shiverposting

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

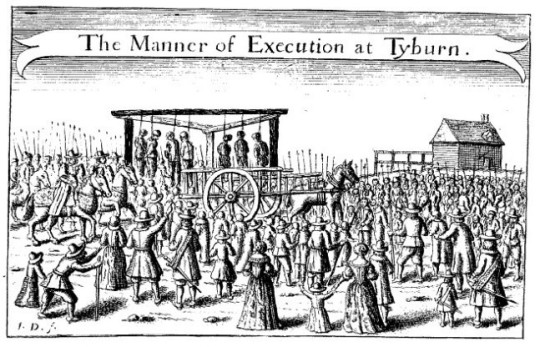

Ballads of the Hanged: Swinging from the Gallows Tree

A mixtape of execution ballads and assorted tales of guilt, wrath, terror, and defiance on the gallows, where all men are brothers.

[on spotify]

21 tracks, 1h 15min in full (spotify lacks one song)

I teased this many moons ago, and I finally finished it. No booklet in PDF form (too much hassle), but I got extensive liner notes, which you can also read here, for more pictures and a wider format. Enjoy!

LINER NOTES

1. Hans Zimmer - Hoist The Colours

Heave ho thieves and beggars never shall we die

What a heartbreaking thing to say on the scaffold. But we have to start with theatrics and a drum roll, and our introduction needs no introduction.

2007, from Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End OST lyrics: Ted Elliott & Terry Rossio music: Hans Zimmer & Gore Verbinski

2. Shirley Collins - Tyburn Tree (Since Laws Were Made)

Next stop, Tyburn: England's most notorious gallows. In The Beggar's Opera, the highwayman Macheath (later also known as Mack the Knife) observes that if they hanged rich criminals like they hang the poor ones, "'twould thin the land". Shirley Jackson subtly changed this to the better.

Since laws were made for ev'ry degree to curb vice in others as well as me, I wonder there's no better company on Tyburn Tree.

But since gold from laws can take out the sting, and if rich men like us were to swing, it would rid the land their numbers to see upon Tyburn Tree.

recorded 1966, released 2002 in Within Sound lyrics: John Gay, from The Beggar's Opera, 1728 music: traditional ("Greensleeves"), 16th century

3. Joan Baez - Long Black Veil

A country ballad about a man falsely accused of murder, who lets himself get dragged to the gallows because he won't reveal his alibi: an affair with his best friend's wife. It's been covered by a million people, here's Baez live.

The scaffold is high, eternity near, She stands in the crowd, she sheds not a tear, But sometimes at night, when the cold winds moan, In a long black veil she cries o'er my bones.

1963, from In Concert Part 2 lyrics & music: Lefty Frizzell, 1959

4. Oscar Isaac with Punch Brothers & Secret Sisters - Hang Me, Oh Hang Me

A poor boy who got "so damn hungry he could hide behind a straw", made his last stand with a rifle and a dagger, and has been all around this world, and is positively done with it.

They put the rope around my neck, they hung me up so high Last words I heard 'em say, won't be long now 'fore you die Hand me, oh hang me, and I'll be dead and gone Wouldn't mind the hanging, but the laying in the grave so long

2015, from Another Day, Another Time: Celebrating the Music of "Inside Llewyn Davis", after Oscar Isaac's rendition in Inside Llewyn Davis, 2013, in turn after Dave Van Ronk's rendition in Folksinger, 1962 lyrics & music: traditional American/unclear origin, folk song with various titles (I've Been All Around This World, The Gambler, My Father Was a Gambler, The New Railroad), first recorded by Justis Begley, 1937

5. Chapel Hill - Seven Curses

Cover of a Bob Dylan song, telling us the dark tale of a judge who's about to send a man to the gallows for stealing a horse, promises his daughter he'll show clemency if she agrees to sleep with him, and then reneges on his promise.

The next morning she had awoken to know that the judge had never spoken she saw that hanging branch a-bending she saw her father's body broken These be seven curses for a judge so cruel

2013, from One For The Birds lyrics inspired by Judy Collins's "Anathea" (1963), in turn inspired by the traditional Hungarian ballad "Feher Anna", who curses the judge "thirteen years may be lie bleeding" lyrics & music: Bob Dylan, recorded 1963, released 1991 in The Bootleg Series

6. Ewan MacColl - Go Down Ye Murderers

A song about Timothy Evans, a man accused of murdering his wife and child, which he denied until his last breath. They convicted him and hanged him in 1950. He was 25 years old. Three years later the real murderer, his neighbour John Christie, confessed, and the case played a major role in abolishing capital punishment in the UK.

The rope was fixed around his neck, and the washer behind his ear And the prison bell was tolling but Tim Evans did not hear Sayin' go down, you murderer, go down

They sent Tim Evans to the drop for a crime he didn't do It was Christy was the murderer, and the judge and jury too Sayin' go down, you murderers, go down

1956, from Bad Lads and Hard Cases: British Ballads Of Crime And Criminals lyrics & music: Ewan MacColl

7. Jennifer Lawrence - The Hanging Tree

One of the stranger things that can happen at the hanging tree is camaraderie. "On the gallows tree, all men are brothers", to quote A Feast for Crows, and when the state murders, then in defiance, an execution ballad can become a protest song. Many have in real life, this one is fiction, from The Hunger Games. Wisely, the director asked the composer for a simple tune, nothing elaborate, something that could be "sung by one person or by a thousand people".

Are you, are you coming to the tree? Wear a necklace of rope side by side with me Strange things have happened here, no stranger would it be If we met at midnight in the hanging tree

2014, from The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1 OST lyrics: Suzanne Collins music: James Newton Howard

8. Let's Play Dead - Heaven and Hell

A fairly traditional execution ballad written recently for the series Harlots. Margaret Wells sings it to herself for consolation and courage, as she sits alone in a cell, waiting to get dragged to the gallows.

I'm no more a sinner than any man here I'm no less a saint than the priest at god's ear But now I am snared, they will punish me well With a ladder to heaven and a rope down to hell

2018, from the single Heaven and Hell, for Harlots Season 2 Episode 7 lyrics & music: Let's Play Dead

9. Odetta - Gallows Pole

Probably the most well-known execution ballad of the 20th century, thanks to several iconic renditions. This one remains my favourite.

Hangman, hangman, slack your rope, slack it for a while I think I see my father coming, riding many a mile Papa did you bring me silver, did you bring me gold? Or did you come to see me hanging by the gallows pole?

1960, from At Carnegie Hall lyrics & music: traditional (Child 95 / Roud 144), known under many other titles ("Hangman", "The Maid freed From the Gallows", "The Prickle-Holly Bush"); this version is directly influenced by Lead Belly's "Gallis Pole" (1930s), and they both informed Led Zeppelin's 1970 version

10. Johnny Cash - 25 Minutes to Go

Peak gallows humour, uproariously funny and defiant, and somehow still conveying the terror of a man who's about to die and emphatically doesn't want to. Performed live at Folsom Prison.

Then the sheriff said boy I'm gonna watch you die, 19 minutes to go So I laughed in his face and I spit in his eye, 18 minutes to go Now here comes the preacher for to save my soul, 13 minutes to go And he's talking about burning but I'm so cold, 12 minutes to go

1968, from At Folsom Prison lyrics & music: Shel Silverstein, from his 1962 album Inside Folk Songs

11. Johnny Cash - Sam Hall

A classic execution ballad with many versions (see here for its complicated history), some of which are stoic and dignified, and others humorous. But this one brims with rage. Sam Hall will not be repenting on the gallows, and he'll see you all in hell.

My name it is Sam Hall and I hate you one and all And I hate you one and all, damn your eyes

2002, from American IV: The Man Comes Around lyrics & music: : traditional, 18th century broadside ballad, Roud 369

12. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds - Up Jumped the Devil

A song about a man doomed from the start to play the villain’s part, and the origin of this blog’s #swinging from the gallows tree tag.

Who's that hanging from the gallow tree? His eyes are hollow but he looks like me Who's that swinging from the gallow tree? Up jumped the Devil and he took my soul from me

1999, from Tender Prey lyrics: Nick Cave music: Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds

13. NOT ON SPOTIFY: Dead Rat Orchestra - The Black Procession

This ballad imagines a sinister procession of 20 criminals (black tradesmen brought up in hell!), each with their own specialty (it's mostly thieves of some sort), on the way to the gallows. The last and worst of them is the thief-catcher, and if one of them is innocent, they'll all go free. But of course none of them are. It's written in thieves' cant (lyrics and more context here), and the chorus means: "Look well, listen well, see where they are dragged, up to the gallows where they are hanged."

Toure you well; hark you well, see where they are rubb’d, Up to the nubbing cheat where they are nubb’d.

2015, from Tyburnia: A Radical History Of 600 Years Of Public Execution lyrics: from The Triumph of Wit by J. Shirley, 1688 music: Robin Alderton, Daniel Merrill & Nathaniel Robin Mann

14. John Harle & Marc Almond - The Tyburn Tree

And where does the Black Procession lead? To Tyburn, of course. The dark gothic side of Marc Almond.

The Tyburn Tree, I weep for thee, blood in the roots 'Tis not a tree with bark and leaves of spring awakening 'Tis not a tree with blossom and fruit, 'tis not a tree No boughs to bend beneath the unruly breath of winter No memories of woods warmed by spring's sweet touch 'Tis not a tree — take a ride to Tyburn and dance the last jig

2014, from The Tyburn Tree (Dark London) lyrics: Marc Almond music: John Harle

15. CocoRosie - Gallows

Speaking of dark and gothic.

They took him to the gallows, he fought them all the way though And when they asked us how we knew his name We died just before him, our eyes are in the flowers Our hands are in the branches, our voices in the breezes And our screaming is in his screaming

2010, from Grey Oceans lyrics & music: Sierra Rose Casady & Bianca Leilani Casady

16. The Tiger Lillies - Hang Tomorrow

In their Two Penny Opera, the pioneers of dark cabaret reimagine Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, and take all the suaveness out of Mack the Knife. Here they also take all the fight out of him. What's even left? A pathetic empty husk, a bastard (let's not forget that Brecht's MacHeath is no rogue with a heart of gold, he's a horrible man) who can't even be intriguing. How disturbingly pedestrian.

So here I am in jail again, oh god it stinks of piss I've been in here since I was young, so I can reminisce It's looking rather grim this time, it's looking rather bad But if I swing tomorrow in some ways I'll be glad

2001, from Two Penny Opera lyrics & music: Martyn Jacques

17. Tom Hollander - Ballad In Which MacHeath Begs All Mens' Forgiveness

In The Threepenny Opera, Mack the Knife stands on the scaffold and asks for pity. No point being judgmental now, that he's about to die. He morbidly describes how his dead body will end up, and then he lashes out at everyone, cops and criminals (same difference), while still begging them all for forgiveness. Very VERY sarcastically. The ballad's concept is borrowed from François Villon (see below), and this translation is unusually bold (honorific, see here and here for other translations and context).

You crooked cops with your Mercedes, your mobile phones, your trendy jackets, your cuts from drugs and dice and ladies, your Scotland Yard protection rackets.

Let heaven smash your fucking faces, slash you and let the blood run free and break you in a thousand places. I've pardoned you. You pardon me.

1994, from The Threepenny Opera - Donmar Warehouse Original Cast lyrics: Bertolt Brecht 1928, loosely inspired by François Villon's "Ballad of the Hanged" c. 1489, translated by Jeremy Sams 1994 music: Kurt Weill 1928

18. Saga de Ragnar Lodbrock - Ballade des pendus

And here's the OG Ballad of the Hanged, written in the 15th century by the OG poète maudit, François Villon (translation here). It paints an indelible picture of strung up corpses swaying in the wind, decaying, pecked by birds, ravaged by the elements and time. And crucially, it's in the first person. The hanged speak, begging their fellow-humans for pity, and god for forgiveness.

Frères humains, qui après nous vivez, N'ayez les cœurs contre nous endurcis, Car, si pitié de nous pauvres avez, Dieu en aura plus tôt de vous mercis. Vous nous voyez ci attachés, cinq, six: Quant à la chair, que trop avons nourrie, Elle est piéça dévorée et pourrie, Et nous, les os, devenons cendre et poudre. De notre mal personne ne s'en rie; Mais priez Dieu que tous nous veuille absoudre!

recorded 1979, released 1999 in the Saga de Ragnar Lodbrock reissue lyrics: François Villon, c. 1489 music: Saga de Ragnar Lodbrock

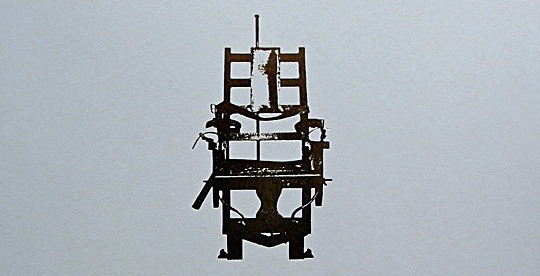

19. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds - The Mercy Seat

Honorary inclusion, a song not about hanging: the mercy seat is the electric chair. But the lyrics are a punch and this is a torrent of a song, a whirlwind, a masterpiece, a 7-minute cynic snarl. So it couldn't possibly get left out of this compilation.

And the mercy seat is awaiting, and I think my head is burning And in a way I'm yearning to be done with all this measuring of proof An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth (a life for a life and a truth for a truth) And anyway I told the truth, and I'm not afraid to die (and I'm afraid I told a lie)

1999, from Tender Prey lyrics & music: Nick Cave

20. Graveyard Train - Ballad For Beelzebub

And after? Welcome to Hell, ladies and gents, and bards. (Bards are rogues, too.) The Graveyard Train play a kind of Southern Gothic (but very southern, they're Australian), and here they entertain the thought of a band that ends up in hell and has to keep playing, without end, for an audience that can't hear. What a bleak prospect.

Well the air on the stage is burning our lungs And we're all going deaf from the beating drums And you can't see a thing for all the blood and the sweat in our eyes

Well we played till we died, and now we're all dead But the Man says we got to get up there again And you can't come down till the brimstone turns to ice

2008, from The Serpent And The Crow lyrics & music: Graveyard Train

21. Samuel Kim feat. Colm R. McGuinness - Hoist the Colours

Yo ho, all together Hoist the colours high Heave ho, thieves and beggars

But we won't end in hell. The only acceptable ending to this compilation is the triumphant version (wait for it) of its beginning: a pirate's end. Traditionally the gibbet, yes, but also the ghost ship that still sails, the ripple that still travels, and the story that still gets told.

Did I stutter the first time?

NEVER SHALL WE DIE

#long post#swinging from the gallows tree#mixtape#trs#prison ballads#pirate#bard#The Threepenny Opera

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Midnight Pals: Sorry if i scared you

Mae Murray: Submitted for the approval of the midnight society, i all this the tale of the girl who gets possessed by her sentient abortion Murray: but don't worry, this abortion just wants to have fun Murray: abortions just wanna Murray: they just wanna Murray: abortions just wanna have fun

Murray: so this story is about odie Dean Koontz: :) Murray: who is NOT the dog from Garfield Koontz: :(

Murray: odie has an abortion but it doesn't really take Murray: instead it possesses her body Murray: and makes her dance Murray: and kill her rapist Mary Shelley: haha yes… YES! Murray: and also some shitty cops George Romero: haha yes… YES! Romero: ACAB, baby!

Murray: as a real southern queer, odie goes to the big queer club in Little Rock Murray: she looks around at all the real southern queers, real salt of the earth folks, not like those fancy pants snob queers you get up in New England King: hey! King: now hold on a gosh darn second here!

Murray: as a southern queer, odie thinks about how much pride she has as a southern queer but also as a member of the southern queer community Murray: as a southern queer, you gotta express your pride

King: gosh mae there's some pretty unbelievable stuff happening in this story! Murray: you don't believe a woman could be possessed by a sentient space abortion that leads her to kill her rapist? King: no i mean King: i didn't know there were queers in the south Murray: Murray: you've never been lower than new Hampshire have you? King: whoa i don't go to new Hampshire! King: i heard there's dragons there

King: but actually i was referring to this bit where armadillos eat a corpse King: i mean, come on, really? King: i just don't buy it

King: I've seen armadillos and, goshdarnit, those little guys are just too cute to be corpse eaters Barker: what about the possum? you don't object to the possum? King: oh a possum would 100% eat a corpse

Barker: but it's equally cute King: it most certainly is not King: have you ever even seen a possum clive? King: awful animals Koontz: i think all animals are good Barker: hey that's real nice dean

Murray: what do any of you even know about armadillos? Murray: you're all a bunch of high falutin' yankees Murray: as a real southern queer of the real south Murray: i know armadillos

Murray: i'm real southern pride! Murray: i eat the cheese dip trail and shit E. Fay Jones's Thorncrown Chapel in Eureka Springs!! My daddy was the deliverance banjo boy and my mama was a big pot of okra!! Barker: how mushy was that okra? Murray: SO MUSHY!

Murray: after having completed everything it needed to do, the sentient abortion says "i have to go now. my planet needs me" Murray: that's right, it was from space the whole time! Poe: that raises a lot of questions Murray: we're not gonna talk about that

Murray: anyway, who's up for a real southern treat? Murray: i brought you all some deep fried chicken innards! Poe: King: Barker: Koontz: Lovecraft:

King: when you say innards, you mean meat right? Murray: um well Murray: it's technically "meat" in that it was part of an animal

Murray: you know those parts that you usually don't eat, on account of them being too disgusting? Murray: you know, the parts generally considered unfit for human consumption? Murray: that you might feed to a dog that you don't particularly like? Poe: King: Barker: Koontz: Lovecraft:

Mary Shelley: sup fuckers? Shelley: i hear you got the forbidden meat? King: mary no! Shelley: i'm not scared of no meat, i'll give it a- Shelley: WHAT THE FUCK IS THAT Murray: deep fried bladder Shelley: ewwwww Shelley: you deep fry it????

Shelley: that's disgusting, that is Shelley: where i come from Shelley: you don't deep fry that shit Shelley: you put it in a pie

Murray: oh i got a pie for you Murray: real heads know

#midnight pals#the midnight society#midnight society#stephen king#clive barker#edgar allan poe#dean koontz#hp lovecraft#mary shelley#mae murray#george romero

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

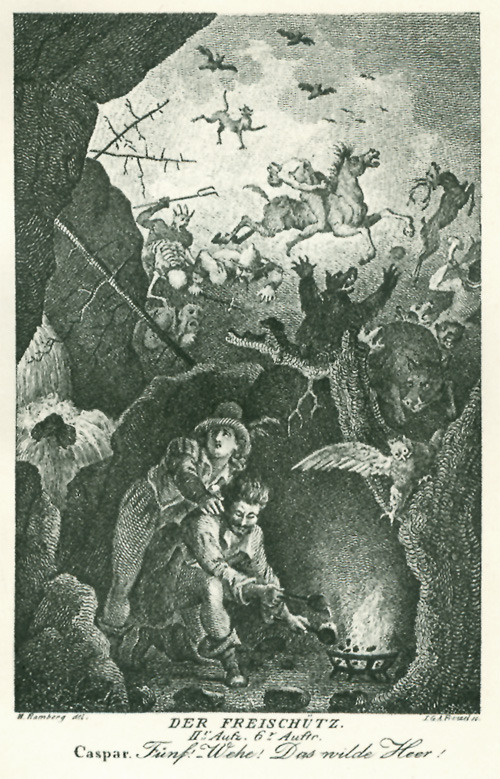

Frau Gauden

In the German region of the Prignitz, Frau Gauden (Mrs. Gauden) is the leader of the Wild Hunt. She leads this army of supernatural hunters together with her 24 dog-shaped daughters.

The Wild Hunt, also known as the Wild Army or the Wild Ride, is the German name for a folk tale widespread in many parts of Europe, particularly in the north, which usually refers to a group of supernatural hunters who hunt across the sky. The sighting of the Wild Hunt has different consequences depending on the region. On the one hand, it is considered a harbinger of disasters such as wars, droughts or illnesses, but it may also refer to the death of anyone who witnesses it. There are also versions in which witnesses become part of the hunt or the souls of sleeping people are dragged along to take part in the hunt. The term “Wild Hunt” was coined based on Jacob Grimm’s German Mythology (1835).

The phenomenon, which has significantly different regional manifestations, is known in Scandinavia as Odensjakt (“Odin's Hunt”), Oskorei, Aaskereia or Åsgårdsrei (“the Asgardian Train”, “Journey to Asgard”) and is closely linked to the Yule season here. The reference to Wotin/Odin in the name Wüetisheer (with numerous variations) is also clear in the Alemannic and Swabian dialects; In the Alps, people also speak of the Ridge Train. In England the train is called the Wild Hunt, in France it is called Mesnie Hellequin, Fantastic Hunt, Hunt in the Air, or Wild Hunt. Even in the French-speaking part of Canada, the Wild Hunt is known under the term Chasse-galerie. In Italian, the phenomenon is referred to as caccia selvaggia or caccia morta.

The Wild Army or the Wild Hunt takes to the skies particularly in the period between Christmas and Epiphany (the Rough Nights), but Carnival, Corporal Lent and even Good Friday also appear as dates.

Christian dates have superseded the pagan dates, which see the Wild Hunt moving, especially during the Rough Nights. This period of time is assumed to be originally between the winter solstice, i.e. December 21st and, twelve nights later, January 2nd. In European customs, however, since Roman antiquity, people have usually counted from December 25th (Christmas) to January 6th (High New Year).

The ghostly procession races through the air with a terrible clatter of screams, hoots, howls, wails, groans and moans. But sometimes a lovely music can be heard, which is usually taken as a good omen; otherwise the Wild Hunt announces bad times.

Men, women and children take part in the procession, mostly those who have met a premature, violent or unfortunate death. The train consists of the souls of people who died “before their time”, that is, caused by circumstances that occurred before natural death in old age. Legend has it that people who look at the train are pulled along and then have to move along for years until they are freed. Animals, especially horses and dogs, also come along.

In general, the Wild Hunt is not hostile to humans, but it is advisable to prostrate yourself or lock yourself in the house and pray. Whoever provokes or mocks the army will inevitably suffer harm, and whoever deliberately looks out of the window, gaping at the army will have his head swell so much that he cannot pull it back into the house.

The first written records of the Wild Hunt come from early medieval times, when pagan traditions were still alive. In 1091, a Normannic priest named Gauchelin wrote about the phenomenon, describing a giant man with a club leading warriors, priests, women and dwarfs, among them deseased acquaintances. Later references appear throughout the High and Late Middle Ages.

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

She Rings Like a Bell Through the Night: Chapter 7

Taglist Form

Series Masterlist

Ao3 Link

Bridgerton Masterlist

Pairing: Vampire!Anthony Bridgerton x Witch!fem Reader

Summary: The Witch makes her way through the beginning of the 18th century and encounters someone with ties to Anthony

Word Count: 2.3k

Warnings: 18+ for the overall fic. Specific to this chapter: nothing much, it’s a tame chapter compared to the ones that came before it. Minors DNI. I will put this up on Ao3 so please do not repost my work elsewhere

Author’s Note: And we’re back after a break for the New Year! Please do enjoy this part! Thank you as always to @fayes-fics for being the best and most patient beta reader

England 1700-1750

You spend the next few years traveling around England, staying on the fringes; unsure of how the tiny villages you encounter, so much like the one you came from, would receive a wanderer; a woman no less. You only enter on their Market Days, taking care to conserve the coins Anthony gave you while purchasing the necessities you need to survive on your own.

As the new century dawns, so too does your confidence. You begin engaging with local townsfolk and even dare to linger in the small hamlets, taking people up on their offers of hearth and hospitality as they perceive you to be a wandering orphan. You don’t disabuse anyone of that notion and you repay their kindness by assisting in cooking and other chores.

You are ten years or so into your explorations when one night, intending to camp in the woods, you encounter a group of women gathered around a bonfire. From a safe distance, you observe that they are a diverse group in age. You watch as they work together, some of them cooking a meal while others set up tents made from a riot of colorful fabrics.

Curiosity gets the better of you and you approach them. They welcome you into their circle without question, offering you a mug of ale and a bowl of hearty stew in exchange for your story. In their warm company, you find yourself pouring out the story of your early life, leaving out Anthony and your extended mortality. As you share the details of how you were treated by your grandfather and the village, you find comfort and understanding in these women. Many of them share similar stories and you learn that they live and travel together, finding safety in numbers.

And so you find your first coven.

As you travel together, each woman shares the folk remedies and tales from their respective villages and in turn, you share your own. Once settled into your own tent made of billowing bright blue and gold-patterned fabric that you had found and had fallen in love with while shopping at a market one day, you set to work by candlelight, filling page after page of your Book of Shadows with folk magic, learned from these women.

Over the years, women come and go. Some settle into the villages you encounter, while others are there one day and then gone by the time night falls. If anyone takes note of how little you age, no one mentions it.

One evening, an elegant older woman joins the group. She sits beside you, cautiously setting down her satchel. You smile and offer her a mug of ale and a bowl of stew, just as you once were. She smiles at you, grateful, taking the ale but politely declining the stew.

Rather than observe the group as a whole, she watches you. An odd feeling prickles under your skin as something about this woman and her clear, blue eyes strikes you as familiar but you are certain you have never met before.

“That is a lovely dress you’re wearing, my dear,” she says quietly.

It’s the pale blue dress Anthony had given you that had once belonged to one of his sisters.

The woman stares at your dress for a long moment before her eyes fall on your pendant. As she studies it, you feel a fizzing of magic you once associated with Anthony. Without asking, she reaches out and takes your wrist, her thumb gently brushing over the place he drank from you, though you bear no marks of it.

The woman releases your wrist and murmurs a quiet apology before taking up her bag and mug of ale and moving to another spot in the circle.

You’re not sure what happened, but you have a feeling the woman will be gone by morning and will never be seen again.

Later that night, settled back in your tent; after having not thought of him for years only to have invoked thoughts of him earlier, you have your first dream about Anthony.

In the dream, you’re standing in the lake beside your village, the remnants of Anthony’s concealment spell burning away. As the magical fire blazes, strong arms encircle you, pulling you into a warm embrace from behind. Closing your eyes, you inhale his scent: warm, rich and smoky. He presses a trail of kisses into your neck as you reach back to tangle your fingers into his hair. There is so much you want to say and yet, no words emerge. You sigh and bask in the feel of him, the familiar heat of his body, his breath warm against your cheek. You turn in his arms to face him and even in the dark, his eyes glitter. He opens his mouth to speak.

And that’s when you wake up, sunlight peeking through the gaps in the fabric of your tent.

With a frustrated huff, you smack the sheets under you and get up in favor of burrowing yourself back under the covers. You go about the day, doing your chores and assisting newcomers in learning the ways of the group. Just as you thought, the woman from the night before is nowhere to be found.

But then night falls and she appears again. Though she sits a distance away, you can’t help but notice those wise eyes of hers studying you. And so, you watch her in turn. While she is polite to those around her, she rarely engages in conversation. Once again, she refuses supper but partakes in the offer of ale, sipping slowly from her mug.

When you make your goodnights to the group, she too stands, following as you make your way to your tent. You stop abruptly and turn to face her. Her eyes go wide and she raises her palms up in front of her as if taming a wild horse.

“Forgive me,” she starts quietly. You nod and she continues, “The dress you wore last night, I am certain it used to belong to one of my daughters.”

Your breath hitches as you realize who she is. “The dress was a gift,” you tell her.

Her eyes widen and her voice is full of hope as she asks, “From Eloise?”

You think of the neat letters ‘EB’ stitched into the collar of the dress. You shake your head. “No, Lady Violet. Anthony gave it to me.”

Rather than look surprised, her eyes flick down to glance at your wrist. “Ah, that explains it,” she says sagely. At your questioning look, she adds, “I sensed his magic within you. And now I understand. You share a blood bond.”

Your eyes widen as you squeak, “We share a what?”

Lady Violet’s eyes soften even further. She gestures to your tent. “Perhaps it’s best if we talk in there.”

You nod and then pull open the curtain to let her inside. You light a lantern and gesture for her to sit on a stool while you sit on your bedding.

Lady Violet is silent for a moment as she takes in your living space. Her eyes land on your tiny, portable writing desk and your old satchel, the edges of your Book of Shadows peeking out of the top.

“You are far older than you appear, aren’t you, My Dear?” There is nothing accusing in her tone, just mere curiosity.

You swallow thickly and then, over the next several hours, pour out everything to her, the details you’ve shared with the coven and so much, much more that you haven’t, talking about Anthony and your brief but impactful time together, speaking his name aloud for the first time since you parted ways. All the while, Lady Violet is attentive, fascinated by every detail. Wisely, you leave out the more intimate details but she seems to understand what you infer. It’s when you try to explain how you first shared your blood and then later drank from him that she at last interjects.

“Partaking of each other’s blood, is how you became bonded. There will always be a connection between you,” Lady Violet tells you softly.

Absently, you rub your pulse point. “Why didn’t he tell me?”

Lady Violet reaches out to take your hand. “That I cannot answer. Perhaps he didn’t want to scare you.” Her response makes sense and it reminds you so much of Anthony that you feel a momentary ache behind your ribs at the thought of him.

The candle within the lantern catches your eye as you realize how late the hour truly is. “There isn’t much time until daybreak. Surely you must hide somewhere and rest?”

She too observes the lantern and nods. “You’re right. I ought to go. I’ve been staying in a cave nearby.”

The idea that this kind, elegant woman has been living in a cave makes you feel incredibly sad. She deserves better. An idea forming, you take up the lantern and hand it to her. Perhaps it’s time for the next chapter of your journey.

As you accompany her to her makeshift home, you talk more. She insists you drop the ‘Lady’ part of her name as she hasn’t felt like one in a very long time. Once she’s settled, you depart with plans for her to rejoin the camp as soon as it’s safe for her to do so the following evening,

Once back with the group, you manage a few hours of sleep. When you awaken the next day, you pack up your things and, over breakfast, inform the others that you will be parting ways with them that evening. Over the course of the day, you receive small gifts and well-wishes from members of the coven. You feel a genuine pang of sorrow at parting from this, the first true community you have ever known.

Dusk has settled when Violet arrives, her meager possessions stuffed into the three satchels she carries. You direct her to put them into the back of a small, single horse-drawn cart you had purchased earlier in the day. She climbs up to sit and you give your new horse, a fine, jet-black mare you named Midnight an apple and a gentle pat before sitting beside Violet and taking up the reins. The group follows behind for a bit, offering their goodbyes and then you’re on the road, traveling through the countryside to make your way through villages and burgeoning towns.

For the sake of safety, you both resolve not to spend longer than a few weeks at a time in any one place. By day, you stay at your chosen inn, covering and shutting the windows tight so Violet can rest undisturbed. You find warm reception by the townsfolk you encounter as they presume you are a mother and daughter traveling together. You spend a few hours exploring the local area, befriending villagers and learning their customs, before you too, return to your room for the afternoon to sleep so you can spend the evening with Violet.

As you travel around the country together, you learn what it is to have a mother. Violet is cheerful and doting. If she suspects you have neglected eating during the day while she’s slept, she insists on making sure you eat an extra hearty supper. And while she seems content in her travels with you, you can sense her sadness at the loss of her children. You never pry and eventually she gives you details about them all. If you seem extra attentive whenever she mentions Anthony, she is far too kind to call you out on it.

One evening, when you’ve been traveling together for nearly thirty years, Violet sits you down in a quiet corner of an inn in a port city and informs you that it’s time to part ways. Tears immediately spring to your eyes and before you can protest, she reaches into her satchel. She pulls out a small pouch and presses it into your hand. You open it to find a single bead made of aquamarine. You look up to find her smiling gently at you.

“It’s a little something for you to remember me by, My Dear. The chain that holds your pendant should thread through it perfectly.”

Heaving a deep breath, you unclasp it and sure enough, the blue bead slides on with ease. Violet smiles as you put your pendant, now adorned with her bead, back on. You’re struck by how the stone bead reminds you of her kind eyes.

The next day, you book passage on a ship departing for the Far East that evening. That night, Violet sees you settled into your berth and then you walk back out with her to make your goodbyes. She gives you a fierce hug as you breathe into her shoulder, memorizing her scent. When the final call for departure is made, she makes her way down and watches as your ship departs.

She is a tiny dot in the distance when you move away from the ship’s rail and run a finger over the bead she gave you. Aquamarine symbolizes peace and that is exactly what she’s given you over the years you were together. She brought a calm into your life and managed to make you forget about the treatment you suffered at the hands of your grandfather. You know that when anyone asks about your family, for the rest of your days, you will only mention your adopted mother, Violet Bridgerton.

As England fades behind you and gives way to open water, you can only wonder what Asia has in store for you.

taglist: @queen-of-the-misfit-toys @faye-tale @cosmiclove330 @abridgerton @fiction-is-life @kmc1989 @alexandrainlove @ietss @multi-fandom-lover7667 @turtle-cant-communicate @liliac-dreamer @hottytoddyhistory @laniec03 @sky0401 @kwbaby24 @queenofmean14 @jtheteenagewitch

#anthony bridgerton x reader#anthony bridgerton#violet bridgerton#anthony bridgerton imagine#anthony bridgerton x you#anthony bridgerton fanfiction

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Occult Book Reviews: New World Witchery

This review is long overdue. I’ve been slowly working through this book for two years, because it spawned so many side-projects! I’ve gone on so many little research rabbit holes, that actually getting through the book itself has taken so much longer than I thought it would.

New World Witchery: A Trove of American Folk Magic is an introductory book on North American folk magic, geared towards practitioners. The author, Cory Thomas Hutcheson, is a folklorist with a PhD, which makes this book more credible and better-researched than other beginner witch books. It’s a survey of a lot of different types of folklore from different places and groups in the United States, and thus doesn’t go super in-depth on anything in particular, but that makes it a great jumping-off point. Hutcheson is conscientious about the way he presents the information, doesn’t claim expertise in groups or traditions that he’s not a part of, and cites his sources in the footnotes. He also has a casual writing style, so this book is accessible and easy to read, not dense. (Why don’t more scholars write books for laypeople?) It’s not really a guide to practical magic, but it is intended to be a resource for it: Like Kelden (see my review of The Crooked Path), Hutcheson carefully considers how one can apply folkloric ideas about witchcraft in the context of a workable practice.

Hutcheson seems a lot like me. Or at least, I relate to a lot of things he said in his introduction. He “spent an inordinate amount of time scouring our school library for anything remotely magical,” and then became obsessed with folklore. I became interested in occultism for similar reasons — if there was a way to do magic in this world, then I was sure as hell going to learn it. I’ve also been studying mythology and folklore pretty much since I learned to read. This book appeals to that part of me. Hutcheson says that he wrote this book for the purpose of helping Americans discover and develop their own traditions of folk magic, and that’s the thing I love the most about it.

It’s easy to feel like Europe and other places in the world are “more magical” than America. That’s partly because home feels mundane compared to unfamiliar places, but it’s also because a lot of books on witchcraft are based around European (and especially British) lore, places, and plants. In the introduction, Hutcheson describes a feeling of “dejection” that magic was part of “over there” in Europe and other exotic locales, and couldn’t be found at home. Then, he discovered that America had a rich tradition of folklore and folk magic:

Magic is everywhere. Which means, magic is here. I have been living with magic all along. Not only that, the magic around me was robust, alive, growing, and active. It stretched out across North America in all directions, leading me to encounter magical paths and traditions that I had been bumping into for years, but putting aside because they weren’t the same ‘over there’ magic I thought I was looking for.

This is exactly how I felt. I know logically that America has its folk magic and folklore; I have a book of New England folklore, and a book of campfire tales. But I do not feel as if I have a native folk tradition. I didn’t grow up with folk magic or devil tales, and I don’t perceive much magic here. That’s why I was so happy to have this book. It introduced me to a lot of new lore, and helped me know where to look for the rest of it. I still don’t feel like I have much magic in my immediate vicinity, but at least I’ve got a place to start.

Hutcheson naturally begins with defining witchcraft. His definition is much more folkloric than even Kelden’s. Kelden tried to outline the basic practices associated with witchcraft for a prospective practitioner, while Hutcheson tries to isolate the most common traits and behaviors associated with witches, both real-life and fictional ones. He associates witchcraft with practical (“low”) magic, with a wonderous and amoral relationship to an enchanted world (for better or worse), and with the passing along of one’s knowledge and skills to others. He determines that witches in folklore cast spells, fly, use talismans and charms, perform both malevolent and benevolent acts, usually suffer at the hands of villagers, and usually survive that suffering in one way or another (even if it’s in a ghostly form).

He lists a number of North American traditions of folk magic (of which there are many), and provides at least some information from all of them. Regarding closed practices, he uses an interesting metaphor: You are like a magpie, taking little shiny bits and pieces from various traditions, but picking up a bluebird feather does not make you a bluebird. You can take inspiration from others’ practices, but you can’t claim to be something you’re not. I also really appreciate his nuanced take on the concept of hereditary witchcraft: The idea of being marked as magical from birth is a really common superstition and motif in folklore, so the idea that one is “born” a witch has a lot of historical precedent. That’s part of why so many Wiccans latched onto “grandmother stories” to gain magical street cred. A lot of folklore is passed down through families, and some of it is magical, or has magical applications.

The subsequent chapters describe the sorts of things witches do, from a folkloric, historical, and practical perspective: folk medicine, baneful magic, divination, treasure-finding, flight, curse-breaking, spirit work, and so forth. Hutcheson is more concerned with covering historical examples of folk magic, or historical tales about magic, than teaching the audience how to do any specific thing. But he does include little DIY projects or spells about once per chapter. These are usually intended to be harmless and easily doable, which I appreciate, because one of the most frustrating things about historical magic (to me personally) is the amount of preparation and specific details that go into everything. Making a spicy tea is much easier than spending years learning herbal medicine, and making a dowsing rod out of a coat hanger is much more convenient than picking a specific kind of branch from a specific kind of tree at a specific hour on Christmas Eve. In addition to the usual correspondence sheets, Hutcheson describes what one is actually supposed to do with the herbs and stones and other objects, which I found particularly helpful. He also includes footnote citations and “recommended reading” at the end of each chapter (in addition to the bibliography), which makes it easy to do more in-depth research into each topic.

Boldly, Hutcheson includes two traditional rituals for invoking the Devil in a forest or at a crossroads. You kind of can’t have a book on witchlore without mentioning the Devil. Just as Kelden recharacterized the Devil as the benevolent-but-tricksterish Witch Father, Hutcheson draws a distinction between Satan, the Christian notion of the adversary, and the Devil, which he defines as a more generic folkloric idea that encompasses trickster archetypes from many different cultural contexts. This is further confirmation of the idea that I came up with while reading The Crooked Path: that Satan ends up fitting into all the mythological roles that aren’t (or can’t be) associated with God. He makes up for the lack of trickster gods. I honestly wish that there were more on the Devil in this book, since he’s such an intrinsic part of witchlore. One of the reasons for this review’s delay is because the book helped inspire the ongoing “Devil project” that I’ve been intermittently working on, examining the Devil as though he were a trickster god. (I can’t promise when I’ll get around to finishing that, since I keep giving myself more reading material, but it’s still in the works.)

Hutcheson also goes out of his way to highlight just how prevalent magic is in everyday American culture, whether we realize it or not. Divination is a good example: You can buy tarot cards in any mainstream bookstore or novelty shop nowadays, and horoscope columns have been a staple of newspapers for about as long as they’ve been around (to say nothing of astrology apps). I didn’t think of cartomancy as being a “local” or “ancestral” tradition of folk magic, since I went out of my way to study tarot, but it is. My mother even taught me to read oracle cards, meaning, the skill was passed down by someone in my family (even if I’ve done more research since then). Hutcheson emphasizes that magic often “hides in plain sight,” through things like divination apps, or holiday superstitions, or simple rituals to honor the dead, or spooky children’s games played at sleepovers (like “Bloody Mary” or the “Three Kings” creepypasta). He also points out ways that completely mundane things can and have been utilized for magical purposes. There’s an entire chapter about standard magical ingredients in folk spells that can be found at a supermarket. Most of them are obvious: salt, lemons, rosemary, sugar, ginger, garlic, etc. Those ingredients are much more practical than attempting to find henbane or mandrake root, and they have just as long a history of magical use for the same purposes.

As I’d hoped, this book is helping me to look at folklore and determine which practical methods I can pull out of it. There’s a Scottish story of a group of witches who saved the Isle of Mull, the home of my distant ancestors, from the Spanish Armada. They raised a storm by making a makeshift pully out of a millstone and a rope that was flung over the rafters. The millstone was tied to the rope, and the higher it rose, the higher the wind. There it is — Scottish storm magic, preserved in a folktale concerning my own ancestors! I’ve also started looking more into New York folklore as a result of reading this book, and discovered a story about a “witch” in the Catskills that supposedly controls the weather and the sky itself for the entire area. I put “witch” in quotes because she sounded much more like a goddess than a witch; any old witch can control the weather, but governing the transition between day and night and hanging the new moon in the sky are the sorts of things that deities do. Is there a sky goddess in my own backyard?

Hutcheson also spends a chapter on the Satanic Panic, and other examples of persecution or legal issues around witchcraft in recent history. That’s a major piece of folklore, too. When people genuinely believe in magic, they also genuinely fear it, and that can turn ugly. This book is from 2021, but Hutcheson’s discussion of this issue is feeling particularly apt in today’s cultural climate. Scary and uncertain times — like the ones we’re headed into — are fertile breeding grounds for folk magic and superstition. Whether that will help or harm the occult community at large remains to be seen. On the one hand, I’m kind of excited to see which new superstitions arise, but I also may need to learn some discretion, in spite of myself. In the meantime, it’s important to remember that folk magic has always been a tool of the poor and marginalized, who turn to it when they have no other means of obtaining power or justice.

More than anything else, this book has been an excellent springboard for further research. The information in it is pretty surface-level, but it covers a lot of ground. It’s brought multiple traditions, techniques, and resources to my attention. It’s also given me additional context around what witchcraft is, especially in America, and what it can look like for modern practitioners. I got pretty much exactly what I wanted from it. I’ll have to check out his podcast, too!

#book reviews#book recommendations#witchblr#witchcraft#folk magic#folk witchcraft#folk witch#occultism#folklore#american folklore

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Greetings! I love-love-love your Fae Tales and exploration of the Faerie (and your other works as well) <3 Maybe this has been asked before, but I couldn't find the/a post. Do you have any recommendations for books or articles or websites (e.g. blogs) about the Fae (especially on the British Isles)? It's such an immense lore and I find myself somewhat at a loss on where to look and what to read. Thank you! <333

Hi anon,

Realistically, the best place to start that is free, is actually Wikipedia. And then probably going to your local library which is likely to have decent folklore compendiums (if not, go to your library's online database - which it should have - and get the library to order them in for you).

I've been reading folklore very intentionally (because I loved it and it was/is a special interest of mine) since I was a kid. There is no one book I could recommend for the British Isles, I've honestly never read one. I either read very broad compendiums that covered most of Europe, or I read very specific books based on a region. I have like 4-5 books on Orcadian (Orkney) folklore alone, as well as individual books for Wales, Scotland, England (and broken up into North and South England) etc.

The good news is a lot of folklore information is actually just freely available. On Wikipedia, the Scottish Folklore page for example is broken down into more links with literally like hours and hours and hours of reading and education there nicely organised with further links. And that's just one place you can start!

Outside of that, there are freely available books because they've moved out of copyright, that actually have really great folklore in them for the British Isles / UK. Project Gutenberg has a ton. And I've definitely read some of them!

I definitely think it's good to kind of comprehensively go through these before you even think about buying books mostly because folks don't realise that there is truly a bounty of free information since most books published have lapsed out of copyright and are now public domain. Also it's fun to just kind of go from place to place and realise you're never going to run out of stories to read and myths to learn about. It's too huge of a subject. :D And that makes it a lot of fun.

Right now, for example, I'm finally getting to a book about the Place Names of South Ronaldsay and Burray in Orkney, and it's a thick, incredibly well-researched book that does, in places, mention folklore and paganism. If you ever get so deep into research that you feel like you've mostly exhausted the internet, the next best thing is actually looking for small self-published / boutique published novels often only stocked at like idk 3 bookstores, they can be hard to find, but they're well worth it. I know the book I'm reading now probably doesn't have much reach outside of Orkney (I bought it while I was in Orkney), but the best folklore books I found were in tiny little bookshops in Orkney. And in the future if I needed to dive deeper into a region, I'd just email small bookshops and ask what titles they had on a subject, and if I could organise them to be sent to me, lol.

#asks and answers#pia on mythology#pia on folklore#folklore and mythology#i used to post a photo of my mythology/folklore shelves but truly truly#the internet is the best place to start#i have lost so much time (so much wonderful time)#to just reading on the internet#and this stuff started being put here as a repository of knowledge#for like over 20 years#so it's decades of information now!#administrator gwyn wants this in the queue

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

on the decolonial/postcolonial gothic

'introduction: decolonising gothic' by rebecca duncan in gothic studies vol 24 no 3 (2022, pp. 219-227)

'the gothic origins of anti-blackness: genre tropes in nineteenth-century moral panics and (abject) folk devils' by maisha wester in gothic studies vol 24 no 3 (2022, pp. 228-245)

'decolonial gothic' by sheri-marie harrison in the edinburgh companion to globalgothic (2023, pp. 23-37)

'jean rhys's wide sargasso sea (1966) - postcolonial gothic' by tabish khair in the gothic: a reader edited by simon bacon (2018, pp. 25-30)

'gothic tales of postcolonial england' by sarah ilott in new postcolonial british genres: shifting the boundaries (2015, pp. 54-94)

'arundhati roy and the house of history' by david punter in empire and the gothic: the politics of genre edited by a. smith and w. hughes (2002, pp. 192-207)

#gothic studies#reading recommendations#academia#my text#i think khair and wester's piece in particular are relevant to discussions around iwtv#the book chapters you should be able to get via 🏴☠️ but the journal articles may be harder to find. just msg me for a pdf if yr interested#keep in mind this is a v v small sampling based on my personal reading/uni experience. i will v much be getting more into it for my diss

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

📻🎶 H/D WIRELESS 2024 - WEEKLY WRAP-UP #1

🎶 Just a perfect week

Read fanfiction in the park And then later When it gets dark, look at art. Just a perfect week Reading at work in the loo, And then later a podfic, too And then home.

Oh it's such a perfect fest We're glad to share it with you Oh, such a perfect fest It just keeps us reading on, It just keeps us reading on. 🎶

🎤 Welcome to the 8th round of H/D Wireless Fest!

The time has finally come to start posting all the fantastic entries we’ve received this year!

We’ve revealed 9 top hits so far, with many more to come. The mods have been working non-stop since December to make this happen, so we’re beyond excited to finally be underway 🤩

As always you can listen to the prompted songs for the works we post on a playlists:

Click here for the YouTube playlist.

And now without further ado, our Wrap-up for the first week of posting:

🎶 H/D Wireless Art 🎶

📻 Fly Away with Me Tonight? [Gen, Digital Art]

🎵 Song Prompt: Levitating by Dua Lipa 🎵Summary: A chance meeting, an invitation to dance

📻 ghost (might as well be gone) [Gen, Digital ]

🎵 Song Prompt: Might as Well Be Gone by Pixies 🎵 Summary: Draco Malfoy retired from the Auror force and left England a decade ago, but he still receives the Daily Prophet. Today’s issue provides closure on the one case he was never able to officially solve.

🎶 H/D Wireless Fic and Art 🎶

📻 Trade My Heart For Honey [M, 64.170, Digital Watercolour]

🎵 Prompt: Water Under The Bridge by Adele 🎵 Summary: A Witch who thinks she’s a Seer, a Seer who thinks she’s a Witch, a former nemesis-turned-something-turned-acquaintance who thinks they could be friends, and a Scottish village full of Muggles who think this is as much their business as the fair folk in the woods. Draco is going to prove them all wrong.

🎶 H/D Wireless Fic 🎶

📻 You're on Your Own, Kid [E, 44.274]

🎵 Song Prompt: You're on Your Own, Kid by Taylor Swift 🎵 Summary: In August of 1998, Draco leaves behind everything he’s ever known. With the help of two middle-aged lesbians, a Muggle bookshop, and a new best friend, Draco’s future is finally looking up. That is, until Harry Potter wanders back into his life a year later, undoing everything Draco has worked towards. Or, a tale about healing, forgiveness, and living for no one but yourself.

📻 Heartbeat [E, 22,791]

🎵 Prompt: Heartbeat by Childish Gambino 🎵 Summary: Harry hates Draco, and Draco hates him in return. Only it's not hate, not even a little bit. Featuring: a cooperative independent study, golden hour on wrecked sheets, strawberries in the summer at Grimmauld Place, water from fountains of (dubious) origin, purple Mardi Gras beads, and a bird with silly legs. Also featuring: heated arguments, infidelity, unquenchable desire, and heartbreak. Over and over again.

📻 Long for Bliss! [E, 9,400]

🎵 Song Prompt: This Must Be It by Röyksopp 🎵 Summary: Harry has a tough decision to make: take the blue pill or the red pill. He chooses a pink one instead and throws caution to the wind. What blows back comes in the form of a blond fallen angel that talks like he’s the Devil and moves like he’s fucking. Or: Harry tries MDMA for the first time and unexpectedly encounters a mysteriously captivating Draco at KOKO London.

📻 Going Down Swinging [E, 4,661 ]

🎵 Song Prompt: Hello Mudduh, Hello Fadduh! by Allan Sherman 🎵 Summary: “Who are you?” he asked, feeling around for a truly abominable pair of glasses he fixed firmly above his nose. “I’m Draco,” he answered. “Draco—” He paused. It wasn’t that he couldn’t remember; it was that the memory wasn’t there.

📻 The Most He’s Ever Said [E,16,431]

🎵 Song Prompt: One of Your Girls by Troye Sivan 🎵 Summary: It takes them twenty years.

🎶 H/D Wireless Podfic 🎶

📻 [Podfic] A Different Kind of Meaning by p1013 [E, 01:42:57]

🎵 Song Prompt: 'Outnumbered' by Dermot Kennedy 🎵 Summary: The ceiling doesn't hold any answers, but there are cobwebs scattered across the corners with shadows tangled in their threads. The rug against his back is rough and scratchy, threadbare and devoid of colours other than various shades of brown. Harry takes it all in, absorbs the dingy and depressed state of his home. There's a pointed moment of decision, a note about to be played, a silence about to end, and then he rolls to his feet and sets to cleaning. It's the first constructive thing he's done in years.

#hd wireless#hd wireless 2024#drarry#drarry fic#drarry art#drarry podfic#drarry fic and art#weekly wrap up no 1

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I am that very witch

THE WITCH: A NEW ENGLAND FOLK TALE (2015)

238 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s Get Spoopy! 6 Queer Gothic Books for Halloween!

Happy Halloween, everyone! We did a queer horror-themed rec list in August to celebrate Frankenstein Day, so we thought we’d try something a little different: queer gothic stories! Here are our six recommendations for queer gothic works. Five Duck Prints Press folks contributed recommendations to this list.

Carmilla by J. Sheridan Le Fanu

In a lonely castle deep in the Styrian forest, Laura leads a solitary life with only her elderly father for company – until a moonlit night brings an unexpected guest to the schloss. At first Laura is glad to finally have a female companion of her own age, but her new friend’s strange habits and eerie nocturnal wanderings quickly become unsettling, and soon a ghastly truth is revealed.

What Manner of Man by St. John Starling

This is What Manner of Man, a queer vampire romance novel about an innocent priest sent to a remote island to exorcise the demons that are allegedly tormenting the villagers — but what happens when the priest begins to suspect his host, the mysterious, nocturnal lord of the local manor, may have invited him another reason entirely? And what happens when the supposedly celibate priest finds he cannot resist his host’s powerful charms?

Unspeakable: A Queer Gothic Anthology

Unspeakable contains eighteen Gothic tales with uncanny twists and characters that creep under your skin. Its stories feature sapphic ghosts, terrifying creatures of the sea, and haunted houses concealing their own secrets. Whether you’re looking for your non-binary knight in shining armour or a poly family to murder with, Unspeakable showcases the best contemporary Gothic queer short fiction.

Even dark tales deserve their time in the sun.

A Dowry of Blood by S. T. Gibson

Saved from the brink of death by a mysterious stranger, Constanta is transformed from a medieval peasant into a bride fit for an undying king. But when Dracula draws a cunning aristocrat and a starving artist into his web of passion and deceit, Constanta realizes that her beloved is capable of terrible things. Finding comfort in the arms of her rival consorts, she begins to unravel their husband’s dark secrets.

With the lives of everyone she loves on the line, Constanta will have to choose between her own freedom and her love for her husband. But bonds forged by blood can only be broken by death.

Silver in the Wood by Emily Tesh

There is a Wild Man who lives in the deep quiet of Greenhollow, and he listens to the wood. Tobias, tethered to the forest, does not dwell on his past life, but he lives a perfectly unremarkable existence with his cottage, his cat, and his dryads.

When Greenhollow Hall acquires a handsome, intensely curious new owner in Henry Silver, everything changes. Old secrets better left buried are dug up, and Tobias is forced to reckon with his troubled past, both the green magic of the woods and the dark things that rest in its heart.

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

In this celebrated work Wilde forged a devastating portrait of the effects of evil and debauchery on a young aesthete in late-19th-century England. Combining elements of the Gothic horror novel and decadent French fiction, the book centers on a striking premise: As Dorian Gray sinks into a life of crime and gross sensuality, his body retains perfect youth and vigor while his recently painted portrait grows day by day into a hideous record of evil, which he must keep hidden from the world. For over a century, this mesmerizing tale of horror and suspense has enjoyed wide popularity. It ranks as one of Wilde’s most important creations and among the classic achievements of its kind.

TELL US MORE QUEER GOTHIC BOOKS!

These books have been added to our queer horror shelf on Goodreads and our affiliate recommendation list on Bookshop.org!

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Love love love the omega verse fruk content! But, what do we think about omega Arthur accidentally getting pregnant in the 16th century and voila, FACE fam is born… something something “nation people don’t get pregnant even if they’re presenting omega and going through heat” but then new land is discover and “oops” turns out there is a reason why nation people have reproductive cycles

Oh nonny, do not unleash these thoughts on me! I tell you they will take root 🥺

See? Now I’m posting about it. I hope you’re happy! 😩

If this happened, I’m guessing it would be because of a very specific sets of circumstances. Otherwise nation-people don’t reproduce like humans do. When a new land is discovered, a successful settler population is established, with the main bulk of the settlers coming from an omega nation, and a significant portion coming from their alpha partner. And it had to be part of the New World, maybe? Like the clue is in the name. Just something about the Old World that makes it so no new nation-people are born the human way there any more. They used to be but it happened so long ago, when the Old World was new, that now not even China remembers. It’s become like an old wives’ tale to the nation folk. Anyway, all these boxes have to be ticked otherwise the new colony/nation-person comes into being the “normal” way and just appears one day. I kinda like this idea actually. Like a/b/o nations can have kids but such rare situations have to arise that they almost never do? And reproductive knowledge is still a loooot of guesswork back then too, so.

Soooo Francis and Arthur don’t bother with even the primitive precautions they had at the time. Why would they? The NA twins are the first new nation-people born this way in thousands of years, so the Dover pair had no idea they needed to be careful. Just carried on with their usual fooling around every time Arthur’s heat came, including on the shores of the New World. Like, literally on the shore, maybe? Francis is already there with the French colonists when he senses Arthur is near. Goes miles down the coastline close to where the English settlers are. Headcanon here that nation-people can travel much faster than normal humans so this doesn’t take him months, lol. Finds an English ship anchored and their personification alone on the beach. In heat and giving off an aura of STAY AWAY NORMAL HUMANS I LOVE YOU BUT FOR NO SPECIFIC REASON ENGLAND NEEDS SOME ALONE TIME WITH HIS FUTURE MATE ANCIENT ENEMY WHO HE STILL TOTALLY HATES SO GO INTO THE SETTLEMENT AND LEAVE YOUR MOTHERLAND BE UNTIL HE CALLS YOU, OKAY?

Arthur is all curled up in the sand like an overheated, grumpy merman. Scolds Francis for making him wait, then pulls him down and won’t even let Francis move them off the beach until they’ve done it a few times. Something about this heat has made it almost as bad as the first one and it started coming on halfway across the Atlantic. No amount of whining from Francis about sand in his hair or his new clothes getting ruined is going to make Arthur wait a moment longer for that knot. Even after Francis puts his foot down when the tide starts coming in and drags Arthur inland, they still keep at it. Marathon session that goes on and on until they’re both sore, sticky, and totally exhausted.

Francis: Needy this time weren’t we, mon lapin?

Arthur: Mmmm…*Sated omega sounds followed by three day sleep*

Francis stays by Arthur’s side and brings him food when he wakes up. He can’t explain why. He just…really wants to. Struts and sashays right into the English settlement, commandeers a kitchen and supplies, and just dares them to object, lmao. No one is that dumb! So Arthur gets a French feast when he wakes up. Then Francis keeps hanging around and staying close. Eventually a secretly pleased but outwardly embarrassed tsundere Arthur has to shoo him away back to his own lands. The food and aftercare are nice but people might start to talk and suspect, you know? They’re still supposed to be enemies.

Afterwards life carries on and things go back to normal. They get distracted by the day-to-day routine of being nations. So much so that Francis fails to notice when Arthur doesn’t call on him for help with his heats. It’s only when Arthur misses a third time that he starts to wonder. But then, Arthur was a late bloomer and their cycles are always a little wacky. Not so weird to skip a heat or two then have several close together. Francis isn’t too worried and neither is Arthur. Then he starts getting other weird symptoms. Often at hilariously inopportune times:

Arthur: *Mid Anglo-Spanish naval battle* Die, Catholic dog! You…

Antonio:….Yes?

Arthur:…One moment, please. *Dashes to the side of the ship to throw up*

Antonio:…Comida inglesa, ni siquiera una vez.

We’ve basically entered a pregnancy focused romantic comedy at this stage, lol. Not that anyone realises for a long time, Francis and Arthur included. It should be obvious: Arthur throwing up, not getting his heats, the alphas around him (even his enemies) suddenly not wanting to hurt him as much and pulling their punches when they fight, Francis wanting to stick around and be by his side, etc. It shouldn’t take a genius to work out what’s happening. But remember, hardly anyone knows Arthur is an omega at this point. Plus this kind of nation-person pregnancy is something that had passed into antiquity and become a myth. So everyone’s density is justfied.

In the end, it’s Alasdair who works it out first. He’s an alpha and Arthur’s older brother so his own protective instincts had to be going crazy. Which, on top of all the other changes Arthur is going through, the biggest telltale is his scent. Arthur’s brothers know him best out of everyone and, as the group’s sole alpha, Alasdair’s nose picks up what should be impossible. He thinks he’s wrong for months but the evidence keeps piling up. One morning he comes in to find Arthur slumped over with his head in a bucket as has become a common occurrence lately. Then, while Arthur’s good and distracted, Alasdair sneaks up to scent him. Then rips up his shirt and sees that barely there, slightly rounded middle. There’s no denying it then. Arthur’s omega nature and his “arrangement” with Francis was an open secret in the British Isles family. Arthur’s hastily put together potions and spells could disguise his scent enough to fool other nation-people, but not them. They all suspected but none of them, not even Alasdair, ever said anything out of respect for Arthur’s feelings. They knew what a blow it must have been for him. In spite of everything, they still care for the idiot, you know? He’s still their little brother.

Alasdair accuses Arthur in his ordinary, ultra blunt, Scottish way. Arthur brushes him off as being crazy. Alasdair leaves and comes back with Dylan and one of his books on the ancient history of their kind. Dylan is convinced, Arthur isn’t. You know how he is: denial all the way, baby! Dylan says Arthur is sick because the child needs to spend time in the New World where it will be born. Needs to soak up the energy of the land and the like. Otherwise…bad things, for both of them. Arthur says “you’re all crazy stop being crazy go away, crazy acting brothers of mine” but Alasdair says “right, then!” and just grabs Arthur up. Then, with Dylan’s help, they bundle their furious, spitting sibling onto a ship headed for Virginia. Alasdair goes with him. Meanwhile Dylan heads across the channel to tell Francis (“DYLAN DON’T YOU DARE DYLAN I WILL KILL YOU I SWEAR IF YOU SAY ONE WORD TO THE FROG-” - Arthur, probably). Francis is stunned by the news. Stunned and…cautiously ecstatic? I know he really wishes he could have a family in canon. Oh man, he would so want to believe this is real. But also be so afraid to get his hopes up because it sounds impossible. The drama! We love it. 🥺 Francis jumps on the fastest ship they have and sails to the English settlement to be reunited with Arthur. After a hilariously awkward conversation between the Auld Alliance duo (“…so, seems ye knocked up my little brother” “…oui, seems I did” “…aye, carry on, then” “merci”) Francis is allowed into the bedroom to see Arthur. Who’s still a Scottish prisoner, still in denial, and sulking like mad in a nest he made. Don’t ask him why he keeps wanting to make nests these days even though he hasn’t had a heat in ages. Well, you can ask but the only answer you will get is shut up and go away, dickhead. Arthur Bloody Kirkland is the face of the United Bloody Kingdom and he can make bloody nests if he bloody wants to! *Hissy tsundere noises*

Arthur tries to bluster at Francis to go away or better yet help him throttle Alasdair who’s obviously gone mental, but Francis doesn’t give him the chance. Just pounces and kisses Arthur, cheats shamelessly by using wicked lips and fingers on the omega spot on Arthur’s neck, making him go all loose and purry. Then Francis presses both their hands to Arthur’s stomach and they feel something move.

One of the NA twins - probably Alfred, I mean let’s be honest - waking up to say hello.

Even Arthur can’t deny it after that. Shocked and furious, he tries to rant at Francis (“WHAT THE FUCK HAVE YOU DONE TO ME YOU FUCKING FROG! THIS IS YOUR FAULT! I’LL FUCKING SKIN YOU FOR THIS-!” - Arthur, definitely) but Francis is crying too hard to notice. Then he’s laughing and sobbing at the same time: hugging Arthur, professing his love, and kissing his lips off. Arthur’s shock and fear based rage stands no chance in the face of Francis’s thousand years plus heartfelt yearning for a family. He gives in and lets Francis have his moment of ecstasy. The kissing soon evolves into something else and Francis almost loses control and gives Arthur a mating bite, but pulls back at the last second. They’re not ready for that. Arthur noticed. Arthur didn’t say he did. Arthur is secretly grateful and feels his heart flutter even so.