#U.S. Economic Reform Proposals

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Project 2025’s Economic Vision: A Critical Look at Proposed Reforms to Treasury Department Operations

As the United States braces for the upcoming economic changes proposed under Project 2025, the focus has shifted toward the Treasury Department and its role in managing fiscal policy. These proposed reforms, while aiming to streamline operations and enhance economic oversight, have raised concerns among experts and policymakers about their long-term implications on federal operations and the…

View On WordPress

#Economic Impact of Project 2025#Economic Vision for Treasury Policies#Federal Financial Operations Overhaul#Fiscal Policy and Project 2025#politics#Project 2025#Project 2025 Economic Strategies#Treasury Department Critical Analysis#Treasury Department Reforms#U.S. Economic Reform Proposals

0 notes

Text

Elon Musk and former President Donald Trump have proposed several initiatives that could impact the wealth of lower and middle-class Americans:

Implementation of Tariffs: Trump's administration has imposed tariffs on various imported goods, aiming to protect domestic industries. However, these tariffs have led to increased prices for everyday items, disproportionately affecting lower and middle-income consumers. For instance, tariffs on washing machines resulted in higher costs for American shoppers, outweighing the economic benefits for local workers.

WSJ.COM

Simplification of the Tax Code: Musk and Trump have considered overhauling the U.S. tax system, potentially moving towards a flat tax. While this could simplify filing, it might also eliminate deductions that benefit low and middle-income families, potentially increasing their tax burdens.

ECONOMICTIMES.INDIATIMES.COM

Reduction of Federal Spending: Appointed by Trump to lead the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), Musk aims to cut federal spending by up to $2 trillion. Proposed measures include reducing the federal workforce and eliminating certain government programs. Such cuts could lead to job losses and reduced services that many lower and middle-class individuals rely on.

FINANCE.YAHOO.COM

Dismantling of Foreign Aid Programs: Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency have been involved in dismantling USAID, affecting numerous health and development programs worldwide. Critics argue that while reform is necessary, abrupt shutdowns can have harmful impacts on aid-dependent regions and may also affect global stability, indirectly impacting the U.S. economy and its citizens.

NEWYORKER.COM

These initiatives, while aimed at economic efficiency and protectionism, carry potential risks for lower and middle-class Americans, including higher consumer prices, increased tax burdens, job losses, and reduced access to essential services.

Elimination of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB): Elon Musk has advocated for dismantling the CFPB, an agency established to protect consumers from unfair financial practices. Abolishing the CFPB could expose consumers to predatory lending and financial scams, disproportionately affecting lower and middle-income individuals.

DEMOCRATS-FINANCIALSERVICES.HOUSE.GOV

Proposed Cuts to Social Programs: The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), led by Musk, has proposed significant reductions in federal spending, including cuts to social programs like Medicaid and SNAP. These programs provide essential support to low-income families, and reducing their funding could lead to decreased access to healthcare and nutrition assistance.

FORBES.COM

Potential Impact of Immigration Policies: Trump's stringent immigration policies, including mass deportations, could lead to labor shortages in industries such as agriculture and construction, potentially driving up costs for goods and services. These increased costs may be passed on to consumers, affecting lower and middle-class households.

INDEPENDENT.CO.UK

#middle class#lower class#middle class wealth#politics#us politics#donald trump#political#news#president trump#elon musk#economics#economy#law#republicans#republican#policy#policy makers#law makers#class war#capitalism#late stage capitalism#capital gains#campaign contributions#anti capitalism#veteran#veterans affairs#doge

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

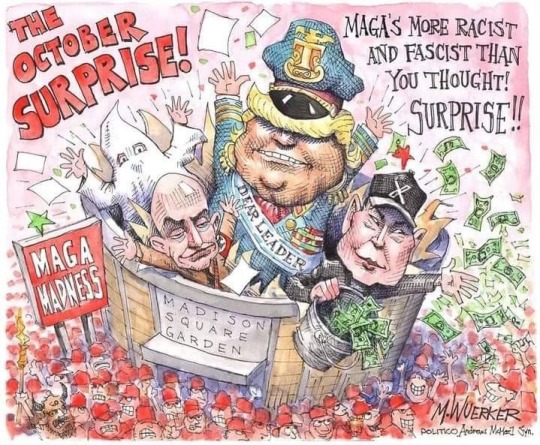

Matt Wuerker, Politico

* * * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

October 30, 2024

Heather Cox Richardson

Oct 31, 2024

On Friday, October 25, at a town hall held on his social media platform X, Elon Musk told the audience that if Trump wins, he expects to work in a Cabinet-level position to cut the federal government.

He told people to expect “temporary hardship” but that cuts would “ensure long-term prosperity.” At the Trump rally at New York City’s Madison Square Garden on Sunday, Musk said he plans to cut $2 trillion from the government. Economists point out that current discretionary spending in the budget is $1.7 trillion, meaning his promise would eliminate virtually all discretionary spending, which includes transportation, education, housing, and environmental programs.

Economists agree that Trump’s plans to place a high tariff wall around the U.S., replacing income taxes on high earners with tariffs paid for by middle-class Americans, and to deport as many as 20 million immigrants would crash the booming economy. Now Trump’s financial backer Musk is factoring in the loss of entire sectors of the government to the economy under Trump.

Trump has promised to appoint Musk to be the government’s “chief efficiency officer.” “Everyone’s going to have to take a haircut.… We can’t be a wastrel.… We need to live honestly,” Musk said on Friday. Rob Wile and Lora Kolodny of CNBC point out that Musk’s SpaceX aerospace venture has received $19 billion from the U.S. government since 2008.

An X user wrote: “I]f Trump succeeds in forcing through mass deportations, combined with Elon hacking away at the government, firing people and reducing the deficit—there will be an initial severe overreaction in the economy…. Markets will tumble. But when the storm passes and everyone realizes we are on sounder footing, there will be a rapid recovery to a healthier, sustainable economy. History could be made in the coming two years.”

Musk commented: “Sounds about right[.]”

This exchange echoes the prescription of Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, whose theories had done much to create the Great Crash of 1929, for restoring a healthy economy. “Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate,” he told President Herbert Hoover. “It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living

will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people.”

Mellon, at least, was reacting to an economic crisis thrust upon an administration. Musk is seeking to create one.

Today the Commerce Department reported that from July through September, the nation’s economy grew at a solid 2.8%. Consumer spending is up, as is investment in business. The country added 254,000 jobs in September, and inflation has fallen back almost to the Federal Reserve’s target of 2%.

It is extraordinarily rare for a country to be able to reduce inflation without creating a recession, but the Biden administration has managed to do so, producing what economists call a “soft landing,” rather like catching an egg on a plate. As Bryan Mena of CNN wrote today: “The US economy seems to have pulled off a remarkable and historic achievement.”

Both President Joe Biden and Democratic presidential nominee Vice President Kamala Harris have called for reducing the deficit not by slashing the government, as Musk proposes, but by restoring taxes on the wealthy and corporations.

As part of the Republicans’ plan to take the country back to the era before the 1930s ushered in a government that regulated business and provided a basic social safety net, House speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) expects to get rid of the Affordable Care Act.

At a closed-door campaign event on Monday in Pennsylvania for a Republican House candidate, Johnson told supporters that Republicans will propose “massive reform” to the Affordable Care Act, also known as “Obamacare,” if they take control of both the House and the Senate in November. “Health-care reform’s going to be a big part of the agenda,” Johnson said. Their plan is to take a “blowtorch to the regulatory state,” which he says is “crushing the free market.” “Trump’s going to go big,” he said.” When an attendee asked, “No Obamacare?” he laughed and agreed: “No Obamacare…. The ACA is so deeply ingrained, we need massive reform to make this work, and we got a lot of ideas on how to do that.”

Ending a campaign with a promise to crash a booming economy and end the Affordable Care Act, which ended insurance companies’ ability to reject people with preexisting conditions, is an unusual strategy.

A post from Trump last night and another this morning suggest his internal polls are worrying him. Last night he claimed there was cheating in Pennsylvania’s York and Lancaster counties. Today he posted: “Pennsylvania is cheating, and getting caught, at large scale levels rarely seen before. REPORT CHEATING TO AUTHORITIES. Law Enforcement must act, NOW!”

Trump appears to be setting up the argument he used in 2020, that he can lose only if he has been cheated. But it is increasingly apparent that the get-out-the-vote, or GOTV, efforts of the Trump campaign have been weak. When Trump’s daughter-in-law Lara Trump and loyalist Michael Whatley became the co-chairs of the Republican National Committee in March 2024, they stopped the GOTV efforts underway and used the money instead for litigation. They outsourced GOTV efforts to super PACs, including Musk’s America PAC.

In Wired today, Jake Lahut reported that door-knockers for Musk’s PAC were driven around in the back of a U-Haul without seats and threatened with having to pay their own hotel bills if they didn’t meet high canvassing quotas. One of the canvassers told Lahut that they thought they were being hired to ask people who they would be voting for when they flew into Michigan, and was surprised to learn their actual role. The workers spoke to Lahut anonymously because they had signed a nondisclosure agreement (a practice the Biden administration has tried to stop).

Trump’s boast that he is responsible for the Supreme Court’s overturning of the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision recognizing the constitutional right to abortion is one of the reasons his support is soft. In addition to popular dislike of the idea that the state, rather than a woman and her doctor, should make decisions about her healthcare, the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision is now over two years old, and state examinations of maternal deaths are showing that women are dying from lack of reproductive healthcare.

Cassandra Jaramillo and Kavitha Surana of ProPublica reported today that at least two pregnant women have died in Texas when doctors delayed emergency care after a miscarriage until the fetal heartbeat stopped. The woman they highlighted today, Josseli Barnica, left behind a husband and a toddler.

At a rally this evening near Green Bay, Wisconsin, Trump said his team had advised him to stop talking about how he was going to protect women by ending crime and making sure they don’t have to be “thinking about abortion.” But Trump, who has boasted of sexual assault and been found liable for it, did not stop there. He went on to say that he had told his advisors, “I’m going to do it whether the women like it or not. I am going to protect them.”

The Trump campaign remains concerned about the damage caused by the extraordinarily racist, sexist, and violent Sunday night rally at Madison Square Garden. Today the campaign seized on a misstatement President Biden made when condemning the statement from the Madison Square Garden event that referred to Puerto Rico as a “floating island of garbage.” They tried to turn the tables to suggest that Biden was calling Trump supporters garbage, although the president has always been very careful to focus his condemnation on Trump alone.

In Wisconsin today, when he disembarked from his plane, Trump put on an orange reflective vest and had someone drive him around the tarmac in a garbage truck with TRUMP painted on the side. He complained about Biden to reporters from the cab of the truck but still refused to apologize for Sunday’s slur of Puerto Rico, saying he knew nothing about the comedian who appeared at his rally.

This, too, was an unusual strategy. Like his visit to McDonalds, where he wore an apron, the image of Trump in a sanitation truck was likely intended to show him as a man of the people. But his power has always rested not in his promise to be one of the people, but rather to lead them. The pictures of him in a bright orange vest and unusually dark makeup are quite different from his usual portrayal of himself.

Indeed, media captured a video of Trump’s stunt, and it did not convey strength. MSNBC’s Katie Phang watched him try to get into the truck and noted: “Trump stumbles, drags his right leg, almost falls over, and tries at least three times to open the door…. Some transparency with Trump’s medical records would be nice.”

The Las Vegas Sun today ran an editorial that detailed Trump’s increasingly obvious mental lapses and concluded that Trump is “crippled cognitively and showing clear signs of mental illness.” It noted that Trump now depends “on enablers who show a disturbing willingness to indulge his delusions, amplify his paranoia or steer his feeble mind toward their own goals.” It noted that if Trump cannot fulfill the duties of the presidency, they would fall to his running mate, J.D. Vance, who has suggested “he would subordinate constitutional principles for personal profit and power.”

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#political cartoon#Matt Wuerker#Politico#Heather Cox Richardson#Letters From an American#Las Vegas Sun#MAGA extremism#garbage truck stunt#women's health#reproductive rights#Musk#Affordable Care Act#Obamacare#project 2025#MAGA's plans for you

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

American wealth has grown remarkably over the last 25 years, with household net worth climbing from $47.5 trillion in 1997 to $139 trillion in 2021 (in 2021 dollars)—an increase from 256% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1997 to 424% over the same period.

Equally remarkably, households headed by people aged 55 and older have enjoyed almost all (97%) of this growth (see Figure 1), and 75% occurred in the wealthiest 10% of households aged 55 and older. Both the number of households and wealth per household among households aged 55 and older have increased faster than in the rest of the population. As a result, the U.S. can expect the largest flows of intergenerational wealth transfers over the next several decades in modern history, and a substantial share of that wealth—especially among the very wealthiest households—will be passed down within families in a way that maintains family dynasties and increases wealth inequality.

Taxing these flows of wealth judiciously could raise revenue while improving equity among taxpayers and boosting their economic mobility. But the estate tax, the traditional way to tax such transfers, has been eviscerated in recent years. It exempts so much income and contains so many loopholes that only 1 in every 1,300 estates pay the tax. Given the impending wealth transfers and the emaciated nature of the estate tax, wealth transfer taxes are of current policy interest. In recent policy proposals by seven think tanks to address the long-term fiscal imbalance, all seven proposed some reform of the taxation of wealth transfers.

Our new study provides both new methodology for studying transfer taxes and new results. No data set has information on both bequests (what a person leaves to another) and inheritances (what a person receives from another). We adapt by estimating bequests and inheritances via independent methods using the Survey of Consumer Finances. The methodology does not require that the two estimates be equal, but they turn out to be close both in their aggregate and distribution. We can examine wealth transfer taxes from the point of view of the donor or the recipient, though in this initial project, we analyze all options assuming that heirs bear the burden of the tax (following work by other scholars).

We examine several policies—including inheritance taxes and taxing unrealized capital gains at death. In this brief, however, we focus on reforming the estate tax. In 1972, 6.5% of decedents paid estate taxes, generating 0.4% of GDP in revenues. By 1997, only 2.1% of decedents paid estate taxes, equaling just 0.19% of GDP. And by 2021, the tax raised just $18 billion, or 0.08% of GDP, in revenue.

We show that, if the estate tax had remained in its 2001 form and been indexed for inflation, it would have raised an estimated seven times as much revenue in 2021, or $145 billion. The weakened estate tax cost the federal government significant revenue, especially given how substantially the ratio of bequeathable net worth to GDP grew over this period.

As policymakers look for ways to address large and persistent federal deficits, shoring up the estate tax should be under consideration. It could generate more federal revenue, boost taxpayer equity, and improve economic mobility.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

How the Neocons Subverted Russia’s Financial Stabilization in the Early 1990s

by Jeffrey Sachs

In 1989 I served as an advisor to the first post-communist government of Poland, and helped to devise a strategy of financial stabilization and economic transformation. My recommendations in 1989 called for large-scale Western financial support for Poland’s economy in order to prevent a runaway inflation, enable a convertible Polish currency at a stable exchange rate, and an opening of trade and investment with the countries of the European Community (now the European Union). These recommendations were heeded by the US Government, the G7, and the International Monetary Fund.

Based on my advice, a $1 billion Zloty stabilization fund was established that served as the backing of Poland’s newly convertible currency. Poland was granted a standstill on debt servicing on the Soviet-era debt, and then a partial cancellation of that debt. Poland was granted significant development assistance in the form of grants and loans by the official international community.

Poland’s subsequent economic and social performance speaks for itself. Despite Poland’s economy having experienced a decade of collapse in the 1980s, Poland began a period of rapid economic growth in the early 1990s. The currency remained stable and inflation low. In 1990, Poland’s GDP per capita (measured in purchasing-power terms) was 33% of neighboring Germany. By 2024, it had reached 68% of Germany’s GDP per capita, following decades of rapid economic growth.

On the basis of Poland’s economic success, I was contacted in 1990 by Mr. Grigory Yavlinsky, economic advisor to President Mikhail Gorbachev, to offer similar advice to the Soviet Union, and in particular to help mobilize financial support for the economic stabilization and transformation of the Soviet Union. One outcome of that work was a 1991 project undertaken at the Harvard Kennedy School with Professors Graham Allison, Stanley Fisher, and Robert Blackwill. We jointly proposed a “Grand Bargain” to the US, G7, and Soviet Union, in which we advocated large-scale financial support by the US and G7 countries for Gorbachev’s ongoing economic and political reforms. The report was published as Window of Opportunity: The Grand Bargain for Democracy in the Soviet Union (1 October 1991).

The proposal for large-scale Western support for the Soviet Union was flatly rejected by the Cold Warriors in the White House. Gorbachev came to the G7 Summit in London in July 1991 asking for financial assistance, but left empty-handed. Upon his return to Moscow, he was abducted in the coup attempt of August 1991. At that point, Boris Yeltsin, President of the Russian Federation, assumed effective leadership of the crisis-ridden Soviet Union. By December, under the weight of decisions by Russia and other Soviet republics, the Soviet Union was dissolved with the emergence of 15 newly independent nations.

In September 1991, I was contacted by Yegor Gaidar, economic advisor to Yeltsin, and soon to be acting Prime Minister of newly independent Russian Federation as of December 1991. He requested that I come to Moscow to discuss the economic crisis and ways to stabilize the Russian economy. At that stage, Russia was on the verge of hyperinflation, financial default to the West, the collapse of international trade with the other republics and with the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe, and intense shortages of food in Russian cities resulting from the collapse of food deliveries from the farmlands and the pervasive black marketing of foodstuffs and other essential commodities.

I recommended that Russia reiterate the call for large-scale Western financial assistance, including an immediate standstill on debt servicing, longer-term debt relief, a currency stabilization fund for the ruble (as for the Zloty in Poland), large-scale grants of dollars and European currencies to support urgently needed food and medical imports and other essential commodity flows, and immediate financing by the IMF, World Bank, and other institutions to protect Russia’s social services (healthcare, education, and others).

In November 1991, Gaidar met with the G7 Deputies (the deputy finance ministers of the G7 countries) and requested a standstill on debt servicing. This request was flatly denied. To the contrary, Gaidar was told that unless Russia continued to service every last dollar as it came due, emergency food aid on the high seas heading to Russia would be immediately turned around and sent back to the home ports. I met with an ashen-faced Gaidar immediately after the G7 Deputies meeting.

In December 1991, I met with Yeltsin in the Kremlin to brief him on Russia’s financial crisis and on my continued hope and advocacy for emergency Western assistance, especially as Russia was now emerging as an independent, democratic nation after the end of the Soviet Union. He requested that I serve as an advisor to his economic team, with a focus on attempting to mobilize the needed large-scale financial support. I accepted that challenge and the advisory position on a strictly unpaid basis.

Upon returning from Moscow, I went to Washington to reiterate my call for a debt standstill, a currency stabilization fund, and emergency financial support. In my meeting with Mr. Richard Erb, Deputy Managing Director of the IMF in charge of overall relations with Russia, I learned that the US did not support this kind of financial package. I once again pleaded the economic and financial case, and was determined to change US policy. It had been my experience in other advisory contexts that it might require several months to sway Washington on its policy approach.

Indeed, during 1991-94 I would advocate non-stop but without success for large-scale Western support for Russia’s crisis-ridden economy, and support for the other 14 newly independent states of the former Soviet Union. I made these appeals in countless speeches, meetings, conferences, op-eds, and academic articles. Mine was a lonely voice in the US in calling for such support. I had learned from economic history — most importantly the crucial writings of John Maynard Keynes (especially Economic Consequences of the Peace, 1919) — and from my own advisory experiences in Latin America and Eastern Europe, that external financial support for Russia could well be the make or break of Russia’s urgently needed stabilization effort.

It is worth quoting at length here from my article in the Washington Post in November 1991 to present the gist of my argument at the time:

This is the third time in this century in which the West must address the vanquished. When the German and Hapsburg Empires collapsed after World War I, the result was financial chaos and social dislocation. Keynes predicted in 1919 that this utter collapse in Germany and Austria, combined with a lack of vision from the victors, would conspire to produce a furious backlash towards military dictatorship in Central Europe. Even as brilliant a finance minister as Joseph Schumpeter in Austria could not stanch the torrent towards hyperinflation and hyper-nationalism, and the United States descended into the isolationism of the 1920s under the "leadership" of Warren G. Harding and Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge. After World War II, the victors were smarter. Harry Truman called for U.S. financial support to Germany and Japan, as well as the rest of Western Europe. The sums involved in the Marshall Plan, equal to a few percent of the recipient countries' GNPs, was not enough to actually rebuild Europe. It was, though, a political lifeline to the visionary builders of democratic capitalism in postwar Europe. Now the Cold War and the collapse of communism have left Russia as prostrate, frightened and unstable as was Germany after World War I and World War II. Inside Russia, Western aid would have the galvanizing psychological and political effect that the Marshall Plan had for Western Europe. Russia's psyche has been tormented by 1,000 years of brutal invasions, stretching from Genghis Khan to Napoleon and Hitler. Churchill judged that the Marshall Plan was history's "most unsordid act," and his view was shared by millions of Europeans for whom the aid was the first glimpse of hope in a collapsed world. In a collapsed Soviet Union, we have a remarkable opportunity to raise the hopes of the Russian people through an act of international understanding. The West can now inspire the Russian people with another unsordid act.

This advice went unheeded, but that did not deter me from continuing my advocacy. In early 1992, I was invited to make the case on the PBS news show The McNeil-Lehrer Report. I was on air with acting Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger. After the show, he asked me to ride with him from the PBS studio in Arlington, Virginia back to Washington, D.C. Our conversation was the following. “Jeffrey, please let me explain to you that your request for large-scale aid is not going to happen. Even assuming that I agree with your arguments — and Poland’s finance minister [Leszek Balcerowicz] made the same points to me just last week — it’s not going to happen. Do you want to know why? Do you know what this year is?” “1992,” I answered. “Do you know that this means?” “An election year?” I replied. “Yes, this is an election year. It’s not going to happen.”

Russia’s economic crisis worsened rapidly in 1992. Gaidar lifted price controls at the start of 1992, not as some purported miracle cure but because the Soviet-era official fixed prices were irrelevant under the pressures of the black markets, the repressed inflation (that is, rapid inflation in the black-market prices and therefore the rising the gap with the official prices), the complete breakdown of the Soviet-era planning mechanism, and the massive corruption engendered by the few goods still being exchanged at the official prices far below the black-market prices.

Russia urgently needed a stabilization plan of the kind that Poland had undertaken, but such a plan was out of reach financially (because of the lack of external support) and politically (because the lack of external support also meant the lack of any internal consensus on what to do). The crisis was compounded by the collapse of trade among the newly independent post-Soviet nations and the collapse of trade between the former Soviet Union and its former satellite nations in Central and Eastern Europe, which were now receiving Western aid and were reorienting trade towards Western Europe and away from the former Soviet Union.

During 1992 I continued without any success to try to mobilize the large-scale Western financing that I believed to be ever-more urgent. I pinned my hopes on the newly elected Presidency of Bill Clinton. These hopes too were quickly dashed. Clinton’s key advisor on Russia, Johns Hopkins Professor Michael Mandelbaum, told me privately in November 1992 that the incoming Clinton team had rejected the concept of large-scale assistance for Russia. Mandelbaum soon announced publicly that he would not serve in the new administration. I met with Clinton’s new Russia advisor, Strobe Talbott, but discovered that he was largely unaware of the pressing economic realities. He asked me to send him some materials about hyperinflations, which I duly did.

At the end of 1992, after one year of trying to help Russia, I told Gaidar that I would step aside as my recommendations were not heeded in Washington or the European capitals. Yet around Christmas Day I received a phone call from Russia’s incoming financing minister, Mr. Boris Fyodorov. He asked me to meet him in Washington in the very first days of 1993. We met at the World Bank. Fyodorov, a gentleman and highly intelligent expert who tragically died young a few years later, implored me to remain as an advisor to him during 1993. I agreed to do so, and spent one more year attempting to help Russia implement a stabilization plan. I resigned in December 1993, and publicly announced my departure as advisor in the first days of 1994.

My continued advocacy in Washington once again fell on deaf ears in the first year of the Clinton Administration, and my own forebodings became greater. I repeatedly invoked the warnings of history in my public speaking and writing, as in this piece in the New Republic in January 1994, soon after I had stepped aside from the advisory role.

Above all, Clinton should not console himself with the thought that nothing too serious can happen in Russia. Many Western policymakers have confidently predicted that if the reformers leave now, they will be back in a year, after the Communists once again prove themselves unable to govern. This might happen, but chances are it will not. History has probably given the Clinton administration one chance for bringing Russia back from the brink; and it reveals an alarmingly simple pattern. The moderate Girondists did not follow Robespierre back into power. With rampant inflation, social disarray and falling living standards, revolutionary France opted for Napoleon instead. In revolutionary Russia, Aleksandr Kerensky did not return to power after Lenin's policies and civil war had led to hyperinflation. The disarray of the early 1920s opened the way for Stalin's rise to power. Nor was Bruning'sgovernment given another chance in Germany once Hitler came to power in 1933.

It is worth clarifying that my advisory role in Russia was limited to macroeconomic stabilization and international financing. I was not involved in Russia’s privatization program which took shape during 1993-4, nor in the various measures and programs (such as the notorious “shares-for-loans” scheme in 1996) that gave rise to the new Russian oligarchs. On the contrary, I opposed the various kinds of measures that Russia was undertaking, believing them to be rife with unfairness and corruption. I said as much in both the public and in private to Clinton officials, but they were not listening to me on that account either. Colleagues of mine at Harvard were involved in the privatization work, but they assiduously kept me far away from their work. Two were later charged by the US government with insider dealing in activities in Russia which I had absolutely no foreknowledge or involvement of any kind. My only role in that matter was to dismiss them from the Harvard Institute for International Development for violating the internal HIID rules against conflicts of interest in countries that HIID advised.

The failure of the West to provide large-scale and timely financial support to Russia and the other newly independent nations of the former Soviet Union definitely exacerbated the serious economic and financial crisis that faced those countries in the early 1990s. Inflation remained very high for several years. Trade and hence economic recovery were seriously impeded. Corruption flourished under the policies of parceling out valuable state assets to private hands.

All of these dislocations gravely weakened the public trust in the new governments of the region and the West. This collapse in social trust brought to my mind at the time the adage of Keynes in 1919, following the disaster Versailles settlement and the hyperinflations that followed: “There is no subtler, no surer means of over- turning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and it does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.”

During the tumultuous decade of the 1990s, Russia’s social services fell into decline. When this decline was coupled with the greatly increased stresses on society, the result was a sharp rise in Russia’s alcohol-related deaths. Whereas in Poland, the economic reforms were accompanied by a rise in life expectancy and public health, the very opposite occurred in crisis-riven Russia.

Even with all of these economic debacles, and with Russia’s default in 1998, the grave economic crisis and lack of Western support were not the definitive breaking points of US-Russian relations. In 1999, when Vladimir Putin became Prime Minister and in 2000 when he became President, Putin sought friendly and mutually supportive international relations between Russia and the West. Many European leaders, for example, Italy’s Romano Prodi, have spoken extensively about Putin’s goodwill and positive intentions towards strong Russia-EU relations in the first years of his presidency.

It was in military affairs rather than in economics that the Russian – Western relations ended up falling apart in the 2000s. As with finance, the West was militarily dominant in the 1990s, and certainly had the means to promote strong and positive relations with Russia. Yet the US was far more interested in Russia’s subservience to NATO that it was in stable relations with Russia.

At the time of German reunification, both the US and Germany repeatedly promised Gorbachev and then Yeltsin that the West would not take advantage of German reunification and the end of the Warsaw Pact by expanding the NATO military alliance eastward. Both Gorbachev and Yeltsin reiterated the importance of this US-NATO pledge. Yet within just a few years, Clinton completely reneged on the Western commitment, and began the process of NATO enlargement. Leading US diplomats, led by the great statesman-scholar George Kennan, warned at the time that the NATO enlargement would lead to disaster: “The view, bluntly stated, is that expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold-war era.” So, it has proved.

Here is not the place to revisit all of the foreign policy disasters that have resulted from US arrogance towards Russia, but it suffices here to mention a brief and partial chronology of key events. In 1999, NATO bombed Belgrade for 78 days with the goal of breaking Serbia apart and giving rise to an independent Kosovo, now home to a major NATO base in the Balkans. In 2002, the US unilaterally withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty over Russia’s strenuous objections. In 2003, the US and NATO allies repudiated the UN Security Council by going to war in Iraq on false pretenses. In 2004, the US continued with NATO enlargement, this time to the Baltic States and countries in the Black Sea region (Bulgaria and Romania) and the Balkans. In 2008, over Russia’s urgent and strenuous objections, the US pledged to expand NATO to Georgia and Ukraine.

In 2011, the US tasked the CIA to overthrow Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, an ally of Russia. In 2011, NATO bombed Libya in order to overthrow Moammar Qaddafi. In 2014, the US conspired with Ukrainian nationalist forces to overthrow Ukraine’s President Viktor Yanukovych. In 2015, the US began to place Aegis anti-ballistic missiles in Eastern Europe(Romania), a short distance from Russia. In 2016-2020, the US supported Ukraine in undermining the Minsk II agreement, despite its unanimous backing by the UN Security Council. In 2021, the new Biden Administration refused to negotiate with Russia over the question of NATO enlargement to Ukraine. In April 2022, the US called on Ukraine to withdraw from peace negotiations with Russia.

Looking back on the events around 1991-93, and to the events that followed, it is clear that the US was determined to say no to Russia’s aspirations for peaceful and mutually respectful integration of Russia and the West. The end of the Soviet period and the beginning of the Yeltsin Presidency occasioned the rise of the neoconservatives (neocons) to power in the United States. The neocons did not and do not want a mutually respectful relationship with Russia. They sought and until today seek a unipolar world led by a hegemonic US, in which Russia and other nations will be subservient.

In this US-led world order, the neocons envisioned that the US and the US alone will determine the utilization of the dollar-based banking system, the placement of overseas US military bases, the extent of NATO membership, and the deployment of US missile systems, without any veto or say by other countries, certainly including Russia. That arrogant foreign policy has led to several wars and to a widening rupture of relations between the US-led bloc of nations and the rest of the world. As an advisor to Russia during two years, late-1991 to late-93, I experienced first-hand the early days of neoconservatism applied to Russia, though it would take many years of events afterwards to recognize the full extent of the new and dangerous turn in US foreign policy that began in the early 1990s.

#AES#soviet union#eastern bloc#cold war#us imperialism#russia#nato#bill clinton#ukraine#history#jeffrey sachs

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Michigan Medicis of Donald Trump’s America

Left, clockwise from top left Blackwater founder Erik Prince; U.S. Sec of Education Betsy DeVos (Prince); philanthropist Elsa and Prince Corporation founder Edgar Prince. Right, philanthropist Hellen and Amway co-founder Richard DeVos; standing, businessman Dick DeVos.

If you ever wondered where the weird Republican ideas came from or how did we get here, well, here's a piece of the puzzle. Buckle up, it's a long read. Link to full article above. I pulled out quotes on topics below.

"In the solar system of elite Republican contributors, Richard DeVos Sr., who died Thursday at age 92—one of the two founders of Amway, the direct-sale colossus—occupied an exalted place, and his offspring did too. Since the 1970s, members of the DeVos family had given as much as $200 million to the G.O.P. and been tireless promoters of the modern conservative movement—its ideas, its policies, and its crusades combining free-market economics, a push for privatization of many government functions, and Christian social values. While other far-right mega-donors may have become better known over the years (the Coorses and the Kochs, Sheldon Adelson and the Mercers), Michigan’s DeVos dynasty stands apart—for the duration, range, and depth of its influence."

Conservative think tanks, advocacy organizations, and colleges

Grand Valley State University; Calvin College, attended by several generations of DeVoses, including Rich’s daughter-in-law Betsy DeVos, Northwood University, her husband Dick’s alma mater. Hillsdale, the libertarian-plus-Christian liberal-arts college in southern Michigan.

Other recipients of DeVos largesse: the Heritage Foundation, the Institute for Justice, and the American Enterprise Institute

"The DeVoses’ preference for “values-oriented” candidates reflect the teachings of the Christian Reformed Church. A small breakaway denomination of its Dutch forerunner, it has some 300,000 adherents in North America, many living in the same western-Michigan towns where their immigrant ancestors settled in the 1840s to pursue a faith.."

SCHOOL REFORM: Who can forget Betsy DeVos’s campaign to undo the state’s public-education system and replace it with for-profit and charter schools that, as she had put it two decades earlier, shared her mission of “defending the Judeo-Christian values"?

“[Among] her big ‘accomplishments,’” says Diane Ravitch, the N.Y.U. professor and respected education historian, “have been reversing civil-rights enforcement for kids with disabilities, putting administrators from for-profit colleges in charge of monitoring for-profit colleges . . . stabbing in the back young people with heavy debt for their college education, and being a constant critic of public schools.” One saving grace, Ravitch contends, is that DeVos has gotten very few of her budget proposals through Congress.

LABOR UNIONS: Another target was labor unions. Amway and the Prince Corporation had no use for them. Now the family waged a public fight. After Dick DeVos was routed when he ran for governor of Michigan in 2006, he blamed his defeat, in part, on Michigan’s unions and began to push for a right-to-work law (weakening the unions’ economic power and political clout, a pillar of the state’s Democratic Party). In 2012, the bill got through, and Michigan—headquarters to the United Automobile Workers, no less—became yet another of the country’s right-to-work states.

FAMILY: "Betsy and Erik’s father, Edgar Prince, was a Chrysler-Plymouth salesman and then machine engineer who started a die-cast business and also had a tinkerer’s gift for inventions. One, the lighted vanity mirror on the flip-up sun visor (introduced in 1972), helped Prince become one of the wealthiest men in Michigan." (wow) "As he got richer, the elder Prince rewarded his hometown handsomely; Prince money has done much to preserve downtown Holland, which remains a 1950s time capsule of Candy Land façades."

The C.R.C.’s greatest figure, Abraham Kuyper, a Dutch theologian and prime minister who died almost a century ago, had declared, in words the faithful know by heart: “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, Mine!”

The Princes and DeVoses—with neighboring homes in Holland—had effected a merger thanks to the 1979 marriage of their firstborn, Betsy Prince and Dick DeVos, then in their 20s. “Bible-reading jet-setter” was the description in a Detroit Free Press profile of Betsy.

Betsy and Dick own a 22,000-square-foot mansion on Lake Macatawa.

ERIK PRINCE was devoted to his father, who doted on him. He played four sports at Holland Christian and was the proudly straitlaced kid who, without being asked, put away the soccer balls after practice. Prince enrolled in the U.S. Naval Academy in 1987 but was shocked by the frat-house atmosphere—too much for a junior culture warrior who’d been an intern at the Family Research Council. After three semesters, he transferred to Michigan’s Hillsdale College.

Today Hillsdale, under its president, Larry P. Arnn (former head of the Claremont Institute, a citadel of far-right ideology), is known as a feeder school for the Trump administration, including Betsy DeVos’s chief of staff, Josh Venable. In May, the week Vice President Pence gave the commencement address there, Politico called it “the college that wants to take over Washington”—citing many alums who are now D.C. power players.

In 1989, Erik had been invited to a “youth” inaugural ball for Bush—and there had met Joan Keating, the woman who would become his first wife. Prince even worked as a Bush White House intern. “I saw a lot of things I didn’t agree with,” he later said. “Homosexual groups being invited in, the budget agreement, the Clean Air Act, those kind of bills. I think the administration has been indifferent to a lot of conservative concerns.” He left that job for another, in the office of California congressman Dana Rohrabacher, who has often been called Vladimir Putin’s top Capitol Hill asset, so valued, the Times has reported, that he was given a Kremlin code name.

Prince spent four years with the SEALs in the early 90s but moved on after his wife was diagnosed with cancer and his father, aged 63, died of a heart attack. The elder Prince left behind a business with 4,500 employees. The family sold it for $1.3 billion, and Erik, at 25, now had a sizable inheritance.

One of Prince’s instructors in the SEALs, Al Clark, was also looking to set up a security-and-defense training company. Prince had money to invest. Out of this came Blackwater, which began as an instruction facility for law enforcement, the military, and special-ops squads in Moyock, North Carolina.

The article goes into detail about Blackwater and it is mind-blowing. Their involvement post 9/11, Russian arms dealings, US government contracts,

"The source says he resigned after he discovered that Prince had approved plans to illegally weaponize aircraft and “actively train former Chinese Red Army personnel that are now being deployed into Pakistan, Thailand, Myanmar, and the Uighur region in China”—actions he perceived as supporting foreign interests above America’s. (Other Prince associates reportedly resigned for similar reasons.) Prince firmly denied the allegations."

#erik prince#betsy devos#michigan#religion#education#labor unions#pat buchanan#donald trump#republicans#conservative think tanks#heritage foundation#project 2025#christian reformed church#vote blue#vote democrat

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

DOGE Cancels $52M Payment to the WEF. House Passes Trump-Backed Budget Proposal. US Invasion Of Canada? Kiev agrees to Trump’s minerals deal. CHEMTRAILS are out of control and they're getting worse

Lioness of Judah Ministry

Feb 26, 2025

DOGE Cancels $52 Million Payment to he World Economic Forum

JUST IN: House Passes Trump-Backed Budget Proposal 217-215 – Massie Votes “No”

The House of Representatives passed the Republican spending bill in a 217-215 vote on Tuesday evening.

Rep. Massie was the only Republican to vote “no” on Trump’s “big beautiful bill” which boasts $2 trillion in cuts. The budget package sets the stage for tax cuts, immigration reform, domestic energy expansion and Pentagon funding…Speaker Johnson was confident ahead of Tuesday night’s vote – ‘There’s no Plan B’ Johnson said. Speaker Pro Tem Michael Simpson presided over the House on Tuesday evening as lawmakers voted on the budget package.

BREAKING: Kash Patel Launches Investigation Into James Comey’s Secret ‘Honeypot’ Operation Involving Two Undercover Agents Who Targeted Trump’s 2016 Campaign

FBI Director Kash Patel has launched an investigation into former Director James Comey’s secret “honeypot” operation involving 2 female undercover agents who targeted President Trump’s 2016 campaign, according to The Washington Times.

Last October it was revealed that according to an FBI whistleblower, former Director James Comey inserted two female agents inside the Trump campaign in 2016. The Washington Times reported that the female agents were directed to act as “honeypots” and travel with Trump and his staff. This was an “off-the-books” operation and was separate from Comey and Obama’s Crossfire Hurricane operation (launched in July 2016) that targeted Trump based on false Russian collusion lies.

EXPLAINED: Judge’s Ruling Against Trump’s Refugee Resettlement Suspension Opens Constitutional Quagmire

A U.S. District Court judge in Seattle, Washington, temporarily blocked President Donald J. Trump’s executive order suspending refugee resettlement in the United States on Tuesday.

The move is part of the latest lawfare efforts by far-left and progressive non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to hamper the Trump administration’s efforts to undo former President Joe Biden’s mass immigration policies. However, the preliminary injunction, issued by District Court Judge Jamal Whitehead, could be the subject of an emergency appeal by the Trump Department of Justice (DOJ) to the U.S. Supreme Court as it opens concerning constitutional questions.

They're Fired: 100 Intelligence Officials In Sick Chat Group 'Terminated And Their Security Clearances Revoked'

An egregious violation of trust.

Update (2210ET): DNI Tulsi Gabbard announced on Tuesday that 100 individuals in the intelligence community have been identified as having "contributed to and participated in" the sick internal chat group who will be fired and have their security clearances revoked. "There are over 100 people from across the intelligence community that contributed to and participated in this - what is really just an egregious violation of trust. What to speak of, like, basic rules and standards around professionalism. I put out a directive today that they all will be terminated and their security clearances will be revoked," Gabbard told Fox News' Jesse Watters.

Rep. Ilhan Omar Claims AG Pam Bondi Is “Protecting” Someone Since Epstein Files Have Yet to Be Released

Representative Ilhan Omar (D-Minn) took to X on Tuesday and claimed Attorney General Pam Bondi is protecting someone since the Jeffrey Epstein Files have yet to be released.

In a post on X, Omar wrote, “The AG still not releasing the EPSTEIN FILES is weird.” She added it “raises the question of who she might be protecting.” Her comments come a day after Rep. Anna Paulina Luna called out AG Bondi over the slow roll of the Epstein Files release. Luna stated, “AG Pam Bondi, We saw over the weekend you are reviewing all files from JFK to Epstein! We are ALL anticipating their release! When will they be declassified and available to the public?”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heather Cox Richardson 10.30.24

On Friday, October 25, at a town hall held on his social media platform X, Elon Musk told the audience that if Trump wins, he expects to work in a Cabinet-level position to cut the federal government.

He told people to expect “temporary hardship” but that cuts would “ensure long-term prosperity.” At the Trump rally at New York City’s Madison Square Garden on Sunday, Musk said he plans to cut $2 trillion from the government. Economists point out that current discretionary spending in the budget is $1.7 trillion, meaning his promise would eliminate virtually all discretionary spending, which includes transportation, education, housing, and environmental programs.

Economists agree that Trump’s plans to place a high tariff wall around the U.S., replacing income taxes on high earners with tariffs paid for by middle-class Americans, and to deport as many as 20 million immigrants would crash the booming economy. Now Trump’s financial backer Musk is factoring in the loss of entire sectors of the government to the economy under Trump.

Trump has promised to appoint Musk to be the government’s “chief efficiency officer.” “Everyone’s going to have to take a haircut.… We can’t be a wastrel.… We need to live honestly,” Musk said on Friday. Rob Wile and Lora Kolodny of CNBC point out that Musk’s SpaceX aerospace venture has received $19 billion from the U.S. government since 2008.

An X user wrote: “I]f Trump succeeds in forcing through mass deportations, combined with Elon hacking away at the government, firing people and reducing the deficit—there will be an initial severe overreaction in the economy…. Markets will tumble. But when the storm passes and everyone realizes we are on sounder footing, there will be a rapid recovery to a healthier, sustainable economy. History could be made in the coming two years.”

Musk commented: “Sounds about right[.]”

This exchange echoes the prescription of Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, whose theories had done much to create the Great Crash of 1929, for restoring a healthy economy. “Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate,” he told President Herbert Hoover. “It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people.”

Mellon, at least, was reacting to an economic crisis thrust upon an administration. Musk is seeking to create one.

Today the Commerce Department reported that from July through September, the nation’s economy grew at a solid 2.8%. Consumer spending is up, as is investment in business. The country added 254,000 jobs in September, and inflation has fallen back almost to the Federal Reserve’s target of 2%.

It is extraordinarily rare for a country to be able to reduce inflation without creating a recession, but the Biden administration has managed to do so, producing what economists call a “soft landing,” rather like catching an egg on a plate. As Bryan Mena of CNN wrote today: “The US economy seems to have pulled off a remarkable and historic achievement.”

Both President Joe Biden and Democratic presidential nominee Vice President Kamala Harris have called for reducing the deficit not by slashing the government, as Musk proposes, but by restoring taxes on the wealthy and corporations.

As part of the Republicans’ plan to take the country back to the era before the 1930s ushered in a government that regulated business and provided a basic social safety net, House speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) expects to get rid of the Affordable Care Act.

At a closed-door campaign event on Monday in Pennsylvania for a Republican House candidate, Johnson told supporters that Republicans will propose “massive reform” to the Affordable Care Act, also known as “Obamacare,” if they take control of both the House and the Senate in November. “Health-care reform’s going to be a big part of the agenda,” Johnson said. Their plan is to take a “blowtorch to the regulatory state,” which he says is “crushing the free market.” “Trump’s going to go big,” he said.” When an attendee asked, “No Obamacare?” he laughed and agreed: “No Obamacare…. The ACA is so deeply ingrained, we need massive reform to make this work, and we got a lot of ideas on how to do that.”

Ending a campaign with a promise to crash a booming economy and end the Affordable Care Act, which ended insurance companies’ ability to reject people with preexisting conditions, is an unusual strategy.

A post from Trump last night and another this morning suggest his internal polls are worrying him. Last night he claimed there was cheating in Pennsylvania’s York and Lancaster counties. Today he posted: “Pennsylvania is cheating, and getting caught, at large scale levels rarely seen before. REPORT CHEATING TO AUTHORITIES. Law Enforcement must act, NOW!”

Trump appears to be setting up the argument he used in 2020, that he can lose only if he has been cheated. But it is increasingly apparent that the get-out-the-vote, or GOTV, efforts of the Trump campaign have been weak. When Trump’s daughter-in-law Lara Trump and loyalist Michael Whatley became the co-chairs of the Republican National Committee in March 2024, they stopped the GOTV efforts underway and used the money instead for litigation. They outsourced GOTV efforts to super PACs, including Musk’s America PAC.

In Wired today, Jake Lahut reported that door-knockers for Musk’s PAC were driven around in the back of a U-Haul without seats and threatened with having to pay their own hotel bills if they didn’t meet high canvassing quotas. One of the canvassers told Lahut that they thought they were being hired to ask people who they would be voting for when they flew into Michigan, and was surprised to learn their actual role. The workers spoke to Lahut anonymously because they had signed a nondisclosure agreement (a practice the Biden administration has tried to stop).

Trump’s boast that he is responsible for the Supreme Court’s overturning of the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision recognizing the constitutional right to abortion is one of the reasons his support is soft. In addition to popular dislike of the idea that the state, rather than a woman and her doctor, should make decisions about her healthcare, the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision is now over two years old, and state examinations of maternal deaths are showing that women are dying from lack of reproductive healthcare.

Cassandra Jaramillo and Kavitha Surana of ProPublica reported today that at least two pregnant women have died in Texas when doctors delayed emergency care after a miscarriage until the fetal heartbeat stopped. The woman they highlighted today, Josseli Barnica, left behind a husband and a toddler.

At a rally this evening near Green Bay, Wisconsin, Trump said his team had advised him to stop talking about how he was going to protect women by ending crime and making sure they don’t have to be “thinking about abortion.” But Trump, who has boasted of sexual assault and been found liable for it, did not stop there. He went on to say that he had told his advisors, “I’m going to do it whether the women like it or not. I am going to protect them.”

The Trump campaign remains concerned about the damage caused by the extraordinarily racist, sexist, and violent Sunday night rally at Madison Square Garden. Today the campaign seized on a misstatement President Biden made when condemning the statement from the Madison Square Garden event that referred to Puerto Rico as a “floating island of garbage.” They tried to turn the tables to suggest that Biden was calling Trump supporters garbage, although the president has always been very careful to focus his condemnation on Trump alone.

In Wisconsin today, when he disembarked from his plane, Trump put on an orange reflective vest and had someone drive him around the tarmac in a garbage truck with TRUMP painted on the side. He complained about Biden to reporters from the cab of the truck but still refused to apologize for Sunday’s slur of Puerto Rico, saying he knew nothing about the comedian who appeared at his rally.

This, too, was an unusual strategy. Like his visit to McDonalds, where he wore an apron, the image of Trump in a sanitation truck was likely intended to show him as a man of the people. But his power has always rested not in his promise to be one of the people, but rather to lead them. The pictures of him in a bright orange vest and unusually dark makeup are quite different from his usual portrayal of himself.

Indeed, media captured a video of Trump’s stunt, and it did not convey strength. MSNBC’s Katie Phang watched him try to get into the truck and noted: “Trump stumbles, drags his right leg, almost falls over, and tries at least three times to open the door…. Some transparency with Trump’s medical records would be nice.”

The Las Vegas Sun today ran an editorial that detailed Trump’s increasingly obvious mental lapses and concluded that Trump is “crippled cognitively and showing clear signs of mental illness.” It noted that Trump now depends “on enablers who show a disturbing willingness to indulge his delusions, amplify his paranoia or steer his feeble mind toward their own goals.” It noted that if Trump cannot fulfill the duties of the presidency, they would fall to his running mate, J.D. Vance, who has suggested “he would subordinate constitutional principles for personal profit and power.”

—

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 1968 Prague Spring: Separating Fact from Fiction

Much of the below is translated or adapted from an article written by the Russian historian and political scientist Nikolay Platoshkin. The article can be found here. You can find an identical blog post with hyperlinks to sources here.

Victors write history, and the historical narratives concerning the events of the Cold War are no different. The “Prague Spring” of 1968 is often shrouded in myths that serve the political interests of the hegemonic capitalist countries. The prevailing narrative typically presents the events as follows: economic and political reforms in Czechoslovakia, sparked by the election of the intrepid Alexander Dubček as First Secretary of the Communist Party in January 1968, were brutally suppressed by the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops on August 20-21. Naturally, the sympathies of the “free world,” particularly the United States, are portrayed as being aligned with the brave Czechoslovak reformers. However, the reality is more complex.

Genuine political and economic reforms in Czechoslovakia began long before the “Prague Spring,” influenced by developments in the Soviet Union during the early 1960s. As the Soviet Union under Khrushchev embarked on a period of de-Stalinization, it sparked a wave of reformist thinking across its satellite states. Under the leadership of Antonín Novotný, who had been President of Czechoslovakia and General Secretary of the Communist Party since 1953, the country initiated the rehabilitation of victims arrested during the Stalinist period. (The future leader of Czechoslovakia in the 1970s and 1980s, Gustáv Husák, was one of these, arrested in 1950 and released in 1963, a committed communist throughout.) Censorship was eased significantly, and Czechoslovak cinema, particularly the “New Wave” movement, gained recognition across Europe, with directors like Miloš Forman emerging internationally, as seen with his film Black Peter. A pivotal moment in this period was the adoption of a new economic policy in 1965, directly inspired by the Soviet Union’s Kosygin reforms. This policy aimed to decentralize economic planning, granting enterprises greater autonomy within a framework of business accounting.

The Soviet Union acted as the primary catalyst for reforms in Czechoslovakia, particularly after the new Soviet leadership under Leonid Brezhnev came to power in October 1964, which further accelerated reforms in Moscow and Prague. However, by late 1967, internal conflict within the Czechoslovak Communist Party intensified. Students from the Strahov dormitories in Prague launched a sizable protest over power outages, prompting Novotný to cease reforms and ban liberal journals and films. The widespread unpopularity of these moves led members of the party’s Central Committee to oust Novotný. This coalition of strange bedfellows included noted liberal reformers like Husák, Čestmír Císař, and Jozef Lenárt joining forces with conservatives like Vasil Biľak, Drahomír Kolder, and Jiří Hendrych. When Novotný sought a lifeline from Brezhnev in December 1967, Brezhnev refused, partly because he viewed Novotný as an ally of his Soviet rival, Alexei Kosygin.

During heated debates within the Czechoslovak Communist Party’s Central Committee, which began in October 1967, Novotný suggested Alexander Dubček as a compromise candidate for First Secretary, a proposal that Brezhnev accepted. Dubček, who had lived in the USSR from 1925 to 1938 (where he was a classmate of Brezhnev) and was seen as a reliable ally, was considered a weak political figure, making him acceptable to both liberal and conservative factions within the party. He was also of Slovak descent, which would appease Slovak nationalists who opposed the unitary state. On January 5, 1968, Dubček was narrowly elected First Secretary by just one vote. Brezhnev’s unexpected visit to Prague in December 1967 was interpreted by the U.S. as a reluctant intervention in the party’s internal struggles, given the lack of a clear alternative to Novotný. Far from the enterprising reformer portrayed in Western media, Dubček was initially meant to hold the party line, something that he promised to do, part of a pattern of deception and careerism.

In February 1968, the U.S. State Department agreed with the U.S. Embassy in Prague’s recommendation to refrain from showing goodwill toward Dubček’s regime, viewing it as an unstable coalition of right and left forces. The U.S. chose not to act despite holding significant leverage at the time, stemming from the U.S. Army’s seizure of Czechoslovakia’s gold reserves during the liberation of western Czechoslovakia in 1945. The gold had been taken by the Germans after their 1939 occupation. Despite repeated requests from the Czechoslovak government, the U.S. avoided returning the gold, citing various pretexts. In 1961, the U.S. agreed to return the gold in exchange for settling claims of American citizens affected by post-1948 nationalization in Czechoslovakia. Both sides initially agreed on a sum of around $10 million, but the U.S. later quadrupled the demand due to Washington’s displeasure over Czechoslovakia’s arms supplies to Vietnam. Additionally, the U.S. delayed granting Czechoslovakia most-favored-nation trade status, linking it to the unresolved gold issue. At the onset of the “Prague Spring,” U.S. policy was frosty toward Dubček.

On March 22, 1968, Antonín Novotný resigned as President, and General Ludvík Svoboda, a former commander of Czechoslovak forces on the Soviet-German front, succeeded him. The day before, Czechoslovak Ambassador to Washington, Karel Duda, told U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs, Walter J. Stoessel, that the new leadership would likely seek better relations with the U.S. He dismissed the possibility of foreign interference in Czechoslovakia’s internal affairs, which the Americans interpreted as a reference to Moscow, but warned that internal conflict could escalate if it led to violence. This affirmed the view that Dubček’s regime was meant to stabilize Czechoslovakia, at least for the time being, not usher in a wave of reforms that would destabilize the country.

On February 25, Major General Jan Šejna, a Novotný supporter who led the Defense Ministry’s party organization, defected to the U.S. with his young mistress. Czechoslovakia demanded his extradition, accusing him of corruption and plotting a military coup for Novotný, but the U.S. refused. Despite being deemed a criminal by the Dubček government and once considered a hardliner, Šejna became a key CIA informant on Czechoslovakia and received political asylum. Given the choice between sheltering an individual it once considered a “Stalinist” for a military advantage or diplomatic measures meant to thaw relations with a Cold War adversary, the U.S. government eagerly pursued the former option.

The U.S. Ambassador to Czechoslovakia, Jacob Beam, held a low opinion of the new Dubček regime, viewing any push for liberalization as secondary to ousting Novotný, after which the government would likely seek stability. Nonetheless, Beam believed that the unfolding events in Czechoslovakia aligned with U.S. interests. On April 26, he recommended to Under Secretary of State for European Affairs, Charles E. Bohlen, a more flexible stance on the issue of Czechoslovakia’s gold reserves as a diplomatic gesture toward the new Prague leadership. Beam suggested returning “Nazi gold” to Czechoslovakia in exchange for an initial payment to compensate individuals whose wealth was expropriated during communist nationalization, with additional payments to follow. He also proposed using most-favored-nation trade status as a potential incentive, which would mean low tariffs or high import quotas for Czechoslovakia. Beam believed these steps could enhance U.S. influence within the communist world. However, Beam’s modest proposal was not supported. The State Department agreed only to express approval of Czechoslovakia’s liberalization. Due to Czechoslovakia’s role as the third-largest arms supplier to North Vietnam, direct financial or economic aid from the U.S. was deemed impossible.

During this period, a significant debate unfolded in Washington between “hawks” and “doves” in the U.S. leadership. President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had decided not to seek re-election in October 1968, and Secretary of State Dean Rusk prioritized détente with the USSR. They believed this thaw in relations could help end the Vietnam War with Soviet assistance. Johnson even planned a potential visit to Moscow in October 1968, becoming the first U.S. President to do so. Johnson was concerned that excessive liberalization in Czechoslovakia might jeopardize the improving U.S.-Soviet relations.

In contrast, the “hawk” faction, led by Deputy Secretary of State for Political Affairs Walt Rostow, saw an opportunity to weaken the USSR globally by attempting to pull Czechoslovakia out of the Warsaw Pact. Rostow believed this could distract the Soviets from Vietnam and possibly allow the U.S. to end the war on more favorable terms. Rostow is remembered as one of the biggest cheerleaders for the Vietnam War, claiming that strategic bombing of North Vietnam alone would be sufficient to win the war. This was based on Rostow’s belief that there was no genuine support for communism in South Vietnam and that ending the war was as simple as destroying North Vietnam’s infrastructure.

On May 10, 1968, Rostow sent Rusk a memorandum titled “Soviet Threats to Czechoslovakia,” interpreting Warsaw Pact maneuvers in Poland as a sign of Soviet hesitation and urging Johnson to summon the Soviet Ambassador to demand an explanation. Rostow also proposed creating a special high-level NATO group to monitor the situation in Czechoslovakia and prepare a response plan. However, both Rusk and Johnson rejected Rostow’s alarmist stance.

The U.S. Embassy in West Germany shared a cautious view for different reasons. Unlike the 1956 Hungarian crisis, the Embassy noted in a telegram on May 10 that moving American troops closer to or across the Czech border to counter a Soviet attack was conceivable due to the shared border between Czechoslovakia and West Germany. However, the West German government, including the Social Democrats, strongly opposed any U.S. military action from West German territory. The West German Deputy Foreign Minister even urged the U.S. Ambassador to moderate anti-Czechoslovak propaganda from Radio Free Europe in Munich and RIAS in West Berlin, leading the U.S. Ambassador to West Germany, George McGhee, to consider joint actions with West Germany against Czechoslovakia unrealistic.

On May 11, Secretary of State Dean Rusk initiated a continuous exchange of opinions between NATO countries concerning the situation in Czechoslovakia. However, in a telegram to the U.S. mission to NATO, he recommended holding off on actions that might be perceived as NATO showing “unusual concern” about Czechoslovakia.

Despite this, the U.S. remained unwilling to address the pressing bilateral issues with Czechoslovakia. On May 28, Jiří Hájek, the new Czechoslovak Foreign Minister and a reformer, expressed frustration to the U.S. ambassador that bilateral relations had not improved since 1962 and had even regressed in some respects. Hájek reiterated demands for the return of Czechoslovakia’s gold reserves, pointing out that the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia had occurred with the West’s, including the U.S.’s, acquiescence. Ambassador Beam was unable to provide a concrete response but reported to the State Department that Prague was likely using the gold issue to bolster its authority within the communist bloc and to curb any growing pro-American sentiments within the country.

On June 13, the CIA provided a memorandum titled “Czechoslovakia: Dubcek’s Pause” to the top U.S. leadership. The memo assessed that the crisis in Czechoslovakia, both internal and external, had lost its immediacy, leading to a “pause.” The Soviet Union had been reassured by Dubček’s firm commitment to keeping the reform process under Communist Party control. In return, the Czechs were granted some autonomy in domestic matters by the USSR. The CIA noted that the Soviets were keen to avoid military intervention in Czechoslovakia, due to concerns that the country might leave the Warsaw Pact, given that Czechoslovakia had the largest army per capita within the Pact, totaling 230,000 soldiers.

Despite Moscow’s objections to the anti-Soviet rhetoric in the Czechoslovak media, the CIA reported that this rhetoric had “reached astonishing proportions” in recent weeks. The media blamed the USSR not only for the Stalinist repression of the early 1950s but also for the current economic difficulties in Czechoslovakia. However, it was precisely cheap raw materials from the USSR that were able to provide Czechoslovakia with high rates of economic growth and an improvement in the standard of living of the population. For all its embrace of market reforms, the Czechoslovak economy did not grow out of its moribund status, as goods produced in the country simply were not competitive enough. Inflation soon followed, leading to cuts to social services, which only led to greater public dissent.

The CIA concluded that due to the compromise between Prague and Moscow, “Moscow decided not to use force, at least for the time being.” Interestingly, the CIA noted that Dubček himself might benefit from this situation, as his perceived indecisiveness in implementing reforms could be attributed to Soviet pressure. U.S. intelligence, citing Czech sources, also reported growing disagreements within the Soviet leadership over Czechoslovakia. Leonid Brezhnev, who had placed Dubček in power, was under pressure as Dubček’s policies were increasingly seen as anti-Soviet. This situation could potentially be exploited by Brezhnev’s opponents within the Soviet leadership, including Kosygin.

U.S. intelligence, correctly assessing the situation, believed that Dubček was merely stalling by agreeing to Brezhnev’s terms and promising to maintain socialism in Czechoslovakia. They anticipated that at the upcoming Communist Party congress in September 1968, reformist views would be formally adopted as the party’s official program, revealing to the Soviets that they had been misled. The CIA also assessed that Dubček lacked firm convictions of his own and was influenced by the reformers Oldřich Černík and Zdeněk Mlynář, who were expected to play a crucial role after the congress. The CIA concluded that there was a significant likelihood of renewed tension between Prague and Moscow. Although Soviet leaders, or at least most of them, preferred to avoid sharp and costly military action, they might resort to threatening Czech borders if Dubček’s control appeared to be collapsing or if Czech policies became “counterrevolutionary” from Moscow’s perspective.

By this time, the CIA was heavily influenced by its primary “expert” on Czechoslovakia, General Šejna, who was pursuing his own agenda to discredit Dubček. On July 24, the CIA reported that the crisis in Czechoslovakia had subsided, according to Šejna, who believed that the Czechoslovaks would likely capitulate to Soviet demands and reverse the reforms. Šejna also suggested that such a rollback would not provoke significant public protests, as neither workers nor Slovaks were actively engaged in the liberalization process. The CIA noted that the “Prague Spring” was largely driven by intellectuals and parts of the party apparatus without improving the material conditions of the general population. Furthermore, anti-Soviet sentiment in the Czech press did not resonate with Slovakia. The CIA’s internal notes reflected concerns that Šejna might be underestimating the national factor, noting that military and police forces, being “conservative and pro-Soviet,” could quickly suppress any potential demonstrations against the rollback of reforms.

The CIA memo highlighted that the Soviets were facing substantial pressure from conservative forces within Czechoslovakia, as well as from the leaders of Poland and East Germany, who demanded more stringent control over the situation in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. Šejna believed that while the Soviets favored using political influence, they were prepared to use military force if necessary, which would likely involve a rapid advance of Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia. The CIA accurately assessed that Moscow was becoming aware that Dubček and the “liberals” were not fulfilling their promises to keep Czechoslovakia within the Soviet sphere of influence, specifically the Warsaw Pact.

By July 1968, the State Department was already considering raising the Czechoslovak issue at the United Nations, potentially as a protest against the slow withdrawal of Soviet troops following the end of the Warsaw Pact “Šumava” maneuvers on June 30. However, the U.S. was reluctant to take direct action at the U.N., preferring instead that the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, or potentially Romania and Yugoslavia, initiate the discussion.

On July 14-15, the leaders of the Soviet Union, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria met in Warsaw to discuss the events taking place in Czechoslovakia. On the heels of the publication of liberal manifesto “The Two Thousand Words,” the Warsaw Pact leaders feared that anti-communist forces were exploiting the liberalization to promote disorder. Although they stated their common desire not to interfere in Czechoslovak affairs, they shared anxieties that reactionary forces were preparing for counterrevolution:

The reactionary forces were given the opportunity, in public, to publish their political platform under the title “Two Thousand Words,” which contains an open call for a struggle against the communist party and against the constitutional system, as well as a call for strikes and chaos. This appeal is a serious threat to the party, the National Front, and the socialist state. It is an attempt to foment anarchy. The declaration is, in its essence, the organizational-political platform of counterrevolution.