#The Kingdom of Kongo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Kingdom of Kongo: History, Traditions, and Expansion

The Kingdom of Kongo holds a significant place in the history of Central Africa, its influence stretching across present-day northern Angola, western Democratic Republic of the Congo, Southern Gabon, and the Republic of the Congo. At its zenith, the kingdom encompassed a vast territory, spanning from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Kwango River in the east, and from the Congo River in the…

View On WordPress

#African History#African kingdom#central Africa#central africa history#medieval African Kingdom#medieval Kingdom#The Kingdom of Kongo

0 notes

Text

Exploring the Rich Linguistic Heritage of Kikongo and Kituba Languages in the Kongo Kingdom

Uncovering the Secrets of the Kikongo Language and People Located in the heart of Central Africa, the Kikongo language has a rich cultural heritage that has been passed down through the centuries. This ancient language spoken by the Bakongo people provides fascinating insight into the region’s history, traditions and way of life. In this article, we delve into the fascinating world of the…

View On WordPress

#African Languages#Bakongo people#Bantu languages#Cultural Heritage#inclusivity#Interpretation Services#Kikongo language#Kongo Kingdom#Language Preservation#LanguageXS

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

this isn’t always true, and differs wildly across history and geography, but most people have this understanding of mass conversion of a region into a different faith (usually Christianity or Islam) as just a straightforward veni, vidi, vici type of situation, but from i can tell the most common method was “local leaders convert as a means of ensuring peace and trade with powerful rival states, then the these same domestic authorities are the ones who pass laws enforcing religious conversion upon their subjects”, which you can still criticize of course, but is a bit distinct from the more simplistic view

#This is most true for Northern Europe with Christianity and West Africa with Islam#modern colonialism was different#but also true of the Kongo Kingdom at least#anyways not trying to defend these religions or the political conquests that used them to expand their power#I’m just hung up on the complexities that are often ignored#also my understanding is the Fulani led jihad was mostly targeted towards rival Muslim sects?#but i could be wrong here

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion

Abstract

Historical scholarship on Afro-Cuban religions has long recognized that one of its salient characteristics is the union of African (Yoruba) gods with Catholic Saints. But in so doing, it has usually considered the Cuban Catholic church as the source of the saints and the syncretism to be the result of the worshippers hiding worship of the gods behind the saints. This article argues that the source of the saints was more likely to be from Catholics from the Kingdom of Kongo which had been Catholic for 300 years and had made its own form of Christianity in the interim.

Acknowledgements

Research funding for this project was supplied by Boston University Faculty Research Fund and the Hutchins Center of Harvard University. Earlier versions were presented at the Hutchins Center, and the keynote address at ‘Kongo Across the Waters’ in Gainesville, FL. Thanks to Linda Heywood, Matthew Childs, Manuel Barcia, Jane Landers, Carmen Barcia, Jorge Felipe Gonzalez, Thiago Sapede, Marial Iglesias Utset, Aisha Fisher, Dell Hamilton, Grete Viddal and Kyrah Daniels for readings, comments, questions and source material.

[1] Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983), pp. 17–8; see also Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and African America (New York: Prestel, 1993). For Cuba in particular, see David H. Brown, Santería Enthroned: Art, Ritual and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003), p. 34 (with ample references to earlier visions).

[2] Georges Balandier, Daily Life in the Kingdom of the Kongo (New York: Allen and Unwin, 1968 [French Version, Paris, 1965]) and James Sweet, Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441–1770 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

[3] Ann Hilton, The Kingdom of Kongo (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), for the role of the Capuchins in discovering problems with Kongo's Christianity. John Thornton, ‘The Kingdom of Kongo and the Counter-Reformation’, Social Sciences and Missions 26 (2013): 40–58 contextualizes their role and their problems with Kongo's Christianity.

[4] Adrian Hastings, The Church in Africa, 1450–1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994); this position is often implicit in the many histories written by clerical historians such as Jean Cuvelier, Louis Jadin, François Bontinck, Teobaldo Filesi, Carlo Toso and Graziano Saccardo, whose work has presented modern editions of the classical work of the Capuchin missionaries, commentaries and at times regional histories, such as Saccardo, Congo e Angola con la storia del missionari Capuccini, Vol. 3 (Venice: Curia Provinciale dei Cappuccini, 1982–1983). For both a position of dependence on missionaries and a recognition of local education, Louis Jadin, ‘Les survivances chrétiennes au Congo au XIXe siècle’, Études d'histoire africaine 1 (1970): 137–85.

[5] It is not mentioned at all in his seminal work, Thompson, Flash of the Spirit in the nearly 100-page section dealing with Kongo and its influence in Vodou, nor in Face of the Gods.

[6] Erwan Dianteill, ‘Kongo à Cuba: Transformations d'une religion africaine', Archives de Sciences Sociales de Religion 117 (2002): 59–80.

[7] Todd Ochoa, Society of the Dead: Quita Manaquita and Palo Praise in Cuba (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), pp. 8–10. Wyatt MacGaffey's work, especially Religion and Society in Central Africa: The BaKongo of Lower Zaire (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1986) is a favorite.

[8] Thiago Sapede, Muana Congo, Muana Nzambi a Mpungu: Poder e Catolicismo no reino do Congo pós-restauração (1769–1795) (São Paulo: Alameda, 2014) is the first book length study of Christianity in the later period of Kongo's history.

[9] John Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism in the Kingdom of Kongo', Journal of African History 54 (2013): 53–77.

[10] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism'.

[11] Sapede, Muana Congo, pp. 248–57.

[12] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism', for the details of the struggle, but a perspective that sees the Capuchin mission as central to Kongo Christianity, see Saccardo, Congo e Angola.

[13] John Thornton, The Kongolese Saint Anthony: D Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

[14] Rafael Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, Academia das Cienças de Lisboa, MS Vermelho 396, pp. 32–4, 183–5 (transcription by Arlindo Carreira, 2007 at http://www.arlindo-correia.com/161007.html) which marks the pagination of the original MS.

[15] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo', pp. 110–4.

[16] Raimondo da Dicomano, ‘Informazione' (1798), pp. 1–2. The text exists in both the Italian original and a Portuguese translation made at the same time. For an edition of both, see the transcription of Arlindo Carreira, 2010 (http://www.arlindo-correia.com/121208.html).

[17] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Teobaldo Filesi, ‘L'epilogo della ‘Missio Antiqua’ dei cappuccini nel regno de Congo (1800–1835)’, Euntes Docete 23 (1970), pp. 433–4.

[18] Among the first was Domingos Pereira da Silva Sardinha in 1854, who, according to King Henrique II of Kongo, had performed his duties of administering the sacraments with ‘all the necessary prudence', Henrique II to Vicar General of Angola, December 14, 1855, Boletim Oficial de Angola, 540 (1856).

[19] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon, Códice 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, October 27, 1856.

[20] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, pp. 110–4.

[21] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7 (of manuscript).

[22] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 39, 69, 276.

[23] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagen', p. 217 (thanks to Thiago Sapede for this reference).

[24] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem’, pp. 32–4, 1835.

[25] For a thorough study of these religious artefacts and their meaning, see Cécile Fromont, The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

[26] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 78.

[27] APF Congo 5, fols. 298–298v (Rosario dal Parco) ‘Informazione 1760' A French translation is found in Louis Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation du Congo, et rite d’élection des rois en 1775, d'après le P. Cherubino da Savona, missionaire de 1759 à 1774', Bulletin de l'Institut Historique Belge de Rome 35 (1963): 347–419 (marking foliation of original MS).

[28] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[29] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 53.

[30] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[31] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[32] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 196.

[33] Bernard Clist et alia, ‘The Elusive Archeology of Kongo Urbanism, the Case of Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi (Lower Congo, DRC)’, African Archaeological Review 32 (2014) 369–412 and Charlotte Verhaeghe, ‘Funeraire rituelen en het Kongo Konigrijk: De betekenis van de schelp- en glaskralen en de begraafplaats van Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi, Neder-Kongo' (MA thesis, University of Ghent, 2014), pp. 44–50.

[34] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[35] ‘O Congo em 1845: Roteiro da viagem ao Reino de Congo por Major A. J. Castro … ’, Boletim de Sociedade de Geographia de Lisboa II series, 2 (1880), pp. 53–67. The orthographic irregularity reflects the actual pronunciation of these terms in the São Salvador region (the Sansala dialect).

[36] Alfredo de Sarmento, Os sertões d'Africa (Apontamentos do viagem) (Lisbon: Artur da Silva, 1880), p. 49 and Adolf Bastian, Ein Besuch in San Salvador: Der Hauptstadt des Königreichs Congo (Bremen: Heinrich Strack, 1859), pp. 61–2.

[37] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 102–3 and da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[38] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 137.

[39] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[40] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[41] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 32–4; da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7; Zanobio Maria da Firenze, ‘Relazione della Stato in cui si trovassi autalmente il Regno di Congo … 1814’, July 10, 1816, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 420–1.

[42] Archivio ‘De Propaganda Fide' (Rome) Acta 1758, ff 213–9, no. 16, Relazione di Rosario dal Parco, July 31, 1758. These large numbers were not simply priests catching up on people who had not been baptized for a long time, as personnel staffing and statistics are found from 1752 onward; but the priests did not cover the whole country every year, so many priests would baptize babies all under age two or three.

[43] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[44] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[45] da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[46] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[47] Francisco das Necessidades, Report, March 15, 1845, in Arquivo do Archibispado de Angola, Correspondência de Congo, 1845–1892, cited in François Bontinck, ‘Notes complimentaire sur Dom Nicolau Agua Rosada e Sardonia’, African Historical Studies 2 (1969): 105, n. 6. Unfortunately, no researchers have been allowed to work in this section of the archive for many years and so the actual text is not available.

[48] Report of November 13, 1856 in António Brásio, ‘Monumenta Missionalia Africana’, Portugal em Africa 50 (1952), pp. 114–7.

[49] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, de Outubro de 27, 1856.

[50] Da Cruz, entry of October 8 and 25 on the problems of baptizing people.

[51] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', is the first to describe this process; for more detail see Bastian, Besuch.

[52] David Eltis, An Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

[53] For a recent discussion of names and nomenclature, see Jésus Guanche, Africanía y etnicidad en Cuba (los componentes étnicos africanos y sus múltiples demoninaciones (Havana: Editoria de Ciencias Sociales, 2008). As we shall see, a number of other subdivisions also derived from the kingdom like the Musolongos, Batas and others.

[54] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Formation of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), for Cuba in particular, Matt Childs, ‘Recreating African Identities in Cuba', in The Black Urban Atlantic in the Era of the Slave Trade, eds. Jorge Cañizares-Esquerra, Matt Childs, and James Sidbury (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), pp. 85–100.

[55] Robert Jameson, Letters from Havana in the Year 1820 … (London: John Miller, 1821), pp. 20–2 (from letter II).

[56] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Brujos (Havana: Liberia de F. Fé, 1906), pp. 81–5; and further developed in ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Editoriales Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), pp. 12–34; for a more recent statement based on more research, Matt Childs, The 1812 Aponte Rebellion and the Struggle Against Atlantic Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), pp. 209–45 and María del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Andrés Rodríguez Reyes, and Milagros Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo de “nación” a la casa de santo (Havana: Fundación Fernando Ortiz, 2012).

[57] For example, the now famous community of Pindar del Rio, see Natalia Bolívar Arostegui, Ta Makuende Yaya y las Reglas de Palo Monte: Mayombe, brillumba, kimbisa, shamalongo (Havana: Ediciones UNION, 1998).

[58] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, pp. 209–12; Jane Landers, ‘Catholic Conspirators: Religious Rebels in Nineteenth Century Cuba', Slavery and Abolition 36 (2015): 495–520.

[59] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 62–112; María del Carmen Barcia, Los ilustres apellidos: Negros en la Habana colonial (Havana: Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad, 2008), pp. 45–151; Barcia, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del Cabildo which carefully demolishes the earlier theses of Fernando Ortiz and others that the cabildos grew out of the brotherhoods.

[60] This group must have split or been replaced by another, for a property dispute in the Congos Loangos relates to their foundation in 1776, Archivo Nacional de Cuba (ANC) Escribanía Valerio-Ramirez (VR) legajo 698, no. 10.205.

[61] Barcia, Iustres Apellidos, pp. 45–151.

[62] Barcia, Ilustres Apellidos.

[63] del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo, pp. 12–9.

[64] Fernando Ortiz, ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Ediciones Ciencas Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), p. 13, citing documents in El Curioso Americano, 1899, p. 73.

[65] Proclama que en un cabildo de negros congos de la ciudad de La Habana, prononció por su Presidente Rey Siliman Mofundi Siliman … (Havana: np, 1808); for the claim of superiority, drawn from an ambiguous statement that he was ‘more black that you others’, see Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 25–7 and 311, footnotes 4 and 6. For political context, see Ada Ferrer, Freedom's Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 247–9.

[66] Fredrika Bremer, Hemmen i den Nya Världen, 2nd ed., Vol. 3 (Stockholm: Tidens forläg, 1854), p. 142 (English translation as The Homes of the New World: Impressions of America, Vol. 2 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1853), p. 322) Her host's name is given in the original and obscured in the translation as ‘C—'.

[67] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 146–8 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 325–8).

[68] Henri Dumont, Antropologia y patologia comparadas de los Negros escalvos, 1876, trans. Israel Castellanos (Havana: Molina, 1922), p. 38.

[69] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 172–4 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 348–9).

[70] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[71] Esteban Pichardo, Diccionario provincial de voces Cubanas (Matanzas: Imprenta de la Real Marina, 1836), p. 72. Musundi may refer to Kongo's northern province of Nsundi, though the match is not exact since the nasal ‘n' is not incorporated into it, musundi might also mean ‘excellent', as the Virgin Mary was called ‘Musundi Madia' in the Kongo catechism meaning exactly this.

[72] It is possible that Bremer attended the dance of another Cabildo of Congos Reales, who were in the process of declaring their insolvency in 1851, ANC Escrabanía Joaquin Trujillo (JT) leg 84, no. 12, 1851; for a 1867 dispute, see the property case involving them in ANC VR leg. 393, no. 5875; other mentions of cabildos of this name including the group from 1865–1871 in Carmen Barcia, Ilustres apellidos, p. 408. For the 1880s mentions, see Archivio Historico de la Provincia de Matanzas (henceforward AHPM), Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882; no. 65, January 9, 1898 and no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[73] Fondo Fernando Ortiz, Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, 5.

[74] ANC Escibanía d'Daumas (ED) leg 917, no. 6. (foliation uncertain, very deteriorated document).

[75] António de Oliveira de Cadornega, História das guerras angolanas (1680–81 ), eds. Matias de Delgado and da Cunha, Vol. 3 (Lisbon: Agência Geral do Ultramar, 1940–1942, reprinted 1972), p. 3, 193. In July 2011, I drove through all three dialect zones, confirmed some of the differences by hearing them spoken and by speaking with people about these differences. My thanks to Father Gabriele Bortolami, OFMCap for driving, interacting with people, impromptu language updates and occasional lessons in the etiquette of dialect use in northern Angola.

[76] Cherubino da Savona, ‘Breve ragguaglio del Congo … ’, fols. 41v–44v, published with original foliation marked in Carlo Toso, ed., ‘Relazioni inedite di P. Cherubino Cassinis da Savona sul ‘Regno del Congo e sue Missioni’, L'Italia Francescana 45 (1974): 135–214. The foliation of the original is also marked in the French translation, found in Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation au Congo … '

[77] ANC ED, leg 494, no. 1, fols 96–97. This text was included in papers dealing with another dispute in 1827–1828 and in 1832–1836.

[78] ANC ED, leg 548, no. 11, fol. 9–9v; José Pacheco, January 21, 1806; ANC ED, leg. 660, no. 8, fols. 1–4; Pedro José Santa Cruz (a request for its own capataz) 1806; for the later dispute ANC ED leg 494, no. 1.

[79] ANC ED, leg 660, no. 8, fol. 4.

[80] ANC JT, leg. 84, no. 13 passim, 1851.

[81] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882.

[82] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 65, January 9, 1898.

[83] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[84] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 55–61 and Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Delgado, Cabildo de nación.

[85] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, p. 112 and ‘Identity', p. 91.

[86] Consider the temporal range of inquisition cases cited in Tania Chappi, Demonios en La Habana: Episodios de la Inquisición en Cuba (Havana: Oficinia del Hisoriador de la Ciudad, 2001). For an example of the sort of persecution the Inquisition could do, and the sort of information that can be obtained from their records, see James Sweet's study of slave religious life in Brazil, Recreating Africa.

[87] Jameson, Letters, pp. 20–2.

[88] See the transcript of his interview published in Henry Lovejoy, ‘Old Oyo Influences on the Transformation of Lucumí Identity in Colonial Cuba' (PhD diss., UCLA, 2012), pp. 230–46.

[89] Aisha Finch, Rethinking Slave Rebellion in Cuba: La Escalera and the Insurgencies of 1841–44 (Chapel Hill: North Carolina Press, 2015), pp. 199–220. Finch attributes most of the activities in these cases to the non-Christian part of Kongo religion, or an early form of Palo Mayombe; see also Miguel Sabater, ‘La conspiración de La Escalera: Otra vuelta de la tuerca', Boletín del Archivo Nacional 12 (2000): 23–33 (with quotations from trial records).

[90] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[91] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 211–3 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 379–83).

[92] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 26, citing late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources.

[93] Abiel Abbott, Letters Written in the Interior of Cuba … (Boston, MA: Bowles and Dearborn, 1829), pp. 15–7.

[94] Cabrera did not employ any orthography of contemporary Kikongo in her day, but it is not at all difficult to recognize her ear for that language, which she did not speak, and most quotations she provided are readily intelligible.

[95] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5. This list, written in a different hand than Ortiz’, one that was shakier with large letters, on fragile aged paper (perhaps school paper) was, I believe, compiled by a literate person who was a native speaker of the language, based on his use of Kikongo grammatical forms (use of verb conjugations and class concords in particular).

[96] Armin Schwegler, ‘On the (Sensational) Survival of Kikongo in Twentieth Century Cuba', Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 15 (2000): 159–65; Jesús Fuentes Guerra, La Regla de Palo Monte: Un acercamiento a la Bantuidad Cubana (Havana: Iberoamericana Vervuert, 2012) (neither Schwegler nor Fuentes Guerra had access to Puyo's vocabulary in Ortiz’ documentation, the contention of its identity with Kikongo is my own). It seems likely that both Cabrera's and Ortiz’ vocabularies were collected probably from old native speakers, who entered Cuba at the end of the slave trade.

[97] For example, the class marker ki in the southern dialect is –ci in the north; use of ‘l' versus ‘d' would be another difference. The northern dialect is well attested in dictionaries of the French mission to Loango and Kakongo in the 1770s, compared with seventeenth- and nineteenth-century dictionaries of the southern dialects. I have also heard these differences myself in Angola.

[98] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Esclavos (Havana: Bimestre Habana, 1916), pp. 25, 32 (clearly, testimony from the same informant).

[99] Ortiz, Negros Esclavos, p. 34. The term ‘Totila', clearly derived from the Kikongo ntotela meaning ‘king'. The word is first attested in the Kikongo dictionary of 1648, as meaning ‘King'. In 1901, King Pedro VI of Kongo, writing in Kikongo, styled himself ‘Ntinu Ntotela NeKongo' Archives of the Baptist Missionary Society (Regents’ Park College, Oxford) A 124 (both ntinu and ntotela can be glossed as ‘king').

[100] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 15.

[101] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 109. Cabrera, for her part, then told him of Nzinga a Nkuwu's baptism in 1491, presumably from one of the historical accounts she had read.

[102] On the assertions of Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita, see Thornton, Kongolese Saint Anthony; on the representation of Christ as an Kongolese, Fromont, Art of Conversion.

[103] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 93.

[104] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 58.

[105] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 59.

[106] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 14.

[107] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 19.

[108] The problem was apparent to Lydia Cabrera in her study of Palo, El Regla de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe (Miami: Ediciones Universal, 1979), pp. 120–30, as one can see from the defensive tone of her informants, probably speaking with her post-1960 experience (this is not seen as a problem in her earlier publication, El Monte (Havana, 1954)).

[109] Cabrera, Vocabulario, p. 123.

[110] Cabrera, Monte, pp. 119–23 passim (here, often used in the context of witchcraft); Reglas de Congo, pp. 24–5. In W. Holman Bentley, Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language (London: Kegan Paul, 1887), p. 361, which relates to the Kinsansala dialect (the most likely associated with Christianity) in the 1880s, mvumbi meant simply the corpse of a dead person; in the 1648 dictionary ‘spirits' was rendered as ‘mioio mia mvumbi' (or souls of corpses).

[111] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. In Kikongo, mvumbi means a corpse, the lifeless remains of a dead person, and the name of an ancestor would usually have been nkulu, though this usage would still make sense in Kikongo.

[112] See John Thornton, ‘Central African Names and African American Naming Patterns', William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series, 50 (1993): 727–42.

[113] The denunciation of the first tooth ceremony is only attested in the general complaints of the Capuchins in the 1650s, written by Serafino da Cortona.

[114] ‘Kisi malongo' appears to be ‘nkisi malongo'. A more likely way to say ‘the teaching of nkisi' would be ‘malongo ma nkisi', so the word order puzzles me. However, word order in Kikongo is flexible and should the speaker wish to emphasize the teaching spiritual part, it might be feasible to use this order.

[115] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. My translation of the phrase ‘nganga la musi' assumes that the speaker has only partial command of Kikongo grammar and would be ‘nganga a mu nsi' The same informant used the term kisi malongo, and perhaps as a Cuban-born person was not secure in the language.

[116] Cabrera, Regla de Congo, p. 23.

[117] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5.

#The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion#Palo Mayombe#ATR#African Traditional Religions#Kongo#Reglas De congo#Nkisi#Kikongo

1 note

·

View note

Text

Awesome! 😀

The Jungle Kingdom The Super Mario Bros. Movie (2023)

#donkey kong#dk#the jungle kingdom#the super mario bros movie#super mario brothers#mario brothers#mario bros#super mario bros#mario#super mario#illumination mario#illumination#kongo bongo island#donkey kong island#donkey kong country#dkc

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Like halfway through "how Europe underdeveloped Africa" cause I decided I'd read/listen to it after I had a strong base on knowledge on African history and just holy fuck is he right about nearly everything so far.

Having learned about how extensive African trade was prior to the 18th century and how heavily most African kingdoms shifted in the 16th it's very clear that what he points out in the way the slave trade and the need to aquire firearms grew the European economies while near completely emptying out African economies and how the hard shift to European import goods after Europe had grow through the use of African slave labor and monopoly of trade routes is still a largely still at play in the era of neocolonialism.

The way that Walter Rodney not just points out that this is true, but the depth to which he covers a variety of African kingdoms, their economies, and cultural practices puts even some college level courses to shame while also showcasing the exact ways in which some of these stronger or more expansive kingdoms like the Ashanti, oyo, borno, Kongo, and Benin kingdoms had explicitly tried everything to get guns through any other trade and how the Ashanti, merina, Ethiopian, Burundi Benin kingdoms sought our education and scholars to begin industrialization and the systematic way in which Europeans and Americans prevented that is just, well it's damming.

It's a continuing reminder how from the first stage of European expansion and control they had precisely zero good intentions for the peoples of Africa. That Europe saw Africa as nothing more than a way to grow itself, it's institutions and improve its economies by depriving Africa of labor, materials and freedom which is true to this day, most starkly in the Congo but true across the whole region.

But while the book shows the crimes of Europeans without sugar coating, it also doesn't glorify the African leaders and more importantly those that became collaborative with European despitism. It also does not abide by the word games the European powers like to play and goes in depth to the way Europeans had no actual interest in ending slavery, and that while invading the various kingdoms and communities to "end slavery" the created some of the most brutal slave conditions on this side of the globe, not just in Leopolds Congo but in French forced labor camps and British controlled regions, with the Portuguese being particularly up front about it.

Truly a shame that like most other black radicals Rodney was murdered so young. The rarity to which black radicals even get to 40 shows how desperately capitalist and white supremist try to prevent even the slightest push back from black voices. It also makes clear how much we all need to know this stuff, from debois's black reconstruction to nkrumah's neoimperialism these books give a great understanding of the past and the precise way in which we arrived to the current situation.

I pray that with the new scramble for Africa that is unfolding in front of our very faces, the genocides in the Congo, and Sudan, and the way in which these interlock with the genocide of Palestinians, that we all take the time to properly read and reflect so that we may properly organize and fight back for a fully free and sovereign Africa and Palestine and a world free from white supremacy.

#black liberation#colonization#politics#indigenous liberation#world of the oppressed#pan african#the colonized#How Europe underdeveloped Africa#walter rodney

674 notes

·

View notes

Note

I know you don't usually do these kinds of posts, but you're probably one of the most implicated in black history month people that I follow so I wanted to ask you, as I already value your opinions in Acotar, what do you think of the documentary where actual historians claim Cleopatra was a black woman? Lately, this has been a pretty active topic on my fyp on TikTok, and I wanted to know a black woman's perspective on this.

Thank you in advance, and if you usually don't answer these questions or don't want to answer this one, I'll totally understand, and there's no problem at all.

I didn’t know there was a new documentary out, but when I saw the name Cleopatra I automatically sighed because I knew what was coming. This is a subject a know a little 🤏🏾 about, actually, because I researched it a bit myself in my last year of high school (and stopped because of the uh. NASTINESS associated with this particular subject) and though it’s been a few years I remembered some main, basic things, and I wanted to check a few things first.

At best, in the most CHARITABLE interpretation as far as I in my limited knowledge can tell, it would be correct to say that’s it’s POSSIBLE that she MAY have been mixed Black because, though she was part of the GREEK Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled Egypt (Ptolemy being one of Alexander the Great’s generals who got the Egyptian portion of his empire after Alexander died), that’s on her fathers side; her mother’s exact ethnicity isn’t known. Not that this won’t stop the hoteps from running off and claiming her and all of ancient Egypt as Black though So some have ***speculated*** that her mother—and thus Cleopatra—may have potentially been part Egyptian (and that goes into the issue of deciding that the “Egyptian” in this instance had to have been Black rather than MENA but that’s again a whole other can of worms). BUT it’s more likely that her mother was Greek due to the uh, PRACTICE™️ of inbreeding and it not being common for the dynasty to marry Egyptians. So it’s more probable that she was fully Greek/Macedonian and not part Egyptian, much less part Black. (Also some historians speculate she may have had Persian blood? I guess? Again it’s a can of worms, not something i’m digging deep into because of the nastiness that you often stumble across) Unless there’s a new study confirming her mother’s identity or something that I missed, it’s simply incorrect to claim that Cleopatra was undeniably Black, because though it is ***possible*** she most likely ***wasn’t.***

But this topic really upsets me, because there are LEGITIMATE Black kingdoms and empires who were mighty and well developed and powerful like the Aksumite empire and kingdoms of Kongo and Loango and the Great Zimbabwe empire and the empires of Ghana and Mali and Songhay and the Ashanti kingdom and the WHOLE SWAHILI COAST THAT WAS INVOLVED IN THE INDIAN OCEAN TRADE ROUTE and they had their own great rulers, their own kings and queens and emperors and empresses, their palaces and castles, their own cities and towns, their own complex civilizations and dynastic royal families that deserve the attention Cleopatra and ancient Egypt get. They were erased—and Egypt was not—by white people to prop themselves up as the only race capable of forming civilizations and advanced societies as a means of justifying colonization and imperialism to “civilize” the rest of the world and as a result many of those other empires have been erased from our education system here in the states and many people cling to ancient Egypt as proof that we’re not inferior and aren’t savages like white people claim due to believing that since Egypt’s in Africa it had to have been mostly Black when Egypt, and the Ptolemaic dynasty and Cleopatra in PARTICULAR, are literally the worst example that could’ve been chosen and were the only African kingdom spared erasure FOR A REASON.

Anyway, I don’t like it, it’s disingenuous and does US wrong because we need to give that energy to other African kingdoms that need and could use the fame Egypt + Cleopatra get, and we deserve a better education system to teach us this stuff. I hope this answers your question? And I don’t mind any kinds of asks 🥰

#I get the desire to claim Egypt because I remember in high school a racist white guy asked why Africans didn’t build their own civilizations#And that’s what sent me researching in the first place so I truly get the frustration but black women we can do BETTER#ask#anon#cleopatra#egypt#africa#racism#Don’t come at me in my inbox yall#antiblackness

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Kimpa Vita: The Kongolese Prophet and Leader of Antonianism

Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita, also known as Kimpa Mvita, Tsimpa Vita, or Tchimpa Vita (1684–2 July 1706), was a Kongolese prophet and leader of her own Christian religion, Antonianism, which preached that Jesus and other early Christian luminaries were from the Kongo Kingdom. The name “Dona” denotes that she was born into a family of high Kongolese aristocracy; she was later given the name “Beatriz”…

View On WordPress

#African History#Antonianism#central africa history#Congo History#Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita#Kimpa Mvita#Kongo Kingdom#Kongolese prophet#Tchimpa Vita#Tsimpa Vita

1 note

·

View note

Text

Do you know that Ganga Zumbi, the African Spartacus was born in Kongo in 163O, enslaved and shipped to Brazil to work as a plantation slave? He managed to escape, raised an army of eslaved Africans and founded his own kingdom of Palmares, with a palace and court.

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

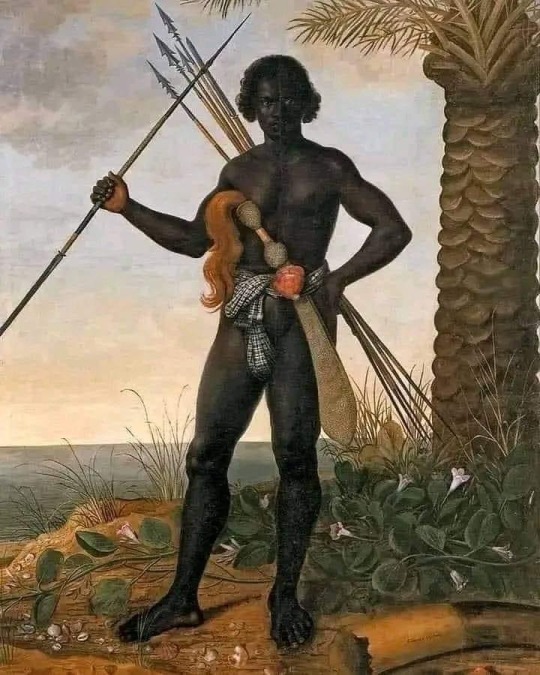

Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo (14-19th century CE) was located on the western coast of central Africa in modern-day DR of Congo and Angola. Prospering on the regional trade of copper, ivory, and slaves along the Congo River, the kingdom's wealth was boosted by the arrival of Portuguese traders in the late 15th century CE who expanded even further the slave trade in the region. Kongo kings were converted to Christianity but relations with the Europeans deteriorated as each side attempted to dominate the other. Civil wars and defeats to rival neighbouring kingdoms finally saw the Kongo state collapse in the early 18th century CE. The Portuguese reinstalled the position of the Kongo monarchs, and the state limped on in name only well into the 19th century CE but the kingdom's days as the strongest power in west-central Africa were now but a distant memory.

Formation & Territory

Located on the western coast of central Africa and south of the Congo River (formerly known as the Zaire River), the kingdom arose in the late 14th century CE following the alliance of several local principalities which had been in existence since the second half of the first millennium CE. Kongo, dominated by Bantu-speaking peoples, had its capital at Mbanza Kongo - known to the Kongolese as Banza, meaning 'residence of the king' - which was located on a fertile and well-watered plateau just below the western end of the Congo River. The kingdom expanded its territory further by a gradual process of military conquest, probably motivated above all by a desire to acquire slaves. At its peak in the 15th and 16th century CE, the kingdom controlled some 240 km (150 miles) of the coast from the Congo River in the north to just short of the Cuanza River in the south, and spread some 400 km (250 miles) into the interior of central Africa up to the Kwango River.

Continue reading...

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝗚𝗢𝗠𝗔 𝗥𝗘𝗦𝗜𝗗𝗘𝗡𝗧𝗦 𝗖𝗘𝗟𝗘𝗕𝗥𝗔𝗧𝗘 𝗔𝗦 𝗠𝟮𝟯 𝗥𝗘𝗕𝗘𝗟𝗦 𝗘𝗡𝗧𝗘𝗥 𝗚𝗢𝗠𝗔 𝗔𝗙𝗧𝗘𝗥 𝗖𝗢𝗡𝗚𝗢𝗟𝗘𝗦𝗘 𝗦𝗢𝗟𝗗𝗜𝗘𝗥𝗦 𝗥𝗔𝗡. 𝗪𝗛𝗬?

Panafricanlifestyle on the Gram made a solid post explaining the problem in the Congo: The Banyamulenge, or the Banyamulenge people, are an ethnic group formed through forced intermixing. This occurred when refugees, primarily Tutsis and some Hutus, fled the Rwandan genocide and sought asylum in eastern Congo. The Congolese people welcomed them, but over time, the Rwandan government began using these refugees as a pretext to annex eastern Congo. To solidify their presence, they orchestrated intermarriages with Congolese people, creating a new blended group that, while now holding Congolese citizenship, is not indigenous to Congo.

Historically, before the Berlin Conference imposed colonial borders, the Kingdom of Kongo encompassed what is today the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Angola, parts of Gabon, parts of Zambia, and a significant portion of Rwanda, which was later severed and given to Rwanda. If any land were to be reclaimed, it would be by Congo. However, unlike its aggressors, Congo has never invaded or sought to reclaim lost territories.

Figures like Paul Kagame and Yoweri Museveni have acted as proxies for Western powers, notably the United States, France, Belgium, and the United Kingdom, facilitating war to destabilize Congo and plunder its resources. Additionally, major tech companies, including Glencore, Microsoft, Alphabet (Google), Tesla, and Apple, have indirectly funded the ethnic cleansing of indigenous Congolese people by profiting from Congo’s resource exploitation.

Despite Congo’s 300+ tribes and numerous indigenous languages, none trace their heritage to Kinyarwanda, Tutsi, or Hutu. In a diplomatic move, President Félix Tshisekedi granted the Banyamulenge Congolese citizenship, recognizing them as Congolese in nationality only, but not in ethnicity, heritage, or ancestry. The claim that they are indigenous is a revisionist narrative, primarily pushed by Rwanda, to justify land annexation, ethnic cleansing, and the continued plundering of Congolese resources.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bottle tree in St. George, South Carolina. Photo by Brandon Coffey.

Thought to have originated in the Kingdom of Kongo on the western coast of Africa, bottle trees have a long and storied history. When enslaved people were transported to America and the islands, they brought their traditions with them. Just like much of Southern coastal cuisine originates from slavery times, bottle trees do as well. Brightly colored bottles are placed on tree branches for the sake of attracting evil spirits who would then become distracted and trapped in the bottles, protecting the home in the process. This one was found outside of St. George, South Carolina.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

A nganga (pl. banganga or kimbanda) is a spiritual healer, diviner, and ritual specialist in traditional Kongo religion. These experts also exist across the African diaspora in countries where Kongo and Mbundu people were transported during the Atlantic slave trade, such as Brazil, the southern United States, Haiti and Cuba.

Nganga means "expert" in the Kikongo language. The Portuguese corruption of the meaning was "fetisher." It could also be derived from -ganga, which means "medicine" in Proto-Bantu. As this term is a multiple reflex of a Proto-Bantu root, there are slight variations on the term throughout the entire Bantu-speaking world

In the Kingdom of Kongo and the Kingdom of Ndongo, expert healers, known as banganga, underwent extensive training to commune with the ancestors in the spiritual realms and seek guidance from them. They possessed the skill to communicate with the ancestors in the spiritual realm, or Ku Mpémba, as well as divining the cause of illness, misfortune and social stress and preparing measures to address them, often by supernatural means and sacred medicine, or minkisi.

They were also responsible for charging a nkisi, or physical objects intended to be the receptacle for spiritual forces that heal and protect its owner. When Kongo converted to Christianity in the late fifteenth century, the term nganga was used to translate Christian priest as well as traditional spiritual mediators. In modern Kongo Christianity, priests are often called "Nganga a Nzambi" or "priests of God."[citation needed] The owner and operator of an nkisi, who ministered its powers to others, was the nganga.

An English missionary describes how an nganga looks during his healing performance:

Thick circles of white around the eyes, a patch of red across the forehead, broad stripes of yellow are drawn down the cheeks, bands of red, white, or yellow run down the arms and across the chest.... His dress consists of the softened skins of wild animals, either whole or in strips, feathers of birds, dried fibres and leaves, ornaments of leopard, crocodile or rat's teeth, small tinkling bells, rattling seedpods...

This wild appearance was intended to create a frightening effect, or kimbulua in the Kongo language. The nganga's costume was often modeled on his nkisi. The act of putting on the costume was itself part of the performance; all participants were marked with red and white stripes, called makila, for protection.

The "circles of white around the eyes" refer to mamoni lines (from the verb mona, to see). These lines purport to indicate the ability to see hidden sources of illness and evil.

Yombe nganga often wore white masks, whose color represented the spirit of a deceased person. White was also associated with justice, order, truth, invulnerability, and insight: all virtues associated with the nganga.

The nganga is instructed in the composition of the nkondi, perhaps in a dream, by a particular spirit. In one description of the banganga's process, the nganga then cuts down a tree for the wood that s/he will use to construct the nkondi. S/he then kills a chicken, which causes the death of a hunter who has been successful in killing game and whose captive soul subsequently animates the nkondi figure. Based on this process, Gell writes that the nkondi is a figure an index of cumulative agency, a "visible knot tying together an invisible skein of spatio-temporal relations" of which participants in the ritual are aware

#nganga#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#afrakans#african culture#afrakan spirituality#african american#african spirituality#nkondi#nkisi#central africa#gells#spatio temporal

8 notes

·

View notes