#Soviet hotels

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

prequel comic pg. 1

(click for quality)

#ardeo rh!au#rh!au#pravum rh!au#tsams#sams#the sun and moon show#tsams au#sun and moon show#hazbin hotel crossover#solar flare sams#tsams solar flare#killcode sams#tsams killcode#kc sams#sams kc#aaaaaaaa#ulmr#posts by the soviet onion#🧅

95 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An room in the Intourist Hotel overlooking the Kremlin and the Red Square (Moscow, 1978).

584 notes

·

View notes

Text

Half body statue of Sherlock Holmes outside of the Sherlock Art Hotel in Riga, Latvia

#theres a bunch of cool murals and decor inside too#when i end up in europe for a while ive gotta do a sherlock holmes landmarks pilgrimage#sherlock holmes#holmes#statue#statuette#latvia#Šerloks Holmss#Sherlock art hotel#Шерлок Холмс#sherlock holmes statue#sherlock art hotel#riga latvia#riga#ps apparently soviet holmes was filmed in this city

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

Name: Julain

Pronouns: he/him she/her

Gay (MLM), Gender fluid, poly. three partners

Mexican, native American; still learning Spanish and going to learn Russian and my tribe's language.

Main hyperfixations:

Sonic (or Sega in general)

Hazbin/helluva boss

music

History

Schlatt

theater

Gaming (too many to put here lol)

Want more see the reblogs lol

#starkid#soviet#jester#beetlejuice broadway#nightmare before christmas#deltarune#spamton#jschlatt#schlatt#men loving men#gay#genderfluid#polyamory#politics#hazbin hotel#helluva boss#sonic#sega#history#gaming

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Contrast of eras, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

The Soviet style Hotel Uzbekistan and a statute of Amir Timur/Temur, founder of the Timurid Empire which comprised, in part, modern day Uzbekistan

#Tashkent#Uzbekistan#Soviet#hotel#statue#Amir Timur#Amir Temur#Timurid Empire#contrast#architecture#travel#travel photography#Central Asia

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jelgava

#nighttime#night#photography#architecture#jelgava#latvia#latvija#hotel#post soviet#dark aesthetic#darkness#photo#Spotify#aesthetic

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1967 – A day after being captured, Marxist revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara is executed in Bolivia.

Socialist revolutionary and guerilla leader Che Guevara, aged 39, is killed by the Bolivian army. The U.S.-military-backed Bolivian forces captured Guevara on 8 October while battling his band of guerillas in Bolivia and assassinated him the following day. His hands were cut off as proof of death and his body was buried in an unmarked grave. In 1997, Guevara’s remains were found and sent back to…

View On WordPress

#Alberto Korda#Argentina#Che#China#CIA#Co. Clare#Co. Galway#Congo#Cuba#Ernesto Che Guevera#Ernesto Rafael Guevara de la Serna#Fidel Castro#Guatemala#Irish-Argentinian History#Jim Fitzpatrick#Kilkee#revolutionary#Royal Marine Hotel#Soviets#United States#USSR

5 notes

·

View notes

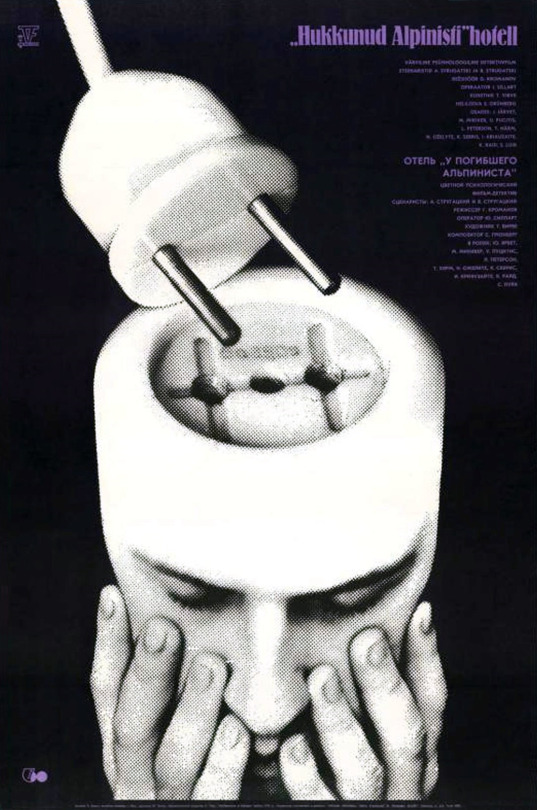

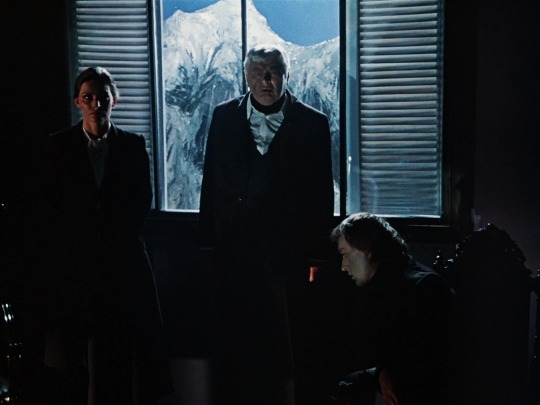

Photo

Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel / 'Hukkunud Alpinisti' hotell (1979, Grigori Kromanov)

2/8/23

#Dead Mountaineer's Hotel#'Hukkunud Alpinisti' hotell#Grigori Kromanov#Uldis Pucitis#Juri Jarvet#Karlis Sebris#Tiit Harm#Boris Strugatskiy#70s#Estonian#Soviet#crime#science fiction#whodunit#mystery#surreal#murder#detective#neo-noir#mountains#Alps#hotel#aliens#avalanche#snow#winter#investigation#conspiracy#androids#cults

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Karosta#a Soviet era prison that's been converted into a hotel and tourist attraction. Liepaja#Latvia [1200x797]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My works about Soviet from 1960s to 1980s

Just for the use of aesthetics and academics only.

#history#illustration#military#soviet#ussr#fiction#coldwar#europe#eastern bloc#eastern europe#uniform#tank#t 64#mig 23#metro#hotel#poland

0 notes

Text

past ardeo ref cuz uhh idk 🤷♀️

I like his lil hooves he pretty

#ardeo rh!au#rh!au#tsams solar flare#solar flare sams#tsams#sams#sams au#tsams au#the sun and moon show#sun and moon show#tgo#the grand occult#posts by the soviet onion#hazbin hotel crossover#hazbin hotel#hh#aaaaaaaa#ulmr#🧅

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life in the Rossiya Hotel in Moscow - photos from the 1971 booklet.

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPECIFIC MOVIE RECOMMENDATIONS #1

🌙✨ Gothic Fairy-Tale Films with Strong Female Leads ✨🌙

🍒❤️🔥Hey lovelies,

If you're like me find endless inspiration in the aesthetics of gothic fairy-tales, then you're in for a treat! I've created a list of enchanting atmospheric films, perfect for a cozy evening with your favorite tea.

To start with, of course, an absolute classic: a folk horror, menstrual tale with possibly the most aesthetically beautiful frames I've ever experienced in cinema. I constantly post something from this film on my blogs.

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970): This surreal Czechoslovakian film follows young Valerie as she discovers a dreamlike world filled with vampires and magic. It's a visually stunning exploration of adolescence and awakening womanhood.

2. Daughters of Darkness (1971): This cult classic Belgian horror film features a mysterious, seductive countess who preys on young lovers in a deserted hotel. it’s a hypnotic blend of gothic allure and vampiric intrigue.

3. Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979): Werner Herzog's remake of the classic silent version. The film captures the gothic essence with stunning visuals and a chilling, melancholic tone. It's a mesmerizing exploration of fear and beauty.

4. The Vampire Lovers (1970): This Hammer Horror classic stars Ingrid Pitt as the alluring vampire Carmilla, who preys on young women in a secluded 19th-century village. it’s a captivating blend of horror and sensuality.

5. Beauty and the Beast (1978): This dark fantasy film, directed by Juraj Herz, offers a unique and eerie retelling of the classic fairy tale.Ideal for those who love a blend of dark romance and fairy-tale magic.

6. Viy (1967): This Soviet horror film, based on Nikolai Gogol's novella, follows a young priest who must spend three nights watching over the body of a witch in a haunted church. With its eerie atmosphere, stunning special effects, and deep roots in Slavic folklore, it's a captivating blend of supernatural horror and gothic fantasy.

That's all for today. I have many more films like these saved on my watchlist, so once I find some gems, I'll make another list. You can also look forward to a list of my favorite old fairy tales adaptations.

Kisses 💌💌

#movie recommendation#gothic cinema#folk fairy tales#cinema#czechoslovak cinema#70's cinema#watchlist

618 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Chinese concentration camp archipelago

by cartesdhistoire/instagram

« Atlas historique mondial », Les Arènes, 2e éd., 2023

2,047 / 5,000 There are two types of detention centers in China: laojiao, under the Public Security, and laogai, under the Ministry of Justice.

Laojiao is a form of administrative punishment imposed solely on people who have committed minor offenses. The term of internment cannot exceed four years. There are an estimated 300,000 prisoners (drug addicts, prostitutes and their clients, petty criminals) in over 300 camps.

Urban prisons and laogai, located in the countryside, include prisons for inmates sentenced to six months to twenty years, the aim of which is to reform the inmates through labor. It is estimated that there are 8 million prisoners in a thousand camps that resort to torture and degrading treatment. Starvation is common, leading to widely documented cases of cannibalism.

Laojiao, like laogai, uses prisoners for economic purposes and, like the Soviet gulag or the Cuban UMAP (Military Units for Aid to Production), it is one of the instruments of the power's territorial planning choices (major construction sites, pioneer fronts).

Beyond forced labor, Harry Wu, a Catholic dissident detained from 1960 to 1979 in the laogai, and founder in 1992 of the Laogai Research Foundation which made this system of camps more widely known in the West, reveals that the Chinese authorities collect organs from prisoners in order to transplant them onto members of the Chinese Communist Party.

It is estimated that 10 million prisoners and internees were held during each year of Mao's reign. 50 million prisoners are said to have passed through these camps since the communists came to power in 1949 and 20 million died there (cold, hunger, disease, fatigue, summary executions, etc.).

This concentration camp system created in 1951 still exists, as do other types of arbitrary detention called “black prisons” (hotels, disused offices, drug rehabilitation centers) where people are humiliated, beaten and tortured.

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

《UrbEx Tskaltubo Series》 - Sanatorium Medea

In the next few weeks, i would like to share series of abandoned sanatoriums in Tskaltubo, the soviet spa town of Georgia. Tskaltubo was famous with the medical treatment using the town healing mineral water at the bath houses/ wellness centres. In its heydays (50s-80s), there were 22 ‘Soviet neoclassicist’ sanatoriums/hotels to accommodate guests from across the USSR for their state-mandated R&R.

Joseph Stalin was one of the VVIP, with even direct trains to Tskaltubo from Moscow (now Tskaltubo railway was abandoned too).

At the fall of the Soviet Union in late 1991, the Tskaltubo’s spa industry collapsed as well. Most of the hotels and resorts closed their doors.

During the 1992/1993 Georgia-Abkhazia conflict, over 9000 of refuges (IDP) arrived Tskaltubo, occupied some of these abandoned properties.

It was supposed to be a temporary arrangement but decades later, these makeshift apartments have become their permanent homes. In 2022-2024, some of these IDP finally relocated to new living complexes as some old sanatoriums sold to new investors.

The first Sanatorium i visited from my 2022 trip was Sanatorium Medea. As we approaching the driveway, greeted by the most impressive facade with the spectacular collumns and curves arches.

It was built between 1954-1962 (326 beds), now a popular spot for wedding photoshoot and some tourists.

163 notes

·

View notes