#Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bothan: Beehive Shieling Dwellings in Harris and Lewis

By Cathy Dagg The following are some musings based on recent visits to some of the shieling structures of North Harris and South Lewis, unusually different from those in the mainland Highlands. There’s no original research involved and I am relying heavily on the notes and plans of previous archaeologists and amateurs who have also been intrigued by these structures. Some background on shieling…

View On WordPress

#airigh#Airigh a&039;Sguair#beehive dwellings#beehive structures#Both a&039; Chlair Bhig#bothan#Captain FWL Thomas#cupboard niche#dairy stores#Fraser Darling#Gearraidh Ascleit#Gearraidh Coire Geurad#Harris archaeology#highland archaeology#Highland Folk Museum#illicit still#Lewis archaeology#Marc Calhoun#Post Medieval archaeology#shielings#Society of Antiquaries of Scotland#St Kilda#tigh earraich#Uig parish

0 notes

Text

you ever end up so far down a fallen london research rabbit hole that you stumble upon 2010s era websites about conspiracies surrounding the 6th Earl of Carnavon being the illegitimate son of a Rothschild and the son of the last Maharajah of Lenore-

#this man is a member of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland#his biggest competitor in autobiographies of Lady Almina Carnavon is the current Lady Carnavon#i am fascinated i love internet rabbit holes

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

On December 18th 1780 the Society of Antiquaries was founded.

The purpose of the Society is set out in the Royal Charter: “…to investigate both antiquities and natural and civil history in general, with the intention that the talents of mankind should be cultivated and that the study of natural and useful sciences should be promoted.

The original members began to donate material to the Society from its inception, and in 1781 it bought a property so that the donations it received could be properly deposited. The Antiquarian Society Hall appears on the Alexander Kincaid A Plan of the City and Suburbs of Edinburgh in 1784, located off the Cowgate and behind Parliament Close off the Royal Mile (then Lawnmarket). After several moves, the Society rented accommodation in the Institution for the Encouragement of the Fine Arts (later the Royal Institution) at the foot of The Mound in 1826 (now the Royal Scottish Academy). A detailed account of the history of the Museum was written by RBK Stevenson, former Keeper of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland and President of the Society, in The Scottish Antiquarian Tradition, edited by A S Bell and published to mark the bicentenary of the Society and its Museum in 1981

In 1841 there were over 4,000 visitors, including the Queen and Prince Albert, to the Society Museum to view the thousands of objects collected over the previous 60 years. By 1850 free admission to this collection was attracting 17,000 visitors per year, which led in turn to the accelerated expansion of the collection as donations flowed in, and to the publication of a 150 page catalogue.

In November 1851 the signing of a Deed of Conveyance with the Board of Manufactures on behalf of Parliament made the Society collections National Property in return for fit and proper accommodation at all times, for the preservation and exhibition of the collection, and also for the Society’s meetings, free of all expense to them. By this time the collections were housed in 24 George Street, they then moved back to the mound before sharing The National Portrait Gallery for a time.

In 1861 construction of the Industrial Museum of Scotland began, with Prince Albert laying the foundation stone. In 1866, renamed the Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art, the eastern end and the Grand Gallery were opened by Prince Alfred. In 1888 the building was finished and in 1904 the institution was renamed the Royal Scottish Museum.

There have been many extensions to the building over the years to accommodate the growing collections, the latest was finished in 2011, giving us the splendid new building adjoined to the old one, they also opened up the basement as a shop and cafeteria, the Society still functions today. the museum is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Scotland and in 2019 approximately 2.2 million visitors passed through it’s doors, the way things are going it will be a while before we see anything like these numbers again.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

A team of archaeologists, co-led by a researcher at the University of Southampton, believe they have located the site of the lost Monastery of Deer in Northeast Scotland. It is believed that the earliest written Scots Gaelic in the world was produced in the monastery in the late 11th and early 12th century. These texts, Gaelic land grants, were placed in the margins of the Book of Deer, a pocket gospel book originally written between 850AD and 1000AD. Academics have long speculated that these entries, or 'addenda' were added while the book was in the monastery. Archaeologists believe they have now found the building's remains just 80 meters from the ruins of Deer Abbey (founded in 1219), close to the village of Mintlaw in Aberdeenshire. Alice Jaspars, Ph.D. researcher from the Archaeology department at the University of Southampton, led the archaeological investigations, working with Site Director Ali Cameron of Cameron Archaeology. They will present their findings in a lecture to the Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (23 November) and also feature in a new documentary about the project for BBC Alba (20 November, 9 pm).

Continue Reading.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ann Forbes, Portrait of the Duchess of Hamilton, c.1760, The Fleming Collection

Anne Forbes (1745–1834) was a Scottish portrait painter, educated in Rome, who worked in London and later in Edinburgh, where she was Portrait Painter to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Although her career in London was cut short by illness, she was one of the first Scottish women artists to make a career from painting. Via Wikipedia

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok time to watch videos recorded by the society of antiquaries of scotland until i fall asleep

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

''A line is not a connection of dots''

Tim Ingold

Anon, (n.d.). ‘Lines: a brief history’ by Tim Ingold | Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. [online] Available at: https://www.socantscot.org/resource/lines-a-brief-history-by-tim-ingold/.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

CLAN & FAMILY CARRUTHERS: More Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland join our pwn Society's ranks.

On the 30th of November 2024, St Andrews Day, the Annual General Meeting of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Scotland took place. At this event, two further members of the Chief’s Council were voted on by the membership and accepted as Fellows of the Society with all the rights and privileges this entails. This takes our total to seven of our Society, who have been given this great honour. A…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Temple of the Muses, Dryburgh, Borders.

The Temple of the Muses, Dryburgh, Borders.

The 11th Earl of Buchan, seldom mentioned without the qualifier ‘eccentric’, bought the Dryburgh estate towards the end of the 18th century. He built a new house and improved the grounds, creating a landscape which featured as its centrepiece that ultimate in garden ornaments: a ruined abbey. Further embellishments included this pretty rotunda on a hillock overlooking the Tweed, and a ‘colossal…

View On WordPress

#Apollo#Canmore#Coade Stone#David Steuart Erskine#Dryburgh Abbey#Earl of Buchan#James Thomson#River Tweed#Robert Burns#Siobhan O&039;Hehir#Society of Antiquaries of Scotland#Temple of the Muses#William Wallace

0 notes

Text

An overlooked thieves’ tool: the dark lantern

“Deacon Brodie’s Dark Lanthorn and False Keys. (From the originals in the Museum of The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.)” | The Trial of Deacon Brodie, 1906

A dark lantern was a type of hand lantern with a sliding shutter, so that the person holding it could adjust how much light it shed, if any. In the early modern period, it was very useful for thieves and assorted shady people lurking about in the dark. Court records even mention them as evidence: “he had a Dark-Lanthorn, and a bunch of Pick-lock Keys”, we read in an Old Bailey report from the 1680s. (The variant lanthorn was "folk etymology based on the common use of horn as a translucent cover".)

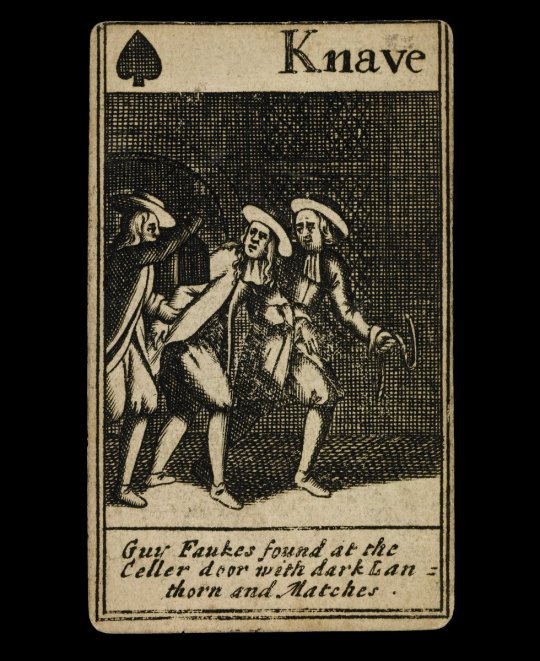

Late 17th century playing card: “The jack (then called the knave) illustrates the discovery of Guy Fawkes in the cellar underneath Parliament – ‘Guy Faukes found at the Celler door with dark Lanthorn and Matches.'” | British Museum

In 1605, Guy Fawkes was caught red-handed under the Parliament with 36 barrels of gunpowder, a slow match, and a dark lantern, and today that lantern can be seen at the University of Oxford.

Guy Fawkes’ lantern | Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

A 1787 fencing manual tells us that the shady people who carried dark lanterns would use them in combat to suddenly blind their opponent. I'm not sure we should take that too seriously, given that you need both hands to open or close the shutter while holding the lantern, which would make a Stab Surprise unpractical. Maybe it was a generic “grab literally anything in your off-hand” move, without mucking about with the shutter, or maybe the trick was “distract them and run”. Or it's wholly made up, who knows. (I don't trust anything fencing manuals tell us about the criminal underworld.)

“The Guard of the Sword and Cloak oppos’d by the Sword & Lanthorn” | Domenico Angelo's The School of Fencing (1787)

The other type of people who found dark lanterns useful was cops. By the Victorian era they were more or less standardised, and policemen carried them on patrol.

A dark lantern with an advertisement for “Bull’s Eye or Dark Lantern, with Signals” | Dark Lantern Tales

“Typical dark lanterns were about the size and shape of a small modern thermos bottle, and had a fount for oil in the bottom. A cap with a wick (or wicks) was mounted directly to the top of this reservoir, and in most models the cap also served as a port to fill it. In the cylindrical body of the lantern, a shutter could be rotated to block light from coming through a large “Bull’s Eye” lens on the front. At the top of the lantern was a vent that allowed exhaust from the flame to exit but retain the light. These distinctive vents were usually made with two metal disks that were stamped into flutes that taper to the middle. The effect is sort of a ruffled top to the whole device. At the back of the lantern were wire handles to protect the user from the hot sides (policemen and watchmen kept them lit for upwards of six hours while on patrol), and usually a clip to hang the lantern on the user’s belt. There are anecdotes that describe patrolmen keeping a lit lantern on their belt beneath their great coat to stay warm in very cold weather.”

~ Dark Lantern Tales

“An 1890s Dark Lantern showing shutter open and closed” | Dark Lantern Tales

Dark lanterns found their way in D&D too. In 5e, the list of adventuring gear includes "hooded lanterns" which do something similar, though you can only reduce the light, not hide it completely. Of course, for the groups that even bother with lighting conditions, the problem is more often solved by asking your friendly spellcaster to cast Light on a pebble or something, and hiding it or holding it at your convenience. And earlier, in 3.5, "Dark Lantern" was an Eberron prestige class (a modified assassin), and also a magic item from Tome of Magic which created shadowy illumination.

Tome of Magic: spoooky Dark Lantern illustration by W. England

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Places to Go: Tullibardine Chapel

A small kirk sheltered by Scots pines, Tullibardine Chapel has an air of tranquility and simple elegance. Formerly the private chapel of the Murrays of Tullibardine, it is one of the few buildings of its kind in Scotland to have survived with many of its medieval details intact.

The Murrays acquired the lands of Tullibardine in the late thirteenth century, when William ‘de Moravia’ married a daughter of the steward of Strathearn. Later, through judicious marriages and court connections, they first became earls of Tullibardine and then Dukes of Atholl. But even as lairds the Murrays were a significant power in late mediaeval Perthshire. In those days Tullibardine Castle was one of their main strongholds, and the close proximity of royal residences like Stirling meant that the Castle also hosted several notable guests. Mary, Queen of Scots, stayed there in December of 1566 (allegedly in the company of the earl of Bothwell). One laird of Tullibardine became Master of Household to the young James VI, while his aunt Annabella Murray, Countess of Mar, oversaw the king’s upbringing. Thus James VI was also a frequent visitor and it was he who created the earldom of Tullibardine in 1606. The king is known to have attended the wedding of the laird of Tullibardine’s daughter Lilias Murray, though it is unclear whether this took place at Tullibardine itself. The castle grounds were probably an impressive sight too: the sixteenth century writer Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie claimed that a group of hawthorns at the “zeit of Tilliebairne”* had been planted in the shape of the Great Michael by some of the wrights who worked on the famous ship.

Thus the tower at Tullibardine, though presumably on a small-scale, was apparently comfortable and imposing enough for the lairds to host royalty and fashion an impressive self-image. But the spiritual needs of a late mediaeval noble family were just as important as their political prestige, and a chapel could both shape the family’s public image and secure their private wellbeing. The current chapel at Tullibardine, which originally stood at a small distance from the castle, was allegedly founded by David Murray in 1446, “in honour of our blessed Saviour”. At least this was the story according to the eighteenth century writer John Spottiswoode, and his assertion is partly supported by the chapel’s internal evidence, though no surviving contemporary document explicitly confirms the tale. A chapel certainly existed by 1455, when a charter in favour of David’s son William Murray of Tullibardine mentions it as an existing structure. In this charter, King James II stated that his “familiar shieldbearer” William Murray has “intended to endow and infeft certain chaplains in the chapel of Tullibardine”. Since the earls of Strathearn had previously endowed a chaplain in the kirk of Muthill, but duties pertaining to the chaplaincy had not been undertaken for some time, James transferred the chaplaincy to Tullibardine. He also granted his patronage and gift of the chaplaincy to William Murray and his heirs.

The charter indicates that Tullibardine Chapel was an important project for the Murrays. Interestingly though, no official references to the chapel in the fifteenth, sixteenth, or seventeenth centuries describe Tullibardine chapel as a collegiate church, even though later writers have frequently claimed this. Collegiate foundations were increasingly popular with the Scottish nobility during the late Middle Ages, but, although such a foundation might have been planned for Tullibardine, there is no evidence that this ever took place.

The 1455 charter serves as an early indication of the chapel’s purpose and significance. Judging by its architecture the current chapel does appear to have been constructed in the mid-fifteenth century. However it was also substantially remodelled and enlarged around 1500, when the western tower was added. One remnant of the original design is the late Gothic ‘uncusped’ loop tracery on the windows. Despite the apparent simplicity of the chapel, features such as this window tracery have been taken as evidence that its builder was acutely aware of contemporary European architectural fashions. Another interesting feature is the survival of the chapel’s original timber collarbeam roof, a rare thing in Scotland. Several coats of arms belonging to members of the Murray family adorn the walls and roof corbels, although some of these armorial panels were probably moved when the chapel was reconstructed. They include the arms of the chapel’s alleged founder David Murray and his wife Margaret Colquhoun, as well as those of his parents, another David Murray and Isabel Stewart. A later member of the family, Andrew Murray, married a lady named Margaret Barclay c.1499, around the same time that the chapel was renovated, and although they were buried elsewhere, their coats of arms can also be seen there. Aside from such details- carved in stone and thus less perishable than books and vestments- the chapel’s interior seems quite sparse and bare today. Originally though the mediaeval building probably housed several richly furnished altars and some of the piscinas (hand-washing stations for priests) can still be seen in the walls. But the sumptuous display favoured in even the smallest mediaeval chapels was soon to be swept away entirely by the Reformation of 1560, when Scotland broke with the Catholic Church and Protestantism became the established faith of the realm.

Tullibardine was used chiefly as a private burial place after the Reformation, but there are signs that the transition from one faith to another was not entirely smooth. Four years after the “official” Reformation, a priest named Sir Patrick Fergy was summoned before the “Superintendent” of Fife, Fothriff, and Strathearn to answer the charge that he had taken it upon himself “to prech and minister the sacramentis wythowtyn lawfull admission, and for drawing of the pepill to the chapel of Tulebarne fra thar parroche kyrk”. Fergy did not obey the summons and so it was decided that he should be summoned for a second admonition. It is not known whether Fergy compeared on that occasion, nor what kind of punishment he might have received for his defiance. We are also in the dark as to the laird of Tullibardine’s views on the situation, even though it was going on right under his family’s nose. Nonetheless the case does provide a glimpse into what must have been a complex religious situation in sixteenth century Perthshire, no less for the ordinary parishioner than for the nobility. It also raises the possibility that private worship continued in the chapel after the Reformation, albeit unofficially.

Even as Tullibardine chapel’s public role diminished, the castle was still of some importance. Royal visits must have been considerably rarer after James VI succeeded to the English throne in 1603, and the Murrays of Tullibardine themselves acquired greater titles and estates, but the tower at Tullibardine still witnessed some notable events. During the first half of the eighteenth century, the castle was the home of Lord George Murray, a kinsman of the Duke of Atholl and famous for his participation in the Jacobite Risings of 1715, 1719, and 1745. During the last of these, Tullibardine Castle played host to a Jacobite garrison and was visited by Charles Edward Stuart. In less warlike times, Lord Murray often resided with his family at Tullibardine, and one of his daughters, who sadly died in infancy, seems to have been buried in the chapel. Lord George himself expressed a wish to be buried there as well but he was forced to flee into exile on the continent after the failure of the ’45, and so his body was interred “over the water” at Medemblick, in the Netherlands.

After Lord George’s exile Tullibardine castle entered a period of slow decline. Much of the fabric of the building was removed in 1747. Some years earlier plans had been made for the old tower to be replaced by a fashionable new house designed by William Adam, but these never materialised. A sketch of the mediaeval chapel made in 1789 shows the castle in the background- a roofless, tumbledown ruin. Tullibardine castle was finally demolished in 1833, and the family chapel, whose very existence had for centuries been defined by its proximity to the laird’s house, now stands alone. We are thus all the more fortunate for its survival, and both its attractive situation and interesting mediaeval features make Tullibardine chapel well worth a visit.

(Tullibardine Chapel, with the castle ruins in the background, as sketched in 1789. Reproduced with permission of the National Libraries of Scotland, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License)

Sources and notes may be found under the ‘read more’ button.

* “zeit” is presumaby “yett”, the old Scots word for gate.

Selected Bibliography:

- “Account of All the Religious Houses That Were in Scotland at the Time of the Reformation”, by John Spottiswood, in “An Historical Catalogue of the Scottish Bishops Down to the Year 1688″, by Reverend Robert Keith.

- Seventh Report of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, Part 2 (Duke of Atholl papers)

- “Register of the Ministers, Elders, and Deacons of the Congregation of St Andrews”, volume 4, Part 1 (St Andrews Kirk Session Register), edited by David Hay Fleming

- “Statement of Significance: Tullibardine Chapel”, Historic Environment Scotland

- “The Historie and Croniclis of Scotland From the Slauchter of King James the First to the Ane Thousande Five Hundreith Thrie Scoir Fiftein Zeir”, by Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie, volume 1 edited Aeneas J. G. Mackay.

- “Late Gothic Architecture in Scotland: Considerations on the Influence of the Low Countries”, by Richard Fawcett in ‘Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland’, 112 (1982)

- “Aspects of Timber in Renaissance and Post-Renaissance Scotland: The Case of Stirling Palace”, Thorsten Hanke

- “Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland”, Vol. 5, ed. M. Livingstone

- “The Household and Court of King James VI”, Amy L. Juhala

- “Memoirs of the Affairs of Scotland”, by David Moysie, ed. James Dennistoun for the Bannatyne Club

- “Calendar of State Papers, Scotland”, Volume 10, 1589-93, ed. William K. Boyd and Henry W. Meikle

- “The Indictment of Mary Queen of Scots, as Derived from a Manuscript in the University Library at Cambridge, Hitherto Unpublished”, by George Buchanan, edited by R.H. Mahon

#Scottish history#Scotland#British history#Perthshire#Places to go#Strathearn#Tullibardine Chapel#Tullibardine#Auchterarder#fifteenth century#sixteenth century#eighteenth century#1450s#1500s#building#architecture#Gothic Architecture#kirk and people#religion#Church#Christianity#private chapel#chapel#Murray family#Murrays of Tullibardine#Murray#Duke of Atholl#Jacobites#James VI#Mary Queen of Scots

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝒫𝓇𝒾𝓃𝒸𝑒 𝑅𝒾𝒸𝒽𝒶𝓇𝒹

♕ 𝐹𝓊𝓁𝓁 𝒩𝒶𝓂𝑒: Richard Alexander Walter George

♕ 𝐹𝓊𝓁𝓁 𝒯𝒾𝓉𝓁𝑒: His Royal Highness Prince Richard Alexander Walter George The Duke of Gloucester

♕ 𝐵𝓸𝓇𝓃: Saturday, August 26th, 1944 at St. Matthew's Nursing Home in Northampton, England

♕ 𝒫𝒶𝓇𝑒𝓃𝓉𝓈: His Royal Highness Prince Henry The Duke of Gloucester (Father) & Her Royal Highness Princess Alice Duchess of Gloucester (Mother)

♕ 𝒮𝒾𝒷𝓁𝒾𝓃𝑔𝓈: His Royal Highness Prince William of Gloucester (Brother)

♕ 𝒮���𝓸𝓊𝓈𝑒: Her Royal Highness Birgitte The Duchess of Gloucester (M. 1972)

♕ 𝒞𝒽𝒾𝓁𝒹𝓇𝑒𝓃: Major Alexander Earl of Ulster (Son), Lady Davina (neé Windsor) Lewis (Daughter), & Lady Rose (neé Windsor) Gilman (Daughter)

♕ 𝐸𝒹𝓊𝒸𝒶𝓉𝒾𝓸𝓃: Barnwell Manor (In Northamptonshire, England), Wellesley House School (In Kent, England), Eton College (In Berkshire, England), & Magdalene College at the University of Cambridge (In Cambridge, United Kingdom: Studied Architecture, Bachelor & Master of Arts Degrees in Architecture)

♕ 𝐼𝓃𝓉𝑒𝓇𝑒𝓈𝓉𝓈 𝒶𝓃𝒹 𝒲𝓸𝓇𝓀: Interests: Armed Forces (Air Force, Architecture, Court System, Defense, Disabled, Fallen Soldiers, Heraldry, & Security), Education, Food (Wine Trade), Health (Blindness, Cancer, Historic Sites, Hospitals, Leprosy, Medicine, & Support Animals), Nature (Agriculture, Conservation, Forests, Horticulture, Land Management, Soil, & Wildlife), People (Disabled, Elderly, Homelessness, Religious, & Trade), Science (Anthropology, Archeology, Art History, Engineering, Technology, & Transportation (Cars, Trains, & Trams)), Sports (Golf & Rowing), & The Arts (Architecture, Metal Work, Music, Shoe-Making, Stonemasonry, & Theatre). Work: Chancellor of The University of Worcester, Commissioner of the Historic Building & Monuments Commission for England, Co-Patron of Abbotsford Trust Appeal, Corporate Member of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Fellow of The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts/Manufactures/Commerce, Founding Chancellor of The University of Worcester, Freeman of The City of London, Freeman/Liveryman of The Worshipful Company of Masons, Honorary Fellow of The Institution of Civil Engineers, Honorary Fellow of The Institute of Clerks of Works and Construction Inspectorate, Honorary Fellow of The Institution of Structural Engineers, Honorary Fellow of The Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland, Honorary Freeman of The City of Gloucester, Honorary Freeman/Liveryman of The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, Honorary Freeman/Liveryman of The Worshipful Company of Vintners, Honorary Freeman of The Worshipful Company of Grocers, Honorary Life Member of The Bath Industrial Heritage Trust Ltd, Honorary Life Member of The Farmers Club, Honorary Life Member of The Friends of All Saints Brixworth, Honorary Life Member of The Royal Army Service Corps & Royal Corps of Transport Association, Honorary Member of The Architecture Club, Honorary Member of The Friends of Hyde Park & Kensington Gardens, Honorary Member of The Oxford & Cambridge Club, Honorary Member of The Petal Childhood Cancer Research, Honorary Member of The Reform Club, Honorary Membership of The Ecclesbourne Valley Railway Association, Honorary President of The The 20-Ghost Club Limited, Honorary President of The BR Class 8 Steam Locomotive Trust, Honorary President of The Somme Association, International Advisory Board Member of The Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, Joint President of Cancer Research UK, Member of The International Advisory Board for The Royal United Services Institute, Member of The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, Member of The Scottish Railway Preservation Society, Member of The St George's Chapel Advisory Committee, Patron of Action on Smoking & Health, Patron of Canine Partners for Independence, Patron of English Heritage, Patron of Flag Fen, Patron of St Bartholomew's Hospital, Patron of The Architects Benevolent Society, Patron of The Black Country Living Museum, Patron of The British Association of Friends of Museums, Patron of The British Homeopathic Association, Patron of The The British Korean Veterans Association, Patron of The British Limbless Ex-Service Men's Association, Patron of The British Mexican Society, Patron of The British Society of Soil Science, Patron of The Built Environment Trust, Patron of The Built Environment Education Trust (SHAPE), Patron of The Church Monuments Society, Patron of The Cresset (Peterborough) Ltd, Patron of The Construction Youth Trust, Patron of The De Havilland Aircraft Museum, Patron of The Essex Field Club, Patron of The Forest Education Initiative & Forest Education Network, Patron of The Fortress Study Group, Patron of The Fotheringhay Church Appeal, Patron of The Friends of Gibraltar Heritage Society, Patron of The Friends of Gloucester Cathedral, Patron of The Friends of Peterborough Cathedral, Patron of The Friends of St. Bartholomew the Less, Patron of The Gilbert & Sullivan Society, Patron of The Gloucestershire Millennium Celebrations, Patron of The Grange Centre for People with Disabilities, Patron of The Guild of the Royal Hospital of St Bartholomew, Patron of The Heritage of London Trust, Patron of The International Council on Monuments & Sites, Patron of The Isle of Man Victorian Society, Patron of The Japan Society, Patron of The Kensington Society, Patron of The Learning in Harmony Project, Patron of The Leicester Cathedral's King Richard III Appeal, Patron of The London Chorus, Patron of The London Playing Fields Foundation, Patron of The Magdalene Australia Society, Patron of The Mavisbank Trust, Patron of The Middlesex Association for the Blind, Patron of The Norfolk Record Society, Patron of The North of England Civic Trust, Patron of The Northamptonshire Archaeological Society, Patron of The Newcomen Society, Patron of The Nuffield Farming Scholarships Trust, Patron of The Oriental Ceramic Society, Patron of The Oundle Town Rowing Club, Patron of The Peel Institute, Patron of The Pestalozzi International Village Trust, Patron of The Richard III Society, Patron of The Royal Academy Schools, Patron of The Royal Air Force 501 (County of Gloucester) Squadron Association, Patron of The Royal Anglian Regiment Association, Patron of The Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Patron of The Royal Blind (Services for the Blind and Scottish War Blinded), Patron of The Royal Epping Forest Golf Club, Patron of The Royal Royal Pioneer Corps Association, Patron of The Scottish Society of Architect Artists, Patron of The Severn Valley Railway, Patron of The Society of Antiquaries of London, Patron of The Society of the Friends of St Magnus Cathedral Association, Patron of The Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, Patron of The St George's Society of New York, Patron of The Three Choirs Festival Association, Patron of The Tramway Museum Society, Patron of The United Kingdom Trust for Nature Conservation in Nepal, Patron of The Victorian Society, Patron of The Westminster Society, Patron of The Worshipful Company of Pattenmakers, Patron-In-Chief of The Scottish Veterans' Residences, Patron-In-Chief of The Friends of St Clement Danes, Practicing Partner at Hunt Thompson Associates Architectural Firm, President of Ambition, President of British Expertise International, President of Christ's Hospital, President of The Britain-Nepal Society, President of The Cambridge House, President of The Crown Agents Foundation, President of The Greenwich Foundation, President of The Institute of Advanced Motorists, President of The London Society, President of The Lutyens Trust, President of The Peterborough Cathedral Development and Preservation Trust, President of The Public Monuments and Sculpture Association, President of The Royal Agricultural Benevolent Institution, President of The Society of Architect Artists, President of St Bartholomew's Hospital, Ranger for The Epping Forest Centenary Trust, Royal Bencher for The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, Royal Patron of Bede's World Museum, Royal Patron of Habitat for Humanity (UK Branch), Royal Patron of The 82045 Steam Locomotive Trust, Royal Patron of The British Museum, Royal Patron of The Global Heritage Fund UK, Royal Patron of The Global Heritage Fund UK, Royal Patron of The Lilongwe Wildlife Trust, Royal Patron of The Nene Valley Railway, Royal Patron of The Peace and Prosperity Trust, Royal Patron of The Royal Auxiliary Air Force Foundation, Royal Patron of The Strawberry Hill Trust, Royal Patron of The Wells Cathedral - Vicars' Close Appeal, Senior Fellow of The Royal College of Art, The Duke of Gloucester Young Achiever's Scheme Awards, The Offices Development Group for the Ministry of Works, Vice Royal Patron of The Almshouse Association, Vice Patron of The National Churches Trust, Vice President of LEPRA, Vice President of The Royal Bath and West of England Society, Vice President of The Royal Cornwall Agricultural Association, Vice President of The Royal Smithfield Club, & Visitor of The Royal School Dungannon

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am a full time researcher and field investigator. My focuses are history, ethnography, forensic anthropology, Cryptozoology, and parapsychology (including ‘survival studies’). With over 40 years of experience I’m honored to be a Fellow of The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, a member of the Oxford University History Society, and the Association of Cryptozoological Fieldwork and Analysis. I am a Clansman of Andrew Francis Stewart of Appin and Ardsheal and a scholar of the West Highlands and Islands of Scotland, 1600 to 1900. A speaker of Scots Gaelic and Russian, and a former Private Military Contractor, I enjoy interacting with contacts the world over.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Scottish archaeologist and scholar Daniel Wilson was born on January 5th 1816 in Edinburgh.

Wilson attended Edinburgh High School before being apprenticed to a steel engraver. Between 1837 and 1842 he worked in London as an engraver and popular writer, but returned to Edinburgh to run an artist’s supplies and print shop.

Although Wilson developed an interest in history and matters antiquarian from a relatively early age, it was not until he was invited to help turn the collections of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland into a modern national museum that he turned from antiquarianism to archaeology. In reorganising the collection he adopted the Danish model of ordering the artefacts according to the Three Age System, it is due to his work we have The National Museum of Scotland, as we know it today.

He wrote Memorials of Edinburgh in the Olden Time in the 1840s, a book I have perused online many times, scouring for information for many posts over the years.

Wilson’s arrangement presented an evolutionary approach to viewing the artefacts, and this also came across in the catalogue that he wrote to go with the exhibition. Later, in 1851, he published an extended version of the catalogue as Archaeology and prehistoric annals of Scotland, his was the first comprehensive treatment of early Scotland based on material culture and the first time that the term ‘prehistoric’ was used in English, so he basically invented the word!!

Although Wilson received an honorary degree from the University of St Andrews, he was unable to get an academic position in Scotland. In 1853, with help from friends in Edinburgh, he was appointed to the Chair of History and English Literature in University College, Toronto, Canada. Wilson enjoyed teaching in Canada and continued his interest in archaeology, but all the while expanded his interest in anthropology and ethnography. Throughout his life he was a talented landscape painter, having worked with J. M. W. Turner studio during his time in London.

In 1888 Wilson was knighted for his services to education in Canada, and in 1891 given the freedom of the city of Edinburgh. He died in Toronto on August 6, 1892. The Sir Daniel J. Wilson Residence at the University College in University of Toronto is named in his honour.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

William Wallace Marker in Broxburn, Scotland Fifteen miles west of Edinburgh lies Almondell and Calderwood Country. Open all year around and free to visit, this spacious green wilderness area covers 220 acres of woodland and riverside walks. It is here that you will find not one, but two rather unusual carved rock slabs dating from the 18th century. The first is much easier to locate and can be found downstream from the Almondell Bridge on the southern end, following the "Red" walking route. After walking along the river and crossing over a wooden footbridge, you'll find a stone that reads: MARGARET COUNTESS OF BUCHAN DEDICATED THIS FOREST TO HER ANCESTOR SIR SIMON FRASER OCTOBER XV MDCCLXXXIV Sir Simon Fraser of Oliver and Neidpath fought alongside both Sir William Wallace and Robert the Bruce. The English captured him in June 1306. Suffering the same fate as Wallace, a year later Fraser was hung, drawn, and quartered. His head was impaled on a spike and displayed next to his comrades on London Bridge. Almondell and the surrounding environs were once in possession of David Stewart Erskine, the 11th Earl of Buchan, and his wife Margaret Fraser. Erskine, the founder of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, was enthralled with anything to do with the Scottish knight Sir William Wallace. So much so, he erected this memorial to his wife's descendant, as well as the Wallace Statue near Dryburgh. The second stone, also funded by Erskine, is located some distance away and can be found along the road leading out of the estate. Hidden among the underbrush, on the right-hand side of the road, a few yards from the Drumshoreland crossroads. This carved tablet may well be the earliest surviving memorial to Wallace in Scotland. The Latin inscription reads: M.S. GUL VALLAS OCTOB XV MDCCLXXXIV Basically translated: Sacred to the memory of William Wallace October 15, 1784. This is the same year carved into the previous stone. The placement of this stone indicates the area Wallace and his men would have patrolled, keeping an eye on King Edward II and his army, just before the Battle of Falkirk in July 1298. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/william-wallace-marker

0 notes

Text

The difference between Single Malt and Blended Scotch whisky

One of the big things that both long-serving, and newer whisky drinkers ask me is about the difference between Single Malt and Blended Scotch whisky so today I'm finally getting around to writing it up so there is a reference point for it on GreatDrams.

The whisky world is not created equal, and there are ironies within the industry that many whisky drinkers simply do not understand, especially around the difference between Single Malt and Blended Scotch whisky.

Blended Scotch whisky has been around for around 300 years, but has only been created commercially since 1840 thanks to the first Master Blender, Andrew Usher. Before this, whisky from single distilleries - single malt, of sorts - were so random and inconsistent in flavour that trying to sell them was nigh on impossible because, in no small part, the flavour variance between batches was significant meaning that one batch of whisky from Distillery X may taste great this week, but next week it may be like fire water.

I'm telling you this because to understand the difference between Single Malt and Blended Scotch whisky properly, you should understand how the categories evolved.

So what is the difference between Single Malt and Blended Scotch whisky?

The two basic types of Scotch are:

Malt whisky which is made from 100% malted barley

Grain whisky which can be made from any grain (usually maize or wheat) but has to include a fraction of malted barley too

Malt whisky has to be distilled in pot stills, grain whisky is usually made in column stills.

Here's the crucial detail that defines the difference between Single Malt and Blended Scotch whisky:

Single Malt Scotch Whisky is also a blend, but it is a blend of malt whisky produced in just one distillery so in effect the word 'single' means 'single place of origin' whereas Blended Scotch Whisky is a blend of grain and malt whisky from multiple distilleries.

Some of the best examples Blended Scotch Whisky

Dewar's Chivas Regal Ballantine's Grant's Johnnie Walker Compass Box The Antiquary Cutty Sark The Famous Grouse Bell's Royal Salute

Some of the best examples Single Malt Scotch Whisky

Craigellachie Aberfeldy Laphroaig Lagavulin Aberlour The Macallan Glenrothes Glenfiddich Ardbeg Glengoyne Aultmore Smokehead

There are five whisky categories that you should be aware of:

Single malt whisky – malt whisky from a single distillery

Single grain whisky – grain whisky from a single distillery (unusual)

Blended malt whisky – a mixture of malt whiskies from different distilleries

Blended grain whisky – a mixture of grain whiskies from different distilleries (unusual)

Blended whisky - a mixture of malt and grain whisky, usually from different distilleries

The hierarchy of whisky bottling types

For some additional context around the difference between Single Malt and Blended Scotch whisky, let's talk about age, maturation and some production quirks

The requirement to mature whisky for three years minimum was not passed into law until the Immature Spirits Act of 1915, yet as we know whisky itself has been around for two or three hundred years. However, whisky in the eighteenth century was largely referred to as ‘fresh from the still’ as it was effectively new make or very young spirit.

The Immature Spirits Act came in to pacify the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lloyd George, who was a passionate anti-boozer who felt that the ills of alcohol were damaging the United Kingdom during World War One almost as much as the enemies they were fighting at the time. He did have a point; there is credible evidence to suggest that young, unmeasured spirit caused a lot of damage to individuals’ bodies, hence the term ‘blind drunk’, to the extent of making them unfit to help in the war effort. Lloyd George proposed an outright ban on alcohol during the war, a prohibition of sorts, but that was met with the obvious outcry you’d expect from a nation partial to a tipple or two.

Then stepped in a chap called James Stevenson, a whisky man who went on to become the chairman of Johnnie Walker but at the time served the war effort by overseeing the Ministry of Munitions. He pointed out that without alcohol production during the war, there would be no alcohol available to make high explosives or anaesthetic amongst other things. A deal was struck. The man had a point.

In one simple twist of legislative fate whisky went from being a menace to the British society of the time to being a thought-through, planned and quality product.

So essentially, if you boil it down, the three year minimum maturation period for whisky was enacted to slow supply in order that the government could stop drunk folk handling munitions during the First World War.

Whilst the romance of ‘bottled when ready’ is lovely, the reality is a lot more practical and rooted in political tussles, as so many things in today’s society are.

And why is this important? Because this is why Blended Scotch Whisky became so prominent at the time - Single Malt Scotch Whisky could not be trusted not to hurt those who drank it, whereas Blended Scotch Whisky was much more balanced, gradually turned heads away from cheap brandy and cognac - helped massively by the phylloxera parasite that swept through Central Europe decimating vineyards through the late 19th Century - and was easier to drink and to enjoy.

If you were alive in the 19th Century you would only have known about blends, single malt as a commercial product and category within the whisky market has only existed for a few decades.

William Grant & Sons are credited as one of the companies behind this market innovation when they released Glenfiddich as a brand in 1963 and product to sell through surplus stock instead of simply being a component in their volume product of Grant’s Family Reserve (known as Stand Fast back then).

The big irony here is that Grant’s released Glenfiddich they ran with a campaign titled “You may never stand for a Blended Scotch again” thus ensuring that consumers saw Single Malt as superior to Blended Scotch Whisky.

While we are here, let's have a quick word on age in whisky

By law, to be allowed to be called Scotch Whisky it has to be matured in Scotland in oak casks for at least 3 years

Bottled whisky may be a mixture of casks of any age over 3 years

Bottles do not have to have an age statement, but if there is one, the age on the label must be the age of the youngest whisky in the mix in completed years

A whisky aged 3 years and 364 days is legally still 3 years old

Blended Scotch Whisky and Single Malt Scotch Whisky is commonly bottled at ages from 10 to 21 years, but there are also younger and much older ages. The current record holders are bottled at an age of 75 years from a G&M release of a Mortlach single cask.

One final bit of knowledge any budding whisky drinker should know about is around maturation

Most casks have previously held American bourbon, but also sherry casks from Spain are common. To a lesser extent other cask types like port, madeira, rum or wine are used as well. Most whisky casks are re-used several times by distilleries.

Maturation takes place in warehouses. The traditional dunnage warehouses have stone walls and an earth floor which is believed to create perfect conditions for maturation. But there are also modern racked warehouses with concrete floor and steel walls where casks can be handled by forklifts.

During maturation, the clear new spirit extracts flavouring and colouring substances from the cask that are both from the wood and the remains of the previous cask filling. Because the casks are not totally airtight some of the spirit evaporates during maturation.

This is called the angels’ share, depending on the climate and the location of the cask in the warehouse this loss is typically between 1% and 2% per year.

There you have it, a full guide to the difference between Single Malt and Blended Scotch whisky as well as a load of context to put into perspective why the two spirits exist and the various quirks around their production and legalities.

The post The difference between Single Malt and Blended Scotch whisky appeared first on GreatDrams.

from GreatDrams https://ift.tt/2Oiz9kO Greg

5 notes

·

View notes