#Tullibardine Chapel

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Places to Go: Tullibardine Chapel

A small kirk sheltered by Scots pines, Tullibardine Chapel has an air of tranquility and simple elegance. Formerly the private chapel of the Murrays of Tullibardine, it is one of the few buildings of its kind in Scotland to have survived with many of its medieval details intact.

The Murrays acquired the lands of Tullibardine in the late thirteenth century, when William ‘de Moravia’ married a daughter of the steward of Strathearn. Later, through judicious marriages and court connections, they first became earls of Tullibardine and then Dukes of Atholl. But even as lairds the Murrays were a significant power in late mediaeval Perthshire. In those days Tullibardine Castle was one of their main strongholds, and the close proximity of royal residences like Stirling meant that the Castle also hosted several notable guests. Mary, Queen of Scots, stayed there in December of 1566 (allegedly in the company of the earl of Bothwell). One laird of Tullibardine became Master of Household to the young James VI, while his aunt Annabella Murray, Countess of Mar, oversaw the king’s upbringing. Thus James VI was also a frequent visitor and it was he who created the earldom of Tullibardine in 1606. The king is known to have attended the wedding of the laird of Tullibardine’s daughter Lilias Murray, though it is unclear whether this took place at Tullibardine itself. The castle grounds were probably an impressive sight too: the sixteenth century writer Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie claimed that a group of hawthorns at the “zeit of Tilliebairne”* had been planted in the shape of the Great Michael by some of the wrights who worked on the famous ship.

Thus the tower at Tullibardine, though presumably on a small-scale, was apparently comfortable and imposing enough for the lairds to host royalty and fashion an impressive self-image. But the spiritual needs of a late mediaeval noble family were just as important as their political prestige, and a chapel could both shape the family’s public image and secure their private wellbeing. The current chapel at Tullibardine, which originally stood at a small distance from the castle, was allegedly founded by David Murray in 1446, “in honour of our blessed Saviour”. At least this was the story according to the eighteenth century writer John Spottiswoode, and his assertion is partly supported by the chapel’s internal evidence, though no surviving contemporary document explicitly confirms the tale. A chapel certainly existed by 1455, when a charter in favour of David’s son William Murray of Tullibardine mentions it as an existing structure. In this charter, King James II stated that his “familiar shieldbearer” William Murray has “intended to endow and infeft certain chaplains in the chapel of Tullibardine”. Since the earls of Strathearn had previously endowed a chaplain in the kirk of Muthill, but duties pertaining to the chaplaincy had not been undertaken for some time, James transferred the chaplaincy to Tullibardine. He also granted his patronage and gift of the chaplaincy to William Murray and his heirs.

The charter indicates that Tullibardine Chapel was an important project for the Murrays. Interestingly though, no official references to the chapel in the fifteenth, sixteenth, or seventeenth centuries describe Tullibardine chapel as a collegiate church, even though later writers have frequently claimed this. Collegiate foundations were increasingly popular with the Scottish nobility during the late Middle Ages, but, although such a foundation might have been planned for Tullibardine, there is no evidence that this ever took place.

The 1455 charter serves as an early indication of the chapel’s purpose and significance. Judging by its architecture the current chapel does appear to have been constructed in the mid-fifteenth century. However it was also substantially remodelled and enlarged around 1500, when the western tower was added. One remnant of the original design is the late Gothic ‘uncusped’ loop tracery on the windows. Despite the apparent simplicity of the chapel, features such as this window tracery have been taken as evidence that its builder was acutely aware of contemporary European architectural fashions. Another interesting feature is the survival of the chapel’s original timber collarbeam roof, a rare thing in Scotland. Several coats of arms belonging to members of the Murray family adorn the walls and roof corbels, although some of these armorial panels were probably moved when the chapel was reconstructed. They include the arms of the chapel’s alleged founder David Murray and his wife Margaret Colquhoun, as well as those of his parents, another David Murray and Isabel Stewart. A later member of the family, Andrew Murray, married a lady named Margaret Barclay c.1499, around the same time that the chapel was renovated, and although they were buried elsewhere, their coats of arms can also be seen there. Aside from such details- carved in stone and thus less perishable than books and vestments- the chapel’s interior seems quite sparse and bare today. Originally though the mediaeval building probably housed several richly furnished altars and some of the piscinas (hand-washing stations for priests) can still be seen in the walls. But the sumptuous display favoured in even the smallest mediaeval chapels was soon to be swept away entirely by the Reformation of 1560, when Scotland broke with the Catholic Church and Protestantism became the established faith of the realm.

Tullibardine was used chiefly as a private burial place after the Reformation, but there are signs that the transition from one faith to another was not entirely smooth. Four years after the “official” Reformation, a priest named Sir Patrick Fergy was summoned before the “Superintendent” of Fife, Fothriff, and Strathearn to answer the charge that he had taken it upon himself “to prech and minister the sacramentis wythowtyn lawfull admission, and for drawing of the pepill to the chapel of Tulebarne fra thar parroche kyrk”. Fergy did not obey the summons and so it was decided that he should be summoned for a second admonition. It is not known whether Fergy compeared on that occasion, nor what kind of punishment he might have received for his defiance. We are also in the dark as to the laird of Tullibardine’s views on the situation, even though it was going on right under his family’s nose. Nonetheless the case does provide a glimpse into what must have been a complex religious situation in sixteenth century Perthshire, no less for the ordinary parishioner than for the nobility. It also raises the possibility that private worship continued in the chapel after the Reformation, albeit unofficially.

Even as Tullibardine chapel’s public role diminished, the castle was still of some importance. Royal visits must have been considerably rarer after James VI succeeded to the English throne in 1603, and the Murrays of Tullibardine themselves acquired greater titles and estates, but the tower at Tullibardine still witnessed some notable events. During the first half of the eighteenth century, the castle was the home of Lord George Murray, a kinsman of the Duke of Atholl and famous for his participation in the Jacobite Risings of 1715, 1719, and 1745. During the last of these, Tullibardine Castle played host to a Jacobite garrison and was visited by Charles Edward Stuart. In less warlike times, Lord Murray often resided with his family at Tullibardine, and one of his daughters, who sadly died in infancy, seems to have been buried in the chapel. Lord George himself expressed a wish to be buried there as well but he was forced to flee into exile on the continent after the failure of the ’45, and so his body was interred “over the water” at Medemblick, in the Netherlands.

After Lord George’s exile Tullibardine castle entered a period of slow decline. Much of the fabric of the building was removed in 1747. Some years earlier plans had been made for the old tower to be replaced by a fashionable new house designed by William Adam, but these never materialised. A sketch of the mediaeval chapel made in 1789 shows the castle in the background- a roofless, tumbledown ruin. Tullibardine castle was finally demolished in 1833, and the family chapel, whose very existence had for centuries been defined by its proximity to the laird’s house, now stands alone. We are thus all the more fortunate for its survival, and both its attractive situation and interesting mediaeval features make Tullibardine chapel well worth a visit.

(Tullibardine Chapel, with the castle ruins in the background, as sketched in 1789. Reproduced with permission of the National Libraries of Scotland, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License)

Sources and notes may be found under the ‘read more’ button.

* “zeit” is presumaby “yett”, the old Scots word for gate.

Selected Bibliography:

- “Account of All the Religious Houses That Were in Scotland at the Time of the Reformation”, by John Spottiswood, in “An Historical Catalogue of the Scottish Bishops Down to the Year 1688″, by Reverend Robert Keith.

- Seventh Report of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, Part 2 (Duke of Atholl papers)

- “Register of the Ministers, Elders, and Deacons of the Congregation of St Andrews”, volume 4, Part 1 (St Andrews Kirk Session Register), edited by David Hay Fleming

- “Statement of Significance: Tullibardine Chapel”, Historic Environment Scotland

- “The Historie and Croniclis of Scotland From the Slauchter of King James the First to the Ane Thousande Five Hundreith Thrie Scoir Fiftein Zeir”, by Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie, volume 1 edited Aeneas J. G. Mackay.

- “Late Gothic Architecture in Scotland: Considerations on the Influence of the Low Countries”, by Richard Fawcett in ‘Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland’, 112 (1982)

- “Aspects of Timber in Renaissance and Post-Renaissance Scotland: The Case of Stirling Palace”, Thorsten Hanke

- “Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland”, Vol. 5, ed. M. Livingstone

- “The Household and Court of King James VI”, Amy L. Juhala

- “Memoirs of the Affairs of Scotland”, by David Moysie, ed. James Dennistoun for the Bannatyne Club

- “Calendar of State Papers, Scotland”, Volume 10, 1589-93, ed. William K. Boyd and Henry W. Meikle

- “The Indictment of Mary Queen of Scots, as Derived from a Manuscript in the University Library at Cambridge, Hitherto Unpublished”, by George Buchanan, edited by R.H. Mahon

#Scottish history#Scotland#British history#Perthshire#Places to go#Strathearn#Tullibardine Chapel#Tullibardine#Auchterarder#fifteenth century#sixteenth century#eighteenth century#1450s#1500s#building#architecture#Gothic Architecture#kirk and people#religion#Church#Christianity#private chapel#chapel#Murray family#Murrays of Tullibardine#Murray#Duke of Atholl#Jacobites#James VI#Mary Queen of Scots

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Scotland—Tullibardine Chapel

[x, x, x, x, x, x, x]

0 notes

Photo

On July 14th 1927 The Scottish National War Memorial opened.

As this post regards the Memorial that was to become part of Edinburgh Castle, there is a wee bit history of the castle itself in this post. I recall putting a post together last year on it’s centenary, but keeping it short as there ahd been many articles in the newspapers and online about it, this year with have devoted more time putting together this long post.

The National War Memorial for Scotland was established by Royal Charter to commemorate the sacrifice of Scots in the Great War, Second World War and subsequent conflicts. The Memorial within Edinburgh Castle houses and displays the Rolls of Honour of Scots servicemen and women from all the Armed Services, the Dominions, Merchant Navy, Women’s Services, Nursing Services and civilian casualties of all wars from 1914 to date.

In 1927 the architect Sir Robert Lorimer and 200 Scottish artists and craftsmen created a serene Hall of Honour and Shrine, where the names of the dead are contained in books that are on permanent display.

A number of eminent Scots wanted a truly Scottish memorial, in Scotland, recording the names of all Scots and displaying Scottish material. The moving force behind this vision was John George 8th Duke of Atholl. A leading member of the Scottish aristocracy, the Duke of Atholl, or “Bardie” as he was known from his title, the Marquis of Tullibardine, was a serving soldier who had fought in the Sudan and had raised the Scottish Horse Yeomanry. He was a man of considerable vision and energy and, what was more important, he had both influence and connections.

In the spring of 1917 Atholl gathered around him a number of leading and powerful Scots. Atholl lost no time in promoting the Scottish case for a memorial. He wrote to the Commissioner of Works asking that Scotland should have her own memorial in the form of a museum collection to be housed in Edinburgh Castle. There then followed widespread consultation, which included the five Lord Provosts of the Cities of Scotland and extensive press coverage, largely in The Scotsman newspaper.

Initially there was concern on the part of the City of Glasgow and it was important that the City Fathers of Scotland’s largest urban centre agree to the scheme. The problem was solved when Spencer Ewart hosted a dinner for all of the interested parties and agreement was obtained.

The choice of Edinburgh Castle was inspirational, historically interesting and sensitive.

The Castle stands high above the centre of the capital city of Scotland dominating the skyline for miles around. Even in 1914 the Castle was a major tourist attraction and its roots lay deep in the folklore and traditions of Scottish history.

Until 1914 it had been the main barracks for the Infantry garrison of Edinburgh and soldiers had lived there and guarded its walls for many centuries.

The standard of military accommodation within the Castle precincts was however very basic. The barrack rooms were crowded and draughty with leaky roofs. The accommodation was heated by small coal burning fires in open grates some of which were still used for cooking. There were only a few baths for the whole of the garrison, no running hot water and very basic toilet facilities. The one communal cookhouse meant that most of the men still ate in their barrack rooms.

As a result of these shortcomings a new barracks was built at Redford on the outskirts of the City which would house both infantry and cavalry units. These barracks were being built in 1914 just before the outbreak of war. It was therefore envisaged that when the war ended there would be vacant accommodation within the Castle walls which could be adapted for the Memorial plan.

In addition, the concept of a military museum was a very new idea which would not compete with existing regimental museums for there were none. The Scottish regiments were more likely to agree to a central location such as the Castle where they had all served at one time or another. By this time the individual regiments had acquired many regimental trophies and together with much of the silver, artefacts and archives these were usually deposited with the Regimental Depots and were not on display to the public. Thus the opportunity to show the regimental histories and traditions was welcomed.

The choice of Edinburgh Castle was however a sensitive one. Any proposal to alter the distinctive Edinburgh skyline by the building or demolition of any part of the existing structures was bound to meet with considerable opposition. This opposition was both vociferous and powerful and was in time to change the plan significantly.

In October 1918, a Scottish National War Memorial Committee was appointed by the Secretary of State for Scotland, “to consider what steps should be taken towards the utilization of Edinburgh Castle for the purposes of a Scottish National War Memorial”. Great care had been taken with these appointments to ensure that the Services, the press, the church, learning, architecture, Scottish history, the cities and the political parties were all represented.

The architect Robert Lorimer designed the stunningly beautiful Chapel for the Knights of the Thistle in St Giles Cathedral, but advised against a church or chapel as it “would excite much opposition”. It was estimated that the Memorial Shrine and Cloisters and the museum he proposed would cost a staggering £250,000.

While the money was a problem, there were many others that I won’t go into in depth, needless to say, some were ploitical, others were fro, The Cockburn Society, who still do a great job to this day, trying to safeguard Edinburgh’s heritage, to just give an example of the anger some people had for the scheme, the leading critics were Sir Richard Lodge, Professor of History at Edinburgh University, Principal Laurie at Heriot-Watt College and Lady Francis Balfour who actually demanded that the Duke of Atholl and Sir Robert Lorimer should be hanged!!!!!

Such was some of the opposition that there were even proposals to abandon the whole scheme in the Castle altogether and to erect a memorial on Calton Hill or Princess Street Gardens.

Undaunted they began fundraising. However this too had its problems as the Memorial appeal coincided with large appeals being made by Edinburgh Infirmary and Edinburgh University and the many small appeals for Parish memorials, most of these that you see in our towns and villages were paid for by public subscription.

Lorimer did make substantial compromises to his plan. He suggested that Billing’s Buildings should be retained and adapted to form a Memorial Gallery. On the North side he proposed a deep apse, the roof of this extension being no higher than the existing height of Billing’s Buildings, protecting our famous skyline.

Finally, in April 1923 the opposition crumbled. The Ancient Monuments Board gave a favourable report on the changes, the War Office gave final and unqualified consent and, in October of that year, the Government approved Lorimer’s designs. Six years after Atholl had made his original proposals the project went to tender and work began.

Robert Lorimer paid regular weekend visits to Blair Castle to discuss the fine detail and how every regiment, service and corps should be remembered, including the animals who in their own way had served and suffered in the war.

Some of the finest Scottish craftsmen and women of the day committed many hours to ensuring that every detail was correct. The windows had to lend a soft and subtle colour to the interior, but there had to be sufficient light to ensure that the names in the Books of Remembrance could be read.

The frieze in the Shrine, the work of Mrs Gertrude Alice Meredith Williams, was deemed by all to be a masterpiece and the Duke of Atholl was particularly delighted with it. Referring to “Mrs Meredith Williams’ wonderful frieze”, the Duchess of Atholl recorded, “ The beauty of the frieze is in part due to her husband. During his three years in the ranks in France he made endless drawings of his fellow soldiers. The drawings furnished a priceless inspiration for the amazing number of men and women recorded in his wife’s masterpiece”.

It is clear from the records that both the Duke and the Duchess of Atholl played a major part in influencing the interior design of the building, particularly in relation to the subtle symbolism and the wonderful serenity and simplicity.

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

May of next year, our #PodAbroad2018 guests will visit Tullibardine Chapel. Near Auchterarder, Perth and Kinross, this location was used to film the scenes in the church where Claire, Jamie, and the others hide while Claire tends to Rupert's injured eye in Season 2's episode 11, "Vengeance is Mine." Historically, Tullibardine is also the name of the Atholl heir, the Marquess of Tullibardine, which takes its name, as does the chapel, from the nearby village of the same name. 🔸 One of the few Scottish churches to survive the Reformation of 1560 largely unaltered, the chapel was built in 1446 by David Murray of Tullibardine as a family chapel and burial site. 🔸 📷 Ginger Wiseman @bookishginge 🔸 Sources: stravaiging.com; historicenvironment.scot; outlander.wikia.com 🔸 For more information about our tour, visit 👉🏻 PodAbroad.com 👈🏻 (at Tullibardine Chapel)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

2x11 Vengeance Is Mine ~ Kirk Hideout

Tullibardine Chapel (Auchterarder, Scotland)

Look for Funko Claire & Jamie (click pics to enlarge)

#Outlander#Claire Fraser#Jamie Fraser#Outlander Locations#Tullibardine Chapel#Filming Locations#Vengeance Is Mine#2x11#Outlandish 2nd Honeymoon Trip#MORE TO COME#S4L

169 notes

·

View notes

Photo

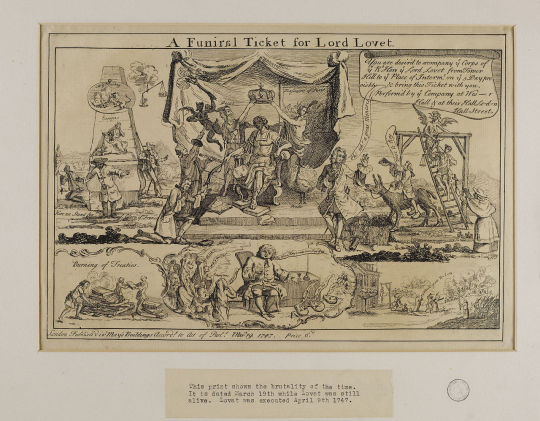

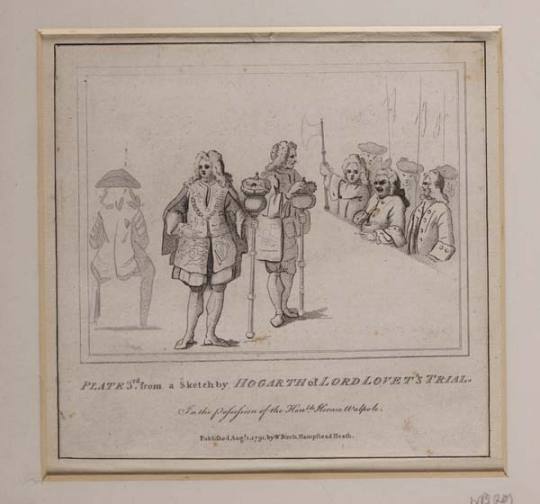

On 9th April 1747 leading Jacobite Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat was executed on Tower Hill London, the last execution by beheading in the country.

The Clan Fraser patriarch was an expert double-dealer from his youth in Restoration England — when he recruited a small regiment in nominal service to William and Mary but allegedly plotting to desert to the Stuarts at the opportune moment, is it any wonder the 11th Lord Lovat got the nickname "The Fox" Some may see him as a Jacobite hero, but Simon Fraser was not a nice man, he kidnapped, raped, and forcibly married a woman from a rival clan in order to gain claim on a contested succession (Lovat had to flee the country, a death sentence in absentia at his heels). He forged incriminating documents in an unsuccessful bid to undermine rival nobles.

I think the nickname maybe should have been the cat, this is part of a speech by Lord Belhaven, delivered in the last Parliament held in Edinburgh, in 1706, .”....in which his lordship, speaking of this nobleman, then Captain Fraser, on occasion of the Scots plot, commonly called Fraser's plot, says that " he deserved, if practicable, to have been hanged five several times, in five different places, and upon five different accounts at least : as having been notoriously a traitor to the Court of St James's, a traitor to the Court of St Germain's, a traitor to the Court of Versailles and a traitor to his own country of Scotland; in being not only an avowed and restless enemy." Strong words indeed!

He played both sides of the Hanover-Stuart intrigue, ingratiating himself with both Jacobites and London during the 1715 uprising, more so than his contemporary, John Erskine, Earl of Mar, who also got an unenviable nickname "Bobbin John".

To be fair Lovatt as a soldier was well past it by the time the '45 came about, he was in his late 70's and riddled with gout, more important to Prince Charles army was the men he could command., it fell to his son to lead the clan in the uprising. This excerpt from "Memoirs of the Jacobites 1715 and 1745" tells it all.

He could neither walk nor ride, as he was almost helpless; he was deaf, purblind, eighty years of age, ignorant of English law, and it was therefore not a matter of surprise that the high-born tribes, who thronged to his trial, were disappointed in the brilliancy of his parts, and in the readiness of his wit. "I see little of parts in him,” observes Walpole It appeared, indeed, doubtful in what form death would seize him first, and whether disease and age might not cheat the scaffold of its victim.

He must have been a sore sight sitting in the dock, he had however not lost any of his faculties and defended himself at the trial, and in truth he took no real part in the Uprising, and in his defence he said he merely obeyed the Scots law of hospitality and gave shelter to the Prince.

The guilty verdict was a forgone conclusion though and so it was on April 9th, Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat in his 80th year was taken out for his execution, which originally was to be Hung, drawn and quartered but was computed to a mere beheading by the King.

As he was stepping into the carriage which would carry him to his death, an old woman shouted, 'You will have your head chopped off, you ugly old Scots dog.' Without a second's hesitation he turned upon her, and, raising his hat, replied, 'I verily believe I shall, you old English bitch.'

Large crowds gathered for the spectacle and it is said to have amused Lovatt when a grandstand erected for the benefit of spectators to the event suddenly collapsed, resulting in the death of 20 people As he was going up the steps to the scaffold, assisted by two warders, he looked round, and, seeing the crowds said, " God save us, why should there be such a bustle about taking off an old grey head, that cannot get up three steps without three bodies to support it ?

His gallows mirth is credited as the origin of the saying “laughing your head off” and maybe, I should add “Gallows Humour”?

Turning about, and observing one of his friends much dejected, he clapped him on the shoulder, saying: "Cheer up thy heart, man! I am not afraid; why should you be so? " As soon as he climbed onto the scaffold he asked for the executioner, and presented him with ten guineas in a purse, and then, desiring to see the axe, he felt the edge and said he " believed it would do." Soon after, he rose from the chair which was placed for him and looked at the inscription on his coffin, and on sitting down again he read

" Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. Nam genus et proavos, et qux non fecimus ipsi, Vix ea nostra voco."

Which translates to

" It is sweet and honorable to die for the fatherland For the race, ancestry, and the things that we have not had hardly call our own."

Lovatt told the executioner he would say a short prayer and then give the signal by dropping his handkerchief. In this posture he remained about half-a- minute, and then, on throwing his handkerchief on the floor, the executioner at one blow cut off his head, which was received in the cloth, and, with his body was put into the coffin and carried in a hearse back to the Tower, where it was interred near the bodies of the other lords.

Or was it? Speculation that Lovatts friends and family managed to spirit the body away to the Wardlaw Mausoleum in Kirkhill, where his ancestors lie, for centuries it is thought that a body, minus the head, in a lead casket inside was that of "The Old Fox" but 2018 the remains were inspected by a forensic scientist and were found to be that of a female. There are some who still cling to the belief that Lovatt is buried in the graveyard there somewhere, but you just can’t go about digging up graves in search of a 270 odd year body because of a “legend”

To me it looks like The Old Fox is within the walls of The Tower of London after all. Along with other notable Jacobites, William Murray, Marquess of Tullibardine William Boyd, 4th Earl of Kilmarnock and Arthur Elphinstone, 6th Lord Balmerino, they are all featured on a plaque in the Chapel of Saint Peter-ad-Vincula. London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

Another notable name on the plaque is Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, who was part of the Ridolfi plot, which would have saw him marry Mary Queen of Scots and become King of England, had it succeeded. Three English Queen’s also appear on the plaque.

One of my ports of call when researching history is the web page Find a Grave, people use it to go pay their respects to those named on the site, Lord Lovatt being one, there are dozens of tributes left throughout the years, including one already today. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/6852/lord-lovat

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

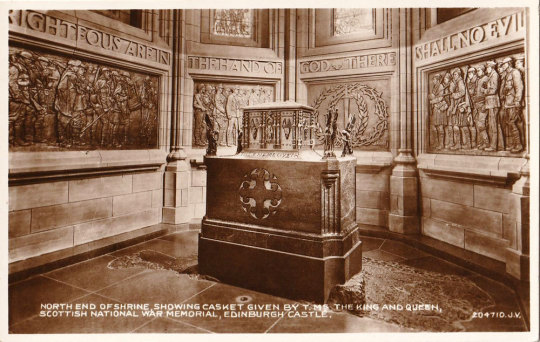

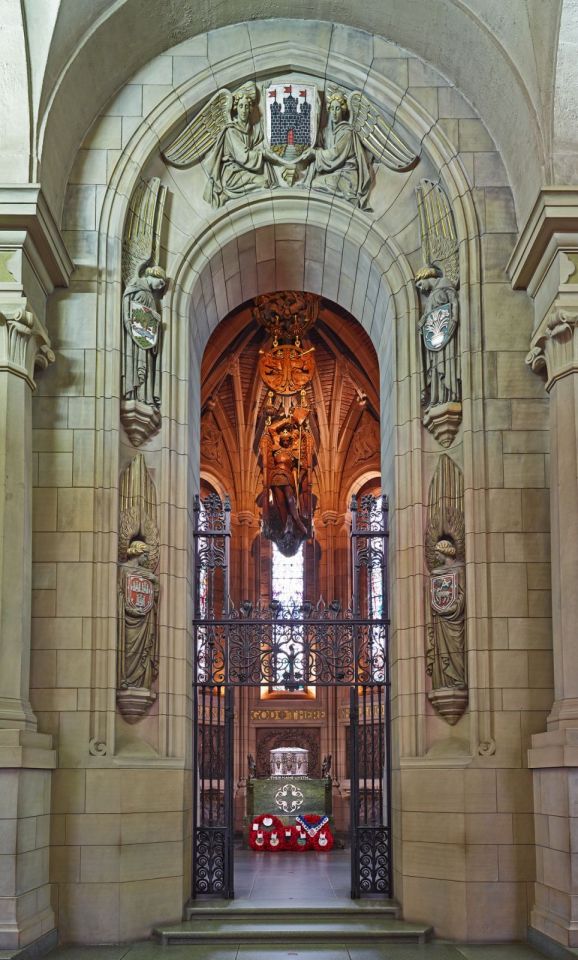

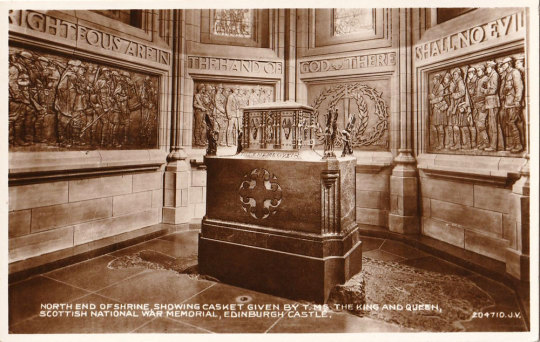

On July 14th 1927 The Scottish National War Memorial opened.

The National War Memorial for Scotland was established by Royal Charter to commemorate the sacrifice of Scots in the First World War since it's opening it has also covered subsequent conflicts.

The Memorial within Edinburgh Castle houses and displays the Rolls of Honour of Scots servicemen and women from all the Armed Services, the Dominions, Merchant Navy, Women's Services, Nursing Services and civilian casualties of all wars from 1914 to date.

In 1927 the architect Sir Robert Lorimer and 200 Scottish artists and craftsmen created a serene Hall of Honour and Shrine, where the names of the dead are contained in books that are on permanent display.

A number of eminent Scots wanted a truly Scottish memorial, in Scotland, recording the names of all Scots and displaying Scottish material. The moving force behind this vision was John George 8th Duke of Atholl. A leading member of the Scottish aristocracy, the Duke of Atholl, or "Bardie" as he was known from his title, the Marquis of Tullibardine, was a serving soldier who had fought in the Sudan and had raised the Scottish Horse Yeomanry. He was a man of considerable vision and energy and, what was more important, he had both influence and connections.

Atholl gathered around him a number of leading and powerful Scots and lost no time in promoting the Scottish case for a memorial. He wrote to the Commissioner of Works asking that Scotland should have her own memorial in the form of a museum collection to be housed in Edinburgh Castle. There then followed widespread consultation, which included the five Lord Provosts of the Cities of Scotland and extensive press coverage, largely in The Scotsman newspaper.

Initially there was concern on the part of the City of Glasgow and it was important that the City Fathers of Scotland's largest urban centre agree to the scheme. The problem was solved when a dinner for all of the interested parties was arranged and agreement was obtained.

The choice of Edinburgh Castle was inspirational, historically interesting and sensitive.

The Castle stands high above the centre of the capital city of Scotland dominating the skyline for miles around. Even in 1914 the Castle was a major tourist attraction and its roots lay deep in the folklore and traditions of Scottish history.

Until 1914 it had been the main barracks for the Infantry garrison of Edinburgh and soldiers had lived there and guarded its walls for many centuries.

The standard of military accommodation within the Castle precincts was however very basic. The barrack rooms were crowded and draughty with leaky roofs. The accommodation was heated by small coal burning fires in open grates some of which were still used for cooking. There were only a few baths for the whole of the garrison, no running hot water and very basic toilet facilities. The one communal cookhouse meant that most of the men still ate in their barrack rooms.

As a result of these shortcomings a new barracks was built at Redford on the outskirts of the City which would house both infantry and cavalry units. These barracks were being built in 1914 just before the outbreak of war. It was therefore envisaged that when the war ended there would be vacant accommodation within the Castle walls which could be adapted for the Memorial plan.

The choice of Edinburgh Castle was a sensitive one. Any proposal to alter the distinctive Edinburgh skyline by the building or demolition of any part of the existing structures was bound to meet with considerable opposition. This opposition was both vociferous and powerful and was in time to change the plan significantly.

In October 1918, a Scottish National War Memorial Committee was appointed "to consider what steps should be taken towards the utilisation of Edinburgh Castle for the purposes of a Scottish National War Memorial".

Great care had been taken with these appointments to ensure that the Services, the press, the church, learning, architecture, Scottish history, the cities and the political parties were all represented.

The architect Robert Lorimer designed the stunningly beautiful Chapel for the Knights of the Thistle in St Giles Cathedral, but advised against a church or chapel as it "would excite much opposition". It was estimated that the Memorial Shrine and Cloisters and the museum he proposed would cost £250,000 a staggering amount for that age.

While the money was a problem, there were many others that I won't go into in depth, needless to say, some were ploitical, others were fro, The Cockburn Society, who still do a great job to this day, trying to safeguard Edinburgh's heritage, to just give an example of the anger some people had for the scheme, the leading critics were Sir Richard Lodge, Professor of History at Edinburgh University, Principal Laurie at Heriot-Watt College and Lady Francis Balfour who actually demanded that the Duke of Atholl and Sir Robert Lorimer should be hanged!!!!!

Such was some of the opposition that there were even proposals to abandon the whole scheme in the Castle altogether and to erect a memorial on Calton Hill or Princess Street Gardens.

Undaunted they began fundraising. However this too had its problems as the Memorial appeal coincided with large appeals being made by Edinburgh Infirmary and Edinburgh University and the many small appeals for Parish memorials, most of these that you see in our towns and villages were paid for by public subscription.

Lorimer did make substantial compromises to his plan. He suggested that Billing's Buildings should be retained and adapted to form a Memorial Gallery. On the North side he proposed a deep apse, the roof of this extension being no higher than the existing height of Billing's Buildings, protecting our famous skyline.

Finally, in April 1923 the opposition crumbled. The Ancient Monuments Board gave a favourable report on the changes, the War Office gave final consent and, in October of that year, the Government approved Lorimer's designs. Six years after Atholl had made his original proposals the project went to tender and work began.

Robert Lorimer paid regular weekend visits to Blair Castle to discuss the fine detail and how every regiment, service and corps should be remembered, including the animals who in their own way had served and suffered in the war. Some of the finest Scottish craftsmen and women of the day committed many hours to ensuring that every detail was correct. The windows had to lend a soft and subtle colour to the interior, but there had to be sufficient light to ensure that the names in the Books of Remembrance could be read.

The frieze in the Shrine, the work of Mrs Gertrude Alice Meredith Williams, was deemed by all to be a masterpiece and the Duke of Atholl was particularly delighted with it. Referring to "Mrs Meredith Williams' wonderful frieze", the Duchess of Atholl recorded, " The beauty of the frieze is in part due to her husband. During his three years in the ranks in France he made endless drawings of his fellow soldiers. The drawings furnished a priceless inspiration for the amazing number of men and women recorded in his wife's masterpiece".

Gertrude, who was commonly known as Alice Meredith Williams designed my favourite Scottish War memorial The "Spirit of the Crusaders" in Paisley.

It is clear from the records that both the Duke and the Duchess of Atholl played a major part in influencing the interior design of the building, particularly in relation to the subtle symbolism and the wonderful serenity and simplicity.

The first pic is a postcard ris fom the 1920s. It shows a view of the North End of the shrine and the Casket donated by King George V. The second pic is the entrance to the Memorial in Crown Square and is my own pic taken very early in the day in April 2013 before it got busy.

Below is a link to the official web site for The Scottish National War Memorial, on it you can find lots more info and pics. One thing that might interest you is the Roll of Honour where you can search all the names that are included in the books at the memorial, on the roll are 15 with my own surname, all but two from the first war, my own Grandfather fought in the war and was a Gunner, leading to my Dad getting called Gunner by all who knew him, in fact few even knew his real first name. https://www.snwm.org/

24 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

On July 14th 1927 The Scottish National War Memorial opened.

As this post regards the Memorial that was to become part of Edinburgh Castle, there is a wee bit history of the castle itself in this post. I recall putting a post together last year on it's centenary, but keeping it short as there ahd been many articles in the newspapers and online about it, this year with have devoted more time putting together this long post.

The National War Memorial for Scotland was established by Royal Charter to commemorate the sacrifice of Scots in the Great War, Second World War and subsequent conflicts. The Memorial within Edinburgh Castle houses and displays the Rolls of Honour of Scots servicemen and women from all the Armed Services, the Dominions, Merchant Navy, Women's Services, Nursing Services and civilian casualties of all wars from 1914 to date.

In 1927 the architect Sir Robert Lorimer and 200 Scottish artists and craftsmen created a serene Hall of Honour and Shrine, where the names of the dead are contained in books that are on permanent display.

A number of eminent Scots wanted a truly Scottish memorial, in Scotland, recording the names of all Scots and displaying Scottish material. The moving force behind this vision was John George 8th Duke of Atholl. A leading member of the Scottish aristocracy, the Duke of Atholl, or "Bardie" as he was known from his title, the Marquis of Tullibardine, was a serving soldier who had fought in the Sudan and had raised the Scottish Horse Yeomanry. He was a man of considerable vision and energy and, what was more important, he had both influence and connections.

In the spring of 1917 Atholl gathered around him a number of leading and powerful Scots. Atholl lost no time in promoting the Scottish case for a memorial. He wrote to the Commissioner of Works asking that Scotland should have her own memorial in the form of a museum collection to be housed in Edinburgh Castle. There then followed widespread consultation, which included the five Lord Provosts of the Cities of Scotland and extensive press coverage, largely in The Scotsman newspaper.

Initially there was concern on the part of the City of Glasgow and it was important that the City Fathers of Scotland's largest urban centre agree to the scheme. The problem was solved when Spencer Ewart hosted a dinner for all of the interested parties and agreement was obtained.

The choice of Edinburgh Castle was inspirational, historically interesting and sensitive.

The Castle stands high above the centre of the capital city of Scotland dominating the skyline for miles around. Even in 1914 the Castle was a major tourist attraction and its roots lay deep in the folklore and traditions of Scottish history.

Until 1914 it had been the main barracks for the Infantry garrison of Edinburgh and soldiers had lived there and guarded its walls for many centuries.

The standard of military accommodation within the Castle precincts was however very basic. The barrack rooms were crowded and draughty with leaky roofs. The accommodation was heated by small coal burning fires in open grates some of which were still used for cooking. There were only a few baths for the whole of the garrison, no running hot water and very basic toilet facilities. The one communal cookhouse meant that most of the men still ate in their barrack rooms.

As a result of these shortcomings a new barracks was built at Redford on the outskirts of the City which would house both infantry and cavalry units. These barracks were being built in 1914 just before the outbreak of war. It was therefore envisaged that when the war ended there would be vacant accommodation within the Castle walls which could be adapted for the Memorial plan.

In addition, the concept of a military museum was a very new idea which would not compete with existing regimental museums for there were none. The Scottish regiments were more likely to agree to a central location such as the Castle where they had all served at one time or another. By this time the individual regiments had acquired many regimental trophies and together with much of the silver, artefacts and archives these were usually deposited with the Regimental Depots and were not on display to the public. Thus the opportunity to show the regimental histories and traditions was welcomed.

The choice of Edinburgh Castle was however a sensitive one. Any proposal to alter the distinctive Edinburgh skyline by the building or demolition of any part of the existing structures was bound to meet with considerable opposition. This opposition was both vociferous and powerful and was in time to change the plan significantly.

In October 1918, a Scottish National War Memorial Committee was appointed by the Secretary of State for Scotland, "to consider what steps should be taken towards the utilization of Edinburgh Castle for the purposes of a Scottish National War Memorial". Great care had been taken with these appointments to ensure that the Services, the press, the church, learning, architecture, Scottish history, the cities and the political parties were all represented.

The architect Robert Lorimer designed the stunningly beautiful Chapel for the Knights of the Thistle in St Giles Cathedral, but advised against a church or chapel as it "would excite much opposition". It was estimated that the Memorial Shrine and Cloisters and the museum he proposed would cost a staggering £250,000.

While the money was a problem, there were many others that I won't go into in depth, needless to say, some were ploitical, others were fro, The Cockburn Society, who still do a great job to this day, trying to safeguard Edinburgh's heritage, to just give an example of the anger some people had for the scheme, the leading critics were Sir Richard Lodge, Professor of History at Edinburgh University, Principal Laurie at Heriot-Watt College and Lady Francis Balfour who actually demanded that the Duke of Atholl and Sir Robert Lorimer should be hanged!!!!!

Such was some of the opposition that there were even proposals to abandon the whole scheme in the Castle altogether and to erect a memorial on Calton Hill or Princess Street Gardens.

Undaunted they began fundraising. However this too had its problems as the Memorial appeal coincided with large appeals being made by Edinburgh Infirmary and Edinburgh University and the many small appeals for Parish memorials, most of these that you see in our towns and villages were paid for by public subscription.

Lorimer did make substantial compromises to his plan. He suggested that Billing's Buildings should be retained and adapted to form a Memorial Gallery. On the North side he proposed a deep apse, the roof of this extension being no higher than the existing height of Billing's Buildings, protecting our famous skyline.

Finally, in April 1923 the opposition crumbled. The Ancient Monuments Board gave a favourable report on the changes, the War Office gave final and unqualified consent and, in October of that year, the Government approved Lorimer's designs. Six years after Atholl had made his original proposals the project went to tender and work began.

Robert Lorimer paid regular weekend visits to Blair Castle to discuss the fine detail and how every regiment, service and corps should be remembered, including the animals who in their own way had served and suffered in the war.

Some of the finest Scottish craftsmen and women of the day committed many hours to ensuring that every detail was correct. The windows had to lend a soft and subtle colour to the interior, but there had to be sufficient light to ensure that the names in the Books of Remembrance could be read.

The frieze in the Shrine, the work of Mrs Gertrude Alice Meredith Williams, was deemed by all to be a masterpiece and the Duke of Atholl was particularly delighted with it. Referring to "Mrs Meredith Williams' wonderful frieze", the Duchess of Atholl recorded, " The beauty of the frieze is in part due to her husband. During his three years in the ranks in France he made endless drawings of his fellow soldiers. The drawings furnished a priceless inspiration for the amazing number of men and women recorded in his wife's masterpiece".

It is clear from the records that both the Duke and the Duchess of Atholl played a major part in influencing the interior design of the building, particularly in relation to the subtle symbolism and the wonderful serenity and simplicity.

As there is no photography allowed in the War Memorial, this video allows those who have not visited the chance to get a rare glimpse of the building.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On 9th April 1747 Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, the leading Scottish Jacobite rebel was beheaded on Tower Green.

A longer post than normal from me as in my opinion Simon Fraser was one of the most interesting characters in Jacobite history. A man of contrary, he was known to be very kind to the lesser clansmen taking a paternal interest in their affairs. A quote regarding him says that...."Generally he had a bag of farthings for when he walked abroad the contents of which he distributed among any beggars whom he met. He would stop a man on the road; inquire how many children he had; offer him sound advice; and promise to redress his grievances if he had any" In his own estimate, he took care his clansmen were ‘always well-clothed and well-armed, after the Highland fashion, and not to suffer them to wear low-country clothes’ Lovat was also a brute of a man forcing a young woman into marriage and raping her in an attempt to legitimise the union. Lovat has become more well know lately thanks to Outlander, where in their world he is grandfather to the main protagonist Jamie Fraser and played brilliantly by the fine Scottish actor Clive Russell. Back in the real world he has been in the news only this year, I shall cover that at the end of this post.

Born in 1667 into the ancient clan who fought with distinction in the Wars of Independence – Sir Simon Fraser was one of the co-victors of the Battle of Roslin and his sons were close friends of Robert the Bruce, Alexander marrying Bruce’s sister Mary – Simon was the second son of Thomas Fraser of Beaufort who was closely related to Lord Hugh Fraser of Lovat, chief of clan Fraser.

Simon became his father’s heir when his elder brother was killed fighting alongside Bonnie Dundee against the forces of King William III at the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689. He was still nowhere near being clan chief, however, and took himself off to Aberdeen University from which he graduated in 1695. Lord Hugh Fraser, the 9th Lord Lovat, was a weak man who unexpectedly signed over the clan leadership to Simon’s father in 1696.

Lord John Murray, Earl of Tullibardine and the most powerful man in Scotland, disputed the succession and fell out spectacularly with Simon in Edinburgh. The young Fraser hothead duly went north to Castle Dounie to try and persuade Hugh’s widow Amelia to give him the hand of her daughter, also Amelia, in a dynastic marriage that would seal his succession. Tullibardine was having none of it and moved his niece to the Murray stronghold, Blair Castle, where he planned to marry her off to Alexander Fraser, heir to the Lordship of Saltoun.

Simon retaliated by kidnapping Alexander and frightening him away, and to make matters worse in October, 1697, he went back to Castle Dounie and forced the widow Amelia into a sham wedding, raping her to consummate the “marriage”.

Tullibardine ensured Simon and his father were declared outlaws and when old Thomas died in 1699, Simon was unable to legally claim his title as 11th Lord Lovat which later passed to one Alexander Mackenzie who had legally married the younger Amelia.

Simon Fraser somehow managed to persuade King William that he was no threat, despite having his own personal army, and he was pardoned in 1700, only to be declared an outlaw again the following year over the forced marriage and rape.

Simon went off to the court of the Stuarts in France where he devised the plans that were eventually used in the 1715 and 1745 uprisings. Long before the former, however, Simon was double dealing, giving Queen Anne information about the plans of James, the Old Pretender. He was found out and King Louis XIV clapped him in jail for three years.

Even after he was released he was prevented from travelling to Scotland and thus missed the Act of Union which he opposed.

Still desperate to get his Lovat title and the chieftainship of his clan back, Simon sided with the forces of the new King, George I, during the ’15, and was given back his title as a reward, with Alexander Mackenzie imprisoned for being a Jacobite. The two men would fight in the courts for the next 15 years as to who was entitled to the income of the estate. Simon eventually won and spent his time building up the Fraser estates and wealth, even taking command of one of the Independent Companies of Highland soldiers established by the Hanoverian regime – the Fraser Highlanders.

As I said early Fraser was a man of contrary and to me was very like "Bobbing John" The Earl of Mar another Jacobite who a tendency to shift back and forth from faction to faction, no sooner had Fraser built up this "Hanoverian" army that he started openly campaigning for the restoration of the Stuarts. The Government responded by cancelling his military role.

When Bonnie Prince Charles landed in Scotland he was still playing games.

He allowed his sons to fight for the Stuarts, but stayed at home himself “loudly lamenting the wilful disobedience of children,” as Sarah Fraser has put it. Lovat did meet Charles, however, and expressed his anger at the lack of “siller” which he knew would be necessary for a successful campaign. They met again after Culloden, at which Clan Fraser fought bravely and suffered many casualties, and Lovat advised the prince to get away and re-form his forces. Charles fled through the heather, as we know, and made it to France while anyone associated with the Bonnie Prince was hunted down. The Duke of Cumberland’s troops were not taking any more games from Fraser and burned Castle Dounie.

Lovat managed to make it to Loch Morar but was captured there while hiding in a hollow tree. Although approaching his 80th birthday, The Fox was taken south to London.

He pled not guilty but his trial was a formality and he must have know his fate would be the same as previous nobles, the Earls of Kilmarnock, Balmerino and Derwentwater who were executed for treason the previous year.

At his trial, ever the Fox he insisted strongly upon his affection for the reigning family. Such were the characteristics of Simon Fraser, but of course he was found guilty the sentence, hanging, drawing and quartering was commuted later to a mere beheading by the King.

In a way, Lovat had the last laugh. Newspapers and pamphlets of the time recorded that as he was led out to the scaffold on Thursday, April 9, 1947, a wooden stand that had been erected near the Tower to seat crowds eager to see the execution collapsed sending hundreds plunging down. At least nine people died and dozens were injured, which amused Lovat – the phrase ‘laughing your head off’ is said to date from that event.

According to a woodcut print made on that fateful day, Lovat “with some composure laid his head on the block which the executioner took off with a single blow.”

As I mentioned at the top Lovat has been in the news lately, Simon had requested burial at the family mausoleum at Wardlaw near Inverness and the government initially agreed but changed its mind thinking his body could become a rallying point for further trouble. He was therefore buried in the floor of the chapel within the Tower of London, St. Peter ad Vincula. The chapel was refurbished in the 19th century and the floor was relaid. One of the coffins uncovered during the works had the nameplate of ‘Lord Lovat’. The names of those found are now recorded on a plaque on the wall of the chapel.

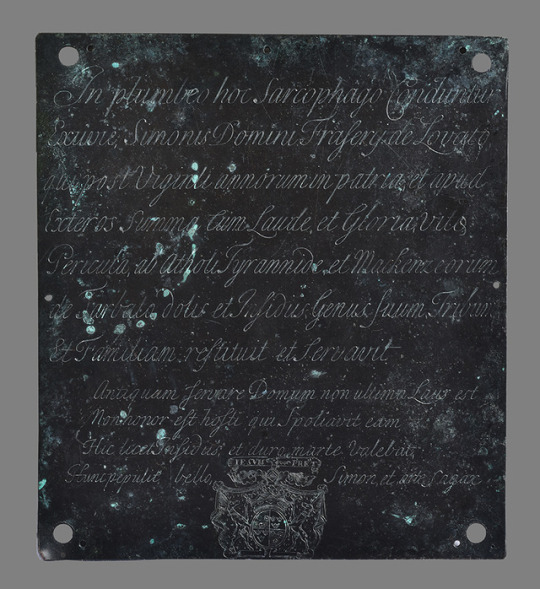

Fraser folklore, and written in several books says that his body was spirited away from London, the stories even go so far as to name the boat ‘The Pledger’ that sailed north to The Beauly Firth, where he was taken to the family mausoleum, there is even a plaque in the crypt that reads “In this coffin are laid the remains of Simon Lord Fraser of Lovat who, after twenty years in His own Land and abroad with the greatest distinction and renown, at the risk of his own life, restored and preserved his race, clan and household from the tyranny of the Athol and the treacherous plotting of the Mackenzies of Tarbat. To preserve an ancient house is not the greatest credit. Nor is there any honour for the enemy who despoiled it. Although that enemy was strong in his plotting and unrelenting warfare, yet Simon who was also skillful and cunning defeated him in war."

Last year the headless skeleton inside the coffin was exhumed to be examined by experts from the University of Dundee in January this year they announced that the bones in the coffin did not belong to Simon Fraser, but to a young woman. So it looks like his body did end up rotting in The Tower's Chapel.

To understand how big Lovat's trial and execution were I have posted a number of pics all dating back to the eighteenth century, and the plaque from the Crypt at Wardlaw.

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Next we visited the @outlander_starz filming site Tullibardine Chapel. #PodAbroad2019 . Do you remember which scenes were filmed here? https://www.instagram.com/p/Bw4JixoHBmi/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=10p212b981kry

0 notes