#Pyotr Kropotkin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Excerpt in background from Pyotr Kropotkin’s 1902 text, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution

Reading leftist theory really helps you see de in a fresh light, there’s something i will reblog this with that has interesting implications for the in-game use of the word moralists :’]

Have a nice day!

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emekçiler ücretleriyle kendi ürettikleri şeyi satın alamazlarken, omuzlarına basarak yaşayan aylaklar sürüsünü cömertçe besler...

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

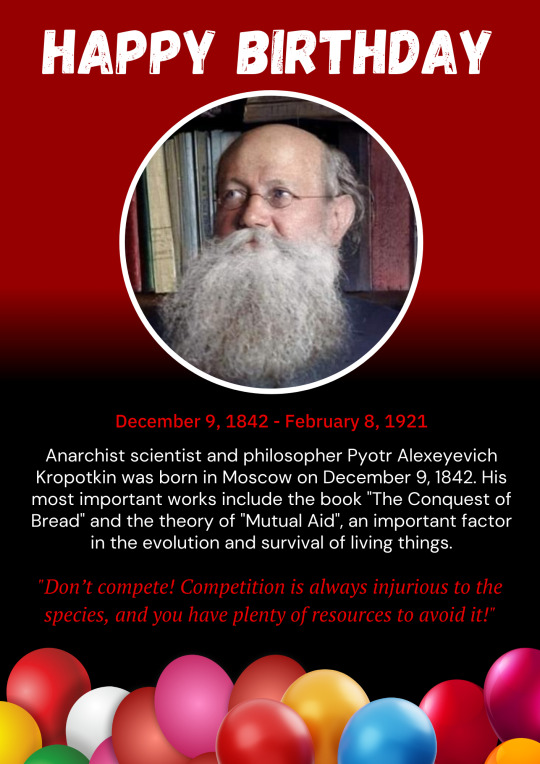

Today is the birthday of Anarcho-communist scientist and philosopher Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

To emancipate woman, is not only to open the gates of the university, the law courts, or the parliaments to her, for the "emancipated" woman will always throw her domestic toil on to another woman.

To emancipate woman is to free her from the brutalizing toil of kitchen and washhouse; it is to organize your household in such a way as to enable her to rear her children, if she be so minded, while still retaining sufficient leisure to take her share of social life.

It will come. As we have said, things are already improving. Only let us fully understand that a revolution, intoxicated with the beautiful words, Liberty, Equality, Solidarity, would not be a revolution if it maintained slavery at home.

Half humanity subjected to the slavery of the hearth would still have to rebel against the other half.

— Pyotr Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you haven't read Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution by Pyotr Kropotkin yet, you need to.

There are so many things I love about this book. Today what struck me is the way he points out that socializing, forming community, supporting each other etc. can actually boost your intelligence.

It makes perfect sense when I think about it - being around others and trying your best to understand them is a practice that exposes you to diversity and to new information, and trains your brain to remain open to bewilderment as a path to learning.

#pyotr kropotkin#peter kropotkin#mutual aid#anarchism#books#booklr#reading#cosmo gyres#personal#this book is so good in so many ways#i'm so happy to be reading it again

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#leftist#leftism#politics#marxism#socialism#anarchism#communism#anti capitalism#poll#polls#tumblr poll#tumblr polls#karl marx#pyotr kropotkin#vladimir lenin#mao zedong

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In its wide extension, even at the present time, we also see the best guarantee of a still loftier evolution of our race.

Pyotr Kropotkin, from Mutual Aid : A Factor of Evolution

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pyotr Alekseyeviç Kropotkin – Tarlalar, Fabrikalar ve Atölyeler (2024)

Kropotkin, en önemli eseri sayılan ve bugün de geçerliliğini koruyarak tarım ve küçük ölçekli sanayiler üzerine bilimsel araştırma yapanlar için çok zengin bir ansiklopedik bilgi kaynağı olmaya devam eden bu kitabında, daha sürdürülebilir ve eşitlikçi bir toplum yaratmak için insanları sıkıcı ve anlamsız işlerde çalışmaya zorlayan katı bir iş bölümü yerine tarımın sanayi ile zihinsel emeğin de…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

Hello Mr. Haitch!

Happy new year!

I feel like we already know the answers to a good chunk of these questions in the ask game :0

Soo I’ll ask my own weird questions—

1) If you could time travel at whim, which period would you like to experience personally. Would you still return to the present time, or would you rather stay in a different era?

2) I haven’t seen Squid games, but I have heard a lot about it. Do you think you and Haitch could survive and beat the different tasks in Squid games?

3) In a most freaky Friday fashion, if you switched bodies with Haitch for a day, what will you do?

Thank you in advance!

Hey Flaneur. Yes you're probably right, come to think of it. It might be more interesting to see what people guess my answers would be for each question.

1. That's a hard question. Every era has its pitfalls, most of them medical, ethical, and political. I would also most likely use it to settle grudges and punch historical figures (starting with Columbus).

Instead of an era, I want to be in London in the late 19th century when Pyotr Kropotkin was in exile and witness the furious debates between him and Charles Darwin's acolytes. I would also love to be Kropotkin's friend, as he's one of the few personal heroes I still have.

Look at that twinkly-eyed anarcho-communist Santa Claus.

2. Haitch absolutely would. I... wouldn't. I'm too honest, and the whole enterprise runs afoul of one of my personal maxims: if the game is rigged, don't play. I'd absolutely be double crossed and murdered, or killed trying to help someone.

3. Make sure she gets enough sleep.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Raging against the dying of the light: Chumbawamba don’t want to fade away

(Content note: HIV, suicide.)

I grew up with one Chumbawamba album that my mother had a self-burned copy of. It was not Tubthumper, but rather the calmer and much more melodious A Singsong and a Scrap (2005). Recorded by a much smaller Chumbawamba (Jude, Lou, Boff, and Neil) as half the band had left after the previous year’s Un to pursue their own projects, Singsong embraces a soft folk sound, foreshadowed already ten years prior on the Love-portion of Swingin’ with Raymond (1995). My favourite song on the album is By and By, an hommage to songwriter and labour activist Joe Hill (“don’t mourn, organise!”)—can you imagine a more beautiful epitaph?

Anyway, today yesterday I was listening to Fade Away (I Don’t Want to), on the same album. The title reminds me of Neil Young’s My My Hey Hey (Out of the Blue) (1979): “It’s better to burn out than to fade away”. In autumn 1980, John Lennon commented on this song as he understood it:

I hate it. It’s better to fade away like an old soldier than to burn out. If he was talking about burning out like Sid Vicious, forget it. I don't appreciate the worship of dead Sid Vicious or of dead James Dean or dead John Wayne. It’s the same thing. … If Neil Young admires that sentiment so much, why doesn’t he do it? Because he sure as hell faded away and came back many times, like all of us. No, thank you. I’ll take the living and the healthy.

This led Neil Young to clarify:

The rock’n’roll spirit is not survival. Of course the people who play rock’n’roll should survive. But the essence of the rock’n’roll spirit to me, is that it’s better to burn out really bright than to sort of decay off into infinity. Even though if you look at it in a mature way, you’ll think, “well, yes ... you should decay off into infinity, and keep going along”. Rock’n’roll doesn't look that far ahead. Rock’n’roll is right now.

When Kurt Cobain committed suicide in 1994, he left a note referencing this line: “I don’t have the passion anymore, and so remember, it’s better to burn out than to fade away.” I think it’s a line that reads very differently depending on what place you are in.

In 2005, Chumbawamba are in their forties. They’d tried to change the world with punk rock and had their time in the limelight, but to what avail? It must have been tiring:

It’s a mighty long way from my own front door To the world we were going to make We got bloodied and bruised for the old excuse That it’s hard just staying awake

It seems so easy to sit down in your rocking chair, remote control in hand, and turn to a Fine Career (The Boybands Have Won, 2008). And maybe that’s what their life looked like from the outside. In the liner notes to the song, they tell the story of meeting a 45-year old punk, like Chumbawamba at this point without spiky hair: “‘punk is here,’ (touches his heart) ‘I don’t need the clothes to prove it.’” This seems to have resonated with the band, now an uneasy listening folk act. But it is not the sound or the outward appearances that make the punk band: Chumbawamba have not surrendered their fight, they are still looking for a reason to kick and scream:

Wake me up if you catch me falling Gently into the Night Shine up my shoes ‘cos I can’t get used To the dying of the light

Dylan Thomas’s poem Do not go gentle into that good night (1951) describes the futile fight against death. Wise men, good men, wild men, grave men—when they feel death is near, they all “rage, rage against the dying of the light”. Even though for Chumbawamba the fight is not yet against death, the stakes are equally high: “Struggle! To struggle is to live, and the fiercer the struggle the intenser the life.” (Pyotr Kropotkin, Anarchist Morality, 1987).

I think it is worth noting that Do not go gentle inspired another of Chumbawamba’s songs: The closer of Anarchy (1994), Rage, is dedicated especially to the people behind Diseased Pariah News, a 1990s humorous zine by and for people who were HIV positive:

Hear the ghosts of everafter Yell of anger Ring of laughter Don’t go gently into the night Rage against the dying of the light.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: A tweet from @/likesmoth that says "People who don't like pickles are so important because they give me their pickles."

An edited version of that same tweet that says "People who like pickles are so important because they take my pickles." End ID.]

102K notes

·

View notes

Text

In the summer of 2018 I was at a movie night event with newly acquainted classmates from grad school. We were all still getting to know each other and one of them asked me something about my personal beliefs. I don’t remember the details but I remember admitting I was a Buddhist anarchist. I think the reason I put it in those terms had to do with the context of our discussion. Mind you, he is a Japanese classmate whom is fluent in English. But his response was something to the effect of, “How does that even make sense?” And his response filled me with the urge to lecture to him then and there about how Buddhism and anarchism are actually compatible if you really think about it. I was tempted to mention the Japanese Buddhist anarchist monk, Uchiyama Gudō (May 17, 1874 – January 24, 1911), and Emma Goldman’s personal friend from India, Har Dayal (14 October 1884 – 4 March 1939), but I resisted the urge. Instead I promised myself that I would write an essay expounding on this compatibility. So this essay is the result of that urge.

To be sure, I’m not saying Buddhism is to be conflated with anarchism prima facie. Many so-called Buddhist traditions did indeed serve as legitimators of tyrannical rulers and often fomented violent conflicts (e.g. the Genpei war, the Nanboku-chou conflicts, Ikko Ikki rebellions, and so on). And to explain what I mean by Anarchism, let me just first explain the source of my own anarchist convictions. Pyotr Kropotkin is possibly the most influential as he argued for peace and prosperity among humans in his Mutual Aid. The next proponent I draw from is Rudolf Rocker and his outline of Anarcho-Syndicalism as a communal answer to many of the problems that come with an imperfect world driven to subsistence should we fail to cultivate favorable conditions, agriculturally and infrastructurally. And third in my list of influencers would be Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, as he was instrumental in outlining the tyranny of property. And I personally define anarchism in the way atheists define atheism. Just as the prefix ‘a’ means “not” and ‘theist’ means “believer in god”- I am stating the prefix ‘an’ also means “not” and ‘archist’ is a catch-all for all things ending in “archy”: hierarchy, monarchy, oligarchy, patriarchy, etc. The objective of anarchism is to instill a sense of dignity in all people and to charge all with the agency to realize and defend their human rights.

I believe Buddhism and anarchism overlap from the start because both traditions aim to critique the status quo. Additionally, there are several key factors about the Buddhist dhamma and its relationship to political convention that I think makes it more compatible with anarchism than any other political ideology. These factors are expressed in five major juxtapositions: 1. Prince Siddhartha’s defiance against his father, Oligarch Śuddhodana; 2. The dhamma’s dissolution of the Hindu caste system in Northern India; 3. Specific texts accredited to the Buddha that speak against dogmatism; 4. The Sangha’s function as a commune living beyond the limits of monarchies and oligarchies (and often functioning as sanctuaries beyond political realms); 5. Tales of the Buddha and his discourses with the Hindu gods. There is a lot to explore here, so let’s get right into it.

#desi#desiblr#Buddhism#Caste#India#nonviolence#pacifism#community building#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#mutual aid#grassroots#organization#anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#anarchy#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economics

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Equity Education and Mutual Justice Resources: The Book List

Anti-Racism and Intersectionality How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi

Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil by W.E.B. Du Bois On Critical Race Theory: Why It Matters & Why You Should Care by Victor Ray

You Are Your Best Thing: Vulnerability, Shame Resilience, and the Black Experience by Tarana Burke (Editor) Brené Brown (Editor) Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America by Ibram X. Kendi

So You Want to Talk About Race By Ijeoma Oluo

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

I'm Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness by Austin Channing Brown

Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde

Raising White Kids: Bringing Up Children in a Racially Unjust America by Jennifer Harvey

Why I'm No Longer Talking to White People about Race by Reni Eddo-Lodge

The Undocumented Americans by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio

Mutual Aid, Direct Action, Organizing, and Community Building

Let This Radicalize You: Organizing and the Revolution of Reciprocal Care by Mariame Kaba and Kelly Hayes

Just Action: How to Challenge Segregation Enacted Under the Color of Law by Richard Rothstein and Leah Rothstein

Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next) by Dean Spade

Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution by Pyotr Kropotkin

Living at the Edges of Capitalism: Adventures in Exile and Mutual Aid by Andrej Grubačić

Viral Justice: How We Grow the World We Want by Ruha Benjamin

We Do This 'til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice by Mariame Kaba

Practicing Cooperation: Mutual Aid beyond Capitalism by Andrew Zitcer

Practicing New Worlds: Abolition and Emergent Strategies by Andrea Ritchie

Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement by Angela Y. Davis Anti-Capitalist and Anti-Colonialism Education

The Poverty of Growth by Olivier De Schutter

Becoming Abolitionists: Police, Protests, and the Pursuit of Freedom by Derecka Purnell, Karen Chilton, et al.

The Future Is Degrowth: A Guide to a World Beyond Capitalism by Aaron Vansintjan, Matthias Schmelzer, and Andrea Vetter

Except for Palestine: The Limits of Progressive Politics by Marc Lamont Hill, Mitchell Plitnick, et al.

Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism by Elmar Altvater (Author), Eileen C. Crist (Author), Donna J. Haraway (Author), Daniel Hartley (Author), Christian Parenti (Author), Justin McBrien (Author), Jason W. Moore (Editor) (Also available as a PDF online)

Dying for Capitalism: How Big Money Fuels Extinction and What We Can Do About It by Charles Derber, Suren Moodliar

On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century by Timothy Snyder History and Political Science

A People's History of the United States by Howard Zinn

Black Marxism, Revised and Updated Third Edition: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition by Cedric J. Robinson

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein

Palestine: A Socialist Introduction by Sumaya Awad (Editor) and Brian Bean (Editor)

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander (this technical book also has an organizing guide and study guide)

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann

Time's Monster: How History Makes History by Priya Satia

We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance by Kellie Carter Jackson

How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them by Jason Stanley

Indigenous Knowledge

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer (there is also a version of Braiding Sweetgrass for young adults)

Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our Future by Patty Krawec

Indian Givers: How Native Americans Transformed the World by Jack Weatherford

Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California's Natural Resources by Kat Anderson

Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes Through Indigenous Science by Jessica Hernandez Disability Education and Rights Demystifying Disability: What to Know, What to Say, and How to Be an Ally by Emily Ladau Black Disability Politics by Sami Schalk

Crip Kinship: The Disability Justice & Art Activism of Sins Invalid by Shayda Kafai

Pandemic Solidarity: Mutual Aid during the Coronavirus Crisis by Marina Sitrin (Editor), Rebecca Solnit (Editor)

Disability Intimacy: Essays on Love, Care, and Desire by Alice Wong

The Future Is Disabled: Prophecies, Love Notes, and Mourning Songs by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Refusing to Be Made Whole: Disability in Black Women's Writing by Anna Laquawn Hinton

Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity by Devon Price (this author also has a guide on the same topic)

Queer Issues

We Are Everywhere: Protest, Power, and Pride in the History of Queer Liberation Hardcover by Matthew Riemer and Leighton Brown Transgender History: The Roots of Today's Revolution by Susan Stryker

Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman by Leslie Feinberg

Stonewall: The Definitive Story of the LGBTQ Rights Uprising That Changed America by Martin Duberman

Beyond the Gender Binary by Alok Vaid-Menon

Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe (graphic novel) Refusing Compulsory Sexuality: A Black Asexual Lens on Our Sex-Obsessed Culture by Sherronda J Brown

A Queer History of the United States by Michael Bronski

The Gay Agenda: A Modern Queer History & Handbook by Ashley Molesso and Chessie Needham

They/Them/Their: A Guide to Nonbinary and Genderqueer Identities by Eris Young

Gender Outlaws: The Next Generation by Kate Bornstein and S. Bear Bergman

This Book Is Gay by Juno Dawson (Author) and David Levithan (Contributor)

Nonbinary For Beginners: Everything you’ve been afraid to ask about gender, pronouns, being an ally, and black & white thinking by Ocean Atlas

All Boys Aren't Blue: A Memoir-Manifesto by George M. Johnson

Gender: A Graphic Guide by Meg-John Barker and Jules Scheele (Illustrator)

Resources for Kids and Parents

The Every Body Book: The LGBTQ+ Inclusive Guide for Kids about Sex, Gender, Bodies, and Families by Rachel E. Simon (Author) and Noah Grigni (Illustrator)

This Is a Book for Parents of Gay Kids: A Question & Answer Guide to Everyday Life by Dan Owens-Reid and Kristin Russo This Book Is Feminist: An Intersectional Primer for Next-Gen Changemakers by Jamia Wilson and Aurelia Durand (Illustrator)

Unlearning White Supremacy and Colonialist Culture

The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love by Sonya Renee Taylor

Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto by Tricia Hersey

White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism by Robin Diangelo

Black Rage by William H. Grier and Price M. Cobbs

White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide by Carol Anderson

How to Understand Your Gender: A Practical Guide for Exploring Who You Are by Alex Iantaffi and Meg-John Barker

This Book Is Anti-Racist: 20 Lessons on How to Wake Up, Take Action, and Do the Work by Tiffany Jewell (Author) and Aurelia Durand (Illustrator)

Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More by Janet Mock

Gender Trauma: Healing Cultural, Social, and Historical Gendered Trauma by Alex Iantaffi

The Politics of Trauma: Somatics, Healing, and Social Justice by Staci Haines

Brainwashed: Challenging the Myth of Black Inferiority by Tom Burrell

Me and White Supremacy: Combat Racism, Change the World, and Become a Good Ancestor by Layla F. Saad

Articles and Online Resources (Including Research Articles)

White Supremacy Culture by Tema Okun, at dRworks (This is a list of characteristics of white supremacy culture that show up in our organizations and workplaces.)

Reflections on Agroecology and Social Justice in Malwa-Nimar by Caroline E. Fazli

Mutual Aid Toolbox by Big Door Brigade Mutual Aid Resources by Mutual Aid Disaster Relief No body is expendable: Medical rationing and disability justice during the COVID-19 pandemic by Andrews, Ayers, Brown, Dunn, & Pilarski (2021)

A Marxist Theory of Extinction by Troy Vettese

Intersectionality Research for Transgender Health Justice: A Theory-Driven Conceptual Framework for Structural Analysis of Transgender Health Inequities by Linda M. Wesp, Lorraine Halinka Malcoe, Ayana Elliott, and Tonia Poteat Know Your Rights Guide to Surviving COVID-19 Triage Protocols by NoBody is Disposable

Finally Feeling Comfortable: The Necessity of Trans-Affirming, Trauma-Informed Care by Alex Petkanas (on TransLash Media)

'Are you ready to heal?': Nonbinary activist Alok Vaid-Menon deconstructs gender by Jo Yurcaba

Gender-affirming Care Saves Lives by Kareen M. Matouk and Melina Wald

What It Takes to Heal: How Transforming Ourselves Can Change the World by Prentis Hemphill

Note from the curator: Please use your local libraries when possible! Be #ResiliencePunk.

#Free Palestine#Anticapatalist#ResiliencePunk#Disability Justice#Food Justice#Mutual Aid#Resource List#Recommended Books#Disability#Social Justice#Anti Colonization#Black Rights#Agroecology#Queer History

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the same way, those who man the lifeboat do not ask credentials from the crew of a sinking ship; they launch their boat, risk their lives in the raging waves, and sometimes perish, all to save men whom they do not even know. And what need to know them?

'They are human beings, and they need our aid - that is enough, that establishes their right - To the rescue!'

— Pyotr Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

do we have any conclusive evidence pyotr kropotkin wasn't karl marx wearing a pair of glasses clark kent style

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

[Video] Rare footage of anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin in 1917 at the age of 74

Peter Alekseyevich Kropotkin, (born December 9, 1842, Moscow, Russia—died February 8, 1921, Dmitrov, near Moscow), Russian revolutionary and geographer, the foremost theorist of the anarchist movement. Although he achieved renown in a number of different fields, ranging from geography and zoology to sociology and history, he was eternalized for the life of a revolutionist.

Early life and conversion to anarchism

The son of Prince Aleksey Petrovich Kropotkin, Peter Kropotkin was educated in the exclusive Corps of Pages in St. Petersburg. For a year he served as an aide to Tsar Alexander II and, from 1862 to 1867, as an army officer in Siberia, where, apart from his military duties, he studied animal life and engaged in geographic exploration.

Kropotkin’s findings won him immediate recognition and opened the way to a distinguished scientific career. But in 1871 he refused the secretaryship of the Russian Geographical Society and, renouncing his aristocratic heritage, dedicated his life to the cause of social justice. During his Siberian service he already had begun his conversion to anarchism—the doctrine that all forms of government should be abolished—and in 1872 a visit to the Swiss watchmakers of the Jura Mountains, whose voluntary associations of mutual support won his admiration, reinforced his beliefs. On his return to Russia he joined a revolutionary group, the Chaiykovsky Circle, that disseminated propaganda among the workers and peasants of St. Petersburg and Moscow. At this time he wrote “Must We Occupy Ourselves with an Examination of the Ideal of a Future System?,” an anarchist analysis of a postrevolutionary order in which decentralized cooperative organizations would take over the functions normally performed by governments.

He was imprisoned in 1874 for his ideas but was freed by his comrades in a sensational escape 2 years later, fleeing to western Europe, where his name soon became revered in radical circles. The next few years were spent mostly in Switzerland until he was expelled at the demand of the Russian government after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II by revolutionaries in 1881. He moved to France but was arrested and imprisoned for 3 years on trumped-up charges of sedition. Released in 1886, he settled in England, where he remained until the Russian Revolution of 1917 allowed him to return to his native country.

Philosopher of revolution

Kropotkin’s aim, as he often remarked, was to provide anarchism with a scientific basis. In Mutual Aid, which is widely regarded as his masterpiece, he argued that, despite the Darwinian concept of the survival of the fittest, cooperation rather than conflict is the chief factor in the evolution of species. Providing abundant examples, he showed that sociability is a dominant feature at every level of the animal world. Among humans, too, he found that mutual aid has been the rule rather than the exception. He traced the evolution of voluntary cooperation from the primitive tribe, peasant village, and medieval commune to a variety of modern associations—trade unions, learned societies, the Red Cross—that have continued to practice mutual support despite the rise of the coercive bureaucratic state. The trend of modern history, he believed, was pointing back toward decentralized, nonpolitical, cooperative societies in which people could develop their creative faculties without interference from rulers, clerics, or soldiers.

In his theory of “anarchist communism,” according to which private property and unequal incomes would be replaced by the free distribution of goods and services, Kropotkin took a major step in the development of anarchist economic thought. Kropotkin envisioned a society in which people would do both manual and mental work, both in industry and in agriculture. Members of each cooperative community would work from their 20s to their 40s, four or five hours a day sufficing for a comfortable life, and the division of labour would yield a variety of pleasant jobs, resulting in the sort of integrated, organic existence.

To prepare people for this happier life, Kropotkin pinned his hopes on the education of the young. To achieve an integrated society, he called for education that would cultivate both mental and manual skills. Due emphasis was to be placed on the humanities and on mathematics and science, but, instead of being taught from books alone, children were to receive an active outdoor education and to learn by doing and observing firsthand, a recommendation that has been widely endorsed by modern educational theorists. Drawing on his own experience of prison life, Kropotkin also advocated a thorough modification of the penal system. Prisons, he said, were “schools of crime” that, far from reforming the offender, subjected him to brutalizing punishments and hardened him in his criminal ways. In the future anarchist world, antisocial behaviour would be dealt with not by laws and prisons but by human understanding and the moral pressure of the community.

Kropotkin combined the qualities of a scientist and moralist with those of a revolutionary organizer and propagandist. For all his mild benevolence, he condoned the use of violence in the struggle for freedom and equality, and, during his early years as an anarchist militant, he was among the most vigorous supporters of “propaganda by the deed”—acts of insurrection that would supplement oral and written propaganda and help to awaken the rebellious instincts of the people. He was the principal founder of both the English and Russian anarchist movements and exerted a strong influence on the movements in France, Belgium, and Switzerland.

Return to Russia of Peter Alekseyevich Kropotkin

Events took an unexpected turn with the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917. Kropotkin, by this time age 74, hastened to return to his homeland. When he arrived in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) in June 1917 after 40 years in exile, he was greeted warmly and offered the ministry of education in the provisional government, a post he brusquely declined. Yet his hopes for the future were never brighter, because in 1917 the organizations that he thought might form the basis of a stateless society—the communes and soviets, or soldiers’ and workers’ councils—suddenly began to appear in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

With the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917, however, his earlier enthusiasm turned to bitter disappointment. “This buries the revolution,” he remarked to a friend. The Bolsheviks, he said, have shown how the revolution was not to be made—that is, by authoritarian rather than libertarian methods. Kropotkin’s last years were devoted chiefly to writing a history of ethics, one volume of which was completed. He also fostered an anarchist cooperative in the village of Dmitrov, north of Moscow, where he died in 1921. His funeral, attended by tens of thousands of admirers, was the last occasion in the Soviet era when the black flag of anarchism was paraded through the Russian capital.

Kropotkin’s life exemplified the high ethical standard and the combination of thought and action that he preached throughout his writings. He displayed none of the egotism, duplicity, or lust for power that marred the image of so many other revolutionaries. Because of this he was admired not only by his own comrades but by many for whom the label of anarchist meant little more than the dagger and the bomb. The French writer Romain Rolland said that Kropotkin lived what Leo Tolstoy only advocated, and Oscar Wilde called him one of the two really happy men he had known.

#��ροπότκιν#kropotkin#piotr kropotkin#peter kropotkin#russia#russian#anarchist#anarchism#anarchy#newsreel#old#old film#old movie#black and white#Youtube

30 notes

·

View notes