#Pezhetairoi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Pezhetairoi

The pezhetairoi (foot companions) were part of the imposing army that accompanied the Macedonian commander Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE) when he crossed the Hellespont to face the Persian king Darius III in 334 BCE. Armed with long pikes (sarissas), the pezhetairoi fought in a Greek phalanx formation and played an important role in the battles of the Granicus, Issus, and Gaugamela.

Origin

Like with the hypaspist, the origin and evolution of the pezhetairos (plural: pezhetairoi) are shrouded in mystery. Except for references to them in discussions of Philip II and Alexander, the term pezhetairoi is hardly found in ancient literature. In his The Army of Alexander the Great, historian Stephen English wrote that, at some inexact point, the peasantry was recruited territorially and organized into infantry, and, according to the historian Anaximenes, it was given the name pezhetairoi. He added that the pezhetairoi were "essentially an evolution of the standard phalanx" (3).

However, disagreements still persist: some scholars refer to all of the Macedonian infantry as pezhetairoi while others believe they were not front-line infantry but bodyguards to the king. English contends that the pezhetairoi may have been created as a select, elite infantry acting as royal bodyguards under the Macedonian king Alexander I (498-454 BCE). It is claimed by some that this elite infantry eventually became the hypaspists. It was Alexander III (the Great) who would extend the term pezhetairoi to include all of the heavy phalanx infantry with the exception of the hypaspists.

Continue reading...

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week's main project: Macedonian pezhetairoi (foot companions)

Going back to (predominately) traditional method for these boys and yes, it does take longer. I still have the shields to do before I base them, though.

I painted these with the intent of using them with Warlord Games' SPQR skirmish ruleset, a game they're sadly phasing out due to the very understandable reason that they make a lot of games and can't focus on all of them. But, I might base my SPQR warbands on square bases anyway, where applicable, for use in Hail Caesar, their mass-battle ancients ruleset. Maybe not these ones, though. If I get into Hail Caesar, it'll mean painting these by the HUNDREDS (seriously, the starter army for the successor states has a full hundo of these pointy lads... and a war elephant!) and I might want to find a faster scheme?? idk... I'm more excited about the bronze age range for HC, but I can see myself getting more into these other periods too.

Oh no, am I becoming a...

historical wargamer???

#warlord games#spqr#hail caesar#miniature painting#miniatures#macedonians#pezhetairoi#pointy lads#wargaming#historical

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pezhetairoi

Les pezhetairoi (compagnons fantassins) faisaient partie de l'imposante armée qui accompagnait le commandant macédonien Alexandre le Grand (r. de 336 à 323 av. J.-C.) lorsqu'il traversa l'Hellespont pour affronter le roi perse Darius III en 334 avant notre ère. Armés de longues piques (sarissas ou sarisses), les pezhetairoi combattaient en formation de phalange grecque et jouèrent un rôle important dans le bataille du Granique, la bataille d'Issos et la bataille de Gaugamèles.

Lire la suite...

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Kind of related to the ask on Cleopatra, and even your one way earlier on Krateros… What do you think Alexander would’ve been like if he weren’t an Argead, and instead fated to be a Marshal for whoever else was meant for the throne? Do you think he would’ve been rebellious? Or cutthroat and ambitious like Krateros? Or more-so disciplined and loyal? I kind of see him as a combination of all three because I don’t peg Alexander for someone who can be contained, lol.

To answer this, we must keep in mind that, for the ancient Greeks, belief in divine parentage for certain family lines was very real. A given family and/or person ruled due to their descent. The heroes in Homer had divine parents/grandparents/great-grandparents. This notion continued into the Archaic period with oligarchic city-states ruled by hoi aristoi: “the best men.” (Yes, our word “aristocrat” comes from that.) Many of these wealthy families claimed divine ancestry; that’s why they were “best.”

In the south, this began to break down from the 5th century into the 4th. But not in Macedonia, Thessaly, or Epiros. In fact, even by Alexander’s day, many Greek poleis remained oligarchies, not democracies. And in democracies, “equality” was reserved for a select group: adult free male citizens. Competition (agonía) was how to prove personal excellence (aretȇ), and thereby gain fame (timȇ) and glory (kléos). All this was still regarded as the favor of the gods.

Alexander believed himself destined for great things because he was raised to believe that, as a result of his birth. Pop history sometimes presents only Olympias as encouraging his “special” status. But Philip also inculcated in Alexander a belief he was unique. He (and Olympias) got Alexander an Epirote prince as a lesson-master, then Aristotle as a personal tutor. Philip made Alexander regent at 16 and general at 18. That’s serious “fast track.” Alexander didn’t earn these promotions in the usual way; he was literally born to them.

If Alexander hadn’t been an Argead, that would have impacted his sense of his place in the world no less than it did because he was an Argead. What he might have reasonably expected his life path to take would have depended heavily on what strata of society he was born into.

Were he a commoner, in the Macedonian military system, his ambitions might have peaked at decadarch/dekadarchos (leader of a file). Higher officer positions were reserved for aristocrats through Philip’s reign. With Alexander himself, after Gaugamela, things started to change for the infantry, at least below the highest levels (but not in the cavalry, as owning a horse itself was an elite marker). Under Philip, skilled infantry might be tagged for the Pezhetairoi (who became the Hypaspists under ATG). But Alexander himself wouldn’t have qualified because those slots weren’t just for the best infantrymen, but the LARGEST ones. (In infantry combat, being large in frame was a distinct advantage.) So as a commoner, Alexander’s options would have been severely limited.

Things would have got more interesting if he’d been born into the ranks of the Hetairoi families, especially if from the Upper Macedonian cantons.

Lower cantons were Macedonian way back. If born into those, he (and his parents) would have been jockeying for a position as syntrophos (companion) of a prince. Then, he’d try to impress that prince and gain a position as close to him as possible, which could result in becoming a taxiarch/taxiarchos or ilarch/ilarchos in the infantry or cavalry. But he’d better pick the RIGHT prince, as if his wound up failing to secure the kingship, he might die, or at least fall under heavy suspicion that could permanently curtain real advancement.

That was the usual expectation for Lower Macedonian elites. Place as a Hetairos of the king and, if proven worthy in combat, relatively high military command. Yes, like Krateros. But hot-headedness could curtail advancement, as apparently happened to Meleagros, who started out well but never advanced far. The higher one rose, the more one became a potential target: witness Philotas, and later Perdikkas. In contrast, Hephaistion was Teflon (until his death). Yet Hephaistion’s status rested entirely on his importance to Alexander. And he probably wasn’t Macedonian anyway; nor was Perdikkas from Lower Macedonia, for that matter.

The northern cantons were semi-independent to fully autonomous earlier in Macedonian history. Their rulers also wore the title “basileus” (king); we just tend to translate it as “prince” to acknowledge they became subservient to Pella/Aigai. Philip incorporated them early in his reign, and I think there’s a tendency to overlook lingering resentment (and rebellion) even in Philip’s latter years. Philip’s mother was from Lynkestis, and his first wife (Phila) from Elimeia. Those marriages (his father’s and his) were political, not love matches.

Similarly, Oretis was independent, and originally more connected to Epiros. Note that Perdikkas, son of Orontes, was commanding entire battalions when he, too, was comparatively young. Like Alexander, he was “born” to it. Carol King has a very interesting chapter on him in the upcoming collection I’m editing, one that makes several excellent points about how later Successors really did a number on Perdikkas’s reputation (and not just Ptolemy).

If Alexander had been born into one of these royal families from the upper cantons, quasi-rebellious attitudes might be more likely. Much would depend on how he wanted to position himself. Harpalos, Perdikkas, Leonnatos, Ptolemy…all were from upper or at least middle cantons. They faired well. For that matter, Parmenion himself may have been from an upper canton and decided to throw in his hat with Philip.

By Philip’s day, trying to be independent of Pella was not a wise political choice, but if one came from a royal family previously independent, we can see why that might be seductive. Lower Macedonia had always been the larger/stronger kingdom. But prior to Philip, Lynkestis and Elimeia both had histories of conflict with Macedonia, and of supporting alternate claimants for the Macedonian throne. At one point in (I think?) the Peloponnesian War, Elimeia was singled out as having the best cavalry in the north. Aiani, the main capital, had long ties WEST to Corinthian trade (and Epirote ports). It was a powerful kingdom in the Archaic/early Classical era, after which, it faded.

So, these places had proud histories. If Alexander had been born in Aiani, would he have been willing to submit to Philip’s heir? Maybe not. But realistically, could he have resisted? That’s more dubious. By then, Elimeia just didn’t have the resources in men and finances.

I hope this gives some insight into how much one’s social rank influenced how one learned to think about one’s self. Also, it gives some insight into political factions in Macedonia itself. As noted, I believe we fail to recognize just how much influence Philip had in uniting Lower and Upper Macedonia. Nor how resentment may have lingered for decades. I play with this in Dancing with the Lion: Rise, as I do think it had an impact on Philip’s assassination.

(Spoiler!)

Philips discussion with his son in the Rise, and his “counter-plot” (that goes awry) may be my own invention, but it’s based in what I believe were very real lingering resentments, 20+ years into Philip’s rule.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Alexander alternate history#ancient Macedonia#ancient Macedonian politics#Upper Macedonia#Lower Macedonia#Macedonian internal politics#Philip II of Macedon#ancient history#Classics

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Los pezhetairoi son tanques vivientes, seres con una resistencia sobrenatural capaz de aguantar lo que le tiren.

Su rol en el combate es el de proteger a sus aliados y atraer el fuego de sus enemigos. No obstante, eso no significa que no tengan capacidad ofensiva, un pezhetairoi es perfectamente capaz de dar un buen golpe, y hasta de usar la fuerza del rival en su contra.

Una cosa es segura, si eres un buen pezhetairoi no te faltarán grupos a los que unirte, pues a todo el mundo le gusta tener a uno de estos cubriéndoles las espaldas.

Esta clase se beneficia de altas puntuaciones de resistencia y de fuerza.

1 note

·

View note

Note

ALSO how did you pick the name Sarissa

I wanted something greek or macedonian to tie her back to the origin of satyrs and I like names that are also objects. I couldn't think of anything more macedonian than a Sarissa - the extremely long pikes used by Alexander's (and Philip II's) pezhetairoi.

#asks#not art#sarissa#there's not much more symbolism in there other than I love spears and her sword is also really long

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Macedonian pezhetairoi for Hail Caesar/SPQR. A box of these (the SPQR release) was in the Warlord mystery box I ordered this year.

I got the Coat d'Arms Ancients paint set in today and felt like giving it a test run, along with some Vallejo dark vermillion and Army Painter zealot yellow to tint some metallics, since the bronze in the ancients set was very heavily separated.

(yes, my wrist is killing me. assembly's fair more painful than painting right now, though)

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

I forgot who it was, but I always found it so curious that it was recorded that Hephaistion was “wounded in the arm” during one of the battles. I know only the important things tended to be recorded, and of course, war and injury go hand-in-hand. I’m guessing that was pointed out because it was a really, really bad injury. Right? Not sure how that mention would’ve been relevant otherwise.

Arrian recorded Hephaistion’s injury.

In general, Arrian records a lot of military details that the other sources ignore or lack an interest in. Even so, with rare exceptions, his focus remains the army elite. And yes, Hephaistion is certainly among the elite, both owing to his importance to Alexander, but also, here, his role in the battle.

Diodoros tells us he fought first among the somatophylakes, or bodyguard. This has sometimes been misunderstood due to Diodoros’s tendency to mix-and-match terms. Diodoros doesn’t mean the 7-man unit of Somatophylakes, who didn’t fight together anyway. Their role as bodyguards was OFF the field. And I don’t think Hephaistion was a member of that unit yet anyway.

So what does he mean? The agema, or Royal squadron, of the Hypaspists. There were “regular” Hypaspists, and “royal” Hypaspists. Under Philip, this unit (then called Pezhetairoi) was the personal guard of the king in combat. When the unit itself came to be is a more involved discussion, but Philip made a significant change: he picked men for their size and fighting skill, not their high birth. Yet that was for the “regular” Hypaspists only, and it became one of the first pathways to advancement on skill alone in the Macedonian army. The royal unit, however, was another matter. Both Philip and Alexander made their military changes gradually.

Even under Philip, the Hypaspists were a stepping stone to higher commands for the sons of Hetairoi (Macedonian aristocrats). The whole unit was under the command of Nikanor, son of Parmenion. It was second only to the Companion Cavalry in prestige (which was commanded by Nikanor’s elder brother Philotas).

Yet overall command was different from unit command. E.g., Philotas commanded the Companions as a whole, but Kleitos Melas (Black Kleitos) commanded the Companion agema (royal unit) of Companion Cavalry. The king might lead that unit in battle, but he didn’t have time for the day-to-day duties of unit command, so Kleitos was their commander.

Similarly, by Gaugamela, Hephaistion had been advanced to command the Hypaspist agema. This may be why, later, Alexander advanced both him and Kleitos to joint command of the Companion Cavalry, after Philotas’s arrest and execution. Each had commanded the two most prestigious individual units in the army.

If Heckel is right (and I think he is), the Hypaspist agema at Gaugamela served as hammippoi, an elite form of hoplite who, literally, ran with the cavalry. (Keep in mind the horses would be mostly trotting or cantering, not galloping for long.) The job of the hammippoi was to help protect the horses and any cavalryman who was unhorsed, as the cavalry were much more lightly armed. But it’s a demanding job, to be sure.

At Gaugamela, Arrian tells us specifically of an encounter as Alexander returned with his Companion agema, after breaking off pursuit of Darius. They accidentally collided with some fleeing Persians and Indians (et al.), and it became the hardest fighting in the entire battle, as the fleeing men were desperate. I suspect this is where Hephaistion was wounded, as we’re told something like 60 Companions died in that engagement alone. It was brutal.

All that may help contextualize why Arrian names Hephaistion’s wounding. along with a couple others. He was the commander of a very important unit in the army.

#asks#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Hypaspists#Hammippoi#Battle of Gaugamela#Alexander the Great#ancient Greece#ancient military history#Arrian#Classics#tagamemnon

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Dr. Reames! I wondered if you’d read ‘Philip and Alexander: Kings and Conquerers’ by Adrian Goldsworthy, or if you had any opinion on it? I’m thinking about buying it but I wasn’t too sure about it and thought I’d ask you! :)

I have not read it, no, so I can't tell you much about it.

Goldsworthy is a respected military historian, but really a Romanist. That's part of why I've not hurried to read the book. Every year a BOATload of articles by specialists comes out, so my reading time tends to go to that, to keep up with what my colleagues are theorizing. I just reviewed the Pownall/Asirvatham/Muller collection The Courts of Philip & Alexander the Great (from DeGruyter). I recommend it. There are a couple oddball papers in it, but that's true of most conference proceedings. Quite a few important articles in that collection, if the court is your thing. :-)

But it is, of course, ridiculously expensive. So get it from a library, via ILL (interlibrary loan).

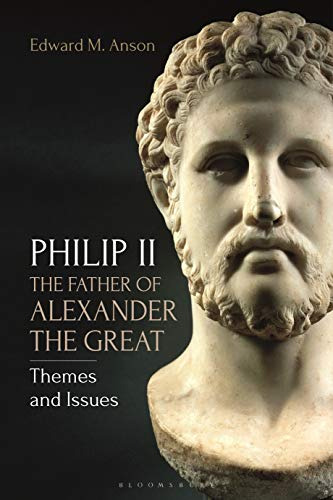

If you want a more introductory book, and more reasonably priced, I'd recommend Ed Anson's recent one Philip II: Father of Alexander the Great. Themes and Issues. It's really meant as a textbook, but it's one of the better recent books on ol' Phil. And (unlike Goldsworthy) Anson is a Macedonian specialist, especially on Philip.

So I'd put my money into Anson's book, not Goldsworthy's. the latter may be perfectly fine--probably is--but also probably won't reflect the most recent work in the field, which Ed's will. (I still think he's wrong about when the Pezhetairoi came to be applied to the whole phalanx, but that's a specialists' quarrel, ha. Ed's scholarship is dead solid.)

#Adrian Goldsworthy#Edward Anson#recent publications on Alexander the Great and Philip#Frances Pownall#Alexander the Great#Philip II

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

No todos los mitos y leyendas son protagonizadas por el mismo tipo de héroe. Podemos encontrarnos a luchadores bravos, habidos estrategas, sigilosos y determinantes combatientes, seguros y robustos contendientes, o incluso hechiceros guiados por dioses. La pregunta es; ¿Qué tipo de héroe serás tú?

Clases disponibles:

Estrategos

Hoplita

Peltasta

Pezhetairoi

Magus

1 note

·

View note

Note

How much of Alexander's death can be attributed to his last wound in the Mallian siege? I guess the real question is how much his last wound compromised his life (as a warrior and a leader), and would he still have been taken seriously in the battlefield (in the hypothetical Arabian campaign) if he could not lead as he previously did (what with the troops' waning enthusiasm for his campaigns). How important is the fighting from the front angle to Macedonian kingly traditions?

Alexander is the last of the “Great Generals” to lead from the front. This form of command was already falling out of fashion due to the rise in tactical complexity with combined armies. It was also more of a Greek/phalanx thing than an Ancient Near Eastern thing, based on how a phalanx worked.

Once the phalanx became only part of a larger army, fighting in the front didn’t work so well. Alexander is able to continue it because he fought on horseback, and could see. In fact, as Graham Wrightson has theorized (“The Nature of Command in the Macedonian Sarissa Phalanx”), most of the Macedonian officers, even of infantry troops, would have been on horseback—again, so they could see. That means they were not in the front. Philip supposedly fought on foot in the front at Chaironeia among the Pezhetairoi (= Hypaspists later). But we know in other situations, he also fought on horseback. He was famously wounded in the thigh by a Thracian pike that went clean through the limb and killed his horse under him.

In any case, ATG fighting in the front seems to have been part of his mystique, but he could pull it off because he was, apparently, a damn good hand-to-hand fighter. (Being a good general and a good fighter are notthe same thing.) But that was when he was young. He was voted the award for personal bravery at Granikos by his men.

By the time he returned from India, if he’d decided to back off a bit from the front, he’d just have been doing what his other generals were already doing. The real question is whether, once his battle-blood was up, he’d have been able to remain out of the middle of the fray. Honestly, I doubt it.

It’s hard to know how much his lung wound affected him, years later. You’d get a better answer from a thoracic specialist about long-term effects of pneumothorax (air in the chest cavity around the lung, collapsing it). Part of the issue is that, while it seems likely he suffered a partially collapsed lung, descriptions of the wound differ somewhat across sources. And collapsed lungs reinflate if the air is removed (which seems to have been the case). Infection would have been the biggest threat, I suspect. Alexander got damn lucky, although it seems his father also healed well, so it was likely hereditary.

Once he was out of the woods from infection, he may have healed relatively well. Certainly, he was able to march through the Gedrosian desert. And if, as king, he would’ve been carefully watched, it also seems that he was marching among them, encouraging them.

I expect his stamina was most affected. Also, as his final illness appears to have been a febrile infection of some sort (typhoid or malaria are best guesses, despite occasional attempts to diagnose him with something weird), if he were having difficulty breathing at the end, a prior pneumothorax may well have complicated his ability to combat it.

Gene and I co-authored an article “Some New Thoughts on the Death of Alexander the Great,” in The Ancient World. In addition, Gene co-authored an article in The New England Journal of Medicine where he worked with several medical doctors to analyze Alexander’s death. He was there to help them understand the historiography (so they didn’t take everything at face value). It’s the most reasoned take on Alexander’s demise that I’ve read, with multiple authors’ input.

#asks#Alexander's wounds#Alexander at Mallia#Alexander's chest wound#death of Alexander#death of Alexander the Great#health of Alexander the Great#Alexander the Great#ancient medicine#Classics#tagamemnon

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think was Alexander greatest skill in the military field?

I am not alone in pointing to his almost uncanny ability to “read the mind” of his opponent. The best generals are mini-psychologists. Yes, a good, disciplined army matters. State-of-the-art military equipment matters. Numbers matter too.

But ALL of these advantages can be undercut if the general doesn’t understand their opponent.

Alexander went into Persia understanding the Persian “war machine.” He knew what the Persians could bring to bear, how they deployed, and how they thought: what they were willing to risk and what they weren’t. A good general may downplay risks when addressing the soldiers, but NEVER to him/herself. Similarly, he understood the Greeks, Thracians, and Illyrians during the campaigns of his first two years.

He didn’t really hit trouble until Baktria and Sogdiana…when he stopped understanding how the locals perceived things. It wasn’t until he figured it out (they wanted a permeable border and recognized kin-ties, so he married into a ruling family), that he was able to march out into India and leave the area pacified behind him (more or less). Once in India, with improved intelligence, he once again showed his ability to out-think Poros.

So yeah, Alexander’s greatest military skill was understanding his opponent, both large scale (strategy) and small scale (tactics for a particular battle). He designed frighteningly apt strategies against (almost) everybody.

That said, while he understood the Persian war marchine, he didn’t really understand the Persian POLITICAL machine, and when he burned Persepolis (almost certainly a staged event, not a drunken frat party gone wrong) to appease his Greek audience, he shot himself in the foot and all-but-permanently alienated the Persian aristocracy. I believe he was working on fixing that, but died before he could succeed—assuming he ever really understood the sheer scope of his error. I’m not sure he did, but Alexander was a smart cookie, so maybe so. I can’t decide because he died too soon.

Yet Persepolis is a mistake I don’t think his father would have made. Whether we can chalk that up to Alexander's young age, or just a different mental space, I’m not sure. But Philip was the superior politician—even young. When we look at what he achieved in his first five years, it’s extraordinary. Of course, he became a shrewd politician in order to stay alive—something Alexander didn’t face.

Needs make the king?

Philip was also visionary when it came to military invention. He completely revamped the Macedonian army. He understood the importance of combined armies (probably from his time in Thebes), and the need for Macedon to develop a viable infantry…then took it a step farther with the pike (sarissa) that was twice the length of a Greek spear. He recognized armament had been lessening to eliminate weight, and used the pike length to continue that trend, reducing shield size. (The aspis, or hoplite shield, is freakin’ heavy!) He also kept a “linking,” more heavily armed and more mobile unit in the Pezhetairoi (=Hypaspists). AND he repurposed the famous Thessalian rhomboid cavalry unit, cutting it in half to create “spear heads” because (unlike the Thessalians) his cavalry only needed to go in one direction: forward. (The value of the rhomboid was to allow Thessalian cavalry units to change direction on a dime by changing the “point.”) Philip invented the “hammer and anvil” which he then used to devastating effect. For that, his cavalry just needed to HIT, not retreat.

Alexander never really changed those tactics. Instead, he—first—continued his father’s “de-noble-ing” of the army by further advancing leaders based on ability, not birth. Philip started it with both the Pezhetairoi (=Hypaspists) and the creation of the Foot. After Gaugamela, Alexander promoted lower officers on ability, not birth. He didn’t dare touch the TOP offices, which continued to be based on birth, but below that…oh, yeah. Advancement democratized (or maybe meritocratized). We can also probably give Alexander superior use of artillery, but I’m not sure how much that’s innovation and how much simple tactical brilliance.

What Alexander did better than Daddy was anticipate his enemy. There’s a lot of talk that Philip handed Alexander a crack army and Alexander got lucky. Yes, Philip did hand Alexander a crack army, but Alexander had to know how to USE it. Philip lost battles. Not a lot, but he did lose some. Alexander didn’t. (We can debate the Marakanda debacle, but that defeat isn’t usually chalked up to him because he wasn’t present.) Where Alexander tended to fail was at the larger, political level.

So the gift Alexander had over Philip was the ability to assess the enemy better, and employ superior tactics (and strategy). Philip, by contrast, excelled his son in political savvy and military innovation.

That’s my assessment of BOTH kings.

#Alexander the Great#philip ii of macedon#Philip of Macedon#military assessments#great generals#asks#military tactics#military strategy#Classics#tagamemnon#ancient Macedon#ancient Greece#ancient Persia#Macedonian history#ancient Greek history

101 notes

·

View notes

Note

Was likely that Alexander and Hephaistion's relationship was a Kathryn Howard/Henry VIII situation, with Hephaistion coerced by his family to become Alexander's confidant/best friend/lover. If he was forced into the relationship, do you think he eventually fell in love with Alexander, or stayed with him for power or because he was too scared to say no? The letter referenced by Aelian implies Hephaistion's considerable sexual influence; although Aelian isn't very reliable, do you think it likely?

Let me explain a little about the Macedonian court to explain why the above is unlikely.

Most folks are familiar with the institution of the Royal Pages, or “King’s Boys” (Basiliskoi Paides). Following NGL Hammond, these boys were c. 14-18. (Although if they had a strict age threshold, it’s hard to say; I suspect Hammond may have been unduly influenced by the Athenian institution of the ephebic military service, which was set at 18 to enter.)

Anyway, in addition to the Royal Pages, we also have a unit called the “Hunters” (Kynegoi), associated with Herakles. What they did is unclear, but seems to have been for boys about 18+, again, upper-class (Hetairoi). Various suppositions have been supplied, but I like Hatzopoulos’s (if I remember right) that they may have functioned rather like a “police force” outside Pella in the countryside of the lowlands, as officer-training. It makes a certain amount of sense, as it would be good experience for young men to learn to think on their own in dangerous situations. It seems like a logical extension of the Royal Pages. Alternatively (or perhaps in addition, as the Kynegoi were not—it seems—a military unit) boys exiting the Pages entered the Pezhetairoi (under Philip) or the Hypaspists (under Alexander): a specialist unit with picked men, especially those “bigger” than average (taller, more bulky). Hephaistion appears to have gone into that unit at some point.

Now, as you can imagine, the competition and back-biting would have been ENORMOUS in either group, to get the attention of the king. But throw the prince into the mix, and it was more so.

In addition to the King’s Boys, royal princes appear to have had a group of young men semi-assigned to them by the king: the syntrophoi. These are picked contemporaries, almost certainly most from the Hetairois class, who were “raised” and educated with him. Meant to be his playmates…and eventually his high-ranking officers. It’s what Curtius refers to when he says Hephaistion was “raised and educated” together with Alexander. He was one of the syntrophoi. Each prince had his own set. We don’t know how many they numbered (probably varied), but IF the gymnasion recently discovered near/at Mieza is any indicator, a prince (especially the one designated as heir) might have as many syntrophoi as the king had Hetairoi: a hundred or so.

(In Dancing with the Lion, I didn’t want to juggle that many boys, but also, I wrote the book before that ginormous gymnasion was found. So while I did have a gymnasion there, it wasn’t anywhere near so large. I’d have reduced the number of boys anyway. There are enough unfamiliar names floating around as it is!)

So I wanted to explain how the court worked, in order to understand how Hephaistion would have entered into Alexander’s personal circle. What his roles might have been.

As a syntrophos of Alexander, Hephaistion’s parents may well have encouraged him to seek royal attention and approval, as that would reflect well on their family. But he wasn’t “chosen” to be Alexander’s best friend. He would have had to fight and elbow his way into that position. Competition was standard for Greek (and Macedonian) culture. Something about Hephaistion attracted Alexander. I doubt it was anything purely sexual. Hephaistion’s isolation at the court, if he was, indeed, of Attic or Ionian extraction, may have made him valuable because he didn’t have lots of family to divide his loyalties (from Alexander). But I’m sure it was more than that.

It’s okay if they just, you know, liked each other. 😊 Not everything is transactional.

We know that Alexander considered him very dear, and seems to have for a while. Sabine Muller and I disagree over when Hephaistion joined Alexander’s court, but even if we follow Sabine’s timeline,* which makes him an adult, not a boy or teen, he appears to have become important to Alexander fairly early.

We don’t know how Hephaistion felt, except by extrapolation. I tend to believe the affection was mutual, not one-sided or opportunistic from Hephaistion. Here’s why:

1) Alexander was a smart guy, and a prince from day one. He would’ve learned to smell sycophancy in childhood. It’s a survival tactic. No matter how good of an actor Hephaistion may have been, long-term, an act would have worn thin. In fact, I think Hephaistion’s importance to Alexander was precisely because it was genuine. Alexander got lucky and found a true best friend—a rare thing for kings.

2) As for why they got along… IME, smart people in positions of authority (who are not narcissistic**) may put up with and find use for yes-men/women for a while, especially in “underling” positions. But they grow tired of them long-term. Hephaistion and Alexander were close for years. And, if I’m right and they’d met by Mieza (if not before), they were friends, even best friends,*** for 19 years. That’s longer than most modern marriages.

Therefore, I’ve always seen Hephaistion as someone uniquely able to keep up with Alexander, and who was honest with him (something Curtius asserts). In short, Alexander not only found that rare thing—a true best friend—he found one smart enough to match him, but who didn’t elicit a response from his over-developed “competition” gene.

As I’ve said before, all of that is why I find their story so compelling. In a competitive, calculating world, it seems refreshingly real.

---------------

*“Hephaistion,” Lexicon of Argead Macedonia, Heckel, Heinrichs, Muller, Pownall, Frank and Timme, 2020.

**Alexander was not a narcissist. I’ve seen him accused of it, especially lately with Trump as a model, but narcissists are rarely so successful (their own delusions prevent it), and he just doesn’t tick enough DSM diagnostic boxes, for me.

***Remember that, for the Greeks, philos was a higher position than erastes or eromenos.

#Alexander the Great#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Syntrophoi#Hetairoi#Hypaspists#ancient Macedonia#ancient Greece#Macedonian court#Royal Pages at Macedonian Court#asks

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I have some questions following the ask you answered about Pausanias (I apologize in advance for the length of the question, they're just too many)

What was considered "too old" for a lover in ancient Macedonia? What was the normal age for the King's lovers to be?

And, like anon asked, do you think Pausanias was in love with Phillip or was it all about the status?

Was it common for kings to be in love, or better said, to have a close relationship with his lovers (outside the bedroom, I mean)? Or how did those types of relationships worked? Do we know how Phillip and Pausanias' relationship was like, before he changed him for the other Pausanias and after the party incident?

And a side question, something that was never clear for me, did Phillip also rape Pausanias at the party?

First, general Greek ideals (note ideals, not necessarily reality) tended to paint the eromenos as ranging from pre-teen to late teens. Supposedly, the ability to grow a beard marked the end of one’s attraction as a boy (eromenos) and the transition to being the erastes (lover). There’s a brief window where one could (in theory) be the eromenos to an older lover, but erastes to a younger beloved. There’s no hard-and-fast age, as people mature at different rates. So, for instance, in the novels, Hephaistion isn’t even 16 but can grow his beard. Alexander, at almost 19, is shaving because his beard is so patchy. Again, the younger age is similar; some matured sooner into pre-teen/early teen, although on pottery, we see some eromenoi who look (disturbingly) like older children. Most are clearly younger teens. The Romans, btw, were squicked by Greek pederasty, although it was the “free born boy” part that bothered them. The sexual use of slave children was shrugged off. It was more about status than age.

Yet there is a reason it was called Greek pederasty in the ancient sources, although that’s not a term we use much now except in very specific circumstances, as it tends to bring to mind modern child sexual abuse. There were two big differences. First, the very public nature of the courting—unlike the concealed coercion of abuse victims—made it difficult to conceal inappropriate behavior. Second, the eromenos had the power in the relationship to turn down the courting altogether, or to say “yes” or “no” to sexual activity. (Note below the young man grabbing the wrist of the older man, to stop him. Although it’s been pointed out he stops the hand to his chin [a courting gesture], but not the one reaching for his dick!)

Making parallels to women dating in the middle 20th century aren’t entirely off-base. It was the boy who asked out the girl, who could turn him down. And the girl was tasked with saying “no” to male advances because “he couldn’t control his passions.” Yet there was a problem of “no” being ignored (e.g., rape), or more powerful suitors coercing compliance. We’re back to the difference between the ideal and the real.

This is why I get really BOTHERED by the whole romanticizing of Antinoös and Hadran as gay icons. Antinoös was about 12 when Hadrian picked him up and took him to Italy, and Hadrian was already emperor. You don’t tell the emperor no, especially not one known for his short temper. Maybe Antinoös was a social climber and adored his position as the Hellenizing Hadrian’s eromenos, or he at least made the best of a bad situation. But we have nothing at all to tell us his thoughts, and some really disturbing/murky gossip surrounded his death in the Nile. Guys, it’s NOT a love story, and Antinoös was a victim.

That said, and however predatory Hadrian’s behavior may have been, most erasteis were no more plotting to seduce the cute 11-year-old in the palaistra than the average young man intended to lure his date into the backseat of his 1956 Chevy and rape her. But those people existed, both in the recent past and the distant past, and we shouldn’t forget it.

Now, I use the Hadrian parallel as the same issue would apply to the Macedonian king. In Becoming, Hephaistion thinks to himself that, if Philippos were to make a move on him, he’d have to consider carefully his reaction, as one didn’t just turn down the king.

But we have very little (e.g., virtually NO) evidence for what Philip’s relations with his lovers was like. No doubt, it varied. We have a hint that coercion may have been the case with kings, or at least a sense of opportunism. Philip wasn’t the first Macedonian royal killed by an eromenos. Archelaos was too. We’re told that, while out hunting, he was speared by a Page (or former Page) who was a Thessalian “prince” (e.g., a member of one of the four leading families). The reason? The boy had been promised that Archelaos would help him/his family regain their political position in return for his sexual favors. But that didn’t happen, and so the boy felt used by Archelaos, his timē besmirched, so he killed Archelaos. This prior example is often cited when we talk about what happened to Philip, to understand what may have been going through Pausanias’s head as motivation.

We also know that Pausanias didn’t want to step down at Philip’s lover, although why isn’t at all clear. Did he love Philip, or think he did? Or was he loathe to give up the status such a position gave him? Or both? Or maybe there was some other reason we aren’t told. Pausanias appears to have been a member of the ruling family in Orestis; did he (like the Thessalian earlier) want something for his family, and was angry at being replaced because he didn’t have it (yet). Any of those is possible. We just lack any data whatsoever. We can say that, if Philip and Alexander of Epiros were lovers as Justin suggested, Philip did help Alexander to his throne. Justin implies he meant to do it all along, but that’s Justin’s love of scandal.

One of the jobs of an erastes is to shepherd his eromenos into adult male culture, such as the symposion and gymnasion. But also to further his general future, including into politics if of the higher classes. That’s part of what lies behind the Page’s resentment of Archelaos. By contrast, it looks as if Philip did perform that job, at least with regard to Alexander, and perhaps for his other eromenoi.

Philip had nothing to do with the party where Pausanias was raped. He was later targeted by Pausanias because he didn’t punish Attalos as Pausanias wanted. He only promoted Pausanias into the Pezhetairoi (the unit later called Hypaspists by Alexander). It’s called “bodyguard” (somatophylax), but shouldn’t be confused with the 7-man unit. The Pezhetairoi were the “bodyguard,” small /b/, for the king in combat. Philip then sent Attalos overseas with Parmenion. This might look like a promotion as the uncle-in-law of the king, but it smells (to me) like being kicked upstairs and got out of Pella. Nonetheless, it seems to have been that “promotion” of Attalos that set off Pausanias, who then targeted Philip as the un-just judge.

#erastes#eromenos#Greek homoeroticism#Greek male-male courting#Philip of Macedon#Pausanias of Orestis#Pausanias#Alexander of Epiros#Hadrian#Antinoos#Hadrian and Antinoos#asks

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

You once said that Hephaistion was kept away from combat. Do you still believe this?

Love your blog xx

Thank you (on the blog).

I do, however, want to make an extremely important clarification because people keep getting it confused.

Alexander seems to have kept Hephaistion away from combat command. He didn’t keep him away from combat.

I make the distinction because command ability, strategic ability, and fighting ability are not the same things. They shouldn’t be conflated.

Alexander appears to have had all three, which is actually kinda rare. A person can be a very good fighter, but not a terribly good strategist, or commander. I actually address this in Dancing with the Lion, where Hephaistion is presented as a very good fighter, but he doesn’t like commanding. Alexander even observes that the best fighters usually aren’t the best commanders because they focus on their fighting skill to the exclusion of the bigger picture.

The fact Hephaistion fought “first” among the Hypaspists at Gaugamela suggests he was at least a decent fighter, and possibly a really good one. It might also be independent verification that he was a tall or big man. We’re told Philip specifically looked for big men who were good fighters for the Pezhetairoi, which is the precursor to the Hypaspists (same unit, different name).

I’ll be revisiting his career in my monograph, but the chapter “The Cult of Hephaistion” in Responses to Oliver Stone’s ‘Alexander’ is the examination of his career that I have currently in print. In it, I outline his commands as we have them recorded in the sources.

#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Alexander the Great#Hephaistion's career#ancient Macedonia#Alexander's army#military history#Classics#asks

15 notes

·

View notes