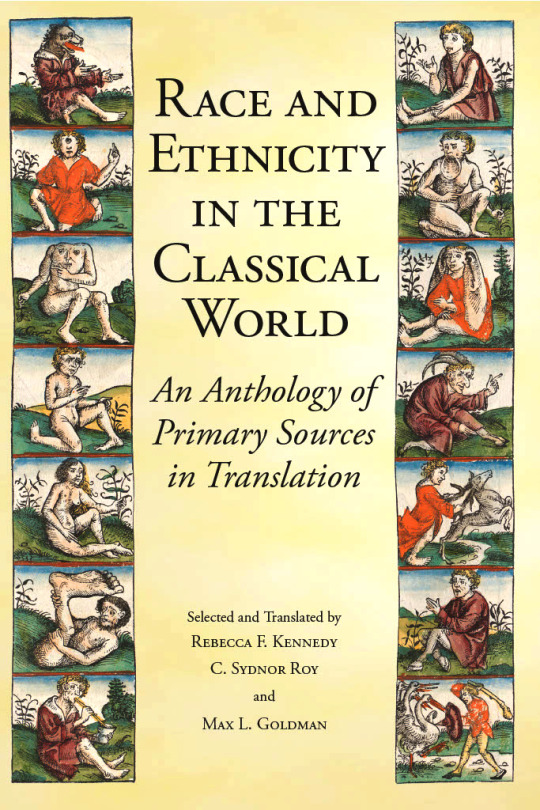

#ancient Macedonian politics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Kind of related to the ask on Cleopatra, and even your one way earlier on Krateros… What do you think Alexander would’ve been like if he weren’t an Argead, and instead fated to be a Marshal for whoever else was meant for the throne? Do you think he would’ve been rebellious? Or cutthroat and ambitious like Krateros? Or more-so disciplined and loyal? I kind of see him as a combination of all three because I don’t peg Alexander for someone who can be contained, lol.

To answer this, we must keep in mind that, for the ancient Greeks, belief in divine parentage for certain family lines was very real. A given family and/or person ruled due to their descent. The heroes in Homer had divine parents/grandparents/great-grandparents. This notion continued into the Archaic period with oligarchic city-states ruled by hoi aristoi: “the best men.” (Yes, our word “aristocrat” comes from that.) Many of these wealthy families claimed divine ancestry; that’s why they were “best.”

In the south, this began to break down from the 5th century into the 4th. But not in Macedonia, Thessaly, or Epiros. In fact, even by Alexander’s day, many Greek poleis remained oligarchies, not democracies. And in democracies, “equality” was reserved for a select group: adult free male citizens. Competition (agonía) was how to prove personal excellence (aretȇ), and thereby gain fame (timȇ) and glory (kléos). All this was still regarded as the favor of the gods.

Alexander believed himself destined for great things because he was raised to believe that, as a result of his birth. Pop history sometimes presents only Olympias as encouraging his “special” status. But Philip also inculcated in Alexander a belief he was unique. He (and Olympias) got Alexander an Epirote prince as a lesson-master, then Aristotle as a personal tutor. Philip made Alexander regent at 16 and general at 18. That’s serious “fast track.” Alexander didn’t earn these promotions in the usual way; he was literally born to them.

If Alexander hadn’t been an Argead, that would have impacted his sense of his place in the world no less than it did because he was an Argead. What he might have reasonably expected his life path to take would have depended heavily on what strata of society he was born into.

Were he a commoner, in the Macedonian military system, his ambitions might have peaked at decadarch/dekadarchos (leader of a file). Higher officer positions were reserved for aristocrats through Philip’s reign. With Alexander himself, after Gaugamela, things started to change for the infantry, at least below the highest levels (but not in the cavalry, as owning a horse itself was an elite marker). Under Philip, skilled infantry might be tagged for the Pezhetairoi (who became the Hypaspists under ATG). But Alexander himself wouldn’t have qualified because those slots weren’t just for the best infantrymen, but the LARGEST ones. (In infantry combat, being large in frame was a distinct advantage.) So as a commoner, Alexander’s options would have been severely limited.

Things would have got more interesting if he’d been born into the ranks of the Hetairoi families, especially if from the Upper Macedonian cantons.

Lower cantons were Macedonian way back. If born into those, he (and his parents) would have been jockeying for a position as syntrophos (companion) of a prince. Then, he’d try to impress that prince and gain a position as close to him as possible, which could result in becoming a taxiarch/taxiarchos or ilarch/ilarchos in the infantry or cavalry. But he’d better pick the RIGHT prince, as if his wound up failing to secure the kingship, he might die, or at least fall under heavy suspicion that could permanently curtain real advancement.

That was the usual expectation for Lower Macedonian elites. Place as a Hetairos of the king and, if proven worthy in combat, relatively high military command. Yes, like Krateros. But hot-headedness could curtail advancement, as apparently happened to Meleagros, who started out well but never advanced far. The higher one rose, the more one became a potential target: witness Philotas, and later Perdikkas. In contrast, Hephaistion was Teflon (until his death). Yet Hephaistion’s status rested entirely on his importance to Alexander. And he probably wasn’t Macedonian anyway; nor was Perdikkas from Lower Macedonia, for that matter.

The northern cantons were semi-independent to fully autonomous earlier in Macedonian history. Their rulers also wore the title “basileus” (king); we just tend to translate it as “prince” to acknowledge they became subservient to Pella/Aigai. Philip incorporated them early in his reign, and I think there’s a tendency to overlook lingering resentment (and rebellion) even in Philip’s latter years. Philip’s mother was from Lynkestis, and his first wife (Phila) from Elimeia. Those marriages (his father’s and his) were political, not love matches.

Similarly, Oretis was independent, and originally more connected to Epiros. Note that Perdikkas, son of Orontes, was commanding entire battalions when he, too, was comparatively young. Like Alexander, he was “born” to it. Carol King has a very interesting chapter on him in the upcoming collection I’m editing, one that makes several excellent points about how later Successors really did a number on Perdikkas’s reputation (and not just Ptolemy).

If Alexander had been born into one of these royal families from the upper cantons, quasi-rebellious attitudes might be more likely. Much would depend on how he wanted to position himself. Harpalos, Perdikkas, Leonnatos, Ptolemy…all were from upper or at least middle cantons. They faired well. For that matter, Parmenion himself may have been from an upper canton and decided to throw in his hat with Philip.

By Philip’s day, trying to be independent of Pella was not a wise political choice, but if one came from a royal family previously independent, we can see why that might be seductive. Lower Macedonia had always been the larger/stronger kingdom. But prior to Philip, Lynkestis and Elimeia both had histories of conflict with Macedonia, and of supporting alternate claimants for the Macedonian throne. At one point in (I think?) the Peloponnesian War, Elimeia was singled out as having the best cavalry in the north. Aiani, the main capital, had long ties WEST to Corinthian trade (and Epirote ports). It was a powerful kingdom in the Archaic/early Classical era, after which, it faded.

So, these places had proud histories. If Alexander had been born in Aiani, would he have been willing to submit to Philip’s heir? Maybe not. But realistically, could he have resisted? That’s more dubious. By then, Elimeia just didn’t have the resources in men and finances.

I hope this gives some insight into how much one’s social rank influenced how one learned to think about one’s self. Also, it gives some insight into political factions in Macedonia itself. As noted, I believe we fail to recognize just how much influence Philip had in uniting Lower and Upper Macedonia. Nor how resentment may have lingered for decades. I play with this in Dancing with the Lion: Rise, as I do think it had an impact on Philip’s assassination.

(Spoiler!)

Philips discussion with his son in the Rise, and his “counter-plot” (that goes awry) may be my own invention, but it’s based in what I believe were very real lingering resentments, 20+ years into Philip’s rule.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Alexander alternate history#ancient Macedonia#ancient Macedonian politics#Upper Macedonia#Lower Macedonia#Macedonian internal politics#Philip II of Macedon#ancient history#Classics

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cratesipolis in the Ancient Sources

314 BCE: "Polyperchon's son Alexander, as he was setting out from Sicyon with his army, was killed by Alexion of Sicyon and certain others who pretended to be friends. His wife, Cratesipolis, however, succeeded to his power and held his army together, since she was most highly esteemed by the soldiers for her acts of kindness; for it was her habit to aid those who were in misfortune and to assist many of those who were without resources. She possessed, too, skill in practical matters and more daring than one would expect in a woman. Indeed, when the people of Sicyon scorned her because of her husband's death and assembled under arms in an effort to gain their freedom, she drew up her forces against them and defeated them with great slaughter, but arrested and crucified about thirty. When she had a firm hold on the city, she governed the Sicyonians, maintaining many soldiers, who were ready for any emergency."

— Diodorus Siculus (Book XIX)

308 BCE: "At this time, while Ptolemy was sailing from Myndus with a strong fleet through the islands, he liberated Andros as he passed by and drove out the garrison. Moving on to the Isthmus, he took Sicyon and Corinth from Cratesipolis."

— Diodorus Siculus (Book XX)

308 BCE: "Cratesipolis, who had long fought in vain for an opportunity of betraying Acrocorinth to Ptolemy, having been repeatedly assured by the mercenaries, who composed the guard, that the place could be defended, applauded their fidelity and bravery; however, said she, it may be wise to send for reinforcements from Sicyon. For this purpose, she openly sent a letter of request to the Sicyonians; and privately an invitation to Ptolemy. Ptolemy's troops were dispatched in the night, admitted as the Sicyonian allies, and put in possession of Acrocorinth without the agreement or knowledge of the guards."

— Polyaenus: Stratagems

307 BCE: "But on learning that Cratesipolis, who had been the wife of Polyperchon's son Alexander, was tarrying at Patrae, and would be very glad to make him a visit (and she was a famous beauty), [Demetrius the Besieger] left his forces in the territory of Megara and set forth, taking a few light-armed attendants with him. And turning aside from these also, he pitched his tent apart, that the woman might pay her visit to him unobserved. Some of his enemies learned of this, and made a sudden descent upon him. Then, in a fright, he donned a shabby cloak and ran for his life and got away, narrowly escaping a most shameful capture in consequence of his rash ardour. His tent, together with his belongings, was carried off by his enemies."

— Plutarch (Life of Demetrius, 1.9.3)

#Cratesipolis#I wish we knew more about her :(#Ancient sources do tell us quite a bit but only within a very brief and very specific time-bracket#We know nothing about her origins; early life; marriage; her deal with Ptolemy; or what happened to her after her meeting with Demetrius#It's like she suddenly appears in 314 and suddenly vanishes in 307 (she's literally swallowed up by history...)#But despite the brevity of information about her she is remarkable. As per what I understand:#She's the first known non-royal Macedonian woman to assume the role of a political and military leader and command troops#She holds the record as the Macedonian woman who was able to retain control of her troops for the longest time (from 314 to at least 307)#It's also striking that Cratesipolis doesn't seem to have been ruling behalf of a male relative (son/husband/nephew) but in her own right#greek history#macedonian history#hellenistic period#ancient history#ancient greece#women in history#my post

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Re the depictions of cleopatra as black, the whole statue or cameo being black doesn’t automatically equal the individual being depicted as black. There are Egyptian statues that are all sandstone, but they’re not meant to depict colour either, of the skin or otherwise. If they were, people could make the same argument that the people in the sandstone statues are being depicted as white, which we also know is not true. These depictions are simply not ‘colored in’ for lack of a better term, so they’re not really good examples regarding black depictions of cleopatra

"Now, your question about whether or not it's OK or not OK to portray her as Black - Cleopatra manipulated her own image all the time. She had one face for her coinage and multiple faces for her coinage that went out amongst the Greeks in the Mediterranean and the Romans. And she had a different face that she wore in her Egyptian iconography. So she herself was manipulating her own image for audience. So whether we do this in our own entertainment industry or not seems to be fitting in with her own iconographic tradition..." — Dr. Rebecca Futo Kennedy, PhD, The Modern Racial Politics of Cleopatra

More Videos: Black Africans in the Ancient Mediterranean

"History teaches us that Macedonia (ancient Macedon) was a region of northern Greece, whose people were of a tribe that settled there by the seventh century B.C. and who were similar in language and outlook to the Ionians, Dorians and Aeolians, the rest of the Greek tribes. Macedon and Macedonians were never in all their history known as a separate country or a distinctive ethnic group. It was simply a region in ancient Greece, inhabited by Greeks.

The Slavs, on the other hand, made their appearance in history sometime between A.D. 570 and 630. They never used the name Macedonia, not even as a geographic term. They mentioned it for the first time during the 19th century, when their ethnic awareness was taking place.

Macedonians appear as a separate ethnic group (race) in 1923 following a decision made at the Third Communist International. The independent "nation of Macedonia" was established in 1944, after a decision by Marshal Tito; the Slavs were baptized into "Macedonians," and a new race was created.

A census conducted in the region in 1940, a few years before the Slavs were baptized "Macedonians," listed only Slavs, Bulgarians and Greeks. There were no registered Macedonians. A fourth ethnic group, either named or nicknamed "Macedonians," was completely unknown. Thanks to Tito's efforts, in the 1956 census, 861,000 declared themselves "Macedonian." KOSTAS G. MESSAS Denver, Sept. 18, 1991"

New York Times Article: History Doesn't Know 'Ethnic Macedonians'

#ancient egypt#ptolemaic egypt#hellenistic period#cleopatra#macedonia#macedonians#greece#greeks#race#ethnicity#mediterranean#history#identity#politics

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Herakleia Lynkestis

Herakleia Lynkestis (Heraclea Lyncestis; Ἡράκλεια Λυγκηστίς) was a city in the ancient kingdom of Macedon not far from modern Bitola, founded c. 358 BCE by Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE) as a governing centre for his new expansions around the older capital, Aigai, east of his current capital, Pella, to secure his western border from further Illyrian invasions.

Although Philip chose the location for strategic reasons, his decision may have been influenced by his mother, Queen Eurydice I of Macedon (c. 410-369 BCE), being originally from the family ruling the Lynkestian tribe. Philip named the new city after the legendary hero Herakles (Hercules), not least because his family of Macedonian rulers, the Argeads, claimed this son of Zeus was their founding father. Herakleia Lynkestis was first built as a defensive citadel. Later developments may not have added much to its expansion but they turned the city into a significant centre of trade and administration.

After the Roman conquest of the Greek world in 146 BCE, Herakleia Lynkestis became a centre for local magistrates, perhaps reflecting the legacy of its most notable figure, Queen Eurydice (whose name means "sound judgment"), and the public reverence for Nemesis, the goddess associated with exacting justice. Thanks to its advantageous location along the so-called Roman highway of the Balkans, Via Egnatia, the city became a popular hub hosting visitors, traders, travelers, and scholars, who were drawn to its vibrant forum, temples (later basilicas), palaces, and theatre.

Via Egnatia, 146 BCE to c. 1200 CE

Nathalie Choubineh (CC BY-NC-SA)

Lynkestis

Lynkestis, meaning "the place of lynx(es)", was a region east of Lake Prespa in Upper Macedonia, covered with wooded mountains and fertile plains. It was probably named after the earliest tribe attested in written history that inhabited there, the Lynkestai (the Lynkestians). However, it is also possible that the migrant community that finally settled in the region began to call their location by the name of its most common beast, and they were later known by this name.

Archaeology, on the other hand, reveals that the Lynkestis region might have been inhabited long before what ancient writers could tell. The earliest evidence indicating the presence of certain local tribes dates back to the end of the Mycenaean era in the Late Bronze Age, namely c. 1200-1100 BCE. Archaeological finds include pieces of typical Macedonian matt-painted vessels with concentric circles alongside foreign artifacts from distant regions such as Cyprus. This, coupled with Macedonian-style ware found in Boetia, suggests extensive and dynamic trade networks and cultural interactions within the region.

Historical records about the Lynkestians are sparse, and the existing pieces suggest that their community proper, under a verifiable basileus (monarch), began to form no earlier than the mid-7th century BCE. According to the 1st-century BCE Greek geographer Strabo, the local tribes of Upper Macedonia were often ruled by foreigners, who, in the case of the Lynkestians, were descendants of a Corinthian clan, the Bacchiads (7.7.8). They took their name from Bacchis (r. 926-891 BCE), a later successor of Aletes, who was the last Dorian king of Corinth (overthrown in 1074 BCE). The Bacchiads continued to rule Corinth until 784 BCE, when their final king, Telestes, was assassinated by two members of a different Bacchiad faction, Arieus and Perantas (Herodotus 5.92; Pausanias 2.4). Following this regicide, Corinth adopted an oligarchic system of government led by the prytaneis (executive authorities), a polemarchos (commander-in-chief), and a council of elders.

Bronze Figurine of Infant Hercules Killing Serpents

Nathalie Choubineh (CC BY-NC-SA)

Politically, the rule of a minority group rarely receives positive commentary in ancient texts, and the oligarchy of the Bacchiads is no exception. Herodotus (5.92B) describes the Bacchiads as harsh and autocratic, for example, restricted to marrying within their own clan. However, one of their women, Labda, was born with crooked legs and could not find a husband among the Bacchiads. She was eventually given to an outsider from Petra, although this was likely a different city from the famous one in modern-day Jordan. When Labda gave birth to a son, the Oracle at Delphi prophesied that he would become a great leader. Fearing this, the Bacchiads sought to kill the child. Nevertheless, he survived when his mother hid him in her private chest, from which he got his name, Cypselus, meaning the "chest" or "box". In 655 BCE, Cypselus successfully overthrew the Bacchiad oligarchy and expelled them from Corinth. The exiled Bacchiads moved to Corcyra (modern-day Corfu), and some chose to travel further, eventually becoming rulers of the Lynkestian tribe in Upper Macedonia.

Continue reading...

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gaza by Any Other Name

Since Trump dropped his epic relocation plan, thousands of articles have been written about its pros and cons, focusing on logistics, morality, legality and so forth. One issue remained neglected. I’d like to address it.

For thousands of years, Gaza has been a magnet for misfortune. Time and again, it picked up fights too big for it and didn’t know when to stop. Through the centuries, its enemy punished it terribly, leaving behind smoldering ruins, mass graves, and generations of people caught in the crossfire.

The Babylonians, the Egyptians, the Macedonians, the Romans, the Arabs, the Crusaders, the Mongols, the Ottomans, the British, the Israelis—almost every major player in the region has taken a turn at leveling the place. If cities had astrological charts, Gaza’s would read “unrelenting chaos with occasional firestorms.”

Former U.S. President Donald Trump put it well in his signature blunt style:

"Gaza Strip... has been a symbol of death and destruction for so many decades and so bad for the people anywhere near it, and especially those who live there and frankly who've been really very unlucky. It's been very unlucky. It's been an unlucky place for a long time. Being in its presence just has not been good."

And, you know what? He’s not wrong. Gaza’s history suggests something beyond just bad leadership, bad geography, or bad geopolitics. It suggests a cosmic-level losing streak. Here are just a few highlights from its long, unlucky history:

601 BCE – The Babylonians razed Gaza as part of their conquest of the Levant. The city’s people were either slaughtered or exiled.

332 BCE – The city held out for two months against Alexander the Great, which made him furious. When his troops finally broke through, they massacred all the men, sold the women and children into slavery, and replaced them with foreign settlers.

96 BCE – The Jewish Hasmonean king, Alexander Jannaeus, captured Gaza and slaughtered its inhabitants wholesale and burned many of its landmarks. The survivors were forced to choose between conversion to Judaism and exile to Egypt. Once again, Gaza had to start from scratch.

66 CE – Gazan Jews rose up against the Roman occupiers. The Romans retaliated with their usual efficiency—by killing nearly every Jew in the city.

793–796 CE – An ancient feud between two Arab tribal confederations turned into a full-blown civil war, with Gaza caught in the middle. By the time Abbasid authorities put an end to the fighting, Gaza was entirely depopulated.

1100 CE – The Crusaders, fresh from their conquest of Jerusalem, took Gaza and, in typical Crusader fashion, slaughtered most of the population.

1260 CE – The Mongols under Hulagu Khan stormed Gaza, massacred most of the residents, and left the city a field of bones and rubble.

1917 – During World War I, Gaza was a key defensive position for the Ottoman Empire. The British, determined to break through, have politely destroyed the city. After two failed assaults, they finally captured Gaza—but only after leveling much of it in the process.

2023 – Since the creation of Israel, Gaza has been at the center of near-constant fighting. The Suez Crisis, the Six-Day War, multiple intifadas, Israeli airstrikes, and Hamas-led conflicts have kept Gaza in a perpetual cycle of war and reconstruction. On October 7 it launched the war that might well prove to be its undoing.

Yes, Gaza has been destroyed so many times it’s a wonder anyone bothers rebuilding it. Or, in the words of Trump:

“It should not go through a process of rebuilding and occupation by the same people that have really stood there and fought for it and lived there and died there and lived a miserable existence there. Instead, we should go to other countries of interest with humanitarian hearts, and there are many of them that want to do this and build various domains that will ultimately be occupied by the million Palestinians living in Gaza, ending the death and destruction and frankly bad luck."

Maybe it’s time to try something radical—like changing its name.

This wouldn’t be the first time a place has undergone a rebranding in an attempt to shake off a history of conflict and misfortune. One of the most famous examples is Judea.

Time after time, the Romans crushed Jewish uprisings with extreme brutality. To punish the rebellious nation, Emperor Hadrian renamed the province "Syria-Palestina" after the ancient enemies of the Jews, and—just like that—the Jewish revolts stopped for centuries. Coincidence? Maybe. But it certainly marked the end of the region’s long cycle of uprisings.

Other places have benefited from a fresh name, too.

Take Constantinople—a city that had been the target of endless sieges and invasions for over a thousand years. The Crusaders sacked it. The Ottomans conquered it. But after the Turks renamed the city “Istanbul,” things turned around. Today, it’s a thriving metropolis with a booming economy and exactly zero crusaders setting fire to it.

Then there’s New York, originally called New Amsterdam when it was a Dutch colony. The English took it over in 1664, gave it a new name, and the place went on to become the financial and cultural capital of the world.

Ho Chi Minh City, formerly known as Saigon, saw a dramatic shift in its trajectory after its renaming. Saigon had been the capital of South Vietnam during the Vietnam War, a city synonymous with war, division, and the fall of a government. But after reunification, it was given a new name and gradually transformed into Vietnam’s economic hub.

Gaza, too, could use a break.

Every time its name is mentioned in the news, it’s in the context of destruction, war, or humanitarian catastrophe. No one ever says, “I just got back from my vacation in Gaza—great beaches, wonderful food, fantastic hotels!” That’s because, despite having all those things (really! Read about Gaza before the war, it wasn’t nearly as bad as people imagine) the name Gaza has been weighed down by millennia of bloodshed and decades of barbaric Hamas rule.

A new name could symbolize a new beginning.

Of all the proposed actions, it’s the cheapest and safest one. When you’ve been through thousands of years of bad luck, what’s one more small change?

Worth a shot, don’t you think?

URI KURLIANCHIK

FEB 16

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Homosexuality in History: Kings and Their Lovers

Hadrian and Antinous Hadrian and Antinous are famous historical figures who epitomize one of the most well-known homosexual relationships in history. Hadrian, the Roman Emperor from 117 to 138 AD, developed a close friendship with Antinous, a young man from Egypt. This relationship was characterized by deep affection and is often viewed as romantic. There are indications of an erotic component, evident in Hadrian's inconsolable reaction to Antinous's tragic death. Hadrian erected monuments and temples in honor of Antinous, underscoring their special bond.

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion The ancient world was a time when homosexuality was not as taboo in many cultures as it is today. Alexander the Great and Hephaestion are a prominent example of this. Alexander, the Macedonian king from 336 to 323 BC, and Hephaestion were best friends and closest confidants. Their relationship was so close that rumors of a romantic or even erotic connection circulated. After Hephaestion's death, Alexander held a public funeral, indicating their deep emotional bond.

Edward II and Piers Gaveston During the Middle Ages, homosexuality was not as accepted in many cultures as it is today. The relationship between Edward II and Piers Gaveston was marked by rumors and hostilities, demonstrating that homosexuality was not always accepted in the past. Their relationship is believed to have been of a romantic nature, leading to political turmoil and controversies. Gaveston was even appointed Earl of Cornwall by Edward, highlighting their special connection.

Matthias Corvinus and Bálint Balassi In the Renaissance, there was a revival of Greco-Roman culture, leading to increased tolerance of homosexuality. Matthias Corvinus ruled at a time when homosexuality was no longer illegal in Hungary. The relationship between Matthias Corvinus and Bálint Balassi is another example of homosexuality being accepted during this period. Matthias Corvinus had a public relationship with Bálint Balassi, a poet and soldier. Their relationship may have been of a romantic nature, as Balassi was appointed as the court poet, and it had cultural influence.

These relationships between the mentioned kings and their lovers are remarkable examples of the long history of homosexuality in the world. In many cultures of antiquity and the Middle Ages, homosexuality was not as strongly stigmatized, demonstrating that homosexuality was not always rejected in the past.

Text supported by Bard and Chat-GPT 3.5 These images were generated with StableDiffusion v1.5. Faces and background overworked with composing and inpainting.

#gayart#digitalart#medievalart#queer#lgbt#history#gayhistory#KingsLovers#manlovesman#powerandpassion#gaylove

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xenia, often translated as the laws of hospitality, was really important in the stories of Greek Mythology.

It wasn't just on the host. The rules also applied to the guests.

Xenia was basically what allowed for nobles of different cities to network with each other.

Greece, you may have noticed, is mountainous and rocky. If you're ruling with ancient technology the easiest way to set up a government is to put a fortress on a hill and rule everything you can physically see from there. Maintaining an empire of any kind is difficult. Frankly, idk how the Macedonians and Romans pulled it off.

But. Even though they all have different governments there's a general shared culture in the area. Not identical, but they all worship the same gods, speak roughly the same language, and have similar moral codes. There's a specific type of guy who is a noble-born Hellene. A free citizen of a city. A guy who owns property. A guy who is Greek. You know a Greek when you come across one.

So when the noble-born Hellenes are traveling around they are guaranteed safe lodging by the laws of hospitality. They help their host, their host helps them, they eat together, they work together, and this is where the inter-city and inter-regional politics happen. These dinner conversations are where alliances are struck. These rules are what makes travel safe. They keep you from being attacked by your host and keep you from sleeping on the ground.

The laws of hospitality really do kind of hold the entire society together by keeping all of these different city-states socially connected to each other. This is the real reason you scare each other with stories of Zeus striking down people who break the rules of xenia. Because if you turn away strangers you turn away potential allies and everyone around here is stuck in a seemingly never-ending struggle for local influence. Zeus is both a god of politics and a god of strangers. If you mess with friendly strangers, you're betraying your chief god and your entire political system.

625 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pluto might be in Aquarius

But that's only half the story.

Now I'm not one to believe only the planets inspire change in people but the environment they live in, their disposition and their current state of being impacts them just as much. Astrology without the consideration of culture and context is just astronomy. It has the body but not the soul.

I start with that because of all the current global happenings. I understand the importance of spiritual and religious practices, and they don't exist in a bubble of their own. It is highly related to the cultural movements and ethnic practices of a region. If we are going to be honest religions/spirituality would not exist with out those cultural foundations. Literally there would be nothing if ethnic and cultural differences didn't play a role.

Hoodoo wouldn't exist if African Americans didn't. The Greek Pantheon wouldn't be a thing if the ancient Greeks didn't interact with the Egyptians, Nubians and Macedonians. And it should be very well known the Romans stole their whole flow and rebranded. The same Romans who took Christianity and set the foundation for the many versions we see today.

I say all that because I've noticed a lack of connecting between the social/political climate, traditions and belief systems. We can't pretend that Vedic astrology isn't an actual part of Hinduism because it wouldn't exist if Hinduism wasn't here. And Hinduism is the result of two very different populations interacting with one getting colonized and pushed south and the other needing a system/ belief to justify it. We can't pretend that tropical astrology isn't a more Eurocentric method because the signs, planets and their meanings are not the same outside of Western/Eurocentric ideology. In fact it's heavily based off of Roman and Greek interpretations, the base of Western Society as a whole.

I'm not going to pretend that Pluto moving into Aquarius is the only reason why we suddenly "see" more social changes, more standoffish behavior, more coldness to our fellow human. All Aquarius is doing is putting it on the internet. It sent a tweet out and we all saw it. These issues aren't a magical happening, they are the result of centuries of bs pilling up. Of cultures merging in ways that weren't possible before modern technology. Of colonization. Imperialism. Chattel Slavery. The Arab Slave trade. Ethnic cleansings.

People weren't passive before the shift into Aquarius, people were ignoring it. It's really easy to do when you have no personal reason to care, in fact it's probably something all humans can relate to on one topic or another. Trust me I was heavily into activism spaces a decade ago, everything being talked about in media now was talking about then. It was talkes about when my parents were growing up in the 60s. My grandparents in the 20s/30s and so on. Aquarius just put it in our faces (again, and will continue to do so) and said "now what? ".

I want people to not just lean in to spiritual/religious practices because they are popular but to look into the actual meanings they have. I want people to understand that yes you can be spiritual/religious and your ethnic background does impact how you practice. I want people to understand these changes we see in France (they lost their standing in Africa, literally all their former colonies told it to cope, and that's leading to their collapse), South Korea (this is not the first, and sadly won't be the last time, power has been abused under the name of "anti communism", in fact ask South East Asians how they treated there and you'll see this was going to happen), the United States (a country founded on genocide and racism isn't going to magically be less of those because a Black woman got to run for office) etc aren't solely a shift in the Star positions.

I see people point out the French Revolution happened the last time Pluto was in Aquarius (but they also had lost all the land in the US and Haiti told them to fuck off, so it wasn't just not eating cake, it was the lack of slave labor to fund their empire). Or America getting it's freedom (Britain was getting close to abolishing chattel slavery (again free labor, people hate to lose their free labor), the Irish and Scottish were also giving the English a hard time, they had to pick between the people next door or the ones over the Ocean). At that time it was the lack of free labor that pushed those movements, yeah everyone didn't have slaves but they all benefited from that system.

So many astrologers say don't let the stars determine your life but literally turn around and do that. Astrology is a tool at the end of the day. That's it, because if someone doesn't believe in it that doesn't change what happens. Conformation bias would have us believe differently but that's just part of our nature to lean towards that which supports us, not questions us. It's a practice that spans the globe and millennia because we can all look up and see the same stars at night. Maybe not as bright because light pollution, not the same positions because stars go supernova and the solar system moves, but it's still up for everyone on the planet. It's something that regardless of where you go, there's some meaning to it, maybe not always spiritual but a reason nonetheless. And it's never the same, obviously or else this would be a very boring plane of existence, and there's overlap because humans gonna human no matter where we are.

I implore you to think on your upbringing. Think on your ethnic group(s). Think on your current country of residence. Think on what you were taught in school. Think on your family. Because that's what's impacting you. That's what makes you make the decisions you do. Not just Mars moving through your third house (this is just an example, if that's happening for you good for you or I hope it gets better idk) .

Pluto in Aquarius isn't bring change. It's humans and our individual motives that are and always have.

Aquarius is a sign that puts the spot light on things already in motion. It makes you think because if you don't you can't understand. It makes you detached because if you feel it too much you might get hurt. It makes you remember because this isn't the first, nor the last time it will happen. Aquarius is the personal motive made public part of human nature. The selfish desires that push for survival. The seeking of like mindedness. The drive for community, but only if it's the same as you. Aquarius is the when of the story.

#astro tumblr#nymph might piss people off and thats cool#Aquarius#pluto in aquarius#nymph writes astrology#astroblr#pluto is transiting my 1st/12th house. can you tell#astrology

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women’s History Meme || Women from Ancient History (or legends) (3/5) ↬ Septima Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra (c. 240 – c. 274)

Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra, and self-proclaimed Empress, is one of the heroines of the ancient world who has inspired successive generations of scholars, writers, librettists and musicians, playwrights and actors. In the modern western world she is slightly less well known than Cleopatra; in the east she is still supreme, as demonstrated by the massive response throughout the Arab world to the television series called Anarchy (Al-Abadid) broadcast in Syria in 1997. The role of the Empress Zenobia was played by a very famous and beautiful Arab actress, Raghda, and her struggle against the Romans was depicted in twenty-two episodes watched by millions of people. For political reasons, but by controversial calculations, Zenobia claimed descent from Cleopatra, who was neither Arab nor Egyptian, but a Macedonian Greek. The writers of the television series emphasized Zenobia’s iconic Arab origins, but in fact, as a Palmyrene, Zenobia combined elements of Aramaic and Arabic ancestry. The population of Palmyra was descended from an amalgamation of various tribes of different ethnic backgrounds, and their language was a dialect of Aramaic. As the heroic and ultimately tragic Queen of Palmyra, Zenobia ranks with two other heroines of ancient history: the British Queen Boudicca and Cleopatra, who stood firm for their principles and their people, defied their oppressors, and were ultimately defeated. In each case the tragedy is all the more poignant because all three queens were the last of their lines, and after their deaths, each of their kingdoms disappeared, absorbed by Rome. These heroic women passed into legend as a result of their individual struggles and tragic fates, and the simple fact that they were women, who ruled as capably, and fought just as fiercely, as kings. Their enduring fame far outstrips the quantity and quality of the information about them. — Empress Zenobia: Palmyra’s Rebel Queen by Pat Southern

#women's history meme#zenobia of palmyra#syrian history#asian history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was watching the newest season of “When History Meows”, an animated speed-run retelling of ancient chinese history where all the characters are cats. And this season focuses on the rise of the Mongol Empire and the show used the term 一代天骄 “Heaven’s Pride” to describe Genghis Khan. And I realized, in a flash of recognition, that the connotation of this word and the characterization of Genghis Khan of the Mongolian Empire in this retelling is very much in the same spirit of Mary Renault’s characterization of Alexander the Great of the Macedonian Empire in her novel “Fire from Heaven”, which is a retelling of Alexander’s childhood and adolescence. From the way the anime’s story begins with an eagle flying over the vast expanse of Mongolian steppes, the warring grassland tribes being pitted against each other by the powerful Jin empire in the south, the fated 天可汗 Heavenly Khagan who arose from this fractured political landscape and unified the Mongolian people and led them on a conquest to lands beyond the “known world”, terrifying and brilliant, burning across the land like a fire from heaven.

And if anyone in history could give Alexander a run for his money, Genghis Khan is the man.

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! i’m writing an essay on the shift of helios as a sun god to apollo being the main sun god, and wondered whether you had any resources on it, or an opinion of why this happened! the topic is so so interesting to me since there are a lot of different perspectives on it, but it’s difficult to find concrete evidence on exactly when/what period it happened. if not don’t worry, but i’d love to hear your perspective on it.

hope you’re doing well, and thank you :))

Hi! Here are some suggestions for resources that might be useful to what you're looking for:

The Neglected Heavens: Gender and the Cults of Helios, Selene, and Eos in Bronze Age and Historical Greece by Katherine A. Rea: she places the switch in the 5th century BC and only cites Athenian evidence, and makes other interesting points on the topic.

In the common precinct dedicated to Apollo and Helios (Plato, Lg., 945 b-948 b) by Miguel Spinassi (in Spanish): This is mainly a philosophical analysis, but you might be able to find some interesting ideas concerning the syncretism through the philosophical lens.

The cult of Helios in the Seleucid East by Catharine C. Lorber & Panagiotis P. Iossif: this is more indirect and later down the timeline for you, but could give you leads as to the political role of the syncretism in the context of the Seleucid kingdom and why it spread so widely outside of "mainland Greece".

Two works by Tomislav Bilić might also be of indirect interest: this article and his book The Land of the Solstices: myth, geography & astronomy in ancient Greece. Bilić is an ethnoastronomer but he explores how different Greek traditions (Delphian, Athenian, Delian etc.) deal with Apollo and/or Helios through the link between astronomy and cult.

My personal opinion aligns more with what K. Rea brings up. I think that, if the syncretism between Helios and Apollo originates from the Athenian tradition or similar, it would have very easily spread through the centuries, but especially during the "Golden Age" of Athenian colonialism (the famous pentecontaetia). From there, it is easy to imagine how it could have spread to more territories through the Macedonian conquests etc. And then there's the case of Rhodes, which, as far as I know, had a very distinct Helian cult that doesn't seem to have been strongly infiltrated by Apollo. Whether Rhodes is an exception to the rule or evidence that the sync was originally a local tradition that gained popularity until becoming the norm is something I honestly cannot form a convincing opinion on.

This said, I hope the references above help you for your essay, and good luck!

76 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think that Alexander was truly liked by those around him, in a personal level? True friendship. Not really Hephaistion but also like Ptolemy, Seleucus, Roxanne, Arrhidaios, those who grew up with him or were his closest circle. Or was it all cynical politics?

Found it! That was weird. Appearing/disappearing asks?

Did the people around Alexander like him?

Did the people around Alexander like him? Hephaistion did. But the rest?

The asker refers to his personal circle, but I want to address this more broadly. I’ll return to his personal circle at the end.

First, we must beware of that pesky “shading” by later authors as part of their attempts to use Alexander’s career for commentary on their own time. They meant to show how success and power spoilt him and made him into a tyrant. That said, I believe he was well-liked overall. Yet things did change over time.

He began as king of a (relatively) small kingdom in northern Greece where all a Macedonian had to do before addressing him was to take off his hat—didn’t even use the title “King.” By his death, he’d taken over in a tradition that depicted rulers as “King of Kings” and “King of the Four Quarters” [e.g., the Whole World], even a god-king (Egypt). Going from (little) Macedonia to (enormous) Asia naturally cut down on his availability to soldiers and even his own Companions/Hetairoi—which pissed them off. Partly, it was simple logistics. He had too many responsibilities, and too many people wanted a piece of his time. Yet after Darius’s death in 330, he also added layers of court ceremonial to better align with ancient near eastern royal expectations and secure Persian respect.

That alienated his own people (maybe more than he expected). However exaggerated I believe the objections to his adoption of Persian custom, there’s little doubt it wasn’t well-received by traditionalists who preferred their kings approachable. Now, be aware: that approachability was more curated than our sources admit, as these sources inflated shifts to serve their own themes. Macedonian kings had bodyguards for a reason, and certain aspects of divine charisma were associated with their physical person (see below). The average citizen could NOT just wander up to one for a chat. Even so, elaborate Persian ceremonial was quite alien to Macedonia.

Nor was such ceremonial required of Macedonians in 330; our sources note that Alexander was essentially running two parallel courts with differing expectations. Nonetheless, the Macedonians took exception to the changes, offended to see “their” king “succumb” to foreign ways. He was getting uppity. They may also have feared it would trickle down to them eventually, even if it hadn’t yet.

Kleitos the Black’s exact words to Alexander in their infamous, alcohol-fueled spat is 99% invented. (Except maybe the line from Euripides; I’m least suspicious of that.) Some of it involved a play mocking officers who’d died recently at the Marakanda massacre as a means to absolve Alexander, who hadn’t been present, but whose failure to clarify the chain of command got them killed. I suspect that was a lot of it. But as with all “straw that broke the camel’s back” fights, it quickly escalated into a litany of complaints. Some of those were about the changes at the court. And Kleitos didn’t survive the encounter.

Alexander’s remorse appears to have been genuine. And the fact the army was ready to convict Kleitos of treason after-the-fact, said a lot about their empathy for the king. Nonetheless, after that, NOTHING was the same for his inner circle. In the right circumstance, he might kill you. And the army would absolve him of it.

Yet the army didn’t regard every negative act by Alexander as forgivable. They were not willing to overlook the murder of Parmenion. If they could understand/see themselves getting worked up enough to kill even a good friend when drunk, the cold, calculated removal of a potential (not even demonstrated) political threat was something else again. Especially a threat who’d served Alexander (and Philip) with such distinction.

E.g., nuance is required when assessing soldierly opinion.

A couple more things suggest Alexander was—overall—beloved:

1. At the battle of Granikos, he was elected the ancient equivalent of MVP; an award made by soldiers. He accepted, then never allowed his own name to be in the running again. Yet it was an award from the soldiers, and means he was respected not just as a leader, but as a fighter.

2. During both so-called “mutinies,” the soldiers didn’t want to kill him, they only wanted him to change his policies. If there’s some doubt the first actually occurred, the second at Opis certainly did. Yet when he showed the soldiers what it would mean to reject him (he replaced them), they came crying for his forgiveness. They didn’t say, “Good riddance” and head home.

3. On his deathbed, the Macedonian soldiers clamored so to see him that his top officers had to knock down a palace wall in order for them to parade through and say a final goodbye.

Now, that’s soldiers. What about his Companions/Hetairoi? At this high level, liking or disliking also involved personal advancement and family position—as the asker alluded to.

Those willing to “play ball” (so to speak)—go along with Alexander’s changes—had a whole new world opened. This wasn’t just his personal circle but included figures such as Krateros who understood what side his bread was buttered on. I’m not sure how much love was lost between him and Alexander, but they certainly respected each other. There were others who fell into this category, such as Koinos and Kleitos the White. Non-Macedonians/Greeks too, who may have seen him as a road to higher office than they’d held under Darius, or perhaps just to survival. Although I do think Poros and Alexander had a Moment; Poros remained loyal even after it served him to do so, despite his own son’s death at the Battle of Hydaspes. Something actually clicked with those two, I believe.

As for those who grew up with him—Hephaistion, Perdikkas, Leonnatos, Seleukos, Lysimakos … it seems they did like him, even if they didn’t always like each other. Seleukos was responsible for Perdikkas’s murder, in the Successor Wars later. There were others, but those names float to the top again and again. Similarly, although older, Harpalos, Ptolemy, Erigyios, and Laomedon all got themselves exiled for his sake. And Alexander never forgot it. The man who brought news to Alexander of Harpalos’s first flight (due to embezzling) was initially arrested for a false report. Alexander simply didn’t believe his friend had betrayed him.

And it wasn’t just those men. The tale of Alexander drinking a medical potion given him by his doctor Philip—despite a missive from Parmenion warning him about Philip—became famous as a tale of trust. And sure enough, the drought cured the king, so ATG’s trust was well-placed. A later story about Alexander locking up Lysimachos in a cage with a lion in punishment is almost certainly bogus (with overtones of Roman-era stuff). Other evidence suggests great affection for his men. That’s perhaps why Philotas’s failure to inform him about a conspiracy endangering his life came as such a blow.

One may wonder if some of those guys, like the talented—and older—Krateros, didn’t want to replace him as king? Certainly after his death, they did vie to be kings.* Periodically, I run across some misguided person arguing that Philotas and/or Parmenion wanted to take his place, hence the conspiracy. It’s even embedded in our ancient sources, which didn’t understand Macedonian kingship (were thinking on Roman models).

But those men couldn’t be kings. They weren’t Argeads, and it mattered. (Such supposition also assumes they were part of the real conspiracy, rather than Philotas simply being an arrogant dumbfuck who failed to report it.)

The Argeads had Royal Charisma. Charis is a gift from the gods: literally. It can be beauty and grace, sure, but at its base, it simply means “favor.” The difference between a king and a tyrant was that the former had charis by descent. The men who became tyrants (or tried and failed) all believed they had it too, but by their own demonstrated aretē and timē. That’s why they were never just popular Joe Blow off the street. They were Olympic victors, winning generals, etc. All were also aristocrats and fully intended to establish their own royal dynasties…but failed.

Until the Hellenistic Age. The Successors were just tyrants who made it work. Some (like Seleukos) even created mythological origins for themselves. Daniel Ogden has a good book on the creation of this myth: The Legend of Seleucus: Kingship, Narrative and Mythmaking in the Ancient World. If you’re curious about how all those things go into charis, I recommend it.

It’s not enough to be competent. One also needed the gods’ blessing. Charisma. That’s why Alexander’s officers might compete with and snipe at each other…but not with/at him.*

As for figures such as Roxane or Oxyathres (Darius’s brother who joined ATG’s court after Darius’s murder), it’s impossible to know what their opinion of him would have been. We have zero reliable evidence. It would seem Sisygambis (Darius’s mother) genuinely liked him. But again, this may have served later narratives, so I wouldn’t swear to it. She might have just made the best of a bad situation.

So! The final vote is that he seems to have been more popular/well-received than not … for a rather ruthless ancient world conqueror. Ha. I think that’s part of his eternal fascination. He’d be far less interesting if he’d simply been a monster.

Also, I forgot, but I did a separate post a while back on a related topic: Did Alexander's Companions Like Each Other

————————

* It took some years before the Successors started using the title “King” (Basileus). Antigonos Monophthalmos was the first, if I remember right, around the same time Alexander IV was murdered by Kassandros—and he didn’t claim the title himself. It was given him by Athens. Up to that point, they’d all simply called themselves “governors” and/or “regents.” Even if they might have been privately considering how to become kings in their own right, the charisma of Macedonian kingship belonged to the Argeads. Getting rid of Alexander IV (quietly), then Olympias’s murder of Philip III Arrhidaios and Hadea Eurydike left no Argeads. Then Alexander’s empire could become “spear won” territory.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Kleitos the Black#Hephaistion#Harpalos#Krateros#Philotas#Parmenion#Alexander's soldiers#ancient Macedonia#Macedonian politics#the politics of friendship at the Macedonian court#Classics#tagamemnon

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Eurydice, the daughter of Sirras (c. 410–c. 340s BCE), the wife of Amyntas III, king of Macedonia, and the mother of Philip II and grandmother of Alexander the Great, played a notable role in the public life of ancient Macedonia. She is the first royal Macedonian woman known to have done so, although she would hardly be the last. Her career marked a turning point in the role of royal women in Macedonian monarchy, one that coincided with the emergence of Macedonia as a great power in the Hellenic world."

— Elizabeth D. Carney, Eurydice and the Birth of Macedonian Power / Ibid, Women and Monarchy in Macedonia

"Not only did Eurydice intervene in a public and aggressive way on behalf of her sons, playing dynastic politics with some skill, but her dedications around Vergina also speak to a new public role for Argead women. It is also noteworthy that her role and prominence seem to have been greatest not in the reign of her husband but in those of her sons and in their minorities. The remarkably hostile tradition preserved in Justin is testimony to how unusual and threatening her actions were. Nonetheless, Eurydice succeeded in her goals. All the remaining rulers of the Argead dynasty were her descendants."

#eurydike#eurydice#macedonian history#greek history#ancient greece#historicwomendaily#ancient history#my post#women in history

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marriage of Alexander and Roxana by Il Sodoma, 1517 CE

"Roxana (c. 340 – 310 BC, Ancient Greek: Ῥωξάνη; Old Iranian: *Raṷxšnā- "shining, radiant, brilliant, little star"; sometimes Roxanne, Roxanna, Rukhsana, Roxandra and Roxane) was a Sogdian or a Bactrian princess who Alexander the Great married after defeating Darius, ruler of the Achaemenid Empire, and invading Persia. The exact date of her birth is unknown, but she was probably in her early teens at the time of her wedding.

Alexander married Roxana despite opposition from his companions who would have preferred a Macedonian or other Greek to become queen. However, the marriage was also politically advantageous as it made the Sogdian army more loyal towards Alexander and less rebellious after their defeat.

To encourage a better acceptance of his government among the Persians, Alexander also married Stateira II, the daughter of the deposed Persian king Darius III.

After Alexander's sudden death at Babylon in 323 BC, Roxana is believed to have murdered Stateira. According to Plutarch, she also had Stateira's sister, Drypetis, murdered with the consent of Perdiccas.

By 317, Roxana's son, called Alexander IV lost his kingship as a result of intrigues started by Philip Arrhidaeus' wife, Eurydice II. Afterwards, Roxana and the young Alexander were protected by Alexander the Great's mother, Olympias, in Macedonia. Following Olympias' assassination in 316 BC, Cassander imprisoned Roxana and her son in the citadel of Amphipolis. Their detention was condemned by the Macedonian general Antigonus in 315 BC. In 311 BC, a peace treaty between Antigonus and Cassander confirmed the kingship of Alexander IV but also Cassander as his guardian, following which the Macedonians demanded his release. However, Cassander ordered Glaucias of Macedon to kill Alexander and Roxana. It is assumed that they were murdered in spring 310 BC, but their death was concealed until the summer. The two were killed after Heracles, a son of Alexander the Great's mistress Barsine, was murdered, bringing the Argead dynasty to an end."

-taken from Wikipedia

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thessalonike of Macedon

Thessalonike of Macedon (c. 345-295 BCE) was the daughter of Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE) and one of his several consorts, Nikesipolis of Pherae (also spelt Nicesipolis). Born to the Argead family of Macedonian rulers like her half-brother Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE), Thessalonike married Cassander (r. 305-297 BCE), and after his death, she probably acted as regent for their sons.

In contrast with such a high profile, historical details about Thessalonike's life are relatively rare. And yet, her character still casts resounding echoes in both myths and history, in her legendary personification as a mermaid and as the eponym of Greek's second largest, emporium city, Thessaloniki.

Birth & Family

The uncertainties around Thessalonike's historical background start with her date of birth. In the absence of direct hints in ancient writings, scholars have tried to use the meaning of her name as a clue. Stephanus of Byzantium, a 6th-century grammarian, in his geographical encyclopedia, Ethnica, notes that 'Thessalian Victory' was an expression to celebrate Philip II's victory (nike) in Thessaly (Ethnica, v. 'Thessalonike'). Philip’s first grand victory in Thessaly, at the Battle of Crocus Field, effectively awarded the king of Macedon with the life-long archonship of this major Greek city-state right at the south of his kingdom. The title was granted to him by the Thessalians themselves, who had initially called for his help to fend off the Phocians. Philip has been openly applauded by both ancient and modern historians for his numerous political and military achievements in Greece. And yet, this enormous boost of his power as the ruler of Thessaly – and, in effect, of all city-state members of the Amphictyonic League – was nothing less than the dawn of Macedonian glory in the Hellenic world, where the Macedonians were always regarded with contempt.

Philip's victory over the Phocians and their allies, a formidable and ferocious force fighting against the Amphictyonic League in the Third Sacred War (354-346 BCE), scored the first auspicious, game-changing point for the League after a series of inconclusive battles. Philip could also reduce the Phocians' capability by securing an alliance with their main supporter in Thessaly, the city of Pherae, by taking Nikesipolis, a young lady from the family of Jason of Pherae – an ex-ruler of Thessaly – most likely as his second wife (marriage is not verbally mentioned to have taken place, although it is hardly doubtful given the context and later events). Therefore, many scholars connect the birth of Philip's new princess - purportedly an immediate outcome of her mother’s union with him - with the Battle of Crocus Field in 353/2 BCE.

This dating, however, may not match comfortably with the other turning points of Thessalonike's life. Philip II was assassinated in 336 BCE at the wedding of his elder daughter, Cleopatra, with her maternal uncle, Alexander I of Epirus (r. 343/2-331 BCE). The marriage was arranged by Philip himself – a common practice in the ancient Greek world, and many other nations' upper classes throughout history, to secure treaties, mitigate hostilities, pay tributes, or forge alliances. However, by the time of his death, Philip had not revealed any plans for Thessalonike's marital future, presumably because she was still very young. She was believed to be only a child when his half-brother, Alexander the Great, succeeded their father and took the lead in Philip's intended crushing campaign against the Persian Empire. Historians have established that royal women of the Argead court became marriageable in their mid-teens. Thessalonike's half-sisters, Cynane and Cleopatra, were given to the men chosen by their father in their late teens. Therefore, it is unlikely that Philip II in 336 BCE had not already introduced a potential son-in-law for a 17-year-old daughter.

A second date that may question 353/2 BCE for Thessalonike's birth is her marriage in 317 BCE or shortly after to Cassander (Kassandros, c. 355-297 BCE), a commander of Alexander the Great and one of the ferocious belligerents in the Wars of the Diadochi, the succession struggle after the death of Alexander the Great. Cassander secured his claim on the Macedonian throne by turning out to be the ultimate winner of the Second War of the Diadochi when he took the strategically important harbour city of Pydna and put the chief claimants of Alexander's crown, his mother Olympias, his Persian wife Roxana (Roxanne) and their son Alexander IV, to death. Still, like the other Diadochi, Cassander also wished for a familial link with the Argeads to justify his succession of Alexander. And Thessalonike, one of the two surviving daughters of Philip II, was ideally close at hand. She was in Pydna with Olympias, who had raised her ever since Nikesipolis' death only 20 days after childbirth.

Cassander

The Trustees of the British Museum (Copyright)

Apart from obtaining justification, scholars believe that Cassander must have hoped to father a new branch of the Argead dynasty with Thessalonike. This could raise at least a few comments from ancient writers had he been marrying a 36-year-old woman. Moreover, in the heat of the Diadochi wars, it would have been even less likely for Olympias to leave her stepdaughter unmarried for such a long time without trying to use her in the fabrication of an empowering alliance with a king and/or commander. Again, relying on her name to figure out a terminus post quem, a date after which she must have been born, scholars now generally agree that Thessalonike was most likely born around 346/5 BCE, after her father's decisive victory that uprooted the Phocian power once and for all and thus terminated the Third Sacred War. Based on this date, she would be around 9 years old on Philip's assassination and in her late twenties at the time of her marriage to Cassander.

Continue reading...

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

Because unfortunately the internet doesn't have any lists of famous couples in Greek history aside of course... Greek mythology.. i know of Pericles- Aspasia/ Theodora- Justinian but i am very sure there are many more.

Can you make a list of famous couples in Greek history starting from ancient times until 20th century?

I am not perfectly sure how to approach this though. Are we talking about couples both members of which contributed to history? Or just a famous couple we know existed? Also, is this only about history or does it include famous couples culture-wise? Do they both have to necessarily be Greeks by descent? There are many questions I have but I will give it a try.

Periclés & Aspasia (5th century BC)

Aspasia was the sister-in-law of Alcibiades who brought her too with him in Athens from her hometown Miletus in Asia Minor. Aspasia worked as a high-class courtesan, a hetaera. She is perceived in two different ways by Ancient Greeks: either as a vulgar promiscuous woman or as a philosopher and an intellectual. Maybe the truth was somewhere in between. She had a son with Pericles, the most prominent politician of Classical Athens. It is suggested that Perciles heard her council and took her opinions regarding politics into account.

Socrátes & Xanthippe (5th-4th century BC)

Not exactly a role model of a pairing but a famous one nonetheless. For one, the most famous Greek philosopher, Socrates, must have been a LOT older and his marriage to Xanthippe might have not even be his only one. On the other hand, many sources seem to agree that Xanthippe was a notoriously temperamental person and she would mistreat Socrates, who viewed this as an opportunity to practice the values of patience and forbearance.

Crates & Hipparcheía (4th century BC)

Crates of Thebes was a cynical philosopher, whom Hipparcheia of Maroneia met and fell madly in love with. She insisted that (the unattractive) Crates would be the only one she would be having, leading her wealthy parents to despair. The parents asked Crates to talk her out of it himself and Crates complied! He removed his clothes and showed himself to Hipparcheia, telling her: "That's all you'll be getting in a life with me". He did not phase Hipparcheia one bit and eventually the parents ceded and allowed Crates to marry her. They are notorious for a little too much PDA (they were having sex publicly) which scandalised Ancient Greeks a great deal. Their relationship was one of mutual love and respect and living on equal terms together. Hipparcheia not only embraced but started practicing philosophy and totally immersed herself in the respective lifestyle of cynicism as well.

[???] Cleopatra & Antonius (1st century BC)

I don't know if they count since Antonius AKA Mark Antony was not Greek, however Cleopatra was a member of the Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt and their story essentially sealed the Greek future. Mark Antony was a Roman general who opposed to Julius Caesar´s assassins and allied with the latter´s relative Octavian. Later, however, their relationship was strained leading to a form of civil war in the Roman Empire. The reason was that Mark Antony had a long affair with the Queen of Egypt Cleopatra, even had three kids with her, and now favoured promoting Caesarion (Cleopatra´s son from her past affair with Caesar) to the Roman throne instead of Octavian. Mark Antony was defeated by Octavian in the Battle of Actium in Greek territory and then again in the Battle of Alexandria. Knowing there was no hope for them at this point, Cleopatra and Antonius committed suicide together and this generally is viewed as the "official" end of any form of Hellenistic hegemony in the now completely Roman empire.

[???] Justinian & Theodora (5th - 6th century AD)

The question marks are because Theodora was of Greek descent but Justinian was not. Justinian was one of the most successful emperors of the East Roman / Byzantine Empire, making it reach its widest borders, including "reconquests" of the fast dissolving Western Roman Empire. He also achieved or rather imposed the peace in the internal affairs of the empire, sometimes with the use of a lot of violence. It is believed that he was very influenced by his wife Empress Theodora, who was hardened by her very humble origins (she was likely a prostitute). Theodora was extremely strong-minded and contributed a lot to the strong image built around her husband. Furthermore, she contributed to the making of laws for the improvement of the position of women in the society. Most sources agree Justinian was crazy for her, while it is uncertain whether Theodora was loyal to him.

Surviving mosaics of Justinian and Theodora in a Byzantine Church in Italy.

Kassianí and Theóphilos (9th century AD)

These two have become a romance in legends more than they might have actually been in their real life. Still, their affair or lack thereof, technically, has a significant enough impact on Greek and Greek Orthodox culture so they should be mentioned. The Byzantine Emperor Theophilos invited all the prettiest maidens of the empire to his court in order to pick a wife. Amongst them, Kassiani was the one who stood out both in looks and intellect. The emperor stood before her and offered her a golden apple, token of his affection and proposal. It is totally unclear what was happening in Theophilos' brain at the moment but of all things he could say to impress her, he chose to tell her something very sexist. Kassiani ended him on the spot with her response and did not take the apple. The emperor, humiliated in front of all his court, gave the apple to Theodora (another one!), another fine lady standing next to Kassiani. For all we know, this could be the end of it. But Kassiani's choice to never marry and isolate herself in a monastery instead has created legends and speculations that it was due to her heartbreak. In any case, Kassiani proceeded to become the most (or only) significant female psalm composer and poetess in the history of the empire and her psalms and hymns are used in the Service of the Orthodox Church during the Holy Week of Easter. Meanwhile, Theophilos fell ill early in his life and died young. It is said / speculated that when he felt death was near, Theophilos visited Kassiani in her monastery to see her one last time. Kassiani saw his carriage approach and hid herself in a closet to avoid the temptation. Theophilos entered her cell and saw nothing but the psalm she was composing at the time on a table. He read it and added the last line himself. He understood she was hiding from him, respected this and left. Kassiani got out, read the hymn and kept Theophilos' addition. Since then, the last verse of this hymn is attributed to Theophilos. For more about Kassiani and what exactly were the notorious exchanges they had that separated them as well as how the content of this hymn is essentially what led to these speculations, read this older post I had made.

Mantó Mavroyénus & Demétrios Ypsilantis (19th century)

A romance that flourished amidst the years of the Greek Independence War. Demetrios led many of the battles against the Ottoman army, however he is a little overshadowed by the more tragic story of his brother, Alexander Ypsilantis, who was the overall leader of the Friendly Society (the secret organisation which plotted and spread the fervor for the Greek Revolution). Meanwhile, Manto was the daughter of a wealthy aristocratic Greek expat in Italy, who was also a member of the Friendly Society. When the war broke out, Manto first tried to raise awareness about the Greek cause in France. Soon, she departed for Mykonos island, the place of her descent, with a large part of her fortune. She bought ships and created her own fleet, sending them and her men to many battles in the islands. She later participated in several battles in mainland Greece as well. There she met Demetrios and they got engaged. She became renowned in all of Europe at the time for her beauty and activity. The couple was in love and they were adored by the Greeks, who really liked that union of brave noble Greek role models. A prominent and very corrupted politician, Ioannis Koletis, did not share the sentiment. Fearing that the couple was gaining too much power and influence over the public, that could eventually turn political, he started a relentless defamation of Manto to her fiancé. He spread his lies so that Manto's reputation was ruined. Ashamed, Demetrios broke up with her. Manto returned to her home island heartbroken and penniless as she had given all her fortune for causes of the war. After the official indepedence of the Greek state, the enlightened governor Ioannis Kapodistrias restored her reputation and gave her the honorary title of Lieutenant general. Around the same time, Demetrios passed away young as he had always frail health.

Penelópe Delta & Ion Dragumis (19th - 20th century)

A famous love story rather than a couple. Ion Dragumis was a prominent young politician and the biggest adversary of the famous Greek politician Eleftherios Venizelos. He was very sophisticated, seductive and a smooth womanizer. He drew the attention of the slightly older author Penelope Delta, who at the time was already a mother of three. Delta fell so madly in love that she had the guts to reveal the truth to her husband and ask for a divorce. Her husband refused, trying to protect both his and her reputation. However, Delta's passion for Dragumis was so fierce that neither the husband nor her father could fight it. They eventually gave her an ultimatum that she had to choose either her children or leave the children to the father and go away with Dragumis. Delta chose to stay with her children but her desire was such that she attempted suicide multiple times. Meanwhile, Dragumis went on with his life and started an open affair with the famous actress Marika Kotopuli, without any intent to marry, which was very scandalous for the time. When Delta heard of this affair she started dressing in black, as if in grief, and kept doing it until the end of her days. At some point, there was an attempt at an assasination of Venizelos in Paris. Fanatic supporters of his in Athens, believing mistakenly that his big adversary Dragumis was behind it, trapped him and shot him in the middle of a street. Delta dedicated some of her later activity to sort out and copy a lot of Dragumis' drafts full of thoughts and ideas, that his brother had entrusted with her. Apart from this, Delta kept writing novels that made her the most prominent female writer of her time in Greece. She had reached her sixties when, in 1941, the Nazi Germans invaded Athens. On that day, she finally committed suicide by drinking poison. For more details, read this older post about Ion Dragumis' love life.

Kostas Karyotakis & Maria Polyduri (20th century)

Two young people, brought apart by their very different personalities and brought together by the fact that they both happened to be poets. The young couple fell madly in love. Karyotakis was a very timid and bashful man, full of insecurities and suicidal thoughts. On the other hand, Polyduri was a raging emancipated extrovert, which caused judgement at the time. Although they were very much in love and dreamed to elope together, Karyotakis was afraid of the bold lifestyle of Polyduri and the judgement it caused. When the girl even took the initiative to propose to him, the young man was so taken aback and panicked that he lied to her that it was no use, because he suffered from syphilis and therefore they should not consumate the marriage. Polyduri did not believe him but she was very heartbroken by his rejection. She departed for Paris where she continued her bohemian lifestyle, maybe taking it too far, until they found her unconscious in a narrow alley. She was diagnosed with tuberculosis and was taken to the sanatorium in Athens. As she was fighting for her life, she learnt that in her absence her past lover had finally committed suicide. His suicide note is very famous, as he describes how he initially tried to kill himself by drowning in the sea but failed because he was a skilled swimmer. He resorted to a pistol. The tragic news had very adverse effects on Polyduri's fragile health. A friend of hers, maybe taking pity on her, handed her injections of morphine, with which she ended her life as well. She has left a suicidal poem, which confirms that grief was the reason she took her life.

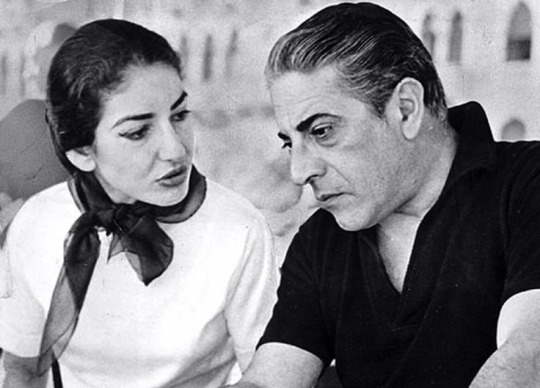

Maria Callas & Aristotle Onassis (20th century)