#ancient Macedon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

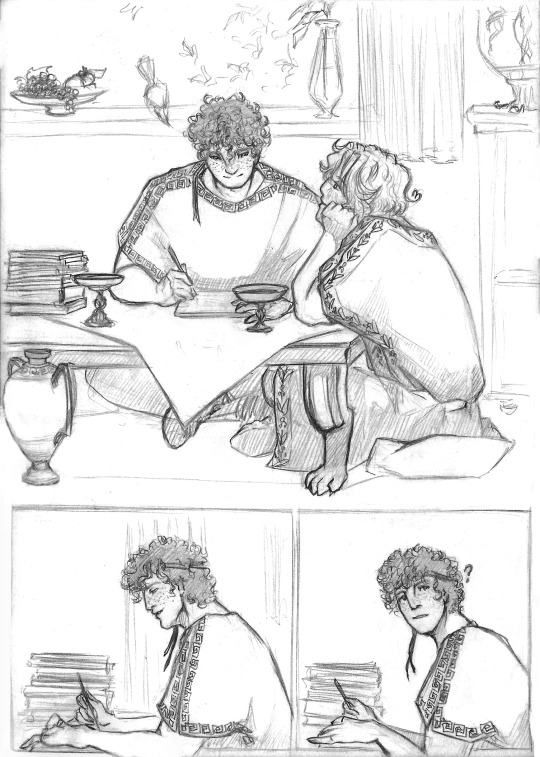

short little comic I drew in lectures

given Alexander's tendency to work a lot and sleep very little, especially earlier in his life, he likely had a tendency to doze every free moment he got (based off my own habit of falling asleep at my work table all the time) - and I wanted to draw something with it

#ert#comic#atg#alexander the great#alexander of macedon#hephaestion#hephaistion#alexander x hephaestion#alexander/hephaistion#I will draw them until we all agree on a shipname or I will die trying#ancient greece#ancient macedon#for anyone interested: I imagine this taking place sometime after Tyre. before the conquest of Egypt#this is very soft very shoujo manga-esque and that was Intentional#I also kinda went into it no thoughts head empty#so there was no thumbnailing or figuring out the layout or anything just rawdogging this whole damn thing#i intended to just scan it and drop it unceremonously#anyways I spent like 40 minutes trying to at least Slightly edit it#its been so long since i posted a comic (even longer since I posted an unedited comic)#so. yknow. enjoy#and talk to me about these two?? I guess???#dedicated to all 2 people who follow me because I post about them and the 3 people who now always think of me when they hear his name#youre welcome for that btw

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cleopatra Eurydice

#studyblr#notes#history#historyblr#history notes#world history#world history notes#western civ#western civilization#philip II#cleopatra eurydice#macedonia#greece#ancient greece#olympias#europa#alexander the great#greek history#caranus#alexander of macedon#macedon#ancient macedon#cleopatra

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

Whenever we think of royal families our minds tend to go to the concept of the European noble House. The House of Habsburg, the House of Windsor, the House of Stuart etc. I understand that we should look at the Ancient Greek, Macedonian & Hellenistic royal families in a different way becuase of the different family & power dynamics - could you please help us understand the difference?

Ancient Court Societies vs. Modern

Probably the biggest difference is greater organization of hierarchy. Modern royal houses have had a lot of time to evolve.

Norbert Elias’s The Court Society has become the foundational study on court systems, although it’s western-focused by intent. Nonetheless, it’s a useful introduction to how courts function with inner courts, outer courts, etc.

The biggest things to keep in mind are:

The degree of formality between court members. How “deep” and structured is the hierarchy? (Smaller courts typically have far less formality than larger ones.)

How formalized are matters of succession and marriage ties? Particularly the presence (or absence) of royal polygamy can affect that.

Court societies inevitably progress from less formal and hierarchical to more of both. We can sometimes talk about earlier court societies as chieftain-level societies versus more organized royal, or even imperial societies.

Part of the struggle first Philip, then Alexander faced was transforming a chieftain-level court system into something that would work on a (much, for Alexander) larger scale. Unsurprisingly, there was push-back against, essentially, “bureaucracy.” Nobody likes it, but the larger an area controlled, the more necessary it becomes.

Traditional Macedonian courts were fairly informal, the king being primo inter pares (first among equals). No titles were used when addressing him—he was called by his name—and the only thing expected of the speaker was to take off his hat. “King” (basileus) was used when speaking OF him. We don’t see “King ___” employed in Macedonia (at least in inscriptions) until Kassandros, who needed it to buck up his claim.

None of that means the average person could wander into the palace and start chatting up the king. He was protected by his Bodyguards (Somatophylakes), who also apparently managed access to him. Yet he was expected to sit in judgement as an appellate court, where anybody could appeal a case before him. How often this occurred no doubt depended. Philip was gone a lot, and Alexander was permanently out of Macedonia two years into his reign. Presumably his regent fulfilled the role in his absence. (As I depicted near the beginning of book 2, Rise, when Alexandros is hearing cases.) Anyway, that’s one place the “average person” could get the ear of the king. Also, it seems that he was more approachable by soldiers in battle circumstances. We’re told Alexander got right in with his men to do work during sieges. It was to encourage them, but he was standing next to them so they could see and talk to him, if they wanted to. He seems to have known many of his veterans by name.

Another factor in Macedonia was lack of formal hierarchy among nobility. They had a nobility—the Hetairoi (King’s Companions)—but theoretically all Hetairoi were equal in status. In practice, they absolutely weren’t. The king also had an inner circle referred to as “Friends” (Philoi), who acted as chief advisors. The problem with both terms is their use as common nouns as well as special titles. When is a friend a Friend?

Also, at least some of this was hereditary. Yes, making (or removing) Hetairoi was in the power of the king. But it was much easier to do the former than the latter, and even strong kings didn’t do the former early in their careers, never mind the latter. For many, becoming Hetairos was a rubber-stamp. They were Hetairoi because their fathers had been. We’re also not sure if the title was extended only to the eldest male in a household, or more than one could hold it at once, but for most, it was a birthright.

So, when Alexander took the throne, he was stuck with his father’s Somatophylakes (Bodyguard) and inner circle of advisors. He absolutely could not toss them out on their ear to install his own men. He had to proceed sloooowly. Which is why we don’t see Hephaistion as a Somatophylax even by the Philotas Affair, five years into ATG’s reign. He was clearly an advisor (Philos), but didn’t become Bodyguard until sometime later. Same thing with Ptolemy, who apparently got Demetrios’s slot—the Bodyguard (almost surely one of Philip’s) behind the actual conspiracy of Dimnos, not the made up one of Philotas. When he was executed, Alexander promoted Ptolemy to his slot. Note that Ptolemy was made Somatophylax before Hephaistion. Politics, family status, and probably age trumped personal affection.

If Hetairoi couldn’t be kings themselves (unless they were also Argeads), they were king makers, and kings had to take their influence into account. Especially new kings.

As a chieftain level society, Macedonia operated on “rule by clan” with the king being the senior male Argead. His brothers, sons, nephews, and male cousins might all have important roles, as did the women, although theirs were primarily religious and the running of the royal household. Yet royal women could do limited politicking in the way of donations (eurgetisms) to create goodwill, promote the family, or make alliances—as well as (of course) the alliance created by their marriage itself. Most of these roles were informal and ad hoc, rather than titular, if also expected of them. For instance, the king’s wives were just that: king’s wives. The title queen (basileia) wasn’t used until the Hellenistic courts of the Diadochi.

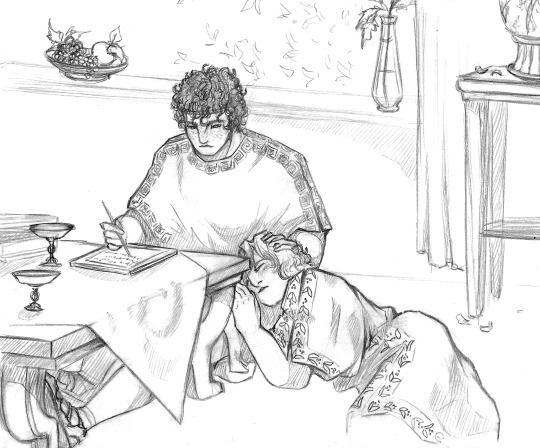

Ancient near eastern courts were more stratified, with more distinct roles. In fact, it seems that Macedon, from Alexander I onward, borrowed offices from the Achaemenid Persian court, including the Bodyguard and the Royal Pages (King’s Boys). So as early as the late Archaic Age, Macedonia looked east for how to formalize a court. Certainly Philip did it well before Alexander. The notion that Alexander’s Persianizing was somehow new is bull malarky.

Anyway, in the ANE, kings tended to fit one of two traditions: shepherd king or heroic king. The Sumerian kings and Hammurabi (Old Babylon) were both examples of the shepherd-king model. Heroic kings began with the Akkadian, Sargon the Great, then the neo-Assyrian kings, especially the Sargonids. Cyrus cast himself as a heroic king, but we see a shift back to shepherd kings with Darius the Great. Another aspect of ANE kingship were three chief expectations: win wars, build big shit, and administer justice.

Due to a much longer tradition of kingship extending from the Early Bronze Age, as you may imagine, these court systems developed much more in the way of formalized structures and offices. If these changed from king to king, at least by Bronze-Age Babylon (Hammurabi), then Neo-Assyria, access to the king was severely curtailed. At least the Persian kings got out and moved around on a sort of “King’s Progress,” but that was to check up on satraps. The average citizen saw them only at a distance. In contrast the Sargonids of neo-Assyria emerged from their palace complexes almost exclusively when going to war.

The Medes and Persians, like the Hittites before them, fit themselves into ANE traditions after they arrived in the area. Less is known about pre-ANE Hittites, but if they kept some unique religious traditions, when it came to How to Run an Empire, they used Akkadian and Egyptian precursors. Similarly, the Medes and Persians who came from the steppes, also adopted ANE patterns while retaining some traditions—again particularly religious (Zoroastrianism). We know a wee bit more about them prior; they (like Macedon) seem to have had chieftain-level monarchy with rule by clan, plus tribal princes, before conquering the whole area.

I hope that helps in understanding ancient eastern Mediterranean and near eastern notions of a court. We know less about the Odrysian Thracian and Illyrian kings to Macedonia’s north, but I suspect they were similar to early Macedon. Just tooling around Thrace, it was very clear to me that we’re looking at a shared regional culture between that area and Macedonia. Similar vibes attended my visit to Aiani (ancient Elimeia) and Dodonna (Epiros). I didn’t get up into Illyria, but what I do know of the archaeology suggests the same. ALL these cultures, despite the ethnic and linguistic differences, influenced each other. Yes, ancient Macedonia was at least “Greek-ish,” but we can’t and shouldn’t dismiss the impact on them from their northern neighbors.

Last, let’s consider the role of royal polygamy. Well back into the Bronze Age, ANE kings might marry several wives and also kept concubines for political purposes. That’s why we call it royal polygamy, not just polygamy. Royal polygamy might exist in a society that otherwise limits the number of wives anyone not the king can have.

Macedonian kings also practiced it, and Thracian and Illyrian, but on a more limited scale. Greeks and Romans, then Christians, depicted any polygamy as a “barbaric Oriental” (= morally corrupt) practice that supported their general view of Asia as soft and indulgent. (Sex itself wasn’t a vice, but too much sex was: uncontrolled desire.)

In later Europe, kings might have mistresses, but it wasn’t “official,” and they certainly didn’t have multiple wives. Christianity frowned on that. Even before, Roman emperors didn’t employ royal polygamy, although they did use serial monogamy—a long-standing practice back into the Roman Republic. Yet that required divorce. When the Christian church made marriage both a sacrament and a vow (not a contract, as it had been pretty much everywhere else), they made divorce impossible without either a wife’s death or religious shell games like annulment. Until Henry VIII, European kings were largely stuck with just one marriage.

Ancient courts didn’t have that problem. And from a political point of view, monogamy is a problem. It reduces the number of political ties available. Having royal polygamy offers more fluidity in possible heirs, and increases, sometimes exponentially, avenues for political alliance.

That said, the downside can be messy inheritance. Two of the more infamous inheritance disputes (other than Alexander’s) involved Esarhaddon, youngest son of Sennacherib, and Cyrus the Younger vs. Artaxerxes II. The latter dispute resulted in civil war (thank you, Xenophon, for telling us about it). As for Esarhaddon, he was so in danger from his older brothers, his mother kept him out of the capital until claimants were dead. There are others, but these two leapt to mind. There are also Egyptian examples, but I’m far less knowledgeable about those dynasties. And, as we see later in Europe, disputed successions can occur without polygamy!

Anyway, when it comes to selection of the heir, two things that matter in polygamous courts: status of the mother, and (for the ANE) whether she was queen. Not all wives were also queens. In the case of Esarhaddon, his mother Naqiʾa was of lower status and not a queen, so when his father named him heir, his older brothers (and their court allies) blew a gasket. Both Assyrians and later Achaemenid Persian kings could marry as many women as they wanted, plus take concubines…but the heir was expected to be from his Chief Wife, or Queen. Of “pure” blood. Cyrus the Younger’s argument against his older brother rested on a similar status technicality: he’d been born after his father became king, while Artaxerxes II was born before. We’d say Cyrus was “born to the purple.” But it was just an excuse; he was the ambitious one, and their mother favored him. If Macedonia didn’t have queens, the status of the mother mattered to being selected as heir there as well.

So these are some of the chief differences between ancient Mediterranean and near eastern courts, compared to later European.

#asks#Alexander the Great#ancient Macedonia#ancient Macedon#ancient Persia#ancient Assyria#ancient Babylon#court societies#ancient court societies#Macedonian court#Philip II#kingship in the ancient near east#kingship in Macedon#Classics#tagamemnon

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve never watched a video from this Monsieur Z fellow, but the title of his last one is... Certainly a banger. “What if Sparta Conquered Greece?”

Yeah, dude, what if Sparta had an expansive rather than isolationist state ideology, a fucking clue about logistics, and army that wasn’t just the glorified version of the same old hoplite system everyone used and based off of their increasingly small and more exclusive ruling class? Wonder what that would be like, if Sparta wasn’t fucking Sparta, but displaced Macedon???

#ancient greece#achaemenid empire#sparta#ancient sparta#ancient macedon#alexander the great#random history#fuck#let's add#300 the movie#because c'mon#i haven't even seen the video#and i can already tell#that it goes full on spartan mirage

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Citadel of Herat (Pashto: سکندرۍ کلا ; Dari: ارگ هرات), also known as the Citadel of Alexander, and locally known as Qala Iktyaruddin (Pashto ; Dari: قلعه اختیارالدین), is located in the center of Herat in Afghanistan. It dates back to 330 BC, when Alexander the Great and his army arrived to what is now Afghanistan after the Battle of Gaugamela. Many empires have used it as a headquarters in the last 2,000 years, and was destroyed and rebuilt many times over the centuries.

From decades of wars and neglect, the citadel began to crumble but in recent years several international organizations decided to completely rebuild it. The National Museum of Herat is also housed inside the citadel, while the Afghan Ministry of Information and Culture is the caretaker of the whole premises.[1][2]

Herat, Afghanistan

©️ Steve McCurry

#history#classics#military history#architecture#urban#battle of gaugamela#achaemenid empire#ancient macedon#afghanistan#herat province#herat#herat citadeal#steve mccurry

405 notes

·

View notes

Text

another comission for @charlenefrl!! Philippos of Makedonia from their novels! Go check their writing! https://archiveofourown.org/users/CharleneF

#my art#Philip II of Macedon#Philippos of Makedonia#antiquity#ancient history#art commisions#tagamemnon#macedonia#dionysus

475 notes

·

View notes

Text

Demetrius I Poliorcetes

#demetrius i poliorcetes#demetrius poliorcetes#art#macedonian#nobleman#king#bronze#bust#head#demetrios poliorketes#ancient greek#ancient greece#classical antiquity#europe#european#history#macedon#macedonia#antigonid dynasty

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

alexander and phai 🎀✨️

#ancient greece#alexander the great#alexander of macedon#hephaestion#alexander x hephaestion#alexander and hephaestion#fanart#artist on tumblr#tagamemnon#my art

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silver tetrobol (diameter=15 mm; weight=2.45 g) minted in the Kingdom of Macedon during the reign of Perdiccas II (r. 454-413 BCE). The obverse features a horseman who wears a petasos (the broad, flat hat characteristic of Macedon) and carries hunting spears; he is accompanied by a dog. This image reflects the keen interest in hunting among the Macedonian aristocracy. The reverse features the Nemean Lion, whom Heracles slew as the first of his Twelve Labors. The Argead dynasty of Macedonian kings, to which Perdiccas belonged, claimed descent from Heracles; when Alexander I, the father of Perdiccas, sought to compete in the Olympic Games, he used this purported descent to prove his "Greekness". Above the lion is a kerykeion, the staff borne by heralds (and by Hermes, patron deity of heralds); those holding the kerykeion were sacrosanct and could not be harmed without incurring the wrath of the gods.

Photo credit: Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com

#classics#tagamemnon#history#ancient history#Ancient Greece#Macedon#Classical Greece#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Macedonian art#coins#ancient coins#numismatics#ancient numismatics

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

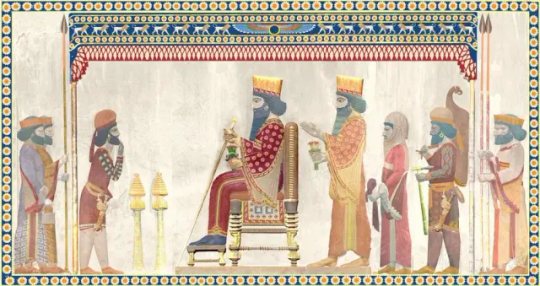

Spirits of ancient battles. Memories of Alexander the Great (2023/2024)

Gouache version of the work from 2017: https://www.tumblr.com/marysmirages/686070565494259712/spirits-of-ancient-battles-memories-of-alexander?source=share

#alexanderthegreat#hephaestion#hephaistion#alexander of macedon#marysmirages#asia#ancient greek mythology#painting#art#horse#rider#mirage#oasis#persia

501 notes

·

View notes

Text

decided to post a semi-finished panel from a short comic I've been drawing slowly over the weeks, as a valentine's day treat

alexander and hephaistion enjoying some alone time with paperwork and wine

#ert#sketchbook#alexander the great#hephaistion#alexander x hephaestion#once more I am begging the ancient macedon fans to come up with a shipname#ancient greece#ancient history#ancient macedonia#Im thinking of this being like.... memphis or earlier. maybe after tyre even#i have yet to add a background to this but Ill have to do some research into what that might be and honestly I dread it a little bit#there's one more page and some details to do so I hope to have the comic out sometime next week?#its very unpolished in its storytelling I just wanted to try and see what might come out when I do unscripted stuff after so long

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ο δὲ Ἀλέξανδρος, ἐλθὼν εἰς τὸ ἱερὸν τοῦ Ἄμμωνος, ἐπηρώτα τὸν θεὸν εἰ πάντων τῶν ἀνθρώπων βασιλεὺς ἐστί. ὁ δὲ ἀνὴρ ὁ χρησμῳδός, ἀτενίσας, ἀπεκρίνατο· "οὐ μόνον τῶν ἀνθρώπων, ὦ παῖ Διός, ἀλλὰ καὶ τῶν θεῶν

But Alexander, having come to the temple of Ammon, asked the god whether he was the ruler of all men. And the priest, gazing at him, replied: 'Not only of men, O son of Zeus, but of the gods as well.'

#greek posts#greek quotes#greece#greek#black and white#alexander of macedon#alexander the great#hellenism#hellenistic#hellenistic art#philosopher#philosophy#greek art#ancient#ancient greek#ancient greece#history#historical#alexander and hephaestion#artwork#art#greek pantheon#hellenic worship#hellenic community#macedonia#philip ii of macedon#macedonian#quotes#literature#zeus

64 notes

·

View notes

Note

What should we make of Alexander I and Perdiccas II both having long 40+ years long reigns, only for all of their successors having substantially shorter ones? And, if you are in the mood, who do you think was the better ruler between the two?

Alexander I and Perdikkas II

First, I thought I’d mention one of the cool things to come out of the recent ATG conference is a plan to produce an edited collection: Alexander I and the Making of Macedon. It’ll be a while, but if I can get us a publisher, I’ve got the contributors.

Also of note, Sabine Müller and Johannes Heinrichs are producing a monograph on Alexander I in English. She has a great one on Perdikkas but it’s in German, so I was very happy to hear this.

Finally, I've got a number of racked-up Asks. This answer will answer about three of them. I'll link it to the other questions. :-)

To the questions: it’s really hard to compare Alexander I and Perdikkas II simply because they were dealing with very different circumstances. Alexander I had Persian assistance holding the throne, while Perdikkas was tossed off his throne at least once.

The biggest difficulty is a source problem. ALL our info about these guys (outside archaeology) comes from Greeks, who were chiefly interested in them only when they intersected with the southern Greek world. There’s a fair bit about Alex I’s internal politicking that we just don’t know. What we call “Lower Macedon” probably only goes back a couple generations, despite the mythical king list. We find a MARKED change in burial practices c. 570 BCE, which is before Persians were mucking around up there. This suggests a change—or more likely consolidation—in the lowland Macedonian ruling elite, both west and a bit east of the Axios River.

If Alexander I took over c. 500-495 (coin above), and his father Amyntas (about whom we know nothing but a name) ruled for 20/30-ish years before, then Alexander’ grandfather (Alketas) or great-grandfather (Airopos) would have consolidated the area around Aigai. Yet ALL names before Amyntas I are essentially fictional. Certainly the “founder’s” name changed across time. It’s Perdikkas when we first hear of it in Herodotos, but may have shifted to Archelaos later (see Euripides’s play of that name). Later yet (under Philip), it seems to have become Karanos. If Bill Greenwalt’s theories are right. This is not a real person in any historical sense.

The problem with dating Alexander I is that we neither know for sure when he took the throne nor when he died. It was convenient for Alexander to blame his father for any concessions to the Persians, but he—not Amyntas—married his sister Gygaia to a Persian (Bubares, son of Magabazus and distantly royal).* More likely he was already on the throne in the 490s but may have been quite young. He seems to have used the Persian presence to further consolidate the (new) Macedonian kingdom—against Paionians and others—adding territory as far away as Amphipolis, at least temporarily, and thus, getting hold of both silver and gold mines to mint coins. The Echedoros River also held gold. All the gold in pre-Alexander Macedonia was pacer mining (panning), not from the gold mines of Mt. Pangaion. Yet gold, while present in the rivers, only became important in graves in Macedonia c. 570…it’s part of that startling shift in burials that we see.

We also don’t know exactly when Alexander I died and Perdikkas took over. He was still king at the end of the Persian Wars in 479/78, but dead by 450. His death may have been closer to 460, or even earlier. So his reign was probably more like 30-35 years. Perdikkas perhaps reigned longest of all—one reason he’s exceptional. I wonder if the Peloponnesian War itself may have contributed to his success: for all he had his challengers, if Macedon wanted to survive as an independent political entity, they needed to rally around him.

Yet he faced his share of opposition from other Argeads as well as the very powerful Upper Macedonian kingdoms of Lynkestis (Lynkis) and Elimeia, not to mention predatory Illyrians. That’s why Perdikkas sought an alliance with Brasidas of Sparta, but apparently couldn’t even control his own troops enough to keep them from deserting when facing Illyrians. That earned Brasidas’s wrath. As a result, Perdikkas (coin below) had to make nice with Athens.

That’s just one example of Perdikkas’s deal-making during the war. He had quite a job of diplomatic shuffling—no doubt learned from Daddy Alexander. Neither had a kingdom anywhere near strong enough to fend off Persia, or Athens and Sparta later. The fact Perdikkas didn’t end up a client king to either Sparta or Athens is a testament to his diplomatic skill.

Perdikkas’s eldest son Archelaos wasn’t the “illegitimate” son of a slave but of a lesser wife, which is why the younger (unnamed) son initially inherited. Archelaos quickly did away with him (plus an uncle and cousin), then proceeded to continue the modernizing work of his father and grandfather. Until he got run through in a hunting “accident.” After that, the kingdom dissolved into a mess.

The problem of a fast turn-over of rule owed to their inheritance system: any Argead had a claim on the throne. Kings also practiced royal polygamy, although two wives (at most three) seems to have been typical until Philip II. In some ways, it worked well, as it produced multiple heirs from which a strong king could emerge (by surviving).

That was also its problem: no clear method of succession, even if the sons of higher-status mothers apparently had a leg-up. Perdikkas himself was not Alexander’s eldest son. He had two older brothers and two younger ones. Yet either his mother was the most prominent or he showed the most promise (or both). Despite Archelaos’s age and apparent ability, he was initially passed over, although Plato (who tells the story) means to paint Archelaos poorly. That doesn’t mean he didn’t kill competing Argeads to take the throne. So had his father, and probably grandfather too (we just don’t hear about it).

Yet Archelaos’s unexpected death led to a continuing crisis until Amyntas III, Phil’s dad, took and kept the throne. He came from a collateral Argead line descended from Alexander I’s youngest son. The other lines killed each other off. For all Amyntas wasn’t a terribly prepossessing king, he managed not to die. But he, too, was run off his throne at least once, maybe twice. When he did die, it was in his bed of old age—not a common thing for Macedonian kings. His reign was the first tolerably long one after Archelaos, over 20 years.

By the time Philip came to the throne, there weren’t many Argeads left thanks to the catch-as-catch-can method of succession: Philip’s two older brothers were dead and all three of his half-brothers. It was down to just him and his brother Perdikkas III’s infant son: Amyntas.

This is the inevitable problem when lacking a clear succession. Yet a clear succession can create its own problems with incompetent heirs, who don’t always recognize they’re incompetent. The free-for-all gave a better shot at a strong king—ostensibly why it developed—but it also meant the kingdom ran out of “spares” after a couple generations. They went from more Argeads than you could shake a stick at following Alexander I’s death, down to just three at Philip’s death, and two at Alexander’s death** in a matter of 5-6 generations. Within those 5-6 generations, 12-14 kings reigned! And we have no idea how many brothers/cousins/uncles Alexander I had, and perhaps killed, before he became king. We hear only about the one sister.

Stability was not a hallmark of the Argead dynasty.

——

* The story of Alexander killing Persian emissaries is much later fictional propaganda. Didn’t happen.

* Alexander’s son Herakles by Barsine might count as a third, but the army doesn’t seem to have considered him viable for whatever reason.

#ancient Macedon#ancient macedonia#Argead Macedonia#Temenids#Argeads#Alexander I of Macedon#Perdikkas II of Macedon#Gygaia#Archelaos of Macedonia#Philip II of Macedonia#Philip of Macedon#Alexander the Great#ancient Greece#Persian Wars#Greco-Persian Wars#Peloponnesian War#Brasidas of Sparta#Classics#tagamemnon#asks#Early Macedonian History

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine this: a young, mighty king has just conquered some faraway regions in the East, so he and his men decide to celebrate one night.

Still a bit tipsy after the celebration, the conqueror goes to attend the dance competition held in his honor: the winner turns out to be a young eunuch of extraordinary beauty, praised generously and crowned by the king himself.

Seeing the two of them so close, the men and all the others start applauding from the stands, and they all start shouting in unison: "Kiss! Kiss! Kiss!"

The king, amused, does not object: he smiles and wraps his arms around the beautiful dancer, whom he kisses gently on the lips among the cheers of his men.

No, I did not just come up with this. It's a small historical anecdote. And the king in question is none other than the GOAT Alexander the Great.

#alexander the great#alexander of macedon#source: Plutarch and others#bagoas#competition#anecdotes#ancient history#the persian boy#it may be just an anecdote but it's so beautiful help

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

A frieze from the royal tomb of King Philip of Macedon ( 382 - 336 BC) was restored with specialised AI tools in the project ReVis, run by the Democritus Physics Research Institute and the Archaeological Department of Imathia.

The restored artwork shed a new, groundbreaking light on Classical Greek art, presenting a much more elaborate profile than initially thought, with the use of way more paint shades than previously believed and the use of different paints for the depiction of depth, shade and texture. It also shows that the four-colour painting Classical Greek art was associated with was not exclusive, but rather a painting style amongst others.

The artwork is a hunting episode from King Philip’s life, joined by his son Alexander the Great. The restored image also exposes a mysterious figure, an unknown crowned young man next to the two famous royals.

(Click and zoom in the picture for better analysis.)

Below is an image from the process of the digital restoration of the artwork with AI tools.

Sources:

Greek reporter

Kathimerini newspaper

#greece#Ancient Greece#art#ancient Greek art#Alexander the great#history#classical art#king Philip of macedon#Greek culture#Imathia#aegae#Vergina#Macedonia#mainland

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

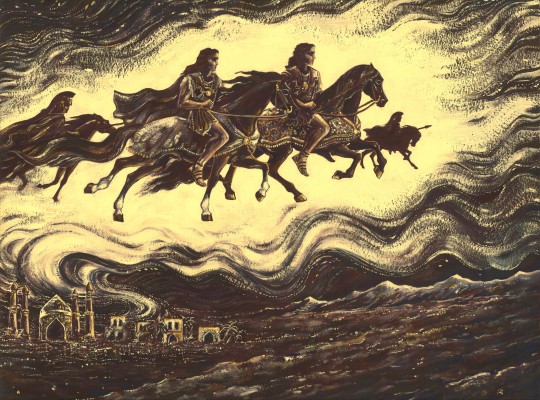

Most men float (by @charlenefrl all go subscribe and read their novels!!!)

For context, the scene takes place in the winter of 340/339 BCE, in Odessos. After he abandoned the sieges of Byzantion and Perinthos, king Philippos of Makedonia (Alexander the Great’s father) decided to march against the Scythian king, Athéas. He was aided by his father-in-law, the Thracian king Kothelas. Once Athéas was defeated, Philippos and Kothelas returned to Odessos, where they celebrated with a great feast.

Afterward, Philippos will march south with his army and his share of the loot, only to be ambushed by the Triballoi in the mountains. But that’s not where we are yet: the celebration is just winding down, everyone has drunk far too much, and someone has decided this is the perfect opportunity…

The magic stuffs in this piece are inspired by the play the Bacchae by Euripides and by a tale of Dionysos changing pirates into dolphins.

The wine was still thick on Eudamos’ tongue. That was one of the reasons why, for the first time since the Persian gold had touched his fingers, his courage did not fail him.

He was a good climber, always had been. As a young pauper in Pella, he had often scaled walls like a spider to get inside opulent houses. It was only when his reputation as a thief caught up with him that he decided it was time to pack up and leave.

That, and the glint of the coins...

Well, now was his time. Kothelas’ palace was sturdy enough, but the walls hadn’t been repaired in some time. Luck was on his side: while sitting with some friends that afternoon, in the street below, Eudamos had seen his king on the balcony. There had been one of the oldest pages with him, his latest lover, and they had been alone; it was easy to guess this led to the apartments of Philippos of Makedonia.

Eudamos had nothing against him, he thought as he began his climb. It was nothing personal. He was just sick of poverty, and the sieges of Byzantion and Perinthos had convinced him that war was too dangerous a trade for him. He disliked killing, so better to commit one last murder, and then he’d be done with this life—become a rich man in Persia, marry some pretty girl, and...

Focus, lad. He was lucky the guards were slow tonight. But then, Philippos’ balcony was so high—who could imagine an assassin reaching it? Yet here he was, his fingers gripping the wooden railing.

There were voices inside. The king was quarreling with someone, but the shutters were closed to keep out the winter chill. Eudamos couldn’t make out the words, only a blur of voices. If the gods were kind, Philippos would send the his page away. Then he would be alone, ready for sleep—and he was known to snore after a night of heavy drinking. How convenient…

The shutters were thrown open. Eudamos barely had time to drop back down, his heart pounding wildly. He pressed himself against the wall, hidden in the shadows, hoping it was enough. There was a strange smell in the air, one he couldn’t quite place.

Then a young voice said, “You shouldn’t smoke that. Clearly, hemp doesn’t agree with you.”

Footsteps creaked on the wooden floor, followed by a deeper voice. “Pausanias, you know this is inevitable. You’re not even old news at this point—you’re stale news.”

“Who cares? Aren’t we happy together?”

“That’s not the point.”

“Then what is the point?”

I don’t give a fuck about your point, just move, Eudamos thought as his fingers began to ache. The air was bitterly cold, and wouldn’t it be stupid to fall to his death just because these two idiots had decided to have a lover’s quarrel on this balcony while he was hanging there?

“The point,” Philippos answered, “is that you are becoming a laughingstock. You’re getting too old for this.”

“I don’t care if they laugh.”

“I’m sure your father will care.”

“Are you sleeping with my father?”

“You’re drunk. Go to sleep—not here, with the other pages. We’ll discuss this tomorrow.”

His tone was final.

Eudamos clenched his teeth. If only the man would just go back to his room, he could finally pull himself up and catch his breath. Then he’d reach for the dagger and…

He heard the shutters close. He started moving again, swinging, pulling himself up, and…

The king was still on the fucking balcony, staring straight at him with what looked like an amused smile.

Eudamos froze.

There were still footsteps inside, the sound of the lad Philippos had been quarreling with… but why wasn’t he shouting for help? He was unarmed.

He said nothing.

Instead, he lifted a finger to his lips. Silence.

It was such a strange gesture that Eudamos, very slowly, finally hoisted himself over the railing and stood on the balcony.

A door slammed inside.

Then all was silent—except for the sound of the lock clicking on the shutters.

The lock was on the inside.

“You wanted to see me?” the king asked.

It was a moonless night. A slim, golden ray of light filtered around the shutters. The city suddenly felt very, very silent. No more soldiers celebrating in the streets, no more female captives wailing for their lost lives, no more ruckus from the palace. Even the gulls were quiet; even the sea and the wind were quiet.

“I, uh… I am not sure,” the assassin stuttered.

“Odd. It is a strange place to reach by accident.”

Philippos was still smiling. It was a benevolent smile, though his eye had a strange purplish glint. Eudamos swallowed—his spite tasted like wine, heavy and sugary. He was suddenly very afraid and grabbed his dagger. He is unarmed. I only have to stab him, and I will be free.

The king’s weight in gold, the Persian envoy had promised.

But now the king walked toward Eudamos, very calm, slowly, and yet somehow, Eudamos did not have time to move. His thoughts were so slow, like a river that turns to mud when its current fails it. I only have to stab him. Once.

He blinked.

His dagger was in the man’s hand now, the man with the purple eyes and the playful smile, and the air smelled like pepper, like honey, like a rich man’s party when so much wine was spilled on the floor that one can’t make out the colors of the stones in the mosaic.

“Did you want to kill me?”

No, I came here to rob you. It was the only lie that could work, that might save him from torture before his execution…

“Yes,” Eudamos heard himself say.

“Why?”

“I was bought.”

“By whom?”

“The Persians.”

He blinked.

He hadn’t meant to say that. He couldn’t remember how his dagger had ended up in Philippos’ hands, who was now studying it as if there was absolutely nothing strange, nothing wrong there…

“Why did you take their money?”

“I wanted to be rich. To have a pretty wife and oxen. Maybe a vineyard.”

“I understand. What I would give for one pretty wife and some horses and a vineyard!”

The king flashed a smile, and then he was laughing. Eudamos found himself laughing too. The man was charming, really, for someone he had meant to murder. For one moment, he felt like he had met his greatest friend.

Philippos put a hand on his shoulder and asked him who had paid him. The names of the men, their looks, where they met. There was no reason not to answer; just a pleasant warmth that washed away all the worries.

“You are so very kind, friend,” Philippos said. He sounded drunk, but then, so did Eudamos. “Now, I think you should go home. A soldier’s life doesn’t suit you.”

“Yes,” Eudamos admitted. “I hate it.”

“My poor friend. Look, you can go home. From here, just walk straight to the seaside.”

“Right, straight to the seaside.”

“Then keep going…”

“… into the sea?”

“Yes,” Philippos agreed. “Into the sea. Swim home.”

“But I don’t know how to swim.”

The man pulled Eudamos close, like a true friend, and told him, half speaking, half laughing, that it wasn’t that much of a problem.

“Most men float, you know.”

And then, with a long smile that showed a lot of teeth: “Sometimes, some kind god even turns them into dolphins.”

Some last spark of self-preservation flared through the haze. Eudamos didn’t know how to swim. He didn’t, and…

The purple glint in the king’s eye flashed blood red. The man never stopped smiling, but his voice turned odd, as if two people were speaking now: a deep, masculine voice and another, softer, almost that of a woman.

“Go. To the sea.”

So he went.

***

In the morning, Philippos woke up with a splitting headache and swore never to smoke hemp ever again. He suspected even his beloved licorice would do nothing for his stomach. With a groan, he remembered his quarrel with Pausanias. The lad was right, of course: he was beautiful, smart, talented in bed, though his most endearing quality was his wicked sense of humor.

But Pausanias was getting too old.

“Boys!” he shouted, loudly enough for the pages of the morning shift to come inside and bring his breakfast. Some water, food, and a good cup of red, and he would be ready to start his day.

When he went down, his secretary, Eumenes, was already there with the news from the night. Philippos just hoped no one had misbehaved in town; somehow, he was in no mood for punishment today.

“Only one incident of note,” Eumenes told his king. “One of our soldiers was found dead this morning. His body was floating by the docks. Should I ask for a discreet investigation?”

Philippos rubbed his pounding temples. Somehow, the picture of a floating body reminded him of something… then he shook himself and remembered.

“No,” he decided. “He was probably drunk and fell. Focus on getting us a good deal for the supplies. I don’t want these merchants robbing us just because it’s winter.”

When the most urgent matters were sorted, he went back to his room alone. It was a quick search to retrieve the dagger from the night before. Now he knew the encounter had happened; for with Dionysos, one never knew. There were things Philippos did when he was in the god’s embrace that he couldn’t recall at all. He would have to send the intel in his next letter to Olympias. She would know what to make of it and wouldn’t wonder how he knew, unlike his men in Odessos.

“Well, friend,” he murmured, looking at his reflection in the blade, “I didn’t lie, did I? You did float, in the end.”

#my art#art commisions#tagamemnon#Philip II of Macedon#Philippos of Makedonia#ancient history#antiquity

56 notes

·

View notes