#Perdikkas II of Macedon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

What should we make of Alexander I and Perdiccas II both having long 40+ years long reigns, only for all of their successors having substantially shorter ones? And, if you are in the mood, who do you think was the better ruler between the two?

Alexander I and Perdikkas II

First, I thought I’d mention one of the cool things to come out of the recent ATG conference is a plan to produce an edited collection: Alexander I and the Making of Macedon. It’ll be a while, but if I can get us a publisher, I’ve got the contributors.

Also of note, Sabine Müller and Johannes Heinrichs are producing a monograph on Alexander I in English. She has a great one on Perdikkas but it’s in German, so I was very happy to hear this.

Finally, I've got a number of racked-up Asks. This answer will answer about three of them. I'll link it to the other questions. :-)

To the questions: it’s really hard to compare Alexander I and Perdikkas II simply because they were dealing with very different circumstances. Alexander I had Persian assistance holding the throne, while Perdikkas was tossed off his throne at least once.

The biggest difficulty is a source problem. ALL our info about these guys (outside archaeology) comes from Greeks, who were chiefly interested in them only when they intersected with the southern Greek world. There’s a fair bit about Alex I’s internal politicking that we just don’t know. What we call “Lower Macedon” probably only goes back a couple generations, despite the mythical king list. We find a MARKED change in burial practices c. 570 BCE, which is before Persians were mucking around up there. This suggests a change—or more likely consolidation—in the lowland Macedonian ruling elite, both west and a bit east of the Axios River.

If Alexander I took over c. 500-495 (coin above), and his father Amyntas (about whom we know nothing but a name) ruled for 20/30-ish years before, then Alexander’ grandfather (Alketas) or great-grandfather (Airopos) would have consolidated the area around Aigai. Yet ALL names before Amyntas I are essentially fictional. Certainly the “founder’s” name changed across time. It’s Perdikkas when we first hear of it in Herodotos, but may have shifted to Archelaos later (see Euripides’s play of that name). Later yet (under Philip), it seems to have become Karanos. If Bill Greenwalt’s theories are right. This is not a real person in any historical sense.

The problem with dating Alexander I is that we neither know for sure when he took the throne nor when he died. It was convenient for Alexander to blame his father for any concessions to the Persians, but he—not Amyntas—married his sister Gygaia to a Persian (Bubares, son of Magabazus and distantly royal).* More likely he was already on the throne in the 490s but may have been quite young. He seems to have used the Persian presence to further consolidate the (new) Macedonian kingdom—against Paionians and others—adding territory as far away as Amphipolis, at least temporarily, and thus, getting hold of both silver and gold mines to mint coins. The Echedoros River also held gold. All the gold in pre-Alexander Macedonia was pacer mining (panning), not from the gold mines of Mt. Pangaion. Yet gold, while present in the rivers, only became important in graves in Macedonia c. 570…it’s part of that startling shift in burials that we see.

We also don’t know exactly when Alexander I died and Perdikkas took over. He was still king at the end of the Persian Wars in 479/78, but dead by 450. His death may have been closer to 460, or even earlier. So his reign was probably more like 30-35 years. Perdikkas perhaps reigned longest of all—one reason he’s exceptional. I wonder if the Peloponnesian War itself may have contributed to his success: for all he had his challengers, if Macedon wanted to survive as an independent political entity, they needed to rally around him.

Yet he faced his share of opposition from other Argeads as well as the very powerful Upper Macedonian kingdoms of Lynkestis (Lynkis) and Elimeia, not to mention predatory Illyrians. That’s why Perdikkas sought an alliance with Brasidas of Sparta, but apparently couldn’t even control his own troops enough to keep them from deserting when facing Illyrians. That earned Brasidas’s wrath. As a result, Perdikkas (coin below) had to make nice with Athens.

That’s just one example of Perdikkas’s deal-making during the war. He had quite a job of diplomatic shuffling—no doubt learned from Daddy Alexander. Neither had a kingdom anywhere near strong enough to fend off Persia, or Athens and Sparta later. The fact Perdikkas didn’t end up a client king to either Sparta or Athens is a testament to his diplomatic skill.

Perdikkas’s eldest son Archelaos wasn’t the “illegitimate” son of a slave but of a lesser wife, which is why the younger (unnamed) son initially inherited. Archelaos quickly did away with him (plus an uncle and cousin), then proceeded to continue the modernizing work of his father and grandfather. Until he got run through in a hunting “accident.” After that, the kingdom dissolved into a mess.

The problem of a fast turn-over of rule owed to their inheritance system: any Argead had a claim on the throne. Kings also practiced royal polygamy, although two wives (at most three) seems to have been typical until Philip II. In some ways, it worked well, as it produced multiple heirs from which a strong king could emerge (by surviving).

That was also its problem: no clear method of succession, even if the sons of higher-status mothers apparently had a leg-up. Perdikkas himself was not Alexander’s eldest son. He had two older brothers and two younger ones. Yet either his mother was the most prominent or he showed the most promise (or both). Despite Archelaos’s age and apparent ability, he was initially passed over, although Plato (who tells the story) means to paint Archelaos poorly. That doesn’t mean he didn’t kill competing Argeads to take the throne. So had his father, and probably grandfather too (we just don’t hear about it).

Yet Archelaos’s unexpected death led to a continuing crisis until Amyntas III, Phil’s dad, took and kept the throne. He came from a collateral Argead line descended from Alexander I’s youngest son. The other lines killed each other off. For all Amyntas wasn’t a terribly prepossessing king, he managed not to die. But he, too, was run off his throne at least once, maybe twice. When he did die, it was in his bed of old age—not a common thing for Macedonian kings. His reign was the first tolerably long one after Archelaos, over 20 years.

By the time Philip came to the throne, there weren’t many Argeads left thanks to the catch-as-catch-can method of succession: Philip’s two older brothers were dead and all three of his half-brothers. It was down to just him and his brother Perdikkas III’s infant son: Amyntas.

This is the inevitable problem when lacking a clear succession. Yet a clear succession can create its own problems with incompetent heirs, who don’t always recognize they’re incompetent. The free-for-all gave a better shot at a strong king—ostensibly why it developed—but it also meant the kingdom ran out of “spares” after a couple generations. They went from more Argeads than you could shake a stick at following Alexander I’s death, down to just three at Philip’s death, and two at Alexander’s death** in a matter of 5-6 generations. Within those 5-6 generations, 12-14 kings reigned! And we have no idea how many brothers/cousins/uncles Alexander I had, and perhaps killed, before he became king. We hear only about the one sister.

Stability was not a hallmark of the Argead dynasty.

——

* The story of Alexander killing Persian emissaries is much later fictional propaganda. Didn’t happen.

* Alexander’s son Herakles by Barsine might count as a third, but the army doesn’t seem to have considered him viable for whatever reason.

#ancient Macedon#ancient macedonia#Argead Macedonia#Temenids#Argeads#Alexander I of Macedon#Perdikkas II of Macedon#Gygaia#Archelaos of Macedonia#Philip II of Macedonia#Philip of Macedon#Alexander the Great#ancient Greece#Persian Wars#Greco-Persian Wars#Peloponnesian War#Brasidas of Sparta#Classics#tagamemnon#asks#Early Macedonian History

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A house stained with murder

"Should I wait until he murders me, like a lamb ready for slaughter? I don't want to be a lamb. I want to be cruel and terrifying, I want to send him the plague and I want him to die and to feed his corpse to beasts."

(Art by the fabulous Kloh.eh for La Flèche d'Artémis: Philippos haunted by the Erinyes.)

There is one thing that surprises me, about the fictions dealing with Philip II of Macedon: how unimportant it seems that he killed three of his brothers. Perhaps that's because fratricide and murdering family members is an habit of his clan, perhaps that's because it happened before Alexander enters the story.

It is strange, to me, because this is the kind of crimes that fuelled tragedies.

Let's dwelve into the fratricides, and why I think Alexander's family is perfect to write a tragedy.

Let's go back to his youth. For clarity, I use the name Philip when talking about the historical king of Macedon, and Philippos when I talk about the character in my novel.

Philip had five, or maybe six brothers who reached adulthood. His father reigned for a long time, in a country that had been wrecked by infighting: in one scene of my novel, Parmenion, aged sixty, tells Alexandros eleven king claimed the throne since he was born. That's a rather high number, considering two of them, Philipos and his father, were long lasting.

I said maybe. There's a man called Ptolemaios of Aloros who may have been an elder brother, or maybe just an in law. It's unclear, but it's rather important; at least, the gods would think it's important.

Here is how the story beggins.

Young Philippos is eleven, maybe twelve, when his father dies. He's only the third boy of the king's most powerful wife, a child without the beauty of his elder Alexandros and without the smartness of Perdikkas, the second boy. Alexandros ascends the throne: he's the eldest. And then things don't go as planned; or perhaps, they go as things usually go in Makedonia, and there's tribute to be paid, and the young king, barely old enough to be acclaimed, can't pay it.

So he sends his brother as a hostage. That's the first time, but not the last.

And then he dies.

Philippos comes back home. There's chaos, of a kind. His brother was murdered by Ptolemaios of Aloros, everyone knows that - and Ptolemaios is the new regent, and has married Philippos' mother.

What happens next looks like it's inevitable. What keeps Ptolemaios from murdering young Perdikkas, the new king, like he murdered Alexandros? And the next step would be, obviously, to get rid of Philippos once Perdikkas is gone. But the great city of Thebai is asking for an hostage, because it's the biggest power in Greece and of complicated politics Philippos missed while he was hostage.

But, well, he's thirteen, it's not like anyone cares about what he thinks, when he's shipped to Thebai as an hostage. Again.

What happens next? Who dies first? Should Ptolemaios murder Perdikkas? Or maybe kill the one that's in Thebai first? In both cases, Philippos dies before he reaches adulthood.

In the end, he doesn't. Unexpectedly, young Perdikkas wins and murders Ptolemaios. Was Ptolemaios a brother? If he was, that's two fratricides already. But it takes three years to get to that. Three years of whispers in the night: when is he going to kill me? Will he try to poison me, to make it look like it was mere sickness? A knife in a back alley? Can he reach me here, in Thebai?

Should I wait, weaponless, or should I try to defend myself? ... how do you defend yourself when you are still a boy?

You have the gods. The gods answer, sometimes.

Beware of what you ask.

Ptolemaios will win. He's older, he murdered one king already. Perdikkas will die. It's written, isn't it?

What do you want to ask the gods? What would ensure your survival, what would please the few peoples who believe in you to fight for the throne once Perdikkas is gone and it's your turn?

So you ask: I want to be the most glorious king Makedonia ever knew.

And the gods answer: yes.

But then, Perdikkas wins.

He wins, and the gods promised you his throne.

Because the truth is, the stain was there, from the start. Brothers and cousins have been killing each other for so long, there must be a curse attached to the family. Whispering: should you kill him, before he kills you?

Ptolemaios is gone. Perdikkas is the king. Philippos returns home.

Perdikkas dies during a battle, unexpectedly. Was that his destiny, or did the god grant Philippos what he asked for, but doesn't want anymore?

Did he kill his brother?

He still has three half brothers.

Years after the blood bath, he's forty, and his son Alexandros is finally old enough to join him on campaign. He's a bright boy, promising. So is Philippos' nephew Amyntas. He likes him, and like Alexandros, he would probably be a good king. Philippos knows that: he raised this nephew, almost like a son.

But he hears them. The whispers. Except this time they aren't targetting him, because he has no more half brothers to murder and no more brother to betray: kill him, before he kills you.

His children are going to slaughter each other, and no matter how much he regrets his own crimes, or how many time he got initiated into the gods know how many cults to wash himself of the eternal stain of brothers killing brothers, he knows. He knows there's no way to keep them safe from each other.

Because they are all cursed, all of them, until the end of their line.

PS: My Philippos was actually a nice kid so maybe IDK, when Parmenion met him in Thebai, he should have grabbed him and moved to Spain to raise horses in peace, and everyone would have been happier and less depressed.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Macedonian coins, Perdikkas II 413 BC (top), Alexander I 454 BC (bottom)

#ancient greece#macedon#ancient greek coins#greek coins#ancient coins#coins#antiquities#alexander i#perdikkas ii

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Greek names of kings of Macedon and Diadochi

1. ALEXANDROS m Ancient Greek (ALEXANDER Latinized) Pronounced: al-eg-ZAN-dur From the Greek name Alexandros, which meant ‘defending men’ from Greek alexein ‘to defend, protect, help’ and aner ‘man’ (genitive andros). Alexander the Great, King of Macedon, is the most famous bearer of this name. In the 4th century BC he built a huge empire out of Greece, Egypt, Persia, and parts of India. The name was borne by five kings of Macedon.

2. PHILIPPOS m Ancient Greek (PHILIP Latinized) Pronounced: FIL-ip From the Greek name Philippos which means ‘friend of horses’, composed of the elements philos ‘friend’ and hippos ‘horse’. The name was borne by five kings of Macedon, including Philip II the father of Alexander the Great.

3. AEROPOS m Ancient Greek, Greek Mythology Male form of Aerope who in Greek mythology was the wife of King Atreus of Mycenae. Aeropos was also the son of Aerope, daughter of Kepheus: ‘Ares, the Tegeans say, mated with Aerope, daughter of Kepheus (king of Tegea), the son of Aleos. She died in giving birth to a child, Aeropos, who clung to his mother even when she was dead, and sucked great abundance of milk from her breasts. Now this took place by the will of Ares.’ (Pausanias 8.44.) The name was borne by two kings of Macedon.

4. ALKETAS m Ancient Greek (ALCAEUS Latinized) Pronounced: al-SEE-us Derived from Greek alke meaning ‘strength’. This was the name of a 7th-century BC lyric poet from the island of Lesbos.

5. AMYNTAS m Ancient Greek Derived from Greek amyntor meaning ‘defender’. The name was borne by three kings of Macedon.

6. ANTIGONOS m Ancient Greek (ANTIGONUS Latinized) Pronounced: an-TIG-o-nus Means ‘like the ancestor’ from Greek anti ‘like’ and goneus ‘ancestor’. This was the name of one of Alexander the Great’s generals. After Alexander died, he took control of most of Asia Minor. He was known as Antigonus ‘Monophthalmos’ (‘the One-Eyed’). Antigonos II (ruled 277-239 BC) was known as ‘Gonatos’ (‘knee, kneel’).

7. ANTIPATROS m Ancient Greek (ANTIPATER Latinized) Pronounced: an-TI-pa-tur From the Greek name Antipatros, which meant ‘like the father’ from Greek anti ‘like’ and pater ‘father’. This was the name of an officer of Alexander the Great, who became the regent of Macedon during Alexander’s absence.

8. ARCHELAOS m Ancient Greek (ARCHELAUS Latinized) Pronounced: ar-kee-LAY-us Latinized form of the Greek name Archelaos, which meant ‘master of the people’ from arche ‘master’ and laos ‘people’. It was also the name of the 7th Spartan king who came in the throne of Sparti in 886 BC, long before the establishment of the Macedonian state.

9. ARGAIOS m Greek Mythology (ARGUS Latinized) Derived from Greek argos meaning ‘glistening, shining’. In Greek myth this name belongs to both the man who built the Argo and a man with a hundred eyes. The name was borne by three kings of Macedon.

10. DEMETRIOS m Ancient Greek (DEMETRIUS Latinized) Latin form of the Greek name Demetrios, which was derived from the name of the Greek goddess Demeter. Kings of Macedon and the Seleucid kingdom have had this name. Demetrios I (ruled 309-301 BC) was known as ‘Poliorketes’ (the ‘Beseiger’).

11. KARANOS m Ancient Greek (CARANUS Latinized) Derived from the archaic Greek word ‘koiranos’ or ‘karanon”, meaning ‘ruler’, ‘leader’ or ‘king’. Both words stem from the same archaic Doric root ‘kara’ meaning head, hence leader, royal master. The word ‘koiranos’ already had the meaning of ruler or king in Homer. Karanos is the name of the founder of the Argead dynasty of the Kings of Macedon.

12. KASSANDROS m Greek Mythology (CASSANDER Latinized) Pronounced: ka-SAN-dros Possibly means ‘shining upon man’, derived from Greek kekasmai ‘to shine’ and aner ‘man’ (genitive andros). In Greek myth Cassandra was a Trojan princess, the daughter of Priam and Hecuba. She was given the gift of prophecy by Apollo, but when she spurned his advances he cursed her so nobody would believe her prophecies. The name of a king of Macedon.

13. KOINOS m Ancient Greek Derived from Greek koinos meaning ‘usual, common’. An Argead king of Macedon in the 8th century BC.

14. LYSIMACHOS m Ancient Greek (LYSIMACHUS Latinized) Means ‘a loosening of battle’ from Greek lysis ‘a release, loosening’ and mache ‘battle’. This was the name of one of Alexander the Great’s generals. After Alexander’s death Lysimachus took control of Thrace.

15. SELEUKOS m Ancient Greek (SELEUCUS Latinized) Means ‘to be light’, ‘to be white’, derived from the Greek word leukos meaning ‘white, bright’. This was the name of one of Alexander’s generals that claimed most of Asia and founded the Seleucid dynasty after the death of Alexander in Babylon.

16. ARRIDHAIOS m Ancient Greek Son of Philip II and later king of Macedon. The greek etymology is Ari (= much) + adj Daios (= terrifying). Its full meaning is “too terrifying”. Its Aeolian type is Arribaeos.

17. ORESTES m Greek Mythology Pronounced: o-RES-teez Derived from Greek orestais meaning ‘of the mountains’. In Greek myth he was the son of Agamemnon. He killed his mother Clytemnestra after she killed his father. The name of a king of Macedon (ruled 399-396 BC).

18. PAUSANIAS m Ancient Greek King of Macedon in 393 BC. Pausanias was also the name of the Spartan king at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC, and the name of the Greek traveller, geographer and writer whose most famous work is ‘Description of Greece’, and also the name of the man who assassinated Philip II of Macedon in 336 BC.

19. PERDIKKAS m Ancient Greek (PERDICCAS Latinized) Derived from Greek perdika meaning ‘partridge’. Perdikkas I is presented as founder of the kingdom of Macedon in Herodotus 8.137. The name was borne by three kings of Macedon.

20. PERSEUS m Greek Mythology Pronounced: PUR-see-us It derives from Greek verb pertho meaning ‘to destroy, conquer’. Its full meaning is the “conqueror”. Perseus was a hero in Greek legend. He killed Medusa, who was so ugly that anyone who gazed upon her was turned to stone, by looking at her in the reflection of his shield and slaying her in her sleep. The name of a king of Macedon (ruled 179-168 BC).

21. PTOLEMEOS m Ancient Greek (PTOLEMY Latinized) Pronounced: TAWL-e-mee Derived from Greek polemeios meaning ‘aggressive’ or ‘warlike’. Ptolemy was the name of several Greco-Egyptian rulers of Egypt, all descendents of Ptolemy I, one of Alexander the Great’s generals. This was also the name of a Greek astronomer. Ptolemy ‘Keraunos’ (ruled 281-279 BC) is named after the lighting bolt thrown by Zeus.

22. TYRIMMAS m Greek Mythology Tyrimmas, an Argead king of Macedon and son of Coenus. Also known as Temenus. In Greek mythology, Temenus was the son of Aristomaches and a great-great grandson of Herakles. He became king of Argos. Tyrimmas was also a man from Epirus and father of Evippe, who consorted with Odysseus (Parthenius of Nicaea, Love Romances, 3.1). Its full meaning is “the one who loves cheese”.

QUEENS AND ROYAL FAMILY

23. EURYDIKE f Greek Mythology (EURYDICE Latinized) Means ‘wide justice’ from Greek eurys ‘wide’ and dike ‘justice’. In Greek myth she was the wife of Orpheus. Her husband tried to rescue her from Hades, but he failed when he disobeyed the condition that he not look back upon her on their way out. Name of the mother of Philip II of Macedon.

24. BERENIKE f Ancient Greek (BERENICE Latinized) Pronounced: ber-e-NIE-see Means ‘bringing victory’ from pherein ‘to bring’ and nike ‘victory’. This name was common among the Ptolemy ruling family of Egypt.

25. KLEOPATRA f Ancient Greek (CLEOPATRA Latinized), English Pronounced: klee-o-PAT-ra Means ‘glory of the father’ from Greek kleos ‘glory’ combined with patros ‘of the father’. In the Iliad, the name of the wife of Meleager of Aetolia. This was also the name of queens of Egypt from the Ptolemaic royal family, including Cleopatra VII, the mistress of both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. After being defeated by Augustus she committed suicide by allowing herself to be bitten by an asp. Also the name of a bride of Philip II of Macedon.

26. CYNNA f Ancient Greek Half-sister of Alexander the great. Her name derives from the adj. of doric dialect Cyna (= tough).

27. THESSALONIKI f Ancient Greek Means ‘victory over the Thessalians’, from the name of the region of Thessaly and niki, meaning ‘victory’. Name of Alexander the Great’s step sister and of the city of Thessaloniki which was named after her in 315 BC.

GENERALS, SOLDIERS, PHILOSOPHERS AND OTHERS

28. PARMENION m ancient Greek The most famous General of Philip and Alexander the great. Another famous bearer of this name was the olympic winner Parmenion of Mitiline. His name derives from the name Parmenon + the ending -ion used to note descendancy. It means the “descedant of Parmenon”.

29. PEUKESTAS m Ancient Greek He saved Alexander the Great in India. One of the most known Macedonians. His name derives from Πευκής (= sharp) + the Doric ending -tas. Its full meaning is the “one who is sharp”.

30. ARISTOPHANES m Ancient Greek Derived from the Greek elements aristos ‘best’ and phanes ‘appearing’. The name of one of Alexander the Great’s personal body guard who was present during the murder of Cleitus. (Plutarch, Alexander, ‘The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans’). This was also the name of a 5th-century BC Athenian playwright.

31. KORRAGOS m Ancient Greek The Macedonian who challenged into a fight the Olympic winner Dioxippos and lost. His name derives from Koira (= army) + ago (= lead). Korragos has the meaning of “the leader of the army”.

32. ARISTON m Ancient Greek Derived from Greek aristos meaning ‘the best’. The name of a Macedonian officer on campaign with Alexander the Great (Arrian, Anabasis, Book II, 9 and Book III, 11, 14).

33. KLEITUS m Ancient Greek (CLEITUS Latinized) Means ‘calling forth’ or ‘summoned’ in Greek. A phalanx battalion commander in Alexander the Great’s army at the Battle of Hydaspes. Also the name of Alexander’s nurse’s brother, who severed the arm of the Persian Spithridates at the Battle of the Granicus.

34. HEPHAISTION m Greek Mythology Derived from Hephaistos (‘Hephaestus’ Latinized) who in Greek mythology was the god of fire and forging and one of the twelve Olympian deities. Hephaistos in Greek denotes a ‘furnace’ or ‘volcano’. Hephaistion was the companion and closest friend of Alexander the Great. He was also known as ‘Philalexandros’ (‘friend of Alexander’).

35. HERAKLEIDES m Ancient Greek (HERACLEIDES Latinized) Perhaps means ‘key of Hera’ from the name of the goddess Hera combined with Greek kleis ‘key’ or kleidon ‘little key’. The name of two Macedonian soldiers on campaign with Alexander the Great (Arrian, Anabasis, Book I, 2; Book III, 11 and Book VII, 16).

36. KRATEROS m Ancient Greek (CRATERUS Latinized) Derived from Greek adj. Κρατερός (= Powerful). This was the name of one of Alexander the Great’s generals. A friend of Alexander the Great, he was also known as ‘Philobasileus’ (‘friend of the King’).

37. NEOPTOLEMOS m Greek Mythology (NEOPTOLEMUS Latinized) Means ‘new war’, derived from Greek neos ‘new’ and polemos ‘war’. In Greek legend this was the name of the son of Achilles, brought into the Trojan War because it was prophesied the Greeks could not win it unless he was present. After the war he was slain by Orestes because of his marriage to Hermione. Neoptolemos was believed to be the ancestor of Alexander the Great on his mother’s (Olympias’) side (Plutarch). The name of two Macedonian soldiers during Alexander’s campaigns (Arrian, Anabasis, Book I, 6 and Book II, 27).

38. PHILOTAS m Ancient Greek From Greek philotes meaning ‘friendship’. Son of Parmenion and a commander of Alexander the Great’s Companion cavalry.

39. PHILOXENOS m Ancient Greek Meaning ‘friend of strangers’ derived from Greek philos meaning friend and xenos meaning ‘stranger, foreigner’. The name of a Macedonian soldier on campaign with Alexander the Great (Arrian, Anabasis, Book III, 6).

40. MENELAOS m Greek Mythology (MENELAUS Latinized) Means ‘withstanding the people’ from Greek meno ‘to last, to withstand’ and laos ‘the people’. In Greek legend he was a king of Sparta and the husband of Helen. When his wife was taken by Paris, the Greeks besieged the city of Troy in an effort to get her back. After the war Menelaus and Helen settled down to a happy life. Macedonian naval commander during the wars of the Diadochi and brother of Ptolemy Lagos.

41. LAOMEDON m ancient greek Friend from boyhood of Alexander and later Satrap. His names derives from the greek noun laos (λαός = “people” + medon (μέδω = “the one who governs”)

42. POLYPERCHON Ancient Greek Macedonian, Son of Simmias His name derives from the greek word ‘Πολύ’ (=much) + σπέρχω (= rush).

43. HEGELOCHOS m (HEGELOCHUS Latinized) Known as the conspirator. His name derives from the greek verb (ηγέομαι = “walking ahead” + greek noun λόχος = “set up ambush”).

44. POLEMON m ancient Greek From the house of Andromenes. Brother of Attalos. Means in greek “the one who is fighting in war”.

45. AUTODIKOS m ancient greek Somatophylax of Philip III. His name in greek means “the one who takes the law into his (own) hands”

46. BALAKROS m ancient Greek Son of Nicanor. We already know Macedonians usually used a “beta” instead of a “phi” which was used by Atheneans (eg. “belekys” instead of “pelekys”, “balakros” instead of “falakros”). “Falakros” has the meaning of “bald”.

47. NIKANOR (Nικάνωρ m ancient Greek; Latin: Nicanor) means “victor” – from Nike (Νικη) meaning “victory”. Nicanor was the name of the father of Balakras. He was a distinguished Macedonian during the reign of Phillip II. Another Nicanor was the son of Parmenion and brother of Philotas. He was a distinguished officer (commander of the Hypaspists) in the service of Alexander the Great. He died of disease in Bactria in 330 BC.

48. LEONNATOS m ancient Greek One of the somatophylakes of Alexander. His name derives from Leon (= Lion) + the root Nat of noun Nator (= dashing). The full meaning is “Dashing like the lion”.

49. KRITOLAOS m ancient Hellinic He was a potter from Pella. His name was discovered in amphoras in Pella during 1980-87. His name derives from Κρίτος (= the chosen) + Λαός (= the people). Its full meaning is “the chosen of the people”.

50. ZOILOS m ancient Hellinic Father of Myleas from Beroia – From zo-e (ΖΩΗ) indicating ‘lively’, ‘vivacious’. Hence the Italian ‘Zoilo’

51. ZEUXIS m ancient Hellinic Name of a Macedonian commander of Lydia in the time of Antigonos III and also the name of a Painter from Heraclea – from ‘zeugnumi’ = ‘to bind’, ‘join together’

52. LEOCHARIS m ancient Hellinic Sculptor – Deriving from ‘Leon’ = ‘lion’ and ‘charis’ = ‘grace’. Literally meaning the ‘lion’s grace’.

53. DEINOKRATIS m ancient Hellinic Helped Alexander to create Alexandria in Egypt. From ‘deinow’ = ‘to make terrible’ and ‘kratein’ = “to rule” Obviously indicating a ‘terrible ruler’

54. ADMETOS (Άδμητος) m Ancient Greek derive from the word a+damaw(damazw) and mean tameless,obstreperous.Damazw mean chasten, prevail

55. ANDROTIMOS (Ανδρότιμος) m Ancient Greek derive from the words andreios (brave, courageous) and timitis(honest, upright )

56. PEITHON m Ancient Greek Means “the one who persuades”. It was a common name among Macedonians and the most famous holders of that names were Peithon, son of Sosicles, responsible for the royal pages and Peithon, son of Krateuas, a marshal of Alexander the Great.

57. SOSTRATOS m Ancient Greek Derives from the Greek words “Σως (=safe) +Στρατος (=army)”. He was son of Amyntas and was executed as a conspirator.

58. DIMNOS m Ancient Greek Derives from the greek verb “δειμαίνω (= i have fear). One of the conspirators.

59. TIMANDROS m Ancient Greek Meaning “Man’s honour”. It derives from the greek words “Τιμή (=honour) + Άνδρας (=man). One of the commanders of regular Hypaspistes.

60. TLEPOLEMOS ,(τληπόλεμος) m Ancient Greek Derives from greek words “τλήμων (=brave) + πόλεμος (=war)”. In greek mythology Tlepolemos was a son of Heracles. In alexanders era, Tlepolemos was appointed Satrap of Carmania from Alexander the Great.

61. AXIOS (Άξιος) m ancient Greek Meaning “capable”. His name was found on one inscription along with his patronymic “Άξιος Αντιγόνου Μακεδών”.

62. THEOXENOS (Θεόξενος) ancient Greek Derives from greek words “θεός (=god) + ξένος (=foreigner).His name appears as a donator of the Apollo temple along with his patronymic and city of origin(Θεόξενος Αισχρίωνος Κασσανδρεύς).

63. MITRON (Μήτρων) m ancient Greek Derives from the greek word “Μήτηρ (=Mother)”. Mitron of Macedon appears in a inscription as a donator

64. KLEOCHARIS (Κλεοχάρης) M ancient greek Derives from greek words “Κλέος (=fame) + “Χάρις (=Grace). Kleocharis, son of Pytheas from Amphipoli was a Macedonian honoured in the city of Eretria at the time of Demetrius son of Antigonus.

65. PREPELAOS (Πρεπέλαος) m, ancient Greek Derives from greek words “πρέπω (=be distinguished) + λαος (=people). He was a general of Kassander.

66. HIPPOLOCHOS (Ιππόλοχος) m, ancient Greek Derives from the greek words “Ίππος” (= horse) + “Λόχος”(=set up ambush). Hippolochos was a Macedonian historian (ca. 300 B.C.)

67. ALEXARCHOS (Αλέξαρχος) m, ancient Greek Derives from Greek “Αλέξω” (=defend, protect, help) + “Αρχος ” (= master). Alexarchos was brother of Cassandros.

68. ASCLEPIODOROS (Ασκληπιοδορος) m Ancient Greek Derives from the greek words Asclepios (= cut up) + Doro (=Gift). Asclepios was the name of the god of healing and medicine in Greek mythology. Asclepiodoros was a prominent Macedonian, son of Eunikos from Pella. Another Asclepiodoros in Alexander’s army was son of Timandros.

69. KALLINES (Καλλινης) m Ancient Greek Derives from greek words kalli + nao (=stream beautifully). He was a Macedonian, officer of companions.

70. PLEISTARHOS (Πλείσταρχος) m ancient Greek Derives from the greek words Pleistos (=too much) + Arhos ((= master). He was younger brother of Cassander.

71. POLYKLES (Πολυκλής) m ancient Greek Derives from the words Poli (=city) + Kleos (glory). Macedonian who served as Strategos of Antipater.

72. POLYDAMAS (Πολυδάμας) m ancient Greek The translation of his name means “the one who subordinates a city”. One Hetairos.

73. APOLLOPHANES (Απολλοφάνης) m ancient greek. His name derives from the greek verb “απολλυμι” (=to destroy) and φαίνομαι (= appear to be). Apollophanes was a prominent Macedonian who was appointed Satrap of Oreitae.

74. ARCHIAS (Αρχίας) m ancient Greek His name derive from greek verb Άρχω (=head or be in command). Archias was one of the Macedonian trierarchs in Hydaspes river.

75. ARCHESILAOS (Αρχεσίλαος) m ancient Greek His name derive from greek verb Άρχω (=head or be in command) + Λαος (= people). Archesilaos was a Macedonian that received the satrapy of Mesopotamia in the settlement of 323.

76. ARETAS (Αρετας) m ancient Greek Derives from the greek word Areti (=virtue). He was commander of Sarissoforoi at Gaugamela.

77. KLEANDROS (Κλέανδρος) m ancient Greek Derives from greek verb Κλέος (=fame) + Ανδρος (=man). He was commander of Archers and was killed in Hallicarnasus in 334 BC.

78. AGESISTRATOS (Αγησίστρατος) m ancient greek Father of Paramonos, a general of Antigonos Doson. His name derives from verb ηγήσομαι ( = lead in command) + στρατος (= army). “Hgisomai” in Doric dialect is “Agisomai”. Its full meaning is “the one who leads the army”

79. AGERROS (Αγερρος) M ancient Greek He was father of Andronikos, general of Alexander. His name derives from the verb αγέρρω (= the one who makes gatherings)

80. AVREAS (Αβρέας) m ancient Greek Officer of Alexander the great. His name derives from the adj. αβρός (=polite)

81. AGATHANOR (Αγαθάνωρ) m ancient Greek Som of Thrasycles. He was priest of Asklepios for about 5 years. His origin was from Beroia as is attested from an inscription. His name derives from the adj. αγαθός (= virtuous) + ανήρ (= man). The full meaning of his name is “Virtuous man”

82. AGAKLES (Αγακλής) m ancient Greek He was son of Simmihos and was from Pella. He is known from a resolution of Aetolians. His name derives from the adj. Αγακλεής (= too glorious)

83. AGASIKLES (Αγασικλής) m ancient Greek Son of Mentor, from Dion of Macedonia. It derives from the verb άγαμαι (= admire) + Κλέος (=fame). Its full meaning is “the one who admires fame”

84. AGGAREOS (Αγγάρεος) m ancient Greek Son of Dalon from Amphipolis. He is known from an inscription of Amphipolis (S.E.G vol 31. ins. 616) It derives from the noun Αγγαρεία (= news)

85. AGELAS (Αγέλας) m ancient Greek Son of Alexander. He was born during the mid-5th BCE and was an ambassador of Macedonians during the treaty between Macedonians and Atheneans. This treaty exists in inscription 89.vol1 Fasc.1 Ed.3″Attic inscrip.” His name was common among Heraclides and Bacchiades. One Agelas was king of Corinth during the first quarter of 5 BCE. His name derives from the verb άγω (= lead) and the noun Λαός (= people or even soldiers (Homeric)). The full meaning is the “one who leads the people/soldiers”.

86. AGIPPOS (Άγιππος) m ancient Greek He was from Beroia of Macedonia and lived during middle 3rd BCE. He is known from an inscription found in Beroia where his name appears as the witness in a slave-freeing. Another case bearing the name Agippos in the Greek world was the father of Timokratos from Zakynthos. The name Agippos derives from the verb άγω (= lead) + the word ίππος (= Horse). Its full meaning is “the one who leads the horse/calvary”.

87. AGLAIANOS (Αγλαϊάνος) m ancient Greek He was from Amphipolis of Macedonia (c. 4th BC) and he is known from an inscription S.E.G vol41., insc. 556 His name consists of aglai- from the verb αγλαϊζω (= honour) and the ending -anos.

88. AGNOTHEOS (Αγνόθεος) m ancient Greek Macedonian, possibly from Pella. His name survived from an inscription found in Pella between 300-250 BCE. (SEG vol46.insc.799) His name derives from Αγνός ( = pure) + Θεός (=God). The full meaning is “the one who has inside a pure god”

89. ATHENAGORAS (Αθηναγόρας) m ancient Greek General of Philip V. He was the general who stopped Dardanian invasion in 199 BC. His name derives from the verb αγορά-ομαι (=deliver a speech) + the name Αθηνά (= Athena).

90. PERIANDROS (Περίανδρος) m ancient Greek Son of the Macedonian historian Marsyas. His name derives from Περί (= too much) + άνηρ (man, brave). Its full meaning is “too brave/man”.

91. LEODISKOS (Λεοντίσκος) m ancient Greek He was son of Ptolemy A’ and Thais, His name derives from Λέων (= lion) + the ending -iskos (=little). His name’s full etymology is “Little Lion”

92. EPHRANOR (Ευφράνωρ) m ancient Greek He was General of Perseas. It derives from the verb Ευφραίνω (= delight). Its full meaning is “the one who delights”.

93. DIONYSOPHON m Ancient Greek It has the meaning “Voice of Dionysos”. The ending -phon is typical among ancient greek names.

MACEDONIAN WOMEN

94. ANTIGONE f ancient Greek Usage: Greek Mythology Pronounced: an-TIG-o-nee Means ‘against birth’ from Greek anti ‘against’ and gone ‘birth’. In Greek legend Antigone was the daughter of Oedipus and Jocasta. King Creon of Thebes declared that her slain brother Polynices was to remain unburied, a great dishonour. She disobeyed and gave him a proper burial, and for this she was sealed alive in a cave. Antigone of Pydna was the mistress of Philotas, the son of Parmenion and commander of Alexander the Great’s Companion cavalry (Plutarch, Alexander, ‘The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans’).

95. VOULOMAGA (Βουλομάγα) f ancient greek Derives from greek words “Βούλομαι (=desire) + άγαν (=too much)”. Her name is found among donators.

96. ATALANTE (Αταλαντη) f ancient Greek Her name means in Greek “without talent”. She was daughter of Orontes, and sister of Perdiccas.

97. AGELAEIA (Αγελαεία) f ancient Greek Wife of Amyntas, from the city of Beroia (S.E.G vol 48. insc. 738) It derives from the adj. Αγέλα-ος ( = the one who belongs to a herd)

98. ATHENAIS (Αθηναϊς) f ancient Greek The name was found on an altar of Heracles Kigagidas in Beroia. It derives from the name Athena and the ending -is meaning “small”. Its whole meaning is “little Athena”.

99. STRATONIKE f Ancient Greek (STRATONICE Latinized) Means ‘victorious army’ from stratos ‘army’ and nike ‘victory’. Sister of King Perdiccas II. “…and Perdiccas afterwards gave his sister Stratonice to Seuthes as he had promised.” (Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, Chapter VIII)

100. THETIMA f Ancient Greek A name from Pella Katadesmos. It has the meaning “she who honors the gods”; the standard Attic form would be Theotimē.

Bibliography:

“Who’s who in the age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander’s Empire” by Waldemar Heckel“The Marshals of Alexander’s empire” by Waldemar Heckel

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Silver tetrobol of Kingdom of Macedonia, struck under Perdikkas II, with horse (obverse) and incuse square containing Macedonian helmet (reverse)

Greek (minted in Macedonia), Classical Period, 446/5-438/7 B.C.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

#Macedonia#Ancient Greece#numismatics#ancient coin#ancient coins#silver#coin#tetrobol#Macedon#Macedonian#Perdikkas II#Classical Period#Greek#MFA Boston

382 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexander the Great Ancient Greek Coin Types VIDEO

Alexander III the Great King of Macedonia Ancient Coins & Related

Alexander the Great was king of the Macedonian Kingdom from 336-323 B.C. His father was Philip II, who gave him the most quality education, including with the famous philosopher Aristotle. Trained in battle with his father Philip, Alexander did not stay in his father’s shadow and went on to create an empire that is has effects on Western Civilization to this day. The types of coins Alexander introduced, including those in gold, silver and bronze, were used as prototypes of the coins struck hundreds of years after his death. Since his coins were so well known and accepted, for hundreds of years, his types were struck by various other rulers and cities. Coins were struck bearing his portrait and name into the ancient Roman times over 500 years later. Very interesting series of ancient coins to collect. See some great examples of them here.

See all the different types of Alexander the Great coins available.

See ALL the Alexander the Great Coins

See SILVER Alexander the Great Coins

See LARGE SILVER Alexander the Great Coins called Tetradrachms

See Alexander the Great Coins as HERCULES

See Alexander the Great coins with SHIELD and HELMET

See Alexander the Great coins with HORSE and Apollo

See Alexander the Great coins with EAGLE and Hercules

See Alexander the Great coins with his famous horse BUCEPHALUS and the only horse that ever has had a city named after it!

See Alexander the Great coins of MACEDONIA KOINON during Roman times

See many of the Different Types of Ancient Alexander the Great coins

The standard reference that is used to identify most of the coins of Alexander the Great is called: The coinage in the name of Alexander the Great and Philip Arrhidaeus: A British Museum catalogue by M. Jessop Price. So that is what is usually referenced below every coin you will find in my store.

The Coins:

Philip II Alexander the Great Dad OLYMPIC GAMES Ancient Greek Coin Horse i47408

Greek King Philip II of Macedon 359-336 B.C. Father of Alexander III the Great Bronze 18mm (6.41 grams) Struck circa 356-336 B.C. in the Kingdom of Macedonia Commemorating his Olympic Games Victory Head of Apollo right, hair bound with tainia. Youth on horse prancing right, ΦIΛIΠΠΟΥ above.* Numismatic Note: Authentic ancient Greek coin of King Philip II of Macedonia, father of Alexander the Great. Fascinating coin referring to his Olympic victories.History and Meaning of the Coin

During the times of ancient Greeks, horse racing was one of the events various Greek city-states and kingdoms would have intense competition with each other, as it was of great prestige to participate. Before the time of Philip II, the kingdom of Macedonia was considered barbarian and not Greek. Philip II was the first king of Macedon that was accepted for participation in the event, which was a great honor all in itself. It was an even greater honor that Philip’s horses would go on to win two horse-racing events. In 356 B.C., he won the single horse event and then in 348 B.C. chariot pulled by two horses event. As a way to proudly announce, or what some would say propagandize these honors, Philip II placed a reference to these great victories on his coins struck in all three metals of bronze, silver and gold. The ancient historian, Plutarch, wrote “[Philip of Macedon] … had victories of his chariots at Olympia stamped on his coins.”

PHILIP III Alexander the Great Half Brother Silver Tetradrachm Greek Coin i44563

Greek Coin of Macedonian Kingdom Philip III, Arrhidaeus – King of Macedonia: 323-317 B.C. Struck under Perdikkas Silver Tetradrachm 26mm (16.55 grams) Struck circa 323-320 B.C. Reference: Price P205; SNG München 971 Head of Alexander the Great as Hercules right, wearing the lion-skin headdress. ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, Zeus Aetophoros seated left, holding eagle and scepter; head of Sol in field to left; KY below thrown.

ALEXANDER the GREAT 90BC Silver Greek Tetradrachm coin of PELLA Macedon i46268

Greek city of Pella in Macedonia Silver Tetradrachm 27mm (16.70 grams) Struck circa 90-75 B.C. Reference: Sear 1439; Price (Coins of the Macedonians) pl. XVI, 84 Head of Alexander the Great right, with horn of Ammon and flowing hair; MAKEΔΟΝΩΝ beneath, B (reversed) behind. AESILLAS / Q. above club between money-chest and quaestor’s chair; all within olive-wreath.

ALEXANDER III the GREAT Pella Antigonos II Tetradrachm Silver Greek Coin i46302

Greek Coin of Macedonian Kingdom Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia: 336-323 B.C. Struck under Antigonos II Gonatas: Macedonian King: 277-239 B.C. Silver Tetradrachm 27mm (16.80 grams) Pella mint, circa: 275-271 B.C. Reference: Price 621; Müller 230; SNG Copenhagen 713; Mathisen, Administrative VI.6, dies A19/P44 Head of Alexander the Great as Hercules right, wearing the lion-skin headdress. ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ AΛEΞANΔΡOY, Zeus Aetophoros seated left, holding eagle and scepter; Macedonian helmet in field to left; OK monogram below throne.

Celtic Thrace King KAVAROS Silver Greek Coin name of Alexander the Great i41722

KINGS of THRACE, Celtic. Kavaros (the last Gaulish King in Thrace) – King: 230-218 B.C. Silver Tetradrachm 28mm (16.44 grams) Struck at the Kabyle mint circa 230-218 B.C. In the name and types of Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia: 336-323 B.C. Reference: Draganov 874–5 var. (unlisted dies); Price 882; Peykov F2010 Head of Alexander the Great as Hercules right, wearing the lion-skin headdress. ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ AΛEΞANΔΡOY, Zeus Aetophoros seated left, holding eagle and scepter; Artemis Phosphoros in field to left.

ALEXANDER III the GREAT 310BC Hercules Zeus Ancient Silver Greek Coin i46352

Greek Coin of Macedonian Kingdom Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia: 336-323 B.C. under: Antigonos I Monophthalmos. As Strategos of Asia, 320-306/5 BC, or king, 306/5-301 BC Silver Drachm 17mm (4.10 grams) Lampsakos, Struck circa 310-301 B.C. Reference: Price 1423 var. Head of Alexander the Great as Hercules right, wearing the lion-skin headdress. AΛEΞANΔΡOY, Zeus Aetophoros seated left, holding eagle and scepter; mouse in field to left; monogram below throne.

Alexander III the Great as Hercules 336BC Ancient Greek Coin Bow Club i40942

Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia 336-323 B.C. Bronze 18mm (5.39 grams) Struck under Alexander the Great circa 336-323 B.C. Reference: Sear 6739 var. Head of Alexander III the Great as Hero Hercules right, wearing the lion-skin headdress. Hercules’ weapons, bow in bow-case and club, BA in between.

Alexander III the Great as Hercules 336BC Ancient Greek Coin Bow Club i47432

Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia 336-323 B.C. Bronze 19mm (5.18 grams) Struck under Alexander the Great 336-323 B.C. Reference: Sear 6739 var. Head of Hercules right, wearing the lion-skin headdress. Hercules’ weapons, bow in bow-case and club, ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΥ in between.

Alexander III the Great 323BC Shield Helmet Macedonia Ancient Greek Coin i37411

Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia 336-323 B.C. Bronze 16mm (4.37 grams) Uncertain mint in western Asia Minor, Struck circa 323-310 B.C. Reference: Price 2801 Macedonian shield with head of Alexander the Great as Hercules 3/4 facing left in center. Crested helmet; BA across fields.

ALEXANDER III the GREAT 336BC Super Rare Shield Helmet Ancient Greek Coin i38104

Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia 336-323 B.C. Bronze 16mm (3.87 grams) Struck circa 336-323 B.C. Reference: Price 2808 (obverse), Price 2806 (reverse) Macedonian shield with head of Alexander the Great as Hercules right in center. Crested helmet; grain-ear below, BA across fields.

ALEXANDER III the GREAT 325BC Shield Helmet Macedonian Greek Coin RARE i39799

Greek Coin of Macedonian Kingdom Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia 336-323 B.C. Bronze 1/2 Unit 16mm (4.26 grams) Uncertain mint in Macedon. Possible lifetime issue, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon, or Kassander, circa 325-310 B.C. Reference: Price 417 Macedonian shield; around, five double crescents with five pellets between each; in centre, thunderbolt. B – A on either side of crested Macedonian helmet, Δ below.

Alexander III the Great 334BC Shield Crested Helmet Ancient Greek Coin i36441

Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia 336-323 B.C. Bronze 17mm (4.45 grams) Pella or Amphipolis: 334 B.C. LIFETIME ISSUE! Reference: SNGCop 1120; Liampi M7 Macedonian shield; around, five double crescents with five pellets between each; in centre, thunderbolt. B – A on either side of Crested Macedonian helmet.

ALEXANDER III the GREAT 336BC Hercules Eagle Authentic Ancient Greek Coin i40536

Greek Coin of Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia 336-323 B.C. Bronze 16mm (3.49 grams) Struck under Alexander the Great 336-323 B.C. Reference: Sear 6743 Alexander III the Great as young Hercules right, clad in lion-skin. ΑΛΕΞΑΝ-ΔΡΟΥ, Eagle standing right on thunderbolt, looking back; leaf in upper field to left.

Alexander III The Great 336BC Ancient Greek Coin APOLLO Healer HORSE i32123

Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia 336-323 B.C. Bronze 15mm (3.15 grams) Amphipolis mint: 336-323 B.C. Reference: Price 338; Sear 6744 cf.; Forrer/Weber 2150 cf. Head of Apollo right, hair bound with tainia. Horse prancing right; ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΥ above, torch below.

Alexander the Great under Ptolemy I Soter 305BC Ancient Greek Coin Eagle i36669

Greek King Ptolemy I, Soter – 305-283 B.C. of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt – Bronze 25mm (9.44 grams) Struck in Alexandria in Egypt 305-283 B.C. Reference: Sear 7765; B.M.C. 6.21,66 Head of Alexander the Great right wearing an elephant scalp, symbol of his conquest of India. ΠTOΛEMAIOY BAΣIΛEΩΣ, eagle standing left on thunderbolt.

Alexander the Great Bucephalus Macedonia Koinon Ancient Greek Roman Coin i42066

Alexander III the Great: Macedonian Greek King: 336-323 B.C. Roman Era, Olympic-Style Games Issue Bronze 26mm (13.73 grams) from the Koinon of Macedonia in Thrace under Roman Control Struck circa 222-235 A.D. under the reign of Roman Emperor Severus Alexander AΛЄΞANΔPOV, Head of Alexander the Great right with loose, flowing hair. KOINON MAKЄΔONΩN NEΩ, Alexander the Great on his legendary horse, Bucephalus, galloping right with cape flowing behind him.* Numismatic Note: Leaders like Julius Caesar and the Romans and the Greeks alike had immense respect for the great accomplishments of Alexander the Great. Macedonia, being the kingdom of Alexander the Great’s birth, this coin featuring his likeness heralds the Neocorate status of the area, along with the Olympic-style games that accompanied it. Highly-desirable type.

ALEXANDER III the GREAT Olympic type Games Koinon Macedonia Ancient Coin i27404

Alexander III, the Great: Macedonian Greek King: 336-323 B.C. Roman Era, Olympic-Style Games Issue Bronze 27mm (13.00 grams) from the Koinon of Macedonia in Thrace under Roman Control Struck circa 222-235 A.D. under the reign of Roman Emperor Severus Alexander AΛЄΞANΔPOV, Head of Alexander the Great right as Hercules, wearing lion-skin headdress. KOINON MAKЄΔONΩN NЄΩKO B, Agonistic prize table with two urns atop, each containing a palm branch which was a symbol for victory; amphora (vase) below table; B above table.* Numismatic Note: Leaders like Julius Caesar and the Romans and the Greeks alike had immense respect for the great accomplishments of Alexander the Great. Macedonia, being the kingdom of Alexander the Great’s birth, this coin featuring his likeness heralds the Neocorate status of the area, along with the Olympic-style games that accompanied it. Highly-coveted type.

ALEXANDER the GREAT Roman Macedonia Koinon Greek Area Coin Temples i40532

Alexander III, the Great: Macedonian Greek King: 336-323 B.C. Roman Era, Olympic-Style Games Issue Bronze 25mm (11.31 grams) from the Koinon of Macedonia in Thrace under Roman Control Struck circa 222-235 A.D. under the reign of Roman Emperor Severus Alexander AΛЄΞANΔPOV, Head of Alexander the Great right with loose, flowing hair. B KOINON MAKЄΔONΩN NEΩ, Two temples.* Numismatic Note: Leaders like Julius Caesar and the Romans and the Greeks alike had immense respect for the great accomplishments of Alexander the Great. Macedonia, being the kingdom of Alexander the Great’s birth, this coin featuring his likeness heralds the Neocorate status of the area, along with the Olympic-style games that accompanied it. Highly-coveted type.

Alexander III the Great Olympic Style Games KOINON Ancient Roman Coin i30609

Alexander III, the Great: Macedonian Greek King: 336-323 B.C. Roman Era, Olympic-Style Games Issue Bronze 25mm (8.61 grams) from the Koinon of Macedonia in Thrace under Roman Control Struck circa 222-235 A.D. under the reign of Roman Emperor Severus Alexander AΛЄΞANΔPOV, Head of Alexander the Great right with loose, flowing hair. KOINON MAKЄΔONΩN B NEΩ, Athena seated left, wearing crested Corinthian style helmet, leaning on shield and holding patera.

ALEXANDER III the GREAT Greek Coin Roman Times KOINON Macedon Coin i28366

Alexander III, the Great: Macedonian Greek King: 336-323 B.C. Roman Era, Olympic-Style Games Issue Bronze 25mm (13.24 grams) from the Koinon of Macedonia in Thrace under Roman Control Struck circa 222-235 A.D. under the reign of Roman Emperor Severus Alexander AΛЄΞANΔPOV, Head of Alexander the Great right with loose, flowing hair. KOINON MAKЄΔONΩN NEΩ, Alexander the Great on his legendary horse, Bucephalus, galloping right, holding spear and cape flowing behind him, star below.

Alexander III the Great Bucephalus Ancient Greek MACEDONIA KOINON Coin i30608

Alexander III, the Great: Macedonian Greek King: 336-323 B.C. Roman Era, Olympic-Style Games Issue Bronze 25mm (12.19 grams) from the Koinon of Macedonia in Thrace under Roman Control Struck circa 222-235 A.D. under the reign of Roman Emperor Severus Alexander AΛЄΞANΔPOV, Head of Alexander the Great right with loose, flowing hair. KOINON MAKЄΔONΩN NEΩ, Alexander the Great on his legendary horse, Bucephalus, galloping right with cape flowing behind him and holding spear.

COMMODUS as HERCULES Megalomania 192AD Ancient Silver Roman Coin Club i43640

Commodus – Roman Emperor: 177-192 A.D. Silver Denarius 17mm (2.50 grams) Rome mint: 192 A.D. Reference: RIC 251; RSC 190; sear5 #5644 L AEL AVREL COMM AVG P FEL, head of Commodus right as Hercules wearing lionskin headdress. HER-CVL RO-MAN AV-GV either side of club of Hercules, all in wreath.* Numismatic Note: This very scarce issue comes from the very end of Commodus’ reign where his megalomania got him to image that he was the re-incarnation of Hercules. Desirable type.

Download this article by right-clicking here and selecting save as

Find It Here: Alexander the Great Ancient Greek Coin Types VIDEO An interesting video about world coins. An expert numismatist created this to educate people.

from WordPress https://ialanjohnson.wordpress.com/2017/01/07/alexander-the-great-ancient-greek-coin-types-video-7/

0 notes

Note

What’s the most underrated pre-Alexander king of Macedon?

Easy. Perdikkas II.

He kept Macedonia independent throughout the long-ass Peloponnesian War. He changed sides 11 times to do so, and Thucydides kinda hated him. So be careful about what Thucydides says about him in his history. It's NOT unbiased. Thucydides wound up exiled due to losing Amphipolis for Athens, which he blamed (partly) on Perdikkas, although it was Brasidas (of Sparta) who orchestrated that.

But Perdikkas managed NOT to be obliterated by either the Athenian or Spartan superpowers--nor the powerhouses of Lynkestis or Elimeia either. Remember, at that point, they were independent Upper Macedonian kingdoms. Apparently, the Elimeian cavalry was even superior to the Macedonian for a while.

Alexander I (Perdikkas's father) was more colorful, and overall probably did the most (before Philip II) to push Macedon forward. And Archelaos (Perdikkas's son) might have topped Alex I, if he hadn't got himself murdered in 399.

BUT ... the most underestimated/underrated king?

That's my man, Perdikkas Alexandrou!

If you can read German, here you go. Best biography on him.

If you can't read German, but can read English, an older but still solid work on Macedonia generally:

#ancient Macedonia#Argead Macedonia#Perdikkas II#Alexander I of Macedon#Archelaos of Macedon#Perdikkas II of Macedon#Alexander the Great#Philip II of Macedon#Thucydides#Sabine Mueller#Eugene N. Borza#asks

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Dr. Reames, hello! It's great to be able to ask you things here, and thank you very much for taking the time to answer them. I was reading Ian Worthington's By the Spear, which inspires this ask.

Alexander the Great is one of those historical figures who have cemented themselves in general culture. Almost everyone knows who he was. My question, however, is about his father, king Philip II. I understand that historiography has privileged Alexander for a long time. But it seems like another current is re-evaluating the reign of Philip II in comparison to his son's, to reach the conclusion that Philip II was in fact the greatest ruler among them.

The argument goes (or implies, or presuposes) that it was Philip II's military prowess and accomplishments that built the Kingdom of Macedonia to a position where the conquest of the Persian Empire was made possible. If not for Philip II's work on the hegemony of Greece, and creating a strong, centralized Macedonian State, Alexander wouldn't have had the necessary conditions for the invasion of Asia.

And the argument goes on to say that while Philip II left a stronger than ever Macedonia, Alexander's reign brought just as much chaos as it brought glory: the Argead Dynasty would soon be extinct, and the realm divided between the diadochi.

First, would you say Philip II's history was overshadowed by Alexander's, and did that affect the historiography of his reign? Second, do you think this view of Philip II's reign (if it new new at all) is warranted, and Alexander's conquests depended on his father's previous success?

“The Greatest of the Kings of Europe”: Philip of Macedon

I open with that assessment from Diodoros (16.95.1). I should note that he named Philip that because Alexander, of course, called himself “King of Asia.”

The debate as to whether father or son was greater isn’t new. It raged in antiquity, too. As part of the philhellenic project of the Second Sophistic, Plutarch styled Alexander as a great conqueror and bringer of (Greek) civilization, due to his superior (Greek) culture and paideia. Philip (and later Darius) function as Alexander’s barbarian foils. Plutarch resurrects standard 4th-century rhetoric that posited Philip’s success as due to luck, not skill, strategy, or virtue. Arrian, who also wrote during the Second Sophistic but is not counted specifically among those rhetoricians, is not so blunt-knuckled about it, but he certainly highlights Alexander’s Greek virtues.

In contrast, Lucian—who, interestingly, is also a member of the Second Sophistic—preferences Philip, which he makes abundantly clear in Dialogues of the Dead: Philip vs. Alexander (12), then Demosthenes vs. Alexander (13). In both, he mocks Alexander’s claim of divinity, even though his dead-Alexander admits it was all a political ruse. Curtius Rufus also has issues with Alexander, and Justin didn’t like either Alexander or his father. For his detractors, Alexander’s success is also attributed to luck (Tychē/Fortuna), not skill or virtue—a theme that resurrects itself in a number of modern assessments.

I think the tendency to pit father and son against each other in modern scholarship merely reflects the ancient tendency, as well as, perhaps, the human desire for zero-sum competition.

Instead, we should look at how later Macedonian monarchs built on the successes of previous kings, or sometimes failed to live up to them. This is the approach I take when teaching either my undergrad ATG and the Macedonian Origin class, or my Argead grad seminar. Was there never any interfamilial competition? Well, looking at how Argeads tended to murder each other, of course there was. But that was between living relatives. If we consider Alexander’s own career, he seemed to be in competition with Herakles or Dionysos, as much as with Philip. That suggests “competition” was (like copycatting) a form of flattery.

So yes, Alexander wouldn’t have been half as great if his father hadn’t handed him a trained and seasoned army with unique and highly effective tactics—plus a (mostly) unified Greece in his rear. But Philip wouldn’t have had space to experiment with those new tactics had his brother Perdikkas III not made him archon of a Macedonian canton. Nor would he have had a place to start updating the army if both Archelaos and earlier, Alexandros I, had not begun to implement Greek hoplite divisions, the use of cavalry, as well as improved military infrastructure such as new roads, forts, etc. Not to mention Alexandros I used the Persian invasion to expand Macedon’s borders and absorb what would come to constitute “Lower Macedonia.”

Even Amyntas, Philip and Perdikkas’ father, while arguably a weak king, had managed to right the ship and stay in power for an extended period after the chaos following the murder of Archelaos. He (and Eurydike) raised three boys who didn’t try to murder each other when their father died (although Philip, at least, had to eliminate half-brothers).

Each king’s successes from at least Alexandros I forward (c. 497?-450? BCE)* led to the improvement of the Macedonian kingdom, with the exception of turmoil between Archelaos and Amyntas III.

If nobody (except perhaps Alexandros I) could be placed on a par with either Philip II or Alexander III, those two wouldn’t have amounted to much if not for earlier Argead kings. And whatever Philip handed to Alexander, Alexander had to know how to use it—and improve on it. Many a talented father has left everything to a son who failed to secure his father’s legacy.

Did Alexander’s extraordinary success suppress his father’s memory? Yes, undoubtably. See the little infographic below to get a sense of just what Philip managed:

But again, I think we must resist arguing that Philip was really the greater of the two, as a form of reactionism.** A reminder of what Alexander managed:

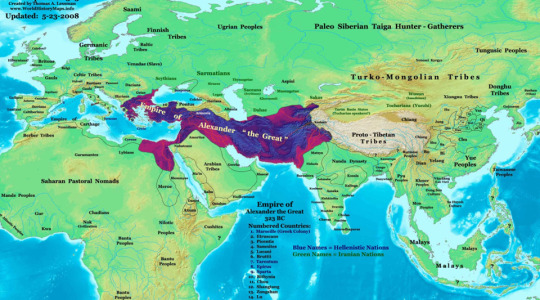

Although his conquests are ALSO overblown, so a reminder in a larger, more global context:

What I see here is a RARE case where a wildly successful father managed to raise an even more wildly successful son, at least by ancient criteria. I think it's fair to ask whether conquest should be regarded as "success," but that's a discussion for another post. In ancient terms, yes, Alexander was extraordinary.

In history, that sort of back-to-back success just doesn’t happen much. I’d like to give them both due credit, as well as recognize that both built on the work of kings before them. Neither Alexander nor Philip sprang, fully armed, from the head of Zeus. Sitting back there in the shadows are Alexandros I, Perdikkas II, and Archelaos.

And, by the way, I dare say the shade of Philip was very proud of his son.

——————-

*Whatever you may read on the Internets, we have neither a secure accession nor death date for Alexandros I. He was king by 497 BCE, before the first Greco-Persian War, and dead by 450. It’s really the best we can say.

** Richard Gabriel, Philip II of Macedonia: Greater than Alexander (Washington DC, 2010). Which is actually a rather good book in terms of showcasing Philip’s accomplishments, but feels overly strident at times in an attempt to elevate Philip over Alexander.

#Philip II of Macedon#Philip of Macedon#Alexander the Great#Alexander I of Macedon#Perdikkas II of Macedon#Archelaos of Macedon#ancient Macedonia#ancient Greece#Second Sophistic#Classics#tagamemnon#Was Philip greater than Alexander?

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

How important was it, really, that Alexander didn't have more brothers? He had Karanos, and it there's the gossip that ATG or his mother killed the boy. Philip Arridhaios apparently wasn't seen as a direct challenge and ATG kept him around. But if Philip had more healthy male offspring around Alexander's age, would that have threatened his hold on power, the partition of the empire or even the military campaigns themselves (the brothers becoming generals for example)?

Philip’s (Lack of) Sons

So, first I need to correct the bit about Karanos. He didn’t exist. Justin gave baby Europē a sex-change. No historian reports two children for Kleopatra Eurydikē, and Justin alone names a boy. We get two children when modern historians try to reconcile Justin and Diodoros/others. But Justin gets things wrong a lot. So, where Justin disagrees with other historians, I’ll go with the others (especially if it’s more than one). Justin wasn’t simply epitomizing Pompeius Trogus; he had his own agendas and themes, so he changed things when it suited him.

Therefore, “Karanos” = Europē,* born just a few days (maybe a week or two) before Philip’s murder.

The wives and children of Philip are reported in a fragment from Satyrus preserved in Athenaeus (13.557b-c). Of his (living) children, we have four girls (Kynannē, Kleopatra, Thessalonikē, and Europē), and only two boys (Arrhidaios and Alexander).

I specify living because ancient accounts don’t usually list children who died young unless it somehow impacted events. So, the murder of Europē, which led to the suicide of Kleopatra Eurydikē, means Europē got a mention whereas if she’d died of some childhood disease, we’d probably not hear about her.

Ergo, it’s possible Philip did sire other children who simply didn’t survive long enough to make it into the histories—especially if they’d been born (and died) in his earlier years. In Dancing with the Lion, I invented a son (Menelaos) by the shadowy Phila of Elimeia, who died young, specifically to illustrate that point.

The two-to-four ratio of boys to girls suggests Philip fathered girls more than boys. Would more boys have endangered Alexander’s place? Certainly, if they were around his age. But not if they were notably younger—another point I make in Dancing with the Lion: why Alexander is less upset by Philip’s seventh marriage than his mother. The chance that Kleopatra Eurydike might bear a male child threatened Olympias’s position far more than Alexander’s. Even some of my colleagues seem to forget that. While yes, sons and mothers did form a political unit at polygamous courts, that doesn’t mean that threats to the mother’s status necessarily entailed threats to a son’s. Philip’s marriage to Kleopatra Eurydikē was just such a case. Any son she produced would’ve been so far behind Alexander in achievements (and thus, a shot at the throne), that the marriage was no threat—which is why he attended the wedding. That makes events at the wedding very curious indeed! And convinces me that we don’t even begin to have the whole story there.

I made up some things in Rise (no spoilers), precisely because we don’t know and I had to come up with something that didn’t make Alexander into a reactionary rube. Too often people point to him as a “hotheaded youth” who made a mountain out of a molehill at his mother’s instigation. Folks, he was eighteen or nineteen. Hotheaded (always), but not some little kid to jump at shadows and Mommy’s tales. Something truly threatening generated that level of reaction from him (and beyond what Diodoros relates at the wedding). It wasn’t fear of being replaced by an as-yet-not-even-conceived infant brother--unless Philip had other reasons to replace him, and there weren’t any … on the face of it.

Anyway, I want to end by pointing to the Big Pink Elephant in the room that way too many people seem to forget….

AMYNTAS PERDIKKA was Alexander’s chief rival, not Arrhidaios or a fictional infant brother. Amyntas was older than Alexander, the only son of Philip’s older brother Perdikkas (III), who’d been king before Philip. Amyntas didn’t become king when his father died in battle precisely because he was only about a year old, while Philip was c. 23/24, and the kingdom was in crisis. Being a baby was also why Philip didn’t kill him. He needed an heir until he could father his own.**

So despite being the eldest Argead after Philip and the legitimate son of a former king, Amyntas spent his life as “the spare.” Imagine the resentment that would have generated. It’s not an accident that Alexander had him killed inside six months of taking the throne. And it’s probably in that time frame that Amyntas would’ve staged a bid for the throne himself. After all, not only was he an Argead, with military experience, he was married to Philip’s eldest child, who was already pregnant, showing he was fertile. He had a really good claim.

Such a clearing out of competing Argeads was standard for any new king’s first year or so. It’s what whittled down available Argead males from the five sons (and progeny) of Alexandros I to just three at Philip’s death, a hundred years later: Amyntas, Alexander, and Arrhidaios. Alexander wasn’t unique in house-cleaning. Philip had killed his three half-brothers upon taking the throne, keeping only Amyntas, his nephew. This was so typical it’s of note that Alexandros II not only didn’t get rid of Perdikkas (III) or Philip (II), but kept around his half-brothers too. It was the exception, not the rule (perhaps because all of them were still too young to be a threat?).

So basically, given Argead patterns, the survival of male siblings/cousins depended on a couple things:

The age of the sibling(s)/cousins. Siblings and half-siblings who were notably younger were likely to be spared if they didn’t appear to offer an immediate threat. After all, the new king needed an heir until he could father his own.

The apparent competence of the sibling(s)/cousins. Arrhidaios is our best evidence for this: Alexander took him with him to Asia to keep an eye on him—prevent his use as a stooge in a coup—but he otherwise kept him alive.

The king’s personal relationship with the sibling(s)/cousins. This is obviously very hard to determine, as our sources may not tell us, or not tell us honestly, but even if it’s hard, that doesn’t mean we should neglect it as a possible motivating factor. It may, in fact, explain why Alexander II (Philip’s older brother) didn’t kill his siblings. He may have loved them (and them, him). While we can’t say from the evidence, we also shouldn’t dismiss that as a possible motivating factor.

Here's an earlier posts about Amyntas, btw.

AMYNTAS PERDIKKA

* The names themselves are a give-away. “Europē,” like “Thessalonikē” was bestowed in celebration of Philip’s military victories. By contrast, “Karanos” (which means generic “chief”) isn’t a royal Macedonian name at all. Bill Greenwalt talks about the name’s significance in one of his articles, but I can’t now recall which.

** There is some question as to whether Amyntas was ever king, however briefly, due to a reference to an “Amyntas IV.” But many of us believe that was part of a challenge to Alexander later, not proof that Amyntas was king briefly, and Philip his regent.

#asks#Philip II of Macedon#Philip of Macedon#Alexander the Great#Arrhidaios#Perdikkas III of Macedon#Alexander II of Macedon#Amyntas Perdikka#ancient macedonia#Argead Macedonia#Inheritance in Argead Macedonia#Karanos#Justin lies

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can I please ask you about the rise of Antipater and what justifies Philip's & Alexander's trust on him? His backstory seems very obscure for the immense power and senior position he achieved within Macedon & the royal house. Can I also question why he never tried to marry into the royal family all this time even though his son shamelessly vied for the throne?

Antipatros (Antipater), Son of Iolaos

Antipatros was regent across four reigns (Perdikkas III, Philip II, Alexander III, and Philip III Arrhidaios/Alexander V), and possibly five (Alexander II). That’s almost unheard of. So yes, his influence was massive.

Aside from being a statesman, he also wrote a history about the reign of Perdikkas III (Philip’s older brother), and two books of letters, some of which were to Aristotle, his close friend. He acted as executor for Aristotle’s will after the latter’s death in 323 (yes, same year as Alexander). He seems to have had an intellectual-philosophic bent and was almost twenty years older than Philip. There’s a funny story in Athenaeus (I believe), wherein Philip and Parmenion were playing a game of droughts. Yet when Antipatros entered the room, Philip shoved the gameboard under his chair—like a naughty boy. It seems Philip’s older brother Perdikkas had a more philosophical bent himself, which may have paired well with Antipatros—perhaps why Antipatros wrote a history about him (not Philip). If Philip certainly seems to have trusted Antipatros, he doesn’t seem to have been as close to him as to Parmenion.

If Waldemar Heckel is correct, Antipatros and Antigonos Monophthalmos were allies, and Parmenion was his/their adversary. As the allyship with Antigonos depends on ties in the Successor Wars, it’s unclear how far back it went however. Alexander’s death scrambled older partnerships. Eumenes was supposedly a friend of Krateros, but they fought on opposite sides, and it was Eumenes’s tricky tactics that got Krateros killed. That said, I can see Parmenion and Antipatros at political odds, being the two most prominent men at Philip’s court. And, of course, Antipatros famously clashed with Olympias, and with Eumenes (Philip’s, then Alexander’s secretary).

Antipatros had at least ten kids with (probably) more than one wife. Seven of those were boys, only three girls. Yet as I’ve frequently pointed out, girls are rarely mentioned unless they played a role in history, and all three we know of did: Phila, Nikaia, and (of course) Berenike of Egypt, one of Ptolemy’s wives. I’m betting on more girls we just don’t hear about. The unnamed wife of Alexander of Lynkestis might have been Nikaia or Berenike, but she could easily have been someone else entirely.

If Kassandros eventually became king, it doesn’t seem Antipatros was too fond of him. Given that Kassandros was younger than Alexander, but Antipatros notably older than Philip, we may wonder if most of his older kids were female. His father’s name was Iolaos, but Kassandros was supposedly his eldest son … which is odd, as in most cases, a man named his eldest son after his own father. If not hard-and-fast, it was extremely common. That Antipatros had a much younger son named Iolaos, this could suggest there was an older boy who died, either in war or disease—so Antipatros then named a new son Iolaos, leaving Kassandros as (now) eldest. Several of the daughters also seem to have been older than him.

Anyway, let’s go back to Antipatros’s own father, Iolaos. Given the naming patterns, I want to point out that an Iolaos was regent for Perdikkas II, back during the Peloponnesian War. That’s quite possibly Antipatros father, as Antipatros was born c. 400. (We happen to know his death year from the Marmor Parium: 319 BCE, at 81-ish. Image of the inscription below.)

We’ve good reason to suppose Antipatros was regent for Perdikkas III before Philip, so we may be looking at a family “dynasty,” of top advisors for the king. I’m skeptical that Alexander was ever truly worried about Antipatros’s loyalties, but if he was, that might be why: his family had been throne-adjacent so long, he thought it time he sat in it, especially if Alexander was off Great-Kinging it in Persia. Certainly, that family prestige seemed to drive Kassandros.

As for Antipatros not trying to marry into the family…we don’t know that he didn’t. I suspect one BIG reason Alexander didn’t marry before leaving Macedon is that both Antipatros and Parmenion had convenient daughters of an age to offer him a bride, and he was disinclined to be that much under either’s thumb.

Antipatros was a very capable general, if not quite on Krateros’s level—one reason he courted Krateros after Alexander’s death, offering him Phila, Balakros’s widow. (Balakros had been a satrap in Cilicia.) And of course, after Krateros died on the battlefield, Phila went on to marry Demetrious Poliorketes, so she became the “mother” of the Antigonid Dynasty.

Anyway, fun fact, Antipatros—despite his very “traditional” mindset—considered Phila exceptional and sought her advice in politics, as if a son. I suspect he’d have handed over the regency to her in a heartbeat, if that had been an option. Instead, he was stuck with Polyperchon … just the-hell-not Kassandros!

A quite interesting historical novel could be written from Antipatros’s point of view, covering the reign of four Macedonian kings, although from a purely European (not Asian) point-of-view. That, in itself, would make a fantastic way to differentiate such a novel from “all the others” (including mine). Not unlike The Shadow King by Harry Sidebottom about Alexander Lynkestis. I’ve not yet read that one, but I bought it and will at some point. I like new takes.

#asks#Antipatros#Antipater#Alexander the Great#Philip II of Macedon#Philip of Macedon#Perdikkas III of Macedon#Antigonos Monophthalmos#Parmenion#officers of Philip of Macedon#ancient Macedonia#Hellenistic Era#Kassandros#Classics#regents of Macedon

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello professor Reames! I just read your earlier answer about Antipatros, yet I still have to ask: didn't Alexander foresee how dangerous letting so much power consolidate in the hands of such a man could be? In the Macedon proper, nonetheless! Do you think, if Alexander had lived enough to return to Greece or at least after his conquests were solidified, that he would have removed Antipatros from his position as regent?

Why Antipatros Couldn't Become King

Antipatros couldn’t become king—not while an Argead lived. So why remove him? Also, it could have been dangerous. See, Antipatros had held the role of regent at least back to Perdikkas III, and his father/grandfather Iolaos, held it under Perdikkas II. That suggests a sort of hereditary position. To simply “remove” him from it would require a damn good reason.

Just like, when ATG came to the throne, he couldn’t just “fire” the Bodyguards (Somatophylakes) who his father had appointed. He had to wait until either they died, or they were reappointed (by him) to a more prestigious position such as a satrapy (as happened with Balakros).