#Alexander of Epiros

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Is it possible that, after the death of Alexander of Epirus, Kleopatra at some point considered the idea of joining her brother in Asia?

Highly unlikely, because she was acting as regent for her son, Neoptolemos. Eventually, her mother returned to Epiros, and she to Macedonia.

It's not outside the realm of possibility that, once Alexander was back in the west (Babylon), she might have gone to visit. But only if she could have taken her children with her, to protect/keep an eye on them, and felt confident she wouldn't be endangering their inheritance. It might have been more likely, though, if he'd survived to come to the coast (perhaps before his Arabian campaign). A trip inland as far as Babylon was quite a journey. But taking a boat to one of the coastal cities like Halikarnassos would have been MUCH faster, a couple months, not a year-plus.

But she certainly wouldn't have stayed. Her presence in Macedonia or Epiros was far too important for political stability. Women had super-important roles for dynastic continuity.

11 notes

·

View notes

Video

OLIMPIA-ARTE-PINTURA-REINA-EPIRO-MADRE-ALEJANDRO MAGNO-MACEDONIA-MUJER-ESPOSA-FILIPO-RETRATO-PERSONAJES-POLITICA-HELENICA-PINTOR-ERNEST DESCALS por Ernest Descals Por Flickr: OLIMPIA-ARTE-PINTURA-REINA-EPIRO-MADRE-ALEJANDRO MAGNO-MACEDONIA-MUJER-ESPOSA-FILIPO-RETRATO-PERSONAJES-POLITICA-HELENICA-PINTOR-ERNEST DESCALS- La Reina OLIMPIA de Epiro, la madre de ALEJANDRO MAGNO y la esposa de FILIPO II, uno de los personajes femeninos más importantes en la políica helena, antigua sacerdotisa de los Ritos Dionisiacos siempre mantuvo un carácter ambicioso y repleto de estridencias que apoyaron a su hijo Alejandro como a un gran monarca, retrato de una mujer con mucha fuerza y opiniones personales que la hicieron temida por los cortesanos de la Corte de Macedonia. Pintura del artista pintor Ernest Descals con gouache y acuarelas sobre papel de 70 x 50 centímetros, he querido Pintar la expresión voluntariosa y con dotes para las maniobras políticas. Personajes históricos y capitales en la vida del gran Conquistador del Imperio Persa.

#OLIMPIA#REINA#QUEEN#MACEDONIA#EPIRO#MACEDONIAN#MADRE#MOTHER#KING#REY#ALEJANDRO MAGNO#ALEXANDER THE GREAT#CARACTER#POLITICA#GRECIA#HELENA#MUJER#WOMAN#WOMEN#MUJERES#SACERDOTISA#FILIPO II#ESPOSA#CHARACTER#CHARACTERS#PERSONAJE#PERSONAJES#WIFE#HISTORY#HISTORIA

0 notes

Photo

Le 101 donne più malvagie della storia aesthetic: Olimpiade d’Epiro

#donne#woman#evil woman#olimpiade#epiro#alessandro magno#alexander#maternity#plots and conspiraces#101 donne più malvagie della storia#murder

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Dr Reames!

Would you say that Macedon shared the same "political culture" with its Thracian and Illyrian neighbours, like how most Greeks shared the polis structure and the concept of citizenship?

I don't really know anything about Macedonian history before Philip II's time, but you've often brought up how the Macedonians shared some elements of elite culture (e.g. mound burials) with their Thracian neighbours, as well religious beliefs and practices.

I've only ever heard these people generically described as "a collection of tribes (that confederated into a kingdom)", which also seems to be the common description for nearby "Greek" polities like Thessaly and Epiros. So did these societies have a lot in common, structurally speaking, with Macedon? Or were they just completely different types of polities altogether?

First, in the interest of some good bibliography on the Thracians:

Z. H. Archibald, The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace. Orpheus Unmasked. Oxford UP, 1998. (Too expensive outside libraries, but highly recommended if you can get it by interlibrary loan. Part of the exorbitant cost [almost $400, but used for less] owes to images, as it’s archaeology heavy. Archibald is also an expert on trade and economy in north Greece and the Black Sea region, and has edited several collections on the topic.

Alexander Fol, Valeria Fol. Thracians. Coronet Books, 2005. Also expensive, if not as bad, and meant for the general public. Fol’s 1977 Thrace and the Thracians, with Ivan Marazov, was a classic. Fol and Marazov are fathers of modern Thracian studies.

R. F. Hodinott, The Thracians. Thames and Hudson, 1981. Somewhat dated now but has pictures and can be found used for a decent price if you search around. But, yeah…dated.

For Illyria, John Wilkes’ The Illyrians, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, is a good place to start, but there’s even less about them in book form (or articles).

—————

Now, to the question.

BOTH the Thracians and Illyrians were made up of politically independent tribes bound by language and religion who, sometimes, also united behind a strong ruler (the Odrysians in Thrace for several generations, and Bardylis briefly in Illyria). One can probably make parallels to Germanic tribes, but it’s easier for me to point to American indigenous nations. The Odrysians might be compared to the Iroquois federation. The Illyrians to the Great Lakes people, united for a while behind Tecumseh, but not entirely, and disunified again after. These aren’t perfect, but you get the idea. For that matter, the Greeks themselves weren’t a nation, but a group of poleis bonded by language, culture, and religion. They fought as often as they cooperated. The Persian invasion forced cooperation, which then dissolved into the Peloponnesian War.

Beyond linguistic and religious parallels, sometimes we also have GEOGRAPHIC ones. So, let me divide the north into lowlands and highlands. It’s much more visible on the ground than from a map, but Epiros, Upper Macedonia, and Illyria are all more alike, landscape-wise, than Lower Macedonia and the Thracian valleys. South of all that, and different yet again, lay Thessaly, like a bridge between Southern Greece and these northern regions.

If language (and religion) are markers of shared culture, culture can also be shaped by ethnically distinct neighbors. Thracians and Macedonians weren’t ethnically related, yet certainly shared cultural features. Without falling into colonialist geographical/environmental determinism, geography does affect how early cultures develop because of what resources are available, difficulties of travel, weather, lay of the land itself, etc.

For instance, the Pindus Range, while not especially high, is rocky and made a formidable barrier to easy east-west travel. Until recently, sailing was always more efficient in Greece than travel by land (especially over mountain ranges).* Ergo, city-states/towns on the western coast tended to be western-facing for trade, and city-states/towns on the eastern side were, predictably, eastern-facing. This is why both Epiros and Ainai (Elimeia) did more trade with Corinth than Athens, and one reason Alexandros of Epiros went west to Italy while Alexander of Macedon looked east to Persia. It’s also why Corinth, Sparta, etc., in the Peloponnese colonized Sicily and S. Italy, while Athens, Euboia, etc., colonized the Asia Minor and Black Sea coasts. (It’s not an absolute, but one certainly sees trends.)

So, looking at their land, we can see why Macedonians and Thracians were both horse people with their wide valleys. They also practiced agriculture, had rich forests for logging, and significant metal (and mineral) deposits—including silver and gold—that made mining a source of wealth. They shared some burial customs but maintained acute differences. Both had lower status for women compared to Illyria/Epiros/Paionia. Yet that’s true only of some Thracian tribes, such as the Odrysians. Others had stronger roles for women. Thracians and Macedonians shared a few deities (The Rider/Zis, Dionysos/Zagreus, Bendis/Artemis/Earth Mother), although Macedonian religion maintained a Greek cast. We also shouldn’t underestimate the impact of Greek colonies along the Black Sea coast on inland Thrace, especially the Odrysians. Many an Athenian or Milesian (et al.) explorer/merchant/colonist married into the local Thracian elite.

Let’s look at burial customs, how they’re alike and different, for a concrete example of this shared regional culture.

First, while both Thracians and Macedonians had shrines, neither had temples on the Greek model until late, and then largely in Macedonia. Their money went into the ground with burials.

Temples represent a shit-ton of city/community money plowed into a building for public use/display. In southern Greece, they rise (pun intended) at the end of the Archaic Age as city-state sumptuary laws sought to eliminate personal display at funerals, weddings, etc. That never happened in Macedonia/much of the northern areas. So, temples were slow to creep up there until the Hellenistic period. Even then, gargantuan funerals and the Macedonian Tomb remained de rigueur for Macedonian elite. (The date of the arrival of the true Macedonian Tomb is debated, but I side with those who count it as a post-Alexander development.)

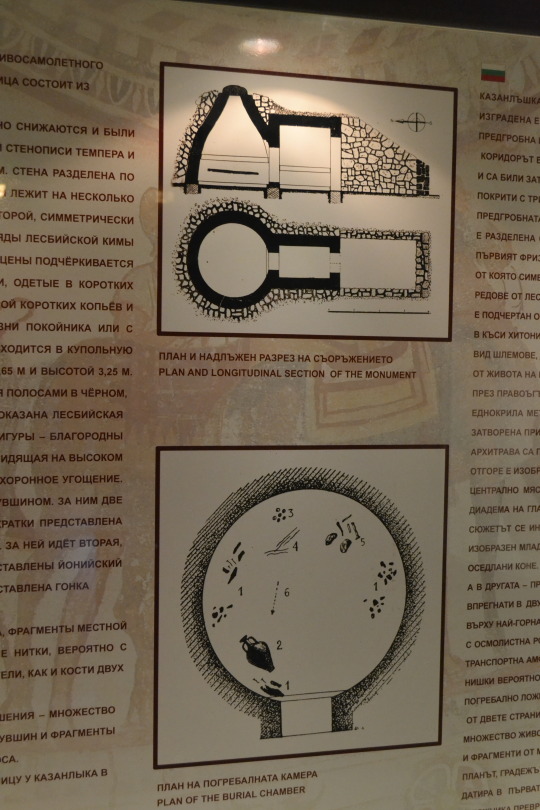

A “Macedonian Tomb” (above: Tomb of Judgement, photo mine) is a faux-shrine embedded in the ground. Elite families committed wealth to it in a huge potlatch to honor the dead. Earlier cyst tombs show the same proclivities, but without the accompanying shrine-like architecture. As early as 650 BCE at Archontiko (= ancient Pella), we find absurd amounts of wealth in burials (below: Archontiko burial goods, Pella Museum, photos mine). Same thing at Sindos, and Aigai, in roughly the same period. Also in a few places in Upper Macedonia, in the Archaic Age: Aiani, Achlada, Trebenište, etc.. This is just the tip of the iceberg. If Greece had more money for digs, I think we’d find additional sites.

Vivi Saripanidi has some great articles (conveniently in English) about these finds: “Constructing Necropoleis in the Archaic Period,” “Vases, Funerary Practices, and Political Power in the Macedonian Kingdom During the Classical Period Before the Rise of Philip II,” and “Constructing Continuities with a Heroic Past.” They’re long, but thorough. I recommend them.

What we observe here are “Princely Burials” across lingo-ethnic boundaries that reflect a larger, shared regional culture. But one big difference between elite tombs in Macedonia and Thrace is the presence of a BODY, and whether the tomb was new or repurposed.

In Thrace, at least royal tombs are repurposed shrines (above: diagram and model of repurposed shrine-tombs). Macedonian Tombs were new construction meant to look like a shrine (faux-fronts, etc.). Also, Thracian kings’ bodies weren’t buried in their "tombs." Following the Dionysic/ Orphaic cult, the bodies were cut up into seven pieces and buried in unmarked spots. Ergo, their tombs are cenotaphs (below: Kosmatka Tomb/Tomb of Seuthes III, photos mine).

What they shared was putting absurd amounts of wealth into the ground in the way of grave goods, including some common/shared items such as armor, golden crowns, jewelry for women, etc. All this in place of community-reflective temples, as seen in the South. (Below: grave goods from Seuthes’ Tomb; grave goods from Royal Tomb II at Vergina, for comparison).

So, if some things are shared, others (connected to beliefs about the afterlife) are distinct, such as the repurposed shrine vs. new construction built like a shine, and the presence or absence of a body (below: tomb ceiling décor depicting Thracian deity Zalmoxis).

Aside from graves, we also find differences between highlands and lowlands in the roles of at least elite women. The highlands were tough areas to live, where herding (and raiding) dominated, and what agriculture there was required “all hands on deck” for survival. While that isn’t necessary for women to enjoy higher status (just look at Minoan Crete, Etruria, and even Egypt), it may have contributed to it in these circumstances.

Illyrian women fought. And not just with bows on horseback as Scythian women did. If we can believe Polyaenus, Philip’s daughter Kyanne (daughter of his Illyrian wife Audata) opposed an Illyrian queen on foot with spears—and won. Philip’s mother Eurydike involved herself in politics to keep her sons alive, but perhaps also as a result of cultural assumption: her mother was royal Lynkestian but her father was (perhaps) Illyrian. Epirote Olympias came to Pella expecting a certain amount of political influence that she, apparently, wasn’t given until Philip died. Alexander later observed that his mother had wisely traded places with Kleopatra, his sister, to rule in Epiros, because the Macedonians would never accept rule by a woman (implying the Epirotes would).

I’ve noted before that the political structure in northern Greece was more of a continuum: Thessaly had an oligarchic tetrarchy of four main clans, expunged by Jason in favor of tyranny, then restored by Philip. Epiros was ruled by a council who chose the “king” from the Aiakid clan until Alexandros I, Olympias’s brother, established a real monarchy. Last, we have Macedon, a true monarchy (apparently) from the beginning, but also centered on a clan (Argeads), with agreement/support from the elite Hetairoi class of kingmakers. Upper Macedonian cantons (formerly kingdoms) had similar clan rule, especially Lynkestis, Elimeia, and Orestis. Alas, we don’t know enough to say how absolute their monarchies were before Philip II absorbed them as new Macedonian districts, demoting their basileis (kings/princes) to mere governors.

I think continued highland resistance to that absorption is too often overlooked/minimized in modern histories of Philip’s reign, excepting a few like Ed Anson’s. In Dancing with the Lion: Rise, I touch on the possibility of highland rebellion bubbling up late in Philip’s reign but can’t say more without spoilers for the novel.

In antiquity, Thessaly was always considered Greek, as was (mostly) Epiros. But Macedonia’s Greek bona-fides were not universally accepted, resulting in the tale of Alexandros I’s entry into the Olympics—almost surely a fiction with no historical basis, fed to Herodotos after the Persian Wars. The tale’s goal, however, was to establish the Greekness of the ruling family, not of the Macedonian people, who were still considered barbaroi into the late Classical period. Recent linguistic studies suggest they did, indeed, speak a form of northern Greek, but the fact they were regarded as barbaroi in the ancient world is, I think instructive, even if not necessarily accurate.

It tells us they were different enough to be counted “not Greek” by some southern Greek poleis and politicians such as Demosthenes. Much of that was certainly opportunistic. But not all. The bias suggests Macedonian culture had enough overflow from their northern neighbors to appear sufficiently alien. Few Greek writers suggested the Thessalians or Epirotes weren’t Greek, but nobody argued the Thracians, Paiones, or Illyrians were. Macedonia occupied a liminal status.

We need to stop seeing these areas with hard borders and, instead, recognize permeable boundaries with the expected cultural overflow: out and in. Contra a lot of messaging in the late 1800s and early/mid-1900s, lifted from ancient narratives (and still visible today in ultra-national Greek narratives), the ancient Greeks did not go out to “civilize” their Eastern “Oriental” (and northern barbaroi) neighbors, exporting True Culture and Philosophy. (For more on these views, see my earlier post on “Alexander suffering from Conqueror’s Disease.”)

In fact, Greeks of the Late Iron Age (LIA)/Archaic Age absorbed a great deal of culture and ideas from those very “Oriental barbarians,” such as Lydia and Assyria. In art history, the LIA/Early Archaic Era is referred to as the “Orientalizing Period,” but it’s not just art. Take Greek medicine. It’s essentially Mesopotamian medicine with their religion buffed off. Greek philosophy developed on the islands along the Asia Minor coast, where Greeks regularly interacted with Lydians, Phoenicians, and eventually Persians; and also in Sicily and Southern Italy, where they were talking to Carthaginians and native Italic peoples, including Etruscans. Egypt also had an influence.

Philosophy and other cultural advances didn’t develop in the Greek heartland. The Greek COLONIES were the happenin’ places in the LIA/Archaic Era. Here we find the all-important ebb and flow of ideas with non-Greek peoples.

Artistic styles, foodstuffs, technology, even ideas and myths…all were shared (intentionally or not) via TRADE—especially at important emporia. Among the most significant of these LIA emporia was Methone, a Greek foundation on the Macedonian coast off the Thermaic Gulf (see map below). It provided contact between Phoenician/Euboian-Greek traders and the inland peoples, including what would have been the early Macedonian kingdom. Perhaps it was those very trade contacts that helped the Argeads expand their rule in the lowlands at the expense of Bottiaians, Almopes, Paionians, et al., who they ran out in order to subsume their lands.

My main point is that the northern Greek mainland/southern Balkans were neither isolated nor culturally stunted. Not when you look at all that gold and other fine craftwork coming out of the ground in Archaic burials in the region. We’ve simply got to rethink prior notions of “primitive” peoples and cultures up there—notions based on southern Greek narratives that were both political and culturally hidebound, but that have, for too long, been taken as gospel truth.

Ancient Macedon did not “rise” with Philip II and Alexander the Great. If anything, the 40 years between the murder of Archelaos (399) and the start of Philip’s reign (359/8) represents a 2-3 generation eclipse. Alexandros I, Perdikkas II, and Archelaos were extremely capable kings. Philip represented a return to that savvy rule.

(If you can read German, let me highly recommend Sabine Müller’s, Perdikkas II and Die Argeaden; she also has one on Alexander, but those two talk about earlier periods, and especially her take on Perdikkas shows how clever he was. For those who can’t read German, the Lexicon of Argead Macedonia’s entry on Perdikkas is a boiled-down summary, by Sabine, of the main points in her book.)

Anyway…I got away a bit from Thracian-Macedonian cultural parallels, but I needed to mount my soapbox about the cultural vitality of pre-Philip Macedonia, some of which came from Greek cultural imports, but also from Thrace, Illyria, etc.

Ancient Macedonia was a crossroads. It would continue to be so into Roman imperial, Byzantine, and later periods with the arrival of subsequent populations (Gauls, Romans, Slavs, etc.) into the region.

That fruit salad with Cool Whip, or Jello and marshmallows, or chopped up veggies and mayo, that populate many a family reunion or church potluck spread? One name for it is a “Macedonian Salad”—but not because it’s from Macedonia. It’s called that because it’s made up of many [very different] things. Also, because French macedoine means cut-up vegetables, but the reference to Macedonia as a cultural mishmash is embedded in that.

---------------

* I’ve seen this personally between my first trip to Greece in 1997, and the new modern highway. Instead of winding around mountains, the A2 just blasts through them with tunnels. The A1 (from Thessaloniki to Athens) was there in ’97, and parts of the A2 east, but the new highway west through the Pindus makes a huge difference. It takes less than half the time now to drive from the area around Thessaloniki/Pella out to Ioannina (near ancient Dodona) in Epiros. Having seen the landscape, I can imagine the difficulties of such a trip in antiquity with unpaved roads (albeit perhaps at least graded). Taking carts over those hills would be daunting. See images below.

#asks#ancient Macedonia#ancient Thrace#ancient Epiros#ancient Thessaly#Argead Macedonia#pre-Philip Macedonia#Late Iron Age Greece#Archaic Age Greece#Thracian tombs#Macedonian tombs#Classics#tagamemnon#Alexander the Great#Philip II of Macedon#Philip of Macedon#women in ancient Macedonia#ancient Illyria#women in Illyria#Macedonian-Thracian similarities#religion in ancient Thrace#religion in ancient Macedonia

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any thoughts/theories on what it would've been like if Alexander ever returned to Pella? (sorry if this was already asked, tumblr's search system isn't really helpful)

What if Alexander Had Lived to Turn West?

First, I agree on Tumblr’s search system. It’s become increasingly bad. Even I can’t find posts I KNOW I made and tagged. I’m starting to compile a list of the more important (and lengthy) posts on various subjects, for my own reference. I wish Tumblr would let us pin several posts, not just one. (I’ve also sent a complaint feedback to Tumblr about this.)

Anyway, to the question: before we get to the “fun” (speculative) part, let’s address how likely it is he’d GO back. And as part of that, we need to ruminate a bit on what he might have done, if he’d returned west. So, let’s play a little “What-if?”

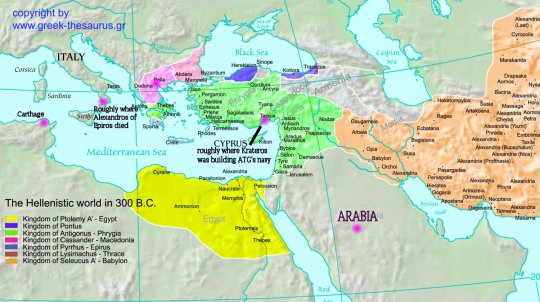

We must also keep in mind travel time. In the modern world, we can forget how long it took back then to get from Point A to Point B. Had he lived to attack Carthage (as I think he planned to do), or at least circumnavigate Arabia—both are on the southern coast of the Mediterranean. (See my tweaked map with significant places I mention below marked in purple, and recall that they tended to sail along a coast, not straight through the middle.) Macedonia is in the NW corner of the Aegean Sea. Such a side-trip would have eaten up a couple months. There might have been a sneaky reason for him to do that very thing: to come at Carthage from the north. (See discussion below.) But only if Arabia was a ruse all along. If he did mean to attack Arabia (and I think he intended that too), he'd go the southern route, then after, check on the progress of Alexandria (and visit the shrines for Hephaistion that he’d ordered built), before heading west.

If he did choose that southern route, he wouldn’t have returned to Pella before attacking Arabia or Carthage. And after…well, Italy was on the way back, so he’d probably have gone there first. And yes, I think after dealing with Carthage, he’d have used avenging the death of his uncle (Alexandros of Epiros) as an excuse to attack the Greek colonies in S. Italy. If he’d been successful against Carthage, I’m pretty sure south Italy, and possibly the north too, would have capitulated to avoid being leveled. Even Rome. At that point, Rome was in no position to fight such a titanic military powerhouse. Too many think of Rome later and backread the extent of Roman resistance into earlier periods.

Depending on the length of the campaign (e.g., how hard was any opposition), he’d have been in his mid-30s by then. Incidentally, if you’d like a speculative “What if Alexander went West,” I recommend A Choice of Destinies by Melissa Scott. (Ignore the cover.) She does have him return to Greece first, but because Thebes is in revolt (which called him back in the first place; he never reaches India). That’s the sort of event that would get him back to Greece.

There’s been speculation in both fiction and history that he didn’t want to go home because he was avoiding “his terrible mother” (as Tarn put it). I’ve written before on why Oedipal Complexes are both very modern and very wrong to assign to Alexander. I can’t now locate that post (annoyingly), but did find this one about Alexander’s relationship with Olympias in later years. So, I don’t think avoiding Olympias would have kept him from Greece/Macedonia before going west. If anything, the opportunity to see his family would have been a draw, not a dissuading point.

So, we can postulate two possible return scenarios. The first would be a side-trip on his way to Carthage as trickery to conceal his real target. After leaving Pella, he’d circumnavigate Greece to the Peloponnese, then cross the Ionian Sea to Sicily (a typical Greek trade route), and then sail around the southern edge of the island to pop across to Carthage from the north.

In this scenario, he’d be in “swing-by” mode. He’d already asked Antipatros to bring him fresh troops, so he’d have been picking them up, or acquiring more. As a recruiting campaign, it would have been short, but he’d no doubt make several religious sacrifices at Dion, Aigai, and Pella, and perhaps even visit Delphi for a prophecy about the west.

He would not bring his Asian wives with him in either scenario. First, it’s a campaign, not a family visit. But also, he intended them to stay in Babylon (or Susa). By that point, Roxane and probably also Statiera would have given birth. If both infants were male, Statiera’s would be designated heir in Asia. If only Roxana’s was male, he’d still be the “spare” by dint of his mother’s lower birth, but better than nothing in the meantime.

It’s quite possible that he intended a divided but hierarchical rule not so different from Assyrian patterns, where one heir was sent to Babylon while Daddy ruled in Nineveh and trained the other. He almost certainly meant his son by Statiera to rule in Persia/Asia, but perhaps a different son to rule in the west—one likely not even conceived yet.

I do not think he’d have married a Macedonian. He’d be looking for another political marriage, maybe to a Greek (Athenian, Syracusan…), but more likely, he’d marry a Carthaginian after any war (or as part of any peace treaty with Carthage). At that point, Carthage was the powerhouse in the Western Med. Remember, Rome had only begun her consolidation of the Italic peninsula in the wake of the Gaulic sack of the city. Alexander in Italy might have stopped that cold.

Anyway, whatever marriage he made in the west (or couple of marriages) would have been intended to produce an heir to reign there, probably subservient to any son by Statiera after Alexander’s own death, but it’s hard to know for sure. Roxana’s son (and Herakles by Barsine) would have been third and fourth fiddles. That’s WHY Roxana killed Statiera. Her status wasn’t high enough, and her son would have been destined to be regional governor in the NE territories (where his family was from): e.g., troublesome Baktria/Sogdiana. Herakles would probably have been given Asia Minor (where his Persian family was from). (More on Herakles in another post.)

But back to this scenario: if he visited on the way, it would have been a quick trip until he was off again to another campaign. (Not unlike Daddy who, in his latter years, didn’t spend much time in Pella.)

Now, let’s look at scenario #2: a visit after any victories in Arabia, Carthage, and possibly Italy. That would be a different homecoming, less pressed for time.

That said, he wouldn’t have intended to stay. After securing the eastern/middle Mediterranean, he might have driven up into Europe, to re-secure Thrace to the Danube and scout for river connections between the Black and Caspian Seas. There aren’t any, but they didn’t know that. In fact, late in his campaign, he’d already sent somebody north to do that very scouting, so this would be a follow-up.

Thrace had fallen away from Macedonian control in in his later years, thanks to the powerful Odrysian King Seuthes III. Also, Alexander hadn’t forgotten those Celts who’d been singularly unimpressed by him early in his reign. (ha) Alternatively, he might have decided to go South of Egypt to Meroë, or west of Italy to Spain. But as he was centered in Greece, my bet is north into Eastern Europe. He already had incentive from a rebellious Thrace.

What would this homecoming have been like? STUPENDOUS, of course. All the stops pulled out. Macedonia was a gift-exchange society, so bringing home a fair bit of booty would be important. We’re told he sent presents home regularly, but this would be above and beyond. It would serve two functions:

First, he’d get to claim to be the wealthiest, most successful Macedonian king EVAR, and then some. So personal fame and honor would be on the line.

Second, throwing around oodles of wealth would be a great recruiting tool. His constant warring meant he was also in constant need of new troops. In his last years, it was clear he was happy to get troops from a variety of peoples, but the Macedonian core remained (as in the Successor Wars). Of course, continually draining Macedonia of men was bad for the future population, but “sustainability” was not in any way an ancient concept, whether in resources or in manpower. Early in his career, he did show a little awareness of this, sending back men for a “conjugal visit,” but as the campaign continued, he stopped worrying about it.

Anyway, he would also probably take the opportunity to build that giant tomb for daddy that was part of his Last Plans. Hard to know how much of those plans were either exaggerated or entirely invented, but that sounds like something he’d do. He might also have taken time to improve on local religious structures (such as at Dion), and set up something (no doubt monstrously large) at both Delphi and Olympia, as panhellenic sites.

As for the reunion with his mother and sisters, as indicated, I don’t think he was staying away to avoid Mommy Dearest. So, I expect he’d have been happy, maybe even overjoyed, to see them again.

#asks#Alexander the Great#What if Alexander had lived?#Alexander versus Carthage#Alexander versus Rome#Classics#ancient history#ancient Greece#ancient Carthage#ancient alternative history#ancient Thrace#Olympias#tagamemnon

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think it’s an accident that Alexander’s life paralleled that of his hero Achilles to such an extent?

With no insult to the asker, this would be a great example of where it’d be helpful not to ask anonymously so I could query for clarity. I’m puzzled because I’m not sure what the asker has in mind, other than Hephaistion dying before Alexander as Patroklos did before Achilles?

Otherwise, they’re not parallel.

Alexander led a campaign against Persia that he inherited from his father, and was present and victorious at all (major) battles, not just one siege. He lived to become King of Asia. He married three times and left one posthumous child. That child was killed in the Successor Wars that followed.

Achilles was essentially strong-armed into the campaign by Odysseus due to a prophecy. He was not the leader nor related to the leader, and did not survive to see the final taking of Troy, nor did he become king afterwards. He fathered a child before leaving Greece, and that child survived him to become King of Epiros.

Also, of course, Alexander was real and Achilles wasn’t. This is not facetious. Non-experts sometimes don’t realize the Trojan Myth is just that…a myth. Achilles, Agamemnon, Odysseus, and Hektor never existed any more than Beowulf, King Arthur, or Rumpelstiltskin. A war between the Mycenaeans and Wilusans (Troy) may have happened, but nothing like the myth Homer tells.

Now, Alexander used Achilles for some marketing during his own campaign. But he used Herakles (and Dionysos) more. All such usages were situational. And Achilles fell behind Herakles as Alexander’s favorite hero.

Here are a couple prior posts about Alexander, Herakles, and Achilles:

Why Is Alexander Associated with Achilles and not Herakles?

Alexander’s Heros: Herakles and Achilles

Numbers from the Ancient Sources of Mentions of Various Gods/Heroes (second half)

Do You Think Alexander and Hephaistion Were Similar to Achilles and Patroklos?

I’m sorry if this harshes some squee … but it’s the historical truth.

#asks#Herakles#Achilles#Alexander the Great#Classics#ancient history#Homer#Alexander the Great as Achilles#Alexander the Great as Herakles#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Trojan War#Alexander-as-Achilles is Modern Hype

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Politically, it always made sense that Alexander married the daughters of Darius III and Artaxerxes III. It even seems like a common move. But didn't the Greeks hold themselves to a higher standard than marrying a foreigner? Even if they didn't consider the Persians outright barbarians, they were foreigners and a conquered enemy. It seems also stranger that the marriage to Roxanna happened since she seems to be far from the ideal bride

What I am trying to ask is, didn't the Greeks expect Alexander to marry a Greek woman with a proper Greek wedding? I can grasp what Alexander had in mind with the Suda weddings, but it seems very strange that this “ethnic” “Greek” element is not present

ALEXANDER & MARRIAGE

(and what was Greek “ethnicity”)

First, let me link to 2 other posts that deal with Alexander and marriage, but don’t address the ethnic element except obliquely.

Argead Inheritance and Alexander’s (lack of) heirs

Why did it take so long for Alexander to father an heir?

A couple interpretive levels present here:

Greek ethnicity and marriage pre- and post-Persian wars

Macedonian expectations for (polygamous) royal marriage

Roman attitudes, especially Late Republic (Antony and Cleopatra in particular)

I want to note that Macedonians were regarded by Greeks—and regarded themselves—as a separate people. Today in Greece, The Macedonian Question is a hot-button issue that reflects MODERN politics and nationalism. We can now say (finally have enough epigraphical evidence) that the ancient Macedonians appear to have spoken a form of northern Doric Greek, distinct from Thessalian and Epirote forms, so by modern definitions, we’d consider them Greek.

But our ancient sources often speak of the Greeks and Macedonians as if they were different, if related, peoples. Certainly, while they shared many similarities, Macedonians were distinct, and didn’t especially want to BE Greeks. I tried to reflect that ancient attitude in Dancing with the Lion.

Furthermore, the tendency to glomp all of ancient Greece together reflects Early Modern ideas of nationhood. THERE WAS NO ANCIENT NATION CALLED GREECE. That’s one of the first things I teach in my “Intro to Greek History” class. 😊 “Greece” (Hellas)* was simply a landmass. In fact, the ancient Greeks don’t appear to have referred to themselves as “Greek”—an ethnicity—until the Persian invasion.** Ethnicities were “Athenian,” “Spartan,” “Corinthian,” “Theban,” etc. Independent city-states with their own laws, coinage, magistracies, etc. In addition, they recognized larger dialect groupings: Ionic-Attic, Doric, Aeolic, then subdivisions within that. These larger dialect groupings also shared social customs and dress, as well as distinct religious cult. So, for instance, you won’t find many/any temples to Hephaistus in Doric areas, and the peplos became associated with Doric women while Ionic-Attic wore the chiton. Even the later Roman province was called Achaia and didn’t include a lot of areas they’d have considered “Greek” (Hellene).

It took being invaded by a true “Other” (Persia) before they started to define themselves as Hellenes versus Barbaroi (not-Greeks)—yet they didn’t always agree on the “edges.” It’s not until late that we find Thessaly included at the Olympic games. Epiros was sorta-Greek, as they could claim Achilles, but both Epiros and Thessaly had semi-monarchic political systems not in line with accepted Greek norms (the polis). Macedon was even further afield, being a full-on monarchy. The Macedonian royal family claimed to be Greeks ruling over a non-Greek but cousin people; the (fictional) eponymous founder, Makedon, was a nephew of the equally fictional forefather of the Greeks: Hellen. The “Greekness” of the royal family was also a fiction, invented by Alexander I—in the wake of the Greco-Persians Wars, note.

Now, again, by modern criteria, we’d probably consider the Macedonians blended but largely Greek. Yet it’s important to recognize the difference between now and then—something I get frustrated over in modern arguments. (Which can be quite strident.)

Anyway, it’s during/after the Greco-Persian Wars that barbaros came to acquire a more negative connotation. In the Archaic Age, it was a neutral term. Barbaros simply meant “non-Greek speaker” or “the bar-bar people” (“those whose language sounds like bar-bar-bar-bar to us”). It’s not complimentary, but it’s also not as negative as it came to imply later.

Furthermore, in the Archaic Age, plenty of Greek men, including Athenians, married non-Greek women—often to cement business ties, especially in Asia Minor, Thrace, and Italy. In many city-states, these children were citizens if their father was. It’s only in a few city-states that both parents had to be citizens, such as Sparta and, later, Athens. These developments are either very late Archaic or Classical, in order to restrict citizen privileges.

IOW, even in Greece proper, marrying a Greek woman wasn’t important except in a few places, specifically to limit citizenship for economic reasons. Notions of ethnic purity as we understand it weren’t a thing. Yes, even in Sparta. Full Spartans excluded other Lakonians, who spoke the exact same language and kept the exact same religious cult. In short, all Spartiátēs were Lakedaimonians (the city-state) and Lakonians (ethnicity), but not all Lakonians and Lakedaimonians were Spartiátēs. E.g. Spartiátēs were the aristocratic class. (The alt-right really needs to figure that out … except, yeah, they don’t want to as it would mess with their biases.)

When Herodotos included “blood” in his famous definition of Greekness (to speak the Greek language, worship the Greek gods, keep Greek customs, have Greek blood—and to live in a polis), “blood” meant from DADDY. This relates a bit to ancient views that a mother was just a field to be plowed for male seed. Ergo, children inherited from their fathers. (This belief was not universal, especially later, but it informed early Greek thought, and thus, inheritance laws.)

NOW … Macedonia.

Macedonian kings practiced royal polygamy for political reasons. That means Alexander wasn’t the first to marry non-Macedonians. In fact, of Philip’s 7 wives, only Kleopatra (the last) is *distinguished* as a Macedonian. Even Phila is called Elimeian (Upper Macedonian) by Statyrus. Olympias was Epirote (Greek), Philina and Nikesepolis were Thessalian (Greek), Audata was Illyrian (non-Greek), and Meda was Getai Thracian (non-Greek).

Was there objection to Philip’s marrying the latter two? Our evidence doesn’t say. In the case of Audata, he may not have had a choice; marrying her was probably part of the peace deal with Bardyllis shortly after Philip came to the throne. Later, Meda was just “wife #6” so it’s unlikely anyone cared. Hooplah over Kleopatra as a “pure” Macedonian at their wedding was meant to diss Olympias, and thus, Alexander; it wasn’t a serious objection to Macedonian kings marrying non-Macedonian/Greek women. Especially as Epirote Olympias was Greek.

Things get even MORE complicated when we look at Alexander’s weddings. How much of the supposed objection to them is Macedonian, and how much from later Greek and Roman authors’ horror over “Orientals” generally? I’d submit Curtius’s bitching about Roxana is very ROMAN. Plutarch turns it all into a love affair, but has his own reasons for that. It’s really hard to know what to make of complaints. Was his taking of Persian brides itself offensive, or just as part of his overall adoption of Persian dress and customs? I’m sure there was no collective “Macedonian attitude” so much as various camps into which this or that solder fell��from strict Traditionalists like Kleitos through to Hephaistion, who is portrayed as supporting ATG’s Persianizing.

Last, I’ll also submit another reason we find anxiety about “foreign” wives in our Alexander histories: Octavian whipping up Roman nationalist fear of Cleopatra (VII) and Antony’s marriage to her. Cleopatra became a stand-in for the Wicked Wild Oriental East and corruption of Good Roman Virtues. She’s that “Egyptian woman” (yes, even though she was technically Greco-Macedonian). Caesar may have entertained an affair with her and nursed Alexander comparisons, but between Caesar and Octavian/Antony (in fact partly because of Caesar), Alexander imitatio had fallen out of favor and would stay so for a while in the early Republic.

Curtius would have been writing (we think; dating him is tricky) under the late Julio-Claudians. So yeah, them furrun’ wimmen gotta be watched out for! Marrying Roxane was part of Alexander’s seduction by the East after the death of Darius. That Roxane was not a princess (like Statiera) made it even worse. She was a TRUE barbarian.

Add to that, polygamy wasn’t understood by either Greek or Roman writers. Plutarch tries to explain Philip’s later marriage to Kleopatra as divorcing Olympias first (as does Justin) because Romans (and Greeks) used divorce. Polygamy was, to their minds, an eastern vice. So Alexander taking (unequivocably) three wives was oriental, proof of his corruption.

Hope this helps to contextualize what we’re looking at here, and the problems involved reading the sources.

If some Macedonians objected to Alexander marrying Roxane (and they probably did), it would have been because she wasn’t high-born enough for a (first) wife, and/or she was TOO foreign. But as that marriage got them out of Baktria/Sogdiana, it looked just like things Philip had done.

Later objections involved whether Roxane’s child should be accepted as heir over Arrhidaios. That’s a different kettle of fish. It’s clear that status of the mother was important in Macedonian inheritance squabbles even before Alexander. While some Macedonians preferred the mentally unfit Arrhidaios over the child of any “captive,” others did not. They wanted a son of Alexander.

So who he married mattered rather less than who was put forward to inherit the diadema.

---------------------------

* “Greek” is from the Latin Graecae, a specific Greek tribes, just like the Romans are a specific Latin tribe. The Romans just applied it to everybody on the peninsula. The Greeks called themselves “sons of Hellen”: Hellenes. The official name of the country even today is Hellas, not Greece. Hellen isn’t to be confused with the (feminine) Helen, btw. Hellen was a son of Deukalion, Helen the wife of Menelaus, and later mistress of Paris.

** For an excellent, if rather…er, thick discussion, with lots (and I mean LOTS) of ancient evidence, see Jonathan Hall’s Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity, which addresses the question of when the ancient Greeks became “Greeks.”

#asks#Alexander the Great#Greekness#ancient Greek ethnicity#Roxane#Barsine#ancient Macedonian ethnicity#Alexander's marriages#Philip's marriages#Macedonian polygamy#Alexander imatatio#Classics#Jonathan Hall#tagamemnon

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

Conversely, if you and Alexander talked only once, what do you think he’d ask you? I guess he wouldn’t be surprised to find out there are professors studying his life and reign more than two thousand years after his death - but what do you think he would ask you about the history of, well, himself?

What Would Alexander Want to Know about Himself in History?

Interesting question. I think it would be difficult for him to know what TO ask. While it’s possible to forecast a little way into the future (science-fiction authors do it all the time), the further into the future we look, the further off-base we get. Unsurprisingly. Things come out of left field that even the most foresighted can’t anticipate.

For Alexander, I do think he realized that he died too soon, and his empire wasn’t established enough yet. Ergo, one of his first questions would likely be, “So, how fast did it all fall apart and who came out on top?”

He might even be weirdly happy to hear the answer. (Not long.) Why? It proved they couldn’t hold it together without him—which underscores his own uniqueness. I realize that’s self-centered on his part, but don’t all of us, deep down, kinda wanna know we’re irreplaceable? How much more for somebody raised in a society where kleos (glory) and timē (public recognition) were so important? An older king might have been more concerned with his “legacy” after ruling for decades. But Alexander was still young. He didn’t have much of a legacy yet to protect, other than his remarkable success. That nobody else could match it would, I think, have pleased him.

Would he have asked about his family? Probably. But I think it’d be part of the larger question of what happened next and who came out on top.

He’d LOVE that Rome named him “the Great.” In his own day, he was known as “the invincible” anikētos; “the Great” is Roman.

Yet I don’t think he’d have seen Rome coming. I expect he’d predict Carthage as the dominant Western power. Remember that, in his day, Rome wasn’t especially notable. This was still the Early Republic. Plebians were relatively new into the Senate, Rome was nowhere near in control of all the peninsula and just starting the shift from a Greek- and Etruscan-style phalanx to what would become the legion.

Reputedly, Alexander of Epiros (before his death in 331) resented Alexander of Macedon’s early successes, claiming he (Alexander of Epiros) was fighting real men in Italy while his nephew “waged a war against women” (e.g, barbarians). That’s a typical Western-centric view.* At the time, however, Persia had the most powerful army in the world. Whatever Livy claimed, had Alexander brought the Macedonian military machine west instead of east, he’d have mowed through Italy, just like in Greece, Thrace, and Illyria. It took another hundred-plus years of Roman military development to result in the wins at Magnesia or Cenoscephalae. Italy/Rome at that point was just no match for Macedon, much less Macedon under Alexander’s command.

But hoo-boy, he’d want to know about the legion, even if he wouldn’t know enough to ask directly. He might ask about future military innovations.

Also…he’d be PISSED that more people in the West today recognize the name of Julius Caesar than Alexander of Macedon. 😉 “Why didn’t Shakespeare write a play about ME???” But he’d be tickled there are more stories about him in more varied world cultures than there are about Caesar (true fact). IOW, Caesar may be more famous in the West, but Alexander is more famous in the larger world (thanks to the Alexander Romance).

Last, he might ask me about my world. If we assume he knew I was 2300+ years in his future, I think he’d naturally want to know what life is like in my time. I mean, wouldn’t we ask what life would be like 2300 years in our future? He’d probably be fascinated by the changes, although perhaps not the ones we’d anticipate.

Long ago, on a drive from Kentucky back to Nebraska, my son and I had a fun conversation about a fictional interview between Alexander and Stephen Colbert (Ian’s favorite talking-head person at the time). Stephen Colbert would ask Alexander what were the three most surprising things he’d found about the future? Would it be medical breakthroughs? Computers? The rise of democratic states? Flying through the air (and into space)? Etc.

Nope. The three things I think would surprise him the most are:

1. Near-instantaneous speed of communication 2. Easy availability of information (even if it may be wrong) 3. Changes in the importance of religion (at least in some places)

It was such an interesting conversation, I turned it into what’s now the opening Power-point in my World History I class! Ha.

————

* This supposed claim of Alexander of Epiros may not even be real. It’s recorded by Roman Cheerleader Livy, where of course the West is more powerful than the weak, decadent Oriental East.

#asks#Alexander the Great#what would Alexander the Great want to know about the future?#Classics#Alexander the Great and Rome#alternate history#Successor Wars

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do you think Alexander prefer the Aquiles archetype over Odyseus?? Was it only because Odyseus was not a renowed fighter in comparison to Aquiles whose mother was a nymph so was not a mere mortal

Why Achilles and not Odysseus has layers, first among them that Alexander believed himself to be descended from Achilles via his mother, Olympias, an Aeacid/Aiakid of the Molossian Royal House of Epiros.* Thus, it makes a natural connection. But—as I’ve argued elsewhere, both HERE and HERE and on TikTok—Herakles was the hero who Alexander most sought to emulate. Even while Macedonia reveled in its Homeric-style culture, which was less Homeric than they liked to pretend, but pretend is the salient part. Homer was ubiquitous in antiquity.

Again, the Herakles emulation also owes to a supposed family link. The Argead (or Temenid) Royal House of Macedon believed themselves descended from Herakles.** Bonus, Herakles was a son of Zeus, just as Alexander later claimed to be one from Zeus-Ammon. In the sources, we have more references to Herakles than Achilles (by far), and in terms of personal iconography, Alexander was most commonly assimilated to Herakles (at least in and close to his own time) followed by Ammon (with the horns). Never seen and Alexander-as-Achilles, or at least, not one obviously so. There’s a sculpture group that might be meant to portray Alexander as Achilles (so Andrew Stewart, if I recall, but my books are packed in boxes, so can’t check). Yet it’s a Hellenistic/Roman piece.

Other than that, we should emphasize the age thing. Alexander was young; Achilles was young. Odysseus was also a talented warrior, but not “the best of the Acheans.” At least not on a battlefield. He was cleverer, that’s for sure, but also twisty. At least early in the campaign, Alexander wanted to capitalize on youth and bravery and forthrightness—more the Achilles bailiwick. Keep in mind that Alexander molded his marketing image to the needs of the moment, so he could cast himself as various heroes. Yet Odysseus just isn’t a choice we find for him. Even when he was being sly, I don’t think he wanted to come off as sly. It wasn’t part of the image he wanted to project. One could speculate some as to why, but that attempts to get into his head and his psychology, which is always tricky to find past the layers and layers of mythos piled on top of him.

* According to myth, Achilles’s son Neoptolemos (a nasty piece of work) took Andromache as his war prize and had a son by her, one Molossos, founder of that dynasty. Even into historical periods, Neoptolemos was a common name in the Molossian family: both Olympias’s father was named that, and her grandson by Kleopatra.

* Temenos, supposed founder of the Macedonian royal house, if you believe the spin they were originally from Argos in the Peloponnesos, was the great-great-grandson of Herakles, and part of the Return of the Heraklaidai, in Greek myth, attacking Mycenae, after which he became the king of Argos. Hence their claim. They were not actually from Argos (at least not the one in the Peloponnesos), but yes, they certainly believed they were.

#asks#Achilles#Odysseus#Homer#Alexander the Great#Alexander as Achilles#Alexander the Great marketing himself#Temenid Royal House#Herakles#Molossian Royal House#classics#ancient Macedonia#Homeric Macedonia

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I hope you're well :D I have some questions related to Olympias.

Was she "de facto leader of Macedonia" as it says on wikipedia? She was also regent for her cousin Eacides, and for a few months also regent on behalf of Alexander IV?

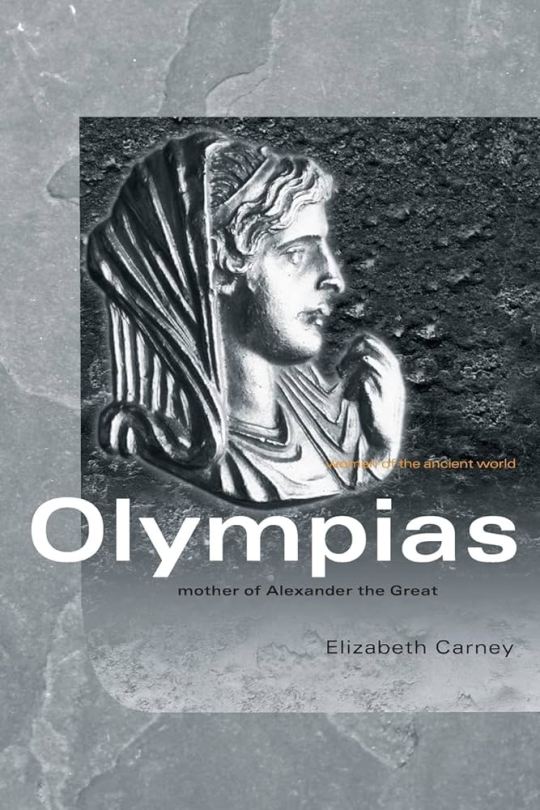

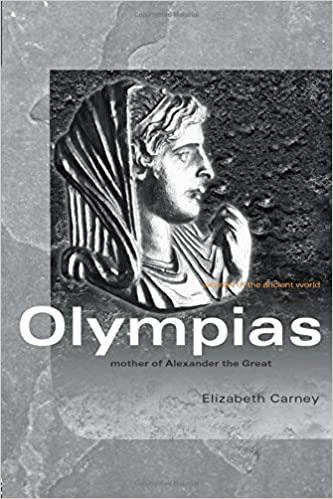

I’ve actually written a fair number of entries on Olympias. But in most, I refer to THE leading authority on her life: Elizabeth D. Carney. The number of articles (and books) this woman has written is a just a little scary!

If you are interested in Olympias, ignore everything on the internet (even me) and go and buy Beth’s book: Olympias: Mother of Alexander the Great. It’s been out a while, so you can probably find it used at a fair price, or find it in a library, especially a university library. If you can’t find it or afford to buy it, ask the library to get it for you via “interlibrary loan.”

Bonus. She’s easy to read, has a very good narrative style (imo). And yes, when she gives lectures, she talks just like she writes. Ha. (Not all authors do.) When I’m reading Beth’s stuff, I can almost always “hear” her voice in my head, amusingly.

Anyway, just start there; she will answer every question you have, and some you never would have thought of. Very rarely can I give such a singular “Go read this” suggestion as with Beth’s book on Olympias. She has several other good ones, including on Macedonian women generally, and on Eurydike, Philip II’s mother (e.g., ATG’s grandmother).

Now, as for my own posts on Olympias, here are some. I mention her quite frequently (as a search of “asks” + “Olympias” will show), but these are some of the longer ones.

Olympias’s role in Macedonia was complicated, and she was not de facto leader except in some respects, especially as it involved religion. When it came to war, and politics, that was Antipatros. That may be one reason Olympias eventually retreated to Epiros later in Alexander’s campaign, where she had more influence. But again, Beth’s book is much better about explaining all of that.

How Old Was Olympias When She Married Philip? A general post on Olympias herself and her background, that should help contextualize where she came from and what expectations she may have had, for her role as Philip’s 4th or 5th wife.

Olympias’s Relationships with Philip’s Other Wives. This discusses dynamics in a polygamous household like Macedonia.

Did Philip and Alexander of Epiros Have an Affair? While this is more about Olympias’s younger brother, it addresses, again, family dynamics in Epiros and Olympias’s role at the court (both courts).

Finally, a pair of posts on Philip’s murder, and Alexander and Olympias’s (non-)role in it. IMO.

Who Killed Philip of Macedon?

Did Alexander and Hephaistion (and Olympias) Know about the Plot?

Hope all this helps!

#Elizabeth Carney#Olympias#Olympias's role at the Macedonian Court#Collection of links to my articles on Olympias#Eurydike#Macedonian Women#Classics#Women scholars in Classics#Ancient Macedonia#Ancient Epiros

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

What was Alexander's relationship, if there was enough interaction that he would remember, with Lanike like (I don't know if that's how her name was spelled)? Would it be different or similar, or nothing at all, to what someone feels for their mother? Was Alexander the type to form lasting bonds with people? Mary Renault wrote him as affectionate and loving with people, but I honestly don't really know what to believe when I read about him. Things are usually conflicting, or as I've come to realize, made up entirely.

Thanks!

Lanike, Alexander's Affections and Royal Eugetism

There are really two questions here, so let me deal with the larger one first: Alexander’s ability to feel real affection.

I don’t think his reputation for forming intense bonds with people is false, or even much exaggerated. Nor is his tendency to fly off the handle in a rage. These are, really, two sides of one coin.*

In general, the Greeks were (and still are) more emotionally expressive than most Anglophone societies. Furthermore, in ancient Greece, to help one’s friends and hurt one’s enemies was considered model ethical behavior. Both Alexander and his father Philip were actively competitive in displays of generosity. The times they act uncharacteristically like a bull in a China shop are part of constructed narratives meant to make them conform to ideas about barbarian tyrants, particularly in the hands of later Roman authors such as Curtius, but also Plutarch of the Second Sophistic. Or with Philip, Demosthenes’ and Theopompos’ need to portray Philip as a despot who Tyche (Fortune) allowed to beat the Truly Hellenic Athens/South Greece. So, when they seem to act weirdly against their own diplomatic interests, perhaps consider the source. (Literally. Consider the source, and when he was writing.)

Macedonia, in contrast to (some of) the cities to the south such as Athens who had sumptuary laws, was a gift-exchange society. For that matter, so was earlier (Archaic and prior) Greece, as well as other city-states (not-Athens). One achieved more honor and fame for how much one gave away, not necessarily how much one had.

Generosity made the Man. It also made the Woman. An important social function of the wives of Macedonian kings, as well as of other wealthy citizens in Macedonia and elsewhere (including into the Hellenistic and later Roman eras), was to give donations to this or that city project, temple, building, etc.

Eurgetism.

By all accounts, Alexander took real joy in giving things away. Sometimes lavishly. This cemented his status as The Bestest King in the Whole Wide World. Certainly the richest. Near the end of his life, he spent ridiculous amounts of money every evening just on royal suppers.

ALL of this is about Display as Status. As well as rules of hospitality.

I explain all that to help give some cultural context to Alexander’s fabled generosity. Yes, I think it was very real. It was also absolutely culturally expected of him.

So his reputation for honoring friends and allies in lavish ways shouldn’t be unexpected. He also appears to have been affectionate and even thoughtful towards those he considered friends and allies. Ergo, I think his affection for his childhood nurse would be quite genuine.

Now to the second question, which involves the role a nurse had in an infant’s life…. In cultures that strongly emphasize the nuclear family, and for those of us who didn’t grow up wealthy enough to have “house staff,” it may feel unclear how to understand the role of a wetnurse. So let’s quickly frame that role in traditional Greek (and Macedonian) society.

Wetnurses were typically either slave women or from poor families who needed to supplement income. That Alexander had a noblewoman as a wetnurse was extraordinary. (Just as it was to have a prince [of Epiros] as a lesson-master.)

Ancient Greece had two “house-slave” categories devoted to the caretaking of children: the wet-nurse and the paidogogos (pedagogue). The former was, for wealthier families, the caretaker of children of both genders while the mother saw to the business of running an estate (or at least a larger farm). The paidogogos, however, was exclusively for male children old enough to leave the home (go to school, to the gymnasion, etc.), largely as a baby-sitter, to keep the kid out of trouble. There appears to have been genuine affection between some children and their slave caretakers. But also examples of wetnurses and paidogogoi who just didn’t give two figs. No doubt this reflected how they were, themselves, treated by their owners. (And that could devolve into a complicated discussion about slavery in antiquity, but… go and read my friend and colleague, Peter Hunt’s book, Ancient Greek and Roman Slavery.)

In Alexander’s case, these individuals weren’t slaves, which simplified (and complicated) his relationships with them. On the one hand, it removed the utter dependence/lack of autonomy any slave (however well-treated) would have experienced. But—as with the institution of the Pages, who were nobility doing slave work as body-servants to the king—it involved the “reduction” of elites to unfree occupations. That hovered between honor and humiliation. It’s an honor because he's royalty, but….

For most of us, who, again, didn’t grow up wealthy, having “house staff” is unfamiliar. Ergo, the complicated dynamics of such is equally unfamiliar. That said, I think seeing the wetnurse as another mother may not be the best analogy (except in cases where the mother might really have been distant/absent).

I’d compare it to AUNTIES. A lot of societies have aunties (both literal and honorary) who play super-important roles in children’s lives. Those aunties may even have children of their own (cousins, again literal and honorary), but that doesn’t lessen their impact on their nieces and nephews. Or how they can be loved in a way similar to, but different than a mother. (Or how they can be exasperating in a way similar to, but different than a mother!)

So, for many of us, probably the best analogy for Lanike’s role in Alexander’s life would be a beloved auntie.

* This is also why I find attempts to paint him as a psychopath/sociopath or megalomaniac (e.g., narcissistic personality disorder) unfounded. A characteristic of both is inability to empathize or have strong emotions for people outside the self (and occasionally a very few select others). If he were any of those, he’d manipulate the hell out of people, but not feel much himself. His affections and rages seem far too spontaneous for that.

#asks#Alexander the Great#wetnurses in Greek society#generosity in ancient Greek society#Lanike#Alexander the Great's affection for friends and family#Classics#ancient history#ancient Greek family ties

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Kind of related to the ask on Cleopatra, and even your one way earlier on Krateros… What do you think Alexander would’ve been like if he weren’t an Argead, and instead fated to be a Marshal for whoever else was meant for the throne? Do you think he would’ve been rebellious? Or cutthroat and ambitious like Krateros? Or more-so disciplined and loyal? I kind of see him as a combination of all three because I don’t peg Alexander for someone who can be contained, lol.

To answer this, we must keep in mind that, for the ancient Greeks, belief in divine parentage for certain family lines was very real. A given family and/or person ruled due to their descent. The heroes in Homer had divine parents/grandparents/great-grandparents. This notion continued into the Archaic period with oligarchic city-states ruled by hoi aristoi: “the best men.” (Yes, our word “aristocrat” comes from that.) Many of these wealthy families claimed divine ancestry; that’s why they were “best.”

In the south, this began to break down from the 5th century into the 4th. But not in Macedonia, Thessaly, or Epiros. In fact, even by Alexander’s day, many Greek poleis remained oligarchies, not democracies. And in democracies, “equality” was reserved for a select group: adult free male citizens. Competition (agonía) was how to prove personal excellence (aretȇ), and thereby gain fame (timȇ) and glory (kléos). All this was still regarded as the favor of the gods.

Alexander believed himself destined for great things because he was raised to believe that, as a result of his birth. Pop history sometimes presents only Olympias as encouraging his “special” status. But Philip also inculcated in Alexander a belief he was unique. He (and Olympias) got Alexander an Epirote prince as a lesson-master, then Aristotle as a personal tutor. Philip made Alexander regent at 16 and general at 18. That’s serious “fast track.” Alexander didn’t earn these promotions in the usual way; he was literally born to them.

If Alexander hadn’t been an Argead, that would have impacted his sense of his place in the world no less than it did because he was an Argead. What he might have reasonably expected his life path to take would have depended heavily on what strata of society he was born into.

Were he a commoner, in the Macedonian military system, his ambitions might have peaked at decadarch/dekadarchos (leader of a file). Higher officer positions were reserved for aristocrats through Philip’s reign. With Alexander himself, after Gaugamela, things started to change for the infantry, at least below the highest levels (but not in the cavalry, as owning a horse itself was an elite marker). Under Philip, skilled infantry might be tagged for the Pezhetairoi (who became the Hypaspists under ATG). But Alexander himself wouldn’t have qualified because those slots weren’t just for the best infantrymen, but the LARGEST ones. (In infantry combat, being large in frame was a distinct advantage.) So as a commoner, Alexander’s options would have been severely limited.

Things would have got more interesting if he’d been born into the ranks of the Hetairoi families, especially if from the Upper Macedonian cantons.

Lower cantons were Macedonian way back. If born into those, he (and his parents) would have been jockeying for a position as syntrophos (companion) of a prince. Then, he’d try to impress that prince and gain a position as close to him as possible, which could result in becoming a taxiarch/taxiarchos or ilarch/ilarchos in the infantry or cavalry. But he’d better pick the RIGHT prince, as if his wound up failing to secure the kingship, he might die, or at least fall under heavy suspicion that could permanently curtain real advancement.

That was the usual expectation for Lower Macedonian elites. Place as a Hetairos of the king and, if proven worthy in combat, relatively high military command. Yes, like Krateros. But hot-headedness could curtail advancement, as apparently happened to Meleagros, who started out well but never advanced far. The higher one rose, the more one became a potential target: witness Philotas, and later Perdikkas. In contrast, Hephaistion was Teflon (until his death). Yet Hephaistion’s status rested entirely on his importance to Alexander. And he probably wasn’t Macedonian anyway; nor was Perdikkas from Lower Macedonia, for that matter.

The northern cantons were semi-independent to fully autonomous earlier in Macedonian history. Their rulers also wore the title “basileus” (king); we just tend to translate it as “prince” to acknowledge they became subservient to Pella/Aigai. Philip incorporated them early in his reign, and I think there’s a tendency to overlook lingering resentment (and rebellion) even in Philip’s latter years. Philip’s mother was from Lynkestis, and his first wife (Phila) from Elimeia. Those marriages (his father’s and his) were political, not love matches.

Similarly, Oretis was independent, and originally more connected to Epiros. Note that Perdikkas, son of Orontes, was commanding entire battalions when he, too, was comparatively young. Like Alexander, he was “born” to it. Carol King has a very interesting chapter on him in the upcoming collection I’m editing, one that makes several excellent points about how later Successors really did a number on Perdikkas’s reputation (and not just Ptolemy).

If Alexander had been born into one of these royal families from the upper cantons, quasi-rebellious attitudes might be more likely. Much would depend on how he wanted to position himself. Harpalos, Perdikkas, Leonnatos, Ptolemy…all were from upper or at least middle cantons. They faired well. For that matter, Parmenion himself may have been from an upper canton and decided to throw in his hat with Philip.

By Philip’s day, trying to be independent of Pella was not a wise political choice, but if one came from a royal family previously independent, we can see why that might be seductive. Lower Macedonia had always been the larger/stronger kingdom. But prior to Philip, Lynkestis and Elimeia both had histories of conflict with Macedonia, and of supporting alternate claimants for the Macedonian throne. At one point in (I think?) the Peloponnesian War, Elimeia was singled out as having the best cavalry in the north. Aiani, the main capital, had long ties WEST to Corinthian trade (and Epirote ports). It was a powerful kingdom in the Archaic/early Classical era, after which, it faded.

So, these places had proud histories. If Alexander had been born in Aiani, would he have been willing to submit to Philip’s heir? Maybe not. But realistically, could he have resisted? That’s more dubious. By then, Elimeia just didn’t have the resources in men and finances.

I hope this gives some insight into how much one’s social rank influenced how one learned to think about one’s self. Also, it gives some insight into political factions in Macedonia itself. As noted, I believe we fail to recognize just how much influence Philip had in uniting Lower and Upper Macedonia. Nor how resentment may have lingered for decades. I play with this in Dancing with the Lion: Rise, as I do think it had an impact on Philip’s assassination.

(Spoiler!)

Philips discussion with his son in the Rise, and his “counter-plot” (that goes awry) may be my own invention, but it’s based in what I believe were very real lingering resentments, 20+ years into Philip’s rule.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Alexander alternate history#ancient Macedonia#ancient Macedonian politics#Upper Macedonia#Lower Macedonia#Macedonian internal politics#Philip II of Macedon#ancient history#Classics

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I have some questions following the ask you answered about Pausanias (I apologize in advance for the length of the question, they're just too many)

What was considered "too old" for a lover in ancient Macedonia? What was the normal age for the King's lovers to be?

And, like anon asked, do you think Pausanias was in love with Phillip or was it all about the status?

Was it common for kings to be in love, or better said, to have a close relationship with his lovers (outside the bedroom, I mean)? Or how did those types of relationships worked? Do we know how Phillip and Pausanias' relationship was like, before he changed him for the other Pausanias and after the party incident?

And a side question, something that was never clear for me, did Phillip also rape Pausanias at the party?

Kings, Emperors, and Their Lovers

First, general Greek ideals (note ideals, not necessarily reality) tended to paint the eromenos as ranging from pre-teen to late teens. Supposedly, the ability to grow a beard marked the end of one’s attraction as a boy (eromenos) and the transition to being the erastes (lover). There’s a brief window where one could (in theory) be the eromenos to an older lover, but erastes to a younger beloved. There’s no hard-and-fast age, as people mature at different rates. So, for instance, in the novels, Hephaistion isn’t even 16 but can grow his beard. Alexander, at almost 19, is shaving because his beard is so patchy. Again, the younger age is similar; some matured sooner into pre-teen/early teen, although on pottery, we see some eromenoi who look (disturbingly) like older children. Most are clearly younger teens. The Romans, btw, were squicked by Greek pederasty, although it was the “free born boy” part that bothered them. The sexual use of slave children was shrugged off. It was more about status than age.

Yet there is a reason it was called Greek paederasty in the ancient sources, although that’s not a term we use much now except in very specific circumstances, as it tends to bring to mind modern child sexual abuse. There were two big differences. First, the very public nature of the courting—unlike the concealed coercion of abuse victims—made it difficult to conceal inappropriate behavior. Second, the eromenos had the power in the relationship to turn down the courting altogether, or to say “yes” or “no” to sexual activity. (Note below the young man grabbing the wrist of the older man, to stop him. Although it’s been pointed out he stops the hand to his chin [a courting gesture], but not the one reaching for his dick!)

Making parallels to women dating in the middle 20th century aren’t entirely off-base. It was the boy who asked out the girl, who could turn him down. And the girl was tasked with saying “no” to male advances because “he couldn’t control his passions.” Yet there was a problem of “no” being ignored (e.g., rape), or more powerful suitors coercing compliance. We’re back to the difference between the ideal and the real.

This is why I get really BOTHERED by the whole romanticizing of Antinoös and Hadran as gay icons. Antinoös was about 12 when Hadrian picked him up and took him to Italy, and Hadrian was already emperor. You don’t tell the emperor no, especially not one known for his short temper. Maybe Antinoös was a social climber and adored his position as the Hellenizing Hadrian’s eromenos, or he at least made the best of a bad situation. But we have nothing at all to tell us his thoughts, and some really disturbing/murky gossip surrounded his death in the Nile. Guys, it’s NOT a love story, and Antinoös was a victim.

That said, and however predatory Hadrian’s behavior may have been, most erasteis were no more plotting to seduce the cute 11-year-old in the palaistra than the average young man intended to lure his date into the backseat of his 1956 Chevy and rape her. But those people existed, both in the recent past and the distant past, and we shouldn’t forget it.

Now, I use the Hadrian parallel as the same issue would apply to the Macedonian king. In Becoming, Hephaistion thinks to himself that, if Philippos were to make a move on him, he’d have to consider carefully his reaction, as one didn’t just turn down the king.

But we have very little (e.g., virtually NO) evidence for what Philip’s relations with his lovers was like. No doubt, it varied. We have a hint that coercion may have been the case with kings, or at least a sense of opportunism. Philip wasn’t the first Macedonian royal killed by an eromenos. Archelaos was too. We’re told that, while out hunting, he was speared by a Page (or former Page) who was a Thessalian “prince” (e.g., a member of one of the four leading families). The reason? The boy had been promised that Archelaos would help him/his family regain their political position in return for his sexual favors. But that didn’t happen, and so the boy felt used by Archelaos, his timē besmirched, so he killed Archelaos. This prior example is often cited when we talk about what happened to Philip, to understand what may have been going through Pausanias’s head as motivation.

We also know that Pausanias didn’t want to step down at Philip’s lover, although why isn’t at all clear. Did he love Philip, or think he did? Or was he loathe to give up the status such a position gave him? Or both? Or maybe there was some other reason we aren’t told. Pausanias appears to have been a member of the ruling family in Orestis; did he (like the Thessalian earlier) want something for his family, and was angry at being replaced because he didn’t have it (yet). Any of those is possible. We just lack any data whatsoever. We can say that, if Philip and Alexander of Epiros were lovers as Justin suggested, Philip did help Alexander to his throne. Justin implies he meant to do it all along, but that’s Justin’s love of scandal.

One of the jobs of an erastes is to shepherd his eromenos into adult male culture, such as the symposion and gymnasion. But also to further his general future, including into politics if of the higher classes. That’s part of what lies behind the Page’s resentment of Archelaos. By contrast, it looks as if Philip did perform that job, at least with regard to Alexander, and perhaps for his other eromenoi.

Philip had nothing to do with the party where Pausanias was raped. He was later targeted by Pausanias because he didn’t punish Attalos as Pausanias wanted. He only promoted Pausanias into the Pezhetairoi (the unit later called Hypaspists by Alexander). It’s called “bodyguard” (somatophylax), but shouldn’t be confused with the 7-man unit. The Pezhetairoi were the “bodyguard,” small /b/, for the king in combat. Philip then sent Attalos overseas with Parmenion. This might look like a promotion as the uncle-in-law of the king, but it smells (to me) like being kicked upstairs and got out of Pella. Nonetheless, it seems to have been that “promotion” of Attalos that set off Pausanias, who then targeted Philip as the un-just judge.

#erastes#eromenos#Greek homoeroticism#Greek male-male courting#Philip of Macedon#Pausanias of Orestis#Pausanias#Alexander of Epiros#Hadrian#Antinoos#Hadrian and Antinoos#asks

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi do you think Alexander and Alexander of Epirus knew each other well ?

I expect not very. Alexander of E. was about 15 years older than Alexander of M. And while Alexander of E. was at the Macedonian court for a few years, Alexander of E. would have been one of Philip's Pages, and likely too busy with duties and military practice. Later, he'd have been back in Epiros. It probably also depends on whether Alexander of E. liked kids. If so, he might have spent time teaching his little nephew things. If he didn't, Alexander would still have been in the women's rooms, so he might have seen him only now and then. (He probably left Macedonia when Alexander of M. was only 3-4.)

#Alexander the Great#Alexander III of Macedon#Alexander of Epiros#Alexander of Molossos#ancient Macedonia#asks#ancient Epiros

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

In Becoming, you imply that Phillip and Alexander of Epiros had an affair. Is this historically accurate? How would Olympias have felt about it, especially if she was close to her brother- would she gave been jealous or worried for him?

Philip and Alexander of Epiros (and some Epirote history)

Olympias wasn’t that much older than Alexander of Epiros, and exactly when he came to Macedon isn’t settled. Justin gives the most details (8.6), as well as the titbit that, as he was “a youth of remarkable beauty,” Philip pursued and seduced him. Justin loves the salacious details (as did his source Pompeius Trogus), so he makes it sound as if Philip preyed on the boy. Justin generally portrays Philip as a bad person, so it’s just part of his general narrative. Nonetheless, when Alexander arrived in Macedon has a lot to do with the likelihood of any affair. If his arrival was closer to 350 than earlier in 356/55 (when Alexander the Great was born), he’d have been “too old.” I suspect he was younger, because if he made it to 18-20 alive, Philip didn’t need to bring him to Macedon to protect him (see below).