#Alexander the Great as Herakles

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Do you think it’s an accident that Alexander’s life paralleled that of his hero Achilles to such an extent?

With no insult to the asker, this would be a great example of where it’d be helpful not to ask anonymously so I could query for clarity. I’m puzzled because I’m not sure what the asker has in mind, other than Hephaistion dying before Alexander as Patroklos did before Achilles?

Otherwise, they’re not parallel.

Alexander led a campaign against Persia that he inherited from his father, and was present and victorious at all (major) battles, not just one siege. He lived to become King of Asia. He married three times and left one posthumous child. That child was killed in the Successor Wars that followed.

Achilles was essentially strong-armed into the campaign by Odysseus due to a prophecy. He was not the leader nor related to the leader, and did not survive to see the final taking of Troy, nor did he become king afterwards. He fathered a child before leaving Greece, and that child survived him to become King of Epiros.

Also, of course, Alexander was real and Achilles wasn’t. This is not facetious. Non-experts sometimes don’t realize the Trojan Myth is just that…a myth. Achilles, Agamemnon, Odysseus, and Hektor never existed any more than Beowulf, King Arthur, or Rumpelstiltskin. A war between the Mycenaeans and Wilusans (Troy) may have happened, but nothing like the myth Homer tells.

Now, Alexander used Achilles for some marketing during his own campaign. But he used Herakles (and Dionysos) more. All such usages were situational. And Achilles fell behind Herakles as Alexander’s favorite hero.

Here are a couple prior posts about Alexander, Herakles, and Achilles:

Why Is Alexander Associated with Achilles and not Herakles?

Alexander’s Heros: Herakles and Achilles

Numbers from the Ancient Sources of Mentions of Various Gods/Heroes (second half)

Do You Think Alexander and Hephaistion Were Similar to Achilles and Patroklos?

I’m sorry if this harshes some squee … but it’s the historical truth.

#asks#Herakles#Achilles#Alexander the Great#Classics#ancient history#Homer#Alexander the Great as Achilles#Alexander the Great as Herakles#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Trojan War#Alexander-as-Achilles is Modern Hype

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The problem with this is that Alexander didn't want to be Achilles.

Alexander wanted to be HERAKLES.

That's still a fictional character. Although in both cases, Alexander didn't know/believe that.

Yeah, yeah, I took it all too seriously, but hey. I'm a historian.

And I'm tired of the Alexander = Achilles trope.

something about ‘don’t we all want to be achilles’ sticks with me so much, i feel like more people should see this

#Alexander didn't want to be Achilles#Alexander the Great#Achilles#Herakles#Hercules#Historians being assholes....

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've always been astounded by the absolute barbarity employed by the Argead Dynasty (the one that Alexander the Great was part of) to bullshit their way into recognition by Greece.

You know, Alexander the First, (would be) King of Macedon, saw the Olympic Games and wanted to participate. I imagine the conversation going like this

ALEXANDER: -" I want to do that too"-

HELLANODIKAI: -" Greeks only"-

ALEXANDER: -" well of course Greeks only my friends, because I am in fact Greek, my whole family comes from Argos"-

HELLANODIKAI: -" wdym your family comes from Argos, you're the literal Prince of Macedon, this is bullshit"-

ALEXANDER: -" you know what Mr. Olympia, I didn't wanna brag but you forced me to, because I'm not only Greek, but a descendant of Herakles himself"-

HELLANODIKAI: -" we'll have to look into this.

And then they fucking granted him permission to take part in the Olympic Games because they believed his bullshit.

He then proceeded to model his court after the "Court of the Athenian Kings" despite not being a court nor kings in Athens.

He was later named Philellenos after the Persian wars, but the Greeks didn't know he offered and actively gave assistance to both sides and was probably banking on getting on the good side of whoever would have won the war, to then get power and money.

Alexander also tried bullshiting the Persians into recognition by (most probably) giving away his sister in marriage to a Vassal of the Achaemenid Empire and General of Persia. He also frequently bribed Persian officials to give embellished reports about Macedon. His turnaround to Greece might have been dictated by his own failure to get recognised as a full on Vassal by the Achaemenid court (and the subsequent forced submission of Macedon).

Sometimes I stop to think that we could have had a Persian Alexander the Great, reincarnation of Verathragna, conquering all of Europe instead. If just his great-great-great-great grandfather managed to bullshit the Persians instead of the Greeks.

#ancient history#archaeology#ancient greece#ancient art#history#art#alexander the great#philip ii of macedon#alexander of macedon#ancient macedonia#ancient persia

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's take a look at Indo-Greek art and culture this week. Indo-Greek culture emerged after Alexander the Great's armies pushed to the edge of India. Even though Alexander's armies retreated, he left behind a lot of Greek culture and Greek people. The two cultures combined in all sorts of interesting ways.

Here are some coins of Agathokles the Just, a Bactrian king who ruled in the 180s BCE. We don’t know a whole lot about him, but he left behind a lot of coins that give us a sense of what must have been happening in this part of the world.

This shows Herakles wearing a lion skin on his head, with the words “ALEXANDER SON OF PHILIP;” on the back of the coin, Zeus holds an eagle, accompanied by the words “KING AGATHOKLES THE JUST.”

Pretty Greek, right?

It’s square, a shape much more common in Indian coins. And you’ll notice that it has two different scripts, one on the front and one on the back. On the one side, we see the Hindu deity Balarama-Samkarshana with the words (in Greek) “KING AGATHOKLES,” while on the back we have a Hindu god, Vāsudeva-Krishna, with Agathokles’ name written in the Brahmi script, which was widely used in South Asia.

{WHF} {Ko-Fi} {Medium}

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nite tips;

Tetradrachm of Alexander Ill 'the Great' 336-323 BC . On the obverse , Note with each city mint , Head of Herakles wearing lion's skin headdress different type of hair style.

Mint-Specific Hair Style Variations:

- Coins from #Amphipolis Curly or Short Hair.

- coins from #Sardis Integration with the Lion’s Mane.

- Coins from #Babylon or #Alexandria Longer, Flowing Locks

- Coins of #Pella hair more Smooth and wavy hair.

Each city mint across Alexander’s empire produced coins with slight variations in style and design. This includes differences in the depiction of Herakles’ hair beneath the lion’s skin, influenced by local engravers and artistic traditions.

Reasons for Variation:

• Local Engravers: Individual engravers added their artistic flair, reflecting regional styles.

• Mint Authority: Different satraps or officials controlling the mints might influence design choices.

• Cultural Influences: Hellenistic art was shaped by local traditions, especially as Alexander’s empire spanned diverse regions.

#Zeus #enthroned #eagle #ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΥ # Alexander

#Macedonian_Empire #Alexander_III

#Macedonian #Empire Alexander_coins #archaeology #history #ancient #lysimachus #alsadeekalsadouk #ancienthistory #travel #archaeological #Balkan #museum #Alexander_the_Great #heritage #greek #arthistory #antiquity #Slavic #hellenistic #tetradrachm #الصديق_الصدوق

#Alexander_iii#history#archaeology#photography#culture#greek coins#travel#roman coins#palestrina#sidon saida tyre beirut phoenician الصديق_الصدوق#الصديق_الصدوق

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prologue - Fate Zero/Stay Night x You

The beginning - Part one

Part 2

Before you came to the glorious Tohsaka family, your parents started to live in Japan for better life. Basically, you were born in Japan and had no problem to learn their language. But the tragic began with you being two years old. The Holy Grail War started and your parents are killed amid it. You can not remember that you lain in a puddle of blood and cried. Someone saved you and you stayed two years in an orphanage. Yet, you remembered a tall man, Tokiomi Tohsaka, stand in front of you with a relieved face. As if he searched you for a long time. You waited two years to be adopted and bubbly next to the stranger. Of course, you missed your parents even so you had no idea at that time what happened. And now, you gonna have a normal family again. Tokiomi told you that he knows your father from work and he felt responsible for your sake. „I am just happy you adopted me and we can be a real family!“ He just smiled at you.

Rapidly, you learned that the Tohsaka Family is famous for magic. You loved it because it is like from a fairy tale. A year later, your younger sister Rin Tohsaka is born. Actually, you have two sisters, Sakura and Rin, but after a few years your are not allowed to talk about Sakura as your sister. She was sent to the Matou family. The reasons or formalities couldn’t you comprehend as a child. Even though, you were just adopted by Tokiomi of sympathy cause of his friend, he taught you the magic ritual of his family. He talked about the gem stones and the bond this family has. You find it really interesting to listen even so you had a hard time using the power. You don’t have his blood and so he still was strict. Aoi, your adopted mother showed some sympathy and whispers to you as she putted you to bed that he is doing it because he accepted you as his own. With new motivation, you succeeded to make him proud. After this, he talked about the Holy Grail War which is gonna held in four years. You loved his stories about this war and felt already excited even he said that he doesn’t want you, Aoi and your sister to be close when the Grail War started.

„And who are you gonna call as your Servant, father?“ You orbs watch him with excitement of his answer. He laughed.

„We still have time… Who do you think I should call?“

You put up a thinking face as you recalled old heroes you heard.

„Herakles? Wasn’t he super strong?!“ You giggle as you remember the Disney movie.

„Yeah, but is just strength important?“ You shake your head as you again start to think.

„Achilles! He is strong, fast and clever!“ „Oho! From here did you hear from this hero?“

„From school… In history, we talked a bit about Greek legends.“

„Ah… this explains a lot.“

At this you begin, to read old lores from heroes. You know about Arthur, nordic heroes like Ragnar or Alexander the Great. First, you ran with any added story to your father’s office and rant about the new great star you have found. Then, he told you it just can not be any kind of hero, it had to be a special one fitted for the Tohsaka family… After this, you became more critical. You searched for any witted characterized hero. A little disappointed you walk towards Rin who was now three years. „Little Rin, you have no idea how hard it is to find the perfect servant …“ you watch her reach out towards you with her little hands smiling. „Aw, you are so cute!“ You snuggle a bit with her. Again, you found yourself curled up in a corner of the Tohsaka library. You searched for any Irish stories and if they had any ‚wit‘ you searched. Bumping into a shelve you shriek a bit when a book falls to the floor. A very old book. You took it in your arms as you carry this heavy book to the couch to flick through it.

„The Epic of… Gil-Gil-Gilgame- …“ You eyebrows twitch annoyed. Somehow, you can not speak it out. With one try you almost screamed this name.

„GIL-GA-MESH!“ You sighed. „What a weird name…“ More you thought was weird the story… You couldn’t understand it. Somehow …. It repeats so often and the text is over empurpled. You closed it annoyed and walked back to the shelves as you blink back. The book was so beautiful golden. It took seconds as you again sat in front of it and tried to understand this flowery language. Maybe, this story got you because you didn’t finished the book in a day or two. A whole year took you to finally understand his tale. You remember how you closed the book proudly and a bit sad that it was over. „Woow!“ Rin was four years as she mumbled.

„Are finally done with this boring book.“ You look up to her as you begin to smirk. „It wasn’t boring. It was epic.“ You wanted to laugh at your own joke yet the four year old didn’t understand it.

„Oookay? Can we play, sister?“ You nod and run towards her giggling.

Your relationship with Rin was almost like a real sibling. You loved her and she loved you. Everything changed as she could partake into magic lessons. She was already with her six years so good like you with eleven years. Well, almost. Yet, you felt that she is close to get better than you. You heart sinks as you compliment her. She is jiggly when even Tokiomi praised her and boast with her skills to everyone. He never had done that with you… You sadly watch him carry her around laughing as she perfected her first magic spell. You wanted to scream as you fake smile at their happiness.

„Well, Well… Y/N!“ You shriek as you blink at him.

„You didn’t ever came to me to tell me what kind of servant should serve me in the Holy Grail War. It is only a year…“ You had your mouth a bit open as you looked down ashamed.

„You were right when you said, it is not easy to find a fitting hero for our family yet…“ You put your beloved book on his desk. He watched it curiously with Rin in his arms. Rin yelled in disgust. „Oh no! The boring book of yours.“ „The epic of Gilgamesh…“ Tokiomi read the title as he looked back to you. „I never heard of him…“

You red cheeks betrayed your excitement.

„Well, he is stronger than Herakles, faster than Achilles, clever than uhhh any Heroes and he was king in Uruk. Rich was he also…“ Okay, how you put your arguments are not clever.

„He is not one of the oldest heroes. He is the first one who existed or who is written about it. That is why nobody seems to know about him. He didn’t start as a hero more like villain who…“

„Okay, Okay. I get it. You seem to be very convinced about him, right.“

„Yes. If I would partake this war, I would definitely take him as my servant.“ You clap your hand on this book like an adult. He laughs at your maturing acting.

„So enough for today.“ When you two leave his room, he watches curiously the book you brought. After this, he did some research of your hero you found and what do we have here. You may lack at you magic skills but you don’t fail with your researches. It was decided: Gilgamesh is gonna be the servant of the Tokoimi Tohsaka.

_____________________________

Part two

Well, it is still a past story where you are a child and explains the background a bit. Yet, some flashbacks are about to come. The past of course is Fate zero and the real story is ten years later , Fate stay night which is definitely turning a bit different. I don't know how much time I have to upload but I thought I should start putting the Prologue online. If you find typos you can please tell me :D Next part, Gilgamesh is coming to action.

#imaginationrealm#imagines#anime#anime imagines#fate gilgamesh#fate grand order#fate series#fate stay night#fate zero imagine#fate zero#fate zero gilgamesh#kotomine kirei#tokiomi tohsaka#fate archer#fate x you#fate x reader#fate stay night imagine#fsn#shirou emiya#fate Gilgamesh x Y/N#fate Gilgamesh x you

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tarsus Medallions

Pictured below is one of the three medallions found in the "Treasure of Tarsus", this one depicting Alexander the Great on the obverse and Alexander on horseback spearing a lion.

The Tarsus medallions were found near the ancient city of, you guessed it, Tarsus in the 19th century and are most likely victory medallions for the winners of Pythian and Olympic games held during imperial visits. The Tarsus examples were probably struck during the Reign of Severus Alexander, who could've participated in a cult surrounding Alexander the Great, hence his depictions on the medallions. From what I've seen there were only 3 of these types found in the treasure, but some sources say 4. French Wikipedia has a medallion of distinctly different style from the Rome mint depicting Severus Alexander that was supposedly found with the other three, but it doesn't really fit in with the others.

Pictured above, obverse depicts a portrait of Alexander (not Herakles apparently) wearing the remains of the Nemean lion with the reverse being the same as the first medallion.

By far my favorite of the three, this one depicts Philip II, the father of Alexander on the obverse, with the reverse depicting victory leading a quadriga.

#ancient coins#ancient rome#ancient art#ancient history#roman art#greek coins#ancient greece#greek mythology

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Omg this is my first ask to u!

I was just curious about something. As far as I've heard, there were some ancient Greeks who believed Dionysus and Herakles were from India? I'm not sure if that's completely true, especially about Dio cuz the Dionysiaca says otherwise.

So I just wanted to have some proper info about that one particular belief, where Alexander considered Nagara (Dionysopolis) as the resting (and something birth) place for Dio. And also maybe some info regarding the Herakles myth (which I'm assuming here happened during the Indo-Greek kingdom era, when he was syncretized with Buddha but again, im not sure).

Hahahahahaha apparently it iiiiiis!!!! Hahahaha!

There are definitely many different legends and myths in regards to the regions Dionysus comes from or potentially born into, for example one is that he comes from the land of the Hyperboreans, which is up to the north. It is linked to the myths of sequence between Dionysus and Apollo as they change places upon the sanctuary of Delphi with the turn of seasons.

One of course need to take into account why Greeks have their myths in the first place and connect them to specific areas. It was not as much to indicate a god's origins or the origins of his worship but rather to show that they had the right to be in an area. "If Dionysus was born here that means we Greeks were there in the first place so we have the right to be here now" or "If Zeus passed from this place then that means this place involved Greeks originally" etc. Alexander was born and raised into this culture so when he was founding or conquering cities he also seems to be taking advantage of that and establish the myths that allegedly connect the Greeks to that area. This same method was used by Alexander the Great most likely. The political and religious implications are always there.

I would expect that yes when it comes to Heracles in India it has its roots to the Greco-Buddhism, the movement that started after the war of Alexander the Great and later on by the Seleucus kingdom and all and the exchanges of culture lead to exchanges of religion and ideas and all as well. According to Appian we also hear on wars that the Seleucid king did with the Indian one. And many other moments such as this indicate this shift to the area of modern day Afganistan if I am not mistaken and the circle around them close to India. For Heracles I discover a mention that Heracles was adopted to represent Vajrapāni and was assigned as a protector of Buddha. I did find a reference of the patronage of Heracles as a god for the Kushana Empire era but unfortunately I do not have much experience on Indian history to know many details. There seem to be wrestling matches to honor Heracles to the area and also honoring the more spiritual aspects of his worship especially influenced by Hinduism or Buddhism. There are references in sculpture as well such as Gandharan sculpture that depicts Heracles by the side of Buddha where he acts as his protector. You can also see tumblr creators such as @jacobpking who depicted Heracles with Buddha:

Depictions of Heracles appear also in Tajikistan again in similar influences. I believe as you said very well it is connected to this mixture of traditions after Alexander the Great and his descendants to the area and the osmosis of culture.

That is just the scrapping of the surface that I could think of but I would be glad to ellaborate further if I can to future reblogs or discussions. Sorry I am not THAT much familiar to the history of India in general so I shall need some time to get familiar with it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

How exactly did Hercules become connected to Vajrapani to being the protector of Buddha? And what’s his relationship of the Nio in Japan?

Katsumi Tanabe notes here that despite the widespread acceptance of the view Heracles influenced the early iconography of Vajrapani in Gandhara, there’s actually no consensus on how this phenomenon originally developed. Full explanation under the cut.

For context: Greek iconographic types were commonly adopted in Central Asia - typically for Iranian deities (who especially in the east were closer to deities in the strict sense than to the Zoroastrian notion of yazatas). However, the logic of these associations was not necessarily as simple as interpretatio graeca resulting in adoption of iconography. Nothing illustrates this point better than the fact Bactrians regarded Oxus as the king of the gods, but adopted the iconography of Marsyas for him, probably because it was a relatively widespread Greek image of a river god as opposed to some deeper analogy between their respective characters. There are also cases where iconography differs from what interpretatio would suggest - Tishtrya was seemingly associated with Apollo, but iconographically took after Artemis instead on Kushan coinage. Therefore, each case needs to be approached separately.

A particularly remarkable example of Heracles-like Vajrapani (British Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

I don’t think there’s any need to undermine the transmission of iconography itself: it’s not hard to find representations of Vajrapani from Gandhara which basically look like Heracles holding a vajra (and sometimes a sword or a fly whisk) instead of a mace. However, it's worth pointing out he's actually not depicted entirely consistently in Gandharan art. In addition to the numerous Heracles-like examples, there are also cases where he resembles Silenus or another satyr; Zeus (a fairly natural match given his typical thunderbolt attribute and Varjapani’s… well, varja); Hermes; Dionysus; Alexander the Great; or an ordinary Kushan in period-appropriate clothing. Interestingly despite Varjapani being considered a yaksha, no images of him actually resemble the conventional depictions of yakshas from further south, which at the time typically drew from Indian royal iconography. Interestingly it seems only two other Buddhist figures were patterned on Greek ones in Gandharan art, Panchika (for unknown reasons depicted in the form of Hermes) and Hariti (who borrowed Tyche’s cornucopia though this was not a consistent attribute).

Ladislav Stančo in his monograph Greek gods in the East: Hellenistic Iconographic Schemes in Central Asia present a rather bold theory: the adoption of Heracles-like iconography for Varjapani was less a case of syncretism and more the result of artists familiar with Hellenistic standards being hired by Buddhists and repurposing standard forms their were familiar with already. They would often be operating only on vague descriptions of Buddhist figures they heard from the commissioners. With time these would become a standard in their own right.

However, there are other theories too - I’ll simply summarize here what Karl Galinsky wrote in his article Herakles Vajrapani, the Companion of Buddha from the recent Herakles Inside and Outside the Church: From the first Apologists to the end of the Quattrocento.

Obviously, the fact both figures are characterized by their strength is a commonly cited factor. Another possibility is that Varjapani might have absorbed Heracles’ iconography after Kushan kings started promoting Buddhism because of a shared association with royalty. Yet another option is that Varjapani was a traveling companion of the Buddha which made him a good match for globetrotting Heracles. Finally, the fact they could both fulfill many distinct roles could be an argument in favor of identification in its own right (Galinsky seems to support this proposal himself).

In the past arguments have been made that Heracles’ iconography survived in Central Asia through Vajrapani as late as in the sixth and seventh centuries (source; note the article still follows the vintage theory Vajrapani was in part a Buddhist adoption of Zoroastrian fravashi, which I haven’t seen validated in anything recent), based on a mural showing a figure wearing a lion skin from the Kizil Caves. There is a recent article which tries to salvage this point, but the author admits this is all highly speculative. In any case, by the time Varjapani reached China his attire started to change, and he came to be shown either with a bare chest or in armor, but no longer nearly naked like Heracles. He also commonly has the exaggerated facial features you’d expect from yakshas and other similar beings, as seen for example on a mural from the Mogao Caves:

(wikimedia commons)

Vajrapani appears in later Buddhist tradition in an assortment of tales which typically portray him subduing demons or unruly deities on behalf of the Buddha. None of them really show much Greek influence, though - I don’t really think Heracles is known for fighting Maheshvara, and in turn Vajrapani never got to free Prometheus or complete any of the twelve labors (though we know the myths themselves were known in Central Asia); iconography and mythology could be transmitted independently of each other.

A Japanese depiction of Varhapani - note the third eye (Art Institute Chicago; reproduced here for educational purposes only) In Japan, Varjapani (Kongōshu, 金剛手; Shukongōshin, 執金剛神; Kongō-rikishi, 金剛力士 etc.) only appeared after a long process of transformations in Mahayana tradition, and his depictions generally reflect Chinese artistic conventions. The Niō, literally “benevolent kings”, are a double manifestation of him and similarly reflect a Chinese model. I don’t think there’s any real reason to claim there’s all that much Heracles in them. JAANUS notes that multiple identities could be assigned to them, though none particularly consistently. There’s a case to be made that the fact they are most commonly statues guarding temple gates is basically the core of their character judging from the proliferation of legends which revolve around this (for a Chinese example see here, Japanese ones are mentioned briefly in the linked JAANUS entries). They also only became widespread in the Kamakura period, centuries after even the boldest theories suggest the survival of some memory of Heracles in Buddhist sources. To put it differently: both Heracles and Nio are undeniably parts of Varjapani's history, but they are not necessarily a part of each other's history just because of that.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gandharan Buddha

Schist frieze from Gandhara, 2nd century AD, at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, EN.

Gandhara After Alexander the Great passed through the area of northern Pakistan known in antiquity as Gandhara, many sculptors in the region appear to have been considerably influenced by classical styles, blending these with local eastern traditions of both style and subject. So the hero Herakles may appear beside the Buddha, and the robes of the Buddha or Bodhisattva often show classical influence. This relief shows the Buddha (centre) with a bearded figure on the viewer's left, who can be identified as the classical hero Herakles. To the right of the central figure is a figure in classical costume holding onto a female figure in traditional Gandharan attire.

0 notes

Note

Following up on your answer to that person’s question about Barsine, if Herakles was Alexander’s son, why did he ignore him? Maybe I’m wrong, but I haven’t gotten the impression from what I’ve learned about Alexander that he’s indifferent to family, especially a baby that’s his.

Aaaaand this is precisely why I’m still not 100% sold that Herakles was his.

Herakles of Macedon, Alexander's "Forgotten?" Son

Although as Monica (D’Agostini) reminded me, the baby would have been only about four when ATG died, so at that age, it was quite traditional for children to remain with their mother—and he’d sent Barsine to Pergamon, the Aeolian area where her family had a great deal of power and land. Typically, very young children were left out of historical accounts without a particular reason to mention them. One would think the birth of a healthy prince would count, but we hear about Alexander’s own birth only because notice of it coincided with two other pieces of good news for Philip (and because he became so important later). We don’t hear about Arrhidaios’s birth, much less any of the girls. Even the last is mentioned only because of how she died at Olympias’s hands.

Similarly, we know about Roxane’s pregnancy and stillbirth/miscarriage from the (very late) Metz Epitome. And we know Statiera died in childbirth from a tossed off comment in Plutarch and Justin. Arrian doesn’t mention either of these. That’s caused some to dismiss them both as fabricated, but the problem is we wouldn’t expect the campaign/military-focused Arrian to talk about them. Curtius does at least talk about Statiera, but because she fits into his narrative of an (early) clement ATG, he doesn’t attribute her death to childbirth but exhaustion—in part because a pregnant Statiera would conflict with how he’s presenting Alexander at that point in his narrative, suggesting that maybe he didn’t keep his hands off another man’s wife.

Monica thinks Barsine stayed with Alexander all the way into Baktria and was probably sent to Pergamon either when she became pregnant or after the baby was born. I’d bet on the former, to get her the best medical care. Remember Barsine’s age; she was older than Alexander—possibly approaching 40. Her daughter by Memnon was old enough to be married to Nearchos at Susa—which is why, after Alexander’s death, Nearchos brought Herakles forward as a candidate for king. The daughter may have been as young as 14/15, but that still makes her mother 35+ in 324. Barsine was married to Mentor before Memnon, although perhaps not for very long. Alexander probably didn’t want her trying to have a baby at the back of nowhere at her age, regardless of how many she’d already had. Artabazos “retired” around that same time, so perhaps they traveled back west together. (I’d have to check whether he stayed at the court.)

But the histories don’t reveal any of this. It’s pieced together from the age of Herakles at his death and mention of Barsine being given to Alexander as a mistress after Issos, plus the later prominence of her family—although that could have owed to long-standing guest-friendship between Artabazos and the Macedonian court. IOW, Barsine likely got her position as mistress because of her family’s earlier connection to the Argeads, and in turn, her position as mistress led to Artabazos’s elevated treatment later.

So that’s one likely scenario. But there are a few others. Barsine may have been a cover for Alexander’s affair with Statiera. As we know, Statiera (probably) died in childbirth but the baby couldn’t have been Darius, and therefore almost had to be Alexander’s. After she died (right before Gaugamela), Alexander may have left all the women in Babylon. He certainly didn’t drag Darius’s daughters off to Baktria. If that were the case, timing-wise, Herakles couldn’t be Alexander’s.

Or it's possible Barsine was Alexander’s mistress (not just a cover) even as he also had an affair with Statiera. No expectations existed for Alexander to have only one mistress at a time. I find it unlikely that he took up with Statiera until after he’d received at least the first letter from Darius, making it clear Darius wouldn’t negotiate for his family. So he may have started with Barsine, then took up with Statiera too, but also kept Barsine. Barsine's knowledge of Persia would have been invaluable to him. As for bringing Barsine to Baktria but not Darius’s daughters, they were much younger and perhaps less tough. Certainly they were less experienced politically, compared to the older, bilingual Barsine. So, I can see reasons for bringing her and not them.

The problem is simply that, when it comes to the women traveling with Alexander’s army, we are told so VERY little, from which we are then forced to infer so much. Ergo, disagreement easily ensues over how to interpret the titbits. That’s a large part of why I was open to hearing Monica’s alternative theories. (Well, that and the fact it’s not central to anything I’ve published, so any course-correction isn’t personal—ha.)

The difficulty is just that, after she’s brought to Alexander following Issos, we hear nothing about Barsine again until her daughter is selected for Nearchos’s wife. Then not again till Alexander’s death when Nearchos champions her son (and fails). Then not again until after Arrhidaios and Alexander IV are both dead, and Polyperchon tries to put Herakles forward but is bribed/talked out of it by Kassandros, so instead he kills both the 18-year-old Herakles and Barsine.

The problem is, we wouldn’t necessarily expect to hear about Barsine and Herakles, so that silence isn’t especially significant. That’s why an argument from silence is problematic. Alexander may, in fact, have taken an interest in his son, but wanted to keep him away from court until he was older, especially if he wasn’t legitimate. Alexander was all-too-accustomed to the politics of polygamy and recognized that bringing him to Babylon could make him a target, especially if he wasn’t old enough yet to travel with his father (under his father’s eye and protection). Alexander NOT taking a big interest in him would, ironically, act as protection.

Also, we don’t actually know where Barsine and Herakles were when Alexander died, except apparently not in Babylon. Alexander might have seen the boy earlier, however, once he was back in the west. Barsine could very well have met him to Ekbatana, as the Persian Royal Road goes from Sardis north until east of the Tigris, when it swings south towards Susa. But Persia had a LOT of roads, not just that one, and a road forked off the main trek to the capital of Ekbatana in Media. Easy travel. ATG was to have held a major festival there with athletic contests and all sorts of things, but everything got overshadowed by Hephaistion’s death.

Of more import is why he was passed over at Alexander’s death. I actually find this to be the one REAL sticking point in arguments about his parentage, but it cuts both ways.

Given that nobody knew if Roxane’s baby would be male, and the mental infirmity of Arrhidaios (enough that Perdikkas was appointed regent, as for a child, of a man in his mid-30s!), not choosing Herakles presents a problem. Any Argead male could inherit. Some have pointed out the resistance to Roxane’s son to explain resistance to Herakles too; not only was he part Persian, but the son of a mere mistress, not wife. I find that a weak argument. Barsine was half Greek (her mother was Greek, sister of Mentor and Memnon of Rhodes), making Herakles less than half Persian. If anything, the son of the thoroughly Hellenized Barsine would have been preferable to the unborn child of “barbarian” Roxane, legitimate or not.

If there were doubts about him AS Alexander’s son, however, that could explain why Nearchos’s suggestion was ignored. Except if he’d expected that to be a problem, it seems unlikely Nearchos would've put him forward. Perhaps years later, when Polyperchon tried, a cuckoo could have been slipped in, but in 323, that would've been harder. Also, the fact Kassandros paid off Polyperchon to kill Herakles, the last surviving Argead—didn’t just claim he wasn’t Alexander’s son—suggests Kassandros believed he was Alexander’s son.

Yet it's still a puzzle to me why Herakles was passed over, a healthy male child, in favor of the mentally incapable brother and unborn baby. Perhaps if we had more of Diodoros’s book 18, as well as Arrian’s account of what happened immediately after (the book exists in only in a few tantalizing fragments)—or for that matter Nearchos’s own account!—we’d get a better idea of what transpired in Babylon that July.

#asks#Barsine#Herakles of Macedon#Alexander the Great#Artabazos#Nearchos#Nearchus#Arrian#Curtius#Plutarch#Justin#Alexander's children#sons of Alexander the Great

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

~ Head of Alexander the Great as young Herakles. Culture: Greek Period: Hellenistic Date: late 4th-3rd century B.C. Medium: Marble

#ancient#ancient art#ancient sculpture#head of alexander the great as young herakles#hellenistic#greek#4th century b.c.#3rd century b.c.

282 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alexander The Great wearing a lion skin, a frequent attribute on monetary portraits alluding to Herakles, his mythical ancestor; inscribed letters on the face are later additions. Pentelic marble, ca. 300 BC. Found in Kerameikon. National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece.

#alexander the great#lion skin#herakles#pentelic marble#300 bc#ancient greece#ancient history#ancient world#history#kerameikon#national archaeological museum#athens#greece#history lovers#education

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I’m Nik. I was wondering what’s ur opinion on worshiping/working with demigods? Thx💛

Hi Nik! I'm sorry this is all the way from October I simply haven't had the energy.

🍁 Definition 🍁

Well people view "demigods," in different ways. The word in English comes from Latin "semideus" (semi meaning half, deus meaning god) for lesser divine beings.

🔹This could include what a lot of literature labels "lesser gods" or "minor gods." For example: nymphs such as a Dryads (trees, forests, groves) or Naiads (fresh waters).

🔹This could include what Homer & Hesoid both referred to people of "good character, family, strength, and power" as hemitheoi (hemi meaning half, theoi meaning gods) after death. This individual didn't need to be part immortal to make it into this category. They tended to be people with hero worship cultus. They could be real people or legendary ancestors whose historicity is dubious.

🔹Related to the above, sometimes great rulers were considered Gods, such as Alexander the Great or various Roman emperors. Sometimes while alive sometimes posthumously.

🔹Some consider an individual with one mortal parent and one immortal parent to be demigods, Herakles would be a good example; his father being the immortal Zeus & his mother being the mortal Alcmene. However, in some cases Dionysos was considered the son of the immortal Zeus and the mortal Semele.... and he was one of the 12 Olympians in some locations and even more important in various other cults so this categorization doesn't hold up well.

🍁 Other Pantheons? 🍁

The word comes from Latin and is most properly used in regards to the Roman and by extension of history Greek pantheons (The semideus and hemitheoi); and possibly closely related ones. But of course people are going to plaster the term across any other pantheon as they see fit so lets talk about that for a second.

I find it difficult to use this term in regards to other pantheons because other pantheons have there own terms.

I'm a Sumerian polytheist so if I was to attempt to use these characteristics to pick out Mesopotamian demigods I might bring up these examples:

🔹It could be say, Lama/Lamassu goddesses & Alad/Šedu Gods, who were unnamed protective deities who might be regarded by modern eyes as "lesser divine" compared to the named city gods.

🔹Pazuzu a demon, not god, who was used in exorcism rituals, as protective talisman, and was considered to hold the much more evil Lamaštu and Lilû demons at bay. Is he a demigod? As a protective powerful being.

🔹Mortals who became immortals— Ziusudra, Ūt-napišti, (possibly) Atrahasis—but there is no term I know of for "half god" that could apply to them. They simply did a thing (build an ark) and were granted immortality.

🔹Deified rulers (while alive and posthumously) especially the kings of Ur III. Such as Narām-Suen or Samsuditāna, they claimed to be sons or brothers of various Gods, but I don't know if they would be seen on the exact same level as the Gods or a lesser level that could be labeled "demigod."

🔹Gilgameš (In Sumerian: Bilgames) is a mess when it comes to this idea. He was likely a historical king during the earliest part of Early Dynastic Period, if he was deified during his life is unknown. By the later part of the Early Dynastic period there was a deity being worshipped named Bilgames/Gilgameš that probably derived from this early king. He was a patron deity of King Utu-heĝal of Uruk, as a full divine being. Yet, the Gilgameš known in the most well known tales, is not a God, he is not even immortal. He is more akin to a hero going on adventures and destroying monsters. Some accounts say he is the son of the Goddess Ninsun and a mortal man which would also make him half mortal half immortal [edit: I think hes actually described as 2/3rds divine 1/3 human]. The very few depictions we are certain show Gilgameš do not have him with a horned cap the sign of divinity. So is he a demigod? a deified king? a half mortal half immortal? a hero? a great ancestor? Most academics use the term hero for him based on the myths even though a much more ancient Bilgames/Gilgameš was possibly worshipped as a full fledged deity.

It really does not make sense to try and parse out Mesopotamian religious figures using this word's conception (though I'm sure it appears in academia at some point) thus it doesn't make sense to use it elsewhere either. The term, like most, does not work well for pantheons that it does not derive from. I'm sure you'll see it used for pantheons and religions across the entire globe but I can't speak to any of them.

🍁 My Category Summary 🍁

For the Roman & Greek traditions (and any surrounding similar ones that I'm not going to attempt to pretend I know such as Etruscan)

Category 1: "lesser divine beings"

Category 2: People of good character after death who eventually received honor and worship. Historicity aside. (Homer & Hesoids' "hemitheoi")

Category 3: Rulers, Emperors

Category 4: Half mortal half immortal individuals

In these contexts worship of demigods in Greece & Rome has deeply entrenched historical precedent. I would see their worship as no different than worshipping other Gods or spirits from a revivalist standpoint. I love me some Dryads and have considered Herakles worship. I do find worshipping Roman emperors odd but they were deemed Gods and had cultus so I can't state that it's ahistorical or inherently bad. Basically: go right ahead! Honoring and worshiping these demigods.

🍁 Modern People 🍁

However, what about these categories in the modern world.

Category 1: Well that hasn't changed much "lesser divine beings" are still the same

Category 2: This could be construed as worshipping modern individuals who fall into this "good character, good family, strong, and powerful" idea described above. For example, idunno lets pretend Albert Einstein falls into that characterization in someone's opinion. I'd be deeply uncomfortable with someone declaring and worshipping him as a demigod. However, including him in ancestor worship seems to be a valid way to honor him, or so thats the consensus among most modern pagan and polytheists that I take no issue with.

Category 3: This might lead someone to the idea of worshipping "recent" powerful rulers. I mean Alexander the Great was a bloody conqueror who made a vast empire. ...So was Queen Victoria (albeit without going into battle) she ruled over the largest human empire in history. I'd be deeply uncomfortable and essentially offended to see her worshipped as a demigod considering the sheer brutality the colonies suffered under her reign. This idea also plays a role in white supremacist groups unfortunately, in some "Esoteric Hitlerism" where Hitler is essentially a divine figure, savior of humankind, deified as a demigod. Unlike the heros and ancestors of category 2 deified rulers tend to get their god status from their conquests and policies which should be looked at very critically. Its one reason I take pause when I see pagans whose primary Gods are Roman emperors.

Category 2/3 offshoot: Category 2 was defined by the person after death. While category 3 could include prior to their death. This could lead to worshipping [insert currently living person] as a demigod. Which makes me deeply uncomfortable, especially because that person probably hasn't consented.

Category 4: This is kind of up to the individual. Most mythical characters who are half/half have their own ancient cultus that will tell you whether they were worshipped as heros (demigods) or Gods

Modern communities: Godkin; Godshard; Demigod (as an identity); Offspring of God X (claiming to be literally part immortal); etc etc etc. No.

🍁 TL;DR🍁

The word has varying meanings. There is plenty of historical examples and definitions for demigod honor and worship in the Greek and Roman traditions (and probably extremely close or syncretic ones). The word should be avoided for beings outside those pantheons & traditions in my opinion. We should be very very careful when using it to talk about modern (or relatively modern) humans both living and dead.

-definitely not audio proof read sorry for whatever my dyslexia did with this post-

11 notes

·

View notes

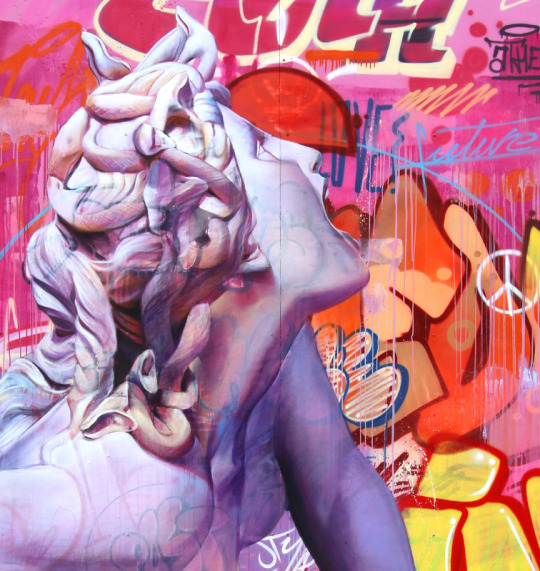

Photo

RENEGADES was an exciting commission with renowned Spanish urban artists PichiAvo. The commission consisted of three outdoor, free-standing portraits, each depicting a woman from ancient Greek history or mythology. RENEGADES pays homage to three women who were, in their own way, renegades. Women who broke away from the traditional roles associated with women of the time and made an indelible mark on history.

MEDUSA The Gorgon With her serpent hair, Medusa is an instantly recognisable figure. Possibly one of the most maligned characters in Greek mythology, a close look at her story reveals a nuanced and complex character who suffered at the hands of both men and women and ultimately became the archetypal femme fatale.

HIPPOLYTA The Amazon Long believed to be a myth, Amazons were a tribe of warrior women who were the archenemies of the ancient Greeks. Ancient accounts describe them as fierce and fearless in battle, a stark contrast to the cloistered and dependent Greek women. Hippolyta, an Amazonian queen, figures predominantly in the stories of Herakles and Theseus, both of which end with her death.

PHRYNE The Courtesan Phryne, an Athenian courtesan notable for her intelligence and wit was a desired and sought after companion amongst some of the most fêted intellects of all time. A self-made woman, she became so rich that she offered to pay for the rebuilding of the walls of Thebes, which were destroyed by Alexander the Great in 335 BCE. The city patriarchs refused her offer, leaving the walls in ruins.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nemean Lion

In mythology, the Nemean lion was a large fearsome monster that terrorised Nemea in the Argolid, with a hide impervious to iron, bronze or stone, and claws that could shatter weapons.

Hesiod has an early mention of the Nemean lion in Theogony 8-7 century BCE

[...] the nemean lion, which Hera, Zeus’ honoured wife, fostered and settled in the foothills of Nemea, an affliction for men. There it lived, harassing the local peoples, monarch of Tretos in Nemea and of Apesas; but mighty Heracles’ force overcame it. (trans. M L West)

Hesiod however does not mention the classic impenetrable skin that the lion has become known for. Though Hesiod’s wording is confusing, he does imply just before this passage, as do other sources, that the lion’s mother is Echidna and father Typhon, the parents of all the worst of Ancient Greek monsters, including Cerberus, Drakon and the Hydra. Hera then reared the lion and set it loose on the Argolid. Others say the lion was cast down by Selene at Hera’s request, or that Hesiod meant it was the offspring of the Chimera.

The fearsome Leon Nemeios was slain by Herakles at the behest of King Eurystheus as the first of the hero’s twelve labours. Herakles tried to shoot the lion down with his arrows, but they bounced off its golden hide. He then cornered the lion in a cave at the base of Mt Tretos in Nemea, having blocked one of the cave’s two entrances, and, clubbing the beast with his iconic weapon, grappled with it while the lion was dazed until he choked it to death with sheer force. Herakles attempted to skin the beast but his weapons still couldn’t pierce the skin. Goddess Athena whispered the secret to him; pierce the lion’s hide with its own claws.

The common iconography of Herakles wearing the lion skin seems fixed from 6 century BCE onward, with the earliest representations coming from the islands and eastern Greece. Herakles, poetically depicted as larger than life, wore the huge nemean lion’s skin as a perfectly fitting cloak, using its protective properties as a shield throughout his career. Herakles and his descendants, notably Alexander the Great, can be easily identified by the mighty lion mane and jaw worn as a helmet, and the skin as a cloak with the front paws tied in a knot at his chest. This imagery, in part, gave rise to the nautical rope knot known as the Hercules Knot.

Lions are no longer native to Greece, though Herodotus does say they were still present in his time. The image of the lion and the fight scene with Herakles is well documented and unmistakable. What’s interesting is the Nemean lion’s domain, Mt Tretos, means “to pierce” or “to perforate” because of a ravine dug in the base of the mountain. A lion with impenetrable skin lurked on a torn mountain, or, as Tyrrell says, ‘A perforated mountain shelters a lion that cannot be perforated.’

On a more personal note, that Herakles’ first labour was won by strength alone, with his bare hands, feels more significant than any of his other acts. He was known as a skilled archer, a formidable man with talents beyond any normal mortal, yet to be reduced to fighting with his hands with no aid from the onset cements his prowess to me. Even without the lion hide’s properties I believe he would have worn the skin regardless to show the world what he was capable of. Indeed, there are some myths that state the hide he wore was that of the Kithaeron lion, the first he slew as a much younger man.

🦁

Sources:

Theoi.com

Wikipedia (image 1)

Perseus (image 2)

Apollodoros, Library 2.5.1

From Bowman to Clubman: Herakles and Olympia

On Making the Myth of the Nemean Lion

#Herakles#Herakles worship#Hercules#twelve labours#Greek mythology#Hellenic polytheism#hellenismos#Hellenic paganism#Argive

36 notes

·

View notes