#Pawnee Illinois

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Carl and the Ferris Wheel!

Keith and I both love the Ferris Wheel. It has been my favorite ride since I was a kid. Since Keith and I have been together, when we have the opportunity to ride the Ferris Wheel we take advantage. “I love seeing the view of the town from the top,” Keith said when we took a ride last weekend during the Pawnee Prairie Days. When we think of Ferris wheels, we think of our friend Carl Davis…

View On WordPress

#Allis Chalmers#antique tractor collector#Aumann Auctions#career#Carl Davis#carnival#Centennial Wheel#Chicago Illinois#Chicago World&039;s fari#Christian County Fairgrounds#Conners Family Amusement#David Bradley#draftsman#Eli Bridge Company#Ferris Wheel#Jacksonville#Jacksonville Illinois#Joe Harris#John Deere garden tractors#John Deere tractors#Navy Pier#Pawnee Illinois#Pawnee Prairie Days#Prairie Days#Priaireland#the Kitty Wheel#tractor#welder#William Sullivan

0 notes

Text

I had a long four-day weekend working on the cabin, with some help from my mom and sister. They made the drive all the way up from Pawnee, Illinois just so they could spend my mother's 60th birthday doing construction work. We had s good time. It didn't rain. We got a ton of work done. My mom discovered that I have wild strawberries growing all over the property. And then we got ice cream. All in all, a pretty nice weekend.

Also, check out the views of the forest from the windows!

0 notes

Photo

This Indian Country: American Indian Activists and the Place They Made by Frederick Hoxie (2012)

Frederick E. Hoxie, one of our most prominent and celebrated academic historians of Native American history, has for years asked his undergraduate students at the beginning of each semester to write down the names of three American Indians. Almost without exception, year after year, the names are Geronimo, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. The general conclusion is inescapable: Most Americans instinctively view Indians as people of the past who occupy a position outside the central narrative of American history. These three individuals were warriors, men who fought violently against American expansion, lost, and died. It's taken as given that Native history has no particular relationship to what is conventionally presented as the story of America. Indians had a history too; but theirs was short and sad, and it ended a long time ago.In This Indian Country, Hoxie has created a bold and sweeping counter-narrative to our conventional understanding. Native American history, he argues, is also a story of political activism, its victories hard-won in courts and campaigns rather than on the battlefield. For more than two hundred years, Indian activists—some famous, many unknown beyond their own communities—have sought to bridge the distance between indigenous cultures and the republican democracy of the United States through legal and political debate. Over time their struggle defined a new language of "Indian rights" and created a vision of American Indian identity. In the process, they entered a dialogue with other activist movements, from African American civil rights to women's rights and other progressive organizations.Hoxie weaves a powerful narrative that connects the individual to the tribe, the tribe to the nation, and the nation to broader historical processes. He asks readers to think deeply about how a country based on the values of liberty and equality managed to adapt to the complex cultural and political demands of people who refused to be overrun or ignored. As we grapple with contemporary challenges to national institutions, from inside and outside our borders, and as we reflect on the array of shifting national and cultural identities across the globe, This Indian Country provides a context and a language for understanding our present dilemmas.

Image 1

15: My informal quiz is intended to prod students to look beneath the surface of the popular beliefs that define Native people as exotic and irrelevant. I also ask students to consider why it is that Americans so easily accept the romantic stereotype of Indians as heroic warriors and princesses? Why don’t we demand a richer, three-dimensional story? I pose a Native American version of the question the African American writer James Baldwin often asked white audiences a generation ago: “Why do you need a nigger?” My question is the same: Why do Americans need “Indians”—brave, exotic, and dead—as major figures in national culture?

17: This book counters that preference by presenting portraits of American Indians who neither physically resisted, nor surrendered to, the expanding continental empire that became the United States. The men and women portrayed here were born within the boundaries of the United States, rose to positions of community leadership, and decided to enter the nation’s political arena—as lawyers, lobbyists, agitators, and writers—to defend their communities. They argued that Native people occupied a distinct place inside the borders of the United States and deserved special recognition from the central government. Undaunted by their adversary’s military power, these activists employed legal reasoning, political pressure, and philosophical arguments to wage a continuous campaign on behalf of Indian autonomy, freedom, and survival. Some were homegrown activists whose focus was on protecting their local homelands; others had wider ambitions for the reform of national policies. All sought to overcome the predicament of political powerlessness and find peaceful resolutions for their complaints. They struggled to create a long-term relationship with the United States that would enable Native people to live as members of both particular indigenous communities and a large, democratic nation.

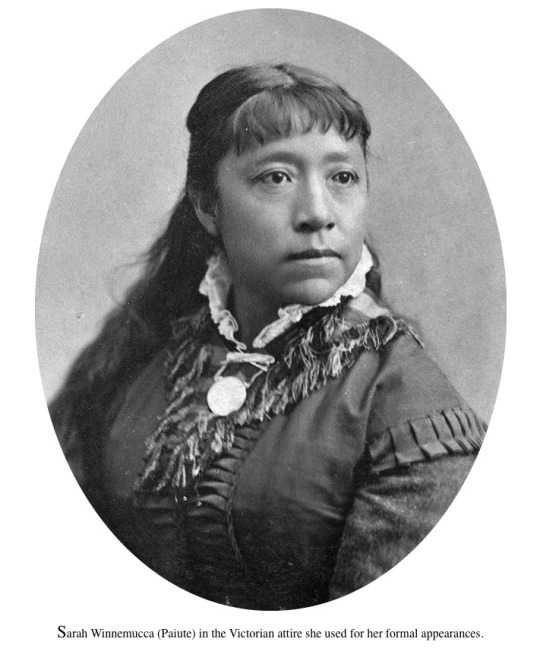

The story of these activists crosses several centuries. It opens in the waning days of the American Revolution, as negotiators in Paris set geographical boundaries for the new nation that ignored Indian nations that had fought in the conflict and had been recognized previously in international diplomacy. Native activists take center stage in the 1820s, when nationalistic U.S. leaders abandoned an earlier diplomatic tradition and pressed Indian leaders to surrender their homes to American settlers. The Choctaw James McDonald, the first Indian in the United States to be trained as a lawyer, is the protagonist of chapter two. McDonald became his tribe’s legal adviser and drew on American political ideals to defend Indian rights, thereby laying the foundation for future claims against the United States.A generation after McDonald, the Cherokee leader William Potter Ross developed and widened the young Choctaw’s arguments. During the middle decades of the nineteenth century he traveled among Indian tribes in the West as well as to Washington, D.C., to recruit other Native leaders to defend tribal sovereignty. Among those who followed in Ross’s wake were Sarah Winnemucca, a Nevada Paiute who in the 1880s became a nationally famous writer, lecturer, and lobbyist, and a group of remarkable Minnesota Ojibwe tribal leaders who battled both at home and in Washington, D.C., to preserve their tiny community on the shores of Mille Lacs Lake.In the twentieth century the leading activists were often polished professionals like Thomas Sloan, an Omaha Indian who became an attorney and established a legal practice in Washington, D.C. The first Indian to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court, Sloan helped found the Society of American Indians in 1911 (serving as its first president) and encouraged other community leaders to create similar networks of support. In the 1930s, when Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal offered those leaders opportunities to speak out in defense of their tribes, these networks brought forth tribal advocates such as the Seneca Alice Jemison and the Crow leader Robert Yellowtail, as well as a new generation of intellectuals and thinkers, among them the Salish writer and reformer D’Arcy McNickle and the visionary scholar Vine Deloria, Jr., who by the time of his death in 2005 had become the leading proponent of indigenous cultures and tribal rights in the United States.

..

Vocal opposition to Indian landholding in Mississippi began in 1803, after Napoleon had suddenly decided to sell the entire territory to the Americans. The French emperor’s decision immediately transformed the Choctaw homeland from a distant border area to an inland province that boasted hundreds of miles of frontage on a river that was destined to become the nation’s central highway.15 Secure borders and the lure of plantation agriculture triggered a surge of settlement. The American population in the region doubled between 1810 and 1820 and then doubled again by 1830. New towns clustered along the east bank of the Mississippi as well as on the lower reaches of the Tombigbee River, two hundred miles to the east.The American immigrants were soon calling for the creation of two territorial governments in the area. Congress had first organized Mississippi Territory in 1798 as a hundred-mile-wide swath of unsurveyed land hugging the east bank of the great river and then in 1803, had expanded its borders so that it stretched south from Tennessee to the Gulf. Finally, in 1817, the region took its modern shape when the Tombigbee settlements became the Alabama Territory, Mississippi’s eastern neighbor.Events on America’s northwestern frontier echoed those along the Gulf. Secure borders, a surging settler population, and aggressive local leaders encouraged the rapid organization of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois into territories and states during Jefferson’s presidency. (Ohio became a state in 1803; Indiana in 1816; Illinois in 1818.) Jefferson championed both traditional Indian diplomacy and westward expansion. He understood the value of traditional diplomacy, but he also understood the rising power of western politicians and was far more likely to accommodate them.In 1808 Jefferson supported a major purchase of Choctaw land. He noted that while it was “desirable that the United States should obtain from the native population the entire left (east) bank of the Mississippi,” federal authorities were also determined “to obliterate from the Indian mind an impression . . . that we are constantly forming designs on their lands.” The Choctaws’ current debt of more than forty-six thousand dollars, he explained, provided a solution to this dilemma. Owing to “the pressure of their own convenience,” Jefferson reported, the Choctaws themselves had initiated this sale of five million acres of their land. He wrote that he welcomed this “consolidation of the Mississippi Territory,” and the Senate quickly ratified the agreement.16

...

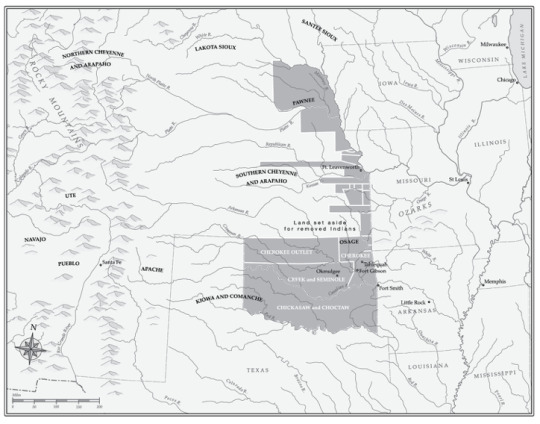

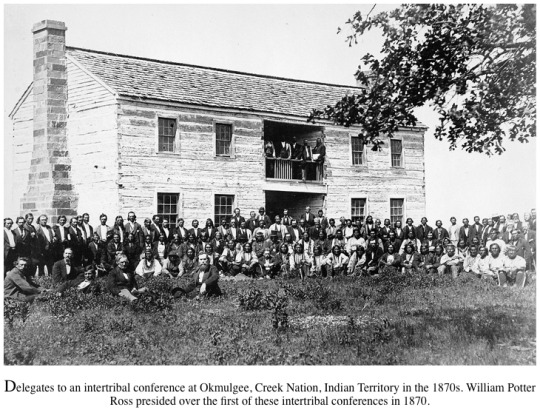

95: Leaders of the removed tribes were quick to promote the idea of multitribal “international councils” aimed at promoting peaceful relations among the tribes in Indian Territory and the surrounding region. These councils grew out of a tradition of peace conferences that U.S. officials had organized prior to removal to reduce tensions between western tribes (particularly the Osages, Pawnees, Kiowas, and Comanches) and the eastern Indians who had begun to migrate voluntarily to the West early in the century. Fort Gibson, erected in 1822 along the Arkansas River at a spot near the future site of the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah, had been the scene for several of these gatherings. One such meeting in 1834 involved more than a dozen tribes (including recently arrived Delawares and Senecas from the Midwest) that pledged friendship to one another and agreed to meet again to conclude a formal treaty. The 1835 Camp Holmes treaty, negotiated on the prairies west of Fort Gibson, fulfilled that goal. It established peaceful relations between the eastern tribes such as the Cherokees, Choctaws, and Creeks, and local groups such as the Wichitas and Osages. A second gathering the following year extended the Camp Holmes agreement to the Kiowas and Kiowa-Apaches.15In the 1840s the Cherokee tribal government, along with the governments of neighboring groups, began hosting their own intertribal meetings. They took this step both because they were eager to maintain good relations with the powerful tribes that had previously occupied their new homelands—particularly the Osages, Kiowas, and Comanches—and because they were increasingly conscious of threats to their borders. To the south, the new Republic of Texas, dominated by slaveholders, seemed determined to remove its resident tribes and create a homogeneous, independent settler nation on the model of the United States. The Cherokees had little interest in antagonizing these aggressive neighbors, many of whom were recent arrivals from Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee. Tribal leaders in Tahlequah were also aware that Mexican officials to the west, still resentful of the Texans’ recent success in their war of independence, were eager to form alliances with Comanches and other groups who had traditionally raided agricultural communities along the Arkansas River. To the north, resettled tribes from the American Midwest—particularly Delawares, Shawnees, Potawatomis, and Wyandots—were making new homes on the Missouri frontier. The disruptions accompanying their arrival triggered yet another round of retaliation and resentment among indigenous groups.16Large intertribal gatherings began in 1843. In June of that year more than three thousand representatives of twenty-two tribes gathered at Tahlequah in response to invitations sent out by John Ross and Roly McIntosh, the chief of the Creeks. For four weeks the delegates made camp across a two-mile-wide prairie and participated in round dances, ball games, and parades. William Potter Ross, barely a year removed from his Princeton graduation, was among them.When the formal sessions began, Chief John Ross reminded the delegates of the serious work before them. “Brothers,” he cried, “it is for renewing in the West the ancient talk of our forefathers, and of perpetuating forever the old pipe of peace . . . and of adopting such international laws as may redress the wrongs done by the people of our respective tribes to each other that you have been invited to attend the present council.” In addition to securing pledges of peace from all who attended, Ross won approval for eight written resolutions that established rules of conduct and included the declaration “No nation party to this compact shall without the consent of all the other parties, cede or in any manner alienate to the United States any part of their present territory.”17One white observer predicted that the 1843 gathering would “disperse without having done anything,” but the resolution regarding land cessions was a clear signal that the men who had been victims of removal had a serious purpose. They wanted to forge an alliance that could hold their enemies at bay.18 Often ignored by outsiders, these gatherings continued throughout the coming decade.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

On This Day...

1775 – The Olive Branch Petition, adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 5, 1775, was signed by members of the Continental Congress. The petition was a final attempt to avoid a full-blown war between the Thirteen Colonies that the Congress represented, and Great Britain. The petition affirmed American loyalty to Great Britain and entreated the king to prevent further conflict. In August 1775 the colonies were formally declared to be in rebellion by the Proclamation of Rebellion, and the petition was rejected in fact, although not having been received by the king before declaring the Congress-supporting colonists traitors. 1776 – In Philadelphia, the Liberty Bell rings out from the tower of the Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall), summoning citizens to the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence, by Colonel John Nixon. On July 4, the historic document was adopted by delegates to the Continental Congress meeting in the State House. However, the Liberty Bell, which bore the apt biblical quotation, “Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land unto All the Inhabitants Thereof,” was not rung until the Declaration of Independence returned from the printer on July 8. In 1751, to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of Pennsylvania’s original constitution, the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly ordered the 2,000-pound copper and tin bell constructed. After being cracked during a test, and then recast twice, the bell was hung from the State House steeple in June 1753. Rung to call the Pennsylvania Assembly together and to summon people for special announcements and events, it was also rung on important occasions, such as when King George III ascended to the throne in 1761 and to call the people together to discuss Parliament’s controversial Stamp Act of 1765. With the outbreak of the American Revolution in April 1775, the bell was rung to announce the battles of Lexington and Concord. Its most famous tolling was on July 8, 1776, when it summoned Philadelphia citizens for the first reading of the Declaration of Independence. As the British advanced toward Philadelphia in the fall of 1777, the bell was removed from the city and hidden in Allentown to save it from being melted down by the British and used for cannons. After the British defeat in 1781, the bell was returned to Philadelphia, which was the nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800. In addition to marking important events, the bell tolled annually to celebrate George Washington’s birthday on February 22, and Independence Day on July 4. In 1839, the name “Liberty Bell” was first coined in a poem in an abolitionist pamphlet. The question of when the Liberty Bell acquired its famous fracture has been the subject of a good deal of historical dispute. In the most commonly accepted account, the bell suffered a major break while tolling for the funeral of the chief justice of the United States, John Marshall, in 1835, and in 1846 the crack expanded to its present size while in use to mark Washington’s birthday. After that date, it was regarded as unsuitable for ringing, but it was still ceremoniously tapped on occasion to commemorate important events. On June 6, 1944, when Allied forces invaded France, the sound of the bell’s dulled ring was broadcast by radio across the United States. In 1976, the Liberty Bell was moved to a new pavilion about 100 yards from Independence Hall in preparation for America’s bicentennial celebrations. 1778 – George Washington headquartered his Continental Army at West Point. 1918 – Ernest Hemingway is severely wounded while carrying a companion to safety on the Austro-Italian front during World War I. Hemingway, working as a Red Cross ambulance driver, was decorated for his heroism and sent home. Hemingway was born in 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois. Before joining the Red Cross, he worked as a reporter for the Kansas City Star. After the war, he married the wealthy Hadley Richardson. The couple moved to Paris, where they met other American expatriate writers, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound. With their help and encouragement, Hemingway published his first book of short stories, in the U.S. in 1925, followed by the well-received The Sun Also Rises in 1926. Hemingway would marry three more times, and his romantic and sporting epics would be followed almost as closely as his writing. During the 1930s and ’40s, the hard-drinking Hemingway lived in Key West and then in Cuba while continuing to travel widely. He wrote The Old Man and the Sea in 1952, his first major literary work in nearly a decade. The book won the Pulitzer Prize in 1953. The same year, Hemingway was wounded in a plane crash, after which he became increasingly anxious and depressed. Like his father, he eventually committed suicide, shooting himself in 1961 in his home in Idaho. (Ernest Hemingway on crutches in 1918, outside the American Red Cross hospital in Milan. The protagonist in his World War I novel, A Farewell to Arms, is an American ambulance driver on the Italian front who was wounded in both legs.)

1944 – The US 1st Army is reinforced with 2 divisions arriving from Britain. There is heavy fighting along the road from Carentan to Periers. 1947 – In New Mexico the Roswell Daily Record reported the military’s capture of a flying saucer. It became know as the Roswell Incident. Officials later called the debris a “harmless, high-altitude weather balloon. In 1994 the Air Force released a report saying the wreckage was part of a device used to spy on the Soviets. 1959 – Maj. Dale R. Ruis and Master Sgt. Chester M. Ovnand become the first Americans killed in the American phase of the Vietnam War when guerrillas strike a Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) compound in Bien Hoa, 20 miles northeast of Saigon. The group had arrived in South Vietnam on November 1, 1955, to provide military assistance. The organization consisted of U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps personnel who provided advice and assistance to the Ministry of Defense, Joint General Staff, corps and division commanders, training centers, and province and district headquarters. 1960 – The Soviet Union charged Francis Gary Powers, whose U-2 spy plane was shot down over the country, with espionage. 1999 – An Air Force cargo jet took off from Seattle on a dangerous mission to Antarctica to drop medicine for Dr. Jerri Nielsen, a physician at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Research Center who had discovered a lump in her breast. The mission was successful; Nielsen was evacuated the following October. Congressional Medal of Honor Citations for Actions Taken This Day CARNEY, WILLIAM H. Rank and organization: Sergeant, Company C, 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry. Place and date: At Fort Wagner, S.C., 18 July 1863. Entered service at: New Bedford, Mass. Birth: Norfolk, Va. Date of issue: 23 May 1900. Citation: When the color sergeant was shot down, this soldier grasped the flag, led the way to the parapet, and planted the colors thereon. When the troops fell back he brought off the flag, under a fierce fire in which he was twice severely wounded.

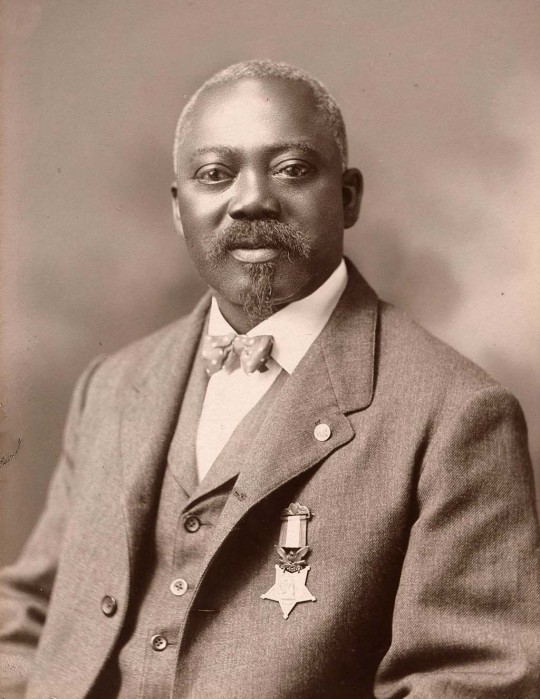

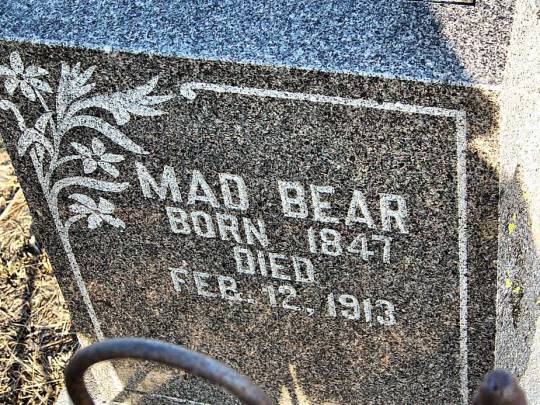

CO-RUX-TE-CHOD-ISH (Mad Bear) Rank and organization: Sergeant, Pawnee Scouts, U.S. Army. Place and date: At Republican River, Kans., 8 July 1869. Entered service at: ——. Birth: Nebraska. Date of issue: 24 August 1869. Citation: Ran out from the command in pursuit of a dismounted Indian; was shot down and badly wounded by a bullet from his own command.

SHEA, RICHARD T., JR. Rank and organization: First Lieutenant, U.S. Army, Company A 17th Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division. Place and date: Near Sokkogae, Korea, 6 to 8 July 1953. Entered service at: Portsmouth, Va. Born: 3 January 1927, Portsmouth, Va. G.O. No.: 38, 8 June 1955. Citation: 1st Lt. Shea, executive officer, Company A, distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry and indomitable courage above and beyond the call of duty in action against the enemy. On the night of 6 July, he was supervising the reinforcement of defensive positions when the enemy attacked with great numerical superiority. Voluntarily proceeding to the area most threatened, he organized and led a counterattack and, in the bitter fighting which ensued, closed with and killed 2 hostile soldiers with his trench knife. Calmly moving among the men, checking positions, steadying and urging the troops to hold firm, he fought side by side with them throughout the night. Despite heavy losses, the hostile force pressed the assault with determination, and at dawn made an all-out attempt to overrun friendly elements. Charging forward to meet the challenge, 1st Lt. Shea and his gallant men drove back the hostile troops. Elements of Company G joined the defense on the afternoon of 7 July, having lost key personnel through casualties. Immediately integrating these troops into his unit, 1st Lt. Shea rallied a group of 20 men and again charged the enemy. Although wounded in this action, he refused evacuation and continued to lead the counterattack. When the assaulting element was pinned down by heavy machine gun fire, he personally rushed the emplacement and, firing his carbine and lobbing grenades with deadly accuracy, neutralized the weapon and killed 3 of the enemy. With forceful leadership and by his heroic example, 1st Lt. Shea coordinated and directed a holding action throughout the night and the following morning. On 8 July, the enemy attacked again. Despite additional wounds, he launched a determined counterattack and was last seen in close hand-to-hand combat with the enemy. 1st Lt. Shea’s inspirational leadership and unflinching courage set an illustrious example of valor to the men of his regiment, reflecting lasting glory upon himself and upholding the noble traditions of the military service.

SOURCE

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ghost Dance Drum, c. 1891-1892. George Beaver (unknown dates), Pawnee, Oklahoma Wood, rawhide, pigment. In the 1880s, a millennial spiritual movement arose among Plains Indians, expressed in a ceremony called the GHOST DANCE. Diameter: 23 in. (58.4 cm) Chicago (Illinois), The Field Museum of Natural History. (via: thirdeye.com)

From Wiki: “The Ghost Dance (Caddo: Nanissáanah, also called the Ghost Dance of 1890) was a new religious movement incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. According to the teachings of the Northern Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka (renamed Jack Wilson), proper practice of the dance would reunite the living with spirits of the dead, bring the spirits to fight on their behalf, make the white colonists leave, and bring peace, prosperity, and unity to Native American peoples throughout the region.

The basis for the Ghost Dance is the circle dance, a traditional dance done by many Native Americans. The Ghost Dance was first practiced by the Nevada Northern Paiute in 1889. The practice swept throughout much of the Western United States, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As the Ghost Dance spread from its original source, different tribes synthesized selective aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs.

The Ghost Dance was associated with Wovoka's prophecy of an end to white expansion while preaching goals of clean living, an honest life, and cross-cultural cooperation by Indians. Practice of the Ghost Dance movement was believed to have contributed to Lakota resistance to assimilation under the Dawes Act. In the Wounded Knee Massacre in December 1890, United States Army forces killed at least 153 Miniconjou and Hunkpapa from the Lakota people. The Lakota variation on the Ghost Dance tended towards millenarianism, an innovation that distinguished the Lakota interpretation from Jack Wilson's original teachings. The Caddo still practice the Ghost Dance today.”

Read more: Here

Related post: Here

#Ghost Dance#Ghost Dance Drum#Pawnee#Plains Indian#Native American#Art#Art History#Dance#Spiritual#Musical Instrument#Spirituality

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New wood fired press plate by @woodfire . . . #woodfiredceramics #woodfireme #ceramics #clay #pottery (at Pawnee, Illinois) https://www.instagram.com/p/B1q56SVAGOA/?igshid=1vrxano1z4tws

14 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

U.S. Daily High Temperature Records Tied/Broken 10/21/22

Tangass National Forest, Alaska: 59 (previous record 55 1957)

Dunsmuir, California: 87 (previous record 86 2003)

Unincorporated Shasta County, California: 90 (also 90 1988)

Lakewood, Colorado: 78 (also 78 2003)

Pawnee National Grasslands, Colorado: 78 (previous record 77 2017)

Roosevelt National Forest, Colorado: 74 (also 74 2003)

Unincorporated Maui County, Hawaii: 94 (previous record 93 2020)

Rock Island Township, Illinois: 80 (also 80 2017)

Cedar Rapids, Iowa: 83 (also 83 1979)

Center Township, Iowa: 84 (also 84 1978)

Iowa City, Iowa: 85 (previous record 81 2017)

Dodge Township, Kansas: 87 (also 87 2003)

Emporia Township, Kansas: 90 (previous record 89 1978)

Gardner, Kansas: 86 (previous record 83 1968)

Hutchinson, Kansas: 88 (also 88 2012)

Manhattan, Kansas: 90 (previous record 83 1999)

Russell Township, Kansas: 89 (also 89 2003)

Salina, Kansas: 89 (also 89 1978)

Topeka, Kansas: 90 (previous record 88 1978)

Glacier National Park, Montana: 61 (previous record 60 1974)

Terry, Montana: 80 (also 80 2014)

Unincorporated Treasure County, Montana: 80 (also 80 2014)

Unincorporated Banner County, Nebraska: 81 (previous record 80 2017)

Bottineau, North Dakota: 75 (previous record 74 1918)

Max, North Dakota: 75 (also 75 2017)

Unincorporated Stutsman County, North Dakota: 73 (also 73 2017)

Underwood, North Dakota: 75 (previous record 73 1992)

Willow City, North Dakota: 76 (also 76 1901)

Chickasaw National Recreation Area, Oklahoma: 90 (previous record 88 2003)

Ponca City, Oklahoma: 93 (previous record 91 2012)

Unincorporated Blanco County, Texas: 88 (also 88 2007)

Ft. Worth, Texas: 92 (previous record 89 2017)

Guadalupe Peak summit, Texas: 106 (previous record 72 2020)

Mineral Wells, Texas: 94 (previous record 92 1979)

Waco, Texas: 92 (also 92 2004)

White Settlement, Texas: 91 (previous record 89 2012)

Unincorporated Duchesne County, Utah: 73 (previous record 71 1988)

Unincorporated Chelan County, Washington: 72 (previous record 68 2018)

Yakima Nation Reservation, Washington: 80 (previous record 77 1942)

Buena Vista Township, Wisconsin: 81 (also 81 1953)

Unincorporated Park County, Wyoming: 81 (previous record 79 2003)

Unincorporated Sweetwater County, Wyoming: 70 (also 70 1940)

#U.S.A.#U.S.#1980s#Colorado#Illinois#Montana#1970s#Nebraska#North Dakota#1910s#1990s#1900s#Oklahoma#Texas#Utah#Washington#1940s#Wyoming#Alaska#Kansas#Wisconsin#1950s#Iowa#Hawaii#1960s#Crazy Things

0 notes

Text

Midwest Mission a special place

Sometimes traveling locally, I learn about remarkable groups. I visited on wonderful group on December 8th, when I got the chance to tour Midwest Mission and see what they do. This is a true Christmas story of volunteers making a difference both locally, and around the world! I had heard about it and knew that our church at Trinity Lutheran in Auburn had teamed up with them to make rice meals,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Biden-Harris Administration provides $759 Million to bring high-speed internet access to communities across rural America

- By U.S. Department of Agriculture. (USDA) -

WASHINGTON, D.C., Oct. 27, 2022 – U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Secretary Tom Vilsack today announced that the Department is providing $759 million to bring high-speed internet access (PDF, 204 KB) to people living and working across 24 states, Puerto Rico, Guam and Palau.

Today’s investments include funding from President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which provides a historic $65 billion to expand reliable, affordable, high-speed internet to all communities across the U.S.

“People living in rural towns across the nation need high-speed internet to run their businesses, go to school and connect with their loved ones,” Vilsack said. “USDA partners with small towns, local utilities and cooperatives, and private companies to increase access to high-speed internet so people in rural America have the opportunity to build brighter futures. Under the leadership of President Biden and Vice President Harris, USDA is committed to making sure that people, no matter where they live, have access to high-speed internet. That’s how you grow the economy – not just in rural communities, but across the nation.”

The $759 million in loans and grants comes from the third funding round of the ReConnect Program. As part of today’s announcement, for example:

North Carolina’s AccessOn Networks Inc. is receiving a $17.5 million grant to connect thousands of people, 100 businesses, 76 farms and 22 educational facilities to high-speed internet in Halifax and Warren counties in North Carolina. The company will make high-speed internet service affordable by participating in the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) Lifeline and Affordable Connectivity Programs. This project will serve socially vulnerable communities in Halifax and Warren counties and people in the Haliwa-Saponi Tribal Statistical Area.

Tekstar Communications is receiving a $12.6 million grant to deploy a fiber-to-the-premises network to connect thousands of people, 171 farms, 103 businesses and an educational facility to high-speed internet in Douglas, Otter Tail, St. Louis, Stearns and Todd counties in Minnesota. Tekstar will make high-speed internet affordable by providing its “Gig for Life” service, where households that sign up for internet will not have their internet prices raised as long as they stay at the same address and continue service. Tekstar also will participate in the FCC’s Lifeline and Affordable Connectivity Programs.

In Colorado, the Eastern Slope Rural Telephone Association is receiving an $18.7 million grant to deploy a fiber-to-the-premises network connecting thousands of people, 898 farms, 110 businesses and 17 educational facilities to high-speed internet in Adams, Arapahoe, Cheyenne, Crowley, Elbert, Kiowa, Kit Carson, Lincoln and Washington counties. The company will make high-speed internet affordable by participating in the FCC’s Affordable Connectivity Program.

USDA is making 49 awards in Alaska, Alabama, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, Wyoming, Puerto Rico, Guam and Palau. This list includes awards to the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma, and the utility authorities for the Navajo Nation and the Tohono O’odham Nation. Many of the awards will help rural people and businesses on Tribal lands.

In 2022, the Department has announced $1.6 billion from the third round of ReConnect funding.

Background: ReConnect Program

To be eligible for ReConnect Program funding, an applicant must serve an area that does not have access to service at speeds of 100 megabits per second (Mbps) (download) and 20 Mbps (upload). The applicant must also commit to building facilities capable of providing high-speed internet service with speeds of 100 Mbps (download and upload) to every location in its proposed service area.

To learn more about investment resources for rural areas, visit www.rd.usda.gov or contact the nearest USDA Rural Development state office.

Background: Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

President Biden forged consensus and compromise between Democrats, Republicans and Independents to demonstrate our democracy can deliver big wins for the American people. After decades of talk on rebuilding America’s crumbling infrastructure, President Biden delivered the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law – a historic investment in America that will change people’s lives for the better and get America moving again.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law provides $65 billion to ensure every American has access to affordable, reliable high-speed internet through a historic investment in broadband infrastructure deployment. The legislation also lowers costs for internet service and helps close the digital divide, so that more Americans can take full advantage of the opportunities provided by internet access.

USDA Rural Development provides loans and grants to help expand economic opportunities, create jobs and improve the quality of life for millions of Americans in rural areas. This assistance supports infrastructure improvements; business development; housing; community facilities such as schools, public safety and health care; and high-speed internet access in rural, tribal and high-poverty areas. For more information, visit www.rd.usda.gov.

USDA touches the lives of all Americans each day in so many positive ways. In the Biden-Harris Administration, USDA is transforming America’s food system with a greater focus on more resilient local and regional food production, fairer markets for all producers, ensuring access to safe, healthy and nutritious food in all communities, building new markets and streams of income for farmers and producers using climate-smart food and forestry practices, making historic investments in infrastructure and clean-energy capabilities in rural America, and committing to equity across the Department by removing systemic barriers and building a workforce more representative of America. To learn more, visit www.usda.gov.

To subscribe to USDA Rural Development updates, visit the GovDelivery subscriber page.

#

USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender.

--

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture. (USDA)

Read Also

Canadian government unveils affordable high-speed Internet program

0 notes

Photo

The Hastings College Tour Arrives in Pawnee City

By Mrs. Veleba

Photos by Mrs. Veleba and Ms. Kristi Robison

On Friday, November 9, the Hastings College band and choir stop off to perform in Pawnee City during their Fall 2018 Tour. Their tour started on November 8 at Nebraska City High School, followed by Papillion-Lavista High School and the Church of the Cross in Omaha. Following the concert in Pawnee City, they are scheduled to perform in Beatrice at 7:00. They end their tour on Sunday, November 11 at Southminster Presbyterian Church in Prairie Village, KS and then back in Hastings at the Presbyterian Church that evening.

The Head of the Music Department, Dr. Byron Jensen, said that they are touring with 52 band and choir students this week. Dr. Jensen commented, “We haven’t been on tour for quite a while, but we’re hoping that this tour will get us back on track with a tour every other year.”

The band was conducted today by Dr. Louie Eckhardt, and the choir was conducted by Dr. Fritz Mountford. The students played and sang a wide range of music, and featured Dr. Bobby Fuson on the soprano saxophone and Dr. Eckhardt on the natural trumpet, as well as two student soloists, one vocalist and one student playing the marimba.

As an alum of Hastings College, it’s always a proud moment when I get to watch the band and choir. Today’s performances brought back many memories from my time in the Bronco band. We went on tour twice over my years in the band and traveled to towns in western Nebraska, Wyoming, and Illinois, playing at schools and churches and meeting new people. What an opportunity!!

A special “THANK YOU” to the parents who helped to feed the Hastings College students and our high school band and choir members. The lasagna, salad, garlic bread, cookies, and water were very much appreciated!!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Bear attack Spanish dime novel, Aventuras Extraordinarias de Buffalo Bill, "Daniel el oso y el oso Juan" (Grizzly Dan and John the Bear), circa 1931, anonymous (Prentiss Ingraham), translated by Gregorio La Fuerza. So-called "thick book" reprint of Buffalo Bill Stories No. 528 (1911), "Buffalo Bill and Grizzly Dan; or, Pawnee Bill's Great Swing". Also reprinted in New Buffalo Bill Weekly No. 281 (1918, and image courtesy Northern Illinois University).

The Steam Man of the West

#dime novel#bear attack#animal attack#buffalo bill#western#pawnee billk#grizzly dan#spanish#sorpena#barcelona

2 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

U.S. Daily Precipitation Records Tied/Broken 8/30/22

Unincorporated Autauga County, Alabama: 1.46" (previous record 0.8" 2001)

Atigun Pass summit, Alaska: 0.5" (also 0.5" 2012)

Nome, Alaska: 1.33" (previous record 0.94" 1927)

Lead Hill, Arkansas: 2.07" (previous record 1.9" 1991)

Mammoth Spring, Arkansas: 2.1" (previous record 1.95" 1928)

White River Township, Arkansas: 1.83" (previous record 1.55" 2014)

Gilroy, California: 0.01" (previous record 0" 2021)

Carlinville, Illinois: 1.31" (previous record 1.18" 1994)

Danville, Illinois: 1.73" (previous record 1.32" 1918)

Dwight Township, Illinois: 0.65" (previous record 0.4" 2016)

Mattoon, Illinois: 2.08" (previous record 1.12" 1982)

Paris, Illinois: 1.55" (previous record 0.92" 1982)

Philo Township, Illinois: 1.19" (previous record 0.72" 2003)

Shelbyville, Illinois: 0.37" (previous record 0.25" 1978)

Sidell Township, Illinois: 1.96" (previous record 1.41" 1951)

Sullivan Township, Illinois: 1.68" (previous record 0.75" 2001)

Windsor, Illinois: 1.5" (previous record 1.33" 1918)

Francesville, Indiana: 1.33" (previous record 0.67" 1993)

Greenfield, Indiana: 2.5" (previous record 1.07" 1981)

Huntington, Indiana: 0.68" (previous record 0.6" 2003)

New Castle, Indiana: 2.41" (previous record 1.57" 1960)

Rockville, Indiana: 4.1" (previous record 1.57" 1964)

Shelbyville, Indiana: 2" (previous record 1.5" 1918)

Tell City, Indiana: 1.83" (previous record 1.69" 1974)

Washington Township, Indiana: 2" (previous record 1.89" 1985)

Hazard, Kentucky: 2.16" (previous record 0.88" 2006)

Louisville, Kentucky: 1.47" (previous record 1.4" 2005)

Paris, Kentucky: 0.75" (previous record 0.71" 1990)

Baldwyn, Mississippi: 1.43" (previous record 0.61" 1940)

Alton, Missouri: 2.37" (previous record 1.9" 1978)

Jasper Township, Missouri: 2.1" (previous record 1.9" 1978)

Rosebud, Missouri: 2.84" (previous record 0.91" 2004)

Millville, New Jersey: 0.96" (previous record 0.4" 2003)

Queensbury, New York: 1.58" (previous record 0.71" 1983)

Seal Township, Ohio: 2.2" (previous record 1.33" 1974)

Tiffin Township, Ohio: 1.26" (previous record 0.99" 1980)

Warren Township, Ohio: 0.98" (previous record 0.93" 2018)

Pawnee, Oklahoma: 2.2" (previous record 1.1" 2003)

Pittston Township, Pennsylvania: 1.42" (previous record 0.98" 1955)

Somerset, Pennsylvania: 0.66" (previous record 0.6" 1989)

Abernathy, Texas: 0.62" (previous record 0.6" 2016)

Breckenridge, Texas: 3.45" (previous record 1.73" 1993)

Coleman, Texas: 3" (previous record 1.3" 1964)

College Station, Texas: 1.72" (previous record 1.15" 1960)

Crosbyton, Texas: 1.7" (previous record 1" 1910)

Del Rio, Texas: 3.19" (previous record 2.33" 1996)

El Campo, Texas: 2.41" (previous record 1.68" 1953)

Unincorporated Floyd County, Texas: 2" (previous record 1.55" 1963)

Friendship Park, Texas: 3.15" (previous record 0.88" 1964)

Unincorporated Gillespie County, Texas: 2.9" (previous record 1.65" 1974)

Unincorporated Lavaca County, Texas: 2.95" (previous record 1.11" 2001)

Richmond, Texas: 3.44" (previous record 2.35" 1953)

Unincorporated Runnels County, Texas: 2.5" (previous record 1.19" 1996)

Slaton, Texas: 0.75" (previous record 0.68" 2008)

Spur, Texas: 1.6" (previous record 1.43" 1944)

Unincorporated Taylor County, Texas: 2.3" (previous record 1.51" 1974)

Turkey, Texas: 0.62" (previous record 0.6" 2020)

Bridgeport, West Virginia: 1.16" (previous record 0.47" 2003)

Unincorporated Randolph County, West Virginia: 0.99" (also 0.99" 1974)

Wheeling, West Virginia: 1.83" (previous record 1.16" 2005)

Powder River Pass summit, Wyoming: 0.4" (also 0.4" 1995)

#Storms#U.S.A.#U.S.#Alabama#Arkansas#1990s#1920s#Illinois#1910s#1980s#1970s#1950s#Indiana#1960s#Kentucky#Mississippi#1940s#Missouri#Ohio#Oklahoma#Pennsylvania#Texas#West Virginia#Wyoming#Alaska#New Jersey#New York#Crazy Things#Awesome

0 notes

Text

Big Brutus & More in Southeast Kansas!

I grew up in a mining community, Pawnee, Illinois. Peabody # 10 located between Pawnee and Kincaid when it was open, was one of the largest coal mines in the world. So, it makes sense that I am interested in mining history both locally and far away. On a hosted trip by Explore Crawford County, I found some amazing mining stories, equipment and sites! Page 618 Walking Dragline In Southeast…

View On WordPress

#Big Brutus#Big Brutus Museum#big shovels#boom#Bucyrus Erie Company of Milwaukee#Cherokee County#Chris Wilson#clay mining#coal mines#coal strike drilling well#Crawford County#Davey Tripp#dragline#educational exhibit#environmental devastation#equipment#Explore Crawford County#habitat restoration#Hodges and Armit#immigrant#immigrant history#Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks#Kansas History by Fred Howell#KS47#Labette county#Mind Land Wildlife Area#Mined Land#Miners and Monroe#Miners Hall Museum of Franklin Kansas#miners memorial

1 note

·

View note

Photo

list for people having trouble with the image:

Wiyot - wayits (dog)

Pomo - kawá:yu (horse)

Mojave - ahat (pet)

Salish - stiqíw (meaning still a mystery)

Sahaptin - k’úsi (dog)

Navajo - łį’į’ (dog, pet)

Northern Cheyenne - moehenoha (tame elk)

Arikara - xaawaarúxti (sacred dog)

Cree - mistatim (big dog)

Keres - kawaayu (horse)

Nahuatl - cahuallo (horse)

Karankawa - kuwayi (horse)

Comanche - puuku (pet, companion animal)

Pawnee - aruúsa (dog)

Lakota (Sioux) - šuŋkawakháŋ (mystery dog)

Meskwaki - netaya (dog, pet)

Illinois - neekatikašia (one-clawed)

Ojibwe - bebezhigooganzhii (single nail on each foot)

Shawnee - mishawa (elk)

Choctaw - issoba (like a deer)

Cherokee - sogwili (burden-bearer)

Creek - cerakko (big deer)

Cayuga - karǫtanékhwi (log-hauler) ((not 100% sure about this one but i did my best))

Mohawk - iakohsá:tens (it is ridden)

Mi’kmaq - tesipow (horse)

Map of Native American etymologies for “horse”. There were no horses in the Americas before the colonists arrived. Native Americans quickly developed new words for this strange animal, often associating them with dogs, their one other domestic animal before contact with Europe.

99K notes

·

View notes

Text

"THE CHISHOLMS" (1979): Chapter II Commentary

"THE CHISHOLMS" (1979): CHAPTER II Commentary The first episode of the 1979 miniseries, "THE CHISHOLMS" - otherwise known as Chapter I had focused on the Chisholm family's last year at their western Virginia farm. The episode also explored the circumstances that led to patriarch Hadley Chisholm's decision to move the family west to California during the spring of 1844 and their journey as far as Evansville, Indiana. This second episode focused on the next stage of their journey.

This new episode or Chapter II focused on a short period of the Chisholms' migration to California. It covered their journey from southeastern Illinois to Independence, Missouri. Due to the addition of a guide named Lester Hackett, who had agreed to accompany them as far as Missouri, the Chisholm family experienced its first crisis - one that led to a temporary split within the family ranks. The family's journey seemed to be smooth sailing at first. They managed to become used to the routine of wagon train traveling. Lester proved to be an agreeable companion who helped with both hunting for game and cooking. He even managed to save Bonnie Sue Chisholm, who briefly found herself trapped in the family's wagon being pulled away by their pair of skittish mules. Eventually, Bonnie Sue and Lester began expressing romantic interest in each other. But alas, the family's luck began to fade. A lone rider began trailing the Chisholm party. Lester discovered that he was a friend of someone named James Peabody, who believes Lester was responsible for the theft of some valuables that include a pair of Spanish pistols . . . the same pistols that Lester had claimed he lost in a poker match in Louisville. He and Bonnie Sue enjoyed a night of intimacy together before he abandoned the Chisholms . . . while riding Will Chisholm's horse. Around the same time, Hadley's violent encounter with a drunken Native American at a local tavern fully revealed his deep-seated bigotry towards all Native Americans and foreshadowed the problems it will cause. Then Hadley made one of the worst decisions of his life by allowing Will and middle son Gideon to pursue Lester to Iowa and recover the former's stolen horse. Upon their arrival in Iowa, Will made an equally disastrous decision. Instead of requesting information and help from the local sheriff, he and Gideon appeared at the Hackett farm, asking for Lester's whereabouts. The two brothers ended up being arrested for the theft of chicken eggs and trespassing. Although the charges of theft were dropped, Will and Gideon were convicted of trespassing and ordered to serve on a prison work gang for a month. This left the rest of the family to continue on to Independence, Missouri - the jump-off point for all westbound wagon trains. During their journey through Missouri, the Chisholms joined with the Comyns, a family from Baltimore. Upon their arrival in Independence, the Chisholms and the Comyns discover that most of the wagons trains had already departed. However, they managed to form a wagon party with a plainsman named Timothy Oates and his Pawnee wife, Youngest Daughter. Unaware that Will and Gideon have been sentenced to a prison work gang, and aware that they are already behind schedule, the Chisholms have no choice but to head west into the wilderness. For an episode that began in a light-hearted manner, Chapter II ended on a rather ominous note. You know, I have seen this production so many times. Yet, it never really occurred until recently how the turmoil caused by Lester Hackett in this episode ended up causing so much turmoil for the family. What makes this ironic is that it all began with the sexual attraction that had sprung up between him and Bonnie Sue Chisholm back in Louisville. The first sign of this turmoil manifested in Lester's abandonment of the family and especially, his theft of Will Chisholm's horse. The horse theft led to the separation of the family at a time when it would have been more imperative for them to be together as a unit. Hadley did not help matters by allowing Will and Gideon to search for Lester in Iowa. And the two brothers made the situation worse by failing to immediately contact the local sheriff before appearing at the Hackett farm - an act that led them to be sentenced one month on a prison work gang. Will and Gideon's situation made it impossible for them to catch up with the rest of the family on the trail. And as Beau Chisholm had pointed out to Hadley in Independence, they were not in a position to wait for the other two. The Chisholms had no choice but to leave with two other westbound parties - the Comyns from Baltimore and the frontiersman Timothy Oates and his wife, Youngest Daughter. Two families and a couple does not seem large enough for a safe journey on the overland trail. But considering they were all behind schedule, they could either take the risk continue west or hang around Independence until the next year. But I did notice that despite all of this turmoil, the light-hearted atmosphere of the episode's beginning seemed to have persisted. More importantly, Chapter II seemed to be marked by a good deal of humor. The episode included humorous moments like Hadley's negative comments about the Illinois and Missouri landscapes, Will and Lester's lively debate over using mules or oxen to pull wagon overland, Lester's attempts to win over the family - especially Minerva, and especially his sexy courtship of Bonnie Sue. Once Lester had abandoned the family near St. Louis, the humor continued. Will and Gideon's experiences in Iowa were marked with a good deal of sardonic humor. That same humor marked Hadley and Minerva's low opinion of the Comyn family. Even Hadley's quarrel with the Independence saloon owner permeated with humor and theatricality. Looking back on Chapter II, I can only think of two moments that really emphasized the gravitas of the Chisholms' situation - Hadley's violent encounter with the Native American inside an Illinois tavern and that final moment when the family continued west into the wilderness without Will and Gideon. When the Chisholms left Virginia in Chapter I, their journey was marked with a good number of interesting settings. That episode featured a detailed re-creation of Louisville and travel along the Ohio River. There seemed to be no such unusual settings for Chapter II. The entire episode focused on the family's journey through Illinois, Iowa and Missouri. Not once did the episode featured the family in St. Louis. And a few set pieces (or buildings) served as Independence, Missouri circa 1844. The performances from Chapter I held up very well. Robert Preston and Rosemary Harris, as usual, gave excellent performances as the family's heads - Hadley and Minerva Chisholm. I was especially impressed by Preston's performance in the scene involving Hadley's encounter with the intoxicated Native American. In it, the actor did a superb job in conveying both Hadley's racism toward all Native Americans and his poignant regret over the tragic circumstances (Allen Chisholm had been killed by a Native American in a drunken fight over a slave woman from the Bailey plantation) behind his toxic attitude. Both Ben Murphy and Brian Kerwin clicked rather well during those scenes that involved Will and Gideon Chisholm's search for Lester. The episode also featured solid performances from James Van Patten, Susan Swift, Katie Hanley (as the amusingly mild-mannered Mrs. Comyn) and David Heyward (as Timothy Oates). Veteran character actor Jerry Hardin gave an excellent performance the slightly proud, yet finicky Mr. Comyn, who seemed to run his life by his pocketwatch. But if I must be honest, this episode belonged to Stacy Nelkin and Charles Frank, who did superb jobs in conveying Bonnie Sue Chisholm and Lester Hackett's burgeoning romance. I was impressed by how both of them developed Bonnie Sue and Lester's relationship from sexual attraction to playful flirtations and finally, to a genuine romance that was sadly cut short by Lester's need for self-preservation from a charge of theft. Overall, I enjoyed Chapter II. In a way, it seemed to be the calm before the storm that threatens to overwhelm the Chisholm family on their trek to California. The episode seemed to be filled with a good deal of humor and romance. On the other hand, Lester Hackett's past and current choices in this episode seemed to hint an ominous future for the family by the end of the episode.

#The Chisholms#the chisholms 1979#evan hunter#oregon trail#california trail#Robert Preston#Rosemary Harris#ben murphy#brian kerwin#stacy nelkin#James Van Patten#susan swift#charles frank#jerry hardin#antebellum#david heyward

0 notes

Text

Extension of Replacement Period for Livestock Sold on Account of Drought on Cook & Co. News

New Post has been published on https://cookco.us/news/extension-of-replacement-period-for-livestock-sold-on-account-of-drought/

Extension of Replacement Period for Livestock Sold on Account of Drought

Notice 2019- 54

SECTION 1. PURPOSE This notice provides guidance regarding an extension of the replacement period under § 1033(e) of the Internal Revenue Code for livestock sold on account of drought in specified counties.

SECTION 2. BACKGROUND .01 Nonrecognition of Gain on Involuntary Conversion of Livestock. Section 1033(a) generally provides for nonrecognition of gain when property is involuntarily converted and replaced with property that is similar or related in service or use. Section 1033(e)(1) provides that a sale or exchange of livestock (other than poultry) held by a taxpayer for draft, breeding, or dairy purposes in excess of the number that would be sold following the taxpayer’s usual business practices is treated as an involuntary conversion if the livestock is sold or exchanged solely on account of drought, flood, or other weather-related conditions.

.02 Replacement Period. Section 1033(a)(2)(A) generally provides that gain from an involuntary conversion is recognized only to the extent the amount realized on the conversion exceeds the cost of replacement property purchased during the replacement period. If a sale or exchange of livestock is treated as an involuntary conversion under § 1033(e)(1) and is solely on account of drought, flood, or other weather-related conditions that result in the area being designated as eligible for assistance by the federal government, § 1033(e)(2)(A) provides that the replacement period ends four years after the close of the first taxable year in which any part of the gain from the conversion is realized. Section 1033(e)(2)(B) provides that the Secretary may extend this replacement period on a regional basis for such additional time as the Secretary determines appropriate if the weather-related conditions that resulted in the area being designated as eligible for assistance by the federal government continue for more than three years. Section 1033(e)(2) is effective for any taxable year with respect to which the due date (without regard to extensions) for a taxpayer’s return is after December 31, 2002.

SECTION 3. EXTENSION OF REPLACEMENT PERIOD UNDER § 1033(e)(2)(B) Notice 2006-82, 2006-2 C.B. 529, provides for extensions of the replacement period under § 1033(e)(2)(B). If a sale or exchange of livestock is treated as an involuntary conversion on account of drought and the taxpayer’s replacement period is determined under § 1033(e)(2)(A), the replacement period will be extended under § 1033(e)(2)(B) and Notice 2006-82 until the end of the taxpayer’s first taxable year ending after the first drought-free year for the applicable region.

For this purpose, the first drought-free year for the applicable region is the first 12-month period that:

(1) ends August 31;

(2) ends in or after the last year of the taxpayer’s four-year replacement period determined under § 1033(e)(2)(A); and (3) does not include any weekly period for which exceptional, extreme, or severe drought is reported for any location in the applicable region. The applicable region is the county that experienced the drought conditions on account of which the livestock was sold or exchanged and all counties that are contiguous to that county.

A taxpayer may determine whether exceptional, extreme, or severe drought is reported for any location in the applicable region by reference to U.S. Drought Monitor maps that are produced on a weekly basis by the National Drought Mitigation Center.

U.S. Drought Monitor maps are archived at http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/Maps/MapArchive.aspx.

In addition, Notice 2006-82 provides that the Internal Revenue Service will publish in September of each year a list of counties1 for which exceptional, extreme, or severe drought was reported during the preceding 12 months. Taxpayers may use this list instead of U.S. Drought Monitor maps to determine whether exceptional, extreme, or severe drought has been reported for any location in the applicable region.

The Appendix to this notice contains the list of counties for which exceptional, extreme, or severe drought was reported during the 12-month period ending August 31,

Under Notice 2006-82, the 12-month period ended on August 31, 2019, is not a drought-free year for an applicable region that includes any county on this list. Accordingly, for a taxpayer who qualified for a four-year replacement period for livestock sold or exchanged on account of drought and whose replacement period is scheduled to expire at the end of 2019 (or, in the case of a fiscal year taxpayer, at the end of the taxable year that includes August 31, 2019), the replacement period will be extended under § 1033(e)(2) and Notice 2006-82 if the applicable region includes any county on this list. This extension will continue until the end of the taxpayer’s first taxable year ending after a drought-free year for the applicable region.

SECTION 4. DRAFTING INFORMATION The principal author of this notice is Lewis Saideman of the Office of Associate Chief Counsel (Income Tax & Accounting). For further information regarding this notice, please contact Mr. Saideman at (202) 317-7006 (not a toll-free call).

APPENDIX

Alabama

Counties of Barbour, Bibb, Chilton, Coffee, Covington, Dale, Geneva, Henry, Houston, Jefferson, Shelby, and Tuscaloosa.

Alaska

Municipality of Anchorage. Boroughs of Kenai Peninsula, Ketchikan Gateway, Kodiak Island, Lake and Peninsula, Matanuska-Susitna. Census Areas of Prince of Wales-Outer Ketchikan, Skagway-Hoonah-Angoon, Valdez-Cordova, Wrangell-Petersburg, and Yukon-Koyukuk.

Arizona

Counties of Apache, Cochise, Coconino, Gila, Graham, Greenlee, La Paz, Maricopa, Mohave, Navajo, Pima, Pinal, Santa Cruz, Yavapai, and Yuma.

Arkansas

Counties of Columbia, Lafayette, and Union.

California

Counties of Del Norte, Humboldt, Imperial, Los Angeles, Modoc, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Siskiyou, Trinity, and Ventura.

Colorado

Counties of Alamosa, Archuleta, Baca, Bent, Boulder, Chaffee, Clear Creek, Conejos, Costilla, Crowley, Custer, Delta, Dolores, Eagle, Elbert, El Paso, Fremont, Garfield, Gilpin, Grand, Gunnison, Hinsdale, Huerfano, Jackson, Kiowa, Lake, La Plata, Larimer, Las Animas, Lincoln, Mesa, Mineral, Moffat, Montezuma, Montrose, Otero, Ouray, Park, Pitkin, Prowers, Pueblo, Rio Blanco, Rio Grande, Routt, Saguache, San Juan, San Miguel, and Summit.

Florida

Counties of Brevard, Holmes, Indian River, Jackson, Martin, Okaloosa, Palm Beach, Saint Lucie, and Walton.

Georgia

Counties of Atkinson, Bacon, Ben Hill, Berrien, Brantley, Bryan, Bulloch, Charlton, Chatham, Clay, Clinch, Coffee, Cook, Early, Effingham, Irwin, Jeff Davis, Lanier, Pierce, Screven, and Ware.

Hawaii

Counties of Hawaii, Honolulu, Kauai, and Maui.

Idaho

Counties of Bannock, Benewah, Bonner, Boundary, Canyon, Cassia, Franklin, Kootenai, Oneida, Owyhee, Payette, Power, Shoshone, Twin Falls, and Washington.

Illinois

Counties of Hancock, Henderson, Mercer, Rock Island, and Warren.

Iowa

Counties of Appanoose, Clarke, Davis, Decatur, Des Moines, Henry, Jefferson, Lee, Louisa, Lucas, Mahaska, Marion, Monroe, Ringgold, Van Buren, Wapello, and Wayne.

Kansas

Counties of Anderson, Atchison, Brown, Chase, Coffey, Dickinson, Douglas, Franklin, Geary, Greenwood, Harvey, Jackson, Jefferson, Johnson, Leavenworth, Linn, Lyon, McPherson, Marion, Marshall, Miami, Morris, Nemaha, Osage, Pottawatomie, Riley, Saline, Shawnee, Wabaunsee, and Wyandotte.

Louisiana

Parishes of Bienville, Bossier, Caddo, Claiborne, De Soto, Jackson, Lincoln, Natchitoches, Red River, Union, Webster, and Winn.

Maine

Counties of Cumberland, Hancock, Knox, Lincoln, Sagadahoc, and Waldo.

Michigan

Counties of Antrim, Charlevoix, Cheboygan, Crawford, Emmet, Kalkaska, Mackinac, Montmorency, Oscoda, Otsego, and Presque Isle.

Minnesota

County of Marshall.

Missouri

Counties of Adair, Andrew, Audrain, Barry, Barton, Benton, Boone, Buchanan, Caldwell, Callaway, Carroll, Cass, Cedar, Chariton, Christian, Clark, Clay, Clinton, Cole, Cooper, Dade, Dallas, Daviess, DeKalb, Douglas, Gentry, Greene, Grundy, Harrison, Hickory, Holt, Howard, Jackson, Jasper, Johnson, Knox, Laclede, Lafayette, Lawrence, Lewis, Linn, Livingston, McDonald, Macon, Maries, Mercer, Moniteau, Monroe, Morgan, Newton, Nodaway, Osage, Pettis, Phelps, Platte, Polk, Pulaski, Putnam, Randolph, Ray, Saint Clair, Saline, Schuyler, Scotland, Stone, Sullivan, Taney, Webster, Worth, and Wright.

Montana

Counties of Blaine, Flathead, Lincoln, Mineral, Phillips, Sanders, and Valley.

Nevada

Counties of Clark, Elko, Humboldt, Washoe, and White Pine.

New Mexico

Counties of Bernalillo, Catron, Chaves, Cibola, Colfax, Curry, DeBaca, Eddy, Grant, Guadalupe, Harding, Lea, Lincoln, Los Alamos, McKinley, Mora, Otero, Quay, Rio Arriba, Roosevelt, Sandoval, San Juan, San Miguel, Santa Fe, Sierra, Socorro, Taos, Torrance, Union, and Valencia.

New York

Counties of Clinton, Essex, Franklin, Hamilton, and Warren.

North Dakota

Counties of Benson, Bottineau, Burke, Cavalier, Divide, Eddy, Foster, Grand Forks, Hettinger, McHenry, Mountrail, Nelson, Pembina, Pierce, Ramsey, Renville, Rolette, Sheridan, Stark, Towner, Walsh, Ward, and Wells.

Oklahoma

Counties of Beckham, Blaine, Caddo, Canadian, Carter, Cimarron, Comanche, Cotton, Custer, Ellis, Garvin, Grady, Greer, Harmon, Jackson, Jefferson, Kay, Kiowa, Love, McClain, Noble, Nowata, Osage, Pawnee, Roger Mills, Rogers, Stephens, Tillman, Tulsa, Washington, and Washita.

Oregon

Counties of Baker, Benton, Clackamas, Clatsop, Columbia, Coos, Crook, Curry, Deschutes, Douglas, Gilliam, Grant, Harney, Hood River, Jackson, Jefferson, Josephine, Klamath, Lake, Lane, Lincoln, Linn, Malheur, Marion, Morrow, Multnomah, Polk, Sherman, Tillamook, Umatilla, Union, Wasco, Washington, Wheeler, and Yamhill.

South Carolina

Counties of Allendale, Barnwell, Beaufort, Berkeley, Charleston, Colleton, Dorchester, Hampton, and Jasper.

South Dakota

Counties of Brown, Edmunds, Faulk, Haakon, McPherson, Spink, and Ziebach.

Texas

Counties of Anderson, Aransas, Archer, Armstrong, Atascosa, Baylor, Bee, Bell, Bexar, Blanco, Borden, Bosque, Bowie, Brazos, Briscoe, Brooks, Brown, Burleson, Burnet, Caldwell, Callahan, Camp, Carson, Cass, Castro, Cherokee, Childress, Clay, Coke, Coleman, Collingsworth, Comal, Comanche, Concho, Coryell, Cottle, Crosby, Culberson, Dallas, Dawson, Deaf Smith, Delta, Denton, Dickens, Dimmit, Donley, Duval, Eastland, Edwards, Ellis, Erath, Falls, Fisher, Floyd, Foard, Franklin, Freestone, Frio, Gaines, Garza, Gillespie, Glasscock, Gonzales, Gray, Gregg, Guadalupe, Hale, Hall, Hamilton, Hardeman, Harrison, Haskell, Hays, Hill, Hockley, Hood, Hopkins, Houston, Howard, Hudspeth, Jack, Jeff Davis, Jim Hogg, Jim Wells, Johnson, Jones, Kendall, Kent, Kerr, Kimble, King, Kinney, Kleberg, Knox, Lamar, Lamb, Lampasas, La Salle, Leon, Limestone, Live Oak, Llano, Lubbock, Lynn, McCulloch, McLennan, McMullen, Madison, Marion, Martin, Mason, Maverick, Medina, Menard, Midland, Milam, Mills, Mitchell, Montague, Morris, Motley, Navarro, Nolan, Nueces, Oldham, Palo Pinto, Panola, Parker, Potter, Presidio, Randall, Reagan, Real, Red River, Refugio, Robertson, Runnels, Rusk, San Patricio, San Saba, Schleicher, Scurry, Shackelford, Smith, Somervell, Starr, Stephens, Sterling, Stonewall, Sutton, Swisher, Tarrant, Taylor, Terrell, Terry, Throckmorton, Titus, Travis, Upshur, Upton, Uvalde, Val Verde, Van Zandt, Webb, Wheeler, Wichita, Wilbarger, Williamson, Wilson, Wise, Wood, Young, Zapata, and Zavala.

Utah

Counties of Beaver, Box Elder, Cache, Carbon, Daggett, Davis, Duchesne, Emery, Garfield, Grand, Iron, Juab, Kane, Millard, Morgan, Piute, Rich, Salt Lake, San Juan, Sanpete, Sevier, Summit, Tooele, Uintah, Utah, Wasatch, Washington, Wayne, and Weber.

Vermont

Counties of Addison, Chittenden, Franklin, Lamoille, Orleans, and Washington. Washington

Counties of Clallam, Clark, Cowlitz, Grays Harbor, Jefferson, King, Kitsap, Klickitat, Lewis, Mason, Pacific, Pend Oreille, Pierce, Skagit, Skamania, Snohomish, Stevens, Thurston, Wahkiakum, and Whatcom.

Wyoming

Counties of Carbon and Sweetwater.

Guam Island of Guam.

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

Islands of Rota and Saipan.

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico

Municipalities of Aibonito, Barranquitas, Cabo Rojo, Cayey, Cidra, Coamo, Comerio, Guanica, Guayama, Guayanilla, Juana Diaz, Lajas, Penuelas, Ponce, Sabana Grande, Salinas, Santa Isabel, Villalba, and Yauco.

United States Virgin Islands

Islands of Saint Croix and Saint Thomas.

0 notes