#Napoleon biography

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Descriptions of Napoleon’s personality by Adam Zamoyski

“He was kind by nature, quick to assist and reward. He found comfortable jobs and granted generous pensions to former colleagues, teachers, and servants, even to a guard who had shown sympathy during his incarceration after the fall of Robespierre. He was generous to the son of Marbeuf, promoted his former commander at TouIon Dugommier and looked after his family when he died, did the same for La Poype and du Teil, and even found the useless Carteaux a post with a generous pension. Whenever he encountered hardship or poverty, he disbursed lavishly. He could be sensitive, and there are countless verifiable acts of solicitude and kindness that testify to his genuinely wishing to make people happy.”

“He was most at his ease with children, soldiers, servants, and those close to him, in whom he took a personal interest, asking them about their health, their families, and their troubles. He would treat them with a joshing familiarity, teasing them, calling them scoundrels or nincompoops; whenever he saw his physician, Dr. Jean-Nicolas Corvisart, he would ask him how many people he had killed that day.”

“He possessed considerable charm and only needed to smile for people to melt. He could be a delightful companion when he adopted an attitude of bonhomie. He was a good raconteur, and people loved listening to him speak on some subject that interested him, or tell his ghost stories, for which he would sometimes blow out the candles. He could grow passionate when discussing literature or, more rarely, his feelings.”

#source:#Napoleon: A Life by Adam Zamoyski#napoleon#Adam zamoyski#zamoyski#napoleonic era#napoleonic#Napoleon biography#bio#napoleon bonaparte#Dugommier#du Teil#La Poype#corvisart#Marbeuf#french revolution#frev#la révolution française#révolution française#first french empire#french empire#France#french history#history#19th century

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art dump! Sorry for the hiatus, but I’ve been pretty busy lately 😭. This is all random stuff from November/December btw.

Also, here's Saint-Just! I might make more frev art, but I want to read more about it, so probably in the distant future lol.

Also, happy new years everyone!! 🎉🎉

#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#art#my art#joachim murat#jean lannes#jean baptiste bessières#jean baptiste bernadotte#napoleon bonaparte#louis antoine de saint just#frev#josephine de beauharnais#more lannes art but i've been reading his biography recently so it felt obligatory haha

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is this the same woman who said Napoleon magically became more attractive as he became more successful and rose the ranks in society? Bit classist to the say the least

Let’s just take a moment to appreciate that Andrew Roberts, out of all the adjectives he might have chosen to describe the memoirs of Laure Junot, ultimately decided to go with bitchy.

#based Andrew Roberts#😂😂#laure junot#Napoleon#Napoelon Bonaparte#napoleonic era#napoleonic#Napoleon bio#napoleon biography#19th century#memoirs#memoir#junot#lol

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

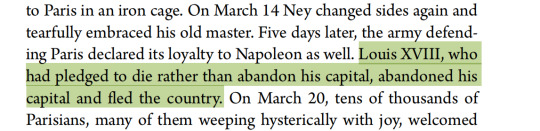

there are other ways this sentence could have been written but this is by far the funniest version

#thank you bell#napoleon: a concise biography by david a. bell#napoleonposting#napoleon bonaparte#louis xviii#certifiedhistoryaddict

460 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mortier and Lefebvre!

I think the letters between Lefebvre and Mortier are fun to read because they’re both always so sweet to each other☺️ Here, Lefebvre has been absent for some time from the army due to a wound at Ostrach. Mortier had written a letter to Lefebvre about how it was going in his Brigadier General gig, and Lefebvre responds:

"Your news has given me infinite pleasure, my dear Mortier, please continue it for me; you feel how much they must interest me, especially in the position I find myself in. My arm, which at first was doing very well, is today in the most alarming state due to the ineptitude of a health officer who, however, in Paris, enjoyed a certain reputation..... I unfortunately gave him leave a little late and accepted Director Barras' doctor..... “

“Keep me informed of your operations; stay at the forefront if possible; Besides, I will always try to have you with me when I return to the army which, unfortunately, I do not foresee soon.”

(pp. 77-78)

Also, the author does mention Mortier’s sadness whenever a general he had been under leaves the army. Here, he writes to a General Ernouf (and also mentions Lefebvre):

"I learned with great regret of your departure from the army. Must we therefore give up the hope of seeing you there again with General Jourdan, your brave friend? You can, at least, count on the fact that our attachment and our esteem will follow you everywhere and that, in particular, the regrets that I feel about our separation are as sincere as the friendship that I have forever dedicated to you and to the others..... “

“If you see General Lefebvre, please tell him how much we want to see him again; I'm worried to know how he's doing; I have written to him several times and I have not received any news.”

(p. 81)

That was written in May 6 a few months after Lefebvre had written the previous above letter on April 23.

Also, later, Mortier wanted to return to the Rhine to be under Lefebvre’s orders. He requests to move to the Army of the Rhine, but Lefebvre then writes a very lovely letter to him:

"You know, my dear Mortier, that ambition has never tormented me; I made my principles known to you and I would have thought I was failing them by accepting command of the Army of the Rhine.”

"I know how to appreciate the wish you form to serve with me; I love you and esteem you too much not to participate in everything that depends on me and I hope to succeed in bringing about our reunion as soon as the bad consequences of my injury allow me to return to service. In the meantime, give me your news more often; tell me, above all, something about your operations and the state of the army. “

So Lefebvre hadn’t yet taken command of the Army of the Rhine. Mortier responds with another affectionate letter☺️

"I received your good news on Thermidor 13; they would have been even more pleasant if you had been able to tell me of your complete recovery; However, the hope you gave me of your soon return to the army has revived the hope I have always had of returning under your orders; you are kind enough to promise me this and I make the most ardent wishes so that this much desired meeting can take place when the Army of the Rhine takes action. It is generally believed that you will return with Minister Bernadotte. The soldier is already feeling the effects of his work at the Ministry of War; It was time that his needs were finally taken care of.”

(p. 100)

And finally, here is a letter between the two later, when Lefebvre has better health and now commands the 17th military division in Paris. He sent Mortier this letter:

"I accept with great pleasure, my dear General, the offer that you gave me from Souvarow's car. So please, please, send it to me..... I think it won't be long before you cross the Rhine; this time we must succeed and take up our winter quarters in Swabia, Franconia and Bavaria; So keep me informed of your operations, they will become very interesting; but above all, always be convinced that nothing can diminish the sincere esteem and friendship that General Lefebvre will always have for you. “

“P.S. I always think, my dear Mortier, of bringing you closer to me. I had requested for you the command of the place of Paris, then that of Mainz; I was promised both, but your services have probably since been judged to be more useful to the army. However, I have not forgotten you and, certainly, you will still serve with me and as soon as possible.”

(p. 155-156)

And it does come true later! Mortier will eventually come to France and take command of the 17th military division from Lefebvre.

Frignet-Despréaux (colonel). Le Maréchal Mortier: Duc de Trévise. Par son petit-neveu Frignet Despréaux, Vol. III, Berger-Levrault, 1914. pp. 77-156.

Source

#napoleonic wars#napoleonic era#napoleon’s marshals#edouard mortier#francois joseph lefebvre#Mortier biography#Frignet Despréaux Vol.3

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

VANESSA KIRBY as EMPRESS JOSEPHINE Napoleon (2023) dir. Ridley Scott

#napoleon#biography#action#2020s#*#by courtney#filmgifs#moviegifs#filmtv#tvandfilm#tvfilmsource#filmtvdaily#dailytvfilmgifs#cinemapix#cinematv#ladiesofcinema#femaledaily#chewieblog#userbbelcher#userstream

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yep, another difference is that it was not hereditary.

From Napoleon: A Life, by Andrew Roberts. Pg. 465.

An unexpected revelation. In all honesty, not really that unexpected in itself, but I'm baffled by how easily wrong information can be spread. I've always wondered, indeed, how it was possible for him to be granted or have asked for the title of count given the feeling of "despise" between him and Napoléon.

The excerpt above comes from Gaffarel's biography (p. 349), Bouchard's one doesn't even mention such misunderstanding. According to the former, some of the earliest Prieur's biographers, whose work I happened to find here, stated that he was made comte de l'Empire without quoting a source and looking at the list of people receiving titles during the Napoleonic Era written by Campardon, Prieur's name is in fact missing.

#Napoleon#Andrew Roberts#Napoleon biography#Napoleon: a life#napoleonic era#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic reforms#Napoleon’s reforms#reforms

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mini reflections on the biography of Fouché by de Waresquiel: The description of the society of the Philadelphes

For those who have the biography written by Waresquiel about Fouché the subject begins on page 492(Fouché. Les silences de la pieuvre)

In Waresquiel's biography of Fouché (which is excellent, I’m not saying otherwise and it can only be recommended), there were moments when I respectfully disagreed (and at times, some parts of the biography were accurate but incomplete, such as his relationship with Babeuf, or sometimes even erroneous).

I won’t immediately address Waresquiel’s perspective (on the context of the dissolution of the neo-Jacobin club because that will be a separate post, as the neo-Jacobins were neither a danger nor extremist in my view, especially when we discover that the speech of Victor Bach, one of the neo-Jacobins, was deliberately distorted by their adversaries); but I would like to focus on how Waresquiel describes the society of the Philadelphes. "He (Malet) gathered around him a group of troublemakers, scribblers, former terrorists, and disgraced generals, most of whom, like him, were from Franche-Comté, and convinced them of the existence of a vast secret society poetically named the Philadelphes." Furthermore, Waresquiel mentions a few important names (such as Garat, Grégoire, Destutt de Tracy), but not all of them, which is quite unfortunate.

It seems to me (but this is only my point of view) that Waresquiel minimizes the significance of this society by using terms like "troublemakers" and "disgraced." In this society, there were some very important revolutionaries, such as Buonarrotti. Félix Le Peletier came into contact with this society through its founder, Colonel Oudet. Antonelle played a complex role in it, although we don't know exactly what role, as police reports vary. At times, he is described as a dangerous individual who needed to be watched (which is understandable, since in 1800, he was distributing pamphlets, including against Bonaparte, with his friend Félix Le Peletier), and later, a few years down the line, as someone no longer under surveillance. However, during the first Malet conspiracy, Antonelle’s name appears twice. The first time is when Émile Babeuf, the son of Gracchus Babeuf (already in contact with Buonarrotti), asks for "Reverend Father Antonelle," which recalls the clandestine activities (in which Émile and his mother, Marie-Anne, were already very well trained during Gracchus' time).

Then, a few days later, according to Pierre Serna, a suspect explains that Antonelle, according to the first Malet conspiracy, was to be appointed as minister if the conspiracy succeeded. Was it because Antonelle was a known Republican capable of gathering Republican support, or was he truly part of the conspiracy, given his hatred and opposition to Bonaparte? Pierre Serna states it is impossible to know. Natalie Petiteau affirms that Antonelle did act on behalf of this society.

In any case, my view is : this society was far more significant than it seemed (even though it was dismantled), and many of the people who made up this society were equally significant (I wonder, with the mysteries surrounding Marie-Anne, if she too was involved in a clandestine opposition movement with Émile, or if it was just a coincidence that her son, at the same time, wanted to reconnect with the revolutionary contacts of his late father in 1807), as Waresquiel suggests. Afterward, I agree with the rest of what Waresquiel wrote in this section, even if it illustrates well the "wars between parallel police forces" that historian Jean Tulard described, and the fact that Dubois, the police prefect (whose unscrupulous actions, such as his role in the dagger conspiracy and the judicial case that led to the execution of the anti-Babouvist revolutionary Bernard Metge—where Dubois worked for Fouché—clearly show his lack of integrity), "bypassed" Fouché to communicate directly with Bonaparte.

Nevertheless, the passage where Waresquiel states that "many of those appointed by the conspirators are his friends" raises a question. But who? Guillet? As for the Babeuf , they have not been his allies for a long time, at least since 1795-1796, and are his enemies(Waresquiel made this clear even if he does not show the fate of the rest of the Babeuf family under Bonaparte and the persecutions they suffered, especially Gracchus' widow) . Moreover, Marie-Anne Babeuf had already encountered police trouble when Fouché was minister in 1801, and perhaps the police procedure she underwent in Year VII, when she was denounced and subjected to a legal procedure, was also under Bonaparte's regime, so there was no special treatment from Fouché. I’ve already discussed various updated theories to understand why he harbored such a personal vendetta against her. Antonelle is an interesting case, as Fouché strangely refused to have him arrested, even though he had been, at one point, one of the most prominent Jacobin opponents of Bonaparte. Yet these two men were clearly not friends and differed on many points (aside from their shared reputation as "priests-eaters," although this is much more complex in reality). We know that Antonelle witnessed in Year III (since Fouché made the mistake, for some reason, of wanting him to be a witness) the attempt to buy the newspaper Babeuf refused, which Gracchus temporarily ruined Fouché's reputation over by publishing an article in the Tribun du Peuple, revealing in detail what Fouché had proposed to him, probably backed by Antonelle's testimony.

Once again, Fouché is capable of saving some of his "colleagues" (when he doesn’t throw them under the bus, like Collot d'Herbois—although he did provide a pension for his widow), such as Barère or Vadier, but there is no reason for him to act out of friendship for Antonelle, as they were not friends at all. Did Antonelle know something compromising? Or did Fouché want to minimize the danger Antonelle posed, knowing that the latest reports stated Antonelle was no longer a threat? It’s possible there’s another reason, but I haven’t found one yet.

In any case, Fouché had fewer scruples when dealing with Ricord, Baudement, and the Babeuf family (even though he had known Émile and his younger brother Camille when they were children, to the point that Gracchus had briefly considered entrusting his children to him; although, but from letters, it’s very clear that Émile did not like him, telling his father Gracchus that "it’s not the generosity of your friends that keeps us alive" when speaking of people like Fouché). For the umpteenth time in her life, Marie-Anne Babeuf will be interrogated by a police commissioner, and her residence will be searched to find out where Émile Babeuf, aged 22, is. He is traveling in Italy and Spain and thus manages to escape arrest. This time, Marie-Anne Babeuf will be released very quickly, probably after this interrogation, which, according to Dautry, seemed morally quite harsh. Anyway, it’s a pity that Waresquiel did not explore further the consequences of this conspiracy (especially since he had already discussed Fouché’s relationship with Babeuf) and did not propose any hypotheses on what transpired between Antonelle and Fouché, which would have been quite welcome, because I admit that I’m still looking for an answer as to why Fouché didn’t have Antonelle arrested.

Sources: Waresquiel Jean Dautry Jean-Marc Schiappa Bernard Gainot Natalie Petiteau Pierre Serna

P.S.:

Don’t take this as a personal attack on Waresquiel’s biography of Fouché. It’s simply my point of view, and in any case, I highly recommend it to everyone, as it is excellent; it just has some flaws, which is normal: no work is perfect and without defects. As proof of my good faith, I will also do what I reproach a historian I greatly admire, namely Jean-Marc Schiappa, regarding his biography of Babeuf, before doing another post on Waresquiel’s biography.

To learn a little more about Antonelle, click here.

On the details of the last meeting between Fouché and Babeuf which will be formed by a political break (Antonelle, Babeuf's ally and friend, will witness this meeting) it is here https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/773845581243334656/the-last-break-between-fouch%C3%A9-and-babeuf?source=share My theory why Fouché was surprised by Babeuf's refusal is the fact that Babeuf played the naive and the dupes in 1795, he would have actually understood what Fouché was doing at that time but pretended in prison to still believe in him as Babeuf did with Guffroy https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/776947165190897666/the-cunning-side-of-gracchus-babeuf-to-deceive-his?source=share

#waresquiel#biography#napoleonic era#babeuf#buonarroti#Le Peletier#Antonelle#fouche#history#france#1800s

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon (2023) dir. Ridley Scott

#filmedit#perioddramaedit#periodedit#napoleonedit#napoleon#napoleon 2023#gif#liz#2020s#action#adventure#biography

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not to start discourse but I really love how when I was a teenager I read about Robespierre and I thought that was interesting so then I read about Danton and Camille Desmoulins and Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI and Louis XVII and Louis XVIII and then I wanted more so I taught myself French and about the Marquis de Sade and Napoleon and and and

And also all these books about the culture and the history and the art and the individual people who we don’t have enough data for a biography but who still mattered and felt so strongly and did so much

Idk. It’s just fun, to me, to reach a point where any time I see a historical figure in the 18-19th century I can be like “I know that guy!!”

#napoleon#Robespierre#Marquis de Sade#Marie Antoinette#for the record? I am the farthest thing from an expert#so not @ me#I’m just saying it really is fun to like. read biographies on Sade and then you read a bio on napoleon and you see why Sade was locked up#and also you read a bio of Robespierre and he warns about the likes of Napoleon and napoleon rolls in like he’s fulfilling a prophecy#it’s neat. okay! it’s neat! my whole point is it’s neat!!!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have not watched or read Outlander (not my thing), and will not watch or read Outlander (because my introduction to the author was the time she made Fandom Wank for some super out-of-pocket rants against fanfic, and so many people IRL insisted I totally should watch it anyway even after I explained why it wasn't my thing that now I SUPER won't do it out of SPITE), but you know who HAS watched all of Outlander?

MY FATHER

who really likes historical fiction, but is 100% offline and therefore clicks blindly on shows based on the setting alone

and has not only watched every episode of Outlander available on Netflix, but remembers character names and plot points, and is very frustrated that Netflix only goes up through Season 6 (but not frustrated enough to figure out where else to watch it)

#this is extra funny to me because meanwhile his siblings are scandalized by anything beyond the most austere PG-13#this is also not the funniest show he watched all of bc he recognized the setting#the funniest show he watched all of bc he recognized the setting was the CW's Reign bc he had just read a Mary Stuart biography#'it really wasn't very accurate' YES FATHER IT'S ON THE CW#alas! for he cannot do subtitles or keep track of names if they aren't English#(as in: he keeps trying to get into Ancient Rome and Napoleon out of a sense of obligation but he loses the narrative too quickly)#(he feels bad about Rome but he honestly does not give a shit about Napoleon and that's so valid)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon’s mother wouldn’t stop calling him by his Corsican name, Napolione

#Napolione#source: Bonaparte by Corelli Barnett#Corelli Barnett#Napoleon bio#Napoleon biography#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#19th century#book#book pic#quotes#history#frev#French Revolution#letizia#letizia Bonaparte#Napoleon’s mother#Napoleon’s family#letter#1800s#first consul#napoleon bonaparte#france#Napoleon#Corsica#corse

93 notes

·

View notes

Note

I haven’t read any biographies of Soult. If I were to read one, would you recommend that Nicole Gotteri's book on him be the one to read?

Absolutely. Especially as I am unaware of any other similar in-depth study on Soult's life.

If possible, get this one:

N. Gotteri, "Le Maréchal Soult", éditions B. Giovanangeli, Paris, 2000

I've only borrowed that one from a library and found it had some additions (in particular more images) compared to the older book I own ("Le Maréchal Soult, maréchal d'empire et homme d'état", éditions La Manufacture, Besançon, 1991)

Nicole Gotteri is or was (she may be retired by now) an archiviste, working in the Archives Nationales, in charge of the napoleonic era documents. And she really dug into those 😋. So, unlike in many popular history books, you will usually find she cites her sources very thoroughly, i.e., if you want to fact-check her or just read up some stuff yourself, it's very easy. She even unearthed some letters to and from Soult that had been missing.

Like many (most?) biographers, she is quite in love with her subject though. I've noticed that there are a couple of instances when she follows Soult's own memoirs without giving a secondary source. And in order to exonerate Soult, she often is very harsh on both Berthier and Ney (not even talking about Joseph 😁). Just to give you a fair warning.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

A look at three Fouché biographies

Over the past few months I've read three English-language biographies on Fouché: Joseph Fouché: Portrait of a Politician, by Stefan Zweig; Fouché: Unprincipled Patriot, by Hubert Cole; and Medusa's Head: The Rise and Survival of Joseph Fouché, Inventor of the Modern Police State, by Rand Mirante. These are a great example of how dramatically interpretations of a historical figure can vary from one historian to another (see also the difference between Alan Schom's interpretation of Napoleon vs. that of Andrew Roberts). And also a great example of why it’s a good idea to read multiple biographies on the same figure, to gain a more well-rounded perspective, instead of simply accepting/adopting that of the first biographer you read.

Zweig is a colorful writer and his biography is highly entertaining—he actually had me laughing out loud a few times—but his depictions of Fouché are so hilariously sinister and malignant throughout that at times it almost feels like a caricature. Zweig also utilizes the least amount of primary source material out of the three biographers--hardly any, actually--and so much of what he writes in regard to Fouché's motivations and thoughts come across as pure speculation or projection, but are always stated very matter-of-factly. Zweig presents a Fouché who chafes at the smallness of the roles he is given, driven by "unflinching selfishness." "When in power," Zweig writes, "he does not work for the State, does not work for the Directory or for Napoleon, but for himself." Aside from raw ambition, Zweig attributes most of Fouché’s actions to his sheer delight in engaging in intrigue for the sake of intrigue, an interpretation that seems to come straight out of Napoleon’s venting on St. Helena: “Intrigue was to Fouché a necessary of life. He intrigued at all times, in all places, in all ways, and with all persons. Nothing ever came to light, but he was found to have had a hand in it. He made it his sole business to look out for something that he might be meddling with. His mania was to wish to be concerned with everything.” Overall, Zweig’s book is worth reading, but out of the three English-language Fouché biographies, it’d be ranked third on my list.

Hubert Cole’s interpretation of Fouché is as different from Zweig’s as night is from day. The key word in Cole’s title is “Patriot,” and Cole’s central point is that Fouché, at each point in his career, was doing what he believed was in the best interests of France, even if that meant negotiating for peace with Britain behind Napoleon’s back, or pushing Napoleon towards a divorce and remarriage for the sake of shoring up the Bonaparte dynasty, or even (repeatedly) abandoning one master to serve another. This is the second one of Cole’s biographies I’ve read, and as most of you following me already know, I loved his dual biography on Joachim and Caroline Murat, the deceptively named The Betrayers, which is actually a very sympathetic look at the Murat couple. Cole is no fan of Napoleon and doesn’t really attempt to hide it, and maybe it’s because of this that he feels inclined to look deeper at the motivations and actions of those who ended up in opposition to Napoleon at various points (and who have therefore been demonized in history books accordingly). Cole draws heavily on primary sources, from letters and memoirs of Fouché’s contemporaries, to Fouché’s police bulletins (quoted at length throughout) to argue that “It is possible… that he was a sincere and moderately successful patriot. It is not uncommon in France for egoists to be hailed as patriots, and patriots condemned as traitors.” Far from the sinister, cold-blooded figure that haunts Zweig’s biography, or the “universally distrusted, feared, and hated” social pariah of Mirante’s, Cole's Fouché is charming, a welcome figure in the drawing rooms of Paris society, with a preference for making friends rather than enemies; nevertheless Cole does not deny that Fouché could also be ruthless, ambitious, and cunning. Cole also uses numerous accounts regarding Fouché by British, German, and Russian contemporaries, “in the belief that their prejudices, if national, are less personal.” Out of these three biographies, this one was my personal favorite, as I think it provides a more well-rounded picture of Fouché as a human being.

The primary focus of Mirante’s book is Fouché’s administration of the Ministry of Police, and the biography goes into great detail about the operations of the police in Napoleonic France, its vast network of informants, subversion of the press, surveillance of emigrés, and steady stream of information flowing in from all quarters. Fouché emphasized to his subordinates how one small detail or event could be “of great interest in the general order of things by its connections with related matters of which you are scarcely aware.” Like Cole, Mirante quotes frequently from Fouché’s police bulletins, as well as from memoirs of the era (though most of the excerpts are those hostile to Fouché). Unlike Cole, Mirante’s Fouché is driven not by any higher patriotism, but—especially after his humiliating flight from France in 1810—by a deep and abiding hatred of Napoleon, towards whose final destruction Fouché is willing to go to any length. Mirante provides more detail on Fouché’s exile and final years than either Zweig or Cole, one interesting aspect of which is the warm welcome Fouché received in Trieste from Elisa Bonaparte, who had been driven from power in Tuscany largely through Fouché’s machinations with Murat in 1814. Mirante ends the book with a critical look at Fouché’s dubious, ghostwritten “memoirs,” the credibility of which he is far more suspicious than Cole, who accepts the argument of French historian Louis Madelin that they are “largely authentic and accurate.” Mirante, on the other hand, is not convinced, and concludes that the memoirs are “highly assailable, at least quasi-spurious, and shrouded in controversy and deceit.” Mirante ends by drawing parallels between Fouché’s policing methods and those of the Gestapo and NKVD in the 20th century.

Overall I enjoyed all three of these for different reasons, and taken together they offer a more complete picture of Fouché. I haven’t gotten around to reading any French-language biographies on Fouché yet, but I do have a couple works on him by Emmanuel de Waresquiel that are definitely on my to-read list.

#Joseph Fouché#Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#Napoleonic#history#19th century#books#biographies#French Revolution

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

so, like, daddy issues?

#the '' for solved was NEEDED#solved absolutely nothing. what are you doing with a father figure that hates your ass#napoleon: a biography by frank mclynn#what do you mean “especially as a corsican” !!#napoleon bonaparte#pasquale paoli#napoleonposting#certifiedhistoryaddict

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

God I so much prefer researching Habsburg history over reading about literally any of the other figures I'm interested in bcs it gives me genuine stress parsing through the giant amount of biographies, that have such a huge range of biases and narratives, and trying to decide which to actually embark upon. It's not like Habsburg scholarship is a small field or anything, but it's so much more limited than it is for someone like, say, Napoleon. For Habsburg stuff, I'll pretty much read anything bcs I'm so desperate to learn anything, and I usually have to go out of my way to even find books and papers

#everything carries the author's inherent bias obviously#but most habsburg books cover like. 500 years of history. so.#i loved the one random book i found which is just chock full of anecdotes#who the fuck knows if most of it happened but im taking it as the truth 🙏#meanwhile for napoleon im literally sweating reading thru people's reviews#trying to choose which giant ass book to embark upon#meanwhile the other day i came across a random habsburg book and bought it instantly#zero thought put into whether i might not like how the author portrays them or not#ill take whatever i can get 🙏🙏🙏#also i feel very trusting of many of the individual scholars#bcs they had to go out of their way to research a pretty under-researched historical figure#so i trust that they genuinely put a lot of care into it bcs its such an underdeveloped field comparatively#for other figures biographies are practically a dime a dozen#its not like charles vi where ill read any paper i come across bcs it feels like a rare treat#i genuinely have to put way too much thought into it 😭😭 its scary to me#catie.rambling.txt

4 notes

·

View notes